Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Progress in Snow Trend Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Training Sample Processing and Labeling

3.2. Siamese Attention U-Net Architecture

3.3. The SSIM Index and the Contrastive Loss Function

3.4. Deriving the Frequency of Daily Snow Water Equivalent Change Events

3.5. SWE Change Point Detection

4. Result

4.1. Model’s Accuracy Metrics

4.2. Daily Snow Water Equivalent Change Events

4.3. Daily SWE Change Segments

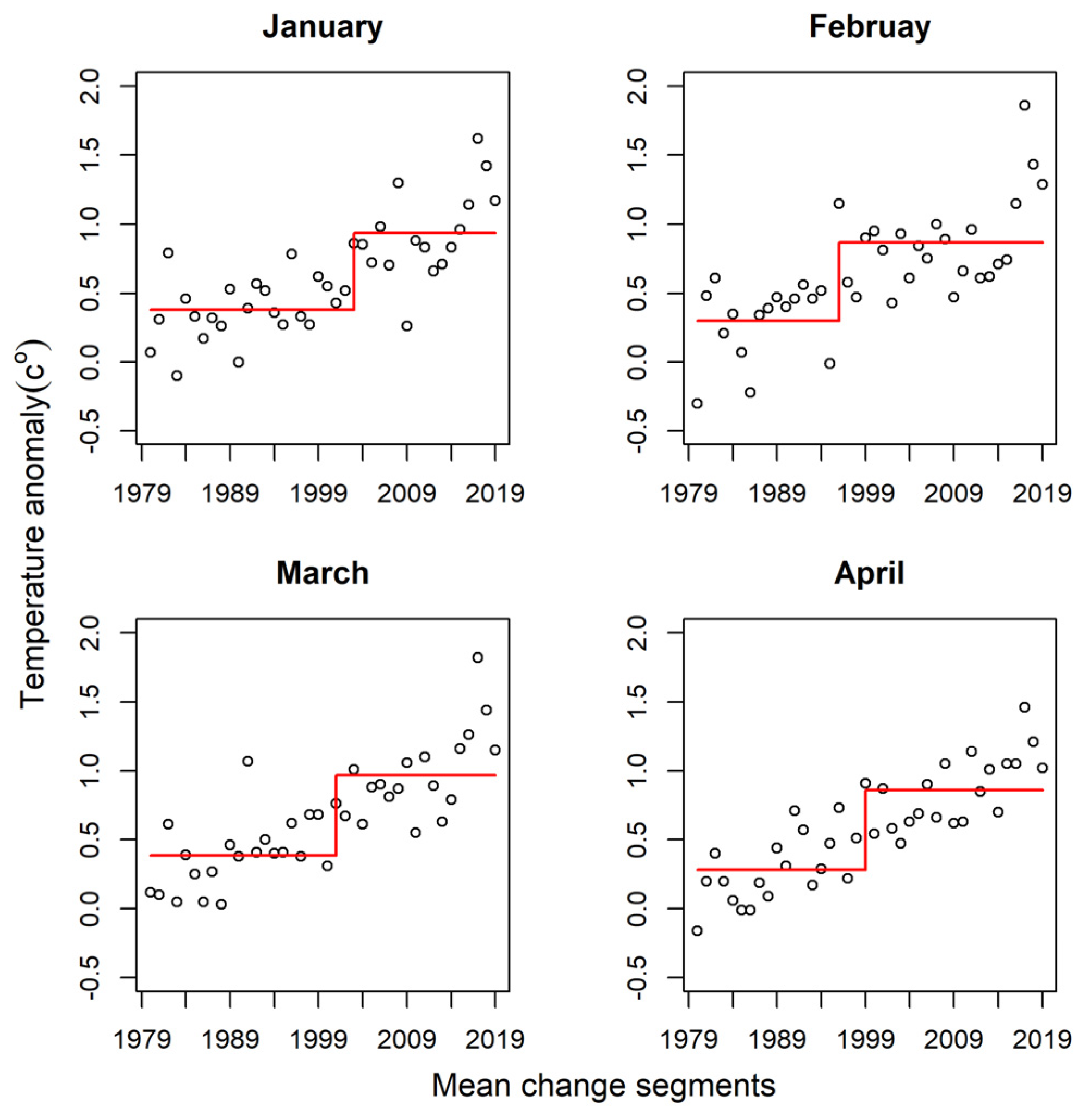

