Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wheat Varieties, Virus Isolate, and Mite Population

2.2. Mites

2.3. Effect of Single vs Mixed Infection of WSMV and TriMV on Incubation Period, Symptom Severity, Disease Incidence, and Virus Accumulation in Wheat Cultivars with Varying Genetic

2.4. Effect of Single vs Mixed Infection of WSMV and TriMV in Wheat Cultivars on Wheat Curl Mite Developmental Time, Fecundity, and Virus Acquisition

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

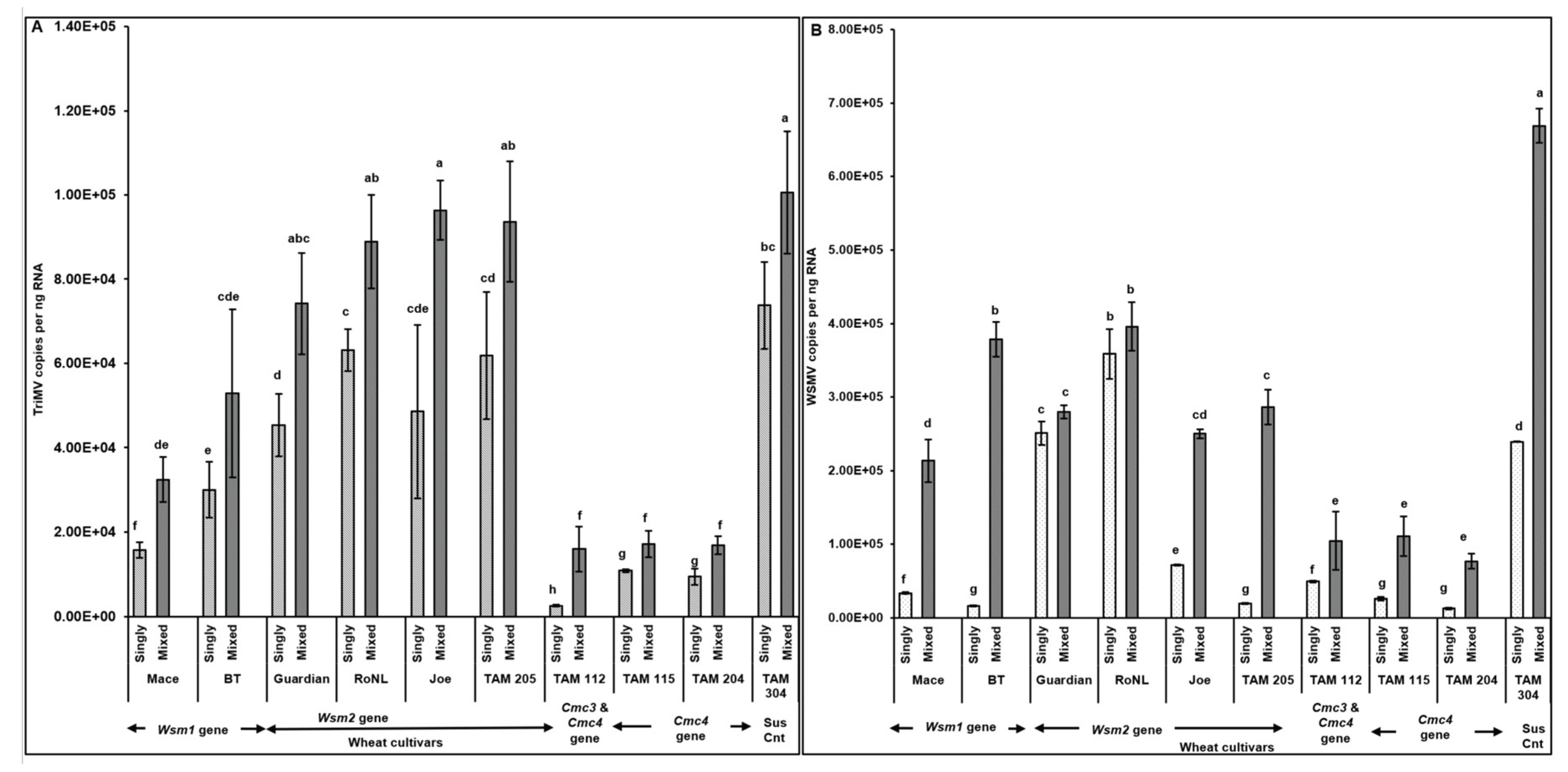

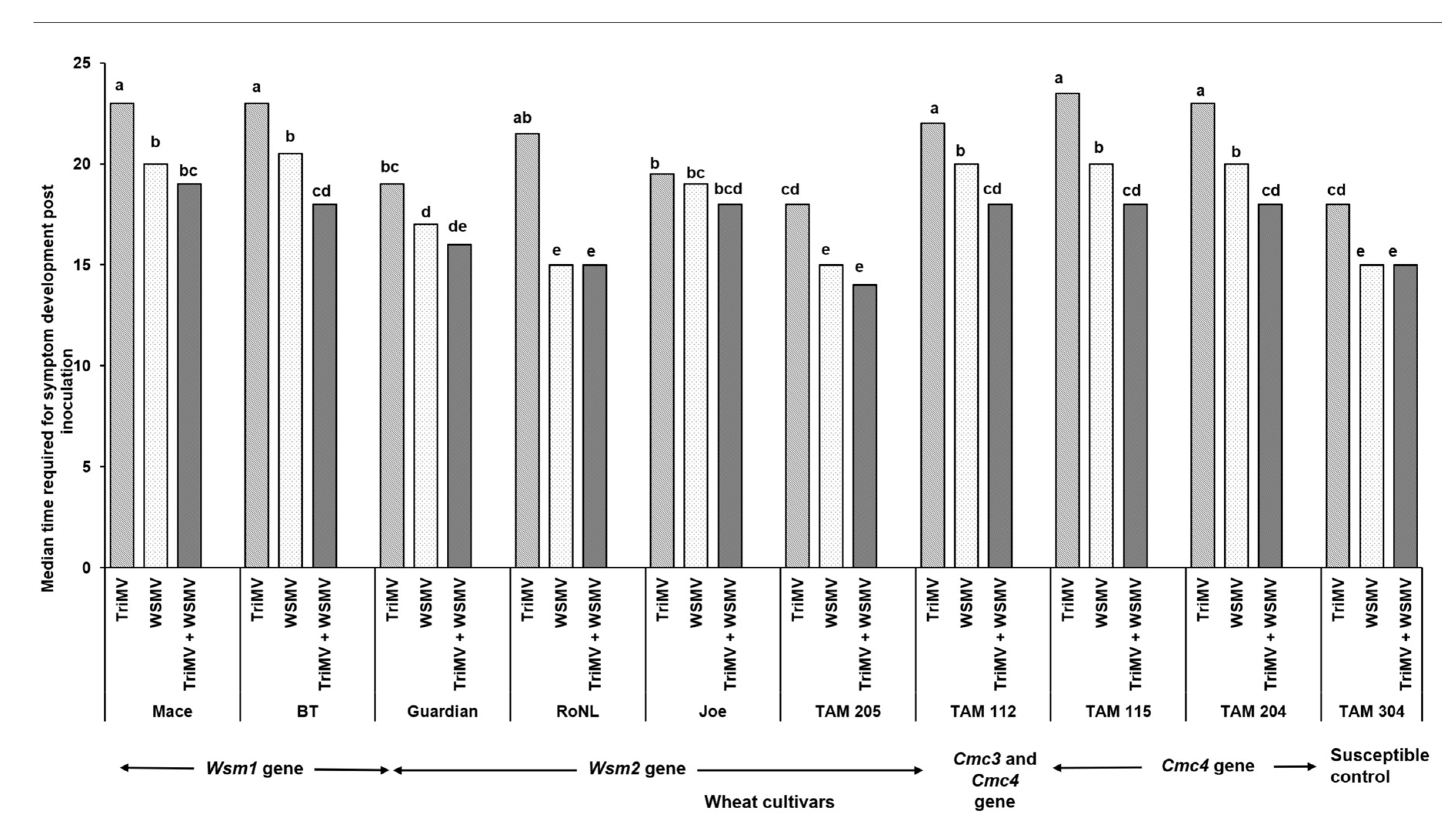

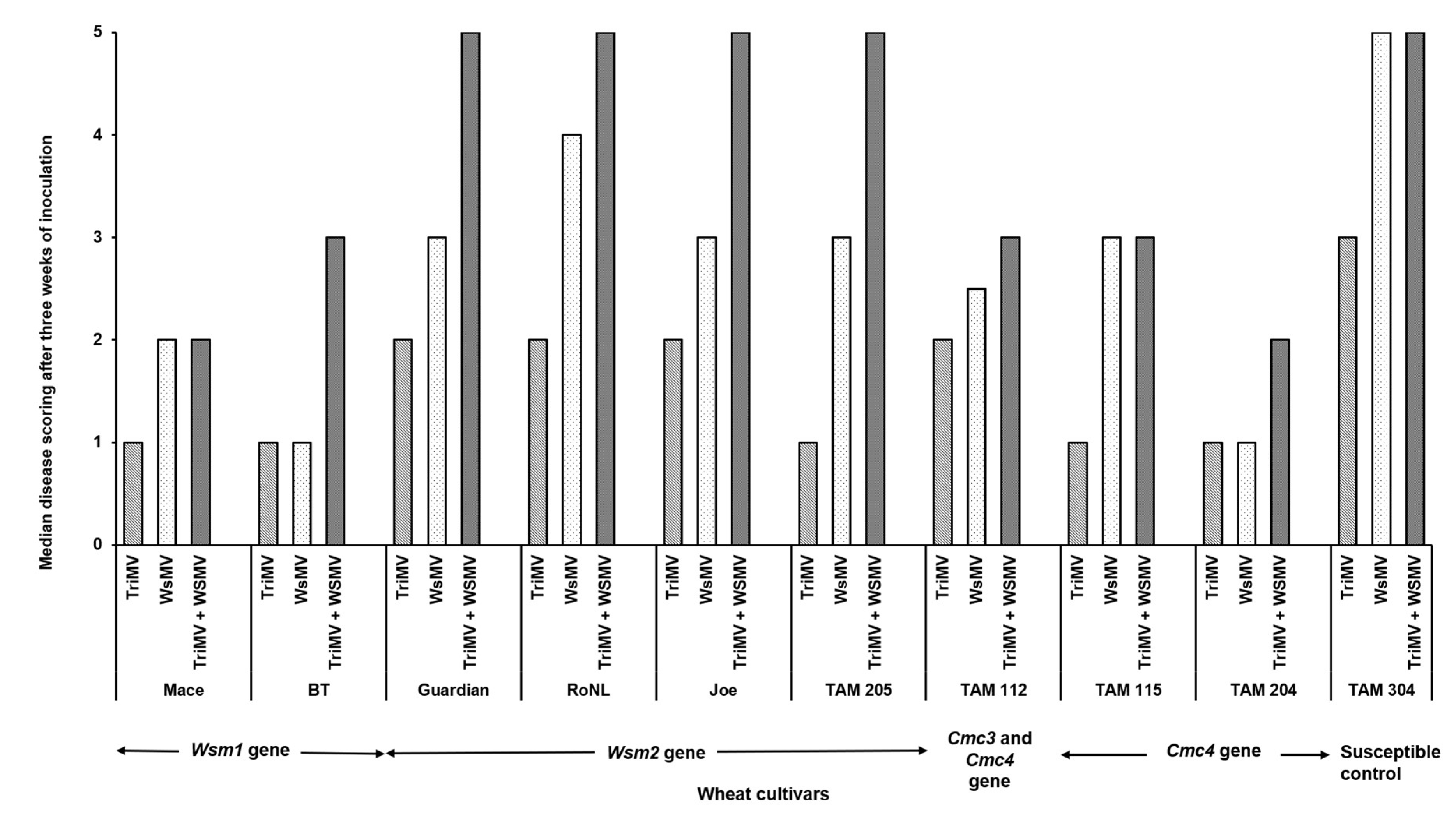

