Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

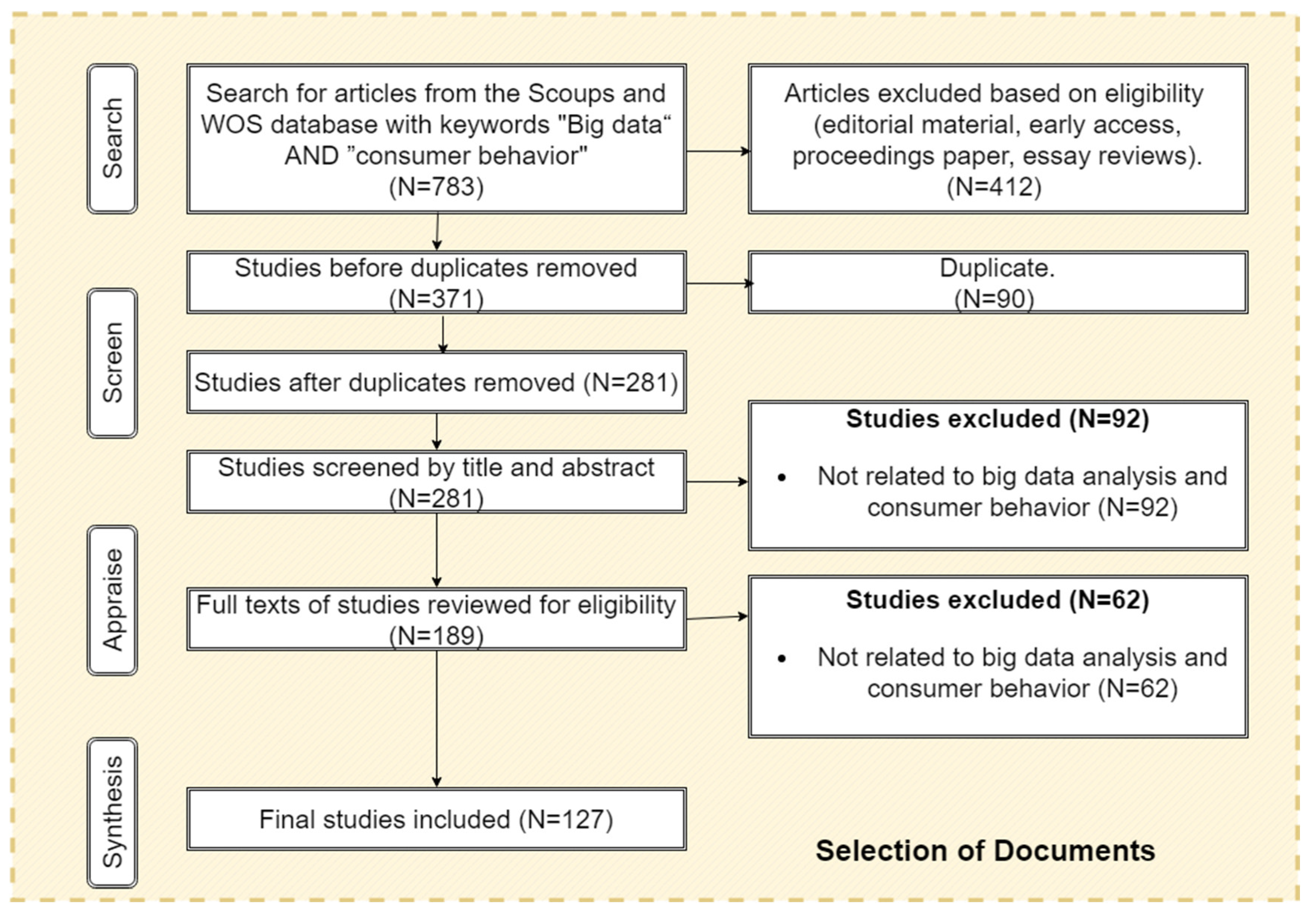

2. Data and Methods

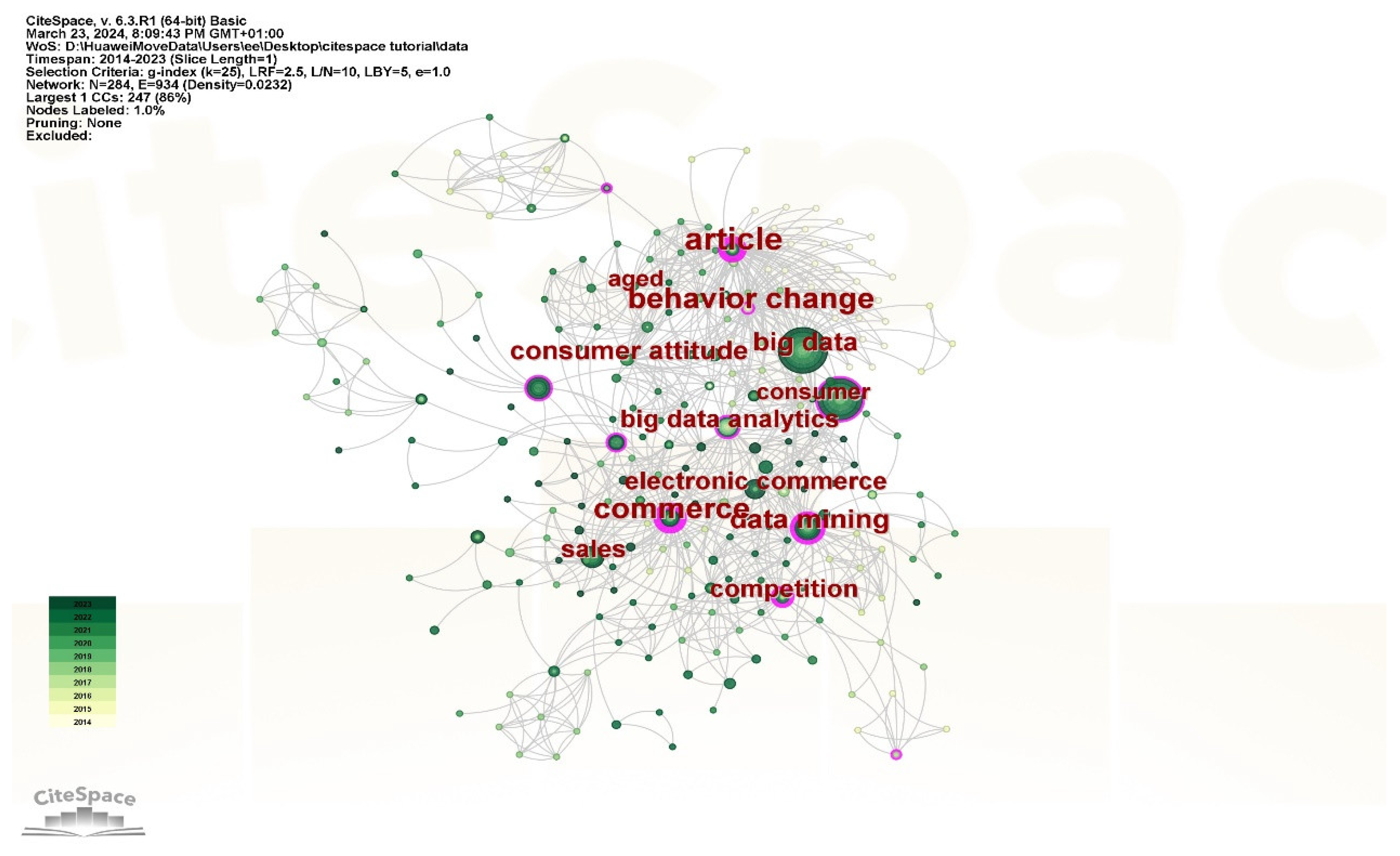

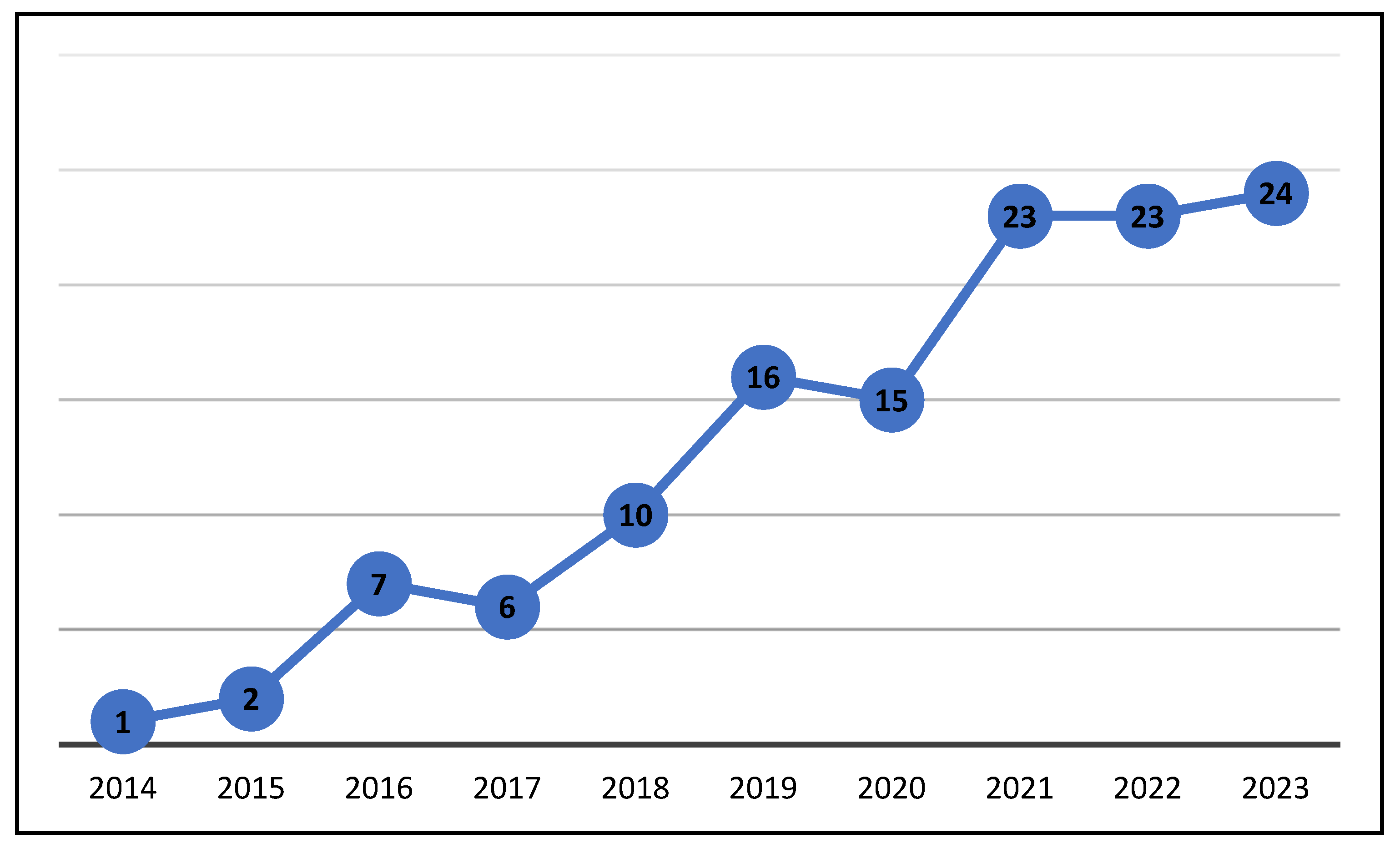

3. Results of Bibliometric Analysis

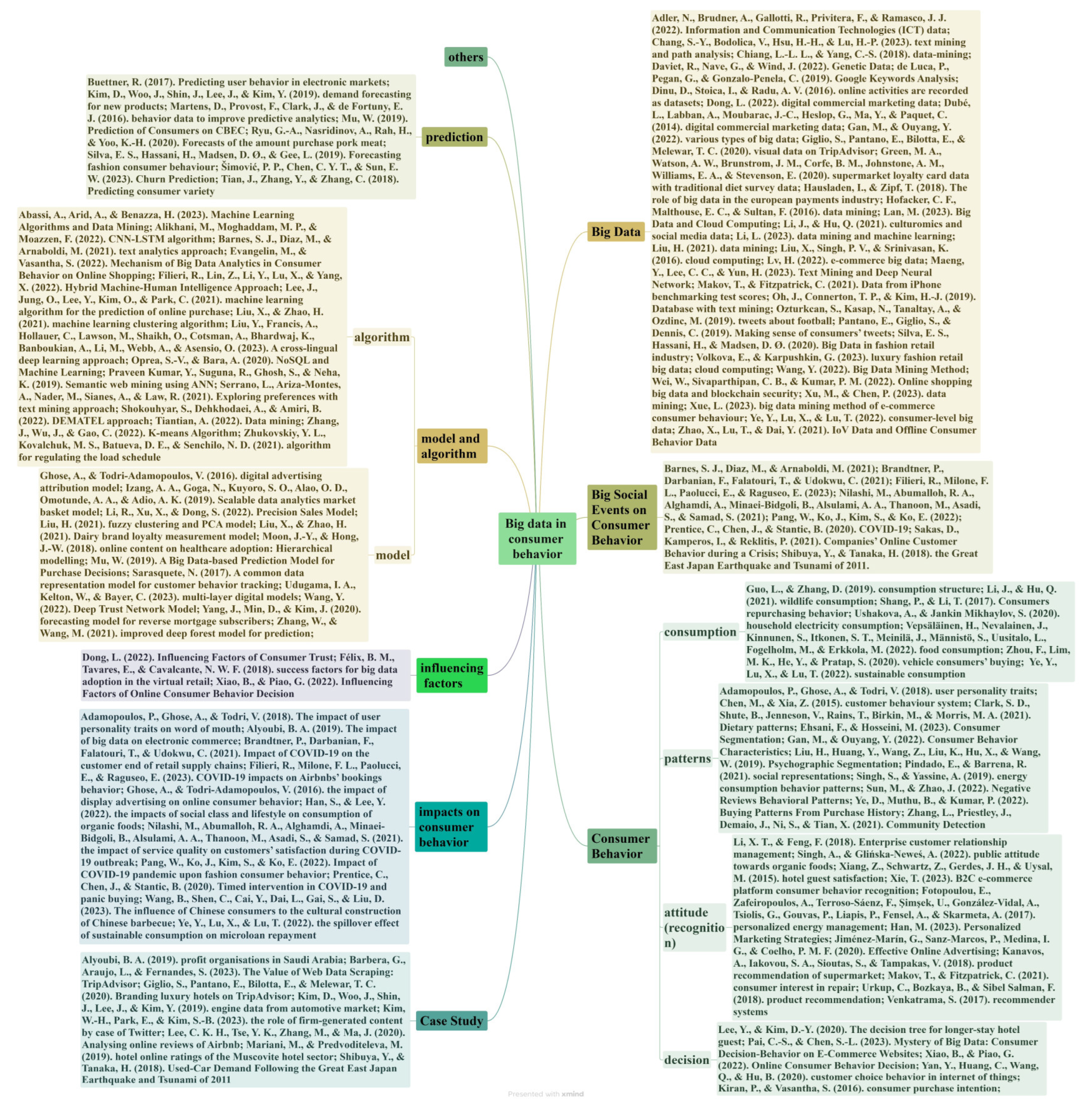

4. Results of the Thematic Analysis

4.1. Types of Big Data Used in Consumer Behavior Research

Unstructured Big Data

Structured Big Data

