Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis Methods

2.2. Characterization Techniques

2.3. Catalytic Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Supports and the Ni Catalysts

3.2. Catalytic Activity

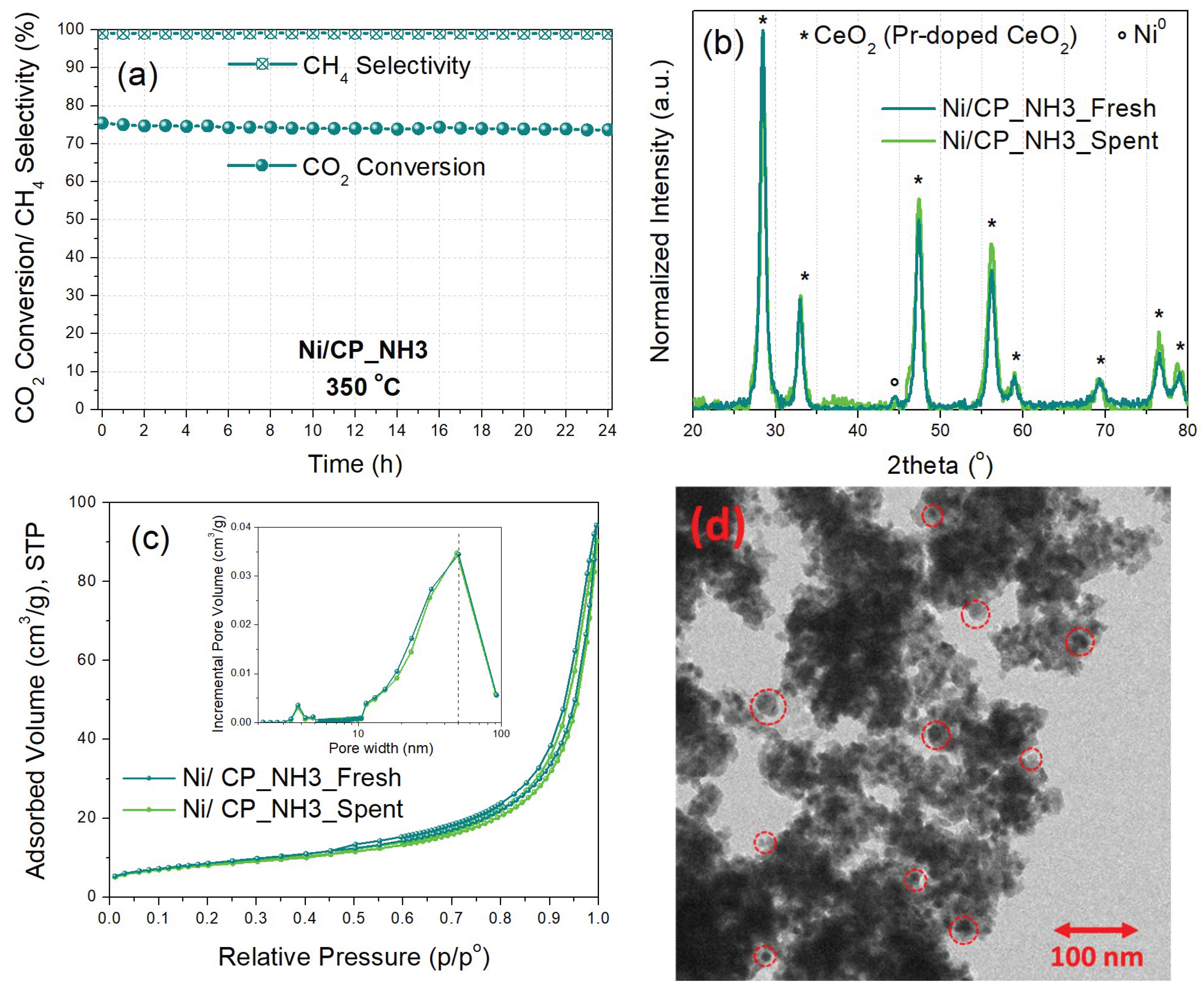

3.3. Catalytic Stability and Spent Catalyst Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Caldeira, K.; Shearer, C.; Hong, C.; Qin, Y.; Davis, S.J. Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5 °C climate target. Nature 2019, 572, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, D.; Simshauser, P.; Binh, D. Greenhouse gas emissions vs CO2 emissions : Comparative analysis of a global carbon tax. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Jia, C.; Li, Z.; Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. Recent Advances and Future Perspectives in Carbon Capture, Transportation, Utilization, and Storage (CCTUS) Technologies : A Comprehensive Review. Fuel 2023, 351, 128913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziejarski, B.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Andersson, K. Current status of carbon capture, utilization, and storage technologies in the global economy: A survey of technical assessment. Fuel 2023, 342, 127776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latsiou, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Frontistis, Z.; Bansode, A.; Goula, M.A. CO2 hydrogenation for the production of higher alcohols: Trends in catalyst developments, challenges and opportunities. Catal. Today 2023, 420, 114179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Dincer, I. A comprehensive review on power-to-gas with hydrogen options for cleaner applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 31511–31522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.M.; Hossain, S.; Nisfindy, O.B.; Azad, A.T.; Dawood, M.; Azad, A.K. Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and key challenges with applications: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 602–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Liang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, J. A short overview of Power-to-Methane : Coupling preparation of feed gas with CO2 methanation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 274, 118692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, M.; Naz, S.; Ramis, G.; Rossetti, I. Advancements in CO2 methanation: A comprehensive review of catalysis, reactor design and process optimization. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 201, 457–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Yentekakis, I.V.; Goula, M.A. Bimetallic Ni-based catalysts for CO2 methanation: A review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, J.; Pati, S.; Hongmanorom, P.; Tianxi, Z.; Junmei, C.; Kawi, S. A review of recent catalyst advances in CO2 methanation processes. Catal. Today 2020, 356, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Xu, L.; Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Wen, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, C.E.; Yang, B.; Miao, Z.; Hu, X.; et al. Recent Progresses in Constructing the Highly Efficient Ni Based Catalysts With Advanced Low-Temperature Activity Toward CO2 Methanation. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S. Comprehensive review of nickel-based catalysts advancements for CO2 methanation. 2025, 207, 114926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Tanimu, G.; Ahmed, S.; Aniz, C.U.; Alasiri, H.; Alhooshani, K. A review of the indispensable role of oxygen vacancies for enhanced CO2 methanation activity over CeO2-based catalysts: Uncovering, influencing, and tuning strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 24663–24696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Arenas, A.; Quindimil, A.; Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Bailón-García, E.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; De-La-Torre, U.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R.; Bueno-López, A. Isotopic and in situ DRIFTS study of the CO2 methanation mechanism using Ni/CeO2 and Ni/Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 265, 118538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Gu, F.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, T.; Xu, G.; Zhong, Z.; Su, F. Enhancing the low-temperature CO2 methanation over Ni/La-CeO2 catalyst: The effects of surface oxygen vacancy and basic site on the catalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 312, 121385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Park, Y.S.; Diercks, D.; Kazempoor, P.; Duan, C. Enhanced CO2 Methanation Activity of Sm0.25Ce0.75O2-δ-Ni by Modulating the Chelating Agents-to-Metal Cation Ratio and Tuning Metal-Support Interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 13295–13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakavelas, G.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; AlKhoori, S.; AlKhoori, A.A.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; Yentekakis, I. V.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Goula, M.A. Highly selective and stable nickel catalysts supported on ceria promoted with Sm2O3, Pr2O3 and MgO for the CO2 methanation reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 282, 119562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakavelas, G.