Introduction

In the Amazon region, concrete structures are exposed to extreme weather conditions that compromise the integrity of the material from the early stages of setting. Temperatures above 40 °C and high relative humidity accelerate the surface evaporation of the mixing water, interrupting the cement hydration process and decreasing the strength and durability of the concrete. This problem is especially critical in self-built buildings, where the use of precarious materials and inadequate curing methods intensify the occurrence of premature micro-cracking and structural failure.

Concrete curing, understId as the controlled maintenance of temperature and humidity to promote hydration and the development of mechanical properties, has been addressed by traditional methods such as water spraying, the use of sealing membranes or steam curing [

1]. However, these methods have significant limitations in regions that are difficult to access or in extreme tropical climates, where curing efficiency is conditioned by uncontrolled environmental factors and lack of continuous technical supervision [

2,

3].

Currently, the convergence between automation, sensor technology and the Internet of Things (IoT) allows the development of intelligent systems capable of monitoring critical variables such as surface moisture, internal concrete temperature or incipient crack formation in real time [

4]. These solutions represent an opportunity to modernise the curing process by integrating embedded control algorithms that automatically act to maintain optimal hydration conditions [5-7].

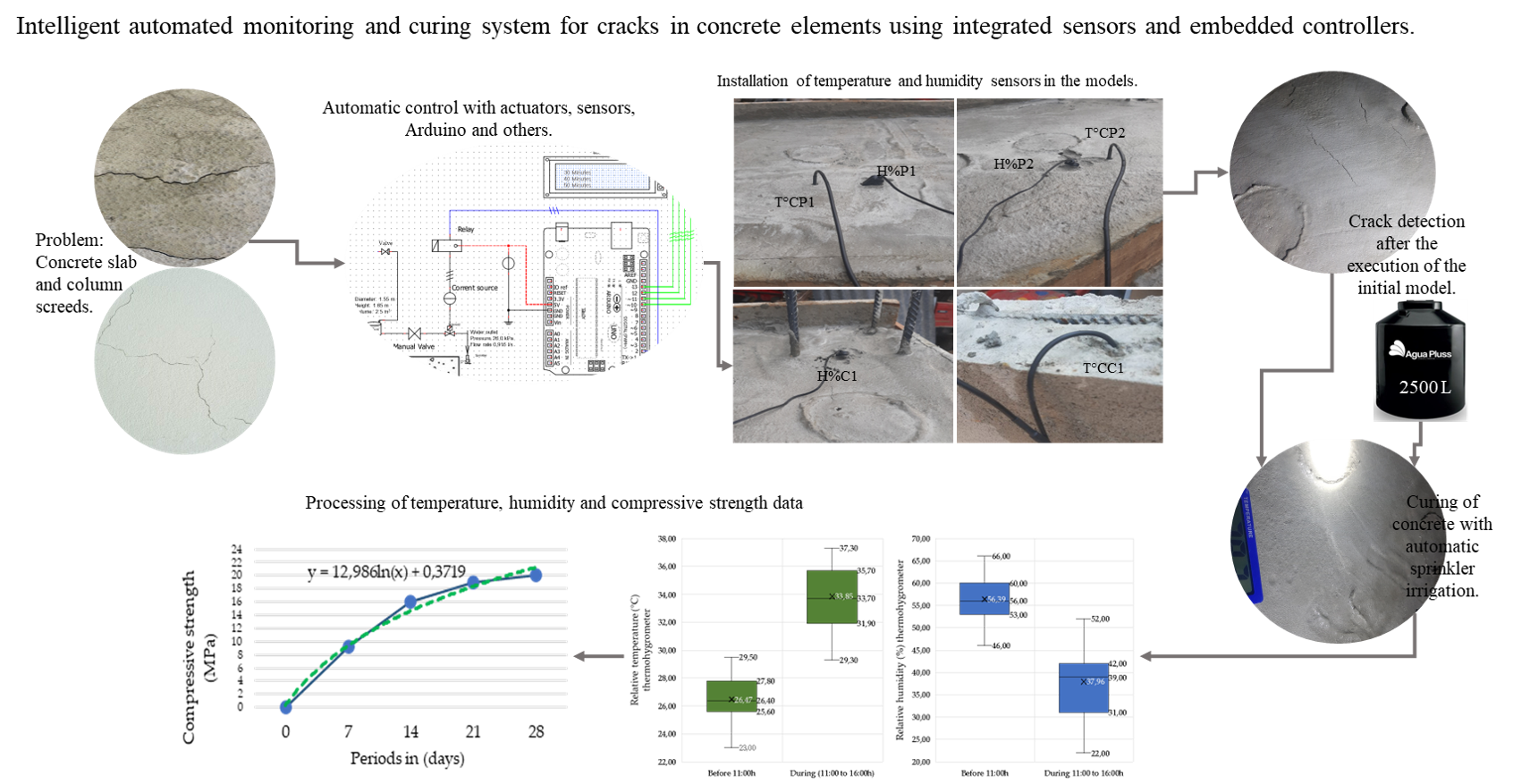

In this context, the present research proposes the design, development and validation of an intelligent system for monitoring and automated concrete curing, oriented to face extreme climatic conditions such as those of the Peruvian Amazon. The system integrates ultrasonic sensors, embedded controllers and actuators allowing early detection, characterisation and automated rehabilitation of cracks in structural elements. Through autonomous algorithms, the curing process is optimised from its initial stages, minimising premature cracking and improving concrete durability. Unlike previous approaches, this study emphasises the system's real-field adaptability, its operational robustness and its potential to prevent structural deterioration in vulnerable and hard-to-reach environments.

In the state of the art. A systematic and critical review of the existing scientific literature on the development of intelligent systems for automated concrete monitoring and curing, with emphasis on crack detection and rehabilitation in structural elements, is presented. This review addresses the use of integrated sensors and embedded controllers, analysing their evolution and application in the context of advanced technologies for the optimisation of curing.

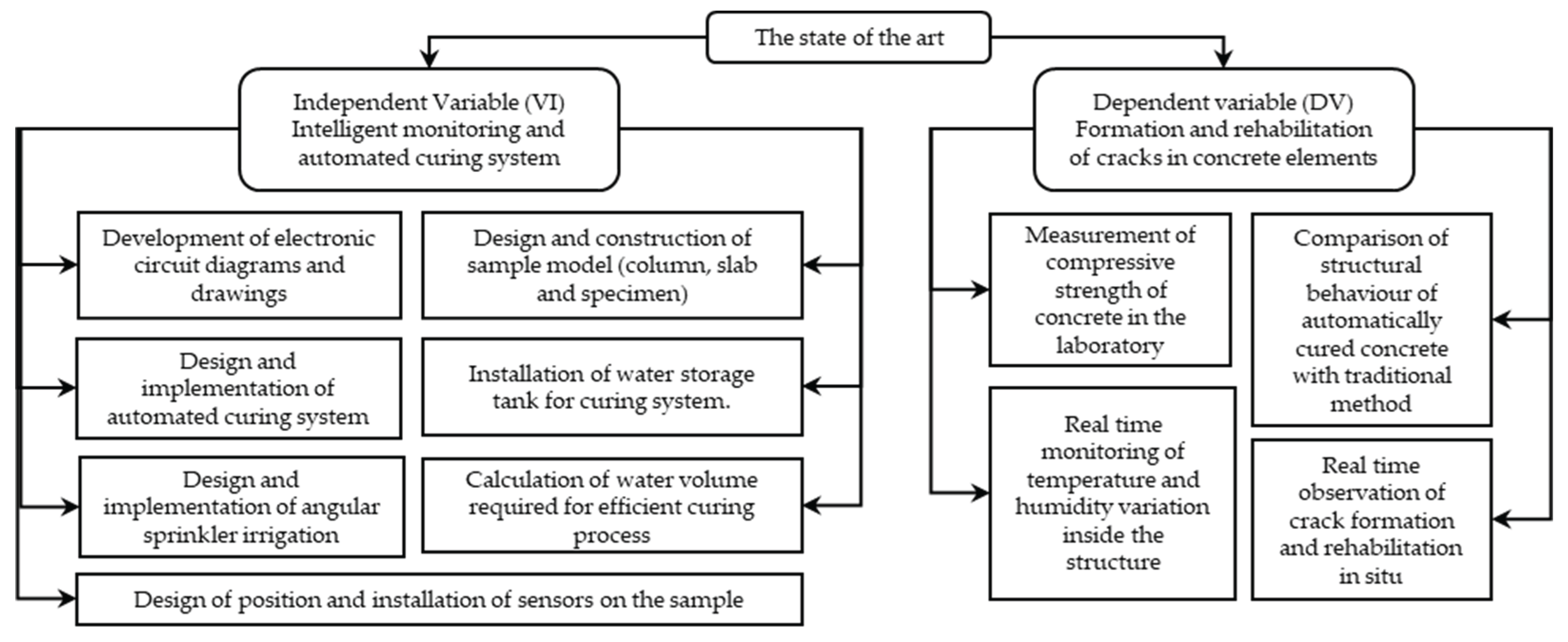

Figure 1 summarises the main approaches and advances in this field:

The structural integrity of concrete under high temperature and humidity conditions has been the subject of several studies. For example, [

8] showed that these factors significantly alter the porosity and strength of the ECC-concrete interface, with direct implications on durability and post-fire rehabilitation processes. Likewise, [

9] showed that elevated temperatures decrease compressive strength, while higher relative humidity favours durability and improves the mechanical properties of the material. In relation to traditional curing methods, researches such as [

10], [

11], highlight the influence of moist curing and temperature on the strength and permeability of concrete, underlining the need for precise control to achieve optimum mechanical properties. Complementarily, [

12] analysed the effects of steam curing regimes and surface sealing methods on microstructure and impermeability, especially under severe thermal conditions. Faced with these challenges, emerging technologies have started to address the intelligent monitoring of the curing process. In this regard, [

13] proposed a smart system based on optical sensors that allows real-time monitoring of critical variables such as humidity, temperature and deformation, facilitating early detection of anomalies. Similarly, [

14] developed wireless embedded sensors for continuous monitoring of moisture and temperature to improve quality control during curing. In the field of curing automation and water management, [

15] designed a system that automatically regulates watering based on real-time data, optimising early strength and reducing both water consumption and cracking. Finally, [

16] presented an automatic moisture monitoring system aimed at minimising water wastage and preventing cracking, incorporating remote strength monitoring capabilities. This background evidences the need for intelligent, autonomous and adaptive solutions, especially in climatically demanding contexts such as the Amazon, where extreme conditions compromise the effectiveness of traditional concrete curing and monitoring methods.

1.1 Intelligent Monitoring and Automated Curing System

Using sensors, Arduino and actuators, concrete curing can be monitored in real time, comparing its strength (f'c) in structural elements. This technological alternative overcomes costly or limited traditional methods, improving quality control in common constructions and reducing possible economic losses in the region. Furthermore, according to ASTM F2170, sensors can be positioned to collect, analyse and manage real-time data through an IoT gateway [

19]. Through numerical optimisation, optimal levels of cement replacement with nanoparticles and temperatures, between 25 °C and 800 °C, applied for 1 and 2 hours, were determined to maximise the compressive strength of the concrete [

20].

Monitoring the concrete curing process in slabs and columns consists of continuously observing, measuring and analysing its key variables to ensure that it takes place efficiently, effectively (without cracking) and within the established parameters. In addition, it allows the identification of bottlenecks, detection of anomalies in real time and collection of information for trend analysis, which facilitates process optimisation [

21], [

22]. The electrical conductivity of concrete is sensitive to mineral reactions and reflects hydration kinetics. It shows linear correlations with penetration resistance, ultrasonic pulse velocity, forming factor and maturity [

23]. Ultrasonic sensors detect invisible cracks in buildings and alert authorities via SMS, providing their location through GSM and GPS modules. They also monitor internal cracks in concrete cubes and cylinders using sensing technology [

24].

Continuous monitoring of embedded wireless sensors demonstrates reliability in the face of temperature fluctuations, detecting unwanted variations in concrete curing in real time. This improves quality control, minimises shrinkage and ensures the integrity of the finish [

14]. Acoustic emission (AE) is a non-destructive and highly sensitive technique that records elastic waves propagating in the material, proving effective for monitoring complex processes in the early stages of concrete curing [

25].

IoT facilitates structural health monitoring (SHM) in civil engineering, including early assessment of concrete strength and control of water wastage during continuous curing, thus optimising efficiency and sustainability [

26].

Estimating the compressive strength of concrete at an early age is crucial for formwork removal and construction progress, especially in adverse weather conditions. Non-destructive methods, including IoT techniques, have been proposed to determine it more accurately [

27].

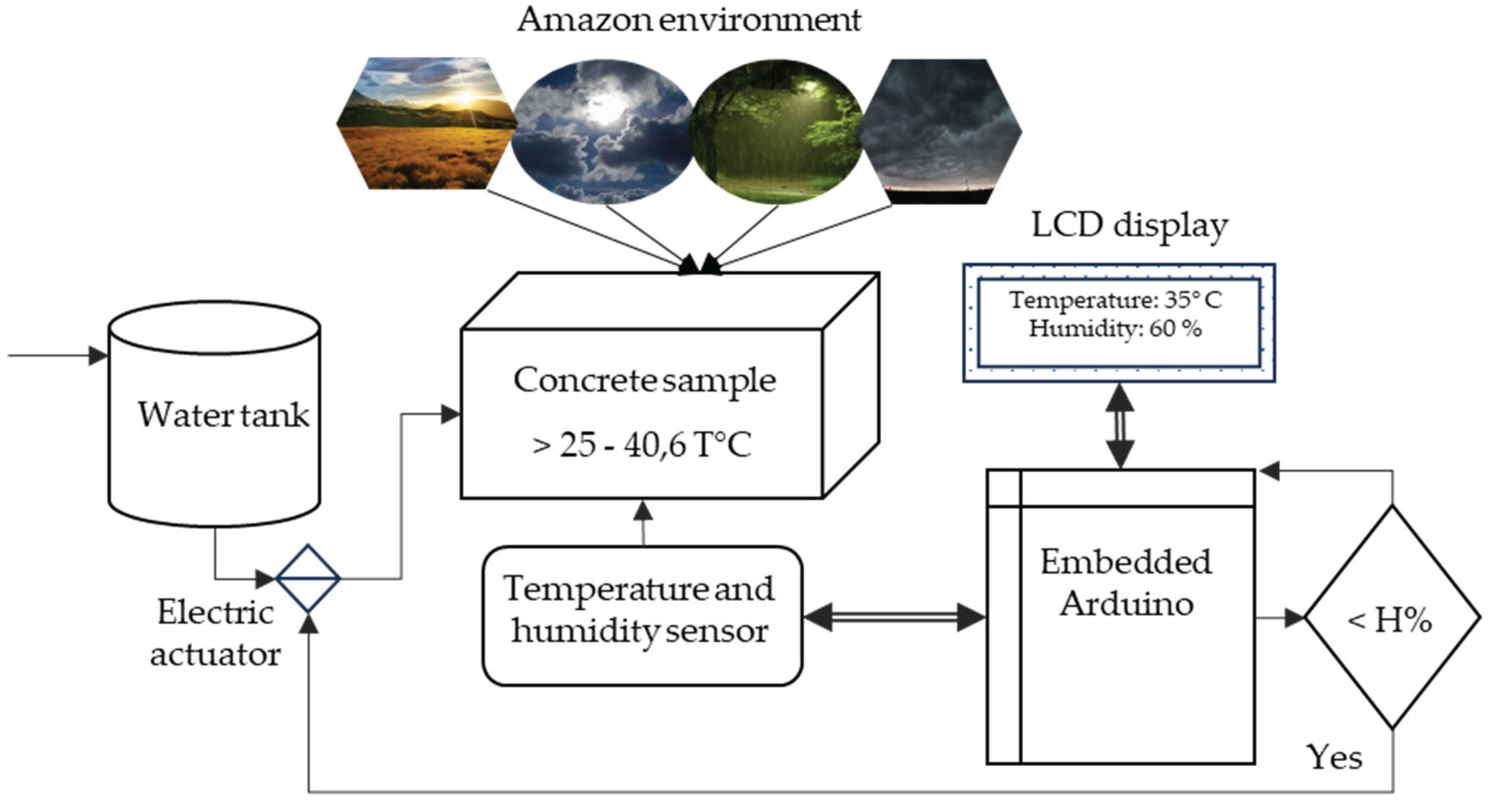

As shown in

Figure 2 and [

28] in their article discusses smart drip and sprinkler irrigation systems using IoT, addressing their different types and challenges. They also review smart irrigation technologies, focusing on optimising drip and sprinkler methods.

[

29] performed guided ultrasonic wave (GUW) tests on reinforcements and RCs with different degrees of corrosion, verified with a theoretical model. That is, the higher the thickness covered, the higher the modal order increases, and delays the occurrence of cracks. However, [

30] used a digital image correlation (DIC) system with Baumer 12.3 Mpx cameras and a Dantec Dynamics Q400 system to calculate the deformation field. They also measured elastic waves with PZT sensors and crack openings, observed changes in the shape and amplitude of the recorded signals that signify crack growth.