4.2. Types of Consumer Behavior in Big Data Analysis

Consumer Consumption

Consumer Attitude

Consumer Patterns

Consumer Decision

Predictions of Consumer Behavior

4.3. Application of Models and Algorithms in Big Data Usage

4.4. Other Research Themes of Big Data in Consumer Behavior

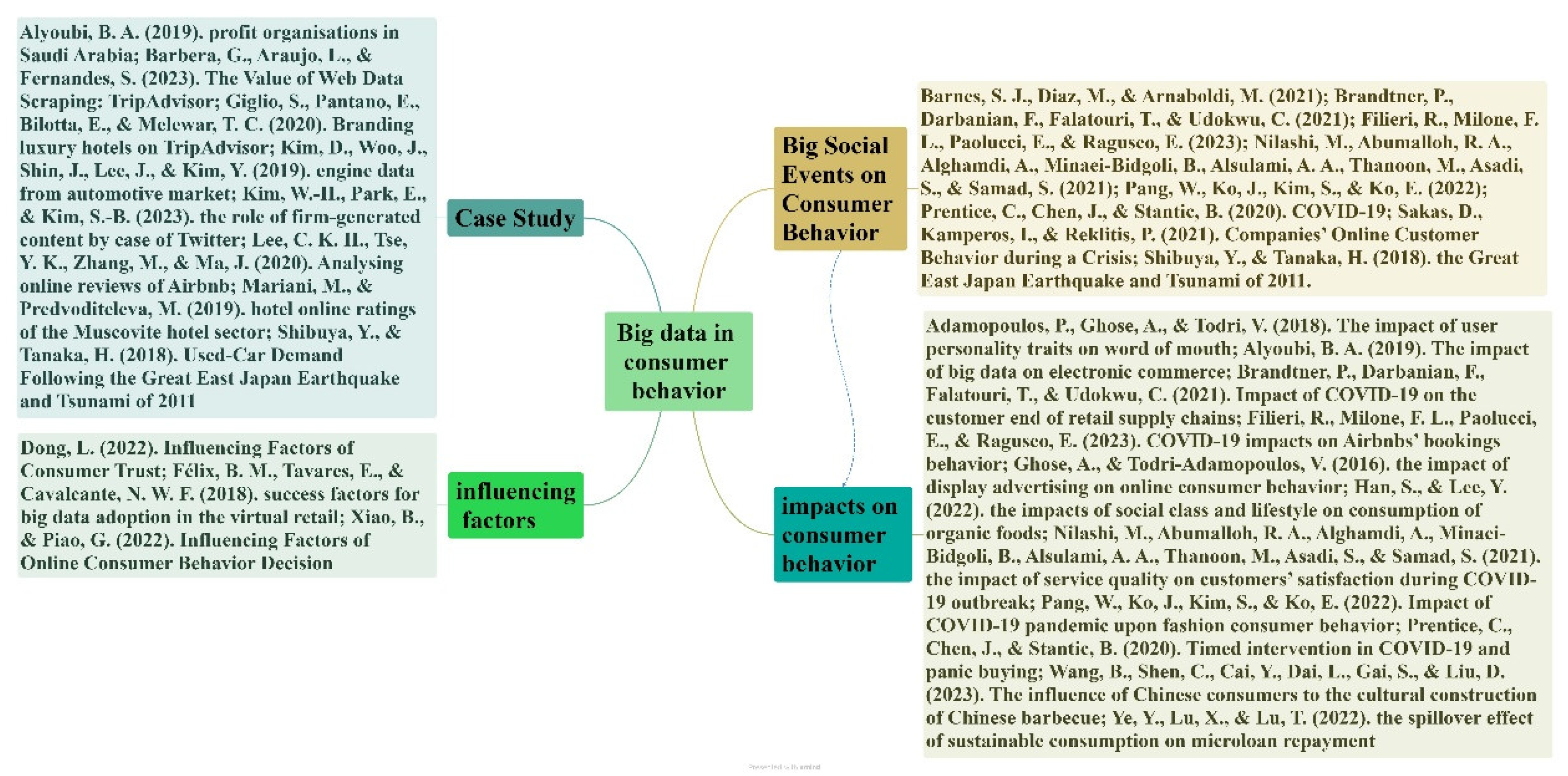

Influencing Factors

Impacts on Consumer Behavior

Big Social Events on Consumer Behavior

Case Study

5. Conclusion

5.1. Main Findings and Implications

5.2. Challenges and Future Directions of Big Data Research in Consumer Behavior

Challenges

Future Directions

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions of This Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A, P. 1969. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. Journal of Documentation 25: 348. [Google Scholar]

