Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Yields of the Essential Oils (EOs) from Bark, Leaves and Fruits of M. cymbarum

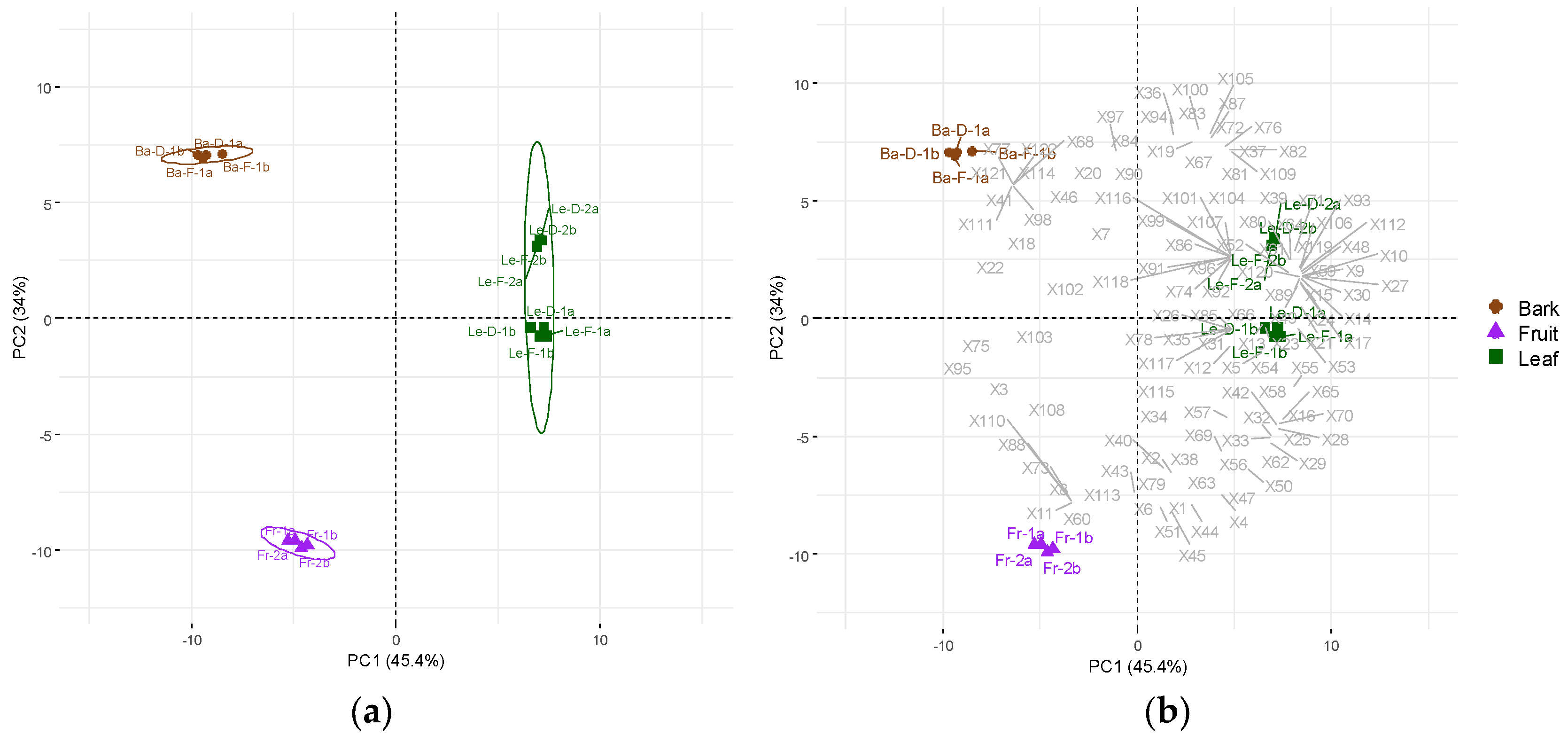

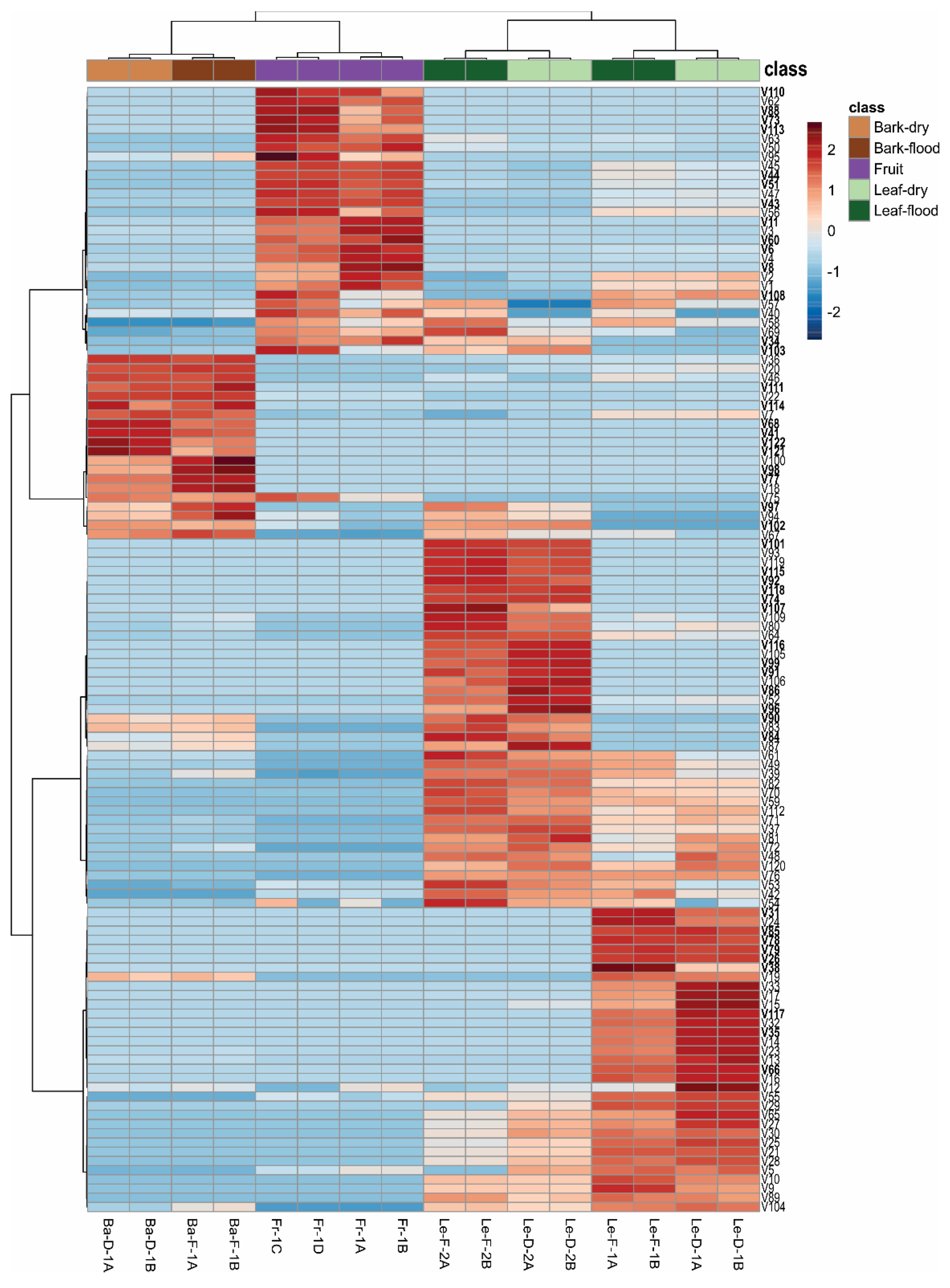

2.2. Chemical Composition and Statistical Analysis of the Essential Oils (EOs) from Bark, Leaves and Fruits of M. cymbarum

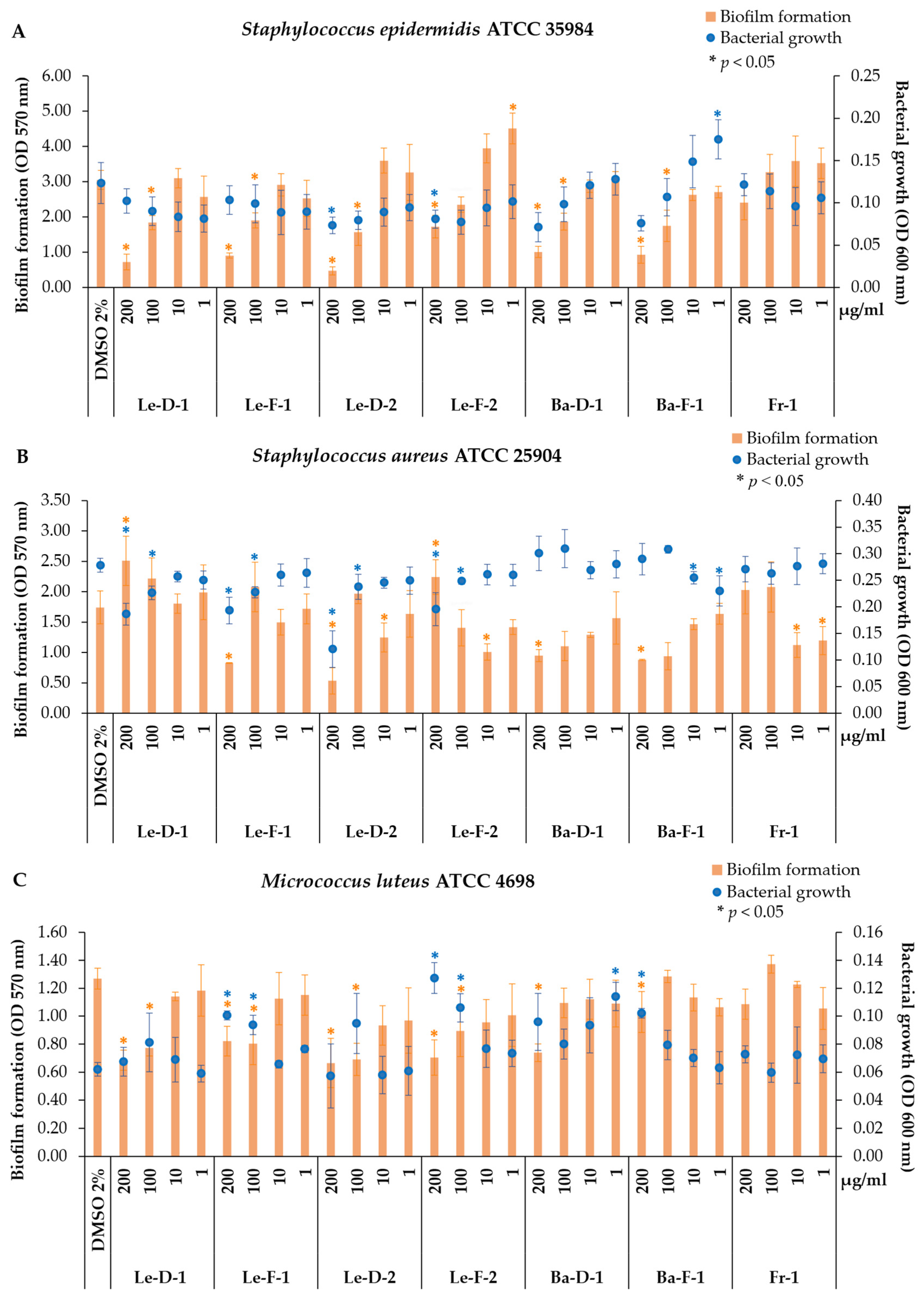

2.3. Antibiofilm and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils from M. cymbarum

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Processing the Vegetal Material

4.3. Extraction and Yield of Essential Oils (EOs) from M. cymbarum

4.4. Analysis of the Essential Oils (EOs) by Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

4.5. Data Processing

4.6. Molecular Networking

4.7. Bacterial Strains

4.8. Bacterial Growth and Biofilm Formation Assays

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EO/ EOs | Essential oil/ Essential oils |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| Le-D-1 | Leaves from chemotype-1 collected in the dry season |

| Le-F-1 | Leaves from chemotype-1 collected in the flooding season |

| Le-D-2 | Leaves from chemotype-2 collected in the dry season |

| Le-F-2 | Leaves from chemotype-2 collected in the flooding season |

| Ba-D-1 | Bark from chemotype-1 collected in the dry season |

| Ba-F-1 | Bark from chemotype-1 collected in the flooding season |

| Fr-1 | Fruit from chemotype-1 collected in the flooding season |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| PAO1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to chloramphenicol |