Likewise, [

7], [

31] mentioned that they measured and analysed the amount and state of spraying of the curing compound with flow meters and image sensors, providing real-time data to workers and storing it in the IoT cloud to create a database.

Microcrack homogenisation technology reduces reflection cracking in old concrete pavements. Using X-ray tomography, the mesostructure of cores was analysed, classifying cracks into microscopic and macroscopic cracks, subdivided into type I-III microcracks and type I-IV cracks [

32].

In recent decades, electromechanical impedance (EMI, which analyses electromagnetic interference) and electromagnetic wave propagation techniques, both based on piezoelectricity, have been incorporated to monitor the properties of concrete during curing in the laboratory. These techniques have proven to be effective in the control and analysis of the concrete curing process [

33]. The effect of curing on concrete strength elements has been significantly evaluated by using piezoelectric patches (PZT) as smart material devices in electromechanical impedance studies [

34].

In their study [

35] they used image recognition technology to identify distinctive textural and micromorphological features in internally cured concrete samples.

To improve concrete curing, technologies that eliminate human intervention and better control environmental conditions have been used. However, the potential of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies has not yet been fully explored [

36]. Meanwhile, [

37] analysed a concrete curing control system based on IoT and sensor technologies to regulate moisture content, comparing its effectiveness with conventional curing methods through in-situ tests.

The development of sustainable concrete technologies is urgent and requires a thorough understanding of the mechanisms driving cement hydration reactions. Molecular simulations can provide this understanding, as these processes rely on atomic-scale interactions [

38].

Sensors as an electronic device composed of a series of components, but controlled by a microcontroller called ATMEGA328, which can process data and perform various tasks such as: moving a motor, detecting the presence of an object, measuring the time between two events, turning a light on or off, etc. [

39] propose a dielectric resonator (DR) sensor with a small cavity for sorting glycerine solutions. The results show that low-cost electronics combined with machine learning match the performance of commercial instrumentation.

An Arduino board can connect to the internet which is based on the Ethernet chip that supports multiple simultaneous socket connections.

An Arduino board is an electronic device composed of a microcontroller called ATME-GA328. The Arduino code manages data collection, LCD display, relay control and fan speed, while the Node MCU connects to Wi-Fi, formats and transmits data to the web server, ensuring security [

40]. The study uses an Arduino board and an assembler program to repel mosquitoes using piezoelectric disks, LEDs and ultrasound, protecting humans and the environment. It includes an LCD monitor for visualisation.

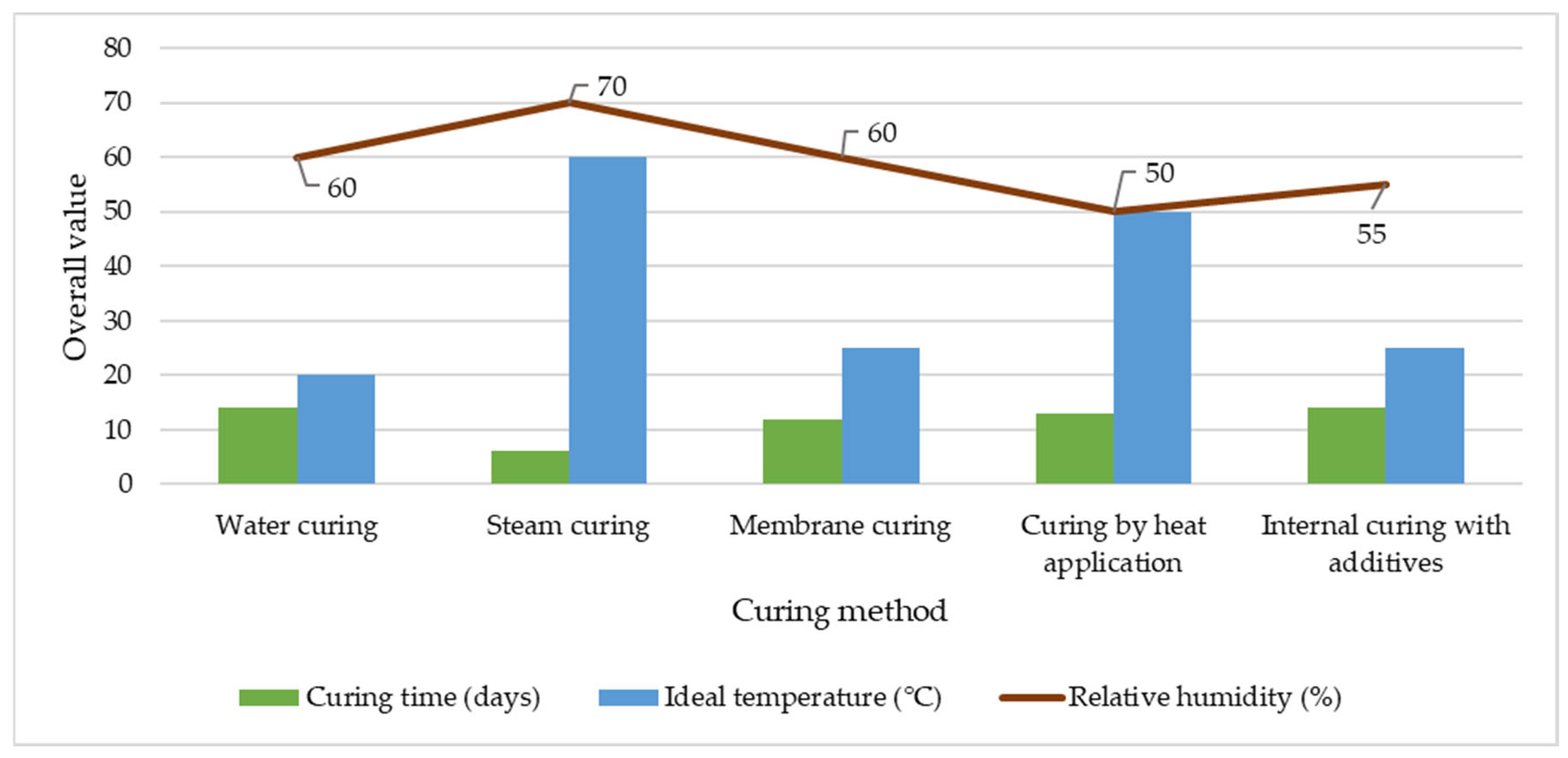

Formation and rehabilitation of cracks in concrete elements

In this context, real-time control of the curing method helps to prevent structural cracks in the early age of concrete. The strength and performance of concrete against high temperatures is highly dependent on its composition and type [

41], i.e. the main concrete curing methods are detailed below:

Water curing (immersion, spray, wet blankets).

Steam curing (high and low pressure).

Curing with sealing membranes (curing liquids, plastics, waterprIf paper).

Curing by application of heat (infrared radiation, thermal blankets).

Internal curing (use of admixtures or water absorbing aggregates).

Inadequate curing of concrete reduces its quality and negatively affects its durability due to excessive evaporation of water, which can lead to deformation and shrinkage cracks [

42].

Figure 3 shows that steam curing is faster, but requires higher temperature and humidity. The other methods take longer, but require less demanding environmental conditions, i.e. the concrete curing process is essential in the manufacture of quality structures [

43].

Concrete curing means artificially controlling specific temperature and humidity conditions to ensure normal hardening and strength growth of freshly cast concrete under the cement hydration reaction [

48]. This process directly influences the strength, impermeability and durability of reinforced concrete elements, allows continuous hydration of cement and, consequently, a continuous increase in strength, once curing stops, so does the increase in concrete strength. Adequate humidity conditions are critical because cement hydration virtually ceases when the relative humidity within the capillaries drops below 80% [

49]. Also, steam-heating curing is commonly used in precast elements and consists of applying hot water vapour at temperatures ranging from 40 °C to 100 °C for a specified time [

50]. This method accelerates the strength development of concrete in its early stages, achieving increases of up to 193% in the first day. This allows faster formwork removal and improves production efficiency. However, this method has potential disadvantages, such as uneven hydration distribution, decreased strength and durability, increased porosity and brittleness [

51]. The standard method of concrete curing is based on the use of water, which leads to a high level of water wastage [

52], a standard curing time of 14 days is essential to ensure the resistance of concrete with high mineral admixture content to chloride ion penetration [

53]. Curing concrete at extreme temperatures significantly affects the interior microstructure of the concrete [

54]. The temperature during curing and post-curing affected the glass transition of the epoxy significantly, and depending on whether the temperature above 20 °C was below its glass transition point [

55].

The optimum curing period of concrete varies depending on several factors, such as the mix dosage, the required strength, the dimensions and geometry of the element, the climatic conditions of the environment and the demands to which it will be exposed in the future.

Curing with moisture retention and moisture-heat retention reduces the shrinkage strain of concrete by 30.7% and 11.3%, respectively, compared to moisture-heat exchange at 125 days [

56]. The combination of a setting accelerator and a hardening accelerator can significantly improve the compressive strength of early-age concrete under both normal curing and heat curing conditions [

57]. The digital image processing technique measures crack widths and the thermocouple records the concrete temperature. All curing methods restrict micro-cracks and plastic shrinkage cracks, but the use of recycled tyre steel fibre (RTSFC40) is the most effective in eliminating them at the surface [

58]. Moisture variations in concrete under various environmental conditions and curing methods can be quantitatively analysed [

59].

The moisture status of the aggregates significantly influenced the strength of concrete made with oven-dried (OD) and surface-saturated (SSD) aggregates at early ages (3 and 7 days) [

60].

Water curing techniques for concrete include immersion, where the concrete is immersed in water, which is ideal for specimens that are part of the concrete; spraying, which keeps the surface wet by continuous spraying; and the use of wet blankets, where sacks or fabrics retain moisture for uniform curing. In this study, spray irrigation was applied for 23 days [

61], [

62], [

63].

Concrete cracking is a common problem in many buildings around the world. Companies strive to develop products that mitigate this phenomenon, prioritising the safety of families and the structural integrity of concrete over time [

64].

Finite element simulation provides key results such as cracking pattern, vertical deflection, strain distribution, ductility, load-drift relationship and cracking, creep and ultimate load capacities [

65].

The hybrid reinforced (steel bars and fibres) technology is a competitive alternative for column-supported flat slabs. It offers high load-bearing capacity, toughness, ductility and sustainability, while maintaining structural integrity under high levels of stress [

66].

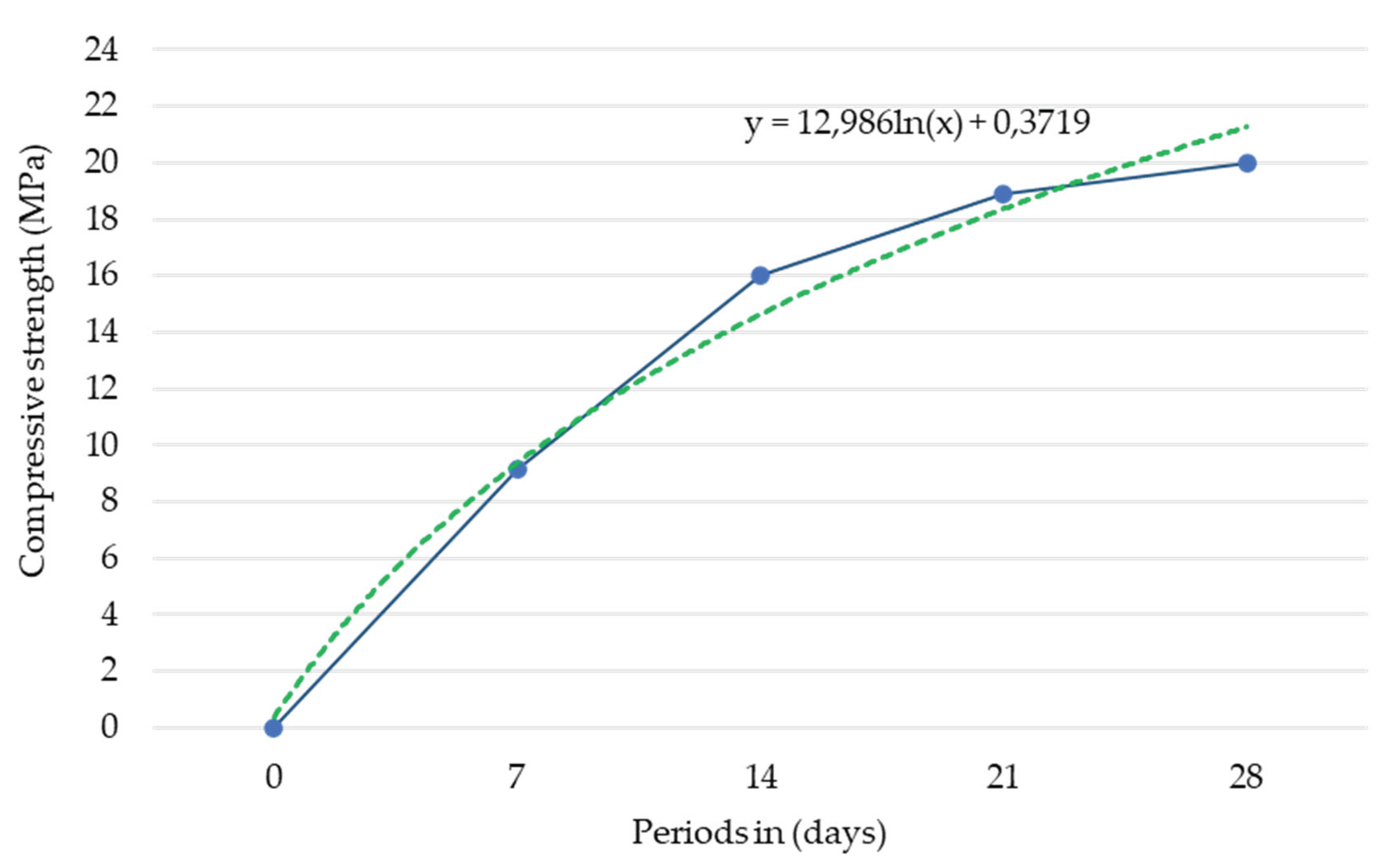

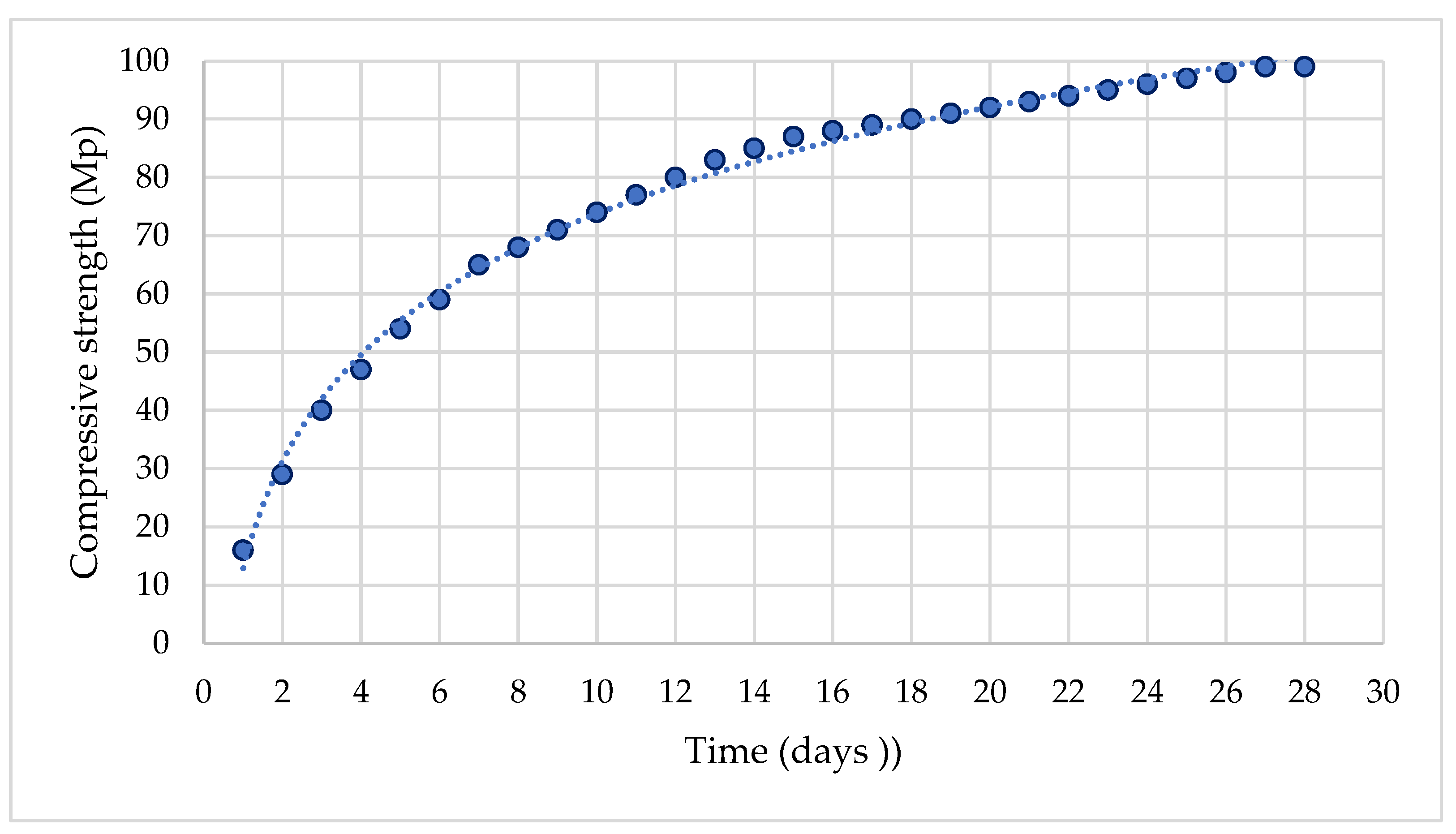

By knowing the compressive strength of concrete, it is possible to optimise the dosages and adjust its properties according to the specific requirements of the construction site, thus improving its performance and durability,

Figure 4 visualises the trend of the standard compressive strength.

