Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

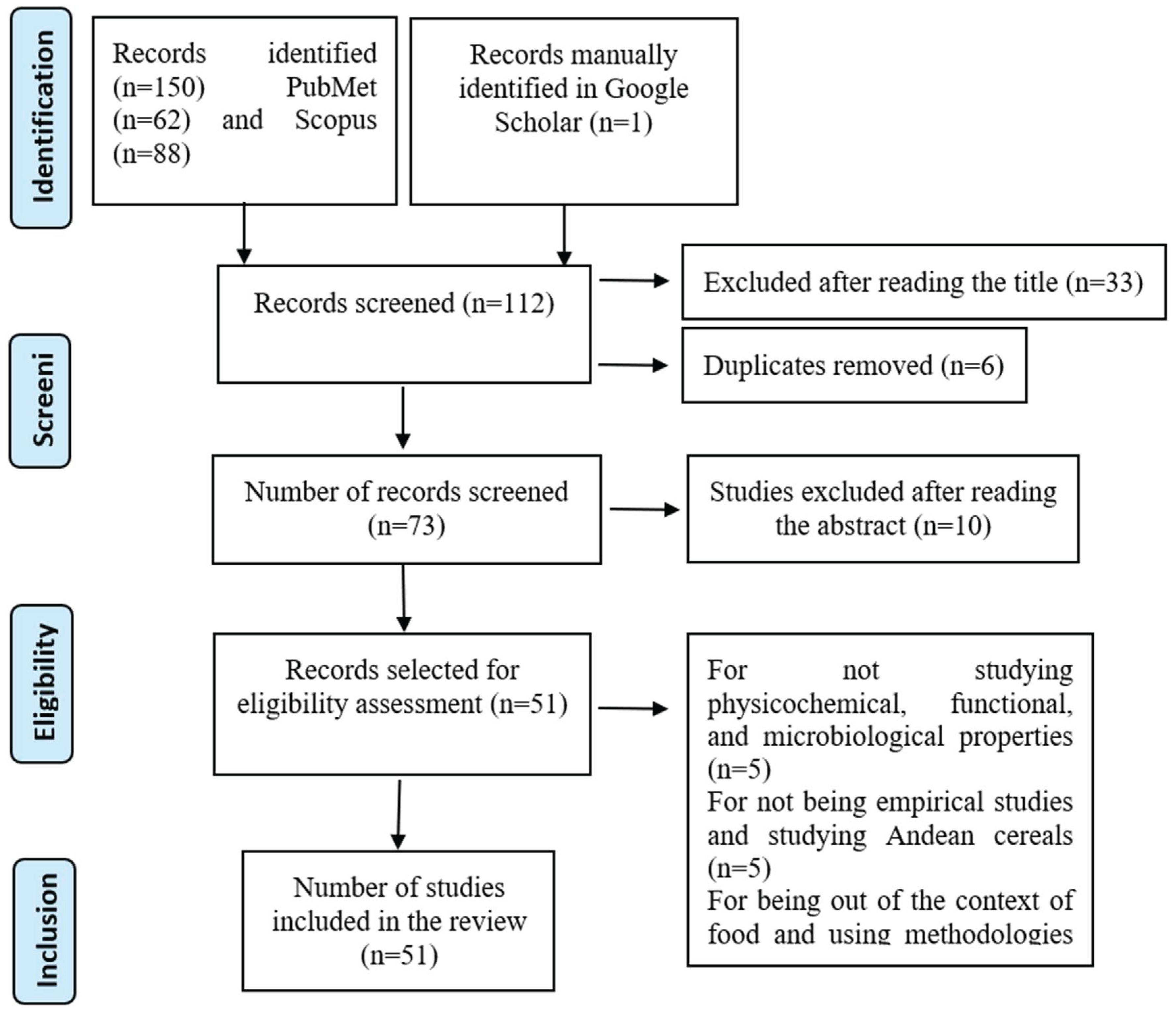

2. Research Methods and Design

2.1. Initial Search

2.2. Systematic Search

- ✓

- They should be empirical research studies and not reviews, single-case studies, books, or manuals.

- ✓

- They must have been published between 2019 and 2025, inclusive.

- ✓

- Articles published in English or Spanish.

- ✓

- Open Access (OA) journal articles.

- ✓

- Lupinus mutabilis and/or Amaranthus spp. flours.

- ✓

- Research that includes analysis of chemical composition, functional properties (such as water absorption capacity, emulsification, antioxidant capacity, etc.), and microbiological safety.

- ✓

- Studies that present redundant information already covered by other selected articles.

- ✓

- Articles that do not provide detailed information on the physicochemical, functional or microbiological characteristics of flour

- ✓

- Review article

- ✓

- Opinions, editorials, conference abstracts, letters to the editor, or articles without experimental data.

- ✓

- Research focuses exclusively on other products derived from these species (such as oils, isolated proteins, etc.) without addressing flour.