- Abassi, A., A. Arid, and H. Benazza. 2023. Moroccan Consumer Energy Consumption Itemsets and Inter-Appliance Associations Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Data Mining Techniques. Journal of Engineering for Sustainable Buildings and Cities 4, 1. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, G., C. A. D’Angelo, and F. Viel. 2011. The field-standardized average impact of national research systems compared to world average: The case of Italy. Scientometrics 88, 2: 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, P., A. Ghose, and V. Todri. 2018. The impact of user personality traits on word of mouth: Text-mining social media platforms. Information Systems Research 29, 3: 612–640, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, F., M. De Rosa, and F. Trabalzi. 2011. Dedicated and generic marketing strategies The disconnection between geographical indications and consumer behavior in Italy. BRITISH FOOD JOURNAL 113, 2–3: 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N., A. Brudner, R. Gallotti, F. Privitera, and J. J. Ramasco. 2022. Does big data help answer big questions? The case of airport catchment areas & competition. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 166: 444–467, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, M., M. P. Moghaddam, and F. Moazzen. 2022. Optimal demand response programs selection using CNN-LSTM algorithm with big data analysis of load curves. IET Generation, Transmission and Distribution 16, 24: 4980–5001, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, A. 2021. USING BIG DATA IN THE REAL ESTATE SECTOR. ADVANCES AND APPLICATIONS IN STATISTICS 67, 2: 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoubi, B. A. 2019. The impact of big data on electronic commerce in profit organisations in Saudi Arabia. Research in World Economy 10, 4: 106–115, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K., O. Burford, and L. Emmerton. 2016. App Chronic Disease Checklist: Protocol to Evaluate Mobile Apps for Chronic Disease Self-Management. JMIR RESEARCH PROTOCOLS 5, 4: e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiceanu, R. F., and R. Seker. 2016. Big Data and virtualization for manufacturing cyber-physical systems: A survey of the current status and future outlook. COMPUTERS IN INDUSTRY 81: 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbado, R., O. Araque, and C. A. Iglesias. 2019. A framework for fake review detection in online consumer electronics retailers. INFORMATION PROCESSING & MANAGEMENT 56, 4: 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, G., L. Araujo, and S. Fernandes. 2023. The Value of Web Data Scraping: An Application to TripAdvisor. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7, 3. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. J., M. Diaz, and M. Arnaboldi. 2021. Understanding panic buying during COVID-19: A text analytics approach. Expert Systems with Applications 169. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Orgaz, G., J. J. Jung, and D. Camacho. 2016. Social big data: Recent achievements and new challenges. INFORMATION FUSION 28: 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S., A. Fole, N. Khare, and P. Agrawal. 2023. Enhancing correlated big data privacy using differential privacy and machine learning. JOURNAL OF BIG DATA 10, 1: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtner, P., F. Darbanian, T. Falatouri, and C. Udokwu. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on the customer end of retail supply chains: A big data analysis of consumer satisfaction. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13, 3: 1–18, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, R. 2017. Predicting user behavior in electronic markets based on personality-mining in large online social networks. ELECTRONIC MARKETS 27, 3: 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S., and S. Verma. 2023. Big Data and Sustainable Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda. VISION-THE JOURNAL OF BUSINESS PERSPECTIVE 27, 1: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-Y., V. Bodolica, H.-H. Hsu, and H.-P. Lu. 2023. What people talk about online and what they intend to do: Related perspectives from text mining and path analysis. Eurasian Business Review 13, 4: 931–956, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. M. 2006. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 57, 3: 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., and Z. Xia. 2015. Deduction of customer behaviour system under the background of big data. Oxidation Communications 38, 2A: 1142–1153, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, L.-L. L., and C.-S. Yang. 2018. Does country-of-origin brand personality generate retail customer lifetime value? A Big Data analytics approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 130: 177–187, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. D., B. Shute, V. Jenneson, T. Rains, M. Birkin, and M. A. Morris. 2021. Dietary patterns derived from UK supermarket transaction data with nutrient and socioeconomic profiles. Nutrients 13, 5. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, K., M. Alam, M. S. Al-Rakhami, and A. Gumaei. 2021. Machine learning-based mathematical modelling for prediction of social media consumer behavior using big data analytics. JOURNAL OF BIG DATA 8, 1: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. L. P., and C.-Y. Zhang. 2014. Data-intensive applications, challenges, techniques and technologies: A survey on Big Data. INFORMATION SCIENCES 275: 314–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, A. 2011. Consumer behaviour in the market of catering services in selected countries of Central-Eastern Europe. BRITISH FOOD JOURNAL 113, 1: 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviet, R., G. Nave, and J. Wind. 2022. Genetic Data: Potential Uses and Misuses in Marketing. Journal of Marketing 86, 1: 7–26, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luca, P., G. Pegan, and C. Gonzalo-Penela. 2019. Insights from a Google Keywords Analysis about Italian Wine in the US Market. Micro and Macro Marketing 1: 93–116, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desarkar, A., and A. Das. 2017. Big-Data Analytics, Machine Learning Algorithms and Scalable/Parallel/Distributed Algorithms. In INTERNET OF THINGS AND BIG DATA TECHNOLOGIES FOR NEXT GENERATION HEALTHCARE. Edited by C. Bhatt, N. Dey and A. S. Ashour. Springer International Publishing Ag: Vol. 23, pp. 159–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, A., and S. C. Wolter. 2013. The Use of Bibliometrics to Measure Research Performance in Education Sciences. Research in Higher Education 54, 1: 86–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, D., I. Stoica, and A. V. Radu. 2016. Studying the consumer behavior through big data. Quality-Access to Success 17: 246–254, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L. 2022. Analysis on Influencing Factors of Consumer Trust in E-Commerce Marketing of Green Agricultural Products Based on Big Data Analysis. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G., and Y. Lin. 2022. Brand connection and entry in the shopping mall ecological chain: Evidence from consumer behavior big data analysis based on two-sided markets. Journal of Cleaner Production 364. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L., A. Labban, J.-C. Moubarac, G. Heslop, Y. Ma, and C. Paquet. 2014. A nutrition/health mindset on commercial Big Data and drivers of food demand in modern and traditional systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1331, 1: 278–295, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, C. B., and D. K. Das. 2017. What drives consumers’ online information search behavior? Evidence from England. JOURNAL OF RETAILING AND CONSUMER SERVICES 35: 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, N. van, and L. Waltman. 2009. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84, 2: 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, F., and M. Hosseini. 2023. Consumer Segmentation Based on Location and Timing Dimensions Using Big Data from Business-to-Customer Retailing Marketplaces. Big Data. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Majdouli, M. A., I. Rbouh, S. Bougrine, B. El Benani, and A. A. El Imrani. 2016. Fireworks algorithm framework for Big Data optimization. MEMETIC COMPUTING 8, 4: 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelin, M., and S. Vasantha. 2022. Mechanism of Big Data Analytics in Consumer Behavior on Online Shopping. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF EARLY CHILDHOOD SPECIAL EDUCATION 14, 3: 1938–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., H. Wang, L. Zhao, F. Yu, and C. Wang. 2020. Dynamic knowledge graph based fake-review detection. APPLIED INTELLIGENCE 50, 12: 4281–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, B. M., E. Tavares, and N. W. F. Cavalcante. 2018. Critical success factors for big data adoption in the virtual retail: Magazine luiza case study. Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios 20, 1: 112–126, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rovira, C., J. Álvarez Valdés, G. Molleví, and R. Nicolas-Sans. 2021. The digital transformation of business. Towards the datafication of the relationship with customers. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 162. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Z. Lin, Y. Li, X. Lu, and X. Yang. 2022. Customer Emotions in Service Robot Encounters: A Hybrid Machine-Human Intelligence Approach. JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH 25, 4: 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., F. L. Milone, E. Paolucci, and E. Raguseo. 