Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

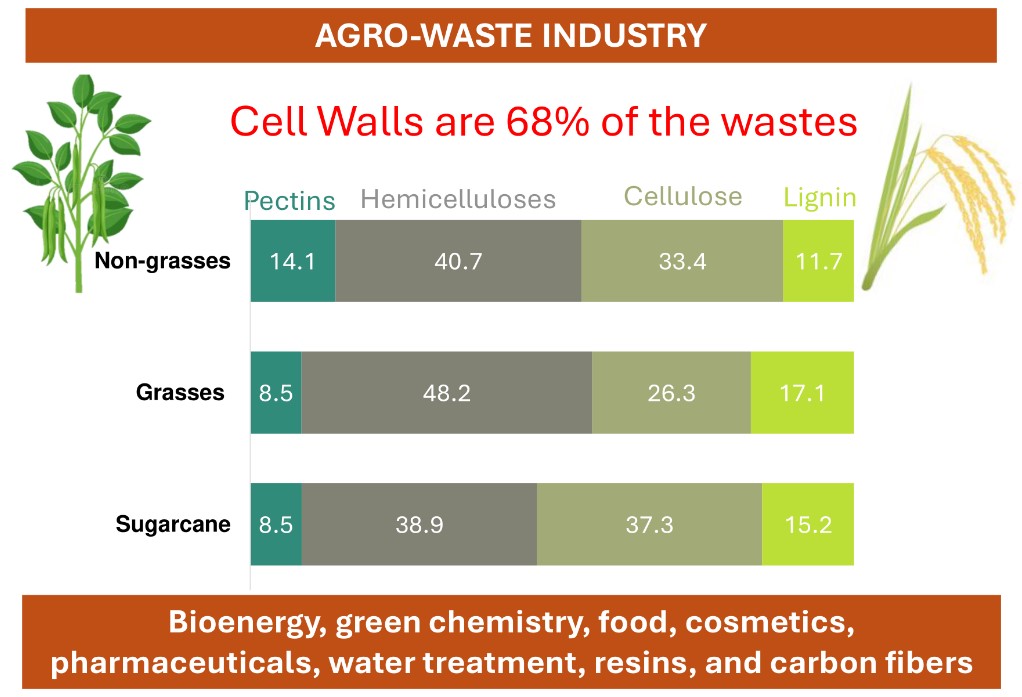

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agro-Wastes Evaluated

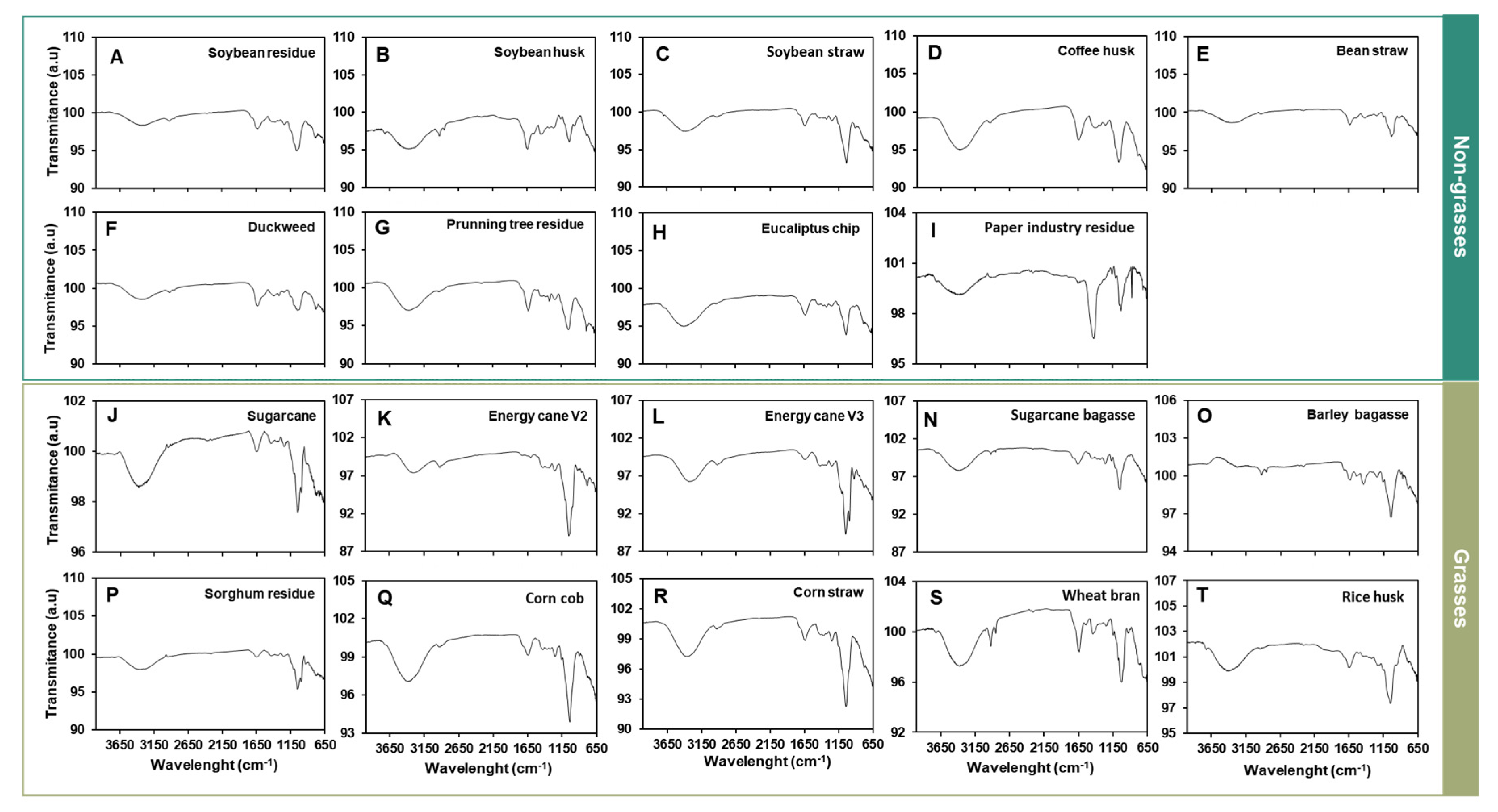

2.2. Compositional Characterization by Fourier Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

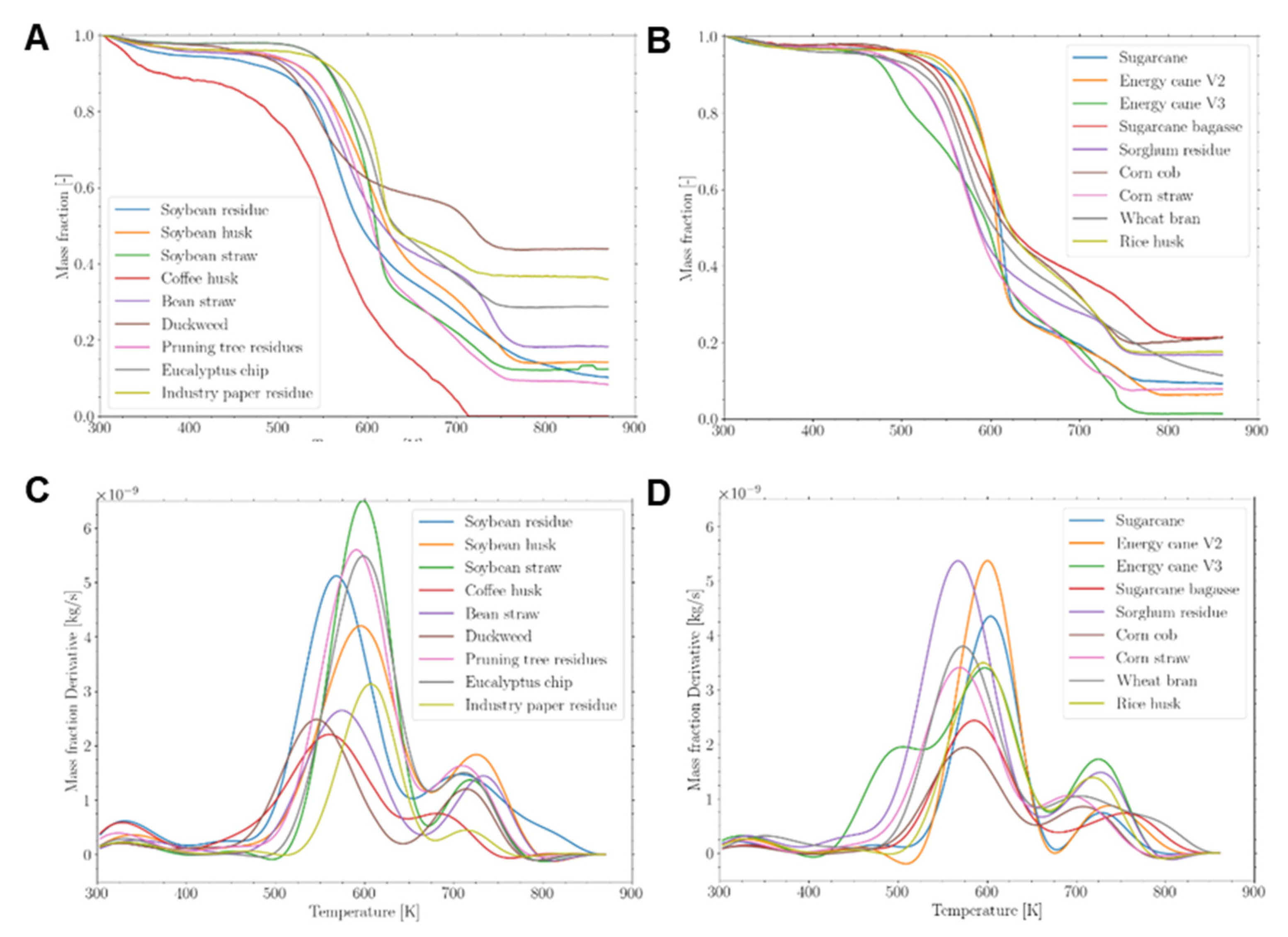

2.3. Elemental Composition and Calorific Power

2.4. Lignin Quantification

2.5. Cell Wall Obtention and Fractionation

2.6. Neutral Monosaccharides Hydrolysis and Quantification

2.7. Uronic Acid Determination

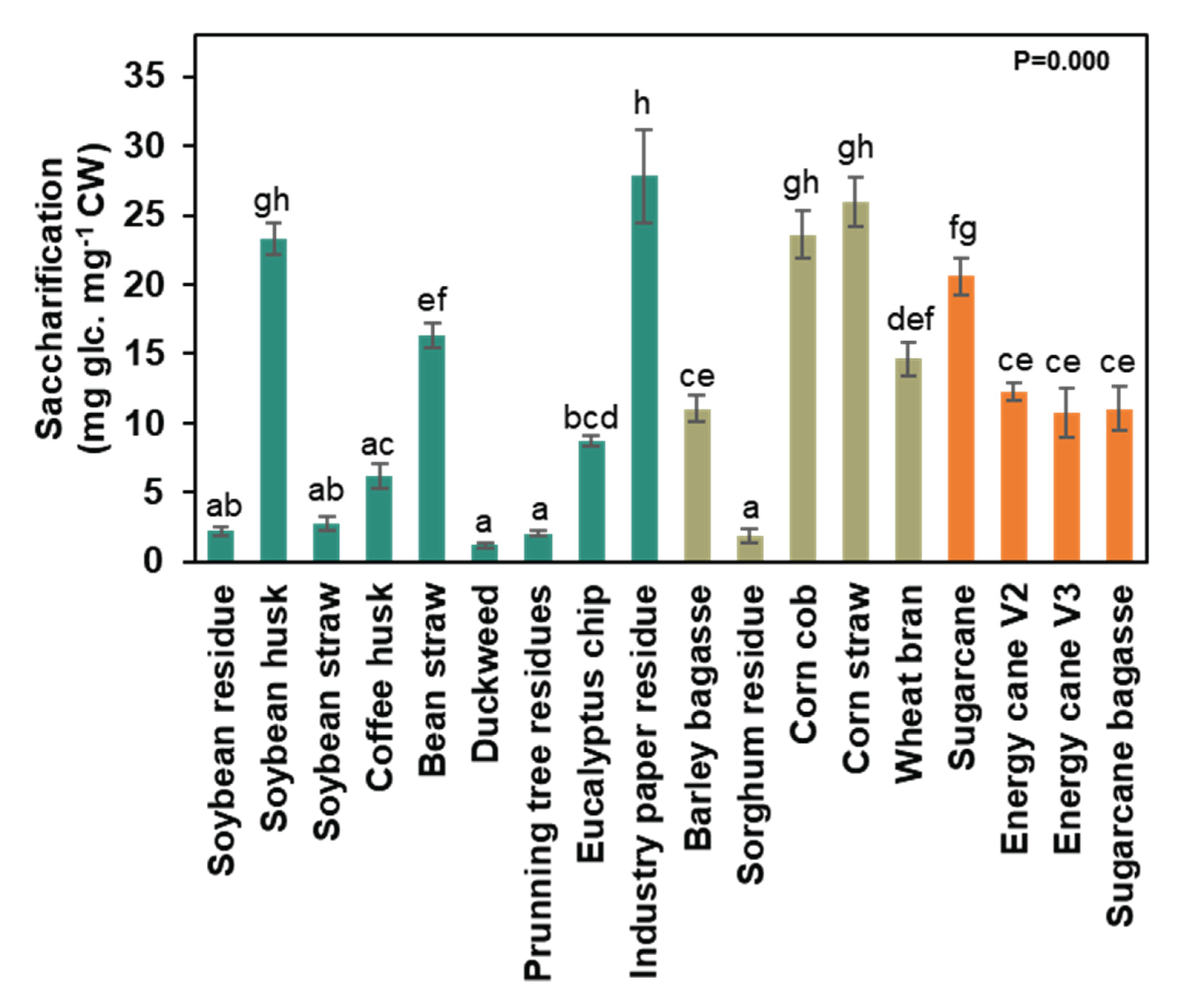

2.8. Cell Wall Saccharification

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

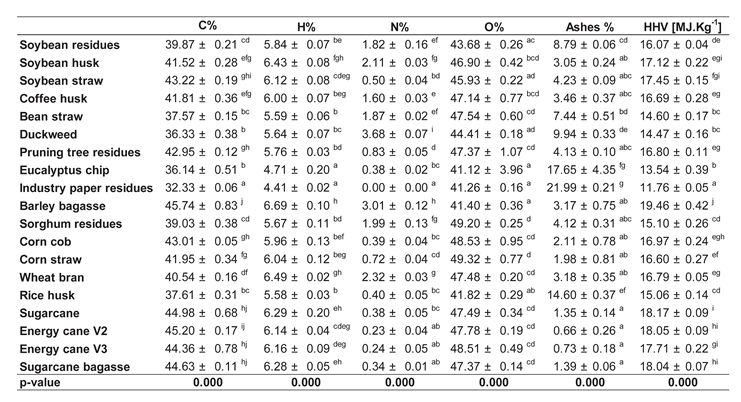

3.1. Agro-Wastes Have Similar Industrial Characteristics

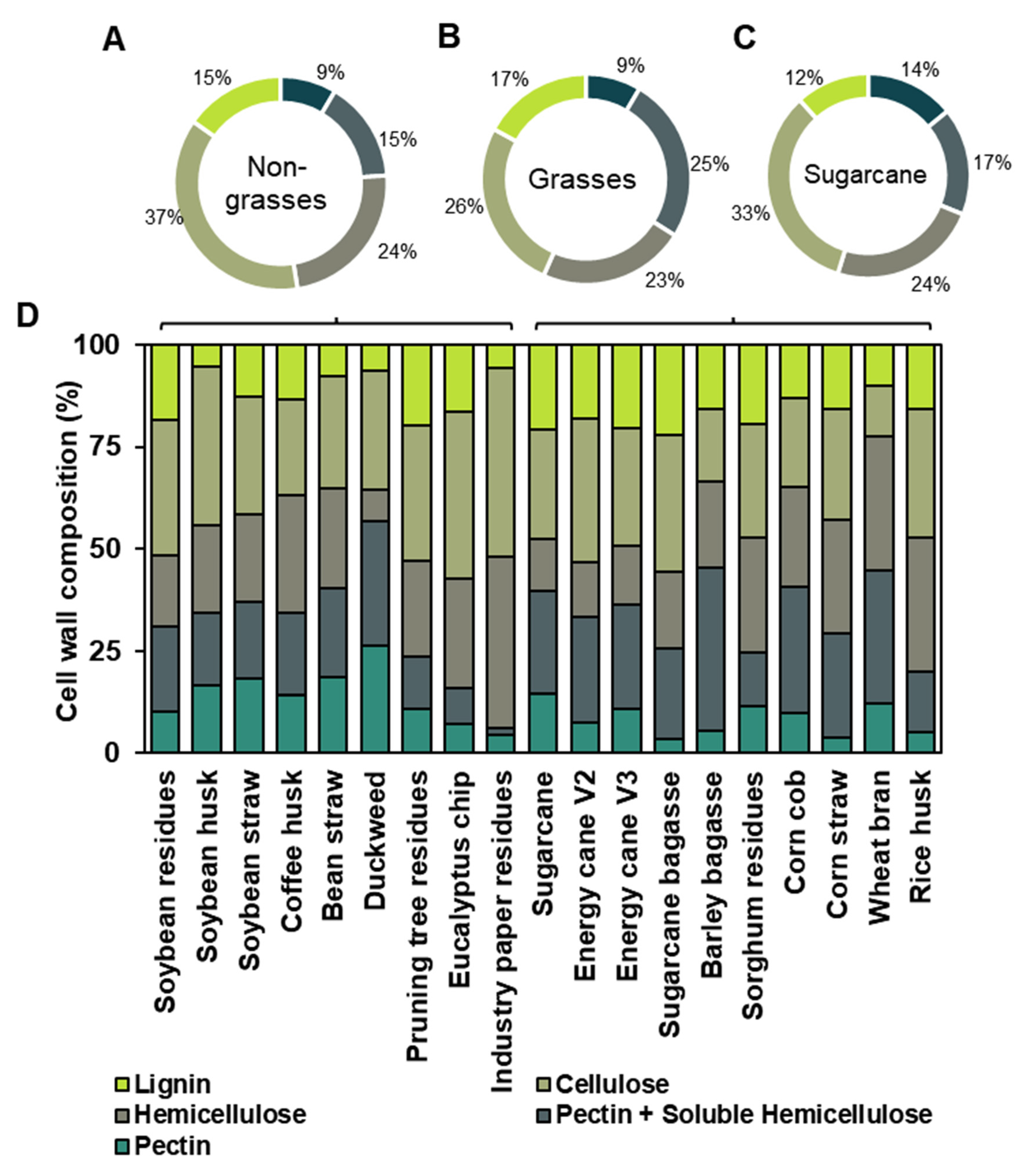

3.2. Agro-Wastes Have Different Proportions of Cell Wall Domains

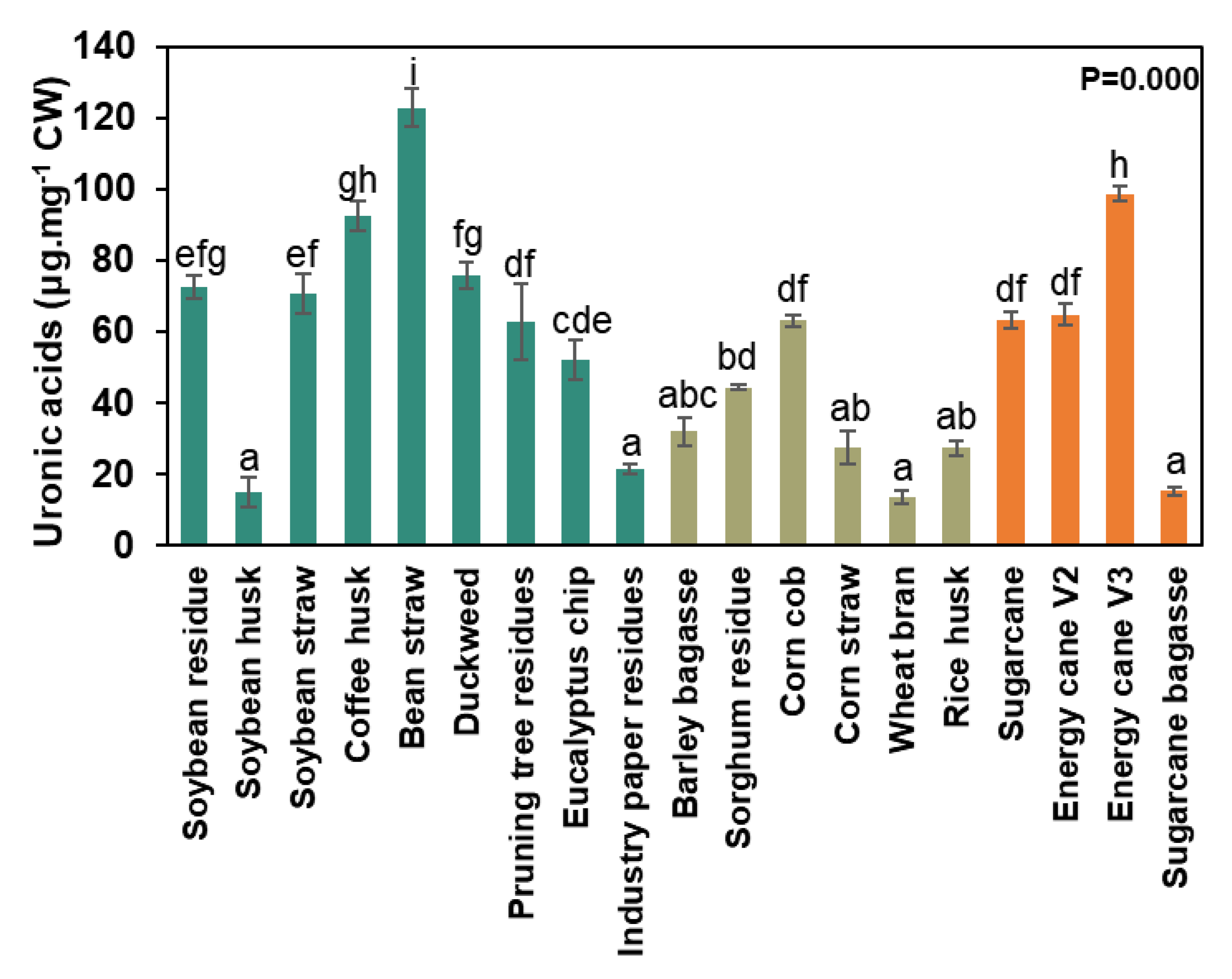

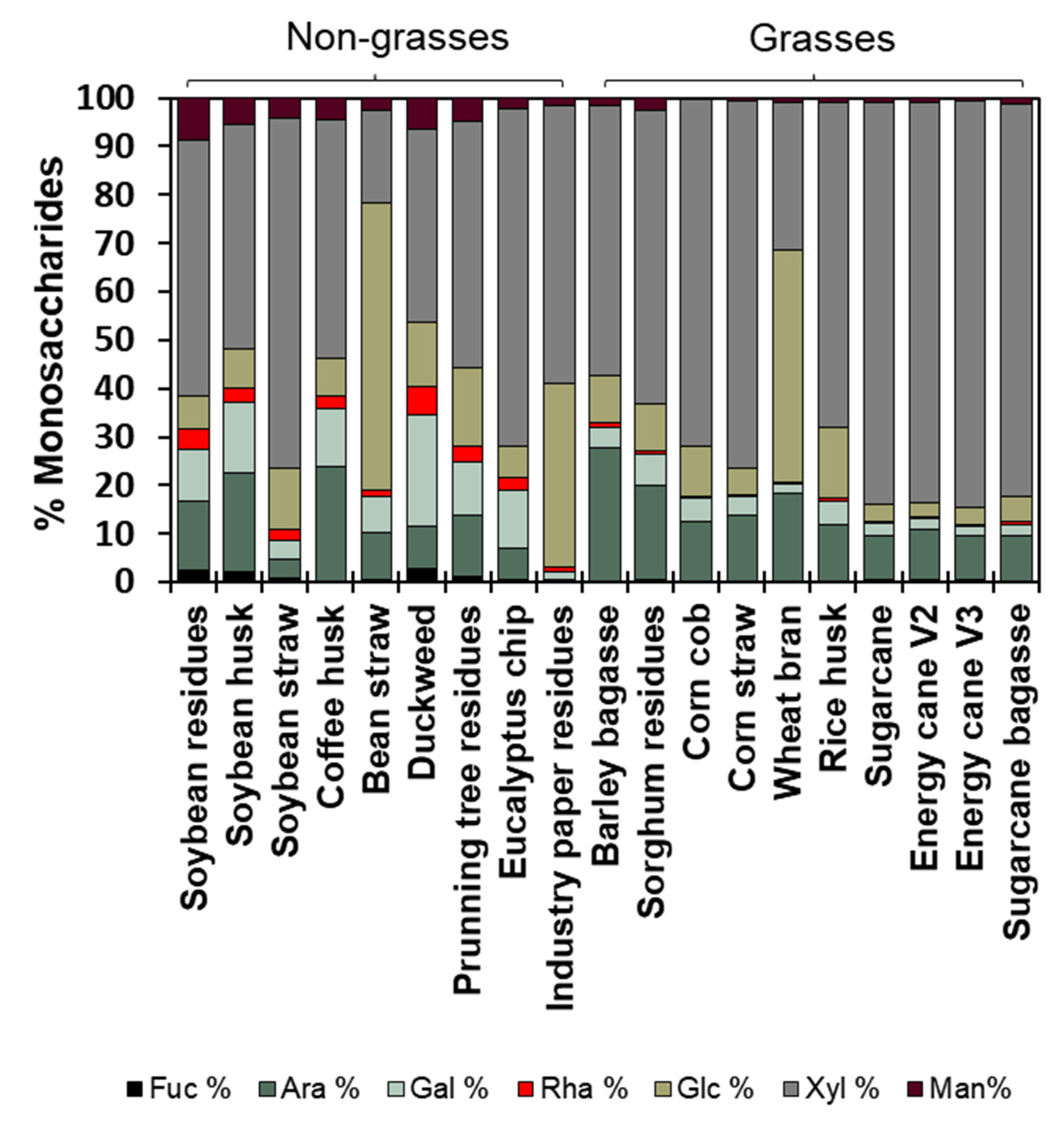