Drying shrinkage of concrete, after hardening, causes cracks that affect its appearance, reduce its strength and durability, and increase its permeability, facilitating the entry of aggressive agents [

71], the cause of cracks in concrete is estimated by analysing patterns and locations, but this method depends on expert knowledge, which can lead to inconsistent or inaccurate diagnoses due to variability in experience [

72].

The arid climate causes shrinkage cracking in concrete, especially at early ages, accelerating in direct exposures. However, with adjuvants, cracks decreased by 50% in length and 66% in width, reducing to 40% and 50% with traditional curing [

73].

Equations used in the study are shown below: The temperature of the concrete at the time of installation in cold climates can delay the curing of the adhesive, negatively affecting its adhesion. According to [

74], the evaporation rate is calculated using the following formula:

Where:

E is the evaporation rate (kg/m2 /h).

Tc is the concrete temperature (°C).

Ta is the relative temperature (° C).

r is the relative humidity (%).

V is the wind speed (km/h).

where

P = pressure in pascals (Pa),

ρ = density of water (1000 kg/ m^3,

g = gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s^2),

h1 = height of water in tank (1.65 m),

h2 = additional height of tank above ground 1.00 m,

V = outflow velocity of liquid in the Torricelli equation.

Where:

V or

Vt: Volume of the tank (m³),

r: Required water height (m),

A= area to irrigate (m2),

t: irrigation time (s), tank height (ht),

g: gravity (9.81 m/s2),

Q is the required flow rate (L/s). And also:

h is the height in meters,

ρ is the density of water equivalent to (1000 kg/m³) and

g is the gravity (9.8 m/s²). For the calculation of the compressive strength of concrete the formula was used:

where

P represents the maximum axial load applied (kg) and

A the cross-sectional area of the cylinder (cm²). The data acquisition and recording was trouble-free, partly due to the adequate location of the physical model and the effectiveness of the integrated monitoring system.

In order to linearise non-linear relationships and facilitate their statistical or graphical analysis, we used.

Where y is the dependent variable. x is the independent variable. k is the multiplicative constant (log intercept). n is the exponent (log slope). Likewise, the equation of Clausius Clapeyron's Law is:

Methods

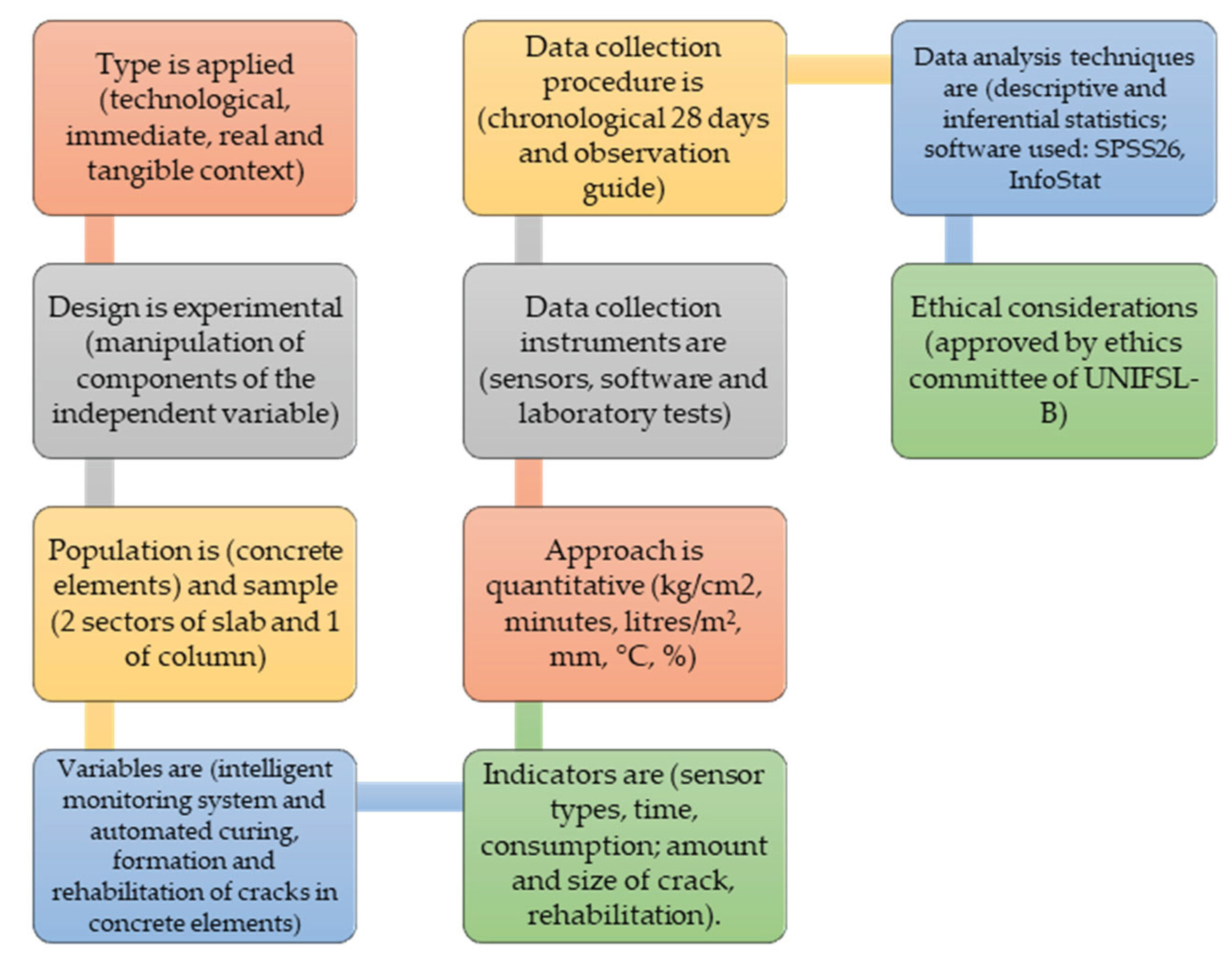

This study was designed as an experimental and quantitative applied research [

75], aimed at developing and validating an intelligent system for automated monitoring and curing of cracks in concrete elements. It was structured in the following phases:

Experimental design: the independent variable [

76]; was intentionally manipulated; furthermore, following the guidelines proposed by [

77], an intelligent monitoring and curing system was implemented, with the aim of evaluating its effect on the dependent variable, i.e., the formation and rehabilitation of cracks in concrete elements.

Sample selection: A parametric cluster sampling [

78], was applied, in this context, slabs, columns and specimens were defined as experimental units, which were designed to replicate real curing conditions [

79].

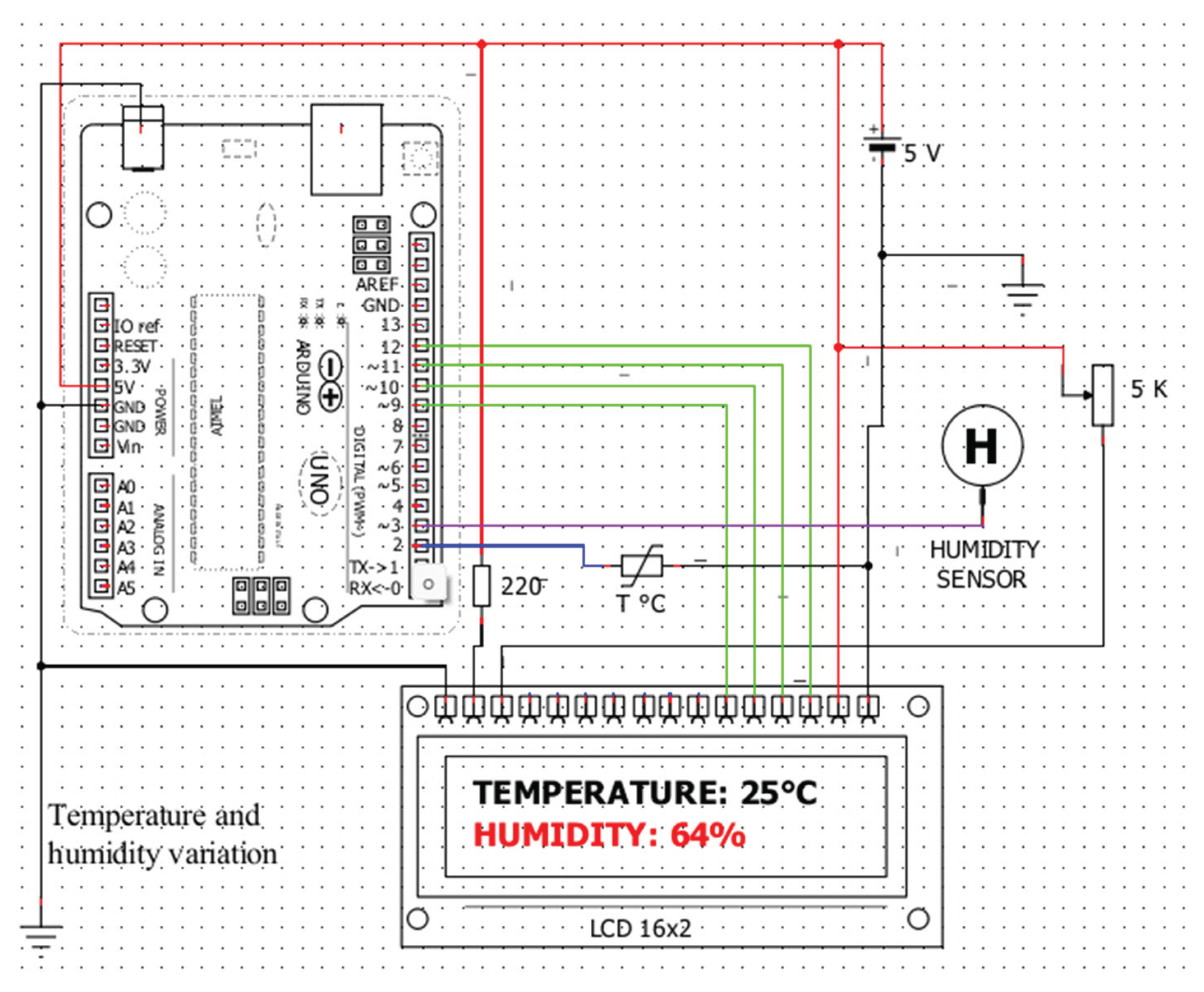

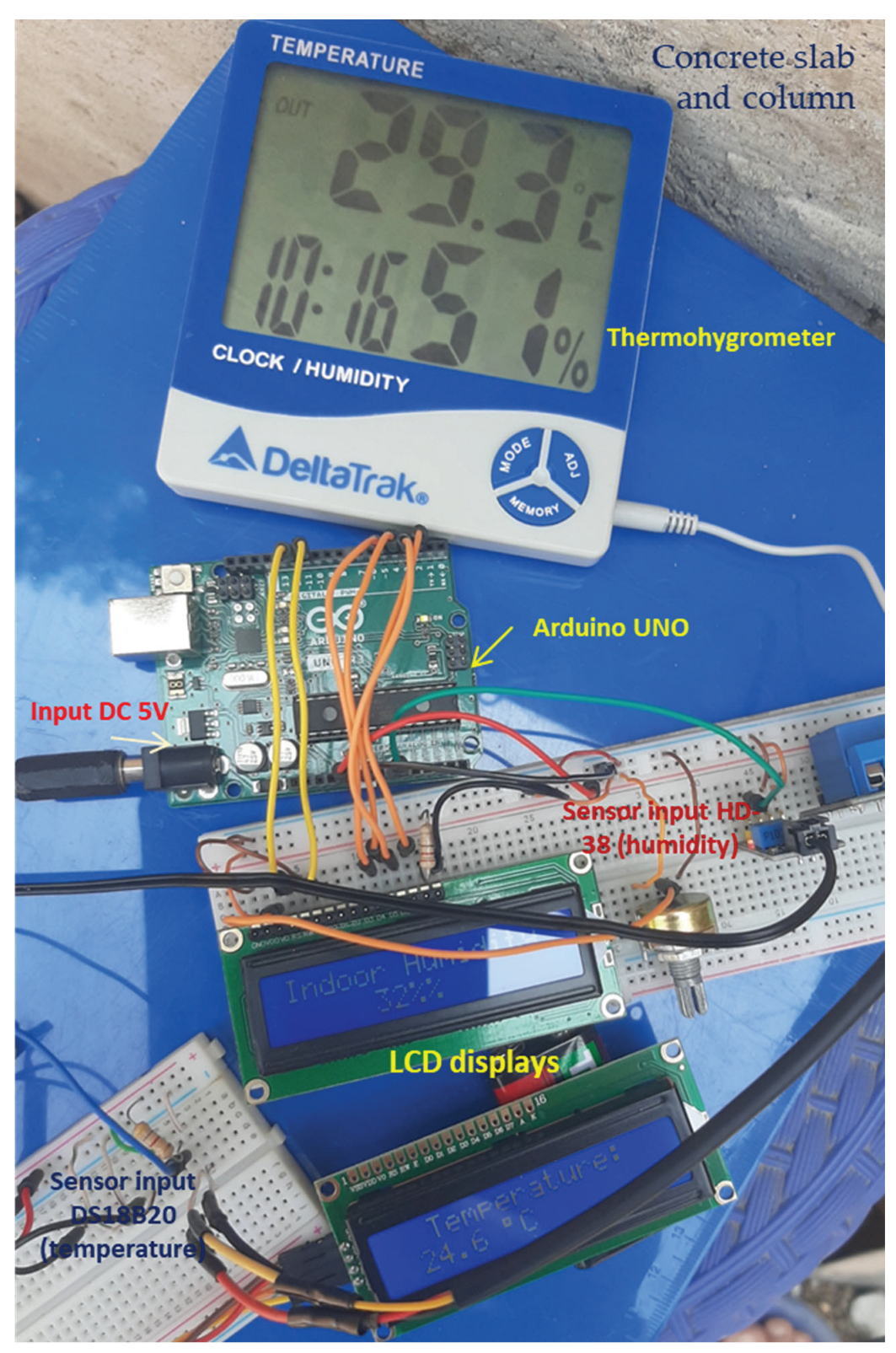

System implementation: The integration of temperature (DS18B20) and humidity (HD-38) sensors, actuators such as sprinklers and solenoid valves, microcontrollers (Arduino), as well as an observation guide, was carried out in order to allow real-time control and monitoring.

Preliminary validation: An initial prototype was developed in both software and hardware, in order to identify possible failures and make the necessary design adjustments, as described by [

80].

