Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminary

- (i)

- If , then the embedding of W into is compact.

- (ii)

- If and , then the embedding of W into is compact.

- (i)

- Let be a nonnegative, absolutely continuous function on , which satisfies for a.e. t the differential inequalitywhere and are nonnegative summable functions on . Thenfor all .

- (ii)

- In particular, ifthen

3. Existence and Uniqueness

3.1. Existence

3.2. Uniqueness

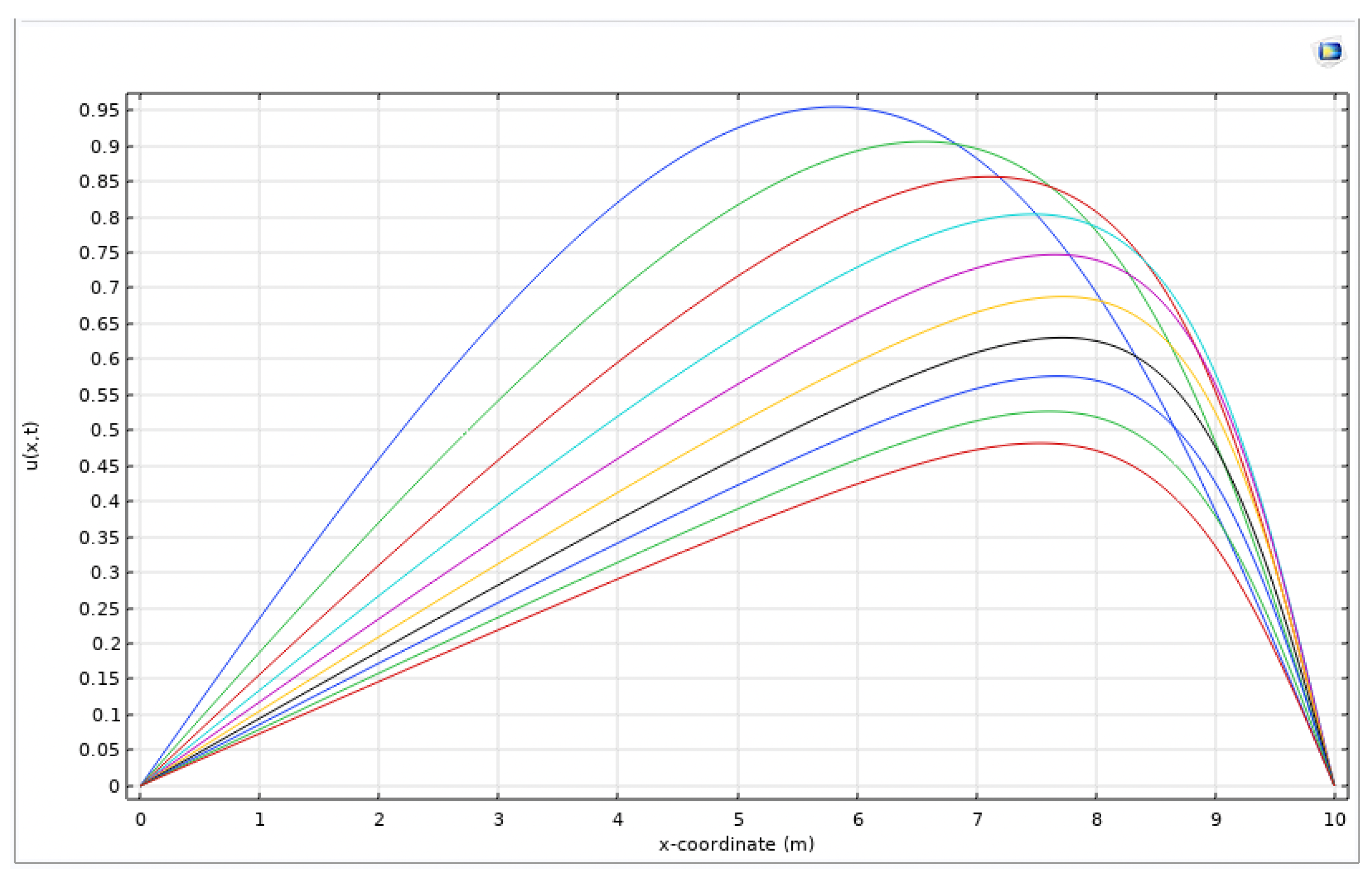

4. Numerical part

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Salih A.; Burgers’ Equation. Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram, 2016.

