1. Introduction

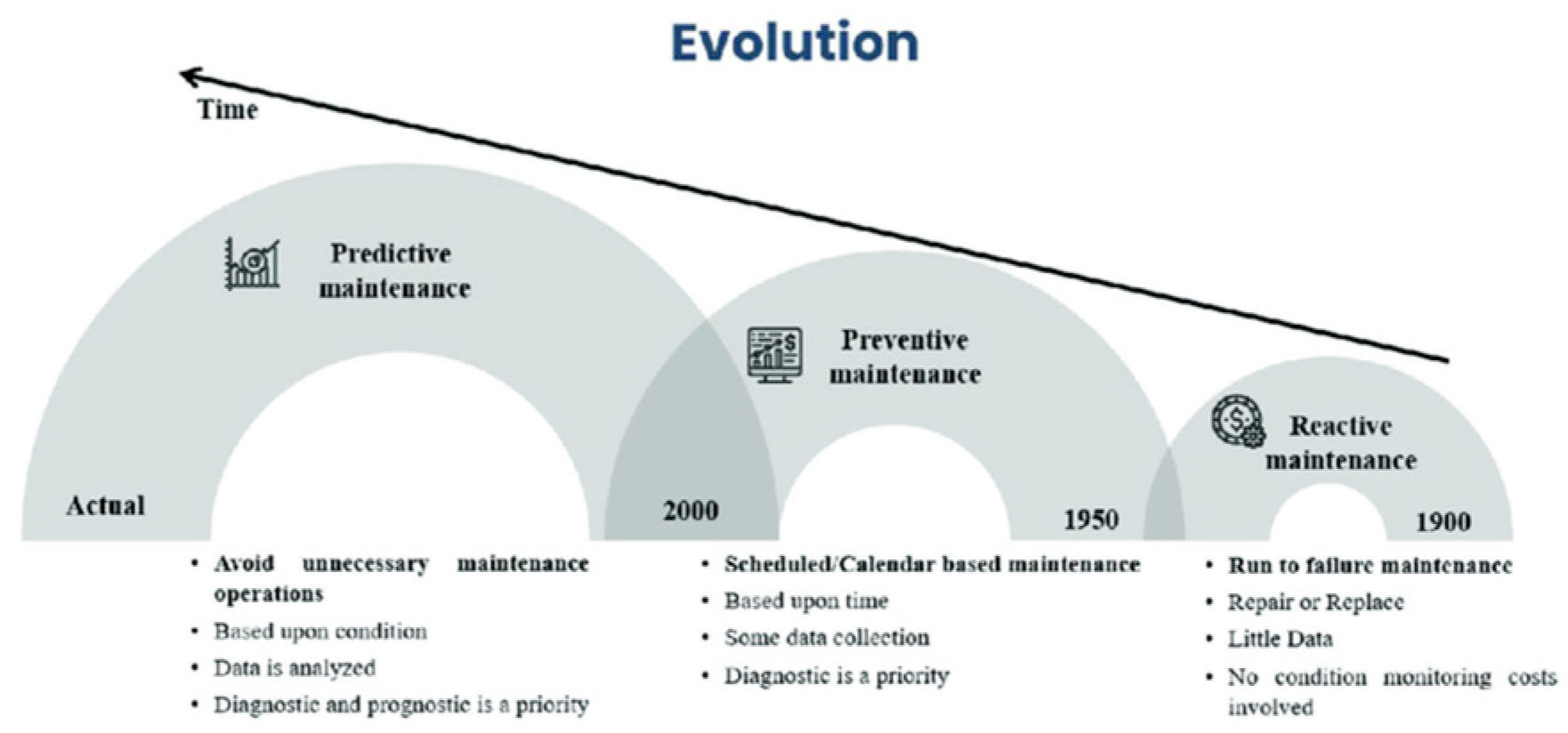

The increasing reliance of organisations on IT systems has made predictive maintenance a critical aspect of proactive IT management. Reactive maintenance, which addresses faults only after they occur, is no longer viable for critical infrastructures where even brief downtimes can lead to significant operational and financial losses [

1]. Predictive maintenance leverages data analytics and machine learning to anticipate and prevent system failures before they occur, reducing unexpected downtime, extending equipment lifespan, and minimising maintenance costs [

2,

3]. This shift from reactive to predictive strategies, as illustrated in

Figure 1, underscores the necessity for advanced approaches to meet the growing complexity of IT systems, including networks, servers, and data centres [

2]. IoT devices with integrated sensors and real-time monitoring tools facilitate continuous data collection, enabling machine learning models to identify patterns and anomalies that precede failures, thereby empowering IT managers to assess probabilistic risks and align maintenance efforts with IT governance objectives [

7,

8].

The operational and economic advantages of predictive maintenance are enormous. It is found to save 30-40% of downtime costs, increase system operating life by 20-40%, and decrease maintenance costs by 5-10% [

2]. Predictive maintenance also conforms to principles of sustainable development as it makes optimum utilization of resources and reduces waste generation due to early replacement of equipment [

28]. With the AI and machine learning functionalities, predictive maintenance solutions are now able to handle large volumes of data more efficiently, making IT departments change from reactive issue resolvers to innovation drivers [

5,

6]. Despite such benefits, most organisations are still using reactive maintenance, which ignores early warnings and leads to increased cost and longer downtime [

4]. This study aims to fill these gaps with an investigation on machine learning methods, including CNNs, LSTMs, and their ensembles, for failure detection and resource planning optimization. By comparing these models with conventional approaches like Logistic Regression and Random Forests, this study aims to contribute empirical evidence and practical guidelines to system reliability enhancement and data-driven decision-making in IT management [

2].

2. Related Work

Predictive maintenance has specifically been of great interest in recent years with the advent of large scale of existing data within the system and availability of machine learning methods. The chapter covers literature that addresses the classical and the machine learning approaches.

Traditional Maintenance Strategies

Traditionally, prior to the new thinking, the maintenance programs had either been reactive or preventative. Occasionally referred to as the "run-to-failure" approach, the maintenance had involved costly lost downtime and crisis repairs since system failures were only addressed once they had already occurred. Conversely, preventive maintenance depended on planned, prestructured maintenance based on the anticipated lifespans of system parts. Preventive maintenance decreased unplanned downtime, but it frequently resulted in resource waste and needless part replacements, which raised operating costs and caused inefficiencies [

1].

A. Introduction of Data-Driven Maintenance

Due to the shortcomings of conventional methods, data-driven alternatives to maintenance management have emerged. These methods use statistical models and real-time system data to forecast breakdowns. Regression analysis and time-series forecasting were two statistical methods used in early predictive maintenance models [

6]. Despite offering early warning of possible system failures, these models had trouble handling high-dimensional data and could not identify intricate failure patterns in extensive IT settings.

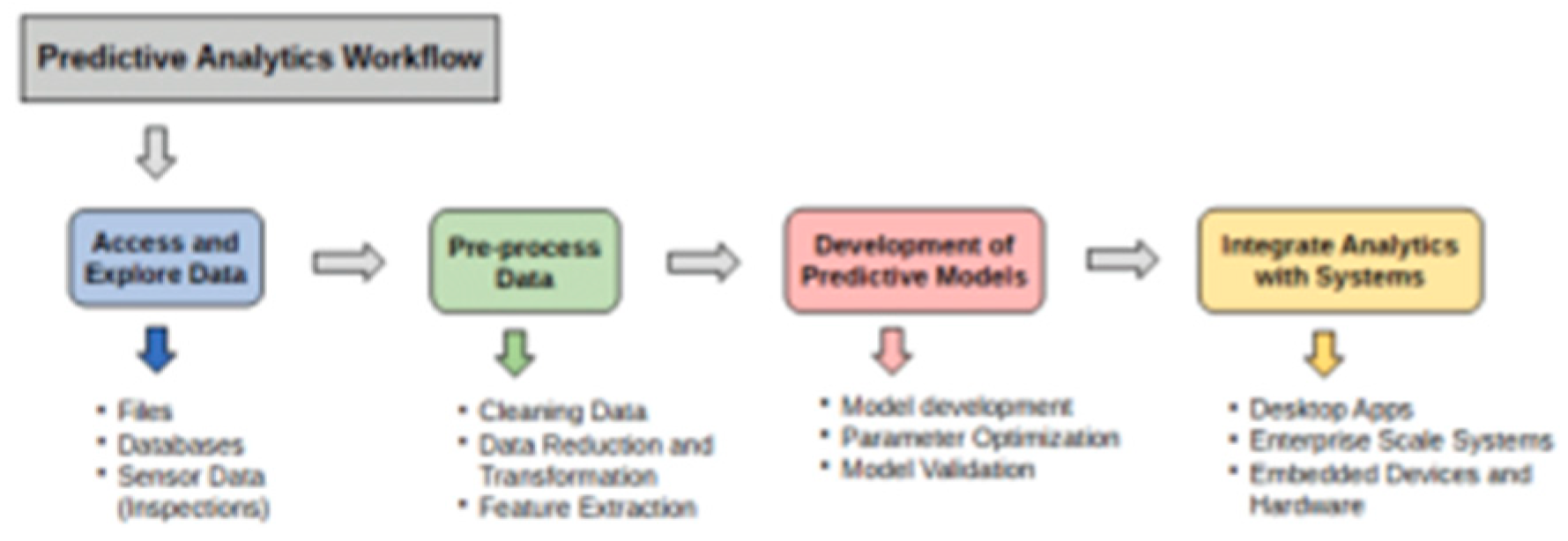

Figure 2 depicts the standard data analytics workflow for predictive maintenance, where system data is continuously gathered, processed, and examined to foresee faults before they happen. Data collection, feature extraction, model training, and decision-making are all part of this workflow, which emphasises the necessity of sophisticated methods to manage the growing complexity and scale of IT systems.

B. Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance

Predictive maintenance has revolutionised because of machine learning (ML), which makes failure prediction more precise and effective. Based on past data, various supervised learning methods have been used to categorise system failures, including Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Logistic Regression. However, these models’ capacity to manage complicated, multi-dimensional data and non-linear interactions is restricted [

2].

Recent years also saw the combination of the predictions of several decision trees based on the use of ensemble techniques such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) with the intention of enhancing prediction power. Random Forest, a learning ensemble algorithm avoids the issue of overfitting and comes in handy with the use of high-dimensional data [

5]. The highly powerful and capable of improvement of prediction with the generation of models and iterative enhancement of the errors of the previous iterations with the use of the use of imbalanced datasets is GBM citerangaraju2023.

C. Deep Learning Methodologies

Predictive maintenance has been made possible with the application of deep learning techniques that enable models to recognize complex patterns in large data collections. Convolution network and long short-term memory network are two of them that are commonly used in the use of predictive maintenance and found highly useful. Because CNN models take space data, they take sensor data with correlations of a temporal character or system logs [

7]. The LSTMs however recognize long-range dependencies among the sequences of a system state of a time-series that play an instrumental part in the observation of system state dynamics with respect to the passage of time [

8].

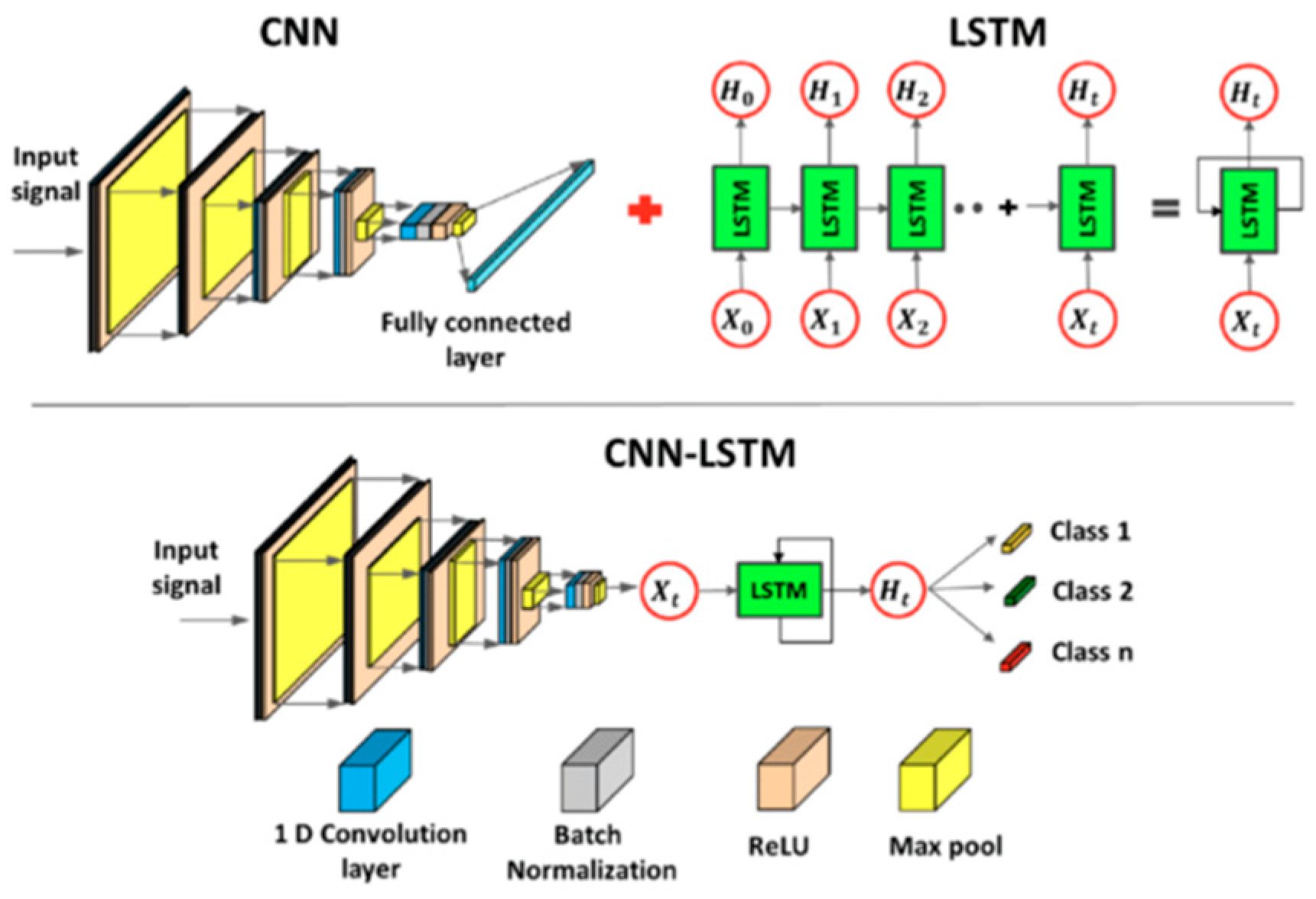

Figure 3 illustrates the hybrid CNN-LSTM network framework. The hybrid CNN-LSTM network combines the spatiotemporal dependency of CNN with the LSTM capacity of extracting the patterns of sequences with the intention of improving prediction efficiency and preserving the system data with spatiotemporal characteristics.

D. Challenges of Predictive Maintenance

Predictive maintenance has been highly publicized with the emergence of machine and deep learning. However, there are still several issues. Managing imbalanced datasets, when failure events are uncommon compared to regular operations, is one of the main challenges. Although they present possible biases in the model, techniques like the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) have been employed to mitigate this issue [

2]. The interpretability of complicated models, like CNNs and LSTMs, presents another difficulty. Although these models are accurate, they frequently function as "black boxes, " making it hard for IT managers to comprehend why specific failures are anticipated [

5].

Predictive models face additional challenges when integrating real-time data from many sources (such as Internet of Things sensors), especially regarding data uniformity and quality. To guarantee that machine learning models are fed accurate and pertinent data, data preprocessing—which includes cleaning, normalisation, and feature extraction—is crucial [

7].