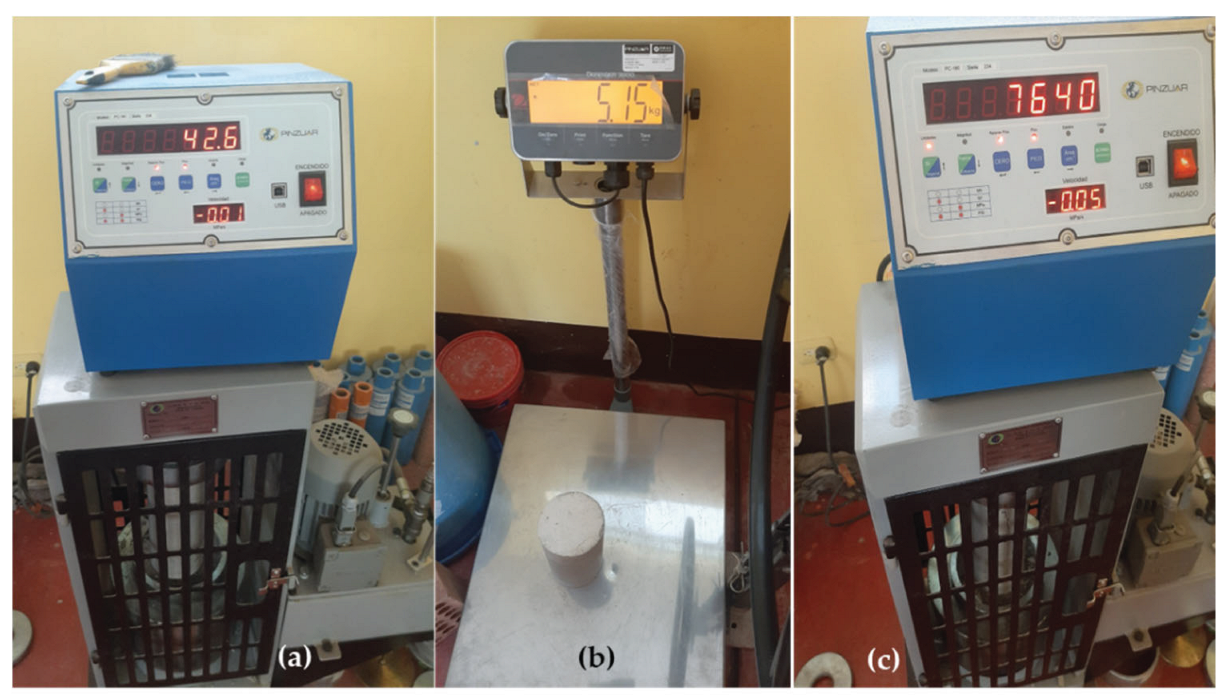

Laboratory and field tests: Compressive strength (f'c) tests were performed using a PINZULAR hydraulic press; in parallel, continuous monitoring of environmental parameters and analysis of artificially induced cracks were carried out in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented system.

Data analysis: Finally, SPSS, InfoStat and Tableau software were used to carry out statistical analyses, both descriptive (mean, standard deviation, 95 % confidence intervals) and inferential, including normality tests (Shapiro-Wilk), analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson correlation [

81].

2.1. Variables and Indicators

The variables and indicators defined made it possible to establish precisely what is measured and how it is measured, in order to evaluate the impact of the automated system on the concrete crack curing and rehabilitation process.

(a) Automated curing system: This variable was evaluated through various technological indicators, including temperature and humidity sensors, monitoring frequency (every 30, 45, 60 minutes, and in ranges of 1-2, 3-5, and 6-8 hours), system response time (less than 5 seconds), total curing duration (28 days), water consumption expressed in litres per square metre (L/m²), level of automation, and embedded control logic. Together, these parameters made it possible to quantify the efficiency and reactivity of the system in real time.

(b) Crack formation and rehabilitation: For this variable, structural and mechanical indicators were considered, such as compressive strength (measured in kg/cm²), crack formation time (in minutes), as well as average crack length and width (expressed in centimetres and millimetres, respectively). In addition, the percentage reduction of cracks after the system intervention was measured, as well as the rehabilitation and propagation rate, thus allowing to evaluate the corrective effectiveness of the developed prototype.

2.2. Instruments and Materials

The implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the automated system required the integrated use of electronic equipment, specialised sensors, simulation platforms and construction materials, selected on the basis of their compatibility, accuracy and reliability.

a) Instruments: Electronic measuring devices such as digital thermohygrometers, voltmeters and ammeters were used. Also, temperature (DS18B20) and humidity (HD-38) sensors, Arduino UNO microcontrollers, adjustable power supplies, RLC devices and LCD screens were incorporated, all of them oriented to guarantee real-time monitoring and autonomous activation of the system.

b) Software: The design of the moulds was carried out in AutoCAD, while the simulation of electrical and electronic circuits was executed using Proteus, Multisim and QElectroTech software. The programming of the embedded system was developed on the Arduino IDE platform, thus facilitating the integration between hardware and control logic.

c) Materials: In terms of construction materials, cement, gravel and water were used, together with moulds designed for columns, slabs and specimens. WId was also used for the structure of the moulds, replicating real curing conditions.

It should be noted that all the instruments used were previously calibrated before their experimental use, and the data obtained were validated with standard tables, thus ensuring the reliability and consistency of the measurements.

2.3.. Procedure

The methodological procedure was structured in an orderly sequence of stages that allowed the implementation, monitoring and validation of the automated system, from the initial sample preparation to the analysis of quantitative results.

Sample preparation: First, the manufacture of moulds with standardised dimensions was carried out, in accordance with the plans drawn up in AutoCAD. Subsequently, the concrete was poured, ensuring the homogeneity of the mixture and uniformity between the experimental units.

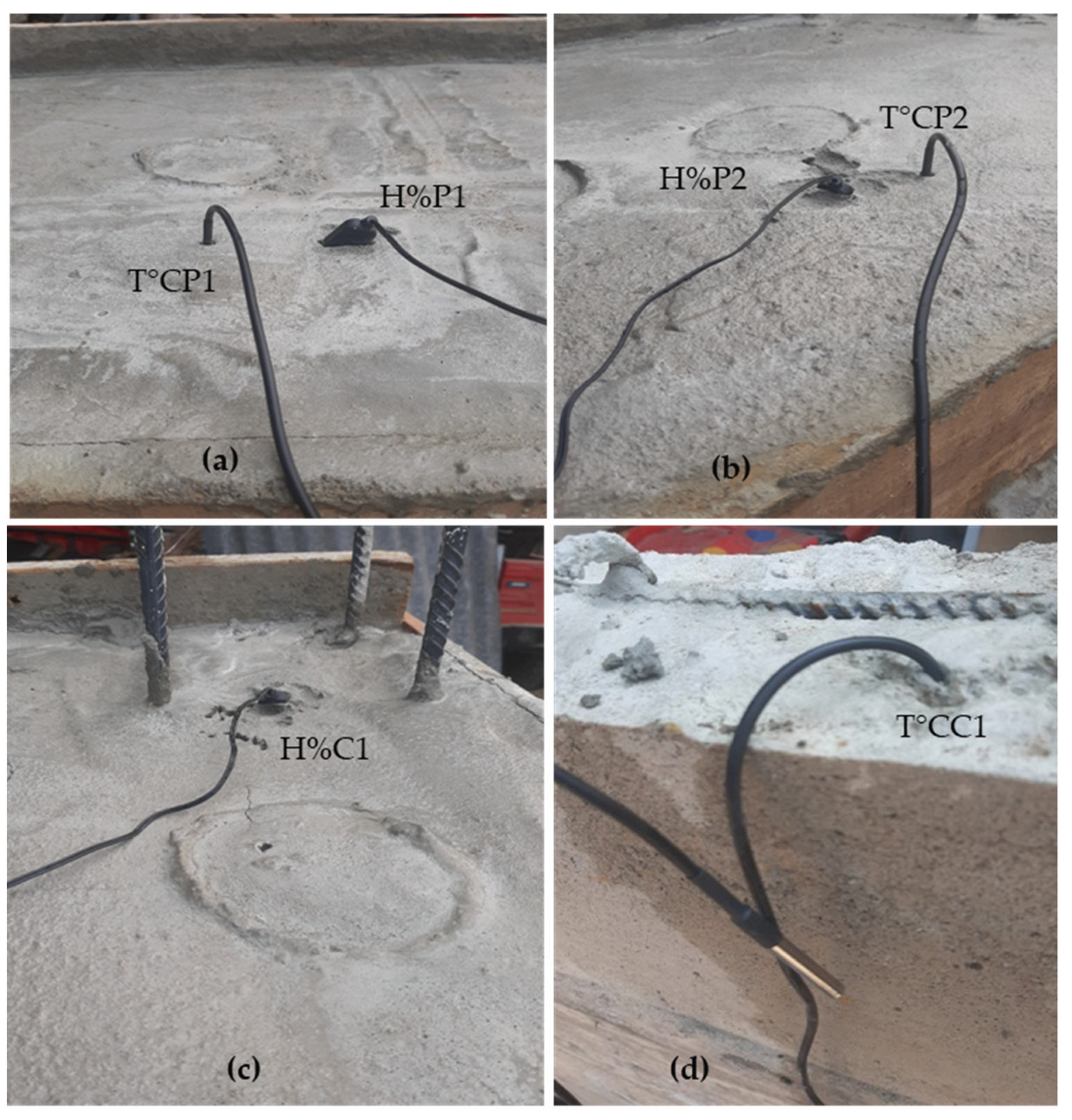

Sensor installation: Once the initial concrete had set, sensors were installed in strategic locations within the moulds. This arrangement optimised the accurate capture of thermal and moisture variables, both on the surface and inside the concrete.

Monitoring: Next, an automated data acquisition system was implemented using Arduino microcontrollers, with daily records including date, time, weather conditions and environmental parameters, both external and internal. This data was displayed in real time on an LCD screen, which facilitated the continuous monitoring of the system.

Curing activation: Based on the collected data, the embedded algorithm compared the obtained readings with previously defined thresholds. When the detected conditions deviated from the optimal ranges, sprinklers or solenoid valves were automatically activated. This action was executed considering the evolution of time in minutes, thus ensuring adequate environmental conditions during the whole curing process.

Strength measurement: After 28 days of curing, the compressive strength of the test specimens was evaluated by means of mechanical tests, following the guidelines established by the corresponding technical standard.

Analysis: Finally, the data obtained were processed using SPSS, InfoStat and Tableau software. This analysis allowed to evaluate the effectiveness of the automated system and to contrast the empirical results with the theoretical values reported in the scientific literatura [

82], [

83], [

84].

2.4. Ethics and Methodological Quality

This research was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles and standards established in research, development and innovation (R&D&I) processes, as indicated by [

85] and [

86]. In this sense, the transparency, reproducibility and traceability of the technical and scientific procedures applied were guaranteed at all times.

Likewise, a methodological design with rigorous control of variables was used, which allowed us to achieve high internal and external validity, minimising experimental biases and maximising the reliability of the findings. Each of the experimental phases was executed under strict criteria of calibration and data validation, thus ensuring the integrity of the information collected and its applicability in real contexts.

Finally,

Figure 5 presents a synthetic scheme that summarises the methodological procedure implemented, highlighting the critical phases of design, execution, monitoring, validation and analysis.

This figure summarises the key phases of the research: from experimental design and sample selection, to system implementation, preliminary validation, laboratory and field testing, data analysis, and ethical and methodological quality criteria. It highlights the technological integration, the operational sequence and the evidence-based approach aimed at guaranteeing the reliability, replicability and applicability of the system in real construction contexts.

Results

3.1. Characterisation of Soil Conditions and Experimental Curing Model

The experiment was carried out on a site located at the geographical cIrdinates UTM 17M 0772723 / 9376835, at an altitude of 432 m asl. The selection of this site responded to technical criteria related to the influence of altitude and local geography on environmental parameters such as atmospheric pressure, temperature and relative humidity, variables that directly affect the behaviour of the concrete during curing, as well as the operational accuracy of the sensors and measuring devices under field conditions.

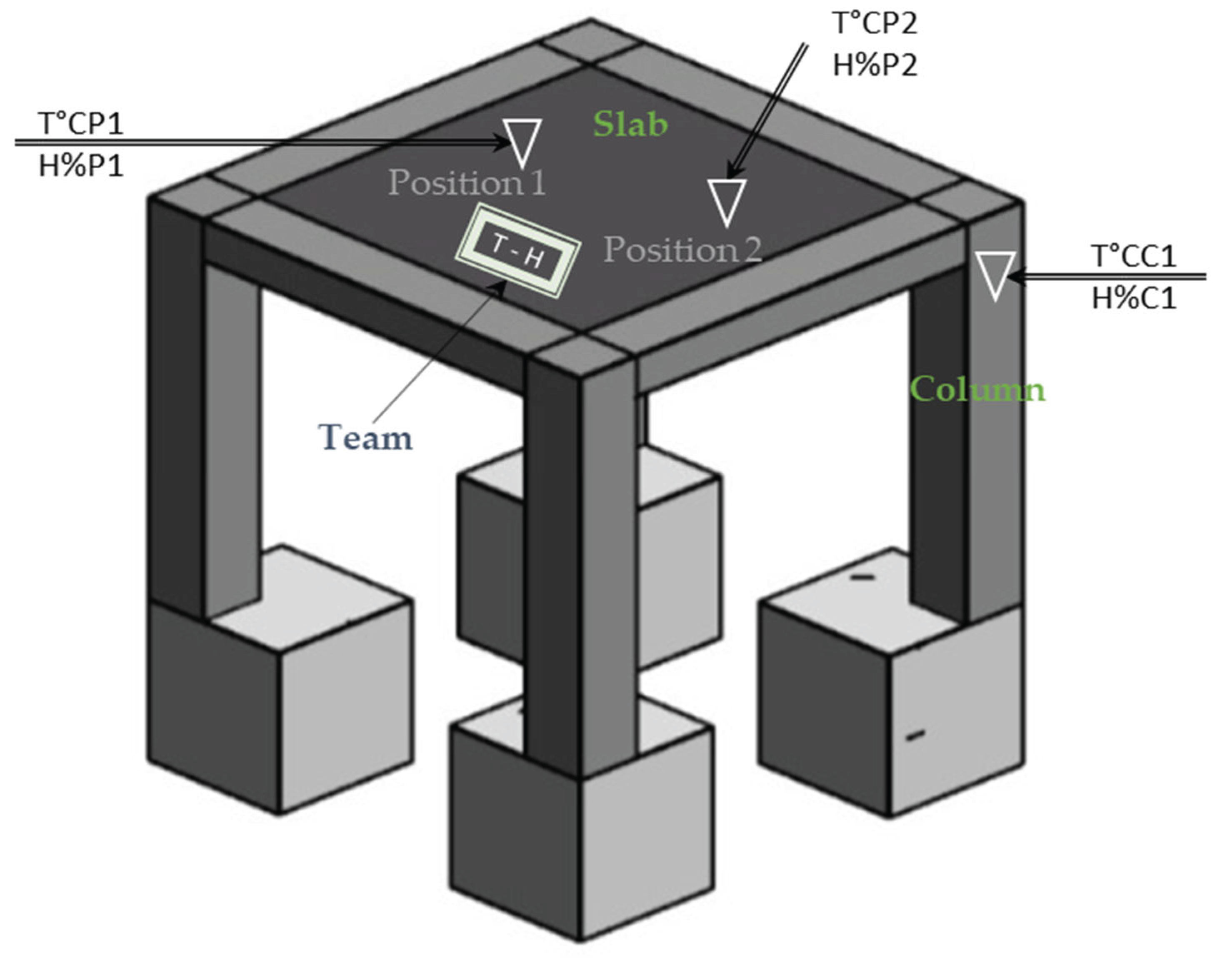

Figure 6 shows a three-dimensional representation of the experimental structural model, based on a frame-type configuration with top slab and vertical columns. The diagram shows the installation positions of the temperature (T°) and relative humidity (H%) sensors, both on the surface and inside the concrete. The sensors were placed in two key positions on the slab: Position 1 (P1) and Position 2 (P2), designated as T°CP1 / H%P1 and T°CP2 / H%P2, respectively. In addition, variables were monitored in one of the vertical columns, recorded as T°CC1 / H%C1.

Figure 6 also identifies the main structural elements of the model - slab and columns - and shows the location of the digital thermo-hygrometer (T-H), in charge of recording in real time the environmental variables, complementing the information acquired by the embedded sensors. This arrangement allowed for robust and comparative data collection, both on the surface and inside the concrete, throughout the curing process.

In this context, the strategic installation of sensors (temperature and humidity) was addressed as a critical aspect of monitoring. As evidenced in

Figure 7 c, the sensors were placed at representative points of the concrete volume, considering the heterogeneity of the material. Factors such as depth, distance between sensors and their location (centre or corners of the slab) were found to have a direct impact on the accuracy of the recorded data, which reaffirms the need for rigorous technical criteria for the correct placement of measurement devices.

3.1. Evaluation of Mechanical Behaviour by Means of Compression Tests

The context allowed for a technically rigorous evaluation of the structural properties and mechanical behaviour of the concrete elements used as experimental samples, specifically columns, slabs and cylindrical specimens. A solid slab was designed considering structural engineering criteria and current regulations, using AutoCAD as a digital modelling tIl. The structural design included a 2.0 × 2.0 m slab with a thickness of 0.2 m, columns of 0.25 × 0.25 m with a height of 1.5 m and fItings of 0.6 m depth, as illustrated in

Figure 8. A 1:2:3.5 mix dosage (cement: sand: gravel) was used for the construction of the model. In parallel, cylindrical specimens were produced under homogeneous mixing and curing conditions with respect to the slabs, with an average weight of 5.15 kg, a height of 30 cm, a diameter of 10.15 cm and a cross-sectional area of 0.0081 m².

