Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. BIM Object Classification

2.2. Building Classification System

2.3. Automatic Classification by Machine Learning

3. Methodology

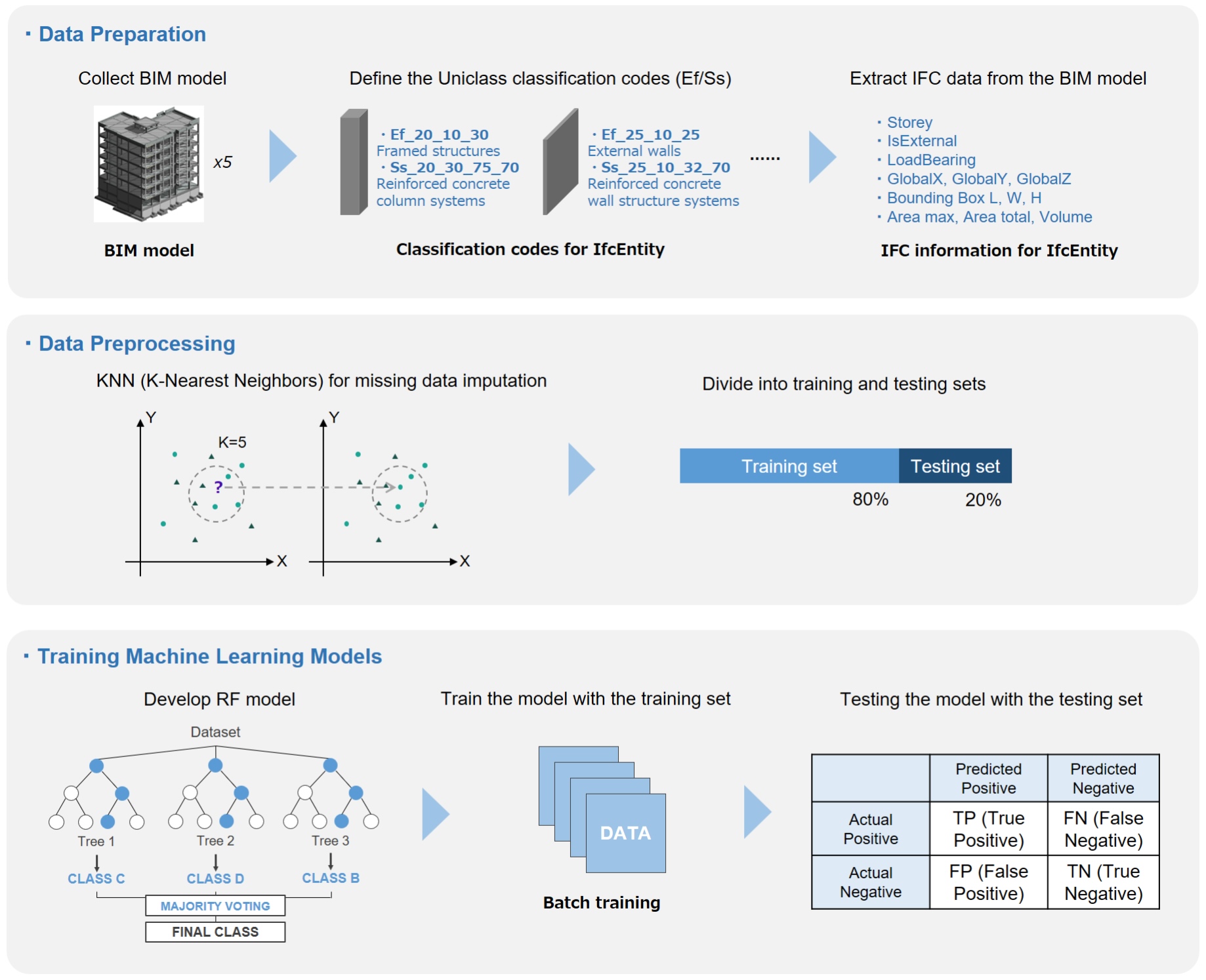

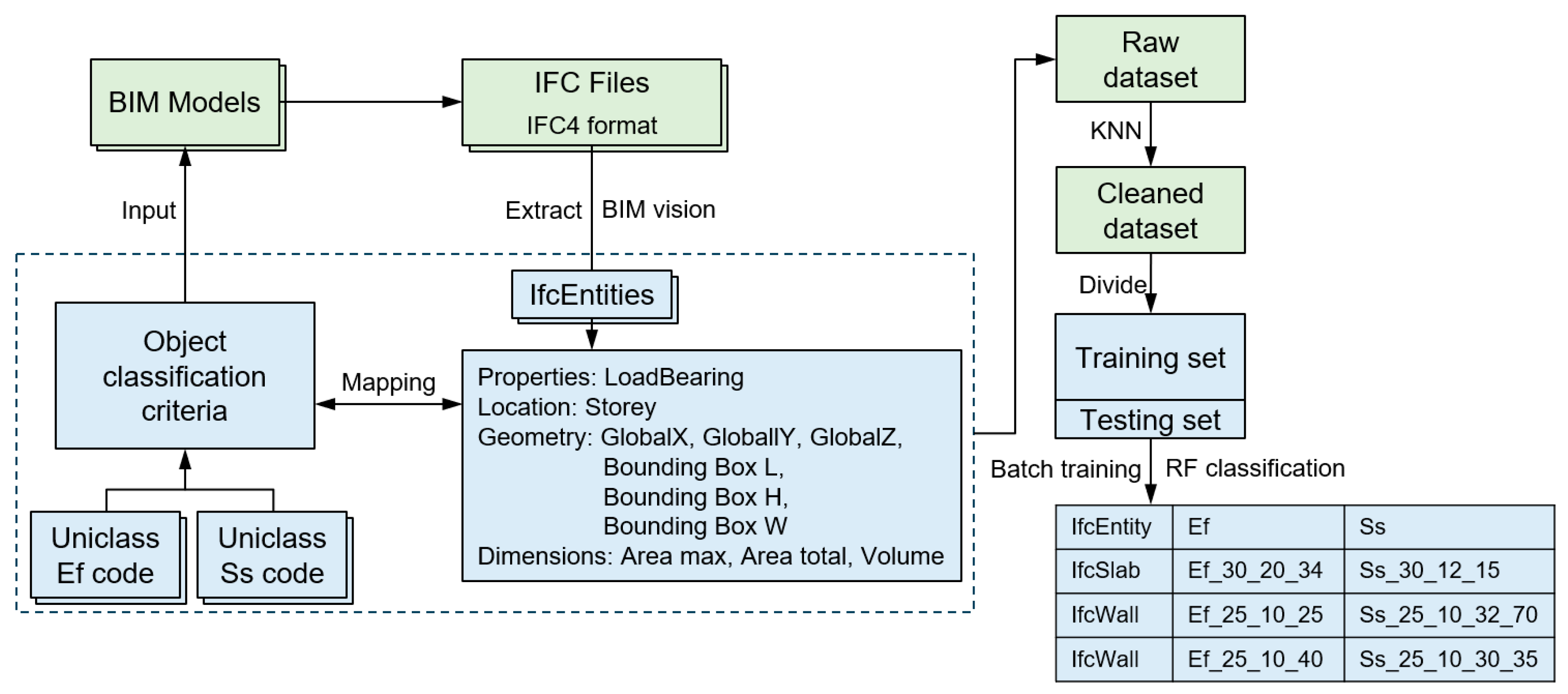

3.1. Research Process

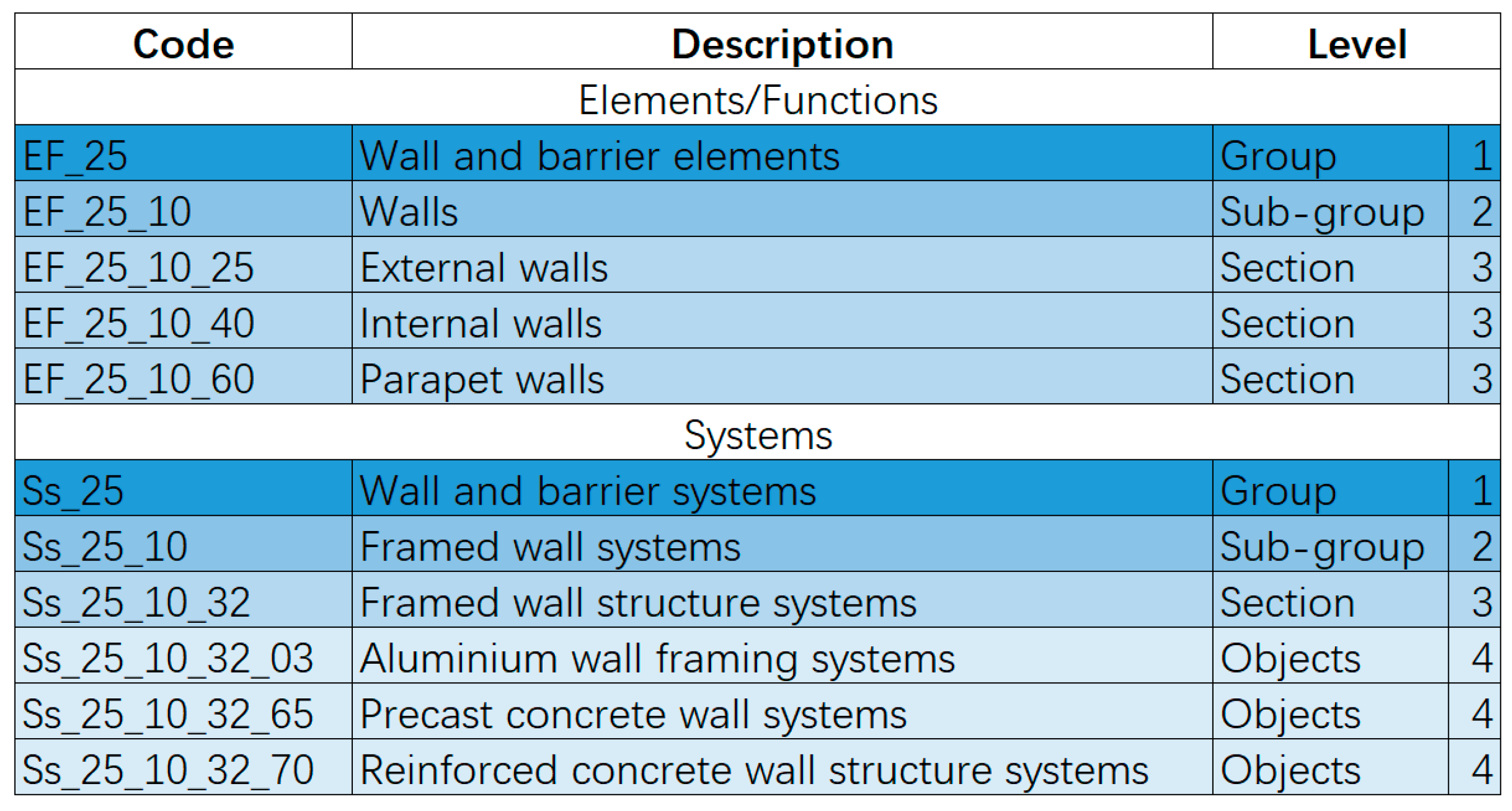

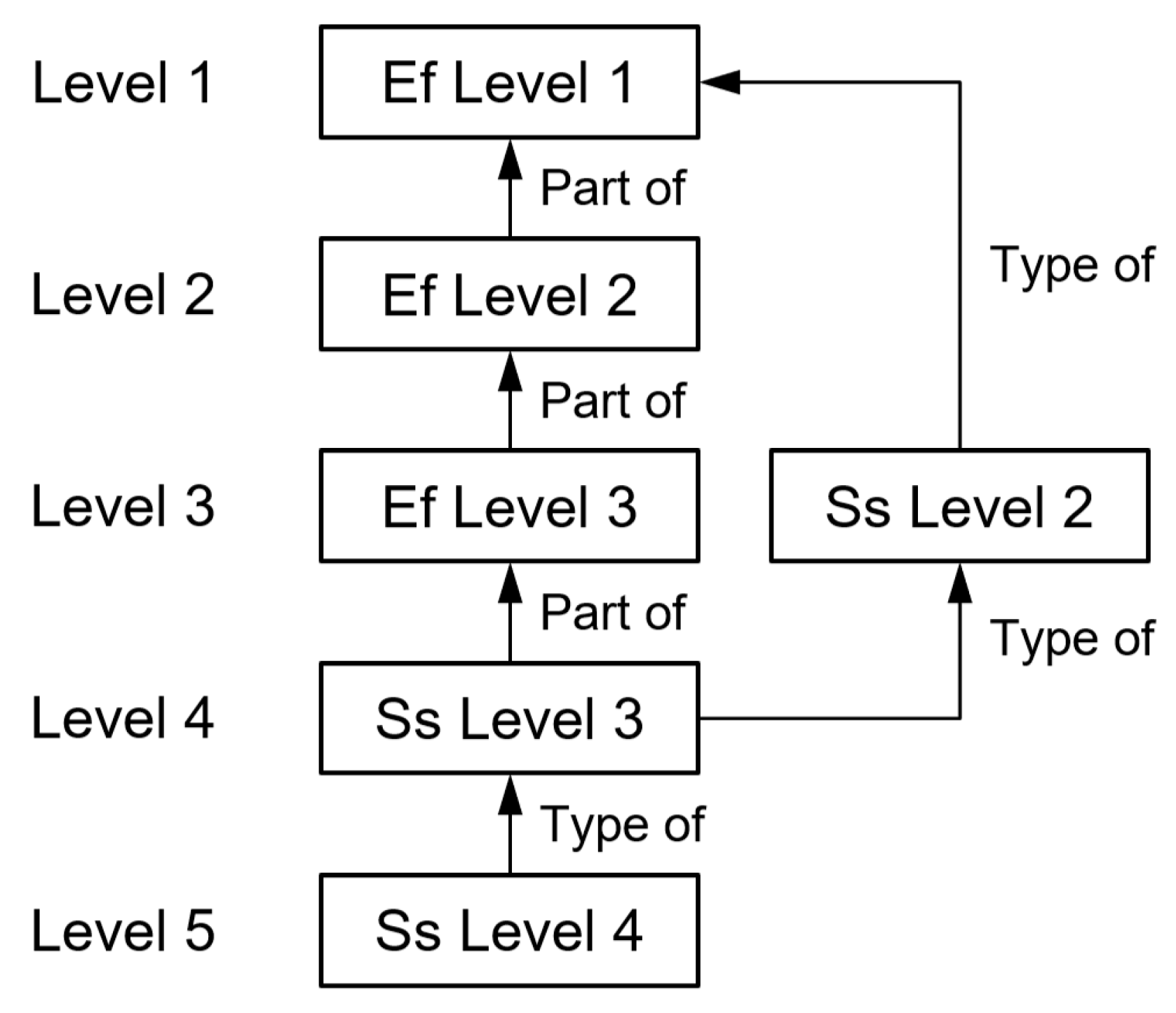

