Introduction

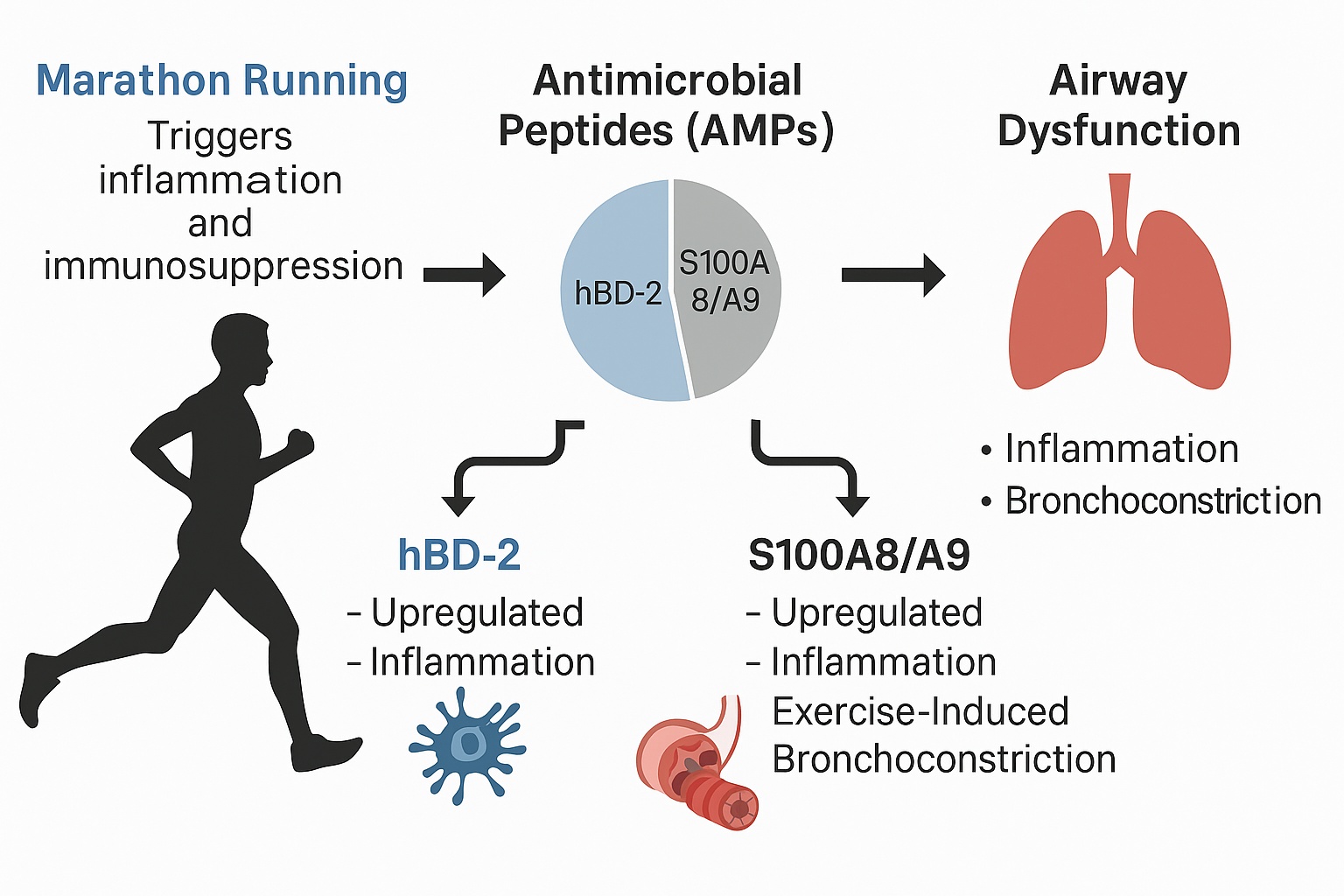

Marathon Running and Its Impact on Respiratory and Immune System

Marathon running, an endurance sport covering 42.195 kilometers (26.2 miles), exerts substantial physical stress on the body. While moderate physical activity is well-documented to prevent or improve conditions like obesity, hypertension [

1], diabetes [

2], osteoporosis [

3], cancer [

4], and aging-related decline [

5], prolonged intense exercise, such as marathon running, triggers significant physiological responses. These include the release of proinflammatory markers and the activation of acute inflammatory pathways [

6]. Conversely, it may also induce temporary immunosuppression, increasing susceptibility to infections, particularly in the upper respiratory tract [

7,

8].

This phenomenon, known as the "open window" theory, proposes that intense physical exertion temporarily weakens the immune system, creating a period of heightened vulnerability to pathogens.[

6,

7,

8]

Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) and Respiratory Defense

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) constitute a fundamental component of the innate immune defense, serving as a primary defense against a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi [

7,

9,

10]. Among these, human beta-defensin 2 (hBD-2) and lactoferrin are well-characterized for both their antimicrobial efficacy and immunomodulatory functions. hBD-2 contributes to host defense by targeting diverse pathogens and is also implicated in modulating immune responses and serving as a potential biomarker of inflammation [

11]. In addition to their direct antimicrobial activity, hBD-2 and lactoferrin orchestrate various immune processes, including immune cell recruitment, regulation of inflammatory responses, and facilitation of tissue repair [

12]. Recent research increasingly underscores the pivotal role of AMPs in maintaining airway immune defense, particularly under conditions of physical stress such as exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB). Secreted by epithelial cells within the respiratory tract, they serve as key sentinels against microbial invasion. Evidence suggests that exercise may modulate both the expression and activity of AMPs, potentially influencing the host’s susceptibility to respiratory infections at mucosal surfaces [

13].

Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction (EIB)

EIB is a condition characterized by the narrowing of the airways during or after exercise, manifesting as coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. It is especially prevalent in athletes and individuals engaged in high-intensity endurance sports like running, swimming, and cycling [

14,

15,

16]. EIB affects 5–20% of the general population, and in non-asthmatic individuals, where exercise is the sole trigger. The prevalence ranges from 8–20%. Environmental factors, such as exposure to cold air, pollutants, or allergens, can exacerbate symptoms [

17,

18].

The pathophysiology of EIB involves the rapid inhalation of large volumes of air during exercise, which cools and dries the airways, leading to inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness [

18].

Human-Beta Defensin 2

hBD-2 is secreted by various cell types in response to microorganisms or pro-inflammatory cytokines [

11,

19]. Beyond its antimicrobial activity, hBD-2 facilitates immune cell chemotaxis and activates Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [

11,

20]. In smokers, increased expression of beta-defensins in lung tissue highlights hBD-2's role in protecting the respiratory tract from oxidative stress and infections linked to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Conversely, elevated hBD-2 and hBD-4 levels have been specifically detected in patients with mucoid

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, correlating with serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels [

21,

22]. Mutations in genes encoding hBD-2 (DEFB4A and DEFB4B) have been associated with atopic asthma in children [

23,

24]. Elevated levels of hBD-2 have also been observed in chronic respiratory infections and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for disease progression [

21,

25]. We therefore hypothesized that hBD-2 is upregulated during intense exercise, such as marathon running, and plays a role in the development of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

S100A8/A9

S100A8/A9, also known as calprotectin, is a heterodimer of calcium-binding proteins from the S100 family. It is upregulated in numerous inflammatory conditions, including asthma, diabetes, and arthritis and chronic inflammatory bowel disease [

26]. This complex exhibits antimicrobial activity and promotes immune cell recruitment, playing a critical role in the innate immune response [

27]. Elevated levels of S100A8/A9 have been linked to airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Studies have shown that serum S100A8/A9 levels correlate with lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness, suggesting that S100A8/A9 serves as a biomarker for asthma [

28,

29].

Consequently, it is hypothesized that S100A8/A9 may contribute to exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB). Experimental evidence suggests that inhibiting S100A8/A9 improves pathological conditions in murine models. For instance, S100A9 knockout mice, which lack the subunit that stabilizes the functional S100 protein heterodimer, exhibit attenuated hallmarks of asthma, including airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway remodeling in a murine model of allergic asthma [

27].

In summary, S100A8/A9 plays a significant role in inflammatory conditions such as asthma, contributing to airway hyperresponsiveness. Inhibition of this complex in murine models has shown improvement in pathological conditions, supporting the hypothesis that S100A8/A9 may contribute to EIB.

Major Basic Protein (MBP)

MBP, a low molecular weight, highly cationic protein released by eosinophils, is implicated in airway mucosal injury and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Eosinophils and their released proteins play a central role in allergic airway inflammation [

30,

31]. MBP has cytotoxic effects on helminths, bacteria, and mammalian cells and is found deposited on damaged lung epithelial tissue in asthma patients [

32,

33,

34,

35]. MBP also contributes to bronchial hyperreactivity and stimulates cytokine production in activated cells [

36,

37]. Research indicates that sputum polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are increased in non-asthmatic runners both after a marathon and at baseline, suggesting that exercise-associated inflammatory airway changes may involve eosinophil activation and MBP release [

38]. To investigate its role in bronchial hyperresponsiveness, we have measured MBP levels in athletes, such as half-marathoners and marathoners, to evaluate their potential contribution to airway dysfunction, similar to asthma´.

