1. Introduction

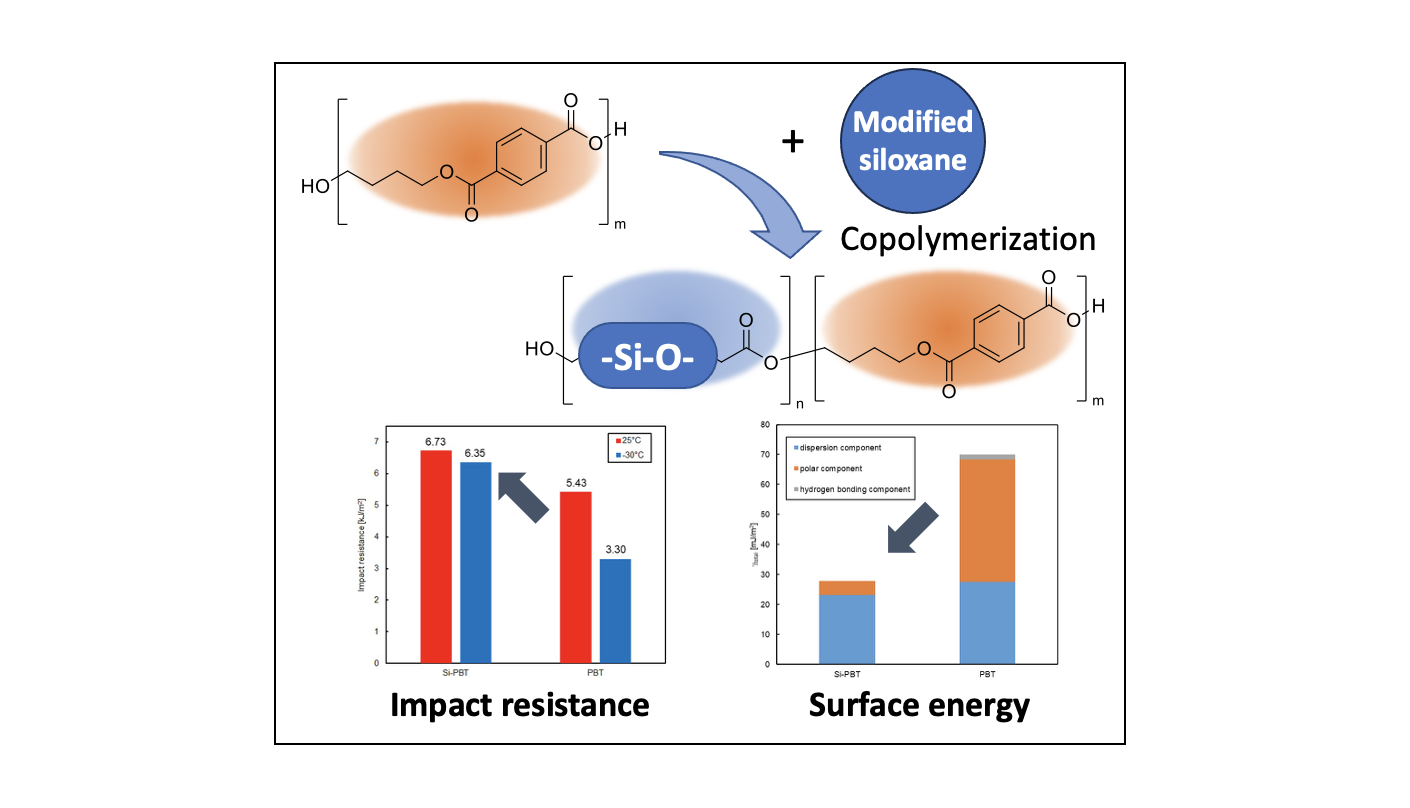

Polyesters are widely used in various industries, including textiles, packaging, and engineering applications, due to their excellent mechanical properties, processability, and thermal stability. However, their surfaces often exhibit hydrophilic characteristics, leading to limitations in water resistance and contamination prevention[

1,

2]. Recently, as the push for monomaterialization has intensified, there has been a growing demand for the development of coating-free materials by directly imparting functionality to plastics. From this perspective, achieving hydrophobization of polyester surfaces is a crucial aspect of material design.

Siloxane copolymerization has emerged as a promising strategy for modifying polymer surfaces, as siloxanes possess inherently low surface energy and excellent water-repellent properties[

3,

4,

5]. The incorporation of siloxane into polyester structures offers the potential to significantly improve hydrophobicity while maintaining the desirable mechanical properties of the base polymer. Furthermore, siloxane provides flexibility to polymer, which could enhance impact resistance, particularly in low-temperature environments. However, although several studies have explored siloxane copolymerization with polyesters, a key challenge remains: achieving uniform copolymerization while fully harnessing the advantageous characteristics of siloxanes[

6,

7]. Previous approaches have often resulted in phase separation or poor compatibility, hindering optimal material performance and limiting practical applications.

The difficulty in achieving homogeneous copolymerization arises from the intrinsic differences in polarity between polyesters and siloxanes. Polyesters generally possess high polarity, whereas siloxanes exhibit low polarity, making uniform incorporation challenging[

8,

9,

10]. This incompatibility often leads to bleed-out of siloxane to the surface, decreasing the intended hydrophobic effects. Addressing this issue requires advancements in molecular architecture to improve the compatibility between these two components.

In this study, we focus on the molecular design and synthesis of novel siloxane comonomers specifically tailored for polyester copolymerization. By optimizing the chemical structure and compatibility of these comonomers, we aim to facilitate seamless integration into the polyester matrix, promoting uniform copolymer formation and enhancing surface hydrophobicity. The synthesized copolymers are evaluated through structural characterization, contact angle measurements, and mechanical testing under various conditions. We investigate the influence of siloxane incorporation on both the surface properties and low-temperature impact resistance of the polyester material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Equipment

The Fourier transform nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of oligosiloxanes were obtained using a JEOL JNM-ECA 400 (1H at 399.78 MHz) and a JEOL JNM-ECA 600 (13C at 150.91 MHz, 29Si at 119.24 MHz) NMR instrument. NMR spectra of PBTs were obtained using Bruker AVANCE600 (1H at 600.1 MHz, 13C at 151 MHz, 29Si at 119.2 MHz) NMR instrument. For 1H NMR, chemical shifts were reported as δ units (ppm) relative to SiMe4 (TMS), and the residual solvent peaks were used as standards. For 13C NMR and 29Si NMR, chemical shifts were reported as δ units (ppm) relative to SiMe4 (TMS). The residual solvent peaks were used as standards, and the spectra were acquired with complete proton decoupling. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization coupled time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass analyses were performed by a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) AXIMA Performance instrument, using 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (dithranol) as the matrix and AgNO3 as the ion source. All used reagents were of analytical grade. Elemental analyses were performed at the Center for Material Research by Instrumental Analysis (CIA), Gunma University, Japan. TGA was performed using a Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) thermogravimetric analyzer (Thermoplus TG-DTA8122). The investigations were carried out under nitrogen flow (50 mL min−1) or airflow (50 mL min−1) at a heating rate of 10°C min−1. All samples were measured in a temperature range of 25 to 450°C, with a 5 min hold at 450°C. The weight loss and heating rate were continuously recorded during the experiment. Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) was performed using a Mettler toledo (Columbus, OH, USA) DSC3. The investigations were carried out under nitrogen flow (40 mL min−1) at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 and a cooling rate of 10°C min−1. All samples were measured in a temperature range of −50 to 300°C, with a 5 minutes hold at the end of each process; −50°C and 300°C. Contact angle measurements were performed using a Kyowa interface science co. LTD. (Tokyo, Japan) CA-X150. The contact angles were observed 0.1 seconds after dropping. Impact tests were performed using a TOYOSEIKI (Tokyo, Japan) impact tester (D-CB). Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was performed using a Tosoh Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) HLC-8220 instrument. Chloroform was used as mobile phase at 40°C. PLgel 10μ Mixed-B (7.5mm I.D.×30cmL×2) was chosen as column.