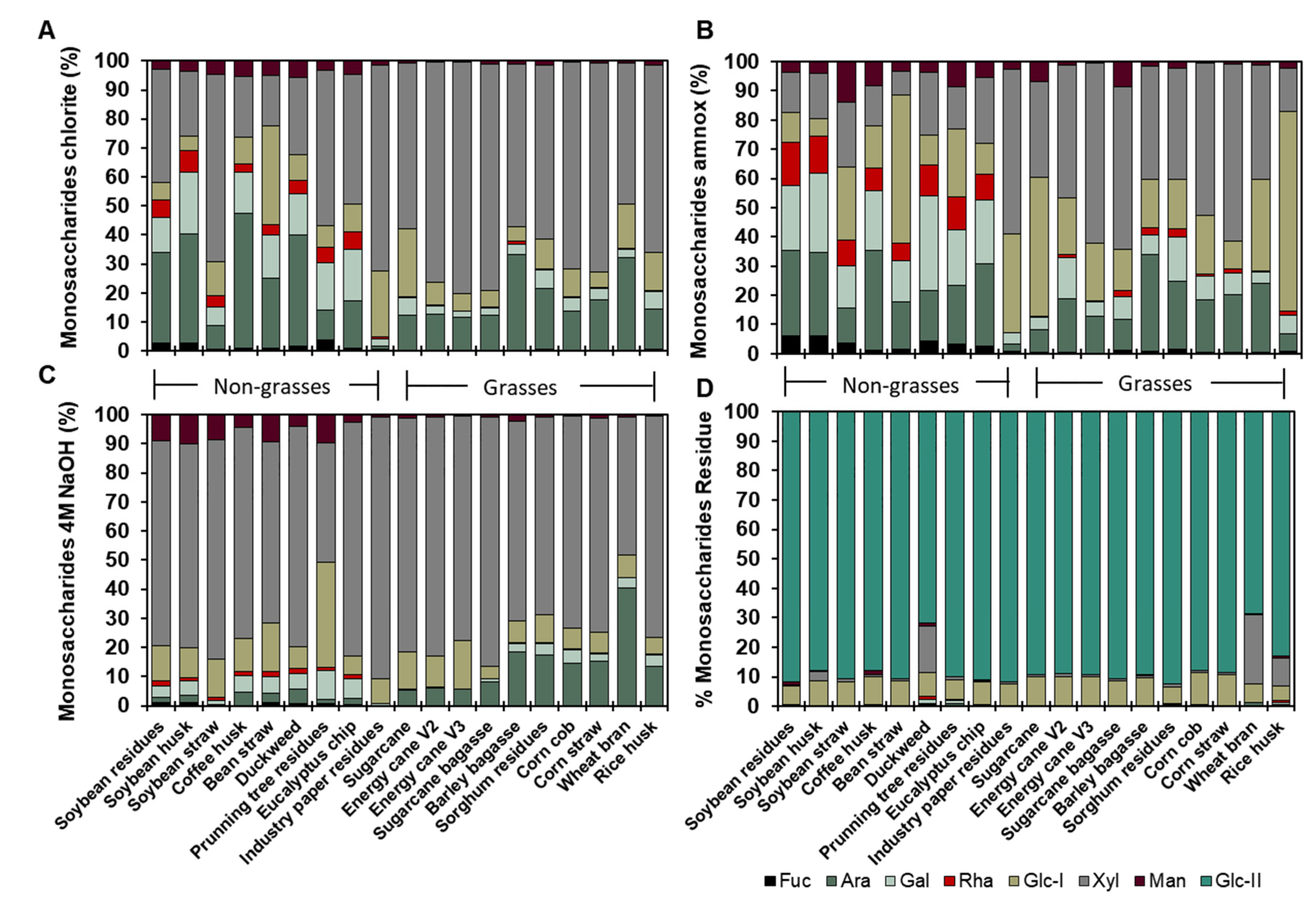

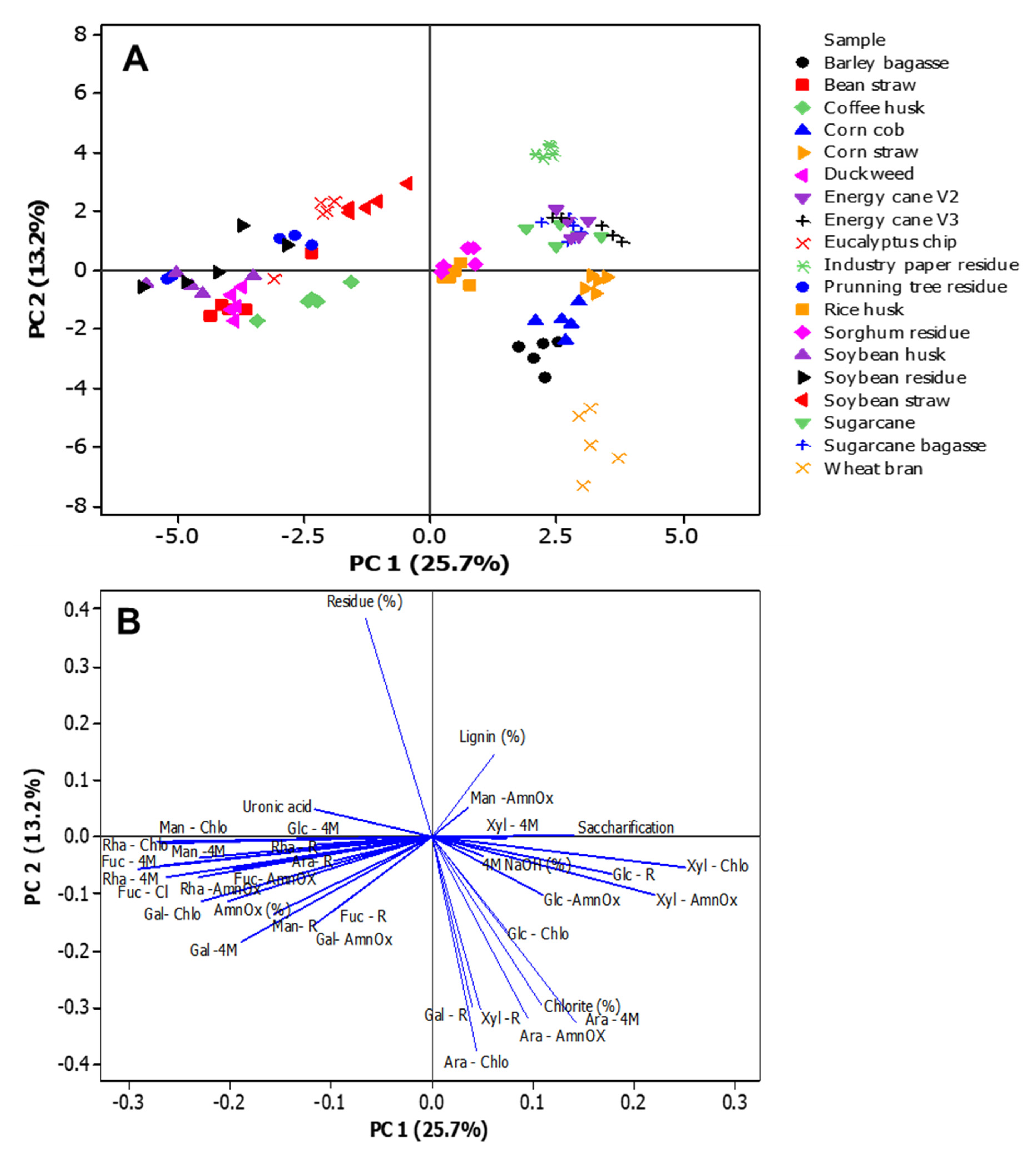

3.3. Fine Composition of the Cell Wall Agro-Wastes

4. Discussion

4.1. Agro-Waste Characterization and Its Potential

4.2. Cell Wall Components and Their Polysaccharides Applications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- HLPE High Level Panel of Experts. 2017. Nutrition and Food Systems. Committee o World Food Security (CFS) 2017, 44, 150.

- de Coninck, H.; Revi, A.; Babiker, M.; Bertoldi, P.; Buckeridge, M.; Cartwright, A.; Dong, W.; Ford, J.; Fuss, S.; Hourcade, J.C.; et al. Strenthening and Implementing the Global Response. In Global warming of 1.5°C: Summary for policy makers; IPCC - The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018; pp. 313–443.

- Mishra, A.; Kumar, M.; Medhi, K. Biomass Energy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Sustainable Bioresources for the Emerging Bioeconomy; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 399–427 ISBN 9780444643094.