The specimens were subjected to axial compression tests in the university laboratory using a calibrated hydraulic press. Experimental results indicated breaking loads of 74 kN at 7 days, 130 kN at 14 days and 153 kN at 21 days of curing. Applying the standard equation for the calculation of compressive strength (Equation 6), values of 9.13 MPa, 16.03 MPa and 18.87 MPa, respectively, were obtained. These results reflect a significant progression in the strength gain of the concrete, validating the quality of the mix and the performance of the applied curing.

These values are within the normative ranges for the mix used, presenting a progression coherent with the expected development of the concrete. The graphical analysis showed a logarithmic trend in the increase in strength, as shown in

Figure 9. This behaviour validates both the quality of the curing and the effectiveness of the real-time monitoring system. Additionally, the proposed mathematical adjustment model (Equation 7) demonstrated a high predictive capacity of the mechanical evolution of the concrete, strengthening the evidence on the usefulness of the automated system.

In summary, the results confirm that curing managed by embedded technology and continuous monitoring not only ensures optimal hardening conditions, but also significantly improves the mechanical strength of the structures, thus optimising their structural performance and service life.

3.2. Efficiency and Performance Verification of the Electronic System

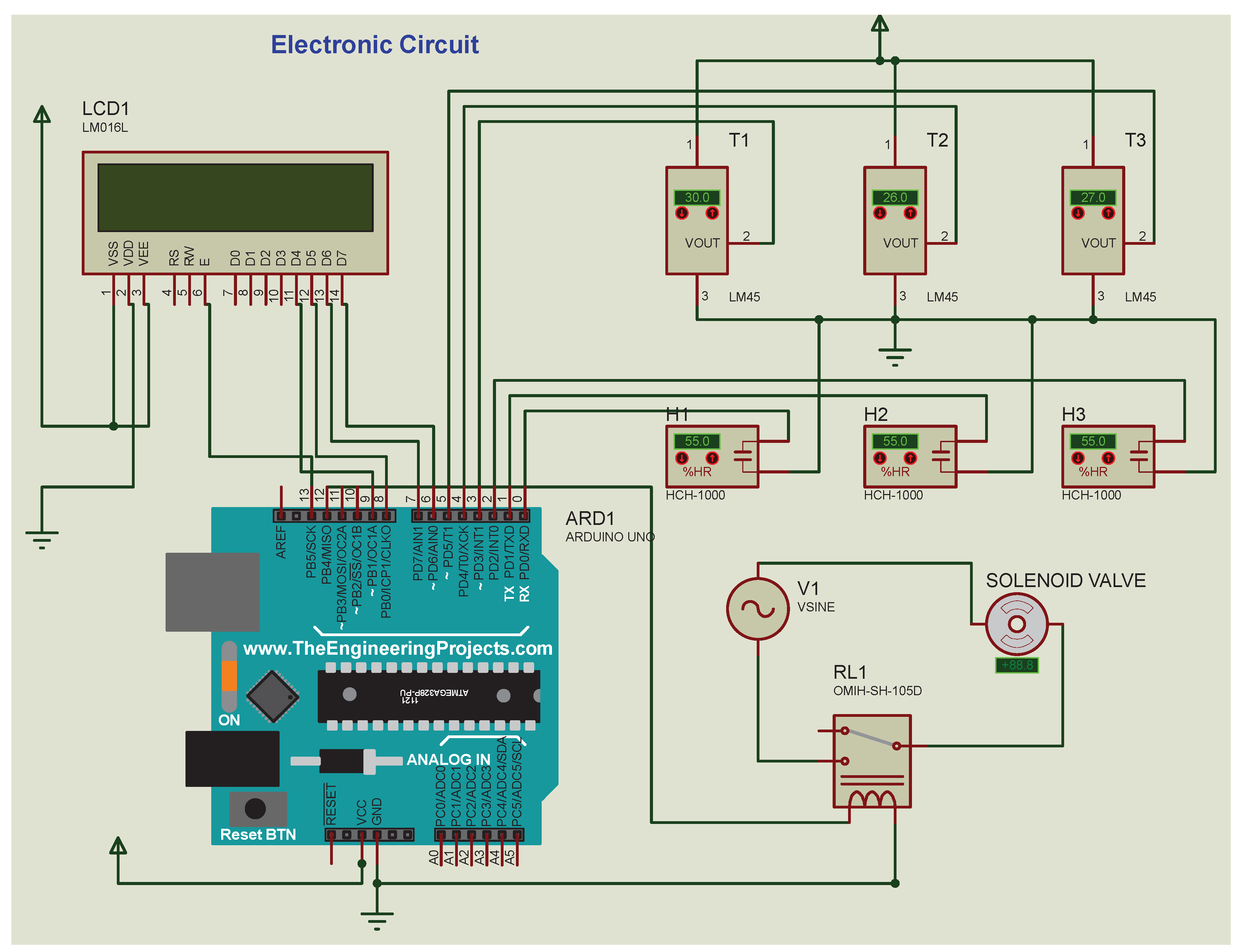

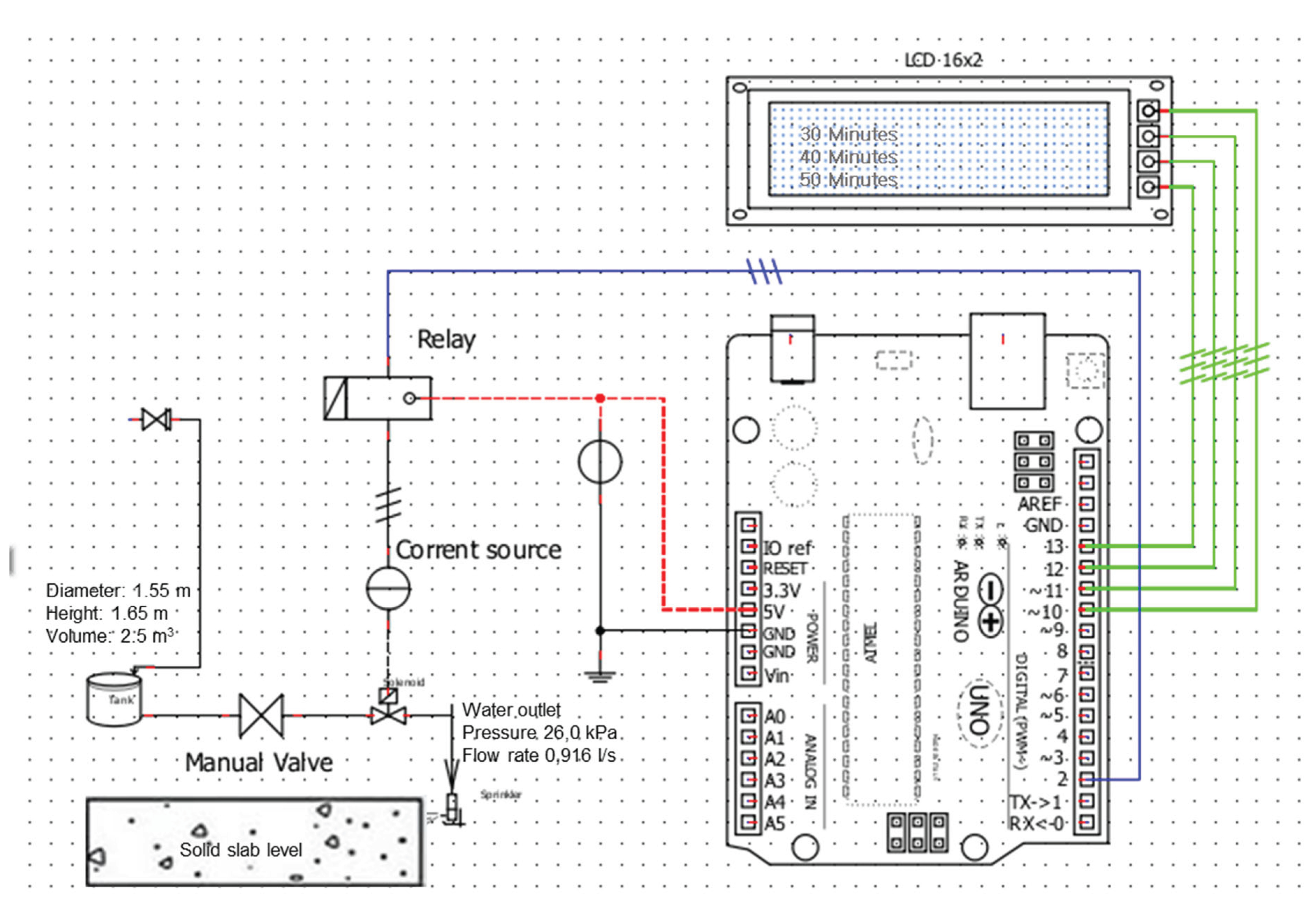

The experimental analysis of the designed electronic system revealed a high operational and functional efficiency in the automation of the concrete curing process. The circuit was composed of a hybrid architecture of analogue, digital and microcontroller (Arduino UNO) components, integrating sensors, actuators and control modules. This configuration allowed the monitoring of critical variables-such as temperature and humidity-both in the core and on the surface of the concrete, which optimised irrigation management, automated by sprinklers or solenoid valves, as shown in

Figure 10.

The behavioural simulations of the circuit were carried out in the Proteus and Multisim environments, validating its operation prior to physical implementation. These virtual tests were decisive in preventing failures, reducing costs and promoting a more efficient execution of the embedded system, as shown in

Figure 11. The strategic arrangement of sensors T1, T2, T3 (temperature) and H1, H2, H3 (humidity) allowed a three-dimensional evaluation of the internal conditions of the concrete, generating representative data for comparative analysis.

From a functional point of view, the selected sensors, such as DS18B20 for temperature and HD-38 for humidity in the concrete structure, demonstrated excellent sensitivity and stability in thermally variable environments. A key technical advantage was the use of sensors with direct digital output, which eliminated the need for analogue-to-digital converters (ADCs), reducing circuit complexity and improving sampling accuracy. Real-time data readout through the serial monitor on the Arduino IDE allowed experimental validation of the system's stability against external disturbances.

In programming (see

Figure 11 and

Table 1), the code loaded into the Arduino IDE environment allowed temperature and humidity thresholds to be set with integrated decision logic. The system activated or deactivated solenoid valves automatically, according to the values registered, managing to maintain the concrete in optimal curing conditions 24 hours a day.

The physical implementation confirmed that the data obtained in the simulation were close to real conditions. The concrete structures (columns and slabs) instrumented with sensors provided reliable measurements of the thermal evolution and internal humidity of the material. These results confirm that the use of microcontroller-based automation technologies represents a robust, accurate and economically viable tIl for on-site concrete quality control.

Finally, the predictive approach derived from these real-time monitoring systems allows the anticipation of concrete behaviour under extreme environmental conditions (such as high temperatures), thus contributing to increase structural safety, energy efficiency and durability of the material in civil construction projects.

3.3. Accuracy, Sensitivity and Response Time of Embedded Sensors

The instrumentation of structural moulds with temperature and humidity sensors demonstrated high accuracy in detecting internal variations during the curing process. The installation was performed immediately after the concrete was poured into the slab and column moulds, as shown in

Figure 12. The strategic location of the sensors - at discrete positions in the slab (P1, P2) and column (C1) - allowed a three-dimensional thermal and moisture profile of the concrete interior to be obtained.

The DS18B20 (temperature) and HD-38 (humidity) sensors embedded in the slab and column matrix showed an effective and stable response throughout the monitoring process. The accuracy of the readings reached deviations of less than ±0.6 °C for temperature and ±4 % for relative humidity, values that remained constant even under changing climatic conditions. This measurement stability is critical to ensure efficient cure control and prevent microstructural defects associated with premature drying.

Figure 13 illustrates the real-time readout of the embedded sensors, where the Arduino-based electronic circuitry, LCD display and acquisition modules allow for automatic data logging and dynamic trend visualisation. The Figure also presents the correlation of these records with the compressive strength tests on specimens, facilitating the comparative analysis between internal conditions of the concrete and its subsequent mechanical performance.

The data obtained reveal significant thermal differences between the P1 and P2 positions on the slab, especially during peak hours of solar radiation, confirming the sensitivity of the system to external factors such as shade, rain or direct insolation. In concrete, internal temperatures in the exposed areas (P2) were up to 20 °C higher than in the shadier areas (P1), affecting the evaporation rate and moisture retention. This variation could have a negative impact on the strength of the concrete if not monitored in a timely manner.

In addition, the moisture sensors detected differential losses of water content depending on the location, showing that the column had a higher retention compared to the slab. This is explained by the lower direct exposure and the more compact geometry of the column. These findings confirm the hypothesis that non-uniform curing can be prevented by localised monitoring, activating specific spray mechanisms where critical levels are identified.

In summary, the embedded sensors not only provided a reliable reading of the internal variables of the concrete, but their integration into an automated system made it possible to anticipate thermal and hydric deviations that could compromise the structural integrity. These results consolidate the validity of the system as a scientific tIl for diagnosis and control in civil works, contributing to the substantial improvement of the quality of curing in uncontrolled natural environments.

3.4. Internal Thermal and Hygrometric Analysis of Concrete

The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was applied to data collected at different time intervals (1-7, 8-14, 15-21 and 22-28 days), yielding p-values of 0.146, 0.204, 0.975 and 0.806, respectively. In all cases, the values exceeded the significance threshold of 0.05, so the null hypothesis of normality (H₀) is accepted. This confirms that the data follow a normal distribution in each period analysed, thus allowing the use of parametric statistical tests, which assume normality and homoscedasticity.

The results obtained reveal statistically significant differences between the thermohygrometer recordings and the sensors inserted in the concrete. Firstly, the mean difference in temperature was 2.36 units, with a p-value of 0.000 and a 95% confidence interval [1.852 - 2.865]. Secondly, the mean difference in humidity was even more marked, reaching 7.54 units, with a p-value of 0.000 and a 95% confidence interval [5.59 - 9.49]. In both cases, the intervals do not include the zero value, and the high t-statistics (9.550 for temperature and 7.928 for humidity) reinforce the evidence that the observed differences are not attributable to chance, but represent a real effect.

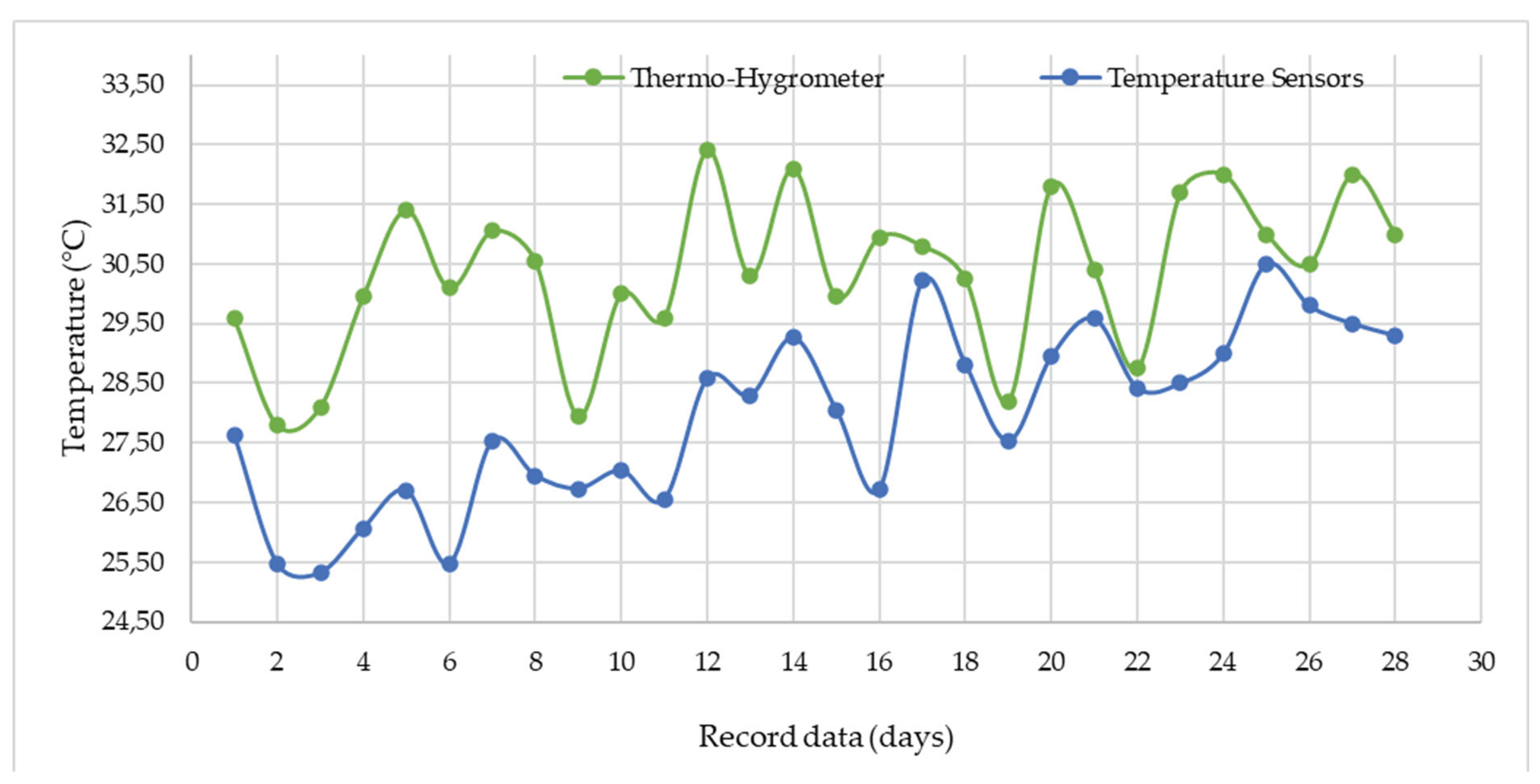

The thermal variation is shown in

Figure 14. It can be observed that the ambient temperature recorded by the thermohygrometer remains relatively stable over the 28 days, while the internal temperature of the concrete shows a slight progressive increase from the third day onwards. This trend is maintained despite the limited influence of external climatic factors such as solar radiation, precipitation, cloud cover and wind. This shows that the internal thermal evolution is regulated to a greater extent by internal concrete processes, such as cement hydration.