Angiogenin

Angiogenin, a member of the ribonuclease family, circulates freely in human plasma and exhibits a broad spectrum of functions, including wound healing and tissue repair [

39]. It plays a key role in angiogenesis, particularly in malignant diseases, where it was first identified in carcinoma [

40,

41]. Additionally, it acts as an acute-phase reactant [

40,

42,

43]. Olson et al. [

43] reported that angiogenin levels were elevated threefold in hospitalized patients compared to healthy controls. Based on this, we hypothesized that angiogenin functions as an acute-phase reactant during prolonged endurance activities, such as marathon running. Angiogenesis is critical to wound repair. Newly formed blood vessels participate in provisional granulation tissue formation and provide nutrition and oxygen to growing tissues. In addition, inflammatory cells require interaction with and transmigration through the endothelial basement membrane to enter the site of injury. Angiogenesis, in response to tissue injury, is a dynamic process that is highly regulated by signals from both serum and the surrounding extracellular matrix environment [

44]. The acute phase response is a systemic reaction to disturbances in homeostasis caused by infection, tissue injury, trauma, or surgery. It is characterized by changes in the concentrations of plasma proteins, collectively known as acute-phase proteins. Exercise, particularly prolonged endurance activities like marathon running, can induce an acute phase response. Studies have shown that serum levels of acute-phase reactants increase following endurance exercise, demonstrating similarities between this response and the response consequent to general medical and surgical conditions [

45].

In summary, angiogenin is a multifunctional protein involved in angiogenesis, wound healing, and tissue repair. Its role as an acute-phase reactant suggests that it may be involved in the body's response to prolonged endurance activities, such as marathon running.

To investigate alterations in AMPs during extraordinary physical activity and their potential role in the development of EIB, we analyzed serum levels of AMPs in runners before, immediately after, and a few days following a marathon or half-marathon. These results were compared with those of healthy sedentary controls. Additionally, spirometric values were assessed to detect the occurrence of EIB. Our aim was to gain a deeper understanding of the systemic secretion of AMPs during physical stress and their potential contribution to EIB.

Material and Methods

Setting

For this study male and female runners of a full or half marathon (Vienna City Marathon, held on April 5th, 2012) were included and assessed at three different timepoints: the day before (further referred to as baseline), immediately after (peak) and two to seven days after the marathon (recovery). The spirometry was performed using a portable lung function testing device (PC Spirometry, SDS 104, Schiller AG, Linz, Austria) to assess FVC%, FEV1%, MEF75, MEF50, MEF25 and the FEV1/FVC ratio at all three timepoints. On this day mean air pressure was 974.8hPA, mean air temperature was 10.8 °C, mean relative air humidity 87.3%, wind direction was northwest, wind force was between 12-19km/h and there was no precipitation. Patients suffering from exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) were defined as a decrease of ≥10% in FEV1 from baseline. None of the participants suffered from COPD, asthma, or any other condition that causes respiratory symptoms during or after physical exercise and also none of the participants showed signs of COPD as defined by the global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) criteria. There were no bronchodilators taken by participants or administered for study purposes.

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (EK 1034/2012) of the Medical University of Vienna. All tests were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines for good scientifc practice of the Medical University Vienna. All subjects participating in this study gave written informed consent.

Laboratory procedures. Blood samples were collected at baseline, peak and recovery. Blood was taken from the antecubital vein in EDTA and serum gel tubes. EDTA tubes were used for blood count analysis using a haematology analyser (Sysmex KX-21N) and for investigations of routine parameters. Serum was separated by centrifugation (15 minutes at RCF 2845×g) and used for quantification of the indicated proteins. All samples were stored at −80 °C within 2hours after the event. The study was conducted at the research laboratories of the Department of Thoracic Surgery at the Medical University Vienna.

Detection of proteins in serum. Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used to measure serum concentrations of the indicated antimicrobial proteins. These ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The employed quantitative immunoassays were purchased as follows: Angiogenin (RnD Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), S100A8/A9 (RnD Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), S100A8 (RnD Systems, USA), Human Defensin Beta 2 (Elabscience, Houston, Texas, USA) and Major Basic Protein (MyBioSource, San Diego, USA). Researchers performing the laboratory work and data analyses were blinded to the study groups associated with each sample.

Statistical methods. Data was analyzed using SPSS software (version 29; IBM SPSS Inc., IL, USA). To compare the means of two or more independent groups with normal distributions, unpaired Student's t-tests and one-way ANOVA were applied, respectively. For non-normal distributions, the Kruskal-Wallis rank test was used. The specific tests used are indicated in the table and/or results section. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni correction. For comparison of repeated measurements in the same study subject paired t-test was used in normally distributed data. For non-normally distributed data the Wilcoxon test was used. Non-normally distributed data is presented as median and interquartile range. Normally distributed data are given as mean with standard error of the mean. To assess linear relationships between two numerical variables, Pearson's product-moment correlation was employed, reported as the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). Figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA)

Results

Demographic and Spirometry Data

In this study the serum and data of 34 marathoners, 36 half-marathoners and 30 sedentary volunteers were collected. The detailed demographic data, spirometry data, running and training history can be found in these previously published studies [

46,

47].

Serum Measurement of Circulating Antimicrobial Peptides

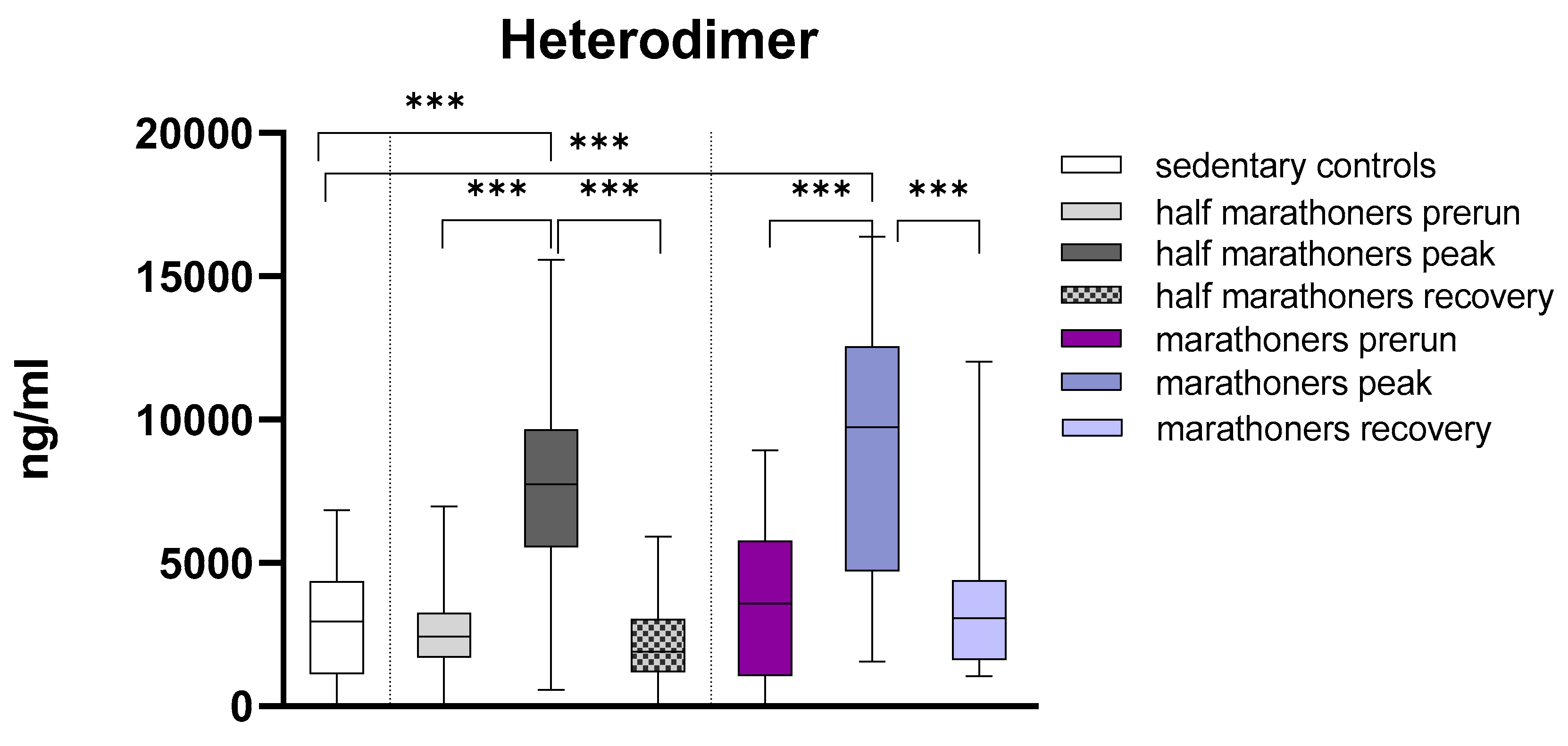

S100A8/S100A9 Heterodimer (Calprotectin)

Calprotectin was significantly elevated in half-marathoners and marathoners reaching the finishing areas (p<0.001) compared to baseline serum values and sedentary controls. After peaking in the finishing area, calprotectin returns to baseline values 7 days after running. There was no significant difference in Calprotectin levels in half-marathoners and marathoners (

Figure 1).