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Andean Grains

3.1.1. Superior Value of the Protein and Its Functional Justification

3.1.2. Fat, Fiber and Carbohydrates: Metabolic Advantages and Comparative Applications in Andean Grains

3.1.3. Bioactive Compounds: Why Are They Relevant and How Are They Affected by Processes?

3.1.4. Functional Persistence of Andean Grains in Processed Foods

3.2. Functional and Technological Properties

3.3. Applications in Food Development

3.3.1. Baking: Innovation for Nutrition and Technological Functionality

3.3.2. Dairy Products and Beverages as a Challenge for Plant-Based Innovation

3.3.3. Other Functional Foods: Public Health Perspective

3.4. Sensory Evaluation and Consumer Acceptance

| Product/food matrix | Sensory method used | Number of consumers/panelists | Acceptance and preference (scale, % acceptance, highlighted attributes) | Factors influencing sensory perception | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gluten-free bread (Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp., Chenopodium pallidicaule, Lupinus mutabilis) | Hedonic scale 9 points, CATA, GPA, ANOVA, MFA | 100-250 consumers (varies by study) | Optimal acceptability with ≤20% substitution; >30% decreases acceptance; key attributes: texture, color, flavor, fluffy crumb | Substitution level, texture, color, bitter taste of Chenopodium quinoa, type of preferment, presence of phenolic compounds | (Aguiar et al., 2022) |

| Panettone (Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp.) | CATA, 9-point hedonic scale, preference ranking, Friedman | 80 consumers | Acceptability like commercial with ≤15% substitution; preferred attributes: fluffy, sweet, moist, vanilla scent; preference for PE and PB samples | Type of preferment, proportion of Chenopodium quinoa/Amaranthus spp., sensory attributes (smell, texture, sweetness) | (Jamanca-Gonzales et al., 2022) |

| Gluten-free cookies (Chenopodium pallidicaule, Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp.) | Hedonic scale 9 points, Sorting, CA, ANOVA | 102 consumers | Greater acceptance with 20-30% Chenopodium Pallidicaule; attributes: crisp texture, darker color, pleasant flavor; acceptability >7/9 in better formulations | Chenopodium ratio pallidicaule, texture (hardness, crispness), color, starch and protein content | (Patel et al., 2019) |

| Vegetable burger (Chenopodium quinoa, Lupinus mutabilis, Amaranthus spp.) | CATA, 5-point hedonic scale, CA | 132 consumers | High acceptability (mostly “like it a lot” or “like it”); attributes: easy to cut, soft, legume flavor, healthy | Proportion of ingredients, texture, flavor, color, perception of healthiness | (Chavarri-Uriarte et al., 2025) |

| Vegetable yogurt (Chenopodium quinoa, Lupinus mutabilis ) | Hedonic scale 9 points, JAR, ANOVA | 50-100 consumers | Acceptability decreases >3% Chenopodium Quinoa; attributes: flavor, creamy texture, color; optimal acceptability with ≤3% addition | Level of addition, texture, aftertaste, sweetness | (Rosa & Masala, 2023) |

| Fortified biscuits (Amaranthus spp. and Chenopodium pallidicaule) | 9-point hedonic scale, Sorting, CA | 102 consumers | Optimal acceptability with ≤30% Amaranthus spp./Chenopodium pallidicaule; attributes: crunchy texture, pleasant flavor, dark color | Proportion of fortifier, texture, color, flavor | (Luque-Vilca et al., 2024) |

| Bars/supplements (Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp., Chenopodium pallidicaule) | Hedonic scale 7-9 points, ANOVA | 50 consumers | Good acceptability (>6/9); attributes: flavor, texture, color, healthy perception | Proportion of ingredients, texture, sweetness, aftertaste | (Rios et al., 2020) |

3.4.1. Methodological Rigor and Diversity of Sensory Tools

3.4.2. Necessary Balance Between Innovation and Acceptability

3.4.3. Determining Factors in Sensory Perception

- Level of substitution/addition and type of processing: a key factor that modulates the manifestation of desirable attributes. High substitutions can accentuate phenolic compounds or saponins, responsible for undesirable flavors and dark colors.

- Texture: characteristics such as crunchiness, fluffiness, cohesiveness or hardness are determining factors for preference and usually respond to both the ingredient matrix and the technological treatment (extrusion, baking, fermentation), directly influencing acceptance.

- Flavor and aroma: the "leguminous flavor", sweetness, nutty notes, or the bitterness typical of some Andean compounds, act as limiting parameters and are subject to adjustments through pretreatments or mixtures.

- Color and appearance: For a large proportion of consumers, the “dark color” of Chenopodium pallidicaule or Amaranthus spp. represents a negative factor if it deviates from the traditional visual expectation associated with the reference food

- Perception of healthiness: In functional products, the perception of “natural” ingredients and knowledge of the benefits can compensate for slight disadvantages in taste or texture.