3.2. Uniclass Classification System

3.3. Data Acquisition and Feature Selection

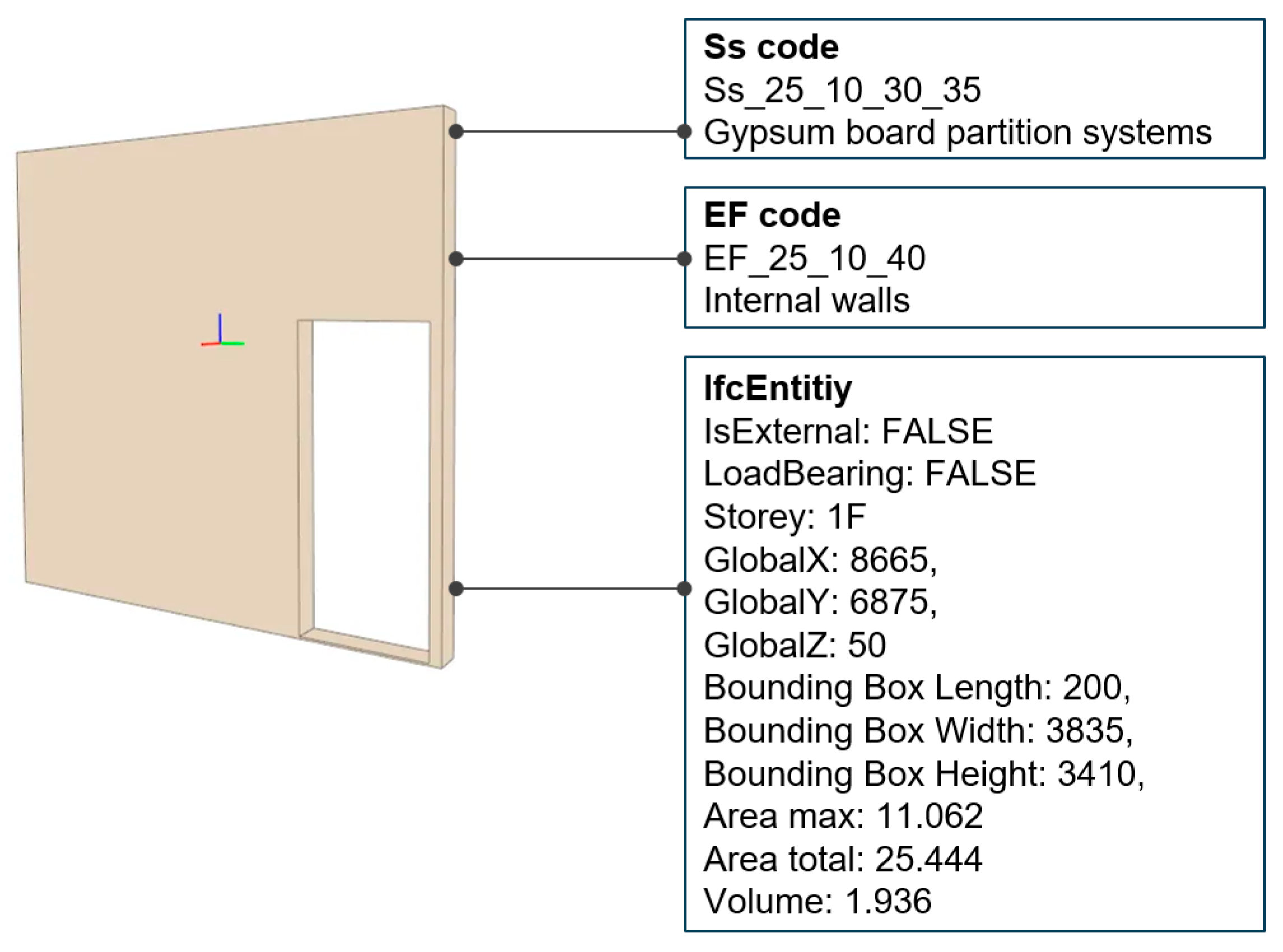

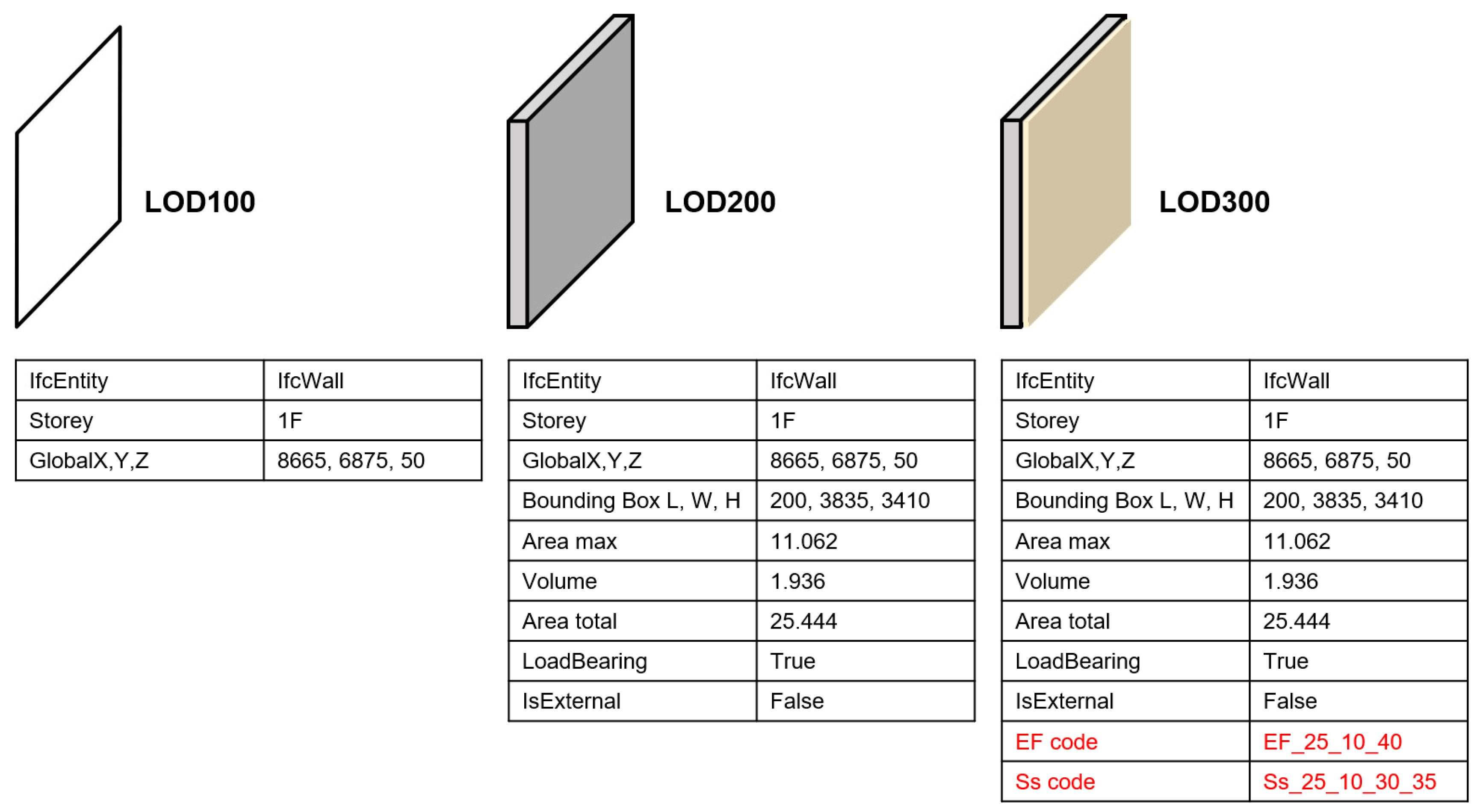

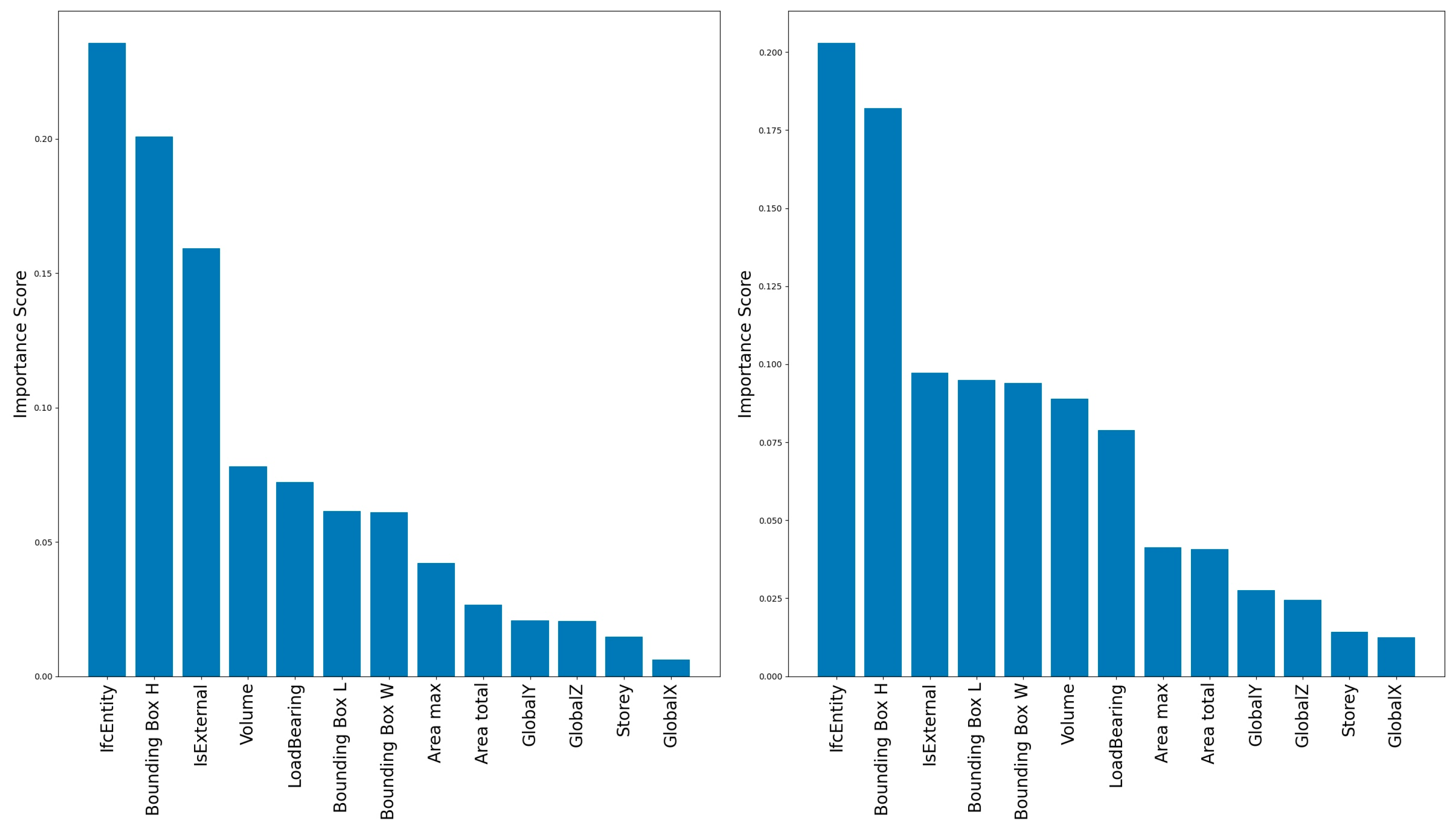

- Semantic attributes: including IfcEntity, Storey, LoadBearing, and IsExternal;

- Spatial features: including the global spatial coordinates within the model (GlobalX, GlobalY, GlobalZ) and the bounding box dimensions (length, width, and height);

- Dimensional information: including Area max, Area total, and Volume.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

- T: True (prediction is correct)

- F: False (prediction is incorrect)

- P: Positive (belongs to the target class)

- N: Negative (does not belong to the target class)

