The Double-Edged Sword of ROS

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen-derived molecules with dual roles in biology. At low-to-moderate concentrations, they serve as essential signalling molecules in physiological processes, but at high concentrations, they become detrimental, contributing to pathology [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Cellular ROS levels can be elevated by exogenous factors (e.g., toxins, xenobiotics, radiation) and endogenous stressors (e.g., metabolic dysfunction, inflammation), potentially overwhelming the cell's antioxidant capacity and inducing oxidative stress (OS). OS is increasingly recognized as a common factor in the pathogenesis of numerous noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disorders [

3,

12,

13,

14], neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's [

15,

16,

17] and Alzheimer's [

18], diabetes mellitus [

19,

20], aging [

3,

12,

13,

14,

21,

22], neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's [

15,

16,

17] and Alzheimer's [

18], diabetes mellitus [

18], aging [

19], and various cancers [

23]. NCDs constitute a major global health burden, responsible for a significant proportion of deaths worldwide, with projections indicating a continued rise due to factors like population aging and lifestyle changes. This trend poses substantial threats to public health and economic stability, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Current therapeutic strategies typically address NCDs individually. However, targeting the shared pathology of OS could offer a more comprehensive approach [

3,

5,

24]. Despite this rationale, clinical trials employing general antioxidant therapies (e.g., vitamins C and E, glutathione precursors) have largely failed to demonstrate significant clinical benefits [

2,

3,

5,

9,

25,

26]. A primary reason for this failure is likely their non-specific scavenging action, which reduces detrimental ROS but also impairs essential physiological ROS signalling. This highlights the critical need to identify and selectively target the specific mechanisms that amplify ROS to pathogenic concentrations, thereby preserving necessary basal ROS functions. This review synthesizes recent advances to propose a unified mechanism underlying ROS amplification in various pathological conditions. We focus specifically on how ionic signals (Ca²⁺ and Zn²⁺) orchestrate inter-organelle crosstalk between the plasma membrane, lysosomes, mitochondria and the nucleus to exacerbate ROS production and inflict organelle and cellular damage. We will conclude by discussing the potential of targeting this newly elucidated signalling axis to develop broad-spectrum therapeutics capable of mitigating multiple OS-associated diseases and potentially improving the healthspan-to-lifespan ratio during aging.

Maintaining Redox Balance: Production vs. Defence

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) encompass various reactive oxygen derivatives, including free radicals (e.g., superoxide, O₂•⁻; hydroxyl radical, •OH) and non-radicals (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, H₂O₂). While O₂•⁻ and particularly H₂O₂ are key mediators of physiological redox signalling, the highly reactive •OH is primarily implicated in oxidative damage [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

26]. Healthy cells meticulously maintain redox homeostasis—a dynamic balance between ROS production and elimination. ROS are physiologically generated at numerous subcellular sites, including mitochondria (primarily the electron transport chain), peroxisomes, the endoplasmic reticulum, and by plasma membrane-associated NADPH oxidases (NOX enzymes), contributing to processes like cell proliferation and differentiation, host defence, and metabolic adaptation. However, under stress conditions, some sites can significantly increase their ROS generation rate [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

26].

To counteract excessive ROS accumulation, cells possess sophisticated defence mechanisms [

3,

5,

11,

22,

26,

27,

28]. Firstly, antioxidant enzymes rapidly metabolise ROS, including superoxide dismutases (SOD1-3, converting O₂•⁻ to H₂O₂), catalase and glutathione peroxidases (neutralizing H₂O₂), and peroxiredoxins (Prx1-6) alongside the thioredoxin system (reducing peroxides). Secondly, non-enzymatic antioxidants like glutathione (GSH), vitamins C and E, coenzyme Q10, NADPH, and bilirubin directly neutralize ROS. Thirdly, organelle membranes (mitochondria, peroxisomes, endosomes, ER) act as physical barriers limiting the diffusion of highly reactive species like O₂•⁻ and •OH, restricting unwanted cytoplasmic oxidation. Ultimately, whether ROS exert physiological signalling effects (eustress) or cause detrimental damage (distress) depends critically on the specific ROS molecule, its concentration, subcellular location, and lifetime.

From Eustress to Distress: Crossing the Redox Signalling Threshold

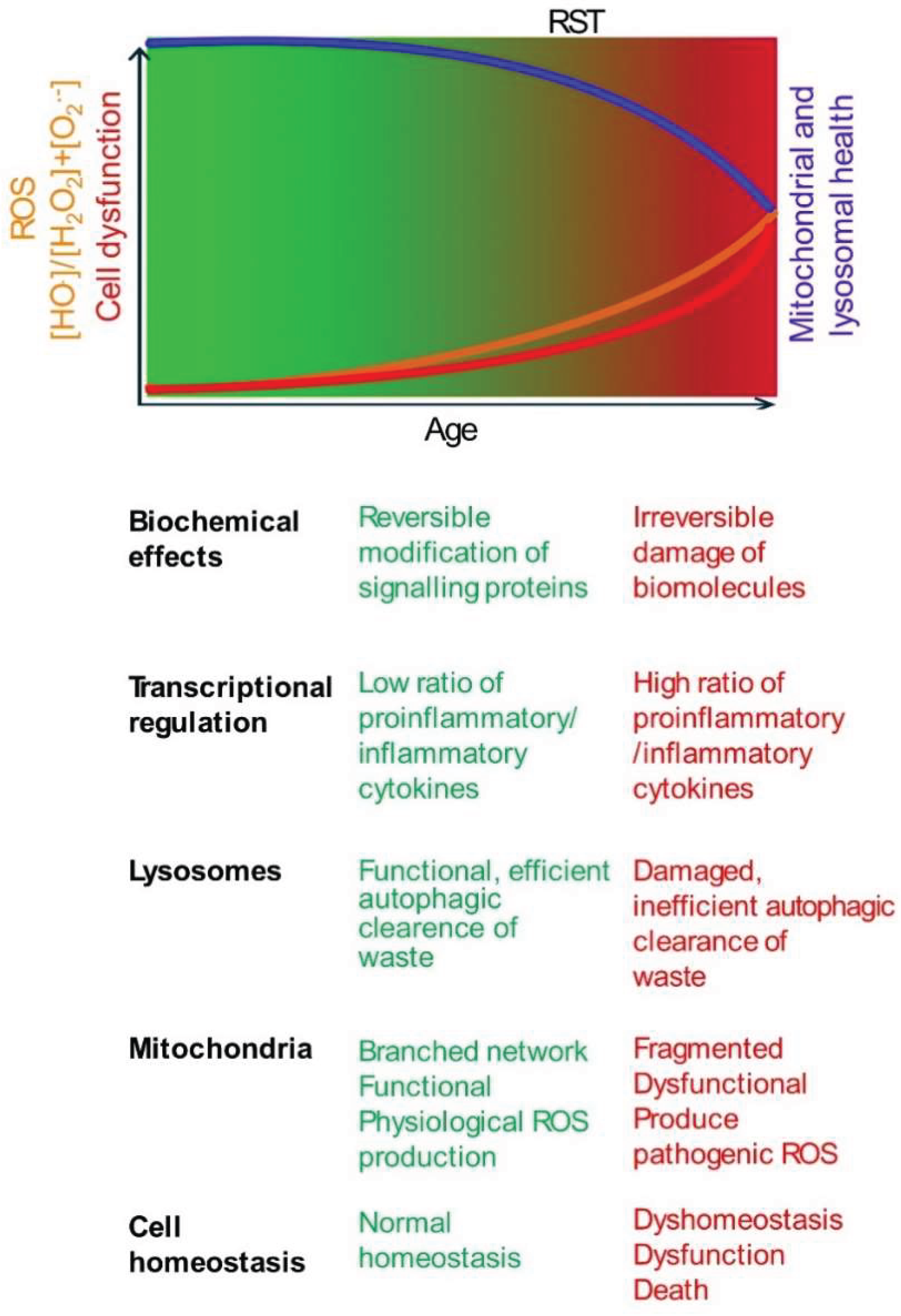

ROS exhibit a dichotomous role, acting as both essential signals and potential mediators of damage. This duality is sometimes conceptualized by the "redox stress signalling threshold" (RST), distinguishing beneficial "oxidative eustress" from harmful "oxidative distress"[

29] (

Figure 1). For clarity, this review primarily uses the historically used term, "oxidative stress" (OS) to refer to oxidative distress.

Below the RST, physiological ROS signalling supports cellular homeostasis and adaptation [

11,

29]. This involves regulating enzyme activity and gene expression through reversible oxidation of critical cysteine thiols (-SH) in regulatory proteins, primarily mediated by species like H₂O₂. Key adaptive pathways include those governed by transcription factors Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2), which upregulates antioxidant defences, and AP-1 (activator protein 1), involved in proliferation and differentiation. Physiological ROS levels can also activate DNA repair enzymes to sustain genomic stability [

11,

29].

However, with age, susceptibility to chronic diseases increases. This is associated with an increase in ROS levels beyond the RST towards oxidative distress, characterized by an increased ratio of highly reactive species like •OH relative to signalling molecules like H₂O₂ [

11,

29]. Unlike reversible modifications in eustress, •OH causes irreversible damage, including DNA strand breaks, protein oxidation leading to misfolding/aggregation, and lipid peroxidation compromising membrane integrity [

6,

9,

11]. Consequently, gene expression patterns shift, often favouring pro-inflammatory pathways (e.g., via NF-kB activation) while potentially suppressing adaptive responses governed by factors like Nrf2 [

6,

11,

29]. This maladaptive shift, by overwhelming repair mechanisms and chronically activating damaging pathways, accelerates cellular dysfunction, promotes chronic inflammation, contributes to aging, and underlies many age-related diseases [

6,

11,

29]. Notably, in conditions with genetic predispositions or specific environmental triggers (e.g., Type 1 diabetes, Parkinson's disease), these detrimental changes can manifest earlier in life [

15,

20].

This schematic illustrates the concept of RST. The gradient represents the increase in oxidative stress with age. RST is a conceptual boundary marking the transition from oxidative eustress (green) to distress (red). As age progresses, ROS levels (orange line) gradually rise, but any decline in mitochondrial and lysosomal functions (blue line) may not significantly impact cell function and viability (red line), until ROS production exceeds the RST. The age of onset varies based on genetic and environmental factors. Below the schematic, key biochemical and cellular changes associated with low (eustress) and high (distress) ROS levels are summarized.