References

- Damasceno, C.S.B.; Fabri Higaki, N.T.; Dias, J. de F.G.; Miguel, M.D.; Miguel, O.G. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Essential Oils in the Family Lauraceae: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 1054–1072. [CrossRef]

- Farias, K.S.; Alves, F.M.; Santos-Zanuncio, V.S.; de Sousa, P.T.J.; Silva, D.B.; Carollo, C.A. Global Distribution of the Chemical Constituents and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils in Lauraceae Family: A Review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 155, 214–222. [CrossRef]

- Trofimov, D.; Cadar, D.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Rodrigues de Moraes, P.L.; Rohwer, J.G. A Comparative Analysis of Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Seven Ocotea Species (Lauraceae) Confirms Low Sequence Divergence within the Ocotea Complex. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1120. [CrossRef]

- Trofimov, D.; de Moraes, P.L.R.; Rohwer, J.G. Towards a Phylogenetic Classification of the Ocotea Complex (Lauraceae): Classification Principles and Reinstatement of Mespilodaphne. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2019, 190, 25–50. [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.A.T.; de Lima, A.A.; Wrege, M.S.; de Aguiar, A.V.; Bezerra, C. de S.; Meneses, C.H.S.G.; Lopes, R.; Ramos, S.L.F.; Paranatinga, I.L.D.; Lopes, M.T.G. Impacts of Climate Change on the Natural Distribution of Species of Lowland High and Low in the Amazon. Revista Arvore 2024, 48.

- da Silva Marinho, T.A.; Piedade, M.T.F.; Wittmann, F. Distribution and Population Structure of Four Central Amazonian High-Várzea Timber Species. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 18, 665–677. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Acevedo, A.; López-Camacho, R.; González, M.C.; Castillo, O.J.; Cervantes-Díaz, M.; Celis, M. Prospecting for Non-Timber Forest Products by Chemical Analysis of Four Species of Lauraceae from the Amazon Region of Colombia. J Wood Sci 2024, 70, 33. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.M.P.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Gottlieb, O.R. Dehydrodieugenols from Ocotea cymbarum. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 681–682. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.M.O.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Maia, G.L.A.; Chaves, M.C.O.; Braga, M.V.; De Souza, W.; Soares, R.O.A. Neolignans from Plants in Northeastern Brazil (Lauraceae) with Activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Experimental Parasitology 2010, 124, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.A.; de Moura, F.B.R.; Gomes, K.S.; da Silva Souza, D.C.; Lago, J.H.G.; Araújo, F. de A. Biseugenol from Ocotea cymbarum (Lauraceae) Attenuates Inflammation, Angiogenesis and Collagen Deposition of Sponge-Induced Fibrovascular Tissue in Mice. Inflammopharmacol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ávila, W.A.D.; Suárez, L.E.C.; Fernando, J. Composición química del aceite esencial de Ocotea cymbarum Kunth (cascarillo y/o sasafrás) de la región Orinoquia. Rev. Cubana de Plantas Medicinales 2016, 21(3), 248-260,.

- Zoghbi, M. G. B.; Andrade, e H A; Santos, A S; Silva, M H L; Maia, J G S. Constituintes Voláteis de Espécies de Lauraceae com Ocorrência na Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã—Melgaço—PA. In: Estação Científica Ferreira Penna—Dez Anos de Pesquisa, 2003, Belém, 2003.

- Passos, B.G.; De Albuquerque, R.D.D.G.; Muñoz-Acevedo, A.; Echeverria, J.; Llaure-Mora, A.M.; Ganoza-Yupanqui, M.L.; Rocha, L. Essential Oils from Ocotea Species: Chemical Variety, Biological Activities and Geographic Availability. Fitoterapia 2022, 156, 105065. [CrossRef]

- Shukis, A.J.; Wachs, Herman. Determination of Safrole in the Oil of Ocotea cymbarum. A Cryoscopic Method. Anal. Chem. 1948, 20, 248–249. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Cunha, R.M.; Dias, C.S.; Athayde-Filho, P.F.; Silva, M.S.; Da-Cunha, E.V.L.; Machado, M.I.L.; Craveiro, A.A.; Medeiros, I.A. GC-MS Analysis and Cardiovascular Activity of the Essential Oil of Ocotea Duckei. Rev. Brasileira Farmacognosia 2008, 18, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, C.; Díaz, C.; Cicció, J.F. Chemical Analysis of Essential Oils from Ocotea gomezii W.C. Burger and Ocotea morae Gómez-Laur. (Lauraceae) Collected at “Reserva Biológica Alberto M. Brenes” in Costa Rica and Their Cytotoxic Activity on Tumor Cell Lines. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 741–745. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.K.; Da Trindade, R.; Moreira, E.C.; Maia, J.G.S.; Dosoky, N.S.; Miller, R.S.; Cseke, L.J.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical Diversity, Biological Activity, and Genetic Aspects of Three Ocotea Species from the Amazon. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 1081. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.K.L.; Pedrosa, T.D.N.; de Vasconcellos, M.C.; Lima, E.S.; Veiga-Junior, V.F. Ocotea (Lauraceae) Amazonian Essential Oils Chemical Composition and Their Tyrosinase Inhibition to Use in Cosmetics. Bol.latinoam. y del Caribe de Plant.med.y aromat. 2020, 19, 519–526. [CrossRef]

- Gilardoni, G.; Montalván, M.; Vélez, M.; Malagón, O. Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Essential Oils from Different Morphological Structures of Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. Plants 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Takaku, S.; Haber, W.A.; Setzer, W.N. Leaf Essential Oil Composition of 10 Species of Ocotea (Lauraceae) from Monteverde, Costa Rica. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 525–532. [CrossRef]

- Rambo, M.A.; Soares, K.D.; Danielli, L.J.; Lana, D.F.D.; Bordignon, S.A. de L.; Fuentefria, A.M.; Apel, M.A. Biological Activities of Essential Oils from Six Genotypes of Four Ocotea Species. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 58, e181097. [CrossRef]

- Xavier, J.K.A.M.; Alves, N.S.F.; Setzer, W.N.; da Silva, J.K.R. Chemical Diversity and Biological Activities of Essential Oils from Licaria, Nectrandra and Ocotea Species (Lauraceae) with Occurrence in Brazilian Biomes. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 869. [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, G.; Guerrini, A.; Noriega, P.; Bianchi, A.; Bruni, R. Essential Oil of Wild Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) Leaves from Amazonian Ecuador. Flavour Fragrance J. 2006, 21, 674–676. [CrossRef]