4. Experiments and Results

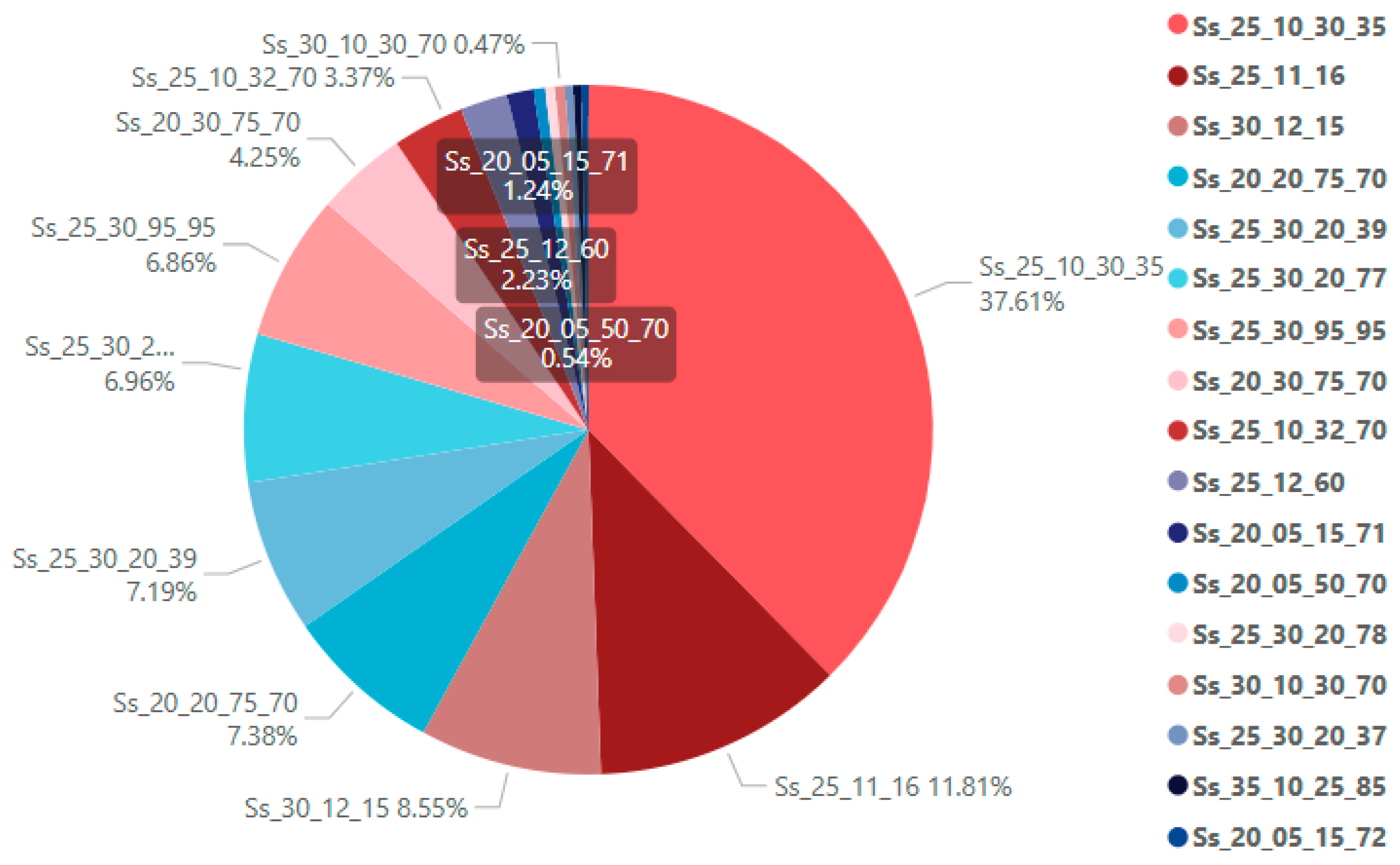

4.1. Data Preprocessing

| KNN imputation code |

| volume_data = df[['Volume']] imputer = KNNImputer(n_neighbors=5, weights='uniform') volume_imputed = imputer.fit_transform(volume_data) df['Volume'] = volume_imputed[:, 0] |