Mitochondrial and Lysosomal Contributions to Oxidative Distress

Accumulating evidence indicates that mitochondria and lysosomes play crucial roles in ROS signalling in both health and disease [

20,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The quality, quantity, and function of mitochondria decline with aging and chronic diseases as ROS levels increase [

21,

30,

33,

39,

41]. In healthy cells, mitochondrial health is maintained through a dynamic balance of fission (division) and fusion (merging) for quality control [

21,

33,

39] . Fission segregates damaged components, while fusion mixes contents to restore function. Dysfunctional mitochondrial fragments are typically removed by lysosomes via selective autophagy (mitophagy) [

21,

33,

39]. The lost mitochondrial density and quality is restored by the biogenesis of new mitochondria, regulated by PGC1-α (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha) transcription of genes involved in mitochondrial quality control [

21,

33,

42].

Similarly, lysosomes undergo fusion and fission. They fuse with other organelles to acquire essential components and acidity required for their function [

43,

44]. Dysfunctional lysosomes are removed by selective autophagy (lysophagy) [

45,

46]. Lost lysosomes are replaced through biosynthesis, where the Ca²⁺-dependent transcription factor TFEB (Transcription Factor EB) plays a crucial role [

47,

48,

49]. Thus, dynamic regulation of both mitochondrial networks and lysosomes maintains their density, shape, size, composition, and function. This dynamic regulation is compromised during aging and chronic diseases, leading to a decline in the structural and functional integrity of both organelles [

21,

30,

32,

33,

39,

43,

44,

50,

51,

52].

Excessive mitochondrial fragmentation, bioenergetic failure, and increased ROS production are well-established hallmarks of aging and numerous diseases. Similarly, a decline in lysosomal numbers and function are emerging features of many diseases, especially neurodegenerative diseases [

31,

32,

37,

40,

41,

47,

50,

53,

54,

55]. Notably, the two organelles support each other in quality control [

56,

57]. Mitochondria supply ATP to support lysosomal function, while lysosomes clear dysfunctional mitochondrial debris, supporting efficient bioenergetic function of mitochondria. This cooperation is gradually lost during aging and various diseases, resulting in both organelles contributing to damaging ROS production rather than supporting each other's function. Paradoxically, the excess ROS they generate results in their own destruction.

Compelling evidence links coupled mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction to ROS imbalance and chronic disease pathogenesis, particularly neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Familial PD forms are associated with mutations in genes critical for mitochondrial dynamics and quality control (e.g.,

PARK2 encoding Parkin,

PINK1) and lysosomal function or autophagy (e.g.,

GBA1 encoding β-glucocerebrosidase,

PARK9 encoding ATP13A2). Mutations affecting mitochondrial integrity impact lysosomes, and conversely, lysosomal protein mutations affect mitochondria, reflecting their functional relationship. Pathological oxidative stress impact is evident in post-mortem PD brains, showing accumulated ROS-damaged biomolecules and autophagic vacuoles. Excessive mitochondrial ROS production and defective mitophagy also characterize idiopathic (sporadic) PD [

58]. A recent seminal study has reported mitochondrial plaques (spatially associated with Aβ plaques) within or outside of lysosomes in AD mouse models and human brains [

59]. These studies highlight the importance of investigating the interplay between mitochondria and lysosomes, rather than studying each separately.

A critical, incompletely answered question is the precise mechanism triggering the switch from physiological ROS production to sustained, pathological ROS amplification across the redox signalling threshold in diverse chronic stress conditions. An associated question is how this is linked to the interplay between mitochondria and lysosomes. Addressing these questions is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies that selectively curb excessive ROS production while preserving essential basal redox signalling. The following sections review key cellular ROS sources and proposed mechanisms driving pathological amplification.

Cellular Sources of Reactive Oxygen Species

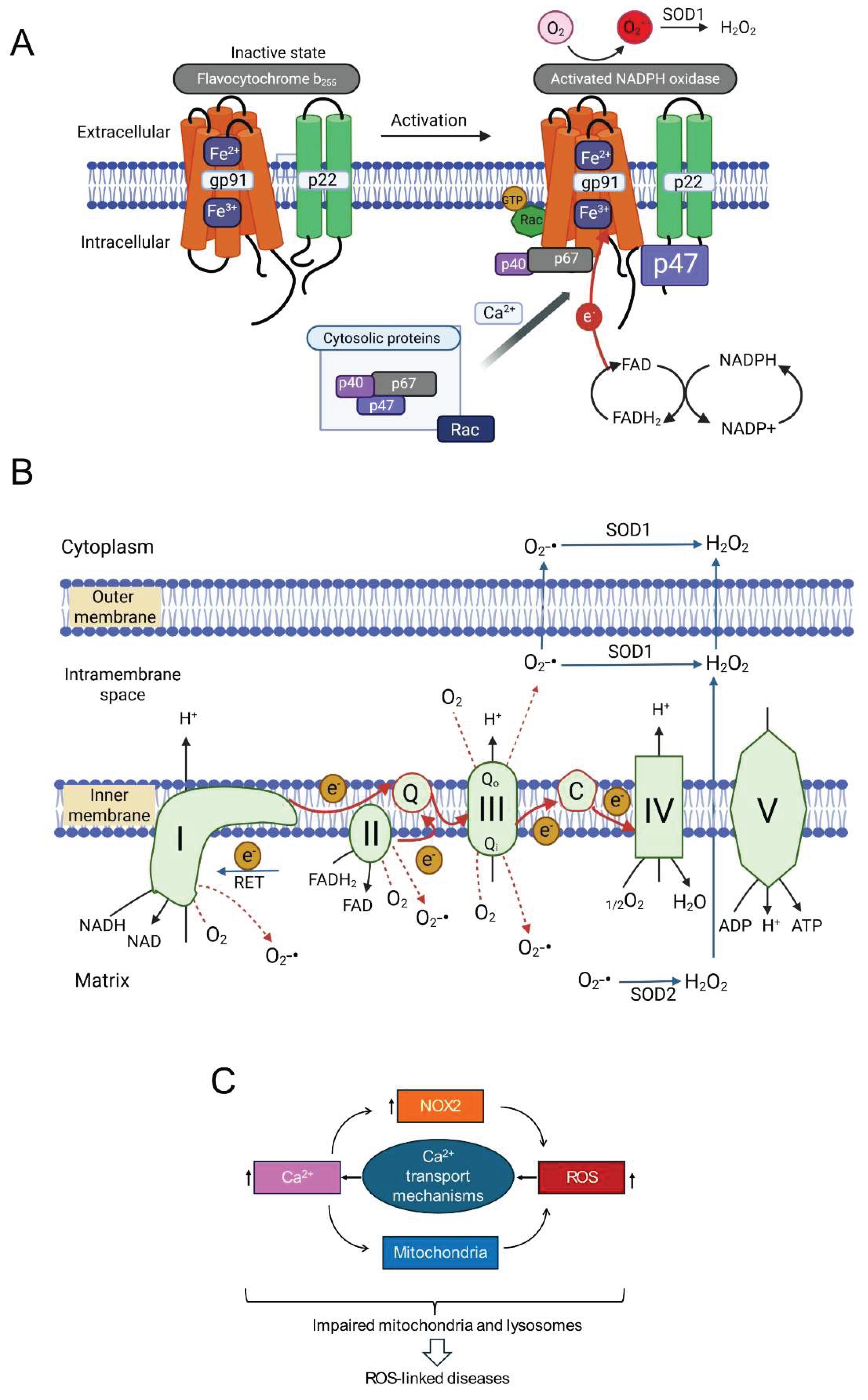

Cells contain numerous redox-active proteins capable of transferring electrons, often from NADH and NADPH, to molecular oxygen (O₂), initially generating the superoxide radical (O₂•⁻). This O₂•⁻ can then be converted enzymatically (e.g., by SODs) or non-enzymatically into other ROS, including signalling H₂O₂ or damaging •OH. Many ROS-generating proteins are membrane-associated and utilize redox-active metal ions (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ or Cu⁺/Cu²⁺) or organic cofactors (FMN, FAD, heme, pterins). Among the most significant contributors, particularly in pathology, are the NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzyme family and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) respiratory complexes. Lysosomes also contribute significantly to ROS production, albeit indirectly.

NADPH Oxidases (NOX Enzymes)

The human NOX family comprises NOX1-5 and the dual oxidases DUOX1/2 [

60,

61,

62]. These transmembrane proteins primarily function in regulated ROS generation. All NOX enzymes share a core structure with a membrane-embedded domain housing heme groups and a cytoplasmic dehydrogenase domain containing NADPH and FAD binding sites. This facilitates electron transfer from NADPH via FAD to heme groups, which then transfer electrons across the membrane to O₂, producing O₂•⁻ (

Figure 2A) [

60,

62,

63]. DUOX proteins possess additional domains.

From a pathophysiological perspective, NOX2 (gp91phox) is particularly important. Unlike some isoforms, NOX2 activity requires multi-subunit complex assembly. In resting cells, the catalytic subunit (gp91

phox) resides in the membrane, often with p22

phox. Regulatory subunits (p40

phox, p47

phox, p67

phox, and Rac GTPase) are cytoplasmic. Upon stimulation (e.g., increased intracellular Ca²⁺), these cytosolic subunits translocate and assemble with the core, forming the active enzyme. Activated NOX2 typically releases O₂•⁻ extracellularly. Extracellular SOD3 converts this to H₂O₂, which can enter the cell via aquaporins or diffusion [

60,

61,

62,

63]. While crucial for phagocytic host defence [

64], accumulating evidence implicates NOX2-derived ROS in NCD pathogenesis, including inflammation, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegeneration [

60,

61,

62,

65,

66].

Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain

Mitochondria are metabolic hubs and major producers of ROS. Most mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) originate from electrons leaking prematurely from electron transport chain (ETC) complexes (I, II, III, IV) in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) (

Figure 2B). During oxidative phosphorylation, electrons from NADH and FADH₂ pass along the ETC to O₂, reducing it to H₂O at Complex IV. This electron flow drives proton pumping, generating the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨmt) for ATP synthesis [

1,

67,

68].