4.4. Temperature Anomaly

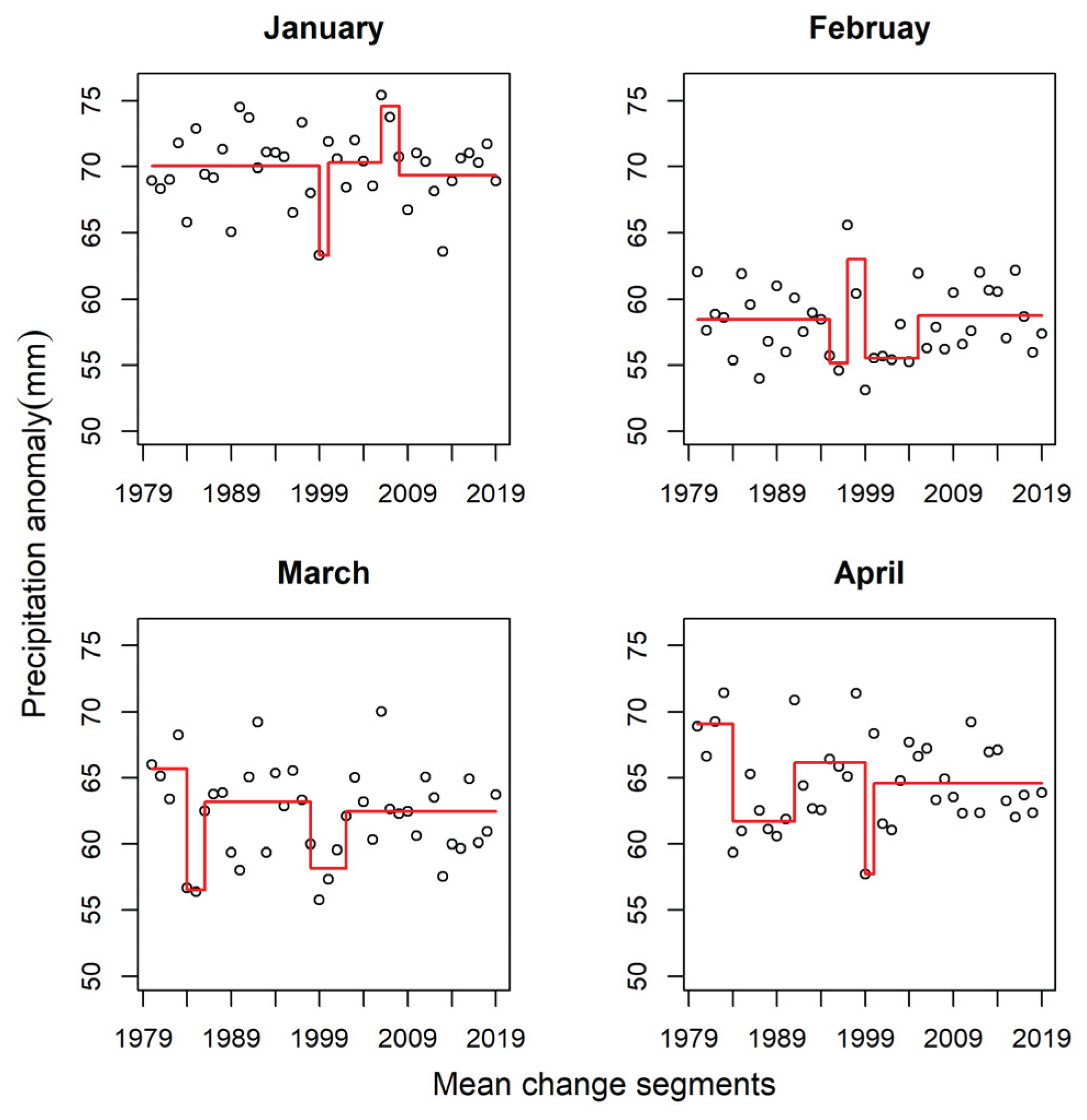

4.5. Precipitation Anomaly

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWE | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| SCE | Snow cover extent |

| SD | Snow depth |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

References

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Snow cover.Available:https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/snow-cover.html (Accessed on March 2025).

