1. Introduction

Climbing to very high altitudes has become much commoner in recent years as access to remote areas has rapidly improved, and the associated expense has fallen in relative terms. However, the limitations imposed on time and resources has led to many ascents being made more rapidly. Rapid ascent to very high altitude is known to carry greater risks than a more gradual ascent, but we have only found one comparative study of fast versus slow ascent to very high altitudes under similar conditions [

1].

The human body is exposed to many risks when ascending to high elevations. Adverse and changeable weather conditions, cold, high winds, and the risk of ice, rock fall or avalanche may be encountered even at relatively low altitudes. Likewise, the dangers posed by poor visibility, difficult terrain and dehydration are often under appreciated by climbers [

2]. More predictable is the change in partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) in inspired air, which can have profound effects on human physiology [

3].

Failure of the human body to adjust adequately to the physiological challenges imposed by hypoxia can cause acute altitude illness. Physical fitness does not predict the probability of developing this, while genetic factors also play a part in susceptibility. Blood oxygen levels drop more at night, so ascending slowly and taking occasional ‘rest days’ to climb high and then return to lower elevations to sleep greatly reduces stress and facilitates acclimatisation. This approach protects against the development of acute altitude sickness, but the effectiveness of this approach diminishes above 8,000m, the height close to Mt Everest [

3,

4]. Acclimatisation increases the climber’s sense of well-being and enjoyment, while improving their sleep and capacity for physical endurance.

Mountain medicine defines three altitude zones which correspond with reducing pO2 and are associated with increasing risks of developing acute mountain sickness (AMS) [

5]. These zones are high altitude (1,500–3,500 m), very high altitude (3,500–5,500 m) and extreme altitude (>5,500 m). Medical problems at these altitudes also include the risks of high-altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) [

14]. Treatment with nifedipine and / or dexamethasone [

6] may be required, while the risk of neurological damage is increased at extreme altitude [

7]. People who develop AMS demonstrate alterations in anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) and those at risk of developing HAPE may notice reduced urine production prior to developing respiratory symptoms [

8]. A reduction in the efficiency of digestion occurs at high altitude [

9] and other adverse effects include dehydration, hypothermia and sunburn.

As altitude increases, atmospheric pressure falls and there is an associated reduction in pO2. At sea level, atmospheric pressure is 760mmHg, giving an inspired oxygen tension of 148mmHg. Atmospheric pressure is reduced by half at 5500m above sea level to 380mm Hg, with a corresponding fall in pO2 to 69mmHg. At an altitude of 8900m, near the height of mount Everest, these values fall to around 30% of their sea level baseline. As the pressure of inspired oxygen decreases, this leads to reductions in alveolar and arterial oxygen pressures. Indeed, at 4560m arterial oxygen saturation is around 70% in unacclimatised trekkers but rises significantly within a few days [

4]. At this height, the unacclimatised climber will be distressed, displaying breathlessness and significantly reduced exercise tolerance. The stress on the body brought upon by hypoxia is also influenced by ascent rate and the severity and duration of exposure [

10].

Humans can acclimatise to the hypoxia encountered at altitude. In the acute phase following ascent, the reduction in pO2 is detected by peripheral chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies, triggering a hyper-ventilatory response and increasing both tidal volume and respiratory rate [

11].

Although the in-vitro oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve shifts to the right at moderate altitudes mediated by increased levels of 2,3 DPG, the in-vivo situation differs. Respiratory alkalosis increases above moderate altitude producing a left shift in the curve, improving oxygen delivery to active tissues chiefly as a result of respiratory alkalosis. This in turn relates to the increase in red cell 2,3-DPG [

12].

Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction leads to improved matching of ventilation and perfusion within the lung. The subsequent elevation in pulmonary artery pressure may ultimately lead to right ventricular hypertrophy [

13]. There are corresponding cardiovascular changes, with tachycardia, increased cardiac output and rising blood pressure mediated by increased sympathetic drive. Increased diuresis leads to a higher haematocrit as plasma volume reduces and blood becomes more concentrated [

14]. Despite these early adaptations, there is a reduction in cognitive function with hypoxia, which contribute towards accidents and poor decision making at extremes of altitude.

