1. Introduction

Studies have demonstrated exercise of low-to-moderate intensity has been shown to positively influence the immune system by reducing inflammatory responses. These mechanisms are mediated by the enhanced production of anti-inflammatory interleukins such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-13 (IL-13), and interleukin-5 (IL-5) [

1]. However, high-intensity exercise or competitive events elicit a pro-inflammatory response, leading to stress-induced immunosuppression that persists over time. This response is associated with tissue damage, including microtraumas and an elevated production of free radicals due to increased oxygen consumption. In this state, the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 (which has both anti- and pro-inflammatory properties), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is heightened. Consequently, the intensity of the local inflammatory response is proportional to the extent of muscle damage [

2,

3]. Excessive training loads that induce muscle injury can significantly elevate inflammation, potentially resulting in systemic effects. Such systemic inflammation responses, often part of the acute phase reaction to exercise-related stress, may become intense and prolonged, compromising the athlete's immune function and exacerbating immunosuppression. These conditions enhance susceptibility to infections, impair performance and represent significant health risks to athletes [

4].

To our knowledge, there are few studies aimed to analyze the cytokine dynamics during a racket sport competition. In this regard, a study involving young tennis players revealed that during competitive periods, the acute anti-inflammatory immune response was negatively affected, reflected in TNF-α and 1L-ß decreases. However, this response was inverted after three days of rest, during which IL-6 and IL-10 levels augmented [

5]. Similarly, Kozlowska et al. [

6] investigated the immune response of 38 professional male tennis players across three age categories (cadet, junior and senior) during the competitive season. Their findings indicated increased IL-6 and IL-10 levels (moderate to very large effect sizes) in all groups at mid-season and post-season. TNF-α levels were unclear at mid-season but remained elevated (small effect size) in cadets and seniors post-season.

Another study involving 13 young male badminton players reported significant increases in IL-1α and IL-10 levels at the end of the season compared to pre-season [

7]. Given that badminton is an aerobic sport characterized by intermittent efforts at moderate intensity [

8], it may be associated with an anti-inflammatory response.

In comparison, padel is a dynamic doubles racket sport that involves short bursts of high-intensity actions (lasting 0.7–1.5 s), combined with longer periods of low-intensity effort (9–15 s) during rallies. These efforts are interspersed with structured recovery intervals, including 20 s rests between points and 90 s breaks between games. This specific activity profile classifies padel as a moderate-intensity sport, with mean heart rate (HR

mean) values averaging around 72–82% of maximum heart rate (HR

max) in male [

9,

10] and 76–77% HR

max female players [

8,

9]. Thus, padel, as a moderate-intensity exercise, could enhance immune function, reinforce antioxidative capacity, and reduce oxidative stress, potentially lowering the incidence of inflammation-related diseases [

11].

However, research on the inflammatory response in padel players remains limited. Pradas et al. [

9] analyzed, among other non-immune-related biomarkers, the response of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a multifunctional cytokine related to stem cell renewal and immune modulation, in trained male and female padel players during a competitive match. Their findings revealed no significant increase in LIF release in both male and female players.

Existing studies on padel have predominantly focused on topics such as match analysis, training, injury epidemiology, biomechanical assessments, and physiological and physical performance [

12]. A recent systematic review evaluated physiological, physical and anthropometric parameters in padel, highlighting potential differences between female and male players. For example, amateur male players demonstrated lower HR

max compared to semi-professional and professional players, whereas female players maintained consistent HR

max values across skill levels. Regarding maximal oxygen consumption (VO

2max), padel involves effort levels ranging from 76.3% to 95.1% of VO

2max during maximal in-game efforts. Additionally, sex-based differences have been identified in biochemical and haematological biomarkers [

13].

Being a doubles racket sport, each player occupies a specific side of the court (right or left) and alternating actions with their partner [

14]. Previous studies have revealed different physiological demands depending on the playing side. For instance, Carbonell-Martínez et al. [

15] observed that right-side amateur female players exhibited higher HR

max.