- Callaghan, T. V. et al., Multiple effects of changes in arctic snow cover, Ambio, vol. 40, no. SUPPL. 1, pp. 32–45, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Perovich, D.; Smith, M.; Light, B.; Webster, M. Meltwater sources and sinks for multiyear Arctic sea ice in summer, Cryosphere, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 4517–4525, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Graham, R.M.; Wang, K.; Gerland, S.; Granskog, M.A. Comparison of ERA5 and ERA-Interim near-surface air temperature, snowfall and precipitation over Arctic sea ice: effects on sea ice thermodynamics and evolution, Cryosphere, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1661–1679, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb A.R.; Mankin, J.S. Evidence of human influence on Northern Hemisphere snow loss, Nature, vol. 625, no. 7994, pp. 293–300, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eckerstorfer, M.; Vickers, H.; Malnes, E.; Grahn, J. Near-real time automatic snow avalanche activity monitoring system using sentinel-1 SAR data in Norway, Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 11, no. 23, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eckerstorfer, M.; Malnes, E.; Müller, K. A complete snow avalanche activity record from a Norwegian forecasting region using Sentinel-1 satellite-radar data, Cold Reg Sci Technol, vol. 144, pp. 39–51, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dierauer, J.R.; Allen, D.M.; Whitfield, P.H. Climate change impacts on snow and streamflow drought regimes in four ecoregions of British Columbia, Canadian Water Resources Journal, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 168–193, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.B.; Tague, C.L; Molotch, N.P. The Counteracting Effects of Snowmelt Rate and Timing on Runoff, Water Resour Res, vol. 56, no. 8, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.B.; Molotch, N.P; Livneh, B.; Harpold, A.A.; Knowles, J.F.; Schneider, D. Snowmelt rate dictates streamflow, Geophys Res Lett, vol. 43, no. 15, pp. 8006–8016, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Maurer, G.E.; Bowling, D.R. Seasonal snowpack characteristics influence soil temperature and water content at multiple scales in interior western U.S. mountain ecosystems, Water Resour Res, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 5216–5234, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Harpold, A.A.; Molotch, N.P. Sensitivity of soil water availability to changing snowmelt timing in the western U.S., Geophys Res Lett, vol. 42, no. 19, pp. 8011–8020, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Contosta, A.R.; Burakowski, E.A.; Varner, R.K.; Frey, S.D. Winter soil respiration in a humid temperate forest: The roles of moisture, temperature, and snowpack, J Geophys Res Biogeosci, vol. 121, no. 12, pp. 3072–3088, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Malik, K., McLeman, R.; Robertson, C.; Lawrence, H. Reconstruction of past backyard skating seasons in the Original Six NHL cities from citizen science data, Canadian Geographer, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 564–575, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hatchett, B.J.; Eisen, H.G. Brief Communication: Early season snowpack loss and implications for oversnow vehicle recreation travel planning, Cryosphere, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 21–28, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pulliainen, J. et al. Patterns and trends of Northern Hemisphere snow mass from 1980 to 2018, Nature, vol. 581, no. 7808, pp. 294–298, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mudryk, L.R.; Kushner, P.J.; Derksen, C.; Thackeray, C. Snow cover response to temperature in observational and climate model ensembles, Geophys Res Lett, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 919–926, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Fang, B.; Mudryk, L. Update of Canadian Historical Snow Survey Data and Analysis of Snow Water Equivalent Trends, 1967–2016, Atmosphere - Ocean, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 149–156, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mudryk, L. et al., Historical Northern Hemisphere snow cover trends and projected changes in the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble, Cryosphere, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 2495–2514, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mudryk, L.; Mortimer, C.; Derksen, C.; Chereque, A.E.; Kushner, P. Benchmarking of snow water equivalent (SWE) products based on outcomes of the SnowPEx+ Intercomparison Project, Cryosphere, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 201–218, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mankin, J.S.; Diffenbaugh, N.S. Influence of temperature and precipitation variability on near-term snow trends, Clim Dyn, vol. 45, no. 3–4, pp. 1099–1116, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, J. Warmer climate: Less or more snow? Clim Dyn, vol. 30, no. 2–3, pp. 307–319, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, C.W.; Derksen, C.; Fletcher, C.G.; Hall, A. Snow and Climate: Feedbacks, Drivers, and Indices of Change, Dec. 01, 2019, Springer. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E., Mote, P.W.; Bindoff, N.L.; Stott, P.A.; Robinson, D.A. Detection and attribution of observed changes in northern hemisphere spring snow cover, J Clim, vol. 26, no. 18, pp. 6904–6914, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liang, S.; Cao, Y.; He, T.; Wang, D. Observed contrast changes in snow cover phenology in northern middle and high latitudes from 2001-2014, Sci Rep, vol. 5, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kushner, P.J. et al., Canadian snow and sea ice: Assessment of snow, sea ice, and related climate processes in Canada’s Earth system model and climate-prediction system, Cryosphere, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1137–1156, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Derksen, C; Mudryk, L. Assessment of Arctic seasonal snow cover rates of change,” Cryosphere, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1431–1443, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, J. Changes in March mean snow water equivalent since the mid-20th century and the contributing factors in reanalyses and CMIP6 climate models, Cryosphere, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1913–1934, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, S. et al., Changing Arctic snow cover: A review of recent developments and assessment of future needs for observations, modelling, and impacts, Sep. 01, 2016, Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, J. Snow conditions in northern Europe: The dynamics of interannual variability versus projected long-term change, Cryosphere, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1677–1696, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Malik, K; Robertson, C. Structural Similarity-Guided Siamese U-Net Model for Detecting Changes in Snow Water Equivalent, Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 17, no. 9, p. 1631, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation, In International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, Cham., 2015, pp. 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, C.; Li, X.; Kim, H.J.; Wang, J. A full convolutional network based on DenseNet for remote sensing scene classification,” Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 3345–3367, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Zhang, X. An improved Res-UNet model for tree species classification using airborne high-resolution images, Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thomas. E. et al., Multi-Res-Attention UNet : A CNN Model for the Segmentation of Focal Cortical Dysplasia Lesions from Magnetic Resonance Images, IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, vol. XX, no. XX, pp. 1–1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Jiao, L. Remote Sensing Image Change Detection Based on Deep Multi-Scale Multi-Attention Siamese Transformer Network, Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, X. Where-and-When to Look: Deep Siamese Attention Networks for Video-Based Person Re-Identification, IEEE Trans Multimedia, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 1412–1424, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Long, X.; Zheng, Y. A transformer-based Siamese network and an open optical dataset for semantic change detection of remote sensing images, Int J Digit Earth, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1506–1525, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vionnet, V.; Mortimer, C.; Brady, M.; Arnal, L.; Brown, R. Canadian historical Snow Water Equivalent dataset (CanSWE, 1928-2020), Earth Syst Sci Data, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 4603–4619, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Brasnett, B.; Robinson, D. Gridded North American monthly snow depth and snow water equivalent for GCM evaluation, Atmosphere - Ocean, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Luojus K. et al., GlobSnow v3.0 Northern Hemisphere snow water equivalent dataset, Sci Data, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hu. Y., et al., A long-term daily gridded snow depth dataset for the Northern Hemisphere from 1980 to 2019 based on machine learning, Big Earth Data, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 274–301, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aalto, J.; Pirinen, P.; Jylhä, K. New gridded daily climatology of Finland: Permutation-based uncertainty estimates and temporal /trends in climate, J Geophys Res, vol. 121, no. 8, pp. 3807–3823, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, C. et al., Benchmarking algorithm changes to the Snow CCI+ snow water equivalent product, Remote Sens Environ, vol. 274, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Luojus K., et al., Investigating the feasibility of the globsnow snow water equivalent data for climate research purposes, vol. 19, pp. 4851–4853, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Luojus, K., et al., ESA Snow Climate Change Initiative (Snow_cci): Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) level 3C daily global climate research data package (CRDP) (1979 – 2020), version 2.0, Mar. 2022. doi: doi:10.5285/4647cc9ad3c044439d6c643208d3c494.

