Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Anthropometric and Biochemical Assessments

2.3. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

2.3.1. Measurement of Reduced Glutathione (GSH) in Erythrocytes

2.3.2. Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC)

2.3.3. TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances)

2.4. Ethical Compliance

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

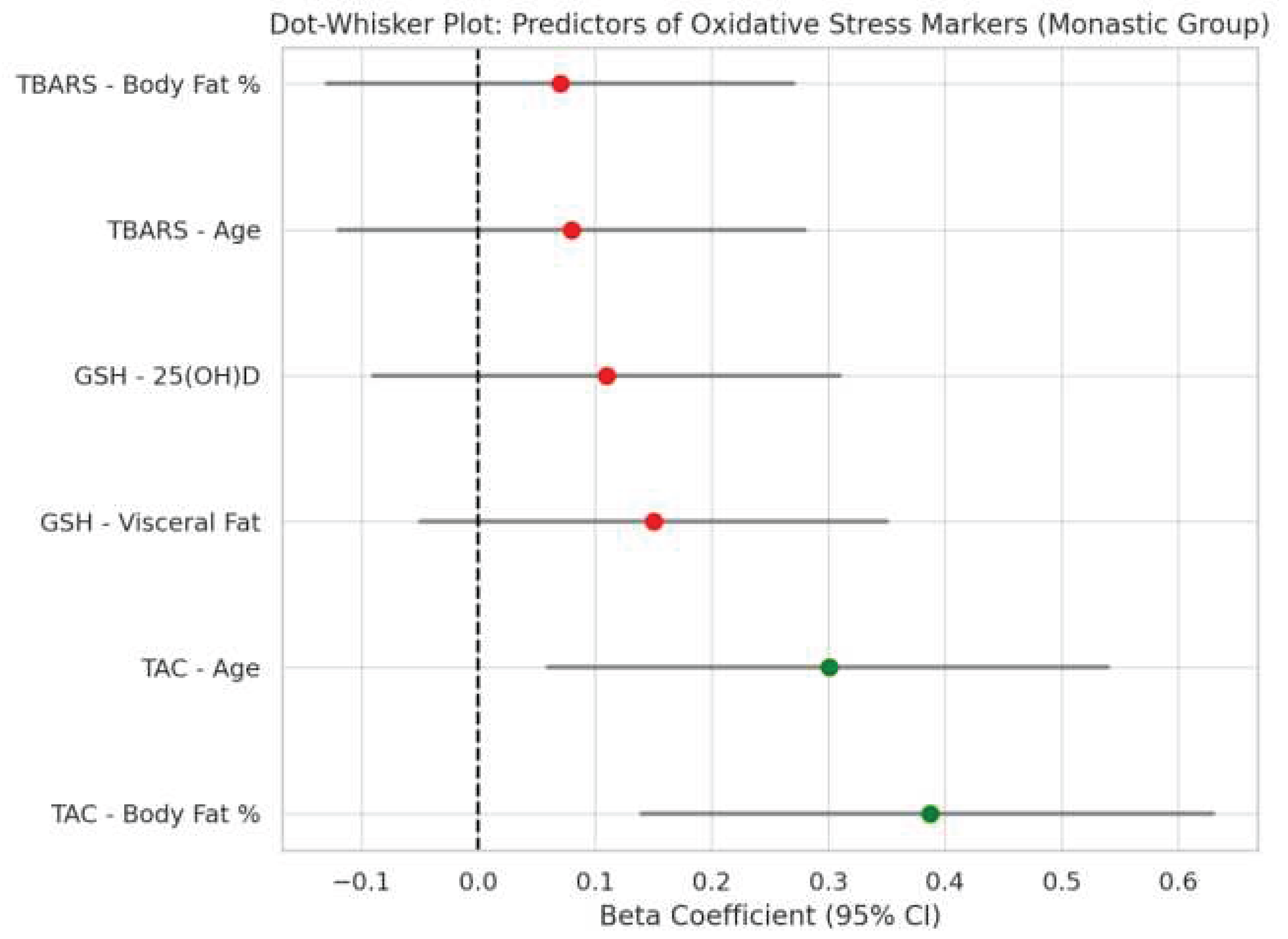

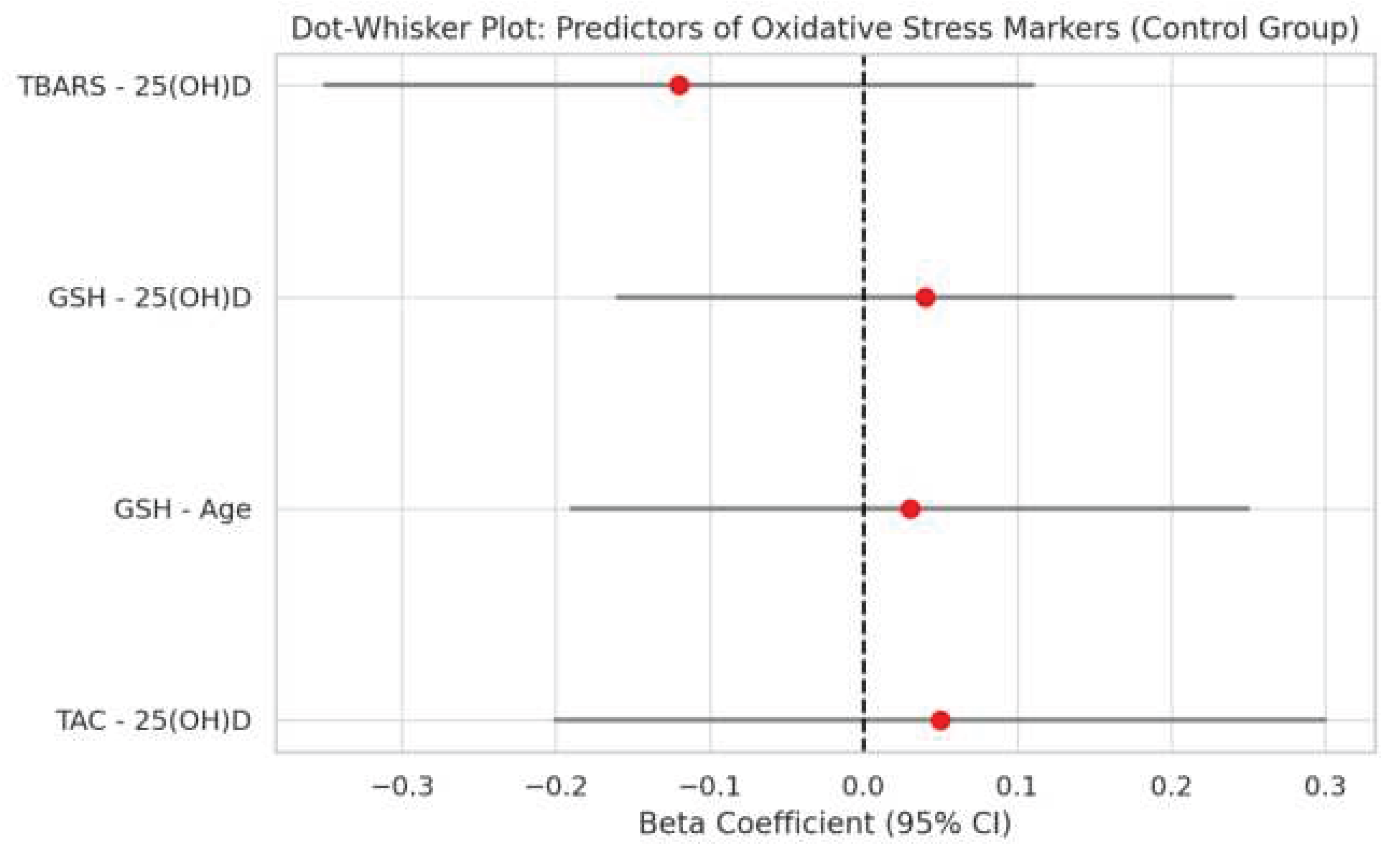

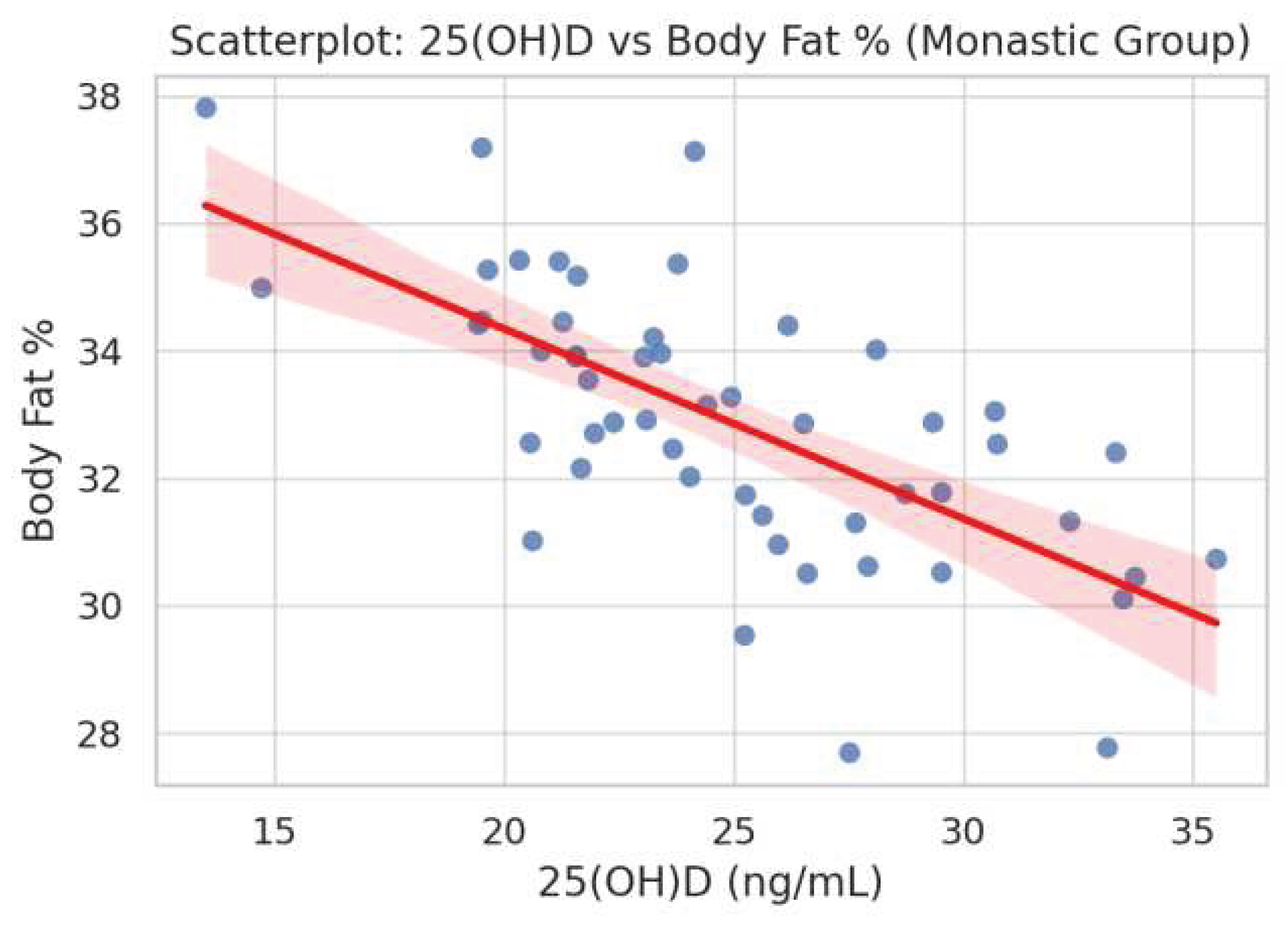

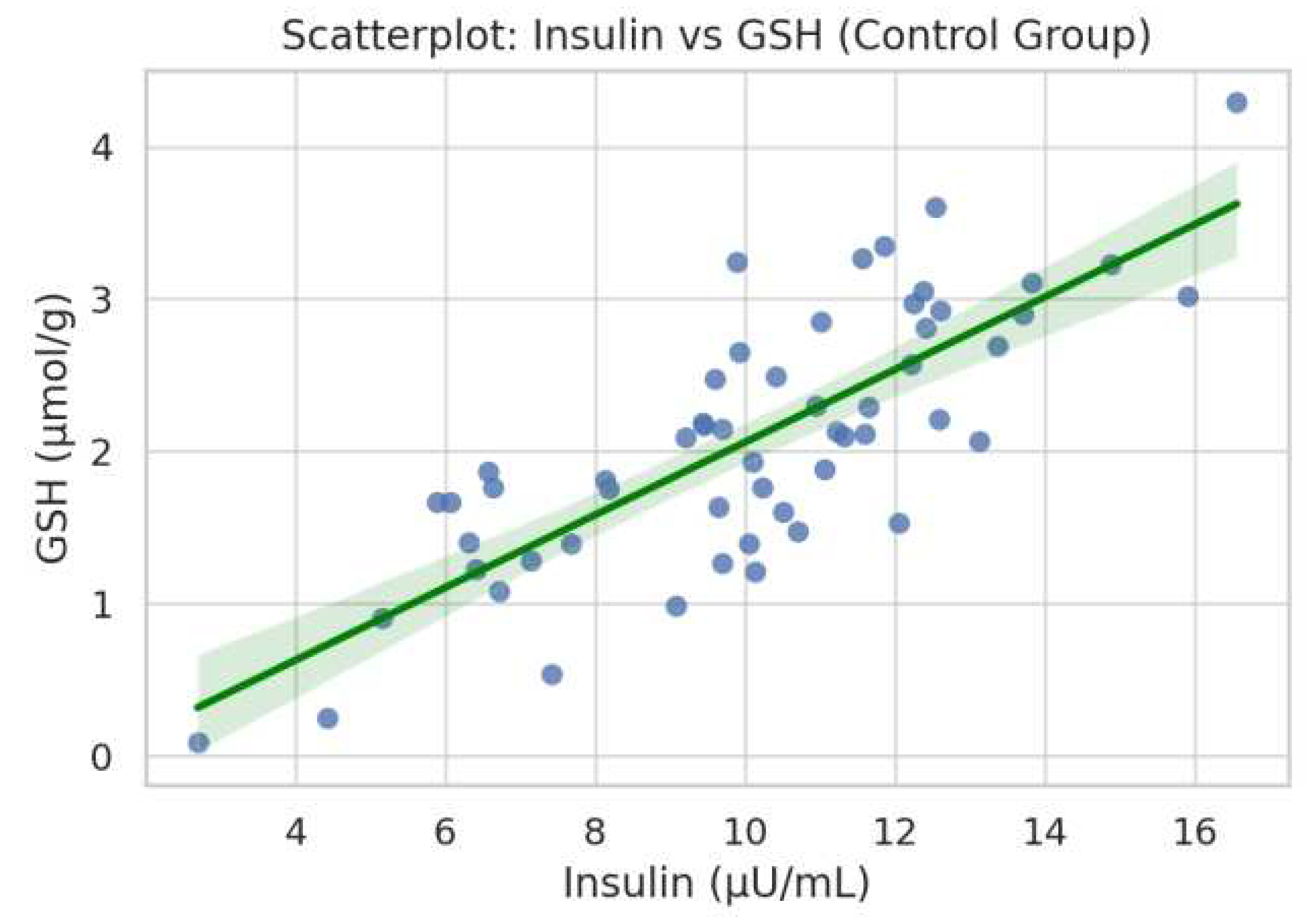

3.1. Predictors of Stress Markers

3.2. Correlations Between Oxidative Stress Markers and Metabolic Parameters

3.3.Regression Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers

3.4. Bivariate Associations Between Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Bloomer, R.J. The impact of religious fasting on human health. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 57–57. [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.O.; Linardakis, M.K.; Bervanaki, F.N.; Tzanakis, N.E.; Kafatos, A.G. Greek Orthodox fasting rituals: a hidden characteristic of the Mediterranean diet of Crete. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 277–284. [CrossRef]