2.2. General Considerations of Synthesis

The synthesis of oligosiloxanes was performed under an argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques, unless otherwise noted. Polymerization reactions were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and toluene were dried using an mBRAUN solvent purification system. Trimethyltrivinylcyclotrisiloxane, hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane, chlorodimethylvinylsilane, 2,2’-azobis(isobutyronitrile)) (AIBN), tetrabutyl orthotitanate, and magnesium acetate were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Toluene, 2-mercaptoethanol, NaHCO

3, CH

2Cl

2, Na

2SO

4, and magnesium acetate were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Tokyo, Japan).

n-Butyllithium (1.6 M in hexane) was purchased from KANTO CHEMICAL CO., INC. (Tokyo, Japan). 1,4-Butanediol was purchased from Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). Dimethyl terephthalate was purchased from SK chemicals Corporation (Gyeonggi, Korea). All reagents were used as received without further purification. 2-[2-(2-Mercapto Ethoxy)ethoxy]ethanol was synthesized using a modification of a known procedure[

11].

2.3. Synthetic Procedures of Compounds

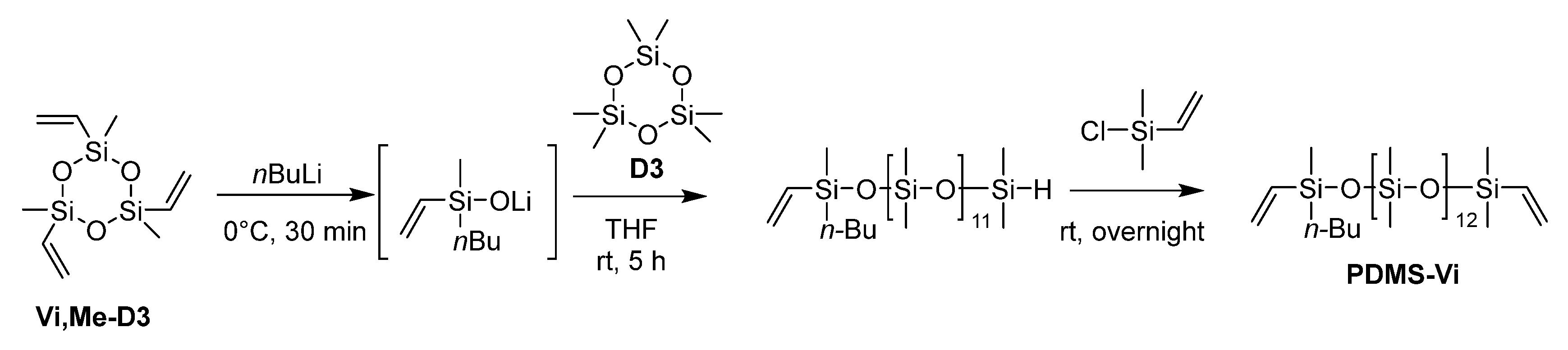

2.3.1. Synthesis of PDMS-Vi

The ring-opening reaction conditions using

n-butyllithium (

nBuLi) were optimized based on those reported in the literature [

12].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PDMS-Vi.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PDMS-Vi.

An argon-purged, three-necked, 100 mL round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar was charged with trimethyltrivinylcyclotrisiloxane (Vi,Me-D3) (1.35 mL, 5.0 mmol) and dry toluene (1.50 mL). The mixture was cooled to 0 ˚C and nBuLi (1.6 M in hexane, 9.40 mL, 15.0 mmol) was added dropwise into the mixture under argon at 0°C. After the addition, the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 minutes at 0˚C. Hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane (D3) (13.4 g, 60.0 mmol) was then added into the reaction mixture, followed by the addition of dry THF (2.50 ml, 30.8 mmol) as a polymerization promoter at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 hours at room temperature, and then a slight excess of chlorodimethylvinylsilane (2.14 mL, 15.5 mmol) was added to terminate the polymerization. The solution was stirred overnight at room temperature and then washed three times with brine. The organic layer was evaporated by a rotary evaporator for 1.5 hours at 35°C, and then dried under vacuum at 60°C for > 3 hours to afford PDMS-Vi (9.60 g, 8.58 mmol, 57% yield) as a transparent colorless liquid.

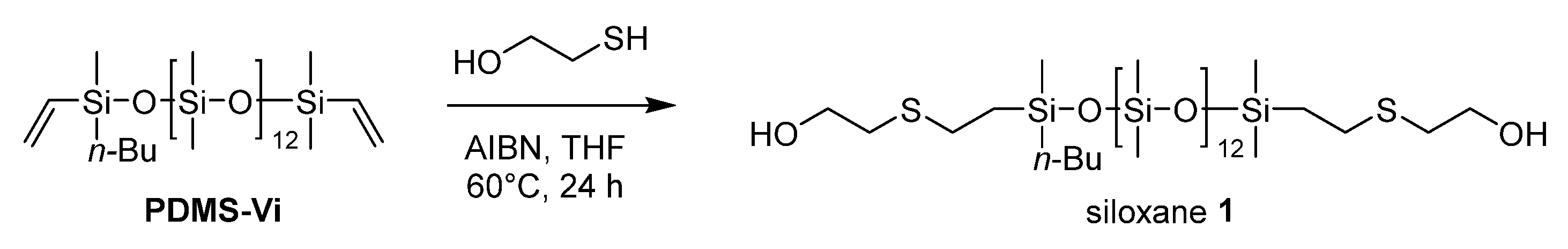

2.3.2. Synthesis of Siloxane 1

The thiol-ene reaction conditions using 2,2’-azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN) were optimized based on those reported in the literature [

13,

14,

15].

An argon-purged Schlenk flask equipped with a stir bar was charged with AIBN (19.7 mg, 0.12 mmol) and anhydrous THF (10 mL). The solution was stirred for 5 minutes at room temperature and PDMS-Vi (6.21 mL, 5 mmol) was added. The mixture was heated to 40˚C and after stirring for 10 minutes, 2-mercaptoethanol (1.06 mL, 15 mmol) was added dropwise at 40°C. The mixture was then heated to 60°C and stirred at 60°C for 24 hours. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and quenched with saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution (20 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times, and the gathered organic layer was washed with water three times and brine two times, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration, the solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator to afford siloxane 1 (5.23 g, 4.10 mmol, 82% yield) as a slightly yellow viscous oil.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of siloxane 1.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of siloxane 1.

