Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel Function and Structure

1.1. Extra-Mitochondrial Locations of VDAC

1.2. VDAC and Mitochondrial Dynamics

1.3. The Involvement of VDAC in Apoptosis

1.4. Involvement of pl-VDAC-1 in Neuroprotection

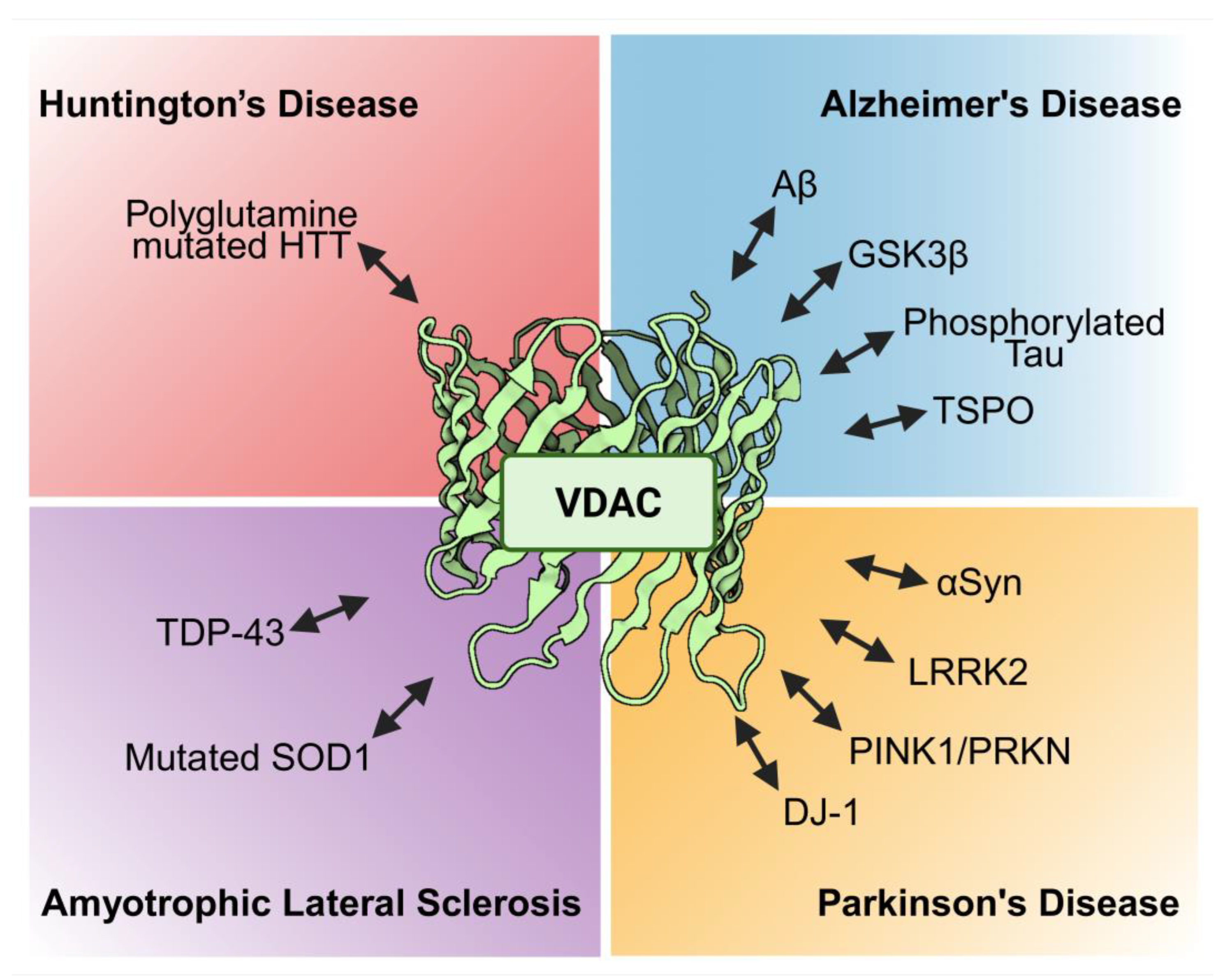

2. Alzheimer’s Disease and VDAC

3. Parkinson’s Disease and VDAC

4. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and VDAC

5. Huntington’s Disease and VDAC

6. Further Neurodegenerative Conditions and VDAC

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schein, S.J.; Colombini, M.; Finkelstein, A. Reconstitution in planar lipid bilayers of a voltage-dependent anion-selective channel obtained from paramecium mitochondria. J Membr Biol 1976, 30, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombini, M. A candidate for the permeability pathway of the outer mitochondrial membrane. Nature 1979, 279, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigen, W.J.; Graham, B.H. Genetic strategies for dissecting mammalian and drosophila voltage-dependent anion channel functions. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2008, 40, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, M.J.; Ross, L.; Decker, W.K.; Craigen, W.J. A novel isoform of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein vdac3 via alternative splicing of a 3-base exon. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, 30482–30486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, M. Vdac structure, selectivity, and dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Sheiko, T.; Graham, B.H.; Craigen, W.J. Voltage-dependant anion channels: Novel insights into isoform function through genetic models. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, H.; Janes, M.; Neupert, W. Biosynthesis of mitochondrial porin and insertion into the outer mitochondrial membrane of neurospora crassa. Eur J Biochem 1982, 126, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, F.U.; Pfanner, N.; Nicholson, D.W.; Neupert, W. Mitochondrial protein import. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989, 988, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.M.; Bykov, Y. Protein translocation in mitochondria: Sorting out the toms, tims, pams, sams and mia. FEBS Lett 2023, 597, 1553–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, R. Solute transport through mitochondrial porins in vitro and in vivo. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Reina, S.; Guarino, F.; De Pinto, V. Vdac isoforms in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Nahon-Crystal, E.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Gupta, R. Vdac1, mitochondrial dysfunction, and alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Res 2018, 131, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.H.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, S.W.; Sohn, S.H.; Lee, S.C.; Choi, S.; Pyo, S.; Rhee, D.K. Korean red ginseng up-regulates c21-steroid hormone metabolism via cyp11a1 gene in senescent rat testes. J Ginseng Res 2011, 35, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, K.A.; Milesi, V.; Maldonado, E.N. Vdac modulation of cancer metabolism: Advances and therapeutic challenges. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 742839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, S.; Garces, R.G.; Malia, T.J.; Orekhov, V.Y.; Colombini, M.; Wagner, G. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein vdac-1 in detergent micelles. Science 2008, 321, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrhuber, M.; Meins, T.; Habeck, M.; Becker, S.; Giller, K.; Villinger, S.; Vonrhein, C.; Griesinger, C.; Zweckstetter, M.; Zeth, K. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 15370–15375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujwal, R.; Cascio, D.; Colletier, J.P.; Faham, S.; Zhang, J.; Toro, L.; Ping, P.; Abramson, J. The crystal structure of mouse vdac1 at 2.3 a resolution reveals mechanistic insights into metabolite gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 17742–17747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schredelseker, J.; Paz, A.; Lopez, C.J.; Altenbach, C.; Leung, C.S.; Drexler, M.K.; Chen, J.N.; Hubbell, W.L.; Abramson, J. High resolution structure and double electron-electron resonance of the zebrafish voltage-dependent anion channel 2 reveal an oligomeric population. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 12566–12577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, R. Permeation of hydrophilic solutes through mitochondrial outer membranes: Review on mitochondrial porins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1994, 1197, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Maldonado, E.N.; Krelin, Y. Vdac1 at the crossroads of cell metabolism, apoptosis and cell stress. Cell Stress 2017, 1, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najbauer, E.E.; Becker, S.; Giller, K.; Zweckstetter, M.; Lange, A.; Steinem, C.; de Groot, B.L.; Griesinger, C.; Andreas, L.B. Structure, gating and interactions of the voltage-dependent anion channel. Eur Biophys J 2021, 50, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, H.; Bartos, L.; Dearden, G.I.; Dittman, J.S.; Holthuis, J.C.M.; Vacha, R.; Menon, A.K. Phospholipids are imported into mitochondria by vdac, a dimeric beta barrel scramblase. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostovtseva, T.K.; Bezrukov, S.M.; Hoogerheide, D.P. Regulation of mitochondrial respiration by vdac is enhanced by membrane-bound inhibitors with disordered polyanionic c-terminal domains. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Colombini, M. Vdac closure increases calcium ion flux. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1768, 2510–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchetto, V.; Reina, S.; Magri, A.; Szabo, I.; De Pinto, V. Recombinant human voltage dependent anion selective channel isoform 3 (hvdac3) forms pores with a very small conductance. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014, 34, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Gudermann, T.; Schredelseker, J. A calcium guard in the outer membrane: Is vdac a regulated gatekeeper of mitochondrial calcium uptake? Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvo, S.R.; Ferens, F.G.; Court, D.A. The n-terminus of vdac: Structure, mutational analysis, and a potential role in regulating barrel shape. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1858, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, A.; Reina, S.; De Pinto, V. Vdac1 as pharmacological target in cancer and neurodegeneration: Focus on its role in apoptosis. Front Chem 2018, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Israelson, A. The voltage-dependent anion channel in endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum: Characterization, modulation and possible function. J Membr Biol 2005, 204, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinnes, F.P.; Gotz, H.; Kayser, H.; Benz, R.; Schmidt, W.E.; Kratzin, H.D.; Hilschmann, N. [identification of human porins. I. Purification of a porin from human b-lymphocytes (porin 31hl) and the topochemical proof of its expression on the plasmalemma of the progenitor cell]. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 1989, 370, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathori, G.; Parolini, I.; Tombola, F.; Szabo, I.; Messina, A.; Oliva, M.; De Pinto, V.; Lisanti, M.; Sargiacomo, M.; Zoratti, M. Porin is present in the plasma membrane where it is concentrated in caveolae and caveolae-related domains. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 29607–29612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pinto, V.; Messina, A.; Lane, D.J.; Lawen, A. Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (vdac) in the plasma membrane. FEBS Lett 2010, 584, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, R.; Papoutsoglou, G.; Scemes, E.; Spray, D.C.; Dermietzel, R. Evidence for secretory pathway localization of a voltage-dependent anion channel isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 3201–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, Y.C.; Gu, X.Q.; Che, D.; Ma, C.Q.; Dai, Z.Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, T.; Cai, W.B.; Yang, Z.H.; et al. Plasminogen kringle 5 induces endothelial cell apoptosis by triggering a voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (vdac1) positive feedback loop. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 32628–32638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, M.I.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J.M.; Guix, F.X.; Vazquez, E.; Valverde, M.A. Plasma membrane voltage-dependent anion channel mediates antiestrogen-activated maxi cl- currents in c1300 neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 33284–33289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathori, G.; Parolini, I.; Szabo, I.; Tombola, F.; Messina, A.; Oliva, M.; Sargiacomo, M.; De Pinto, V.; Zoratti, M. Extramitochondrial porin: Facts and hypotheses. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2000, 32, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Lane, D.J.; Ly, J.D.; De Pinto, V.; Lawen, A. Vdac1 is a transplasma membrane nadh-ferricyanide reductase. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 4811–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Ly, J.D.; Lawen, A. Characterization of vdac1 as a plasma membrane nadh-oxidoreductase. Biofactors 2004, 21, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.F.; O’Neal, W.K.; Huang, P.; Nicholas, R.A.; Ostrowski, L.E.; Craigen, W.J.