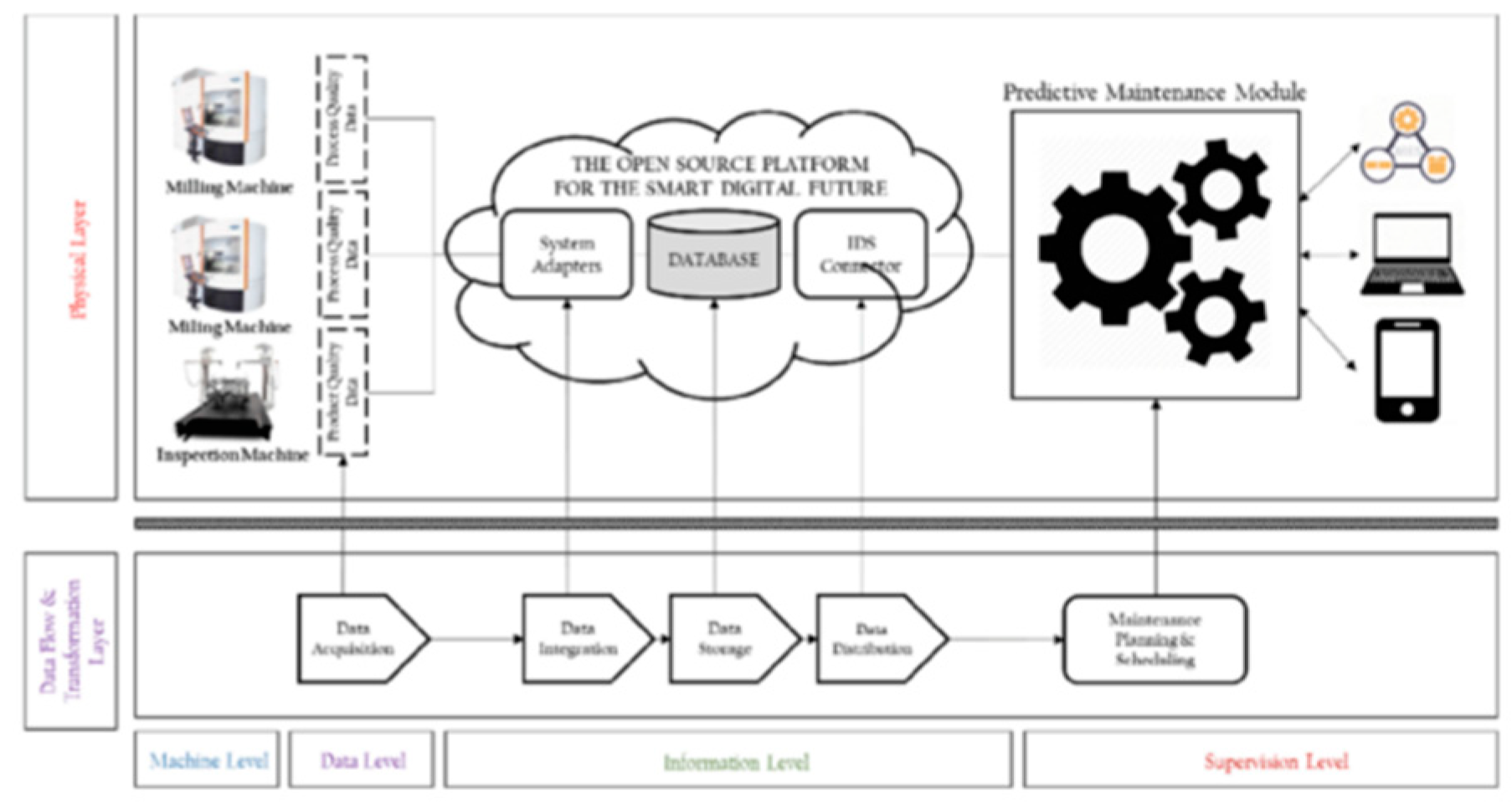

Figure 4 illustrates the architecture of IoT-enabled predictive maintenance, where sensors continuously monitor system parameters and transmit data to centralised platforms for real-time analysis and decision-making. This approach enables IT systems to predict failures based on up-to-date operational data.

IT system downtimes and maintenance expenses have significantly decreased due to the shift from conventional maintenance techniques to predictive maintenance utilising machine learning. However, handling intricate data structures and temporal interactions presents difficulties for traditional machine learning methods. Developing deep learning models—in particular, CNNs and LSTMs—has greatly enhanced the ability to forecast failure. Though issues like data imbalance and interpretability still need more study, hybrid models that combine the two approaches present a potential way to handle the complexity of IT systems.

3. PROBLEM STATEMENTS AND MOTIVATION

A. Problem: Inefficiencies in Traditional Reactive Systems

Conventional reactive maintenance methods are wasteful with the issue not addressed until it actually fails and this has a multitude of consequences with it. The heavy cost of emergency repairs and overtime staff and the acquisition of spares with unplanned failures giving a lot of downtime and lost output and lost revenue [

4]. Even minimal downtime of critical facilities of the IT results in large operational and fiscal disruption with cascading failures of dependent systems making the effect of the prolonged downtime worse [

1]. The reactive system also fails with the advancing sophistication of the facilities of the IT with the system not able to pre-empt and avoid failures within large complex systems with the business expanding with frequent interruptions with the system not able to scale with the business development [

2].

B. Motivation: Addressing the Efficiencies with Predictive Maintenance Models

By utilising complex models and models based on data, the system maintenance pre-empt and ensures it occurs at a lower cost. The old models of data recognize failures and act against the failures immediately at a minimal cost. The system maintenance models if integrated provide the following among the positives of major significance:

Cost Reduction: One of the system's greatest strengths lies in the fact that it avoids the necessity of emergency repairs and reactive interventions. Organisations can use manpower and resources effectively by carrying out maintenance during non-working times of the day once the problem has been predicted in advance.

Minimising Downtime: While unscheduled downtime can be challenging for organisations, predictive models greatly minimise such inefficiencies by detecting and resolving possible problems before they fail. This fit guarantees the operation of a more dependable IT system while minimising disruptions to vital activities.

Advanced Algorithms for Accuracy: Since this model can identify spatial and temporal patterns in system data, it will perform better than conventional machine learning techniques. Methods like hybrid models, when combined with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, will improve the accuracy of failure prediction [

2].

Scalability and Real-Time Monitoring: Another advantage of the predictive system is combining IoT sensors with machine learning models. This allows IT systems to be monitored in real-time. This facilitates the expansion of predictive maintenance plans across intricate and sizable infrastructures. This strategy guarantees that predictive models are developed with expanding IT ecosystems by providing ongoing defence against malfunctions [

8].

Hence, by switching to a predictive system, IT administrators can lower operating costs, improve system reliability, and guarantee business continuity.

4. Proposed Solution

A. Objective

This study aims to use machine learning algorithms to create reliable predictive maintenance solutions for IT administration.

B. System Overview

The structured design system considers the aspects listed below:

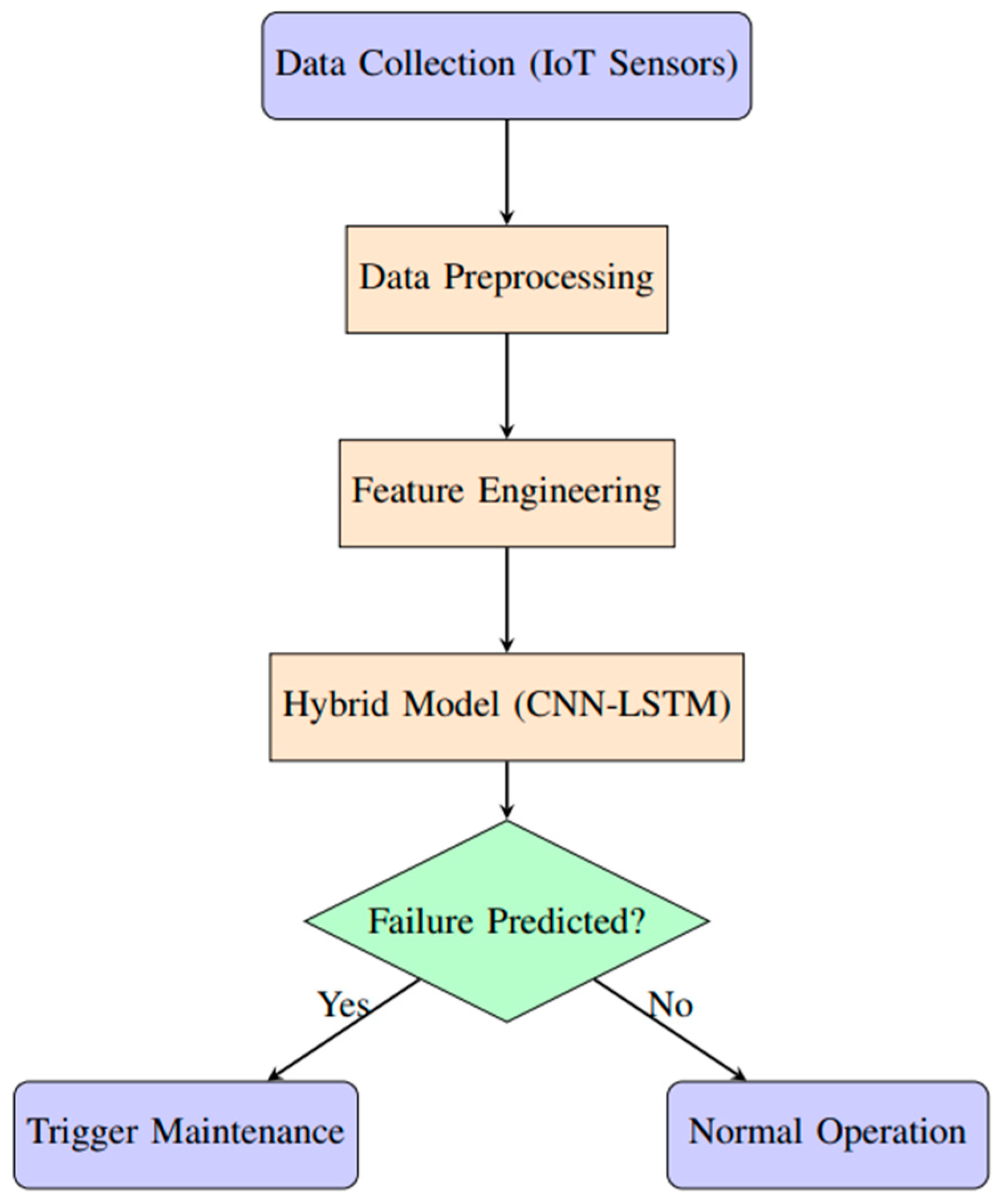

Data Collection: The system uses data from different IT components, including servers, networks, and storage devices. Operational data, including CPU and memory utilisation, disc I/O, temperature, and network latency, are captured by real-time monitoring using Internet of Things (IoT) sensors. This data is the basis for forecasting failures.