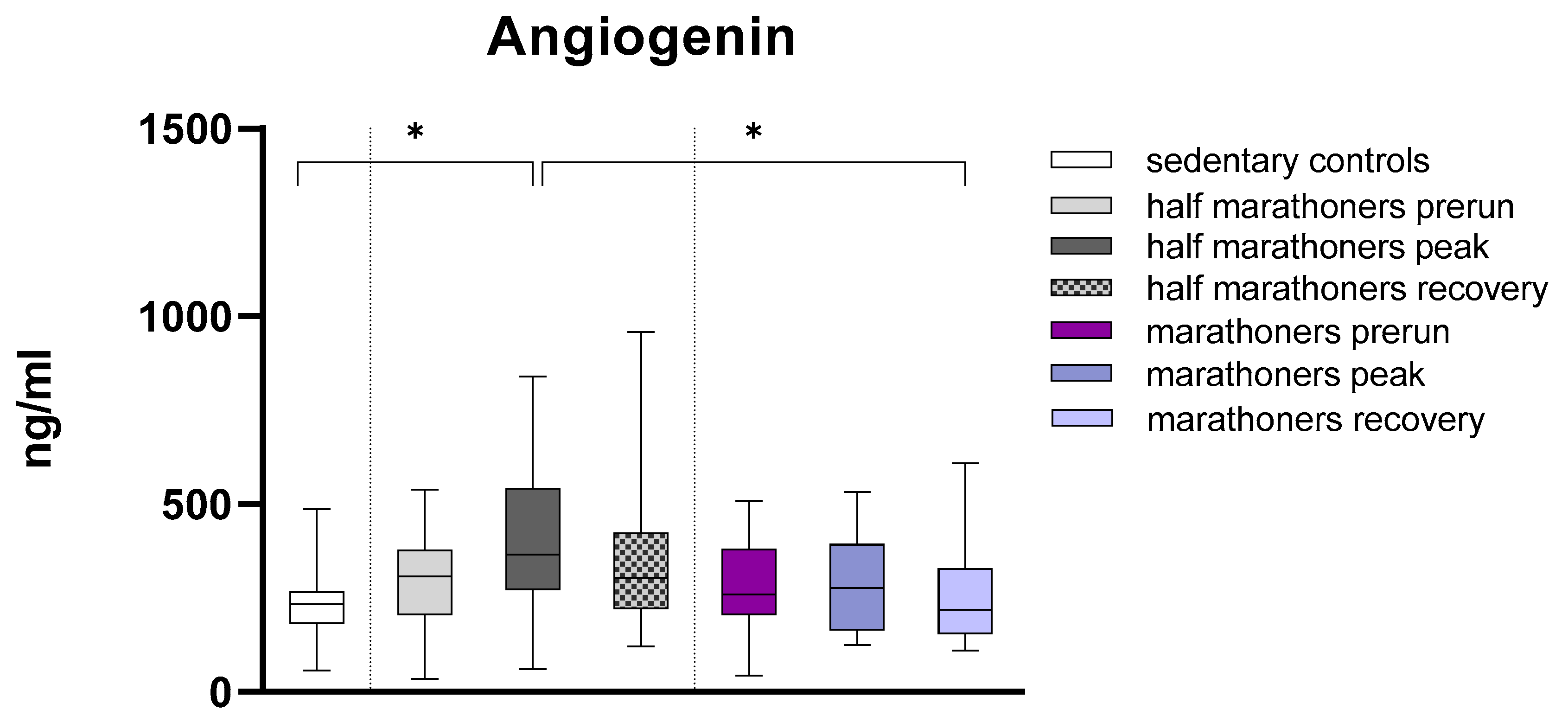

Angiogenin

Angiogenin was significantly elevated in half-marathoners immediately after running (232.6ng/ml) compared to sedentary controls (365.4ng/ml, p=0.038) and marathoners 7 days after running (217.8ng/ml, p=0.028) (

Figure 2). Angiogenin levels in marathoners remained largely unchanged when comparing pre-run, peak, and post-run measurements. In half-marathoners, angiogenin levels showed larger differences when comparing pre-run and post-run measurements with peak measurements, although these differences were not statistically significant. Medians were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests and Bonferroni post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons.

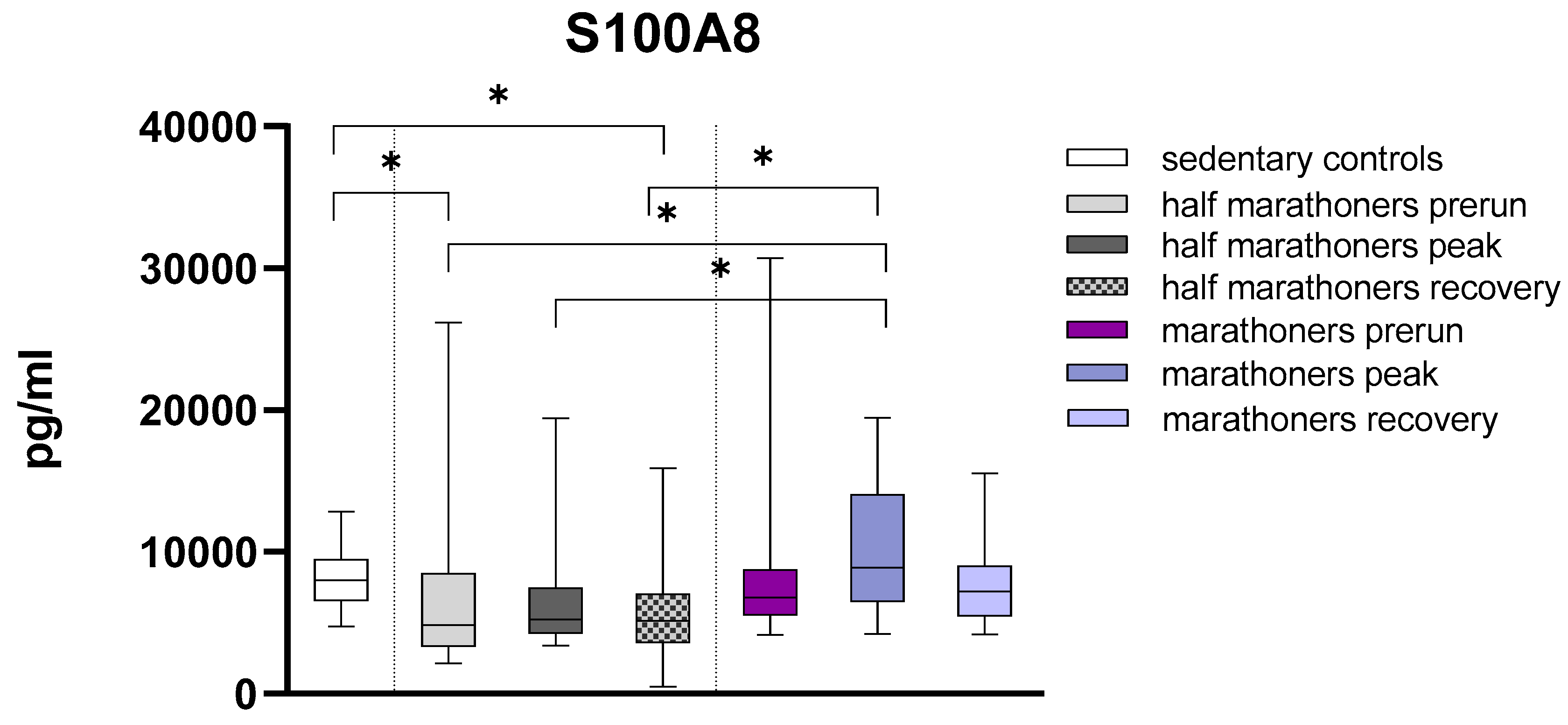

S100A8

S100A8 was significantly reduced in half-marathoners baseline (p=0.028) and half-marathoners recovery serum values (p=0.008) compared to sedentary controls. S100A8 was conversely significantly elevated in marathoners reaching the finishing area compared to all timepoints (all p<0.01) in half-marathoners. Even though not statistically significant marathoners exhibited elevated recovery values compared to half-marathoners (p=0.06) (

Figure 3).