- Radice, M.; Pietrantoni, A.; Guerrini, A.; Tacchini, M.; Sacchetti, G.; Chiurato, M.; Venturi, G.; Fortuna, C. Inhibitory Effect of Ocotea Quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. and Piper Aduncum L. Essential Oils from Ecuador on West Nile Virus Infection. Plant Biosyst. 2019, 153, 344–351. [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Crespo, Y.; Ureta-Leones, D.; García-Quintana, Y.; Montalván, M.; Gilardoni, G.; Malagón, O. Preliminary Predictive Model of Termiticidal and Repellent Activities of Essential Oil Extracted from Ocotea quixos Leaves against Nasutitermes corniger (Isoptera: Termitidae) Using One-Factor Response Surface Methodology Design. Agronomy 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Vullien, A.; Conde-Rojas, D. Variability of the Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil from the Amazonian Ishpingo Species (Ocotea quixos). Molecules 2021, 26, 3961. [CrossRef]

- Bruni, R.; Medici, A.; Andreotti, E.; Fantin, C.; Muzzoli, M.; Dehesa, M.; Romagnoli, C.; Sacchetti, G. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Ishpingo Essential Oil, a Traditional Ecuadorian Spice from Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) Flower Calices. Food Chem. 2004, 85, 415–421. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Sun, Z.; Lei, Z.; Yin, Z.; Qian, Z.; Tang, H.; Xie, H. Genotypic and Environmental Effects on the Volatile Chemotype of Valeriana jatamansi Jones. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Karban, R.; Wetzel, W.C.; Shiojiri, K.; Ishizaki, S.; Ramirez, S.R.; Blande, J.D. Deciphering the Language of Plant Communication: Volatile Chemotypes of Sagebrush. New Phytologist 2014, 204, 380–385. [CrossRef]

- Farias, K.D.S.; Delatte, T.; Arruda, R.D.C.D.O.; Alves, F.M.; Silva, D.B.; Beekwilder, J.; Carollo, C.A. In Depth Investigation of the Metabolism of Nectandra megapotamica Chemotypes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201996. [CrossRef]

- El Hachlafi, N.; Benkhaira, N.; Mssillou, I.; Touhtouh, J.; Aanniz, T.; Chamkhi, I.; El Omari, N.; Khalid, A.; Abdalla, A.N.; Aboulagras, S.; et al. Natural Sources and Pharmacological Properties of Santalenes and Santalols. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 214, 118567. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.T.; Pinheiro, C.G.; Bianchini, N.H.; Batista, B.F.; Diefenthaeler, J.; Brião Muniz, M.D.F.; Heinzmann, B.M. Microbiological Damage Influences the Content, Chemical Composition and the Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils in a Wild-Growing Population of Ocotea lancifolia (Schott) Mez. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2018, 30, 265–277. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Bravo, R.; Lin, P.-A.; Waterman, J.M.; Erb, M. Dynamic Environmental Interactions Shaped by Vegetative Plant Volatiles. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 840–865. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.D.P.; Tondolo, J.S.M.; Schindler, B.; Silva, D.T.D.; Pinheiro, C.G.; Longhi, S.J.; Mallmann, C.A.; Heinzmann, B.M. Seasonal Influence on the Essential Oil Production of Nectandra Megapotamica (Spreng.) Mez. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 2015, 58, 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, E.D.O.; Vieira, M.A.R.; Ferreira, M.I.; Fernandes Junior, A.; Marques, M.O.M.; Minatel, I.O.; Albano, M.; Sambo, P.; Lima, G.P.P. Seasonality Effects on Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Activity and Essential Oil Yield of Three Species of Nectandra. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204132. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.T.D.; Bianchini, N.H.; Amaral, L.D.P.; Longhi, S.J.; Heinzmann, B.M. Análise do Efeito da Sazonalidade Sobre o Rendimento do Óleo Essencial das Folhas de Nectandra grandiflora Nees. Rev. Árvore 2015, 39, 1065–1072. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.F. de; Aparecido, L.E. de O.; Torsoni, G.B.; Rolim, G. de S. Climate Change Assessment in Brazil: Utilizing the Köppen-Geiger (1936) Climate Classification. Rev. bras. meteorol. 2024, 38, e38230001. [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Lotfalizadeh, M.; Badpeyma, M.; Shakeri, A.; Soheili, V. From Plants to Antimicrobials: Natural Products against Bacterial Membranes. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36, 33–52. [CrossRef]

- Ruhal, R.; Kataria, R. Biofilm Patterns in Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Microbiological Research 2021, 251, 126829. [CrossRef]

- Aljaafari, M.N.; AlAli, A.O.; Baqais, L.; Alqubaisy, M.; AlAli, M.; Molouki, A.; Ong-Abdullah, J.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. An Overview of the Potential Therapeutic Applications of Essential Oils. Molecules 2021, 26, 628. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, M.; Hidalgo, W.; Stashenko, E.; Torres, R.; Ortiz, C. Essential Oils of Aromatic Plants with Antibacterial, Anti-Biofilm and Anti-Quorum Sensing Activities against Pathogenic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 147. [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Tabana, Y.M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ahamed, M.B.K.; Ezzat, M.O.; Majid, A.S.A.; Majid, A.M.S.A. The Anticancer, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of the Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene from the Essential Oil of Aquilaria Crassna. Molecules 2015, 20, 11808–11829. [CrossRef]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcus epidermidis — the “accidental” Pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009, 7, 555–567. [CrossRef]

- Severn, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus epidermidis and Its Dual Lifestyle in Skin Health and Infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Verderosa, A.D.; Totsika, M.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E. Bacterial Biofilm Eradication Agents: A Current Review. Frontiers in Chemistry 2019, 7.