2023. A big data analysis of COVID-19 impacts on Airbnbs’ bookings behavior applying construal level and signaling theories. International Journal of Hospitality Management 111: 103461, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, E., A. Zafeiropoulos, F. Terroso-Sáenz, U. Şimşek, A. González-Vidal, G. Tsiolis, P. Gouvas, P. Liapis, A. Fensel, and A. Skarmeta. 2017. Providing personalized energy management and awareness services for energy efficiency in smart buildings. Sensors (Switzerland) 17, 9. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M., and Y. Ouyang. 2022. Study on Tourism Consumer Behavior Characteristics Based on Big Data Analysis. FRONTIERS IN PSYCHOLOGY 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A., and V. Todri-Adamopoulos. 2016. TOWARD A DIGITAL ATTRIBUTION MODEL: MEASURING THE IMPACT OF DISPLAY ADVERTISING ON ONLINE CONSUMER BEHAVIOR. MIS QUARTERLY 40, 4: 889-+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, S., E. Pantano, E. Bilotta, and T. C. Melewar. 2020. Branding luxury hotels: Evidence from the analysis of consumers’ “big” visual data on TripAdvisor. Journal of Business Research 119: 495–501, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohammadi, A., T. Havakhor, D. Gauri, and J. Comprix. 2021. Complaint Publicization in Social Media. JOURNAL OF MARKETING 85, 6: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandhi, B., N. Patwa, and K. Saleem. 2021. Data-driven marketing for growth and profitability. EuroMed Journal of Business 16, 4: 381–398, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. A., A. W. Watson, J. M. Brunstrom, B. M. Corfe, A. M. Johnstone, E. A. Williams, and E. Stevenson. 2020. Comparing supermarket loyalty card data with traditional diet survey data for understanding how protein is purchased and consumed in older adults for the UK, 2014-16. Nutrition Journal 19, 1. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., and D. Zhang. 2019. EC-structure: Establishing consumption structure through mining E-commerce data to discover consumption upgrade. Complexity 2019. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. 2023. Consumer Behavior Analysis and Personalized Marketing Strategies for the Internet of Things. RISTI-Revista Iberica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informacao 2023, Special issue E63: 367–376, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S., and Y. Lee. 2022. Analysis of the impacts of social class and lifestyle on consumption of organic foods in South Korea. Heliyon 8, 10. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausladen, I., and T. Zipf. 2018. Competitive differentiation versus commoditisation: The role of big data in the european payments industry. Journal of Payments Strategy and Systems 12, 3: 266–282, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havranek, T., and A. Zeynalov. 2021. Forecasting tourist arrivals: Google Trends meets mixed-frequency data. TOURISM ECONOMICS 27, 1: 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofacker, C. F., E. C. Malthouse, and F. Sultan. 2016. Big Data and consumer behavior: Imminent opportunities. Journal of Consumer Marketing 33, 2: 89–97, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M., and A. Ghalamkari. 2018. Analysis Social Media Based Brand Communities and Consumer Behavior: A Netnographic Approach. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF E-BUSINESS RESEARCH 14, 1: 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierkens, J. B., P. Fearnhead, and G. Roberts. 2019. The Zig-Zag Process and Super-Efficient Sampling for Bayesian Analysis of Big Data. ANNALS OF STATISTICS 47, 3: 1288–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izang, A. A., N. Goga, S. O. Kuyoro, O. D. Alao, A. A. Omotunde, and A. K. Adio. 2019. Scalable data analytics market basket model for transactional data streams. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 10, 10: 61–68, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I., and D. Ivanov. 2023. A beautiful shock? Exploring the impact of pandemic shocks on the accuracy of AI forecasting in the beauty care industry. TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH PART E-LOGISTICS AND TRANSPORTATION REVIEW 180: 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, J. 2023. The future of marketing: How cultural understanding contributes to the success of brand positioning and campaigns. Journal of Digital and Social Media Marketing 11, 3: 225–235, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Marín, G., P. Sanz-Marcos, I. G. Medina, and P. M. F. Coelho. 2020. How Big Data Collected Via Point of Sale Devices in Textile Stores in Spain Resulted in Effective Online Advertising Targeting. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies 14, 13: 65–77, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J., S. Yeo, Y. Lee, S. Moon, and D.-J. Lee. 2021. Factors affecting consumers’ preferences for electric vehicle: A Korean case. RESEARCH IN TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT 41: 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanavos, A., S. A. Iakovou, S. Sioutas, and V. Tampakas. 2018. Large scale product recommendation of supermarket ware based on customer behaviour analysis. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2, 2: 1–19, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., J. Woo, J. Shin, J. Lee, and Y. Kim. 2019. Can search engine data improve accuracy of demand forecasting for new products? Evidence from automotive market. Industrial Management and Data Systems 119, 5: 1089–1103, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-H., E. Park, and S.-B. Kim. 2023. Understanding the role of firm-generated content by hotel segment: The case of Twitter. Current Issues in Tourism 26, 1: 122–136, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, P., and S. Vasantha. 2016. Analysing the role of user generated content on consumer purchase intention in the new era of social media and big data. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 9, 43. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L. I. 2014. Fostering Consumer-Brand Relationships in Social Media Environments: The Role of Parasocial Interaction. JOURNAL OF INTERACTIVE MARKETING 28, 2: 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M. 2023. Big Data and Cloud Computing-Integrated Tourism Decision-Making in Smart Logistics Technologies. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF E-COLLABORATION 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. K. H., Y. K. Tse, M. Zhang, and J. Ma. 2020. Analysing online reviews to investigate customer behaviour in the sharing economy: The case of Airbnb. Information Technology and People 33, 3: 945–961, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., O. Jung, Y. Lee, O. Kim, and C. Park. 2021. A comparison and interpretation of machine learning algorithm for the prediction of online purchase conversion. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, 5: 1472–1491, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., and D.-Y. Kim. 2020. The decision tree for longer-stay hotel guest: The relationship between hotel booking determinants and geographical distance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33, 6: 2264–2282, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., and Q. Hu. 2021. Using culturomics and social media data to characterize wildlife consumption. Conservation Biology 35, 2: 452–459, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. 2023. Analysis of e-commerce customers’ shopping behavior based on data mining and machine learning. Soft Computing. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., X. Xu, and S. Dong. 2022. Construction of Precision Sales Model for Luxury Market Based on Machine Learning. Mobile Information Systems 2022. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. T., and F. Feng. 2018. Enterprise customer relationship management based on big data mining. Latin American Applied Research 48, 3: 163–168, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. 2021. Big data precision marketing and consumer behavior analysis based on fuzzy clustering and PCA model. Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems 40, 4: 6529–6539, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Y. Huang, Z. Wang, K. Liu, X. Hu, and W. Wang. 2019. Personality or Value: A Comparative Study of Psychographic Segmentation Based on an Online Review Enhanced Recommender System. APPLIED SCIENCES-BASEL 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., P. V. Singh, and K. Srinivasan. 2016. A structured analysis of unstructured big data by leveraging cloud computing. Marketing Science 35, 3: 363–388, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., and H. Zhao. 2021. Dairy brand loyalty measurement model based on machine learning clustering algorithm. Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems 40, 4: 7601–7612, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. 2016. Design and implementation of hadoop-based customer marketing big data processing system. International Journal of Database Theory and Application 9, 12: 331–340, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., A. Francis, C. Hollauer, M. Lawson, O. Shaikh, A. Cotsman, K. Bhardwaj, A. Banboukian, M. Li, A. Webb, and O. Asensio. 2023. Reliability of electric vehicle charging infrastructure: A cross-lingual deep learning approach. COMMUNICATIONS IN TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H. 2022. Intelligent e-commerce framework for consumer behavior analysis using big data Analytics. ADVANCES IN DATA SCIENCE AND ADAPTIVE ANALYSIS 14, 03N04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H. 2023. E-commerce consumer behavior analysis based on big data. Journal of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering 23, 2: 651–661, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H., S. Shi, and D. Gursoy. 