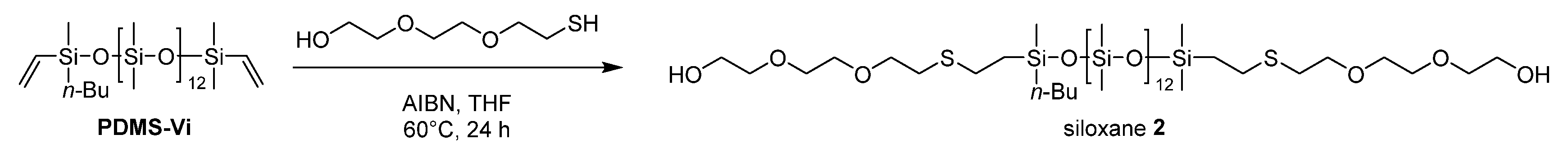

2.3.3. Synthesis of Siloxane 2

An argon-purged Schlenk flask equipped with a stir bar was charged with AIBN (19.7 mg, 0.12 mmol) and anhydrous THF (10 mL). The solution was stirred for 5 minutes at room temperature and PDMS-Vi (6.21 mL, 5 mmol) was added. The mixture was heated to 40˚C and after stirring for 10 minutes, 2-[2-(2-Mercapto Ethoxy)ethoxy]ethanol (2.15 mL, 15 mmol) was added dropwise at 40°C. The mixture was then heated to 60°C and stirred at 60°C for 24 hours. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and quenched with saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution (20 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times, and the gathered organic layer was washed with water three times and brine two times and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration, the solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator to afford siloxane 2 (5.90 g, 4.01 mmol, 81% yield) as a slightly yellow viscous oil.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of siloxane 2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of siloxane 2.