- Martinez-Burgos, W.J.; Bittencourt Sydney, E.; Bianchi Pedroni Medeiros, A.; Magalhães, A.I.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Karp, S.G.; Porto de Souza Vandenberghe, L.; Junior Letti, L.A.; Thomaz Soccol, V.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; et al. Agro-Industrial Wastewater in a Circular Economy: Characteristics, Impacts and Applications for Bioenergy and Biochemicals. Bioresour Technol 2021, 341. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.D.; de Medeiros, G.A.; Paes, M.X.; de Oliveira, B.O.S.; Antunes, M.L.P.; de Souza, R.G.; Ferraz, J.L.; Bortoleto, A.P.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Circular Economy and Solid Waste Management: Challenges and Opportunities in Brazil. Circular Economy and Sustainability 2021, 1, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.-H.N.; Bertassini, A.C.; Mendes, J.A.J.; Gerolamo, M.C. The ‘3CE2CE’ Framework—Change Management Towards a Circular Economy: Opportunities for Agribusiness. Circular Economy and Sustainability 2021, 1, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbančič, J.; Lunn, J.E.; Stitt, M.; Persson, S. Carbon Supply and the Regulation of Cell Wall Synthesis. Mol Plant 2017, 11, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpita, N.C.; Gibeaut, D.M. Structural Models of Primary Cell Walls in Flowering Plants: Consistency of Molecular Structure with the Physical Properties of the Walls during Growth. The Plant Journal 1993, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.B.; Ionashiro, M.; Carrara, T.B.; Crivellari, A.C.; Tiné, M.A.S.S.; Prado, J.; Carpita, N.C.; Buckeridge, M.S. Cell Wall Polysaccharides from Fern Leaves: Evidence for a Mannan-Rich Type III Cell Wall in Adiantum Raddianum. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, M.C.; Carpita, N.C. Designing the Deconstruction of Plant Cell Walls. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2008, 11, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.P.; Leite, D.C.C.; Pattathil, S.; Hahn, M.G.; Buckeridge, M.S. Composition and Structure of Sugarcane Cell Wall Polysaccharides: Implications for Second-Generation Bioethanol Production. Bioenergy Res 2013, 6, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Bosneaga, E.; Auer, M. Plant Cell Walls throughout Evolution: Towards a Molecular Understanding of Their Design Principles. J Exp Bot 2009, 60, 3615–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.K.; Saini, R.; Tewari, L. Lignocellulosic Agriculture Wastes as Biomass Feedstocks for Second-Generation Bioethanol Production: Concepts and Recent Developments. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Venkatkarthick, R.; Jayashree, S.; Chuetor, S.; Dharmaraj, S.; Kumar, G.; Chen, W.H.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Recent Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuels and Value-Added Bioproducts - A Critical Review. Bioresour Technol 2022, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, N.; Lewandowski, I.; Zibek, S.; Weidtmann, A. Integrated Lignocellulosic Value Chains in a Growing Bioeconomy: Status Quo and Perspectives. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpit Singh, T.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, M.; Dutt Sharma, G.; Kumar Passari, A.; Bhasin, S. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Residues for Production of Commercial Biorefinery Products. Fuel 2022, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarino, I.; Araújo, P.; Domingues, A.P.; Mazzafera, P. An Overview of Lignin Metabolism and Its Effect on Biomass Recalcitrance. Brazilian Journal of Botany 2012, 35, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2974 Standard Test Methods for Determining the Water (Moisture) Content, Ash Content, and Organic Material of Peat and Other Organic Soils; Philadelphia, 1987.