2022. A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of big data and artificial intelligence literature in hospitality and tourism. JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY MARKETING & MANAGEMENT 31, 2: 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, Y., C. C. Lee, and H. Yun. 2023. Understanding Antecedents That Affect Customer Evaluations of Head-Mounted Display VR Devices through Text Mining and Deep Neural Network. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 18, 3: 1238–1256, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makov, T., and C. Fitzpatrick. 2021. Is repairability enough? Big data insights into smartphone obsolescence and consumer interest in repair. Journal of Cleaner Production 313. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., M. Borghi, and S. Kazakov. 2019. The role of language in the online evaluation of hospitality service encounters: An empirical study. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT 78: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., and M. Predvoditeleva. 2019. How do online reviewers’ cultural traits and perceived experience influence hotel online ratings? An empirical analysis of the Muscovite hotel sector. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT 31, 12: 4543–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D., F. Provost, J. Clark, and E. J. de Fortuny. 2016. Mining massive fine-grained behavior data to improve predictive analytics. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 40, 4: 869–888, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. D., and P. E. Murphy. 2017. The role of data privacy in marketing. JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE 45, 2: 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, P., and A. Scharnhorst. 2015. Scientometrics and information retrieval: Weak-links revitalized. Scientometrics 102, 3: 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta-Aragón, A., and T. Garín-Muñoz. 2023. Consumer behaviour in e-Tourism: Exploring new applications of machine learning in tourism studies. Investigaciones Turisticas 26: 350–374, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and the PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151, 4: 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D., L. Shamseer, M. Clarke, D. Ghersi, A. Liberati, M. Petticrew, P. Shekelle, L. A. Stewart, and PRISMA-P Group. 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 4, 1: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molitor, D., S. Daurer, M. Spann, and P. Manchanda. 2023. Digitizing local search: An empirical analysis of mobile search behavior in offline shopping. Decision Support Systems 174. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-Y., and J.-W. Hong. 2018. The differential effects of online content on healthcare adoption: Hierarchical modelling. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 96, 6: 1722–1731, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M. A., E. L. Wilkins, M. Galazoula, S. D. Clark, and M. Birkin. 2020. Assessing diet in a university student population: A longitudinal food card transaction data approach. British Journal of Nutrition 123, 12: 1406–1414, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G. P. 2012. Consumer Behavior in Later Life: Current Knowledge, Issues, and New Directions for Research. PSYCHOLOGY & MARKETING 29, 2: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W. 2019. A Big Data-based Prediction Model for Purchase Decisions of Consumers on Cross-border E-commerce Platforms. Journal Europeen Des Systemes Automatises 52, 4: 363–368, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraine, M. L., N. O’Reilly, N. Levallet, and L. Wanless. 2020. If you build it, will they log on? Wi–Fi usage and behavior while attending National Basketball Association games. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 10, 2: 207–226, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y., and X. Han. 2019. Research on consumers’ protection in advantageous operation of big data brokers. Cluster Computing 22: 8387–8400, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M., R. A. Abumalloh, A. Alghamdi, B. Minaei-Bidgoli, A. A. Alsulami, M. Thanoon, S. Asadi, and S. Samad. 2021. What is the impact of service quality on customers’ satisfaction during COVID-19 outbreak? New findings from online reviews analysis. Telematics and Informatics 64. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., T. P. Connerton, and H.-J. Kim. 2019. The rediscovery of brand experience dimensions with big data analysis: Building for a sustainable brand. Sustainability (Switzerland) 11, 19. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.-V., and A. Bara. 2020. Setting the Time-of-Use Tariff Rates with NoSQL and Machine Learning to a Sustainable Environment. IEEE Access 8: 25521–25530, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.-V., A. Bâra, B. G. Tudorică, M. I. Călinoiu, and M. A. Botezatu. 2021. Insights into demand-side management with big data analytics in electricity consumers’ behaviour. Computers and Electrical Engineering 89. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkcan, S., N. Kasap, A. Tanaltay, and M. Ozdinc. 2019. Analysis of tweets about football: 2013 and 2018 leagues in Turkey. Behaviour and Information Technology 38, 9: 887–899, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, J. M. Tetzlaff, E. A. Akl, S. E. Brennan, R. Chou, J. Glanville, J. M. Grimshaw, A. Hróbjartsson, M. M. Lalu, T. Li, E. W. Loder, E. Mayo-Wilson, S. McDonald, and D. Moher. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-S., and S.-L. Chen. 2023. Mystery of Big Data: A Study of Consumer Decision-Making Behavior on E-Commerce Websites †. Engineering Proceedings 38, 1. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W., J. Ko, S. Kim, and E. Ko. 2022. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic upon fashion consumer behavior: Focus on mass and luxury products. ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL OF MARKETING AND LOGISTICS 34, 10: 2149–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E., S. Giglio, and C. Dennis. 2019. Making sense of consumers’ tweets: Sentiment outcomes for fast fashion retailers through Big Data analytics. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 47, 9: 915–927, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindado, E., and R. Barrena. 2021. Using Twitter to explore consumers’ sentiments and their social representations towards new food trends. British Food Journal 123, 3: 1060–1082, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar, Y., R. Suguna, S. Ghosh, and K. Neha. 2019. Semantic web mining in retail management system using ANN. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 8, 2 Special Issue 11: 3547–3554, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C., J. Chen, and B. Stantic. 2020. Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C. M. Q., D. J. Martins, F. Serra, R. Lam, P. J. S. Cardoso, M. B. Correia, and J. M. F. Rodrigues. 2017. Framework for a hospitality big data warehouse: The implementation of an efficient hospitality business intelligence system. International Journal of Information Systems in the Service Sector 9, 2: 27–45, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, E., R. Alejo, C. Castorena, F. J. Isidro-Ortega, and E. E. Granda-Gutierrez. 2020. Data Sampling Methods to Deal With the Big Data Multi-Class Imbalance Problem. APPLIED SCIENCES-BASEL 10, 4: 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G.-A., A. Nasridinov, H. Rah, and K.-H. Yoo. 2020. Forecasts of the amount purchase pork meat by using structured and unstructured big data. Agriculture (Switzerland) 10, 1. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D., I. Kamperos, and P. Reklitis. 2021. Estimating Risk Perception Effects on Courier Companies’ Online Customer Behavior during a Crisis, Using Crowdsourced Data. SUSTAINABILITY 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasquete, N. 2017. A common data representation model for customer behavior tracking. REVISTA ICONO 14-REVISTA CIENTIFICA DE COMUNICACION Y TECNOLOGIAS 15, 2: 55–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R., F. Catalá-López, E. Aromataris, and C. Lockwood. 2021. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Systematic Reviews 10, 1: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senavirathne, N., and V. Torra. 2020. On the Role of Data Anonymization in Machine Learning Privacy. Edited by G. J. Wang, R. Ko, M. Z. A. Bhuiyan and Y. Pan. In 2020 IEEE 19TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON TRUST, SECURITY AND PRIVACY IN COMPUTING AND COMMUNICATIONS (TRUSTCOM 2020). IEEE Computer Soc: pp. 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D., and Y. Yoo. 2023. Improving Shopping Mall Revenue by Real-Time Customized Digital Coupon Issuance. IEEE Access 11: 7924–7932, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L., A. Ariza-Montes, M. Nader, A. Sianes, and R. Law. 2021. Exploring preferences and sustainable attitudes of Airbnb green users in the review comments and ratings: A text mining approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29, 7: 1134–1152, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P., and T. Li. 2017. Consumers repurchasing behavior research based on big data environment. Agro Food Industry Hi-Tech 28, 3: 1206–1210, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya, Y., and H. Tanaka. 2018. A Statistical Analysis Between Consumer Behavior and a Social Network Service: A Case Study of Used-Car Demand Following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011. REVIEW OF SOCIONETWORK STRATEGIES 12, 2: 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhyar, S., A. Dehkhodaei, and B. Amiri. 