1. Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are intricate psychiatric conditions that significantly influence eating behaviors and body image perception [

1]. They have profound effects on the physical and psychological health and performance of athletes [

2]. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), eating and eating behavior disorders (EBD) are characterized by persistent disturbances in eating or related behaviors, leading to impaired food intake or absorption and causing significant physical health or psychosocial functioning impairments [

3]. The DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria Reference Guide [

4] outlines specific criteria for clinical identification of these disorders, which include: i) Anorexia Nervosa (AN): Characterized by restricted energy intake leading to significantly low body weight, an intense fear of gaining weight, and a distorted perception of body weight or shape; ii) Bulimia Nervosa (BN): Defined by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting or excessive laxative use, and iii) Binge Eating Disorder (BED): Involves recurrent episodes of binge eating without subsequent compensatory behaviors.

These conditions, first described by Richard Morton in the 17th and 18th centuries and later defined by William Withey Gull, remain relevant today, particularly in a society where appearance and physical image are often equated with success [

5]. In the sporting context, Marí-Sanchis et al. (2022) highlight that the prevalence of ED is significantly higher among athletes compared to the sedentary population [

2]. The rise of social and media pressures to conform to specific aesthetic ideals exacerbates the risk of ED, particularly among vulnerable groups such as adolescents and female athletes, necessitating a specialized approach to their study and treatment [

4,

6,

7]. Since their initial characterization, ED have been the focus of extensive research, with evolving understanding and diagnostic criteria. Prevalence rates vary, with a study in Gran Canaria (Spain) reporting a risk of ED at 27.42% and an overall prevalence of 4.11% among adolescents aged 12-20 years [

9]. European studies from 2016 indicated that the prevalence of AN ranged from <1% to 4%, BN from <1% to 2%, and BED from 1% to 4% [

10]. By 2018, the overall prevalence of ED was estimated at around 13%, with notable increases in adolescents and young women [

8]. The Spanish Public Health Strategy 2022 reports that ED affects approximately 4-6% of women aged 12-21 years, compared to 0.3% of men [

11].

In Spain, early studies indicated a higher prevalence of ED in women (3.4% to 6.4%) compared to men (0.27% to 1.7%) [

12]. Recent studies by Álvarez-Male et al. [

9] and Rojo-Moreno et al. [

13] in 2015 found similar results, with AN and bulimia prevalence below 1% (ranging from 0.19% to 0.57%) and unspecified ED higher than 3%, with a new case incidence of 2.7% among adolescents. The prevalence of ED in Europe is reported at 2.2% (0.2-13.1%) [

12]. In the sports arena, particularly among women in sports that emphasize thinness or have specific weight categories, the combination of maintaining low body weight and the physical and psychological demands of intensive training can lead to risky eating behaviors [

1]. While aesthetic and endurance sports like gymnastics and figure skating are most commonly associated with high ED rates, team sports such as basketball also present significant risks [

14,

15,

16]. A specific study on female basketball players found that 11% exhibited inappropriate eating attitudes compared to 15% of non-athletes. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it underscores that female basketball players, despite participating in a team sport that does not emphasize extreme thinness, remain at risk for developing ED due to pressures to maintain optimal performance and the influence of coaches and teammates [

7].

ED among adolescents and athletes encompass a broad range of serious physical and psychological health issues that can significantly diminish both quality of life and athletic performance [

12]. These disorders may lead to severe medical complications, including osteoporosis, cardiovascular issues, gastrointestinal problems, and menstrual irregularities, collectively referred to as the female athlete triad. The prevalence of amenorrhea in female athletes participating in sports such as long-distance running, ballet, or figure skating ranges from 25% to 70%, in stark contrast to approximately 5% in the general population [

17]. The interplay of insufficient caloric intake, excessive physical activity, and low body fat can disrupt the normal menstrual cycle, adversely affecting bone health and increasing fracture risk [

1]. These health challenges are often intensified by the adoption of harmful weight control practices, including the misuse of diuretics and laxatives, prolonged fasting, and excessive exercise [

12,

17]. jh

The psychological ramifications of ED are equally significant. Athletes with these disorders frequently experience low self-esteem, distorted body image, and personality traits such as perfectionism [

2]. Additionally, these conditions are linked to a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts. A longitudinal study indicated that athletes exhibiting disordered eating behaviors face a markedly higher risk of injury, suggesting that these behaviors detrimentally impact both mental health [

18] and physical performance [

1,

7].

This study seeks to elucidate the extent of ED in all female players at a specific basketball club in Granada, Spain, in order to provide information to parents, coaches, health professionals, and sports policymakers. By assessing factors such as body composition, eating behaviors, and socio-demographic and sports characteristics, targeted programs can be developed to address ED within this sporting context. Furthermore, this research will contribute to the existing body of literature by underscoring the critical importance of early detection and psychological support in preventing ED among athletes. This study is strongly justified by the crucial need to understand and address the potential risks of eating disorders in young athletes, specifically female basketball players aged 10-18 years in Granada, Spain. Firstly, because of the Importance of ED in the sports population as they have strong adverse health Impacts, such as nutritional deficiencies, hormonal imbalances, cardiovascular problems and bone density loss. These problems can significantly impair the long-term health and well-being of female athletes at the crucial stage of adolescence, a developmental stage prevalent in the study demographic that is particularly vulnerable to the onset of ED due to hormonal changes, social pressures and body image issues.

In addition, ED can lead to decreased energy availability, muscle weakness, concentration and coordination problems, all of which negatively affect athletic performance. In a team sport such as basketball, where physical and mental agility are crucial, ED can hinder individual and team success. On the other hand, ED are often accompanied by anxiety, depression and low self-esteem, which can further affect the performance and quality of life of female athletes. The pressure to excel in sport can exacerbate these psychological problems (1, 2, 17, 18).

Our study further addresses some special considerations for female athletes related to gender-specific vulnerabilities: Female athletes may face specific pressures related to body image and weight control, influenced by social ideals and sport-specific demands (15-18). Despite the growing recognition of ED in female athletes, there is a relative lack of research focused specifically on female athletes in team sports such as basketball. This study addresses this deficiency by providing valuable information on the prevalence and risk factors for ED in this specific population. Futhermore, we focuses on female basketball players aged 10-18 years because this is a critical period of physical and psychological development, and athletes of this age may be especially susceptible to ED as early detection and intervention are essential to prevent long-term health consequences. In addition, female players competing at the national level have special sport-specific demands; although basketball is not traditionally associated with “thin” sports, it is still demanding on athletes' bodies, and concerns about weight and body image may arise.

