1. Introduction

Pain is one of the most frequent causes of medical consultation with the most common cause in diseases of the musculoskeletal system [

1]. It represents a primitive stimulus in humans and its importance in biological function is to provide a warning or alarm signal in the event of an injury, illness, or other noxious phenomenon [

2]. This signal is originated by nociceptive stimuli that are detected by free nerve endings and is transported by type Aδ and C neurons that may include myelination and are both slow-conducting fibers [

3].

Pain generates a deterioration in the quality of life of the people who chronically suffer from it. Despite being an important and frequent symptom, an adequate evaluation of pain concerning its intensity, functional impact, and possible etiology is needed in order to decrease its clinical burden [

4]. Thus, methodology for a holistic assessment of pain can improve the quality of life in patients, as measured by changes in the quality of sleep as one potential output [

5]. Pain could also have an emotional and social impact, altering daily life, and can impact other pathologies. When evaluated systematically, pain symptoms could allow for early detection and prevention of many diseases.

In high altitude regions, the decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen in inspired air (PIO₂) produces a decrease in the ability of tissue cells to receive and use oxygen effectively. This state of hypoxia occurs at many different levels both physiological and biochemical [

6]. Previous studies showed that during the early stages of adaptation to high altitude, changes in sensory perception occur [

7]. An immediate decrease in the threshold of 25 - 40% has been observed in various senses, including touch, carbon dioxide sensitivity, color and light perception, taste, and smell, when subjects ascend to an altitude of more than 3,400 m. This apparent decrease in sensation is reversed by supplemental oxygen administration [

8]. However, sensory thresholds, and particularly pain threshold, can be strongly biased by ethnocultural, attentional, motivational, and genetic factors. A previous study on the effect of pain during altitude acclimatization reported that sensitivity is lower in people living at high altitudes compared to those in the lowlands (Hamed, 2016). The perception of simulated painful situations is also lower in the lowland population compared to a population at high altitudes subjected to the long-term effects of chronic hypoxia [

7]. On the other hand, during an expedition to the Bhrikuti Peak in the Himalayas (6,460 m), a decrease in the pain threshold compared to the control group at sea level was observed due to the improvement of sensory discrimination in a normoxic environment [

9].

Although several studies suggest the mechanisms of how the human body adapts to high altitude, the specific impact on pain perception, especially in the severe hypoxia of high altitude locations (e.g. La Rinconada), remains largely unknown. La Rinconada is a city located at more than 5,100 m altitude and is considered the highest place of permanent residence in the world [

10,

11]. An understanding of how hypoxia impacts pain perception would improve theragnostic approaches to patients suffering from pain regardless of the altitude. In this study, we hypothesize that pain perception could be different in the high altitude of La Rinconada compared to a lower altitude environment. In this study we evaluated pain perception in a group of young subjects who live at 3,800 meters and the changes that occur in pain perception when they are exposed to a severe hypoxic environment of more than 5,100 meters.

2. Materials and Methods

Study population: Fourteen subjects (7 males and 7 females) residing in Puno at 3,825 m above sea level participated in this study. The individuals ascended to the Populated Center of La Rinconada, located at an altitude of more than 5,100 m. All subjects were healthy with no history of diseases or conditions that could alter the perception of pain.

Procedure: The initial evaluation of the subjects was done in Puno and a second evaluation was performed in La Rinconada. The following data were recorded: age, sex, weight, height, and body mass index. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR) were registered using a Ri-Champion digital blood pressure monitor (Rudolf Riester GmbH, Jungingen, Germany) with a measuring range of 30 to 280 mm Hg for blood pressure and a range of 40 to 200 beats per minute for heart rate. SatO2 was measured with a NELLCOR® OXIMAX® N-65 pulse oximeter (Digicare Biomedical Technology Inc, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) with a saturation resolution of 1% and a heart rate range of 30 to 235 beats per minute. Capillary blood samples were obtained from the pad of the finger of each participant. A puncture was performed with a sterile lancet to absorb a drop of blood in a microcuvette. The hemoglobin was measured with a Hb-201 hemoglobinometer (Hemocue, Ängelholm, Sweden), using the azidimethemoglobin method within a measurement range of 0 to 25.6 g/dl. Hematocrit (Hct), was measured in a HemataStat II microcentrifuge (EKF Diagnostics, Penarth, UK) on blood samples obtained by a fingertip puncture.

Measurement of pain tolerance (Tourniquet ischemic test):

Ischemic pain is elicited by the ischemic handgrip exercise (20 times) of the subject after a tourniquet is inflated around the upper arm. The quality of sensation is dull-aching or stinging muscular pain, which closely resembles most types of pathologic pain, but increases progressively after cessation of squeezing. Test performance is measured in terms of elapsed time between cessation of squeezing and report of slight (threshold) and unbearable (tolerance) pain. Muscular pain from ischemic contractions, which is due to transient stimulation of peripheral nociceptors [

12], is based on the algogenic actions of protons [

13]. The ischemia procedure was performed as previously described [

14]. In brief, the patient is in a sitting position with the arm resting on a table. The arm remains at the same level as the heart to place the manual blood pressure monitor with the lower edge 2 cm above the bend of the elbow. The cuff was insufflated up to 200 mmHg. Then the patient opens and closes their hand rhythmically, whereas the evaluator records with a stopwatch the times of pain onset, when the pain becomes unbearable, and when the pain disappears. These timing data also allow us to calculate the exasperation time (Exasperation = Unbearable – Onset) and the resolution time (Resolution = Disappearance – Unbearable). Additionally, during this procedure, both heart rate and oxygen saturation were measured. This test was performed on both arms.