3.5. Impact on Health and Functional Potential

3.5.1. Antioxidant Activity

3.5.2. Reduction of Metabolic Risk Factors

3.5.3. Fiber and Protein Intake

4. Conclusions

References

- Abbas, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y.; Ahmad, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Zhang, R.; Si, D. Production and characterization of novel antioxidant peptides from mulberry leaf ferment using B. subtilis H4 and B. amyloliquefaciens LFB112. Food Chemistry 2025, 482, 144022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, E.V.; Santos, F.G.; Centeno, A.C.L.S.; Capriles, V.D. Defining Amaranth, Buckwheat and Quinoa Flour Levels in Gluten-Free Bread: A Simultaneous Improvement on Physical Properties, Acceptability and Nutrient Composition through Mixture Design. Foods 2022, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, J.M. Food matrices as delivery units of nutrients in processed foods. Journal of Food Science 2025, 90, e70049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rasbi, H.; Gadi, M. Energy Modelling of Traditional and Contemporary Mosque Buildings in Oman. Buildings 2021, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, L.A. Dietary fiber influence on overall health, with an emphasis on CVD, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11, 1510564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-García, M.A.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; López-Vargas, J.H.; Pagán-Moreno, M.J. Techno-Functional Properties of New Andean Ingredients: Maca (Lepidium meyenii) and Amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus). Proceedings 2021, 70, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranzelli, J.; Somacal, S.; Monteiro, C.S.; Mello, R.d.O.; Rodrigues, E.; Prestes, O.D.; López-Ruiz, R.; Garrido Frenich, A.; Romero-González, R.; Miranda, M.Z.d.; et al. Grain Germination Changes the Profile of Phenolic Compounds and Benzoxazinoids in Wheat: A Study on Hard and Soft Cultivars. Molecules 2023, 28, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkerroum, N. Retrospective and Prospective Look at Aflatoxin Research and Development from a Practical Standpoint. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, A.; Glorio-Paulet, P.; Estivi, L.; Locatelli, N.; Cordova-Ramos, J.S.; Hidalgo, A. Tocopherols, carotenoids and phenolics changes during Andean lupin (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) seeds processing. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 106, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, I.D.; Chantelle, L.; Magnani, M.; Cordeiro, A.M. Nutritional, therapeutic, and technological perspectives of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): A review. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46, e16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, M.; Pulina, S.; Conte, P.; Del Caro, A.; Urgeghe, P.P.; Piga, A.; Fadda, C. Effect of Substitution of Rice Flour with Quinoa Flour on the Chemical-Physical, Nutritional, Volatile and Sensory Parameters of Gluten-Free Ladyfinger Biscuits. Foods 2020, 9, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Toimbayeva, D.; Saduakhasova, S.; Kamanova, S.; Kiykbay, A.; Tazhina, S.; Temirova, I.; Muratkhan, M.; Shaimenova, B.; Murat, L.; et al. Prospects for the Use of Amaranth Grain in the Production of Functional and Specialized Food Products. Foods 2025, 14, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Delgado, M.; Chambers, E.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.; Noguera Artiaga, L.; Vidal Quintanar, R.; Burgos Hernandez, A. Consumer acceptability in the USA, Mexico, and Spain of chocolate chip cookies made with partial insect powder replacement. Journal of Food Science 2020, 85, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalampuente-Flores, D.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Ron, A.M.D.; Tapia Bastidas, C.; Sørensen, M. Morphological and Ecogeographical Diversity of the Andean Lupine (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) in the High Andean Region of Ecuador. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E. Analysis of Sensory Properties in Foods: A Special Issue. Foods 2019, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaquilla-Quilca, G.; Islas-Rubio, A.R.; Vásquez-Lara, F.; Salcedo-Sucasaca, L.; Silva-Paz, R.J.; Luna-Valdez, J.G. Chemical, Physical, and Sensory Properties of Bread with Popped Amaranth Flour. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences 2024, 74, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarri-Uriarte, B.J.; Santisteban-Murga, L.N.R.; Tito-Tito, A.B.; Saintila, J.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E. Evaluation of sensory acceptability and iron content of vegan cheeses produced with protein legume isolates and Cushuro algae (Nostoc sphaericum). Food Chemistry Advances 2025, 6, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, J.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, T.; Huang, J.; Gan, L.; Wang, L.; Lin, C.; Fan, H. Microwave and enzyme co-assisted extraction of anthocyanins from Purple-heart Radish: Process optimization, composition analysis and antioxidant activity. LWT 2023, 187, 115312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codină, G.G. Recent Advances in Cereals, Legumes and Oilseeds Grain Products Rheology and Quality. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.M.; Faria, C.; Madalena, D.; Genisheva, Z.; Martins, J.T.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Valorization of Amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus) Grain Extracts for the Development of Alginate-Based Active Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Ramos, J.S.; Glorio-Paulet, P.; Hidalgo, A.; Camarena, F. Efecto del proceso tecnológico sobre la capacidad antioxidante y compuestos fenólicos totales del lupino (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) andino. Scientia Agropecuaria 2020, 11, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahdah, P.; Cabizza, R.; Farbo, M.G.; Fadda, C.; Del Caro, A.; Montanari, L.; Hassoun, G.; Piga, A. Effect of partial substitution of wheat flour with freeze-dried olive pomace on the technological, nutritional, and sensory properties of bread. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, P.; Daelemans, L.; Selis, L.; Raes, K.; Vermeir, P.; Eeckhout, M.; Van Bockstaele, F. Comparison of the Chemical and Technological Characteristics of Wholemeal Flours Obtained from Amaranth (Amaranthus sp.), Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and Buckwheat (Fagopyrum sp.) Seeds. Foods 2021, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, I.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Aquino, Y.