Finally, with respect to the Local Context we have not focused on a specific club in Granada allows for a specific assessment of the presence of and risk factors for EDs in this community. This provides information that can be used to implement effective prevention and intervention strategies at the local level.

Considering the literature review and the methodological framework we intend to employ, we propose the following research question: Are ED present in the basketball club studied? What is the extent of this presence? Therefore, this is an exploratory study on female players aged 10 to 18 years of the local top-level basketball team in Grenada (Spain), to determine the presence of ED in them during the year 2024. We hypothesize that female athletes within this age group will exhibit a higher prevalence of ED due to the specific demands associated with their sport. The specific aims of this study include: evaluating the body composition of athletes; assessing the eating behaviors of volunteer participants; examining the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants; investigating the influence of competition level on ED prevalence; analyzing the relationship between medical history and ED prevalence; and correlation anthropometric, socio-demographic, sports, medical history, and dietary factors with the overall score of the S-EDE-Q questionnaire.

3. Statistical Analysis

The variables considered in this study were: Age at the time of completing the ques-tionnaires, Anthropometric: Weight (kg), height (m), body mass index z-score, body bioimpedance, where the percentage of body fat (%BF) and muscle mass (kg BM) were measured, Sociodemographic: Place of residence, parental education, socioeconomic status and economic data by residence. [

20] Related to sport: Position played (point guard, shooting guard, small forward, power forward, centre), level of competition (local, regional, national, international), sporting experience (years playing sport), hours spent training per week, medical and psychological history (injuries, illnesses, previous ED, among others).

Qualitative variables were characterized using absolute and relative frequencies, while quantitative variables were summarized with descriptive statistics. For normally distributed variables, the mean and standard deviation were reported; for those that did not meet the normality assumption, the median and interquartile ranges were utilized. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the quantitative variables.

To explore the relationships between various covariates and the overall score obtained from the questionnaire, linear regression models were applied. The assumptions of the regression model were evaluated through visual inspection and the following tests: 1) normality of residuals was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test; 2) heteroscedasticity was examined with the Breusch-Pagan test; and 3) independence of observations was verified using the Durbin-Watson test. Influential observations were identified by calculating Cook's distances.

To determine differences in the overall questionnaire score across strata defined by qualitative variables, Tukey's test was employed to estimate pairwise differences in marginal means. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Additionally, to evaluate the impact of quantitative variables on the overall score, partial derivatives were calculated, and average marginal effects were reported. All estimates included their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, derived using the delta method. This analysis was conducted using the statistical package marginal effects [

21].

To investigate the relationship between mean gross income in euros (€) and the overall questionnaire score, a linear mixed regression model was utilized. In this model, the natural logarithm of mean gross income was included as a fixed effect, while area of residence was treated as a random effect.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at 5% (α = 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 4.4.0.

Institutional Review Board Statement:“The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki, and approved by the Provincial Ethics Committee of Granada (CEIm) of Department of Health and Consumption (Junta de Andalucía, Spain), (protocol code SICEIA-2024-000633, date of approval: 06/06/2024).”

Informed Consent Statement: “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” Where appropriate, parental consent was obtained for participants under 18 years of age.

4. Results

4.1. Anthropometric, Sociodemographic and Sport-Related Characteristics

4.1.1. Anthropometric Characteristics

The anthropometric characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1, where the mean age was 13.3 years old (SD = 2.2), with a large number of them between 12 and 14 years old. Mean weight and mean height were 55.6 Kg (SD = 15.1) and 163.3 cm (SD = 10.3) respectively. Finally, the participants were in a healthy range for both BMI z-score and % BF.

4.1.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Economic Data

Table 2 summarises the educational level of the parents and the socio-economic level of the players. Residence shows that a large percentage of the participants live in Beiro (41.7%) and come from highly educated families, with a university education predominating among fathers (69.4%) and mothers (66.7%).