Statistical analysis: The data are represented as the mean with its standard deviation. Normality distribution of datasets was determined with the Shapiro-Wilk test, which resulted in all variables showing a normal distribution. Simple linear regression was calculated between some pairs of variables. Data processing was performed using the IBM SPSS statistical package version 26.

Ethical aspects: Prior to the study, each participant received detailed information about the procedures and the objectives of the investigation. All the subjects signed an informed consent form before participating in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de San Martin de Porres with FWA International Registry for the Protection of Human Subjects No.00015320, IRB No. 00003251.

3. Results

Fourteen subjects with similar characteristics were evaluated and divided into two groups (n=7) according to gender. The BMI of the subjects was 22.6 ± 1.2 and the average age of the participants was 23.3 ± 1.9 years.

As expected, 24 hours after arrival at 5,100 m a significant increase in Hb (about 1g/dL) and Hct (approximately 4%) were evidenced. Also, statistically significant increases in SBP and DBP and a decrease in SatO

2 were observed (

Table 1). Concerning the pain perception in the right arm, the onset tended to be slightly sooner at 5,100 m for approximately a half second (non-significant difference), and the pain sensitivity dynamics were similar between the two altitudes (

Table 2). In the left arm, we found similar results, although the time of pain onset tended to be longer at 5,100 m (non-significant difference), whereas the exasperation time was significantly sooner at 5,100 m (

Table 3). Strikingly, the resolution time was significantly longer at the higher altitude for the two arms.

It is known that the ability to perceive pain presents differences associated with gender, for that reason we disaggregated the data for men and women. Apart from the already-known differences between genders for hematological parameters and peripheral arterial saturation [

15], we also observed that both SBP and DBP were slightly higher in men at both altitudes (

Table 4). Minimal differences were observed in relation to the time of exasperation at both altitudes in relation to gender, in both cases the difference was minimal, as well as in the resolution time of pain (