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; AlKhoori, A.; AlKhoori, S.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; Yentekakis, I. V.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Goula, M.A. Highly selective and stable Ni/La-M (M=Sm, Pr, and Mg)-CeO2 catalysts for CO2 methanation. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 51, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; AlKhoori, A.; Gaber, S.; Stolojan, V.; Sebastian, V.; van der Linden, B.; Bansode, A.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; et al. Optimizing the oxide support composition in Pr-doped CeO2 towards highly active and selective Ni-based CO2 methanation catalysts. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 71, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, N.; Mori, K.; Asahara, K.; Shibata, S.; Jida, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Yamashita, H. How the Morphology of NiOx-Decorated CeO2 Nanostructures Affects Catalytic Properties in CO2 Methanation. Langmuir 2021, 37, 5376–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Chan, Y.M.; Yu, Y.; Kawi, S. Morphology dependence of catalytic properties of Ni/CeO2 for CO2 methanation: A kinetic and mechanism study. Catal. Today 2020, 347, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Chu, M.; Yue, J.; Cui, Y.; Xu, G. Enhanced Low-Temperature Activity of CO2 Methanation Over Ni/CeO2 Catalyst. Catal. Letters 2021, 152, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomjaree, T.; Sintuya, P.; Srifa, A.; Koo-amornpattana, W.; Kiatphuengporn, S.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Sudoh, M.; Watanabe, R.; Fukuhara, C.; Ratchahat, S. Catalytic performance of Ni catalysts supported on CeO2 with different morphologies for low-temperature CO2 methanation. Catal. Today 2021, 375, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Xu, C.; Wen, X.; Xu, L.; Cui, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, C. e.; Qiu, J.; Cheng, G.; Chen, M. CO2 methanation over the Ni-based catalysts supported on nano-CeO2 with varied morphologies. Fuel 2023, 331, 125755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, Z.; Li, M. Tailoring metal-support interactions via tuning CeO2 particle size for enhancing CO2 methanation activity over Ni/CeO2 catalysts. Fuel 2023, 333, 126369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Long, B.; Anh, P.; Thuy, T.; Nguyen, V.; Anh, C. Nickel/ceria nanorod catalysts for the synthesis of substitute natural gas from CO2 : Effect of active phase loading and synthesis condition. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2024, 9, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chang, K.; Yang, M.; Yan, X.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Facilitating CO2 methanation over oxygen vacancy-rich Ni/CeO2 : Insights into the synergistic effect between oxygen vacancy and metal-support interaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, I. Zr promotion effect in CO2 methanation over ceria-supported nickel catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde-Santiago, V.; Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Quindimil, A.; De-La-Torre, U.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R.; Bueno-López, A. Ni/LnOx Catalysts (Ln=La, Ce or Pr) for CO2 Methanation. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Harkou, E.; Hafeez, S.; Manos, G.; Constantinou, A.; Hussien, A.G.S.; Dabbawala, A.A.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; et al. Enhancing CO2 methanation over Ni catalysts supported on sol-gel derived Pr2O3-CeO2: An experimental and theoretical investigation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 318, 121836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yuan, X.; Li, B.; Wang, X. Impact of pore structure on hydroxyapatite supported nickel catalysts (Ni/HAP) for dry reforming of methane. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 202, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongmanorom, P.; Ashok, J.; Chirawatkul, P.; Kawi, S. Interfacial synergistic catalysis over Ni nanoparticles encapsulated in mesoporous ceria for CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 297, 120454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Arenas, A.; Quindimil, A.; Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Bailón-García, E.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; De-La-Torre, U.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R.; Bueno-López, A. Design of active sites in Ni/CeO2 catalysts for the methanation of CO2: tailoring the Ni-CeO2 contact. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 19, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Hussien, A.G.S.; Sebastian, V.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Goula, M.A. Integrating capture and methanation of CO2 using physical mixtures of Na-Al2O3 and mono-/ bimetallic (Ru)Ni/Pr-CeO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Italiano, C.; Ferrante, G.D.; Pino, L.; Vita, A.