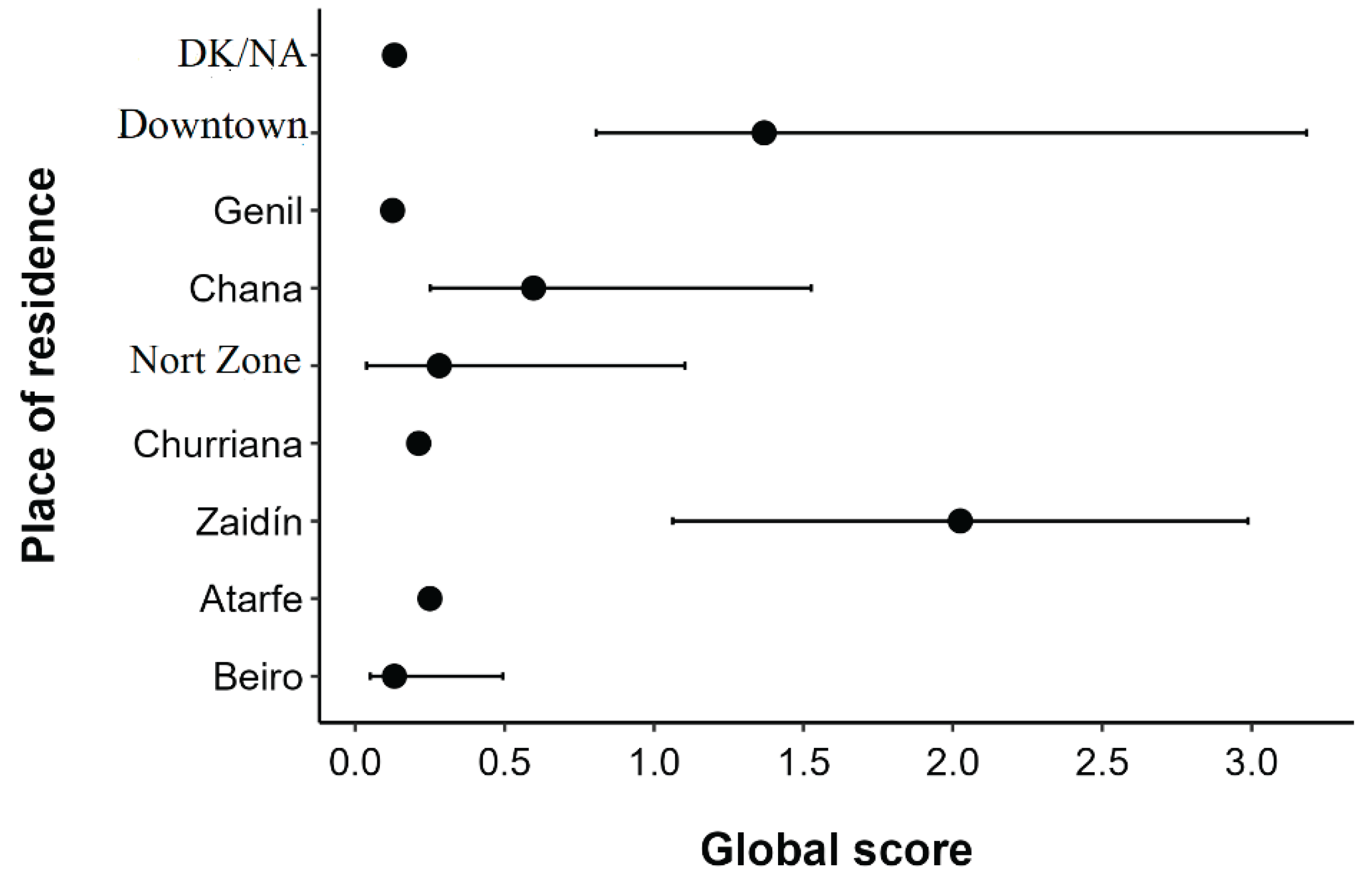

Table 3 shows that the downtown has the highest average gross income (34,848 €) and a median global score of 1.37 (IQR: 0.81 - 3.18), followed by ‘Genil’ (30,181 €) with a median global score of 0.12 (IQR: 0.12 - 0.12), while Beiro has the lowest average gross income (20,354 €) and a median global score of 0.13 (IQR: 0.05 - 0.49). A linear relationship was found between income and score where for every one unit increase in the logarithm of the mean gross income, the overall score increases, on average, by 2.77 points (β = 2.77; 95% CI: 0.35 - 5.17; p=0.031).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the global score according to the place of residence of the participants, showing the medians and interquartile ranges. It can be seen that the Zaidín area has a considerable dispersion in the overall score, while other areas such as Beiro and Churriana show more concentrated and lower scores.

4.1.3. Sport-Related Variables

Table 4 shows the variables related to sport, where most of the players occupy the positions of point guard 30.6% and centre 22.2%, with 50% competing at local level. The average sport experience is 5.2 years (SD = 3.3), and the weekly dedication to training is 7.6 hours (SD = 3.5).

4.2. Scores Obtained on the Subscales of the S-EDE-Q Questionnaire

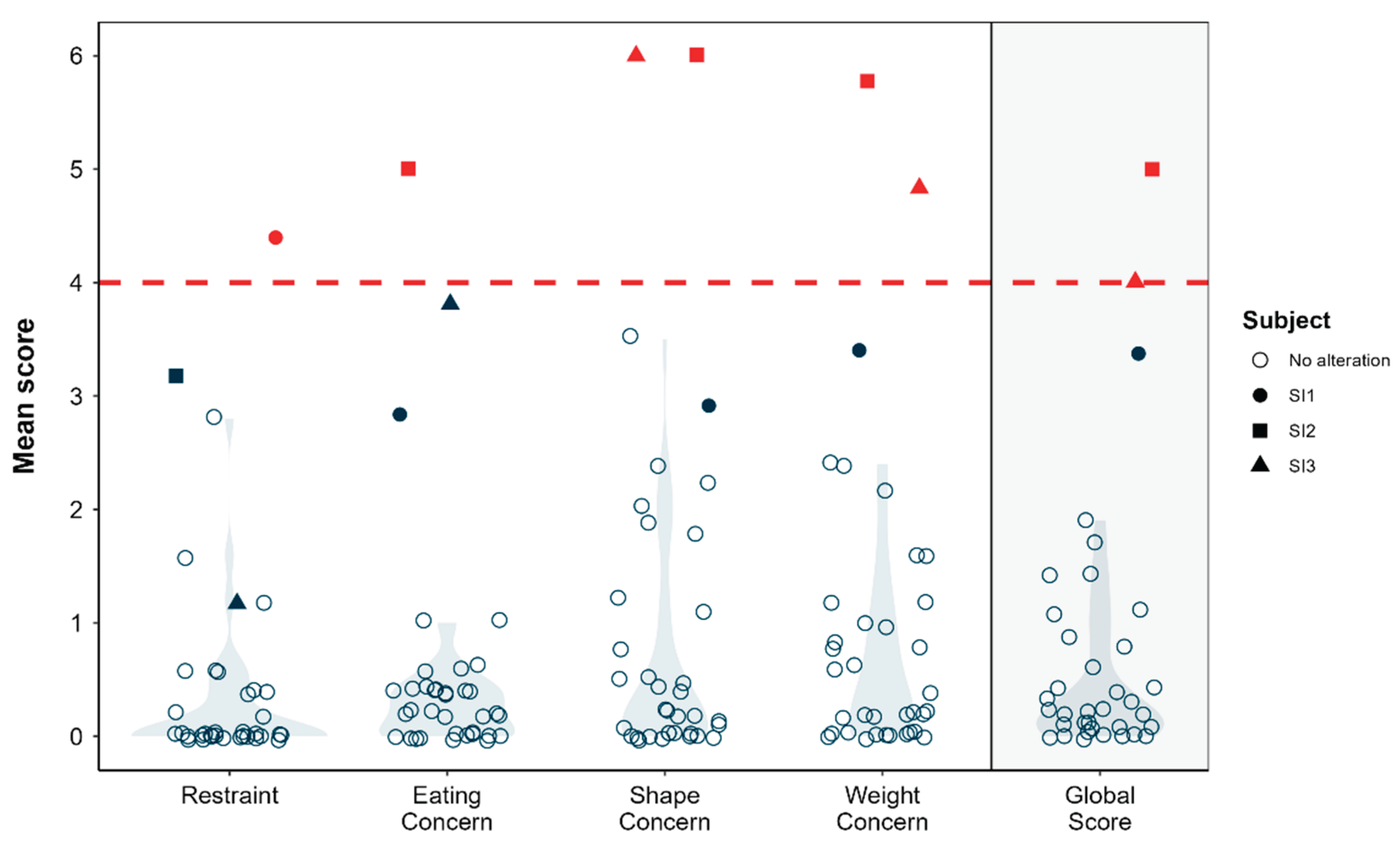

Figure 2 shows the mean scores obtained by the participants in each of the subscales of the S-EDE-Q questionnaire, which are: restraint, eating concern, shape corcern and weight concern, as well as the global score, which is the average of the scores of the four subscales.

Overall, the players scored low on the subscales of the questionnaire, indicating a low overall prevalence of clinically significant eating behaviours and concerns within this sample, however, a small percentage of players showed elevated scores. On the restrain and eating concern subscales, only one participant (2.8%) per subscale exceeded the clinically significant threshold. On the other hand, in the shape corcern and weight conern subscales, greater variability was observed, with means of 0.98 (SD= 1.55) and 0.94 (SD= 1.37) respectively, as well as two participants (5.6%) showing clinically significant scores.