- O. Sarri, K.; E Tzanakis, N.; Linardakis, M.K.; Mamalakis, G.D.; Kafatos, A.G. Effects of Greek orthodox christian church fasting on serum lipids and obesity. BMC Public Heal. 2003, 3, 16–16. [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.; Linardakis, M.; Codrington, C.; Kafatos, A. Does the periodic vegetarianism of Greek Orthodox Christians benefit blood pressure?. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 341–348. [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Adamidou, L.; Antonopoulou, V.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Mitrofanova, E.; Mulrooney, H.; Petróczi, A.; Zebekakis, P.; et al. Effects of orthodox religious fasting versus combined energy and time restricted eating on body weight, lipid concentrations and glycaemic profile. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 72, 82–92. [CrossRef]

- Mehta LH, Roth GS. Caloric restriction and longevity: the science and the ascetic experience. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 Aug;1172:28-33.

- Papadaki, A.; Vardavas, C.; Hatzis, C.; Kafatos, A. Calcium, nutrient and food intake of Greek Orthodox Christian monks during a fasting and non-fasting week. Public Health Nutr 2008, 11, 1022–1029. [CrossRef]

- de Toledo, F.W.; Grundler, F.; Goutzourelas, N.; Tekos, F.; Vassi, E.; Mesnage, R.; Kouretas, D. Influence of Long-Term Fasting on Blood Redox Status in Humans. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 496. [CrossRef]

- Romeu, M.; Aranda, N.; Giralt, M.; Ribot, B.; Nogues, M.R.; Arija, V. Diet, iron biomarkers and oxidative stress in a representative sample of Mediterranean population. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 102. [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Michalakis, K.; Tekos, F.; Skaperda, Z.; Vardakas, P.; Ziakas, P.D.; Kypraiou, M.; Anemoulis, M.; Vlastos, A.; Tzimagiorgis, G.; et al. Effects of Religious Fasting on Markers of Oxidative Status in Vitamin D-Deficient and Overweight Orthodox Nuns versus Implementation of Time-Restricted Eating in Lay Women from Central and Northern Greece. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3300. [CrossRef]

- He J, Deng R, Wei Y, Zhang S, Su M, Tang M, Wang J, Nong W, Lei X. Efficacy of antioxidant supple-mentation in improving endocrine, hormonal, inflammatory, and metabolic statuses of PCOS: a me-ta-analysis and systematic review. Food Funct. 2024 Feb 19;15(4):1779-1802.

- He, C.-T.; Chen, F.-Y.; Kuo, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pei, D.; Pitrone, P.; Chen, J.-S.; Wu, C.-Z. Association between gamma-glutamyl transferase and diabetes factors among elderly nonobese individuals. Medicine 2025, 104, e41913. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Jensen, M.D. Human Adipose Tissue Metabolism in Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 34, 105–119. [CrossRef]

- Colamatteo, A.; Fusco, C.; Matarese, A.; Matarese, G. Obesity and Autoimmunity Epidemic: The Role of Immunometabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ježek, P. Physiological Fatty Acid-Stimulated Insulin Secretion and Redox Signaling Versus Lipotoxicity. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2025, 42, 566–622. [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Joseph, A.J.; Adedoyin, E.D.; Iheagwam, O.T.; Ejoh, S.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetes: Shedding Light on a Widespread Oversight. Pathophysiology, 32, 9. [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Michalakis, K.; Katsiki, N.; Kypraiou, M.; Vlastos, A.; Anemoulis, M.; Koukoulis, G.; Mouslech, Z.; Talidis, F.; Tzimagiorgis, G.; et al. Interrelations of Leptin and Interleukin-6 in Vitamin D Deficient and Overweight Orthodox Nuns from Northern Greece: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1144. [CrossRef]

- Hertiš Petek T, Homšak E, Svetej M, Marčun Varda N. Metabolic Syndrome, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Vitamin D Levels in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Oct 1;25(19):10599.