Further acclimatisation occurs over several days. As minute ventilation remains high, the body slowly adapts to the resulting respiratory alkalosis by increasing renal excretion of bicarbonate. This compensatory mechanism takes about 100 hours and is accelerated by acetazolamide [

15]. Lactate production falls as capillaries proliferate in skeletal muscle to maintain muscle function [

16]. Increased production of erythropoietin by the kidney in response to hypoxia stimulates haematopoiesis. Haematological adaptation to altitude is complete when polycythaemia occurs. This takes 45 days at an altitude of 4000m, but the upper altitude limit of this adaptation has not yet been clearly defined [

17]. However, haemoglobin concentrations can rise to 200g/l, and greater blood viscosity increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, retinal damage and stroke [

18].

The present study was designed to compare the effects of a gradual ascent to very high altitude with those of a rapid ascent on human physiological responses. Comparative data on this subject is presently very limited and is well overdue.

2. Methods

2.1. Aim

In this report we compare and contrast the effects on human physiology of rapid versus slow ascent to 5,300m by comparable groups under similar conditions using pulse oximetry for the first time. We also compare cardiac adaptation, symptoms, pharmacological consumption and AMS scores between the two groups to provide a comprehensive and clinically relevant comparison of the two approaches. Inclusion criteria were that individuals had no serious pre-existing cardiopulmonary disease. Exclusion criteria were refusal to train adequately, refusal of consent to regular physiological assessment and failure to achieve an altitude of at least 5,300 m altitude.

2.2. Details Group 1

Over twelve days in early March 2024, 13 people (6 females) from 10 countries across 5 continents, met in Kathmandu in Nepal to climb to Everest Base Camp (Group 1). The group had a median age of 33 years (range 25-66). Led by two male Nepali guides, the group ascended gradually from 2,300, via Lukla (2,860m), to Everest Base Camp at 5,300m, and then further up to Kala Patthar (5,700m) over an 8-day period. The average cumulative ascent gained each day was 500m, as the group had two rest days when they climbed then descended, spending two consecutive nights at the same altitude.

Given that the route was undulating, their total ascent amounted to 6,300m, with an average daily height gain of 788m. The group then descended back to Lukla over a further 4 days, before flying back to Kathmandu. The group all used 4 season sleeping bags to help cope with nocturnal temperatures which dropped to -15C.

All symptoms, signs and medication used were recorded by a physician (CK). Polyuria was defined as the passing of >2.5L urine over 24 hours, but practicalities prevented an objective assessment of this while trekking. Hence daily urine volumes were estimated by each individual with reference to frequency and duration of micturition. The AMS score for each individual was calculated from symptoms recorded, using the 2018 modification of the Lake Louise score, classifying mild AMS as a score of 3-5, and moderate AMS as a score of 6-9 [

18].

Each person’s pulse oximetry and heart rate (HR) was measured every 500m. The highest altitude at which recordings were taken was 5,300m. On each occasion the highest of three readings for oximetry and the lowest of three readings for HR was recorded using a finger probe (Oxypulse, Ecomerzpro, Madrid, Spain). Participant enjoyment of each trek was assessed on a simple Likert scale from 0 (worst experience) to 10 (best experience) after descent.

2.3. Details Group 2

The results from this trek were compared with those obtained in late February 2018 from Group 2 comprising 7 people (4 female) who ascended Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. This group had a median age of 29 years (range 25-60 years). They ascended rapidly, using the Machame route from a starting height of 1,800m to the summit at 5,900m, over a 4-day period.

Their total ascent was therefore 4,160m, and the average cumulative height gained each day was 1,040m, with no rest days and no descent on the way to the summit. They then descended back to 1,740m over a further day. They camped and required four season sleeping bags to cope with night-time low temperatures of -7C. The ascent profiles for both routes are available under supplementary materials.

All symptoms, signs and medication were recorded by a physician (CK). Polyuria was defined as the passing of >2.5L urine over 24 hours, but practicalities prevented an objective assessment of this while trekking. Hence daily urine volumes were estimated by everyone with reference to frequency and duration of micturition. The AMS score for each individual was calculated from the recorded symptoms using the 2018 modification of the Lake Louise score, classifying mild AMS as a score of 3-5, and moderate AMS as a score of 6-9 [

18].