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A. New frontiers in the exploration of phenolic compounds and other bioactives as natural preservatives. Food Bioscience 2025, 68, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostalíková, L.; Hlásná Čepková, P.; Janovská, D.; Jágr, M.; Svoboda, P.; Dvořáček, V.; Viehmannová, I. The impact of germination and thermal treatments on bioactive compounds of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seeds. European Food Research and Technology 2024, 250, 1457–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A. The Close Linkage between Nutrition and Environment through Biodiversity and Sustainability: Local Foods, Traditional Recipes, and Sustainable Diets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enciso-Roca, E.C.; Arroyo-Acevedo, J.L.; Común-Ventura, P.W.; Tinco-Jayo, J.A.; Aguilar-Felices, E.J.; Ramos-Meneses, M.B.; Carrera-Palao, R.E.; Herrera-Calderon, O. The Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant and Gastroprotective Effects of Three Varieties of Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Sprouts Cultivated in Peru. Scientia Pharmaceutica 2025, 93, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estivi, L.; Fusi, D.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A. Effect of Debittering with Different Solvents and Ultrasound on Carotenoids, Tocopherols, and Phenolics of Lupinus albus Seeds. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Rudie, C.; Sigman, I.; Grinspoon, S.; Benton, T.G.; Brown, M.E.; Covic, N.; Fitch, K.; Golden, C.D.; Grace, D.; et al. Sustainable food systems and nutrition in the 21st century: A report from the 22nd annual Harvard Nutrition Obesity Symposium. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022, 115, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramón, F.; Sotelo-Méndez, A.; Alvarez-Chancasanampa, H.; Norabuena, E.; Sumarriva, L.; Yachi, K.; Gonzales Huamán, T.; Naupay Vega, M.; Cornelio-Santiago, H.P. Influence of Peruvian Andean grain flours on the nutritional, rheological, physical, and sensory properties of sliced bread. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 1202322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Ni, Q.; Sun, W.; Li, L.; Feng, X. The links between gut microbiota and obesity and obesity related diseases. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 147, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulisano, A.; Alves, S.; Martins, J.N.; Trindade, L.M. Genetics and Breeding of Lupinus mutabilis: An Emerging Protein Crop. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 485490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulisano, A.; Alves, S.; Rodriguez, D.; Murillo, A.; Van Dinter, B.J.; Torres, A.F.; Gordillo-Romero, M.; Torres, M.D.; Neves-Martins, J.; Paulo, M.J.; et al. Diversity and Agronomic Performance of Lupinus mutabilis Germplasm in European and Andean Environments. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 903661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, C.; Ren, G. Influence of the Nutritional Composition of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) on the Sensory Quality of Cooked Quinoa. Foods 2025, 14, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haros, C.M.; Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R.; Basilio-Atencio, J.; Luna-Mercado, G.I.; Pilco-Quesada, S.; Vidaurre-Ruiz, J.; Molina, L. Andean Ancient Grains: Nutritional Value and Novel Uses. Biology and Life Sciences Forum 2022, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Jayadeep, A. Impact of extrusion on the content and bioaccessibility of fat soluble nutraceuticals, phenolics and antioxidants activity in whole maize. Food Research International 2022, 161, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Mai, S.; Li, C. Effects of Extrusion on Starch Molecular Degradation, Order–Disorder Structural Transition and Digestibility—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Li, L.; Kalu, A.; Wu, X.; Naumovski, N. Sustainable Food Security and Nutritional Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Qazanfarzadeh, Z.; Majzoobi, M.; Sheiband, S.; Oladzadabbasabad, N.; Esmaeili, Y.; Barrow, C.J.; Timms, W. Alternative proteins; A path to sustainable diets and environment. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 9, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamanca-Gonzales, N.C.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Eguilas-Caushi, Y.M.; Padilla-Fabian, R.A.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Technofunctional Properties and Rheological Behavior of Quinoa, Kiwicha, Wheat Flours and Their Mixtures. Molecules 2024, 29, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamanca-Gonzales, N.C.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Quintana-Salazar, N.B.; Jimenez-Bustamante, J.N.; Huaman, E.E.H.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Physicochemical and Sensory Parameters of “Petipan” Enriched with Heme Iron and Andean Grain Flours. Molecules 2023, 28, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamanca-Gonzales, N.C.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Quintana-Salazar, N.B.; Siche, R.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Influence of Preferments on the Physicochemical and Sensory Quality of Traditional Panettone. Foods 2022, 11, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamać, M.; Gai, F.; Longato, E.; Meineri, G.; Janiak, M.A.; Amarowicz, R.; Peiretti, P.G. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Composition of Amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus) during Plant Growth. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katyal, M.; Thakur, S.; Singh, N.; Khatkar, B.S.; Shishodia, S.K. A review of wheat chapatti: Quality attributes and shelf stability parameters. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 4, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwar, J.; Das, M.; Gogoi, M.; Kaman, P.K.; Goswami, S.; Sarma, J.; Pathak, P.; Das Purkayastha, M. Enemies of Citrus Fruit Juice: Formation Mechanism and State-of-the-Art Removal Techniques. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science 2024, 12, 977–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Guleria, S.; Kimta, N.; Dhalaria, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Alomar, S.Y.; Kuca, K. Amaranth and buckwheat grains: Nutritional profile, development of functional foods, their pre-clinical cum clinical aspects and enrichment in feed. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 9, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusio, K.; Szafrańska, J.O.; Radzki, W.; Sołowiej, B.G. Effect of Whey Protein Concentrate on Physicochemical, Sensory and Antioxidative Properties of High-Protein Fat-Free Dairy Desserts. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussmann, M.; Abe Cunha, D.H.; Berciano, S. Bioactive compounds for human and planetary health. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10, 1193848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kwak, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y. Combination of the Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) Method and Just-About-Right (JAR) Scale to Evaluate Korean Traditional Rice Wine (Yakju). Foods 2021, 10, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, G. Beverages developed from pseudocereals (quinoa, buckwheat, and amaranth): Nutritional and functional properties. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2025, 24, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llontop-Bernabé, K.S.; Intiquilla, A.; Ramirez-Veliz, C.; Santos, M.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Paterson, S.