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Boucher, R.C. Voltage-dependent anion channel-1 (vdac-1) contributes to atp release and cell volume regulation in murine cells. J Gen Physiol 2004, 124, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Mohammed Al-Amily, I.; Mohammed, S.; Luan, C.; Asplund, O.; Ahmed, M.; Ye, Y.; Ben-Hail, D.; Soni, A.; Vishnu, N.; et al. Preserving insulin secretion in diabetes by inhibiting vdac1 overexpression and surface translocation in beta cells. Cell Metab 2019, 29, 64–77.e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsch, K.D.; De Pinto, V.; Aires, V.A.; Schneider, X.; Messina, A.; Hinsch, E. Voltage-dependent anion-selective channels vdac2 and vdac3 are abundant proteins in bovine outer dense fibers, a cytoskeletal component of the sperm flagellum. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 15281–15288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, V.A.; Cassara, M.C.; Benz, R.; de Pinto, V.; Messina, A.; Cunsolo, V.; Saletti, R.; Hinsch, K.D.; Hinsch, E. Molecular and functional characterization of vdac2 purified from mammal spermatozoa. Biosci Rep 2009, 29, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradowska, A.; Bohring, C.; Krause, E.; Krause, W. Identification of evolutionary conserved mouse sperm surface antigens by human antisperm antibodies (asa) from infertile patients. Am J Reprod Immunol 2006, 55, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W. The use of anti-vdac2 antibody for the combined assessment of human sperm acrosome integrity and ionophore a23187-induced acrosome reaction. PLoS One 2011, 6, e16985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Pan, B.; Zhao, Y.P.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, T.P.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.B.; Yang, Y.C. [immuno-proteomic screening of human pancreatic cancer associated membrane antigens for early diagnosis]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2007, 45, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valis, K.; Neubauerova, J.; Man, P.; Pompach, P.; Vohradsky, J.; Kovar, J. Vdac2 and aldolase a identified as membrane proteins of k562 cells with increased expression under iron deprivation. Mol Cell Biochem 2008, 311, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, G. Functional consequences of oxidative membrane damage. J Membr Biol 2005, 205, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzinska, M.; Galganska, H.; Wojtkowska, M.; Stobienia, O.; Kmita, H. Effects of vdac isoforms on cuzn-superoxide dismutase activity in the intermembrane space of saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 357, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ren, J.; Toan, S.; Mui, D. Role of mitochondrial quality surveillance in myocardial infarction: From bench to bedside. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 66, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertholet, A.M.; Delerue, T.; Millet, A.M.; Moulis, M.F.; David, C.; Daloyau, M.; Arnaune-Pelloquin, L.; Davezac, N.; Mils, V.; Miquel, M.C.; et al. Mitochondrial fusion/fission dynamics in neurodegeneration and neuronal plasticity. Neurobiology of disease 2016, 90, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, A.; Schrepfer, E.; Ziviani, E. Counteracting pink/parkin deficiency in the activation of mitophagy: A potential therapeutic intervention for parkinson’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016, 14, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zhou, H.; Sun, Y.; Fu, H.; Ran, Y.; Yang, B.; Yang, F.; Bjorklund, M.; Xu, S. Miro-1 interacts with vdac-1 to regulate mitochondrial membrane potential in caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep 2023, 24, e56297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Vashisht, A.A.; Tchieu, J.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Dreier, L. Voltage-dependent anion channels (vdacs) recruit parkin to defective mitochondria to promote mitochondrial autophagy. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 40652–40660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.R.; Fullerton, M.; Chaudhuri, M. Tim50 in trypanosoma brucei possesses a dual specificity phosphatase activity and is critical for mitochondrial protein import. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 3184–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ghosh, S. Phosphorylation of voltage-dependent anion channel by c-jun n-terminal kinase-3 leads to closure of the channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 459, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, M.; Alvir, R.V.; Alvir, R.V.; Bunquin, L.E.; Pradeepkiran, J.A.; Reddy, P.H. A partial reduction of vdac1 enhances mitophagy, autophagy, synaptic activities in a transgenic tau mouse model. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Kundu, P.; Sarin, A. Notch1 modulation of cellular calcium regulates mitochondrial metabolism and anti-apoptotic activity in t-regulatory cells. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 832159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrozzi, L.; Ricci, G.; Giglioli, N.J.; Siciliano, G.; Mancuso, M. Mitochondria and neurodegeneration. Biosci Rep 2007, 27, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, E.; Formichi, P.; Battisti, C.; Federico, A. Apoptosis and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis 2014, 42 (Suppl. 3), S125–S152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Tschopp, J. Apoptosis induced by death receptors. Pharm Acta Helv 2000, 74, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, A. Targeting the extrinsic apoptotic pathway in cancer: Lessons learned and future directions. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lai, Y.; Hua, Z.C. Apoptosis and apoptotic body: Disease message and therapeutic target potentials. Biosci Rep 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, H.L.; Schreiner, A.; Dewson, G.; Tait, S.W.G. Mitochondria and cell death. Nat Cell Biol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbride, S.M.; Prehn, J.H. Central roles of apoptotic proteins in mitochondrial function. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2703–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repnik, U.; Turk, B. Lysosomal-mitochondrial cross-talk during cell death. Mitochondrion 2010, 10, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Chandel, N.S.; Li, X.X.; Schumacker, P.T.; Colombini, M.; Thompson, C.B. Outer mitochondrial membrane permeability can regulate coupled respiration and cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 4666–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlicher, R.; Drahota, Z.; Stefkova, K.; Cervinkova, Z.; Kucera, O. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore-current knowledge of its structure, function, and regulation, and optimized methods for evaluating its functional state. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, M.; Braun, Y.; Smith, V.M.; Westhoff, M.A.; Pereira, R.S.; Pieper, N.M.; Anders, M.; Callens, M.; Vervliet, T.; Abbas, M.; et al. The bcl2 family: From apoptosis mechanisms to new advances in targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antignani, A.; Youle, R.J. How do bax and bak lead to permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane? Curr Opin Cell Biol 2006, 18, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, J.F.; Billen, L.P.; Bindner, S.; Shamas-Din, A.; Fradin, C.; Leber, B.; Andrews, D.W. Membrane binding by tbid initiates an ordered series of events culminating in membrane permeabilization by bax. Cell 2008, 135, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Ghosh, S. Bax increases the pore size of rat brain mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel in the presence of tbid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 323, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Tsujimoto, Y. Proapoptotic bh3-only bcl-2 family members induce cytochrome c release, but not mitochondrial membrane potential loss, and do not directly modulate voltage-dependent anion channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keinan, N.; Tyomkin, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Oligomerization of the mitochondrial protein voltage-dependent anion channel is coupled to the induction of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 2010, 30, 5698–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gupta, R.; Blanco, L.P.; Yang, S.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yoon, H.E.; Wang, X.; Kerkhofs, M.; et al. Vdac oligomers form mitochondrial pores to release mtdna fragments and promote lupus-like disease. Science 2019, 366, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalk, R.; Israelson, A.; Garty, E.S.; Azoulay-Zohar, H.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Oligomeric states of the voltage-dependent anion channel and cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Biochem J 2005, 386, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hamad, S.; Arbel, N.; Calo, D.; Arzoine, L.; Israelson, A.; Keinan, N.; Ben-Romano, R.; Friedman, O.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. The vdac1 n-terminus is essential both for apoptosis and the protective effect of anti-apoptotic proteins. J Cell Sci 2009, 122, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Mizrachi, D. Vdac1: From structure to cancer therapy. Front Oncol 2012, 2, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Mizrachi, D.; Keinan, N. Oligomerization of the mitochondrial protein vdac1: From structure to function and cancer therapy. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2013, 117, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinan, N.; Pahima, H.; Ben-Hail, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. The role of calcium in vdac1 oligomerization and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1833, 1745–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisthal, S.; Keinan, N.; Ben-Hail, D.; Arif, T.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Ca(2+)-mediated regulation of vdac1 expression levels is associated with cell death induction. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1843, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hail, D.; Begas-Shvartz, R.; Shalev, M.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Gruzman, A.; Reina, S.; De Pinto, V.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Novel compounds targeting the mitochondrial protein vdac1 inhibit apoptosis and protect against mitochondrial dysfunction. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 24986–25003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geula, S.; Naveed, H.; Liang, J.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Structure-based analysis of vdac1 protein: Defining oligomer contact sites. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 2179–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilansky, A.; Dangoor, L.; Nakdimon, I.; Ben-Hail, D.; Mizrachi, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. The voltage-dependent anion channel 1 mediates amyloid beta toxicity and represents a potential target for alzheimer disease therapy. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 30670–30683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Han, J.; Ben-Hail, D.; He, L.; Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. A new fungal diterpene induces vdac1-dependent apoptosis in bax/bak-deficient cells. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 23563–23578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; De, S.; Meir, A. The mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel 1, ca(2+) transport, apoptosis, and their regulation. Front Oncol 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Krelin, Y.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A. Vdac1 functions in ca(2+) homeostasis and cell life and death in health and disease. Cell Calcium 2018, 69, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbel, N.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1-based peptides interact with bcl-2 to prevent antiapoptotic activity. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 6053–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbel, N.; Ben-Hail, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Mediation of the antiapoptotic activity of bcl-xl protein upon interaction with vdac1 protein. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 23152–23161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, S.; Konishi, A.; Kodama, T.; Tsujimoto, Y. Bh4 domain of antiapoptotic bcl-2 family members closes voltage-dependent anion channel and inhibits apoptotic mitochondrial changes and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 3100–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hamad, S.; Zaid, H.; Israelson, A.; Nahon, E.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Hexokinase-i protection against apoptotic cell death is mediated via interaction with the voltage-dependent anion channel-1: Mapping the site of binding. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 13482–13490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, H.; Abu-Hamad, S.; Israelson, A.; Nathan, I.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. The voltage-dependent anion channel-1 modulates apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ 2005, 12, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.; Pandey, N.; Maitra, A.; Brahmachari, S.K.; Pillai, B. A role for voltage-dependent anion channel vdac1 in polyglutamine-mediated neuronal cell death. PLoS One 2007, 2, e1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbole, A.; Varghese, J.; Sarin, A.; Mathew, M.K. Vdac is a conserved element of death pathways in plant and animal systems. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003, 1642, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.J.; Dong, C.W.; Du, C.S.; Zhang, Q.Y. Characterization and expression analysis of paralichthys olivaceus voltage-dependent anion channel (vdac) gene in response to virus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2007, 23, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay-Zohar, H.; Israelson, A.; Abu-Hamad, S.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. In self-defence: Hexokinase promotes voltage-dependent anion channel closure and prevents mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death. Biochem J 2004, 377, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajeddine, N.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Hangen, E.; Morselli, E.; Senovilla, L.; Araujo, N.; Pinna, G.; Larochette, N.; Zamzami, N.; et al. Hierarchical involvement of bak, vdac1 and bax in cisplatin-induced cell death. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4221–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinder, F.; Akanda, N.; Tofighi, R.; Shimizu, S.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Orrenius, S.; Ceccatelli, S. Opening of plasma membrane voltage-dependent anion channels (vdac) precedes caspase activation in neuronal apoptosis induced by toxic stimuli. Cell Death Differ 2005, 12, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanda, N.; Tofighi, R.; Brask, J.; Tamm, C.; Elinder, F.; Ceccatelli, S. Voltage-dependent anion channels (vdac) in the plasma membrane play a critical role in apoptosis in differentiated hippocampal neurons but not in neural stem cells. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 3225–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.; Ramirez, C.M.; Gonzalez, M.; Gonzalez-Munoz, E.; Zorzano, A.; Camps, M.; Alonso, R.; Diaz, M. Voltage-dependent anion channel (vdac) participates in amyloid beta-induced toxicity and interacts with plasma membrane estrogen receptor alpha in septal and hippocampal neurons. Mol Membr Biol 2007, 24, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koma, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Okamura, N.; Yagami, T. A plausible involvement of plasmalemmal voltage-dependent anion channel 1 in the neurotoxicity of 15-deoxy-delta(12,14) -prostaglandin j2. Brain Behav 2020, 10, e01866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bengtsson, S.; Krogh, M.; Marquez, M.; Nilsson, S.; James, P.; Aliaya, A.; Holmberg, A.R. Somatostatin effects on the proteome of the lncap cell-line. Int J Oncol 2007, 30, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thinnes, F.P. Neuroendocrine differentiation of lncap cells suggests: Vdac in the cell membrane is involved in the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Mol Genet Metab 2009, 97, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heumann, R.; Goemans, C.; Bartsch, D.; Lingenhohl, K.; Waldmeier, P.C.; Hengerer, B.; Allegrini, P.R.; Schellander, K.; Wagner, E.F.; Arendt, T.; et al. Transgenic activation of ras in neurons promotes hypertrophy and protects from lesion-induced degeneration. J Cell Biol 2000, 151, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarty, K.; Serchov, T.; Mann, S.A.; Dietzel, I.D.; Heumann, R. Enhancement of dopaminergic properties and protection mediated by neuronal activation of ras in mouse ventral mesencephalic neurones. European Journal of Neuroscience 2007, 25, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felderhoff-Mueser, U.; Bittigau, P.; Sifringer, M.; Jarosz, B.; Korobowicz, E.; Mahler, L.; Piening, T.; Moysich, A.; Grune, T.; Thor, F.; et al. Oxygen causes cell death in the developing brain. Neurobiology of disease 2004, 17, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, M.; Herz, J.; Kempe, K.; Winterhager, E.; Jastrow, H.; Heumann, R.; Felderhoff-Muser, U.; Bendix, I. Protection of oligodendrocytes through neuronal overexpression of the small gtpase ras in hyperoxia-induced neonatal brain injury. Frontiers in neurology 2018, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, H.H.; Briem, T.; Dzietko, M.; Sifringer, M.; Voss, A.; Rzeski, W.; Zdzisinska, B.; Thor, F.; Heumann, R.; Stepulak, A.; et al. Mechanisms leading to disseminated apoptosis following nmda receptor blockade in the developing rat brain. Neurobiology of disease 2004, 16, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, M.; Serchov, T.; Hristova, M.; Bohatschek, M.; Gschwendtner, A.; Kalla, R.; Liu, Z.Q.; Heumann, R.; Raivich, G. Regulation and function of neuronal gtp-ras in facial motor nerve regeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry 2009, 108, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, S.; Kuteykin-Teplyakov, K.; Heumann, R. Neuronal protection by ha-ras-gtpase signaling through selective downregulation of plasmalemmal voltage-dependent anion channel-1. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorszewska, J.; Prendecki, M.; Oczkowska, A.; Dezor, M.; Kozubski, W. Molecular basis of familial and sporadic alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2016, 13, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, S.; Scherping, I.; Drose, S.; Brandt, U.; Schulz, K.L.; Jendrach, M.; Leuner, K.; Eckert, A.; Muller, W.