Each person’s pulse oximetry and heart rate (HR) was measured every 500m of ascent, with the highest of three readings for oximetry and the lowest of three readings for HR all recorded using a finger probe (Oxypulse, Ecomerzpro, Madrid, Spain). Again, the highest altitude at which recordings were taken was 5,300m. On this trek, systolic blood pressure (SBP) was also measured each evening at 6pm using an automatic sphygmomanometer (Vital Track, Blue Ocean Company Ltd., Lancs., UK) and the lowest of three readings was recorded. Participant enjoyment of each trek was assessed on a simple Likert scale from 0 (worst experience) to 10 (best experience) after descent and the mean results compared.

2.4. Group Comparisons

The weather was dry, stable and free of significant windchill for each of the expeditions with equivalent daytime temperatures peaking at 16C on both trips. Participants were comparable between the two groups in terms of racial origin, male to female ratio, age and body mass index, training and preparation. All but one participant in each group was Caucasian or Asian. All participants had trained for over 3 months at altitudes between sea level and 1,000 m, exercising at least thrice weekly for a minimum of 30 minutes. All females were premenopausal and none of the subjects in either group had lived at an altitude of above 1,000 m in the decade prior to the expeditions described. The SPSS software package program (IBM) was used for statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the data were not normally distributed and hence comparisons were made by modified ANOVA testing between data sets within each group using the Wilcoxon signed rank test, while those between groups were made using the Kruskal Wallis test. Significance was expressed at the p=0.05 level. All trekkers in both groups provided informed consent to the collection and use of their physiological and pharmacological data, both as a means of monitoring their well-being during the treks, as well as for the purposes of writing this paper. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre in Moshi.

3. Results

All of those in Groups 1 or 2 met inclusion criteria, and none met exclusion criteria. Neither the trek to Everest Base Camp, nor to Kilimanjaro summit, required any significant technical expertise, and the mean daily distance covered in each was very comparable at 11 km. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age or gender mix. All members of both groups completed the treks, and none of the trekkers had established prior cardiorespiratory disease.

