Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

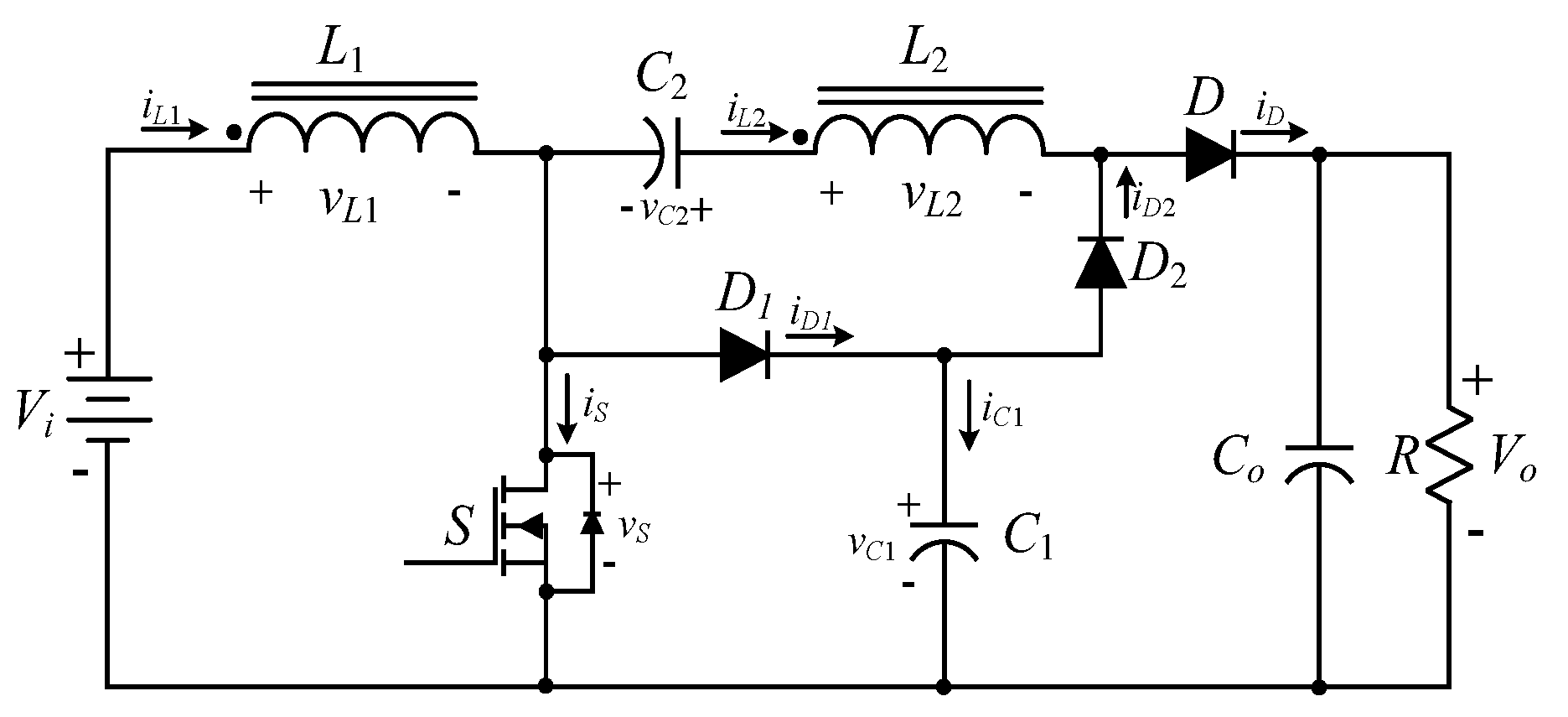

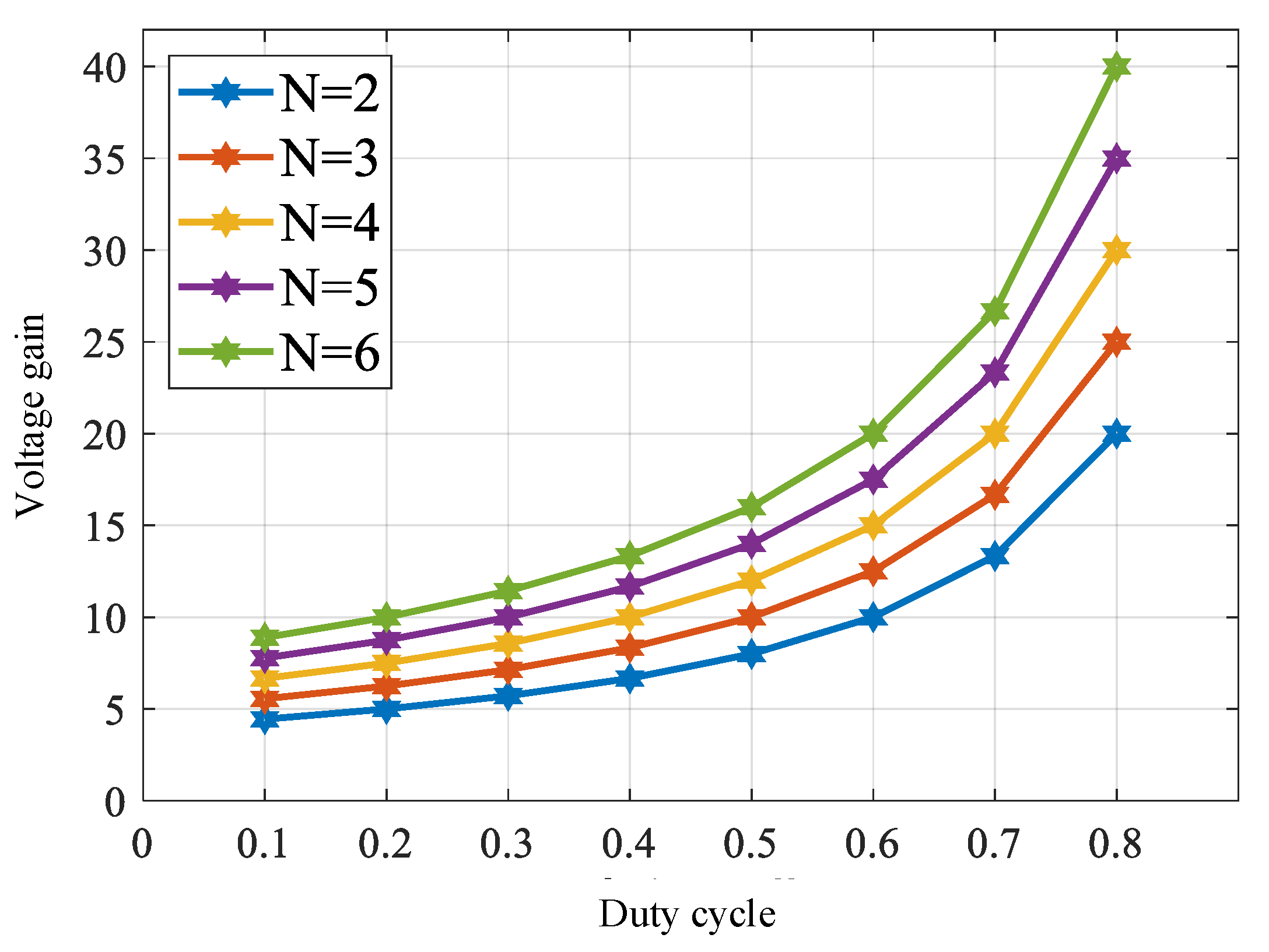

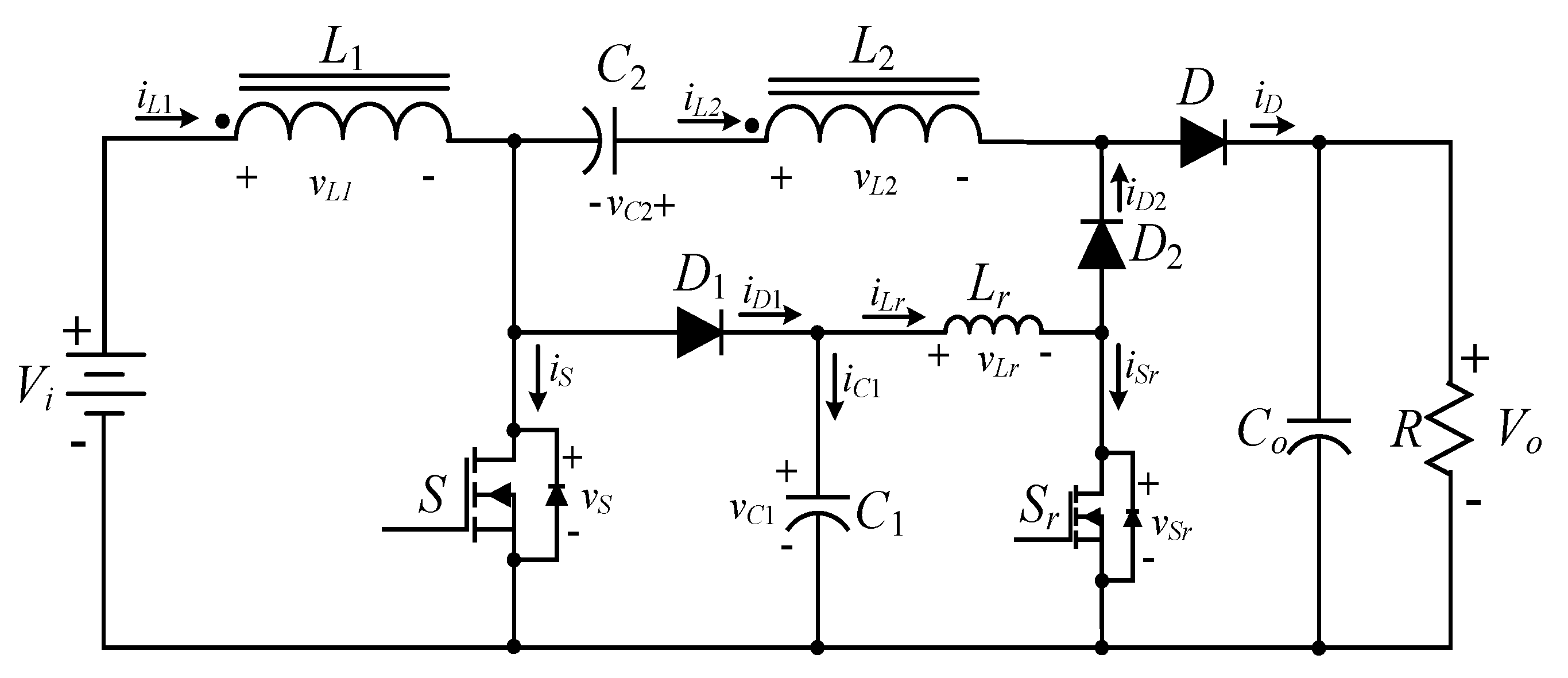

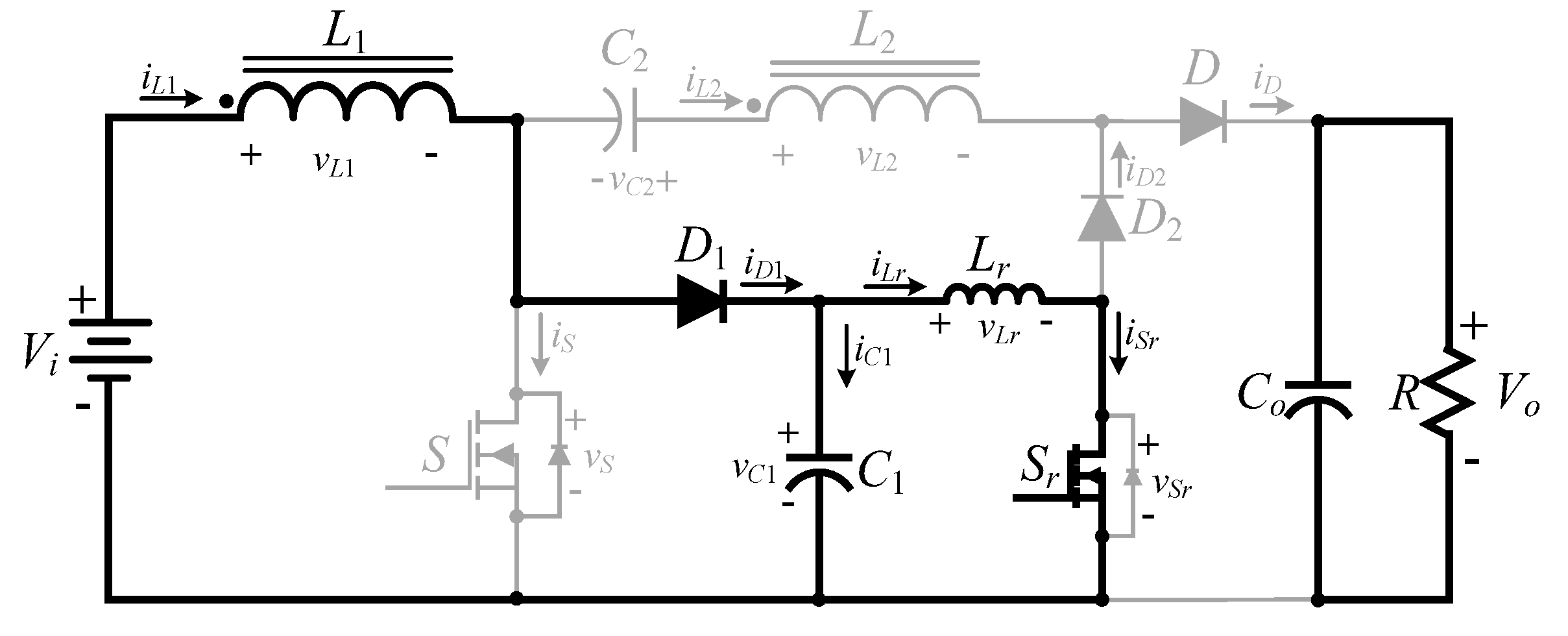

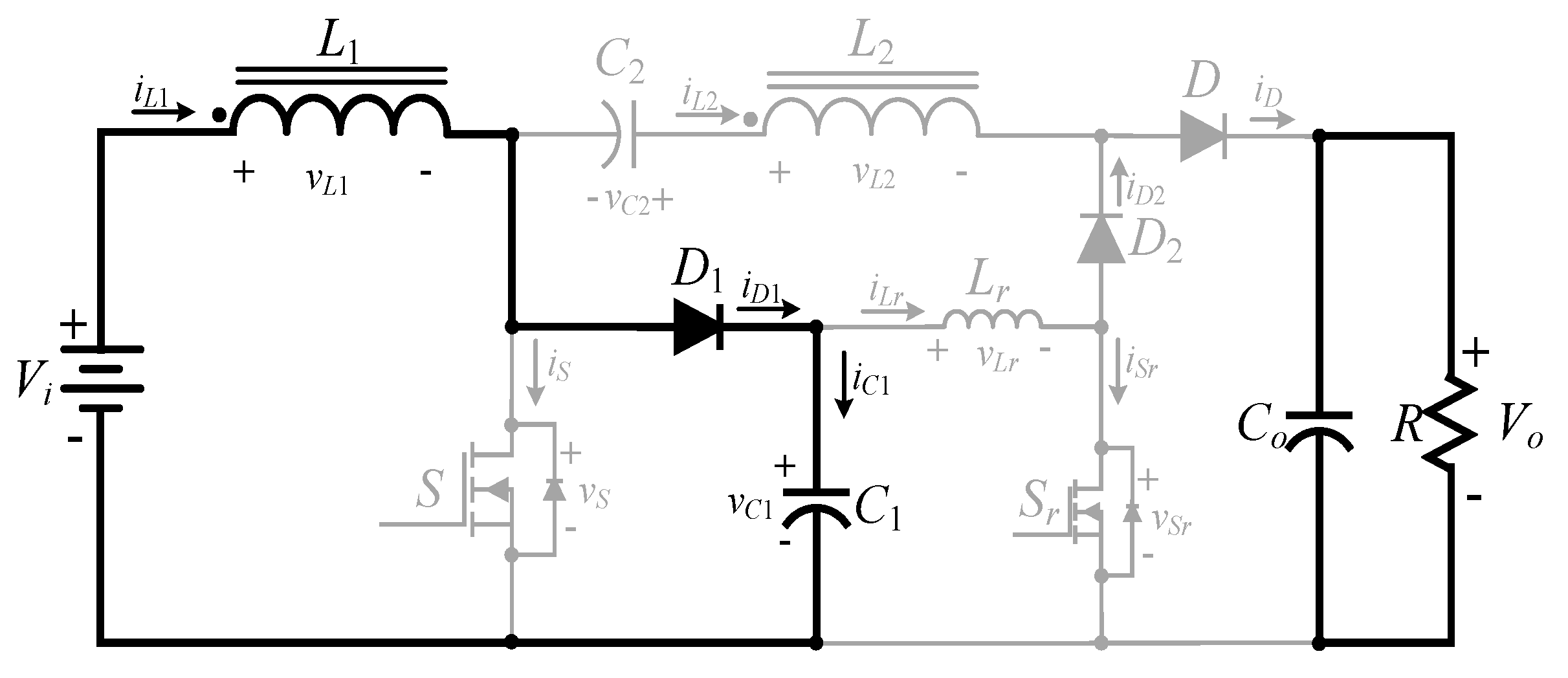

2. The Proposed High Step-Up Converter

2.1. Operating Principle of the High Step-Up Hard Switching Converter

- (1)

- Switch on ()

- (2)

- Switchoff ()