4.3. Relationship Between Sociodemographic Variables and the Global Score of the S-EDE-Q Questionnaire

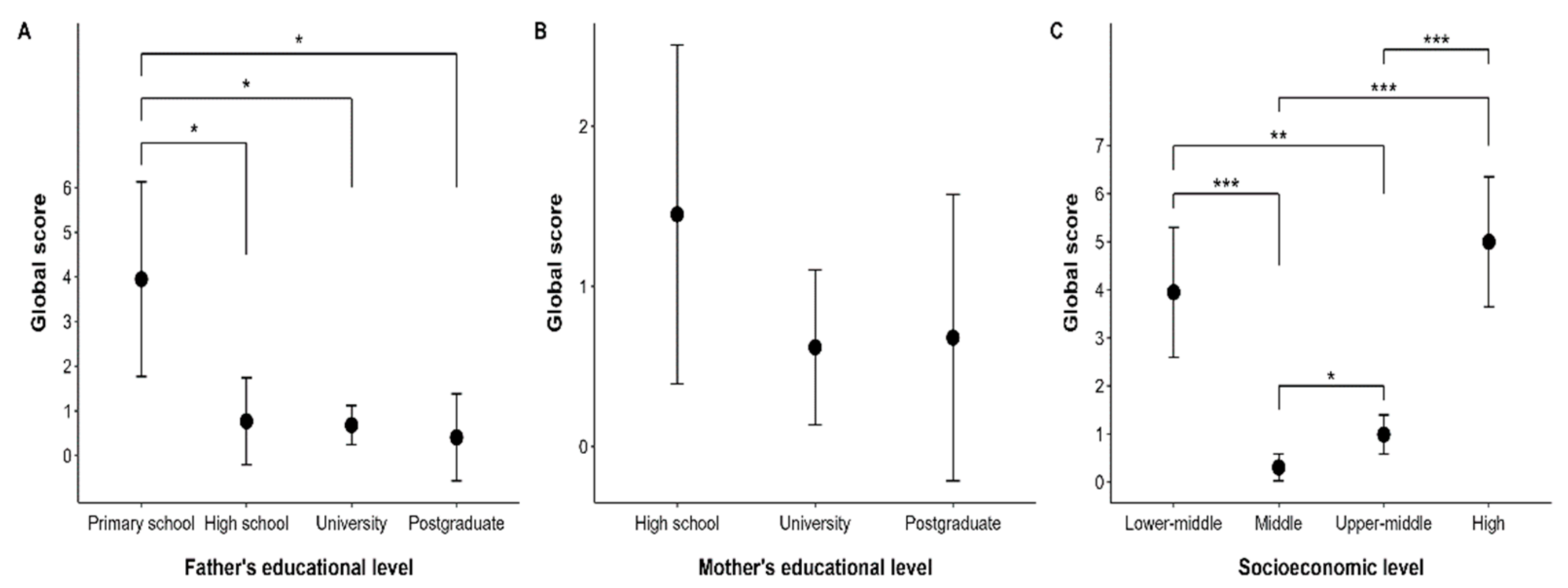

The results shown in

Figure 3 indicate how the global score of the S-EDE-Q questionnaire varied as a function of different socio-demographic factors. Firstly, a significantly higher mean (3.950) is observed for participants whose parents have primary education, with a confidence interval (CI) between 1.771 and 6.129. In comparison, the other higher levels of education, such as secondary school, university and graduate school, have lower means. The differences between primary education and the other educational levels are statistically significant: primary - secondary (3.181 [95% CI: 0.006 - 6.357], p = 0.049), primary - university (3.268 [95% CI: 0.311 - 6.225], p = 0.026), and primary - postgraduate (3.543 [95% CI: 0.367 - 6.718], p = 0.024). On the other hand, comparisons between high school, university and postgraduate showed no significant differences.

Secondly, although no significant differences were found in relation to the mother's educational level, mothers with secondary education had a higher mean of 1.45 [95% CI: 0.391, 2.509], mothers with university education had a mean of 0.62 [95% CI: 0.137, 1.103], and mothers with postgraduate education had a mean of 0.68 [95% CI: -0.214, 1.575].

Finally, with respect to socio-economic status, significant differences in global score scores were observed. The contrast between the ‘lower-middle’ and ‘middle’ conditions showed an estimate of 3.644 (ES = 0.678, 95% CI: 1.806 - 5.481, p < 0.001), while ‘lower-middle’ versus ‘upper-middle’ showed an estimate of 2.959 (ES = 0.693, 95% CI: 1.081 - 4.838, p < 0.001). However, no significant difference was found between the ‘medium-low’ and ‘high’ levels, with an estimate of -1.050. Also, when comparing ‘medium’ and ‘medium-high’, an estimate of -0.685 was observed, while the comparison between ‘medium’ and ‘high’ showed an estimate of -4.694.

