Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

A. Global Context of Air Pollution

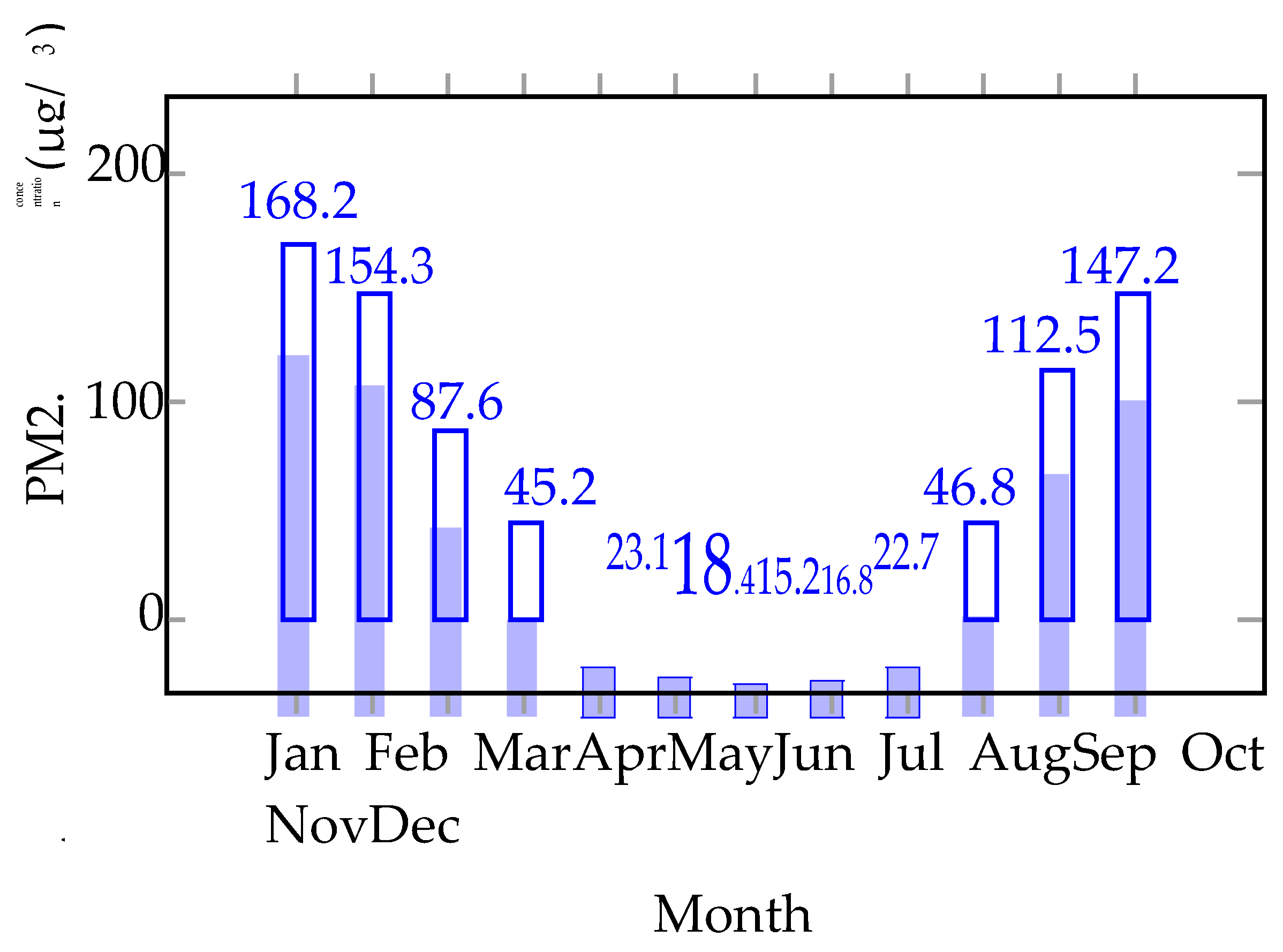

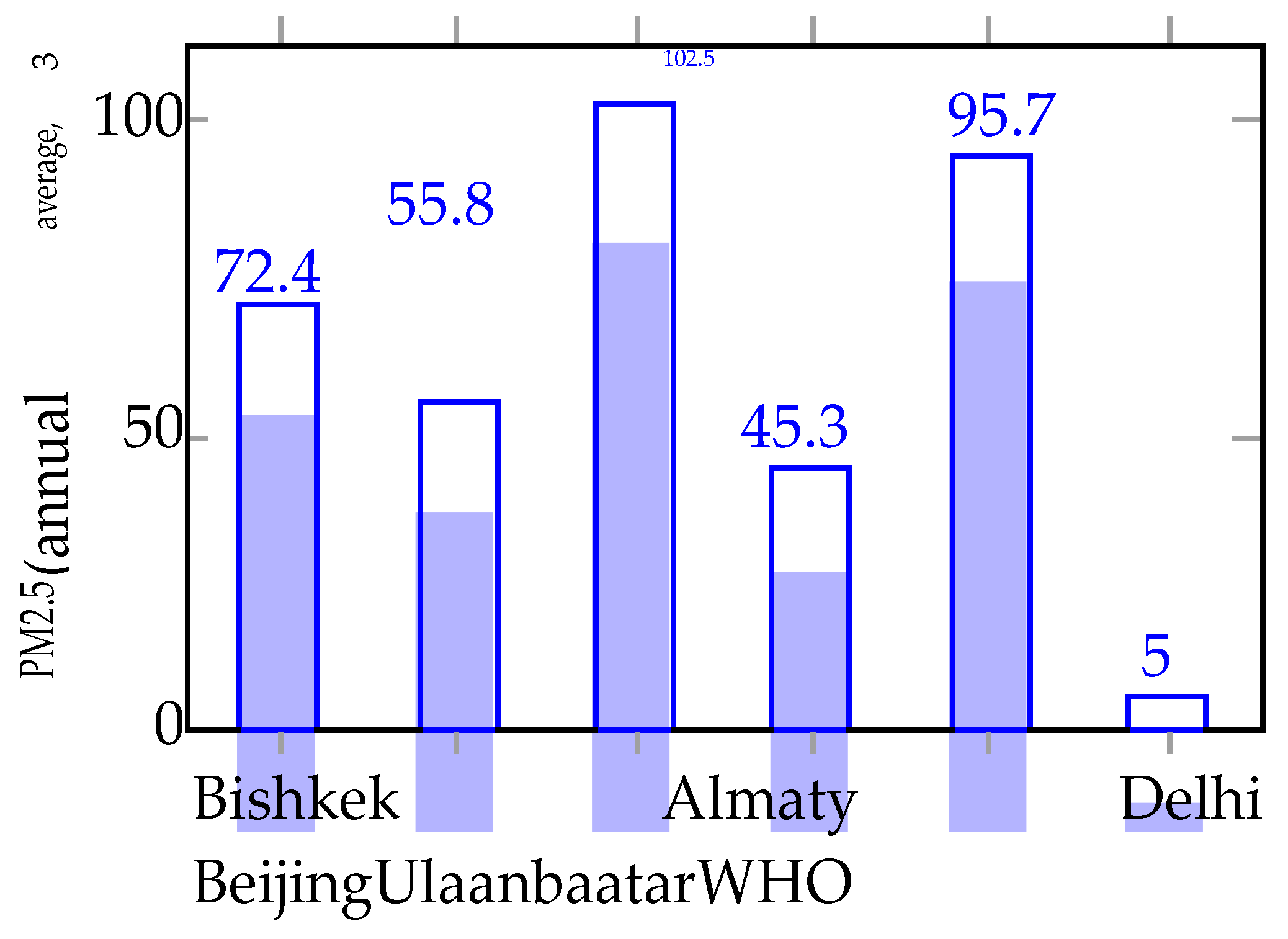

B. Local Context: Air Quality in Bishkek

C. Problem Statement

II. Literature ReviewIndoor Air Quality Management

Window-Integrated Technologies

Patent Landscape

D. Market Analysis of Existing Solutions

| Category | Price Range | Filtration | Energy | Size | Key Limitations |

| (USD) | Efficiency | (W) | (m2) | ||

| Budget Standalone | 50-150 | 70-85% | 30-60 | 0.15-0.25 | Limited coverage, noisy |

| Premium Standalone | 300-800 | 90-99.97% | 40-90 | 0.2-0.4 | High cost, large size |

| HVAC Integrated | 200-1200 | 85-95% | System dependent | None | Requires central HVAC |

| Portable Personal | 30-100 | 60-80% | 5-15 | 0.05-0.1 | Very limited coverage |