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Production of Multifunctional Hydrolysates from the Lupinus mutabilis Protein Using a Micrococcus sp. PC7 Protease. BioTech 2025, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobanov, V.G.; Slepokurova, Y.I.; Zharkova, I.M.; Koleva, T.N.; Roslyakov, Y.F.; Krasteva, A.P. Economic effect of innovative flour-based functional foods production. Foods and Raw Materials 2018, 6, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Márquez Gallego, A.; Vera Pasamontes, G.; Uranga Ocio, J.A.; Garcés-Rimón, M.; Miguel-Castro, M. Red Quinoa Hydrolysates with Antioxidant Properties Improve Cardiovascular Health in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Vilca, O.M.; Paredes-Erquinigo, J.Y.; Quille-Quille, L.; Choque-Rivera, T.J.; Cabel-Moscoso, D.J.; Rivera-Ashqui, T.A.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Utilization of Sustainable Ingredients (Cañihua Flour, Whey, and Potato Starch) in Gluten-Free Cookie Development: Analysis of Technological and Sensorial Attributes. Foods 2024, 13, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Vilca, O.M.; Paredes-Erquinigo, J.Y.; Quille-Quille, L.; Choque-Rivera, T.J.; Cabel-Moscoso, D.J.; Rivera-Ashqui, T.A.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Utilization of Sustainable Ingredients (Cañihua Flour, Whey, and Potato Starch) in Gluten-Free Cookie Development: Analysis of Technological and Sensorial Attributes. Foods 2024, 13, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, A.O.; Mársico, E.T.; Soares Júnior, M.S.; Monteiro, M.L.G. EVALUATION OF THE TECHNOLOGICAL QUALITY OF SNACKS EXTRUDED FROM BROKEN GRAINS OF RICE AND MECHANICALLY SEPARATED TILAPIA MEAT FLOUR. Boletim Do Instituto de Pesca 2019, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhenič, A.Č.; Levart, A.; Salobir, J.; Prevc, T.; Pajk Žontar, T. Can Plant-Based Cheese Substitutes Nutritionally and Sensorially Replace Cheese in Our Diet? Foods 2025, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulajová, A.; Matejčeková, Z.; Kohajdová, Z.; Mošovská, S.; Hybenová, E.; Valík, Ľ. Changes in phenolic composition, antioxidant, sensory and microbiological properties during fermentation and storage of maize products. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2024, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Ramos, K.C.; Sanz-Ponce, N.; Haros, C.M. Evaluation of technological and nutritional quality of bread enriched with amaranth flour. LWT 2019, 114, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Coţovanu, I.; Mironeasa, C.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M. A Review of the Changes Produced by Extrusion Cooking on the Bioactive Compounds from Vegetal Sources. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; Clark, J.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montserrat-De La Paz, S.; Martinez-Lopez, A.; Villanueva-Lazo, A.; Pedroche, J.; Millan, F.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Martinez-Lopez, A.; Villanueva-Lazo, A.; Pedroche, J.; Millan, F.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Novel Antioxidant Protein Hydrolysates from Kiwicha (Amaranthus caudatus L.). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Rojo, C.; Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Chuqui-Diestra, S.R.; Castro-Zavaleta, V. Dietary fiber, polyphenols and sensory and technological acceptability in sliced bread made with mango peel flour. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology 2024, 27, e2023073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Mujica, G.; Mujica, Á.; Chura, E.; Begazo, N.; Jayo-Silva, K.; Oliva, M. Kañihua (Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen), an ancestral Inca seed and optimal functional food and nutraceutical for the industry: Review. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pabon, K.S.; Parra-Polanco, A.S.; Roa-Acosta, D.F.; Hoyos-Concha, J.L.; Bravo-Gomez, J.E. Physical and Paste Properties Comparison of Four Snacks Produced by High Protein Quinoa Flour Extrusion Cooking. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 852224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pabon, K.S.; Roa-Acosta, D.F.; Hoyos-Concha, J.L.; Bravo-Gómez, J.E.; Ortiz-Gómez, V. Quinoa Snack Production at an Industrial Level: Effect of Extrusion and Baking on Digestibility, Bioactive, Rheological, and Physical Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, N.F.; Marchetti, L.; Lorenzo, G.; Andrés, S.C. Comprehensive Study of Changes in Nutritional Quality, Techno-functional Properties, and Microstructure of Bean Flours Obtained from Pretreated Seeds. ACS Food Science and Technology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náthia-Neves, G.; Getachew, A.T.; Santana, Á.L.; Jacobsen, C. Legume Proteins in Food Products: Extraction Techniques, Functional Properties, and Current Challenges. Foods 2025, 14, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.M.; Guiné, R.P.F. Textural Properties of Bakery Products: A Review of Instrumental and Sensory Evaluation Studies. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolade, S.O.; Ezekiel, O.O.; Aderibigbe, O.R. Effects of Germination Periods on Proximate, Mineral, and Antinutrient Profiles of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glacum) and Grain Amaranth (Amaranth cruentus) Flours. Biology and Life Sciences Forum 2025, 40, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Albino, C.; Intiquilla, A.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Rodríguez-Arana, N.; Solano, E.; Flores, E.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Izaguirre, V.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Albumin from Erythrina edulis (Pajuro) as a Promising Source of Multifunctional Peptides. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Gallardo, G.; Quimbiulco-Sánchez, K.; Salas-Sanjuán, M.D.; del Moral, F.; Valenzuela, J.L. Alternative Development and Processing of Fermented Beverage and Tempeh Using Green Beans from Four Genotypes of Lupinus mutabilis. Fermentation 2023, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Gallardo, G.; Salas-Sanjuán, M.D.; Moral Torres, F.D.; Valenzuela Manjón-Cabeza, J.L. Characterising the Nutritional and Alkaloid Profiles of Tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) Pods and Seeds at Different Stages of Ripening. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Rauf, A. Edible insects as innovative foods: Nutritional and functional assessments. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 86, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Schmiele, M.; Lavado-Cruz, A.A.; Verona-Ruiz, A.L.; Mollá, C.; Peñas, E.; Frias, J.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Andean Sprouted Pseudocereals to Produce Healthier Extrudates: Impact in Nutritional and Physicochemical Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Esquivel-Paredes, L.J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Schmiele, M. Optimization of rheological properties of bread dough with substitution of wheat flour for whole grain flours from germinated Andean pseudocereals. Ciência Rural 2024, 54, e20220402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Vásquez Guzmán, J.C.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Enhancing Nutritional Profile of Pasta: The Impact of Sprouted Pseudocereals and Cushuro on Digestibility and Health Potential. Foods 2023, 12, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Vásquez Guzmán, J.C.