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction: An early event in alzheimer pathology accumulates with age in ad transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 2009, 30, 1574–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuner, K.; Hauptmann, S.; Abdel-Kader, R.; Scherping, I.; Keil, U.; Strosznajder, J.B.; Eckert, A.; Muller, W.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction: The first domino in brain aging and alzheimer’s disease? Antioxid Redox Signal 2007, 9, 1659–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, M.; Park, B.S.; Jung, Y.; Reddy, P.H. Differential expression of oxidative phosphorylation genes in patients with alzheimer’s disease: Implications for early mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. Neuromolecular Med 2004, 5, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.H.; Tripathi, R.; Troung, Q.; Tirumala, K.; Reddy, T.P.; Anekonda, V.; Shirendeb, U.P.; Calkins, M.J.; Reddy, A.P.; Mao, P.; et al. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration as early events in alzheimer’s disease: Implications to mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1822, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.E.; Shi, Q. A mitocentric view of alzheimer’s disease suggests multi-faceted treatments. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 20 (Suppl. 2), S591–S607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.K.; Carlson, E.A.; Yan, S.S. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore is a potential drug target for neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1842, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.I.; Carvalho, C.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a trigger of alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1802, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, K.; Grimm, A.; Kazmierczak, A.; Strosznajder, J.B.; Gotz, J.; Eckert, A. Insights into mitochondrial dysfunction: Aging, amyloid-beta, and tau-a deleterious trio. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 16, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinto, V.; al Jamal, J.A.; Benz, R.; Genchi, G.; Palmieri, F. Characterization of sh groups in porin of bovine heart mitochondria. Porin cysteines are localized in the channel walls. Eur J Biochem 1991, 202, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinto, V.; Reina, S.; Gupta, A.; Messina, A.; Mahalakshmi, R. Role of cysteines in mammalian vdac isoforms’ function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1857, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeshko, V.V. Vdac as a voltage-dependent mitochondrial gatekeeper under physiological conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2023, 1865, 184175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, M.; Reddy, P.H. Abnormal interaction of vdac1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 5131–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado-Tejedor, M.; Vilarino, M.; Cabodevilla, F.; Del Rio, J.; Frechilla, D.; Perez-Mediavilla, A. Enhanced expression of the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (vdac1) in alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice: An insight into the pathogenic effects of amyloid-beta. J Alzheimers Dis 2011, 23, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, C.M.; Gonzalez, M.; Diaz, M.; Alonso, R.; Ferrer, I.; Santpere, G.; Puig, B.; Meyer, G.; Marin, R. Vdac and eralpha interaction in caveolae from human cortex is altered in alzheimer’s disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 2009, 42, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colurso, G.J.; Nilson, J.E.; Vervoort, L.G. Quantitative assessment of DNA fragmentation and beta-amyloid deposition in insular cortex and midfrontal gyrus from patients with alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci 2003, 73, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.F.; Selfridge, J.E.; Lu, J.; E, L.; Cardoso, S.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial abnormalities in alzheimer’s disease: Possible targets for therapeutic intervention. Adv Pharmacol 2012, 64, 83–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geula, S.; Ben-Hail, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Structure-based analysis of vdac1: N-terminus location, translocation, channel gating and association with anti-apoptotic proteins. Biochem J 2012, 444, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munter, L.M.; Voigt, P.; Harmeier, A.; Kaden, D.; Gottschalk, K.E.; Weise, C.; Pipkorn, R.; Schaefer, M.; Langosch, D.; Multhaup, G. Gxxxg motifs within the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane sequence are critical for the etiology of abeta42. EMBO J 2007, 26, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinnes, F.P. Apoptogenic interactions of plasmalemmal type-1 vdac and abeta peptides via gxxxg motifs induce alzheimer’s disease - a basic model of apoptosis? Wien Med Wochenschr 2011, 161, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinnes, F.P. New findings concerning vertebrate porin ii--on the relevance of glycine motifs of type-1 vdac. Mol Genet Metab 2013, 108, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, M.; Sheiko, T.; Craigen, W.J.; Reddy, P.H. Reduced vdac1 protects against alzheimer’s disease, mitochondria, and synaptic deficiencies. J Alzheimers Dis 2013, 37, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Kamenetsky, N.; Pittala, S.; Paul, A.; Nahon Crystal, E.; Ouro, A.; Chalifa-Caspi, V.; Pandey, S.K.; Monsonego, A.; et al. Targeting the overexpressed mitochondrial protein vdac1 in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease protects against mitochondrial dysfunction and mitigates brain pathology. Transl Neurodegener 2022, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Ilzorkina, A.I.; Matveeva, L.A.; Chulkov, A.V.; Semenova, A.A.; Dubinin, M.V.; Belosludtseva, N.V. Effect of vbit-4 on the functional activity of isolated mitochondria and cell viability. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2024, 1866, 184329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Kosaka, K. The formation of prostaglandins in the postmortem cerebral cortex of alzheimer-type dementia patients. J Neurol 1989, 236, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcone, S.; Fitzgerald, D.J. Proteomic identification of the candidate target proteins of 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin j2. Proteomics 2013, 13, 2135–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockenfeller, P. Phospholipid scramblase activity of vdac dimers: New implications for cell death, autophagy and ageing. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jope, R.S.; Yuskaitis, C.J.; Beurel, E. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (gsk3): Inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem Res 2007, 32, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, J.G.; Hoek, J.B.; Shulga, N. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta disrupts the binding of hexokinase ii to mitochondria by phosphorylating voltage-dependent anion channel and potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 10545–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Sui, D.; Dexheimer, T.; Hovde, S.; Deng, X.; Wang, K.W.; Lin, H.L.; Chien, H.T.; Kweon, H.K.; Kuo, N.S.; et al. Hyperphosphorylation renders tau prone to aggregate and to cause cell death. Mol Neurobiol 2020, 57, 4704–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H. Abnormal tau, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired axonal transport of mitochondria, and synaptic deprivation in alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 2011, 1415, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Kuriachan, G.; Mahalakshmi, R. Cellular interactome of mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels: Oligomerization and channel (mis)regulation. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021, 12, 3497–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, I. Altered mitochondria, energy metabolism, voltage-dependent anion channel, and lipid rafts converge to exhaust neurons in alzheimer’s disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2009, 41, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebneth, A.; Godemann, R.; Stamer, K.; Illenberger, S.; Trinczek, B.; Mandelkow, E. Overexpression of tau protein inhibits kinesin-dependent trafficking of vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum: Implications for alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol 1998, 143, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupprecht, R.; Papadopoulos, V.; Rammes, G.; Baghai, T.C.; Fan, J.; Akula, N.; Groyer, G.; Adams, D.; Schumacher, M. Translocator protein (18 kda) (tspo) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9, 971–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatliff, J.; East, D.; Crosby, J.; Abeti, R.; Harvey, R.; Craigen, W.; Parker, P.; Campanella, M. Tspo interacts with vdac1 and triggers a ros-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial quality control. Autophagy 2014, 10, 2279–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.F.; Dennett, O.; Lau, L.C.; Chatelet, D.S.; Bottlaender, M.; Nicoll, J.A.R.; Boche, D. The mitochondrial protein tspo in alzheimer’s disease: Relation to the severity of ad pathology and the neuroinflammatory environment. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, J.; Zhang, M.R.; Okauchi, T.; Ji, B.; Ono, M.; Hattori, S.; Kumata, K.; Iwata, N.; Saido, T.C.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic imaging of glial responses to amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in mouse models of alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 4720–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.L.; Belichenko, N.P.; Nguyen, T.V.; Andrews, L.E.; Ding, Z.; Liu, H.; Bodapati, D.; Arksey, N.; Shen, B.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Pet imaging of translocator protein (18 kda) in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease using n-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-2-18f-fluoro-n-(2-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide. J Nucl Med 2015, 56, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Maeda, J.; Sawada, M.; Ono, M.; Okauchi, T.; Inaji, M.; Zhang, M.R.; Suzuki, K.; Ando, K.; Staufenbiel, M.; et al. Imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor expression as biomarkers of detrimental versus beneficial glial responses in mouse models of alzheimer’s and other cns pathologies. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 12255–12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, N.; Tang, S.P.; Ashworth, S.; Coello, C.; Plisson, C.; Passchier, J.; Selvaraj, V.; Tyacke, R.J.; Nutt, D.J.; Sastre, M. In vivo imaging of microglial activation by positron emission tomography with [(11)c]pbr28 in the 5xfad model of alzheimer’s disease. Glia 2016, 64, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serriere, S.; Tauber, C.; Vercouillie, J.; Mothes, C.; Pruckner, C.; Guilloteau, D.; Kassiou, M.; Domene, A.; Garreau, L.; Page, G.; et al. Amyloid load and translocator protein 18 kda in appsweps1-de9 mice: A longitudinal study. Neurobiol Aging 2015, 36, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, B.B.; Tsartsalis, S.; Rigaud, D.; Fossey, C.; Cailly, T.; Fabis, F.; Pham, T.; Gregoire, M.C.; Kovari, E.; Moulin-Sallanon, M.; et al. Tspo and amyloid deposits in sub-regions of the hippocampus in the 3xtgad mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of disease 2019, 121, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yu, X.; Hu, S.; Yu, J. A brief review on the mechanisms of mirna regulation. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2009, 7, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennox, A.L.; Mao, H.; Silver, D.L. Rna on the brain: Emerging layers of post-transcriptional regulation in cerebral cortex development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Qiang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shao, X.; Yin, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Microrna-7 downregulates the oncogene vdac1 to influence hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and metastasis. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 10235–10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.D.; Choi, D.C.; Kabaria, S.; Tran, A.; Junn, E. Microrna-7 regulates the function of mitochondrial permeability transition pore by targeting vdac1 expression. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 6483–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Prajapati, B.; Saleem, K.; Kumari, R.; Mohindar Singh Singal, C.; Seth, P. Novel insights into role of mir-320a-vdac1 axis in astrocyte-mediated neuronal damage in neuroaids. Glia 2017, 65, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargaje, R.; Gupta, S.; Sarkeshik, A.; Park, R.; Xu, T.; Sarkar, M.; Halimani, M.; Roy, S.S.; Yates, J.; Pillai, B. Identification of novel targets for mir-29a using mirna proteomics. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, R.; Shridhar, S.; Sarangdhar, M.A.; Banik, A.; Chawla, M.; Garg, M.; Singh, V.P.; Pillai, B. Brain-specific knockdown of mir-29 results in neuronal cell death and ataxia in mice. RNA 2014, 20, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, S.S.; Horre, K.; Nicolai, L.; Papadopoulou, A.S.; Mandemakers, W.; Silahtaroglu, A.N.; Kauppinen, S.; Delacourte, A.; De Strooper, B. Loss of microrna cluster mir-29a/b-1 in sporadic alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased bace1/beta-secretase expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 6415–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stary, C.M.; Sun, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, L.; Giffard, R.G. Mir-29a differentially regulates cell survival in astrocytes from cornu ammonis 1 and dentate gyrus by targeting vdac1. Mitochondrion 2016, 30, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, E.W.; Yaffe, K.; Cauley, J.A.; Rolka, D.B.; Blackwell, T.L.; Narayan, K.M.; Cummings, S.R. Is diabetes associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline among older women? Study of osteoporotic fractures research group. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.N.N.; Lima-Filho, R.A.S.; De Felice, F.G. Connecting alzheimer’s disease to diabetes: Underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Neuropharmacology 2018, 136, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.S.; Craft, S. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease: Implications for treatment. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Huang, C.; Deng, H.; Wang, H. Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern Med J 2012, 42, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Lee, M.S.; Tsai, H.N. Incidence of dementia is increased in type 2 diabetes and reduced by the use of sulfonylureas and metformin. J Alzheimers Dis 2011, 24, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.Q.; Folstein, M.F. Insulin, insulin-degrading enzyme and amyloid-beta peptide in alzheimer’s disease: Review and hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging 2006, 27, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickstein, E.; Krauss, S.; Thornhill, P.; Rutschow, D.; Zeller, R.; Sharkey, J.; Williamson, R.; Fuchs, M.; Kohler, A.; Glossmann, H.; et al. Biguanide metformin acts on tau phosphorylation via mtor/protein phosphatase 2a (pp2a) signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 21830–21835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, T.R.; Forny-Germano, L.; Sathler, L.B.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Houzel, J.C.; Decker, H.; Silverman, M.A.; Kazi, H.; Melo, H.M.; McClean, P.L.; et al. An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse brain from defective insulin signaling caused by alzheimer’s disease- associated abeta oligomers. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, K.; Wang, H.Y.; Kazi, H.; Han, L.Y.; Bakshi, K.P.; Stucky, A.; Fuino, R.L.; Kawaguchi, K.R.; Samoyedny, A.J.; Wilson, R.S.; et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with igf-1 resistance, irs-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 1316–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandimalla, R.; Thirumala, V.; Reddy, P.H. Is alzheimer’s disease a type 3 diabetes? A critical appraisal. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kciuk, M.; Kruczkowska, W.; Galeziewska, J.; Wanke, K.; Kaluzinska-Kolat, Z.; Aleksandrowicz, M.; Kontek, R. Alzheimer’s disease as type 3 diabetes: Understanding the link and implications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhir, R.; Gupta, S. Molecular and biochemical trajectories from diabetes to alzheimer’s disease: A critical appraisal. World J Diabetes 2015, 6, 1223–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglietto-Vargas, D.; Shi, J.; Yaeger, D.M.; Ager, R.; LaFerla, F.M. Diabetes and alzheimer’s disease crosstalk. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016, 64, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, M.; Sato, N. Bidirectional interactions between diabetes and alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 2017, 108, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gracia, E.; Torrejon-Escribano, B.; Ferrer, I. Dystrophic neurites of senile plaques in alzheimer’s disease are deficient in cytochrome c oxidase. Acta Neuropathol 2008, 116, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Muhammed, S.J.; Kessler, B.; Salehi, A. Mitochondrial proteome analysis reveals altered expression of voltage dependent anion channels in pancreatic beta-cells exposed to high glucose. Islets 2010, 2, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Donthamsetty, R.; Heldak, M.; Cho, Y.E.; Scott, B.T.; Makino, A. Vdac: Old protein with new roles in diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012, 303, C1055–C1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, P.; Vilasi, S.; Librizzi, F.; Contardi, M.; Nuzzo, D.; Caruana, L.; Baldassano, S.; Amato, A.; Mule, F.; San Biagio, P.L.; et al. Biological and biophysics aspects of metformin-induced effects: Cortex mitochondrial dysfunction and promotion of toxic amyloid pre-fibrillar aggregates. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 1718–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysnes, O.B.; Storstein, A. Epidemiology of parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2017, 124, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, A.; Ferreira, J.J.; Rocha, J.F.; Rascol, O.; Poewe, W.; Gama, H.; Soares-da-Silva, P. Safety profile of opicapone in the management of parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2019, 9, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, A.; Hogl, B. Sleep in parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveinbjornsdottir, S. The clinical symptoms of parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2016, 139 (Suppl. 