- Elaissi, A.; Rouis, Z.; Salem, N.A.B.; Mabrouk, S.; ben Salem, Y.; Salah, K.B.H.; Aouni, M.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; et al. Chemical Composition of 8 Eucalyptus Species’ Essential Oils and the Evaluation of Their Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antiviral Activities. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12, 81. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Verma, S.K.; Chauhan, A.; Venkatesha, K.; Verma, R.S.; Singh, V.R.; Darokar, M.P.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Padalia, R.C. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Melaleuca bracteata Essential Oil from India: A Natural Source of Methyl Eugenol. Natural Product Communications 2017, 12, 1934578X1701200. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Ocimum basilicum L. (Sweet Basil) from Western Ghats of North West Karnataka, India. Ancient Sci Life 2014, 33, 149. [CrossRef]

- Francomano, F.; Caruso, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Fazio, A.; La Torre, C.; Ceramella, J.; Mallamaci, R.; Saturnino, C.; Iacopetta, D.; Sinicropi, M.S. β-Caryophyllene: A Sesquiterpene with Countless Biological Properties. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5420. [CrossRef]

- Selestino Neta, M.C.; Vittorazzi, C.; Guimarães, A.C.; Martins, J.D.L.; Fronza, M.; Endringer, D.C.; Scherer, R. Effects of β-Caryophyllene and Murraya paniculata Essential Oil in the Murine Hepatoma Cells and in the Bacteria and Fungi 24-h Time–Kill Curve Studies. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 190–197. [CrossRef]

- Merghni, A.; Marzouki, H.; Hentati, H.; Aouni, M.; Mastouri, M. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activities of Laurus nobilis L. Essential Oil against Staphylococcus aureus Strains Associated with Oral Infections. Current Research in Translational Medicine 2016, 64, 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Dib, J.R.; Liebl, W.; Wagenknecht, M.; Farías, M.E.; Meinhardt, F. Extrachromosomal Genetic Elements in Micrococcus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 97, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Nava, G.; Mohamed, A.; Yanez-Bello, M.A.; Trelles-Garcia, D.P. Advances in Medicine and Positive Natural Selection: Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis Due to Biofilm Producer Micrococcus luteus. IDCases 2020, 20, e00743. [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, E.E.; Macedo, J.; Vieira, T.M.; Valsecchi, J.; Calvimontes, J.; Marmontel, M.; Queiroz, H.L. Ciclo Hidrológico nos Ambientes de Várzea da Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá—Médio Rio Solimões, Período De 1990 A 2008. Scientific Magazine UAKARI 2009, 5(1), 61-87.

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, Ill, 2007; ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4.

- Babushok, V.I.; Linstrom, P.J.; Zenkevich, I.G. Retention Indices for Frequently Reported Compounds of Plant Essential Oils. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2011, 40, 043101. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and Community Curation of Mass Spectrometry Data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat Biotechnol 2016, 34, 828–837. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- Trentin, D. da S.; Giordani, R.B.; Zimmer, K.R.; da Silva, A.G.; da Silva, M.V.; Correia, M.T. dos S.; Baumvol, I.J.R.; Macedo, A.J. Potential of Medicinal Plants from the Brazilian Semi-Arid Region (Caatinga) against Staphylococcus epidermidis Planktonic and Biofilm Lifestyles. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2011, 137, 327–335. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2003, https://www.R-project.org/.

- Kassambara A, Mundt F (2020). factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R package version 1.0.7, 2020, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra.

- Oksanen J, Simpson G, Blanchet F, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin P, O’Hara R, Solymos P, Stevens M, Szoecs E, Wagner H, Barbour M, Bedward M, Bolker B, Borcard D, Carvalho G, Chirico M, De Caceres M, Durand S, Evangelista H, FitzJohn R, Friendly M, Furneaux B, Hannigan G, Hill M, Lahti L, McGlinn D, Ouellette M, Ribeiro Cunha E, Smith T, Stier A, Ter Braak C, Weedon J (2022). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4, 2022, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; MacDonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a Unified Platform for Metabolomics Data Processing, Analysis and Interpretation. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, W398–W406. [CrossRef]

| VOC | IR* | Compound Name | Le-F-1 | Le-D-1 | Le-F-2 | Le-D-2 | Fr-1 | Ba-F-1 | Ba-D-1 | Class** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 938 | α-Pinene | 1.71 ±0.021 | 1.88 ±0.247 | 0.1 ±0.007 | 0.38 ±0.007 | 3.32 ±0.583 | 0.21 ±0.021 | 0.08 ±0.001 | HM |

| V2 | 979 | β-Pinene | 0.83 ±0.007 | 0.87 ±0.078 | <0.1 | 0.26 ±0.007 | 1.2 ±0.289 | 0.13 ±0.007 | 0.08 ±0.007 | HM |

| V3 | 990 | Myrcene | - | - | - | - | 0.6 ±0.134 | <0.1 | <0.1 | HM |

| V4 | 1004 | α-Phellandrene | 0.11 ±0.007 | 0.11 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.76 ±0.246 | - | - | HM |

| V5 | 1026 | p-Cymene | 2.64 ±0.078 | 2.59 ±0.198 | 0.2 ±0.007 | 2.04 ±0.042 | 0.96 ±0.237 | <0.1 | <0.1 | HM |

| V6 | 1031 | Limonene | 2.37 ±0.042 | 2.89 ±0.233 | 0.33 ±0.007 | 1.38 ±0.028 | 19.32 ±2.79 | 0.17 ±0 | 0.22 ±0.014 | HM |

| V7 | 1034 | 1,8-Cineole | 1.73 ±0.007 | 1.9 ±0.106 | 0.22 ±0.007 | 0.76 ±0.021 | 0.62 ±0.114 | 3.33 ±0.177 | 3.44 ±0.184 | OM |

| V8 | 1050 | trans-β-Ocimene | - | - | - | - | 0.54 ±0.179 | - | - | HM |

| V9 | 1074 | cis-Linalool oxide | 0.38 ±0.007 | 0.28 ±0.007 | 0.21 ±0.002 | 0.21 ±0.007 | - | - | - | OM |

| V10 | 1088 | trans-Linalool oxide | 0.27 ±0.007 | 0.22 ±0.001 | 0.17 ±0.001 | 0.16 ±0.001 | - | - | - | OM |

| V11 | 1088 | Terpinolene | - | - | - | - | 0.5 ±0.074 | - | - | HM |

| V12 | 1098 | Linalool | 0.11 ±0.007 | 0.34 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.1 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.1 ±0.007 | 0.08 ±0.014 | OM |

| V13 | 1141 | trans-Pinocarveol | 0.86 ±0.021 | 1.13 ±0.113 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | OM |

| V14 | 1144 | cis-Verbenol | 0.26 ±0.007 | 0.37 ±0.001 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | - | OM |