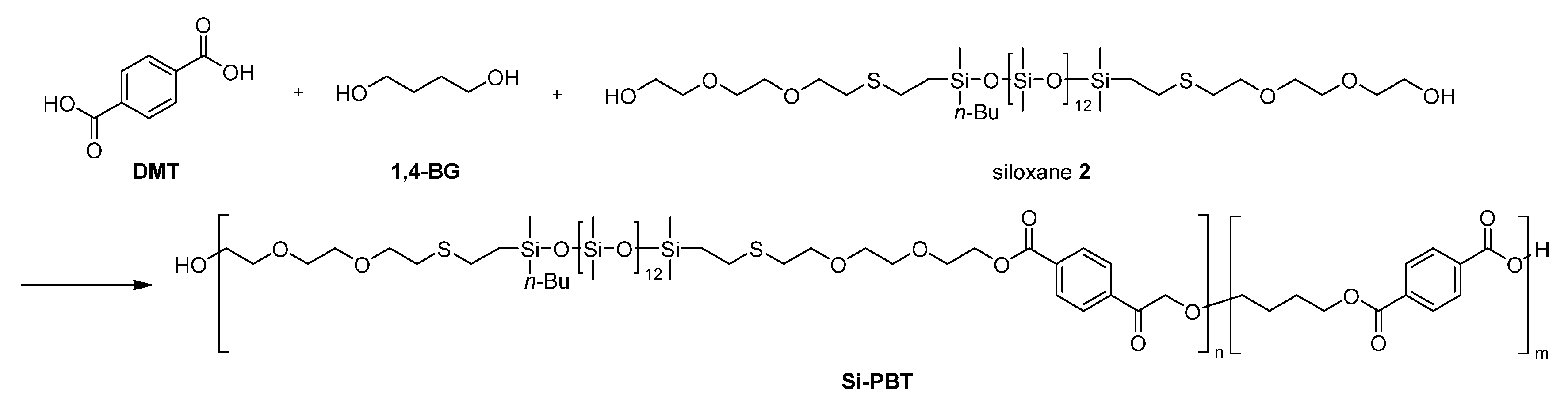

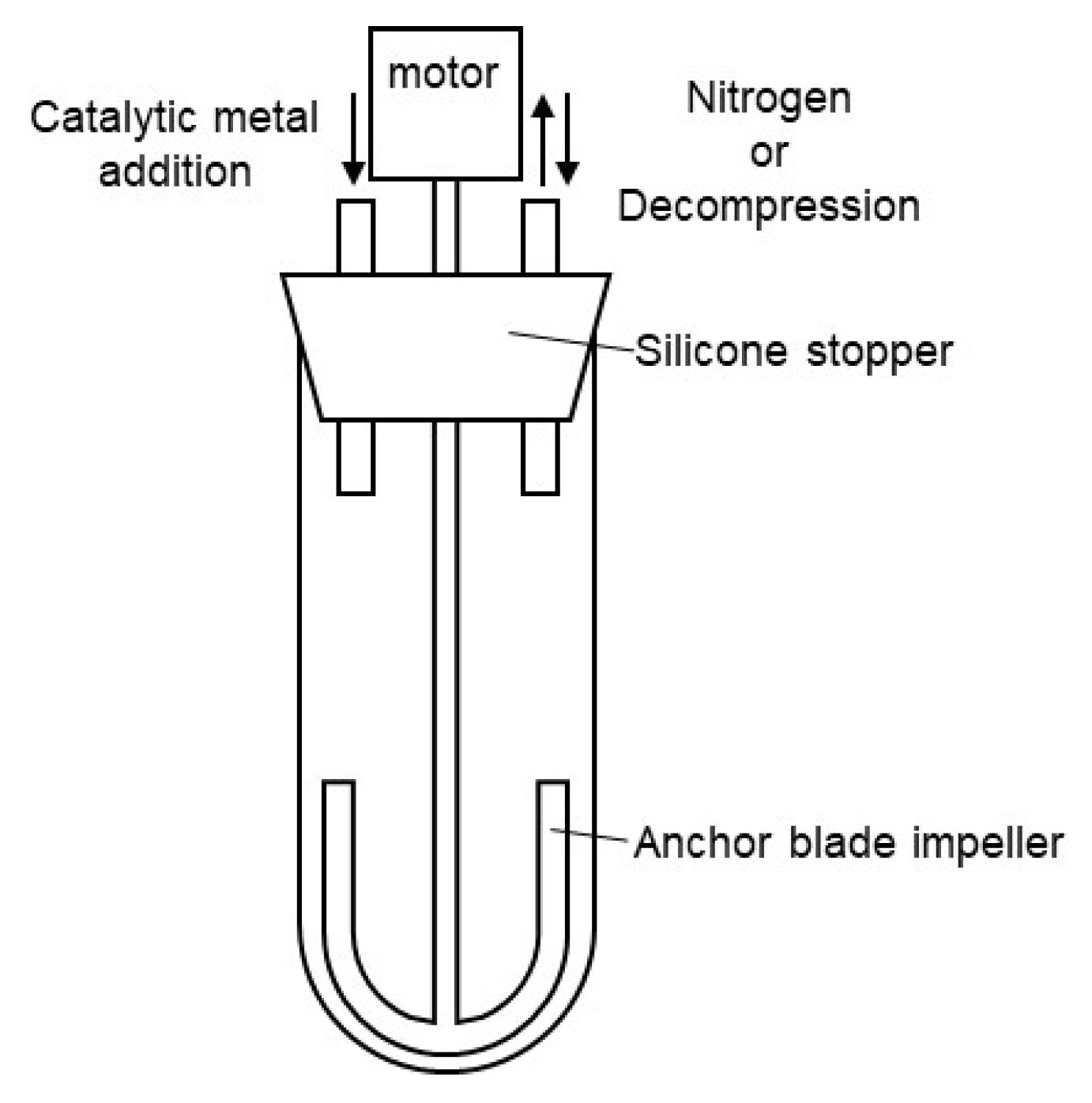

2.3.4. Synthesis of Si-PBT

A nitrogen-purged grass reactor, as shown in

Figure 1, was charged with dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) (15.9 g, 0.08 mol), 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BG) (8.12 g, 0.09 mol), and siloxane 2 (7.71 g, 8.2 mmol), and then heated to 150°C. Tetrabutyl orthotitanate (6.0wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 0.10 g, 234 ppm) was added to the melted mixture under a nitrogen atmosphere at 150°C. After the addition, the mixture was heated to 210°C over 105 minutes, and stirred at 210°C for 60 minutes. The transesterification reaction was completed and 5.2 mL of methanol was distilled off. Then, magnesium acetate (10.0 wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 0.11 g, 423 ppm) and tetrabutyl orthotitanate (6.0 wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 0.18 g, 433 ppm) were added to the mixture under a nitrogen atmosphere at 210°C. After the addition, the reaction system was gradually decompressed to 1 torr over 90 minutes. 5 minutes after the start of decompression, the temperature was increased to 240°C over the course of 90 minutes. Continued stirring at 240°C for an additional 90 minutes afforded silicone-copolymerized polybutylene terephthalate (Si-PBT) as a transparent viscous liquid. Upon removal from the reactor, the product solidified into a crystalline white solid (19.8 g).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Si-PBT.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Si-PBT.

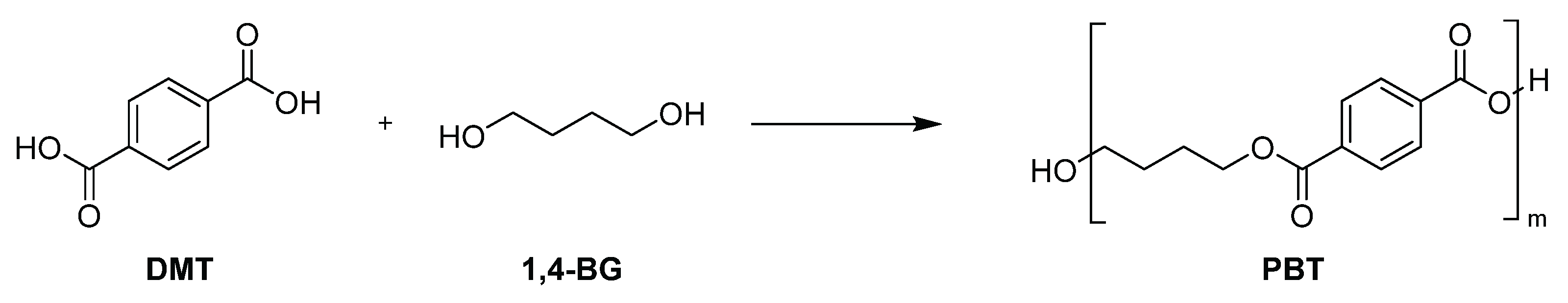

2.3.5. Synthesis of PBT

A nitrogen-purged grass reactor, as shown in

Figure 1, was charged with dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) (132.27 g, 0.68 mol) and 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BG) (73.66 g, 0.82 mol) was heated to 150°C. Tetrabutyl orthotitanate (6.0 wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 0.59 g, 234 ppm) was added to the melted mixture under a nitrogen atmosphere at 150°C. After the addition, the mixture was heated to 210°C over 105 minutes and stirred at 210°C for 60 minutes. The transesterification reaction was completed and 50 mL of methanol was distilled off. Then, magnesium acetate (10.0 wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 0.64 g, 423 ppm) and tetrabutyl orthotitanate (6.0 wt% in 1,4-BG solution, 1.08 g, 433 ppm) were added to the mixture under a nitrogen atmosphere at 210°C. After the addition, the reaction system was gradually decompressed to 1 torr over 90 minutes. 5 minutes after the start of decompression, the temperature was increased to 240°C over the course of 90 minutes. Continued stirring at 240°C for an additional 90 minutes afforded polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) as a transparent viscous liquid. Upon removal from the reactor, the product solidified into a crystalline white solid (121.2 g).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of PBT.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of PBT.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Siloxane-Based Comonomers

The targeted polyester-friendly siloxane-based comonomers were designed to slightly increase the polarity of the siloxane. Specifically, oligosiloxanes modified with oligoethyleneoxides at both termini (

Scheme 2 and

Scheme 3) were synthesized. The starting compound PDMS-Vi was synthesized by ring opening polymerization (ROP) of hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane (D3) using an appropriate initiator and end-capping agent (

Scheme 1). The degree of polymerization was adjusted so that each molecule contained 14 silicon atoms. Short siloxane chains cannot achieve hydrophobicity and low-temperature impact resistance because polysiloxane forms one helix per 6 silicone atoms[

16,

17,

18]. On the other hands, long siloxane chains deteriorate compatibility with polyester, as the long siloxane chains reduce the overall molecular polarity[

19,

20,

21].

The thiol-ene reaction was adopted as a strategy of introducing oligoethyleneoxides into oligosiloxanes [

14,

15]. Herein, we synthesized ethanol-modified siloxane 1 and dioxyethylene ethanol-modified siloxane 2.

3.2. Copolymerization of Oligosiloxanes and Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT)

The copolymerization of oligosiloxanes and polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) was proceeded in two steps. The first step involved transesterification reaction, in which oligosiloxane, 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BG) and dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) reacted to form copolyester oligomer (

Scheme 4 and

Scheme 5). In the case of siloxane 1, phase separation occurred between 1 and 1,4-BG. The polarity of siloxane 1 was too low, causing the reaction melt to separate into two distinct phases. As a result, the subsequent polymerization step encountered an issue where the expansion torque did not increase sufficiently during the reaction. This is presumed to be due to the difficulty of siloxane's reactive sites encountering those of DMT during transesterification, leading to a large amount of unreacted siloxane remaining in the siloxane phase prior to the second step. In contrast, siloxane 2 had sufficiently high polarity to achieve uniform transesterification reaction.

The second step was polymerization reaction, in which the oligomers extended their chain length to form polymers. As the degree of polymerization increased, the viscosity of the melt rose, leading to a higher expansion torque. When siloxane 1 was used, the stirring torque did not increase, whereas when siloxane 2 was used, the stirring torque increased to the expected value and the copolyester resin Si-PBT was successfully obtained. This indicates that newly developed siloxane 2 has sufficient affinity for polyester and is capable of effective copolymerization. For comparison, a PBT resin was also synthesized using the same method as for Si-PBT, but without using siloxane. The intrinsic viscosities and molecular weights of Si-PBT and PBT are shown in

Table 1. Both materials were found to have a sufficient degree of polymerization for property evaluation.