Electron escape primarily occurs from intermediates within Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and Complex III (ubiquinol:cytochrome

c oxidoreductase), reacting directly with O₂ to produce O₂•⁻ (forward electron transport, FET leakage). Under conditions like ischemia-reperfusion (substrate accumulation, high mitochondrial membrane potential), electrons can flow backward from Complex II through Complex I (reverse electron transport, RET), becoming a major source of O₂•⁻ from Complex I [

1,

69]. Determining the relative contributions of FET (Complexes I/III) versus RET (Complex I) to signalling is challenging due to the functional and physical linkage of these complexes within the IMM. Knockout studies showed that genetic deletion of one complex can impact ROS production from the other [

70], while biochemical studies reported that complex III supports the assembly of individual complexes into a super-complex [

71].

Although historically the focus has been on complex I, recent studies highlight the role of Complex III in ROS generation during chronic stress [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Ubiquinone facilitates electron transfer from Complexes I and II to Complex III by transitioning between its oxidized form (ubiquinone, Q) and its reduced form (ubiquinol, QH₂) via a semiquinone intermediate (Q•⁻). Chronic stress by reducing mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨmt) can alter the redox state of the ubiquinone pool, increasing the lifespan of reactive Q•⁻, leading to increased electron leak and O₂•⁻ production. Reduced ΔΨmt (depolarization) may favour FET-based ROS production from Complex III over RET from Complex I, suggesting that mechanisms of ROS production may be different between chronic and acute stress conditions. Although the recent pharmacological tools (e.g., S1QELs for Complex I, S3QELs for Complex III) have provided valuable insights into the roles of complexes [

7], complex feedback mechanisms between the complexes might complicate the interpretation of the findings [

70,

71].

A key difference between the two complexes is the topology of ROS release. Complex I releases O₂•⁻ to the matrix side, while Complex III has two sites (Qo and Qi) that release O₂•⁻ to the intermembrane space (IMS) and matrix, respectively. Most O₂•⁻ from Complex III is released into the IMS, where it can be converted to H₂O₂ by IMS-localized SOD1 and diffuse into the cytoplasm [

78,

79]. Some O₂•⁻ may exit into the cytoplasm via the outer membrane VDAC (voltage dependent anion channel) [

78]. This suggests Complex III might more readily release damaging ROS into the cytoplasm under chronic stress. Thus, Complexes I and III are primary ETC sites implicated in enhanced ROS production during stress, with context-dependent mechanisms and contributions.

Lysosomes: Indirect Contributors to ROS Generation

As mentioned, dysfunctional lysosomes contribute significantly to cellular ROS burden indirectly and disease aetiology. By failing to clear autophagosomes containing damaged mitochondria, protein aggregates (which can trigger ROS or sequester antioxidants), or damaged lysosomes themselves, they allow OS sources to accumulate [

31,

32,

41,

43,

53,

55,

80,

81]. Clinical evidence supports this: protein aggregate accumulation (Aβ, α-synuclein, mutant Huntingtin) and autophagosome buildup in neurodegenerative diseases are linked to impaired lysosomal-autophagic clearance and increased OS [

31,

32,

53,

55,

80,

82].

Interestingly, lysosomes sense and respond to acute ROS increases. ROS can trigger Ca²⁺ release from lysosomal stores via the MCOLN1 (TRPML1) channel, which acts as a ROS sensor. This lysosomal Ca²⁺ release can activate TFEB, a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, potentially representing a protective feedback mechanism [

41,

80]. However, under chronic, overwhelming OS, this adaptive response may become insufficient.

Lysosomes can also be minor direct ROS sources during enzymatic degradation. More critically, severe or chronic OS can destabilize lysosomal membranes, causing lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) or rupture resulting in the release of acidic hydrolases (e.g., cathepsins) and stored metal ions (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺, Zn²⁺) into the cytoplasm [

31,

54,

83]. Released cathepsins can cleave proteins, activate apoptosis, and trigger inflammasomes, promoting inflammatory responses that further increase ROS. Released ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) is particularly dangerous, catalysing the Fenton reaction with H₂O₂ to generate highly damaging •OH [

9,

26]. These findings highlight that maintaining both mitochondrial and lysosomal integrity is crucial for preventing runaway OS and disease progression.

Amplifying the Damage: ROS-Induced ROS Production (RIRP)

It is increasingly evident that the simultaneous or sequential activation of multiple reactive oxygen species (ROS) sources, coupled with positive feedback, is often necessary to elevate ROS levels to pathogenic concentrations. A key concept is "ROS-induced ROS production" (RIRP), where an initial oxidative insult triggers cellular responses that lead to further ROS generation, creating a self-perpetuating vicious cycle. This feedback loop is believed to significantly contribute to aging and many chronic diseases [

84].

Given the multiple cellular ROS sources, numerous RIRP pathways involving crosstalk between organelles and enzymes are possible. However, emerging evidence highlights a particularly important self-amplifying loop involving the interplay between NOX enzymes (especially NOX2) and mitochondrial ROS production [

76,

84,

85]. In this loop, NOX-generated ROS stimulates mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) and vice versa. Supporting the causal role of NOX-mitochondria interplay in oxidative stress (OS)-linked diseases, therapeutic strategies that interrupt this cycle (e.g., specific NOX inhibitors, mitochondria-targeted antioxidants like MitoQ) [

3,

5,

25,

26,

86] show robust preclinical promise. However, clinical translation faces hurdles: achieving selectivity for pathological sources, ensuring bioavailability, and crucially, avoiding the suppression of essential physiological ROS signalling. Similarly, trials using general antioxidants have largely failed, likely due to their inability to selectively target pathological ROS overproduction and potential interference with essential signalling [

9,

25,

26].

These observations underscore the clinical need for a deeper mechanistic understanding of RIRP. Specifically, how does NOX-derived ROS signal to mitochondria to stimulate mtROS, and how does mtROS feedback to sustain NOX activity or activate other sources? Elucidating these pathways is crucial for designing more effective, selective therapies that break the pathological ROS amplification cycle without disrupting normal redox homeostasis.

Ionic Messengers in RIRP: The Roles of Ca²⁺ and Zn²⁺

Intricate crosstalk between calcium (Ca²⁺) signalling and ROS production is well-established [

87,

88]. Ca²⁺ and ROS often form a positive feedback loop: elevated intracellular Ca²⁺ can stimulate ROS production (from mitochondria, NOX enzymes), while ROS can modulate Ca²⁺ channels and pumps, further increasing intracellular Ca²⁺ [

88]. Given that Ca²⁺ activates/modulates both NOX2 and mitochondrial metabolism (influencing mtROS), integrating Ca²⁺-ROS crosstalk into the RIRP framework is logical. This suggests a potential three-way positive feedback loop involving NOX2-derived ROS, mtROS, and intracellular Ca²⁺ signals (

Figure 2C), potentially driving a self-reinforcing cycle in pathology.

Several Ca²⁺ channel types mediate ROS effects on Ca²⁺ influx or release, including voltage-gated channels, ligand-gated channels (NMDA receptors), store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) channels, and Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels [

87,

88]. Among TRP channels, TRPM2 (Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2) emerges as particularly important due to its direct sensitivity to OS-generated molecules and its established role in promoting OS-related damage in numerous cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic disease models [

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96].

The TRPM2 Channel: A Key Ca²⁺ Conduit in Oxidative Stress

TRPM2 is a non-selective cation channel (permeable to Na⁺, K⁺, and notably, Ca²⁺) belonging to the Melastatin TRP subfamily. Functional channels are tetramers of identical subunits, each with six transmembrane segments forming the pore and large intracellular N- and C-termini. Uniquely, TRPM2 gating is synergistically activated by adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADPR) binding to the C-terminal NUDT9-H domain and Ca²⁺ binding to an N-terminal site [

92,

93,

97] [

98]. ADPR production significantly increases during OS. Oxidants like H₂O₂ cause DNA damage, activating poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes. PARP uses NAD⁺ to generate poly(ADP-ribose) polymers; subsequent hydrolysis releases free ADPR. Thus, OS indirectly increases intracellular ADPR, which, with permissive intracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations, triggers TRPM2 opening and extracellular Ca²⁺ influx [

92,

93,

97].

TRPM2 channels are expressed widely (neurons, cardiomyocytes, pancreatic β-cells, kidney, liver, endothelial cells, immune cells) and implicated in diverse processes (temperature sensation, immune activation, insulin secretion, apoptosis) [

89,

92,

93,

94,

99]. Paradoxically, TRPM2 activation, requiring ROS-dependent ADPR generation, often leads to downstream events that further exacerbate ROS production in most cell types examined [

76,

100,

101]. This ability to amplify OS appears central to its role in mediating OS-induced cellular dysfunction and apoptosis in various NCDs, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Additionally, TRPM2 channels upregulated in cancer and their activation is linked to cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [

102,

103,

104].

Zinc Dyshomeostasis and Mitochondrial ROS

Besides Ca²⁺, considerable evidence implicates zinc (Zn²⁺) dyshomeostasis in mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production in OS-linked pathologies [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112]. Zn²⁺ is an essential micronutrient, acting as a cofactor or structural component for numerous proteins (potentially >2000), critical for enzyme catalysis, protein structure, gene transcription, and signalling. Most intracellular Zn²⁺ is tightly bound (e.g., to metallothioneins, high-capacity buffers) or sequestered within organelles (ER, Golgi, synaptic vesicles, lysosomes) [

105,

110,

111,

113]. Consequently, free cytoplasmic Zn²⁺ concentration is maintained at very low levels (picomolar to low nanomolar) physiologically [

105,

107,

108,

110,

111]. This tight control involves coordinated action of Zn²⁺ transporters: ZIP family (SLC39A) generally facilitates cytoplasmic influx, while ZnT family (SLC30A) promotes cytoplasmic efflux [

105,

113].

Although essential, disruptions leading to either deficiency or excess labile Zn²⁺ in specific compartments are strongly linked to pathology. Notably, elevated intracellular Zn²⁺ is frequently associated with increased mtROS and subsequent cell damage/death in models of neurodegeneration, stroke, and other OS-related conditions [

105,

111,

113,

114]. The precise mechanisms by which excess Zn²⁺ leads to mtROS have been of considerable interest.

