1. Introduction

In the contemporary era of pervasive digital communication, emotions play an increasingly complex and significant role in shaping human interaction. The rapid growth of digital technologies and social media platforms has transformed not only the way individuals communicate but also how emotions are experienced, expressed, and managed. The conventional boundaries of face-to-face interaction have expanded to include various mediated channels such as emails, instant messaging, social networks, and video calls, all of which shape and influence emotional exchanges in distinct ways (Derks, Fischer, & Bos, 2008). This digital transformation has necessitated a deeper understanding of Emotional Intelligence (EI) within mediated communication frameworks.

Emotional Intelligence, broadly defined as the capacity to recognize, understand, regulate, and manage one’s own emotions and the emotions of others, has been extensively studied in traditional interpersonal contexts (Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Goleman, 1995). However, its application in the digital realm, where emotional cues are often limited or distorted, presents unique challenges and opportunities. The asynchronous nature of many digital communications—such as emails and social media posts—allows for delayed responses and reflection but can also lead to emotional misinterpretations, impulsive reactions, and conflicts (Kruger, Epley, Parker, & Ng, 2005). This dynamic has led researchers to investigate how EI influences digital emotional exchanges and to explore novel conceptual frameworks for understanding these phenomena.

This paper introduces two metaphorical constructs—Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast—to better capture the dual processes of internal emotional reception and external emotional expression in digital communication contexts. The term Inbox Emotions refers to the internal emotional states individuals experience when they receive digital messages or content. These emotions may range from excitement and joy to anxiety, frustration, or anger. Conversely, Outbox Blast describes the external manifestation of these emotions, typically in the form of digital messages, posts, or responses that may be impulsive, aggressive, or otherwise emotionally charged. These metaphors reflect the cyclical nature of digital emotional interactions, where emotions are continually received, processed, and expressed, often with significant social consequences.

The importance of this dual-process model lies in its emphasis on the regulation and management of emotions between reception and expression—a process that is central to EI. The capacity to effectively regulate emotions before expressing them digitally can prevent misunderstandings, reduce conflict, and promote constructive dialogue. Conversely, failures in this regulation can result in what this paper terms an Outbox Blast: a reactive, often unfiltered emotional outpouring that can escalate conflicts, cause relational harm, and contribute to the spread of negative emotional contagion in online environments.

The need to understand and manage these emotional dynamics is underscored by the prevalence and impact of digital communication in everyday life. According to the Pew Research Center (2021), over 90% of adults in many developed countries use the internet regularly, with the majority engaging daily in some form of online communication. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram are central to how people maintain social relationships, share information, and express themselves emotionally. However, these platforms also serve as sites of emotional volatility, including cyberbullying, trolling, emotional manipulation, and viral emotional outbreaks (Papacharissi, 2015; Kramer, Guillory, & Hancock, 2014).

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated reliance on digital communication, heightening emotional stakes. Lockdowns and social distancing measures necessitated virtual interactions for work, education, and socialization, often increasing feelings of isolation, stress, and emotional overload (Marroquín, Vine, & Morgan, 2020). This shift highlighted the critical role of emotional intelligence in navigating these new communication landscapes and the consequences when emotional management fails.

The metaphorical framing of Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast also contributes to broader discussions of digital emotional ecology, a term that describes how emotions circulate, amplify, and interact within networked public spheres (Papacharissi, 2015). This ecological perspective recognizes that digital emotions are not merely individual experiences but are shaped by platform affordances, social norms, cultural contexts, and technological architectures. For instance, the design of a platform—whether it supports anonymity, rapid-fire exchanges, or multimedia expression—affects how emotions are expressed and perceived (Suler, 2004).

This paper argues that emotional intelligence serves as a crucial moderator within this digital emotional ecology. Individuals with high EI tend to engage in reflective emotional processing, employ effective emotional regulation strategies, and communicate more constructively online (Derks et al., 2008). In contrast, low-EI individuals are more prone to impulsive, emotionally charged responses, leading to the disruptive Outbox Blast phenomenon. The capacity to manage this emotional flow has profound implications for interpersonal relationships, organizational communication, and broader social cohesion in digitally mediated environments.

