1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women globally [

1]. In 2024, it is estimated that approximately 310.720 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in women in the United States, along with about 56.500 cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Breast cancer continues to account for around 30% of all new cancer diagnoses in U.S. women. Mortality remains significant, with an expected 42.250 female deaths and 530 male deaths out of an estimated 2.790 new male cases. Despite these numbers, the five-year relative survival rate for breast cancer diagnosed at a localized stage exceeds 99%. This rate declines to 87% for regional-stage disease and drops further to 32% when diagnosed at a distant, metastatic stage. Encouragingly, breast cancer mortality has declined by 44% since 1989, resulting in over 517.900 averted deaths. However, concerning trends include a rising incidence among younger women under 50 years, increasing at an annual rate of 1.4% between 2012 and 2021 [

2]. Significant racial disparities also persist, with Black women experiencing a 40% higher mortality rate compared to White women, largely due to later-stage diagnoses and unequal access to quality care [

3].

Tumorgenesis is a multistep process, with oncogenic mutations in a normal cell conferring clonal advantage as the initial event. However, despite pervasive somatic mutations and clonal expansion in normal tissues, their transformation into cancer remains a rare event, indicating the presence of additional driver events for progression to an irreversible, highly heterogeneous, and invasive lesion [

4]. Advances in molecular biology and genomics have revolutionized our understanding of tumor biology, yet many mechanisms contributing to breast cancer onset and progression remain poorly understood. Researchers are focusing on encompassing diverse aspects such as tumor stemness, intra-tumoral microbiota, and circadian rhythms [

5]. Among the genomic elements receiving increasing attention are endogenous retroelements—particularly human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) [

6].

HERVs are sequences derived from ancient retroviral infections that have been integrated into the human genome over millions of years. Although most are defective and transcriptionally silent due to mutations and epigenetic repression, certain HERV families, especially human endogenous retrovirus type K [HERV-K (HML-2)], retain the ability to be transcribed under specific physiological and pathological conditions. In cancer biology, aberrant reactivation of HERVs has been reported in several malignancies, including melanoma, testicular cancer, and breast cancer [

6,

7,

8].

The HERV-K (HML-2) subgroup is the most biologically active and has been implicated in oncogenesis through mechanisms such as insertional mutagenesis, induction of inflammation, and modulation of the immune microenvironment. The transcriptional activity of HERVs in tumor tissues may provide insights into novel oncogenic pathways and serve as a source of tumor-specific antigens [

10,

11]. The HERV-K (HML-2) is found to be expressed in various subtypes of breast cancer. This retrovirus was integrated into the primate genome approximately 55 million years ago, presenting a challenge for potential immunotherapy approaches for breast cancer. Recent studies have indicated that several endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) have been re-activated in tumors, with many exhibiting overexpression in cancerous tissues while showing low or undetectable levels in normal tissues [

11,

12].

This study focuses on evaluating the differential expression of HERVs in breast cancer versus normal breast tissue using publicly available RNA-Seq datasets. We also assessed the effect of treatment on HERV expression levels, with the ultimate goal of exploring HERVs as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in breast cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Acquisition

RNA-Seq datasets were obtained from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) [

13]. All data has been securely downloaded into password-protected directories of the SRA. The SRA Toolkit was obtained through Linux to facilitate access to SRA data. This toolkit enables the creation of next-generation sequencing files in the specified format and cloud storage.

RNA-Seq data for breast ductal carcinoma (BAM files) along with their corresponding clinical information were sourced from the NCBI SRA. The paired-end FASTQ files for each sample were downloaded in SRA format and subsequently converted to FASTQ format using the fastq-dump command from the SRA Toolkit. Samples included 11 breast cancer tissues (various subtypes including ductal carcinoma and triple-negative) and 6 healthy breast tissues.

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

The paired-end reads in FASTQ format were aligned to the human reference genome, hg19 using bowtie2 with default settings The paired-end reads in FASTQ format were also aligned to the pseudogenome which was made using the 5’ and 3’ LTRs (long terminal repeat) coordinated of HERV-K(HML-2) as described by Subramanian et al. [

14]. Mapping to this pseudogenome allowed for quantification of reads aligning to HERV-host junctions.