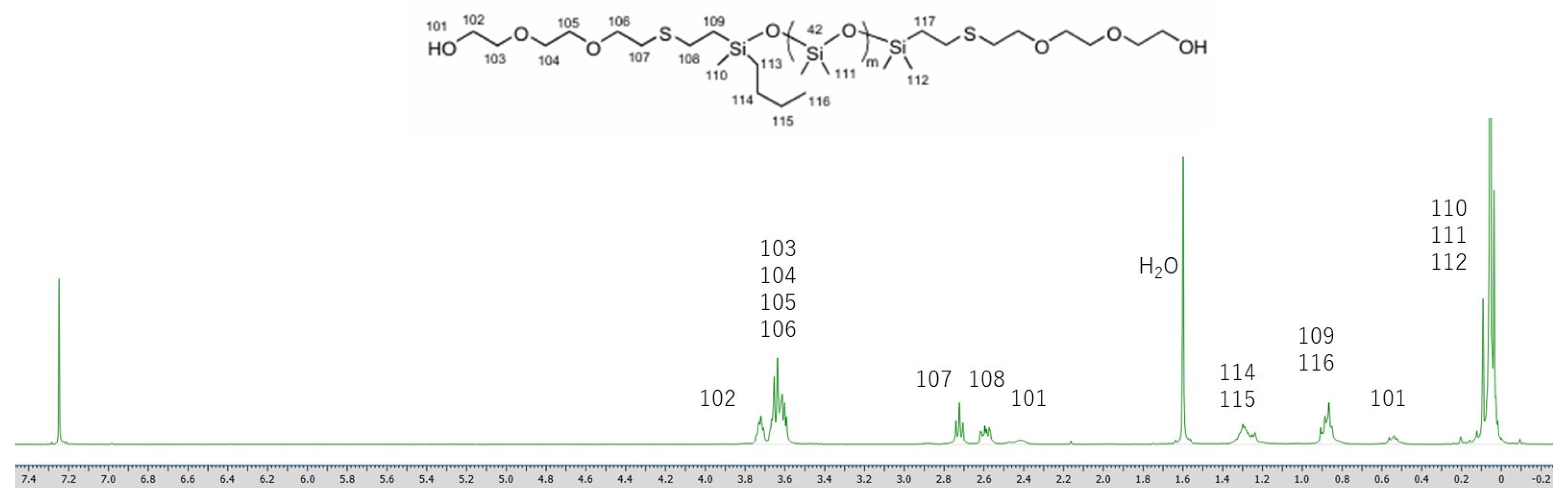

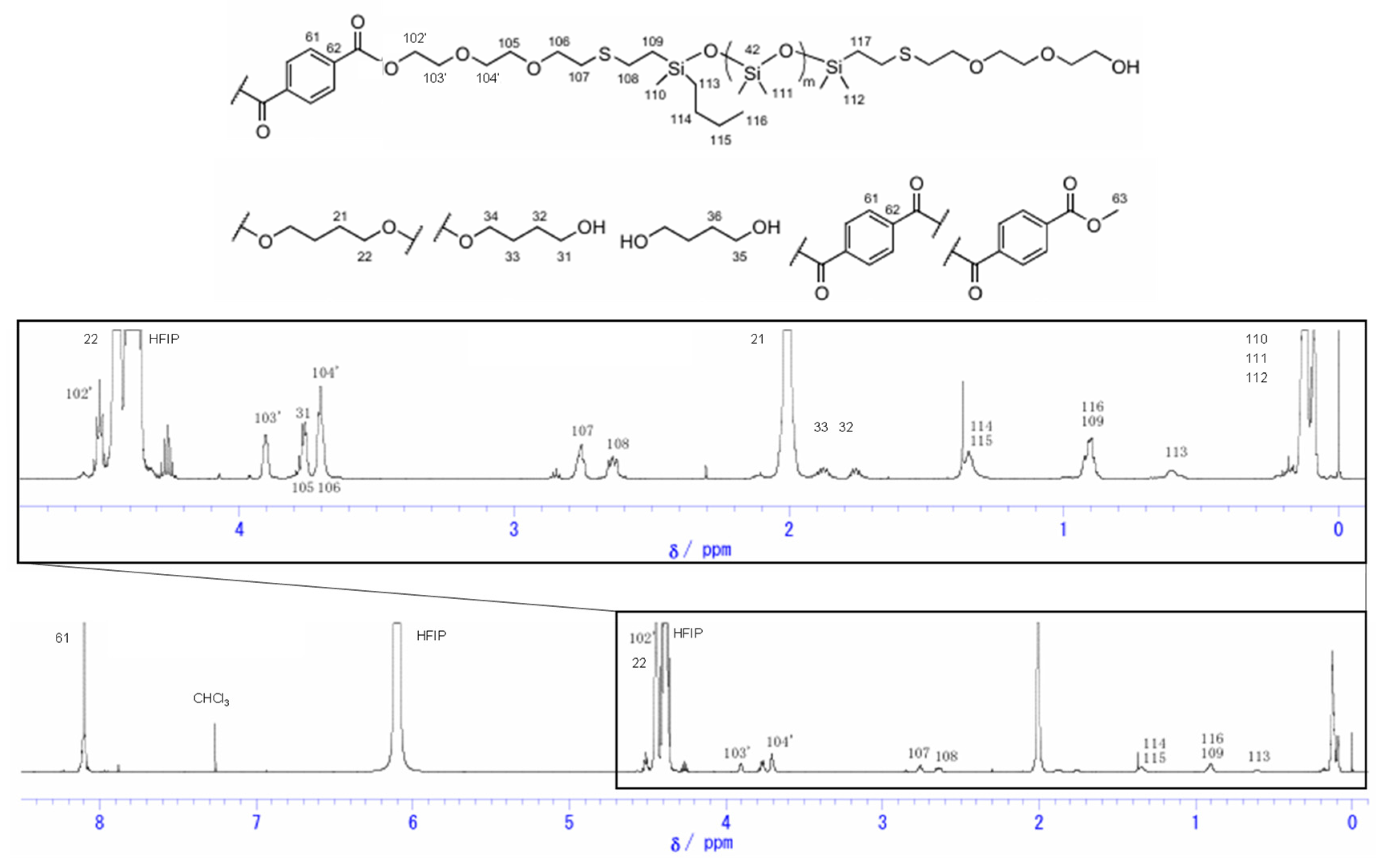

The

1H NMR spectra of siloxane

2 and

Si-PBT are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. In

Figure 3, the disappearance of the 3.73 ppm peak assigned to H102, along with the appearance of the 4.50 ppm peak (H102') and the 3.90 ppm peak (H103'), indicates that copolymerization between siloxane 2 and PBT was successfully achieved. The composition ratio of repeating units in Si-PBT, calculated from both the monomer feed ratio and the ratio determined by

1H NMR analysis, is shown in

Table 2. These results confirm that no decomposition or volatilization of siloxane occurred, and that copolymerization proceeded successfully while maintaining the intended composition ratio.

The results of the polymerization experiment revealed that introducing highly polar oxyethylene groups at both termini of siloxane enhances its affinity for polyester, leading to the formation of a uniform copolymer.

3.3. Thermal Properties of Oligosiloxanes and Copolyesters

To evaluate the thermal stability of monomers and polymers, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) measurements were conducted. From the TGA analysis of the monomer 2, the temperature at which 3% weight loss (T

d3) occurred was found to be 284.3°C (

Table 3), indicating that it can withstand the polymerization process temperature of 240°C without decomposition.