Methodology

Research Design

B. User Research and Needs Assessment

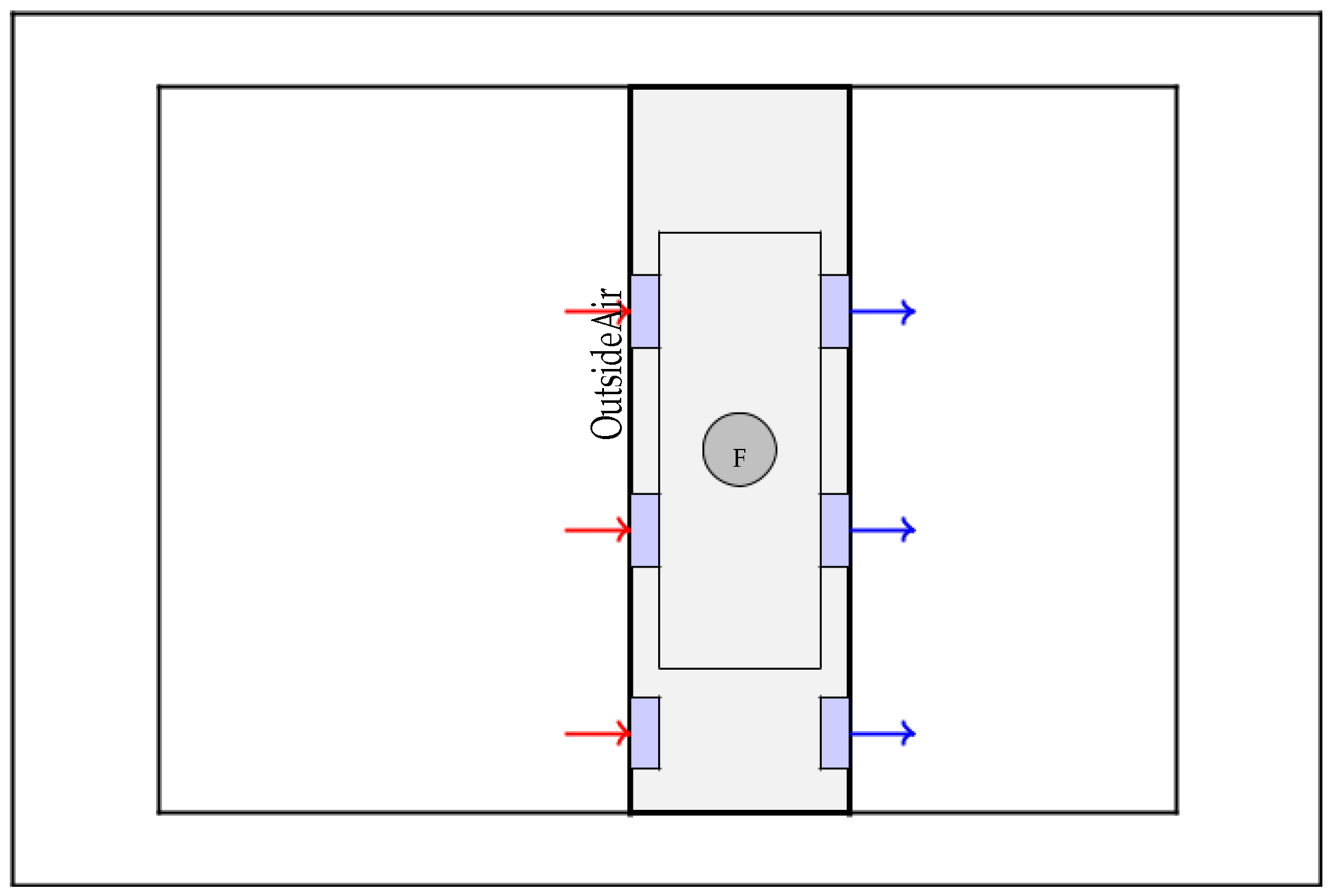

C. Technical Design and Engineering

D. Prototype Development

E. Testing Methodology

IV. Results And Findings

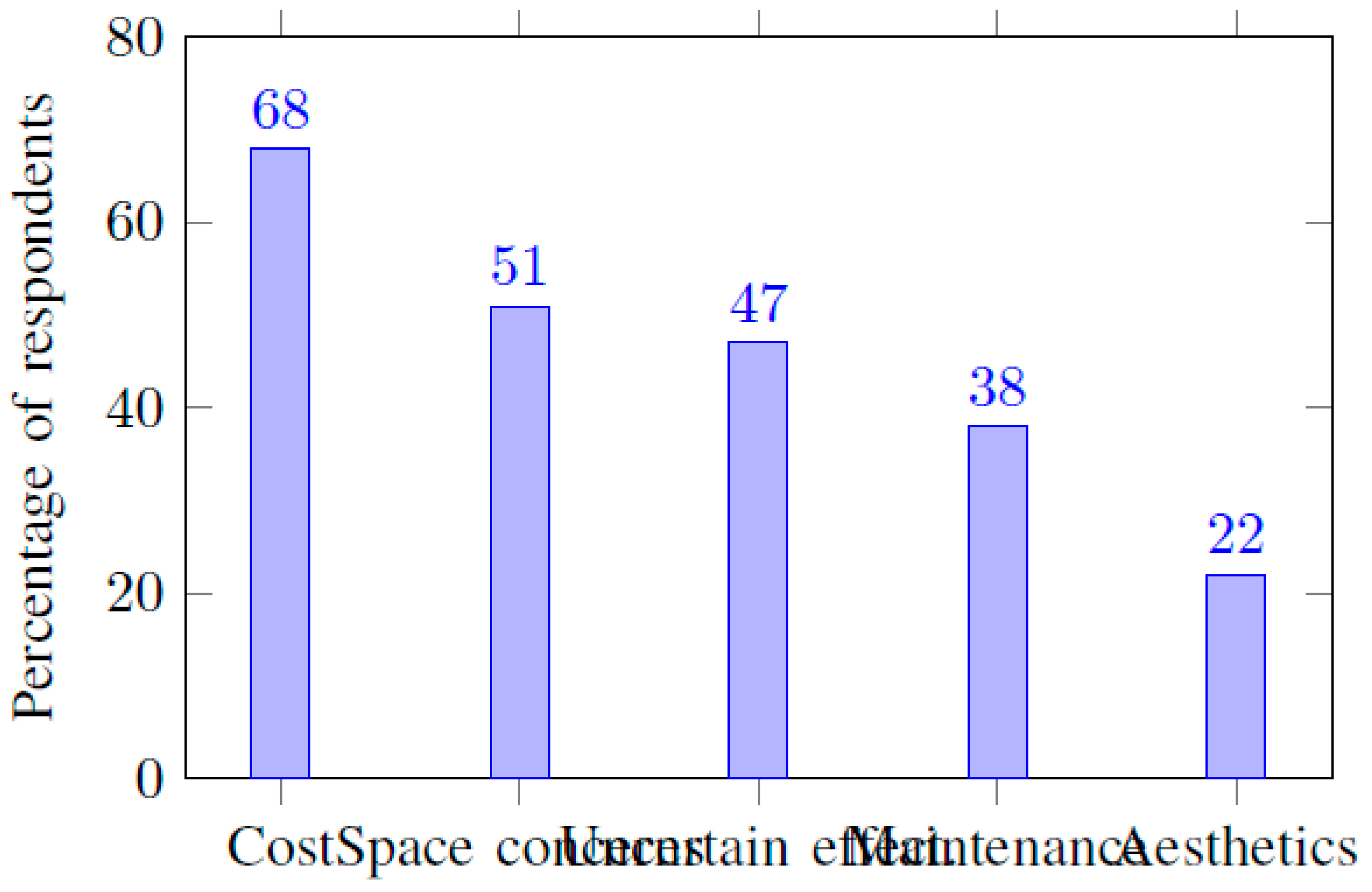

A. User Research Findings

B. Technical Design Results

| Cost Category | Window | Mid-Range | Premium | ||

| System | Standalone | Standalone | |||

| Initial purchase | 6,500 KGS ($77) | 12,600 | KGS ($150) | 42,000 KGS ($500) | |

| Energy (5 years) | 1,890 KGS ($22.50) | 7,560 | KGS ($90) | 10,080 KGS ($120) | |

| Filter replacement | 8,400 KGS ($100) | 14,700 | KGS ($175) | 29,400 KGS ($350) | |

| Total 5-year cost | 16,790 KGS ($200) | 34,860 KGS ($415) | 81,480 KGS ($970) | ||