The resulting alignments were subsequently converted to the standard BAM file format utilizing samtools with its default configurations. The expression of HERV-K-human junctions was obtained from raw reads through bedtools multicov, also employing default settings. Following this, the mapped reads were quantified and normalized using the specified formula:

A pseudogenome was constructed using the coordinates of LTRs from HERV-K(HML-2) to identify the expression of LTR-host junctions [

15]. The LTR coordinates utilized for the development of the pseudogenome were detailed by Subramanian et al. The incorporation of HERVs into the human genome leads to areas that consist of both partial LTR sequences and partial human sequences, known as LTR-host junctions. Various tools were employed to analyze these datasets, including SRA-toolkit, Samtools, Bowtie, IGV, and BedTools, which is a software specifically designed to quantify the number of reads associated with each gene.

To incorporate the integration sites for the pseudogenome, partial human sequences were utilized, commencing and concluding at a defined distance of bases from the beginning and end of LTRs (the coordinates for the start and end of LTRs are provided in the attached Excel file). Consequently, a Bed file was generated by adjusting the length of reads by 66% to encompass junctions. The formula is outlined below:

chr(1,2,3, etc) LTR start-66% length LTR start+66% length

chr(1,2,3, etc) LTR end-66% length LTR end+66% length

for any LTR of HERV.

Command “bedtools getfasta” [

16] was used with default settings, in order to create a fasta file including the LTR-host junction sequences that was used as the pseudogenome. As far as it concerns the alignment of pseudogenome, use the command:

“bowtie2 -t -x bowtie2/hg19 ncbi/public/sra/....fastq -S bowtie2/....sam”

Furthermore, downloading SAMtools was used for mapping the pseudogenome, via the following commands:

“.sam file” was converted to “.bam file” by means of the commands:

“samtools view -S -b bowtie2/....sam > bowtie2/....bam”

After that, files were sorted with samtools by means of the commands:

“samtools sort bowtie2/....bam -o bowtie2/..._sorted.bam”

“samtools index bowtie2/..._sorted.bam” [

17].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed in IBM SPSS 24. Chromosomes were represented using frequencies. Normalized coverage of integration sites was calculated using BEDTools and custom scripts. Statistical significance between groups was assessed using independent samples t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. RNASeq Datasets

Transcriptome data were examined from 11 patients with invasive ductal carcinoma breast cancer, as detailed in

Table 1, alongside 6 healthy individuals, presented in

Table 2.

In

Table 3 and

Table 4, the raw reads and overall alignment rate from the alignment of any RNA-seq to Human genome (hg19) are presented for breast cancer patients and healty tissue respectively. Pseudogenome reads came from alignment of any RNA sequences to Pseudogenome. Normalized coverage of integration sites:

3.2. Elevated HERV Expression in Breast Cancer

Mean normalized coverage of HERV integration sites was significantly higher in breast cancer tissues (M = 0.000013) than in healthy tissues (M = 0.000001, p = 0.009) (

Table 5).

3.3. Effect of Treatment

Patients who had not received treatment exhibited significantly higher HERV expression (mean rank = 9.00) compared to treated patients (mean rank = 4.29, p = 0.023) (

Table 6).