The TGA analysis of the polymer showed no significant difference in weight loss behavior between Si-PBT and PBT under either nitrogen or air (

Table 4). This indicates that introduction of a siloxane backbone into PBT does not compromise its inherent high thermal resistance. Consequently, Si-PBT can be considered a viable material for electrical components and molded parts, where polyester has traditionally been used for its heat resistance.

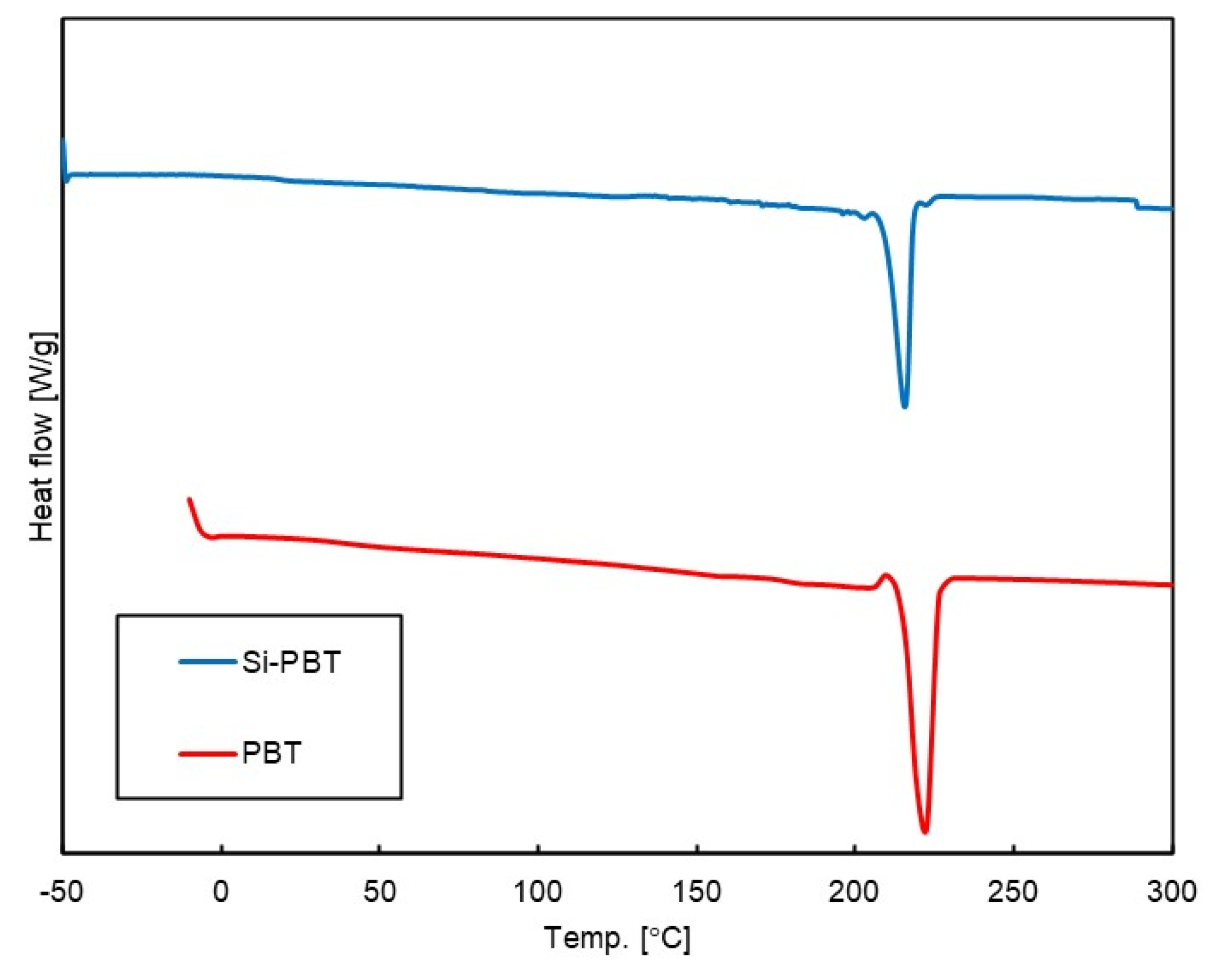

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were conducted to investigate phase transition behavior under thermal conditions. The DSC curves of the polymers are shown in

Figure 4, and the phase transition temperatures and enthalpies are listed in

Table 5. Compared to PBT, the crystallization temperature of Si-PBT is shifted to a lower value, suggesting that the incorporation of the siloxane backbone into PBT disrupts its crystalline structure. In fact, the absolute crystallization enthalpy of Si-PBT is 34.7 J/g, which is lower than that of PBT (46.8 J/g). This further supports the hypothesis that the introduction of the siloxane backbone inhibits crystallization. This inhibition indicates that siloxane and polyester are miscible on the micrometer scale.