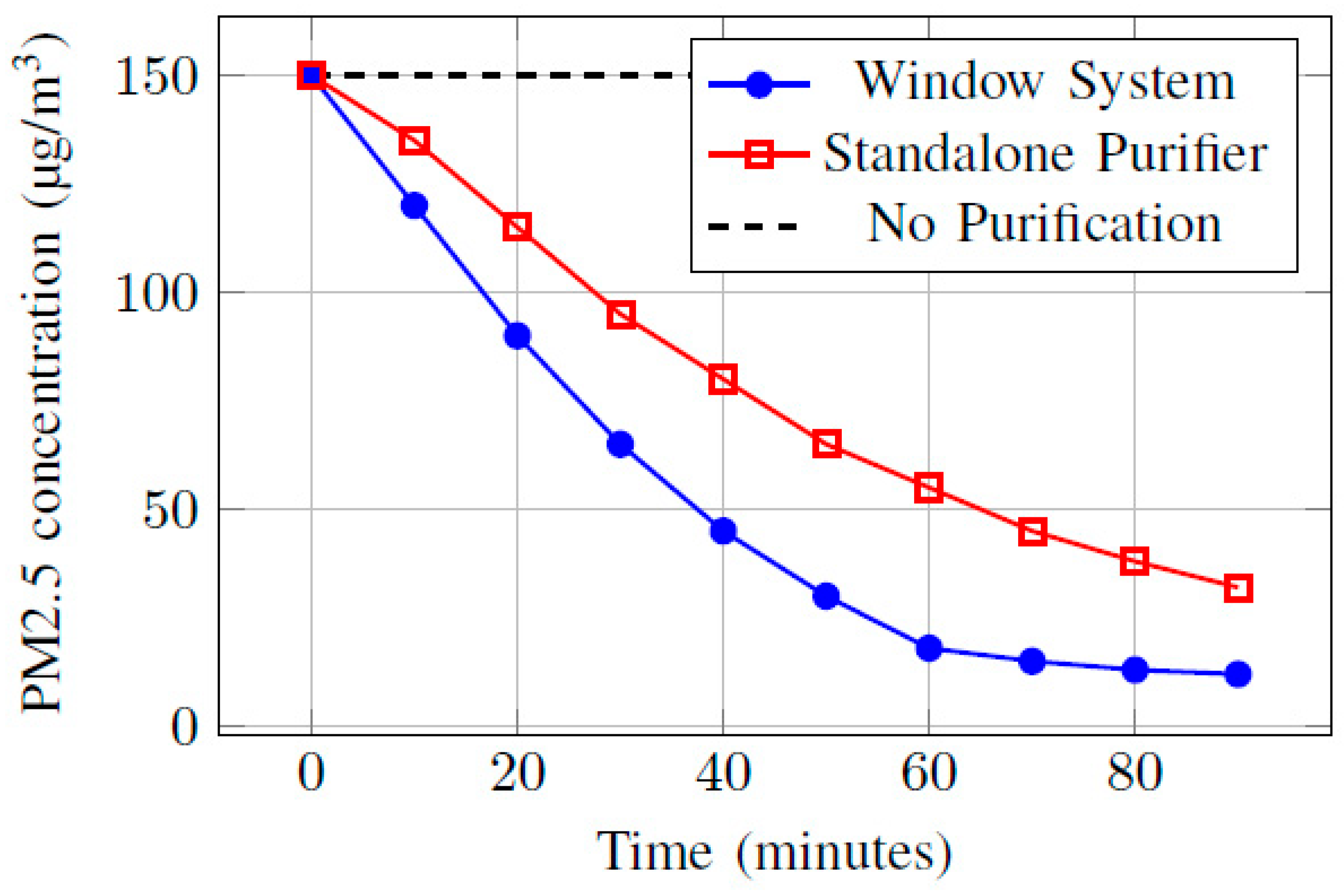

C. Prototype Performance

| Parameter | Specification | Testing Method | |||||

| Dimensions | 120mm (D) × window width × 180mm (H) | Physical measurement | |||||

| Weight | 2.1–3.4kg depending on width | Scale measurement | |||||

| Airflow Rate | 45–75 m3/h (adjustable) | 0.3 m | Anemometer measurement | ||||

| Filtration Efficiency | > 99. | 7% | for particles ≥ | Particle counter analysis | |||

| 3 | |||||||

| CADR | 35–65 m | /h | Standardized CADR testing | ||||

| Power Consumption | 8–17W (operation), < 0.5W (standby) | Power meter measurement | |||||

| Noise Level | 26–38 dB | Sound level meter at 1m | |||||

| Filter Life | Pre-filter: 1–2 months | Accelerated loading tests | |||||

| Main filters: 6–12 months | |||||||

| Operating Temperature | -25°C to +40°C | Climate chamber testing | |||||

| Installation Compatibility | 90% of standard window frames | Field testing | |||||

