1. Introduction

The Burgers’ equation, first introduced by J.M. Burgers, is a fundamental model for various physical processes, including shock wave propagation and turbulence [

1]. Originally formulated for Newtonian fluids, the Burgers’ equation has been extensively analyzed; however, its generalization to non-Newtonian fluids—specifically those described by the power-law model—has received comparatively less attention for the case when

[

2]. We employ a particular case of the generalized Burgers’ equation formulated by Wei and Jordan [

3], which was used to analyze acoustic propagation in power-law fluids. Traveling wave solutions of this equation were derived by Wei and Borden [

4].

This paper’s main focus is to investigate the existence and uniqueness of weak solutions to the generalized viscous Burgers’ equation. The study is framed within the context of Sobolev spaces, which provide a robust mathematical environment for addressing weak solutions and ensuring appropriate regularity conditions [

5].

Establishing the existence of weak solutions to nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs) like the generalized Burgers’ equation has been well-studied in the context of Newtonian fluids [

6,

7]. However, extending these results to the power-law non-Newtonian fluids involves additional complexities due to the nonlinearity introduced by the fluid’s viscosity [

8]. The unique solutions for the generalized Burgers’ equation based on power-law fluids remain largely unexplored for the case when

, creating a gap in the current literature that this paper aims to address.

Wei and Jordan [

3] established the following Burgers’ equation

as a model to study acoustic traveling waves in Power-law fluids with

, is the power-law index.

In this paper, we study the well-posedness and numerical solutions of a special case of the above equation with initial and boundary conditions

By using the dimensionless variables

,

,

, to the last equation, we obtain the following problem, in which

,

,

are still denoted by

x,

u,

t

with

and

. In equation (

1),

stands for the Reynolds number, a dimensionless quantity determining the flow behavior based on the balance of inertial and viscous forces. The Reynolds number for power-law fluids is given by

where

L and

represent the characteristic length and velocity, respectively (see, for example, [

9]). The Reynolds number significantly influences the stability of the flow and the type of flow regime observed. Our numerical simulations demonstrate this. When in case

, equation (

1) becomes a well-known Burgers’ equation for a Newtonian fluid

The well-posedness of the viscous Burgers’ equation for Newtonian fluid has been studied intensively in the literature (see, for example, [

6,

10,

11]). To our knowledge, the well-posedness of the problem (

1) has not been studied before. In our work, we prove the result concerning the existence, uniqueness, and regularity of a solution to the Burgers equation with

p-Laplasian right-hand side (

1).

Multiplying the equation of (

1) by a test function

, and integrating by parts from 0 to 1, we convert the initial boundary value problem (

1) to the following integral equation

for all

,

and

.

Definition 1.1. For , a function , for which is said to be a weak solution of problem (1) if it satisfies equation (2) for each and a.e. and for all .

Now, we present the main result of the work.

Theorem 1.2. Let . Then there exists a unique solution of (1) such that , in the sense of Definition 1.1.

In

Section 2, we state some preliminary information needed to study the well-posedness of the problem (

1), formulated in the weak form (

2). Section 3 consists of two subSection 3.1 and Section 3.2. We obtain the existence result in Section 3.1 and establish the uniqueness of the solution in Section 3.2. Moreover, in Section 4, we construct the numerical solutions for the various values of the Reynolds number

, by using the COMSOL PDE solver with some numerical manipulations to avoid singularity in

at points where

.

2. Preliminary

We present well-known facts that we will use to prove Theorem 1.2. The Gronwall’s inequality, some Sobolev inequalities, and the monotonicity of the p-Laplacian operator defined by are required to establish the main result.

Recall that

and

are the standard spaces of Lebesgue and Sobolev, respectively, for

and

. For any Banach space

X, we define

to be the space of measurable functions

such that

for

and

if

.

is a Banach space [

12].

Proposition 2.1 (The differential form of Gronwall’s inequality [

13]).

- (i)

-

Let be a nonnegative, absolutely continuous function on , which satisfies for a.e. t the differential inequality

where and are nonnegative, summable functions on . Then

for all .

- (ii)

-

Proposition 2.2 (Poincaré’s inequality

[

13])

. Assume U is a bounded, open subset of . Suppose for some . Then we have the estimate

for each , the constant C depending only on and U.

In particular, for all ,

Next, we recall the Bounded Convergence Theorem.

Proposition 2.3 ([

14]).