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; Sharan, A.; et al. Ni-noble metal bimetallic catalysts for improved low-temperature CO2 methanation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 646, 158945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychronopoulou, K.; Alkhoori, S.; Albedwawi, S.; Alareeqi, S.; Hussien, A.G.S.; Vasiliades, M.A.; Efstathiou, A.M.; Petallidou, K.C.; Singh, N.; Anjum, D.H.; et al. Decoupling the Chemical and Mechanical Strain Effect on Steering the CO2 Activation over CeO2-Based Oxides: An Experimental and DFT Approach. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 33094–33119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, X.; Xu, J.; Fang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, X. The distributions of alkaline earth metal oxides and their promotional effects on Ni/CeO2 for CO2 methanation. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Gao, G.; Dong, D.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, X. Methanation of CO2 over nickel catalysts: Impacts of acidic/basic sites on formation of the reaction intermediates. Fuel 2020, 262, 116521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, S.; Davó-Quiñonero, A.; Bailón-García, E.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Villar-Garcia, I.J.; Dieste, V.P.; Calvo, J.A.O.; Velasco, J.R.G.; Bueno-López, A. Monitoring by in situ NAP-XPS of active sites for CO2 methanation on a Ni/CeO2 catalyst. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 60, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charisiou, N.D.; Siakavelas, G.; Tzounis, L.; Dou, B.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Goula, M.A. Ni/Y2O3–ZrO2 catalyst for hydrogen production through the glycerol steam reforming reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 10442–10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.M.; Chaffee, A.L. Correlations between Oxygen Uptake and Vacancy Concentration in Pr-Doped CeO2. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Feng, J.; Ju, X.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Chen, P. Ru Nanoparticles on Pr2O3 as an Efficient Catalyst for Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition. Catal. Letters 2022, 152, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, H.; Frolova, Y. V.; Kaichev, V. V.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Alikina, G.M.; Lukashevich, A.I.; Zaikovskii, V.I.; Moroz, E.M.; Trukhan, S.N.; Ivanov, V.P.; et al. Electronic and chemical properties of nanostructured cerium dioxide doped with praseodymium. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 5728–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, L.; Li, D.; Yuan, J.; Bao, G. Enhanced low-temperature activity of CO2 methanation over Ni/CeO2 catalyst : Influence of preparation methods. Appl. Catal. O Open 2024, 192, 206956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Tang, R.; Liu, X.; Gong, L.; Li, Z. Modulating CO2 methanation activity on Ni/CeO2 catalysts by tuning ceria facet-induced metal-support interaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvoutis, G.; Lykaki, M.; Stefa, S.; Binas, V.; Marnellos, G.E.; Konsolakis, M. Deciphering the role of Ni particle size and nickel-ceria interfacial perimeter in the low-temperature CO2 methanation reaction over remarkably active Ni/CeO2 nanorods. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 297, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisiou, N.D.; Yentekakis, I.V.; Goula, M.A. The role of alkali and alkaline earth metals in the CO2 methanation reaction and the combined capture and methanation of CO2. Catalysts 2020, 10, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.A.; Kim, T.W.; Lee, S.H.; Park, E.D. Effects of Na content in Na/Ni/SiO2 and Na/Ni/CeO2 catalysts for CO and CO2 methanation. Catal. Today 2018, 303, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Chen, T.C.; Wu, J.H.; Pao, C.W.; Chen, C.S. Influence of sodium-modified Ni/SiO2 catalysts on the tunable selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation: Effect of the CH4 selectivity, reaction pathway and mechanism on the catalytic reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 586, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierlein, D.; Häussermann, D.; Pfeifer, M.; Schwarz, T.; Stöwe, K.; Traa, Y.; Klemm, E. Is the CO2 methanation on highly loaded Ni-Al2O3 catalysts really structure-sensitive? Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 247, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qin, C.; Xu, Y.; Xu, D.; Bai, J.; Ma, G.; Ding, M. Ni nanoparticles dispersed on oxygen vacancies-rich CeO2 nanoplates for enhanced low-temperature CO2 methanation performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisetto, I.; Stendardo, S.; Senthil Kumar, S.M.; Selvakumar, K.; Kesavan, J.K.; Iucci, G.; Pasqual Laverdura, U.; Tuti, S. One-pot synthesis of Ni0.05Ce0.95O2−δ catalysts with nanocubes and nanorods morphology for CO2 methanation reaction and in operando DRIFT analysis of intermediate species. Processes 2021, 9, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Hao, Z.; Shen, J.; Chang, X.; Huang, S.; Li, M.; Ma, X. Enhancing the CO2 methanation activity of Ni/CeO2 via activation treatment-determined metal-support interaction. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 59, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst support | Precipitating agent | Hydrothermal treatment temperature |

