Aims of the article

In this article, we explore how therapeutic conversations, in particular the role of Joy, expectation and curiosity relate to and have been analysed using something we call the 6D Performative Analytical Model (PAM) (details, dimensions, dynamics, dispositions, dislocations and descriptions). We do this by applying it to case studies comprising six fundamental elements of therapeutic work (assumptions about professionals’ expertise, history taking, their theories and models, analysis of information, therapeutic stance and decision making, nuances and distinctions). This is an emerging work we’re developing in our therapeutic practice, supervision and work as academics. We use ideas gleaned from our teaching, consultation, and workshops with other professionals, clients, and service users to build a case for recognising the transformative dynamics of Joy and encourage professionals to foster curious therapeutic conversations with clients. To this end, we offer this article as an introduction to some of the theoretical and pragmatic issues relating to Joy, as well as its use and value in encouraging better therapeutic outcomes through curious conversations with clients. First, we will define Joy and its role in the therapeutic moment. Second, we’ll consider the solution orientated nature of 6D PAM and how it allows for a reconsideration of something unassuming like Joy and third, discuss our work called the ‘Joy (n) Us Project’ by employing case studies to demonstrate how Joy has altered our appreciation of the aforementioned fundamentals in our therapeutic work. Our over-reaching aims intend to encourage therapists of all fields to reconceptualise how the considered simplicity of Joy as a sensation, experience and strategy can foster curious conversations and promote some fundamental principles of contemporary client oriented therapeutics: 1) an unknowing therapist is solution focused and not solution forced; 2) clients are the experts of their life and 3) Joy is best placed to foster curious conversation between experts.

Introduction to the Joy (n) Us Project

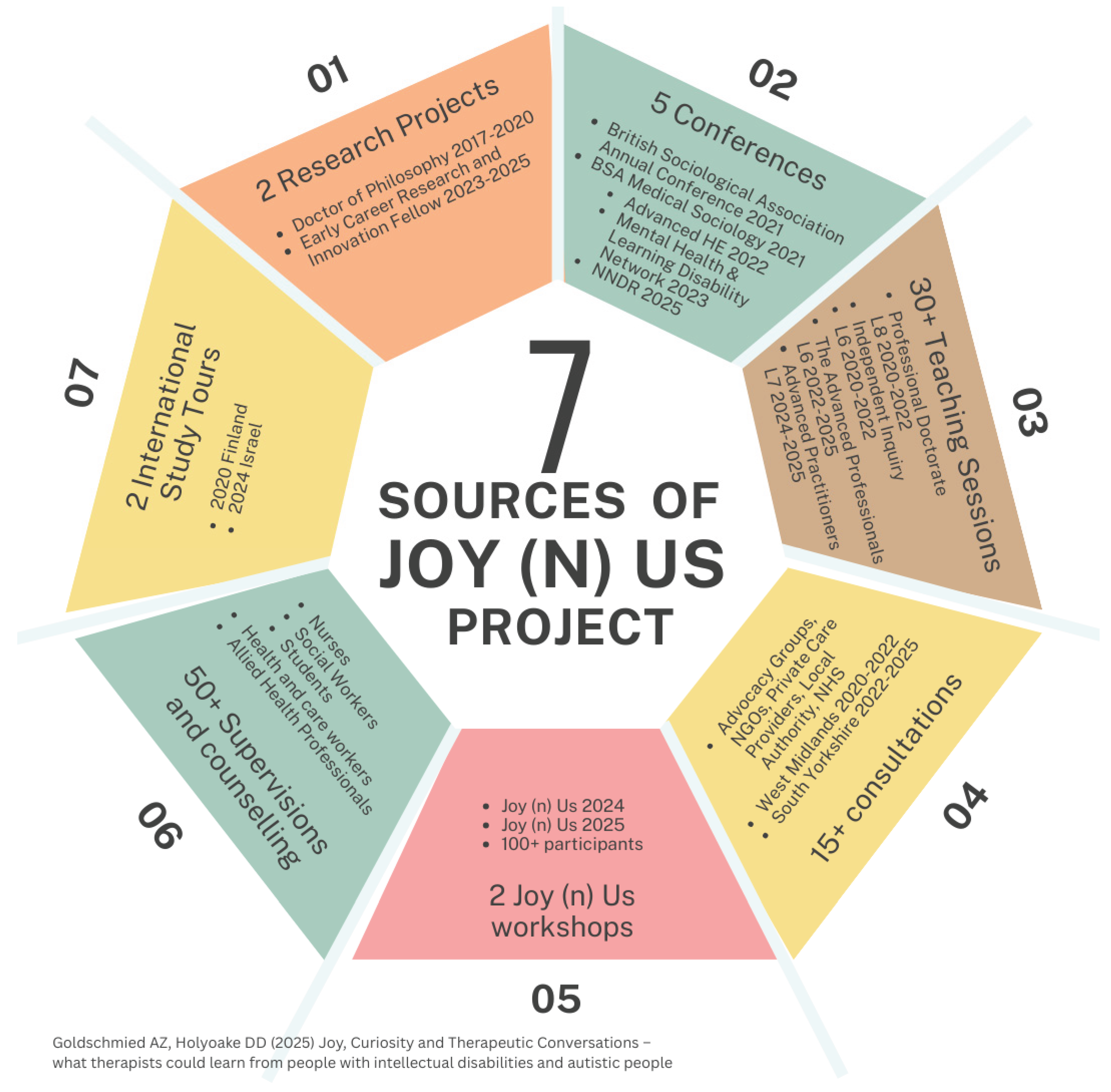

Our population are people with intellectual disability and autism who have a general appreciation of Joy and its currency, which prompted us to start exploring it as a valuable concept for considering how clients have better conversations when the therapist is hyper-curious like a nosy best friend. Like someone who does not have all the expert answers or an off-the-shelf map with which to direct the conversation and thus therapeutic outcomes. The idea of identifying and valuing Joy lies at the heart of what we mean by the ‘Joy (n) Us Project’. One that elevates the concept of Joy as a recognisable phenomenon experienced by clients and a skill on behalf of the therapist to undoubtedly commit to ‘trusting the client’ and letting them be the ‘expert in their own life’. Sounds easy and obvious but during the past 5 years of the Joy (n) Us Project (see

Figure 1 for some associated events) we’ve noticed that what clients with Intellectual Disabilities and Autism say about expertise is not what most therapists and practitioners necessarily value.

At first glance, something like Joy might not appear significant in what it means to be and perform as a therapist. Probably because when a client states their complaint and a history is sought, we, the therapist, generally resort to tried and tested formula, strategic skills and time-honoured theory to help analyse the client and their case guided by the therapist’s expertise (1-5 practice issues). The idea of Joy is a million miles from what it means to seek a session outcome and or help the client feel better or move towards a goal (practice issue 6). But what if Joy could be a means to assess future hopes, amplify personal resources and motivate a curious conversation that encourages the client to say to themselves ‘Hmmm, I’d never thought of that, perhaps I can do one small thing better?’ What if, by raising the profile of Joy as something that is not necessarily about happiness or pleasure but rather a capacity and activity fuelled by curiosities typical of most friendly conversations, then perhaps the client and therapist could be left knowing that all the best work is done between sessions. What if Joy, the nuances and mundane experiences of the clients (practice issue 6) could be incorporated into all the domains of therapeutic practices from history taking to decision making (1-5 practice issues)?