Integrating the Pieces: Towards a Unified Mechanism

Previous sections established that common hallmarks of stress responses in aging and related diseases include elevated OS (potentially RIRP-driven), mitochondrial damage (fragmentation, decline) [

3,

30,

33,

34,

52,

115,

116], lysosomal impairment (defective autophagy, leakage) [

32,

37,

41,

43,

47,

55,

80,

83,

117], and disrupted ionic signalling (Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺) [

87,

88,

118,

119] [

105,

107,

109,

111]. Literature provides evidence for pairwise connections: lysosome-mitochondria interplay [

49,

56,

57,

81]; NOX-mitochondria crosstalk in RIRP [

76,

85,

120]; Ca²⁺-ROS positive feedback [

88]. However, a key unresolved question is whether these disparate events are interconnected through a common underlying pathway. Could a single integrated mechanism explain how an initial stressor triggers this detrimental cascade across multiple organelles? Herein, we synthesize recent research to propose a unified mechanism integrating various signalling molecules with inter-organelle crosstalk to promote ROS amplification to cytotoxic levels.

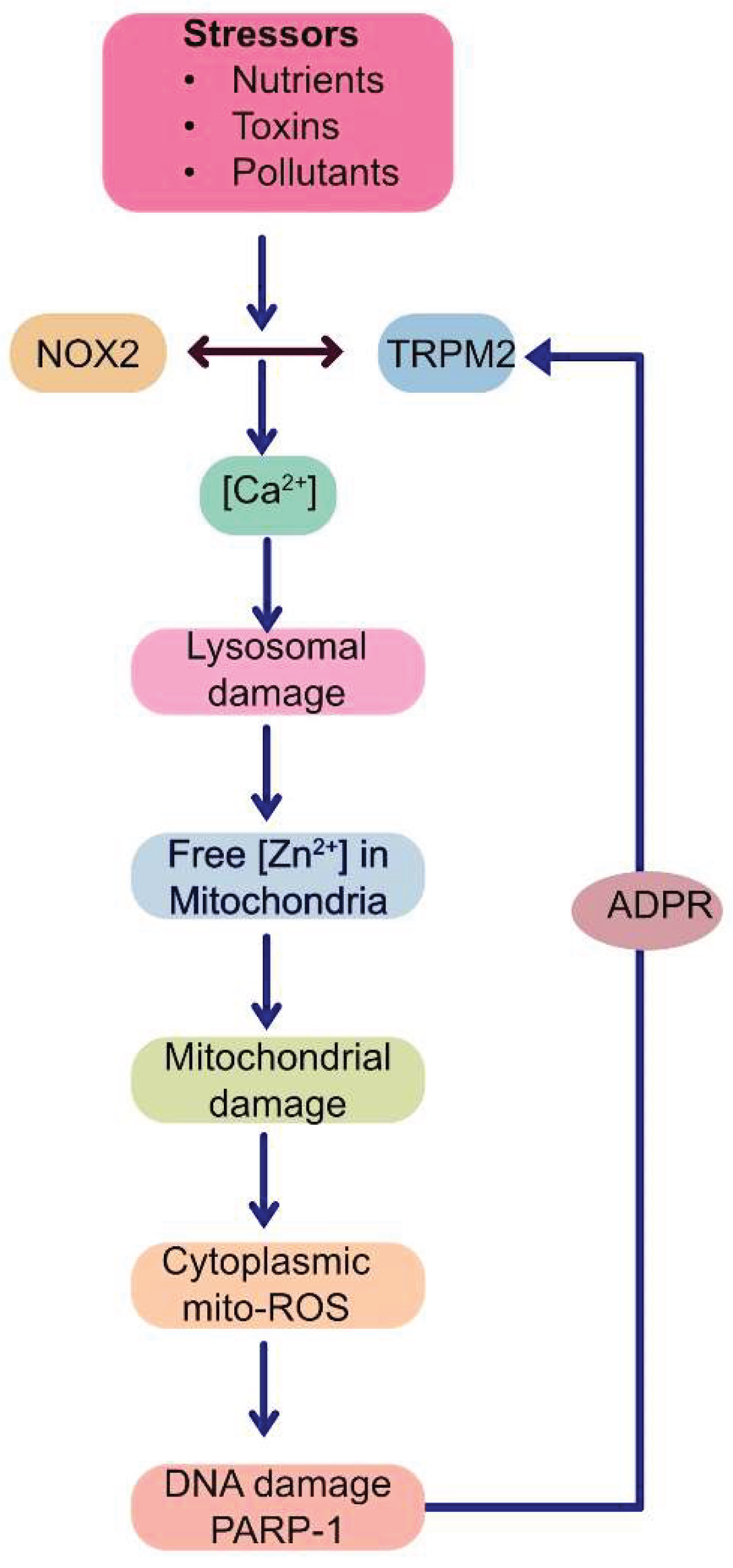

A Unified Vicious Cycle: Inter-Organelle Crosstalk Drives Pathological ROS Amplification

Evidence for the unified mechanism depicted schematically in

Figure 3 emerges from diverse cellular models of chronic stress: high glucose (diabetic stress mimic) on endothelial cells [

100]; free fatty acids (metabolic stress mimic) on pancreatic β-cells [

101]; Parkinsonian toxin (MPP⁺) on neuroblastoma cells [

100]; and oxidative stress (H₂O₂) on HEK-293 cells conditionally expressing TRPM2 channels [

76,

100]. These models respectively represent hypertension, type-2 diabetes, Parkinson's disease and a generic oxidative stress. Although the number of disease models thus far studied is by no means exhaustive, it represents major groups of NCDs, supporting the proposed mechanism.

This proposed mechanism posits that various extracellular stressors converge on the co-activation of the TRPM2 channel and NOX2 enzyme at the plasma membrane. This initial co-activation establishes a positive feedback loop at the plasma membrane itself: NOX2 generates ROS contributing to TRPM2 activation, while the resulting TRPM2-mediated Ca²⁺ influx provides the necessary Ca²⁺ signal to sustain NOX2 activity. This synergy amplifies the cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ signals. The rise in cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ primarily targets lysosomes, causing de-acidification, dysfunction, and potentially LMP or rupture. This lysosomal damage releases sequestered contents, most critically, labile Zn²⁺, into other parts of the cell, especially to the mitochondria. Within mitochondria, elevated Zn²⁺ directly impairs the ETC, enhancing electron leakage predominantly from Complex III, thereby increasing mtROS (O₂•⁻) production. This burst of mtROS diffuses into the cytoplasm, activates PARP-1 in the nucleus, generating ADPR, which activates plasma membrane TRPM2 channels, closing the loop and restarting the ROS amplification cycle. This vicious cycle is presumably repeated multiple times before the cell dies in degenerative diseases.

This mechanism integrates signalling molecules (TRPM2, NOX2, Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, ADPR, ROS itself) and organelles (plasma membrane, lysosomes, mitochondria and nucleus) implicated in RIRP into a coherent pathway. It proposes a "circular domino effect" (

Figure 4) where an initial stressor triggers a cascade of cytotoxic Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, ROS and ADPR signals relayed between the plasma membrane, lysosomes, mitochondria and the nucleus. During this relay, progressive damage of lysosomes, mitochondria and nuclei occurs, leading to cell dysfunction and or demise. This cycle provides a plausible mechanistic explanation for ROS amplification and organelle impairment, the hallmarks of most NCDs [

121]. The subsequent sections dissect the key steps of this putative cycle in more detail, as this aspect has not been previously reviewed.

Detailed schematic illustrating the proposed inter-organelle signalling cycle.

(1) Extracellular stress activates plasma membrane TRPM2 and NOX2.

(2) Synergistic interplay between TRPM2 and NOX2 increases cytoplasmic [Ca²⁺].

(3) Elevated [Ca²⁺] causes lysosomal dysfunction and damage (LMP).

(4) Dysfunctional lysosomal Zn²⁺ is translocated to mitochondria.

(5) Increased mitochondrial Zn²⁺ causes mitochondrial damage by inhibiting Complex III, raising mtROS, increasing fragmentation, and reducing ΔΨmt.

(6) mtROS diffuses into the cytoplasm to cause double strand DNA breaks and induce PARP-1 activation. PARP-1, together with PARG ((Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase), generates ADPR and provides positive feedback to TRPM2, perpetuating the cycle.

The cycle involves five key molecular players (TRPM2, Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, ROS, ADPR) and communication between four compartments (plasma membrane, lysosomes, mitochondria and the nucleus).

Initiating the Cycle: Synergistic Activation of TRPM2 and NOX2 at the Plasma Membrane

The cycle begins at the plasma membrane. External stress signals are initially sensed and transduced at the plasma membrane via TRPM2 and NOX2 co-activation. Studies with cellular models of Parkinson's disease and generic oxidative stress revealed a striking reciprocal dependence between these proteins under stress. NOX2 activation is dependent on TRPM2-mediated Ca²⁺ entry, and conversely, sustained TRPM2 activity (measured by Ca²⁺ influx) required NOX2-generated ROS [

76]. Pharmacological inhibition or siRNA knockdown of either TRPM2 or NOX2 abrogated the stress-induced rise in intracellular Ca²⁺ and prevented subsequent ROS amplification and downstream cytotoxicity (lysosomal/mitochondrial damage, cell death) [

76]. This suggests that TRPM2-NOX2 interplay establishes a crucial positive feedback loop at the plasma membrane, acting as a highly sensitive trigger that exacerbates Ca²⁺ influx in response to oxidative insults.

However, the precise molecular mechanism of their cooperation and activation sequence remains unclear. Plausible scenarios include: (i) initial stress causes basal TRPM2 activation (via other ROS or direct sensing), generating the initial Ca²⁺ for NOX2 assembly/activation; or (ii) initial stress primarily activates NOX2, whose ROS products then trigger robust TRPM2 opening. Further research is needed to address these possibilities.

Two key observations are noteworthy. First, the apparent channel specificity: despite other ROS-sensitive plasma membrane Ca²⁺ transport mechanisms (other TRPs, SOCE) [

87,

88,

122], TRPM2 downregulation alone abolished the stress-induced cytotoxic cascade in studied models. Second, selectivity for pathogenic ROS levels: inhibiting the TRPM2-NOX2 axis prevented stress-induced ROS amplification but did not appear to affect basal physiological ROS [

76]. This specificity, conferred by the Zn

2+-dependent inhibition of complex III, is therapeutically significant, potentially overcoming the limitation of general antioxidants – their inability to discriminate between beneficial and detrimental ROS [

25,

26]. Targeting the TRPM2-NOX2 duo (or their interaction) could offer a safer strategy. Elucidating the molecular basis of TRPM2-NOX2 coupling mechanism should be a key goal for future research.