VI. Implementation Strategy

A. Manufacturing Plan

B. Distribution Strategy

C. Installation and Support

VII. Discussion

A. Key Innovations

VIII. Literature Review

A. Indoor Air Quality Management

C. Software Quality and Testing Methods

IX. Methodology

A. Research Design

B. Technical Design and Engineering

C. Software Development and Testing

D. Prototype Development

XI. Discussion

A. Key Innovations

XII. Conclusion And Future Work

Appendix A: Technical Specifications and Materials

A.1 Materials Used in Prototype Construction

A.2 Filtration Performance Testing

Acknowledgments

References

- Sadriddin, Z., Mekuria, R.R., & Isaev, R. (2023). A Compara-tive Study of the Analysis of PM2.5 Sources in Kyrgyzstan with 31 Selected Countries. In 2023 International Conference on Engi-neering Computing and Communication (ICECCO) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Mekuria, R.R., & Isaev, R. (2023). Applying Ma-chine Learning Analysis for Software Quality Test. In 2023 In-ternational Conference on Code Quality (ICCQ) (pp. 1-15). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, A., Isaev, R., Esenalieva, G., & Khamidov, Z. (2024). Design and implementation of wall-scale vector art drawing robot. In International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 2024 (CompSysTech ’24) (pp. 125-131). ACM. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, Z., Zhang, Q., & Zhao, H. (2022). Improving in-door air quality and occupant health through smart control of windows and portable air purifiers in residential buildings. Build-ing Services Engineering Research and Technology, 43(5), 571–588. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, K. M., Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., & Buka, S. L. (2009). 6th World Congress on Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 1(S1), S1–S60. [CrossRef]

- Marchwinska-Wyrwal, E., Dziubanek, G., Hajok, I., Rusin, M., Olek-siuk, K., & Kubasiak, M. (2011). Impact of air pollution on public health. In InTech eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, L., & Zhou, J. (2010). Neighborhood air quality, respi-ratory health, and vulnerable populations in compact and sprawled regions. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(3), 363–371. [CrossRef]

- Faiz, A., Weaver, C. S., & Walsh, M. P. (1996). Air pollution from motor vehicles. The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2015). World Development Indicators 2015. The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2015). Climate Change 2014 - Synthesis Report. [CrossRef]

- Dilley, M., Chen, R. S., Deichmann, U., Lerner-Lam, A. L., & Arnold, M. (2005). Natural disaster hotspots. The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Kenline, P. A., & Scarpino, P. V. (1972). Bacterial air pol-lution from sewage treatment plants. AIHAJ, 33(5), 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Le, N. L., & Nunes, S. P. (2016). Materials and membrane technologies for water and energy sustainability. Sustainable Materials and Technolo-gies, 7, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, E., Yang, Z., & Wang, F. (2015). Linked Data.

- ment in a subway station. Energy and Buildings, 202, 109440. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Heiselberg, P. K., Johra, H., & Guo, R. (2019). Experimental and numerical study of a PCM solar air heat exchanger and its ventilation preheating effectiveness. Renewable Energy, 145, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., Hsu, C.-H., Chang, Y.-J., Lee, C.-H., & Lee, D. L. (2022). Efficacy of HEPA air cleaner on improving indoor particulate matter 2.5 concentration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11517. [CrossRef]

- Frank, L. D., & Engelke, P. (2005). Multiple impacts of the built environment on public health: walkable places and the exposure to air pollution. International Regional Science Review, 28(2), 193–216. [CrossRef]

- S. Lau, “Effect of HEPA filter air cleaners (IQAir®/Incleen®) in homes of asthmatic children and adolescents sensitised to cat and dog allergens.” Jan. 18, 2013. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).