4.2. Model Training

4.3. Experimental Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Results Analysis

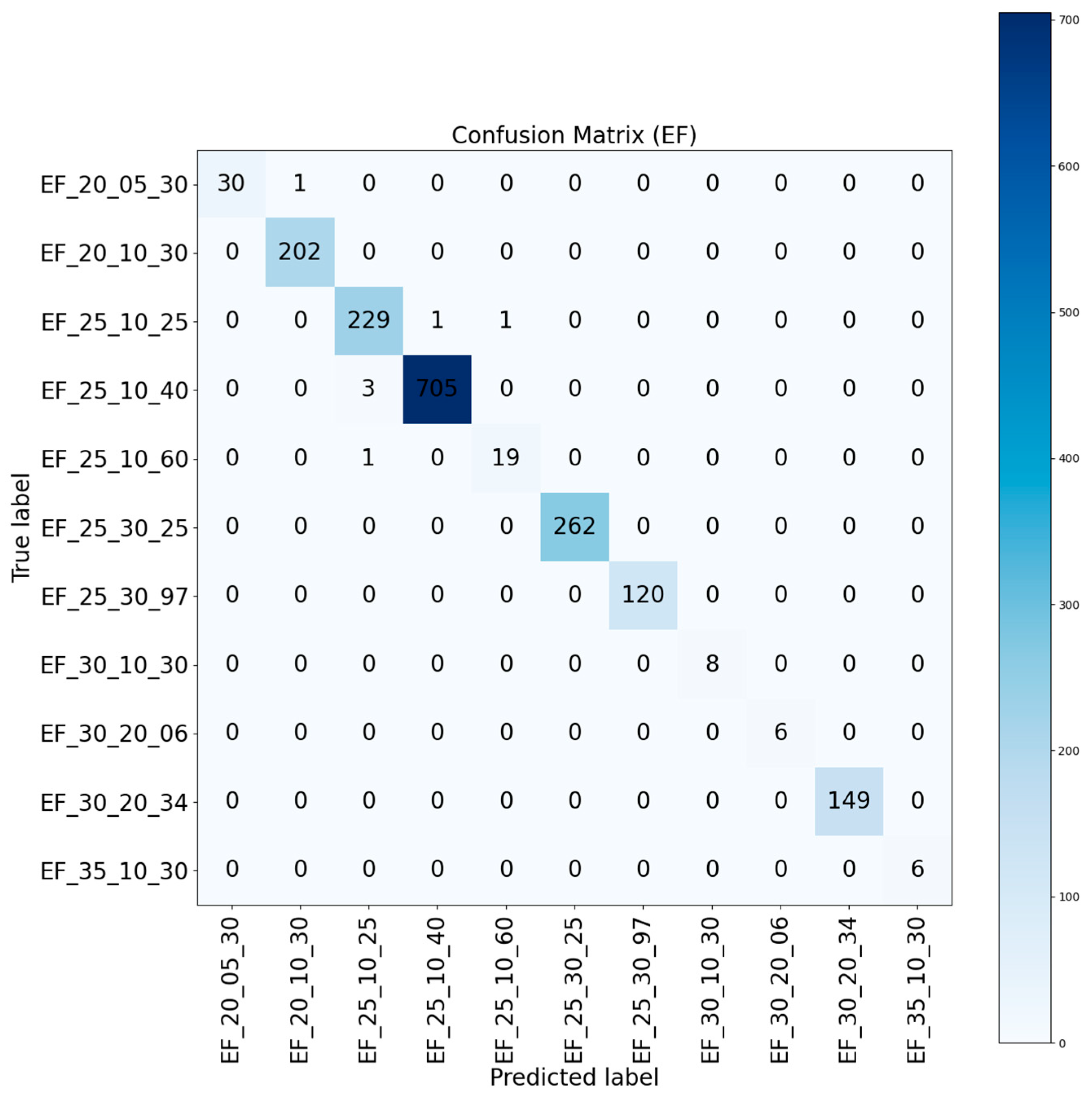

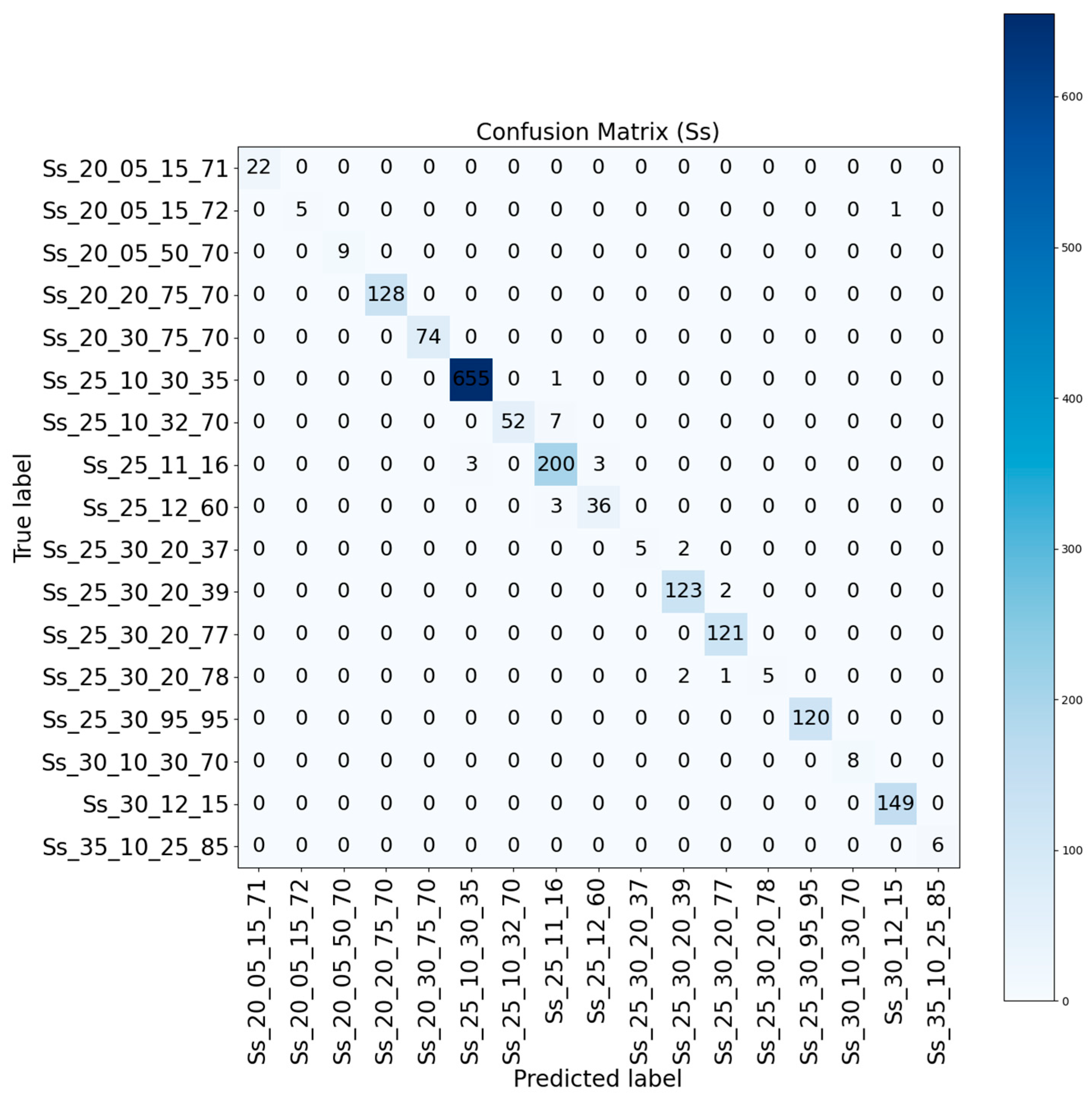

5.1.1. Classification Results Analysis

5.1.2. Feature Importance Analysis

5.2. Contributions

- A novel automatic classification method for BIM objects based on IFC data is proposed. By extracting feature variables from IFC data and training a Random Forest model, the method achieved over 99% classification accuracy in both EF and Ss coding tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness and robustness.

- The study successfully implements automatic classification and coding of BIM objects based on the Uniclass classification system (EF and Ss standards). This approach overcomes the traditional limitations of relying solely on geometric or functional features by employing a standardized classification framework, thereby enhancing the systematization, standardization, and engineering applicability of BIM object classification.