Calcium Overload Targets Lysosomes

It is well accepted that rise in cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ to supraphysiological levels impacts mitochondria to affect its structure and function, leading to abnormal mitochondrial fragmentation, bioenergetic failure and ROS production [

33,

39,

100,

101,

116]. Recent findings suggest that not all mitochondrial effects of Ca²⁺ are direct. During stress, Ca²⁺ signals mitochondrial damage via lysosomes. In stress models thus far examined, the Ca²⁺ rise consistently caused lysosomal dysfunction (proton gradient dissipation/de-acidification) and physical damage/permeabilization, leading to secondary effects on mitochondria [

76,

100].

The precise molecular mechanisms by which elevated cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ leads to lysosomal de-acidification, dysfunction, and damage remain to be fully elucidated. Possibilities include effects on the V-ATPase pump, altered lysosomal membrane lipid composition/stability, or activation of Ca²⁺-dependent enzymes compromising integrity. Nevertheless, identifying a specific upstream pathway (stress → TRPM2/NOX2 → Ca²⁺ overload → lysosomal damage) is a fundamental step in unravelling the mechanistic basis for the lysosomal dysfunction and damage widely observed in chronic stress and associated diseases.

From Damaged Lysosomes to Mitochondria: The Journey of Zinc

Lysosomes store a number of factors (e.g., enzymes, metal ions) required for their function, but if unleashed, they can have damaging effects, resulting in cell dysfunction and even cell death [

31,

32,

40,

41,

46,

50,

53,

54,

80,

83]. Among the factors that can contribute to abnormal downstream signalling are Ca²⁺ and Zn²⁺. Cells possess robust mechanisms for handling excess cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ (ER sequestration via the Sarcoendoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase pump, mitochondrial uptake via mitochondrial uniporter, plasma membrane efflux via plasma membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase/sodium-calcium exchanger), to restoring basal levels quickly after transient increases to prevent Ca²⁺-induced damage [

87,

88,

123].

However, compared to Ca²⁺ homeostasis, how cells handle sudden release of labile cytoplasmic Zn²⁺ is less understood. While the cytoplasm contains significant amounts of high-affinity Zn²⁺-binding metallothioneins (primary buffer), studies found mitochondria nonetheless accumulated significant Zn²⁺ following the Ca²⁺-dependent lysosomal damage [

76,

100,

101]. This mitochondrial Zn²⁺ accumulation was observed consistently across different models of cellular stress representing different disease conditions. The precise mechanism by which released Zn²⁺ bypasses/overwhelms cytoplasmic buffering and selectively translocates into mitochondria remains to be determined.

Genetic evidence from studies of mutations associated with Parkinson's disease underpins the pathogenic importance of mitochondrial translocation of lysosomal Zn²⁺ [

51,

124]. Notably, studies of

PARK9 mutations demonstrated redistribution of lysosomal Zn²⁺ to mitochondria. The mutation impairs the function of the

PARK9-encoded ATP13A2 (a lysosomal Zn²⁺ importer), resulting in mitochondrial Zn²⁺ accumulation, subsequent mitochondrial fragmentation, dysfunction and ROS production. These findings underscore the importance of Zn²⁺ accumulation in mitochondrial damage. As with the genetic condition, the source of mitochondria-damaging Zn²⁺ during chronic stress is lysosomes, and the stimulus for this is extracellular Ca²⁺ entry [

76,

100,

101]. Thus, redistribution of lysosomal Zn²⁺ to mitochondria may be an important step in pathogenic mechanisms associated with chronic stress.

Zinc Disrupts Mitochondrial Function and Bolsters ROS Production

As demonstrated with

PARK9 mutations, the Ca²⁺-driven mobilisation of lysosomal Zn²⁺ to mitochondria led to the loss of ΔΨmt, increased ROS production, and mitochondrial fragmentation [

76,

100,

101]. Notably, chelation of Zn²⁺ with TPEN (N,N,N',N'-Tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine) mitigated the mitochondrial events triggered by the Ca²⁺-induced lysosomal damage [

76,

100,

101]. These findings led to the conclusion that the detrimental effects of Ca²⁺ on mitochondria are not direct, but mediated by Zn²⁺, positioning Zn²⁺ downstream of Ca²⁺.

These findings might warrant a review of the long-accepted mechanism for how Ca²⁺ causes mitochondrial damage, by alluding to the fact that the effect of Ca²⁺ on mitochondria is mediated by Zn²⁺ during chronic stress. Previous studies might have missed this due to the reliance on BAPTA (1,2-Bis(2-Aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetra acetic acid) to probe Ca²⁺-driven events, as BAPTA binds Zn²⁺ with much greater affinity (≥10-fold) than Ca²⁺ [

103,

110].

While Ca²⁺ can stimulate ROS generation from multiple mitochondrial sites, elevated mitochondrial matrix Zn²⁺ can directly stimulate electron leak from Complexes I and III, increasing ROS production [

125,

126]. Using compounds capable of quenching electron leak from Complex I (S1QEL) and Complex III (S3QEL), recent studies demonstrated S3QEL is far more effective than S1QEL in suppressing ROS production in neuroblastoma cells subjected to treatments that raised mitochondrial Zn²⁺ [

76]. The stronger S3QEL effect seems consistent with Complex III having a high-affinity (K

i ~0.1 µM) [

125,

126] Zn²⁺ binding site near the Qo electron transfer site [

77]. The weaker S1QEL effect aligns with reports that Complex I lacks a Zn²⁺ binding site in its catalytic core and has relatively low affinity (IC

50 ~10-50 µM) [

125,

126]. In addition, basal mitochondrial Zn²⁺ is extremely low (picomolar) [

127], so any rise would arguably inhibit Complex III before affecting Complex I.

Compelling evidence for Complex III's unique pathogenic role comes from

in vivo knockout mice studies. Genetic deletion of functionally important subunits in neurons revealed Complex III, but not other complexes, contributes to ROS damage, neuronal cell death, and motor deficits [

73,

75]. More recently, the group demonstrated altered redox status, early β-cell dysfunction, and hyperglycaemia in Complex III-depleted mice [

74]. Furthermore, a recent genome-wide study linked mutations in mitochondrial UQCRC1 (a core Complex III component) to Parkinson's disease[

72]. Knock-in of these mutations in Drosophila and mouse models showed age-dependent locomotor deficits and dopaminergic neuronal death [

72]. In neuroblastoma cells, these mutations affected mitochondrial function, increasing ROS [

72]. Determining if Complex III plays a similar role in other pathologies, alongside the role of lysosomal Zn²⁺ redistribution to mitochondria, is important.

Closing the Loop: Mitochondrial ROS Stimulates ADPR Production to Perpetuate the Cycle

The final crucial step is feedback from damaged mitochondria back to the plasma membrane to sustain initial TRPM2-NOX2 activation. Increased mtROS (from mitochondrial Zn²⁺ accumulation and Complex III inhibition) can diffuse out and reach the cytoplasm, further stimulating TRPM2 channel activity by generating the TRPM2 agonist ADPR. Although ADPR can be generated both in the mitochondria and nucleus, in chronic stress, much of it is generated in the nucleus through PARP-1 activation due to increased nuclear DNA damage [

128]. This renewed TRPM2 activation ensures continued Ca²⁺ influx, sustaining NOX2 activity and promoting lysosomal damage, thus closing the positive feedback loop. Scavenging the mtROS with mito-TEMPO abolishes TRPM2-mediated cell death, as effectively as S3QEL and PJ34 [

76], supporting the feedback effect of mtROS on TRPM2.

Thus, in addition to the feedback loop between TRPM2 and NOX2 at the plasma membrane, there is a second feedback activation loop from mtROS on the TRPM2 channel, involving ADPR generation in the nucleus from PARP-1 activation. This indicates that the communication between mitochondria and the plasma membrane occurs through the nucleus. The cycle entails sustained generation of distinct signals (at each organelle) that enable signal transmission from the plasma membrane through lysosomes (Ca²⁺), mitochondria (Zn²⁺), nucleus (mtROS) and back to the plasma membrane (ADPR). The built-in feedback loops enable amplification of signals at different nodes within the cycle, leading to progressive damage of lysosomes, mitochondria and nuclei, and eventually to cell dysfunction and demise.

The Impact of Activating the Signalling Cycle

The pathogenic effect of activating this signalling cycle depends on the cell type and its physiological role. Effects can range from ageing to chronic conditions including diabetes and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Few studies have systematically investigated interrupting the cycle at various points —inhibiting TRPM2 or NOX2, chelating Ca²⁺ or Zn²⁺, preventing Complex III electron escape, scavenging mtROS, or inhibiting PARP-1— on organelle damage and pathophysiological consequences (e.g., programmed cell death) across different disease models to determine the pathway's broad significance [

76,

101]. Programmed cell death (apoptosis or parthanatos) results from the release of cytochrome

C and AIF (apoptosis-inducing factor) from the damaged mitochondria, and cathepsins from damaged lysosomes.

For example, studies on pancreatic β-cells (diabetes model) and neuronal cells (Parkinson's disease model) concurrently examined roles for NOX2, TRPM2, Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Complex III (in PD model only) in lysosomal/mitochondrial damage and ROS amplification, demonstrating the circuit's role in cell death [

76,

101]. In human endothelial cells, diabetic stress led to TRPM2-mediated Ca²⁺ influx, lysosomal impairment, Zn²⁺ translocation to mitochondria, Drp1-dependent mitochondrial damage, and ROS production [

100]. Other studies link excess mitochondrial fragmentation in this model to reduced nitric oxide generation, relevant to hypertension regulation [

38].

Thus, akin to a "circular domino effect," the signalling circuit involves sequential, reciprocal lysosomal, mitochondrial and nuclear damage, initiated by plasma membrane Ca²⁺ signals (TRPM2-NOX2 co-activation) and propagated by Zn²⁺ (lysosome-generated), ROS (mitochondria-generated) and ADPR (nucleus-generated) signals culminating in pathogenic responses (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The cycle provides a mechanistic explanation for how oxidative stress becomes amplified and self-sustaining, leading to progressive organelle damage and pathological outcomes in chronic disease settings.