| V15 | 1148 | trans-Verbenol | 0.63 ±0.014 | 1.3 ±0.014 | <0.1 | 0.2 ±0.007 | - | - | - | OM |

| V16 | 1153 | NI (m/z 138) | 0.67 ±0.035 | 0.8 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V17 | 1165 | Pinocarvone | 0.27 ±0.007 | 0.49 ±0.001 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | - | OM |

| V18 | 1169 | Borneol | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.88 ±0.049 | 0.65 ±0.396 | OM |

| V19 | 1170 | p-Mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol | 0.55 ±0.021 | 0.5 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | <0.1 | 0.35 ±0.042 | OM |

| V20 | 1179 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0.55 ±0.007 | 0.76 ±0.007 | 0.18 ±0.007 | 0.41 ±0.021 | 0.18 ±0.031 | 2.07 ±0.014 | 1.97 ±0.021 | OM |

| V21 | 1188 | Cryptone | 5.03 ±0.014 | 5.08 ±0.134 | 1.94 ±0.028 | 2.64 ±0.035 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | Ke |

| V22 | 1192 | α-Terpineol | 0.42 ±0.014 | 0.64 ±0.007 | 0.23 ±0.007 | 0.29 ±0.007 | 0.75 ±0.049 | 4.5 ±0.078 | 4.38 ±0.042 | OM |

| V23 | 1197 | Myrtenal | 0.72 ±0.014 | 1.1 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | OM |

| V24 | 1210 | Verbenone | 1.29 ±0.021 | 0.86 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | - | OM |

| V25 | 1221 | trans-Carveol | 0.62 ±0.007 | 0.7 ±0.007 | 0.22 ±0.007 | 0.34 ±0.014 | <0.1 | - | - | OM |

| V26 | 1226 | NI | 0.57 ±0.007 | 0.56 ±0.007 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V27 | 1243 | p-Isopropylbenzaldehyde (p-Cumic aldehyde) | 1.94 ±0.057 | 2.58 ±0.028 | 0.95 ±0.035 | 1.62 ±0.049 | - | - | - | OM |

| V28 | 1247 | Carvone | 0.8 ±0.028 | 0.89 ±0.007 | 0.35 ±0.007 | 0.52 ±0.014 | <0.1 | - | - | OM |

| V29 | 1276 | p-Menth-1-en-7-al | 0.63 ±0.007 | 0.67 ±0.001 | <0.1 | 0.26 ±0.014 | <0.1 | - | - | OM |

| V30 | 1292 | p-Cymen-7-ol | 0.61 ±0.028 | 0.64 ±0.014 | 0.32 ±0.007 | 0.52 ±0.035 | - | - | - | OM |

| V31 | 1308 | NI | 0.74 ±0.014 | 0.59 ±0.007 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V32 | 1331 | NI | 1.04 ±0.014 | 1.39 ±0.014 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V33 | 1334 | NI | 0.61 ±0.007 | 1.05 ±0.028 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V34 | 1337 | δ-Elemene | - | - | 0.26 ±0.007 | 0.26 ±0.014 | 0.37 ±0.045 | - | - | HS |

| V35 | 1339 | NI | 1.57 ±0.007 | 2.12 ±0.014 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V36 | 1351 | α-Cubebene | 0.18 ±0.007 | 0.21 ±0.014 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | 1.1 ±0.049 | 1.12 ±0.014 | HS |

| V37 | 1368 | Cyclosativene | 0.32 ±0.007 | 0.33 ±0.007 | 0.62 ±0.007 | 0.68 ±0.007 | - | <0.1 | <0.1 | HS |

| V38 | 1370 | NI | 1.07 ±0.035 | 0.35 ±0.001 | - | - | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V39 | 1376 | α-Copaene | 1.39 ±0.021 | 0.91 ±0.014 | 1.65 ±0.021 | 1.7 ±0.014 | 0.26 ±0.024 | 0.95 ±0.049 | 0.53 ±0.014 | HS |

| V40 | 1391 | β-Elemene | 0.18 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.22 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.32 ±0.051 | <0.1 | <0.1 | HS |

| V41 | 1411 | Methyl eugenol | - | - | - | - | - | 37.49 ±1.29 | 43.61 ±0.49 | Ph |

| V42 | 1419 | β-Caryophyllene | 7.91 ±0.926 | 4.77 ±0.106 | 8.99 ±0.071 | 7.61 ±0.113 | 2.97 ±0.093 | - | - | HS |

| V43 | 1421 | α-Santalene | 6.17 ±0.085 | 6.29 ±0.226 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 26.41 ±0.50 | 1.69 ±0.028 | 1.11 ±0.028 | HS |

| V44 | 1437 | trans-α-Bergamotene | 2.85 ±0.042 | 1.94 ±0.014 | 0.79 ±0.007 | 0.33 ±0.007 | 8.18 ±0.181 | 0.27 ±0.021 | 0.2 ±0.014 | HS |

| V45 | 1439 | α-Guaiene | 0.68 ±0.007 | 0.45 ±0.001 | 0.21 ±0.001 | <0.1 | 1.95 ±0.054 | <0.1 | <0.1 | HS |

| V46 | 1444 | 6,9-Guaiadiene | 0.29 ±0.007 | 0.15 ±0.021 | 0.16 ±0.001 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.79 ±0.042 | 0.79 ±0.014 | HS |

| V47 | 1448 | epi-β-Santalene | 0.3 ±0.007 | 0.37 ±0.049 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.61 ±0.107 | - | - | HS |

| V48 | 1451 | Allo-Aromadendrene | <0.1 | 0.3 ±0.035 | 0.31 ±0.007 | 0.28 ±0.021 | - | - | - | HS |

| V49 | 1454 | α-Humulene | 0.72 ±0.007 | 0.45 ±0.021 | 0.92 ±0.007 | 0.85 ±0.021 | <0.1 | 0.16 ±0.007 | <0.1 | HS |

| V50 | 1458 | trans-β-Farnesene | 0.24 ±0.007 | 0.14 ±0.021 | 0.35 ±0.007 | 0.22 ±0.001 | 1.47 ±0.115 | - | - | HS |

| V51 | 1462 | β-Santalene | 3.77 ±0.014 | 2.74 ±0.021 | 2.05 ±0.007 | 1.24 ±0.014 | 12.02 ±0.64 | 0.78 ±0.049 | 0.45 ±0.021 | HS |