- Mattson, M.P. Roles of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and associated vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.P. Membrane alteration as a basis of aging and the protective effects of calorie restriction. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 1003–1010. [CrossRef]

- Licker, M.; Ellenberger, C. Impact of the Circadian Rhythm and Seasonal Changes on the Outcome of Cardiovascular Interventions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2570. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, Y.; Xu, K.; Lin, L. Protective Effects of 1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 against High-Glucose-Induced Damage in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Involve Activation of Nrf2 Antioxidant Signaling. J. Vasc. Res. 2021, 58, 267–276. [CrossRef]

- Asghari, S.; Hamedi-Shahraki, S.; Amirkhizi, F. Vitamin D status and systemic redox biomarkers in adults with obesity. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 45, 292–298. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Chowdhury, R.; Jones, D.P.; Martin, G.S.; Brigham, K.L.; Binongo, J.N.; Ziegler, T.R.; Tangpricha, V. Vitamin D status is independently associated with plasma glutathione and cysteine thiol/disulphide redox status in adults. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 81, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, K.; Datta, V.; Fuller, S. Adipokines as Cardioprotective Factors: BAT Steps Up to the Plate. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 710. [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Roset, A.; Quesada-López, T.; Mestres-Arenas, A.; Villarroya, J.; Godoy-Nieto, F.J.; Cereijo, R.; Rupérez, C.; Neess, D.; Færgeman, N.J.; Giralt, M.; et al. Acyl CoA-binding protein in brown adipose tissue acts as a negative regulator of adaptive thermogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2025, 96, 102153. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Humes F, Almond G, Kavazis AN, Hood WR. A mitohormetic response to pro-oxidant expo-sure in the house mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018 Jan 1;314(1):R122-R134.28.

- Zhou, M.; Lv, J.; Chen, X.; Shi, Y.; Chao, G.; Zhang, S. From gut to liver: Exploring the crosstalk between gut-liver axis and oxidative stress in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2025, 30, 101777. [CrossRef]

- Zavarzadeh, P.G.; Panchal, K.; Bishop, D.; Gilbert, E.; Trivedi, M.; Kee, T.; Ranganathan, S.; Arunagiri, A. Exploring proinsulin proteostasis: insights into beta cell health and diabetes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1554717. [CrossRef]

- Pawlukianiec C, Lauko KK, Michalak D, Żendzian-Piotrowska M, Zalewska A, Maciejczyk M. A com-parative study on the antioxidant and antiglycation properties of different vitamin D forms. Eur J Med Chem. 2025 Mar 5;285:117263.

- Della Nera G, Sabatino L, Gaggini M, Gorini F, Vassalle C. Vitamin D Determinants, Status, and Anti-oxidant/Anti-inflammatory-Related Effects in Cardiovascular Risk and Disease: Not the Last Word in the Controversy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023 Apr 18;12(4):948.