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis and Torrefaction: Practical Design and Theory. Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis and Torrefaction: Practical Design and Theory 2013, 1–530. [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, R.; Vanholme, R.; Storme, V.; Mortimer, J.C.; Dupree, P.; Boerjan, W. Lignin Biosynthesis Perturbations Affect Secondary Cell Wall Composition and Saccharification Yield in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Biotechnol Biofuels 2013, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, R.S.; Kerley, M.S. Use of Lignin Extracted from Different Plant Sources as Standards in the Spectrophotometric Acetyl Bromide Lignin Method. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 3505–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, R.S.; Kerley, M.S.; Ramos, M.H.; Porter, J.H.; Kallenbach, R.L. Comparison of Acetyl Bromide Lignin with Acid Detergent Lignin and Klason Lignin and Correlation with in Vitro Forage Degradability. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2015, 201, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.C.; Chandra, R.; Berleth, T.; Beatson, R.P. Rapid, Microscale, Acetyl Bromide-Based Method for High-Throughput Determination of Lignin Content in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 6825–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, N.C. Fractionation of Hemicelluloses from Maize Cell Walls with Increasing Concentrations of Alkali. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkova, T.A.; Wyatt, S.E.; Salnikov, V. V; Gibeaut, D.M.; Lozovaya, V. V; Carpita, N.C.; Ibragimov, R. Cell-Wall Polysaccharides of Developing Flax Plants ’. 1996, 721–729. [CrossRef]