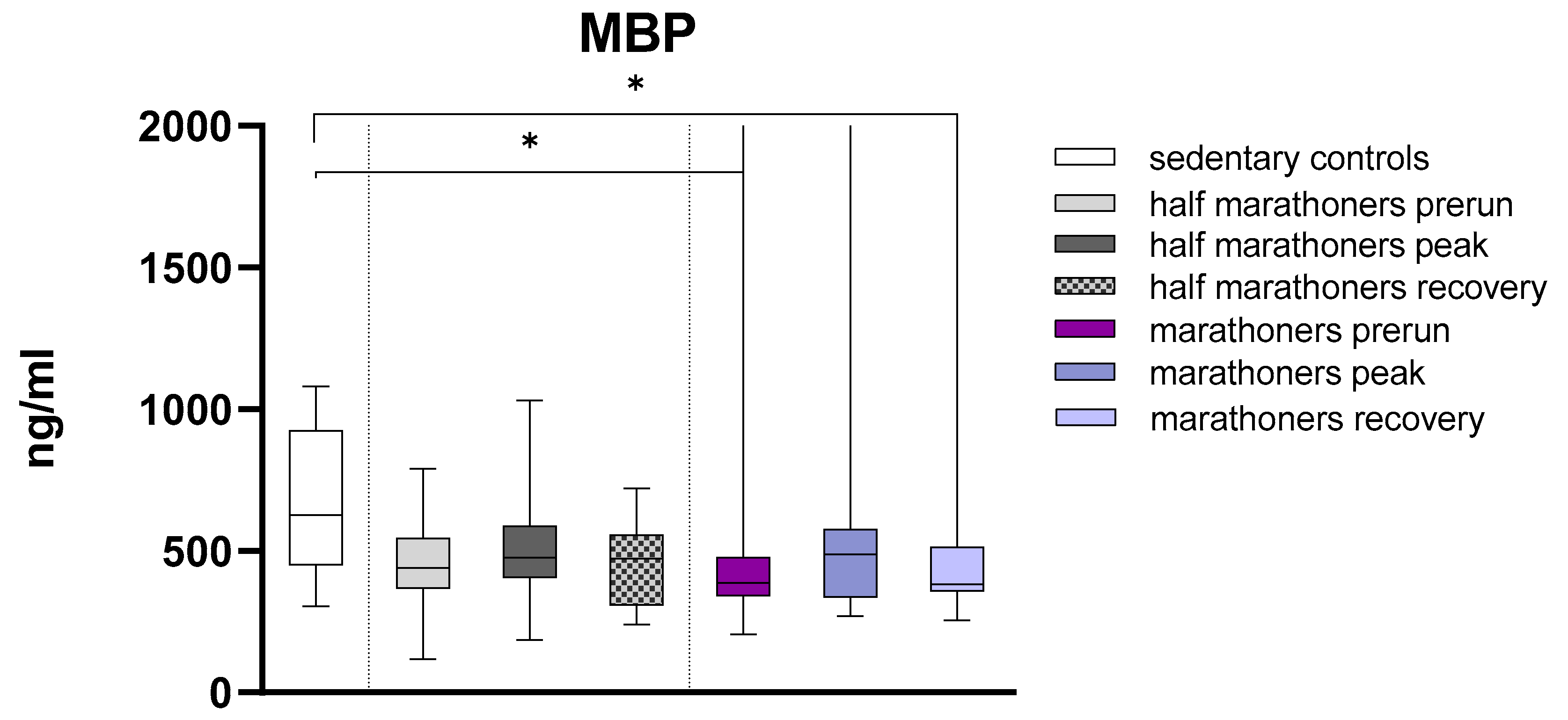

Major Basic Protein

Major Basic Protein was significantly higher in sedentary controls compared to baseline and recovery serum levels of marathoners (627ng/ml, IQR: 450.2-926.0 vs. 388ng/ml, IQR:341.1-477.2 and 382.9, IQR: 357.2-514.3, p= 0.035 and p=0.014) (

Figure 4).

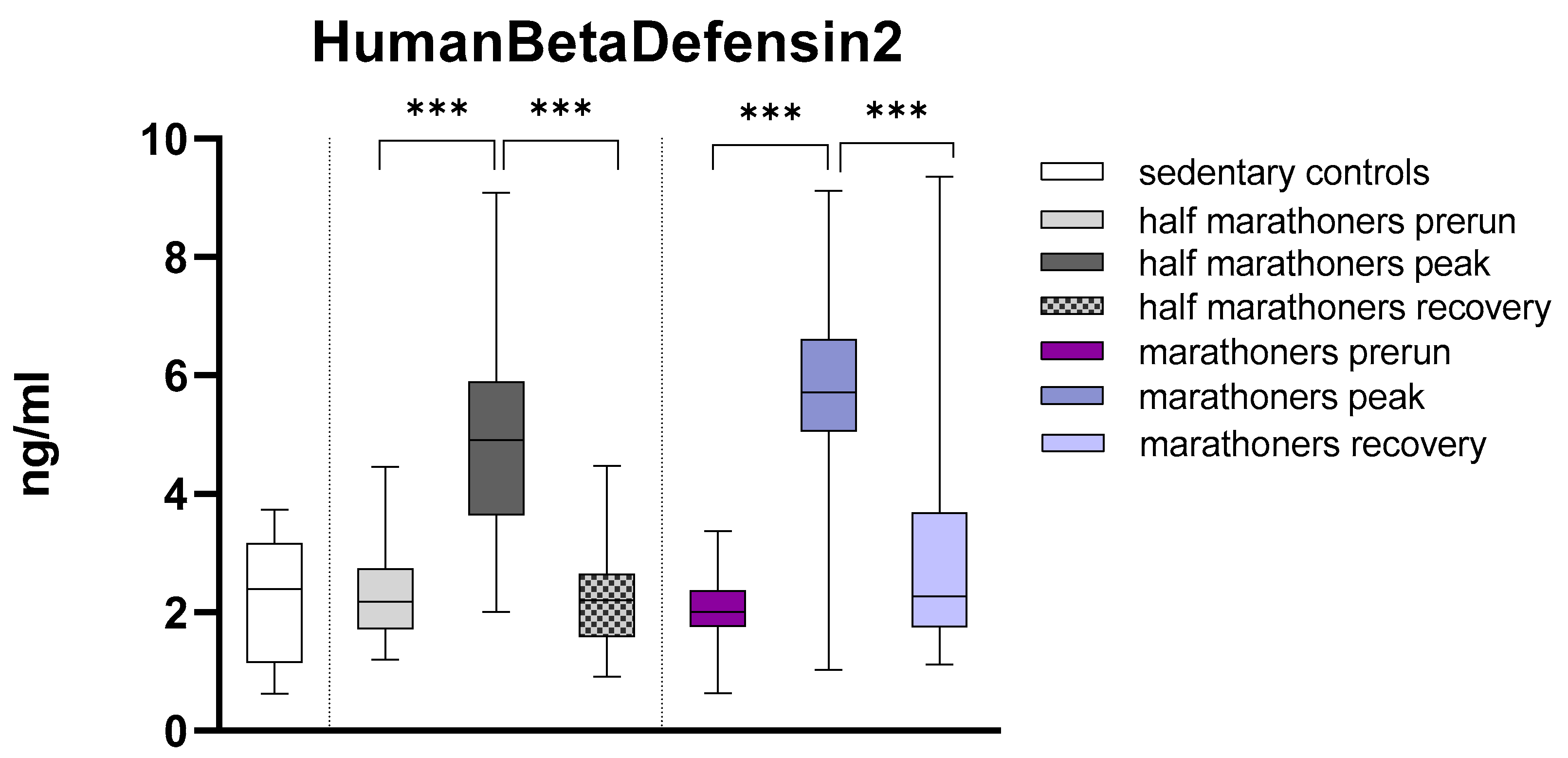

Human Beta Defensin 2

Human Beta Defensin2 was highly significant elevated in half-marathoners (4.91ng, IQR:3.6-5.9) and marathoners (5.7ng, IQR: 5.1-6.6) reaching the finishing area compared to their baseline values (HM: 2.18, IQR: 1.72-2.74 and M: 2.02, IQR: 1.77-2.37) and sedentary controls (

Figure 5). After 2-7 days of recovery the value returned to baseline. The detailed results of Kruskal-Wallis analysis are listed below in

Table 1.

EIB

Two to seven days post-run there were slightly elevated levels of S100A8 (7025.86ng/ml, ±595,31 vs. 9674,48ng/ml, ± 1142,12; p=0.053) in marathoners with EIB. Similarly, there were also slightly elevated levels of HumanBetaDefensin2 (2,25ng/ml, ±0.17 vs. 3.2, ±0.5; p=0.084) in the runners with EIB (HM+M) two to seven days post-run. Immediately after the run in the finishing area there were slightly reduced Angiogenin values in half- and marathoners with EIB (277.86ng/ml, ± 33.73 vs. 370.32ng/ml, ± 25.62, p=0.058).