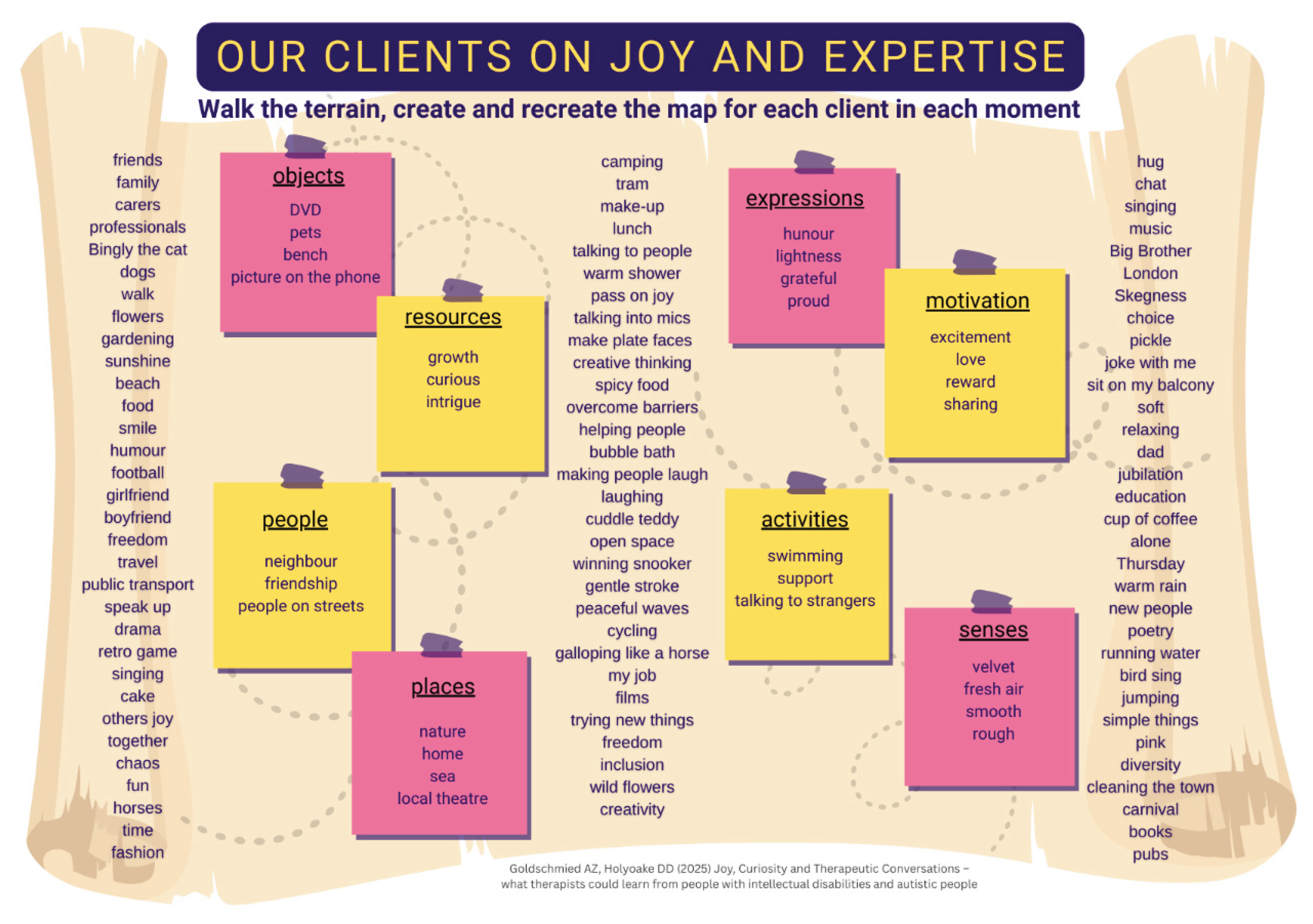

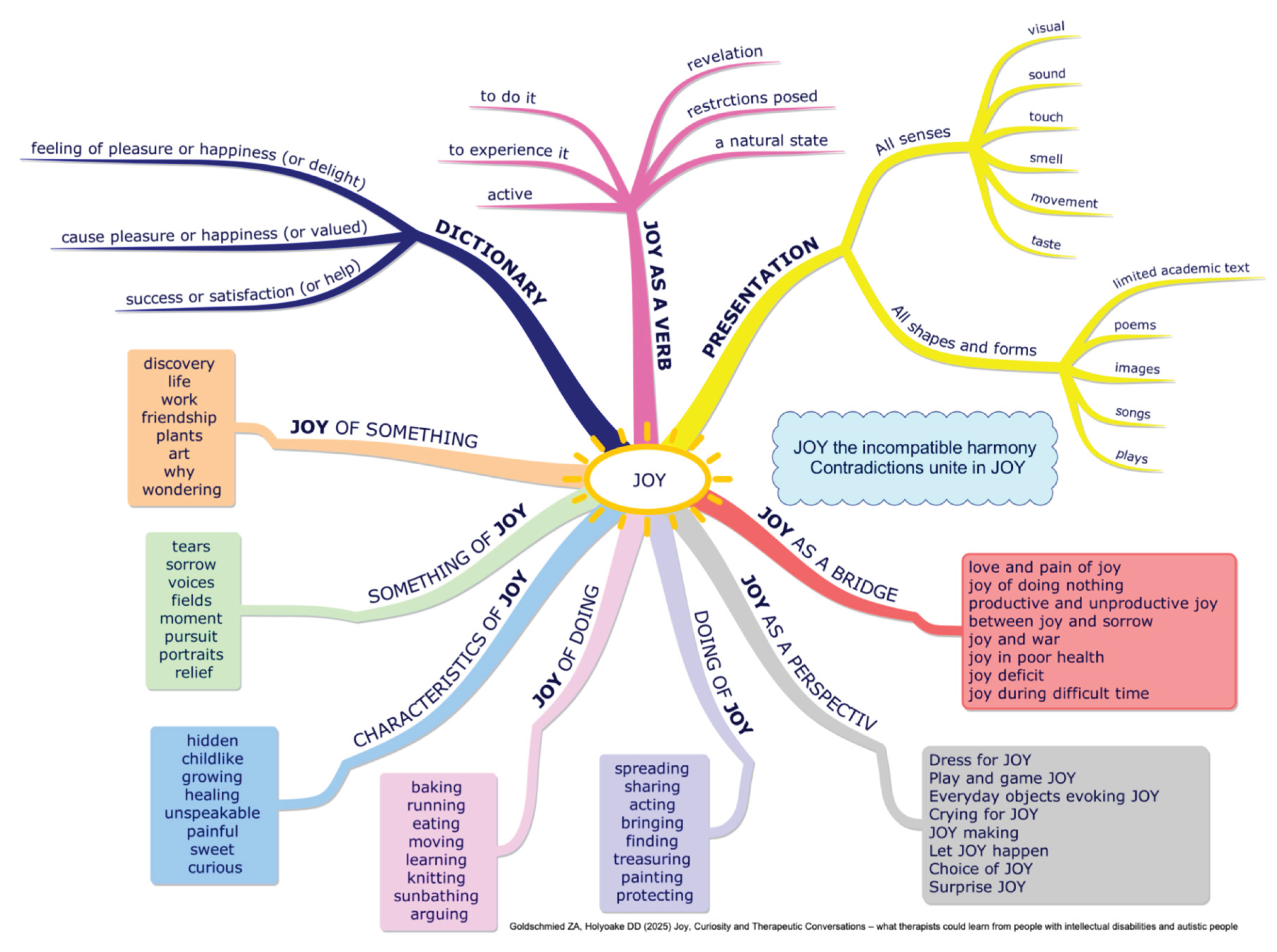

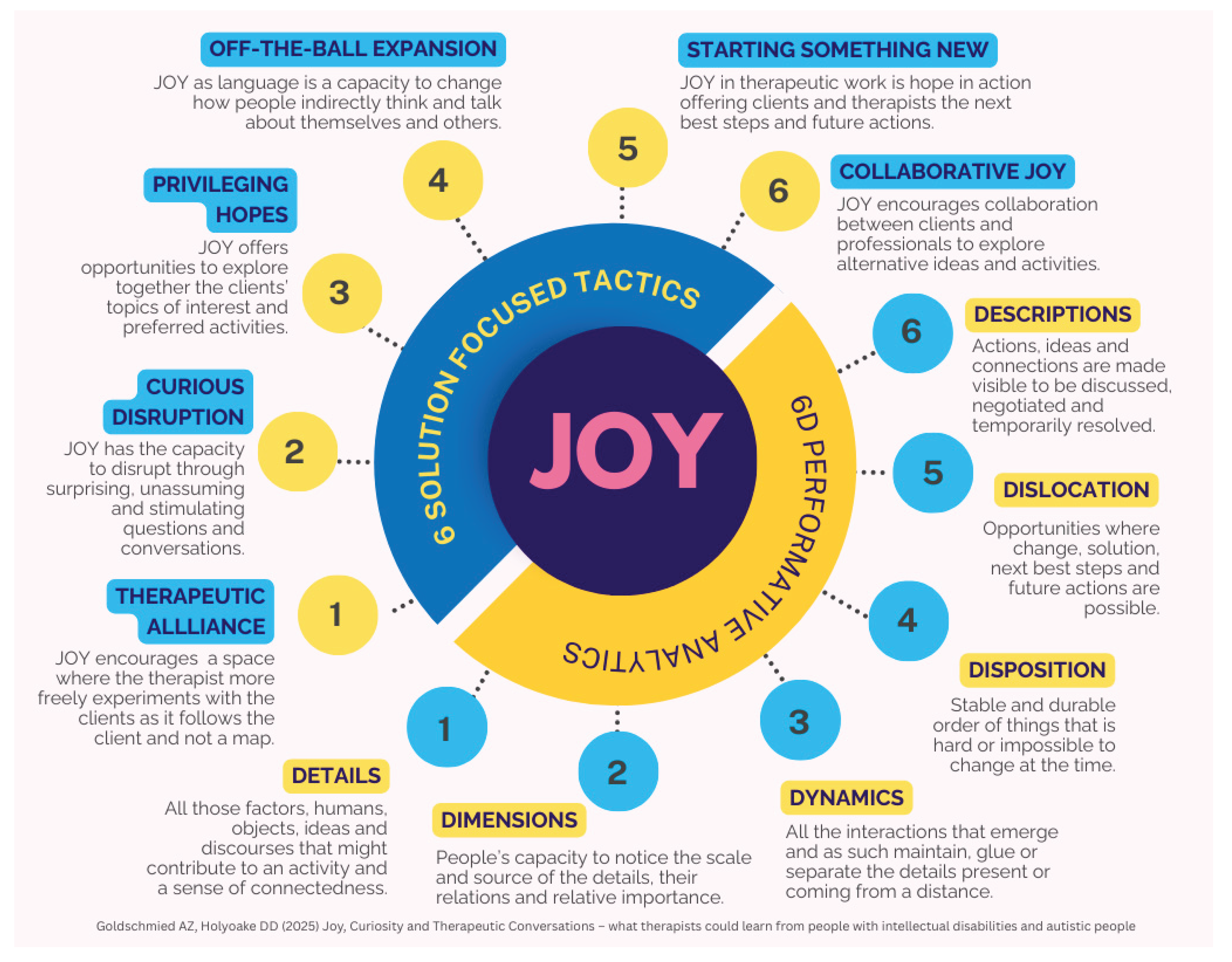

Therapeutic conversations are usually dominated by what therapists consider useful and rational for the session (practice issue 1), rather than a curious space where clients can be in charge, so to speak. We propose Joy as the basis for simple therapeutic work, as our project suggests it is the primary want expressed by clients during the Joy (n) Us Project and other research events. In

Figure 2, we offer an illustration of how Joy might look in therapeutic work. In addition, our application of the 6D PAM shows up how Joy as a concept shares a relationship with what is visible and measurable but, like the wise comments by Feynman[

1] about science and by C.S. Lewis[

2] about Joy, it is something known only through experience. The unpretentiousness and modest appreciation that therapeutics are perhaps less rational or certain than hypothesised, firmly left in the hands of the client, is not only a process of realising Joy but something that can multiply as sessions reveal themselves.

So even when a client arrives expecting answers, they are also probably imagining they’ll need to explore their past in order to improve their future. That the answers they seek are found by figuring stuff out about the problem that is crippling their everyday life. That the nagging doubts keeping them awake at night require sophisticated interventions to free them, rather than the insulting prospect of recognising the Joyful moments when things were better, if only just a little bit. One would have to be foolish to believe that something as simple as Joy might help, but there within lies some reasoning that our clients with intellectual disability and autism showed us. The