Given the increasing popularity of competitive padel, this study aims to analyze the acute inflammatory response during a competitive match, with a specific focus on potential differences based on court side and sex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 21 professional padel players (10 males and 11 females) voluntarily participated in this study. The participants were all active competitors on the World Padel Tour, with at least five years of professional experience, ensuring a high level of expertise and familiarity with competitive demands. They were young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 years (27.7±6.3 years), a range chosen to focus on athletes in their physical prime. Female players were tested during the early-to-mid follicular phase of their menstrual cycle to minimize the potential influence of hormonal variations on performance and physiological responses.

Participants were excluded if they had injuries or medical conditions that could compromise their performance or interfere with study outcomes. Additionally, those using medications or substances known to affect physiological parameters were not eligible. Detailed characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

The purpose of the study was explained verbally to all participants, and informed consent was obtained prior to their inclusion. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [

16], and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Health than Consumption of the Government of Aragón, Spain (approval code: 21/2012; December 19, 2012).

2.2. Experimental Approach

The players were evaluated in two testing sessions, conducted 7 to 9 days apart, between 9:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. Prior to each session, participants were instructed to avoid strenuous physical activity for at least 24 hours and to adhere to an overnight fasting protocol. Additionally, they were required to abstain from caffeine and alcohol for 12 hours before testing. However, players were permitted to hydrate freely during the competition using bottled mineral water.

2.2.1. First Session

Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis (TANITA BC–418MA, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). VO2max and HRmax were measured through an incremental running test performed on a treadmill (Pulsar HP Cosmos, Nussdorf, Germany) equipped with a gas analyzer (Oxycon Pro, Jaegger, Germany) and a heart rate monitor (Cosmos, Nussdorf, Germany).

Following a 5-min warm-up at a brisk walking pace (6 km·h

-1), the treadmill speed was initially set at 8 km·h

-1 and increased by 1 km·h

-1 every minute until the participant reached volitional exhaustion. The treadmill slope was maintained at 1% throughout the test. VO

2max was determined according to ACSM criteria [

17], while HR

max was recorded as the highest heart rate achieved during the test.

2.2.2. Second Session

The second session consisted of a simulated padel competition conducted accordance with the rules of the International Padel Federation. Participants were paired based on sex and performance level. Matches were played in a best-of-three sets format; with a tie-break implemented in the event of a 6-6 game score. Prior to each match, players completed a standardized 15 min warm-up. During the competition, players’ heart rates (HR) were continuously recorded at 5 s intervals (Polar Team System, Kempele, Finland). The event took place on outdoor courts under e environmental condition of 24.1±7.1°C and 45.7±7.3% relative humidity.

2.3. Blood Sampling

During the second session, two blood samples of 10 mL each (collected pre- and post-padel competition) were drawn from the antecubital vein of each participant. Each sample contained 35 μmol of EDTA 2K+ and 1500 IU of the kallikrein inactivator. The samples were refrigerated until centrifugation, which was performed at 2150 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Plasma aliquots were then separated and stored at -80°C. Interleukin levels were analyzed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the multiplex method, employing the Invitrogen™ Human Cytokine 10-Plex Panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and read on a Luminex™ platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis were conducted using the statistical software IBM® SPSS® Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) version 30.0 for Windows operating systems. The quantitative variables were described by means of the mean (Mean) and standard deviation (SD) in order to describe their central distribution and variability. The normality of the distributions of the quantitative variables was checked by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. Parametric analyses were conducted using two-way ANOVA, with side-game and sex as the between-subjects factors, to assess intragroup and intergroup differences across pre- and post-padel competition time points. For non-parametric analyses, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences between groups where the assumptions for parametric tests were not met.

In order to consider the observed differences statistically significant, a significance level p=0.05 was adopted. In addition to statistical significance, the effect size (ES) of the observed differences was assessed, using Cohen's d as an index, with the following interpretations: trivial (d<0.19), small (d=0.20), medium (d=0.50) and large (d=0.80).

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics and Cardiorespiratory Fitness

As it is shown in

Table 1, body composition variables and VO

2max exhibited significant sex-related differences (

p<0.05). In contrast, age and HR

max did not show significant differences.