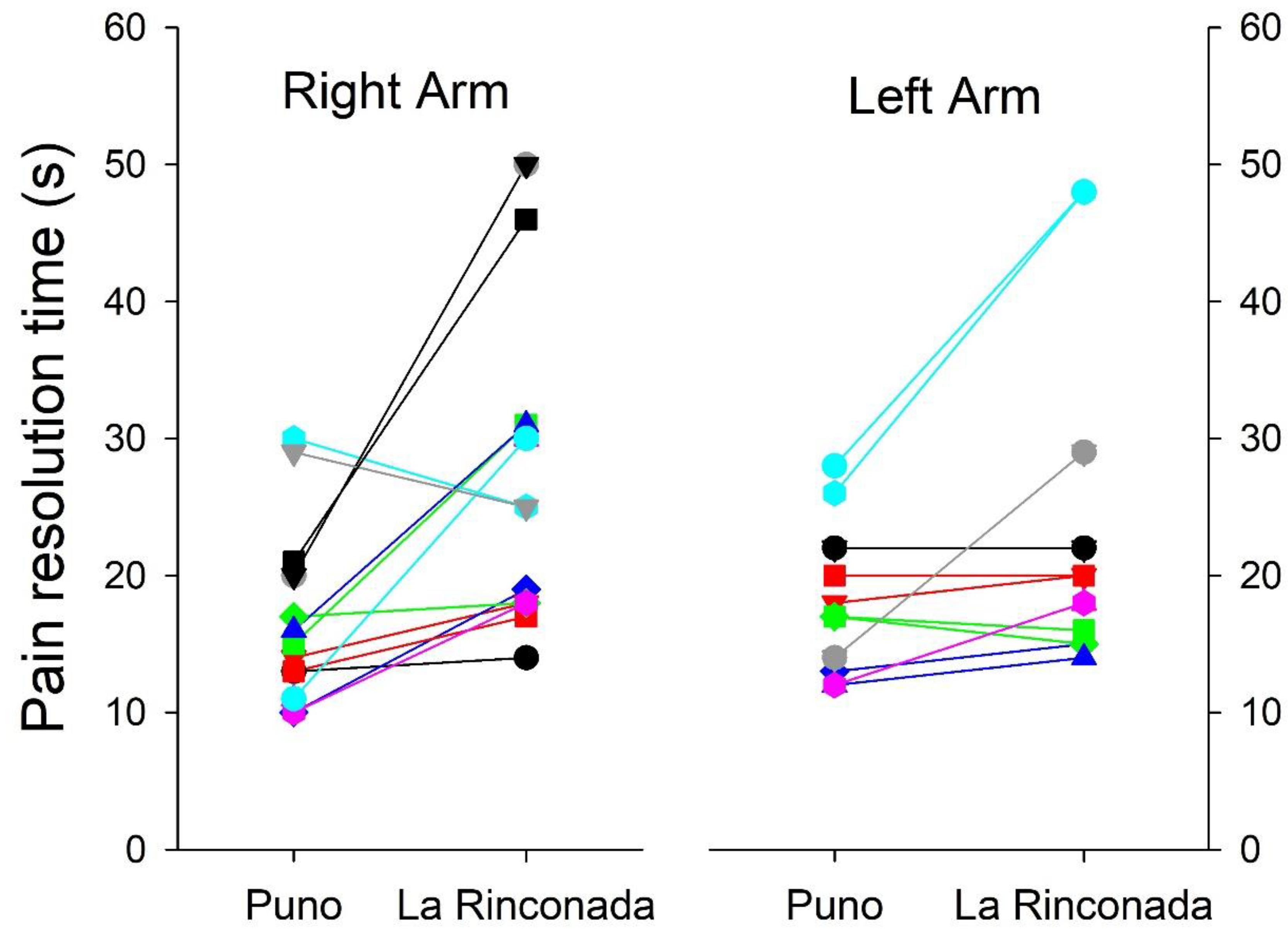

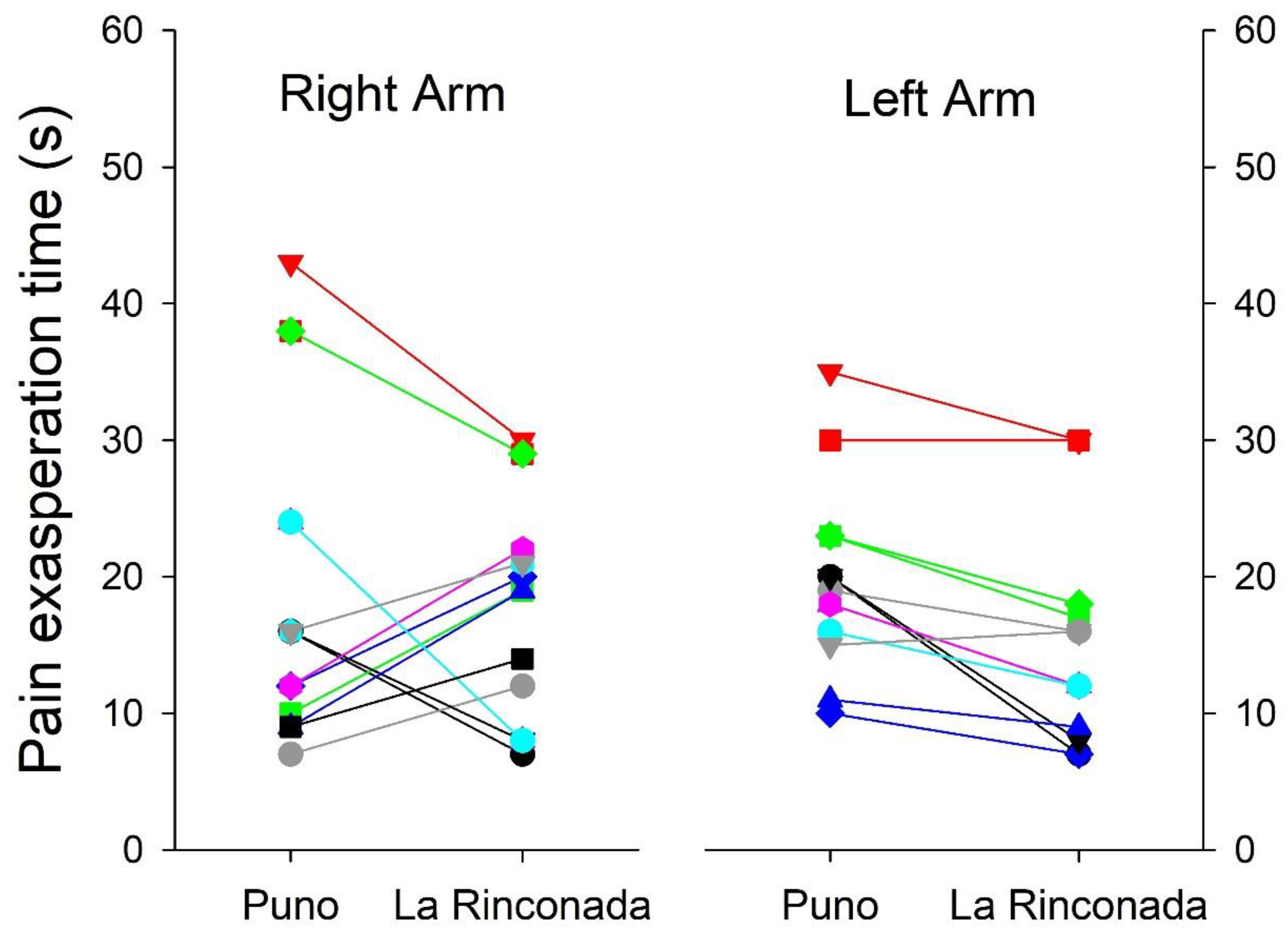

Table 5). However, we must mention that a bimodal behavior is observed, the response both in exasperation time and in resolution time is not uniform, thus indicating the existence of at least two marked patterns in the individual differences to pain tolerance (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Minimal differences were observed in pain perception at both altitudes, such as earlier delivery in the left arm at both altitudes, shorter excruciating pain in women at 3,800 m, and longer duration in women at 5,100 m (

Table 6). Minimal differences were also observed in the exasperation time and the resolution time at both altitudes.