3.4. Visualization

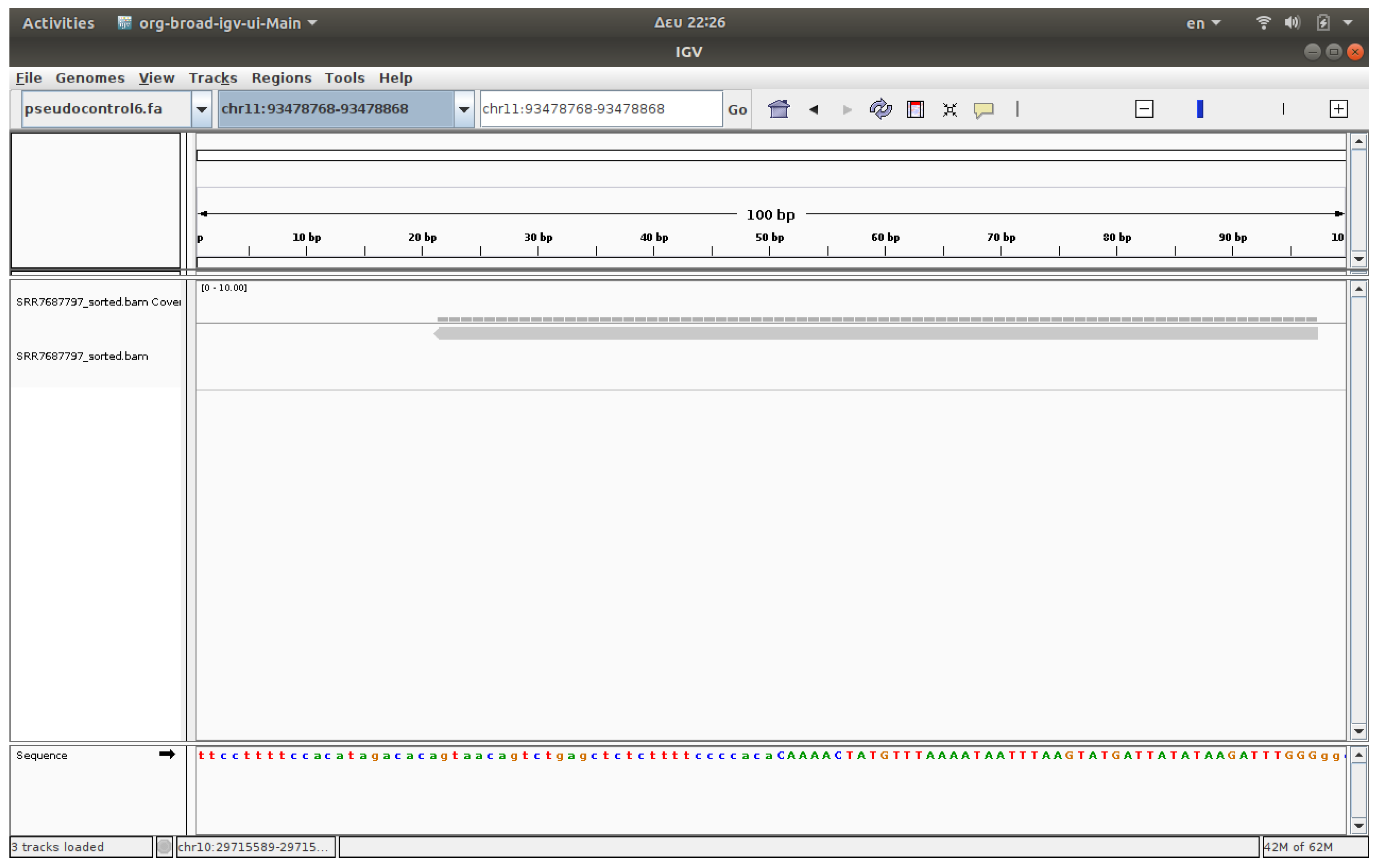

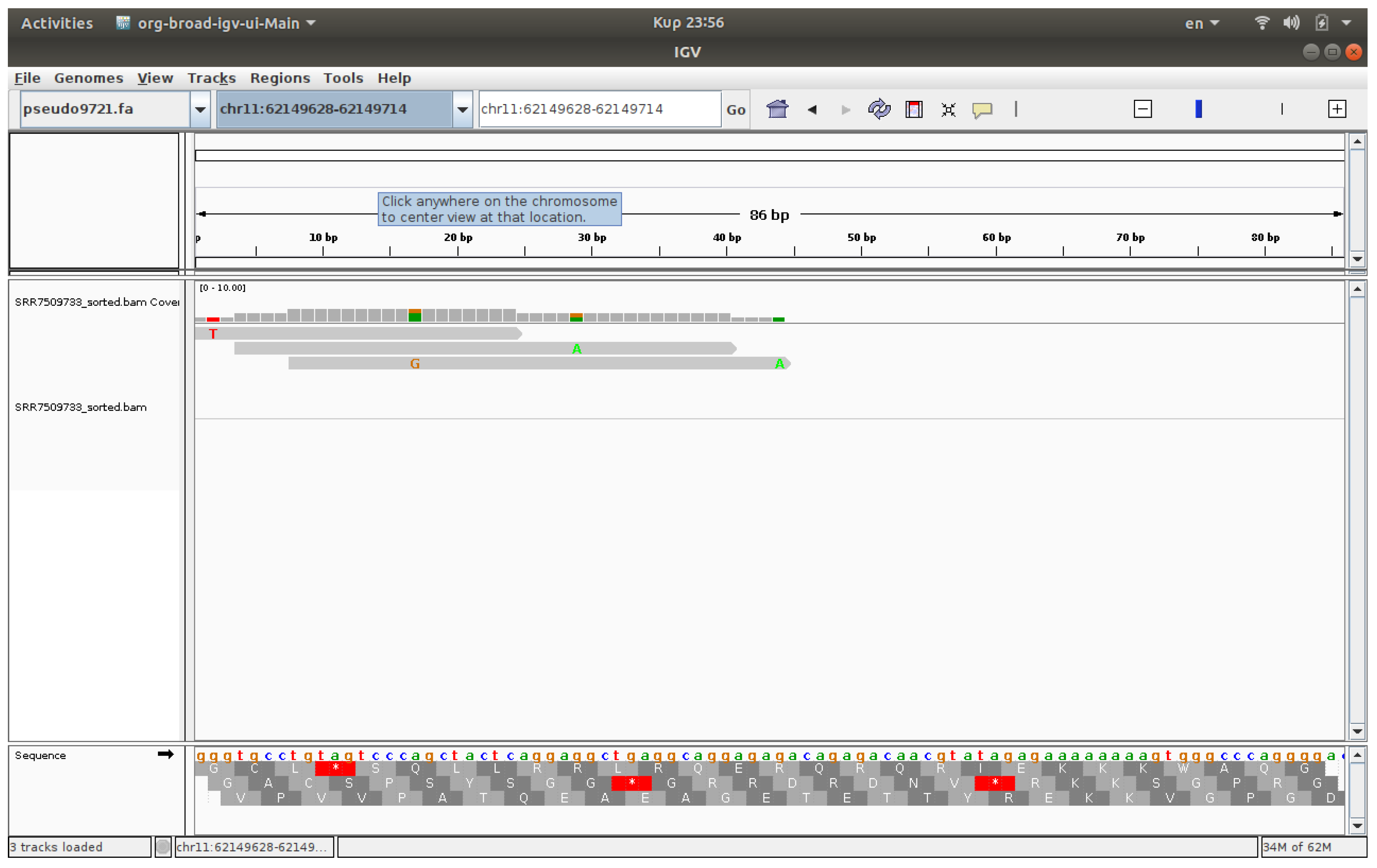

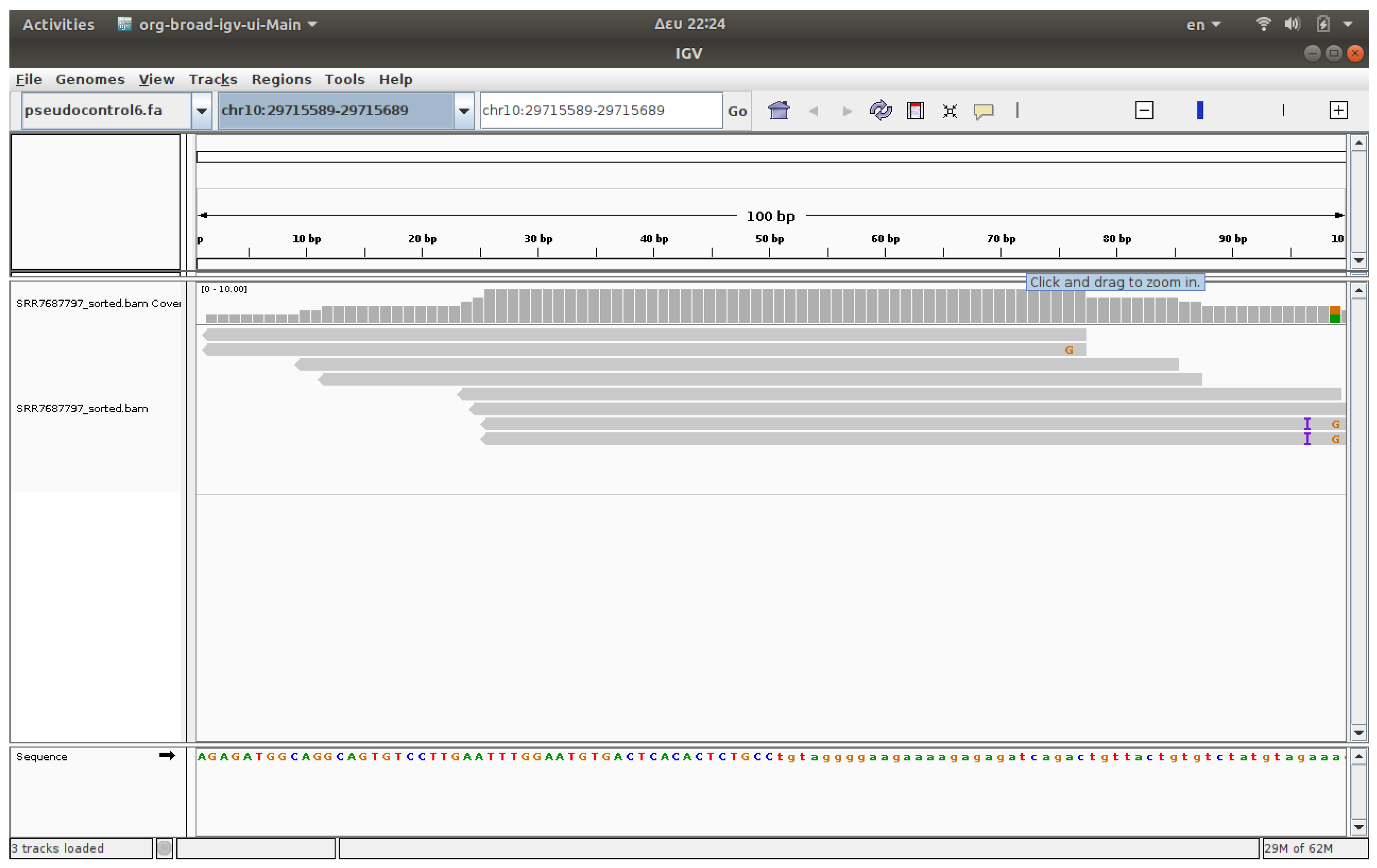

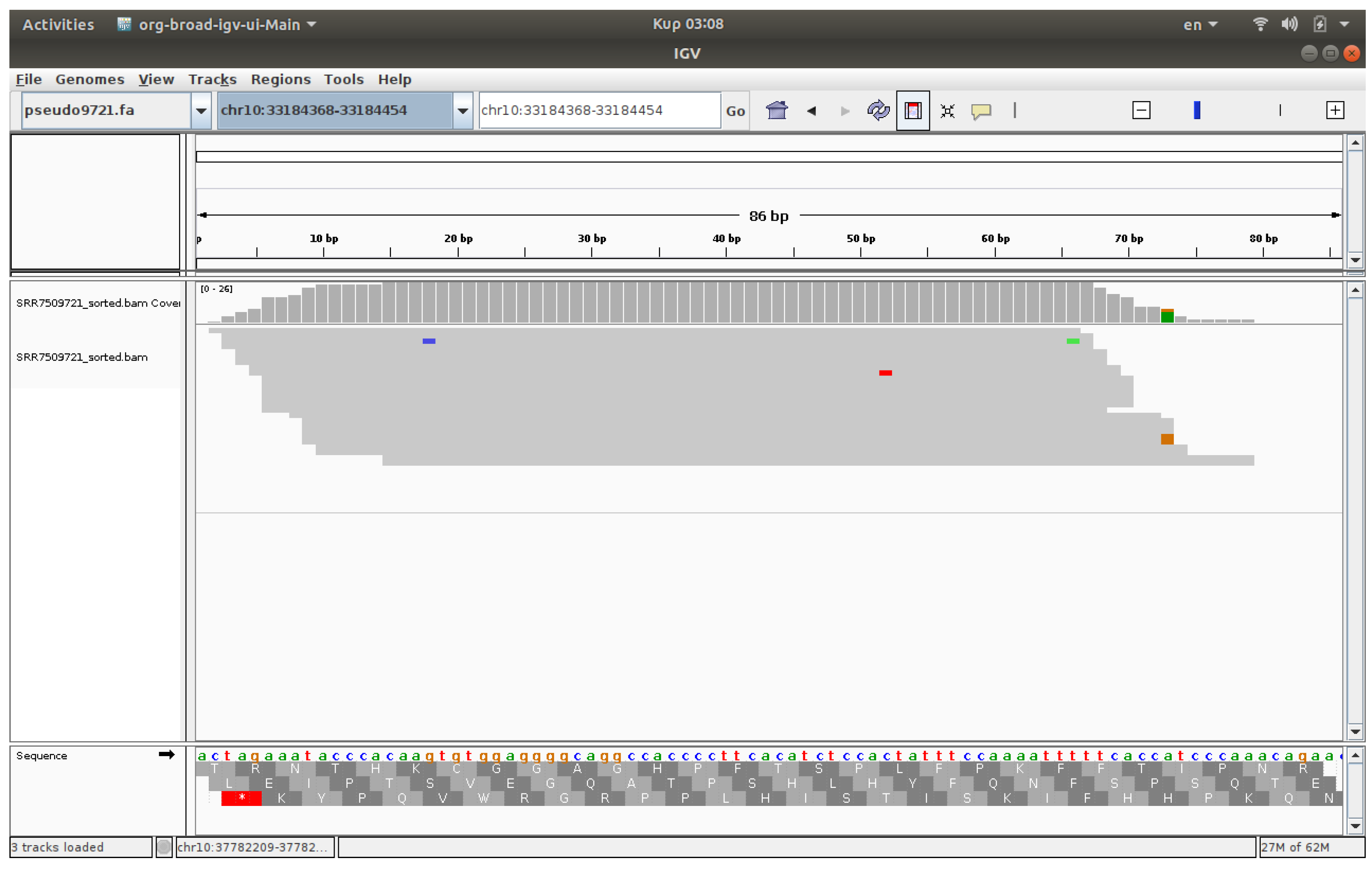

The visualization of files was conducted using IGV, a software application that enables the observation of reads on chromosomes [

17,

18]. The associated IGV web application enables users to upload FASTQ files and receive visualized outcomes. IGV genome browser confirmed increased read accumulation at specific HERV loci in cancer samples versus healthy controls (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The present analysis investigated the expression of HERVs in breast cancer tissue compared to normal breast tissue. Furthermore, it explored the variations in normalized coverage of integration sites between breast cancer patients and healthy controls, as well as the differences between treated and untreated breast cancer cases.

The results provide compelling evidence that HERVs, specifically HERV-K (HML-2), are significantly overexpressed in breast cancer tissues compared to normal breast tissues. This differential expression pattern supports a growing body of literature suggesting that HERVs play a role in the etiology and progression of cancer [

19,

20,

21].