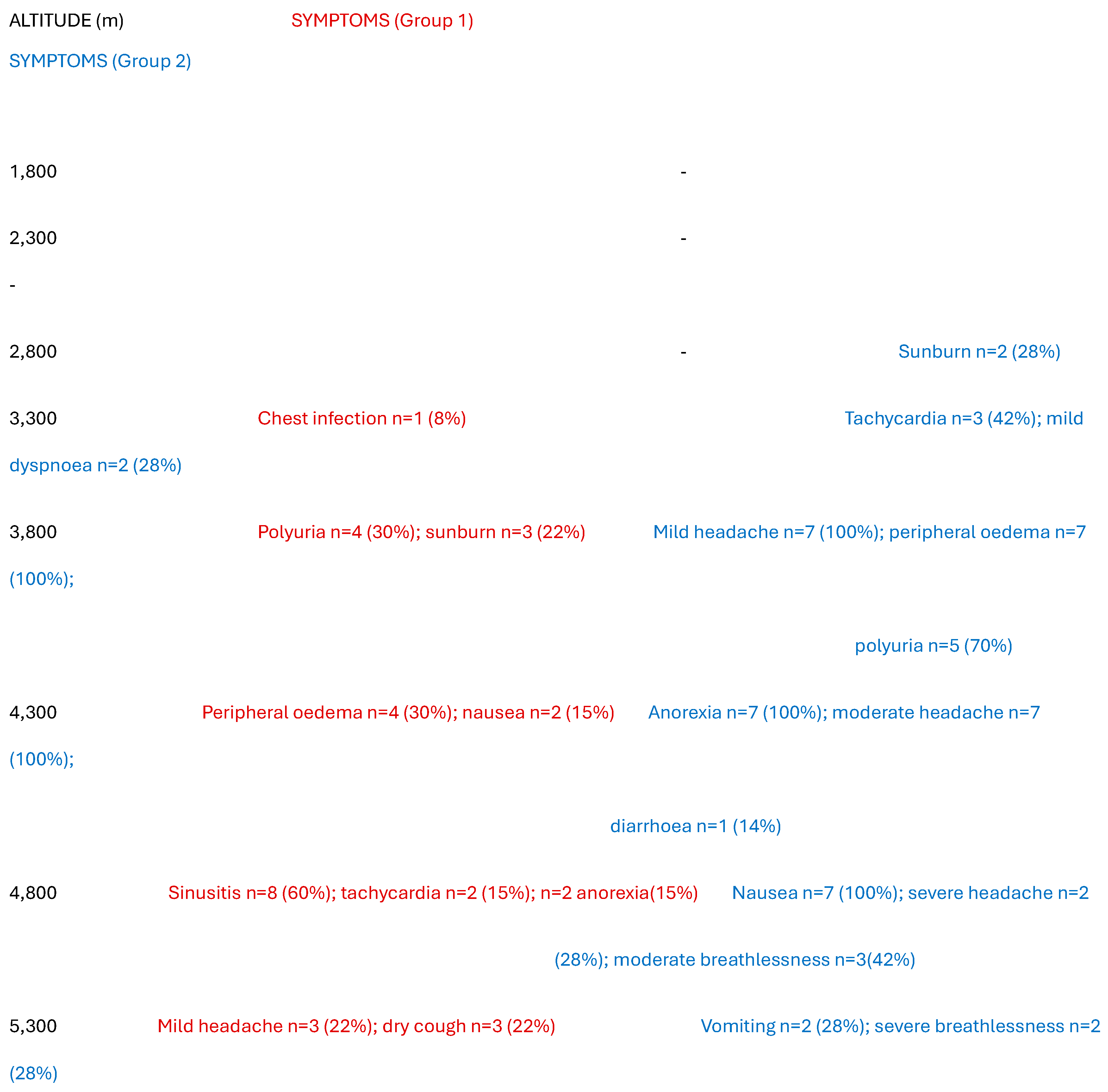

Table 1 compares the symptoms experienced by both groups. None of Group 1 in Nepal met criteria for AMS. The main symptoms reported by members of this group were mild headache, fast heart rate, sunburn, sinusitis and a dry cough. The latter two symptoms were not reported by five people who wore masks to minimise dust inhalation. Four also exhibited mild peripheral oedema, affecting the hands, feet and face, above altitudes of 4,000m. Polyuria was also reported by four and was a significant inconvenience, especially at night. Symptoms reported by Group 2 in Tanzania were much more significant. Two people had severe headache, and one had recurrent vomiting with abdominal pain and became dehydrated. Five had polyuria and all reported anorexia and nausea, with moderate headache and some breathlessness. Five (70%) met criteria for mild AMS, while two (30%) met criteria for moderate AMS. The median peak (range) AMS score in Group 1 was 1 (0-2) which was significantly lower than that in Group 2 at 4 (3-6) [H-stat=20, p=0.0031]. All members of Group 2 developed peripheral oedema. Neither age nor gender were correlated with any outcome measures. Barometric pressures at the latitude of Kilimanjaro and Everest are similar up to 5000 meters [

19].