Laboratory tests revealed that female players on the right side (FRS) had a VO2max of 46.2±4.7 mL·kg-1·min-1, while those on the left side (FLS) exhibited a slightly higher value (48.9±5.1 mL·kg-1·min-1), with no significant difference between the groups (p>0.05). Conversely, male players on the right side (MRS) exhibited a higher VO2max of 61±6.2 mL·kg-1·min-1 compared to male players on the left side (MLS), who reached 55.2±4.4 mL·kg-1·min-1, though the difference was not statistically significant (p>0.05). When all groups were analyzed together, the total VO2max value was 52.2±7.2 mL·kg-1·min-1, with a significant intergroup difference (p<0.05). Regarding HRmax, FRS attained 182.7±8 bpm, while FLS had 190.6±5.4 bpm (p>0.05). Similarly, MRS had an HRmax of 186.5±8.5 bpm, while MLS showed slightly higher values (189.5±12.5 bpm, p>0.05). The total HRmax for all players was 187.2±9.1 bpm, with no significant difference across groups (p>0.05).

3.2. Physiological Demands of the Simulated Competition

Female players averaged 149±16 bpm, (80.1% HRmax in the lab), which was almost identical to the HRmean achieved by male players (148.9±15.8 bpm; 79.1% HRmax in the lab). HRmax values were consistent across groups, with female players reaching 171.8±15.3 bpm (92.2% HRmax in the lab) and male players 175.9±14.5 bpm (93.46% HRmax in the lab). No statistical differences were found between sexes (p>0.05) with ES values close to zero (HRmean: -0.006; HRmax: 0.27), indicating minimal differences between groups.

3.3. Analysis of Inflammatory Responses

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 shows biochemical parameters measured including pro-inflammatory (IL-1ß, IL-2, IL-5, Il-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-12, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13) for female, male and total sample, respectively. Notably, IL-6 exhibits both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects.

Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the biochemical parameters measured before and after a padel match, including pro-inflammatory (IL-1ß, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-12, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13). Notably, IL-6 exhibits both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects.

No significant changes were observed in female players (

Table 2) as all cytokine p-values exceeded the significance threshold (

p>0.05).

In contrast, male players (

Table 3) exhibited significant intragroup differences in three cytokines. IL-7 significantly decreased after the match (

p=0.03, ES=0.67), whereas IL-8 (

p≤0.00, ES=0.82) and IL-10 (

p=0.01, ES=0.80) significantly increased.

When analyzing the total sample (

Table 4), significant changes were also observed in IL-7 (

p=0.02), IL-8 (

p≤0.00), and IL-10 (

p=0.00), reinforcing the trends seen in male players. Additionally, significant sex-based differences were found for IL-8 (

p=0.01), suggesting a differential immune response between male and female players.

These findings indicate that competitive padel matches may influence specific cytokine responses in male players, particularly those involved in inflammatory and immune regulation. However, no significant changes were detected in female players, highlighting potential.