Evidence Supporting the Unified Mechanism Across Disease Models

Support for this unified mechanism comes from studies using diverse cellular and

in vivo models relevant to human OS-associated diseases. For instance, exposing human endothelial cells to high glucose (diabetic stress mimic) induced lysosomal damage, mitochondrial fragmentation/dysfunction, and excessive ROS – linked phenotypically to reduced nitric oxide bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction [

38,

100]. Crucially, these phenotypic effects were attenuated/prevented by pharmacological inhibitors of TRPM2, genetic suppression of TRPM2 (siRNA), PARP-1 inhibition with PJ34, chelation of intracellular Ca²⁺ (BAPTA-AM), chelation of intracellular Zn²⁺ (TPEN) and sequestration of ROS.

Similarly, exposing rodent and human pancreatic β-cells to excess free fatty acids (metabolic stress mimic) led to a comparable cascade: mitochondrial fragmentation/dysfunction, ROS overproduction, and β-cell apoptosisβ [

101]. These outcomes were rescued by RNAi-mediated knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of TRPM2, PARP inhibition, and by Ca²⁺/Zn²⁺ chelators and ROS quenchers. In both models, evidence indicated Ca²⁺ overload caused initial lysosomal damage, while subsequent mitochondrial damage depended on the downstream increase in mitochondrial Zn²⁺. Furthermore, NOX2 inhibition abolished free fatty acid-induced ROS overproduction in β-cells, implicating NOX2 in initiation of the cycle at the plasma membrane. Supporting

in vivo relevance, rodent models of high-fat diet-induced obesity/diabetes showed that genetic knockout of

Trpm2 prevented hyperglycaemia, preserved mitochondrial function, and attenuated weight gain [

129].

More recently, a similar mechanism was confirmed in a cellular model of Parkinson's disease. Treating neuroblastoma cells with MPP⁺ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium, MPP⁺) co-stimulated TRPM2 and NOX2, leading to increased intracellular Ca²⁺. This Ca²⁺ rise triggered lysosomal damage, followed by Zn²⁺-dependent mitochondrial damage (fragmentation, dysfunction), ROS amplification, and cell death. In addition, PARP-1 inhibition mitigated the phenotypic effects of the toxin [

76].

Remarkably, the core phenotypic changes across these diverse stress models (high glucose, fatty acids, MPP⁺) could be largely recapitulated in a simpler, recombinant HEK-293 cell system conditionally expressing TRPM2 using the generic oxidant H₂O₂ as the stressor, suggesting a conserved fundamental pathway. A notable feature of this proposed destructive cascade is its self-perpetuating nature: organelles generate signals that cause their own damage.

Although the number of disease models studied to arrive at the signalling circuit are somewhat limited, there are numerous reports in the literature supporting the individual steps within the cycle in a diverse range of

in vitro and

in vivo disease models. An examination of these studies implicating two or more of the signalling molecules (TRPM2, NOX2, PARP1, Zn²⁺ and mitochondrial ROS (summarised in

Table 1) lends circumstantial support to the unified signalling circuit.

Activation and/ or upregulation of TRPM2, NOX2, and PARP-1 have been linked to many cancers [

102,

130,

131,

132]. While a detailed discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this review, key findings are summarized in

Table 1. TRPM2 activation promotes cell proliferation and preserves cell viability by activating transcription factors and signalling pathways [

102]. The role of Zn

2+, however, is less clear, but TRPM2-mediated lysosomal Zn

2+ release promotes mitochondrial fission, which is required for inheritance and partitioning of mitochondria during cell division [

104,

133,

134]. It is therefore reasonable to assume that Zn

2+ plays a role in cell proliferation. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission has been shown to prevent cell cycle progression in cancer [

135]. In addition to promoting cell proliferation, TRPM2 activation facilitates Zn²⁺-dependent remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions, enhancing cell migration [

103]. Furthermore, studies have shown activation of PARP-1 and NOX2 promotes migration of several cancer cell types [

136,

137]. However, it should be noted that the ROS-dependent signalling mechanisms are highly complex and vary significantly depending on the cancer type.

Although comprehensive, systematic studies linking all the events of the cycle to individual NCDs and cell types are required, the comparison of existing reports (

Table 1) lends circumstantial support to the idea that this signalling axis is likely conserved among many OS-linked diseases.

However, significant further research is required. Key areas include: elucidating precise TRPM2-NOX2 coupling mechanisms; understanding how Ca²⁺ damages lysosomes; identifying pathways for lysosomal Zn²⁺ release and mitochondrial Zn²⁺ uptake under stress; confirming Complex III's primary role as the Zn²⁺-sensitive mtROS source; and validating the cycle's operation and therapeutic tractability in more complex in vivo models and human pathophysiology. Addressing these questions is crucial for translating these exciting mechanistic insights into effective clinical therapies for combating OS-associated diseases.

Table 1.

Major diseases where TRPM2, NOX2, Zn2+, mitochondrial ROS and PARP are involved.

Table 1.

Major diseases where TRPM2, NOX2, Zn2+, mitochondrial ROS and PARP are involved.

| Specific Disease |

TRPM2 Involvement |

NOX2 Involvement |

Zn2+ Involvement |

Mitochondrial ROS Involvement |

PARP Involvement |

Comments |

Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

|

TRPM2 inhibition (2-APB or ACA): ↓Aβ42-induced neuronal death in mouse hippocampus [142].

TRPM2 KO:

↓Aβ-induced neurotoxicity

↓Ca²⁺ influx

↓ TNF-α release [142].

TRPM2 KO (APP/PS1 mice): Improved spatial memory,

↓Microglial activation in hippocampus [143]. |

NOX2-KO in mice: improved spatial memory [144].

Postmortem analyses:

↑NOX2 activity and expression in frontal and temporal cortices in patients with mild cognitive impairment [145].

|

Clioquinol (Zinc chelators): Potential in reducing plaque load in AD models [146].

ZnT3-deficient mice:

↓ Aβ oligomer accumulation [146].

|

Scavenging mito-ROS with mitochondria targeted ROS scavengers in 3xTg-AD mice:

↓ OS

↓ Aβ oligomer accumulation

↓Cell death

↓Cognitive impairment

[147]. |

PARP inhibition (pharmacological and genetic):

↓neuronal loss through parthanatos, neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment [141]. |

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) |

TRPM2 inhibition (2-APB, PJ34) and knockdown in cellular model:

↓MPP⁺- induced mtROS production and cell death [76] [148].

Post-mortem brains of PD patients:

↑TRPM2 protein levels in SNpc [148].

|

NOX2 inhibition (pharmacological) in cellular model: ↓MPP⁺-induced Ca²⁺ rise

↓mtROS production

↓Cell death [76].

NOX2 inhibition (apocynin) in paraquat and 6-OHDA administered mice:

↓Cognitive deficits ↓Oxidative stress ↓Neuroinflammation [149] [150].

NOX2 KO in 6-OHDA administered mice: ↓Dopaminergic neuron loss [150].

Post-mortem brains of PD patients:

↑gp91phox expression in midbrain [151]. |

Chelation of intracellular Zn²⁺ (TPEN):

↓ROS levels

↓ MPP⁺-induced cytotoxicity [76].

Post-mortem brains of PD patients:

↑Zn2+ levels observed in SNpc [152].

Genetic mutations in PARK9:

↑Mitochondrial Zn2+ in dopaminergic neurons ↑Mitochondrial damage [51,124]. |

Scavenging mito-ROS with mitochondria targeted ROS scavengers:

↓MPP⁺-induced cell death [76].

MitoQ in preclinical models:

Neuroprotective [153].

|

PARP-1 chemical inhibition or gene deletion:

↓α-synuclein-induced toxicity and neuronal death

Post-mortem PD patient brains and CSF:

↑PAR levels [154].

|

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but need in vivo evidence |

| Cardiac ischemia |

TRPM2 KO mice or inhibition (chemical) subjected to IR injury:

↓Infarct size ↓Inflammation

↑Cardiac outcome [155]. |

NOX2 KO mice subjected to IR injury:

↑ROS

↓Infarct size

[156]. |

Zn2+ chelation (TPEN):

↓Infarct area in rat hearts during I/R injury [157]. |

Scavenging mito-ROS with MitoQ in rats subjected to IR injury:

↓Heart dysfunction ↓Mitochondrial damage

↓Cell death [158].

|

PARP1 inhibition (chemical) in

mice subjected to IR injury:

↓Infarct size

↓Inflammation

↑Cardiac function [159]. |

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

| Stroke/Cerebral Ischemia |

TRPM2 KO or inhibition (chemical) in male mice subjected to IR injury:

↓Neuronal cell death

↓Infarct size ↓Memory loss [160,161]. |

NOX2 KO mice subjected to IR injury:

Delay infarct progression, but

no protect from brain injury [162]. |

Zn2+ chelation (TPEN):

Protects mice from ischaemic brain damage [106]. |

Mitochondrial ROS in IR injury mouse model:

↑ Mitochondrial ROS in hippocampus in mice.

MitoQ:

↓Hippocampal damage [163]. |

PARP1 gene inactivation:

Protection against ischemic insults [164]. |

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

| Various Cancers |

TRPM2 Inhibition (chemical/genetic- SiRNA/KO):

Breast cancer cells

↓ Proliferation

↑ DNA damage [165].

Neuroblastoma cells

↓ Viability

↑ ROS

↑DNA damage

(sensitised to doxorubicin) [166].

Leukaemia

↓ Proliferation

↑ Chemo sensitivity [167].

Ovarian Cancer

↓ Cell viability ↓Proliferation

↑ Apoptosis [168].

PC3 and HeLa cells

↓Cell migration [103]. |

NOX2 inhibition:

Leukaemia cells

↑ Cell death [169].

NOX2-KO and inhibition in mice:

↓ Lung metastases [170].

|

Zn2+ depletion:

Breast cancer cells

ZIP10 KO or zinc depletion:

↓Cell migration [171].

PC3 and HeLa

Zn2+ chelation (TPEN):

↓Cell migration [103]. |

Scavenging mito-ROS in mice:

Mice lung carcinoma cells

↓ Metastasis [172].

Mouse melanoma cells

↓ Cell growth

↓ viability

↑ Apoptosis [173]. |

↑ PARP1 expression in breast, ovarian, and lung cancers. [131].

PARP1 inhibition:

Cervical cancer cell lines:

↓ Proliferation

↑ Cell death

↓ Metastasis [174].

Liver cancer cells:

↓ Proliferation

↓Cell migration [175].

PARP inhibition (PJ34)

↓Cell migration [103]. |

There is significant evidence for all listed players in cancer, but integrating studies into a generalized model can be challenging. |

Atherosclerosis (AS)

|

TRPM2 KO in Apoe-/- mice: ↓Progression of AS [176].