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Enhancing Nutritional Profile of Pasta: The Impact of Sprouted Pseudocereals and Cushuro on Digestibility and Health Potential. Foods 2023, 12, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Sotelo-González, A.M.; López-Echevarría, G.; Martínez-Maldonado, M.A. Amaranth Seeds and Sprouts as Functional Ingredients for the Development of Dietary Fiber, Betalains, and Polyphenol-Enriched Minced Tilapia Meat Gels. Molecules 2023, 28, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salinas, M.; Curay, S.; Mangui, J.; Santana, R.; Vásquez, C. Efecto de la asociación con chocho (Lupinus mutabilis) y haba (Vicia faba) sobre los parámetros agronómicos del amaranto (Amaranthus quitensis). Alfa Revista de Investigación En Ciencias Agronómicas y Veterinaria 2022, 6, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, A.; Conte, P.; Fois, S.; Catzeddu, P.; Del Caro, A.; Sanguinetti, A.M.; Fadda, C. Technological, Nutritional and Sensory Properties of an Innovative Gluten-Free Double-Layered Flat Bread Enriched with Amaranth Flour. Foods 2021, 10, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pismag, R.Y.; Rivera, J.D.; Hoyos, J.L.; Bravo, J.E.; Roa, D.F. Effect of extrusion cooking on physical and thermal properties of instant flours: A review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8, 1398908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Bautista, M.A.; Chiquini-Medina, R.A.; Pech-May, N.J.; Castellot-Pedraza, V.; Lee-Borges, B.M.; Escalante-Poot, J.R.; Ganzo-Guerrero, W.I.; Gonzalez-Lazo, E.; Villarino-Valdivieso, A.M.; Marín-Quintero, M.; et al. Seed germination of four amaranth species (Amaranthus spp.). Agro Productividad 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.R. Nutritional quality of bakery products enriched with alternative flours. International Journal of Family & Community Medicine 2024, 8, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Solano-Reynoso, A.M.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Choque-Quispe, Y.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Aiquipa-Pillaca, Á.S. Effect of Germination on the Physicochemical Properties, Functional Groups, Content of Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity of Different Varieties of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Grown in the High Andean Zone of Peru. Foods 2024, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R.; Vidaurre-Ruiz, J.; Luna-Mercado, G.I. Development of Gluten-Free Breads Using Andean Native Grains Quinoa, Kañiwa, Kiwicha and Tarwi. Proceedings 2020, 53, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, F.T.; Amaya, A.A.; Lobo, M.O.; Samman, N.C. Design and Acceptability of a Multi-Ingredients Snack Bar Employing Regional PRODUCTS with High Nutritional Value. Proceedings 2020, 53, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Masala, C. Labeled Hedonic Scale for the Evaluation of Sensory Perception and Acceptance of an Aromatic Myrtle Bitter Liqueur in Consumers with Chemosensory Deficits. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, C.M.; Cortez, G.; Repo-Carrasco, R. Breadmaking use of andean crops quinoa, Kañiwa, Kiwicha, and Tarwi. Cereal Chemistry 2009, 86, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, D.; Arancibia, M.; Ocaña, I.; Rodríguez-Maecker, R.; Bedón, M.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Montero, M.P. Characterization and Technological Potential of Underutilized Ancestral Andean Crop Flours from Ecuador. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Anwar, S.; Nawaz, T.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Ur Rahman, T.; Khan, M.N.R.; Nawaz, T. Securing a sustainable future: The climate change threat to agriculture, food security, and sustainable development goals. Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Applied Sciences 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhuja, A.; Sudha, M.L.; Rahim, A. Effect of incorporation of amaranth flour on the quality of cookies. European Food Research and Technology 2005, 221, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Samarth, R.M.; Vashishth, A.; Pareek, A. Amaranthus as a potential dietary supplement in sports nutrition. CyTA - Journal of Food 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepański, A.; Adamek-Urbańska, D.; Kasprzak, R.; Szudrowicz, H.; Śliwiński, J.; Kamaszewski, M. Lupin: A promising alternative protein source for aquaculture feeds? Aquaculture Reports 2022, 26, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolve, R.; Simonato, B. Impact of Functional Ingredients on the Technological, Sensory, and Health Properties of Bakery Products. Foods 2024, 13, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toydemir, G.; Gultekin Subasi, B.; Hall, R.D.; Beekwilder, J.; Boyacioglu, D.; Capanoglu, E. Effect of food processing on antioxidants, their bioavailability and potential relevance to human health. Food Chemistry: X 2022, 14, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo-Zamora, L.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Romero-Rodríguez, Á.; Lombardero-Fernández, M.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Fernández-Otero, C.I. Genetic Diversity of Local Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and Traceability in the Production of Galician Bread (Protected Geographical Indication) by Microsatellites. Agriculture 2025, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento, M.; Della Croce, C.M.; Bellani, L.; Tassi, E.L.; Echeverria, M.C.; Giorgetti, L. Effect of Sprouting, Fermentation and Cooking on Antioxidant Content and Total Antioxidant Activity in Quinoa and Amaranth. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaurre-Ruiz, J.; Bender, D.; Schönlechner, R. Exploiting pseudocereals as novel high protein grains. Journal of Cereal Science 2023, 114, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Xie, Z.; Yang, F.; Shang, Q.; Yang, F.; Wei, Y. Quantitative analysis of the phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of six quinoa seed grains with different colors. LWT 2024, 203, 116384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dang, B.; Lan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Kuang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. Metabolomics Characterization of Phenolic Compounds in Colored Quinoa and Their Relationship with In Vitro Antioxidant and Hypoglycemic Activities. Molecules 2024, 29, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Species | Proximal composition parameters | Bioactive Compounds | Relevant Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Salazar et al., 2021) | Lupinus mutabilis | Protein: 52.8%, Fat: ~17%, Carbohydrates: 6.9%, Fiber: >10% and Moisture: 5.94–18.87% | Antioxidants: Bittering reduces antioxidant capacity by 52.9%, and spray-drying reduces antioxidant capacity by an additional 8%. Phenols and flavonoids are present. | Lupinus mutabilis is notable for its extremely high protein and fat content. The bitterness reduces its antioxidant capacity. It meets the requirements for "high fiber." Variability is attributed to geography and variety. |