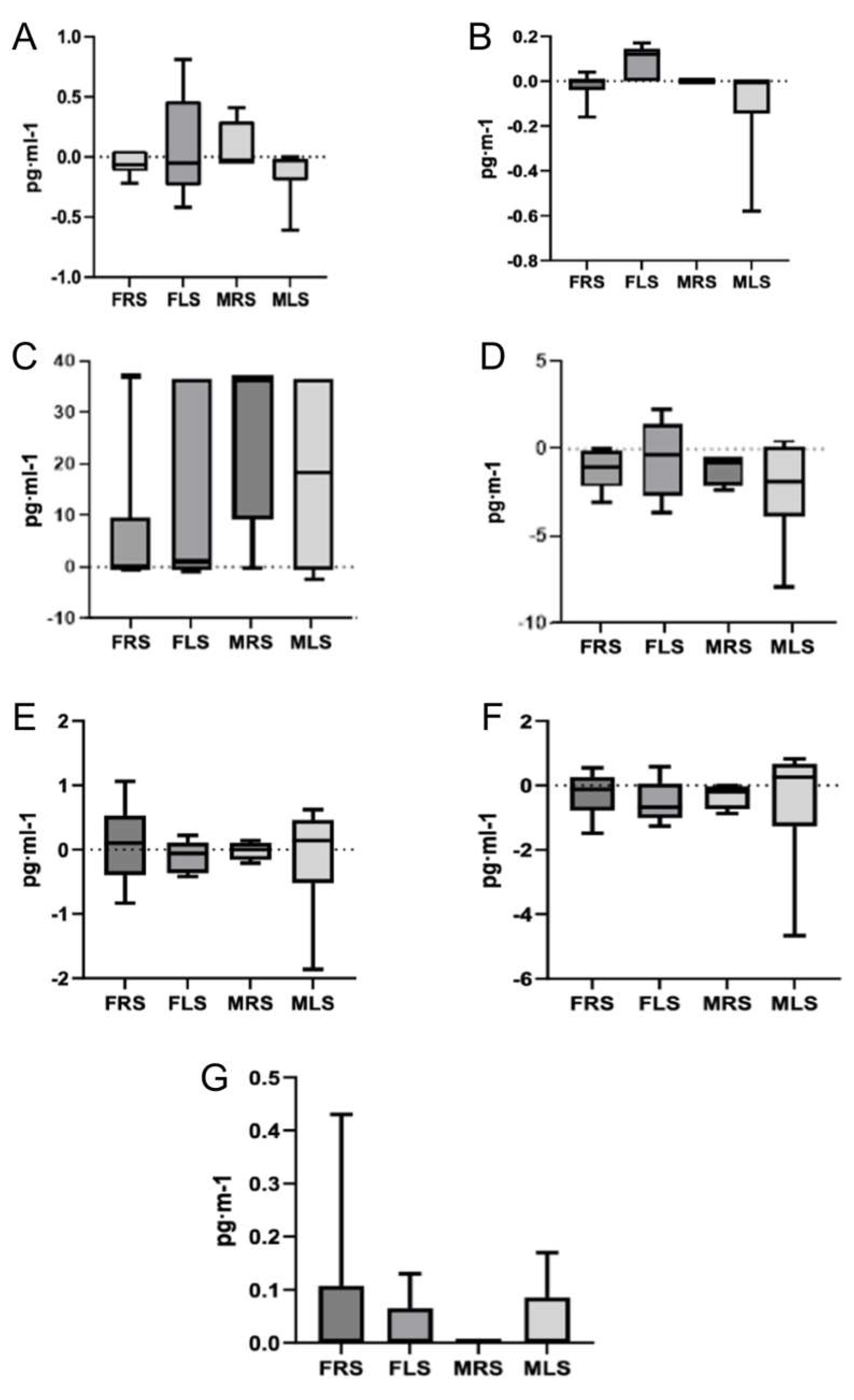

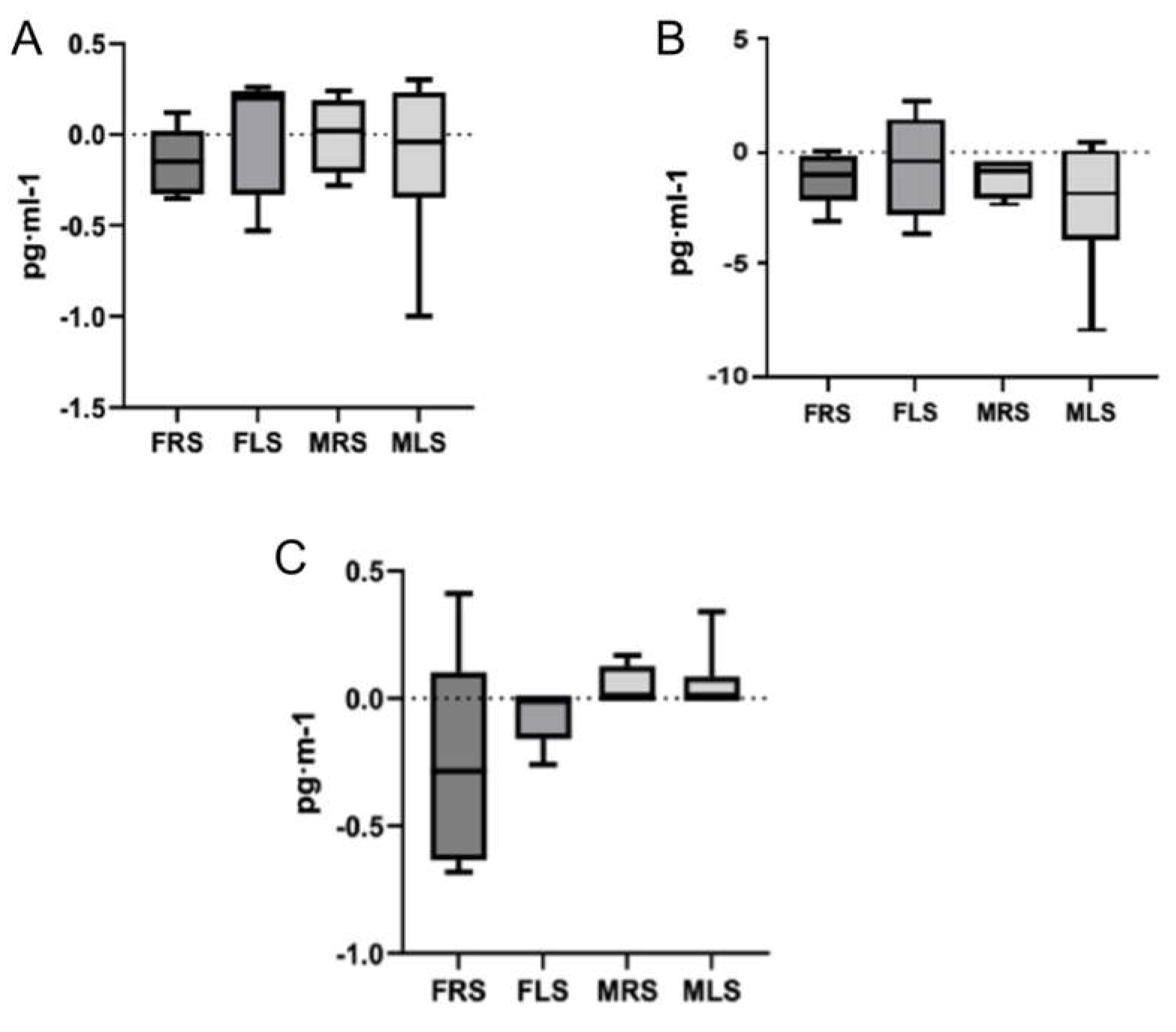

3.4. Analysis According to Playing Side on the Court

To analyze multiple comparisons, a variable was calculated based on the mean differences between pre and post-test values of each interleukin, categorized by sex and playing side on the court: FRS, FLS, MRS and MLS. The Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric) was applied for this analysis. No significant differences were observed between sexes or playing side on the court (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The aim of this is study was to analyze the acute anti- and pro-inflammatory response during a competitive padel match, focusing on differences based on the side of play on the court and sex. Our results, based on intergroup comparisons, showed an increase of IL-10, along with a moderate rise in IL-8 and a decrease in IL-7. Considering that IL-8 and TNF-α are among the most relevant pro-inflammatory interleukins, no significant increase in TNF-α levels was observed between groups. The increase in IL-8 may reflect the specific demands of competitive padel matches, as intense and prolonged exercise is known to induce immune system alterations linked to muscle tissue activity [

4,

18]. Furthermore, a significative increase in IL-10 suggests a potential suppression of TNF-α and IL-7 concentrations, given IL-10’s potent role as an inhibitor of pro-inflammatory cytokines and its ability to suppress cytokine synthesis [