4.4. Correlation of Anthropometric Variables and the Overall Score of the S-EDE-Q Questionnaire

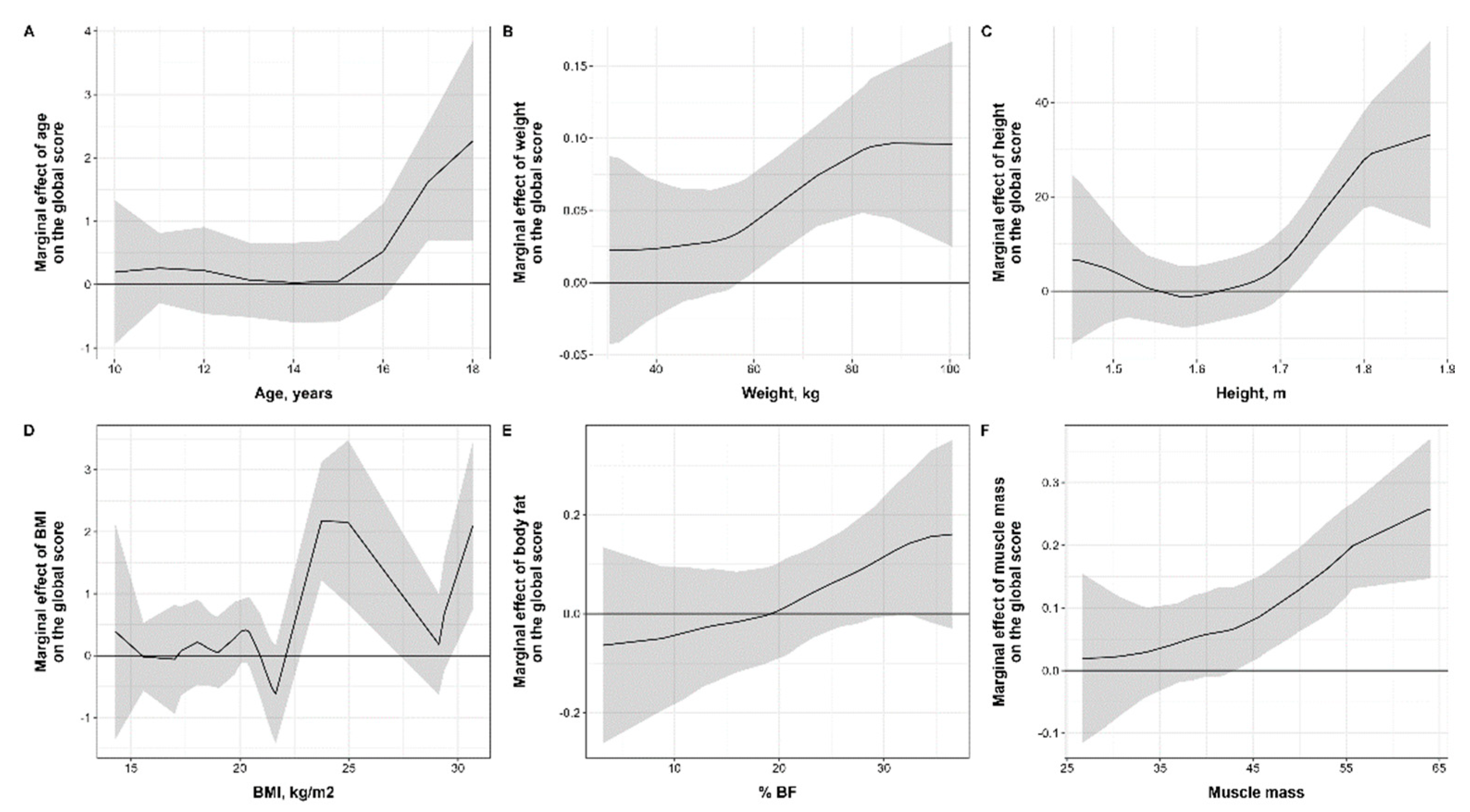

In the analysis of the average marginal effects (MSE) of the anthropometric variables, shown in

Figure 4, significant relationships are observed between some of them. Age had an MPE of 0.297 (95% CI 0.101 to 0.492, p = 0.003), weight had an effect of 0.040 (95% CI 0.018 to 0.061, p < 0.001), and height had the highest effect at 5.715 (95% CI 2.773 to 8.657, p < 0.001). BMI had a significant MPE of 0.244 (95% CI 0.063 to 0.424, p = 0.008), as did % WC which had an effect of 0.051 (95% CI -0.003 to 0.105, p = 0.063), but this did not reach statistical significance. Finally, MM had a significant effect of 0.078 (95% CI 0.048 to 0.109, p < 0.001).

4.5. Relationship Between Sport-Related Characteristics and the Overall Score in the S-EDE-Q Questionnaire

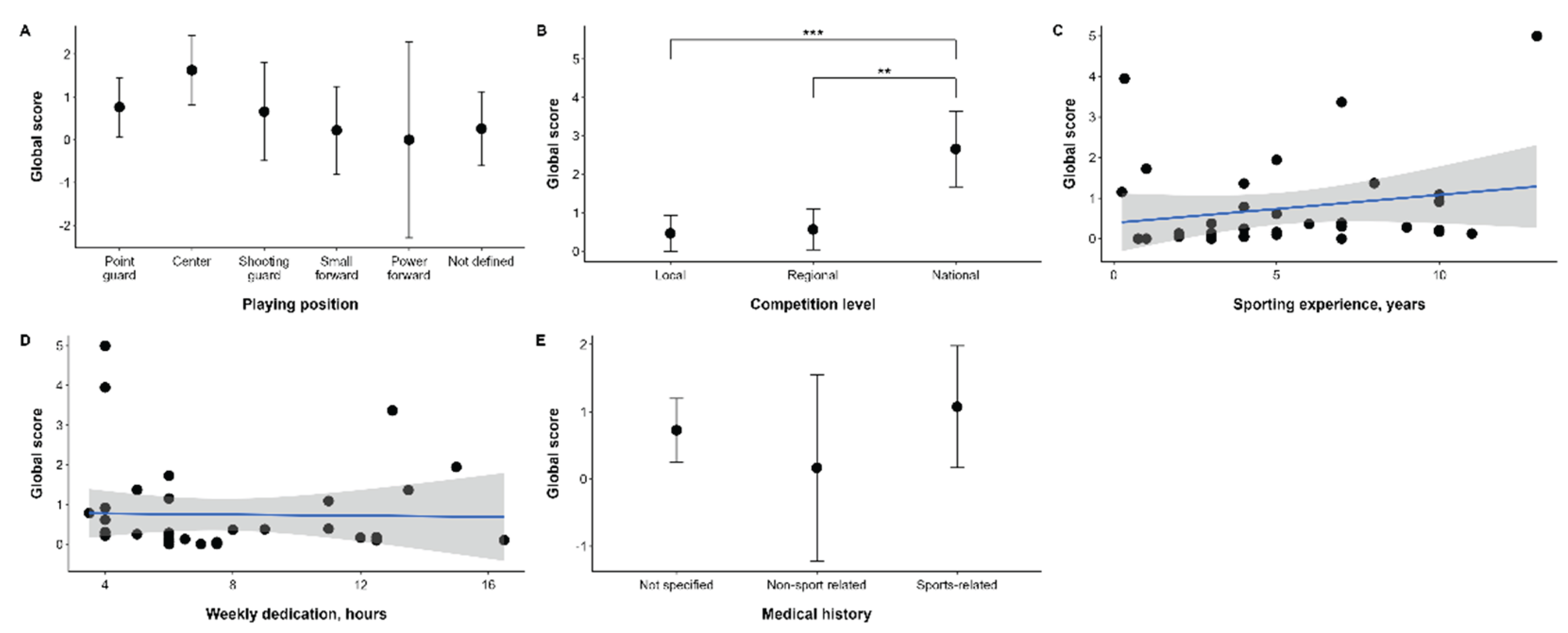

The corresponding results of the sport-related variables such as playing position, competition level, sport experience, weekly training time and medical history are presented in detail in

Figure 5.