2022. Toward customer-centric mobile phone reverse logistics: Using the DEMATEL approach and social media data. Kybernetes 51, 11: 3236–3279, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E. S., H. Hassani, and D. Ø. Madsen. 2020. Big Data in fashion: Transforming the retail sector. Journal of Business Strategy 41, 4: 21–27, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E. S., H. Hassani, D. Ø. Madsen, and L. Gee. 2019. Googling fashion: Forecasting fashion consumer behaviour using Google Trends. Social Sciences 8, 4. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimović, P. P., C. Y. T. Chen, and E. W. Sun. 2023. Classifying the Variety of Customers’ Online Engagement for Churn Prediction with a Mixed-Penalty Logistic Regression. Computational Economics 61, 1: 451–485, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., and A. Glińska-Neweś. 2022. Modeling the public attitude towards organic foods: A big data and text mining approach. Journal of Big Data 9, 1. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., and A. K. Singh. 2018. Data Privacy Protection Mechanisms in Cloud. DATA SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 3, 1: 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., and A. Yassine. 2019. Mining energy consumption behavior patterns for households in smart grid. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 7, 3: 404–419, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Comas, J., and J. Domingo-Ferrer. 2016. Big Data Privacy: Challenges to Privacy Principles and Models. DATA SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 1, 1: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M., and J. Zhao. 2022. Behavioral Patterns beyond Posting Negative Reviews Online: An Empirical View. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17, 3: 949–983, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, H. P., N. N. The, T. H. P. Thi, and T. N. Nam. 2019. Evaluating the purchase behaviour of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC MARKETING 27, 6: 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J., Y. Zhang, and C. Zhang. 2018. Predicting consumer variety-seeking through weather data analytics. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 28: 194–207, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. 2022. An Effective Model for Consumer Need Prediction Using Big Data Analytics. JOURNAL OF INTERCONNECTION NETWORKS 22, SUPP02: 2143008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiantian, A. 2022. Data mining analysis method of consumer behaviour characteristics based on social media big data. International Journal of Web Based Communities 18, 3–4: 224–237, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupikovskaja-Omovie, Z., and D. Tyler. 2021. Eye tracking technology to audit google analytics: Analysing digital consumer shopping journey in fashion m-retail. International Journal of Information Management 59. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udugama, I. A., W. Kelton, and C. Bayer. 2023. Digital twins in food processing: A conceptual approach to developing multi-layer digital models. Digital Chemical Engineering 7. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, U., A. Kumar, G. Sharma, S. Sharma, V. Arya, P. K. Panigrahi, and B. B. Gupta. 2024. A systematic data-driven approach for targeted marketing in enterprise information system. ENTERPRISE INFORMATION SYSTEMS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urkup, C., B. Bozkaya, and F. Sibel Salman. 2018. Customer mobility signatures and financial indicators as predictors in product recommendation. PLoS ONE 13, 7. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakova, A., and S. Jankin Mikhaylov. 2020. Big data to the rescue? Challenges in analysing granular household electricity consumption in the United Kingdom. Energy Research and Social Science 64. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatrama, S. 2017. A proposed business intelligent framework for recommender systems. Informatics 4, 4. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepsäläinen, H., J. Nevalainen, S. Kinnunen, S. T. Itkonen, J. Meinilä, S. Männistö, L. Uusitalo, M. Fogelholm, and M. Erkkola. 2022. Do we eat what we buy? Relative validity of grocery purchase data as an indicator of food consumption in the LoCard study. British Journal of Nutrition 128, 9: 1780–1788, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, E., and G. Karpushkin. 2023. Marketing communications in luxury fashion retail in the era of big data. Electronic Commerce Research. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., C. Shen, Y. Cai, L. Dai, S. Gai, and D. Liu. 2023. Consumer culture in traditional food market: The influence of Chinese consumers to the cultural construction of Chinese barbecue. Food Control 143. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., and Y. Zhang. 2021. Using cloud computing platform of 6G IoT in e-commerce personalized recommendation. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEM ASSURANCE ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT 12, 4: 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. 2022. Big Data Mining Method of Marketing Management Based on Deep Trust Network Model. International Journal of Circuits, Systems and Signal Processing 16: 578–584, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., C. B. Sivaparthipan, and P. M. Kumar. 2022. Online shopping behavior analysis for smart business using big data analytics and blockchain security. International Journal of Modeling, Simulation, and Scientific Computing 13, 4. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., L. Kung, and T. A. Byrd. 2018. Big data analytics: Understanding its capabilities and potential benefits for healthcare organizations. TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE 126: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z., Z. Schwartz, J. H. Gerdes, and M. Uysal. 2015. What can big data and text analytics tell us about hotel guest experience and satisfaction? International Journal of Hospitality Management 44: 120–130, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., and G. Piao. 2022. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Enterprise Strategy of Online Consumer Behavior Decision Based on Association Rules and Mobile Computing. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T. 2023. Artificial intelligence and automatic recognition application in B2C e-commerce platform consumer behavior recognition. Soft Computing 27, 11: 7627–7637, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., and P. Chen. 2023. Big data analysis based on the correlation between live-streaming with goods, perceived value and consumer repurchase. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L. 2023. Cluster analysis-based big data mining method of e-commerce consumer behaviour. International Journal of Web Based Communities 19, 1: 53–63, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y., C. Huang, Q. Wang, and B. Hu. 2020. Data mining of customer choice behavior in internet of things within relationship network. International Journal of Information Management 50: 566–574, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., D. Min, and J. Kim. 2020. The use of big data and its effects in a diffusion forecasting model for Korean reverse mortgage subscribers. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12, 3. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D., B. Muthu, and P. Kumar. 2022. Identifying Buying Patterns From Consumer Purchase History Using Big Data and Cloud Computing. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGIES 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., X. Lu, and T. Lu. 2022. Examining the spillover effect of sustainable consumption on microloan repayment: A big data-based research. Information and Management 59, 5. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., J. Wu, and C. Gao. 2022. Consumption Behavior Analysis of E-commerce Users Based on K-means Algorithm. Journal of Network Intelligence 7, 4: 935–942, Scopus. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., J. Priestley, J. Demaio, S. Ni, and X. Tian. 2021. Measuring Customer Similarity and Identifying Cross-Selling Products by Community Detection. Big Data 9, 2: 132–143, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., and Y. He. 2019. Optimal policies for new and green remanufactured short-life-cycle products considering consumer behavior. JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION 214: 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., and M. Wang. 2021. An improved deep forest model for prediction of e-commerce consumers’ repurchase behavior. PLOS ONE 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., T. Lu, and Y. Dai. 2021. Individual Driver Crash Risk Classification Based on IoV Data and Offline Consumer Behavior Data. Mobile Information Systems 2021. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., M. K. Lim, Y. He, and S. Pratap. 2020. What attracts vehicle consumers’ buying: A Saaty scale-based VIKOR (SSC-VIKOR) approach from after-sales textual perspective? Industrial Management and Data Systems 120, 1: 57–78, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukovskiy, Y. L., M. S. Kovalchuk, D. E. Batueva, and N. D. Senchilo. 2021. Development of an algorithm for regulating the load schedule of educational institutions based on the forecast of electric consumption within the framework of application of the demand response. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13, 24. Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Specific Standard Requirements |