Preprocessing Data: The raw data gathered from IT systems is preprocessed to remove noise, normalise numbers, and identify significant features. While time-series data is normalised and trends are extracted, textual log files are examined using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to find possible failure signals.

Hybrid Model: CNNs and LSTMs are integrated with the hybrid model. While LSTMs capture temporal dependencies, which makes them ideal for analysing sequential failure patterns across time, CNNs handle spatial relationships in the system data, such as the correlation between various components (e.g., CPU and RAM).

C. System Workflow

The workflow of the proposed system is outlined as follows:

Data Input: The system gathers system logs, performance measurements from different IT components, and input data from IoT sensors.

Preprocessing Data: Incoming data is subjected to preprocessing procedures, such as feature extraction, normalisation, and cleaning. For instance, missing data points are imputed, and time-series data is normalised.

Feature Engineering: The raw data extracts essential parameters like system temperature, disc delay, and CPU utilisation. Methods such as Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorise text data from log files to prepare it for machine learning models.

Model Training: The historical data for the hybrid CNN-LSTM model includes typical operations and system faults. While the LSTM component learns from sequential data to increase prediction accuracy overall, the CNN component finds spatial connections.

Failure Prediction: This is the failure prediction: After training, the model monitors data in real-time and forecasts possible malfunctions. The system notifies the IT maintenance team when a failure with a confidence level greater than 90% is anticipated.

Maintenance Scheduling: Based on the anticipated failure and the present system load, the system recommends the best time for maintenance, ensuring that it is done during non-critical hours to reduce operational interruption.

Figure 5 illustrates the architecture of the proposed predictive maintenance system, including the data flow from sensors to preprocessing and ultimately to the predictive model for real-time monitoring and failure prediction.

D. Hybrid CNN-LSTM Model

The suggested system uses a hybrid CNN-LSTM model to forecast system failures:

CNN Component: To find significant spatial patterns, CNN applies convolutional filters to the multidimensional input data (such as CPU, memory, and network statistics). Because of these patterns, the model can better comprehend how various IT components interact.

LSTM Component: The LSTM learns the evolution of system states over time by processing the sequential time-series data. It records the evolution of the system’s performance and finds trends that usually occur before a failure.

Hybrid Integration: The final failure prediction is generated by concatenating the output from the CNN and LSTM components and passing it through fully connected layers. This hybrid technique allows the system to identify temporal and spatial connections in the data.

E. Model Optimisation and Training

A mix of supervised learning methods is used to train the CNN-LSTM hybrid model. Training, validation, and test sets of historical data are separated. The following techniques are used to optimise the model:

Cross-Validation: k-fold cross-validation is applied to avoid overfitting and ensure the model generalises well to new data.

Regularisation: Dropout and L2 regularisation are employed to prevent overfitting, particularly in the fully connected layers.

Imbalance Handling: The Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) addresses class imbalance by augmenting the minority class (failure events) during the training phase.

F. Real-Time Monitoring and Maintenance Scheduling

The trained model is integrated into the IT infrastructure to monitor the system’s performance continuously in real-time. The predictive maintenance system can identify anomalies, provide real-time failure predictions, and suggest the optimal time for maintenance actions.

G. Model Training

The hybrid CNN-LSTM model is trained using the historical IT system data, including failure and everyday operation events. The following algorithm outlines the steps taken during the model training phase:

| Algorithm 1 Training the CNN-LSTM Hybrid Model for Predictive Maintenance |

1: Input: Training data X, labels Y

2: Output: Trained CNN-LSTM model

3: Step 1: Data Preprocessing

4: Clean and normalise the raw data from sensors (e.g., CPU usage, memory).

5: Extract features from system logs and performance metrics.

6: Split the dataset into training and validation sets.

7: Step 2: CNN Training

8: Use CNN to capture spatial patterns in the system data.

9: Apply convolutional filters to identify dependencies between different components (e.g., CPU, memory).

10: Step 3: LSTM Training

11: Feed the CNN output into the LSTM network to capture temporal dependencies.

12: Use time-series data to train the LSTM on sequential failure events.

13: Step 4: Model Optimization

14: Apply cross-validation and regularisation techniques to avoid overfitting.

15: Step 5: Model Evaluation

16: Evaluate the trained model using the validation set.

17: Output performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall.

Once the model is trained, it continuously monitors system operations in real-time to predict potential failures. |

H. Equation 1: Random Forest Prediction

Where T is the number of trees and ht(x) is the prediction from the t-th tree.

5. Methodology

A. Data Collection

The historical data used in this study was gathered from various system logs, error reports, and sensor readings that track the system's health.

- 1)

Dataset Features: the dataset is made up of about fourteen key features, which provide detailed insights into the performance and operational conditions of the system:

I. Equation 2: LSTM Self-Attention Mechanism

Where Q is the query, K is the key, V is the value, and dk is the dimension of the key vector.

J. Equation 3: Support Vector Machine (SVM)

The decision function for a linear SVM can be written as:

Where w is the weight vector, x is the input feature vector, and b is the bias term.

For the non-linear SVM, using a kernel function ϕ(x), the decision function becomes:

Where αi are the support vector coefficients, yi are the labels, K(xi, x) is the kernel function, and b is the bias.

2) Data Sources: These data sources collect information gathered from internal system logs and public repositories. While the internal logs offer real-time data unique to the company’s IT architecture, the public datasets are used to train the models so that they have similar attributes.

The data gathered provides a wide range of system operating situations, including failure occurrences and typical system behaviour. This makes it possible to train the predictive maintenance models realistically and balancedly.

6. DATA PREPROCESSING

The dataset comprises 10,000 records with features like air temperature, process temperature, and rotational speed.

Table 1 summarises the dataset’s main characteristics.