The overall score of the questionnaire varied according to playing position, with players occupying the centre position having the highest mean (1.624) with a 95% confidence interval between 0.814 and 2.434, in contrast to players occupying the point guard position, who had a mean of 0.761 (95% CI: 0.070 to 1.452), while point guards, forwards and players without a defined position had a lower overall score of 0.656 (95% CI: -0.489 to 1.802), 0.220 (95% CI: -0.805 to 1.245) and 0.258 (95% CI: -0.608 to 1.124) respectively. Finally, the power forward position showed no significant variability (0.000, 95% CI -2.291 to 2.291).

In relation to the level of competition, significant differences were observed between the different levels, with players competing at the national level having a significantly higher mean overall score (2.663) (95% CI: 1.677, 3.648) compared to those competing at the regional (0.565) (95% CI: 0.038, 1.092) and local (0.463) (95% CI: -0.001, 0.928) levels. Comparisons between local and national (p < 0.001) and between regional and national (p = 0.002) levels show statistically significant differences, while between local and regional levels no significant differences were observed (p = 0.954).

In sport experience, no significant correlation was found between these two factors (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.258, p = 0.128). Also, the weekly dedication in training hours shows a negative correlation with the overall score, although it is not significant (Spearman correlation coefficient = -0.137, p = 0.425).

Finally, female players with a sport-related medical history had a higher mean of 1.073 (95% CI: 0.167, 1.979) compared to those with no medical history 0.726 (95% CI: 0.256, 1.196) and those with a non-sport-related medical history 0.167 (95% CI: -1.217, 1.551).

4.6. Behavioural Results of the S-EDE-Q Assessment

Based on the S-EDE-Q questionnaire, dietary and exercise behaviours were further analysed, with the relevant results presented in

Table 5.

It was observed that 11.1% of the participants reported some form of dietary restriction, although none did so on a regular basis. On the other hand, with regard to any objective binge episodes, 41.7% of the participants reported having experienced at least one episode, with 78.9% of the participants confirming this behaviour in the group that responded. In addition, 16.7% of participants in the total sample reported episodes of any subjective binge episode, 66.7% of which occurred regularly. Any self-induced vomiting behaviours were less frequent, reported by 5.6% of participants, while any laxative and diuretic misuse was reported by 2.8% of participants in each case. Finally, Any excessive exercise was observed in 13.9% of the participants, with 62.5% occurrence in the individual responses.

Regarding habitual behaviours, no regular dietary restraint was observed among participants, however, 13.9% reported regular objective binge episodes, and 16.7% reported regular subjective binge episodes. Regular self-induced vomiting and regular laxative and diuretic misuse remained at 5.6% and 2.8% respectively. Finally, regular excessive exercise was reported by 5.6% of participants, with 25.0% occurrence in individual responses.

4.7. Preliminary Diagnostic Analysis Based on the Results of the S-EDE-Q Questionnaire and the Criteria of the DSM-5 Manual

A preliminary diagnostic analysis of the participants has been carried out based on the results obtained from the S-EDE-Q questionnaire and the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 manual. The findings for each participant with elevated scores are presented below:

1. Participant: AT19GR

BMI: 21.6 (Normal).

High score (S-EDE-Q Questionnaire): Restraint.

Habitual behaviours:

- Any DR (Any dietary restraint).

- Any OBE (Any objective binge episode).

- Any SBE (Any subjective binge episode).

- Reg OBE (Reg. objective binge episodes, regular objective binge episodes).

- Reg SBE (regular subjective binge episodes, regular subjective binge episodes).

Diagnostic criteria according to the DSM-5 manual: Given that she presents regular episodes of binge eating without compensatory behaviours, it could be considered a diagnosis of AT.

2. Participant: AT25GR

BMI: 25.0 (overweight).

High score (S-EDE-Q questionnaire): Shape concern, weight concern and Global score.

Habitual behaviours:

- Any DR (Any dietary restraint, any dietary restraint).

- Any OBE (Any objective binge episode).

- Any LAX (Any laxative misuse episode, any laxative misuse).

- Reg OBE (regular objective binge episodes).

- Reg LAX (regular laxative misuse episodes).

Diagnostic criteria according to DSM-5: The combination of regular binge eating and laxative use suggests a diagnosis of BN.

3. Participant: AT33GR

BMI: 30,7 (Obesity type I)

High score (S-EDE-Q questionnaire): Eating concern, shape concern, weight concern and global score.

Habitual behaviours:

- Any DR (Any dietary restraint, any dietary restraint).

- Any OBE (Any objective binge episode).

- Any SBE (Any subjective binge episode, any subjective binge episode).

- Any SIV (Any self-induced vomiting episode, any self-induced vomiting).

- Any LAX (Any episode of laxative misuse, any laxative misuse).

- Any DIUR (Any episode of diuretic misuse, any diuretic misuse).

- Reg OBE (regular objective binge episodes).

- Reg SBE (regular subjective binge episodes, regular subjective binge episodes).

- Reg SIV (regular self-induced vomiting episodes, regular self-induced vomiting).

- Reg DIUR (regular diuretic misuse, regular diuretic misuse).

- Reg EX (regular episodes of excessive exercise, regular excessive exercise).

Diagnostic criteria according to DSM-5: The presence of these compensatory behaviours together with preoccupations and episodes of binge eating indicates a diagnosis of BN.

5. Discussion

The aim of this exploratory study was to evaluate the presence of eating disorders in women aged 10 to 18 years from a high-level basketball club in Granada, Spain. The research focused on assessing not only the risk of ED but also the presence of confirmed cases. In addition, body composition, eating behaviors, sociodemographic and sporting characteristics were analyzed.

Mean scores on the S-EDE-Q questionnaire were generally low. 8.4% of the participants showed risk of ED; 2.8% exceeded the thresholds for dietary restraint and preoccupation with food; 5.6% exceeded the thresholds for preoccupation with figure and weight. Older age correlated with higher ED symptoms, Higher BMI z-score correlated with higher ED risk, lower educational level correlated with higher ED risk. National level players showed a higher risk of ED than regional or local players, players playing in the pivot position had the highest mean scores, indicating a higher risk, a history of sports-related medical problems correlated with a higher risk of ED. 11.1% reported dietary restriction, 41.7% reported objective over-eating episodes, 16.7% reported subjective overeating episodes, 5.6% reported self-induced vomiting, 2.8% reported laxative and diuretic use, 13.9% reported excessive exercise. However, three participants exhibited high scores on specific subscales, indicating an 8.4% risk for ED. In the dietary restraint and preoccupation with eating subscales, only one participant (2.8%) surpassed the significant threshold, whereas in the subscales related to preoccupation with shape and weight, two participants (5.6%) achieved clinically significant scores.