| Research database | Web of Science core collection, Scopus |

| Citation indexes | WOS (SSCI, SCIE), Scopus |

| Searching period | January 2012 to December 2023 |

| Language | “English” |

| Searching keywords |

WOS TS = ((“big data” OR “data analytics” OR “data mining” OR “machine learning” OR “predictive analytics”) AND (“consumer behavior” OR “consumer behavior” OR “purchase behavior” OR “buying behavior” OR “shopping behavior” OR “customer behavior”)) SCOPUS TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“big data” OR “data analytics” OR “data mining” OR “machine learning” OR “predictive analytics”) AND (“consumer behavior” OR “consumer behavior” OR “purchase behavior” OR “buying behavior” OR “shopping behavior” OR “customer behavior”)) |

| Subject categories | “Business” “Computer Science Information Systems” “Environmental Sciences” “Management” “Green Sustainable Science Technology” |

| Document types | “Articles” |

| Data extraction | Export with full records and cited references in RIS format |

| Sample size | 371 |

| Categories | Subcategories | Example articles |

| Unstructured data | Marketing research data (e.g., Retailing and Advertising, diet survey data) | (Dubé et al., 2014), (Green et al., 2020) |

| User-generated content (e.g., tweets, reviews of social websites, Google keywords) | (Ozturkcan et al., 2019), (Silva et al., 2020), (Pantano et al., 2019), (de Luca et al., 2019) | |

| Web search data (e.g., Taobao live banding data, TripAdvisor, e-commerce platform, Hadoop cloud computing platform) | (Xu & Chen, 2023), (Giglio et al., 2020), (Xue, 2023), (Wang & Zhang, 2021) | |

| Structured data | Enterprise database (e.g., ICT dataset from airplane, EIS) | (Adler et al., 2022), (Upadhyay et al., 2024) |

| Industry database (revenues of luxury) | (Volkova & Karpushkin, 2023) | |

| Professional database (e.g., genetic data, American Statistical Association DataFest) | (Daviet et al., 2022), (Y. Lee & Kim, 2020) |

| Layers | Subject headings | Example articles |

| Consumption | consumption structure; wildlife consumption; Consumers repurchasing behavior; household electricity consumption; food consumption; vehicle consumers’ buying; sustainable consumption | Guo, L., & Zhang, D. (2019); Li, J., & Hu, Q. (2021); Shang, P., & Li, T. (2017); Ushakova, A., & Jankin Mikhaylov, S. (2020); Vepsäläinen, H., Nevalainen, J., Kinnunen, S., Itkonen, S. T., Meinilä, J., Männistö, S., Uusitalo, L., Fogelholm, M., & Erkkola, M. (2022); Zhou, F., Lim, M. K., He, Y., & Pratap, S. (2020); Ye, Y., Lu, X., & Lu, T. (2022). |

| Patterns | user personality traits; customer behaviour system; Dietary patterns; Consumer Segmentation; Consumer Behavior Characteristics; Psychographic Segmentation; social representations; energy consumption behavior patterns; Negative Reviews Behavioral Patterns; Buying Patterns from Purchase History; Community Detection | Adamopoulos, P., Ghose, A., & Todri, V. (2018); Chen, M., & Xia, Z. (2015); Clark, S. D., Shute, B., Jenneson, V., Rains, T., Birkin, M., & Morris, M. A. (2021); Ehsani, F., & Hosseini, M. (2023); Gan, M., & Ouyang, Y. (2022); Liu, H., Huang, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, K., Hu, X., & Wang, W. (2019); Pindado, E., & Barrena, R. (2021); Singh, S., & Yassine, A. (2019); Sun, M., & Zhao, J. (2022); Ye, D., Muthu, B., & Kumar, P. (2022); Zhang, L., Priestley, J., Demaio, J., Ni, S., & Tian, X. (2021). |

| Attitude (recognition) | Enterprise customer relationship management; public attitude towards organic foods; hotel guest satisfaction; consumer behavior recognition; personalized energy management; Personalized Marketing Strategies; Effective Online Advertising; consumer interest in repair; product recommendation; recommender systems | Li, X. T., & Feng, F. (2018); Singh, A., & Glińska-Neweś, A. (2022); Xiang, Z., Schwartz, Z., Gerdes, J. H., & Uysal, M. (2015); Xie, T. (2023); Fotopoulou, E., Zafeiropoulos, A., Terroso-Sáenz, F., Şimşek, U., González-Vidal, A., Tsiolis, G., Gouvas, P., Liapis, P., Fensel, A., & Skarmeta, A. (2017); Han, M. (2023); Jiménez-Marín, G., Sanz-Marcos, P., Medina, I. G., & Coelho, P. M. F. (2020); Kanavos, A., Iakovou, S. A., Sioutas, S., & Tampakas, V. (2018); Makov, T., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2021); Urkup, C., Bozkaya, B., & Sibel Salman, F. (2018); Venkatrama, S. (2017). |

| Decision | decision tree; Online Consumer Behavior Decision; customer choice behavior in internet of things; consumer purchase intention | Lee, Y., & Kim, D.-Y. (2020); Pai, C.-S., & Chen, S.-L. (2023); Xiao, B., & Piao, G. (2022); Yan, Y., Huang, C., Wang, Q., & Hu, B. (2020); Kiran, P., & Vasantha, S. (2016). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).