1), 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.; Postuma, R.B.; Adler, C.H.; Bloem, B.R.; Chan, P.; Dubois, B.; Gasser, T.; Goetz, C.G.; Halliday, G.; Joseph, L.; et al. Mds research criteria for prodromal parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2015, 30, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrino, R.; Schapira, A.H.V. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol 2020, 27, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, C.; Anjum, R.; Shakeel, N.U.A. Parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms, translational models and management strategies. Life Sci 2019, 226, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damier, P.; Hirsch, E.C.; Agid, Y.; Graybiel, A.M. The substantia nigra of the human brain. Ii. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in parkinson’s disease. Brain 1999, 122 Pt 8, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K. Cortico-basal ganglia-cortical circuitry in parkinson’s disease reconsidered. Exp Neurol 2008, 212, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, W.; Schulz, J.B. Current and experimental treatments of parkinson disease: A guide for neuroscientists. J Neurochem 2016, 139 (Suppl. 1), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heumann, R.; Moratalla, R.; Herrero, M.T.; Chakrabarty, K.; Drucker-Colin, R.; Garcia-Montes, J.R.; Simola, N.; Morelli, M. Dyskinesia in parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and current non-pharmacological interventions. J Neurochem 2014, 130, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. Alpha-synuclein in lewy bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, A.R.; Arduino, D.M.; Silva, D.F.; Oliveira, C.R.; Cardoso, S.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction: The road to alpha-synuclein oligomerization in pd. Parkinsons Dis 2011, 2011, 693761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadanza, M.G.; Jackson, M.P.; Hewitt, E.W.; Ranson, N.A.; Radford, S.E. A new era for understanding amyloid structures and disease. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2018, 19, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, T.; Ahlstrom, L.S.; Leftin, A.; Kamp, F.; Haass, C.; Brown, M.F.; Beyer, K. The n-terminus of the intrinsically disordered protein alpha-synuclein triggers membrane binding and helix folding. Biophys J 2010, 99, 2116–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, E.A.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Giasson, B.I. Characterization of hydrophobic residue requirements for alpha-synuclein fibrillization. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 9427–9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.; Walker, D.E.; Goldstein, J.M.; de Laat, R.; Banducci, K.; Caccavello, R.J.; Barbour, R.; Huang, J.; Kling, K.; Lee, M.; et al. Phosphorylation of ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic lewy body disease. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 29739–29752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, T.; Choi, J.G.; Selkoe, D.J. Alpha-synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 2011, 477, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousset, L.; Pieri, L.; Ruiz-Arlandis, G.; Gath, J.; Jensen, P.H.; Habenstein, B.; Madiona, K.; Olieric, V.; Bockmann, A.; Meier, B.H.; et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alpha-synuclein strains. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angot, E.; Steiner, J.A.; Hansen, C.; Li, J.Y.; Brundin, P. Are synucleinopathies prion-like disorders? Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Nonaka, T.; Hosokawa, M.; Oikawa, T.; Arai, T.; Akiyama, H.; Mann, D.M.; Hasegawa, M. Prion-like spreading of pathological alpha-synuclein in brain. Brain 2013, 136, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, G.; Chen, S.W.; Williamson, P.T.F.; Cascella, R.; Perni, M.; Jarvis, J.A.; Cecchi, C.; Vendruscolo, M.; Chiti, F.; Cremades, N.; et al. Structural basis of membrane disruption and cellular toxicity by alpha-synuclein oligomers. Science 2017, 358, 1440–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deas, E.; Cremades, N.; Angelova, P.R.; Ludtmann, M.H.; Yao, Z.; Chen, S.; Horrocks, M.H.; Banushi, B.; Little, D.; Devine, M.J.; et al. Alpha-synuclein oligomers interact with metal ions to induce oxidative stress and neuronal death in parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 24, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danzer, K.M.; Haasen, D.; Karow, A.R.; Moussaud, S.; Habeck, M.; Giese, A.; Kretzschmar, H.; Hengerer, B.; Kostka, M. Different species of alpha-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 9220–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luth, E.S.; Stavrovskaya, I.G.; Bartels, T.; Kristal, B.S.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble, prefibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers promote complex i-dependent, ca2+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 21490–21507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovtseva, T.K.; Gurnev, P.A.; Protchenko, O.; Hoogerheide, D.P.; Yap, T.L.; Philpott, C.C.; Lee, J.C.; Bezrukov, S.M. Alpha-synuclein shows high affinity interaction with voltage-dependent anion channel, suggesting mechanisms of mitochondrial regulation and toxicity in parkinson disease. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 18467–18477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.; Raghavendran, V.; Prabhu, B.M.; Avadhani, N.G.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of alpha-synuclein impair complex i in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 9089–9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, C.; Yin, J.; Li, X.; Cheng, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Ueda, K.; Chan, P.; Yu, S. Alpha-synuclein is differentially expressed in mitochondria from different rat brain regions and dose-dependently down-regulates complex i activity. Neurosci Lett 2009, 454, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.E.; Murphy, E.J.; Mitchell, D.C.; Golovko, M.Y.; Scaglia, F.; Barcelo-Coblijn, G.C.; Nussbaum, R.L. Mitochondrial lipid abnormality and electron transport chain impairment in mice lacking alpha-synuclein. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25, 10190–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkon, H.; Don, J.; Melamed, E.; Ziv, I.; Shirvan, A.; Offen, D. Mutant and wild-type alpha-synuclein interact with mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. J Mol Neurosci 2002, 18, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K. Alpha-synuclein and mitochondria: Partners in crime? Neurotherapeutics 2013, 10, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogerheide, D.P.; Rostovtseva, T.K.; Bezrukov, S.M. Exploring lipid-dependent conformations of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein with the vdac nanopore. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2021, 1863, 183643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosencrans, W.M.; Aguilella, V.M.; Rostovtseva, T.K.; Bezrukov, S.M. Alpha-synuclein emerges as a potent regulator of vdac-facilitated calcium transport. Cell Calcium 2021, 95, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queralt-Martin, M.; Bergdoll, L.; Teijido, O.; Munshi, N.; Jacobs, D.; Kuszak, A.J.; Protchenko, O.; Reina, S.; Magri, A.; De Pinto, V.; et al. A lower affinity to cytosolic proteins reveals vdac3 isoform-specific role in mitochondrial biology. J Gen Physiol 2020, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, C.; Cai, Q.; Lu, Q.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, H. Voltage-dependent anion channel involved in the alpha-synuclein-induced dopaminergic neuron toxicity in rats. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2013, 45, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J.; Semenkow, S.; Hanaford, A.; Wong, M. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore regulates parkinson’s disease development in mutant alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 1132–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Goldman, J.G.; Kelly, L.; He, Y.; Waliczek, T.; Kordower, J.H. Abnormal alpha-synuclein reduces nigral voltage-dependent anion channel 1 in sporadic and experimental parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease 2014, 69, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberio, T.; Mammucari, C.; D’Agostino, G.; Rizzuto, R.; Fasano, M. Altered dopamine homeostasis differentially affects mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels turnover. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1842, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, A.; Simantov, R. Mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel is involved in dopamine-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem 2002, 82, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Ding, H.; Xu, M.; Gao, J. Protective effects of asiatic acid on rotenone- or h2o2-induced injury in sh-sy5y cells. Neurochem Res 2009, 34, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burte, F.; De Girolamo, L.A.; Hargreaves, A.J.; Billett, E.E. Alterations in the mitochondrial proteome of neuroblastoma cells in response to complex 1 inhibition. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 1974–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalingam, K.B.; Somanath, S.D.; Ramdas, P.; Haleagrahara, N.; Radhakrishnan, A.K. 6-hydroxydopamine induces neurodegeneration in terminally differentiated sh-sy5y neuroblastoma cells via enrichment of the nucleosomal degradation pathway: A global proteomics approach. J Mol Neurosci 2022, 72, 1026–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo de Lima, L.; Oliveira Cunha, P.L.; Felicio Calou, I.B.; Tavares Neves, K.R.; Facundo, H.T.; Socorro de Barros Viana, G. Effects of vitamin d (vd3) supplementation on the brain mitochondrial function of male rats, in the 6-ohda-induced model of parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 2022, 154, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junn, E.; Lee, K.W.; Jeong, B.S.; Chan, T.W.; Im, J.Y.; Mouradian, M.M. Repression of alpha-synuclein expression and toxicity by microrna-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 13052–13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggio, L.; Vivarelli, S.; L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Marchetti, B.; Iraci, N. Micrornas in parkinson’s disease: From pathogenesis to novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, K.J.; Murray, T.K.; Bengoa-Vergniory, N.; Cordero-Llana, O.; Cooper, J.; Buckley, A.; Wade-Martins, R.; Uney, J.B.; O’Neill, M.J.; Wong, L.F.; et al. Loss of microrna-7 regulation leads to alpha-synuclein accumulation and dopaminergic neuronal loss in vivo. Mol Ther 2017, 25, 2404–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovini, A.; Gurnev, P.A.; Beilina, A.; Queralt-Martin, M.; Rosencrans, W.; Cookson, M.R.; Bezrukov, S.M.; Rostovtseva, T.K. Molecular mechanism of olesoxime-mediated neuroprotection through targeting alpha-synuclein interaction with mitochondrial vdac. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 77, 3611–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordet, T.; Buisson, B.; Michaud, M.; Drouot, C.; Galea, P.; Delaage, P.; Akentieva, N.P.; Evers, A.S.; Covey, D.F.; Ostuni, M.A.; et al. Identification and characterization of cholest-4-en-3-one, oxime (tro19622), a novel drug candidate for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007, 322, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, M.; Queralt-Martin, M.; Gurnev, P.A.; Rosencrans, W.M.; Rovini, A.; Jacobs, D.; Abrantes, K.; Hoogerheide, D.P.; Bezrukov, S.M.; Rostovtseva, T.K. Restricting alpha-synuclein transport into mitochondria by inhibition of alpha-synuclein-vdac complexation as a potential therapeutic target for parkinson’s disease treatment. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 79, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Gui, J.; Qin, B.; Ye, J.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, A.; Sang, M.; Sun, X. Resveratrol inhibits vdac1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction to mitigate pathological progression in parkinson’s disease model. Mol Neurobiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino, C.; Crosio, C.; Vitale, C.; Sanna, G.; Carri, M.T.; Barone, P. Apoptotic mechanisms in mutant lrrk2-mediated cell death. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Yu, M.; Niu, J.; Yue, Z.; Xu, Z. Expression of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (lrrk2) inhibits the processing of umtck to induce cell death in a cell culture model system. Biosci Rep 2011, 31, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitada, T.; Asakawa, S.; Hattori, N.; Matsumine, H.; Yamamura, Y.; Minoshima, S.; Yokochi, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Shimizu, N. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 1998, 392, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimura, H.; Hattori, N.; Kubo, S.; Mizuno, Y.; Asakawa, S.; Minoshima, S.; Shimizu, N.; Iwai, K.; Chiba, T.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Familial parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogaeva, E.; Johnson, J.; Lang, A.E.; Gulick, C.; Gwinn-Hardy, K.; Kawarai, T.; Sato, C.; Morgan, A.; Werner, J.; Nussbaum, R.; et al. Analysis of the pink1 gene in a large cohort of cases with parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2004, 61, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, E.M.; Abou-Sleiman, P.M.; Caputo, V.; Muqit, M.M.; Harvey, K.; Gispert, S.; Ali, Z.; Del Turco, D.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Healy, D.G.; et al. Hereditary early-onset parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in pink1. Science 2004, 304, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickrell, A.M.; Youle, R.J. The roles of pink1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in parkinson’s disease. Neuron 2015, 85, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Jing, X.; Guo, J.; Yao, X.; Guo, F. Mitophagy in degenerative joint diseases. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, S.; Holmstrom, K.M.; Skujat, D.; Fiesel, F.C.; Rothfuss, O.C.; Kahle, P.J.; Springer, W. Pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on vdac1 and p62/sqstm1. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, S.; Kirk, N.S.; Gan, Z.Y.; Dite, T.; Cobbold, S.A.; Leis, A.; Dagley, L.F.; Glukhova, A.; Komander, D. Structure of human pink1 at a mitochondrial tom-vdac array. Science 2025, eadu6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.J.; Lee, D.; Yoo, H.; Jun, K.; Shin, H.; Chung, J. Decision between mitophagy and apoptosis by parkin via vdac1 ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 4281–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Fan, C.; Gu, L.; Gao, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Qi, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, H.; Cai, Q.; et al. Silencing of pink1 induces mitophagy via mitochondrial permeability transition in dopaminergic mn9d cells. Brain Res 2011, 1394, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Sun, W.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Liu, A.; Ma, H.; Lai, X.; Wu, J. Idebenone improves motor dysfunction, learning and memory by regulating mitophagy in mptp-treated mice. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, C.; Jalali Sefid Dashti, Z.; Christoffels, A.; Loos, B.; Bardien, S. Evidence for a common biological pathway linking three parkinson’s disease-causing genes: Parkin, pink1 and dj-1. Eur J Neurosci 2015, 41, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottolini, D.; Cali, T.; Negro, A.; Brini, M. The parkinson disease-related protein dj-1 counteracts mitochondrial impairment induced by the tumour suppressor protein p53 by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Hum Mol Genet 2013, 22, 2152–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Fujioka, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, X. Dj-1 regulates the integrity and function of er-mitochondria association through interaction with ip3r3-grp75-vdac1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 25322–25328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, V.; Marchesan, E.; Ziviani, E. A trio has turned into a quartet: Dj-1 interacts with the ip3r-grp75-vdac complex to control er-mitochondria interaction. Cell Calcium 2020, 87, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.W.; Rothstein, J.D. From charcot to lou gehrig: Deciphering selective motor neuron death in als. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001, 2, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, D.W.; Kurland, L.T.; Offord, K.P.; Beard, C.M. Familial adult motor neuron disease: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 1986, 36, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C.; Pagnini, F.; Friede, T.; Young, C.A. Treatment of fatigue in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 1, CD011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guan, L.; Deng, M. Recent progress of the genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and challenges of gene therapy. Front Neurosci 2023, 17, 1170996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Gall, L.; Anakor, E.; Connolly, O.; Vijayakumar, U.G.; Duddy, W.J.; Duguez, S. Molecular and cellular mechanisms affected in als. J Pers Med 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.R.; Siddique, T.; Patterson, D.; Figlewicz, D.A.; Sapp, P.; Hentati, A.; Donaldson, D.; Goto, J.; O’Regan, J.P.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Mutations in cu/zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 1993, 362, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanghai, N.; Tranmer, G.K. Hydrogen peroxide and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: From biochemistry to pathophysiology. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hamad, S.; Kahn, J.; Leyton-Jaimes, M.F.; Rosenblatt, J.; Israelson, A. Misfolded sod1 accumulation and mitochondrial association contribute to the selective vulnerability of motor neurons in familial als: Correlation to human disease. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israelson, A.; Arbel, N.; Da Cruz, S.; Ilieva, H.; Yamanaka, K.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Cleveland, D.W. Misfolded mutant sod1 directly inhibits vdac1 conductance in a mouse model of inherited als. Neuron 2010, 67, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Vande Velde, C.; Israelson, A.; Xie, J.; Bailey, A.O.; Dong, M.Q.; Chun, S.J.; Roy, T.; Winer, L.; Yates, J.R.; et al. Als-linked mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (sod1) alters mitochondrial protein composition and decreases protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 21146–21151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Argueti-Ostrovsky, S.; Leyton-Jaimes, M.F.; Anand, U.; Abu-Hamad, S.; Zalk, R.