The Pearson correlation calculated between the two temperature measurements was r = 0.587 (p = 0.001), indicating a moderate positive and statistically significant relationship. This result suggests that there is a direct correspondence between ambient temperature and internal concrete temperature, in terms of daily averages.

On the other hand,

Figure 15 presents the evolution of ambient and internal relative humidity. In contrast to the thermal behaviour, the relative humidity values showed a high external instability influenced by the climatic environment. In contrast, the sensors inserted in the slab revealed a considerably more stable internal humidity, although with a decreasing trend over the curing time.

The Pearson correlation between external (thermohygrometer) and internal (humidity sensor) humidity was very weak, with r = 0.143 and p = 0.468. This value, not statistically significant, suggests that the internal humidity of concrete is hardly affected by external environmental conditions, consolidating the hypothesis that the hygrometric behaviour of concrete during curing is mainly due to its internal structure and hydration process.

Finally,

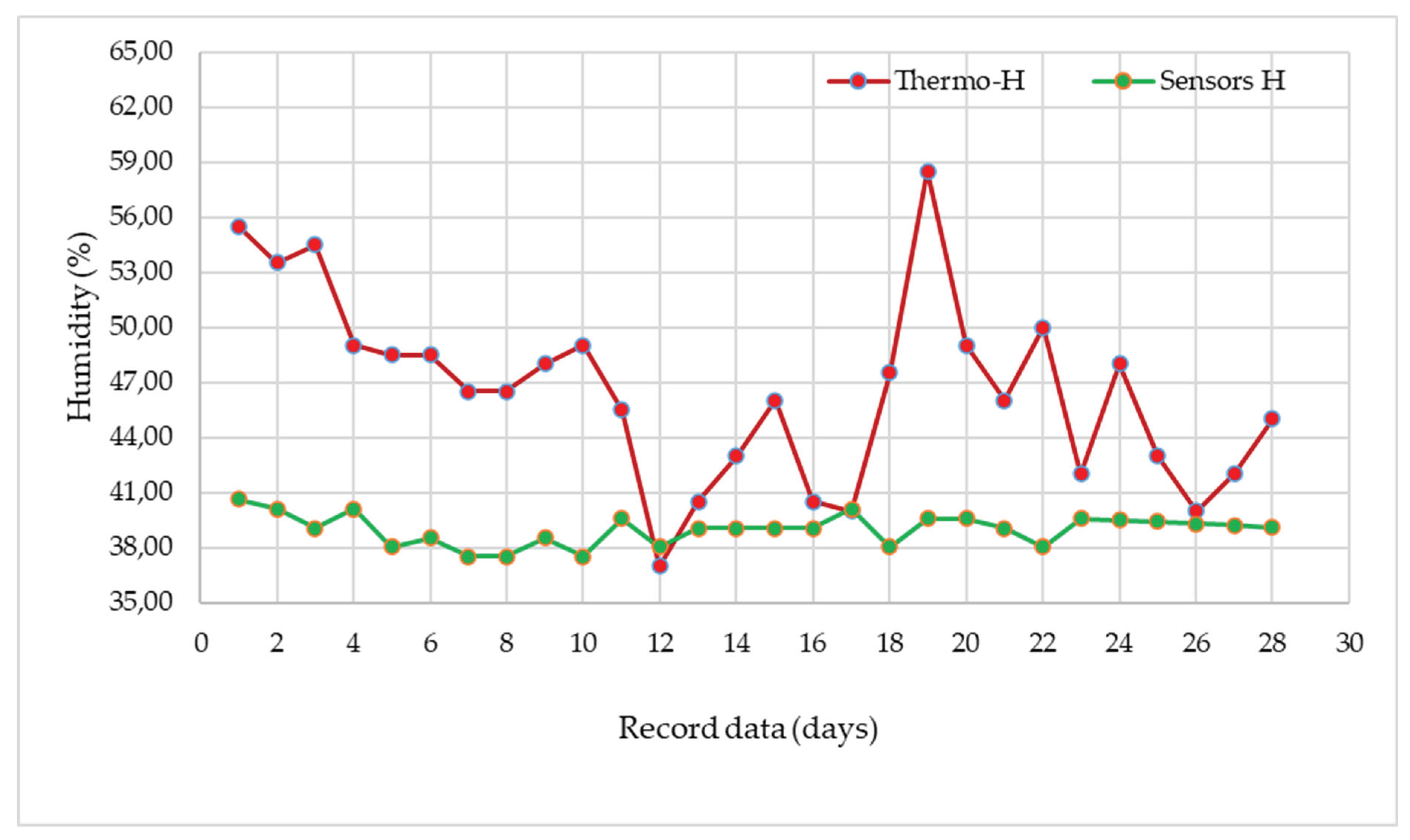

Figure 16, by means of boxplots grouped by hourly recording ranges, allows visualising the distribution of the temperature and humidity data as a function of the curing period.

The results obtained show an inverse relationship between temperature and relative humidity during the measurement period. Before 11:00 h, an average temperature of X̄ = 26.47 °C was recorded, accompanied by an average relative humidity of X̄ = 56.39 %. In contrast, between 11:00 and 14:00 h, the temperature rose to X̄ = 33.85 °C, while the relative humidity dropped to X̄ = 37.96 %. This inverse relationship is consistent with the principles of atmospheric thermodynamics, particularly the Clausius-Clapeyron Law, which states that the capacity of air to hold water vapour increases exponentially with temperature. Consequently, the higher the temperature, the more vapour the air can hold without reaching the saturation point, which reduces the relative humidity in the absence of an additional source of moisture. This daily thermal and hygrometric behaviour is characteristic of tropical or subtropical climates, where solar radiation intensifies progressively towards midday. Understanding these dynamics is essential for the analysis of thermal comfort, energy efficiency in buildings, irrigation planning in agricultural systems and the design of climate adaptation strategies at the local level.

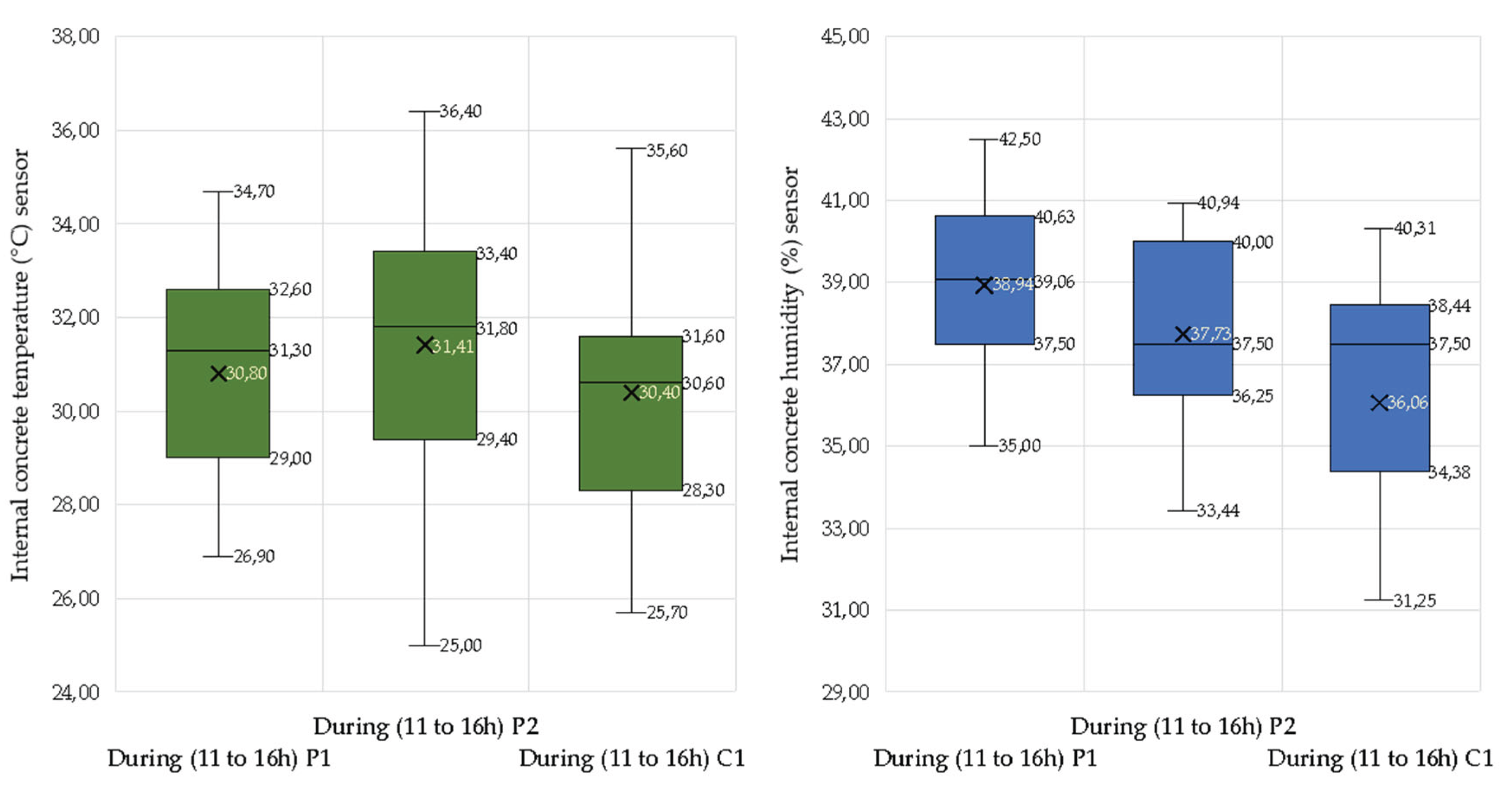

In addition, the data reflect a marked daily thermal variation, with clearly differentiated interquartile ranges between the two time periods, confirming that the ambient temperature is systematically higher after 11:00 h. This variability is mainly explained by the natural thermal transition associated with the increase in solar radiation towards midday, as well as by seasonal climatic factors (such as cloudiness, direct radiation or sporadic precipitation). This variability is mainly explained by the natural thermal transition associated with the increase of solar radiation towards midday, as well as by seasonal climatic factors (such as cloudiness, direct radiation or sporadic precipitation), the specific time of measurement and the local meteorological conditions of the study area. These findings are relevant for understanding environmental thermal behaviour in warm contexts and have practical implications in various fields, particularly in engineering. In particular, the thermal information obtained is key to optimise concrete curing practices, since prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures can compromise the cement hydration process and, consequently, the structural quality of the material. However, figures 17 and 18 show the behaviour of the phenomena inside the concrete (slab and column) read by the sensors.