If f is a Lebesgue measurable function defined on a closed, bounded interval [a,b], with its norm for defined by

If is a sequence of measurable functions and M is a positive constant such that

and a.e. then

for any p satisfying .

Now, we state the well-known Theorem.

Proposition 2.4 ([

15]).

The space is complete and separable if .

Proposition 2.5 (Jensen’s inequality)

[

16]

Let be a measure space with and let be a convex function defined on an open interval I in if is such that , then

Proposition 2.6 ([

17]).

If a sequence of continuous functions converges uniformly on to , then f is continuous on A.

3. Existence and Uniqueness

3.1. Existence

In this subsection, we will prove the existence of solutions to the integral equation (2).

Firstly, we choose the basis

defined as a subset of the eigenfunction of the Laplacian for the Dirichlet problem.

where

for

.

Since

is an orthonormal basis in

, then

is also an orthonormal basis in

. Then for

we can write

with

and the series

is converges in

.

Hence, the approximate solution

can be represented as follows

Moreover, we suppose that

satisfy the following approximating problem

for all

,

.

Remark 3.1. The coefficients can be chosen such that in .

Furthermore, we prove the lemma concerning the solution of approximate problem (

8).

Lemma 3.2.

There exists a positive constant independent on n, that satisfies the following inequality

for all .

Proof. Taking

and substituting into equation (

8), we obtain

The first term of (

9) can be written as follows

Computing the second integral of (

9) by the initial condition in (

8) leads us to

By substituting the integrals (

10) and (

11) into (

9), then integrating the equation (

9) from 0 to

t with respect to

, we have

Application of inequality (

3) to the left-hand side of (

12) leads us to the assertion of the lemma. The proof of the lemma is complete. □

Lemma 3.3. There exists at least one solution of the approximating problem (8) such that .

Proof.

Now, we represent the approximate equation (

8) in the following form

for

.

The substitution (

14) into (

15) gives

for

. We find the derivative of (

6) with respect to

t, then by (

13), the integral on the left-hand side of (

16) can be written as below

First integral on the right-hand side of (

16), we rewrite as follows

for

. Here

is bounded on

, since

with

constant numbers (see (

5)).

Equation in (

4) implies that

By equation (

20), we transform the second integral on the right-hand side of (

16) in the following way

for

.

Thus, substitutions (

17), (

18), and (

21) into (

16) lead us to the following homogeneous ordinary system of equations with respect to

t

for

.

Furthermore, we introduce the following notations

with

from (

19).

Therefore, by using our notations, the homogeneous system of ODE (

22) can be written as follows

Here

is the Hadamard product of two vectors specified by the following formula

Now we denote the right-hand side of(

23) by

F

The first term on the right-hand side of (

24) is the linear. The second term on the right-hand side of (

24) is a homogeneous system of ODE.

Now we denote the second term of (

24) by

.

So, equation (

23) can be rewritten as the homogeneous system of equations

We show that

is bounded and continuous.

Notice that

is bounded and continuous in

.

We only consider to prove that

is bounded and continuous at one point where

. So, each integrand

of the following integrals

is bounded, if

. By Lemma 3.2, we have

Equation (

12) implies that

. Hence,

is bounded in

. Then there exists sequence

that converges to

in

for

. Moreover, this sequence

satisfies the estimates

Consequently, there exist functions , such that and . Functions , are continuous and uniformly converge to , in for all . Then by the Proposition 2.6 on continuity of the sum of uniformly convergent series, functions , in are also continuous in for all . Thus, and .

Therefore, a system of equations (

26) satisfies the condition of the existence of the homogeneous system of ODE. The right-hand side of equations (

26)

is continuous for all

on the bounded domain

. Consequently, there exists a unique solution

of equation (

26) on

that satisfies the initial condition

or

for

.

The proof of the lemma is complete. □

We are now ready to prove the following lemma.

Lemma 3.4. There exists a weak solution of the equation (2) such that .

Proof. Thus, by Lemma 3.3 there exists a weak solution

of the approximating problem (

8) in

. Moreover, by Lemma 3.2 the sequence of functions

and

are bounded in

. Therefore, by Proposition 2.4, the sequence

has a subsequence that converges to some

. We denote this subsequence still by

, we obtain

which implies

for a.e.

t.

Since is complete space, then any has a limit such that . Since , hence . Therefore . □

4. Uniqueness

In the following lemma, we establish some auxiliary statements that we apply in the proof of Lemma 3.6.

Lemma 3.5. Let . Then there exists the positive number such that .