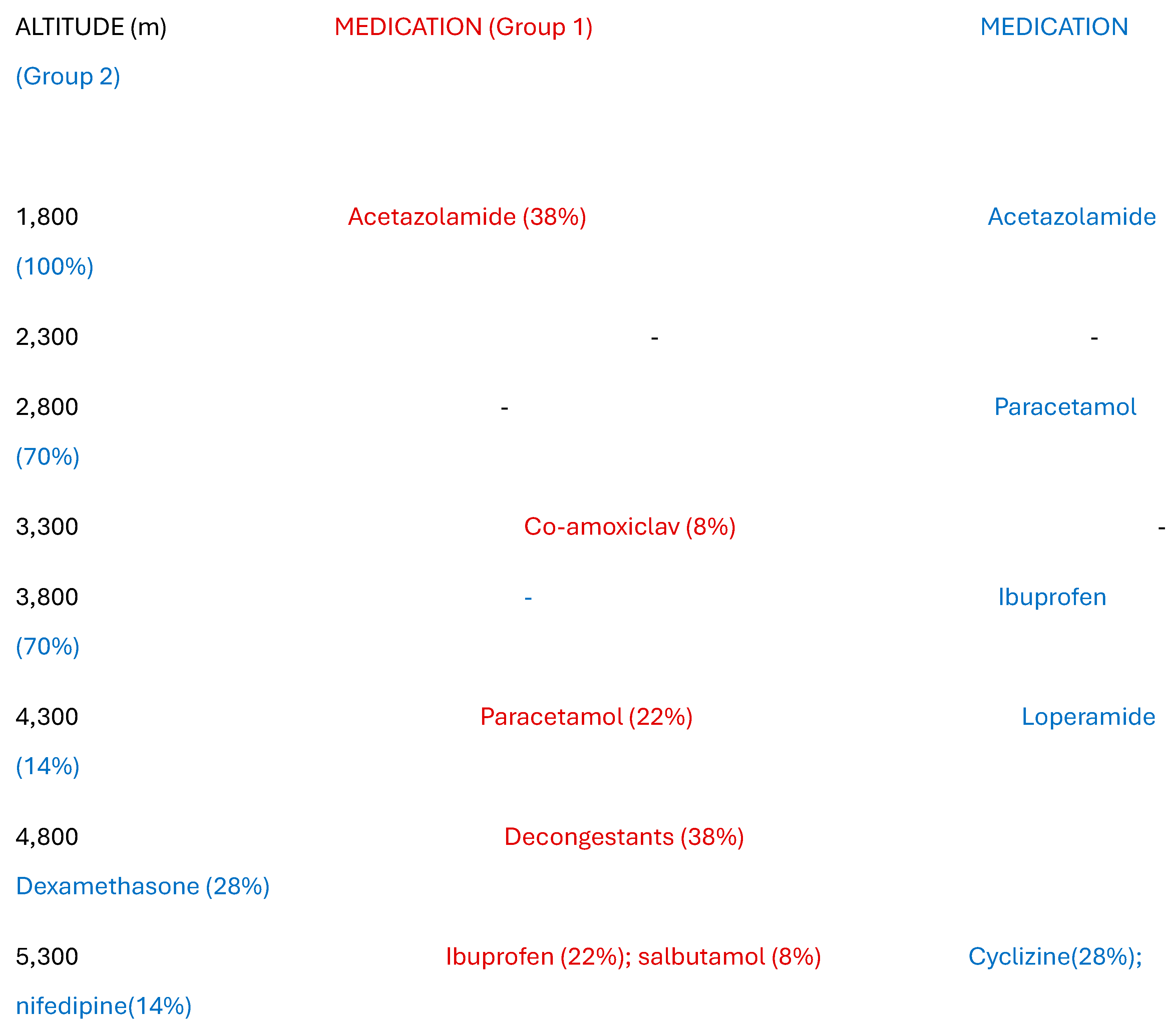

Table 2 records the medication required by each group. Five of Group 1 chose to use low dose acetazolamide prophylaxis, and a further three were advised to use ibuprofen for symptomatic relief. One person was given a course of antibiotics for a chest infection, and five required decongestants for sinusitis. By comparison, all of Group 2 took prophylactic acetazolamide and five needed additional ibuprofen for persistent symptoms. Two were administered low dose (2mg) dexamethasone and one needed nifedipine (20mg). No-one required oxygen but the rapid descent was mandated because of the severity of symptoms at the summit. Polyuria was associated with taking acetazolamide, occurring in 9 out of 12 (75%) of climbers on this agent across both groups. Group 1 participants generally rated their experience as more enjoyable than did those in Group 2 (7.9 versus 6.7).