19].

This anti-inflammatory profile appears to be closely linked to the specific characteristics of padel as a sport. Padel’s intermittent activity, characterized by short bursts of high-intensity actions (0.7-1.5 s) and low-intensity efforts (9-15 s) during rallies, interspersed with 20 s rest periods and longer 90 s breaks, likely contributes to this response [

20,

21,

22,

23]. These activity patterns categorize padel as a low- to moderate-impact sport [

8,

9,

10]. Moderate intensity exercise, as observed in padel, is known to enhance immune function, reinforce antioxidative capacity, reduce oxidative stress, and improve energy efficiency, thereby lowering the incidence of inflammatory diseases [

11].

Findings from other racket sports align with our results. For instance, Kozłowska et al. [

6], who analyzed the effects of tennis match on 3 groups of high-ranking male players. In the senior group (>18 years), moderate increases in IL-10 and TNF-α were observed, although no significant differences were reported. Similarly, Witek et al. [

24] evaluated the influence of tournament workload on IL-6 and irisin in elite young tennis players, considering both singles and doubles matches. Their findings revealed a small effect size for IL-10 increases following seasonal changes. Rossi et al. [

7] observed an increase in IL-10 at the end of the annual season with larger increases noted compared to the preseason (+3.4 [0.31 to 5.89] pg·mL

-1;

p=0.047).