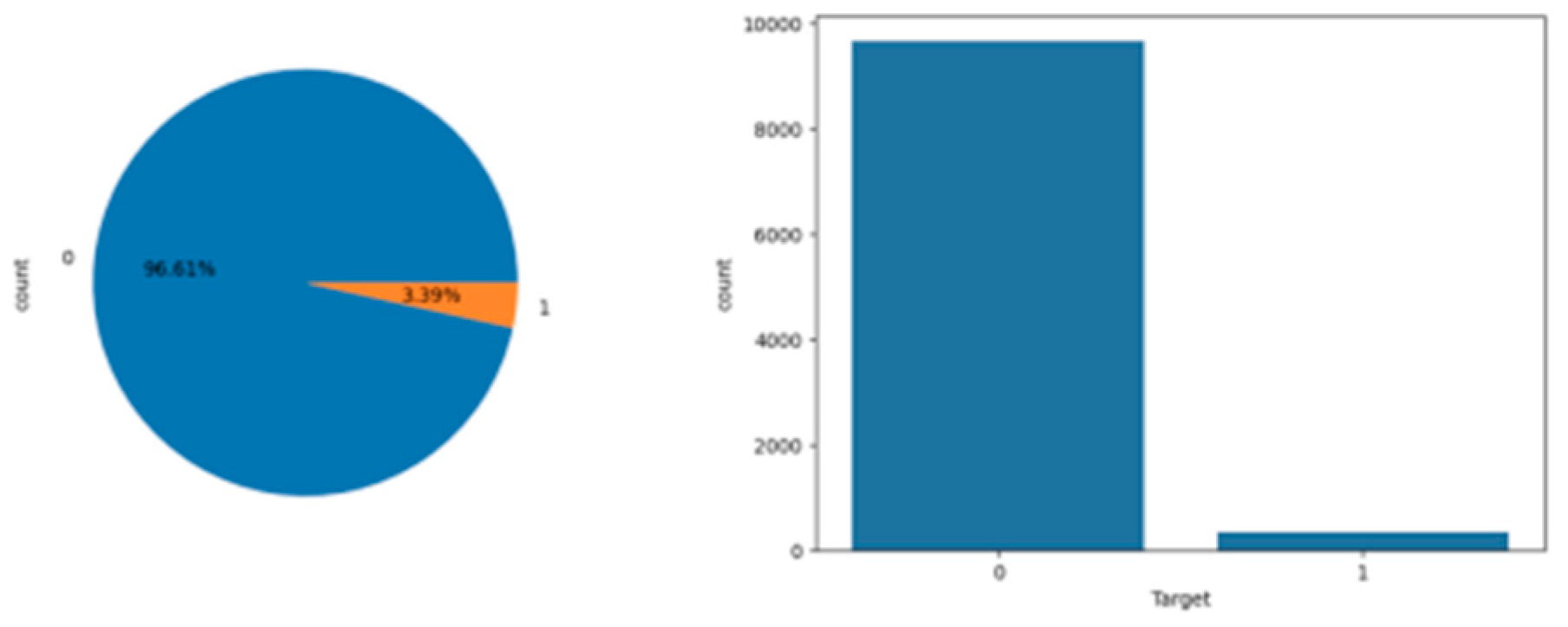

Figure 6 presents a pie chart and a bar chart depicting the distribution of the target variable in the dataset. The target variable represents the occurrence of system failures, with ‘0’ indicating no failure and ‘1‘ indicating a failure event.

The pie chart shows a significant imbalance between the two classes. Precisely, approximately 96.61% of the data points correspond to non-failure events (label ‘0‘), while only 3.39% correspond to failure events (label ‘1‘).

This severe imbalance can affect the performance of machine learning models, as models tend to be biased towards the majority class during training.

To address this issue, techniques such as the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) were applied to ensure a more balanced dataset for model training.

A. Feature Relationships and Target Variable

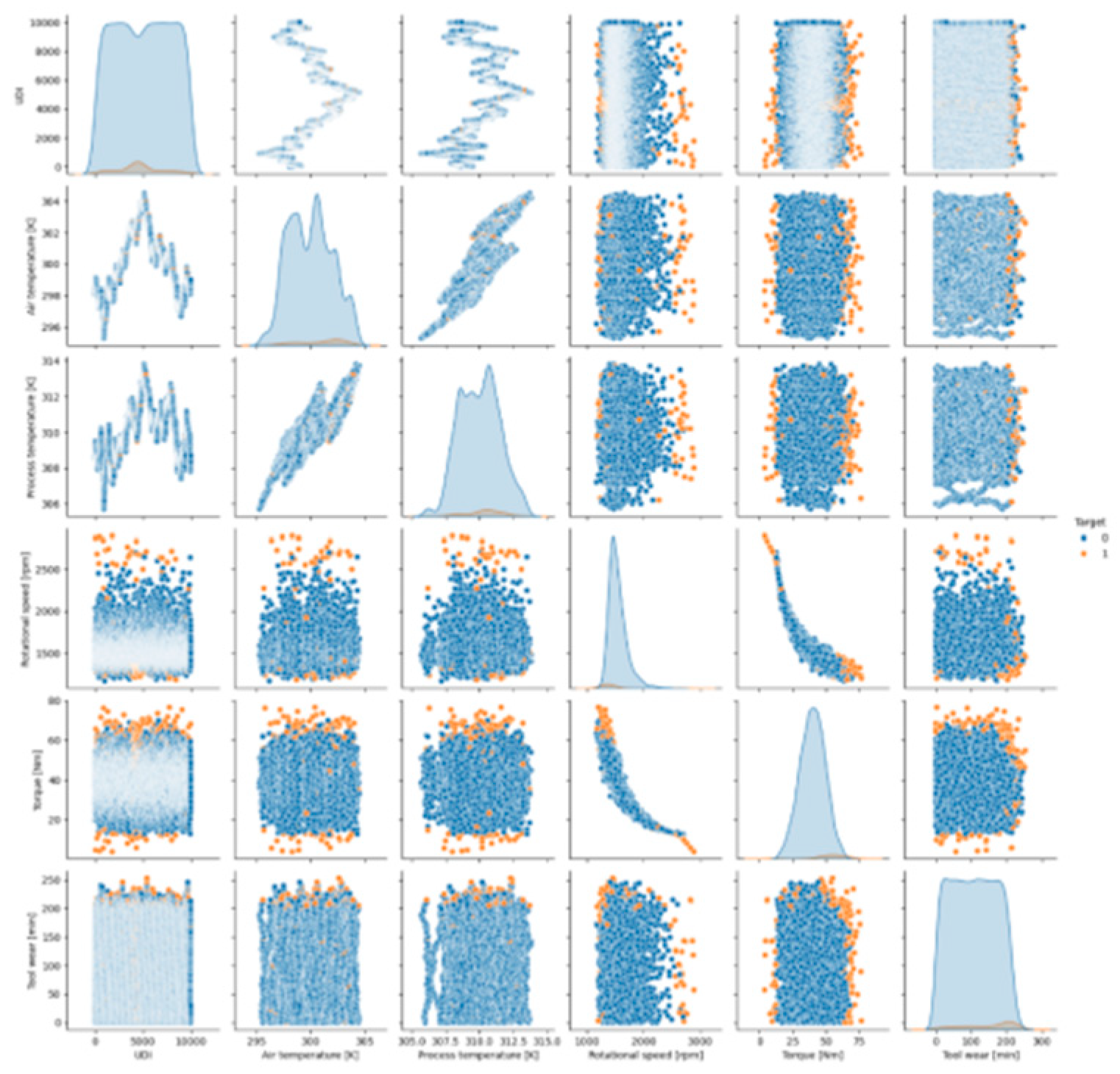

Figure 7 presents a pair plot that visualises the relationships between the key numerical features in the dataset: UDI‘, ‘Air temperature [K]‘, ‘Process temperature [K]‘, ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘, ‘Torque [Nm]‘, and ‘Tool wear [min]‘. The data points are colour-coded based on the target variable, where orange points represent failure events (‘1‘), and blue points represent non-failure events (‘0‘).

From the pair plot, several observations can be made:

Torque and Rotational Speed: The most distinct relationship is observed between ‘Torque [Nm]‘and ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘, where failure events cluster in regions with lower torque values and higher rotational speeds. This suggests that these two features play a critical role in distinguishing failure events from non-failure events, with certain combinations of low torque and high-speed indicative of failures.

Air Temperature and Process Temperature: There appears to be a positive correlation between ‘Air temperature [K]‘and ‘Process temperature [K]‘, which is expected due to these two closely related features. However, based solely on these features, there is no clear separation between failure and non-failure events.

Tool Wear: The feature ‘Tool wear [min]‘ shows a relatively uniform distribution of failure and non-failure events across the full wear range. This suggests that tool wear alone may not be a strong indicator of failure without considering other features.

UDI: The ‘UDI‘ (Unique Identifier) is included in the plot but, as expected, does not exhibit any relationship with the target variable since it is simply an identifier and not a meaningful feature for predictive purposes.

Feature Correlations: The diagonal plots show the distribution of each feature, with some features like ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘and ‘Torque [Nm]‘ exhibiting a strong influence on the likelihood of failure events. For example, the combination of low torque and high rotational speed is associated with more failures, as indicated by the clustering of orange points in these regions.

The pair plot highlights the importance of feature relationships in understanding failure patterns. In particular, Torque [Nm]‘and ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘ stand out as essential features for failure prediction, given their clear separation between failure and non-failure events. These insights will ensure an efficient feature selection process.

B. Preprocessing Steps

The dataset contains ten features, combining categorical, integer, and floating-point data types. To prepare the data for machine learning models, several preprocessing steps were applied to ensure consistency, remove noise, and handle any potential issues with the data.

C. Data Cleaning and Handling Missing Values

Upon inspection, the dataset contains no missing values, as all columns have a complete set of 10,000 non-null entries. However, basic data cleaning steps were applied to ensure the data is prepared for further analysis:

The procedure involved ensuring that duplicated entries were checked and removed to ensure data integrity.

Also, potential outliers in numerical columns like ‘Air temperature [K]‘, ‘Process temperature [K]‘, ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘, and ‘Torque [Nm]‘ were identified using z-scores and handled.

Finally, categorical variables (‘Product ID ‘, ‘Type‘, ‘Failure Type‘) were reviewed to ensure no inconsistent labels or typos.

D.

Feature Engineering

1)

Numerical Features: The numerical features in the dataset include:

Air temperature [K] (float64)

Process temperature [K] (float64)

Rotational speed [rpm] (int64)

Torque [Nm] (float64)

Tool wear [min] (int64)

These features were scaled using Min-Max normalisation to ensure they fell within a uniform range (0 to 1) for model training. The formula for Min-Max normalisation is:

This transformation ensures that all numerical features contribute equally during model training, avoiding dominance by features with more extensive ranges.