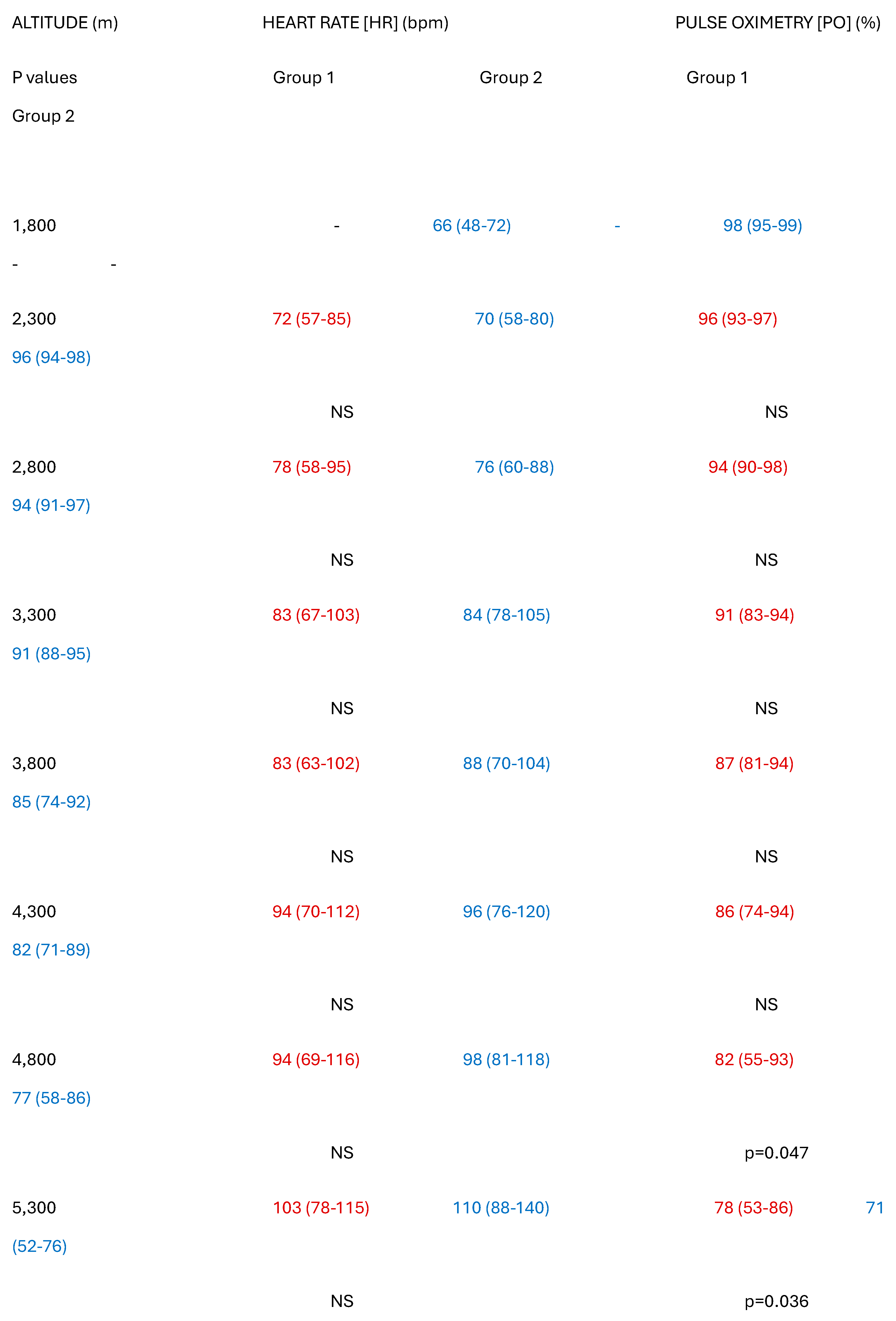

Table 3 shows the results of the physiological measurements undertaken. In Group 1, baseline oximetry fell from a median of 96% (93-97%) at 2,300m to a median of 78% (53-86%) at 5,300m 8 days later [R1=91; p=0.0001] but recovered to 94% (89-99%) inside 4 days on returning to 2,860m. Corresponding HR rose from a baseline of 72bpm (57-85bpm) to a median of 103bpm (78-115bpm) at 5,300m [R1=98.5; p=0.0001], then recovered to 80bpm (54-94bpm) after 4 days on returning to 2,860m. Neither age nor sex correlated with outcomes. Individually, HR correlated inversely with oximetry, but there was no group correlation between these two variables. By contrast, in Group 2, baseline oximetry fell from a median of 96% (94-98%) at 1,760m, to a median of 71% (52-76%) at 5,300m at 4 days [R1=77; p=0.001], but recovered to 95% (92-98%) inside one day on descending to 1,800m. Corresponding HR rose from a median baseline of 70bpm (58-80bpm) to a median of 110bpm (88-140bpm) at 5,300m after 4 days [R1=77,p=0001], then recovered to 80bpm (54-94bpm) after a day on returning to 1,760m. Again, neither age nor sex correlated with outcomes. SBP rose from a median of 122mm Hg (98-138mm) at baseline to a median of 164 mm Hg (139-198mm) at 5,300m [R1=28; p=0.001] but returned to normal slowly over five days. No residual neurological features were noted after descending and careful screening showed no evidence of retinal haemorrhages in any of the group the day after descent. Everyone in both groups experienced complete resolution of symptoms within 48 hours of returning to starting height. There were no long-term sequelae in any participants, and interestingly there were no differences in symptoms or oxygen saturation between those who took acetazolamide and those who did not.