| (Córdova-Ramos et al., 2020) | Lupinus mutabilis | Protein: 41–45%, Fat: 16–18%, Fiber: 9–13% | Polyphenols, antioxidant capacity. | Technological processes (bittering, drying) affect the antioxidant capacity and phenol content. |

| (Pérez-Ramírez et al., 2023) | Lupinus mutabilis (mixture with quinoa and sweet potato) | It does not report individual values, but the mix increases protein and fiber in extruded products. | Does not report individual values | The extruded with Lupinus mutabilis, quinoa and sweet potato improves the protein and fiber profile. |

| (Montserrat-De La Paz et al., 2021) | Amaranthus spp. | Protein: 13–17%, Fat: 6–8% and Fiber: 7–10% | Total polyphenols: 80–180 mg FA/100g | High genetic variability. Amaranthus spp. is a relevant source of antioxidants. |

| (Paucar -Menacho et al., 2024) | Amaranthus spp. | Protein: 13–16%, Fat: 6–8%, Dietary fiber, minerals | Polyphenols, flavonoids, saponins, antioxidants | Germination increases bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity. |

| (Moreno-Rojo et al., 2024) | Amaranthus spp. (germinated) | It does not report individual numerical values, but germination improves digestibility and nutritional profile. | Increase in polyphenol and antioxidant capacity after germination. | The use of Amaranthus spp. germinated in paste improves nutritional and functional potential. |

| (Sindhuja et al., 2005) | Amaranthus spp. (in baking) | Increasing protein and fiber in baked goods with Amaranthus spp. | Does not report individual values. | Improves the nutritional profile of baked goods. |

| Reference | Species/Mixture | Functional and technological properties | Rheological and textural properties | Digestibility of starches and proteins | Effect of technological processes (germination, extrusion, drying, etc.) | Relevant observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Jamanca-Gonzales et al., 2023) | Lupinus mutabilis | High water and oil absorption capacity; gelling properties; high fiber (>10%), protein (>52%), and fat (~17%) content. | Viscoelastic gel-like behavior in doughs; high starch gelatinization temperature (68.4–81.5 °C) due to the presence of non-starch compounds; medium-sized particles. | Starch: low content (6.9%), but high proportion of amylose; high-quality proteins, rich in lysine. | Bittering reduces antioxidant capacity by 52.9%, and spray drying reduces antioxidant capacity by an additional 8%; it maintains the integrity of starch and proteins after milling. | Meets the requirements for "high fiber" status; variability attributed to geographic area and variety; suitable for gluten-free products. |

| (Llontop-Bernabé et al., 2025) | Lupinus mutabilis | Functional capacity affected by processes; significant reduction in polyphenols and antioxidants after debittering and drying. | It does not report numerical values, but it is mentioned that processing affects texture and functionality. | Direct digestibility is not reported, but it is inferred that the reduction in polyphenols may affect bioavailability. | Bittering and drying reduces the antioxidant capacity and phenol content. | Technological processes can compromise functional value if they are not optimized. |

| (Muñoz- Pabon, Roa-Acosta, et al., 2022) | Mix: Lupinus mutabilis + quinoa + sweet potato (extruded) | Increased protein and fiber content in extruded products; improved nutritional and functional profile; products with greater water absorption capacity. | Extrusion produces products with a crisp texture, good cohesiveness and expansion; it improves sensory acceptability. | Extrusion can increase the digestibility of proteins and starches by denaturation and gelatinization. | Extrusion improves texture, digestibility, and nutritional value; individual values are not reported. | Positive synergy between Andean ingredients; suitable for healthy snacks. |