This investigation represents the first attempt to analyze the cytokine dynamics during a padel match while examining potential differences based on side of play and sex. No significant differences were found for these factors, suggesting that the side of play is not a major determinant of inflammatory response. Instead, other variables, such as technical, tactical or fitness-related differences, may influence match outcomes. Previous studies have noted that right-side players tend to exhibit higher intensity during rallies, with longer recovery times between points compared to left-side players, potentially leading to distinct physiological demands on the 2 sides [

25]. Regarding fitness levels, Ortega-Zayas et al. [

14] observed significant differences in lower-limb strength among female players based on their side of play, with left-side players demonstrating better active and reactive strength.

4.1. VO2max and Sex-Related Differences

The VO

2max values obtained from the laboratory tests revealed differences between female and male players, with values ranging from 47.4±4.8 and 57.5±5.7 mL·kg

-1·min

-1 (

p≤0.01), respectively. These results are consistent with those reported by Pradas et al. [

26], who observed values between 46.8±4.6 and 55.4±7 mL·kg

-1·min

-1. Similarly, Pradas et al. [

9] documented VO

2max values of 47.5±4.9 and 57.5±5.7 mL·kg

-1·min

-1 for female and male players, respectively. In tennis lower values have been observed for female players (40.9±4.3 mL·kg

-1·min

-1) [

27], while in badminton, male players demonstrated values of 45.2±8.7 mL·kg

-1·min

-1 [

28]. The sex-related differences in VO

2max may be attributed to physiological factors and match-related variables, such as point duration, match duration and distance covered. García-Benítez et al. [

23] reported that female players had longer point durations, more points per game, and overall longer match times compared to their male players.

When dividing players by sex and side of play, significant differences in VO2max were noted. FRS had lower values (46.2±4.7 mL·kg-1·min-1) compared to MRS (61±6.2 mL·kg-1·min-1; p=0.001) and MLS (55.2±4.4 mL·kg-1·min-1; p=0.04). FLS also had lower VO2max values (48.9±5.1 mL·kg-1·min-1) compared to MRS players (61±6.2 mL·kg-1·min-1; p=0.01). No significant differences were observed between MLS and FLS players. These differences may be influenced by sex, the number of strokes performed per side of play and the distance covered during matches.

4.2. Impact of the Playing Side on Heart Rate

Regarding heart rate, our results are consistent with those of Pradas et al. [

9] who reported HR

max of 186.2 ±7.8 bpm for males and 183.3±1 bpm in females. HR

mean during matches was 72.7±9.8% and 77.2±5.8% HR

max for males and females, respectively. In tennis, wider HR

mean values have been reported, ranging from 60–80% HR

max [

29]. In table tennis, lower HR

mean values were observed, ranging from 70.2±4.1% to 71.4±7.0% HR

max [

30], while in badminton, higher HR

mean values have been reported for both female and male players, ranging from (87.1–93 % HR

max) [

31].

In competitive padel matches, no significant differences were found in HR

max during laboratory tests or in HR

mean during matches based on the side of play. However, right-side players exhibited slightly higher values than left-side players. Similarly, Sánchez & Martínez [

32] found no significant differences in HR

max or HR

mean between sexes or sides of play. However, their results showed an average of 9-10 strokes per point for both male and female players, with left-side players gradually increasing their number of strokes.

In contrast, Carbonell-Martínez et al. [

15] observed significant differences in both HR

max and HR

mean based on the side of play among female players. FRS had higher HR

max values (181±9.2 bpm) compared to FLS (177±10.5 bpm). Similarly, HR

mean values during matches were higher for FRS (153±7.8 bpm) than for FLS (147±9.6 bpm). These differences could be attributed to variations in the number of actions or strokes performed by players on each side, which may influence cardiovascular demands during matches.