defining, search for and application of Joy is complex and far more composite than most therapists might consider. Its intricacy and trickiness have come to dominate the last few years of our research and practice. This article represents our introductory consideration about what we term Joy’s Therapeut‘ics’ (the Aesthetics, Economics, Ethics, Logic and Politics of Joy in therapeutic work).

Enjoy the Terrain by Throwing Away off-the-Shelf Maps and Exploring the 6D PAM

If we have learnt anything so far about Joy by employing the 6D performative analytical model, then it’s the idea that what professionals think is not the same as what most clients do. It could be argued that our clients with intellectual disability and autism are led to decisions about which they are not capable of thinking through safely, or that boundaries need establishing, risk assessed and negotiated. There is no doubt that these issues do matter but our exploration of Joy also points up that clients identify with Joy differently (Goldschmied Z, 2021[

19]). In our workshops and projects (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 4), groups of clients expressed very specific ideas about what they think Joy is, how it can be useful and how it presents in everyday life. But here’s the thing, not one of them mentioned the economics, ethics, logic or the politics of Joy. They dislocated the sentiments and not once related Joy to fragmentary biological, social or psychological concepts. Not once did they interrogate the unintended consequences of words belonging to certain worlds, compare normal and abnormal, but they knew very well that a world without the experience of Joy is one of opposition. But if Joy is more than happiness or sadness, then what is its opposite, if any? (See our suggestions later.)