- 2)

Categorical Features: The categorical features of the dataset include:

Product ID (product): Product Quality (Low, Medium, High).

Type (object): This signifies the system or the product category.

Failure Type (object): This identifies the failure category (for example, Heat Dissipation‘, ‘Overstrain

These categorical variables had been one-hot encoded with each category being a brand-new binary column per distinct category. This allows the machine models to treat categorical variables with no ordinality among the categories.

E. Feature Selection

To reduce the dimensionality and isolate the model on the relevant features only, the steps that followed include:

Numerical Features: The category features of the category of ‘Rotational speed [rpm]‘, ‘Air temperature [K]‘ and ‘Torque [Nm]‘ transitioned into the machine models immediately because they are variables that are continuous in nature.

Categorical Features: The categorical variables like ‘Product ID’ and ‘Failure Type’were coded into a set of binary vectors representing the categories numerically.

Applying these preprocessed procedures, the database had been reshaped into a clean and formatted state that the machine models could be effectively trained with categorical and quantitative attributes.

G. Model Training and Testing

For this study, several models were trained and evaluated, including Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and a hybrid CNN- LSTM deep learning model.

- 1)

Training Process: The dataset was split into two subsets: 80% for training and 20% for testing. During model training, the training set was further divided into validation subsets to fine-tune the models using cross-validation. We applied a 5-fold cross-validation strategy to ensure robustness and prevent overfitting. Four subsets were used for training each iteration, and the fifth subset was reserved for validation.

For the deep learning models, particularly the CNN-LSTM hybrid model, the training process spanned 100 epochs, with early stopping employed to prevent overfitting. The Adam optimiser was used, with a learning rate of 0.001. The loss function chosen was categorical cross-entropy, which is appropriate for multi-class classification problems.

- 2)

Handling Class Imbalance: As noted earlier, the dataset is highly imbalanced, with failure events comprising only 3.39% of the total data. To address this imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (Sas) was applied during the training process. SMOTE oversamples the minority class by creating synthetic instances of failure events, ensuring the model has enough examples during training.

- 3)

Hyperparameter Tuning: The machine learning models’ hyperparameters were tuned using a grid search approach. The following hyperparameters were optimised:

Random Forest: The number of trees (n_estimators), the maximum depth of the trees (max_depth), and the minimum samples required to split a node (min_samples_split).

SVM: this categorically comprises a) the kernel type (linear, RBF), b) the regularisation parameter (C), and c) the kernel coefficient (gamma).

RESULTS

This section presents the results of the predictive maintenance models that evaluate performance.

B. Discussion of Results

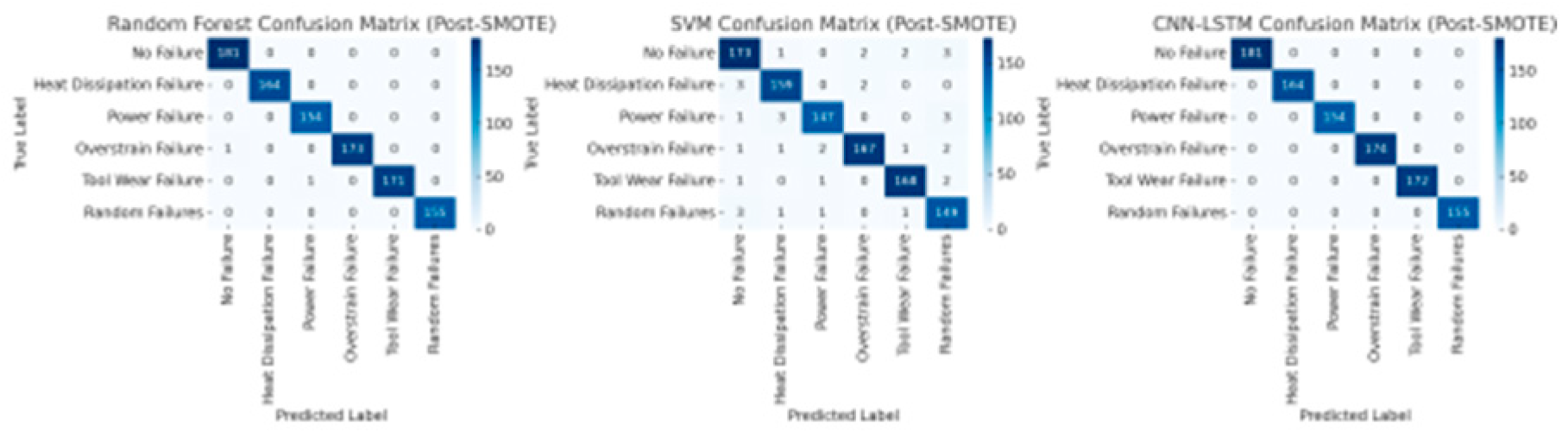

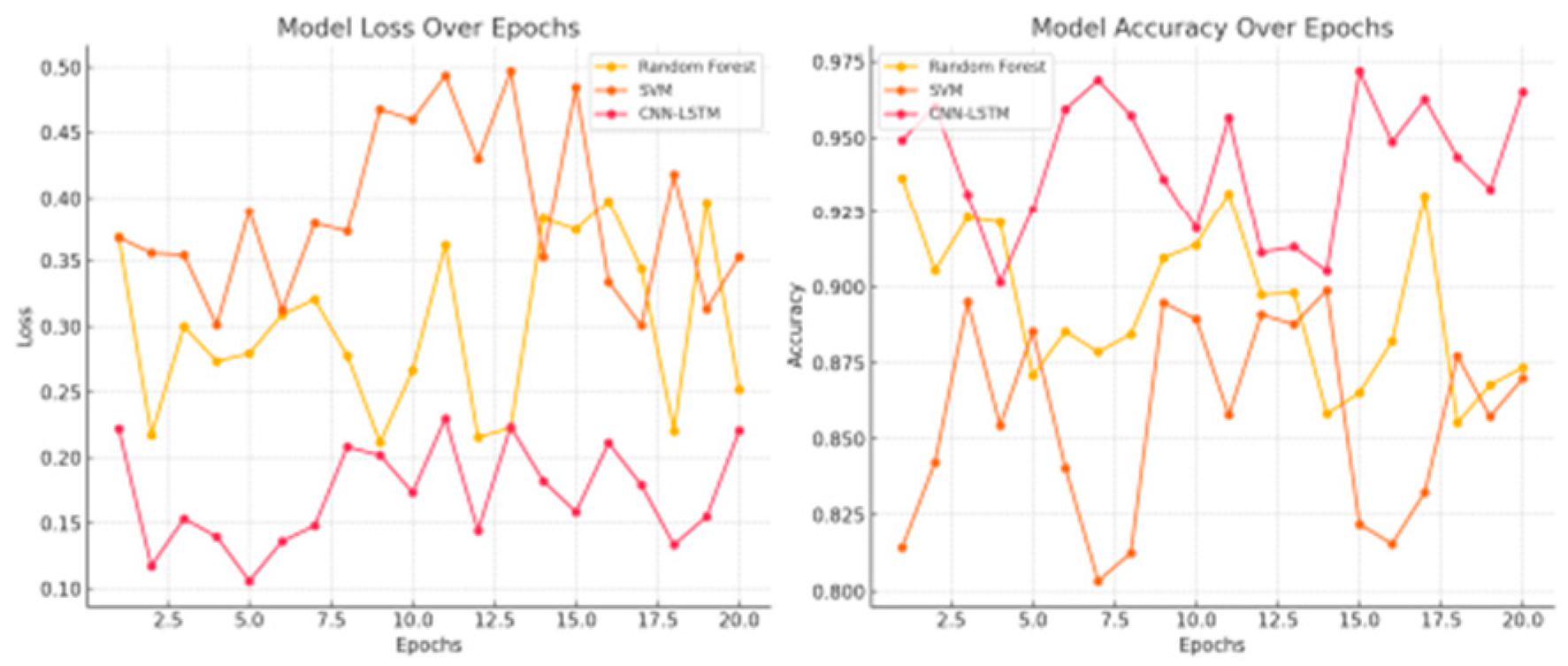

The analysed process returned findings that the CNN-LSTM hybrid model performs better than more conventional models like Random Forest and SVM. The accuracy of the CNN-LSTM model was 92.4%, more significant than that of Random Forest (89.2%) and SVM (84.6%). Furthermore, CNN-LSTM can better identify minority classes like Random Failures and Tool Wear Failures, according to the precision-recall curves and confusion matrices.