These results align with Michou and Costarelli (2011) found that 11% of female basketball players displayed disordered eating attitudes, compared to 15% in the general non-athletic population [

6]. Similarly, Bratland-Sanda and Sundgot-Borgen (2013) [

14] reported elevated presence rates of ED in aesthetic and endurance sports, reaching as high as 45%, while team sports like basketball exhibited relatively lower yet still significant rates. Research by Tafà et al. (2016) [

22] and Werner et al. (2013) [

23] has demonstrated that aesthetic sports, often referred to as "leanness sports," are associated with a higher presence of weight control concerns and behaviors.

Epidemiological data from the DSM-5 manual indicate that ED are most commonly observed during adolescence or early adulthood [

3]. In our study, the mean age of participants was 13.3 years (SD = 2.2), which is consistent with ages reported in prior research ranging from 11 to 30 years [

8,

16,

22]. The observed BMI z-score was within normal limits in 77.8% of participants. This finding corroborates the study by Kontele et al. (2022) [

7], which evaluated female adolescent gymnasts in Greece, revealing that both competitive and non-competitive gymnasts had an average BMI within the normal range for this demographic.

Mean scores on the S-EDE-Q questionnaire were generally low. 8.4% of the participants showed risk of ED; 2.8% exceeded the thresholds for dietary restraint and preoccupation with food; 5.6% exceeded the thresholds for preoccupation with figure and weight. Older age correlated with higher ED symptoms, Higher BMI z-score correlated with higher ED risk, lower educational level correlated with higher ED risk. National level players showed a higher risk of ED than regional or local players, players playing in the pivot position had the highest mean scores, indicating a higher risk, a history of sports-related medical problems correlated with a higher risk of ED.

Regarding parental education and socioeconomic status, participants whose parents had only a primary school education exhibited significantly higher mean global scores on the questionnaire compared to those whose parents attained higher educational levels (university or postgraduate). While some studies suggest that eating disorders can affect individuals across all genders, ages, sexual orientations, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds, lower socioeconomic status is frequently linked to a higher incidence of compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa [

25].

A higher levels of educational attainment, along with factors related to body image and the use of appearance-oriented social media, are associated with an increased risk of exhibiting symptoms of ED [

26] . Additionally, parental education has been linked to healthier eating habits, with findings suggesting that adolescents with well-educated parents tend to consume more fruits and vegetables while avoiding energy-dense foods, thereby promoting a healthier diet [

27]. Furthermore, other studies have highlighted that family dynamics, including the quality of communication and cohesion, can serve as either protective or risk factors for maladaptive eating behaviors in adolescents [

10,

22].

Regarding age, our study found a significant correlation with the overall score, suggesting that as adolescent girls mature, there is a greater likelihood of presenting symptoms of ED. This aligns with the findings of Campbell and Peebles (2014) [

28], who reported that the prevalence of anorexia nervosa (AN) peaks between the ages of 13 and 18, while bulimia nervosa (BN) is more frequently observed in individuals aged 16 to 17. Adolescence is thus recognized as a critical period for the onset of ED [

29]. Although ED can affect individuals across all age groups, adolescence represents a heightened period of vulnerability for the development of these disorders [

14,

15,

29,

30].

Similarly, weight, height, and BMI exhibited marginally significant effects. Specifically, our findings regarding weight are consistent with previous research indicating a correlation between weight and the manifestation of ED symptoms. Higher body weight may contribute to increased body dissatisfaction, thereby elevating the risk of developing ED [

8]. Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that height dissatisfaction may be correlated with body dissatisfaction and the pursuit of thinness and muscularity, which may further influence the development of eating disorders [

31].

The BMI z-score results from this study align with existing literature, which identifies BMI z-score as a significant predictor of ED, demonstrating that a higher BMI is associated with elevated scores on the global assessment. Prior studies have indicated that both BMI and a high perceived BMI can lead to unhealthy behaviors [

8,

32]. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution; Borowiec et al. (2023) [

33] emphasize that while BMI is relevant to the risk of ED, its impact should be considered alongside other factors, such as body satisfaction and the type of sport engaged in. Moreover, many studies supporting this association have predominantly focused on male populations, which may reflect existing gender norms. Although this observation may be speculative, it is crucial for future research to explicitly address this issue [

15].

In terms of body fat percentage (%BF), while it did not achieve statistical significance, a trend was observed suggesting a potential association with the risk of developing atypical eating behaviors. According to Marí-Sanchis et al. [

2], factors such as rigorous weight assessments, body composition pressures, coach expectations, and public exposure of results may trigger such behaviors, although these influences can vary depending on the specific activity and sport [

15,

24]. Lastly, muscle mass (MM) demonstrated a significant effect, underscoring the importance of muscle mass in shaping body image perceptions and the risk of ED [

2,

16].

In this study, the overall scores from the S-EDE-Q questionnaire varied based on playing position, with female pivot players exhibiting the highest mean scores, indicating an elevated risk of eating and body image disorders (EBD). While there is a lack of research specifically analyzing the relationship between playing positions and EBD, existing literature on male team sports suggests that participation in team sports may heighten concerns about weight gain and food intake, thereby increasing the likelihood of developing EBD [

34]. Additional studies have identified sport-specific risk factors, such as early specialization in training, injuries, frequent weight management, and dietary practices, which may render athletes more susceptible to these disorders [

14].

Moreover, significant differences in overall scores were observed based on the level of competition, with national-level players reporting significantly higher mean scores compared to their regional and local counterparts. Teixidor-Batlle et al. (2021) identified the level of competition as a potential risk factor for eating disorders, noting that weight-related pressures from coaches and teammates, as well as uniform requirements, tend to intensify with increased competition levels across various sports. However, athletes competing at higher levels may also benefit from enhanced professional and psychological support to cope with stress and anxiety, potentially reducing the risk of developing eating disorders [

35]. Kampouri et al. (2019) [

32] found that elite female team athletes exhibited eating behaviors similar to those in individual sports, with female water polo players displaying the most significant changes in eating habits and body image compared to female volleyball and basketball players. This discrepancy may be attributed to the greater body exposure in water polo and the heightened pressure to achieve elite performance in this discipline.

Regarding sports experience and weekly training commitment, no significant correlation was found with the overall scores, suggesting that dedication to sport may serve as a protective factor by enhancing mood and self-esteem [

24]. However, various studies indicate that athletes are at an increased risk of developing eating disorders, with this risk varying according to the type of sport practiced. Key factors include the age at which training begins, the intrinsic demands of each sport—particularly those that emphasize strict weight control—the influence of the sporting environment, and pressures related to weight loss and injuries [

2]. Borowiec et al. (2023) highlighted that early initiation of sports training or elite athletic status may be linked to the development of eating disorders, suggesting that factors such as age, competition level, and training history are likely interconnected and play a critical role in this context [

33].