|---|---|---|

| CP_NaOH | NaOH | R.T. 1 (Co-precipitation) |

| HT_NaOH_100 | NaOH | 100 oC |

| HT_NaOH_180 | NaOH | 180 oC |

| CP_NH3 | NH3/ (NH4)2CO3 | R.T. 1 (Co-precipitation) |

| HT_NH3_100 | NH3/ (NH4)2CO3 | 100 oC |

| HT_NH3_180 | NH3/ (NH4)2CO3 | 180 oC |

| Catalyst | (nm) | (nm) | SSA (m2/g) | (cm3/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/CP_NaOH | 22 (8) | 15 | 17 (91) | 0.22 (0.48) | 50 (21) |

| Ni/HT_NaOH_100 | 17 (10) | 8 | 13 (63) | 0.20 (0.22) | 61 (14) |

| Ni/HT_NaOH_180 | 20 (20) | 14 | 8 (10) | 0.09 (0.10) | 48 (38) |

| Ni/CP_NH3 | 11 (8) | 11 | 31 (46) | 0.14 (0.21) | 19 (18) |

| Ni/HT_NH3_100 | 9 (9) | 13 | 35 (61) | 0.08 (0.12) | 10 (8) |

| Ni/HT_NH3_180 | 10 (9) | 13 | 24 (58) | 0.12 (0.11) | 19 (7) |

| Catalyst | CO2 Conversion (%) | CH4 Selectivity (%) | CH4 Yield (%) | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/CP_NaOH | 65 (45) | 98 (96) | 64 (44) | 101 |

| Ni/HT_NaOH_100 | 66 (43) | 98 (96) | 64 (41) | 100 |

| Ni/HT_NaOH_180 | 60 (41) | 97 (95) | 58 (38) | 91 |

| Ni/CP_NH3 | 75 (65) | 99 (100) | 75 (65) | 106 |

| Ni/HT_NH3_100 | 73 (56) | 99 (99) | 72 (56) | 95 |

| Ni/HT_NH3_180 | 72 (59) | 99 (99) | 72 (59) | 104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).