| V52 | 1470 | Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,8a-dimethyl-7-(1-methylethenyl)-, (1R,7S,8aS)- | 0.58 ±0.007 | 0.9 ±0.001 | 2.89 ±0.014 | 3.73 ±0.085 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | HS |

| V53 | 1477 | γ-Muurolene | 1.45 ±0.014 | 0.71 ±0.007 | 2.19 ±0.007 | 1.75 ±0.071 | 0.65 ±0.092 | 0.25 ±0.007 | <0.1 | HS |

| V54 | 1480 | α-Amorphene | 0.31 ±0.021 | <0.1 | 0.54 ±0.007 | 0.36 ±0.007 | 0.14 ±0.158 | <0.1 | 0.07 ±0 | HS |

| V55 | 1485 | β-Selinene | 2.85 ±0.021 | 3.14 ±0.007 | 1.49 ±0.021 | 1.34 ±0.021 | 0.84 ±0.241 | 0.06 ±0.014 | 0.05 ±0 | HS |

| V56 | 1488 | Eremophilene | 0.3 ±0.007 | 0.27 ±0.007 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.66 ±0.18 | - | - | HS |

| V57 | 1491 | β-cadinene | 0.45 ±0.014 | 0.27 ±0.001 | 0.44 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.42 ±0.132 | 0.2 ±0.014 | 0.16 ±0.014 | HS |

| V58 | 1494 | Viridiflorene | 1.09 ±0.007 | 0.73 ±0.014 | 1.3 ±0.014 | 0.67 ±0.014 | 1 ±0.202 | 0.19 ±0.035 | 0.17 ±0.007 | HS |

| V59 | 1498 | NI | 0.64 ±0.021 | 0.58 ±0.028 | 0.9 ±0.021 | 0.74 ±0.007 | - | - | - | |

| V60 | 1498 | α-Selinene | - | - | - | - | 0.38 ±0.065 | - | - | HS |

| V61 | 1499 | α-Muurolene | 0.51 ±0.007 | 0.23 ±0.001 | 0.78 ±0.049 | 0.56 ±0.014 | <0.1 | 0.17 ±0.007 | 0.16 ±0.007 | HS |

| V62 | 1505 | α-Bulnesene | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.39 ±0.056 | - | - | HS |

| V63 | 1509 | β-Bisabolene | 0.43 ±0.014 | 0.26 ±0.021 | 0.66 ±0.007 | 0.26 ±0.001 | 2.12 ±0.221 | <0.1 | 0.01 ±0 | HS |

| V64 | 1514 | γ-Cadinene | 1.28 ±0.028 | 0.88 ±0.014 | 3.1 ±0.014 | 2.93 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.34 ±0.007 | 0.21 ±0.007 | HS |

| V65 | 1517 | NI | 0.63 ±0.007 | 0.93 ±0.014 | 0.32 ±0.007 | 0.51 ±0.014 | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V66 | 1521 | NI | 2.61 ±0.007 | 3.02 ±0.035 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V67 | 1525 | δ-Cadinene | 3.37 ±0.049 | 1.93 ±0.021 | 5.14 ±0.014 | 3.62 ±0.028 | 0.52 ±0.119 | 7.41 ±0.332 | 6.29 ±0.304 | HS |

| V68 | 1528 | Myristicin | - | - | - | - | - | 7.37 ±0.205 | 9.6 ±0.219 | Ph |

| V69 | 1534 | trans-γ-Bisabolene | 0.98 ±0.014 | 0.37 ±0.007 | 2.61 ±0.028 | 1.21 ±0.021 | 1.97 ±0.234 | 0.43 ±0.028 | 0.21 ±0.014 | HS |

| V70 | 1540 | α-Cadinene | 0.27 ±0.021 | 0.22 ±0.014 | 0.45 ±0.021 | 0.38 ±0.021 | <0.1 | - | - | HS |

| V71 | 1543 | NI | 1.26 ±0.007 | 1.46 ±0.113 | 2.06 ±0.021 | 2.14 ±0.007 | <0.1 | 0.32 ±0.064 | 0.19 ±0 | |

| V72 | 1545 | α-Calacorene | 0.49 ±0.028 | 0.75 ±0.057 | 0.79 ±0.007 | 0.87 ±0.078 | - | 0.3 ±0.042 | 0.16 ±0.007 | HS |

| V73 | 1545 | trans-α-bisabolene | - | - | - | - | 0.42 ±0.113 | - | - | HS |

| V74 | 1547 | NI | - | - | 2.99 ±0.014 | 3.08 ±0.035 | - | - | - | |

| V75 | 1551 | α-Elemol | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.54 ±0.318 | 0.7 ±0.042 | 0.79 ±0.028 | OS |

| V76 | 1558 | NI | 3.35 ±0.007 | 3.36 ±0.071 | 3.32 ±0.028 | 3.45 ±0.007 | - | 0.5 ±0.028 | 0.54 ±0.014 | |

| V77 | 1564 | Elemicin | - | - | - | - | - | 11.89 ±0.17 | 8.82 ±0.014 | Ph |

| V78 | 1565 | NI | 1.53 ±0.028 | 1.47 ±0.057 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V79 | 1567 | NI | 0.83 ±0.014 | 0.8 ±0.007 | - | - | <0.1 | - | - | |

| V80 | 1579 | Spathulenol | 0.19 ±0.014 | 0.3 ±0.028 | 0.83 ±0.014 | 0.66 ±0.014 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | OS |

| V81 | 1584 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1.39 ±0.205 | 2.92 ±0.113 | 2.88 ±0.007 | 3.96 ±0.389 | - | <0.1 | 0.22 ±0.007 | OS |

| V82 | 1589 | NI (m/z = 234) | 5.38 ±0.191 | 5.87 ±0.134 | 10.99 ±0.057 | 9.84 ±0.134 | - | 0.47 ±0.042 | 0.58 ±0.007 | |

| V83 | 1603 | Rosifoliol | 0.26 ±0.021 | 0.3 ±0.007 | 1.41 ±0.071 | 1.11 ±0.049 | - | 0.87 ±0.049 | 0.91 ±0.049 | OS |

| V84 | 1605 | NI | - | - | 1.04 ±0.007 | 0.83 ±0.099 | - | 0.45 ±0.035 | 0.24 ±0.021 | |

| V85 | 1605 | NI | 0.85 ±0.021 | 0.86 ±0.035 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V86 | 1608 | NI | - | - | 0.54 ±0.014 | 0.74 ±0.078 | - | - | - | |