To explore these dynamics, this study employs a mixed-method approach that includes content analysis of digital communication samples and interviews with participants categorized by levels of emotional intelligence. This approach allows for both quantitative assessment of emotional expressions in digital texts and qualitative insights into the subjective emotional experiences and regulatory strategies of individuals.

This introduction proceeds as follows: first, it provides an overview of Emotional Intelligence as conceptualized in psychological and communication literature. Next, it situates EI within the context of digital communication, discussing the challenges posed by the absence of nonverbal cues and the potential for emotional misinterpretation. The section then elaborates on the Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast framework, defining key concepts and establishing their relevance. Finally, the introduction outlines the research questions and objectives that guide the study.

1: I Background of the Study

In the digital era, communication has transcended traditional boundaries, becoming instantaneous, multimedia-rich, and disembodied. One of the most profound transformations lies in how emotions are experienced, interpreted, and expressed through digital communication platforms. Emotional intelligence (EI)—defined as the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and regulate emotions in oneself and others (Salovey & Mayer, 1990)—is increasingly critical in navigating these digital landscapes. However, in the realm of texts, emojis, voice notes, and reactions, the expression and regulation of emotion have taken new forms that challenge our psychological and interpersonal competencies.

The phrase ‘Inbox Emotions, Outbox Blast’ captures a behavioral paradox of modern digital communication. ‘Inbox Emotions’ symbolizes the internal affective responses triggered by received digital messages—whether they are formal work emails, instant personal chats, or emotionally ambiguous social media comments. These messages act as stimuli that provoke emotional interpretation and affective arousal. Conversely, ‘Outbox Blast’ refers to emotionally charged or impulsive responses sent from the user’s device, often without reflective emotional processing or self-regulation. These ‘blasts’ may be hostile replies, venting posts, or emotionally manipulative texts that stem from unmanaged Inbox Emotions.

This phenomenon is not merely anecdotal but represents a growing socio-psychological concern. Emotional miscommunication in digital spaces can lead to misinterpretations, conflicts, cyberbullying, psychological distress, and deterioration of relationships (Derks et al., 2008; Suler, 2004). Moreover, emotionally dysregulated digital behaviors have real-world consequences, including workplace disputes, reputational damage, academic penalties, and even mental health crises (Choudhury et al., 2013).

The role of emotional intelligence in mitigating such outcomes has been substantiated across domains such as education, leadership, and mental health (Goleman, 1995; Bar-On, 2006). Yet, its application within digital communication environments remains underexplored. Particularly in South Asian societies, where emotional expression is often shaped by cultural codes of honor, family obligations, and gendered expectations, understanding the nuances of digital emotion management becomes even more essential.

This research seeks to bridge this gap by conceptualizing and empirically investigating the relationship between emotional intelligence and digital emotional regulation. It introduces the Digital Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (DERQ) as a new measurement tool and employs both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore how people in South Asia experience and express emotions in digital contexts.

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of:

The psychological mechanisms behind ‘Inbox’ emotional reactions to digital messages.

The behavioral expressions of ‘Outbox’ emotional responses and their consequences.

The moderating role of emotional intelligence in managing digital affective stimuli and responses.

The research holds interdisciplinary significance, intersecting psychology, communication studies, media sociology, and cyberpsychology. It is particularly relevant in an era where text-based communication dominates personal, professional, and public spheres—and where the stakes of miscommunication are higher than ever.

1.1. Emotional Intelligence: Conceptual Foundations

Emotional Intelligence emerged as a psychological construct in the early 1990s through the work of Salovey and Mayer (1990), who defined it as ‘the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions’ (p. 189). Goleman’s (1995) popularization of EI expanded this to include five key domains: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. These competencies collectively enable individuals to navigate social complexities, manage stress, and maintain interpersonal harmony.

Subsequent research has validated the importance of EI across domains including leadership, mental health, education, and conflict resolution (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004). EI is often measured using self-report scales (e.g., EQ-i 2.0) and ability-based assessments (e.g., Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, MSCEIT). High EI individuals typically demonstrate superior abilities in recognizing emotional cues, employing coping mechanisms, and fostering positive relationships (Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2011).