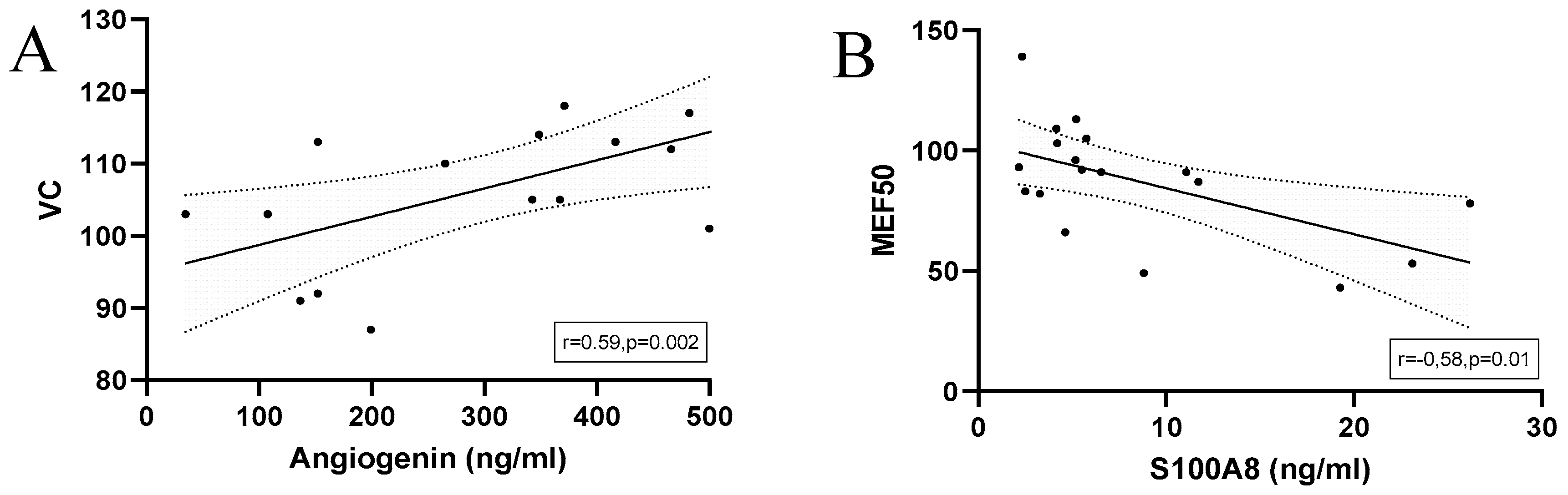

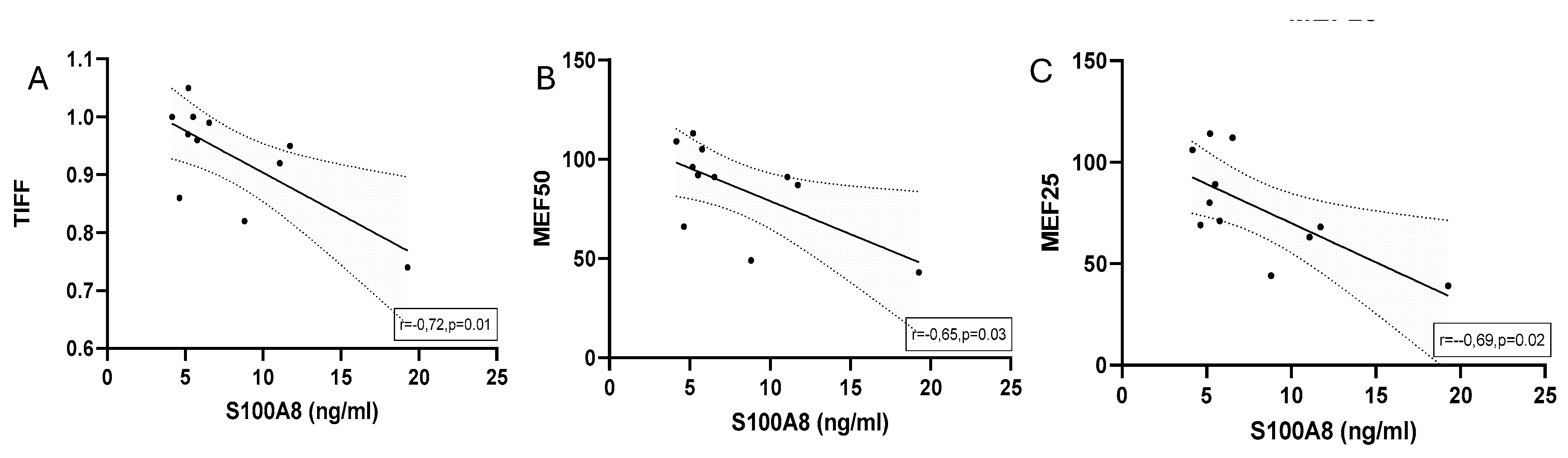

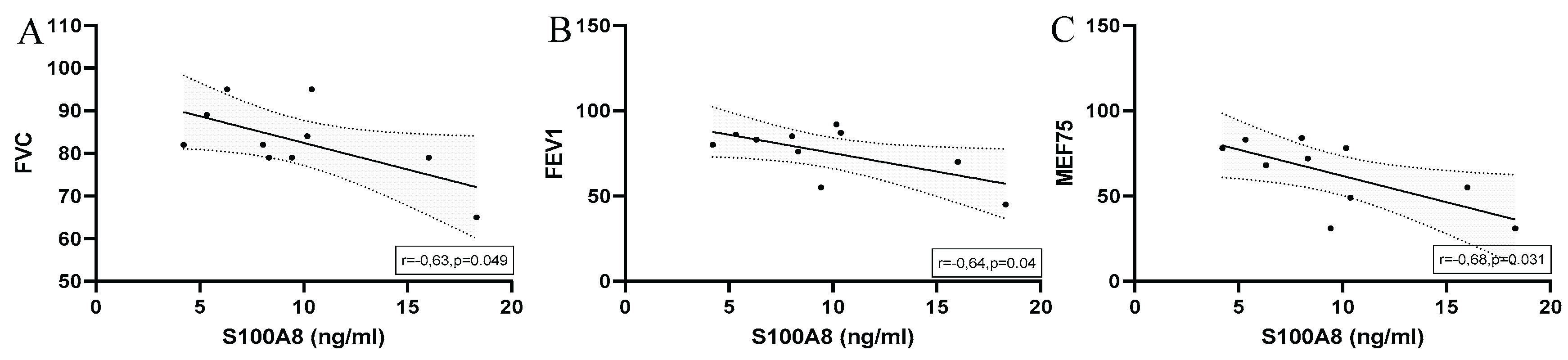

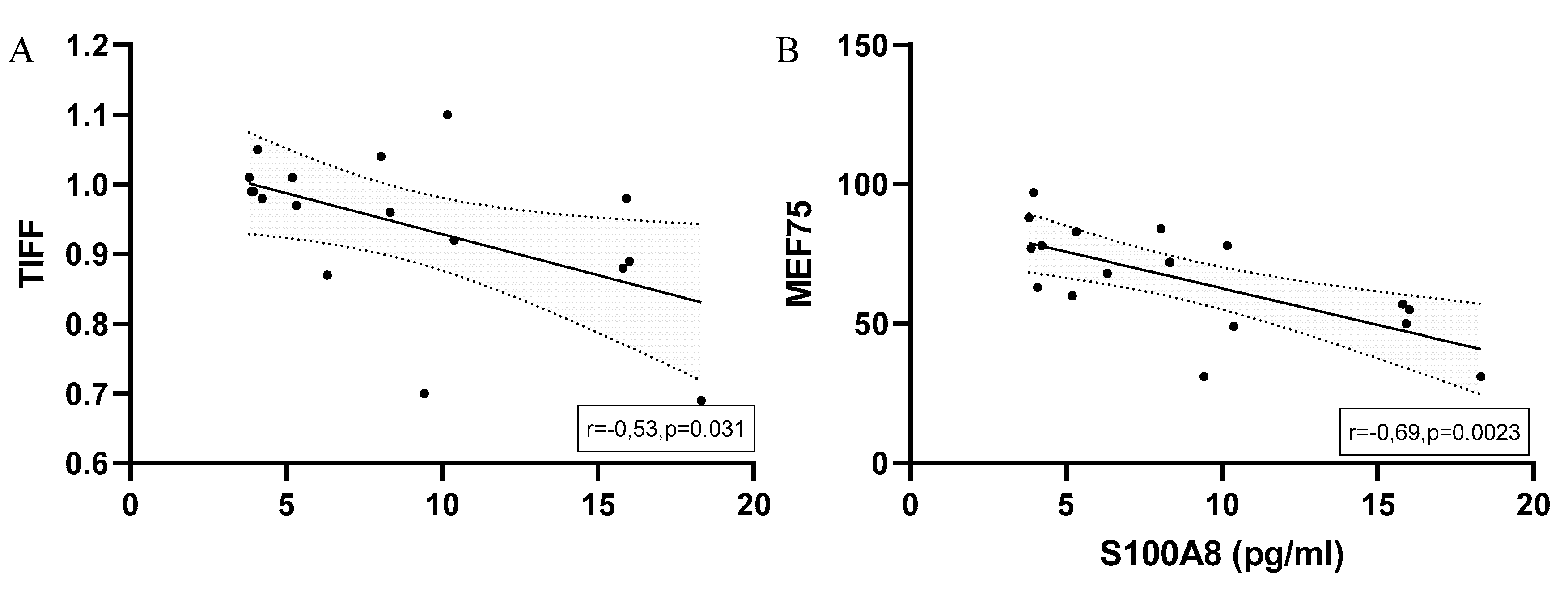

There was a negative correlation between MEF75 and S100A8 in half-marathoners and marathoners (r=-0.7; p=0.002) and TIFF (-0.53; p=0.029). Human Beta Defensin2 was positively correlated with MBP (r=0.59; p=0.02).