Proof. Since

, then the Embedding theorem

implies that

is continuous on

. Hence, by the Extreme Value theorem, if a function is continuous on a closed interval, it attains its maximum and minimum values on this interval. Consequently, there exists the positive number

such that

. □

Now we prove the uniqueness result.

Lemma 3.6. If , the integral equation (2) has a unique weak solution.

Proof. Assume that there exist two solutions of equation (

2),

and

. Taking

in the equation (

2) and denoting by

, we obtain

with

.

The first integral on the left-hand side of (

30) can be written as (

10)

Hence, the second integral of (

30) can be represented in the following way

By (

11), the first term on the right-hand side of equation (

32) equals zero.

By invoking Lemma 3.5, we bound the third integral on the right-hand side of (

32)

where

.

Integrating by parts the second term on the right-hand side of equation (

32), we have the same estimate as (

33),

So, we have the following estimate

for the second integral of (

30).

Furthermore, we bound the third term on the left-hand side of (

30). Therefore, we apply the following inequality [

18]

for

,

and

, to the last term of the equation (

30)

The left-hand side of (

35) can be written as follows

By Jensen’s inequality, we bound the norm in the last equation from below

The last inequality and the inequality (

35) implies that

By combining inequalities (

36), (

34) and (

31), the equation (

30) implies that

Using Poincare’s inequality (2.2) to the last inequality leads us

Combining the similar terms in the last inequality, we conclude that there exists a non-negative constant

K such that

with

.

To the inequality (

37) using Gronwall’s Inequality that stated in Proposition 2.1, we have that

. Thus, the solution of the problem (

9) is unique. The proof of the lemma is complete. □

4. Numerical Part

In this section, we first create a data set by solving numerically the Reynolds number with prescribed Power-law rheology parameters. The corresponding parameters and values for the Reynolds number are listed in

Table 1. Problem (

1) is solved using the finite element software COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0. To apply the software COMSOL, the equation in (

1) has been written in a standard form for the solver

where

and

. We construct the numerical solutions of problem (

1) taking coefficients

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

in the last equation. The Dirichlet boundary condition is applied on both ends of the computational domain.