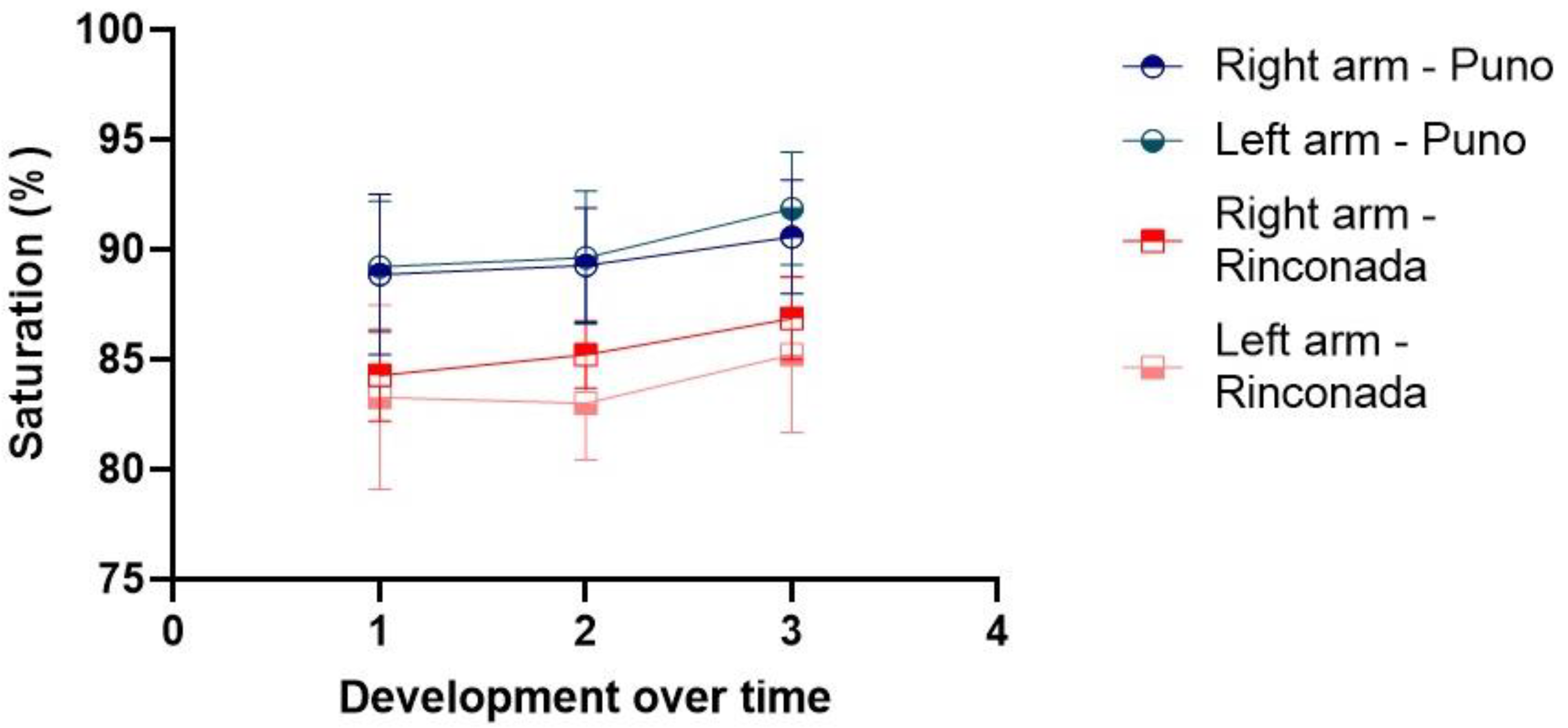

Figure 1.

Changes in oxygen saturation during the pain treshold test at the two altitudes on the right and left arms. Labels for X-axis are: time of first pain (1), unbearable pain (2) and no pain (3).

Figure 1.

Changes in oxygen saturation during the pain treshold test at the two altitudes on the right and left arms. Labels for X-axis are: time of first pain (1), unbearable pain (2) and no pain (3).