TRPM2 KO and KD:

↓Mitochondrial damage in EC [100]. |

NOX2 KO in Apoe/-e mice:

↓Plaque formation due to absence of NOX2 in macrophages and vessel wall cells [177]. |

Zn2+ role in AS unclear, but excess mitochondrial Zn2+ causes its fragmentation in EC [100]. |

NOX2 KO in Apoe/-e mice:

↓Superoxide levels.

MitoQ treatment:

↓Plaques [178]. |

PARP1 inhibition or KO Apoe/-e mice: ↓Plaque formation ↓Progression of atherosclerosis [179]. |

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

| Type 2 Diabetes |

TRPM2 KO:

↑Insulin Sensitivity

↑Resistance to Diet-Induced Obesity

↑Glucose Metabolism ↓Obesity-Mediated Inflammation [129].

Pancreatic β-cells (FFA treated): ↑NOX-dependent ROS

↑ Mitochondrial damage

↑Cell death [101]. |

NOX2 KO:

↑Insulin Sensitivity ↑Resistance to Diet-Induced Obesity [180].

Pancreatic β-cells/islets exposed to FFA:

↑Insulin secretion

↓ROS [101].

|

Zn2+ chelation (TPEN):

↓FFA -induced β-cell death [101].

Overexpression of hZnT8: ↑Pancreatic Zn2+ ↓insulin and glucose tolerance [181].

|

Excess nutrition: ↑mtROS production ↑Insulin resistance ↑β-cell dysfunction [182].

|

PARP-1 KO:

↓β-cell dysfunction, ↓Insulin resistance,

↓ Vascular damage [183].

Pancreatic β-cells: ↓Death by PARP-1 inhibitor (PJ34) [101]. |

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

| Type 1 diabetes |

TRPM2 KO in mice (STZ model):

↓ β-cell death ↓Hyperglycaemia [184].

|

NOX2 KO:

↓Glucose-induced Superoxide in islets

↑Glucose-induced insulin secretion

↓β-cell apoptosis [185].

|

Zn2+ chelation in STZ mouse model:

↓ β-cell death ↓Hyperglycaemia [184] [186].

|

Mitochondrial ROS:

↑ β-cell damage [20].

|

PARP-1 KO in STZ mouse model:

↓ β-cell death ↓Hyperglycaemia [187].

|

Significant evidence from individual studies for all listed players, but needs to be integrated into a single model system |

Therapeutic Opportunities and Future Directions

While cyclical signalling mechanisms are crucial for fundamental rhythmic and cell division processes [

138,

139], they represent a smaller subset of the overall signalling landscape in biology. Linear signalling cascades, with their inherent flexibility and capacity for diverse responses, constitute the vast majority of the intricate communication networks within and between cells. These linear pathways can sometimes incorporate feedback loops that introduce oscillatory behaviour in downstream targets, but the core signal transduction mechanism is typically a linear progression of molecular events.

Unlike common linear signalling pathways, the pathway described here (

Figure 4) seems to operate in cyclical fashion, akin to metabolic cycles. A key advantage of such a cycle over linear pathways is that it offers a rich landscape for therapeutic intervention. One could intervene at any one of the available nodes and the entire cycle stops. Indeed, as explained above, inhibiting any of the molecular players—TRPM2, NOX2, mitochondrial complex III, or PARP-1—or scavenging the signals they generate (Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺ and mtROS), mitigates lysosomal, mitochondrial and nuclear damage, and cell demise -the hallmarks of most NCDs. The chemicals used to interrupt the cycle, however, are not suitable for safe therapeutic use, but provide the proof-of-principle that many of the nodes in the cycle are potential drug targets.

Any therapeutic developed based on this cycle is unlikely to exhibit significant adverse effects because it would selectively interrupt pathological ROS production, sparing essential signalling ROS production (unlike general antioxidants). Targeting TRPM2 directly holds promise. Similarly, developing highly selective NOX2 inhibitors could break the cycle at initiation, though isoform selectivity remains challenging. Preventing lysosomal damage or stabilizing membranes could stop toxic Zn²⁺ release. Alternatively, specific intracellular Zn²⁺ chelators accessing relevant compartments, or strategies preventing mitochondrial Zn²⁺ uptake, could protect mitochondria. Finally, targeting mtROS production itself, specifically reducing Complex III electron leak, could prevent feedback amplification. PARP-1 inhibitors are used clinically for cancer treatment [

130,

131,

140] and are being currently targeted for therapeutic treatment of NCDs [

141].

A simplified representation of the cytotoxic inter-organelle signalling circuit initiated by stress.

Step 1: Plasma membrane sensing: External stress (over-nutrition, pollutants, toxins, and ageing) act as external stress, influencing the plasma membrane. This leads to the TRPM2/NOX2 complex at the plasma membrane generating Ca²⁺ signals.

Step 2: Lysosomal dysfunction and Zn²⁺ release: The generated Ca²⁺ signals cause lysosomal dysfunction and damage (LMP), resulting in the release of Zn²⁺.

Step 3: Mitochondrial targeting and mtROS production: The released Zn²⁺ targets mitochondria, specifically Complex III, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS).

Step 4: Generation of TRPM2 agonist in the nucleus. The produced mtROS activates PARP-1 in the nucleus, generating ADPR signals.

Step 5: Amplification and perpetuation: ADPR signals from the nucleus, together with Ca²⁺, stimulate further TRPM2-mediated Ca²⁺ influx at the plasma membrane, amplifying the signal and perpetuating organelle damage, eventually leading to cell dysfunction and death.

The unique feature of this signalling cascade is its cyclical nature, which presents multiple therapeutic targets: interrupting any node can theoretically mitigate multiple organelle damage, linked to NCDs and a decline in the healthspan-to-lifespan ratio as we age.

The potential utility of targeting this cycle is underscored by its apparent involvement across multiple disease models (diabetes complications, neurodegeneration, potentially others involving chronic oxidative stress). This suggests interventions aimed at this core TRPM2-Ca²⁺-Lysosome-Zn²⁺-Mitochondria-ROS axis could represent broad-spectrum therapeutics for the underlying OS common to numerous NCDs. By preventing the vicious cycle, such therapies might treat specific diseases and potentially slow aspects of aging, enhancing the healthspan-to-lifespan ratio.

Acknowledgements

We thank for PhD scholarships to MA and ES: Kuwait University, Kuwait (MA), The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, and The State of Libya (ES)

Author Contributions

MA and ES searched the literature and complied the Table; ES generated figures. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Nunnari, J. and Suomalainen, A. (2012) Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 148, 1145-1159.

- Sena, L. A. and Chandel, N. S. (2012) Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 48, 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. F., Chiao, Y. A., Marcinek, D. J., Szeto, H. H. and Rabinovitch, P. S. (2014) Mitochondrial oxidative stress in aging and healthspan. Longev Healthspan. 3, 6. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H., Berndt, C. and Jones, D. P. (2017) Oxidative Stress. Annu Rev Biochem. 86, 715-748.

- Murphy, M. P. and Hartley, R. C. (2018) Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for common pathologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 17, 865-886.

- Parvez, S., Long, M. J. C., Poganik, J. R. and Aye, Y. (2018) Redox Signaling by Reactive Electrophiles and Oxidants. Chem Rev. 118, 8798-8888.

- Brand, M. D. (2020) Riding the tiger - physiological and pathological effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generated in the mitochondrial matrix. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 55, 592-661. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. and Jones, D. P. (2020) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21, 363-383. [CrossRef]

- Forman, H. J. and Zhang, H. (2021) Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 20, 689-709. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H., Belousov, V. V., Chandel, N. S., Davies, M. J., Jones, D. P., Mann, G. E., Murphy, M. P., Yamamoto, M. and Winterbourn, C. (2022) Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23, 499-515. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H., Mailloux, R. J. and Jakob, U. (2024) Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25, 701-719. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Li, Y., Li, Y., Ren, X., Zhang, X., Hu, D., Gao, Y., Xing, Y. and Shang, H. (2017) Oxidative Stress-Mediated Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapies. Front Physiol. 8, 600. [CrossRef]

- Touyz, R. M., Rios, F. J., Alves-Lopes, R., Neves, K. B., Camargo, L. L. and Montezano, A. C. (2020) Oxidative Stress: A Unifying Paradigm in Hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 36, 659-670. [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E. T., Pell, V. R., James, A. M., Work, L. M., Saeb-Parsy, K., Frezza, C., Krieg, T. and Murphy, M. P. (2016) A Unifying Mechanism for Mitochondrial Superoxide Production during Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab. 23, 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Dias, V., Junn, E. and Mouradian, M. M. (2013) The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 3, 461-491.

- Panicker, N., Ge, P., Dawson, V. L. and Dawson, T. M. (2021) The cell biology of Parkinson's disease. J Cell Biol. 220.

- Vázquez-Vélez, G. E. and Zoghbi, H. Y. (2021) Parkinson's Disease Genetics and Pathophysiology. Annu Rev Neurosci. 44, 87-108.

- Butterfield, D. A. and Halliwell, B. (2019) Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 20, 148-160. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. L., Goldfine, I. D., Maddux, B. A. and Grodsky, G. M. (2002) Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 23, 599-622. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Stimpson, S. E., Fernandez-Bueno, G. A. and Mathews, C. E. (2018) Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Type 1 Diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 29, 1361-1372. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N., Youle, R. J. and Finkel, T. (2016) The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging. Mol Cell. 61, 654-666.

- Guo, J., Huang, X., Dou, L., Yan, M., Shen, T., Tang, W. and Li, J. (2022) Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7, 391. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. D., Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. and Tew, K. D. (2020) Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 38, 167-197.

- Liu, S. Z., Chiao, Y. A., Rabinovitch, P. S. and Marcinek, D. J. (2024) Mitochondrial Targeted Interventions for Aging. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 14. [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M. (2014) Unraveling the truth about antioxidants: mitohormesis explains ROS-induced health benefits. Nat Med. 20, 709-711. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. (2024) Understanding mechanisms of antioxidant action in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25, 13-33. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. and Singh, A. (2015) A review on mitochondrial restorative mechanism of antioxidants in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological conditions. Front Pharmacol. 6, 206. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J., Lv, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Qiao, X., Sun, C., Chen, Y., Guo, M., Han, W., Ye, A., Xie, T., Chu, B., Shi, C., Yang, S. and Chen, C. (2021) Precision Redox: The Key for Antioxidant Pharmacology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 34, 1069-1082. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J., Lv, Z., Wang, Y. and Chen, C. (2022) Identification of the redox-stress signaling threshold (RST): Increased RST helps to delay aging in C. elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 178, 54-58. [CrossRef]

- Archer, S. L. (2013) Mitochondrial dynamics--mitochondrial fission and fusion in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 369, 2236-2251.