| V87 | 1611 | Humulene epoxide II | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.46 ±0.021 | 0.79 ±0.035 | - | 0.29 ±0.007 | 0.2 ±0.028 | OS |

| V88 | 1614 | Tetradecanal | - | - | - | - | 0.21 ±0.065 | - | - | |

| V89 | 1614 | Viridiflorol | 0.53 ±0.028 | 0.49 ±0.035 | 0.47 ±0.002 | 0.36 ±0.028 | - | - | - | OS |

| V90 | 1618 | 1,10-di-epi-Cubenol | - | - | 1.29 ±0.156 | 1.19 ±0.064 | - | 0.81 ±0.042 | 0.73 ±0.134 | OS |

| V91 | 1620 | NI | - | - | 1.84 ±0.17 | 2.06 ±0.042 | - | - | - | |

| V92 | 1622 | epi-γ-Eudesmol | - | - | 0.77 ±0.014 | 0.68 ±0.035 | - | - | - | OS |

| V93 | 1623 | NI (m/z=236) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.04 ±0.014 | 0.96 ±0.021 | - | - | - | |

| V94 | 1630 | 1-epi-Cubenol | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.52 ±0.007 | 0.39 ±0.007 | 0.2 ±0.082 | 0.84 ±0.156 | 0.48 ±0.021 | OS |

| V95 | 1634 | γ-Eudesmol | - | - | - | - | 0.5 ±0.258 | 0.23 ±0.064 | 0.1 ±0.014 | OS |

| V96 | 1638 | Hinesol | - | - | 0.65 ±0.021 | 1.17 ±0.035 | - | - | - | OS |

| V97 | 1643 | 1,2,3,4,4a,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-1-Naphthalenol, | - | - | 0.33 ±0.007 | 0.18 ±0.014 | - | <0.1 | <0.1 | OS |

| V98 | 1645 | epi-α-Cadinol | - | - | - | - | - | 1.19 ±0.064 | 0.61 ±0.014 | OS |

| V99 | 1645 | NI | - | - | 0.59 ±0.028 | 0.7 ±0.028 | - | - | - | |

| V100 | 1649 | α-Muurolol (=Torreyol) | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | - | 0.33 ±0.057 | 0.17 ±0.014 | OS |

| V101 | 1651 | NI | - | - | 3.01 ±0.042 | 2.87 ±0.001 | - | - | - | |

| V102 | 1652 | β-Eudesmol | - | - | 2.43 ±0.057 | 2.62 ±0.092 | 0.62 ±0.398 | 2.27 ±0.12 | 2.52 ±0.028 | OS |

| V103 | 1655 | α-Eudesmol | - | - | 0.5 ±0.071 | 0.73 ±0.021 | 0.62 ±0.419 | <0.1 | <0.1 | OS |

| V104 | 1657 | α-Cadinol | 2.74 ±0.028 | 2.9 ±0.092 | 2.07 ±0.049 | 1.8 ±0.028 | <0.1 | 1.53 ±0.085 | 0.73 ±0.028 | OS |

| V105 | 1660 | NI | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.28 ±0.028 | 1.58 ±0.021 | - | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| V106 | 1664 | NI | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.4 ±0.057 | 0.56 ±0.035 | - | - | - | |

| V107 | 1671 | NI | - | - | 0.49 ±0.014 | 0.27 ±0.049 | - | - | - | |

| V108 | 1671 | β-Bisabolol | 0.46 ±0.042 | 0.51 ±0.014 | - | - | 0.47 ±0.242 | <0.1 | 0.07 ±0.007 | OS |

| V109 | 1676 | Cadalene | 0.19 ±0.078 | 0.13 ±0.028 | 0.91 ±0.014 | 0.7 ±0.007 | - | 0.17 ±0.035 | 0.08 ±0.007 | HS |

| V110 | 1678 | cis-α-Santalol | - | - | - | - | 0.78 ±0.161 | - | - | OS |

| V111 | 1678 | Bulnesol | - | - | - | - | - | 1.69 ±0.247 | 1.47 ±0.099 | OS |

| V112 | 1680 | NI | 1.04 ±0.099 | 1.41 ±0.014 | 2.08 ±0.007 | 1.64 ±0.035 | - | - | - | |

| V113 | 1680 | NI | - | - | - | - | 0.6 ±0.171 | - | - | |

| V114 | 1680 | NI | - | - | - | - | - | 0.65 ±0.085 | 0.6 ±0.163 | |

| V115 | 1687 | α-Bisabolol | - | - | 0.61 ±0.014 | 0.55 ±0.014 | <0.1 | - | - | OS |

| V116 | 1708 | NI | - | - | 0.76 ±0.001 | 0.87 ±0.014 | - | - | - | |

| V117 | 1710 | NI | 0.85 ±0.014 | 1.12 ±0.057 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| V118 | 1729 | NI | - | - | 0.62 ±0.014 | 0.62 ±0.014 | - | - | - | |

| V119 | 1745 | NI | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.86 ±0.021 | 0.76 ±0.021 | - | - | - | |

| V120 | 1751 | NI | 0.48 ±0.007 | 0.67 ±0.021 | 0.52 ±0.014 | 0.69 ±0.007 | - | - | - | |

| V121 | 1764 | Guaiol acetate | - | - | - | - | - | 0.28 ±0.057 | 0.47 ±0.028 | OS |

| V122 | 1806 | NI | - | - | - | - | - | 1.2 ±0.071 | 1.8 ±0.134 | |

| Hydrocarbon monoterpene | 7.6 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 28.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | HM | ||

| Hydrocarbon sesquiterpene | 39.5 | 29.9 | 39.9 | 31.7 | 65.1 | 15.6 | 12.4 | HS | ||

| Ketone | 5.0 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Ke | ||

| Oxygenated monoterpene | 12.6 | 15.3 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 1.7 | 11.3 | 10.9 | OM | ||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpene | 5.1 | 6.9 | 14.9 | 15.8 | 3.8 | 11.8 | 9.7 | OS | ||

| Phenylpropanoid | - | - | - | - | - | 56.7 | 62.0 | Ph | ||

| Not identified (unknown) | 26.7 | 29.4 | 36.4 | 35.6 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 4.0 | NI | ||

| Total (%) | 96.08 | 94.45 | 96.28 | 94.90 | 99.60 | 99.75 | 99.55 | |||

| Yield (v/w %) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).