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Israelson, A. Targeting the mitochondrial protein vdac1 as a potential therapeutic strategy in als. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Naniche, N.; Bogush, A.; Pedrini, S.; Trotti, D.; Pasinelli, P. Small peptides against the mutant sod1/bcl-2 toxic mitochondrial complex restore mitochondrial function and cell viability in mutant sod1-mediated als. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 11588–11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Sau, D.; Guareschi, S.; Bogush, M.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; Naniche, N.; Kia, A.; Trotti, D.; Pasinelli, P. Als-linked mutant sod1 damages mitochondria by promoting conformational changes in bcl-2. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Argueti, S.; Gupta, R.; Shvil, N.; Abu-Hamad, S.; Gropper, Y.; Hoeber, J.; Magri, A.; Messina, A.; Kozlova, E.N.; et al. A vdac1-derived n-terminal peptide inhibits mutant sod1-vdac1 interactions and toxicity in the sod1 model of als. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, A.; Belfiore, R.; Reina, S.; Tomasello, M.F.; Di Rosa, M.C.; Guarino, F.; Leggio, L.; De Pinto, V.; Messina, A. Hexokinase i n-terminal based peptide prevents the vdac1-sod1 g93a interaction and re-establishes als cell viability. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, A.; Risiglione, P.; Caccamo, A.; Formicola, B.; Tomasello, M.F.; Arrigoni, C.; Zimbone, S.; Guarino, F.; Re, F.; Messina, A. Small hexokinase 1 peptide against toxic sod1 g93a mitochondrial accumulation in als rescues the atp-related respiration. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, K.; Zhang, F.; Vien, A.; Cashman, N.R.; Zhu, H. Mitochondrial proteomic analysis of a cell line model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2004, 3, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittala, M.G.G.; Reina, S.; Cubisino, S.A.M.; Cucina, A.; Formicola, B.; Cunsolo, V.; Foti, S.; Saletti, R.; Messina, A. Post-translational modification analysis of vdac1 in als-sod1 model cells reveals specific asparagine and glutamine deamidation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittala, M.G.G.; Reina, S.; Nibali, S.C.; Cucina, A.; Cubisino, S.A.M.; Cunsolo, V.; Amodeo, G.F.; Foti, S.; De Pinto, V.; Saletti, R.; et al. Specific post-translational modifications of vdac3 in als-sod1 model cells identified by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunyach, C.; Michaud, M.; Arnoux, T.; Bernard-Marissal, N.; Aebischer, J.; Latyszenok, V.; Gouarne, C.; Raoul, C.; Pruss, R.M.; Bordet, T.; et al. Olesoxime delays muscle denervation, astrogliosis, microglial activation and motoneuron death in an als mouse model. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 2346–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenglet, T.; Lacomblez, L.; Abitbol, J.L.; Ludolph, A.; Mora, J.S.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Pruss, R.M.; Cuvier, V.; Meininger, V.; et al. A phase ii-iii trial of olesoxime in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2014, 21, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, A.; Lipari, C.L.R.; Caccamo, A.; Battiato, G.; Conti Nibali, S.; De Pinto, V.; Guarino, F.; Messina, A. Aav-mediated upregulation of vdac1 rescues the mitochondrial respiration and sirtuins expression in a sod1 mouse model of inherited als. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, X.G.; Jansen, G.; Amaradio, M.; Costanza, J.; Umeton, R.; Guarino, F.; De Pinto, V.; Oliver, S.G.; Messina, A.; Nicosia, G. Inferring gene regulatory networks of als from blood transcriptome profiles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Davidson, S.; Harapas, C.R.; Hilton, J.B.; Mlodzianoski, M.J.; Laohamonthonkul, P.; Louis, C.; Low, R.R.J.; Moecking, J.; De Nardo, D.; et al. Tdp-43 triggers mitochondrial DNA release via mptp to activate cgas/sting in als. Cell 2020, 183, 636–649.e618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.A.; Itaman, S.; Khalid-Janney, C.M.; Sherard, J.A.; Dowell, J.A.; Cairns, N.J.; Gitcho, M.A. Tdp-43 interacts with mitochondrial proteins critical for mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics. Neurosci Lett 2018, 678, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilotto, F.; Schmitz, A.; Maharjan, N.; Diab, R.; Odriozola, A.; Tripathi, P.; Yamoah, A.; Scheidegger, O.; Oestmann, A.; Dennys, C.N.; et al. Polyga targets the er stress-adaptive response by impairing grp75 function at the mam in c9orf72-als/ftd. Acta Neuropathol 2022, 144, 939–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illarioshkin, S.N.; Klyushnikov, S.A.; Vigont, V.A.; Seliverstov, Y.A.; Kaznacheyeva, E.V. Molecular pathogenesis in huntington’s disease. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2018, 83, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Estevez-Fraga, C.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; Flower, M.D.; Scahill, R.I.; Wild, E.J.; Munoz-Sanjuan, I.; Sampaio, C.; Rosser, A.E.; Leavitt, B.R. Potential disease-modifying therapies for huntington’s disease: Lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonka, D. Factors contributing to clinical picture and progression of huntington’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2018, 13, 1364–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, A. Molecular pathophysiological mechanisms in huntington’s disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, L.E.; Weber, J.J.; Wlodkowski, T.T.; Yu-Taeger, L.; Michaud, M.; Calaminus, C.; Eckert, S.H.; Gaca, J.; Weiss, A.; Magg, J.C.; et al. Olesoxime suppresses calpain activation and mutant huntingtin fragmentation in the bachd rat. Brain 2015, 138, 3632–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Lepak, V.C.; Eberly, L.E.; Roth, B.; Cui, W.; Zhu, X.H.; Oz, G.; Dubinsky, J.M. Oxygen consumption deficit in huntington disease mouse brain under metabolic stress. Hum Mol Genet 2016, 25, 2813–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, E.; Wong, S.; Hung, C.; Ross-Inta, C.; Bomdica, P.; Giulivi, C. Defective mitochondrial disulfide relay system, altered mitochondrial morphology and function in huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2013, 22, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perluigi, M.; Poon, H.F.; Maragos, W.; Pierce, W.M.; Klein, J.B.; Calabrese, V.; Cini, C.; De Marco, C.; Butterfield, D.A. Proteomic analysis of protein expression and oxidative modification in r6/2 transgenic mice: A model of huntington disease. Mol Cell Proteomics 2005, 4, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karachitos, A.; Grobys, D.; Kulczynska, K.; Sobusiak, A.; Kmita, H. The association of vdac with cell viability of pc12 model of huntington’s disease. Front Oncol 2016, 6, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatriz, M.; Vilaca, R.; Anjo, S.I.; Manadas, B.; Januario, C.; Rego, A.C.; Lopes, C. Defective mitochondria-lysosomal axis enhances the release of extracellular vesicles containing mitochondrial DNA and proteins in huntington’s disease. J Extracell Biol 2022, 1, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondani, M.; Roginski, A.C.; Ribeiro, R.T.; de Medeiros, M.P.; Hoffmann, C.I.H.; Wajner, M.; Leipnitz, G.; Seminotti, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, er stress and mitochondria-er crosstalk alterations in a chemical rat model of huntington’s disease: Potential benefits of bezafibrate. Toxicol Lett 2023, 381, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Emam, M.A.; Sheta, E.; El-Abhar, H.S.; Abdallah, D.M.; El Kerdawy, A.M.; Eldehna, W.M.; Gowayed, M.A. Morin suppresses mtorc1/ire-1alpha/jnk and ip3r-vdac-1 pathways: Crucial mechanisms in apoptosis and mitophagy inhibition in experimental huntington’s disease, supported by in silico molecular docking simulations. Life Sci 2024, 338, 122362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, B.; Zou, M.; Peng, B.; Rao, Y. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-concepts, classification, and avenues for therapy. CNS Neurosci Ther 2025, 31, e70261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielar, C.; Wishart, T.M.; Palmer, A.; Dihanich, S.; Wong, A.M.; Macauley, S.L.; Chan, C.H.; Sands, M.S.; Pearce, D.A.; Cooper, J.D.; et al. Molecular correlates of axonal and synaptic pathology in mouse models of batten disease. Hum Mol Genet 2009, 18, 4066–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homewood, J.; Bond, N.W. Thiamin deficiency and korsakoff’s syndrome: Failure to find memory impairments following nonalcoholic wernicke’s encephalopathy. Alcohol 1999, 19, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, A.S.; Butterworth, R.F. Update of cell damage mechanisms in thiamine deficiency: Focus on oxidative stress, excitotoxicity and inflammation. Alcohol Alcohol 2009, 44, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, K.O.; de Souza Resende, L.; Ribeiro, A.F.; Dos Santos, D.M.; Goncalves, E.C.; Vigil, F.A.; de Oliveira Silva, I.F.; Ferreira, L.F.; de Castro Pimenta, A.M.; Ribeiro, A.M. Spatial cognitive deficits in an animal model of wernicke-korsakoff syndrome are related to changes in thalamic vdac protein concentrations. Neuroscience 2015, 294, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, E.; Thakur, M.K. Alterations in hippocampal mitochondrial dynamics are associated with neurodegeneration and recognition memory decline in old male mice. Biogerontology 2022, 23, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).