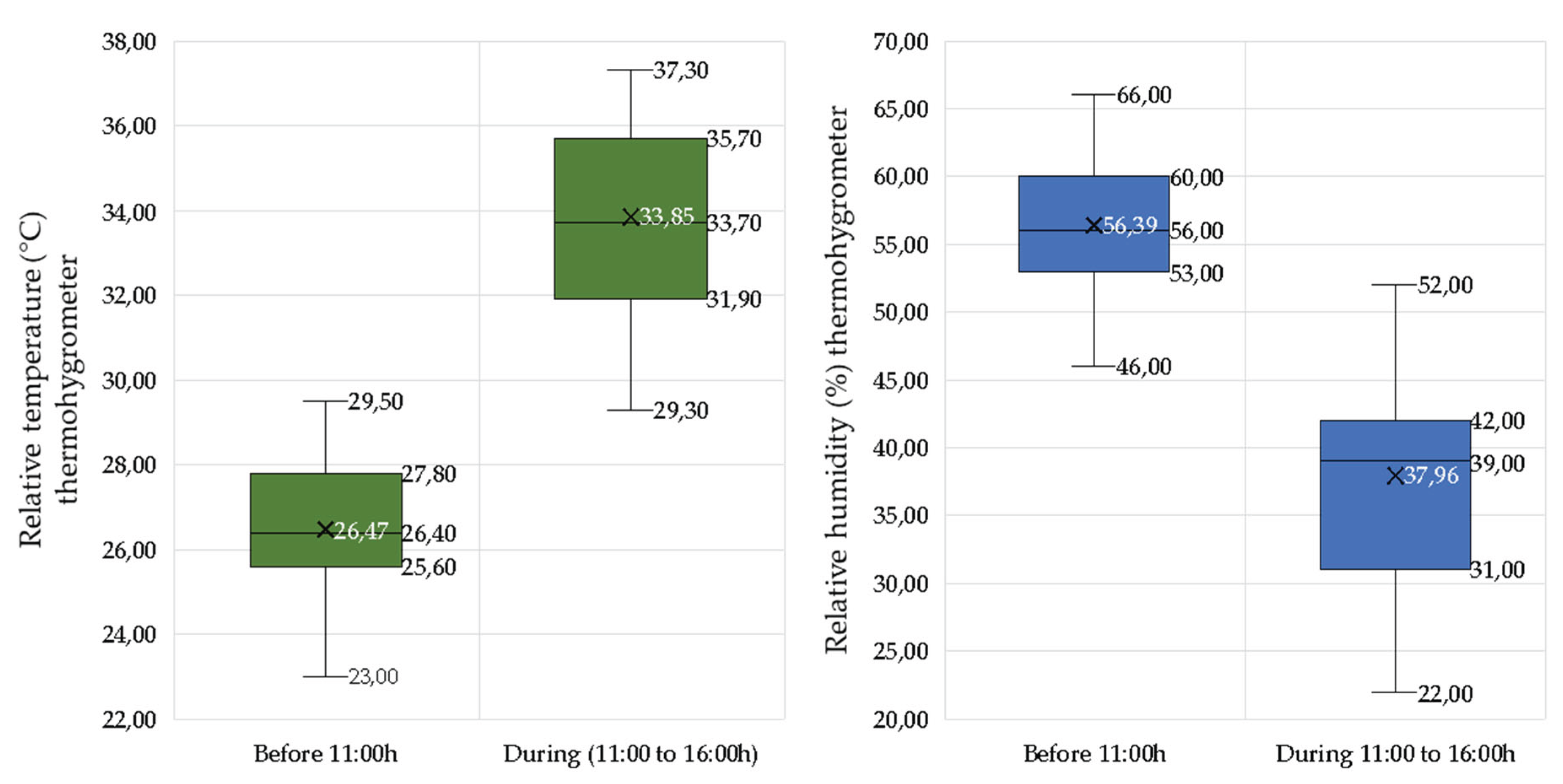

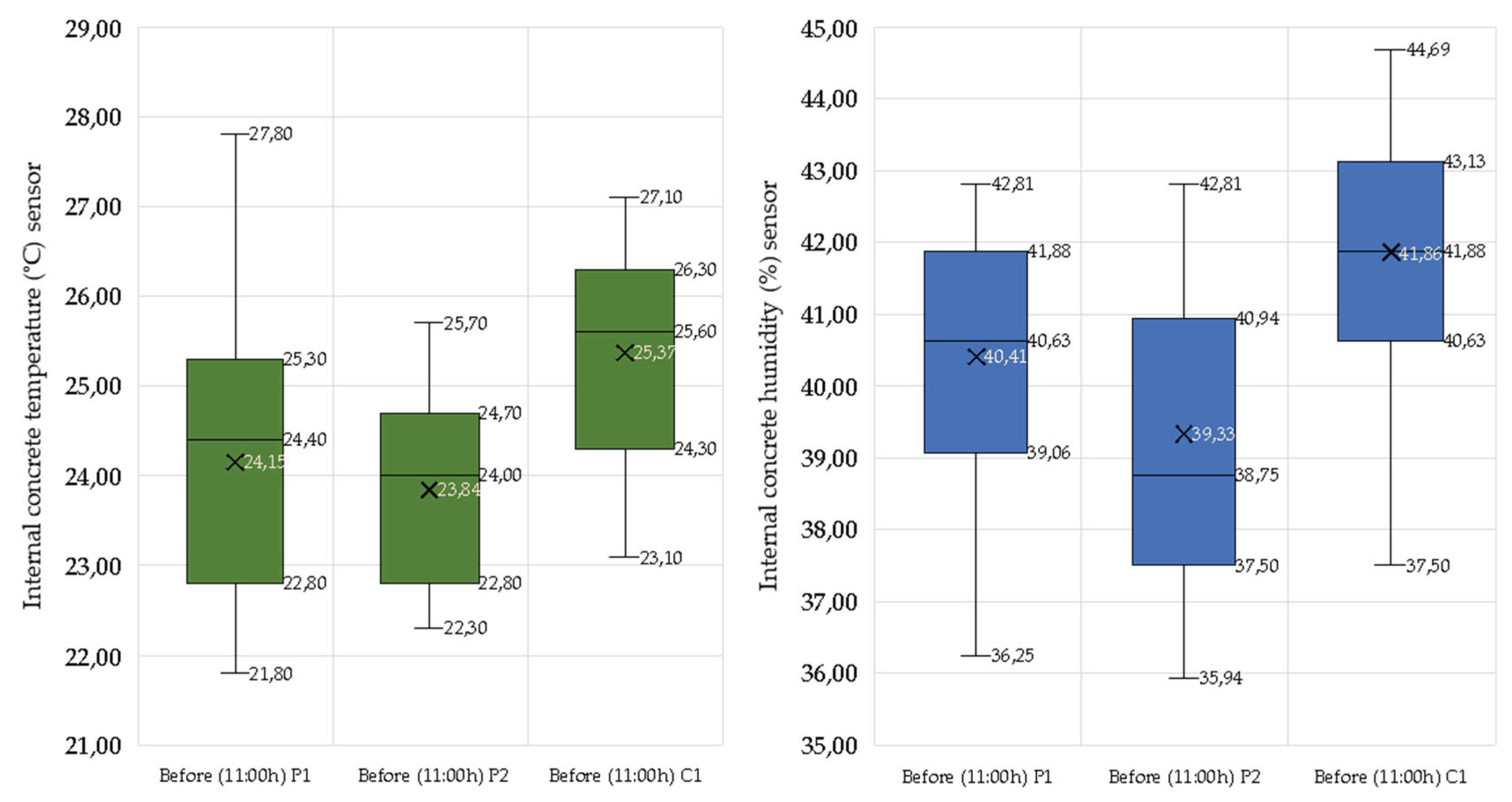

When comparing the ambient temperature data before 11:00 h, whose median was 26.47 °C, with the internal concrete temperatures recorded by the sensors installed in the structural elements (slab and column), it was observed that the medians were 24.15 °C, 23.84 °C and 25.37 °C, respectively. These differences are minimal and the boxplots show narrow ranges, which evidences a low thermal variability within the concrete during this period.

Regarding relative humidity, the ambient median recorded was 56.39 %, while the internal medians measured by the sensors were 40.41 %, 39.33 % and 41.86 %, respectively. Although these values are notably lower than those of the external environment, they also present a low internal variation, indicating some hygrometric stability within the concrete.

These results suggest that, during the first hours of the day, neither ambient temperature nor relative humidity have a direct and immediate effect on the internal conditions of the concrete. In particular, external moisture does not appear to transfer efficiently to the interior, highlighting the importance of implementing appropriate curing strategies to avoid moisture losses that could compromise the cement hydration process.

Figure 18.

Temperature and humidity behavior inside the concrete during 11:00 to 16:00 h.

Figure 18.

Temperature and humidity behavior inside the concrete during 11:00 to 16:00 h.

Figure 16 shows that the ambient temperature during the 11:00 to 16:00 h interval reached high values, with a median of 33.85 °C. As for the internal temperature of the concrete, the sensors installed at different positions (P1, P2 and C1) recorded medians of 30.30 °C, 31.41 °C and 30.40 °C, respectively. These values reflect minimal variation between sensor locations, indicating relative thermal stability within the concrete during this period. The low scatter of the data, evidenced by narrow interquartile ranges in the box plots, suggests that there are no significant thermal fluctuations internally, despite the increase in ambient temperature.

In the case of relative humidity, low ambient values were recorded, with a median of 37.97 %. Internally in the concrete, the median humidity values at positions P1, P2 and C1 were 38.94 %, 37.73 % and 36.06 %, respectively. Although the values remained relatively stable, a downward trend was evident, suggesting a gradual loss of internal moisture as the days of curing progressed. This behavior indicates that, although elevated ambient temperature does not produce significant thermal variations inside the concrete, it does contribute, cumulatively, to a progressive decrease in internal relative humidity. Therefore, it is concluded that the ambient temperature, by itself, does not have an immediate determining effect on the temperature and internal humidity of concrete, but could influence evaporation processes in the long term, potentially affecting the quality of curing.

3.5. Crack Formation and Detection by Embedded Monitoring

The evaporation rate (E) of water on surfaces, as in this case of solid slab concrete curing, particularly in conditions of high ambient temperatures of 30°C and moderate wind, i.e. in these conditions: the typical coefficient for wind speed of 4 m/s K= 0.01. saturation pressure of water at 30°C is Ps = 4.243kPa. Partial pressure of water in air, corresponding to a relative humidity of 35% is Pa = 1.5kPa and typical thermal resistance for a surface without direct protection R= 100 s/m. Replacing in equation 6, E = 0.00010972 liters/s, i.e., under these conditions, approximately 1,097 ml of water would be lost per second on the 4 m² of surface.

The first visible cracking appeared in the center of the slab (rIf) in the transverse direction. These initial cracks had an opening of approximately 0.01 mm. The observation of the exact moment of cracking of concrete in a slab is a critical event in structural engineering. In this case, it was detected that cracking occurred after evaporation of the water initially present on the surface of the concrete. This phenomenon can be related to several factors, such as structural design, material quality or external conditions, such as ambient weather. The event was observed two hours after pouring the mix into the slab, with an ambient temperature of 29.9°C and a relative humidity of 54%, as shown in

Table 1. The possible factors that influenced the cracking is the drying and hardening of the concrete can generate internal stresses due to volume reduction (by drying). High ambient temperatures produce dilatation; in addition, the quality of the material such as low strength mixes, excess water or defects in the placement of the concrete increase the probability of cracking. The consequences they can bring is the aesthetics because the visible cracks generate concerns, even if the cracks are deep, they can compromise the durability by allowing the entrance of water, chemical agents or chlorides that corrode the steel.

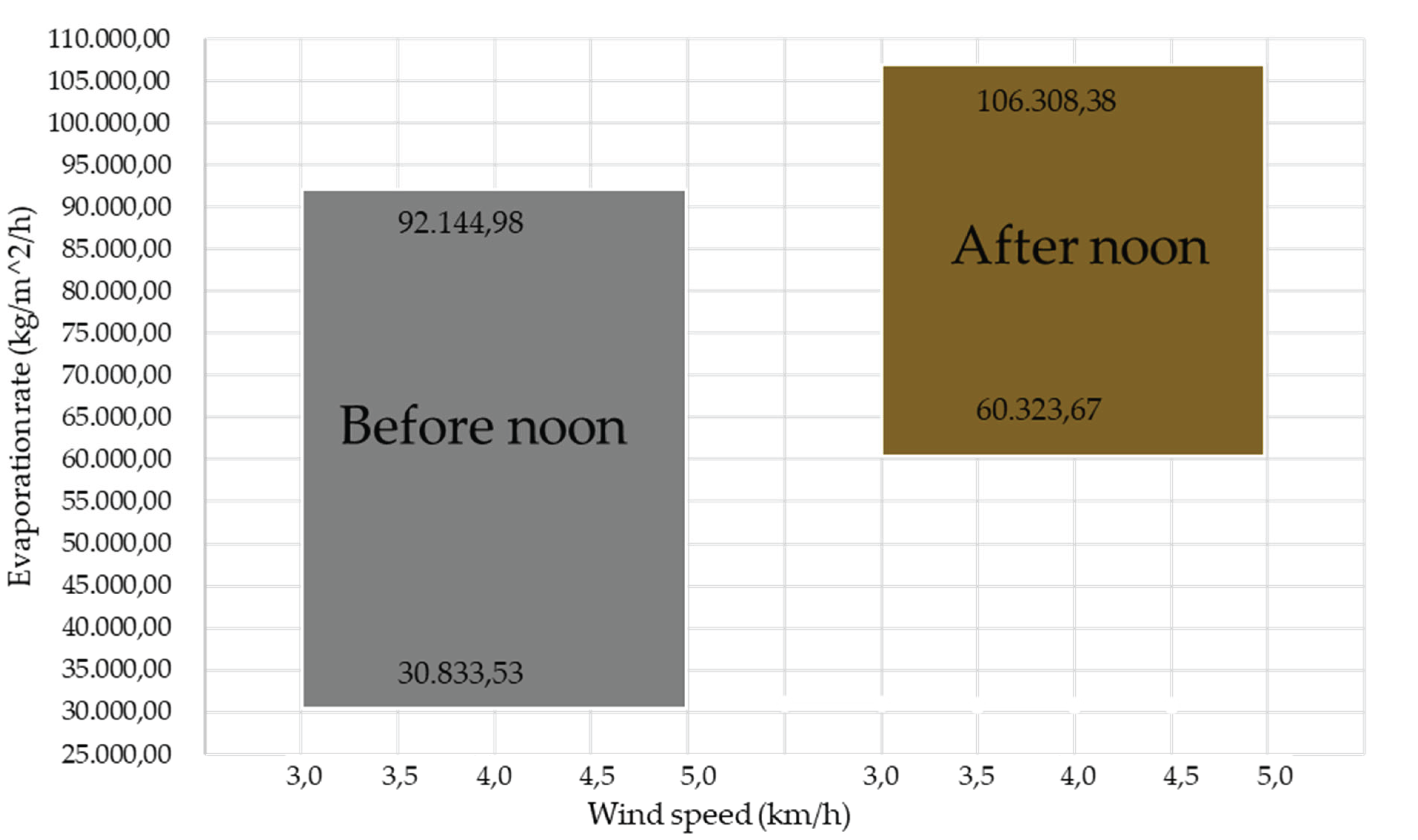

Figure 19 shows the variation of water evaporation in concrete under the environmental conditions recorded. In addition, its minimum and maximum values were calculated using Equation 1. The results indicate that evaporation is higher from 11:00 to 16:00 hours (UTC-5), in tropical zones.

3.6 Efficiency of the Automated Irrigation System in Curing

The volume of water calculated and supplied is 2 liters to irrigate 4 square meters of a solid slab. The output flow rate was determined using Torricelli's Equation 3 and considering a standard flow rate for a 1/2 inch pipe. The cross-sectional area of the pipe is and in typical domestic applications, the flow velocity usually ranges from 1 to 2 meters per second. Since 1 m^3 = 1000liters, the estimated flow rate is Q = 0.254 liters/second. To calculate the irrigation time required to irrigate 4 m², considering a volume of V = 0.002 m^3 (equivalent to 2 liters), the time t results between 7.87 and 15.87 seconds, depending on the actual flow velocity.

Calculating the volume of the cylindrical tank of 2500 liters, with a height h=1.65 m, h = 1.65 m, a radius r=0.775, and considering π=3.1416, we obtain, when applying equation 5, a volume of 3.11 m³.

This means that the tank has the capacity to store approximately 3110 liters. According to

Table 3, the estimated filling and emptying time is 5830 seconds. Applying equation 6, a flow rate of 0.53 L/s is calculated.

Table 2 shows the calculation of the quantity of water for curing the solid slab concrete for 28 days. For a tank with a capacity of 2500 liters and a filling time of 6875 seconds, applying Equation 6, a filling and emptying flow Q of 0.36 L/s is obtained. This same flow rate is applicable for a volume of 1680 liters under the same conditions.

This amount can always be lowered if only curing is done during the day. Since this proposed technique seeks to optimize the efficient use of water in buildings, thus contributing to one of the fundamental objectives at a global level: the sustainable management of water resources.

Table 3 shows the performance of the automated irrigation system with solenoid valve, varying the interval between irrigations. The longer the time between repetitions, the lower the number of daily irrigations and the total weekly irrigation time. The electrovalve worked a total of 5.83 hours in 7 days, reflecting efficiency in the use of water and energy.

Given that water is an increasingly scarce resource in various regions of the world due to its progressive decrease, it is essential to promote responsible water consumption practices. In addition, it is emphasized that the water used in construction processes must undergo specific treatments or come from alternative extraction sources, avoiding the use of potable water for human consumption.

3.7. Validation of the Elevated Tank as Part of the Automatic Curing System

The strategic location of the water tank is a key factor in the curing process of the solid slab, since it guarantees constant irrigation through a controlled sprinkling system, preventing concrete dehydration and the formation of cracks. The tank is elevated 1 meter above the slab and has a water height of 1.65 meters and a diameter of 1.55 meters. Based on these parameters, an outlet pressure of 26 kPa and a flow rate of 0.916 liters/second through a half-inch pipe was calculated using Equation 4. This design ensures an adequate water supply to maintain optimum curing conditions.

The controlled spray curing system, which covered a range of 90 to 360 degrees, was designed to optimize the periodicity of the water supply. Valve and hose control ensured uniform distribution over the slab surface. The tank base was designed to support the full tank load, equivalent to 2500 liters (approximately 25 kN), and was installed on a level platform on firm ground to ensure structural stability.

The automated system, illustrated in

Figure 20, regulates and maintains the water output for 8 seconds during each irrigation cycle, which is activated sequentially every half hour without human intervention. In addition, the frequency of watering varies every seven days to suit specific curing needs. The integration of the Arduino controller and solenoid valve enabled precise, real-time operation, significantly improving the efficiency of the process.

Discussion

Terrain selection was key to the validity of the results, since environmental factors such as altitude, pressure, temperature and humidity directly affected the performance of the sensors and equipment. Proper site preparation (leveling, energy, water) ensured optimal conditions for installation, maintenance and data collection, reinforcing experimental reliability and safety.

The concrete design and dosage were adequate and consistent with engineering standards. The specimens showed an increasing compressive strength within the expected values, following a logarithmic curve. This demonstrates that curing monitoring optimizes the mechanical strength of concrete and allows detecting deviations during the setting process.

The Arduino-based electronic system proved to be effective in automating and monitoring curing. The integration of digital sensors simplified data processing and enabled reliable real-time readout. Previous simulations with Proteus and Multisim improved the design and safety of the system, evidencing an innovative and low-cost approach to quality control in construction.

The installed sensors were able to identify significant variations in temperature and humidity due to external climatic conditions. This confirmed that curing is not a uniform process if not controlled. The use of sensors embedded in the concrete proved crucial to adjust the environmental conditions and ensure long-term structural durability.

The data followed a normal distribution, which enables the use of parametric statistics. The significant differences between the sensors and the thermohygrometer show that the internal sensors are more accurate in measuring actual curing conditions. The moderate correlation between external and internal temperature highlights the partial influence of the environment. In contrast, the low correlation in humidity suggests that the concrete maintains its microclimate. Boxplot analysis helped to identify asymmetries and extreme values, strengthening the interpretation of results.

Curing concrete is essential to ensure its stability and prevent cracking. In environments with temperatures above 25 °C, accelerated evaporation of the elemental liquid (H2O) during the early stages can affect proper cement hydration. While heat accelerates initial reactions, it also introduces challenges that compromise long-term material quality.

The study's findings provide valuable information for academia and industry, facilitating the development of advanced deep learning-based techniques for crack detection in concrete structures. The implementation of these approaches could optimize monitoring processes and improve the durability of buildings, thus contributing to the evolution of quality control systems in construction [

87].

Finally, long-term compressive strength may be affected: although initially high temperatures favor rapid strength development, incomplete hydration of the cement due to premature evaporation of water may compromise ultimate strength, reducing the durability of the structure. Compared to immersion curing results.

The automated irrigation system ensures a controlled and periodic supply of water to the solid slab, which reduces dependence on manual monitoring and lowers operating costs. In addition, it allows studying the impact of temperature during curing and supports the creation and application of automated control systems in structures which shares the idea of [

88].

Currently, electrical resistivity sensors are used for monitoring and controlling the quality of concrete, especially in structures exposed to aggressive conditions. Although these devices allow obtaining valuable data on the state of the material, they present important limitations: their high cost restricts their massive implementation, and their measurement capability is usually concentrated in a single point within the concrete mass, which reduces the spatial representativeness of the results. In this context, the use of polymer concrete has demonstrated, although in a smaller proportion compared to traditional technologies, an improvement in certain properties of reinforced concrete, such as durability and resistance to chemical agents, which could complement or reduce the dependence on sophisticated monitoring systems [

89].