The 6D model for performative analysis of events and activities shows how clients’ recognition of Joy resides in the creative, adaptive and artful approaches of capturing nuanced and complex everyday activities and interactions (see

Figure 2 and

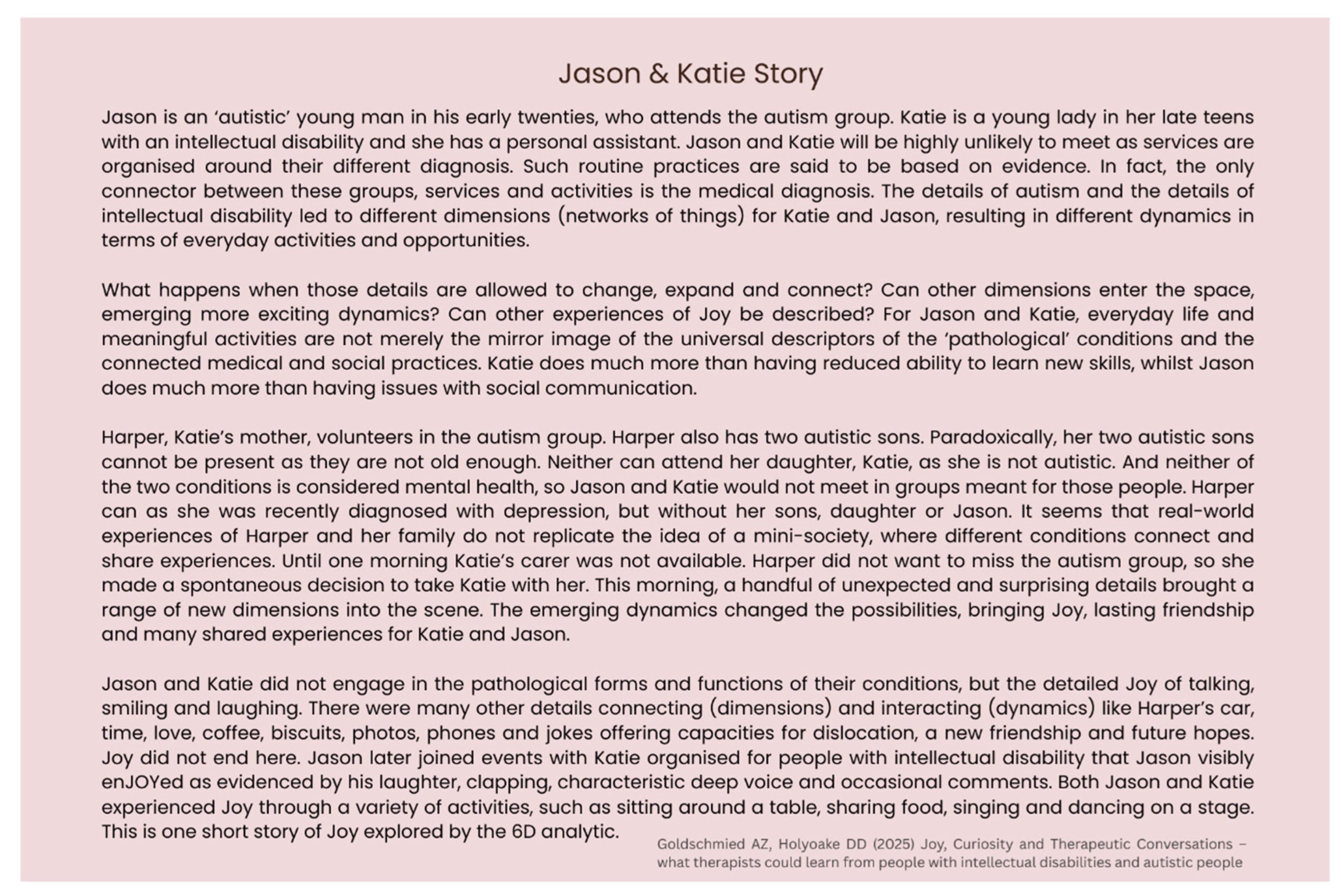

Figure 4). Ones that make visible in everyday processes, for example, how an autistic man and a woman with an intellectual disability can connect and form a loving relationship. The case study in

Figure 5 became the ultimate symbolic and factual underpinning of the Joy (n) Us Project. The case study retells stories and activities about a more Joyful and meaningful appreciation of everyday life and connectivity.

Descriptions of Joy in the therapists’ and clients’ experiences help us curiously explore the many contributing factors (

details), the possible humans, objects, ideas, behaviours and communication of an activity and the nature of the connections between them (

dimensions) to notice what opportunities and alternative actions might emerge from these interactions (

dynamics). Events explored with the 6D performative analytical lens help us accept the things we cannot change, or at least not right now (

disposition), and where the next best steps and future actions might be (

dislocation). In other words, one of the strengths of the 6D analytics is that it considers all the possible humans, objects, ideas, behaviours, and discourses, such as communication first and making decisions second, suspending our assumptions and expertise, including the economics, ethics, logic and politics of care and therapy. The

dimensions component of 6D PAM reminds us that

details of objects, other human beings and fluid ideas have a span reflecting the structuring nature of difference and humanity to operationalise illogical, unwise and even imaginary factors into the clients’ realities. Such

dimensions and

details interacting with each other have the capacity to compose a range of

dynamics between therapists and clients, as well as clients’ appreciation of what happened, happens and could happen. Indeed,

dynamics prompt us to drop or emphasise premature assumptions of what might be possible and open the door to surprise and those unexpected and often Joyful moments that our clients also listed (see

Figure 4).

Disposition is a constituting force that forms, shapes, and orders (amongst other things) our sense of control and reach, sometimes even to the point of ‘killing Joy’.

When practitioners report to us on a session, how a tattoo can be seen as a sign of mental disorder if its symbol is deemed to be age-inappropriate, according to the expert clinicians. Whilst

dislocation gives us the means to focus on opportunities and possibilities of change and goals. Joy is such that it brings the element of aesthetics, surprise and curiosity into the therapeutic relationships and conversations, suspending one-sided expertise, thus composing opportunities to

dislocate at moments where

disposition would be expected otherwise.

Descriptions are therapeutic assembly, the economics, ethics, logic and politics of Joy, justification of what is real for the client rather than for the therapists based on off-the-shelf maps and rigid frames of theories and definitions. Like those age-inappropriate tattoos. Curious conversations that provide grounds for collaboration, negotiations, change and co-authoring new or maintaining existing realities.

Figure 6 offers the 6D analytics and how it can be applied to Joy using the principles of solution focused practice to foster curious conversations and therapeutics.

If we can agree that Joy is most likely a combination of biological disposition and social learning, then it is transdisciplinary. Whilst limited work exists from health care professionals, nurses, sociologists, historians, theologians, philosophers, psychologists and business studies on Joy[

20,

21,

22,

23], the word Joy has not yet achieved a fixed meaning, unlike other expressions such as happiness, empathy or compassion. We now have an opportunity to explore its use for our own benefit and that of others. In our therapeutic work, we are open to ideas and initiatives, plan activities together during short visits, projects, conversations and creative activities like the Joy (n) Us workshops (see

Figure 1) to help us appreciate the needs of clients and practitioners, build capacity and collect evidence, and set recommendations by reconsidering connectedness and meaningful everyday activities for people with hidden dis/abilities[

24].