Several mechanisms may explain the upregulation of HERVs in malignancies. Hypomethylation of HERV sequences and surrounding genomic regions, a common epigenetic alteration in cancer, may reactivate normally silenced proviral elements. Additionally, the tumor microenvironment, characterized by oxidative stress, cytokine production, and immune dysregulation, can further promote HERV expression [

22,

23]. Specifically in breast cancer, the envelope protein of HERV-K(HML-2) serves as the most effective diagnostic tool for breast cancer, as it is found in breast cancer tissues while being absent or present at significantly lower levels in normal breast tissue [

24]. Also, the presence of HERV-K (HML-2) antibodies and mRNA serves as an indicator of early-stage breast cancer, with a subsequent rise suggesting the occurrence of metastasis [

20,

25]

The observed reduction in HERV expression among patients who received treatment is particularly noteworthy. It suggests that chemotherapy or other therapeutic regimens may suppress HERV activity, potentially by restoring epigenetic silencing mechanisms or by targeting proliferative cancer cells with elevated HERV transcription [

19,

26,

27]. This raises important questions regarding the therapeutic targeting of HERVs, both directly and indirectly [

28].

While this study offers valuable insights, limitations include the modest sample size and the reliance on public datasets without experimental validation. Further research is necessary to elucidate the functional consequences of HERV expression and its interaction with oncogenic signaling pathways.

5. Implications for Practice and Future Directions

The findings of this study have several clinical and research implications.

In clinical practice, HERV-K expression could serve as a non-invasive biomarker for early breast cancer detection [

24]. The observed decrease in HERV expression following treatment suggests potential utility in tracking therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, stratifying patients by HERV expression profiles may aid in developing tailored treatment strategies and enhancing personalized medicine approaches. The field of personalized medicine is experiencing a significant transformation due to the incorporation of multi-omics data, which primarily includes genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [

29].

From a research perspective, laboratory-based validation is essential to confirm the functional role of HERVs in tumor growth and immune modulation. The immunogenic nature of HERV-derived proteins also presents opportunities for the development of novel immunotherapies, including cancer vaccines and CAR-T cell therapy [

30]. Lastly, longitudinal studies monitoring HERV expression over time could provide valuable insights into disease progression, recurrence, and metastasis.

6. Conclusions

This transcriptomic analysis demonstrates significant overexpression of HERVs in breast cancer tissues, particularly in untreated patients. HERVs expression profiling may aid in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response monitoring in breast cancer care. With further validation, HERVs could become valuable biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dimitra Bartzi; Data curation, Dimitra Bartzi, Anastassios Philippou and Michael Koutsilieris; Formal analysis, Dimitra Bartzi; Investigation, Dimitra Bartzi; Methodology, Dimitra Bartzi; Resources, Dimitra Bartzi, Anastassios Philippou and Michael Koutsilieris; Software, Dimitra Bartzi; Supervision, Michael Koutsilieris; Validation, Dimitra Bartzi and Ioanna Tsatsou; Visualization, Dimitra Bartzi and Ioanna Tsatsou; Writing – original draft, Dimitra Bartzi, Ioanna Tsatsou and Michael Koutsilieris; Writing – review & editing, Dimitra Bartzi, Anastassios Philippou and Ioanna Tsatsou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; Soerjomataram, I. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrill, R.M.; Gibbons, I.S. Inequality in Female Breast Cancer Relative Survival Rates between White and Black Women in the United States. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, X.; Yi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Lin, D.; Wu, C. Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2024 9, 149. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K. D. Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2024, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cong, Y.S. Human endogenous retroviruses in development and disease. Computational and structural biotechnology journal 2021, 19, 5978–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geis, F.K.; Goff, S.P. Silencing and Transcriptional Regulation of Endogenous Retroviruses: An Overview. Viruses 2020, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, C.; Tsang, J.; Bireau, C.; Heidmann, T.; Dewannieux, M. A human endogenous retrovirus-derived gene that can contribute to oncogenesis by activating the ERK pathway and inducing migration and invasion. PLoS pathogens 2017, e1006451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Sechi, L. A. , & Kelvin, D. J. Human Endogenous Retrovirus K (HML-2) in Health and Disease. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar]