1.2. Emotional Intelligence in Digital Communication

The translation of EI competencies to digital communication is complex due to the unique characteristics of mediated interactions. Unlike face-to-face communication, digital platforms often lack or distort vocal tone, facial expressions, and body language, which are critical for interpreting emotions (Derks et al., 2008). This absence increases the risk of misinterpretation, sometimes referred to as ‘emoticon deficiency’ (Walther & D’Addario, 2001).

Moreover, asynchronous communication allows individuals time to reflect before responding, which can both facilitate emotional regulation and lead to overthinking or rumination. However, the relative anonymity and physical distance can also reduce social accountability, fostering disinhibition and impulsive behavior known as the ‘online disinhibition effect’ (Suler, 2004). Such effects complicate the process of managing Inbox Emotions and modulating Outbox Blasts.

Empirical studies indicate that individuals with high EI adapt better to these challenges by interpreting digital emotional cues more accurately, using emoticons and tone indicators effectively, and managing emotional responses to avoid conflict (Derks et al., 2008; Scherer, 2003). Conversely, low-EI users are more likely to experience digital emotional overload, react defensively or aggressively, and contribute to toxic communication climates (Caplan, 2007).

1.3. The Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast Metaphor

The Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast metaphor seeks to encapsulate the cyclical process of emotional reception and expression in digital communication. Inspired by email and messaging metaphors, the Inbox represents the emotional stimuli individuals receive—be it positive messages of support or negative feedback and criticism. The Outbox represents the individual’s response or emotional outpouring into the digital environment.

This conceptualization emphasizes the importance of the regulatory space between receiving and sending emotional messages. Emotional intelligence governs this space: it is the ‘emotional buffer’ that can transform reactive impulses into thoughtful responses. When this regulation fails, individuals may ‘blast’ their emotions into the outbox, often exacerbating conflicts and perpetuating negative emotional cycles (Kramer et al., 2014).

The metaphor is particularly useful for understanding phenomena such as flaming (hostile online interactions), trolling, and viral emotional contagion, where emotionally charged messages can spread rapidly and unpredictably (Papacharissi, 2015).

1.4. Objectives of the Study

This study aims to explore the role of emotional intelligence in shaping digital communication, emotional reactivity, and interpersonal dynamics among youth gang members in Bangladesh. In recent years, digital platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Messenger have emerged not only as spaces for social interaction but also as arenas where emotional expressions are performed, negotiated, and weaponized. Among youth gang members, whose identity constructions are deeply entangled with honor, masculinity, loyalty, and performance, these digital spaces have become battlegrounds for emotional projection and retaliation. Within this backdrop, the current study is premised on the need to understand how emotional intelligence—or the lack thereof—mediates digital expressions such as “inbox emotions” (private affective messages) and “outbox blasts” (public retaliatory posts, comments, or status updates).

Informed by both psychological theory and digital ethnography, the study is grounded in Goleman’s (1995) framework of emotional intelligence, Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) emotional ability model, and Suler’s (2004) notion of the online disinhibition effect. By integrating both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, the research investigates the affective ecologies of youth gangs in Bangladesh and their reliance on digital tools for emotional expression and social positioning.

The general objective of this study is:

To examine the interplay between emotional intelligence and digital emotional behavior among youth gang members in Bangladesh, particularly focusing on the distinction between private (inbox) and public (outbox) emotional expressions.

To achieve this overarching goal, the following specific objectives were formulated:

To evaluate the emotional intelligence levels among youth gang members using established psychometric tools and determine the correlation between EI and digital emotional behavior.

To explore how emotional reactivity, impulsivity, and symbolic retaliation are expressed through digital communication platforms among youth gang members.

To investigate how private affective communication (inbox messages, voice notes, and late-night chats) differs from public emotional performances (status updates, reaction chains, and confrontational posts) in digital settings.

To identify recurring emotional patterns, digital rituals, and affective triggers that contribute to intra-gang loyalty conflicts or inter-gang hostilities in online interactions.

To analyze how gender, socioeconomic background, digital literacy, and urban geography mediate emotional behavior and communication strategies in digital spaces among youth gang participants.

To document the psychological and emotional toll that digital communication patterns (such as continuous surveillance, provocation, or emotional performativity) may have on the mental health and relational stability of youth gang members.

To provide recommendations for psychosocial intervention programs, digital literacy training, and emotional regulation frameworks tailored to youth at risk of gang involvement and digital violence escalation.