- For the first time, high-precision, fine-grained classification is achieved using only low-level detailed IFC data at LOD 200. The proposed method significantly reduces reliance on high-precision modeling data and substantially improves applicability during the early design stages (Early Design Stage) and low-LOD phases, offering a viable solution for intelligent management at the preliminary stage of BIM projects.

5.3. Comparison with Existing Methods

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

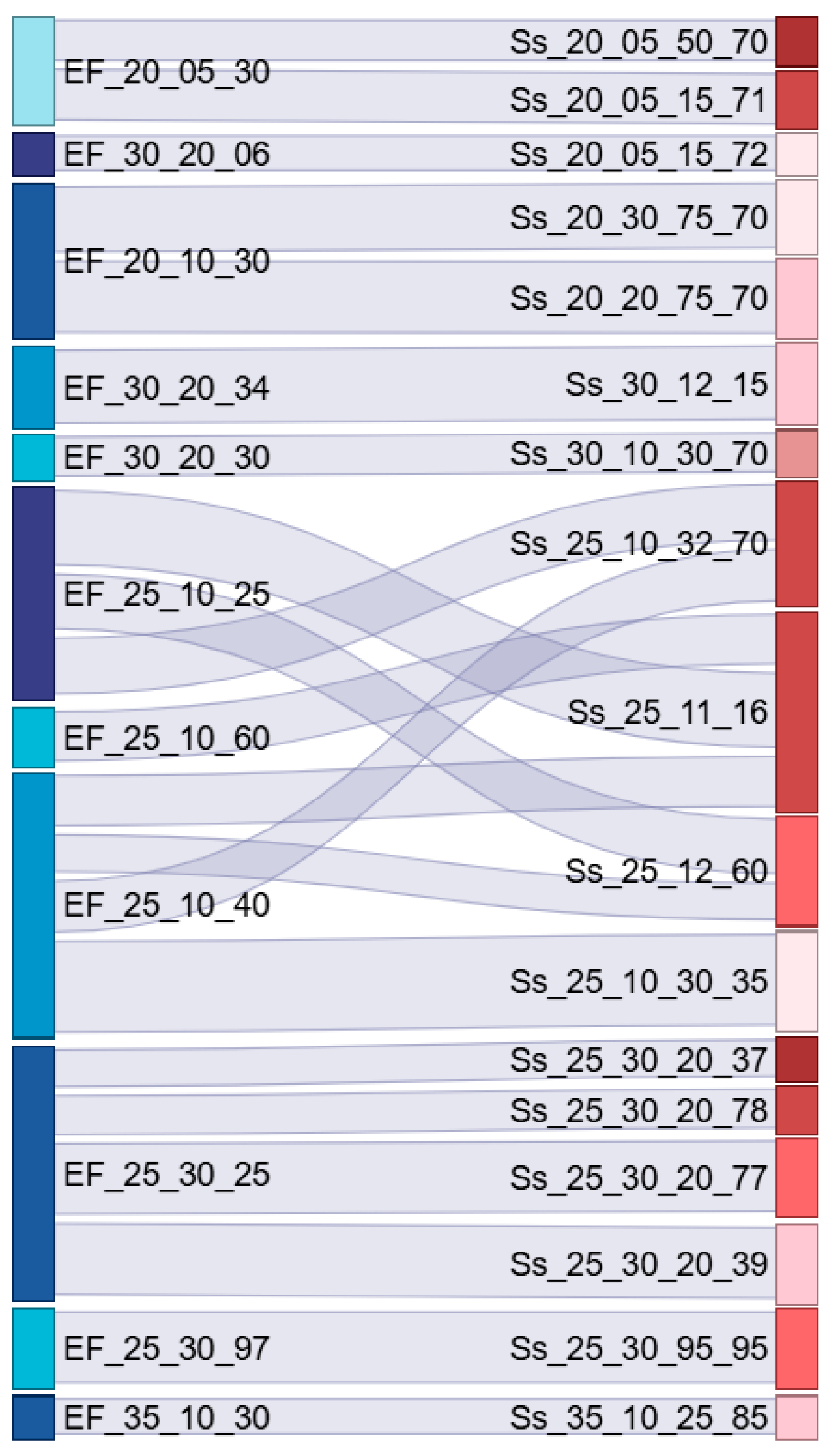

| Code | Title | Gr | Su | Se | Ob | SO | Description |

| EF_20_05_30 | 05EF | 20 | 05 | 30 | Foundations | ||

| EF_20_10_30 | 05EF | 20 | 10 | 30 | Framed structures | ||

| EF_25_10_25 | 05EF | 25 | 10 | 25 | External walls | ||

| EF_25_10_40 | 05EF | 25 | 10 | 40 | Internal walls | ||

| EF_25_10_60 | 05EF | 25 | 10 | 60 | Parapet walls | ||

| EF_25_30_25 | 05EF | 25 | 30 | 25 | Doors | ||

| EF_25_30_97 | 05EF | 25 | 30 | 97 | Windows | ||

| EF_30_10_30 | 05EF | 30 | 10 | 30 | Flat roofs | ||

| EF_30_20_06 | 05EF | 30 | 20 | 06 | Basement floors | ||

| EF_30_20_34 | 05EF | 30 | 20 | 34 | Ground floors | ||

| EF_35_10_30 | 05EF | 35 | 10 | 30 | External stairs | ||

| Ss_20_05_15_71 | 06Ss | 20 | 05 | 15 | 71 | Reinforced concrete pilecap and ground beam foundation systems | |