- Dervan, E.; Bhattacharyya, D.D.; McAuliffe, J.D.; Khan, F.H.; Glynn, S.A. Ancient Adversary - HERV-K (HML-2) in Cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 2021, 1, 658489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.P.; Wildschutte, J.H.; Russo, C.; Coffin, J.M. Identification, characterization, and comparative genomic distribution of the HERV-K (HML-2) group of human endogenous retroviruses. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesion, M.; Williams, Z.H.; Subramanian, R.P.; Kuperwasser, C.; Coffin, J.M. (2018). Promoter expression of HERV-K (HML-2) provirus-derived sequences is related to LTR sequence variation and polymorphic transcription factor binding sites. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Sequence Read Archive (SRA). National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

- Subramanian, I.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Jere, A.; Anamika, K. Multi-omics Data Integration, Interpretation, and Its Application. Bioinformatics and biology insights 2020, 14, 1177932219899051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belshaw, R.; Pereira, V.; Katzourakis, A.; Talbot, G.; Paces, J.; Burt, A.; Tristem, M. Long-term reinfection of the human genome by endogenous retroviruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 101,4894–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/content/tools/getfasta.

- Bartzi, D. Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVS) Transcriptomics in human breast cancer. Master thesis. Library of the School of Health Sciences, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 2021. https://pergamos.lib.uoa.gr/uoa/dl/frontend/en/browse/2938645#contents.

- Integrative Genomics Viewer https://igv.

- Costa, B.; Vale, N. Exploring HERV-K (HML-2) Influence in Cancer and Prospects for Therapeutic Interventions. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24(19), 14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanning, G.L.; Malouf, G.G.; Zheng, X.; Esteva, F.J.; Weinstein, J.N.; Wang-Johanning, F.; Su, X. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus-K is strongly associated with the basal-like breast cancer phenotype. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 41960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, S.R.; Valdez, M.J.M.; Govindarajan, V.; Seetharam, D.; Doucet-O’Hare, T.T.; Heiss, J.D.; Shah, A.H. The Role of HERV-K in Cancer Stemness. Viruses 2022, 14(9), 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, A.; Roy, F.; Freeman, M.; Coffin, J.M. Widespread expression of the ancient HERV-K (HML-2) provirus group in normal human tissues. PLoS biology 2022, 20(10), e3001826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasova, E.A.; Chen, L.; Childs, R.W. Mechanistic regulation of HERV activation in tumors and implications for translational research in oncology. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2024, 14, 1358470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wei, H.; Wei, Y.; Tan, A.; Chen, X.; Liao, X.; Xie, B.; Wei, X.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Dai, S.; Khan, A.; Pang, X.; Hassan, N.M.A.; Xiong, K.; Zhang, K.; Leng, J.; Lv, J.; Hu, Y. Screening and Identification of Human Endogenous Retrovirus-K mRNAs for Breast Cancer Through Integrative Analysis of Multiple Datasets. Frontiers in oncology 2022, 12, 820883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Johanning, F.; Li, M.; Esteva, F.J.; Hess, K.R.; Yin, B.; Rycaj, K.; Plummer, J.B.; Garza, J.G.; Ambs, S.; Johanning, G.L. Human endogenous retrovirus type K antibodies and mRNA as serum biomarkers of early-stage breast cancer. International journal of cancer 2014, 134(3), 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simula, E.R.; Jasemi, S.; Cossu, D.; Fais, M.; Cossu, I.; Chessa, V.; Canu, M.; Sechi, L.A. Human Endogenous Retroviruses as Novel Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Vaccines 2025, 13, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannert, N.; Hofmann, H.; Block, A.; Hohn, O. HERVs New Role in Cancer: From Accused Perpetrators to Cheerful Protectors. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stricker, E.; Peckham-Gregory, E.C.; Scheurer, M.E. HERVs and Cancer-A Comprehensive Review of the Relationship of Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Human Cancers. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logotheti, S.; Stiewe, T.; Georgakilas, A.G. The Role of Human Endogenous Retroviruses in Cancer Immunotherapy of the Post-COVID-19 World. Cancers 2023, 15, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).