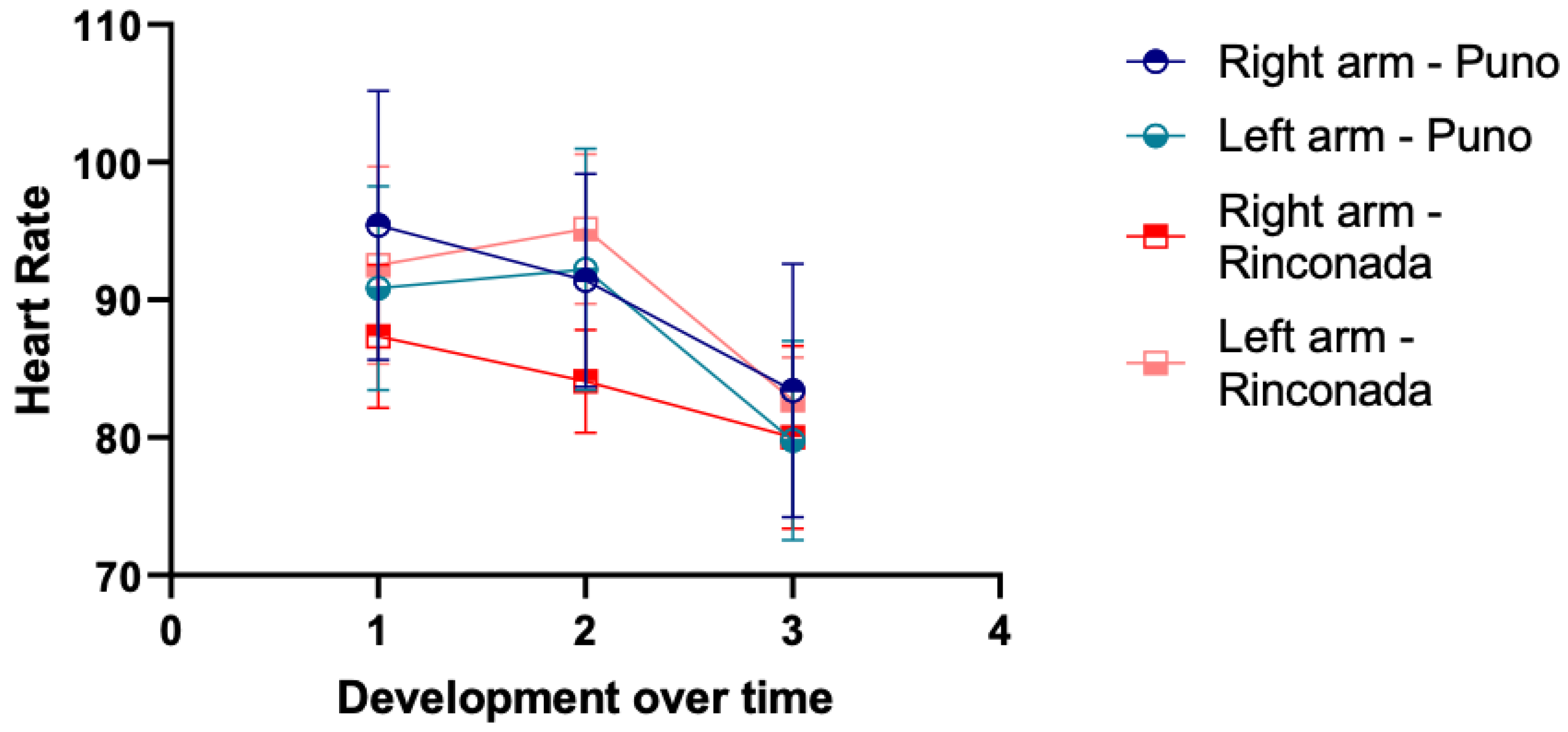

Figure 2.

Heart rate changes during the pain threshold test at the two altitudes on the right and left arms. Labels for X-axis are: time of first pain (1), unbearable pain (2) and no pain (3).

Figure 2.

Heart rate changes during the pain threshold test at the two altitudes on the right and left arms. Labels for X-axis are: time of first pain (1), unbearable pain (2) and no pain (3).

Figure 3.

Individual changes in pain resolution time between the two altitudes in both arms.

Figure 3.

Individual changes in pain resolution time between the two altitudes in both arms.

Figure 4.

Individual changes in pain exasperation time between the two altitudes in both arms.

Figure 4.

Individual changes in pain exasperation time between the two altitudes in both arms.

4. Discussion

Pain is an unpleasant sensation where perception depends on the degree of injury and the speed of neuronal conduction [

2]. Approximately 50% of patients go to the doctor's office presenting some type of pain, having chronic pain a prevalence between 20% and 40% [

16], thus occasioning a serious impact on their quality of life. An adequate and holistic assessment of pain is often not part of the clinical routine assessment. In addition, the intensity and capacity of perception can vary depending on the environment, social, and genetic factors [

17]. Among the environmental factors that could influence pain perception are environmental temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, and wind. An additional factor that can heavily influence pain perception is hypoxia, since the lower availability of oxygen could alter the perception [

18] through mechanisms that are yet to better understood.

In the present study, a total of 14 young people of both sexes have been evaluated. With a mean age of about 23 years, the subjects reside at an altitude of 3,800 m and were subsequently exposed to a hypoxic environment at 5,100 m. The objective of the study was to evaluate whether or not there are changes in the sensory perception of pain when exposed to an acute hypoxic environment. Baseline measurements were made at their place of residence and subsequently at 5,100 m after 48 hours of staying in this environment. An increase was observed in SBP, DBP, Hb and Hct while there was a decrease in SatO

2 and HR (

Table 1). The slight changes observed in these variables are due to the process of acclimatization to the severe altitude of La Rinconada [

19]. No other changes affecting the health conditions of the individuals studied were reported. No differences have been observed concerning gender as both men and women presented similar findings (

Table 5 and

Table 6). These results differ from a previous study that found differences in pain tolerance associated with gender indicating that women have a better tolerance [

17].

The time elapsed from the moment in which the tensiometer cuff began to be inflated and pressure was slightly greater at 3800 than 5100 m (

Table 4); however, these parameters were not statistically significant, It could also be due to the bimodal behavior both in relation to the exasperation time and the resolution time as observed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, these differences could be due to genetic, or psychological factors, since this bimodal behavior is observed in both sexes, since the perception of pain presents differences in relation to mainly genetic factors, which could cause this difference [

20]. On the other hand, we must highlight that the transmission of the nervous impulse in a very short period of time. Yet this initial change shows us that at higher altitude, the transmission of the painful impulse is delayed in relation to the perception of unbearable pain. The exasperation and pain resolution times were slightly less at 5,100 m compared to 3,800 m. This suggests that the hypoxic environment could be conducive to a greater capacity to perceive pain. These findings coincide with previous studies, which showed a decrease in pain threshold by up to 40% [

7]. In this report, it was also observed that the increase in pain perception is also related to other stimuli, such as the decrease in touch and smell sensation after the administration of oxygen. Nonetheless, our study is supportive of the hypothesis that hypoxia can alter the pain perception. Mechanistically, this could be due to oxygen bioavailability and differences in nerve impulse conduction when a subject is exposed to a hypoxic environment. This supposition requires further testing. Also, the individual difference between both arms in the evolution of heart rate and arterial saturation during the tests is striking (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) without this behavior being attributable to gender or laterality in dexterity.