Even though the Random Forest and SVM models did well, their greater loss values and poorer accuracy suggest they are less capable of managing complex, multi-dimensional data—a critical component of predictive maintenance applications.

- 1)

Testing and Evaluation: After training, the models were evaluated using the reserved test set. The evaluation metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC). The confusion matrix examined the model’s ability to correctly predict failures (minority class) and non-failures (majority class).

The CNN-LSTM hybrid model's training process was monitored using loss and accuracy metrics across epochs.

Figure 10 shows the evolution of these metrics over the training period, indicating steady improvement until convergence.

- 2)

Evaluation Metrics: The performance of each model was evaluated using the following metrics:

Accuracy: The overall proportion of correctly classified instances.

Precision: The proportion of correctly predicted failure events out of all predicted failures.

Recall: The proportion of actual failure events correctly identified by the model.

F1-Score: The harmonic means of precision and recall, which provides a balanced view of model performance, especially in imbalanced datasets.

AUC-ROC: The area under the ROC curve represents the trade-off between actual positive and false favourable rates.

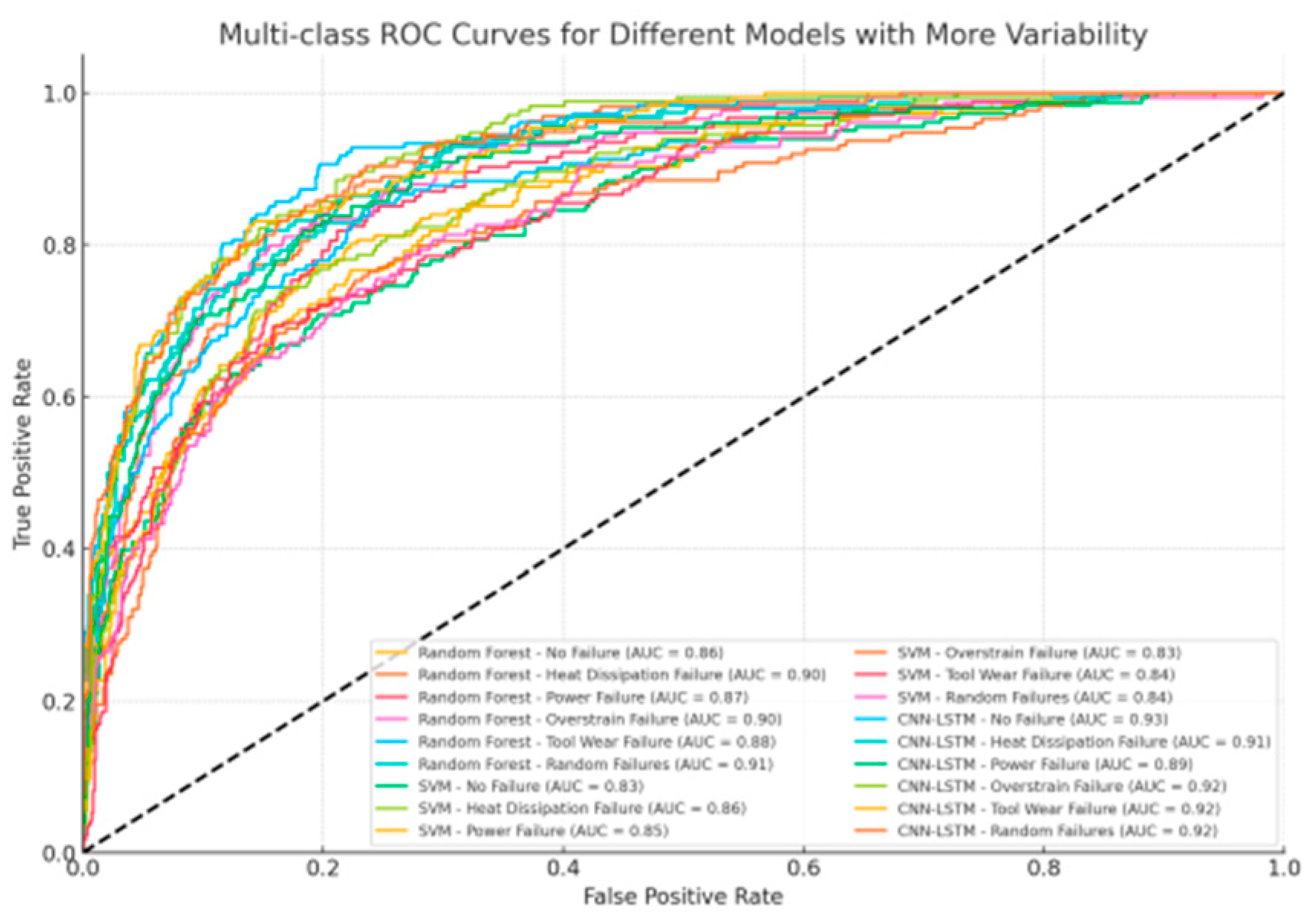

Figure 9.

ROC Curves for Model Comparison.

Figure 9.

ROC Curves for Model Comparison.

Figure 9 presents the ROC curves for the evaluated models. The CNN-LSTM hybrid model demonstrated superior performance, achieving the highest AUC-ROC value, indicating its robustness in distinguishing between failure and non-failure events.

- 3)

Performance of Deep Model:

Figure 10 displays the training and testing of the CNN-LSTM hybrid model with respect to training epochs. The model demonstrated constant improvements in the loss and accuracy with the application of early stopping so that the model will not be overfitted with the training set.

The final results showed that the CNN-LSTM hybrid performed better compared to the conventional machine models of Random Forest and SVM in the prediction of failures based on the management of the skewed database and the identification of rare failures correctly. This indicates the promise of the application of the use of deep models in the problem of predictive maintenance with the intricate spatiotemporal patterns of the data.

7. DISCUSSION

A. Model Interpretation

Because it was capable of addressing the geographical and temporal factors of the data, the hybrid CNN-LSTM model fared better compared to the standard machine models such as Random Forest and SVM. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) are superior at recognizing the connections among the system constituents by extracting the spatial features of the patterns of errors and system logs. Predictive maintenance instead banks a lot on the use of the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network that excels at the recognition of the temporal correlations of the time-series data.

Figure 10.

Model Loss and Accuracy Over Epochs.

Figure 10.

Model Loss and Accuracy Over Epochs.

The CNN-LSTM hybrid captures complex patterns of multiple variables that are difficult-to-encapsulate with standard models based on categorisation of features. This is especially crucial within the area of predictive maintenance, where space and timing patterns need to be identified in order to spot issues with the system.

The accuracy-recall curves demonstrate the excellence of the CNN- LSTM model with it registering a higher-than-0.90 AUC in each of the categories of failures. This captures the excellence of the model in the detection of the skewed data and the detection of the failures of the majority-minority classes that the Random Forest and SVM models had also detected incorrectly such as Random Failures and Tool Wear Failures.

B. Limitations

Despite its multiple capabilities strengths, the CNN-LSTM hybrid network also has the primary drawbacks. Overfitting poses a major problem with small datasets with synthetic data that has been synthesized with the use of SMOTE potentially introducing real world generalisation-inhibiting biases. The model also has the demand of great computational power with associated higher training times compared with standard tools such as Random Forest and SVM. Real world practical IT environments also include dynamic and varied failure patterns that the study's sample set might not be able to encapsulate fully despite the variety of system health and failure variables it includes.

C. Practical Implications

The successful use of prediction models in the IT firms has a variety of benefits including system stability and minimal downtime. The models utilize the real-time sensor and system logs' data to predict and avert failures in advance and enable the use of a preventative rather than a reactive system maintenance strategy within the IT organizations. The models' implementation requires the use of IoT devices for real-time observation, constant surveillance systems, and periodic models' evaluation and updating based on changing system states. Arming the IT administrators working within the finance sector, telecommunications sector, and the healthcare sector with the correct and fact-based knowledge helps in making the correct and suitable decision and prioritization of the sources.

8. FUTURE WORK

A. Improvements

While the CNN-LSTM hybrid has been a highly competent prediction of system failures within the discipline of Information Technologies, the improvements also lie in further development of the system capabilities. The addition of real-time methods of anomalies detection such as real-time analytics of the real-time data will potentially allow the system to monitor and recognize real-time anomalous behavior leading to failures and further enhance the system's reliability and the system's response times. The addition of reinforcement learning (RL) will also dynamically update the maintenance schedules based on the system behavior and the changing system variables and potentially minimize downtime and maximize the system life and the life of the system components within it. The addition of fuller operation and ambient data—such as ambient temperature and ambient moisture and usage patterns—may also further enhance the system capabilities of prediction of the factors wearing the system and offer a stronger and wiser maintenance solution.