- Moslemi, E.; Musazadeh, V.; Kavyani, Z.; Naghsh, N.; Shoura, S.M.S.; Dehghan, P. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation as an adjunct therapy for improving inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers: An umbrella meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 186, 106484. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, N.J.; Soni, S.; Takahara, S.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Al Batran, R.; Darwesh, A.M.; Levasseur, J.L.; Beker, D.; Vos, D.Y.; Schmidt, M.A.; et al. Chronically Elevating Circulating Ketones Can Reduce Cardiac Inflammation and Blunt the Development of Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2020, 13, e006573. [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Adamidou, L.; Dimakopoulos, G.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Zebekakis, P.; Makedou, K.; Kotsa, K. Different patterns of changes in free 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during intermittent fasting among meat eaters and non-meat eaters and correlations with amino acid intake. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 74, 257–267. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shafei, A.I. Ramadan fasting ameliorates oxidative stress and improves glycemic control and lipid profile in diabetic patients. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1475–1481. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shafei, A.I.M. Ramadan fasting ameliorates arterial pulse pressure and lipid profile, and alleviates oxidative stress in hypertensive patients. Blood Press. 2013, 23, 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Lapenna, D. Glutathione and glutathione-dependent enzymes: From biochemistry to gerontology and successful aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102066. [CrossRef]

- Peifer-Weiß, L.; Al-Hasani, H.; Chadt, A. AMPK and Beyond: The Signaling Network Controlling RabGAPs and Contraction-Mediated Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1910. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony R, Segev O, Dor S, Raz I. Overview of oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes. J Diabetes. 2024 Oct;16(10):e70014.

- Jain, U.; Srivastava, P.; Sharma, A.; Sinha, S.; Johari, S. Impaired Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21) Associated with Visceral Adiposity Leads to Insulin Resistance: The Core Defect in Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2025, 21, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves M, Vale N, Silva P. Neuroprotective Effects of Olive Oil: A Comprehensive Review of Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024 Jun 24;13(7):762.