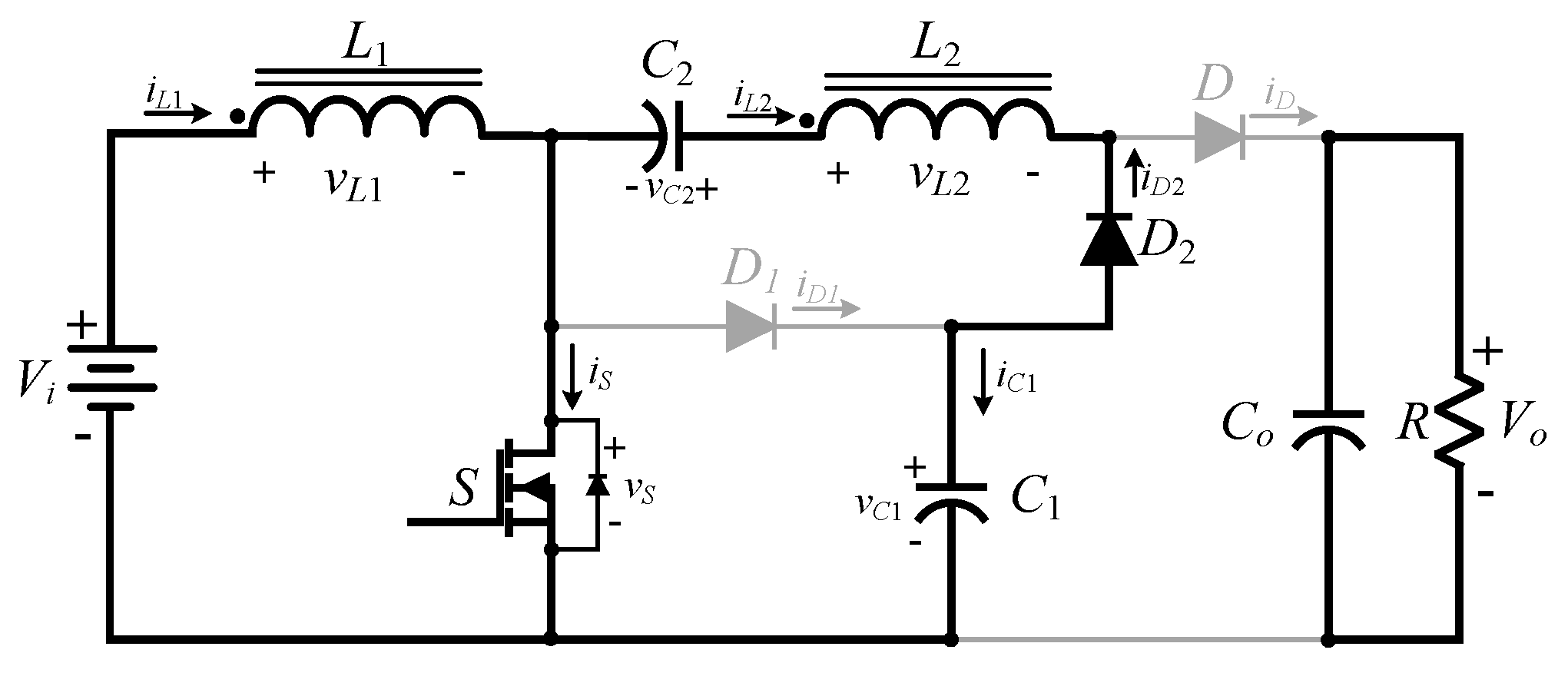

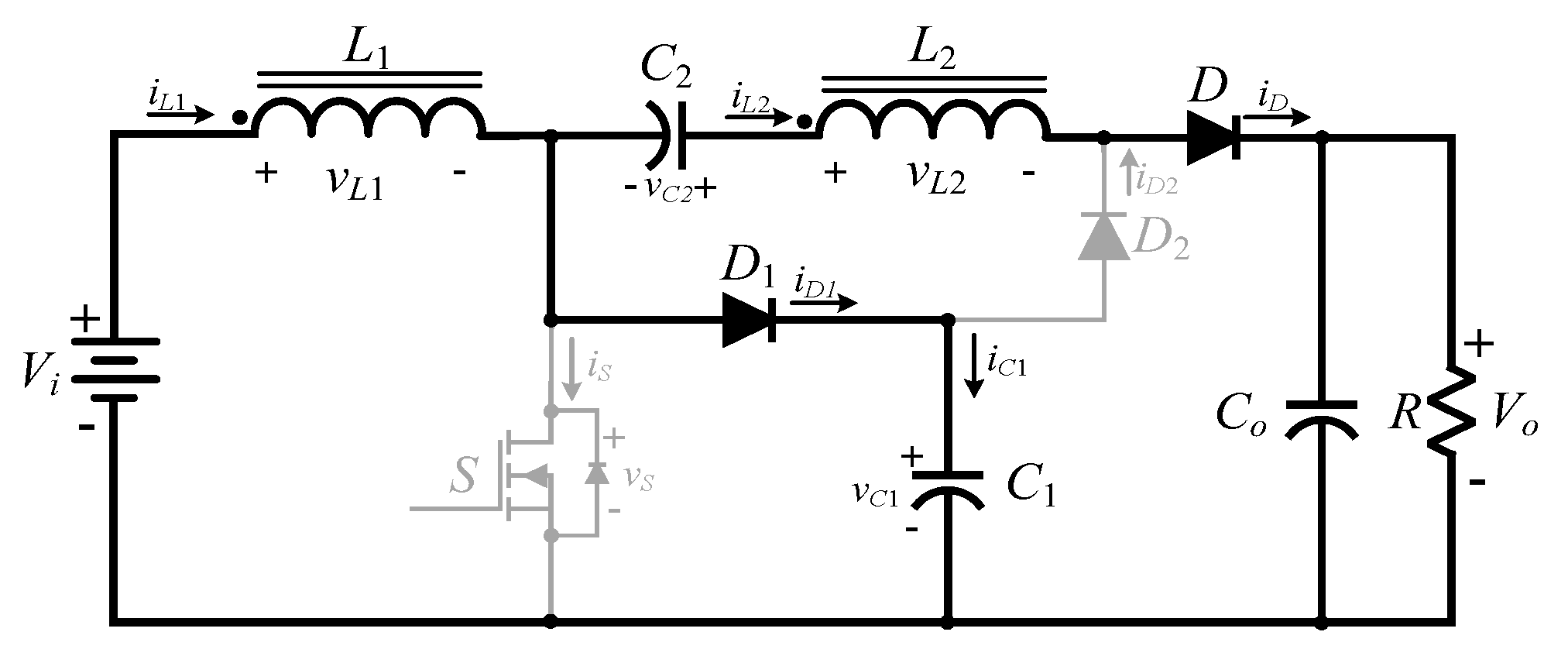

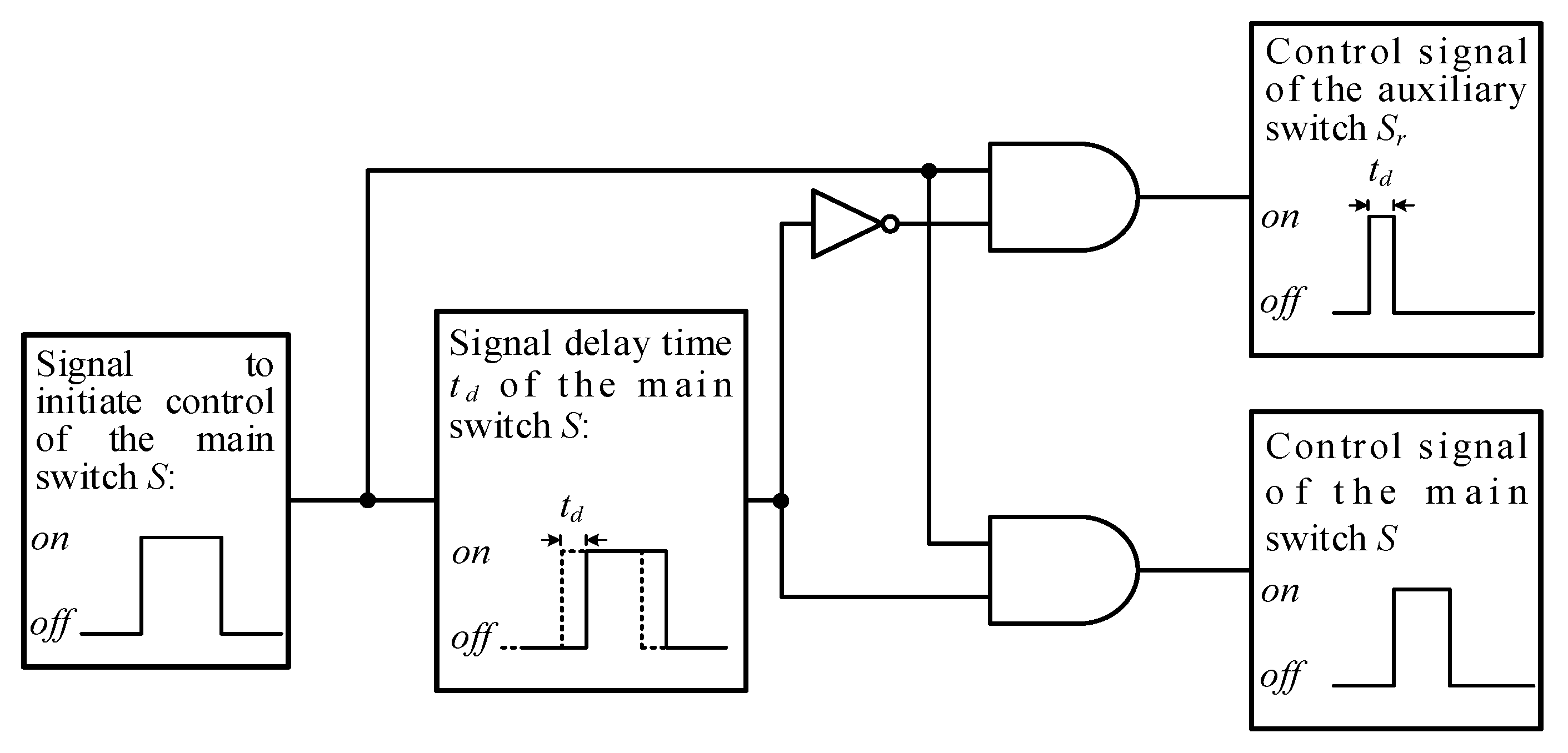

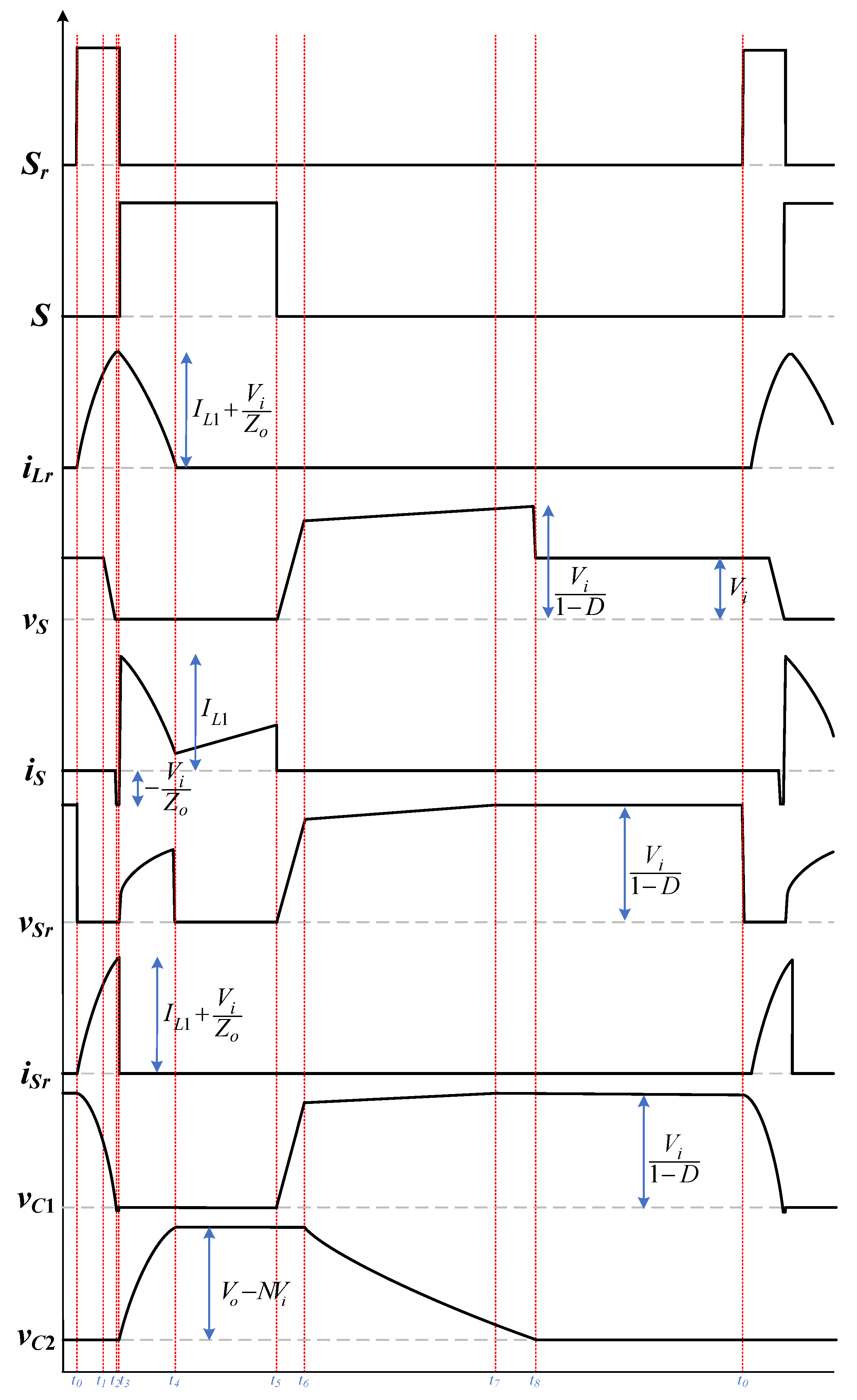

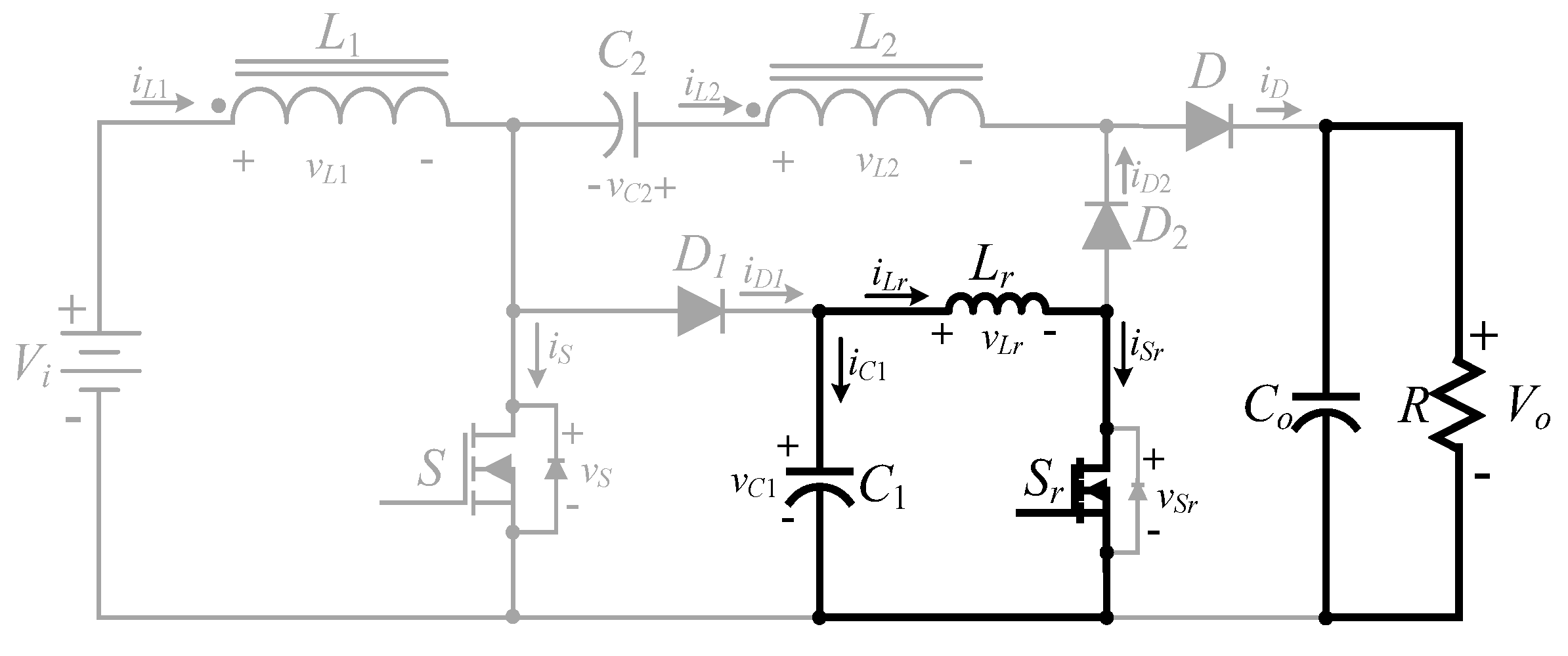

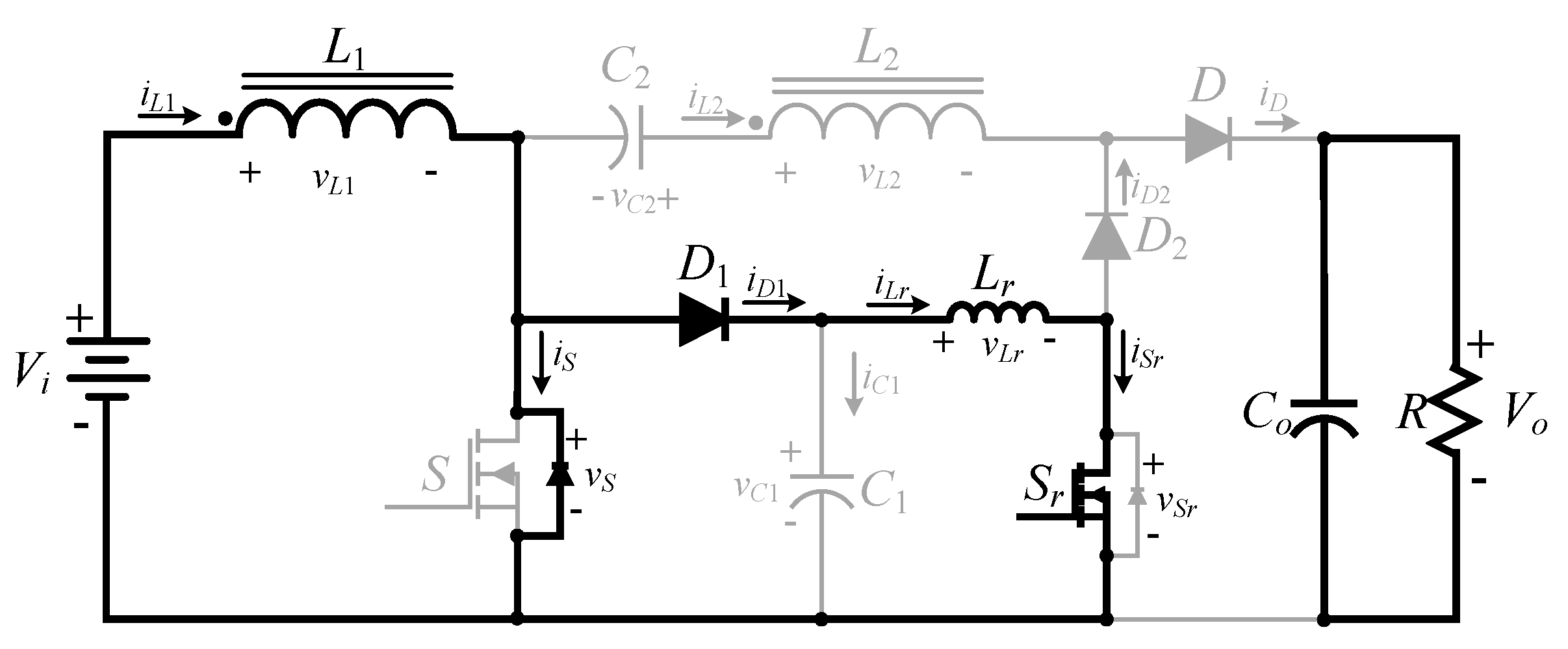