Changes in SatO

2 and HR have been evaluated during the procedure (

Table 4), which showed an increase relative to basal conditions. This increase was progressive and in the same proportion and is probably due to pain stimulating an increase in the respiratory rate. The proportional changes in SatO

2 and HR during the procedure were lower at 5,100 m compared to at 3,800 m and might be related to the lower barometric pressure [

17]. Hypobaric hypoxia may coincide with the different phases of pain stimulation by the cuff pressure as it relates to breathing. Similar relations were observed with heart rate where a progressive decrease was observed with the lowest value observed at the end of the test. These results are contrary to the physiological changes inherent to the painful stimulus that would normally increase heart rate [

17]. These results are also contrary to reports of a lower speed of neuronal transmission that would allow delayed transmission of painful sensations to the autonomic system without immediate changes in vital signs. It is necessary to mention that the pulse oximeter was placed on a finger of the hand that was not involved during the procedure, preventing the pressure exerted by the cuff from generating these changes.

One of the mechanisms for better pain tolerance in acute hypoxia is related to the changes in neurotransmitters. An increase in catecholamines could help improve tolerance to pain since previous studies showed an increase in catecholamines of up to 36% during exposure to 4,300 m [

20]. An increase of up to 99% in the arterial concentration of adrenaline was also determined during acute exposure which subsequently decreases [

21]. The increase in these neurotransmitters could generate a greater tolerance to pain, as has been observed in this study. Additional mechanisms could be related to the cardiovascular system induced by the autonomic nervous system. Previous studies reported tachycardia at high altitudes [

22]. However, we have observed a slight decrease in basal HR at the higher altitude, a finding that does not coincide with the results obtained in these studies, which may be due, at least to some extent, to the fact that the subjects were all natives of high altitude. Tachycardia is due to a muscarinic effect. Thus, muscarinic blockade at rest and during physical exercise could reduce HR. In our study, the decrease in HR could be explained by a previous basal adaption to a moderate hypoxic environment prior to the test. It is also known that residents of high altitude regions have hyposensitivity to pain in the cardiovascular system in hypoxia and a hypersensitivity to parasympathetic stimulation, allowing the subjects to have a decrease in HR [

23,

24,

25].

In this study, the accuracy of time measurement in seconds was a limitation that may have prevented the detection of small differences. Although many parameters did not reach statistical significance, the data suggest the need for a larger sample size and additional complementary approaches. Furthermore, the method used to assess pain tolerance is straightforward and does not require expensive, sophisticated instruments. It can be performed by trained health personnel and is easy to interpret, making it a potentially useful tool. While this method may not be ideal for clinical practice, it could be valuable for evaluating apparent pain tolerance. Despite the limitations, we observed that a severely hypoxic environment can potentially influence nervous pain transmission since the nervous system is highly dependent on oxygen [

24]. We also emphasize the importance of carrying out similar studies on subjects living in a severely hypoxic environment compared to subjects that live permanently at sea level, as the magnitude of pain perception could be different between sea level and high altitudes.

5. Conclusions

The pain threshold seems to be slightly higher during exposure to a hypoxic environment; however, no statistical significance was observed. In addition, no differences in the threshold of pain were observed between men and women.

6. Limitations

The Puno residents may have already been pre-conditioned to a moderate hypoxic environment before the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the authorities of La Rinconada, the Miners Association, and all the institutions that promote permanent health control in this place. We also thank the study participants for their time and willingness to collaborate.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: K.M.V.C., L.L.S, and I.H.; methodology: K.M.V.C., R.A.R.C, J.T.F., and V.V.; formal analysis: K.M.V.C., J.T.F.,L.L.S., and I.H.; investigation: K.M.V.C, R.A.R.C, J.T.F, H.O.T.R., M.M.Q.T., S.A.Q.H., A.G.C.H., and I.H.; resources: G.V., A.A.S.G., and I.H.; data curation: K.M.V.C, R.A.R.C, J.T.F, H.O.T.R.,A.F.P., L.L.S., and I.H.; writing original draft preparation: K.M.V.C., J.T.F., , G.V. and I.H.; writing review and editing: K.M.V.C., J.T.F., M.Y.,A.F.P. and I.H.; visualization: K.M.V.C., J.T.F., G.V., and I.H.; supervision: J.T.F. and I.H.; project administration: I.H.; funding acquisition: G.F.P.V., A.A.S.G.,G.V., and I.H. All authors have read, reviewed, and agreed to the published version of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding statement

M.Y. is supported by the National Institute of Health National Heart Lung and Blood grant R00 HL164888.

References

- Elliott AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Cairns Smith W, Alastair Chambers W. The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet. 1999;354(9186):1248-52. [CrossRef]

- Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3760-72. [CrossRef]

- 3. Di Maio G, Villano I, Ilardi CR, Messina A, Monda V, Iodice AC, et al. Mechanisms of Transmission and Processing of Pain: A Narrative Review. IJERPH. 9 de febrero de 2023;20(4):3064. [CrossRef]

- Babarro A. La importancia de evaluar adecuadamente el dolor. Aten Primaria. 2011;43(11):575-6. [CrossRef]

- Calsina-Berna A, Moreno Millán N, González-Barboteo J, Solsona Díaz L, Porta Sales J. Prevalencia de dolor como motivo de consulta y su influencia en el sueño: experiencia en un centro de atención primaria. Aten Primaria. 2011;43(11):568-75. [CrossRef]

- Leon-Velarde, F., McCullough, R.G., Reeves, J.T., 2003. Proposal for scoring severity in chronic mountain sickness (CMS). Background and conclusions of the CMS Working Group. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 543, 339–354. [CrossRef]

- Hamed NS. Pain Threshold Measurements in High and Lowaltitude among Healthy Volunteer Adults: A comparative Study. Int J Physiother. 2016;3(6):693-699. [CrossRef]

- Virués-Ortega J, Buela-Casal G, Garrido E, Alcázar B. Neuropsychological Functioning Associated with High-Altitude Exposure. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14(4):197-224. [CrossRef]

- 9. Noël-Jorand MC, Bragard D, Plaghki L. Pain Perception under Chronic High-altitude Hypoxia. Eur J of Neuroscience. 1996;8(10):2075-9. [CrossRef]

- West JB. Physiological Effects of Chronic Hypoxia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1965-71. [CrossRef]

- Enserink M. Hypoxia city. Science. 2019;365(6458):1098-103. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Atero M. S., J. Caballero, A. Cañas, P. L. García-Saura, C. Serrano-Álvarez y J. Prieto* Valoración del dolor. Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor. 9: 94-108, 2002.