| (Alarcón-García et al., 2020) | Amaranthus spp. | High water absorption capacity; significant source of polyphenols (80–180 mg FA/100 g); genetic variability in functional properties. | Flours with fine particles; good gel formation; suitable for baking and extruded products. | It does not report direct digestibility but highlights the presence of high-quality proteins and starch with good functionality. | Genetic and environmental variability affect functional properties; specific processes are not assessed. | Amaranthus spp. is a significant source of antioxidants and fiber; suitable for functional products. |

| (Vento et al., 2024) | Amaranthus spp. (germinated) | Sprouting increases polyphenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity; it improves water absorption and protein solubility. | Germination reduces paste viscosity but improves the elasticity and cohesiveness of doughs; it facilitates the formation of more homogeneous matrices. | Sprouting increases protein digestibility and mineral bioavailability; it improves starch digestibility. | Germination: Increased bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity; reduction of antinutritional factors; improved technological functionality. | Germination is an optimal process to enhance the functional and technological value of Amaranthus spp. |

| (Paucar -Menacho et al., 2023b) | Amaranthus spp. (germinated) | Use of Amaranthus spp. germinated in pasta improves the nutritional and functional profile; increases polyphenols and antioxidants in the final product. | Pasta with Amaranthus spp. germinated have better texture (greater firmness and elasticity) and sensory acceptability. | Germination improves the digestibility of proteins and starch in the produced pasta. | Germination prior to pasta production increases bioactive compounds and functionality; improves the texture and digestibility of the final product. | Germination is key to the development of functional foods from Amaranthus spp. |

| (Miranda-Ramos et al., 2019) | Amaranthus spp. (in baking) | Increased protein and fiber content in breads; improved nutritional profile; good water absorption capacity in doughs. | Breads with Amaranthus spp. They have a good crumb, greater volume, and acceptable texture; they improve the elasticity and cohesiveness of the dough. | It does not report direct digestibility, but baking can improve the bioavailability of nutrients. | Baking: possible partial loss of antioxidants but improves product texture and acceptability. | Amaranthus spp. It is useful for enriching baked goods and improving their functionality. |

| (Jamanca-Gonzales et al., 2024) | Mixtures: wheat, quinoa, Amaranthus spp. | Amaranthus spp. improves technofunctional properties (water absorption, swelling, apparent density); mixtures exhibit variability in color and microstructure. | Amaranthus spp. Pure: higher apparent viscosity and flow resistance; mixtures with wheat and quinoa: changes in pseudoplasticity and cohesiveness; microstructure: Amaranthus spp. provides a more homogeneous and finer matrix. | It does not report direct digestibility, but the fine and cohesive structure favors digestion in baked products. | Blending and fine grinding improve cohesiveness and texture; variations in color and microstructure depend on proportions. | Amaranthus spp. is key to improving functionality and texture in bread and pastry mixes. |

| ( Katyal et al., 2024) | Mixtures: quinoa, Amaranthus spp., Lupinus mutabilis (in paste) | Mixtures improve the functional and textural properties of pastes, increasing firmness, cohesiveness and viscosity. | Pastas with a higher proportion of Lupinus mutabilis and Amaranthus spp.: greater firmness and cohesiveness; final viscosity and retrogradation increase with Amaranthus spp. | It does not report direct digestibility, but the combination of flours improves the texture and potential digestibility. | Blends allow for fine-tuning the texture and functionality of pasta; cooking improves structure and acceptability. | Positive synergy between pseudocereals and Andean legumes in aqueous matrices. |

| Application/product | Andean grain/mixture | Level of substitution/addition | Nutritional composition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baking: gluten-free bread | Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp., Chenopodium pallidicaule, Lupinus mutabilis | 10-50% addition to starch/potato/corn | Increased protein (up to 13-16%), fiber, minerals and bread volume (with 10-20% Chenopodium quinoa/Amaranthus spp.); improved texture (cohesiveness, firmness); optimal acceptability with ≤20%. | (Repo-Carrasco-Valencia et al., 2020) |

| Baking: cookies | Chenopodium pallidicaule, Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp. | 10-40% replacement | Increased protein (up to 12-15%), fiber, and minerals; optimal sensory acceptability with 20-30% Chenopodium pallidicaule; darker color. | (Luque-Vilca et al., 2024a) |

| Baking: extruded snacks | Chenopodium quinoa, Lupinus mutabilis, sweet potato | 20-40% mix | Improved protein (up to 14-18%), fiber, expansion, and crispness; high sensory acceptability. | (Muñoz- Pabon, Parra-Polanco, et al., 2022) |

| Baking: panettone | Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp. | 10-20% replacement | Increased protein, fiber, and minerals; sensory acceptability like a commercial product with ≤15% | (Cannas et al., 2020) |

| Dairy products: alternative cheese | Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp. | 10-20% replacement | Increased protein and fiber; acceptable texture; moderate sensory acceptability | (Majhenič et al., 2025) |

| Others: supplements/bars | Chenopodium quinoa, Amaranthus spp., Chenopodium pallidicaule | 10-40% mix | Increased protein (up to 15-18%), fiber, and minerals; good sensory acceptability | (Li et al., 2025) |

| Others: fortified foods | Chenopodium quinoa, lupinus mutabilis | 10-20% addition | Increased iron, protein, fiber, and phenolic compounds; variable sensory acceptability | (Guo et al., 2025) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).