Although the rises in HR from baseline to 5,300m altitude were highly significant in both groups, the difference between the two groups in the degree of change in HR did not quite meet statistical significance [H stat=4.31, p=0.061]. The falls in oxygen saturation were also highly significant in each group, but the degree of reduction in pulse oximetry was significantly greater in the Group 1 than in Group 2 [H stat=13.5, p=0.013].

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to compare pulse oximetry during fast and slow ascents to the same altitude by equivalent groups using the same protocol. Although our group sizes were small, the time of year, group composition and the conditions experienced, were all very similar. Despite the small numbers, a significant difference in oxygen saturation was found between fast and slow ascents, confirming what had previously been predicted by other authors. In the only other study to directly compare fast and slow ascents to very high altitude, reported 15 years ago, the differences in rate of ascent were less marked than in ours, oximetry was not measured, and between-group differences were primarily assessed using an estimate of severity of AMS [

1], prior to the 2018 criteria reclassification [

20]. We also found a significant difference in AMS scores between fast and slow ascenders. The number of climbers within the slow ascent group in the 2009 study was comparable to ours, emphasising how difficult it can be to undertake large, controlled studies at very high altitude while ensuring both participant safety and scientific validity.

Prolonged survival at altitude is certainly possible but the highest altitude at which people have been recorded as living long term is at 5,100m [

21], although over 80 million people live at altitudes above 2,500 metres [

22]. Different populations have evolved different adaptations to living at high altitude with genetic changes resulting over time [

23]. Indigenous inhabitants not only survive but can thrive at high altitude because of evolutionary changes in their respiratory and cardiovascular systems [

24,

25]. Adaptation to altitude leads to genetic advantages such as larger lungs [

26]. Residents of the Andes exhibit polycythaemia [

27], while Himalayan inhabitants compensate via increased ventilatory rates and cerebral blood flow [

28] which together reduce the risk of AMS [

29]. The chance of developing cardiovascular disease [

30] is also reduced among those who live at high altitude.

Hypothermia (a body core temperature of below 35.0 C) is a constant threat at any altitude, but the risk rises with increasing distance from the equator. During the climbing season, the mean temperature at the summit of Everest is -26.0 C [

31]. Hypothermia may produce confusion [

32], which can evolve to hallucination and a false perception of warmth, leading to some climbers taking off their jackets [

33] with fatal consequences. The risk of dehydration is accentuated by breathing cold air as moisture from the upper airways is required to warm inhaled air to body temperature [

7]. Conversely sunburn is also very common at altitude because of increased ultraviolet light in the thin atmosphere [

34]. Severe sunburn can accentuate nausea and fatigue and may accelerate fluid loss in the case of severe skin damage [

35]. Both hypothermia and hypoxia are more likely to develop in those who visit high altitude areas, rather than in those who reside there permanently. The lower mean temperatures experienced by the slow ascent group may have protected them from excessive fluid loss by comparison with the fast ascenders in our study, but the conditions in both geographic zones are greatly influenced by the time of year at which the treks are undertaken.

Hypoxia is the main factor in the development of acute altitude illness which can be separated into three related categories: AMS, HAPE, and HACE [

36]. AMS is the most common and diagnosis is based on recent ascent to high elevation with the development of headache in all sufferers, typically accompanied by anorexia, fatigue, insomnia or nausea. These symptoms usually develop within 12 hours of ascent to an elevation above 3,000m and often develop overnight. The presence and severity of AMS is quantified by the Lake Louise score [

20] and offers a useful comparison between both individuals and groups, as well as the effect of the speed of ascent. In this study, the individuals in each group were well matched which allowed for a comparison of the effects of fast versus slow ascent on the prevalence and severity of AMS. The prevalence of AMS increases with altitude and typically affects just 7% at 2,200 m but as many as 52% at 4,560 m [

37]. Younger people appear more susceptible to AMS [

38], as do females [

39]. This study showed a much higher prevalence of AMS in the fast ascent Group 2.