The choice of these objectives is rooted in the multi-layered complexity of emotional intelligence as it intersects with digital performance, youth subcultures, and urban marginality in South Asia. Prior research has explored emotional intelligence in formal educational or corporate environments (Goleman, 1995; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2008), but limited empirical attention has been given to how EI operates within youth gangs and digital subcultures, especially in Bangladesh. In this context, youth gangs use social media not merely for entertainment or identity formation, but as critical sites for emotional expression, social validation, and confrontation. These objectives enable the research to address both the cognitive-affective dimensions of EI and the socio-digital mechanisms through which emotions are externally projected and contested.

The objectives are to develop a nuanced understanding of EI in digital contexts, provide empirical evidence of emotional regulation patterns, and suggest practical interventions to improve digital emotional literacy.

1.5. Research Questions

This research was guided by the following central research questions:

RQ1: What are the levels of emotional intelligence among youth gang members in Bangladesh?

RQ2: How do emotional intelligence levels influence the emotional interpretation of incoming digital communication (Inbox Emotions)?

RQ3: What patterns emerge in the expressive, often impulsive, behavioral responses (Outbox Blast) to perceived emotional triggers?

RQ4: How do gender, platform usage, and gang hierarchy moderate these relationships?

2. Literature Review

This section synthesizes key theoretical and empirical contributions related to Emotional Intelligence (EI) and its application in digital communication contexts. It is organized into four subsections: (1) foundational theories of Emotional Intelligence, (2) EI and emotional regulation, (3) EI in computer-mediated communication, and (4) emotional expression and regulation in digital environments. These domains establish the groundwork for the Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast framework developed in this paper.

2.1. Foundational Theories of Emotional Intelligence

The construct of Emotional Intelligence originated as an expansion of traditional intelligence theories to include affective competencies. Salovey and Mayer (1990) first conceptualized EI as the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and utilize emotions adaptively. They described four primary branches: perceiving emotions, facilitating thought with emotions, understanding emotions, and managing emotions (Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

Goleman (1995) broadened the concept to popular discourse by highlighting five domains of EI: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. This model emphasized EI’s role in personal and professional success, influencing leadership studies and organizational psychology (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2013). Subsequent research confirmed that EI is a significant predictor of social competence, mental health, and decision-making quality (Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008).

EI can be measured via ability tests such as the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) or through self-report instruments like the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) (Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2011). These measures assess individual differences in recognizing emotional cues, regulating affect, and empathizing with others.

2.2. Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation is a core component of EI and refers to the processes by which individuals influence the experience and expression of emotions (Gross, 1998). Gross’s Process Model (1998) outlines key regulation strategies including situation selection, modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change (reappraisal), and response modulation (suppression).

High EI individuals tend to employ adaptive regulation strategies such as cognitive reappraisal, which involves reframing a situation to change its emotional impact (John & Gross, 2004). Conversely, maladaptive strategies like emotional suppression often correlate with poorer mental health and interpersonal difficulties (Gross & John, 2003).

In social interactions, effective emotional regulation supports empathy, conflict resolution, and prosocial behaviors (Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2011). Failures in regulation can precipitate impulsive emotional outbursts, miscommunications, and relational strain, phenomena particularly relevant to digital communication.

2.3. Emotional Intelligence in Computer-Mediated Communication

The rise of computer-mediated communication (CMC) has shifted scholarly attention to how EI operates in technologically mediated environments. CMC encompasses various platforms including email, instant messaging, social media, and virtual meetings, each with distinct affordances impacting emotional expression and perception (Walther, 2011).

One key challenge in CMC is the absence of rich nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, gestures, and vocal tone, which are integral to emotional understanding in face-to-face interaction (Derks et al., 2008). This limitation leads to what Walther and D’Addario (2001) called ‘emoticon deficiency,’ where the lack of emotional indicators can cause message ambiguity or misinterpretation.

The use of emoticons, emojis, and other paralinguistic cues in digital text attempts to compensate for this loss, aiding emotional clarity and reducing misunderstandings (Lo, 2008). However, these symbols have cultural and contextual variability, requiring users to possess interpretive skills often linked to EI (Kaye, Wall, & Malone, 2017).