4.3. Limitations

The primary limitations of this study include the small sample size and the high interindividual variability in baseline interleukin levels and exercise responses, which limited the ability to draw more definitive conclusions. The variability made it challenging to detect consistent patterns across participants. Furthermore, the study did not quantify the number of actions or strokes performed by players, which could have provided valuable insights into the technical and tactical demands influencing physiological responses. Additionally, the study's cross-sectional design does not allow for the assessment of long-term adaptations or changes in inflammatory responses due to regular padel practice. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings, as they may impact the generalizability and applicability of the results.

5. Conclusions

Our findings confirm that padel is a racket sport associated with an anti-inflammatory response. The observed decrease in the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-7, coupled with a moderate increase in IL-8, suggests a positive modulation of the body’s anti-inflammatory response during padel practice. Moreover, the increase in the anti-inflammatory interleukin IL-10, which plays a crucial role in suppressing cytokine synthesis, further supports the reduction of pro-inflammatory response. These effects may be attributed to the moderate intensity of padel, which likely contributes to a reduction in oxidative stress.

Additionally, this study introduced a novel perspective by examining the inflammatory response in relation to the player’s side of play on the court. The results align with previous research, suggesting that the side of play does not significantly affect immune system responses. However, future studies should explore other variables, such as the type of strokes performed by players on each side, possible sex-related differences, and hormonal or psychological factors that may influence inflammatory and physiological responses. Larger sample sizes and longitudinal study designs could provide further insights into seasonal or chronic adaptations, while comparisons with other racket sports would help contextualize padel’s unique physiological demands.

Finally, the findings support the notion that padel can be considered as a health-promoting physical activity, given its potential protective effects on the immune system and its contribution to overall well-being.

Author Contributions

M.P.C.D. participated in the design of the study and data analysis; F.P., M.L. participated in the design of the study, data collection and interpretation of results; P.P. participated in the design of the study and interpretation of results; L.C., A.G.G. participated in data analysis and interpretation of results. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Funding

This research was subsidized through a research grant received from the Institute of Altoaragoneses Studies of the Provincial Council of Huesca (Spain) (code 85/2012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of the Department of Health than Consumption of the Government of Aragón, Spain (approval code: 21/2012; December 19, 2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply appreciate the time and dedication of all participants, which were vital to the success of this study. Furthermore, we acknowledge the invaluable contributions and support of the ENFYRED research group, whose involvement was instrumental.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| ES |

Effect size (ES) |

| FLS |

Female players on the left side (FLS) |

| FRS |

Female players on the right side (FRS) |

| HRmax

|

Maximum heart rate |

| HRmean

|

Mean heart rate |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| IL-1 |

Interleukin-1 |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10 |

| IL-13 |

Interleukin-13 |

| IL-5 |

Interleukin-5 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| LIF |

Leukemia inhibitory factor |

| MLS |

Male players on the left side (MLS) |

| MRS |

Male players on the right side (MRS) |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| VO2max

|

maximal oxygen consumption |

References

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle–Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas de Lucas, R.; Caputo, F.; Mendes de Souza, K.; Sigwalt, A.R.; Ghisoni, K.; Lock Silveira, P.C.; Remor, A.P.; da Luz Scheffer, D.; Antonacci Guglielmo, L.G.; Latini, A. Increased platelet oxidative metabolism, blood oxidative stress and neopterin levels after ultra-endurance exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, R.A.; Silva, L.A.; Pinho, C.A.; Scheffer, D.L.; Souza, C.T.; Benetti, M.; Carvalho, T.; Dal-Pizzol, F. Oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters after an ironman race. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2010, 20, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, E.; Zembroń-Lacny, A.; Kasperska, A.; Antosiewicz, J.; Grzywacz, T.; Garsztka, T.; Laskowski, R. Exercise training-induced changes in inflammatory mediators and heat shock proteins in young tennis players. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowska, M.; Zurek, P.; Rodziewicz, E.; Góral, K.; Zmijewski, P.; Lipinska, P.; Laskowski, R.; Walentukiewicz, A.K.; Antosiewicz, J.; Ziemann, E. Immunological response and match performance of professional tennis players of different age groups during a competitive season. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.E.; Maldonado, A.J.; Cholewa, J.M.; Ribeiro, S.L.G.; de Araújo Barros, C.A.; Figueiredo, C.; Reichel, T.; Krüger, K.; Lira, F.S.; Minuzzi, L.G. Exercise training-induced changes in immunometabolic markers in youth badminton athletes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Cachón, J.; Otín, D.; Quintas, A.; Arracos, S.I.; Castellar, C. Anthropometric, physiological and temporal analysis in elite female paddle players. Retos 2014, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pradas, F.; Cadiz, M.P.; Nestares, M.T.; Martinez-Diaz, I.C.; Carrasco, L. Effects of Padel Competition on Brain Health-Related Myokines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Llin, J.; Guzman-Lujan, J.F.; Martinez-Gallego, R. Comparison of heartrate between elite and national paddle players during competition. Retos 2018, 33, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, D. da L.; Latini, A. Exercise-induced immune system response: Anti-inflammatory status on peripheral and central organs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Giménez, A.; Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Castellar Otín, C.; Carrasco Páez, L. Performance outcome measures in padel : A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Miguel Physiological, physical and anthropometric parameters in padel: A systematic review. Aγαη 2024, 15, 37–48.