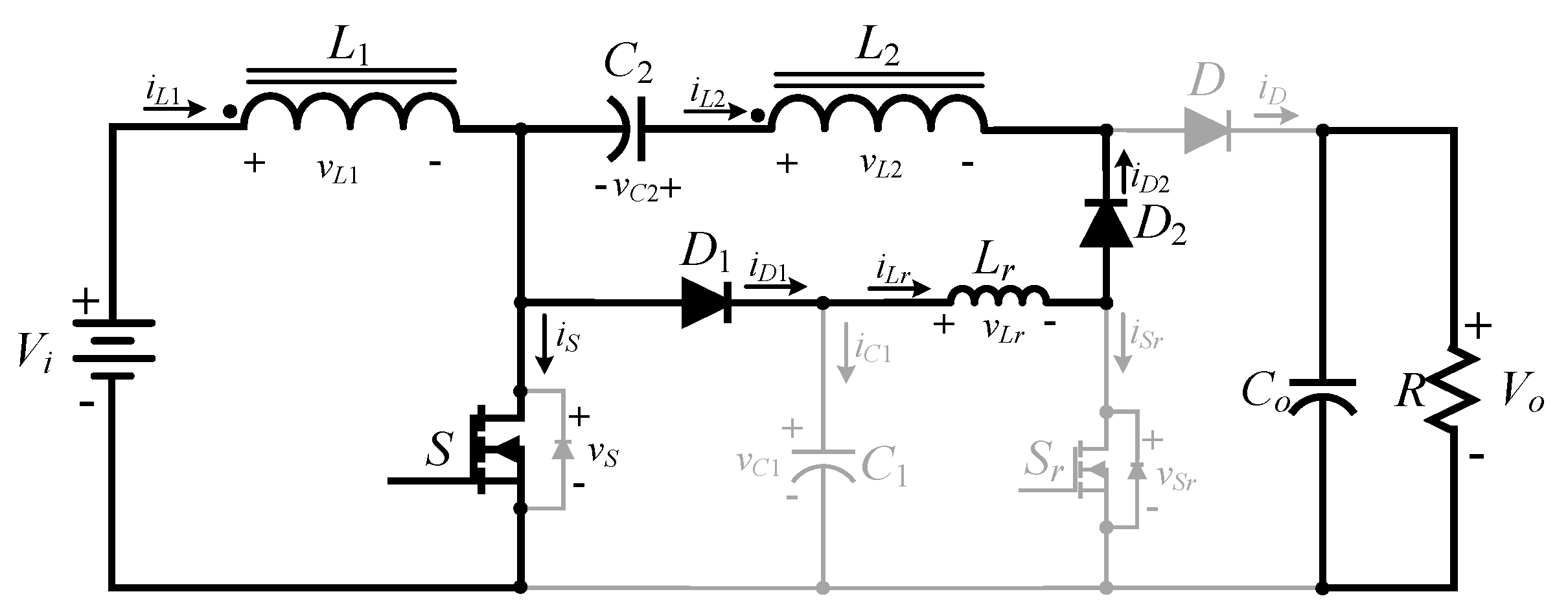

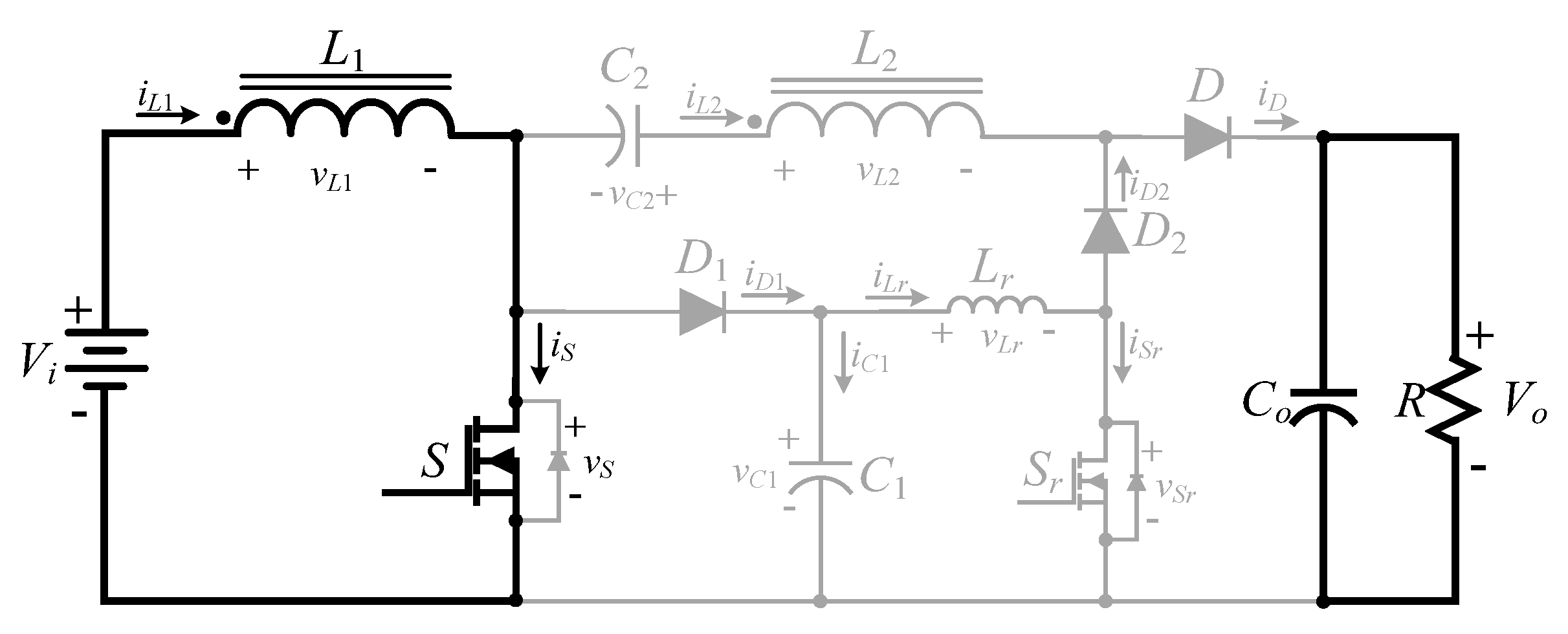

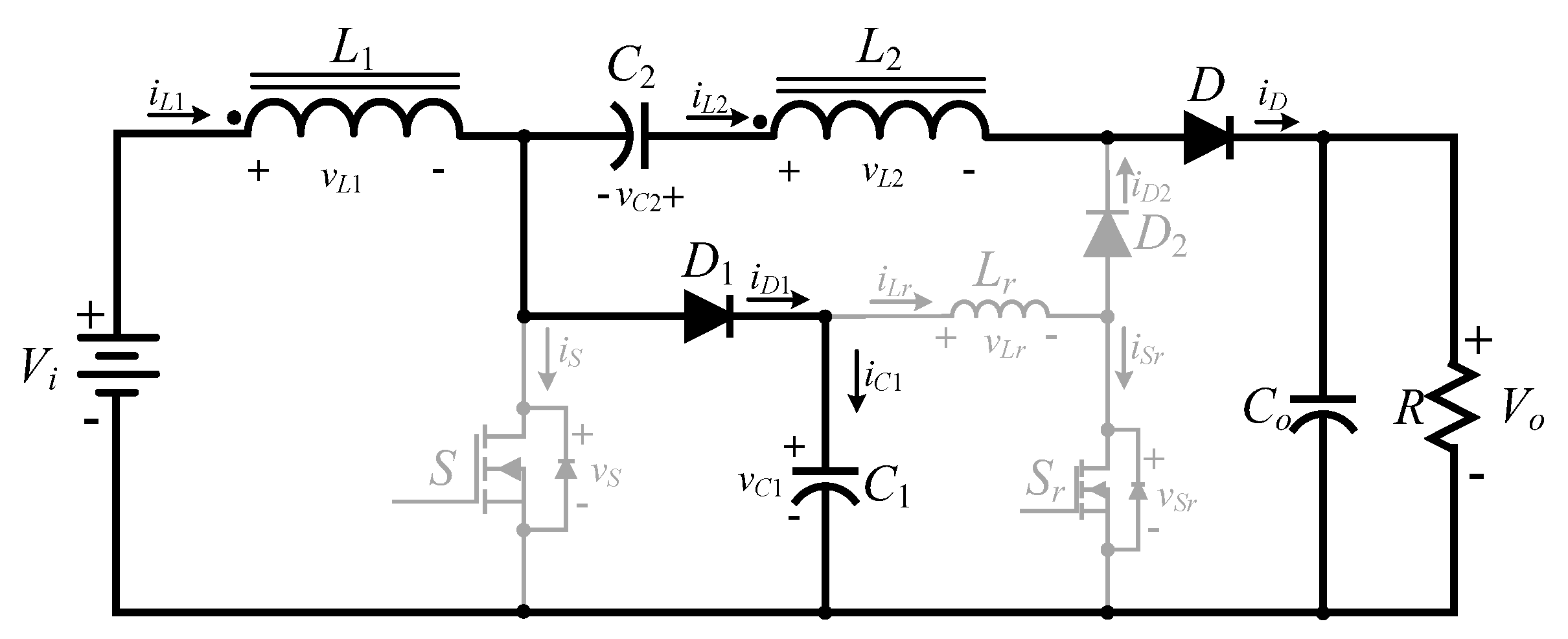

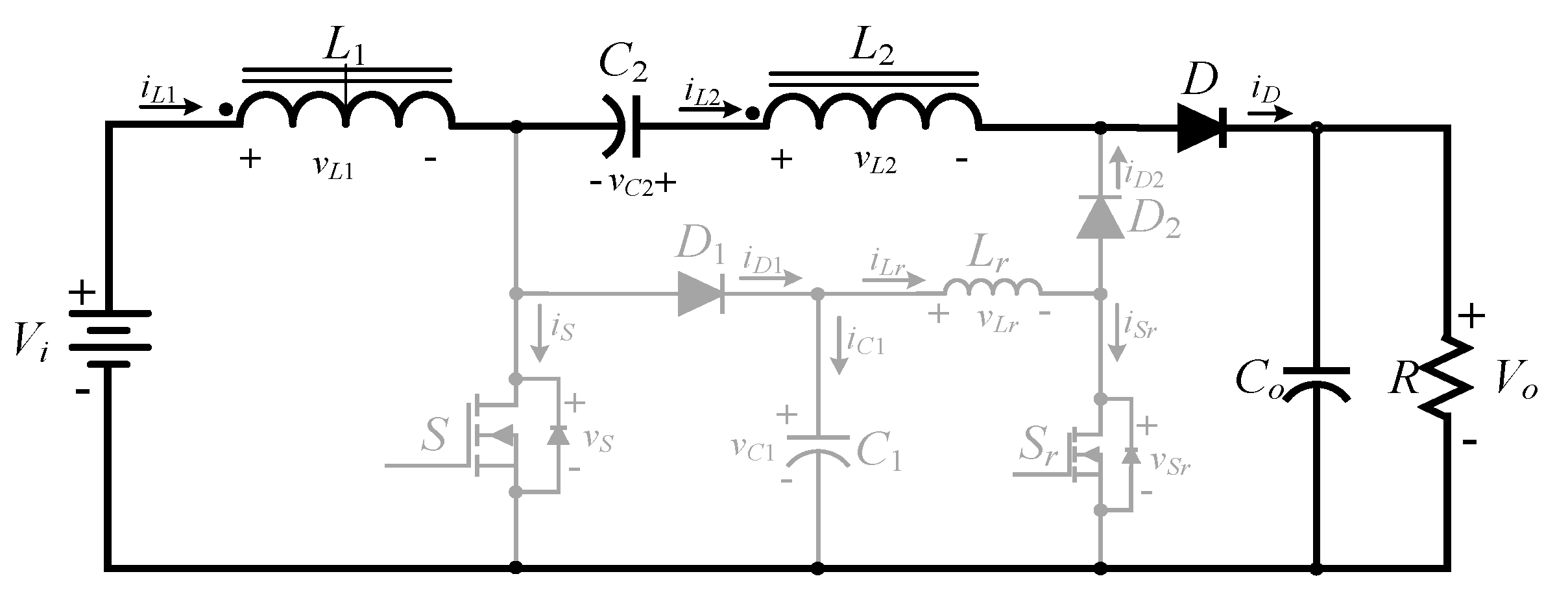

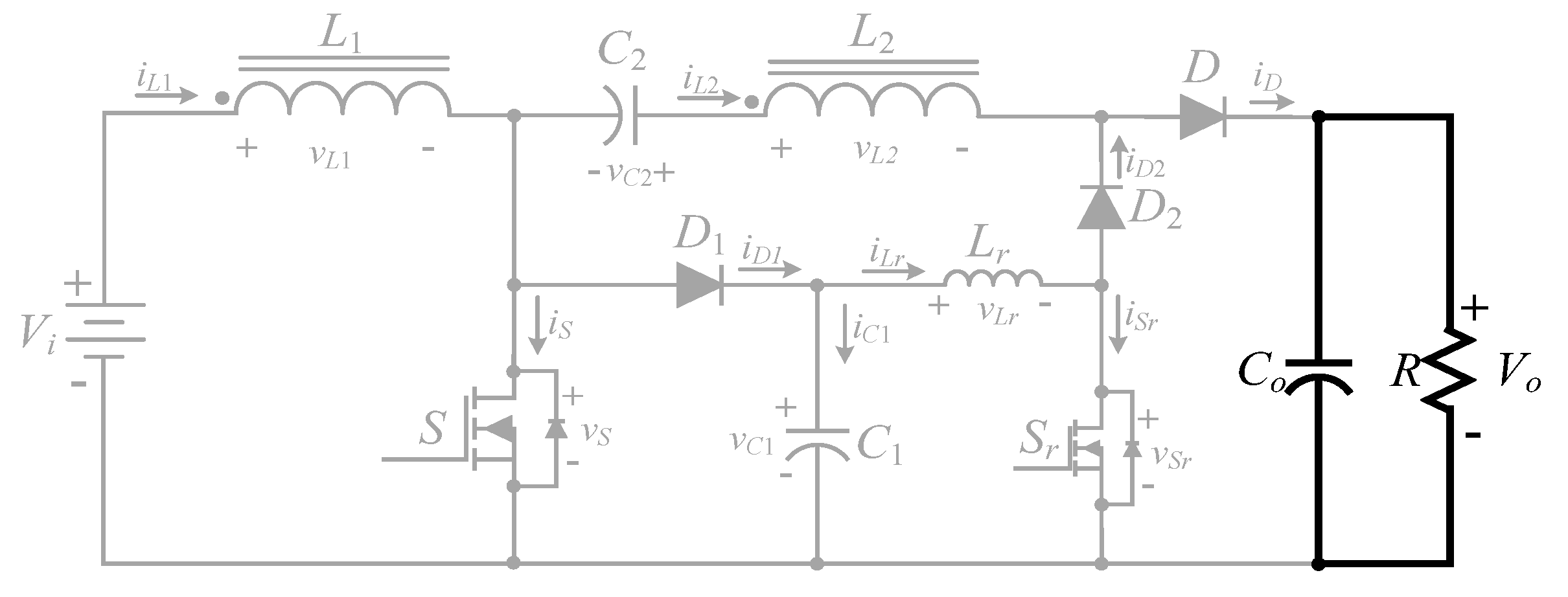

2.2. Operating Principle of the High Step-Up Hard Switching Converter

- (1)

- Mode 1()

- (2)

- Mode2 ()

- (3)

- Mode 3 ()

- (4)

- Mode4 ()

- (5)

- Mode5 ()

- (6)

- Mode6 ()

- (7)

- Mode7 ()

- (8)

- Mode8 ()

- (9)

- Mode9 ()