More Results from Practice and Research Underpinning the Work on Joy

Joy is then about encouraging clients to be in charge, be it in a session, supervision, assessment or planning the day ahead, whereby conversations between two experts aim for future goals. Joyful therapeutic works are based on the principles of solution focused practice[

25] and incorporate some specific skills to go through a process of 1) identifying future hopes, 2) amplifying exceptions to past problems, 3) employing hypothetical and visualising tactics and 4) devising a pragmatic task that the client achieves usually after, or ‘in between’ sessions.

Figure 6 demonstrates the main skills we use from solution focused practice.

Our Joy (n) Us project is constantly guided by questions to foster our curiosity, like:

How do people with hidden dis/abilities experience Joy in everyday life?

What can we learn about the processes influencing their experiences of Joy?

What opportunities are there in mixing skills and abilities in everyday life?

How does Joy play a role in meaningful everyday activities and a sense of connectedness?

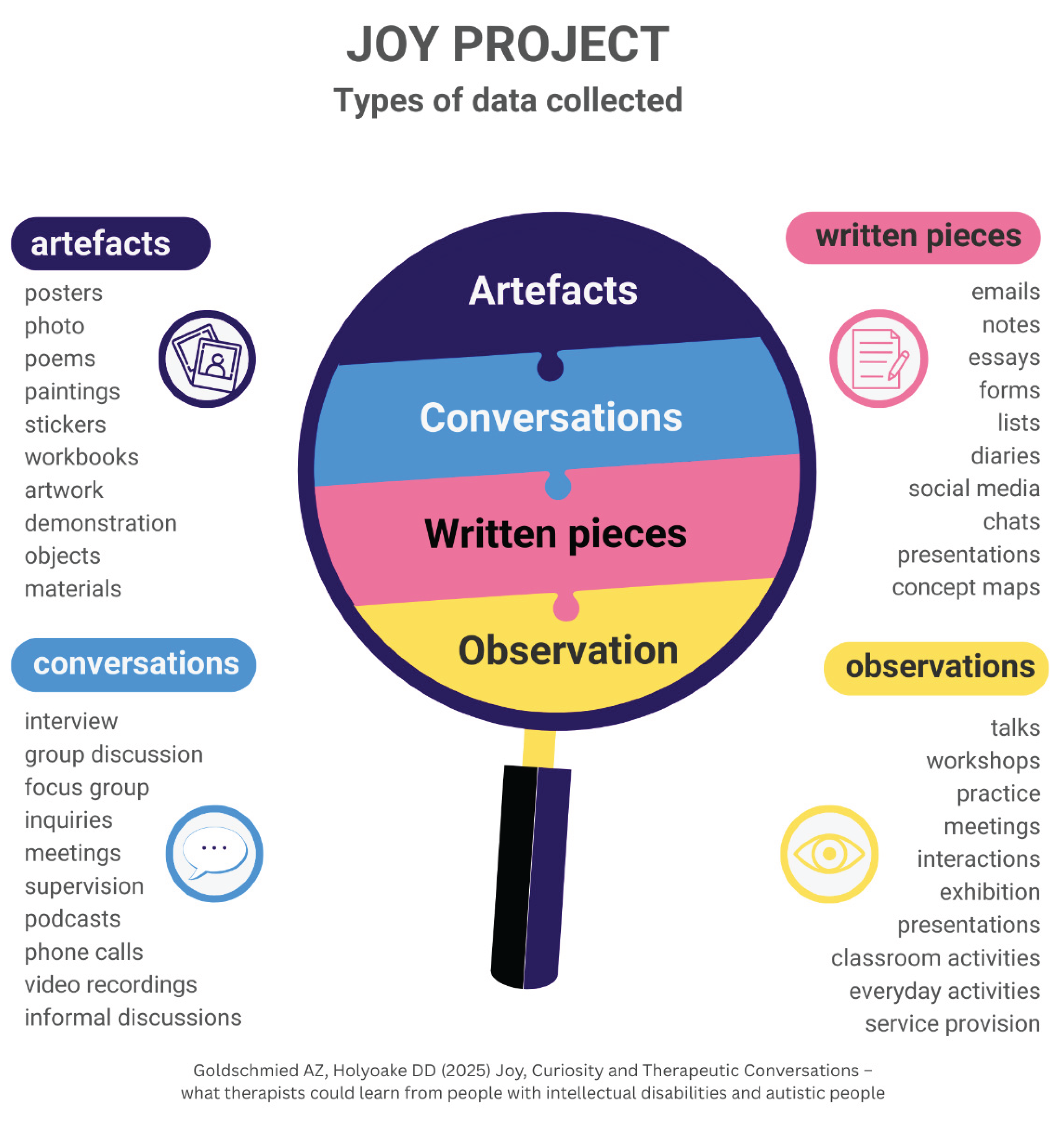

Working with health and social care practitioners (primarily nurses and social workers), service users with diverse needs, and clients in the private and non-profit care sector, we have had opportunities to pilot our method and start collecting feedback.

Figure 7 summarises the type of data we refer to in the article. Subsequent articles will explore in more detail the various elements of the Joy (n) Us Project, including evaluation.

For now, we want to continue exploring how Joy in our novel 6D-6SF practice offers a model for rethinking therapeutics. Anita’s supervision of staff caring for people with various cognitive and mental health conditions brought up some complex questions in our therapeutic approach and how well we prepare students and staff to deal with the unexpected characteristics of our practice. It is amazing and somewhat scary how our care files, assessments and theories dispose us into roles and approaches. There is no supervision that does not include such dilemmas or care files that describe in long sentences what our clients can’t do and why. Like Anna’s thick folder that dispose her into the role of an old lady with cognitive deficit unable to perform most of her enJoyable daily tasks like “she requires guidance to use water heater”, “she has severely limited recognition of risk”, “she cannot read or write”, “she has minimal concentration span”, “she has a poor understanding of what consists a healthy diet” and so on so for another 20+ pages. It requires skill to find some Joy and potential for dislocating her everyday activities, like “she can eat physically independently”, albeit that this is immediately followed by, “although as stated above has an inability to plan meals.” Health and social care therapeutics depend on our expertise to engage our clients so that they can walk in and, in the eyes of some professionals, be saved by therapies done unto them for them (professional issues 1-5). Such tension and contradiction between what these assessment files detail and the nuances of everyday life we have observed during the projects and supervisory work (professional issue 6) is evident. We experience rupture time and time again, sitting in supervision, listening to professionals, spending time with the clients and reviewing cases express the economical, ethical, political, and logical, the expected rational rather than those aesthetics and preferences showed and hoped for by clients, making it difficult to know the real world.