- Ortega-Zayas, M.Á.; García-Giménez, A.; Casanova, Ó.; Latre Navarro, L.; Pradas, F.; Moreno-Azze, A. Evaluation of active and reactive manifestations in female padel players. Influence of the playing side. Padel Sci. J. 2024, 2, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell-Martínez, J.A.; Ferrándiz-Moreno, J.; Pascual-Verdú, N. Analysis of heart rate in amateur female padel. Retos 2017, 32, 204–207. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; 11th ed.; Lippincott Connect-ACSM, 2021; ISBN 9781975150181.

- Nieman, D.C. Immune response to heavy exertion. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 82, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pablo Sánchez, R.; Monserrat Sanz, J.; Prieto Martín, A.; Reyes Martín, E.; Álvarez de Mon Soto, M.; Sánchez García, M. The balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory citokines in septic states. Med. Intensiva 2005, 29, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Cádiz, M.P.; Moreno-Azze, A.; Martínez-Díaz, I.C.; Carrasco, L. Acute Effects of Padel Match Play on Circulating Substrates, Metabolites, Energy Balance Enzymes, and Muscle Damage Biomarkers: Sex Differences. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.; Romero, S.; Sañudo, B.; de Hoyo, M. Game analysis and energy requirements of paddle tennis competition. Sci. Sport. 2011, 26, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rodríguez, A.; Alvero-Cruz, J.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; García, F.J. Physical and physiological responses in paddle tennis competition. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2014, 14, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Benítez, S.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Pérez-Bilbao, T.; Felipe, J.L. Game Responses During Young Padel Match Play: Age and Sex Comparisons. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek, K.; Zurek, P.; Zmijewski, P.; Jaworska, J.; Lipińska, P.; Dzedzej-Gmiat, A.; Antosiewicz, J.; Ziemann, E. Myokines in response to a tournament season among young tennis players. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Llin, J.; Guzmán, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Stroke analysis in padel according to match outcome and game side on court. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; García-Giménez, A.; Toro-Román, V.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Ochiana, N.; Castellar, C. Effect of a padel match on biochemical and haematological parameters in professional players with regard to gender-related differences. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, M.W.; Hotfiel, T.; Stückradt, A.; Grim, C.; Ueberschär, O.; Freiwald, J.; Baumgart, C. Effects of passive, active and mixed playing strategies on external and internal loads in female tennis players. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, P.; Berg, K.; Harder, J.; Batelaan, H.; McGRATH, M. Oxygen cost and physiological responses of recreational badminton match play. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2017, 57, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killit, B.; Arslan, E.; Soylu, Y. Time-motion characteristics, notational analysis and physiological demands of tennis match play: a review. Acta Kinesiol. 2018, 12, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pradas, F.; de la Torre, A.; Castellar, C.; Toro-Román, V. Physiological profile, metabolic response, and temporal structure in elite individual table tennis: Differences according to gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarirajan, R. Result of Heart Rate, Playing Time and Performance of Tamilnadu Badminton Senior Ranking Players. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Fit. 2016, 6, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Game actions and temporal structure differences between male and female professional paddle players. Acción Mot. 2014, 12, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).