In half-marathoners there was a strong correlation between Heterodimer and MBP (r=0,9; p=0.002) and MEF25 (r=0.86; p=0.013). Between MBP and MEF25 there was also a positive correlation (r=0.853, p=0.015).

Significant correlations between calculated antimicrobial peptide levels and spirometry data of marathoners and half-marathoners at baseline are depicted in

Figure 6.

Significant correlations between calculated antimicrobial peptide levels and spirometry data of marathoners at baseline are depicted in

Figure 7.

There were no correlations in the group of half-marathoners between baseline serum levels of antimicrobial peptides and spirometry outcomes.

In marathoners reaching the finishing area and showing signs of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction there was a significant negative correlation of S100A8 serum levels and FVC, FEV1 and MEF75. Graphical illustration with linear regression lines is depicted in

Figure 8.

When considering all runners with EIB at the finishing area there was a significant negative correlation of S100A8 serum levels with TIFF and MEF75. (

Figure 9)

Correlations of Cytokines and Calculated Antimicrobial Peptides in Half-Marathoners and Marathoners with EIB

The following table (

Table 2) summarizes significant correlations between serum levels of cytokines and antimicrobial peptides in marathon and half-marathon runners, assessed at three time points: baseline (1–2 days before the race), peak (immediately post-race), and recovery (2–7 days after the race). Correlation analysis highlighted associations between immune-related markers such as S100A8/A9, ST2, esRAGE, and MBP. A correlation analysis of AMPs with additional laboratory parameters is available in the supplementary data.

Discussion

This study suggests that marathon and half-marathon running substantially modulate immune and inflammatory responses, as evidenced by elevations in antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and related inflammatory markers. Notably, human beta-defensin 2 (hBD-2), a central AMP, was significantly increased in marathon runners immediately after completion of the race, indicating transient immune activation. Elevated levels of hBD-2 may enhance mucosal defenses against pathogens—a critical function during the post-exercise “open window” period, characterized by temporary immunosuppression and heightened infection susceptibility in endurance athletes [

48].Interestingly, hBD-2 has previously been associated with protective airway mechanisms, particularly in the context of asthma and chronic respiratory inflammation [

11,

23]. This supports its potential role in mitigating bronchoconstriction and infection following strenuous physical exertion.

Similarly, S100A8/A9 (calprotectin) showed a pronounced post-run elevation before returning to baseline during recovery. This pattern mirrors its function as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) and a marker of systemic inflammation in both physical stress and chronic inflammatory airway diseases [

27,

49]. In contrast, levels of MBP—a cytotoxic protein released by eosinophils—were higher in sedentary controls compared to athletes, suggesting that regular endurance training may attenuate basal eosinophilic inflammation [

38].

Among runners who developed EIB, significant inverse correlations were observed between S100A8 levels and lung function parameters, suggesting a possible mechanistic role of S100 proteins in EIB-associated airway dysfunction. Moreover, angiogenin, a protein involved in vascular remodeling and known to act as an acute-phase reactant [

40], was positively correlated with lung function values in EIB-positive athletes, yet exhibited reduced serum concentrations post-race in this group. This may reflect a transient vascular and immune dysregulation in the setting of acute bronchoconstrictive stress.

Angiogenin dynamics also varied by race type: half-marathoners displayed significant post-run elevations, whereas levels in marathoners remained comparatively stable across phases. This differential response aligns with evidence suggesting that shorter, high-intensity endurance efforts induce sharper, though transient, inflammatory responses compared to prolonged submaximal activity [

8,

50]. Supporting this, Legaz-Arrese et al. demonstrated that competitive exercise intensity more robustly modulates angiogenic and inflammatory pathways than lower-intensity running [

51].

While much of the existing literature focuses on local AMP responses—especially in salivary or mucosal secretions—during exercise [

13,

52,

53,

54,

55], our study uniquely captures systemic AMP fluctuations and their association with respiratory function and EIB risk. These findings emphasize the value of systemic biomarkers in elucidating the broader immunophysiological consequences of endurance training.

Additionally, by comparing athletes to non-endurance-trained individuals, we observed distinct baseline and post-exercise AMP profiles, which may reflect long-term adaptive immune remodeling in response to habitual physical activity.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although the sample size was sufficient to detect moderate effect sizes, it may constrain the generalizability of the findings to wider athletic populations. All participants were drawn from a single event under specific environmental conditions, limiting extrapolation to different climates or race settings.

Second, the observational study design and time-point-based sampling preclude definitive conclusions regarding causality. Although we observed correlations between AMP concentrations and pulmonary function, longitudinal analyses would be required to determine the predictive or mechanistic role of AMPs in EIB pathogenesis.

Third, while participants with pre-existing respiratory diagnoses were excluded, the possibility of subclinical airway conditions cannot be entirely excluded. Furthermore, the diagnosis of EIB was based solely on a ≥10% decline in FEV1 without confirmatory bronchial provocation testing, potentially introducing misclassification.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide novel insights into the temporal dynamics of systemic AMPs during endurance exercise and their potential role in EIB.

Conclusion

Systemic changes in antimicrobial peptides induced by prolonged endurance exercise offer promising insight into immune and respiratory stress in athletes. Specifically, significant elevations in hBD-2 and S100A8/A9 immediately after running, suggesting that these peptides may serve as early indicators of airway susceptibility and systemic immune activation.

Routine monitoring of AMP levels in endurance athletes may assist in tailoring training loads, optimizing recovery strategies, and mitigating inflammation-associated risks. Such strategies could include personalized exercise programming, nutritional support, and targeted therapies aimed at stabilizing AMP levels, such as anti-inflammatory agents or peptide-based interventions.

Overall, these results contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting the use of AMPs as biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in managing exercise-induced respiratory and immunological challenges in endurance sports.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Correlations of Serum concentrations of antimicrobial peptides with other laboratory parameters in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.-T.L, B.M. and H-J.A.; data curation: M.-T.L.,B.M, C.B and H.J.A.; formal analysis: M.-T.L, H.K., L.A., and H.J.A. funding acquisition: H.J.A.; investigation: M.-T.L, B.M and H.J.A.; supervision: B.M and H.J.A; writing—original draft preparation M.-T.L and H.J.A. ; writing—review and editing: M.-T.L, H.K., L.A.,C.B, B.M, C.G.K, C.A, M.M and H.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Vienna Business Agency (Vienna, Austria; grant ‘APOSEC to clinic’ 2343727) and by the Aposcience AG under group leader H.J.A. M.M. was funded by the Sparkling Science Program of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research (SPA06/055).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 1034/2012) and was conducted adhering to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as in compliance with the “Good Scientific Practice” guidelines by the Medical University of Vienna. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to their inclusion in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hans Peter Haselsteiner and the CRISCAR Familienstiftung for their ongoing support for the Medical University of Vienna/Aposcience AG public–private partnership, aiming to augment basic and translational clinical research in Austria/Europe.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hannes Kühtreiber, Lisa Auer and Hendrik Jan Ankersmit were employed by the company Aposcience AG. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| AGECML |

Advanced Glycation End Products Carboxymethyllysine |

| AMP |

Antimicrobial Peptide |

| ARDS |

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| EIB |

Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FEV1 |

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second |

| FVC |

Forced Vital Capacity |

| HBDF2 / hBD-2 |

Human Beta-Defensin 2 |

| HCT |

Hematocrit |

| HM |

Half-Marathoner(s) |

| HMGB1 |

High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| IL-1RA |

Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist |

| IL-33 |

Interleukin 33 |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| ISS |

Injury Severity Score |

| MBP |

Major Basic Protein |

| MEF25/50/75 |

Maximal Expiratory Flow at 25% / 50% / 75% of FVC |

| MPV |

Mean Platelet Volume |

| MPO |

Myeloperoxidase |

| MXD |

Mixed Cell Percentage |

| NE |

Neutrophil Elastase |

| PDW |

Platelet Distribution Width |

| PLT |

Platelet Count |

| RAGE |

Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products |

| r |

Correlation Coefficient |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| sRAGE |

Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products |

| ST2 |

Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 |

| TIFF |

Tiffeneau Index (FEV1/FVC ratio) |

| WBC |

White Blood Cell Count |

References

- Poirier, P.; Després, J.P. Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiol. Clin. 2001, 19, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buresh, R. Exercise and glucose control. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2014, 54, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marwaha, R.K.; Puri, S.; Tandon, N.; Dhir, S.; Agarwal, N.; Bhadra, K.; Saini, N. Effects of sports training & nutrition on bone mineral density in young Indian healthy females. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thune, I.; Furberg, A.S. Physical activity and cancer risk: dose-response and cancer, all sites and site-specific. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, S530–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, A.; Giardini, G.; Tonacci, A.; Mastorci, F.; Mercuri, A.; Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Moretti, S.; Andreassi, M.G.; Pratali, L. Chronic and acute effects of endurance training on telomere length. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Henson, D.A.; Smith, L.L.; Utter, A.C.; Vinci, D.M.; Davis, J.M.; Kaminsky, D.E.; Shute, M. Cytokine changes after a marathon race. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, E.; Roca, E.; Perea, L.; Rodrigo-Troyano, A.; Suarez-Cuartin, G.; Giner, J.; Feliu, A.; Soria, J.M.; Nescolarde, L.; Vidal, S.; Sibila, O. Salivary immunity and lower respiratory tract infections in non-elite marathon runners. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predel, H.-G. Marathon run: cardiovascular adaptation and cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 3091–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, M.; Schmidtchen, A.; Malmsten, M. Antimicrobial peptides: key components of the innate immune system. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. The antimicrobial peptide database is 20 years old: Recent developments and future directions. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, M.; Bagińska, N.; Górski, A.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E. Human β-Defensin 2 and Its Postulated Role in Modulation of the Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueiros-Cendón, T.; Arévalo-Gallegos, S.; Iglesias-Figueroa, B.F.; García-Montoya, I.A.; Salazar-Martínez, J.; Rascón-Cruz, Q. Immunomodulatory effects of lactoferrin. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, N.P.; Pyne, D.B.; Renshaw, G.; Cripps, A.W. Antimicrobial peptides and proteins, exercise and innate mucosal immunity. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 48, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonna, L.A.; Angel, K.C.; Sharp, M.A.; Knapik, J.J.; Patton, J.F.; Lilly, C.M. The prevalence of exercise-induced bronchospasm among US Army recruits and its effects on physical performance. Chest 2001, 119, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng’ang’a, L.W.; Odhiambo, J.A.; Mungai, M.W.; Gicheha, C.M.; Nderitu, P.; Maingi, B.; Macklem, P.T.; Becklake, M.R. Prevalence of exercise induced bronchospasm in Kenyan school children: an urban-rural comparison. Thorax 1998, 53, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukafka, D.S.; Lang, D.M.; Porter, S.; Rogers, J.; Ciccolella, D.; Polansky, M.; D’Alonzo, G.E. Exercise-induced bronchospasm in high school athletes via a free running test: incidence and epidemiology. Chest 1998, 114, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.D.; Kippelen, P. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: pathogenesis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005, 5, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.D.; Kippelen, P. Airway injury as a mechanism for exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in elite athletes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 225–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.M.; Harder, J. Human beta-defensin-2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999, 31, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.S.; Blaum, B.S.; Vargues, T.; De Cecco, M.; Deakin, J.A.; Lyon, M.; Barran, P.E.; Campopiano, D.J.; Uhrín, D. Interaction of human β-defensin 2 (HBD2) with glycosaminoglycans. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 10486–10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagi, S.; Ashitani, J.; Imai, K.; Kyoraku, Y.; Sano, A.; Matsumoto, N.; Nakazato, M. Significance of human beta-defensins in the epithelial lining fluid of patients with chronic lower respiratory tract infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Sun, B.B.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Li, J.Q.; Wang, H.X.; Zhang, S.F.; Liu, D.S.; Liu, L.; Xu, D.; Ou, X.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Yang, T.; Zhou, H.; Wen, F.Q. Cigarette smoke enhances {beta}-defensin 2 expression in rat airways via nuclear factor-{kappa}B activation. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchers, N.S.; Santos-Valente, E.; Toncheva, A.A.; Wehkamp, J.; Franke, A.; Gaertner, V.D.; Nordkild, P.; Genuneit, J.; Jensen, B.A.H.; Kabesch, M. Human β-Defensin 2 Mutations Are Associated With Asthma and Atopy in Children and Its Application Prevents Atopic Asthma in a Mouse Model. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 636061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia Rosete Olvera, D.; Cabello Gutiérrez, C. Multifunctional Activity of the β-Defensin-2 during Respiratory Infections. In Immune response activation and immunomodulation; K. Tyagi, R., S. Bisen, P., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2019 ISBN 978-1-78985-151-9.

- Liu, S.; He, L.-R.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.-H.; He, Z.-Y. Prognostic value of plasma human β-defensin 2 level on short-term clinical outcomes in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a preliminary study. Respir. Care 2013, 58, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menees, S.B.; Powell, C.; Kurlander, J.; Goel, A.; Chey, W.D. A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with IBS. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, R.; Wang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, J. S100A8/A9 in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Nie, C.; Yao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, H.; Hao, C. S100A8/9 modulates perturbation and glycolysis of macrophages in allergic asthma mice. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Endoh, I.; Hsu, K.; Tedla, N.; Endoh, Y.; Geczy, C.L. S100A8 modulates mast cell function and suppresses eosinophil migration in acute asthma. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.; Busse, W.W. Biomarkers in asthmatic patients: Has their time come to direct treatment? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.-Y.; Gu, Q.; Lin, A.-H.; Khosravi, M.; Gleich, G. Airway hypersensitivity induced by eosinophil granule-derived cationic proteins. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 57, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plager, D.A.; Loegering, D.A.; Weiler, D.A.; Checkel, J.L.; Wagner, J.M.; Clarke, N.J.; Naylor, S.; Page, S.M.; Thomas, L.L.; Akerblom, I.; Cocks, B.; Stuart, S.; Gleich, G.J. A novel and highly divergent homolog of human eosinophil granule major basic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 14464–14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, P.C.; Ackerman, S.J.; Spry, C.J.; Dunnette, S.; Olsen, E.G.; Gleich, G.J. Deposits of eosinophil granule proteins in cardiac tissues of patients with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Lancet 1987, 1, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleich, G.J.; Flavahan, N.A.; Fujisawa, T.; Vanhoutte, P.M. The eosinophil as a mediator of damage to respiratory epithelium: a model for bronchial hyperreactivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1988, 81, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelts, D.; Egan, R.W.; Falcone, A.; Garlisi, C.G.; Gleich, G.J.; Kreutner, W.; Kung, T.T.; Nahrebne, D.K.; Chapman, R.W.; Minnicozzi, M. Eosinophils retain their granule major basic protein in a murine model of allergic pulmonary inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998, 18, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.M.; Fryer, A.D.; Jacoby, D.B.; Gleich, G.J.; Costello, R.W. Pretreatment with antibody to eosinophil major basic protein prevents hyperresponsiveness by protecting neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 100, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundel, R.H.; Letts, L.G.; Gleich, G.J. Human eosinophil major basic protein induces airway constriction and airway hyperresponsiveness in primates. J. Clin. Invest. 1991, 87, 1470–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore, M.R.; Morici, G.; Riccobono, L.; Insalaco, G.; Bonanno, A.; Profita, M.; Paternò, A.; Vassalle, C.; Mirabella, A.; Vignola, A.M. Airway inflammation in nonasthmatic amateur runners. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001, 281, L668–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Gao, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, M.; Xu, Z. Alpha-actinin-2, a cytoskeletal protein, binds to angiogenin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 329, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello-Montoliu, A.; Patel, J.V.; Lip, G.Y.H. Angiogenin: a review of the pathophysiology and potential clinical applications. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 1864–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fett, J.W.; Strydom, D.J.; Lobb, R.R.; Alderman, E.M.; Bethune, J.L.; Riordan, J.F.; Vallee, B.L. Isolation and characterization of angiogenin, an angiogenic protein from human carcinoma cells. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 5480–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, D.J. The angiogenins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1998, 54, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.A.; Verselis, S.J.; Fett, J.W. Angiogenin is regulated in vivo as an acute phase protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 242, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Kirsner, R.S. Angiogenesis in wound repair: angiogenic growth factors and the extracellular matrix. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2003, 60, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, K.E. The acute phase response and exercise: the ultramarathon as prototype exercise. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2001, 11, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekos, C.; Zimmermann, M.; Unger, L.; Janik, S.; Hacker, P.; Mitterbauer, A.; Koller, M.; Fritz, R.; Gäbler, C.; Kessler, M.; Nickl, S.; Didcock, J.; Altmann, P.; Haider, T.; Roth, G.; Klepetko, W.; Ankersmit, H.J.; Moser, B. Non-professional marathon running: RAGE axis and ST2 family changes in relation to open-window effect, inflammation and renal function. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekos, C.; Zimmermann, M.; Unger, L.; Janik, S.; Mitterbauer, A.; Koller, M.; Fritz, R.; Gäbler, C.; Didcock, J.; Kliman, J.; Klepetko, W.; Ankersmit, H.J.; Moser, B. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, temperature regulation and the role of heat shock proteins in non-asthmatic recreational marathon and half-marathon runners. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Wentz, L.M. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooren, F.C.; Lechtermann, A.; Fobker, M.; Brandt, B.; Sorg, C.; Völker, K.; Nacken, W. The response of the novel pro-inflammatory molecules S100A8/A9 to exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2006, 27, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, M.; Krzemiński, K.; Buraczewska, M.; Kozacz, A.; Dąbrowski, J.; Ziemba, A.W. Effect of mountain ultra-marathon running on plasma angiopoietin-like protein 4 and lipid profile in healthy trained men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaz-Arrese, A.; George, K.; Carranza-García, L.E.; Munguía-Izquierdo, D.; Moros-García, T.; Serrano-Ostáriz, E. The impact of exercise intensity on the release of cardiac biomarkers in marathon runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2961–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillum, T.L.; Kuennen, M.; Gourley, C.; Schneider, S.; Dokladny, K.; Moseley, P. Salivary antimicrobial protein response to prolonged running. Biol. Sport 2013, 30, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Orita, K.; Ueda, S.-Y.; Katsura, Y.; Fujimoto, S.; Yoshimura, M. Changes in salivary antimicrobial peptides, immunoglobulin A and cortisol after prolonged strenuous exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Hanaoka, Y.; Akama, T.; Kono, I. Ageing and free-living daily physical activity effects on salivary beta-defensin 2 secretion. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, R.; Uchino, T.; Uchida, M.; Fujie, S.; Iemitsu, K.; Kojima, C.; Nakamura, M.; Shimizu, K.; Tanimura, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Isaka, T.; Iemitsu, M. Acute salivary antimicrobial peptide secretion response to different exercise intensities and durations. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Serum concentrations of S100A8/S100A9 (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