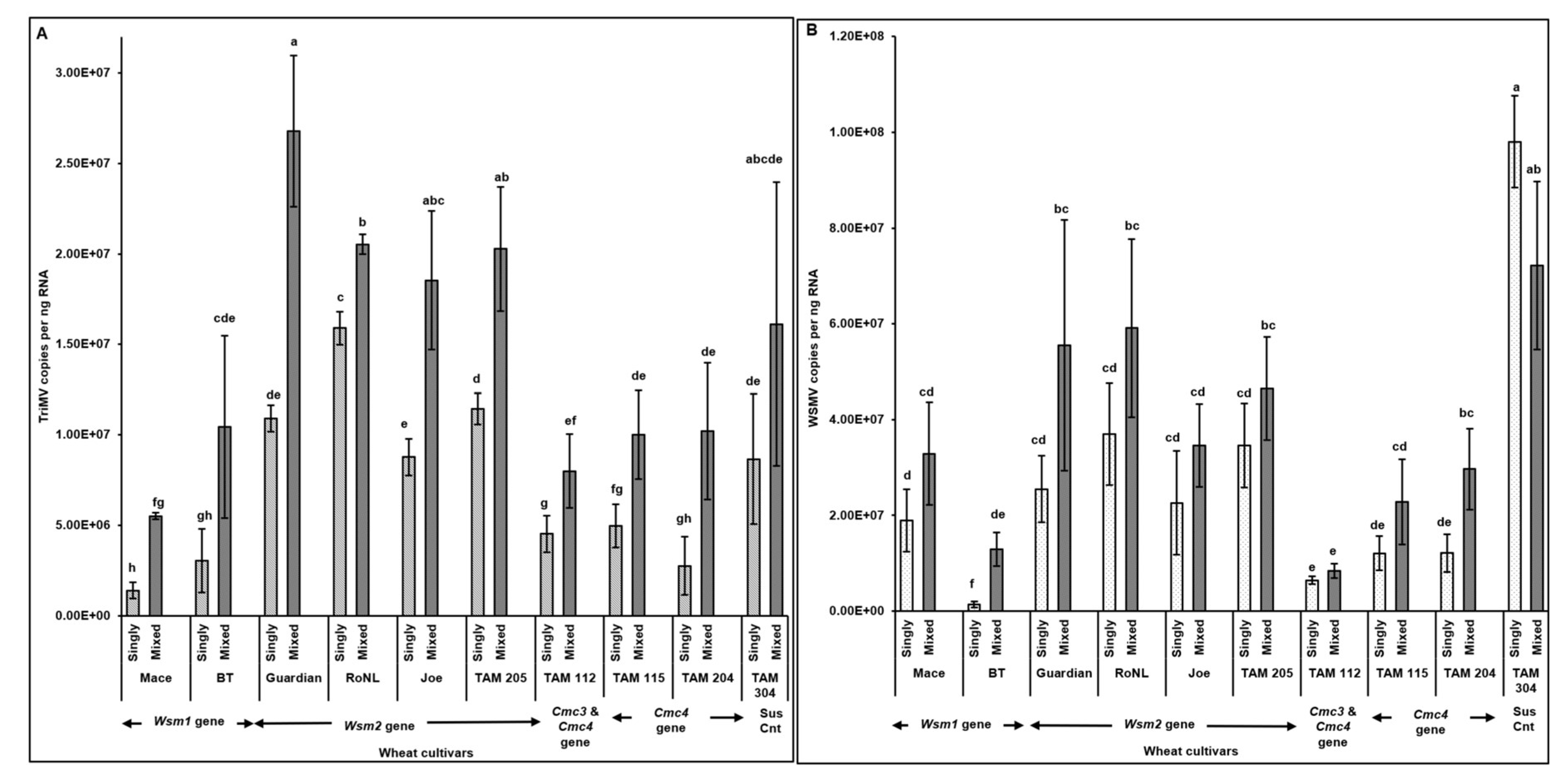

3.1. Effect of Single vs Mixed Infection of WSMV and TriMV on Incubation Period, Symptom Severity, and Virus Accumulation in Wheat Cultivars with Varying Genetics