Moreover, the asynchronous nature of many CMC forms offers individuals more time to reflect before responding, which can enhance emotional regulation (Derks et al., 2008). Yet, this delay may also contribute to rumination or emotional escalation if negative emotions are repeatedly replayed mentally (Suler, 2004).

Another pertinent phenomenon is the ‘online disinhibition effect,’ whereby individuals express themselves more openly, sometimes aggressively, due to perceived anonymity and lack of immediate social consequences (Suler, 2004). This effect complicates emotional regulation, especially for users with low EI, leading to increased hostile or impulsive digital communication.

Empirical research has found positive correlations between EI and effective CMC use. Derks et al. (2008) demonstrated that individuals with higher EI are better at interpreting emotional cues in text, use emoticons more effectively, and regulate their emotional responses in digital interactions. Similarly, Caplan (2007) found that social anxiety and loneliness interact with low EI to predict problematic internet use characterized by emotional dysregulation.

2.4. Emotional Expression and Regulation in Digital Environments

The regulation of emotions in digital environments involves both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. On the intrapersonal level, individuals must manage their internal Inbox Emotions—the affective responses triggered by received digital content (messages, comments, posts). This internal emotional experience may be influenced by the content’s valence, relevance, and the recipient’s personal context (Papacharissi, 2015).

Interpersonally, the decision to share emotions through digital platforms reflects an individual’s capacity to modulate their Outbox Blast—the outward emotional expression. Outbox Blasts can take many forms including angry comments, sarcastic posts, or supportive messages, each with different social consequences.

Digital emotional expression is often amplified due to factors such as rapid dissemination, audience size, and permanence of digital content (Hancock, Landrigan, & Silver, 2007). Viral emotional content, especially anger or outrage, can catalyze collective emotional responses, sometimes escalating into online harassment or mob behavior (Papacharissi, 2015).

Research on emotional contagion in social networks highlights how digital emotional expressions influence the emotions of others, reinforcing cycles of emotional amplification or attenuation (Kramer et al., 2014). This contagion effect underscores the social responsibility linked to emotional regulation in digital spaces.

Furthermore, the cultural norms and platform affordances shape acceptable emotional expressions. For example, Twitter’s brevity encourages concise, often emotionally charged statements, while Facebook supports longer, more reflective posts (Papacharissi, 2015). Understanding these contextual factors is crucial for effective EI application.

2.5. Summary and Research Gaps

The literature affirms that Emotional Intelligence plays a vital role in managing emotions in both traditional and digital communication contexts. However, there remain notable gaps in understanding the cyclical process of emotional reception and expression specific to digital environments. Existing studies focus on isolated elements such as emotional recognition or regulation strategies but rarely conceptualize the dual process metaphorically as an Inbox and Outbox.

Additionally, while the online disinhibition effect and emotional contagion are well documented, how EI specifically moderates these phenomena requires further empirical exploration. The influence of platform design and cultural context on EI-mediated emotional processes also remains underexplored.

This paper seeks to address these gaps by developing and empirically testing the Inbox Emotions and Outbox Blast framework, focusing on the role of EI in regulating digital emotional cycles. The following sections will present the study’s methodology and findings aimed at contributing to this emerging research agenda.

5. Qualitative Findings

The qualitative component of this study was designed to deepen the understanding of the emotional mechanisms, interpretive behaviors, and digital communicative norms among youth gang members in Bangladesh. Through twenty in-depth interviews (IDIs) and five focus group discussions (FGDs) with 6–8 participants each, we explored subjective meanings, affective triggers, and the use of social media as a terrain for emotional performance and conflict. The findings were analyzed using thematic analysis, generating key themes that align with the constructs of emotional intelligence, digital emotional reactivity, and digital projection (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

5.1. Theme 1: Emotional Encoding and Misinterpretation in Digital Communication

One of the dominant themes was the ambiguity and emotional volatility caused by digital language and non-verbal cues such as emojis, reaction icons, and read receipts. Participants consistently emphasized that interpreting meaning behind text messages or emojis was a source of emotional tension and conflict.

For instance, one participant noted:

‘When someone sends ‘k’ or just likes my message, I feel like he’s ignoring me. That’s disrespect in our world.’

Another explained:

‘A single angry emoji can start a war. It’s not just an icon; it shows what’s in their heart.’