We will continue our second aim by framing and exploring how Joy as rupture is a type of hope in action and a central tenet of contemporary therapeutic practice that puts clients at the centre and focuses on solutions and achievable mundane goals. One that encourages clients to hypothesise, suspend belief and imagine informed and joyful futures. At its broadest and certainly within the scope of intellectual disability and autism practice, the aesthetics of Joy let practitioners employ the use all of senses, creativity and imagination through activities such as poetry, dance, singing, exercise, pottery, baking and some rather unusual activities, like when Kirsty initiates a conversation with a box of cookies in the shop in the hope that she can figure out which one wants to come home with her. Kirsty likes having joyful conversations with objects and all details of her everyday life, not only with humans. Our clients may also paint, write poems, and share Joy, as also seen at our workshops (see

Figure 4). This is a signifying level of connectedness not only with people but with dimensions of objects and everything else surrounding us that allows one to be real or imaginary, in solitude or with others. By employing Joy, the practitioner suspends judgment, assumptions and tried expertise. Such Joy is no different when we observe Anna with a mild intellectual disability doing her shopping despite all those things in her care file (professional issues 2-5). Although Anna can’t count or read the price tags in a way most would consider ‘normal’, and her shopping basket is less sophisticated than most (professional issue 1), watching her walking around the shop, selecting her favourite baked beans, potato, cheese and few more treats ending up almost spot on with a £40 bill that is precisely what she was given to spend, is Joy. Her pride, smile and confidence in her achievement are all the proof she requires. Those small things and nuances of life make all the distinction; no one else knows this better than our clients (professional issue 6).

Both Rob and Paul highlight the case of risks versus freedom (familiar to most practitioners and a recurring theme of our supervisions and therapeutic work) to the fore. How to balance the dispositioning protective and risk-averse professional codes with the dislocating energy and drive of meaningful activities? Support workers took Rob for a walk. He has a reduced ability to notice danger, so he must be accompanied. One day, as they were walking the Fens Pool Nature Reserve, Rob spotted horses that were often left tethered and without thinking, started running towards the animals, making noises, with his arms wide open. The carers panicked and their initial risk-averse mechanism kicked in, trying to prevent him and stop him. The event left the carers in a state that was brought to our supervision by Paul, who started a range of safeguarding conversations and risk assessments, including the escalation of Rob’s condition. Yet, there are alternatives, and we learnt one in our Joy (n) Us Workshop from a manager of a private home who spoke about the dislocating capacity of Joy and recognition that carers not knowing is not uncommon but should not be shamed. There are different dimensions of the contributing details that changed not only the dynamics of this event and other events, but also, as a chain reaction, everything following could have alternatives. All with one Joy-fuelled response from the manager: “Run with him”. In health and social care, we are so used to the negative language that we are in the process of developing the Joy audit, a tool to help practitioners run more with the client and stop them less. The curiosity of what happens when we experience running with the client (practice issue 6) in this instance won over the expert risks, theories and range of policies (practice issues 1-5).

Traditional therapeutics often want to cheer up sad people, get them out of their thoughts, and make them happy. The aesthetics of Joy, on the other hand, highlight how Joy, like hope and curious creativity, cannot be fully controlled, possessed or produced by will alone. This element of surprise maintains hope with a future focus on Joy. Our encounter with professionals, carers and family members suggests that they may think they know better than the client and other professionals, even if they are convinced that everything they do is in the best interests of the service users. Ironically, what none of them seem to see is that they all have diverse clients, so the moment you follow an off-the-shelf map as opposed to constantly creating and recreating it with your clients, you ultimately do good to some while letting down others. And here comes a paradox of therapeutics that we believe Joy can temporarily suspend. If our clients have the capacity to weigh information and make decisions, then no matter what approach we suggest, they will be able to resist (like our adolescent clients and their carers[

26]) and choose so that debates in disability studies and therapeutic practices lose their significance[

27,

28,

29]. On the other hand, if our clients do not have the capacity to access a wide range of information and make informed distinctions and rely heavily on our and others guidance, then we also have a problem as ultimately, no matter what we believe is the proper method, theory and all those tired and tested things we bring in as experts (those six professional issues), we manipulate our clients into our world and certain options, if we allow them choices at all. We know that many clients could not attend the Autism Group or come to the Joy (n) Us workshops as their carers have not passed on the information, presented in a way that reflected their ‘I do not want to go’ attitude, ‘it is too complicated for them’ and a number of other reasons.

Tom had moved to a new residence and two carers helped him settle. He was asked which tablecloth to use. He was presented with a choice of three. “Do you want the blue or the red dotted one?” Tom replied, “I don’t mind”, as he continued placing his favourite pictures on the shelf. The carer was not satisfied with the answer and asked Tom again. “Tell me, do you want the blue or the red dotted one on the dining table”? Tom responded with more frustration. “I do not mind. You can choose one for me.” The answer still was not good enough as the carer responded, “You have to choose.” Eventually, the carer gave up, expressing dissatisfaction with Tom’s behaviour. Clearly, the idea of not choosing was not one of the choices that this carer (and others) would consider a choice. Hence, we are inspired to use Joy more in the therapeutic world, to put our theory into practice, and accept that clients can indeed be experts in their lives, or at least, to guide the therapist in conversations between experts.