Additionally, female athletes with a history of sport-related medical issues reported higher mean overall scores, indicating that injuries and other health problems may be significant risk factors. Previous research has shown that athletes with injury histories often experience increased concerns about their weight and body shape, driven by physical limitations and the necessity to maintain athletic performance [

14].

11.1% of participants reported some form of dietary restriction (Any DR), although none engaged in this behavior consistently. This finding aligns with existing literature, which suggests that dietary restriction is a prevalent practice among athletes aiming to enhance performance or maintain a specific body image [

14,

16]. Ghoch et al. (2013) [

36] indicate that individuals often evaluate themselves based on their body shape, weight, and food control, adhering to specific rules regarding when, what, and how much to eat. Such practices can lead to a decline in both sports performance and overall health, even when dietary restrictions are not applied regularly.

Furthermore, 41.7% of participants reported experiencing at least one objective overeating episode (Any OBE), with 78.9% of these individuals confirming that such behavior occurred regularly. In contrast, subjective overeating episodes (Any SBE) were reported by 16.7% of participants, with 66.7% indicating that these episodes occurred frequently. Both objective and subjective overeating episodes serve as warning signs, as they are associated with an elevated risk of developing eating disorders (ED) and can negatively impact sports performance. This is consistent with studies that document a high prevalence of these behaviors among athletes facing intense competitive pressure, where concerns about food, body shape, and weight often lead to increased dietary restrictions, thereby heightening the risk of overeating or binge eating [

14,

24,

32,

36]. Marí-Sanchis et al. (2022) [

2] note that dietary restrictions, when combined with purging behaviors and fluid intake alterations, can impair athletes' concentration, coordination, and emotional well-being, while also increasing the risk of injury.

Self-induced vomiting behaviors (Any SIV) were reported by 5.6% of participants, while the use of laxatives and diuretics (Any LAX and Any IUD) was noted in 2.8% of each case. These findings are consistent with research on aesthetic sports, where such behaviors are linked to heightened dietary restrictions and excessive exercise, particularly among female athletes, who exhibit a higher prevalence of ED compared to their male counterparts [

34,

37].

Regarding excessive exercise (Any EX), 13.9% of participants reported engaging in this behavior, with 62.5% indicating that it occurred regularly. Excessive exercise is recognized as a potential trigger for eating disorders, as overtraining can lead to significant caloric deficits, creating a psychological or biological environment conducive to the development of ED [

17]. While often perceived as a demonstration of commitment to the sport, excessive exercise can result in injuries, chronic fatigue, and other health complications if not managed appropriately [

15,

17].

The surrounding environment also plays a crucial role; coaches are frequently viewed as authorities on sports, nutrition, and weight management, and their comments can exert pressure on athletes regarding their weight and body image [

14,

35,

36,

37]. Additionally, discussions about weight among teammates, along with critical remarks from peers and parents, can contribute to significant concerns about body image [

14,

35]. These findings suggest that, although the prevalence of extreme eating behaviors is not alarmingly high, a notable subset of female players engages in risky behaviors. These diagnoses highlight the diversity and severity of eating disorders that can manifest in athletes, underscoring the necessity for targeted prevention and treatment strategies.

While some studies indicate that sports emphasizing thinness and aesthetics are associated with higher rates of eating disorders [

2,

6,

12,

15,

32,

34,

36,

37], vigilant monitoring is essential for early diagnosis. Issues tend to escalate when dietary practices are not supervised; indeed, it has been noted that inadequate guidance on weight management, rather than merely the coach's directive to lose weight, can precipitate eating disorders [

12,

17].

However, this study is not without limitations, some of which align with those identified in similar research. Firstly, akin to the findings of Iuso et al. [

24], our sample size is relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of our results to the broader population of female basketball players in Granada and other contexts, including varying socioeconomic backgrounds and types of sports. Secondly, as noted by Kontele et al. [

7], Ravi et al. [

16], and Tafà et al. [

22], the cross-sectional design of our study restricts our ability to draw causal inferences, thereby limiting our capacity to assess long-term changes and confining our findings to observational associations.

Additionally, similar to the studies conducted by Ravi et al. [

16], Tafà et al. [

22], and Thompson et al. [

38], our research relied on self-reported data, specifically the S-EDE-Q questionnaire. This reliance may compromise the reliability of our findings due to potential inaccuracies in responses, a common limitation in studies utilizing self-reporting tools. Such tools are susceptible to biases, including self-selection bias [

16], and may not accurately reflect the assessments that a trained professional would derive through direct interviews [

14,

32,

38]. Another significant limitation, shared with the research of Michou and Costarelli [

6] and Ravi et al. [

16], is the absence of a control group. This omission hinders our ability to compare the results from our sample with those of a non-sporting population, emphasizing the necessity for greater diversity in sample populations and the inclusion of appropriate control groups to enhance the generalizability and external validity of the findings [

6,

38].

Finally, as highlighted by Michou and Costarelli [

6], there is a notable lack of targeted research on female athletes, which limits our comprehensive understanding of the impact of eating disorders within this demographic. This underscores the importance of considering gender differences and sport-specific factors in research on eating disorders, as well as the scarcity of studies addressing eating attitudes in team sports.

Looking ahead, future research could benefit from expanding the study to encompass a broader range of sports populations, including various teams from different geographical locations. Such an approach would facilitate a more nuanced comparison across diverse socioeconomic and residential contexts, thereby enhancing our understanding of how these factors influence eating disorders. Furthermore, conducting multiple assessments of the S-EDE-Q questionnaire throughout a sports season could provide insights into potential changes in eating behaviors and body image perceptions in response to training and competition dynamics. This methodology could be enriched by incorporating individual interviews, as recommended by Bratland-Sanda and Sundgot-Borgen [

14] and Teixidor-Batlle et al. [

35], to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to the development of eating disorders in various sporting environments.

Practical Applications: Our study can promote primary prevention of eating disorders by promoting education, fostering a positive body image, and raising awareness among stakeholders to recognize risk factors. Studies of this nature can be useful for understanding the incidence and risk factors in a vulnerable population (young female athletes), as well as for protecting their physical and mental health, preventing the onset of these disorders, facilitating effective recovery, and promoting sustainable and healthy athletic performance.

In addition, we provide specific screening tools to identify athletes at risk of developing eating disorders.

By implementing the findings of similar research, a safer and more supportive sports environment for young athletes can be created.