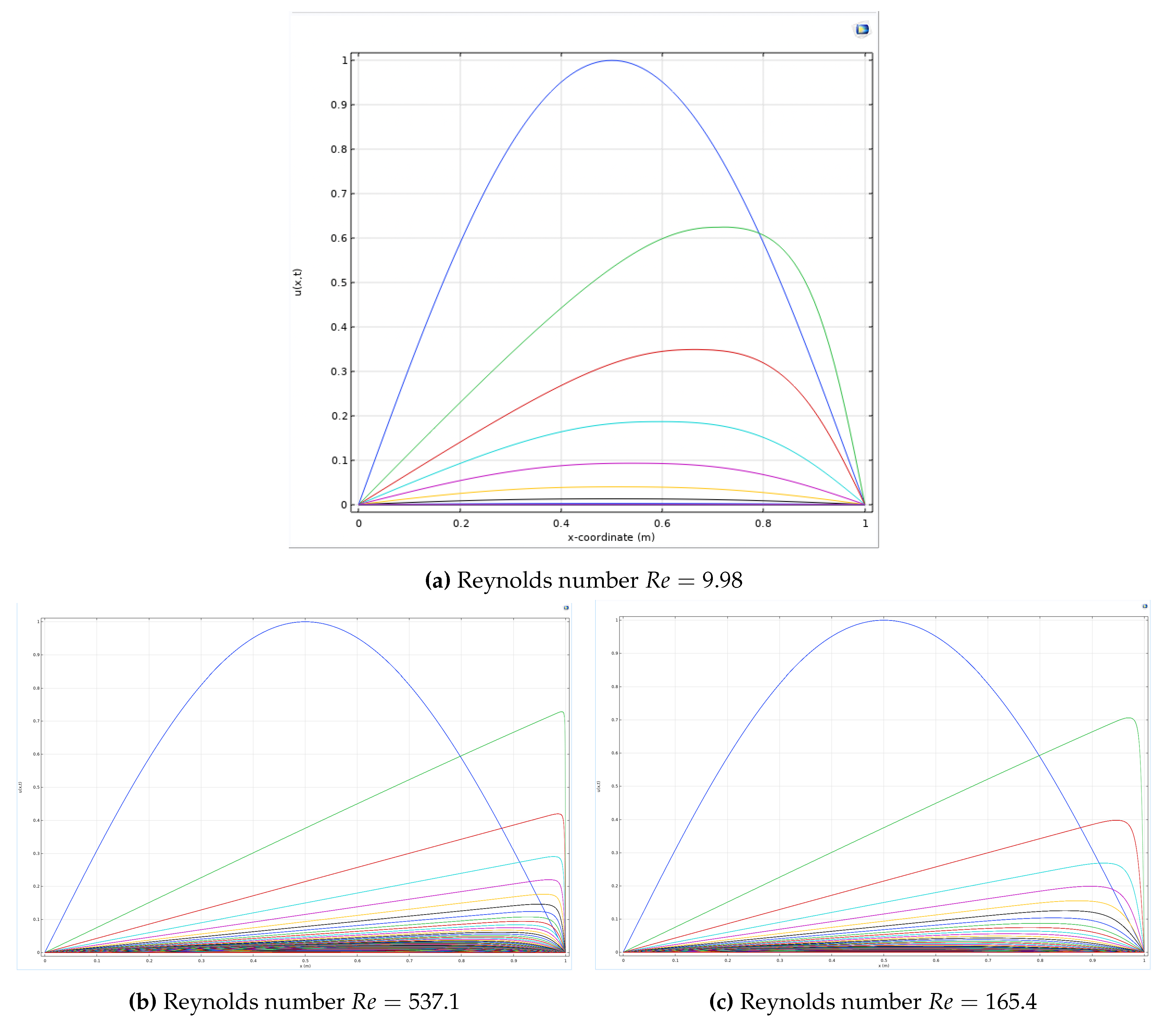

Figure 1 shows the simulated solutions obtained for the Burgers’ Equation based on a Power-law model with three different Reynolds numbers. In each case, the velocity profile has been shown for several instances of time. It can be observed that within a finite time

T, the solution

u and its derivative

are bounded in

, as predicted by our theoretical results.

5. Conclusions

This work proves the existence and uniqueness of weak solutions of the viscous Burgers equation for the isothermal flow of power-law non-Newtonian fluids with initial and boundary conditions. A numerical experiment on COMSOL Multiphysics was conducted, confirming the theoretical part.

Acknowledgments

The first and third authors are supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan Grant No. AP23489433.

References

- Burgers, J.M. A Mathematical Model Illustrating the Theory of Turbulence. Adv. Appl. Mech.. 1948, 1, 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R.B.; Armstrong, R.C.; Hassager, O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Volume 1: Fluid Mechanics; Wiley: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Jordan, P.M. A note on acoustic propagation in power-law fluids: Compact kinks, mild discontinuities, and a connection to finite-scale theory. Int. J. Nonlin. Mech. 2013, 48, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Borden, H. Traveling Wave Solutions of Burgers’ Equation for Power-law Non-Newtonian flows. Appl. Math. E-Notes. 2011, 11, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.A.; Fournier, J.J.F. Sobolev Spaces, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, E. The partial differential equation ut+uux=μuxx. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1950, 3, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruzhkov, S.N. First Order Quasilinear Equations in Several Variables. Math. USSR-Sb 1970, 10, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lions, J.L. Quelques Méthodes de Résolution des Problèmes aux Limites Non Linéaires; Dunod: Paris, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D. Existence and uniqueness of solutions to the stationary power-law Navier-Stokes problem in bounded convex domains. Proceedings of Dyn. Syst. Appl. 2001, 3, 611–618. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.D. On a quasi-linear parabolic equation occurring in aerodynamics. Q. Appl. Math. 1951, 9, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temam, R. Navier-Stokes Equations: Theory and Numerical Analysis; Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.: Amsterdam, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Benia, Y.; Sadallah, B. Existence of solutions to Burgers equations in domains that can be transformed into rectangles. Electr. J. Differ. Equ. 2016, 157, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L.C. Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, W.R. The Bounded Convergence Theorem. Am. Math. Mon. 1974, 81, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lions, P.L. The concentration-compactness principle in the calculus of variations. The locally compact case, part 1. Ann. Inst. Henri Poincare (C) Anal. Non Lineaire 1984, 1, 109–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, S.S.; Adil Khan M; Abathun A. Refinement of the Jensen integral inequality. Open Math. 2016, 14, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.K. An Introduction to Real Analysis. https://www.collegesidekick.com/study-docs/3018040 (accessed 2014).

- Lindqvist, P. Notes on the Stationary p-Laplace Equation, 1st ed.; SpringerBriefs in Mathematics: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).