| Marker | Variable | ρ | p |

| TAC | 25(OH)D | 0.074 | 0.331 |

| TAC | Body Fat % | 0.387 | 0.041 |

| TAC | Visceral Fat | 0.317 | 0.031 |

| TAC | Age | 0.301 | 0.014 |

| GSH | 25(OH)D | 0.026 | 0.729 |

| GSH | Body Fat % | 0.387 | 0.041 |

| GSH | Visceral Fat | 0.317 | 0.031 |

| GSH | Age | 0.301 | 0.014 |

| TBARS | 25(OH)D | -0.038 | 0.617 |

| TBARS | Body Fat % | N/A | 0.061 |

| TBARS | Visceral Fat | N/A | N/A |

| TBARS | Age | N/A | N/A |

| Marker | Variable | ρ | p |

| TAC | 25(OH)D | -0.293 | 0.0875 |

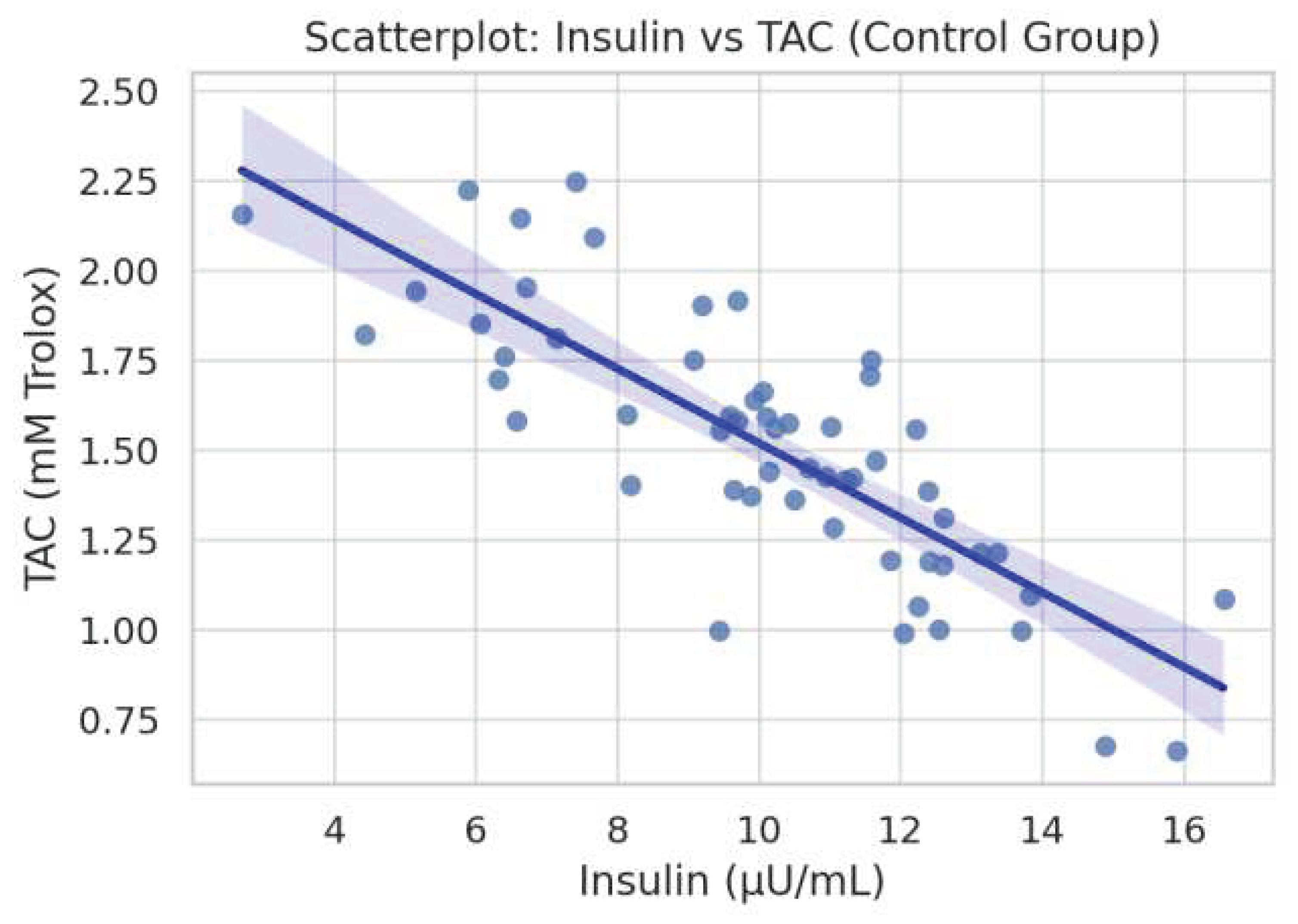

| TAC | Insulin | -0.321 | 0.0598 |

| TAC | Body Fat % | N/A | N/A |

| TAC | Visceral Fat | N/A | N/A |

| TAC | Age | -0.629 | 0.0001 |

| GSH | 25(OH)D | 0.212 | 0.2225 |

| GSH | Insulin | 0.480 | 0.0035 |

| GSH | Body Fat % | N/A | N/A |

| GSH | Visceral Fat | N/A | N/A |

| GSH | Age | N/A | N/A |

| TBARS | 25(OH)D | -0.120 | 0.110 |

| TBARS | Insulin | 0.209 | 0.229 |

| TBARS | Body Fat % | N/A | N/A |

| TBARS | Visceral Fat | N/A | N/A |

| TBARS | Age | N/A | N/A |

| Outcome | Model | R2 | Adj R2 |

| TAC (Monastics) | Age + BMI | 0.009 | -0.046 |

| TAC + 25(OH)D | Extended | 0.019 | -0.067 |

| GSH (Monastics) | Age + BMI | 0.02 | -0.035 |

| GSH + 25(OH)D | Extended | 0.023 | -0.063 |

| TBARS (Monastics) | Age + BMI | 0.005 | -0.051 |

| TBARS + 25(OH)D | Extended | 0.024 | -0.062 |

| Outcome | Model | R2 | Adj R2 |

| TAC (Controls) | Age + BMI + Fat + VF | 0.019 | -0.099 |

| TAC + 25(OH)D | Extended | 0.026 | -0.126 |

| GSH (Controls) | Age + BMI + Fat + VF | 0.157 | 0.055 |

| GSH + 25(OH)D | Extended | 0.157 | 0.026 |

| TBARS (Controls) | Age + BMI + Fat + VF | 0.101 | -0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).