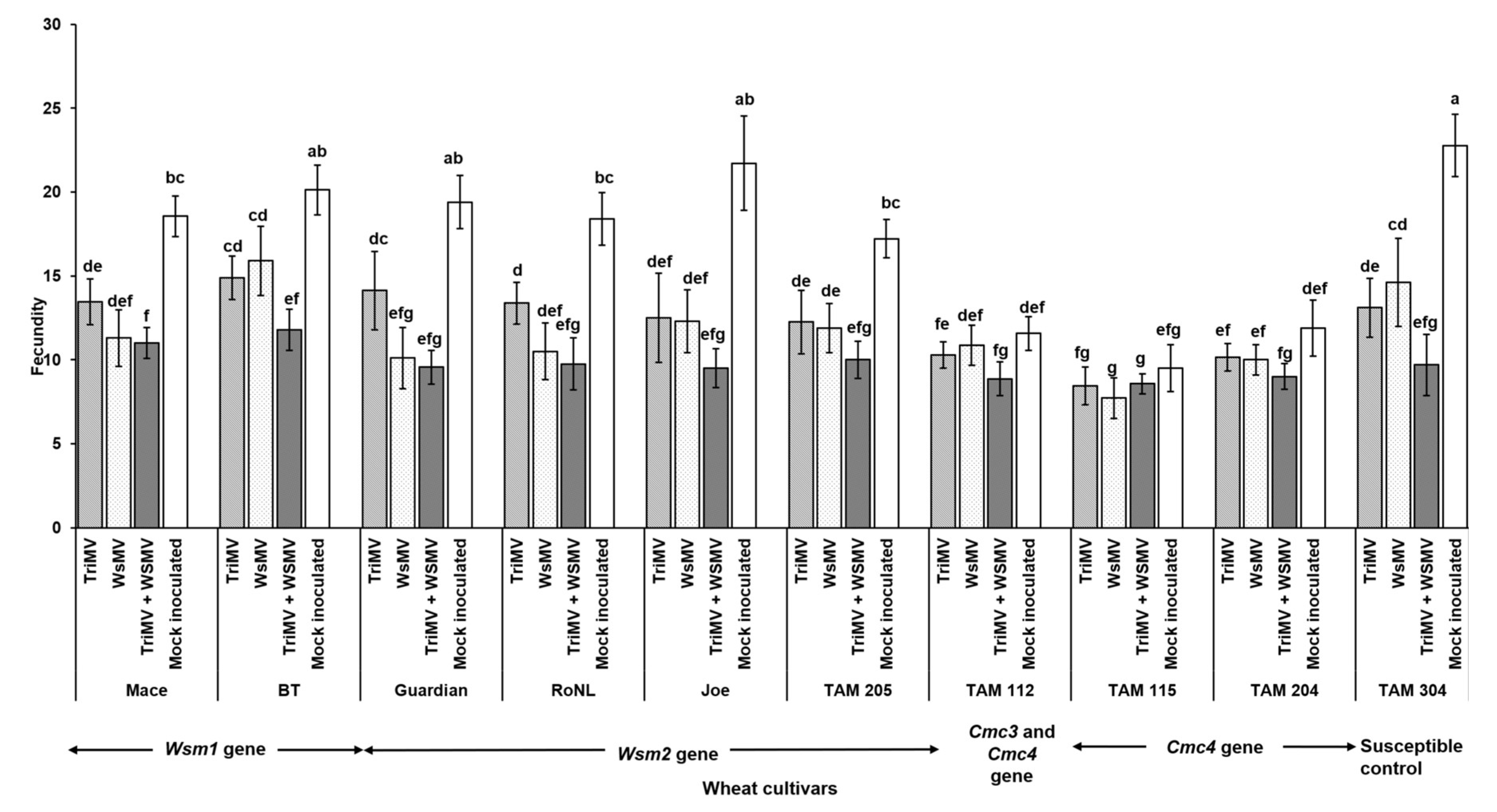

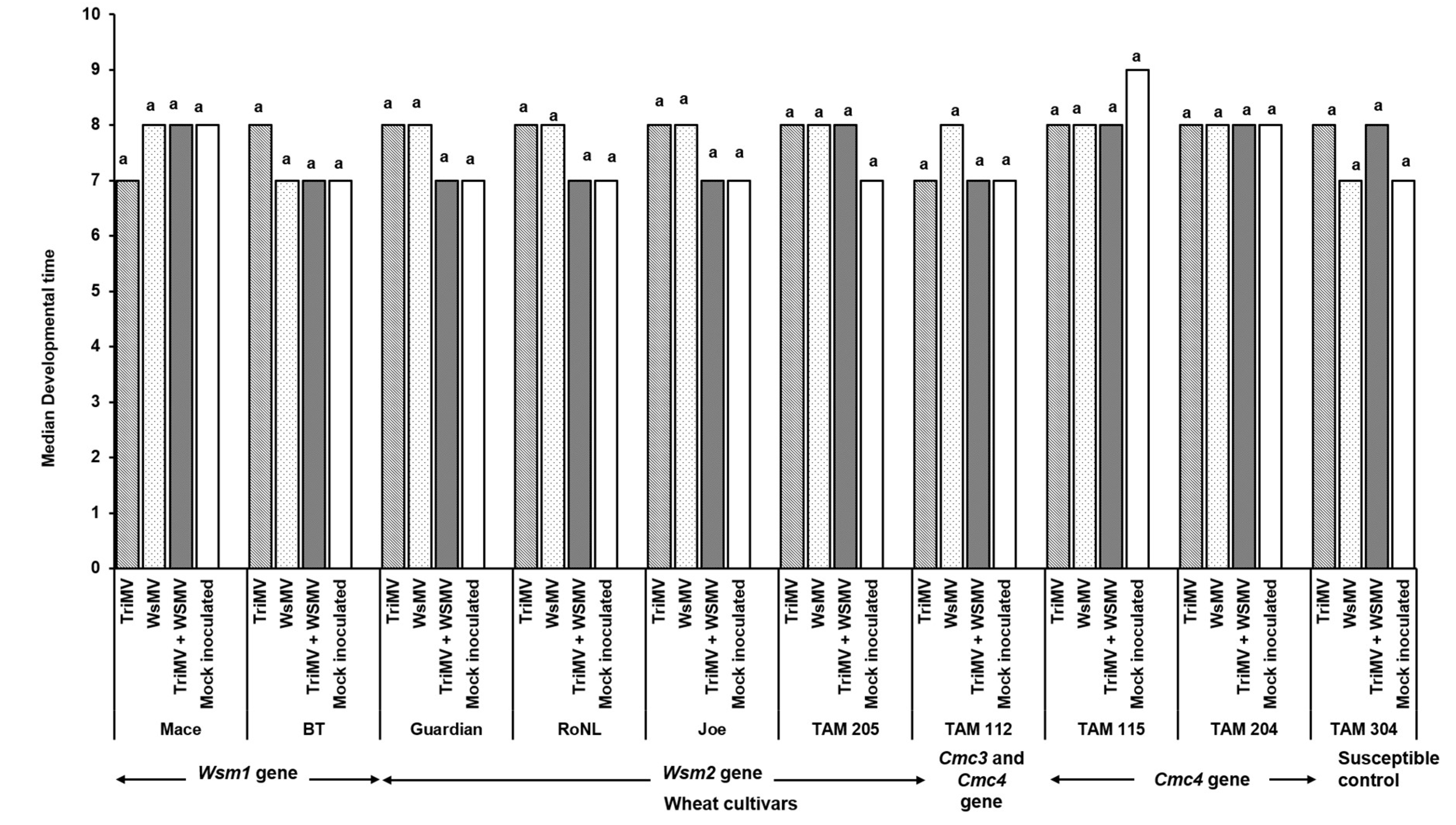

3.2. Effect of Single vs Mixed Infection of WSMV and TriMV on Developmental Time, Fecundity, and Virus Accumulation in Mites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seifers, D.L.; Harvey, T.L.; Martin, T.J.; Jensen, S.G. Identification of the Wheat Curl Mite as the Vector of the High Plains Virus of Corn and Wheat. Plant Dis 1997, 81, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slykhuis, J.T. Aceria Tulipae Keifer (Acarina: Eriophyidae) in Relation to the Spread of Wheat Streak Mosaic. Phytopathology 1955, 45, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tatineni, S.; Ziems, A.D.; Wegulo, S.N.; French, R. Triticum Mosaic Virus : A Distinct Member of the Family Potyviridae with an Unusually Long Leader Sequence. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Harvey, T.L.; Fellers, J.P.; Stack, J.P.; Ryba-White, M.; Haber, S.; Krokhin, O.; Spicer, V.; Lovat, N.; et al. Triticum Mosaic Virus: A New Virus Isolated from Wheat in Kansas. Plant Dis 2008, 92, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.G. A New Disease of Maize and Wheat in the High Plains. Plant Dis 1996, 80, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.; Franc, G.; Rush, C.; Blunt, T.; Ito, D.; Kinzer, K.; Olson, J.; O’Mara, J.; Price, J.; Tande, C.; et al. Occurrence of Viruses in Wheat in the Great Plains Region, 2008. Plant Health Prog 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamukama, E.; Seifers, D.L.; Hein, G.L.; De Wolf, E.; Tisserat, N.A.; Langham, M.A.C.; Osborne, L.E.; Timmerman, A.; Wegulo, S.N. Occurrence and Distribution of Triticum Mosaic Virus in the Central Great Plains. Plant Dis 2013, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, B.; Paetzold, L.; Workneh, F.; Rush, C.M. Incidence of Mite-Vectored Viruses of Wheat in the Texas High Plains and Interactions With Their Host and Vector. Plant Dis 2019, 103, 2996–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamukama, E.; Wegulo, S.N.; Tatineni, S.; Hein, G.L.; Graybosch, R.A.; Baenziger, P.S.; French, R. Quantification of Yield Loss Caused by Triticum Mosaic Virus and Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus in Winter Wheat Under Field Conditions. Plant Dis 2014, 98, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; Graybosch, R.A.; Hein, G.L.; Wegulo, S.N.; French, R. Wheat Cultivar-Specific Disease Synergism and Alteration of Virus Accumulation During Co-Infection with Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Harvey, T.L.; Fellers, J.P.; Michaud, J.P. Identification of the Wheat Curl Mite as the Vector of Triticum Mosaic Virus. Plant Dis 2009, 93, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navia, D.; de Mendonça, R.S.; Skoracka, A.; Szydło, W.; Knihinicki, D.; Hein, G.L.; da Silva Pereira, P.R.V.; Truol, G.; Lau, D. Wheat Curl Mite, Aceria Tosichella, and Transmitted Viruses: An Expanding Pest Complex Affecting Cereal Crops. Exp Appl Acarol 2013, 59, 95–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royalty, R.N.; Perring, T.M. Nature of Damage and Its Assessment. In Eriophyoid Mites: Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control; Lindquist, E.E., Sabelis, M.W., Bruin, J., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 493–512. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, G.L.; French, R.; Siriwetwiwat, B.; Amrine, J.W. Genetic Characterization of North American Populations of the Wheat Curl Mite and Dry Bulb Mite. J Econ Entomol 2012, 105, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMechan, A.J.; Tatineni, S.; French, R.; Hein, G.L. Differential Transmission of Triticum Mosaic Virus by Wheat Curl Mite Populations Collected in the Great Plains. Plant Dis 2014, 98, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Hofman, C.; Wegulo, S.N.; Tatineni, S.; Hein, G.L. Impact of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus Coinfection of Wheat on Transmission Rates by Wheat Curl Mites. Plant Dis 2015, 99, 1170–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, Y.C. Relationship of Wheat Streak Mosaic and Barley Stripe Mosaic Viruses to Vector and Nonvector Eriophyid Mites. Arch Virol 1980, 63, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; Hein, G.L. Genetics and Mechanisms Underlying Transmission of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus by the Wheat Curl Mite. Curr Opin Virol 2018, 33, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Orlob, G.B. Distribution of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus-like Particles in Aceria Tulipae. Virology 1969, 38, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlob, G.B. Feeding and Transmission Characteristics of Aceria Tulipae Keifer as Vector of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus). Journal of Phytopathology 1966, 55, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Hein, G.L. Influence of Volunteer Wheat Plant Condition on Movement of the Wheat Curl Mite, Aceria Tosichella, in Winter Wheat. Exp Appl Acarol 2003, 31, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Garrett, K.A.; Peterson, D.E.; Harvey, T.L.; Bowden, R.L.; Fang, L. The Window of Risk for Emigration of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Varies with Host Eradication Method. Plant Dis 2005, 89, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.J. Control of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus with Vector Resistance in Wheat. Phytopathology 1984, 74, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachappa, P.; Haley, S.; Pearce, S. Resistance to the Wheat Curl Mite and Mite-Transmitted Viruses: Challenges and Future Directions. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2021, 45, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti, J.S.; Baenziger, P.S.; Graybosch, R.A.; French, R.; Gill, K.S. Registration of Seven Winter Wheat Germplasm Lines Carrying the Wsm1 Gene for Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Resistance. J Plant Regist 2011, 5, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybosch, R.A.; Peterson, C.J.; Baenziger, P.S.; Baltensperger, D.D.; Nelson, L.A.; Jin, Y.; Kolmer, J.; Seabourn, B.; French, R.; Hein, G.; et al. Registration of ‘Mace’ Hard Red Winter Wheat. J Plant Regist 2009, 3, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, S.D.; Johnson, J.J.; Peairs, F.B.; Stromberger, J.A.; Heaton, E.E.; Seifert, S.A.; Kottke, R.A.; Rudolph, J.B.; Martin, T.J.; Bai, G.; et al. Registration of ‘Snowmass’ Wheat. J Plant Regist 2011, 5, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Harvey, T.L.; Haber, S. Temperature-Sensitive Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Resistance Identified in KS03HW12 Wheat. Plant Dis 2007, 91, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.A.; Simmons, A.R.; Rashed, A.; Workneh, F.; Rush, C.M. Winter Wheat Cultivars with Temperature-Sensitive Resistance to Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Do Not Recover from Early-Season Infections. Plant Dis 2014, 98, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; Wosula, E.N.; Bartels, M.; Hein, G.L.; Graybosch, R.A. Temperature-Dependent Wsm1 and Wsm2 Gene-Specific Blockage of Viral Long-Distance Transport Provides Resistance to Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus in Wheat. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2016, 29, 724–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifers, D.L. Temperature Sensitivity and Efficacy of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Resistance Derived from Agropyron Intermedium. Plant Dis 1995, 79, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Harvey, T.L.; Haber, S.; Haley, S.D. Temperature Sensitivity and Efficacy of Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Resistance Derived from CO960293 Wheat. Plant Dis 2006, 90, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumssa, T.T.; Zhao, D.; Bai, G.; Zhang, G. Resistance to Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus in Wheat Lines Carrying Wsm1 and Wsm3. Eur J Plant Pathol 2017, 147, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, T.L.; Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Brown-Guedira, G.; Gill, B.S. Survival of Wheat Curl Mites on Different Sources of Resistance in Wheat. Crop Sci 1999, 39, 1887–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Tan, C.; Paezold, L.; Fuentealba, M.P.; Rudd, J.C.; Blaser, B.C.; Xue, Q.; Rush, C.M.; Devkota, R.N.; Liu, S. Wheat Curl Mite Resistance in Hard Winter Wheat in the US Great Plains. Crop Sci 2017, 57, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, 2019 R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J Stat Softw 2015, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An {R} Companion to Applied Regression, Second Edition; Thousand Oaks CA, 2011.