The interpretative flexibility of digital symbols, exacerbated by the lack of tone and physical gestures, often led to feelings of emotional neglect, misjudgment, or provocation. This aligns with research showing that digital communication—especially among emotionally charged communities—is prone to misunderstanding and escalated response (Suler, 2004; Papacharissi, 2012).

5.2. Theme 2: Ego Surveillance, Status Monitoring, and Emotional Competition

A recurring motif among youth gang members was the practice of ego surveillance—closely monitoring reactions, comments, and digital behavior of peers to assess loyalty, status, and potential disrespect. The digital arena served as a public stage for emotional validation, power negotiation, and loyalty testing.

A 19-year-old participant from Dhaka explained:

‘I check who shares my post, who comments fire or reacts with anger. If one of my crew reacts with ‘haha’ on my post, I question his loyalty.’

This continuous state of digital monitoring creates an emotional ecosystem driven by anxiety, competitiveness, and strategic performance. Gang members use their inboxes and profiles to construct a digital hierarchy based on visibility, reaction count, and support.

One FGD participant elaborated:

‘If my brother doesn’t tag me in his photo or birthday status, it means he’s moving away. That hurts more than a slap.’

This emotional surveillance fuels heightened sensitivity and leads to overinterpretation of minor digital behaviors, often escalating into interpersonal conflicts or retaliatory ‘outbox blasts’ in the form of indirect posts, voice messages, or digital exclusion.

5.3. Theme 3: Digital Provocation, Trigger Words, and Emotional Contagion

Participants frequently referred to specific trigger words and digital gestures that instigated emotional overdrive or retaliatory action. Terms such as ‘boka,’ ‘poka,’ ‘nob,’ or ‘beta’ carried emotional charge far beyond their literal meaning. They were interpreted as attacks on masculinity, loyalty, or status.

A participant from Chattogram noted:

‘He commented ‘beta’ under my photo. I couldn’t sleep the whole night. I dropped a status, then we fought the next day.’

These emotionally loaded terms, when used on social media, ripple through digital networks and generate what can be called ‘emotional contagion,’ a process where collective affect amplifies individual emotion (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1993). This amplification was particularly strong within WhatsApp and Messenger groups, where screenshots, reaction chains, and group ganging intensified emotional pressure.

FGD data revealed that such digital taunts were often staged to trigger emotional instability and extract performative aggression as a proof of allegiance:

‘They test you online. If you stay silent, they think you’re weak. You must reply, react, or blast.’

5.4. Theme 4: Outbox Blasts as Digital Catharsis and Warfare

A profound discovery was the use of digital platforms not merely for communication but for emotional release and catharsis. ‘Outbox blasts’—posts, stories, or voice notes—were frequently described as mechanisms for emotional ventilation, especially when face-to-face confrontation was either impossible or strategically postponed.

A participant from Khulna explained:

‘Sometimes I feel like punching someone, but I hold it in. Then I go live or post something direct. It makes me feel light.

Another described it as warfare:

‘My status is my weapon. I use words like bullets.’

This digital catharsis served multiple functions: expressing anger, asserting identity, signaling group alignment, or initiating emotional retaliation. These behaviors are deeply rooted in masculine performativity and the projection of emotional toughness (Connell, 2005).

Interestingly, some participants admitted that they intentionally staged digital meltdowns or emotional posts to manipulate others or provoke guilt:

‘When I post something sad or angry, I know they’ll come running. It’s a game too.’

5.5. Theme 5: Inbox Emotions and Mental Health Shadows

Although most participants portrayed emotional outbursts as part of gang dynamics, many quietly admitted feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression. The inbox—whether on Messenger or WhatsApp—became a private zone of emotional overflow.

A 17-year-old girl gang member from Sylhet shared:

‘My inbox is where I cry. I don’t cry in front of anyone. I send voice notes when I’m low.’

Some male participants discussed how late-night chats became sites of vulnerability, confession, and trust-building. These emotional exchanges rarely surfaced in outbox behavior, suggesting a split between private and performative emotion.

Quote:

‘People think I’m a hard guy because of my posts. But I talk to my girlfriend and tell her everything. She’s my inbox emotion.’