DiscussionAbout Putting Joy to Work

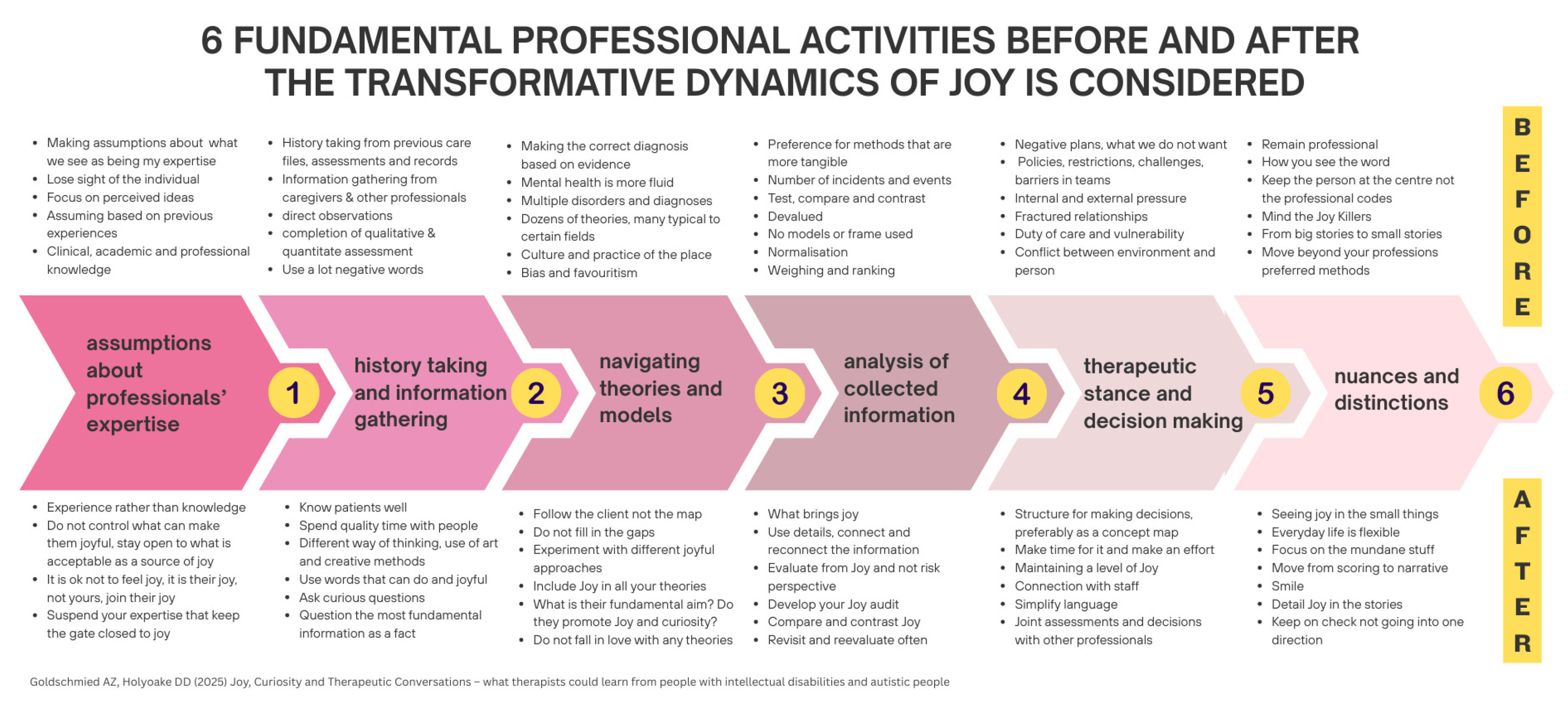

In our work, we are more than aware of the standard training manuals, guides and directives underpinning therapeutic work that we have already started interrogating through the lens of Joy and summarised here as six professional issues (see

Figure 8). In order to expand upon the practicalities of Joy and offer six strategies to add some Joy, we continue to ask questions. Do we need something to go wrong, malfunction and be abnormal in order to use therapeutics? Do we need a problem to be curious about our clients? Do we need to be unhappy or dissatisfied to aim for better outcomes? The ongoing debates regarding normalising tendencies may appear to be, medically speaking, ‘common sense’, but as we discussed in other articles[

26], it is just as much an analysis of a symbolic act for our work. The problem with such modernist and essentialist views is their tendency to be grounded in constant comparison to a perceived norm. As such, material bodies, abstract persons, and structured societies are easily perceived as existing separately[

30,

31], as reflected in mainstream medical and social approaches in therapeutics, giving birth to experts.

Traditional approaches generally fail to recognise how curiosity and its relationship with Joy is best encouraged and preserved through any number of odd and illogical tactics which when analysed in terms of the 6D PAM incorporate techniques like ‘problem free ideals’, ‘coping questions’, ‘resource and future focused ethos’, ‘competency based’, ‘collaboration and exchange’, ‘brief trajectory’, ‘witnessing immensity’, ‘indirect methods’ and ‘formulaic strategy’ adopting an ‘expert and pathology free stance’ (see

Figure 6). Conversational ideals are those representing a desire to increase collaboration, employ non-expert practices and indirect methods neglected by most other approaches. We note how the notion of joyful simplicity itself is, in fact, complex! As such, it is easy to see how ‘keeping things simple’ can undermine much contemporary therapy that has to justify itself economically, logically and of course ethically and politically. Even the aesthetics of Joy are sometimes hard to fathom and discuss, as we have shown in the case studies, and as such, it is easily recognisable how professionals are warned to stay in their lane, stick to their agreed training strategies and diagnostic criteria. As a result, the chance of recognising and putting Joy and curiosity to work was reduced from the start.

To further the discussion, we note how the concept of health and well-being itself has traditionally been divided into at least three parts: the medical, the social and the psychological. Words, methods, and approaches have subsequently been used to position and even hijack what defines and determines one compared to another. Whilst all therapies should aim to achieve the whole again, well-being, as defined by the WHO[

32], “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”, it appears we have lost our tools to do so, to put the pieces together again. In the process, we have also forgotten how to make our clients experts in their lives. Put it simply, Joy wants to change this trajectory. In particular, and if anything, being curious and attempting to elevate the usefulness of Joy shows up how Feynman’s claim[1] that in a scientific world that is obsessed with measurements, facts and experts, “I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of uncertainty about different things, but I am not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don’t know anything about”. Such should be the case in our professional practice, be it history taking, selecting a fitting theory or arriving at our decisions in the form of a best guess at any given moment. Feynman continues: “I don’t feel frightened not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose, which is the way it really is as far as I can tell.” Joy, curiosity and surprise bring something similar into our practice. So how can we embrace this not knowing and mysterious space of Joy?