- Lenth, R. V. Least-Squares Means: The R Package Lsmeans. J Stat Softw 2016, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biometrical Journal 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, B.; Qi, L.L.; Wilson, D.L.; Chang, Z.J.; Seifers, D.L.; Martin, T.J.; Fritz, A.K.; Gill, B.S. Wheat– Thinopyrum Intermedium Recombinants Resistant to Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus. Crop Sci 2009, 49, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; Alexander, J.; Gupta, A.K.; French, R. Asymmetry in Synergistic Interaction Between Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus in Wheat. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2019, 32, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicka-Ignatowska, K.; Laska, A.; Rector, B.G.; Skoracka, A.; Kuczyński, L. Temperature-Dependent Development and Survival of an Invasive Genotype of Wheat Curl Mite, Aceria Tosichella. Exp Appl Acarol 2021, 83, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwetwiwat, Benjawan, “Interactions between the Wheat Curl Mite, Aceria Tosichella Keifer (Eriophyidae), and Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Distribution of Wheat Curl Mite Biotypes in the Field” (2006). ETD Collection for University of Nebraska-Lincoln. AAI3237062.

- Murugan, M.; Cardona, P.S.; Duraimurugan, P.; Whitfield, A.E.; Schneweis, D.; Starkey, S.; Smith, C.M. Wheat Curl Mite Resistance: Interactions of Mite Feeding With Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus Infection. J Econ Entomol 2011, 104, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | Cultivar | Trait | Resistant Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mace | Resistant to WSMVa and TriMVb | Wsm1 |

| 2 | Breakthrough | ||

| 3 | RonL | Resistant to WSMV |

Wsm2 |

| 4 | Guardian | ||

| 5 | Joe | ||

| 6 | TAM 205 | ||

| 7 | TAM 112 | Resistant to WCMc | Cmc3 and cmc4 |

| 8 | TAM 115 | Cmc 4 | |

| 9 | TAM 204 | ||

| 10 | TAM 304 | Susceptible | None |

| Cultivars carrying Wsm1 gene | Cultivars carrying Wsm2 gene | Cultivar carrying Cmc3 & Cmc4 | Cultivar carrying Cmc4 | Susceptible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mace | Breakthrough | Guardian | RoNL | Joe | TAM 205 | TAM 112 | TAM 115 | TAM 204 | TAM 304 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | T | W | T + W | M-I | ||

| Exp Repeat 1 | 1 | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - |

| 2 | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 3 | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | |

| 4 | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 5 | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | |

| 6 | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 7 | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | |

| 8 | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 9 | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | |

| 10 | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | |

| Exp Repeat 2 | 1 | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - |

| 2 | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 3 | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 4 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 5 | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 6 | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 7 | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 8 | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | |

| 9 | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | |||

| 10 | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | |

| % infection | 70 | 55 | 75 | 0 | 70 | 55 | 75 | 0 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 0 | 50 | 80 | 65 | 0 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 0 | 70 | 85 | 90 | 0 | 70 | 65 | 55 | 0 | 70 | 50 | 70 | 0 | 60 | 55 | 70 | 0 | 75 | 90 | 90 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).