- Filisetti-Cozzi, T.M.C.C.; Carpita, N.C. Measurement of Uronic Acids without Interference from Neutral Sugars. Anal Biochem 1991, 197, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.D.; Whitehead, C.; Barakate, A.; Halpin, C.; McQueen-Mason, S.J. Automated Saccharification Assay for Determination of Digestibility in Plant Materials. Biotechnol Biofuels 2010, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, M.C.; Roberts, K. Changes in Cell Wall Architecture during Cell Elongation. J Exp Bot 1994, 45, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.Y.; Chang, C.K.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Chia, S.R.; Lim, J.W.; Chang, J.S.; Show, P.L. Waste Biorefinery towards a Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy: A Solution to Global Issues. Biotechnol Biofuels 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Karpichev, Y.; Pandey, A.; Chandra Kuhad, R.; Bhat, R.; Punia, R.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Gupta, V.K. Advancement in Valorization Technologies to Improve Utilization of Bio-Based Waste in Bioeconomy Context. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh Negi, Y.; Choudhary, V.; Kant Bhardwaj, N. Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced by Acid-Hydrolysis from Sugarcane Bagasse as Agro-Waste. Journal of Materials Physics and Chemistry 2014, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávaro, S.L.; Lopes, M.S.; Vieira de Carvalho Neto, A.G.; Rogério de Santana, R.; Radovanovic, E. Chemical, Morphological, and Mechanical Analysis of Rice Husk/Post-Consumer Polyethylene Composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2010, 41, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.I.H.; Yeasmin, M.S.; Rahman, M.S. Preparation of Food Grade Carboxymethyl Cellulose from Corn Husk Agrowaste. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 79, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, M.; Asghar, A.; Ramzan, N.; Aslam, U.; Bello, M.M. Impacts of Non-Oxidative Torrefaction Conditions on the Fuel Properties of Indigenous Biomass (Bagasse). Waste Manag Res 2020, 38, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.P.; Ferreira, A.N.; de Albuquerque, F.S.; de Almeida Barros, A.C.; da Luz, J.M.R.; Gomes, F.S.; Pereira, H.J.V. Box–Behnken Experimental Design for the Optimization of Enzymatic Saccharification of Wheat Bran. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2022, 12, 5597–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger Filho, G.C.; Costa, F.; Torraga Maria, G.F.; Bufacchi, P.; Trubachev, S.; Shundrina, I.; Korobeinichev, O. Kinetic Parameters and Heat of Reaction for Forest Fuels Based on Genetic Algorithm Optimization. Thermochim Acta 2022, 713, 179228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Maris, A.J.A.A.; Abbott, D.A.; Bellissimi, E.; van den Brink, J.; Kuyper, M.; Luttik, M.A.H.H.; Wisselink, H.W.; Scheffers, W.A.; van Dijken, J.P.; Pronk, J.T. Alcoholic Fermentation of Carbon Sources in Biomass Hydrolysates by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Current Status. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology 2006, 90, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysés, D.N.; Reis, V.C.B.; de Almeida, J.R.M.; de Moraes, L.M.P.; Torres, F.A.G. Xylose Fermentation by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Challenges and Prospects. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, J.T.; Soares, P.O.; Romaní, A.; Thevelein, J.M.; Domingues, L. Xylose Fermentation Efficiency of Industrial Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast with Separate or Combined Xylose Reductase/Xylitol Dehydrogenase and Xylose Isomerase Pathways. Biotechnol Biofuels 2019, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, I.M.; Brown, R.M. Cellulose Biosynthesis: Current Views and Evolving Concepts. Ann Bot 2005, 96, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhang, N.; Phillips, G.C.; Xu, J. Growing Lemna Minor in Agricultural Wastewater and Converting the Duckweed Biomass to Ethanol. Bioresour Technol 2012, 124, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Willför, S.; Xu, C. A Review of Bioactive Plant Polysaccharides: Biological Activities, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2015, 5, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palantöken, S.; Bethke, K.; Zivanovic, V.; Kalinka, G.; Kneipp, J.; Rademann, K. Cellulose Hydrogels Physically Crosslinked by Glycine: Synthesis, Characterization, Thermal and Mechanical Properties. J Appl Polym Sci 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddiqi, H.; Oliaei, E.; Honarkar, H.; Jin, J.; Geonzon, L.C.; Bacabac, R.G.; Klein-Nulend, J. Cellulose and Its Derivatives: Towards Biomedical Applications. Cellulose 2021, 28, 1893–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L. Lignins: Biosynthesis and Biological Functions in Plants. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Kim, T.H.; Liu, K.; Ma, M.G.; Choi, S.E.; Si, C. Multifunctional Lignin-Based Composite Materials for Emerging Applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, T.; Fatehi, P. Production and Application of Lignosulfonates and Sulfonated Lignin. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1861–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, F.; Bischof, S.; Mayr, S.; Gritsch, S.; Jimenez Bartolome, M.; Schwaiger, N.; Guebitz, G.M.; Weiss, R. The Biomodified Lignin Platform: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutyser, W.; Renders, T.; Van Den Bossche, G.; Van Den Bosch, S.; Koelewijn, S.-F.; Ennaert, T.; Sels, B.F. Catalysis in Lignocellulosic Biorefineries: The Case of Lignin Conversion. In Nanotechnology catalysis; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; pp. 587–584. [Google Scholar]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquena-Moret, J. A Review of Xyloglucan: Self-Aggregation, Hydrogel Formation, Mucoadhesion and Uses in Medical Devices. Macromol 2022, 2, 562–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Malhotra, A.V. Tamarind Xyloglucan: A Polysaccharide with Versatile Application Potential. J Mater Chem 2009, 19, 8528–8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Jia, X.; Feng, L.; Yadav, M.; Li, X.; Yin, L. Rheological and Emulsifying Properties of Arabinoxylans from Various Cereal Brans. J Cereal Sci 2019, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Estrada, R.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; De Jesús Ascencio Valle, F.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Brown-Bojorquez, F.; Rascón-Chu, A. Covalently Cross-Linked Arabinoxylans Films for Debaryomyces Hansenii Entrapment. Molecules 2015, Vol. 20, Pages 11373-11386 2015, 20, 11373–11386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.J.; Qiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ou, X.; Wang, X. Isolation, Structural, Functional, and Bioactive Properties of Cereal Arabinoxylan─A Critical Review. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 15437–15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, G.; Arya, S.K. Mannans: An Overview of Properties and Application in Food Products. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 119, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.-D.; Kim, D.; Paek, S.-H.; Oh, S.-E. Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides as Potential Resources for the Development of Novel Prebiotics. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2012, 20, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Gupta, O.P.; Sagwal, V.; Kumar, A.; Patwa, N.; Mohan, N.; Ankush; Kumar, D.; Vir, O.; Singh, J.; et al. Beta-Glucan as a Soluble Dietary Fiber Source: Origins, Biosynthesis, Extraction, Purification, Structural Characteristics, Bioavailability, Biofunctional Attributes, Industrial Utilization, and Global Trade. Nutrients 2024, 16, 900. [CrossRef]

- Mohnen, D. Pectin Structure and Biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2008, 11, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E.; Hopf, H. Branched-Chain Sugars and Sugar Alcohols. Methods in Plant Biochemistry 1990, 2, 235–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckey-Kaltenbach, H.; Heller, W.; Sonnenbichler, J.; Zetl, I.; Schäfer, W.; Ernst, D.; Sandermann, H. Oxidative Stress and Plant Secondary Metabolism: 6″-O-Malonylapiin in Parsley. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mølhøj, M.; Verma, R.; Reiter, W.D. The Biostnthesis of the Branched-Chain Sugar D-Apiose in Plants: Functional Cloning and Characterization of a UDP-D-Apiose/UDP-D-Xylose Synthase from Arabidopsis. Plant Journal 2003, 35, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pičmanová, M.; Møller, B.L. Apiose: One of Nature’s Witty Games. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanutto, F.V.; Boldrin, P.K.; Varanda, E.A.; De Souza, S.F.; Sano, P.T.; Vilegas, W.; Dos Santos, L.C. Characterization of Flavonoids and Naphthopyranones in Methanol Extracts of Paepalanthus Chiquitensis Herzog by HPLC-ESI-IT-MSn and Their Mutagenic Activity. Molecules 2013, Vol. 18, Pages 244-262 2012, 18, 244–262. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M.P.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; Sousa, R.C.S. Structure and Applications of Pectin in Food, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agro-waste | Species | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Soybean residues | Glycine max var IAC Foscarin 31 | Instituto Agrônomico de Campinas |

| Soybean husk | Glycine max | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Soybean straw | Glycine max | Maringá, PR |

| Coffee husk | Coffea sp. | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Bean straw | Phaseolus vulgaris | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Duckweed | Lemna minor 8627 | Rutgers Duckweed Stock Cooperative |

| Prunning tree residues | - | University of São Paulo |

| Eucalyptus chip | Eucalyptus sp. | Suzano papel e celulose |

| Industry paper residues | - | Suzano papel e celulose |

| Barley bagasse | Hordeum vulgare | Brewery Colorado, Ribeirão Preto -SP |

| Sorghum residues | Sorghum bicolor | Embrapa |

| Corn cob | Zea mays | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Corn straw | Zea mays | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Wheat bran | Triticum sp. | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Rice husk | Oryza sativa | Ribeirão Preto-SP |

| Sugarcane | Saccharum sp 80-3280 | Piracicaba- SP |

| Energy cane V2 | Saccharum ssp. | Piracicaba- SP |

| Energy cane V3 | Saccharum ssp. | Piracicaba- SP |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Saccharum spp. | Guarani - São Paulo-SP |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).