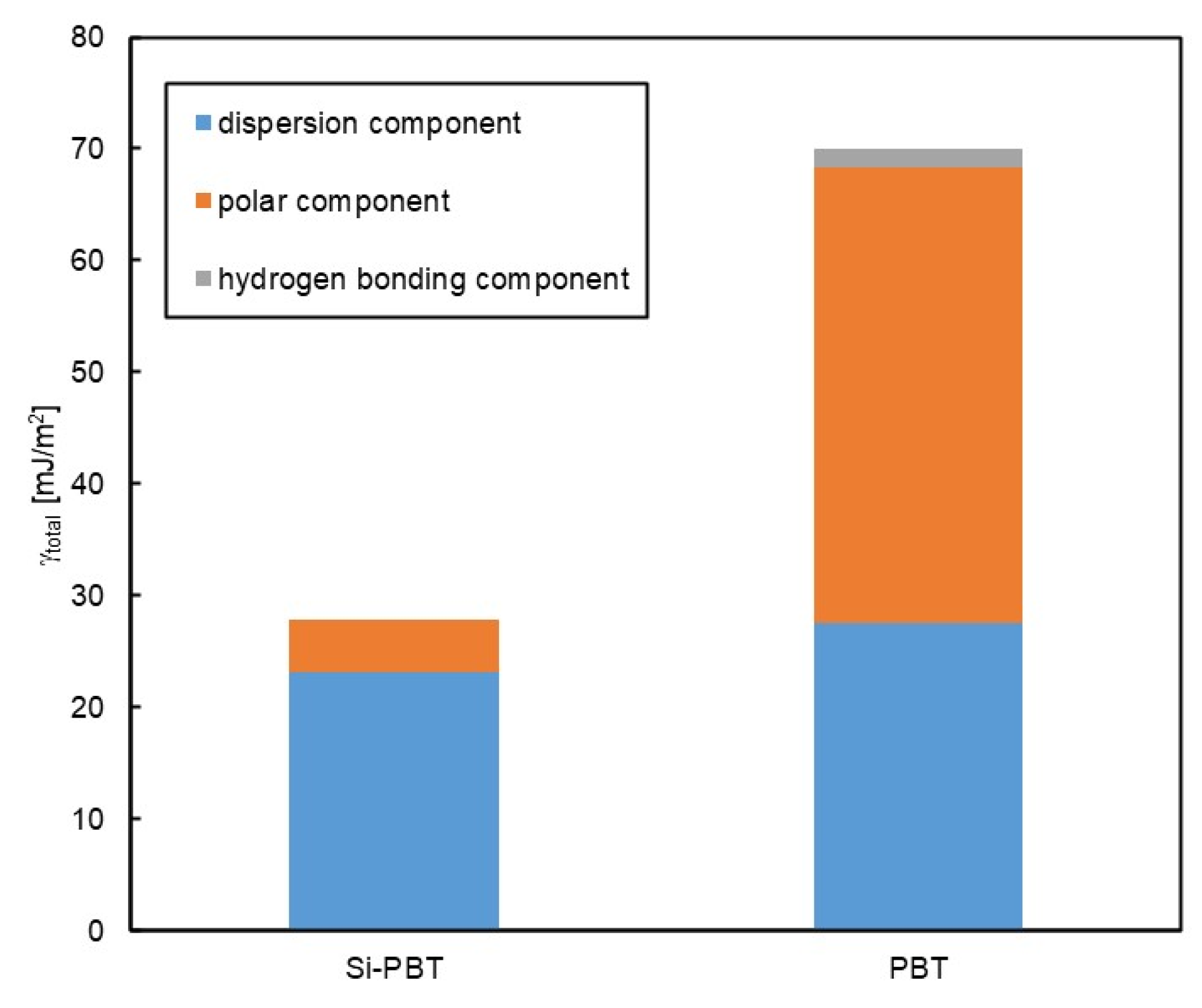

3.4. Surface Property of Copolyester

To evaluate the impact of siloxane copolymerization on the surface properties of polyester, surface contact angle measurements were conducted on Si-PBT and PBT. The samples were prepared as films using heat press molding. The results are presented in

Table 6. Si-PBT exhibited higher contact angles for all probe liquids compared to PBT, indicating improved water repellency and antifouling properties.

To conduct a more detailed analysis, surface free energy component analysis was performed using the Kitazaki-Hata theory[

22]. The results are presented in

Table 7 and Figure 7. According to this theory, the surface free energy (

γ) is divided into three components: the dispersion component (

γd), the polar component (

γp), and the hydrogen bonding component (

γh). In Si-PBT, a significant reduction in the polar component was observed. This suggests that the siloxane backbone, which has lower polarity than polyester, preferentially migrates to the surface, thereby reducing surface polarity and lowering the total surface free energy. As intended, the incorporation of the siloxane backbone successfully reduced the surface energy of polyester.

Table 7.

Surface free energy γ [mJ/m2] of Si-PBT and PBT.

Table 7.

Surface free energy γ [mJ/m2] of Si-PBT and PBT.

| |

γd

|

γp

|

γh

|

γtotal

|

| Si-PBT |

23.2 |

4.6 |

0.0 |

27.8 |

| PBT |

27.5 |

40.8 |

1.7 |

70.0 |

Figure 5.

Surface free energy of Si-PBT and PBT.

Figure 5.

Surface free energy of Si-PBT and PBT.

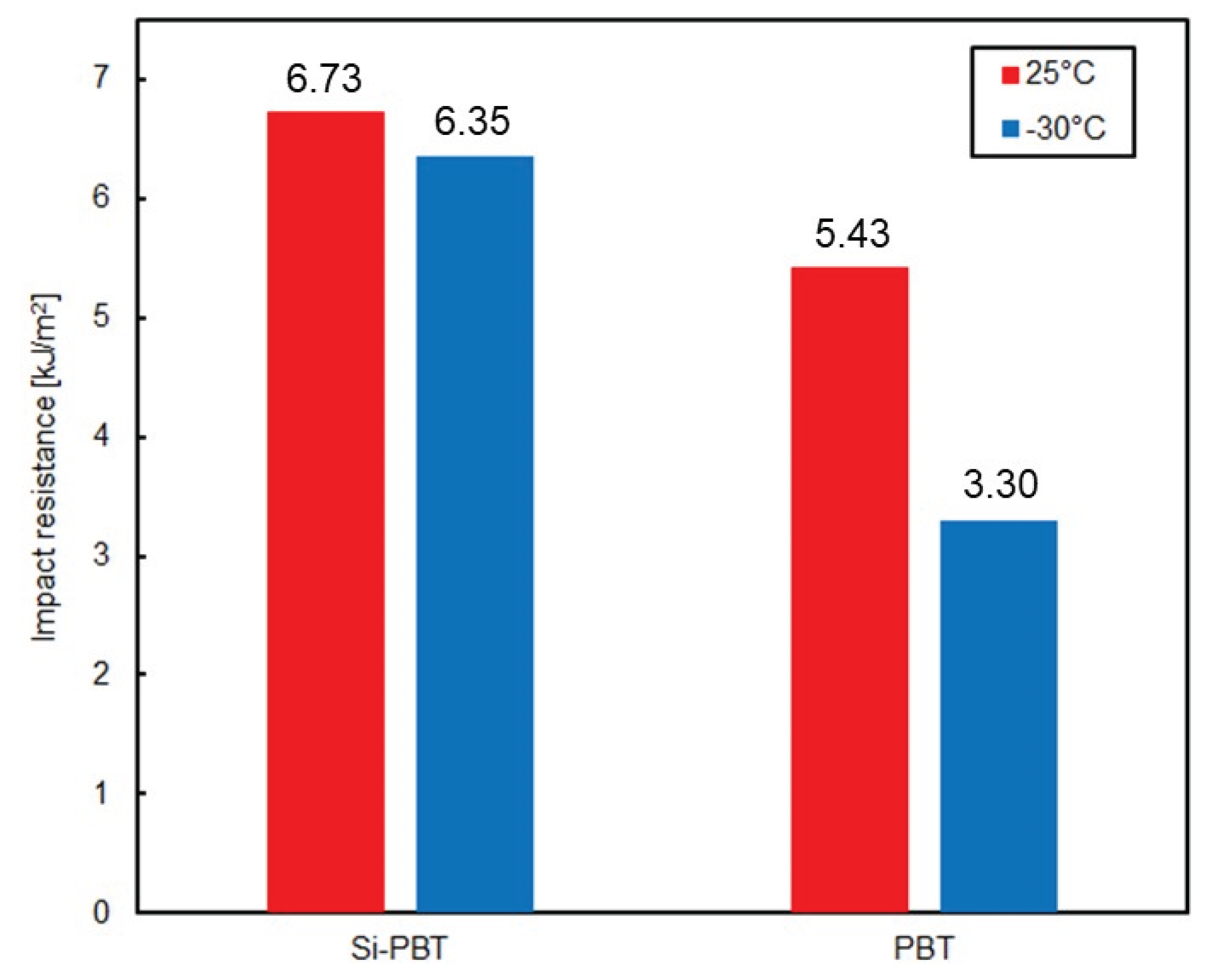

3.5. Impact Resistance of Copolyester

Finally, the impact resistance of the polyester was evaluated to determine whether the introduction of the siloxane backbone leads to improvements. The results of the Charpy impact test, conducted at room temperature (25°C) and low temperature (−30°C), are shown in and

Figure 6. Si-PBT exhibited superior impact strength compared to PBT. Notably, at −30°C, the impact strength of Si-PBT remained nearly unchanged from its room-temperature value. Such behavior is extremely rare and serves as a distinctive feature of Si-PBT.