This finding is consistent with Goleman’s (1995) conceptualization of emotional intelligence, which includes internal awareness and self-regulation. For many participants, emotional intelligence was more evident in private digital dialogues than public digital expressions.

5.6. Theme 6: Emotional Rituals and Symbolic Digital Practices

Gang members were found to engage in symbolic digital rituals such as coordinated ‘react storms’ (everyone liking a post together), ‘DP wars’ (changing profile pictures in rivalry), or emoji duels. These digital rituals serve emotional and cultural purposes.

One participant described:

‘When one of our bros is attacked online, we all comment the fire emoji to show heat. That’s our ritual.’

These symbolic acts reinforce group cohesion, emotional allegiance, and the affective economy of digital interaction. Such rituals transform digital platforms into cultural spaces governed by codes, emotional triggers, and symbolic aggression.

5.7. Summary of Qualitative Insights

The qualitative findings reveal that the emotional universe of youth gang members in Bangladesh is profoundly shaped by their digital interactions. Emotional intelligence manifests in unconventional ways—through code-switching between inbox vulnerability and outbox aggression, emotional surveillance of peers, and use of symbolic language and rituals.

In short, the inbox becomes a mirror of compressed emotional expression, while the outbox becomes a stage for emotional explosion—a tension that drives much of the digital drama and interpersonal violence in these networks.

This thematic richness complements the quantitative findings, providing explanatory depth into why lower emotional intelligence correlates with higher digital reactivity and expressive aggression. These behaviors are not irrational but embedded in cultural logics of masculinity, loyalty, honor, and digital reputation.

5.8. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

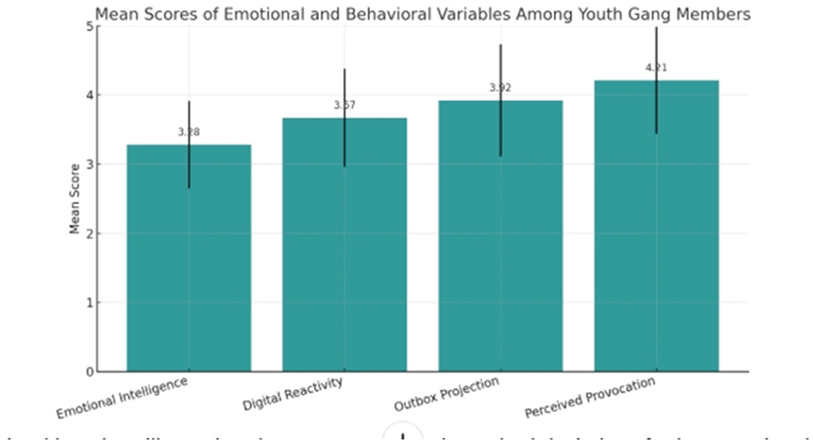

Quantitative findings on low EI, high DER, and expressive OE were supported by narrative insights showing emotional misinterpretation, honor culture, and cathartic expression through digital platforms.

A meta-inference is that youth gangs in Bangladesh use digital spaces both as emotional battlegrounds and arenas for identity negotiation. The inbox becomes the site of emotional compression, while the outbox is the site of emotional explosion.

5.9. Discussion of Findings

This study reveals that youth gang members in Bangladesh exhibit emotional patterns strongly mediated by digital platforms. Consistent with Goleman’s (1995) theory, low EI correlates with heightened reactivity and externalized emotional expression. These digital behaviors are not random but embedded in gang norms, digital subcultures, and reputational economies (Papacharissi, 2012).

The regression results validate the hypothesis that digital reactivity and perceived provocations drive expressive emotional behaviors. Qualitative findings add depth by showing how symbols, status, and slang intensify these reactions. This supports the idea that the digital world, for youth gangs, is not separate from but integrally linked to real-world identity, honor, and social standing.

5.10. Limitations of the Data Analysis

Social desirability bias in self-reporting emotional triggers.

Underrepresentation of female gang dynamics.

Limited generalizability to rural or non-gang youth.

5.11 Implications for Policy and Practice

Digital literacy programs should incorporate emotional literacy and conflict resolution training.

Intervention frameworks must be platform-specific, using culturally resonant language.

Counselling support should integrate understanding of online emotional behaviors as precursors to real-world violence.