Figure 1.

Serum concentrations of S100A8/S100A9 (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

Figure 2.

Serum concentrations of Angiogenin (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 2.

Serum concentrations of Angiogenin (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 3.

Serum concentrations of S100A8 (pg/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 3.

Serum concentrations of S100A8 (pg/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Serum concentrations of Major Basic Protein (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Serum concentrations of Major Basic Protein (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05.

Figure 5.

Serum concentrations of HumanBetaDefensin2 (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 5.

Serum concentrations of HumanBetaDefensin2 (ng/ml) in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 6.

Correlations with regression line of baseline serum concentrations of (A) Angiogenin and (B) S100A8 and spirometry results in marathoners and half-marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; baseline, 1-2 days before the run.

Figure 6.

Correlations with regression line of baseline serum concentrations of (A) Angiogenin and (B) S100A8 and spirometry results in marathoners and half-marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; baseline, 1-2 days before the run.

Figure 7.

Significant correlations with regression line of baseline serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) TIFF (B) MEF50 and (C) MEF25 in marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; TIFF, Tiffeneau-Pinelli index; MEF50, maximal expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity; MEF25, maximal expiratory flow at 25% of forced vital capacity.

Figure 7.

Significant correlations with regression line of baseline serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) TIFF (B) MEF50 and (C) MEF25 in marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; TIFF, Tiffeneau-Pinelli index; MEF50, maximal expiratory flow at 50% of forced vital capacity; MEF25, maximal expiratory flow at 25% of forced vital capacity.

Figure 8.

Significant correlations with regression line of peak serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) FVC (B) FEV1 and (C) MEF75 in marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; peak, immediately after the run; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MEF75, maximal expiratory flow at 75% of FVC.

Figure 8.

Significant correlations with regression line of peak serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) FVC (B) FEV1 and (C) MEF75 in marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; peak, immediately after the run; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MEF75, maximal expiratory flow at 75% of FVC.

Figure 9.

Significant correlations with regression line of peak serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) TIFF (B) MEF75 in marathoners and half-marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; peak, immediately after the run; TIFF, Tiffeneau-Pinelli index ; MEF75, maximal expiratory flow at 75% of FVC.

Figure 9.

Significant correlations with regression line of peak serum concentrations of S100A8 and (A) TIFF (B) MEF75 in marathoners and half-marathoners. Correlations were calculated using Pearson-Correlation; peak, immediately after the run; TIFF, Tiffeneau-Pinelli index ; MEF75, maximal expiratory flow at 75% of FVC.

Table 1.

Serum concentrations of antimicrobial peptides in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Data is given with median and interquartile range, Values were compared using Kruskal-Wallis with Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing; HM, half-marathoners; M, marathoners; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery.

Table 1.

Serum concentrations of antimicrobial peptides in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery and sedentary controls. Data is given with median and interquartile range, Values were compared using Kruskal-Wallis with Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing; HM, half-marathoners; M, marathoners; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery.

| |

Sedentary controls |

HM baseline |

HM peak |

HM recovery |

M baseline |

Mpeak

|

M recovery |

p-value |

| Angiogenin (ng/ml) |

233 (182-267) |

306 (204-379) |

365 (272-542) |

303 (221-424) |

260 (204-381) |

277 (164-393) |

218 (155-328) |

0.015 |

| S100A8/A9 (ng/ml) |

2958 (1121-4360) |

2431 (1710-3255) |

7746 (5561-9659) |

3042 (1196-3042) |

3579 (1052-5781) |

9750 (4719-12558) |

9750 (4719-12558) |

<0.001 |

| S100A8 (pg/ml) |

8016 (6558-9492) |

4848 (3314-8478) |

5247 (4235-7489) |

5161 (3594-7036) |

6796 (5504-8751) |

8886 (6475-14038) |

7230 (5488-9029) |

<0.001 |

| Major Basic Protein (ng/ml) |

627 (450-926) |

440 (368-547) |

476 (405-589) |

472 (307-558) |

388 (341-477) |

488 (335-578) |

383 (357-514) |

0.022 |

| HumanBetaDefensin2 (ng/ml) |

2.38 (1.15-3.16) |

2.18 (1.72-2.74) |

4.91(3.64-5.89) |

2.21 (1.60-2.64) |

2.02 (1.77-2.37) |

5.72 (5.10-6.61) |

2.27 (1.75-3.69) |

<0.001 |

Table 2.

Correlations of Serum concentrations of antimicrobial peptides with cytokines in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery. Data is given with Correlation Coefficient (R), Values were correlated using Pearson correlation coefficient; HM, half-marathoners; M, marathoners; CRP; C-reactive peptide; esRAGE, endogenous secreted receptor for advanced glycation end-products; MBP, major basic protein; AGECML, Advanced glycation endproducts-carboxymethyllysine, HBDF2, human beta-defensin 2; ST2, suppression of tumorigenicity 2; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery.

Table 2.

Correlations of Serum concentrations of antimicrobial peptides with cytokines in marathoners, half-marathoners at baseline, peak and recovery. Data is given with Correlation Coefficient (R), Values were correlated using Pearson correlation coefficient; HM, half-marathoners; M, marathoners; CRP; C-reactive peptide; esRAGE, endogenous secreted receptor for advanced glycation end-products; MBP, major basic protein; AGECML, Advanced glycation endproducts-carboxymethyllysine, HBDF2, human beta-defensin 2; ST2, suppression of tumorigenicity 2; baseline, 1-2 days before the run; peak, immediately after the run in the finishing area; recovery, after 2-7 days after recovery.

| GROUP |

SUBGROUP |

VARIABLES CORRELATED |

CORRELATION COEFFICIENT (R) |

P-VALUE |

| BASELINE |

HM |

ST2 ↔ Angiogenin |

0.70 |

0.002 |

| BASELINE |

M |

ST2 ↔ Angiogenin |

0.84 |

0.004 |

| BASELINE |

HM |

S100A8 ↔ esRAGE |

0.89 |

0.007 |

| BASELINE |

M |

MBP ↔ esRAGE |

0.95 |

<0.001 |

| BASELINE |

M |

S100A8 ↔ CRP |

0.68 |

0.02 |

| PEAK |

HM |

S100A8/A9 ↔ MBP |

0.90 |

0.006 |

| PEAK |

M |

S100A8/A9 ↔ IL33 |

0.79 |

0.01 |

| PEAK |

M |

S100A8 ↔ AGECML |

-0.64 |

0.05 |

| RECOVERY |

HM |

Angiogenin ↔ HBDF2 |

0.84 |

0.02 |

| RECOVERY |

M |

MBP ↔ esRAGE |

0.84 |

0.003 |

| RECOVERY |

HM |

Angiogenin ↔ HBDF2 |

0.85 |

0.032 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).