Mild AMS usually resolves within a day if trekkers do not climb any higher [

40]. It is usually self-limiting but can be treated with paracetamol or ibuprofen. Acetazolamide facilitates acclimatisation and can be used to treat AMS, but it is more typically used as a prophylactic agent. It causes a bicarbonate diuresis with a metabolic acidosis, increasing ventilatory drive and oxygenation [

41]. It accelerates acclimatisation and reduces periodic breathing, which is common at night over 4,000 m. It may induce polyuria and paraesthesia of extremities. A dose of 125 mg twice daily, starting one day prior to ascent and continuing until descent commences, reduces the probability of developing AMS. This can be administered at the treatment dose of 250mg BD if AMS occurs in climbers not already taking it [

5,

42]. In more severe cases of AMS, dexamethasone is effective in providing rapid symptomatic relief [

43]. In the most severe cases, oxygen supplementation provides immediate benefit but must be combined with a prompt reduction in height of at least 300m [

44].

The incidence of severe AMS among all trekkers on Kilimanjaro has been shown to be 8.6% with over 1% of all climbers hospitalised [

45]. An earlier study of 130 Finnish trekkers reported a prevalence of at least mild AMS of 75%, and a summit success rate of under 50% [

46]. More serious manifestations of altitude illness may occur above 4,300m, with a rough incidence of HAPE occurring in 1% of climbers [

47]. It typically manifests as a productive cough with frothy phlegm and associated dyspnoea at rest. In severe cases, sputum is often blood-stained. Oxygen saturation falls dramatically, and oximetry shows levels at least 10% below those recorded by healthy people at the same altitude, with values invariably below 70% and often much lower [

48]. The commonest cause of death among trekkers on Kilimanjaro is HAPE [

49]. Urgent descent is mandatory, with the use of supplemental oxygen if available. Nifedipine has long been known to be effective in preventing or reducing pulmonary oedema in the short term but does not replace the need for oxygen and descent from altitude [

50]. Less common is HACE, which may be triggered by the worsening hypoxia associated with HAPE [

51]. HACE is a medical emergency and may lead to confusion, drowsiness, and coma [

52]. Urgent descent is mandated, along with the use of dexamethasone and oxygen, where available. Low dose dexamethasone also helps prevent HACE in susceptible individuals [

53] and can save lives [

54].

In keeping with previous work [

55], our study showed that a gradual ascent to 5,300m over 8 days, incorporating two rest days where we slept at the same altitude, was associated with significant benefits when compared to a rapid ascent over 4 days without taking time to acclimatise. Guidelines on safe ascent rates have been published [

56] and evaluated [

57]. None of the slow ascenders in our study developed features of AMS, while all of those in the fast ascent group developed symptoms of at least mild AMS, with one person (14%) also exhibiting features of early HAPE. Achieving fluid balance posed a challenge for many climbers. Drinking adequate volumes of fluid to prevent dehydration was offset by the unwanted developments of either peripheral oedema from fluid retention, or polyuria from reduced ADH secretion and acetazolamide use in many trekkers. Acetazolamide is a diuretic and therefore accentuates polyuria. Acetazolamide was used less by slow ascenders (35%) than by fast ascenders (100%), as were both ibuprofen and paracetamol, which would suggest that without these agents, differences between fast and slow ascenders with regards to AMS scores and possibly physiological adaptation, might have been even greater. The use of nifedipine and dexamethasone was confined to the fast ascent group, and it is possible that a degree of dehydration might offer some protection against both HAPE and HACE. Oxygen saturations were significantly higher among those who ascended slowly, and this group also exhibited slightly lower pulse rates. Overall, those who ascended slowly adapted more effectively to increasing altitude and reported a more comfortable and enjoyable experience. These findings support those previously published, showing greater problems among trekkers in Africa than Asia [

58].

Limitations of our study include the small uneven numbers in each group. However, these were matched as closely as possible for age, gender, and baseline fitness. Furthermore, weather conditions, temperatures and the terrain were very similar for both expeditions. Despite the small numbers, our findings did demonstrate significant differences in outcome between the groups. A further methodological flaw was the lack of objective assessment of urinary volumes. A major strength is the direct comparison of fast and slow ascents by age- and gender-matched groups using objective measures under similar conditions at the same altitudes.

Key messages

Acute mountain sickness is commonly associated with rapid ascent to altitudes of 5,300m

Graduated ascent with rest days to allow acclimatisation reduces the body’s physiological burden

Gradual rather than rapid ascent is associated with fewer symptoms and less need for medication