- Hancock, S.; Huntley, B.; Ellis, R.; Baxter, R. Biases in reanalysis snowfall found by comparing the JULES land surface model to globsnow, J Clim, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 624–632, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment : From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–14, 2004.

- Auger, I.E.; Lawrence, C.E. Algorithms for the optimal identification of segment neighborhoods,” 1989.

- Killick, R.; Fearnhead, P.; Eckley, I.A. Optimal detection of changepoints with a linear computational cost, J Am Stat Assoc, vol. 107, no. 500, pp. 1590–1598, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.Y.; Barry, R.G.; Gizaw, M.; Gobena, A.; Balaji, R. Changes in North American snowpacks for 1979-2007 detected from the snow water equivalent data of SMMR and SSM/I passive microwave and related climatic factors, Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, vol. 118, no. 14, pp. 7682–7697, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Erlat,E.; Aydin-Kandemir, F. Changes in snow cover extent in the Central Taurus Mountains from 1981 to 2021 in relation to temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric teleconnections,” J Mt Sci, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 49–67, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Luce, C. H. ; Lopez-Burgos, V.; Holden, Z. Sensitivity of snowpack storage to precipitation and temperature using spatial and temporal analog models, Water Resour Res, vol. 50, no. 12, pp. 9447–9462, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.Y.; Gobena, A.K.; Wang, Q. Precipitation of southwestern Canada: Wavelet, scaling, multifractal analysis, and teleconnection to climate anomalies, Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, vol. 112, no. 10, May 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ye,. K.; Wu, R. Autumn snow cover variability over northern Eurasia and roles of atmospheric circulation,” Adv Atmos Sci, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 847–858, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series. Available: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/global/time-series (Accessed: Mar. 08, 2025).

- Mote,P.W.; Li, S.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Xiao, M.; Engel, R. Dramatic declines in snowpack in the western US, NPJ Clim Atmos Sci, vol. 1, no. 1, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Barry, R. G.; Fallot, J.M.; Armstrong R. L. Twentieth-century variability in snow-cover conditions and approaches to detecting and monitoring changes: status and prospects.

- Huntington, T. G.; Hodgkins, G. A.; Keim, B. D.; Dudley, R. W. Changes in the Proportion of Precipitation Occurring as Snow in New England (1949-2000).

| Threshold | TPR | FPR | TNR | FNR | PR | F1-score | OA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40% | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 30.60 | 0.47 | 30.60 |

| 45% | 100.00 | 37.04 | 62.94 | 0.00 | 54.34 | 70.0 | 74.28 |

| 46% | 100.00 | 12.56 | 87.44 | 0.00 | 77.84 | 88.0 | 91.29 |

| 47% | 100.00 | 3.52 | 96.48 | 0.00 | 92.60 | 96.00 | 97.56 |

| 48% | 100.00 | 0.77 | 99.23 | 0.00 | 98.29 | 99.00 | 99.47 |

| 50% | 98.61 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 1.39 | 100.00 | 99.30 | 99.57 |

| Month | S | tau | p-Value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 7291 | 0.16 | 1.4 ×10-1 | 5.0 ×10-2 |

| February | 7128 | 0.13 | 2.7 ×10-1 | 3.0 ×10-2 |

| March | 7275 | 0.25 | 2.6 ×10-2 | 1.3 ×10-1 |

| April | 7310 | 0.38 | 7.9 ×10-4 | 2.7 ×10-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).