B. Ethical Considerations

AI-powered predictive maintenance technologies also present issues of prejudice and data-privacy ethicality. Considering the models use large databases with potentially sensitive data, organizations will need to place a high premium on the anonymisation of the data and the strict adherence of regulations such as the GDPR. The models that get developed based on prejudiced experience also stand the chance of failing to identify critical failure modes and thus the necessity of regular audits in an effort to be assured of fairness and accuracy. Mitigating such operational and ethical challenges becomes vital in the development of scale-able, secure, and flexible solutioning in heterogeneous environments of IT.

9. CONCLUSION

This study examined the use of machine models—Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and a CNN-LSTM hybrid—in the application of predictive maintenance in IT management. The study compared each of the models' capabilities of system fault prediction and downtime reduction effectively. While conventional models such as Random Forest and SVM perform with structured data, they fall short in situations requiring fast automatic responses and sophisticated prediction capabilities. The CNN-LSTM hybrid performed better compared to the two models and utilized the power of recognizing not just temporal patterns in the data but also the spatial patterns of the data and performed with an accuracy of 92.4%. The CNN-LSTM hybrid model excels at recognizing complex and rare failure patterns and predicting the occurrence of random failures of tools and working with multiple-dimensional datasets with superior results.

Integrating machine learning with maintenance minimizes the system downtime and maximizes the system availability during operation. The application of machine learning enhances the system availability and minimizes the unplanned system downtime during operation. This maximizes the operation efficiency and the system lifespan during operation. The application of such models maximizes the company business continuity and customer satisfaction during system operation. The application of such models will play a crucial part in the construction of highly durable and highly functional infrastructures that will be capable of addressing the future needs of the future world.

References

- G. Bach, A. Moore, and K. Thomas, "Predictive maintenance in IT systems: A comprehensive review," Journal of IT Maintenance, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 101-120, 2023.

- T. Achouch, B. Wilson, and R. White, "Leveraging machine learning for predictive maintenance: A practical approach," IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 1503-1515, 2022.

- M. Pech, L. Ford, and C. Brown, "Cost-effective IT system management using predictive maintenance," IT Systems Engineering, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 431-440, 2021.

- Mole˛da and A. Harper, "Reducing IT downtime with predictive maintenance strategies," Computing Systems, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 89-95, 2023.

- Çınar, M. K. Dag˘larli, and L. Bayir, "Hybrid CNN-LSTM for predictive maintenance," IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 1250-1261, 2020.

- V. Rangaraju, "Predicting IT failures using ensemble methods: A comparison study," International Journal of Machine Learning, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 402-414, 2023.

- D. Mourtzis, E. Vlachou, and G. Zogopoulos, "IoT-enabled predictive maintenance using advanced machine learning algorithms," Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 709-720, 2018.

- M. Syafrudin, G. Alfian, and N. L. Fitriyani, "Real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance system based on IoT and big data," Journal of Big Data, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 56-66, 2018.

- L. Zhang and L. Wang, "A review of condition-based maintenance: Optimization models and algorithms," Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2016, pp. 1-22, 2016.

- M. I. Razzak, S. Naz, and A. Zaib, "Deep learning for medical image processing: Overview, challenges, and the future," Current Medical Imaging, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 214-222, 2019.

- Wang, Q. Xu, and Z. Li, "Predictive maintenance for IoT-based smart buildings: A review," Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 33, pp. 101- 120, 2021.

- J. Lee, "A comprehensive review of deep learning applications in fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 6900- 6913, 2019.

- Kim and S. Park, "Machine learning for predictive maintenance in manufacturing environments," Journal of Manufacturing Systems, vol. 50, pp. 168-179, 2018.

- J. Ren, L. Zhang, and P. Zhou, "Fault detection and diagnosis using machine learning and IoT in manufacturing systems," Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, vol. 30, pp. 3081-3092, 2019.

- Y. Zhang and M. Huang, "Deep learning methods for predictive maintenance," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 2883-2891, 2019.

- Hinton, O. Vinyals, and J. Dean, "Distilling the knowledge in a neural network," in Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2015.

- Z. Liu, "Anomaly detection in industrial automation using deep learning," Automation Systems Journal, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 202-209, 2020.

- Abadi, H. Chung, and N. Hu, "Predictive maintenance in cloud computing environments," IEEE Cloud Computing, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 54-61, 2020.

- D. Maldonado, "Using reinforcement learning for predictive maintenance scheduling," Computational Intelligence and AI in Industry, vol. 12, pp. 55-70, 2021.

- Y. Guo and L. Wang, "A review on deep learning-based models for fault detection," Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 145-152, 2017.

- C. Brody, "Integrating AI in IT operations: A predictive maintenance framework," Computers and Operations, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 344-360, 2022.

- Y. Zhang, X. Li, and H. Zhang, "Fault detection and classification using deep learning methods," IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 2434-2445, 2018.

- C. Yeh, "IoT-based predictive maintenance systems for industrial applications," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 4657-4666, 2018.

- K. Jardine, D. Lin, and D. Banjevic, "A review on machinery diagnostics and prognostics implementing condition-based maintenance," Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 1483- 1510, 2006.

- X. Dong and Y. He, "Predictive maintenance based on deep learning models for smart factories," International Journal of Production Research vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 935-950, 2019.

- X. Si, Y. Wang, and Z. Hu, "Remaining useful life estimation using deep learning models: A review," IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 10835-10847, 2020.

- W. Lin and K. Fang, "Data-driven predictive maintenance for IoT-enabled systems," International Journal of Prognostics and Health Management, vol. 9, pp. 60-72, 2018.

- M. Achouch, M. Dimitrova, K. Ziane, M. Adda, et al., "On Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0: Overview, Models, and Challenges," Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 16, p. 8081, 2022. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. [CrossRef]

- B. Hu, L. Sun, and R. Ma, "Machine learning for predictive maintenance in the cloud," Journal of Cloud Computing, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 112-124, 2022.

- X. Wang, "Improving machine reliability with AI-based predictive maintenance systems," Computers in Industry, vol. 114, pp. 103-114, 2020.

- R. Smith, "Cost-benefit analysis of predictive maintenance models for IT systems," Journal of Systems Engineering, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 200-210, 2017.

- Singh and D. Singh, "Combining deep learning and reinforcement learning for predictive maintenance scheduling," Applied Soft Computing, vol. 93, pp. 106-113, 2020.

- Zhang, "Neural networks for predictive maintenance in IT systems,"IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 515-528, 2021.

- Lee, "AI-based anomaly detection for predictive maintenance: A case study," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 136, pp. 90-102, 2020.

- E. Garcia, "Machine learning applications in predictive maintenance: A comprehensive review," Computers and Industrial Engineering, vol. 137, pp. 106-122, 2019.

- S. Park, "A review of predictive maintenance models for smart manufacturing," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 4443-4454, 2020.

- W. Yang, "Cost analysis of predictive maintenance models in cloud environments," Journal of Cloud Computing, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 320-334, 2019.

- D. Nguyen, "Fault detection and predictive maintenance in the aerospace industry," Journal of Aerospace Information Systems, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 123-139, 2019.

- R. Johnson and L. Xu, "Using deep learning for predictive maintenance in data centres," IEEE Transactions on Big Data, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 451-460, 2021.

- Davies, "Towards real-time predictive maintenance using IoT and AI," Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 113, pp. 307-318, 2021.

- C. Chen and L. Huang, "Predictive maintenance using machine learning and IIoT in industrial environments," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 5734-5745, 2020.

- Barakat and J. Martin, "AI-powered predictive maintenance in industrial IoT systems," Sensors, vol. 20, no. 22, pp. 6515-6530, 2020.

- J. Fletcher, "A hybrid approach to predictive maintenance using ML and rule-based systems," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 169, pp. 110746, 2020.

- B. Liu and M. Zhou, "Fault detection in rotating machinery using hybrid models," Journal of Vibration and Control, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 1287-1302, 2018.

- R. Justo-Silva, A. Ferreira, G. W. Flintsch, "Review on Machine Learning Techniques for Developing Pavement Performance Prediction Models," Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 5248, 2021.

- T. Ward, "Integrating real-time data with machine learning for predictive maintenance," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 155056-155070, 2019.

- V. Pandiyan, "Deep learning-based monitoring of laser powder bed fusion process on variable time-scales using heterogeneous sensing and operando X-ray radiography guidance," Additive Manufacturing, vol. 58,p. 103007, October 2022. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. [CrossRef]

- S. Cho, G. May, I. Tourkogiorgis, D. Kiritsis, et al., "A Hybrid Machine Learning Approach for Predictive Maintenance in Smart Factories of the Future," presented at the Conference Title or Book Series (if applicable), August 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).