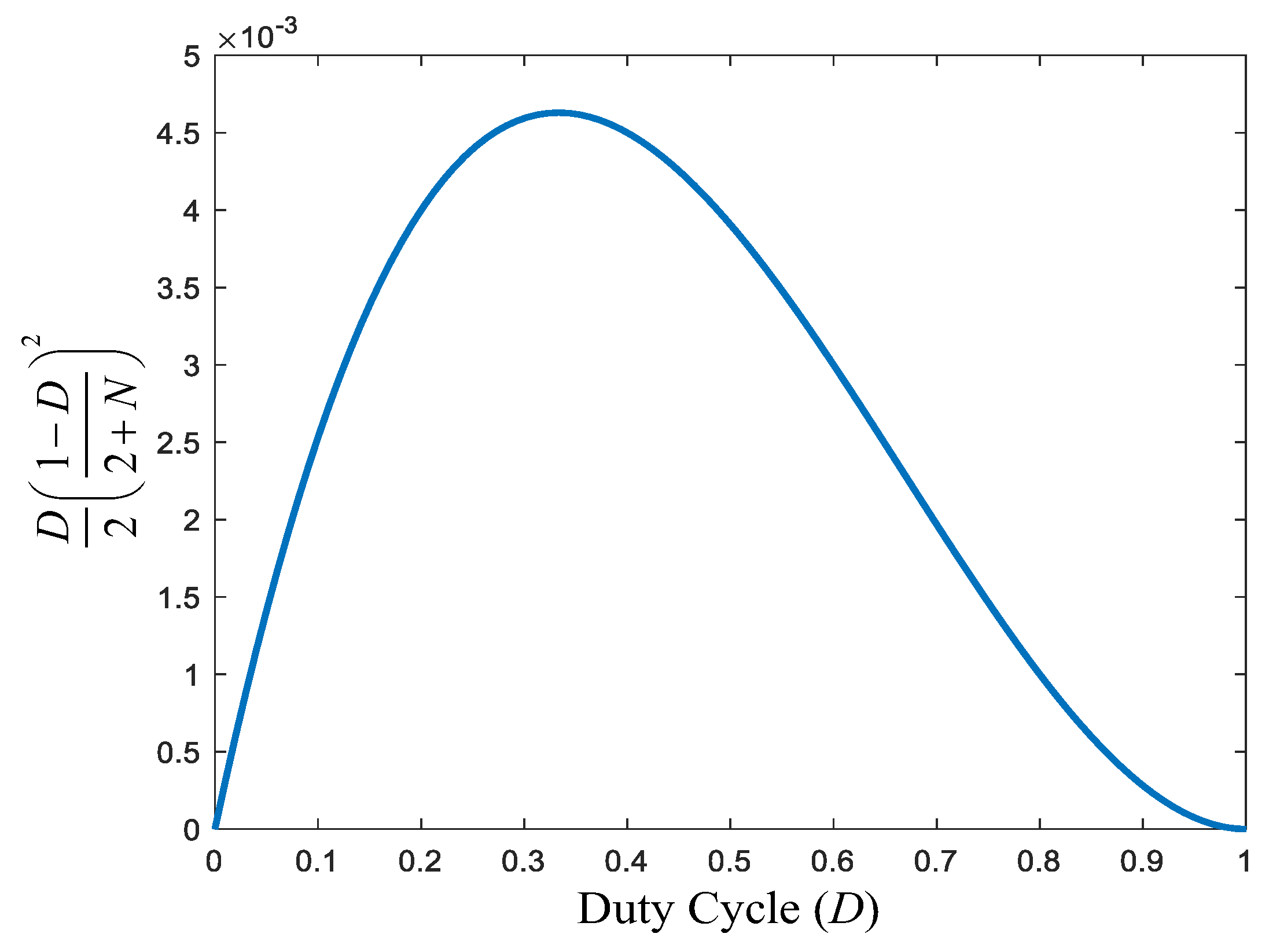

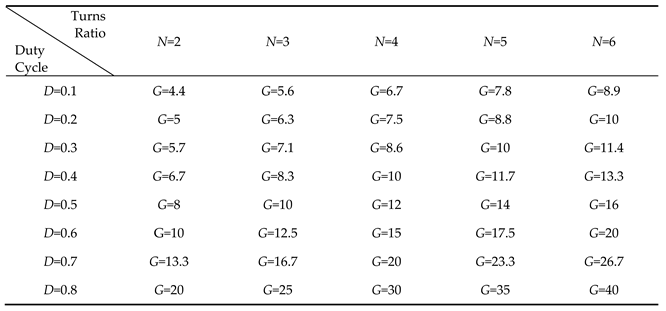

3. Component Design of the Proposed High Step-Up Converter

3.1. Design of Coupled Inductors

3.2. Design of Capacitors and

3.3. Design of Resonant Inductor

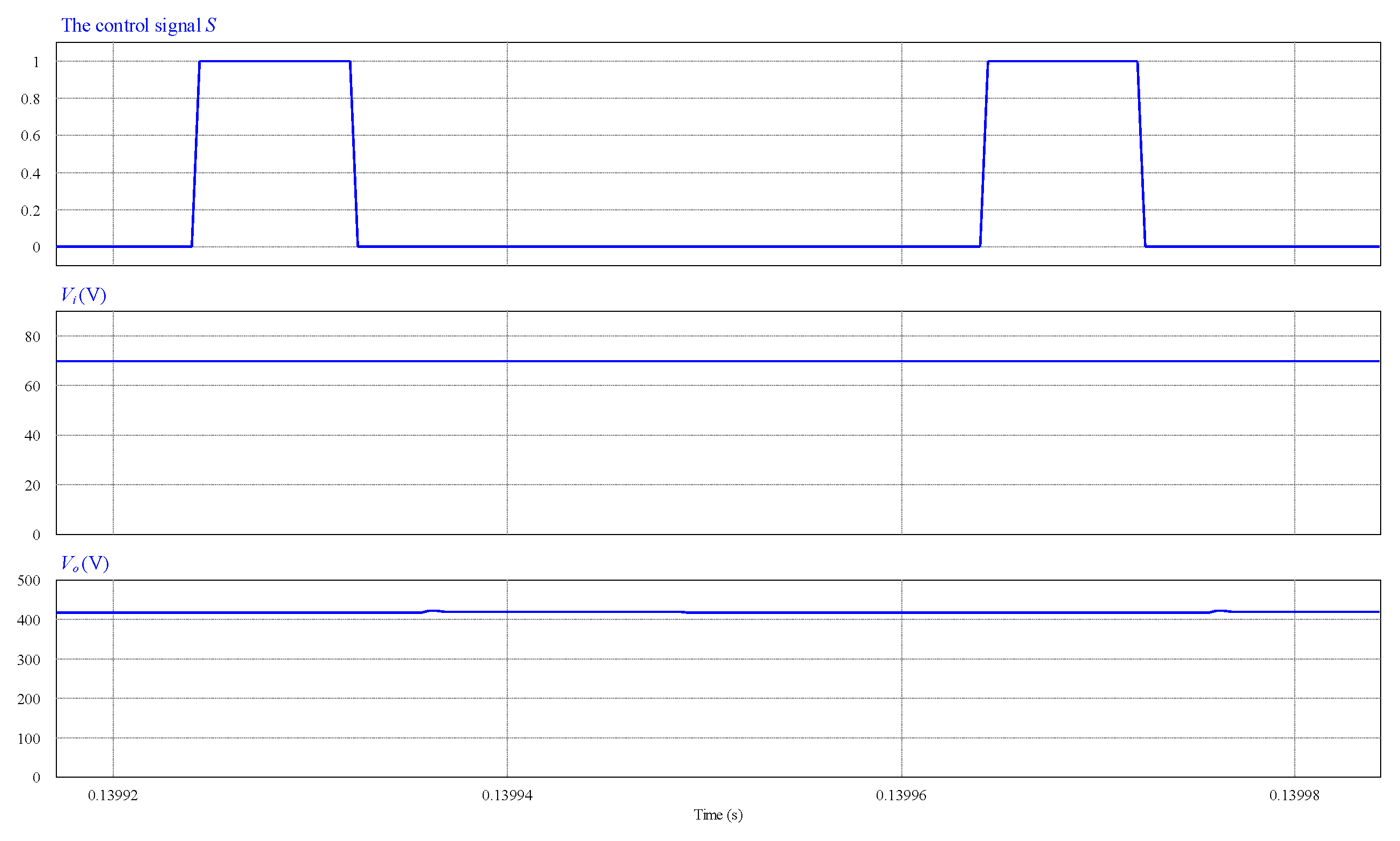

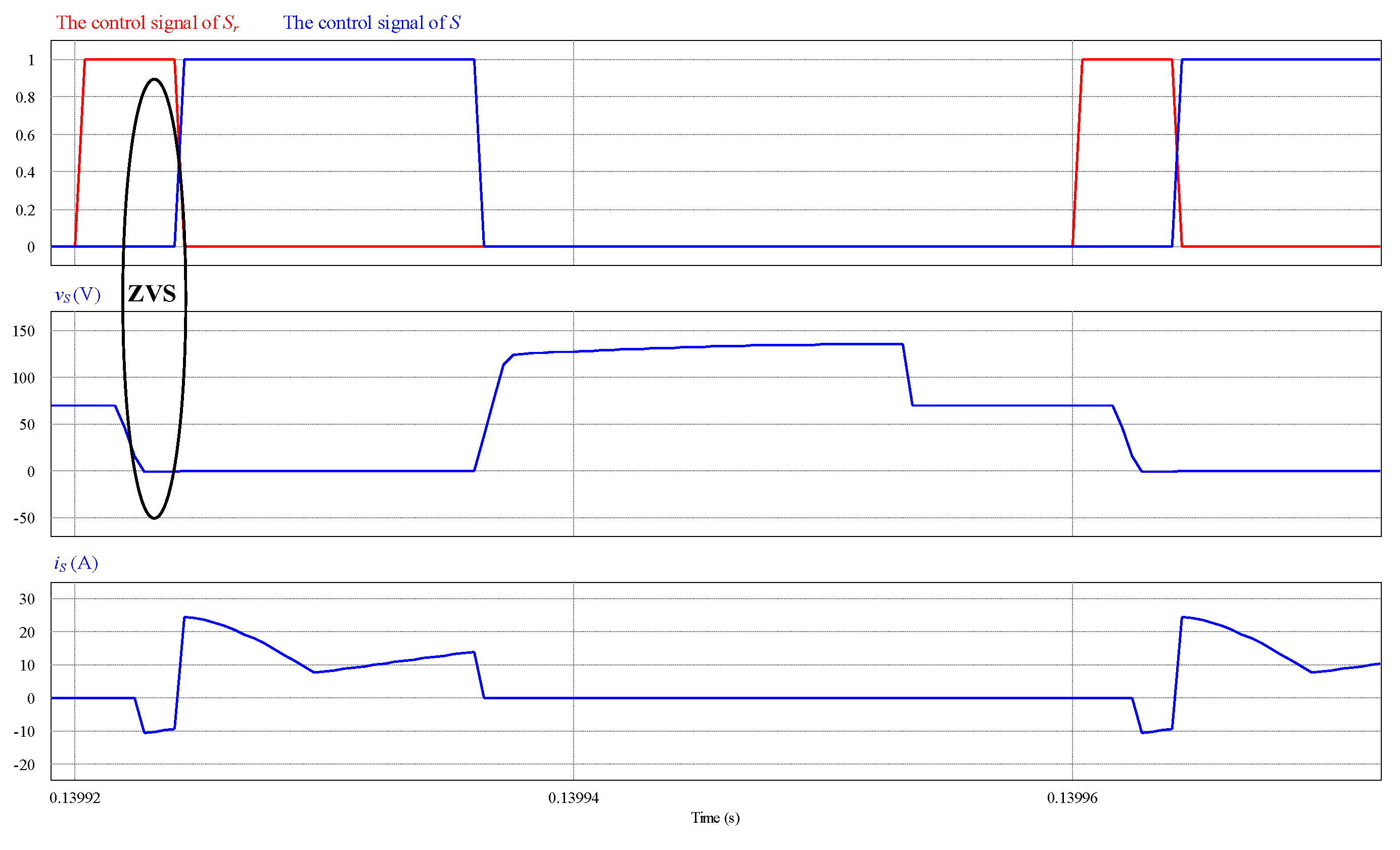

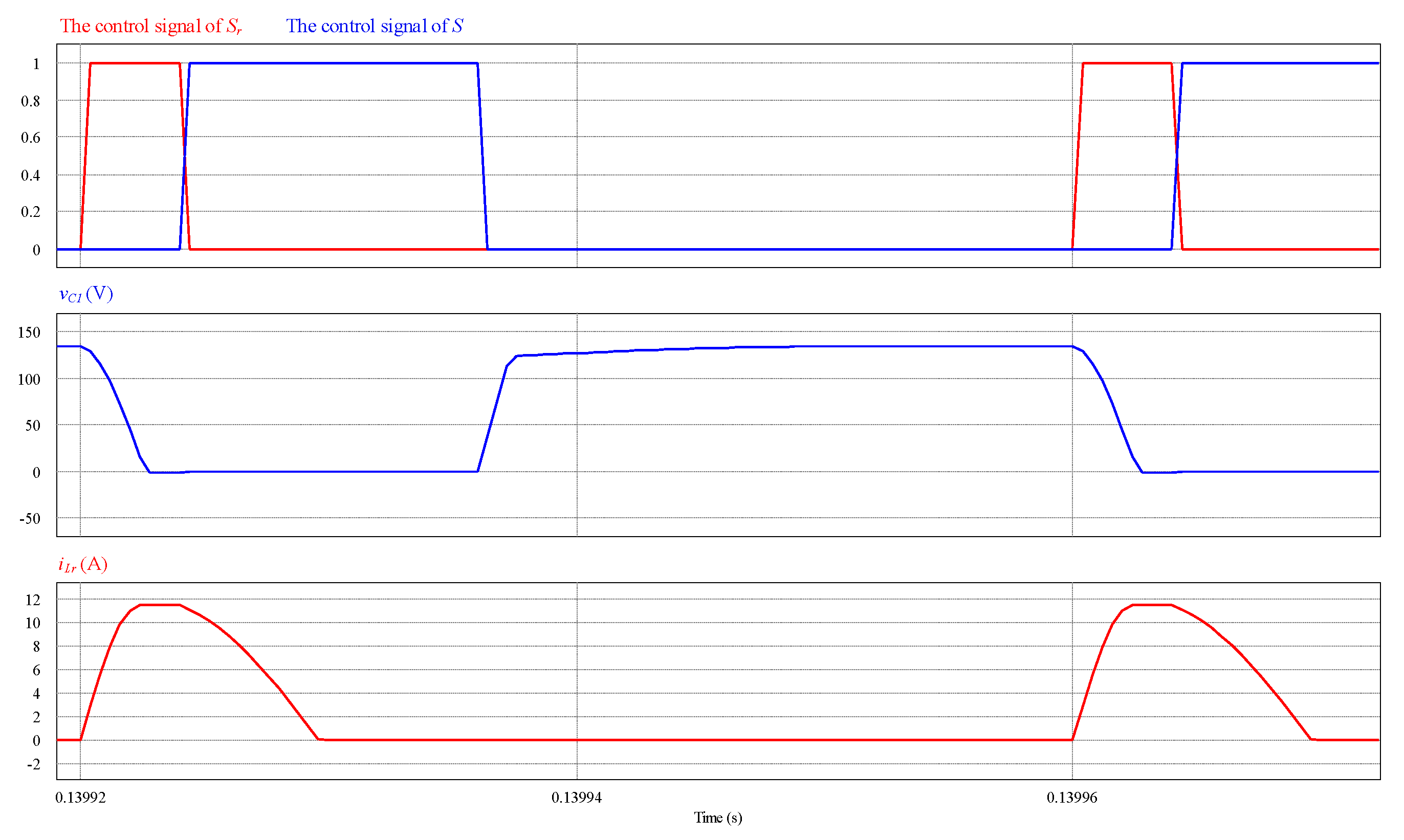

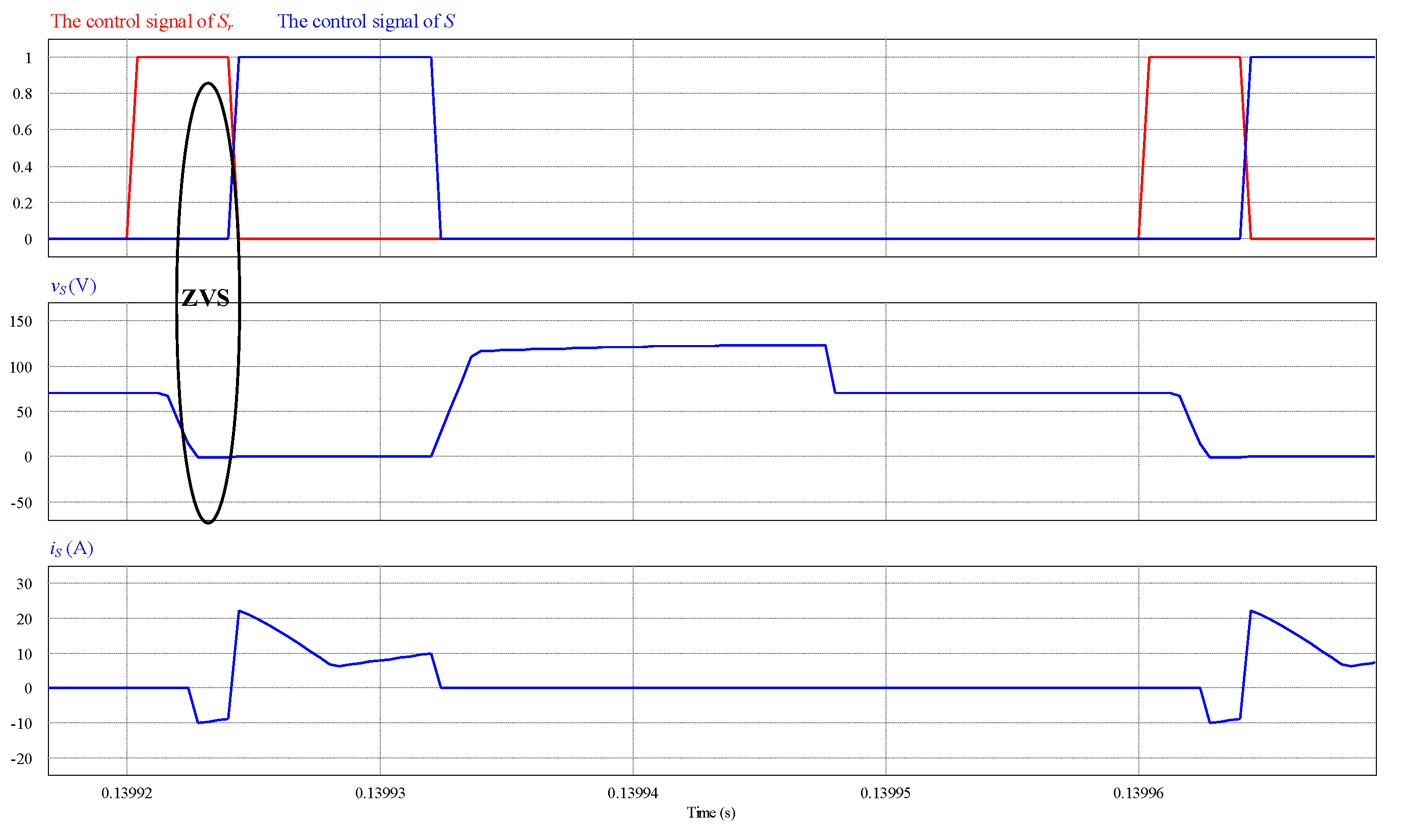

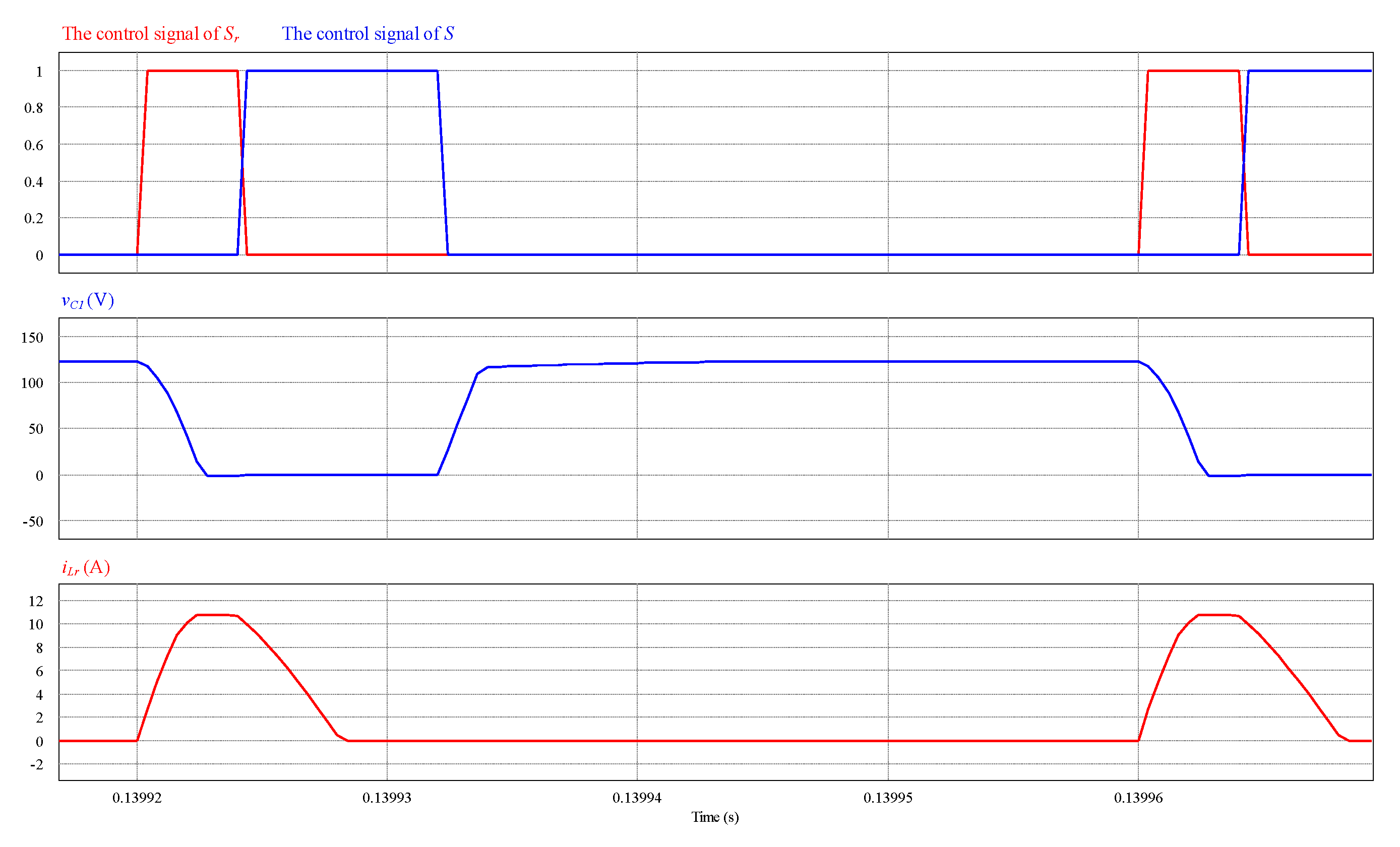

4. Simulation Results

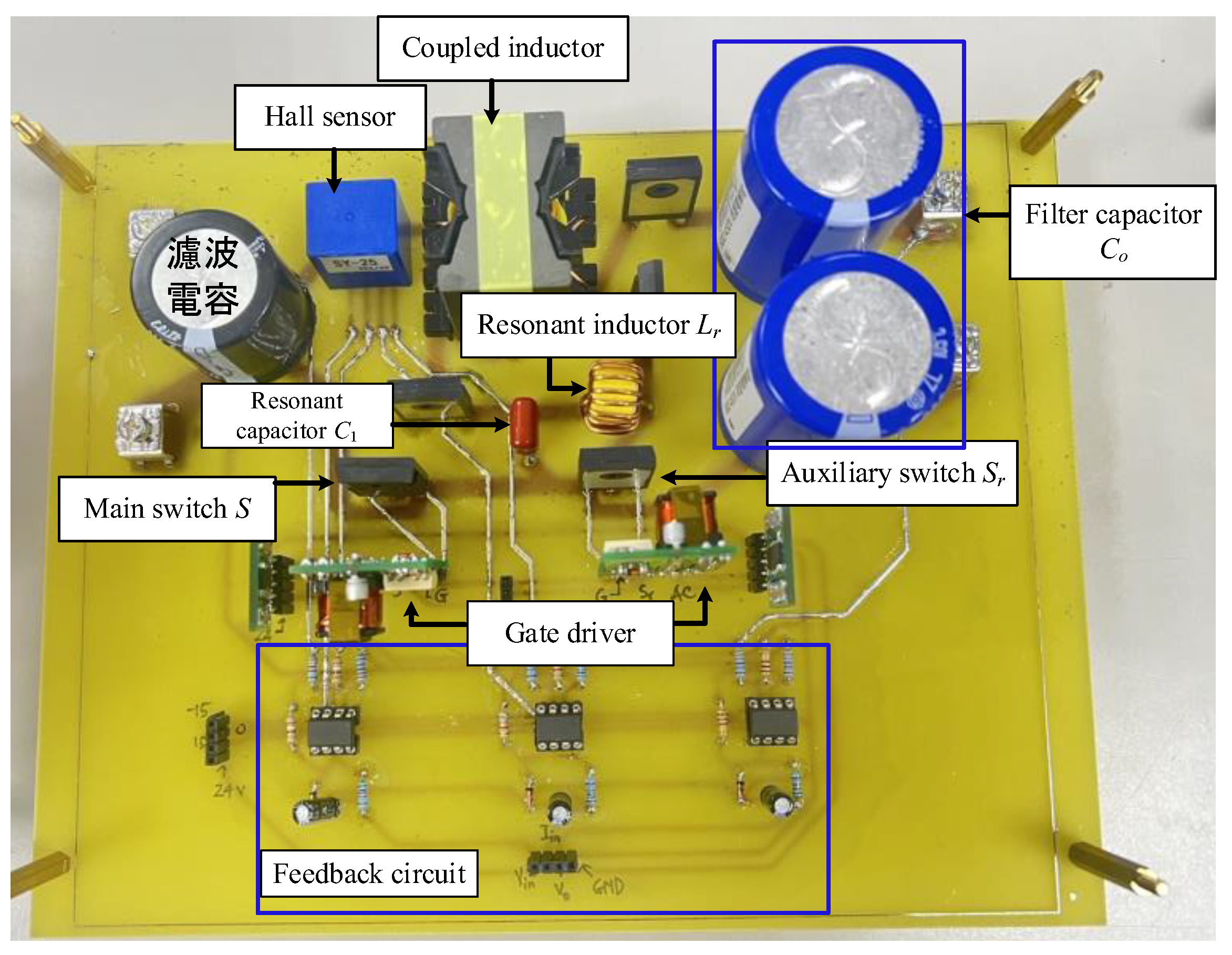

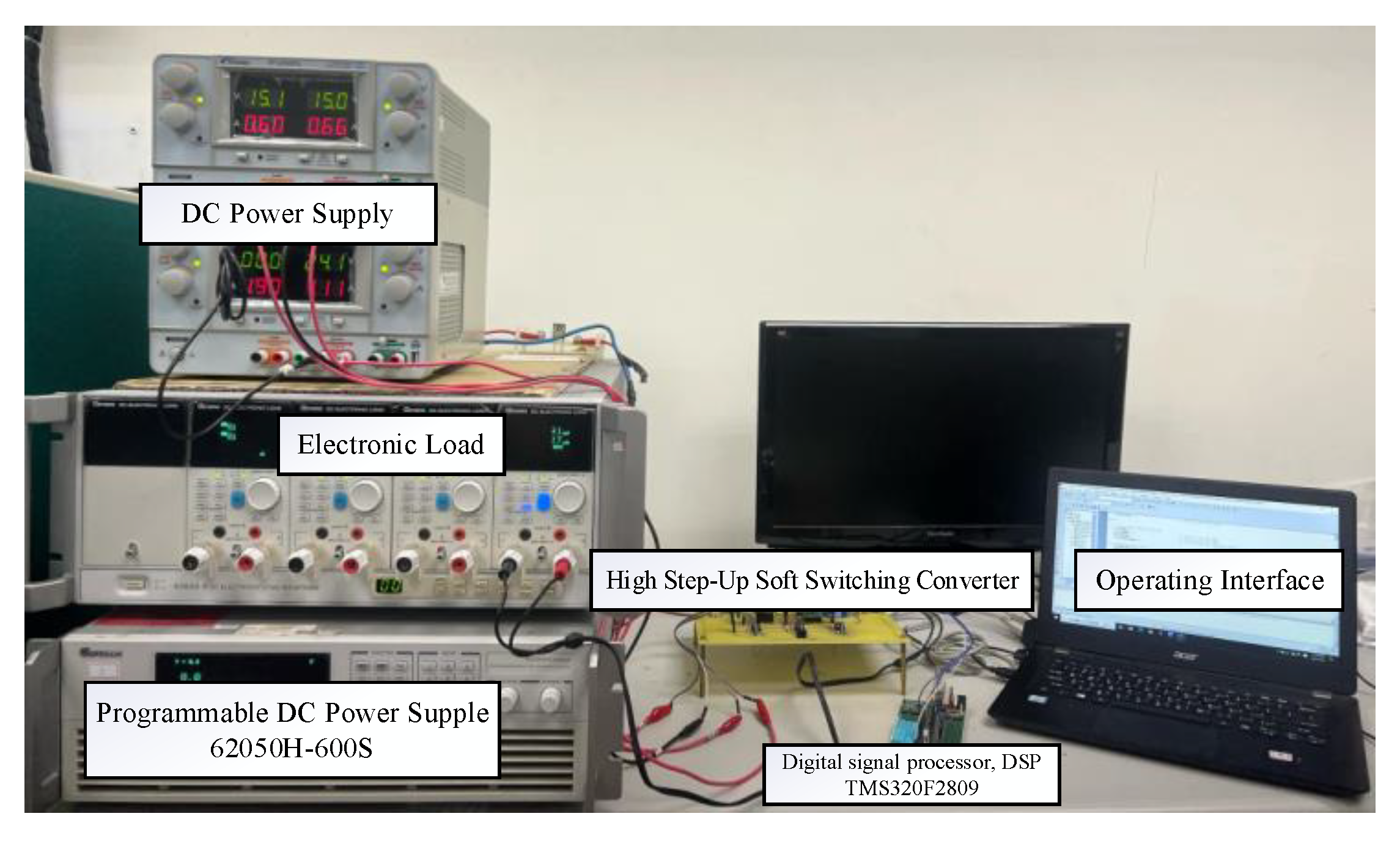

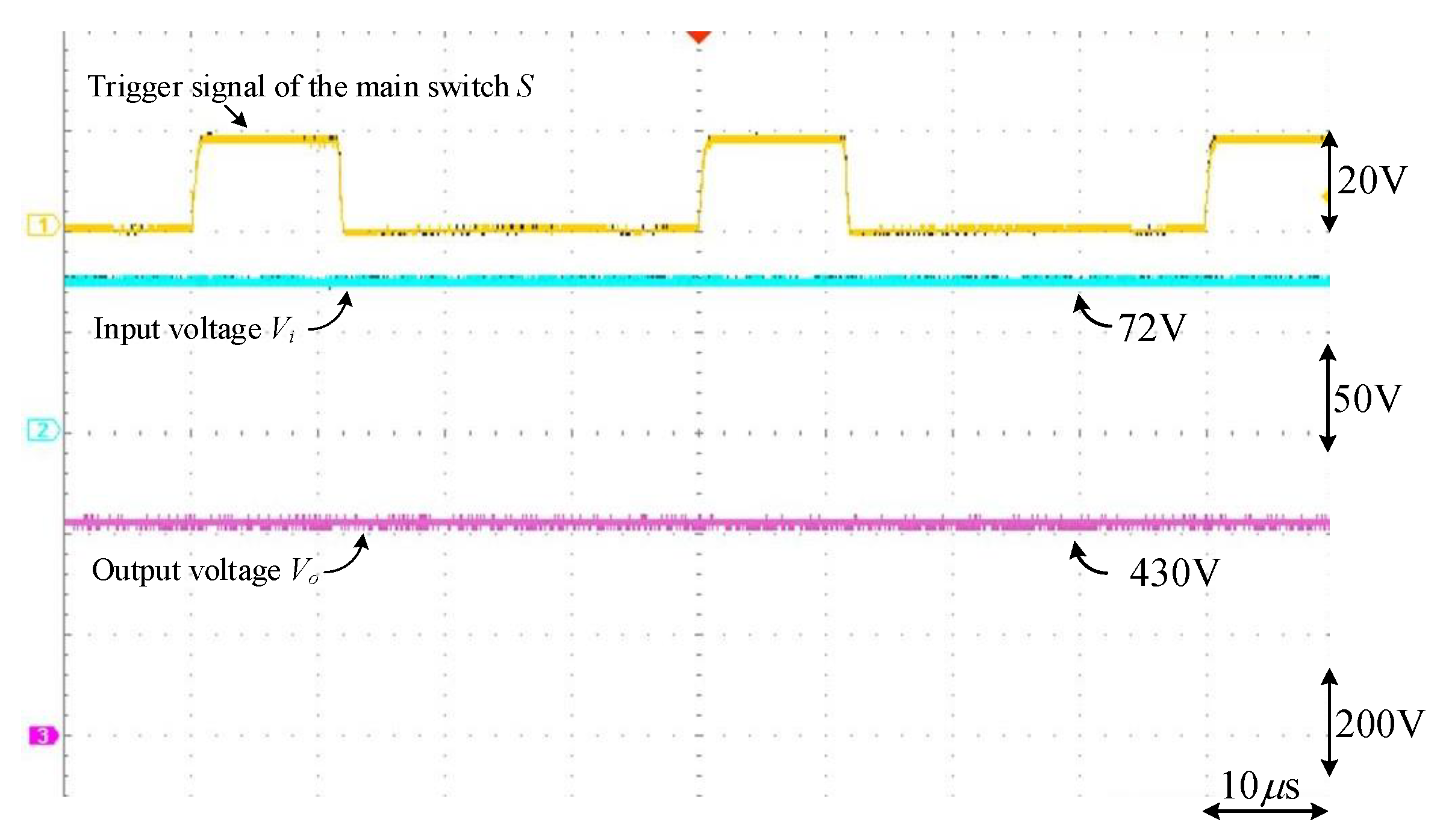

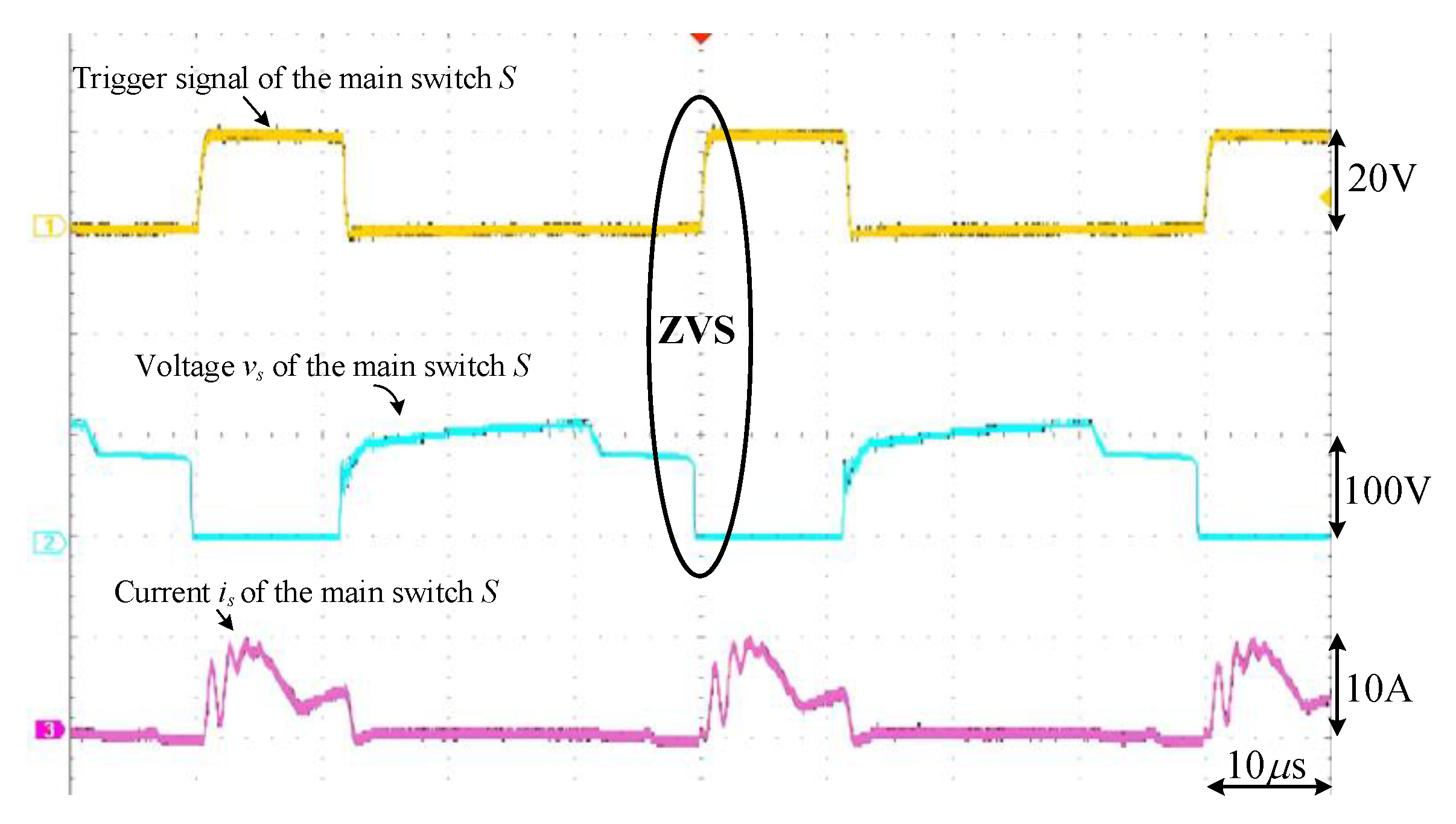

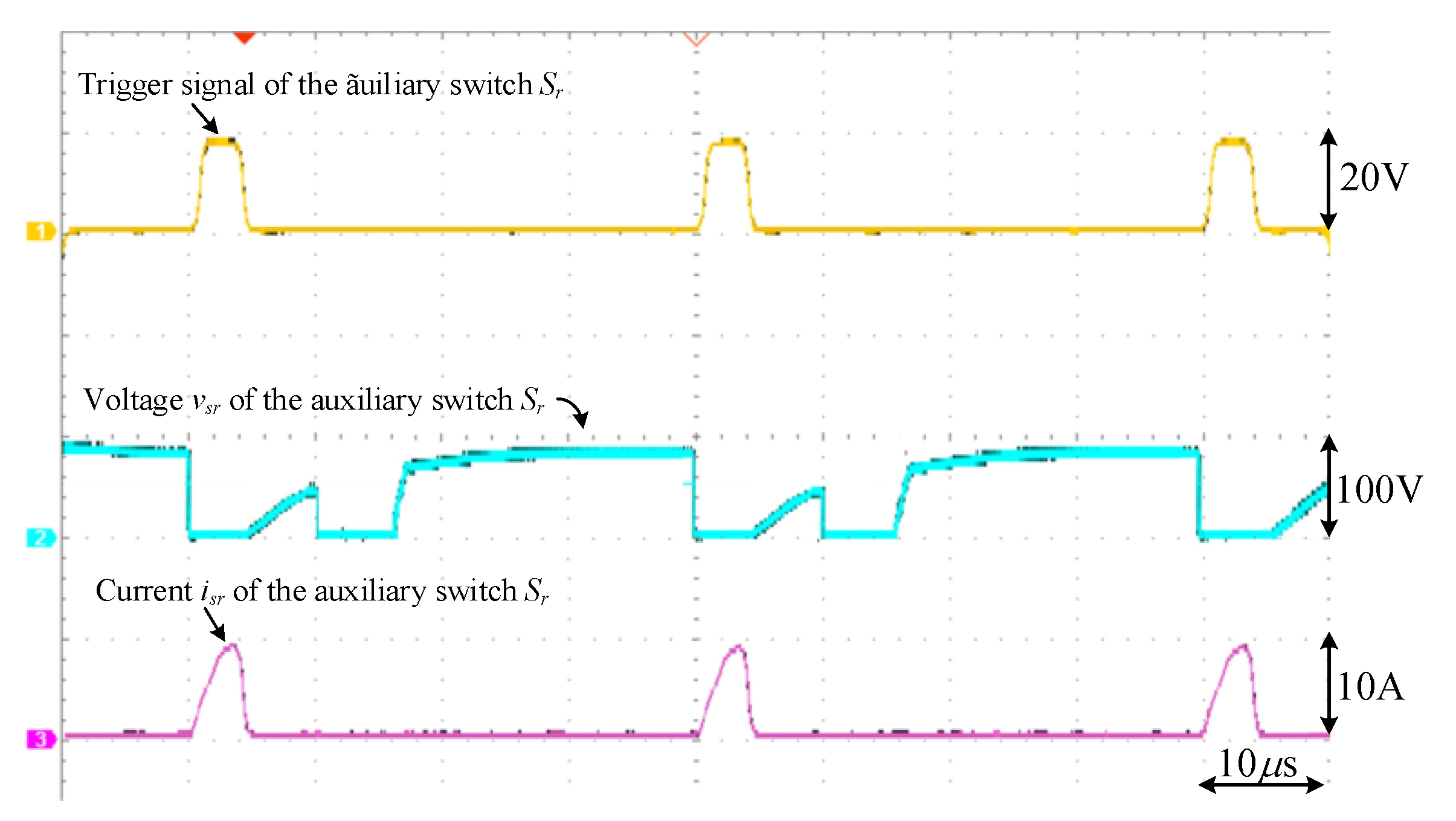

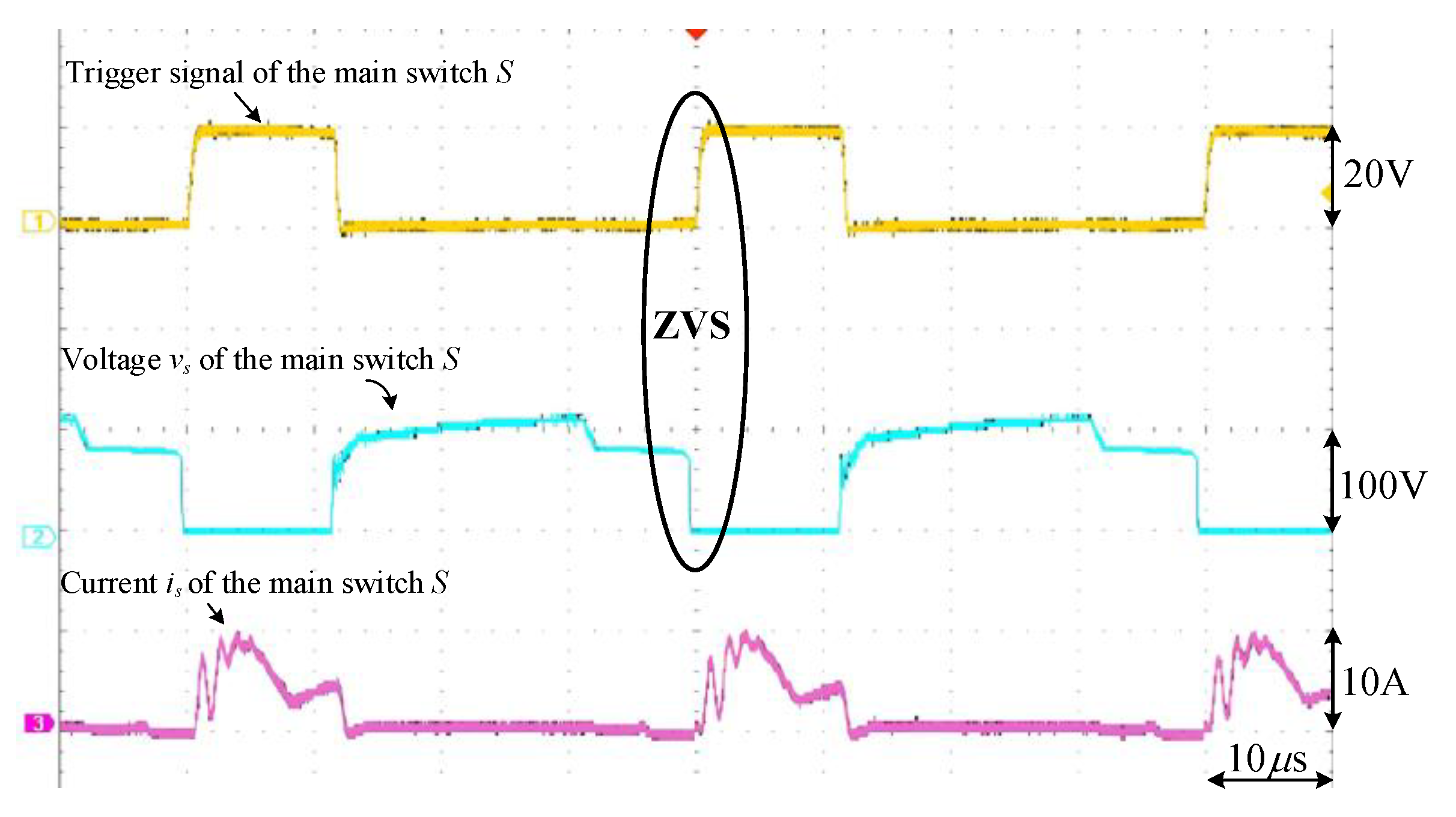

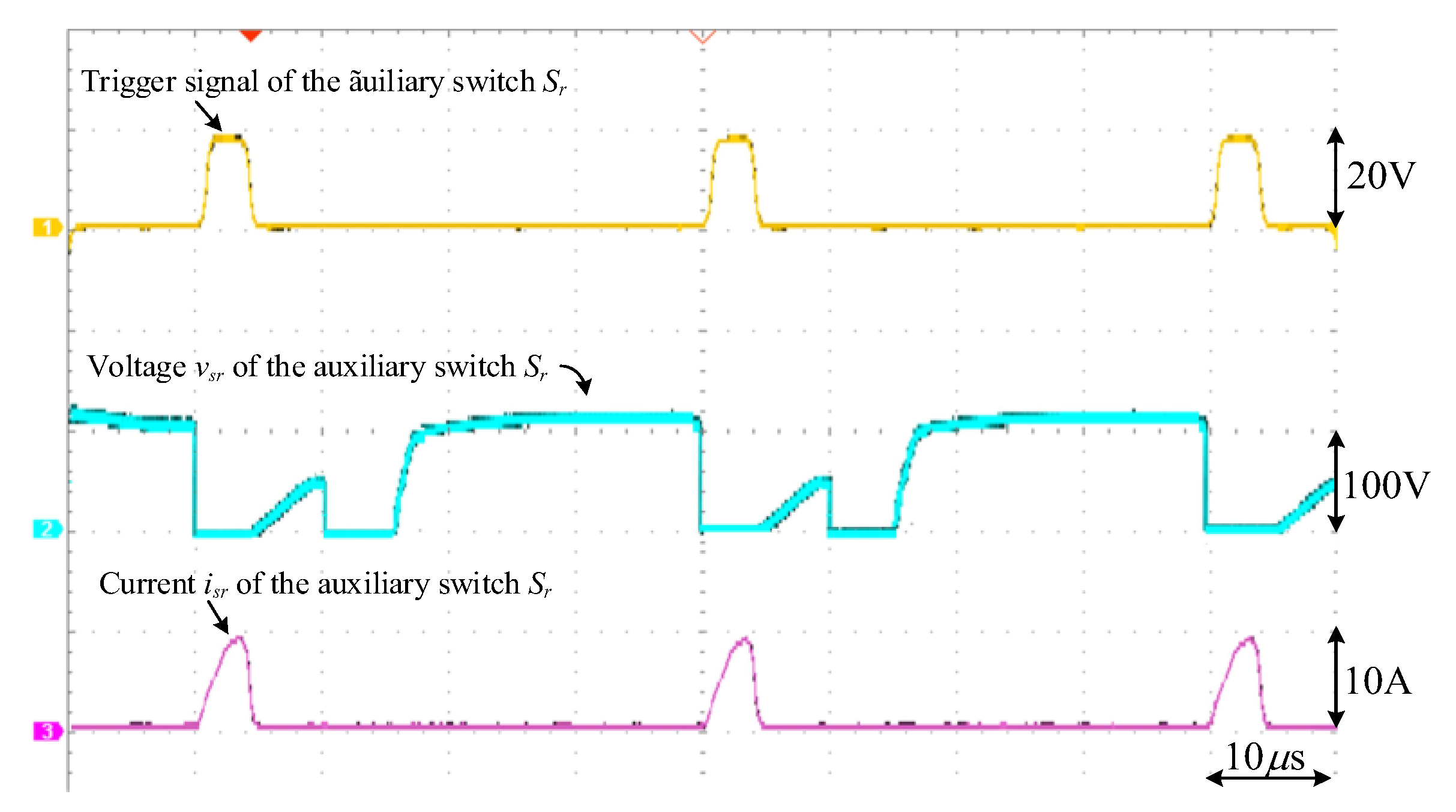

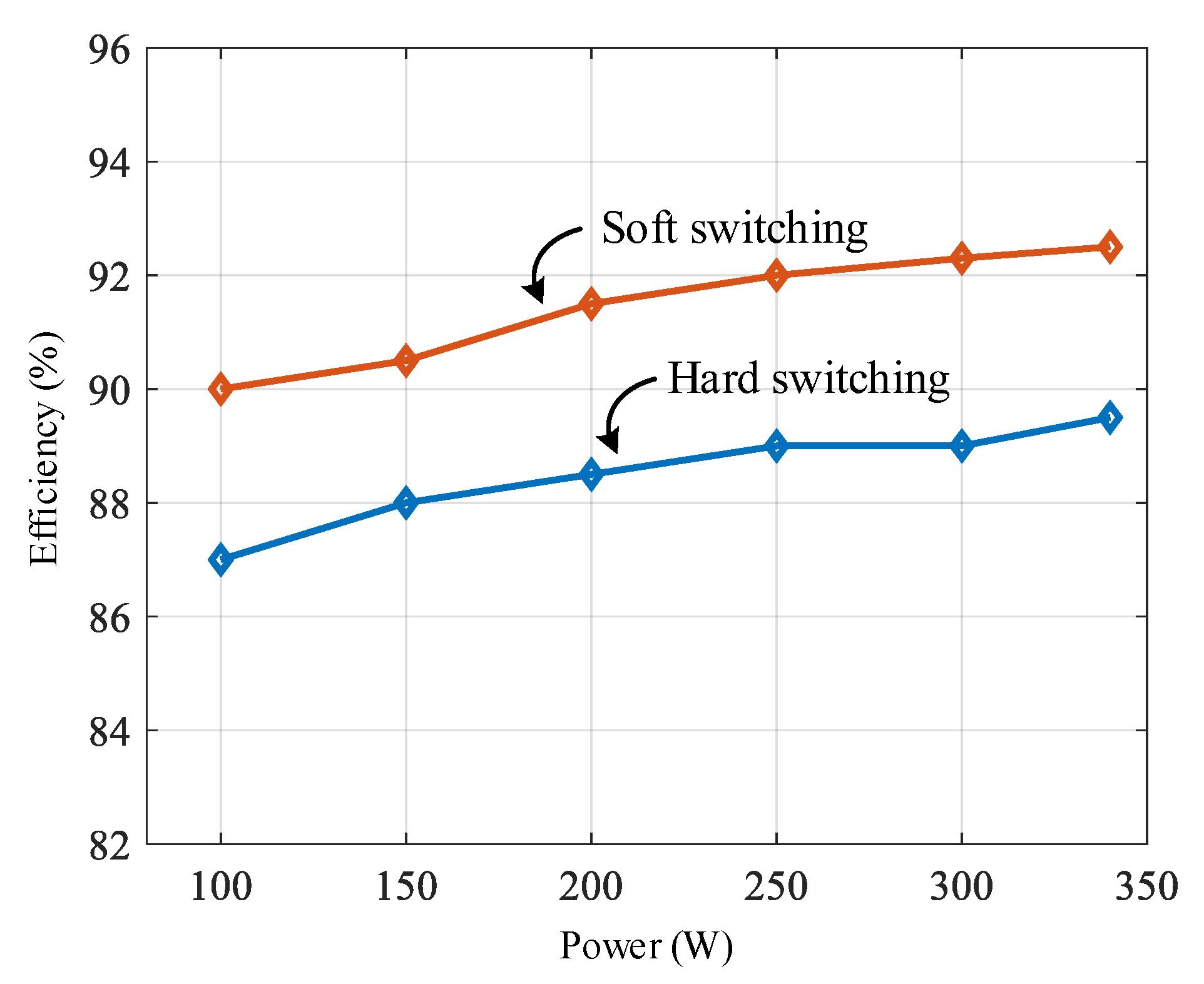

5. Experimental Results

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| ZVS | zero voltage switching |

| DC | direct current |

| AC | alternating current |

| CCM | continuous conduction mode |

| Symbols | |

| the input voltage | |

| the output voltage | |

| the input power | |

| the output power | |

| duty cycle between [0;1] | |

| the switching period of converter | |

| the switch conduction time within one cycle | |

| the switch off time within one cycle | |

| delay time | |

| an additional time delay | |

| the operating time of the auxiliary switch | |

| turns ratio of coupling inductor | |

| , | the number of turns in the first and second coils |

| the conversion ratio of the high voltage ratio soft switching converter | |

| switching frequency | |

| main switch | |

| the current through the main switch S | |

| the voltage across the main switch S | |

| auxiliary switch | |

| the current through the auxiliary switch Sr | |

| the voltage across the auxiliary switch Sr | |