Conclusions

Conclusion 1 - Characterization of soil conditions and experimental curing model:

The implementation of the experimental model in a location at 432 m a.s.l. allowed replicating real concrete curing conditions under controlled environmental parameters. The frame-type structure, with strategically embedded sensors in slab and columns, together with a digital thermo-hygrometer, facilitated continuous and reliable monitoring of temperature and humidity. This configuration provided representative thermal and hygrometric data, fundamental to analyze the behavior of the concrete in the field, considering the geographical and altitudinal influence on the curing process.

Conclusion 2 - Evaluation of mechanical behavior by compression testing:

Continuous monitoring by embedded sensors significantly improved the understanding of the curing process and its effect on the compressive strength of concrete. A direct correlation was observed between sensor location and accuracy in tracking mechanical development, validated through a predictive logarithmic model. This automated approach optimizes concrete hardening, ensures regulatory compliance (ACI) and prolongs structural service life, consolidating the value of intelligent monitoring as a key tIl in modern design.

Conclusion 3 - Efficiency and performance verification of the electronic system (already reviewed):

A low-power embedded electronic architecture was developed, designed to integrate multiple digital sensors for continuous monitoring of temperature, flow and pressure in fresh and hardened concrete. The system dispensed with analog-to-digital converters by employing a direct digital interface based on sensors such as the DS18B20 and HD-38, cIrdinated through Arduino embedded logic. The validation, performed through simulations in Proteus, Multisim and QElectroTech, and field tests under real curing conditions, demonstrated high energy efficiency, operational reliability and adaptability in demanding construction contexts.

Conclusion 4 - Accuracy, sensitivity and response time of embedded sensors:

The embedded sensors demonstrated high accuracy and stability in the measurement of temperature and internal humidity of concrete during the curing process, even under varying environmental conditions. Thermal and humidity differences between exposed and shaded areas highlight the need for localized monitoring to avoid uneven curing. The early response of the system allowed the activation of targeted irrigation mechanisms, optimizing moisture retention. The correlation between internal variables and mechanical resistance reaffirms the predictive potential of this instrumentation as a preventive control tIl in works exposed to non-uniform natural environments.

Conclusion 5 - Internal thermal and hygrometric analysis of concrete:

The thermal and hygrometric analysis revealed that the internal temperature of concrete increases gradually due to hydration processes, while the internal humidity decreases steadily, without depending significantly on ambient conditions. Although ambient temperature showed some correlation with internal temperature, relative humidity did not have a significant influence. These findings show that the internal properties of concrete respond more to its own structure than to the external environment, highlighting the importance of adequate curing strategies to avoid moisture loss and guarantee its structural integrity.

Conclusion 6 - Crack formation and detection through embedded monitoring:

Real-time monitoring identified early crack formation in the slab, associated with a high rate of surface evaporation. The cracking, which occurred approximately two hours after casting, coincided with conditions of high temperature (29.9 °C), low relative humidity (54%) and an estimated evaporation of 1,097 ml/s in 4 m². Factors such as lack of surface protection, pIr mixes and inadequate placement aggravated the phenomenon. This analysis reinforces the need for immediate preventive interventions, such as spray curing, to mitigate structural damage and preserve concrete durability.

Conclusion 7 - Efficiency of the automated irrigation system in curing:

The automated irrigation system demonstrated operational efficiency when using a controlled volume of 2 liters per 4 m² and flow rates between 0.254 and 0.53 L/s. The management by means of solenoid valves and variable programming made it possible to reduce the weekly irrigation time without affecting curing efficiency. In 28 days, a total consumption of 1,680 liters was achieved, showing a 20% rational use of water resources. These results validate the feasibility of sustainable strategies based on automated technologies, which contribute to water conservation in civil works without compromising the quality of the concrete.

Conclusion 8 - Validation of the elevated tank as part of the automatic curing system:

The automatic control system with elevated tank showed an efficient performance in the curing of solid slabs, maintaining constant pressure (26 kPa) and uniform flow (0.916 L/s). Arduino-based automation and solenoid valves allowed precise and periodic irrigation cycles, with minimal human intervention. The strategic location and hydraulic design of the tank ensured homogeneous coverage by 360° sprinkling. The structure, with a load capacity of up to 25 kN, ensured functional stability. This integrated system proved to be a technical and sustainable solution to preserve optimal curing conditions and prevent premature defects.

Conclusion 9 - Comprehensive validation of the intelligent automated curing system by comparison of results obtained with conventional methods.

Overall, the results show that the integration of embedded instrumentation, automatic control and efficient irrigation strategies allows optimizing concrete curing under real conditions, reducing structural defects and promoting sustainable practices. This study represents a significant advance over traditional techniques, and lays the foundation for the development of intelligent curing systems adaptable to different climatic and construction contexts.

Ethical aspects

This research was developed under strict ethical principles, prioritizing respect for the participants' autonomy, beneficence and justice. National and international regulations in force were complied with, as well as the provisions of the Code of Ethics of the Institutional Ethics Committee and the Bases of the UNIFSLB 2024 Teaching Competition, ensuring scientific integrity and respect for the rights of all those involved.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Papa Pio Ascona García: Writing (prIfreading and editing), Writing (original draft), research. Guido Elar Ordoñez Carpio: Monitoring, validation. Wilmer Moisés Zelada Zamora: Project Management. Marco Antonio Aguirre Camacho: Conceptualization. Wilmer Rojas Pintado: Formal Analysis and Visualization. Emerson Julio Cuadros Rojas: Data curation and methodology. Hipatia Merlita Mundaca Ramos: Acquisition of financing and resources. Nilthon Arce Fernández: software.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that there are no financial conflicts or personal relationships that could have affected the development or presentation of the content of this article.

Data availability

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I express my deep gratitude to the Universidad Nacional Intercultural Fabiola Salazar Leguía of Bagua, Amazonas - Peru, for providing access to its equipment and laboratories, which were essential for the experimental tests and sample analysis. I also acknowledge their valuable financial support, granted through institutional competitions, which made possible the partial development of this research.I also extend my gratitude to my collaborators and to the external researchers, whose contributions, comments and suggestions were essential to achieve the expected results in a satisfactory manner.

References

- A. Burlacu et al., “Innovative Passive and Environmentally Friendly System for Improving the Energy Performance of Buildings,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 2022; 20. [CrossRef]

- E. Común, A. E. Común, A. Sanabria, L. Mosquera, and A. Torre, “Application of self-curing concrete method using polyethylene glycol,” in Proceedings of the LACCEI international Multi-conference for Engineering, Education and Technology, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jahani, M. Y. Jahani, M. Baena, C. Barris, R. Perera, and L. Torres, “Influence of curing, post-curing and testing temperatures on mechanical properties of a structural adhesive,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Al Mughairi, T. M. Al Mughairi, T. Beach, and Y. Rezgui, “Post-occupancy evaluation for enhancing building performance and automation deployment,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 2023; 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Younis and M. Nazari, “Optimizing Sustainability of Concrete Structures Using Tire-Derived Aggregates: A Performance Improvement Study,” CivilEng, vol. 5, no. 2024; 1. [CrossRef]

- B. Lou and F. Ma, “Evolution on fracture properties of concrete during steam curing,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2022; 16. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Baek, K. I. S. H. Baek, K. I. Lee, and S. M. Kim, “Development of Real-Time Monitoring System Based on IoT Technology for Curing Compound Application Process during Cement Concrete Pavement Construction,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 2023; 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ouyang, R. J. Ouyang, R. Guo, X. Y. Wang, C. Fu, F. Wan, and T. Pan, “Effects of interface agent and cIling methods on the interfacial bonding performance of engineered cementitious composites (ECC) and existing concrete exposed to high temperature,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Joshaghani, M. A. Joshaghani, M. Balapour, and A. A. Ramezanianpour, “Effect of controlled environmental conditions on mechanical, microstructural and durability properties of cement mortar,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Tan and O. E. Gjorv, “Performance of concrete under different curing conditions,” Cem Concr Res, vol. 26, no. 1996; 3. [CrossRef]

- R. Alyousef, W. R. Alyousef, W. Abbass, F. Aslam, and S. A. A. Gillani, “Characterization of high-performance concrete using limestone powder and supplementary fillers in binary and ternary blends under different curing regimes,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2023; 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, B. J. Shi, B. Liu, F. Zhou, S. Shen, A. Guo, and Y. Xie, “Effect of steam curing regimes on temperature and humidity gradient, permeability and microstructure of concrete,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Souza et al., “Smart Concrete Using Optical Sensors Based on Bragg Gratings Embedded in a Cementitious Mixture: Cure Monitoring and Beam Test,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 24, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Ikumi, I. T. Ikumi, I. Cairó, J. Groeneveld, A. Aguado, and A. de la Fuente, “Embedded Wireless Sensor for In Situ Concrete Internal Relative Humidity Monitoring,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 2024; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, J. J. Yang, J. Fan, B. Kong, C. S. Cai, and K. Chen, “Theory and application of new automated concrete curing system,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 2018; 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Martinelli et al., “Pseudo-Adiabatic Concrete Curing Monitoring IoT-Enabled System,” in 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 and IoT, MetroInd4.0 and IoT 2023 - Proceedings, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Cataldo, R. A. Cataldo, R. Schiavoni, A. Masciullo, G. Cannazza, F. Micelli, and E. De Benedetto, “Combined punctual and diffused monitoring of concrete structures based on dielectric measurements,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 2021; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Tareen, J. N. Tareen, J. Kim, W. K. Kim, and S. Park, “Fuzzy logic-based and nondestructive concrete strength evaluation using modified carbon nanotubes as a hybrid pzt–cnt sensor,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 2021; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Z. Taffese and E. Mater Today Proc, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, X. T. Wang, X. Gao, Y. Li, and Y. Liu, “An orthogonal experimental study on the influence of steam-curing on mechanical properties of foam concrete with fly ash,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2024; 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Donadello, C. I. Donadello, C. Di Francescomarino, F. M. Maggi, F. Ricci, and A. Shikhizada, “Outcome-Oriented Prescriptive Process Monitoring based on Temporal Logic Patterns,” Eng Appl Artif Intell, vol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, S. W. Liu, S. He, J. Mou, T. Xue, H. Chen, and W. Xiong, “Digital twins-based process monitoring for wastewater treatment processes,” Reliab Eng Syst Saf, vol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Huang et al., “Non-destructive test system to monitor hydration and strength development of low CO2 concrete,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Babu et al., “IoT-Based Intelligent System for Internal Crack Detection in Building Blocks,” J Nanomater, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Korda, E. E. Korda, E. Tsangouri, D. Snoeck, G. De Schutter, and D. G. Aggelis, “The sensitivity of Acoustic Emission (AE) for monitoring the effect of SAPs in fresh concrete,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. M. Reddy, S. V. M. Reddy, S. Hamsalekha, and V. S. Reddy, “An IoT enabled real-time monitoring system for automatic curing and early age strength monitoring of concrete,” in AIP Conference Proceedings, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim, D. S. Kim, D. Jung, J. Y. Kim, and J. H. Mun, “Study on Early Age Concrete’s Compressive Strengths in Unmanaged Curing Condition Using IoT-Based Maturity Monitoring,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 2024; 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Bhavsar, B. D. Bhavsar, B. Limbasia, Y. Mori, M. Imtiyazali Aglodiya, and M. Shah, “A comprehensive and systematic study in smart drip and sprinkler irrigation systems,” Smart Agricultural Technology, vol. 2023; 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Qian, P. J. Qian, P. Zhang, Y. Wu, R. Jia, and J. Yang, “Study on Corrosion Monitoring of Reinforced Concrete Based on Longitudinal Guided Ultrasonic Waves,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 2024; 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Ziaja, M. D. Ziaja, M. Jurek, and A. Wiater, “Elastic Wave Application for Damage Detection in Concrete Slab with GFRP Reinforcement,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 2022; 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Feng, Z. S. Feng, Z. Huang, and H. Zhao, “Doping dependence of Meissner effect in cuprate superconductors,” Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications, vol. 470, no. 2010; 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, H. R. Wang, H. Wu, M. Zhao, Y. Liu, and C. Chen, “The Classification and Mechanism of Microcrack Homogenization Research in Cement Concrete Based on X-ray CT,” Buildings, vol. 12, no. 2022; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. S. Tang, Y. Y. Z. S. Tang, Y. Y. Lim, S. T. Smith, A. Mostafa, A. C. Lam, and C. K. Soh, “Monitoring the curing process of in-situ concrete with piezoelectric-based techniques – A practical application,” Struct Health Monit, vol. 22, no. 2023; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Al Agha, S. W. Al Agha, S. Pal, and N. Mater Today Proc, A: health monitoring of concrete curing using piezoelectric sensor and electromechanical impedance (EMI) technique, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Guo, W. L. Guo, W. Wang, L. Zhong, L. Guo, F. Zhang, and Y. Guo, “Texture analysis of the microstructure of internal curing concrete based on image recognition technology,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2022; 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. C. Lo, H. W. T. Kwok, M. F. F. Siu, Q. G. Shen, and C. K. Lau, “Internet of Things-Based Concrete Curing Invention for Construction Quality Control,” Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Prakash, S. K. A. Prakash, S. K. Munipally, and P. A. E. Fernando, “Prediction of Concrete Constituents’ Behavior Using Internet of Things (IoT),” in Key Engineering Materials, vol. 959, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Kunhi Mohamed, A. A. Kunhi Mohamed, A. Bouibes, M. Bauchy, and Z. Casar, “Molecular modelling of cementitious materials: current progress and benefits,” RILEM Technical Letters, vol. 2022; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Monteagudo Honrubia, J. M. Monteagudo Honrubia, J. Matanza Domingo, F. J. Herraiz-Martínez, and R. Giannetti, “Low-Cost Electronics for Automatic Classification and Permittivity Estimation of Glycerin Solutions Using a Dielectric Resonator Sensor and Machine Learning Techniques,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 2023; 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Komary, S. M. Komary, S. Komarizadehasl, N. Tošić, I. Segura, J. A. Lozano-Galant, and J. Turmo, “Low-Cost Technologies Used in Corrosion Monitoring,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Alhamad, S. A. Alhamad, S. Yehia, É. Lublóy, and M. Elchalakani, “Performance of Different Concrete Types Exposed to Elevated Temperatures: A Review,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Ptacek, A. L. Ptacek, A. Strauss, B. Hinterstoisser, and A. Zitek, “Curing assessment of concrete with hyperspectral imaging,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 2021; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Fernandes, N. M. F. P. Fernandes, N. M. F. Almeida, and J. R. S. Baptista, “The Concrete at the 4th Industrial Revolution,” in Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Zeyad et al., “Review on effect of steam curing on behavior of concrete,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Tumpu, Irianto, and H. Parung, “The Effect of Curing Methods on Compressive Strength of Concrete,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, B. H. Wang, B. Guo, Y. Guo, R. Jiang, F. Zhao, and B. Wang, “Effects of Curing Methods on the Permeability and Mechanism of Cover Concrete,” Journal of Building Material Science, vol. 5, no. 2023; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Liu, J. B. Liu, J. Jiang, S. Shen, F. Zhou, J. Shi, and Z. He, “Effects of curing methods of concrete after steam curing on mechanical strength and permeability,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. S. Mohe, Y. W. N. S. Mohe, Y. W. Shewalul, and E. C. Agon, “Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of concrete using different sources of water for mixing and curing concrete,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2022; 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Saravanakumar, K. S. R. Saravanakumar, K. S. Elango, G. Piradheep, S. Rasswanth, and C. Mater Today Proc, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. Zeyad et al., “Influence of steam curing regimes on the properties of ultrafine POFA-based high-strength green concrete,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 2021; 38. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, G. X. Wang, G. Wang, F. Gong, L. Qin, Z. Gao, and X. Cheng, “Evaluation and Analysis of Asphalt Concrete Density Based on Core Samples,” Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 36, no. 2024; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, S. A. Kumar, S. Saxena, and V. S. Rawat, “Effect of Various Methods of Curing on Concrete Using Crusher Dust as Replacement to Natural Sand,” Macromol Symp, vol. 413, no. 2024; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, G. Liu, and G. Zhang, “Effect of Curing Time on the Surface Permeability of Concrete with a Large Amount of Mineral Admixtures,” Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Jin et al., “Influence of curing temperature on freeze-thaw resistance of limestone powder hydraulic concrete,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2022; 17. [CrossRef]

- H. U. Ahmed, A. S. H. U. Ahmed, A. S. Mohammed, R. H. Faraj, S. M. A. Qaidi, and A. A. Mohammed, “Compressive strength of geopolymer concrete modified with nano-silica: Experimental and modeling investigations,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 2022; 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J. Y. Wang, J. Zhu, Y. Guo, and C. Wang, “Early shrinkage experiment of concrete and the development law of its temperature and humidity field in natural environment,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 2023; 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]