- Bourdenx, M. and Dehay, B. (2016) What lysosomes actually tell us about Parkinson's disease? Ageing Res Rev. 32, 140-149.

- Carmona-Gutierrez, D., Hughes, A. L., Madeo, F. and Ruckenstuhl, C. (2016) The crucial impact of lysosomes in aging and longevity. Ageing Res Rev. 32, 2-12. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. R. and Nunnari, J. (2014) Mitochondrial form and function. Nature. 505, 335-343.

- Jheng, H. F., Tsai, P. J., Guo, S. M., Kuo, L. H., Chang, C. S., Su, I. J., Chang, C. R. and Tsai, Y. S. (2012) Mitochondrial fission contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol. 32, 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R., Barnes, K., Hastings, C. and Mortiboys, H. (2018) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease: can mitochondria be targeted therapeutically? Biochem Soc Trans. 46, 891-909.

- Mao, K. and Zhang, G. (2022) The role of PARP1 in neurodegenerative diseases and aging. FEBS J. 289, 2013-2024. [CrossRef]

- Perera, R. M. and Zoncu, R. (2016) The Lysosome as a Regulatory Hub. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 32, 223-253. [CrossRef]

- Shenouda, S. M., Widlansky, M. E., Chen, K., Xu, G., Holbrook, M., Tabit, C. E., Hamburg, N. M., Frame, A. A., Caiano, T. L., Kluge, M. A., Duess, M. A., Levit, A., Kim, B., Hartman, M. L., Joseph, L., Shirihai, O. S. and Vita, J. A. (2011) Altered mitochondrial dynamics contributes to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 124, 444-453. [CrossRef]

- Tabara, L. C., Segawa, M. and Prudent, J. (2025) Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 26, 123-146.

- Udayar, V., Chen, Y., Sidransky, E. and Jagasia, R. (2022) Lysosomal dysfunction in neurodegeneration: emerging concepts and methods. Trends Neurosci. 45, 184-199. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. X. and Finkel, T. (2023) Lysosomes in senescence and aging. EMBO Rep. 24, e57265.

- Qian, L., Zhu, Y., Deng, C., Liang, Z., Chen, J., Chen, Y., Wang, X., Liu, Y., Tian, Y. and Yang, Y. (2024) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9, 50. [CrossRef]

- Luzio, J. P., Pryor, P. R. and Bright, N. A. (2007) Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 8, 622-632.

- Saffi, G. T. and Botelho, R. J. (2019) Lysosome Fission: Planning for an Exit. Trends Cell Biol. 29, 635-646. [CrossRef]

- Levine, B. and Kroemer, G. (2019) Biological Functions of Autophagy Genes: A Disease Perspective. Cell. 176, 11-42. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. and Kravic, B. (2024) The Endo-Lysosomal Damage Response. Annu Rev Biochem. 93, 367-387. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, L., Lotfi, P., Pal, R., Ronza, A. D., Sharma, J. and Sardiello, M. (2019) Lysosome biogenesis in health and disease. J Neurochem. 148, 573-589. [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C., Di Malta, C., Polito, V. A., Garcia Arencibia, M., Vetrini, F., Erdin, S., Erdin, S. U., Huynh, T., Medina, D., Colella, P., Sardiello, M., Rubinsztein, D. C. and Ballabio, A. (2011) TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 332, 1429-1433. [CrossRef]

- Todkar, K., Ilamathi, H. S. and Germain, M. (2017) Mitochondria and Lysosomes: Discovering Bonds. Front Cell Dev Biol. 5, 106. [CrossRef]

- Mutvei, A. P., Nagiec, M. J. and Blenis, J. (2023) Balancing lysosome abundance in health and disease. Nat Cell Biol. 25, 1254-1264. [CrossRef]

- Tsunemi, T. and Krainc, D. (2014) Zn²⁺ dyshomeostasis caused by loss of ATP13A2/PARK9 leads to lysosomal dysfunction and alpha-synuclein accumulation. Hum Mol Genet. 23, 2791-2801.

- Youle, R. J. and van der Bliek, A. M. (2012) Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. 337, 1062-1065.

- Cao, M., Luo, X., Wu, K. and He, X. (2021) Targeting lysosomes in human disease: from basic research to clinical applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6, 379. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T., Terman, A., Gustafsson, B. and Brunk, U. T. (2008) Lysosomes in iron metabolism, ageing and apoptosis. Histochem Cell Biol. 129, 389-406.

- Nixon, R. A. (2016) New perspectives on lysosomes in ageing and neurodegenerative disease. Ageing Res Rev. 32, 1. [CrossRef]

- Deus, C. M., Yambire, K. F., Oliveira, P. J. and Raimundo, N. (2020) Mitochondria-Lysosome Crosstalk: From Physiology to Neurodegeneration. Trends Mol Med. 26, 71-88. [CrossRef]

- Kiraly, S., Stanley, J. and Eden, E. R. (2025) Lysosome-Mitochondrial Crosstalk in Cellular Stress and Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 14. [CrossRef]

- Malpartida, A. B., Williamson, M., Narendra, D. P., Wade-Martins, R. and Ryan, B. J. (2021) Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Mitophagy in Parkinson's Disease: From Mechanism to Therapy. Trends Biochem Sci. 46, 329-343. [CrossRef]

- Dan, X., Croteau, D. L., Liu, W., Chu, X., Robbins, P. D. and Bohr, V. A. (2025) Mitochondrial accumulation and lysosomal dysfunction result in mitochondrial plaques in Alzheimer's disease. bioRxiv.

- Bedard, K. and Krause, K. H. (2007) The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 87, 245-313. [CrossRef]

- Belarbi, K., Cuvelier, E., Destée, A., Gressier, B. and Chartier-Harlin, M. C. (2017) NADPH oxidases in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Mol Neurodegener. 12, 84.

- Vermot, A., Petit-Hartlein, I., Smith, S. M. E. and Fieschi, F. (2021) NADPH Oxidases (NOX): An Overview from Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology and Pathology. Antioxidants (Basel). 10.

- Noreng, S., Ota, N., Sun, Y., Ho, H., Johnson, M., Arthur, C. P., Schneider, K., Lehoux, I., Davies, C. W., Mortara, K., Wong, K., Seshasayee, D., Masureel, M., Payandeh, J., Yi, T. and Koerber, J. T. (2022) Structure of the core human NADPH oxidase NOX2. Nat Commun. 13, 6079. [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, J. D. and Neish, A. S. (2014) Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: a double-edged sword revisited. Annu Rev Pathol. 9, 119-145. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. M., Geng, L., Cahill-Smith, S., Liu, F., Douglas, G., McKenzie, C. A., Smith, C., Brooks, G., Channon, K. M. and Li, J. M. (2019) Nox2 contributes to age-related oxidative damage to neurons and the cerebral vasculature. J Clin Invest. 129, 3374-3386. [CrossRef]

- Keeney, M. T., Hoffman, E. K., Farmer, K., Bodle, C. R., Fazzari, M., Zharikov, A., Castro, S. L., Hu, X., Mortimer, A., Kofler, J. K., Cifuentes-Pagano, E., Pagano, P. J., Burton, E. A., Hastings, T. G., Greenamyre, J. T. and Di Maio, R. (2022) NADPH oxidase 2 activity in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 170, 105754. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. P. (2009) How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, C. L., Perevoshchikova, I. V., Hey-Mogensen, M., Orr, A. L. and Brand, M. D. (2013) Sites of reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria oxidizing different substrates. Redox Biol. 1, 304-312. [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F., Fernandez-Ayala, D. J. and Sanz, A. (2017) Role of Mitochondrial Reverse Electron Transport in ROS Signaling: Potential Roles in Health and Disease. Front Physiol. 8, 428. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N. K., Lee, M., Orr, A. L. and Nakamura, K. (2024) Systems-level analyses dissociate genetic regulators of reactive oxygen species and energy production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121, e2307904121. [CrossRef]

- Protasoni, M., Perez-Perez, R., Lobo-Jarne, T., Harbour, M. E., Ding, S., Penas, A., Diaz, F., Moraes, C. T., Fearnley, I. M., Zeviani, M., Ugalde, C. and Fernandez-Vizarra, E. (2020) Respiratory supercomplexes act as a platform for complex III-mediated maturation of human mitochondrial complexes I and IV. EMBO J. 39, e102817. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H., Tsai, P. I., Lin, H. Y., Hattori, N., Funayama, M., Jeon, B., Sato, K., Abe, K., Mukai, Y., Takahashi, Y., Li, Y., Nishioka, K., Yoshino, H., Daida, K., Chen, M. L., Cheng, J., Huang, C. Y., Tzeng, S. R., Wu, Y. S., Lai, H. J., Tsai, H. H., Yen, R. F., Lee, N. C., Lo, W. C., Hung, Y. C., Chan, C. C., Ke, Y. C., Chao, C. C., Hsieh, S. T., Farrer, M. and Wu, R. M. (2020) Mitochondrial UQCRC1 mutations cause autosomal dominant parkinsonism with polyneuropathy. Brain. 143, 3352-3373. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F., Garcia, S., Padgett, K. R. and Moraes, C. T. (2012) A defect in the mitochondrial complex III, but not complex IV, triggers early ROS-dependent damage in defined brain regions. Hum Mol Genet. 21, 5066-5077. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A. L., Nissanka, N., Louzada, R. A., Tamayo, A., Pereira, E., Moraes, C. T. and Caicedo, A. (2023) A Defect in Mitochondrial Complex III but Not in Complexes I or IV Causes Early beta-Cell Dysfunction and Hyperglycemia in Mice. Diabetes. 72, 1262-1276. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M., Diaz, F., Nissanka, N., Guastucci, C. S., Illiano, P., Brambilla, R. and Moraes, C. T. (2022) Adult-Onset Deficiency of Mitochondrial Complex III in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease Decreases Amyloid Beta Plaque Formation. Mol Neurobiol. 59, 6552-6566. [CrossRef]