| , | the primary side and secondary side of the coupled inductor |

| , | the current through the primary and secondary sides of the coupled inductor |

| , | the constant current through the primary and secondary sides of the coupled inductor |

| , | the voltage across the primary and secondary sides of the coupled inductor |

| resonant inductor | |

| the current through the resonant inductor Lr | |

| the voltage across the resonant inductor Lr | |

| ,, | fast diodes |

| ,, | the current through the fast diode,and |

| filter capacitor | |

| resonant capacitor | |

| the current through the resonant capacitor | |

| the voltage across the resonant capacitor | |

| energy storage capacitor | |

| the current through the energy storage capacitor | |

| the voltage across the energy storage capacitor | |

| output load | |

| resonance impedance | |

| resonance frequency |

References

- Hart, D.W. Introduction to Power Electronics, 2nd ed.; Pearson Educ. Taiwan Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2002; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Lee, H. Improvements in Light-load Efficiency and Operation Frequency for Low-voltage Current-mode Integrated Boost Converters. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Exp. Briefs 2014, 61, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Moon, G.W.; Youn, M.J. Overview of High-step-up Coupled-inductor Boost Converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2016, 4, 689–704. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyan, S.; Suryawanshi, H.M.; Ballal, M.S.; Shitole, A.B. Soft-switching DC–DC Converter for Distributed Energy Sources with High Step-up Voltage Capability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7039–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; Soon, J.L.; Lu, D.D.; Xiao, W. A High Conversion Ratio and High-efficiency Bidirectional DC–DC Converter with Reduced Voltage Stress. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 11827–11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Brown, B.; Xie, W.; Li, S.; Smedley, K. High Step-up DC–DC Converter with Zero Voltage Switching and Low Input Current Ripple. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 9426–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K.H.; Jheng, Y.C. A Soft-switching Coupled Inductor Bidirectional DC–DC Converter with High Conversion Ratio. Int. J. Electron. 2017, 105, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Liang, T.J.; Chen, K.H.; Chen, S.M. High Step-up DC–DC Converter with Active Switched Inductor and Voltage Doubler Based on Three-winding Coupled Inductor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Houston, TX, USA, 20–24 March 2022; pp. 731–736. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, L.; Martins, D.C.; Coelho, R.F. Generalized High Step-up DC–DC Boost-based Converter with Gain Cell. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2017, 64, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, S.B.; Chatterjee, D.; Siwakoti, Y. Coupled Inductor Based Soft Switched High Gain Bidirectional DC–DC Converter with Reduced Input Current Ripple. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Yao, K. Two-phase Interleaved Boost PFC Converter with Coupled Inductor under Single-phase Operation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyan, S.; Suryawanshi, H.M.; Ballal, M.S.; Shitole, A.B. Soft-switching DC–DC Converter for Distributed Energy Sources with High Step-up Voltage Capability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7039–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powersim. PSIM User Manual, Jan. 2023. Available online: https://powersimtech.