Impact resistance generally arises from the conversion of kinetic energy into thermal energy at the molecular level within the polymer matrix. In this case, the flexible and spatially accommodating helical structure of siloxane is finely fragmented and uniformly dispersed throughout the polymer. This morphology prevents stress concentration at a single point and instead distributes the impact energy across the system, promoting efficient energy dissipation. The uniform dispersion and fine fragmentation of siloxane are further supported by the DSC results.

As shown in the DSC curve of Si-PBT in

Figure 4, no thermally induced phase transition occur between −30°C and 25°C. This thermal stability contributes to the excellent impact strength of Si-PBT at both room temperature and low temperatures.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, a novel siloxane-based comonomer for polyester was successfully designed and synthesized to improve the surface hydrophobicity and low-temperature impact resistance. By introducing siloxane into the polyester structure, we aimed to enhance water resistance while improving flexibility and mechanical durability in cold environments. The findings confirmed that a properly engineered siloxane molecular structure promotes uniform copolymerization with polyester, effectively overcoming previous challenges related to phase separation and compatibility issues.

Analysis of the synthesized copolymers demonstrated that siloxane incorporation significantly increased surface hydrophobicity, as evidenced by higher contact angles. Additionally, low-temperature impact tests indicated that the presence of siloxane contributed to enhanced flexibility, reducing brittleness and improving performance under sub-zero conditions.

The results of this study highlight the potential of molecular-level polymer design in achieving high-performance materials without the need for additional coatings. This research provides valuable insights into the development of durable, hydrophobic polyester materials suitable for various applications. Future work will focus on further optimizing siloxane composition and distribution within the polymer to achieve even greater functionality and performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. characterization data for PDMS-Vi, siloxane 1 and 2, Si-PBT, 1H, 13C, 29Si NMR spectra of PDMS-Vi, siloxane 1 and 2 (Figures S1–S12); thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) spectra for siloxane 2, Si-PBT, and PBT (Figures S13–S14).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., Y.L., T.I. and M.U.; Formal analysis, S.S., J.K., R.A., M.T. and Y.L.; Funding acquisition, T.I.; Investigation, S.S., J.K., R.A., M.T. and Y.L.; Methodology, S.S. and Y.L.; Project administration, T.I.; Writing – original draft, S.S.; Writing – review & editing, Y.L. and M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

In this study, we would like to express my sincere gratitude to Mr. Koshi Matsubara and Mr. Yosuke Kondo from Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation for their valuable technical support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sfamani, S.; Lawnick, T.; Rando, G.; Visco, A.; Textor, T.; Plutino, R.M. Super-Hydrophobicity of Polyester Fabrics Driven by Functional Sustainable Fluorine-Free Silane-Based Coatings. Gels. 2023, 9, 109. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xie, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric. e-polymers, 2021, 21, 654−661. [CrossRef]

- Endo, H.; Takeda, N.; Takanashi, M.; Imai, T.; Unno, M. Refractive Indices of Silsesquioxanes with Various Structures. Silicon, 2015, 7, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, B.; Deng, X.; Cao, S.; Hou, X.; Chen, H. A novel approach for the preparation of organic-siloxane oligomers and the creation of hydrophobic surface. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2007 254 452–458.

- Bogdanowicz, K.A.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Maciejewski, H.; Nowicki, M.; Przybyl, W.; Plebankiewicz, I.; Iwan, A. Siloxane resins as hydrophobic self-cleaning layers for silicon and dye-sensitized solar cells: material and application aspects. RSC Adv., 2022, 12, 19154−19170. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Lin, C.-I.; Lee, Y.-D. Synthesis and characterization of (AB)n-type poly(L-lactide) poly(dimethyl siloxane) multiblock copolymer and the effect of its macrodiol composition on urethane formation. Eur. Polym. J., 2009, 45, 2455–2466.

- Anisimov, A.A.; Kuvandykova, A.E.; Buzin, I. A.; Muzafarov, M.A. Synthesis of siloxane analogue of polyethylene terephthalate. Mendeleev Commun., 2019, 29, 461–462. [CrossRef]

- Racles, C.; Cozan, V.; Bele, A.; Dascalu, M. Polar silicones: structure-dielectric properties relationship. Designed Monomers and Polymers, 2016, 6, 496–507. [CrossRef]

- Schauser, S.N.; Grzetic, J.D; Tabassum, T.; Kliegle, A.G.; Le L.M.; Susca, M.E.; Antoine, S.; Keller, J.T.; Delaney, T.K.; Han, S.; Seshadri, R.; Fredrickson, H.G.; Segalman, A.R. The Role of Backbone Polarity on Aggregation and Conduction of Ions in Polymer Electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 15, 7055–7065. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Osby, J; Siloxane modification of polycarbonate for superior flow and impact toughness. Polymer, 2010, 9, 1990−1999. [CrossRef]

- Woehrle, H.G.; Warner, G.M.; Hutchison, E.J. Molecular-Level Control of Feature Separation in One-Dimensional Nanostructure Assemblies Formed by Biomolecular Nanolithography. Langmuir, 2004, 14, 5982−5988. [CrossRef]

- Frye, L.C.; Salinger, M.R.; Fearon, G.F.W.; Klosowski, M.J.; DeYoung, T. Reactions of organolithium reagents with siloxane substrates. J. Org. Chem., 1970, 5, 1308−1314. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kigure, M.; Okawa, R.; Takeda, N.; Unno, M. Synthesis and characterization of tetrathiol-substituted double-decker or ladder silsesquioxane nano-cores, Dalton Trans., 2021, 50, 3473−3478.

- Xue, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, S. Facile, versatile and efficient synthesis of functional polysiloxanes via thiol–ene chemistry. Eur. Polym. J., 2013, 49, 1050–1056. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Damiron, D.; Dkhil, B.S.; Drockenmuller, E.; Restagno, F.; Leger, L. Synthesis of Well-Defined Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Telechelics Having Nitrobenzoxadiazole Fluorescent Chain-Ends via Thiol-Ene Coupling. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem., 2012, 50, 1827–1833.

- Fox, W.H.; Taylor, W.A.; Zisman, A.W. Ind. Eng. Chem., 1947, 39, 1401−1409.

- Pawlenko, S. Organosilicon Chemistry, Walter de Gruyter, New York, USA, 1986; pp. 13−16.

- Yamaya, M. Silocone Taizen, The Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun, LTD., Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 8−11.

- Tao, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, B. The influence of molecular weight of siloxane macromere on phase separation morphology, oxygen permeability, and mechanical properties in multicomponent silicone hydrogels. Colloid Polym. Sci., 2017, 295, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E.M.; Porter, R.S. Trans. Soc. Rheol. 1975, 19, 493– 508.

- Gordon, V.G.; Schmidt, G.R.; Quintero, M.; Benton, J.N.; Cosgrove, T.; Krukonis, J.V.; Williams, K.; Wetmore, M.P. Impact of Polymer Molecular Weight on the Dynamics of Poly(dimethylsiloxane)−Polysilicate Nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 10132–10142. [CrossRef]

- Kitazaki, Y.; Hata, T. Journal of the Adhesion Society of Japan, 1972, 8, 131.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).