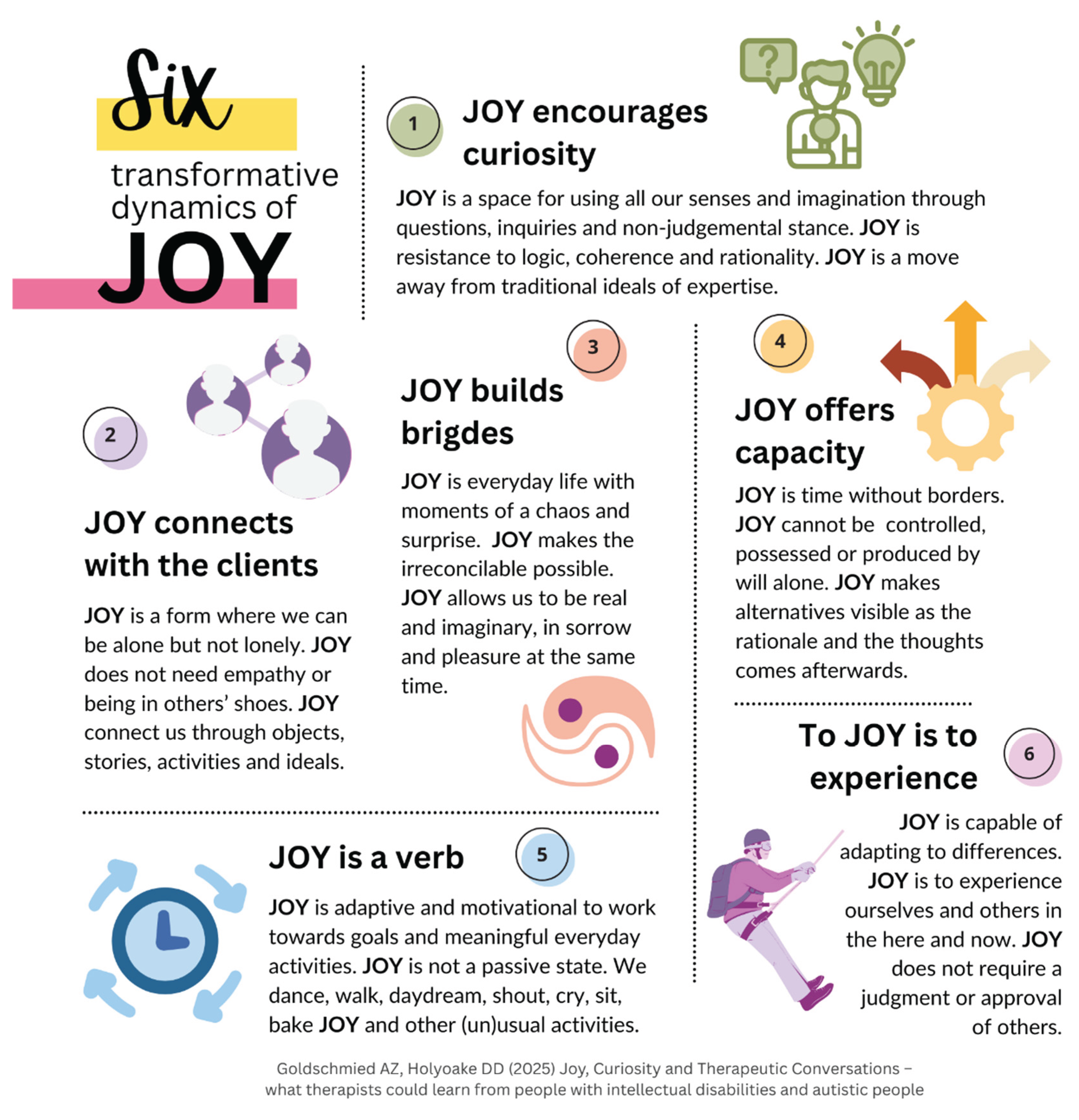

In

Figure 9, we introduce six simple ideas of the transformative dynamics of Joy for health and social care practitioners and therapists to help them employ Joy more in their therapeutic work.

First, while we often think of happiness when we describe Joy, Joy has a much broader potential. Joy does not require us to be happy in the traditional sense of the word. In fact, Joy allows us to do Joy when the situation is challenging rather than to be Joy or to feel Joy. Joy is a hopeful and constructive state of existence, yet it does not require us to employ traditional positive psychology. Joy is not simply a thought, emotion or feeling either. It follows that, second, clients who are struggling can be motivated by Joy as the situation in that Joy is neutral, it is neither right nor wrong and capable of adapting to cultural differences, including race, gender, cognitive abilities and religious beliefs. The idea that Joy is a doing and experiencing and therefore aims to offer some pragmatic outcomes, the use and value of Joy can be seen in its rejection of passivity. You can’t think or talk yourself out of a situation, but you can Joy forward. Third, Joy then acts to contradict and unite unusual oppositions and comparisons, like the aforementioned happiness and sadness. Joy connects the head and the logical with the heart and the illogical helping us move away from traditional approaches of separation and fragmentation and get closer to the ideals of a whole and holistic view of our wellbeing. Fourth, we do not have to put ourselves into others’ shoes either. Such cases show how we can Joy(n) (join) others’ Joy without empathy, as Joy is now a verb, not a feeling or emotion. Joy allows us to experience rather than do what is expected of us. Fifth, we can have Joy of past events of yesterday’s cooking, do Joy in the present, like writing this article, and work towards Joy in the future, such as my holiday in 20 days’ time. Joy does not require a direct external object or person, we can experience Joy for no apparent reason, even if Joy is often experienced together. And six, Joy does not require a qualitative or quantitative judgment from others. Joy brings aesthetics, curiosity and the potential to use all our senses with no limits on how we want to express and experience. No more age-appropriate expectations and judgements.

Now we can rethink the economics, ethics, logic and politics of Joy to further enhance our case in debates where such considerations matter. The ethics of Joy helps dislocate and suspend hasty conclusions and automatic decisions to let alternatives enter the therapeutic space that are usually the reserve of lucid and rational intentions. As a starting point and a connector, which can happen with details of others and in places with subjective objects and abstracts. To ignore its relevance is to hamper or at least deny the prospect that for some client, Joy is the experience of their own arms rather than those of the therapist holding them, keeping them contained and protected from the opposite of Joy, which we suggest is things like hate or confines. Plus, there are the economics of Joy. If we produce Joy, consume Joy, value Joy or monetise Joy, then Joy as a form of future-focused hope remains adaptive, motivational, with the intention to work towards goals and it might be easier to assimilate such demands in therapeutic work and care plans when it comes to the economics of meaningful everyday activities and connectedness. Joy connects the theoretical with the practical in real time. The logical dimensions of Joy dictate that while it may be challenging to define, it also gives us the opportunity to experiment with the space Joy creates about the typical narratives of self and others. Hence, Joy can be viewed as resistance to tested theories, logic, coherence and rationality. Everyday life is full of hopeful moments of hectic, unpredictable and fluctuating events, and so are therapeutic sessions and our clients’ aims. These are the fleeting and commonly overlooked moments when clients say things. Still, due to the politics of Joy, their seeming irrelevance is not picked upon by therapists or rejected on the basis of assumed expertise. Assumed expertise is such a dimension that habitually dispositions the clients. Joy helps us move away from traditional approaches, expertise and models like tokenism. The political dislocation of Joy invites a sharing of things we hope to experience rather than necessarily expect.

Conclusions: Joyful Simplicity Itself Is, in Fact, Beautifully Complex

In this and previous papers, we have continued to apply our novel 6D-6SF[

6,

18,

19,

26] analysis and explore the process of identifying unintended consequences of Joy. We consider our conceptual frame that is in constant development as a contemporary therapeutic technique born out of the medical and social sciences, arts and humanities by considering the symbolic, material and physical signification of therapeutic performance. To date, we believe that joyful and curious exploration of details, dimensions, and dynamics of clients comes first, and possible descriptions of dispositioning and dislocating options are second.

Our approach is embedded in the principles of solution focused practice. The 6D performative analytic helps us explore therapeutics from a novel angle, including how Joy presents itself at the various tasks of professional practice. We employ the six transformative dynamics of Joy as the central therapeutic tool in our professional practice to move away from the idea of being the expert to invoke and foster curiosity in both the clients and the therapist. In our work, be it the Joy (n) Us Workshop, academia, collaboration with clients or supervision of practitioners, we take seriously that we are not the experts but curious therapists indulging in conversations between experts. We found that Joy is an excellent choice for fostering curiosity by creating a space for future-focused questions, creative activities and alternatives to emerge.

We have started to bring together these concepts and the learning from our partners and clients with intellectual disability, mental health conditions and autism into a workable model. The reason for this is simple: most of our therapeutic models overlook the small and ordinary actions, the nuances of everyday life, like Joy, as they present in social relations. They neglect the transdisciplinary and creative exploration of the shared experiences and fail to capture that almost all everyday activities involve interactions of objects, humans and abstractions. Whilst physical approaches like a surgery can attempt to treat cancer, psychotherapy try to deal with the effects of cancer on ones’ feelings and thinking and art can help express one’s position towards their cancer and its treatment in creative ways, there is something missing that can bridge such therapeutic works leaving our clients as fragmented as our professional milieu is.

We firmly believe we need more Joy (six transformative dynamics of Joy,

Figure 9) in our care files, assessments, theory formulation, decision making and all aspects of therapeutic work, including the fundamental conversations (6D-6SF practice

Figure 6) from discussing new diagnoses through choosing the best interventions to making difficult decisions (six professional issues

Figure 8). We finish with a few joyful ideas from our clients and practice partners on what Joy looks like in the community so we can continue the conversations about our practices and say thank you to all our participants for sharing their expertise with us:

“talking to my neighbours and giving them plants I’ve grown”

“led by what individuals find joyful, respecting this is different for all”

“walking, swimming, drama”

“seeing the world with people I love”

“finding artwork by people I know”

“rescuing animals in need”

“random acts of kindness”

These are how “I know joy.”