| Ss_20_05_15_72 | 06Ss | 20 | 05 | 15 | 72 | Reinforced concrete raft foundation systems | |

| Ss_20_05_50_70 | 06Ss | 20 | 05 | 50 | 70 | Reinforced concrete foundation and plinth systems | |

| Ss_20_20_75_70 | 06Ss | 20 | 20 | 75 | 70 | Reinforced concrete beam systems | |

| Ss_20_30_75_70 | 06Ss | 20 | 30 | 75 | 70 | Reinforced concrete column systems | |

| Ss_25_10_30_35 | 06Ss | 25 | 10 | 30 | 35 | Gypsum board partition systems | |

| Ss_25_10_32_70 | 06Ss | 25 | 10 | 32 | 70 | Reinforced concrete wall structure systems | |

| Ss_25_11_16 | 06Ss | 25 | 11 | 16 | Concrete wall systems | ||

| Ss_25_12_60 | 06Ss | 25 | 12 | 60 | Panel enclosure systems | ||

| Ss_25_30_20_37 | 06Ss | 25 | 30 | 20 | 37 | High-security doorset systems | |

| Ss_25_30_20_39 | 06Ss | 25 | 30 | 20 | 39 | Hinged doorset systems | |

| Ss_25_30_20_77 | 06Ss | 25 | 30 | 20 | 77 | Sliding doorset systems | |

| Ss_25_30_20_78 | 06Ss | 25 | 30 | 20 | 78 | Sliding folding doorset systems | |

| Ss_25_30_95_95 | 06Ss | 25 | 30 | 95 | 95 | Window systems | |

| Ss_30_10_30_70 | 06Ss | 30 | 10 | 30 | 70 | Reinforced concrete roof framing systems | |

| Ss_30_12_15 | 06Ss | 30 | 12 | 15 | Concrete plank floor systems | ||

| Ss_35_10_25_85 | 06Ss | 35 | 10 | 25 | 85 | Suspended external stair systems |

References

- Lee, D.-G.; Park, J.-Y.; Song, S.-H. BIM-Based Construction Information Management Framework for Site Information Management. Advances in Civil Engineering 2018, 2018, 5249548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, L.; Ding, L. A Framework for BIM-Enabled Life-Cycle Information Management of Construction Project. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2014, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BuildingSMART IFC. Available online: http://standards.buildingsmart.org/IFC/RELEASE/IFC4_1/FINAL/HTML/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Zhou, D.; Pei, B.; Li, X.; Jiang, D.; Wen, L. Innovative BIM Technology Application in the Construction Management of Highway. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sacks, R.; Kattel, U.; Bloch, T. 3D Object Classification Using Geometric Features and Pairwise Relationships. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2018, 33, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniclass by NBS. Available online: https://uniclass.thenbs.com/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Pupeikis, D.; Navickas, A.A.; Klumbyte, E.; Seduikyte, L. Comparative Study of Construction Information Classification Systems: CCI versus Uniclass 2015. Buildings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, T.; Sacks, R. Comparing Machine Learning and Rule-Based Inferencing for Semantic Enrichment of BIM Models. Automation in Construction 2018, 91, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Choi; H. Kim; S. Kim; M. H. Kim Scalable Packet Classification Through Rulebase Partitioning Using the Maximum Entropy Hashing. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2009, 17, 1926–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.T.; Yi, W.; Wang, H. Application of Machine Learning in Construction Productivity at Activity Level: A Critical Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gan, V.J.L.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Zhou, S. (Alexander) Automatic Fine-Grained BIM Element Classification Using Multi-Modal Deep Learning (MMDL). Advanced Engineering Informatics 2024, 61, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydgar, M.; Poirier, É. A.; Motamedi, A. Comparative Evaluation of Deep Neural Network Performance for Point Cloud-Based IFC Object Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 108303–108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Niu, M. Automatic Classification and Coding of Prefabricated Components Using IFC and the Random Forest Algorithm. Buildings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Chang, S.; Sparkling, A. BIM-Based Object Mapping Using Invariant Signatures of AEC Objects. Automation in Construction 2023, 145, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Fu, D.; Qiu, L.; Liang, Y.; Huang, C. A Semi-Explicit Practical Coding Method for Prefabricated Building Component Parts in China. Buildings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parece, S.; Resende, R.; Rato, V. A BIM-Based Tool for Embodied Carbon Assessment Using a Construction Classification System. Developments in the Built Environment 2024, 19, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.; Lee, G. Automated Classification of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Case Studies by BIM Use Based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Unsupervised Learning. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2019, 41, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkucu, D.; Ying, H.; Wang, Z.; Sacks, R. Classification of Architectural and MEP BIM Objects for Building Performance Evaluation. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2024, 61, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, W.B.; Koo, B.S. Ensemble-Based Deep Learning Approach for Performance Improvement of BIM Element Classification. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2023, 27, 1898–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; La, S.; Cho, N.-W.; Yu, Y. Using Support Vector Machines to Classify Building Elements for Checking the Semantic Integrity of Building Information Models. Automation in Construction 2019, 98, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austern, G.; Bloch, T.; Abulafia, Y. Incorporating Context into BIM-Derived Data—Leveraging Graph Neural Networks for Building Element Classification. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosho, T.D.; Oyedele, L.O.; Bilal, M.; Ajayi, A.O.; Delgado, M.D.; Akinade, O.O.; Ahmed, A.A. Deep Learning in the Construction Industry: A Review of Present Status and Future Innovations. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 32, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopazo, D.A.; Mahdjoubi, L.; Gething, B.; Mahamadu, A.-M. An Automated Machine Learning Approach for Classifying Infrastructure Cost Data. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2024, 39, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, F.; Aretoulis, G.; Giannoulakis, D.; Konstantinidis, D. Cost and Material Quantities Prediction Models for the Construction of Underground Metro Stations. Buildings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianzu, W.; Chaojie, Z. Machine Learning in Strategic Management Research: A Review and Prospects. Foreign Economics & Management 2025, 47, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Thedja, J.P.P.; Chi, H.-L.; Lee, D.-E. Automated Rebar Diameter Classification Using Point Cloud Data Based Machine Learning. Automation in Construction 2021, 122, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Ying, G.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Mei, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Li, B.; Ma, J.; Li, S. Classification of Failure Modes, Bearing Capacity, and Effective Stiffness Prediction for Corroded RC Columns Using Machine Learning Algorithm. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 102, 111982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Xin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W. Machine Learning for Defect Condition Rating of Wall Wooden Columns in Ancient Buildings. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2025, 22, e04458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitera-Kiełbasa, E.; Zima, K. Automated Classification of Exchange Information Requirements for Construction Projects Using Word2Vec and SVM. Infrastructures 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Jarén, R.; Arranz, J.J. Automatic Segmentation and Classification of BIM Elements from Point Clouds. Automation in Construction 2021, 124, 103576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KIEU, T.C. 志手一哉 ファセット型分類体系を用いたWBSの構築におけるテーブル間連携の可能性に関する分析. 日本建築学会技術報告集 2022, 28, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emunds, C.; Pauen, N.; Richter, V.; Frisch, J.; van Treeck, C. SpaRSE-BIM: Classification of IFC-Based Geometry via Sparse Convolutional Neural Networks. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2022, 53, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Uniclass Tables | Description |