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/PSIM-User-Manual.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Texas Instruments. TMS320F2809 Datasheet, Sep. 2022. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/tms320f2809.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Chao, K.H.; Huang, B.Z.; Jian, J.J. An Energy Storage System Composed of Photovoltaic Arrays and Batteries with Uniform Charge/Discharge. Energies 2022, 15, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimharaju, B.L.; Dubey, S.P.; Singh, S.P. Coupled Inductor Bidirectional DC–DC Converter for Improved Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Electronics, Control and Robotics, Kakinada, India, 27–29 December 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

|

| ConverterTopology | Converterin [4] | Converterin [5] | Converterin [6] | Converterin [12] | ProposedConverter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage Gain | |||||

| Voltage Stress onMOSFETs | |||||

| MOSFETs | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Diodes | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Inductors | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Capacitors | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Input Voltage Vi | 72 V10% |

| Output Voltage Vo | 430 V |

| Output Power Po | 340 W |

| Switching Frequency f | 25 kHz |

| Turns Ratio of Coupling Inductor N | 2 |

| Component | Specifications |

| Coupled Inductor L1 | 127H |

| Resonant Inductor Lr | 18H |

| Main Switch S | MOSFET-TK49N65W(650V/49A) |

| Auxiliary Switch Sr | MOSFET-TK49N65W(650V/49A) |

| Fast Diodes(D, D1, D2) | IQBD30E60A1(600V/30A) |

| Filtering Capacitor Co | 340F/900V |

| Resonant Capacitor C1 | 0.33F/400V |

| Energy Storage Capacitor C2 | 0.33F/600V |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).