- Ricart A, Pages T, Viscor G, et al Sex-linked differences in pulse oxymetry British Journal of Sports Medicine 2008;42:620-621.

- Frießem CH, Willweber-Strumpf A, Zenz MW. Chronic pain in primary care. German figures from 1991 and 2006. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):299. [CrossRef]

- Holdcroft A, Berkeley KJ. Sex and gender differences in pain and its relief. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M; Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006. p. 1181-97.

- Gutiérrez-Giraldo G, Cadena-Afanador L del P. Breve reseña histórica sobre el estudio del dolor. MED UNAB. 2001;4(10):1-5.

- Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Gori G, Fumoso F, Gri N, Floris V, et al. Pathophysiology and therapy of high-altitude sickness: Practical approach in emergency and critical care. J Clin Med. 2022;11(14):3937. [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth R, Drinkhill MJ. Cardiovascular adjustments for life at high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;158(2-3):204-11. [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo RS, Child A, Butterfield GE, Mawson JT, Zamudio S, Moore LG. Catecholamine response during 12 days of high-altitude exposure (4,300 m) in women. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84(4):1151-7. [CrossRef]

- Boushel R, Calbet JAL, Rådegran G, Sondergaard H, Wagner PD, Saltin B. Parasympathetic Neural Activity Accounts for the Lowering of Exercise Heart Rate at High Altitude. Circulation. 2001;104(15):1785-91. [CrossRef]

- León-Velarde F, Richalet JP, Chavez JC, Kacimi R, Rivera-Chira M, Palacios JA, et al. Hypoxia- and normoxia-induced reversibility of autonomic control in Andean guinea pig heart. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81(5):2229-34. [CrossRef]

- Acker T, Acker H. Cellular oxygen sensing need in CNS function: physiological and pathological implications. J Exp Biol. 2004;207(18):3171–88. [CrossRef]

- Gureje O, Korff MV, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent Pain and Well-being. JAMA. 280(2):147-152. [CrossRef]

- Leon-Velarde, F., Bourin, M.-C., Germack, R., Mohammadi, K., Crozatier, B., Richalet, J.-P., 2001. Differential alterations in cardiac adrenergic signal- ing in chronic hypoxia or norepinephrine infusion. Am. J. Physiol. 280, R274–R281. [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, R.S., Bender, P.R., Brooks, G.A., 1991. Arterial catecholamine responses during exercise with acute and chronic high-altitude exposure Am. J. Physiol. 261, E419–E424. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Baseline parameters and vital signs at 3,800 m and 5,100 m. Mean values ± standard deviation.

Table 1.

Baseline parameters and vital signs at 3,800 m and 5,100 m. Mean values ± standard deviation.

| |

Puno (3,828 m) |

La Rinconada (5,100 m) |

P |

Cohen’s d |

| Sistolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) |

105.29 ± 7.70 |

116.00 ± 4.77 |

0.000 |

- 0.021 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) |

70.79 ± 11.45 |

79.43 ± 2.34 |

0.008 |

-0.021 |

Hemoglobin

(g/dl) |

16.16 ± 2.29 |

17.57 ± 1.74 |

0.038 |

-0.032 |

Hematocrit

(%) |

48.79 ± 7.03 |

53.00 ± 5.33 |

0.034 |

-0.032 |

Oxygen saturation

(%) |

89.93 ± 2.01 |

84.29 ± 2.19 |

0.000 |

-0.021 |

Heart Rate

(bpm) |

95.21 ± 11.67 |

87.57 ± 9.39 |

0.062 |

-0.021 |

Table 2.

Heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation and time course of pain during the test in the right arm.

Table 2.

Heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation and time course of pain during the test in the right arm.

| |

RIGHT ARM |

|

|

| |

Puno (3,828m) |

La Rinconada

(5,100 m) |

Cohen’s d |

P |

Time

(s) |

First pain |

30.43 ± 14.15 |

31.00 ± 19.01 |

-0.032 |

0.941 |

| Unbearable pain |

48.43 ± 16.00 |

48.00 ± 19.45 |

-0.10 |

0.955 |

| No pain |

64.86 ± 18.01 |

74.57 ± 19.87 |

-0.05 |

0.286 |

| Oxygen Saturation (%) |

First pain |

88.86 ± 3.65 |

84.29 ± 2.09 |

-0.54 |

0.004 |

| Unbearable pain |

89.29 ± 2.61 |

85.21 ± 1.53 |

-0.48 |

0.000 |

| No Pain |

90.57 ± 2.59 |

86.86 ± 1.87 |

-0.32 |

0.001 |

Heart Rate

(bpm) |

First pain |

95.43± 16.95 |

87.36 ± 9.02 |

-0.26 |

0.135 |

| Unbearable pain |

91.43 ± 13.43 |

84.07 ± 6.47 |

-0.32 |

0.052 |

| No Pain |

83.43 ± 15.97 |

80.00 ± 11.52 |

-0.43 |

0.542 |

Table 3.

Heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation and time course of pain during the test in the left arm.

Table 3.

Heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation and time course of pain during the test in the left arm.

| |

LEFT ARM |

|

|

| |

Puno (3,828m) |

La Rinconada

(5,100 m) |

Cohen’s d |

P |

Time

(s) |

First pain |

19.93 ± 9.44 |

23.07 ± 10.83 |

-0.32 |

0.114 |

| Unbearable pain |

39.50 ± 7.10 |

37.79 ± 10.39 |

-0.05 |

0.475 |

| No pain |

57.14 ± 11.24 |

61.64 ± 14.81 |

-0.32 |

0.111 |

| Oxygen Saturation (%) |

First pain |

89.21 ± 2.99 |

83.29 ± 4.19 |

-0.43 |

0.001 |

| Unbearable pain |

89.64 ± 3.03 |

83.00 ± 2.60 |

-0.43 |

0.000 |

| No Pain |

91.86 ± 2.56 |

85.21 ± 3.55 |

-0.37 |

0.000 |

Heart Rate

(bpm) |

First pain |

90.86 ± 12.83 |

92.50 ± 12.46 |

0.52 |

0.702 |

| Unbearable pain |

92.21 ± 15.16 |

95.14 ± 9.40 |

-0.32 |

0.533 |

| No Pain |

79.79 ± 12.54 |

82.71 ± 5.39 |

0.42 |

0.475 |

Table 4.

Baseline parameters of vital signs at 3800 m and 5100 m by gender.

Table 4.

Baseline parameters of vital signs at 3800 m and 5100 m by gender.

| |

Puno (3,828 m) |

La Rinconada (5,100 m) |

| |

Men |

Women |

P |

Men |

Women |

P |

| Sistolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) |

109.00 ± 6.45 |

102.50 ± 7.73 |

0.122 |

117. 67 ± 0.52 |

114.75 ± 6.16 |

0.274 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) |

76.67 ± 10.80 |

66. 38 ± 10.41 |

0.097 |

80.01 ± 2.36 |

79. 00 ± 2.39 |

0.452 |

Hemoglobin

(g/dl) |

18.36 ± 1.34 |

14.51 ± 1.09 |

0.000 |

18.67 ± 1.56 |

16.75 ± 1.46 |

0.036 |

Hematocrit

(%) |

55.50 ± 4.13 |

43.75 ± 3.45 |

0.000 |

56.33 ± 4.67 |

50.50 ± 4.53 |

0.037 |

Oxygen saturation

(%) |

89. 67 ± 2.16 |

90.13 ± 2.03 |

0.691 |

84.00 ± 0.89 |

84.50 ± 2.88 |

0.691 |

Heart Rate

(bpm) |

97.33 ± 7.20 |

93.63 ± 14.46 |

0.577 |

89.00 ± 11.63 |

86.50 ± 8.02 |

0.641 |

Table 5.

Pain perception changes by gender during the test in the right arm.

Table 5.

Pain perception changes by gender during the test in the right arm.

| |

|

RIGHT ARM |

| |

Puno (3,828 m) |

|

La Rinconada (5,100 m) |

| |

Women |

Men |

P |

Women |

Men |

P |

| Time (s) |

First pain |

32.00 ± 17.33 |

28.33 ± 9.56 |

0.65 |

30.75 ± 22.79 |

31.33 ± 14.56 |

0.96 |

| Unbearable pain |

49.50 ± 20.92 |

47.00 ± 6.99 |

0.78 |

51.38 ± 23.19 |

43.50 ± 13.69 |

0.48 |

| No pain |

64.88 ± 20.48 |

64.83 ± 16.02 |

0.99 |

80.25 ± 18.79 |

67.00 ± 20.29 |

0.23 |

| Exasperation time |

17.50 ± 14.35 |

18.67 ± 4.13 |

0.85 |

20.63 ± 6.37 |

12.17 ± 6.85 |

0.04 |

| Pain resolution time |

15.38 ± 4.07 |

17.83 ± 9.88 |

0.51 |

28.88 ± 13.09 |

23.50 ± 6.56 |

0.37 |

Table 6.

Pain perception changes by gender during the test in the left arm.

Table 6.

Pain perception changes by gender during the test in the left arm.

| |

LEFT ARM |

| |

Puno (3,828 m) |

La Rinconada (5,100 m) |

| |

Women |

Men |

P |

Women |

Men |

P |

Time

(s) |

First pain |

16.38 ± 7.93 |

24.67 ± 9.83 |

0.11 |

22.88 ± 13.58 |

23.33 ± 6.83 |

0.94 |

| Unbearable pain |

37.13 ± 5.59 |

42.67 ± 8.14 |

0.16 |

40.75 ± 10.89 |

33.83 ± 9.06 |

0.23 |

| No pain |

52.75 ± 7.23 |

63.00 ± 13.54 |

0.09 |

60.50 ± 8.93 |

63.17 ± 21.31 |

0.75 |

| Exasperation time |

20.75 ± 8.83 |

18.00 ± 1.79 |

0.47 |

17.88 ± 8.44 |

10.50 ± 2.35 |

0.06 |

| Pain resolution time |

15.63 ± 2.77 |

20.33 ± 6.86 |

0.10 |

19.75 ± 6.14 |

29.33 ± 14.57 |

0.12 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).