- Bird R.B.; Armstrong R.C.; Hassager O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Volume 1: Fluid Mechanics; Wiley: New York, 1987.

- Hayat T.; Fetecau C.; Asghar S. Some simple flows of a Burgers’ fluid. Int J Eng Sci. 2006 44, 1423–1431. Acta Mech. 2006, 184, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tong D.; Shan L. Exact solutions for generalized Burgers’ fluid in an annular pipe. Meccanica. 2009, 44, 427–431. [CrossRef]

- Xue C.; Nie J. Exact solutions of Stokes first problem for heated generalized Burgers’ fluid in a porous half space. Non Linear Anal Real World Appl. 2008, 9, 1628–1637. [CrossRef]

- Vieru D.; Hayat T.; Fetecau C.; Fetecau C. On the first problem of Stokes’ for Burgers’ fluid, II: the Cases γ=λ2/4 and γ>λ2/4. Appl Math Comput. 2008, 197, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Borden, H. Traveling Wave Solutions of Burgers’ Equation for Power-law Non-Newtonian flows. Appl. Math. E-Notes 2011, 11, 133–138.

- Shu, Y.; Numerical Solutions of Generalized Burgers’ Equations for Some Incompressible Non-Newtonian Fluids. University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2015, 2051. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2051.

- Zhapsarbayeva L., Wei D., Bagymkyzy B. Existence and Uniqueness of the viscous Burgers’ Equation with the p-Laplace Operator. Mathematics. 2025, 13(708), 1-14.

- Kheyfets, V.; Kieweg, S. Gravity-Driven Thin Film Flow of an Ellis Fluid. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics.,2013, 202, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, Y. D. Generalized Couette flow of an Ellis fluid. AIChE Journal, 1966, 12 (5), 890–893.

- Steller, R.; Iwko, J. Generalized flow of Ellis fluid in the screw channel: 2. Curved channel model. International Polymer Processing Journal of the Polymer Processing Society, 2001, 16, 249. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman A-B.; Mathieu S.; James N. H.; Roger I. N.;, Miguel M-G. Identification of Ellis rheological law from free surface velocity. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics, 2019, 263, 15-23. ISSN 0377-0257. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.K. A Review on Burgers’ Equations and It’s Applications. Journal of Institute of Science and Technology. 2023, 28(2). [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.; Khan, I. Time-Dependent MHD Flow of Non-Newtonian Generalized Burgers’ Fluid (GBF) Over a Suddenly Moved Plate With Generalized Darcy’s Law. Frontiers in Physics. 2020, 7, 214. [CrossRef]

- Brezis, H. Functional Analysis, Sobolev Spaces and Partial Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011.

- Benia Y.; Sadallah B. Existence of solutions to Burgers equations in domains that can be transformed into rectangles. Electr. J. Differ. Equ. 2016, 157, 1-13.

- Dragomir S.S.; Adil Khan M; Abathun A. Refinement of the Jensen integral inequality. Open Math. 2016, 14, 221-228. [CrossRef]

- Aubin J-P. Un théorème de compacité. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1963, 256, 5042–5044.

- Evans L.C. Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 1998.

- Wade W.R. The Bounded Convergence Theorem. Am. Math. Mon. 1974, 81, 387–389. [CrossRef]

- Dwight H.B. Tables of integrals and other mathematical data. 3rd ed.; The Macmillan company: New York, 1957.

- Lindqvist P. Notes on the Stationary p-Laplace Equation, 1st ed.; SpringerBriefs in Mathematics: Switzerland, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).