| Activities (Ac) | The Activities table classifies the activities that take place in existing assets, or that need to be accommodated within them. |

| Complexes (Co) | The Complexes table classifies high-level groupings in the built environment and tends to describe a group of entities brought together in one place as a complex, for a particular purpose or multiple activities. |

| Entities (En) | The Entities table classifies individual parts of an asset, like buildings, bridges, or tunnels. |

| Spaces/ locations (SL) | The Spaces/ locations table classifies spaces where activities take place and locations where specific items or equipment can be found, often in linear infrastructure like pipelines, roads, and rail. |

| Elements/ functions (EF) | The Elements/ functions table classifies general elements like walls, decks, and roofs, which can be thought of as the main components of buildings, structures, towers or tunnels, and functions, which describe generic services required for asset operation such as piped gas supply, rail and paving heating, or waste collection. |

| Systems (Ss) | The Systems table classifies collections of products brought together to operate as systems, in order to provide a common purpose or solution. |

| Products (Pr) | The Products table classifies individual products used across the built environment, including those assembled to create systems, and objects located as part of asset operation or functions. |

| Tools and equipment (TE) | The Tools and equipment table classifies tools and equipment, such as plant machinery, vehicles, tunnel boring machines, formwork, scaffolding, and temporary hoardings across the full-range of built environment for the construction and ongoing maintenance and repair of assets. |

| Project management (PM) | The Project management table classifies requirements, information, and records for asset management and project management across the full lifecycle of the built environment, at all scales. |

| Form of information (FI) | The Form of information table classifies forms of information, often exchanged as part of asset management and construction projects, with codes for contract, quotation, room data sheet, bill of quantities, three-dimensional model, or invoice. |

| Roles (Ro) | The Roles table classifies the individual or organizational roles required in asset management and the successful delivery of built environment projects. |

| Risk (RK) | The Risk table is used to categorize various types of risks associated with the lifecycle of built assets, facilitating the identification, management, and communication of potential risks during the design, construction, and operation phases of a project. |

| Material (Ma) | The Material table classifies materials used in the built environment. |

| Properties and characteristics (PC) | The Properties and Characteristics table is designed to categorize various attributes and characteristics of built assets, supporting detailed description and management throughout the asset lifecycle, and enhancing consistency and traceability of information. |

| CAD and modelling content (Zz) | The Zz_ table supports CAD and modelling content to assist with clear and consistent layer naming in modelling platforms, and managing the various components required in digital drawings, models, and construction outputs. |

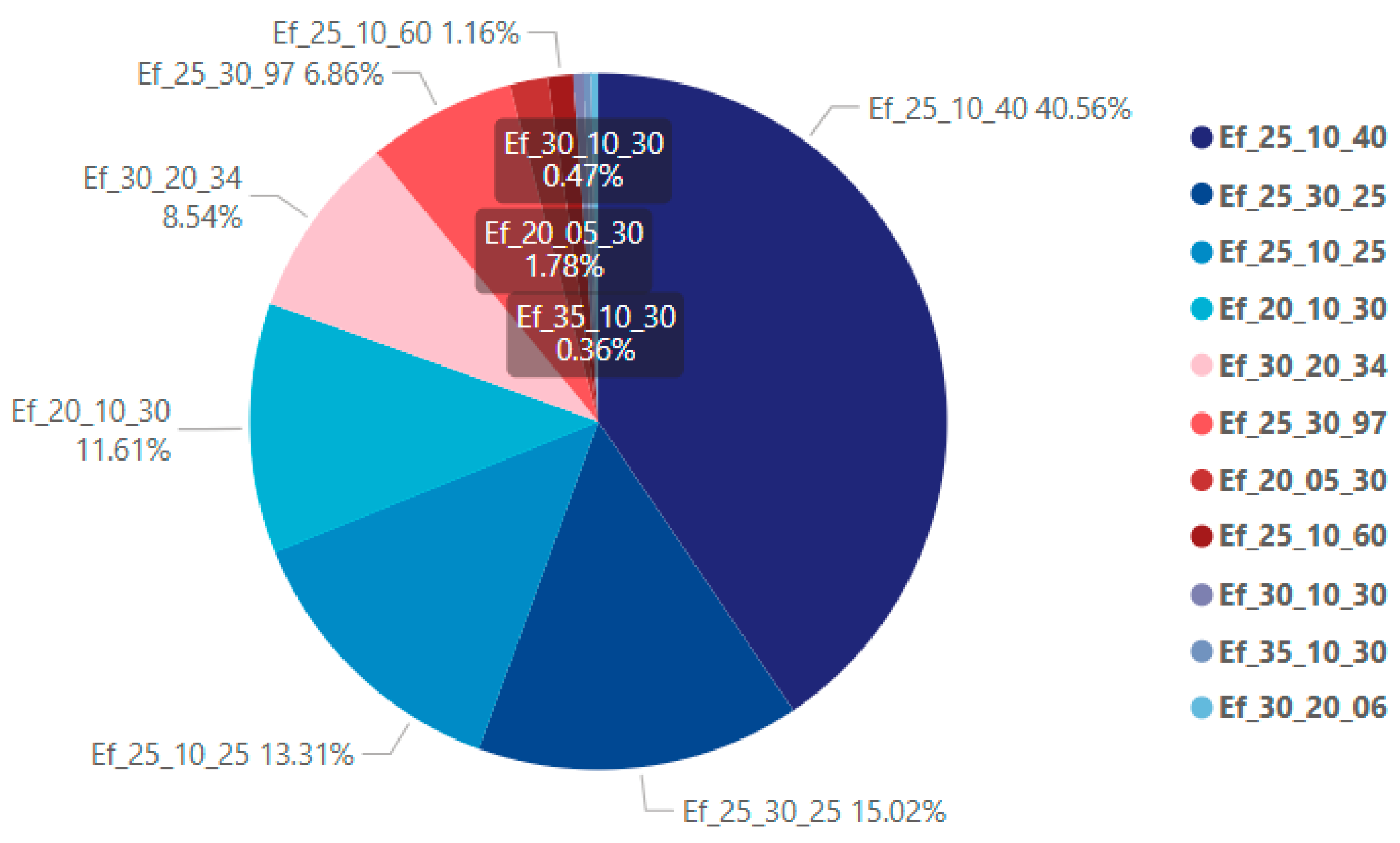

| Project | Site Area(m2) | Building Area(m2) | Number of Floors | Structure Type | Structural Systems |

| A | 221.44 | 167.00 | 6 | RC (Seismic Resistant) | Rigid Frame |

| B1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C | 463.65 | 261.73 | 9 | RC (Seismic Isolation) | Rigid Frame |

| D | 326.07 | 188.80 | 4 | RC (Seismic Resistant) | Wall Structure |

| E | 209.98 | 146.10 | 6 | RC (Seismic Resistant) | Rigid Frame |

| Actual Positive | Actual Negative | |

| Predicted Positive | TP (True Positive) | FP (False Positive) |

| Predicted Negative | FN (False Negative) | TN (True Negative) |

| Model | Precision EF |

Precision Ss |

Recall EF |

Recall Ss |

F1-score EF |

F1-score Ss |

Accuracy EF |

Accuracy Ss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| DT | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| SVM | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).