Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

| Rank | Name of Countries | DMUs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Switzerland | SWZ |

| 2 | United States of America | USA |

| 3 | Sweden | SWD |

| 4 | United Kingdom | UNK |

| 5 | Netherlands | NDL |

| 6 | South Korea | KOR |

| 7 | Singapore | SGP |

| 8 | Germany | GMN |

| 9 | Finland | FNL |

| 10 | Denmark | DMK |

| 11 | China | CHN |

| 12 | France | FRN |

| 13 | Japan | JPN |

| 14 | Hongkong | HNK |

| 15 | Canada | CND |

| 16 | Austria | AST |

| 17 | Estonia | EST |

| 18 | Israel | ISR |

| 19 | Luxembourg | LXM |

| 20 | Iceland | ICL |

| Variables | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Innovation Index (II) Capital Investment (CI) Trade Openness (TO) High Tech Exports (HTE) Gross Domestic Product (GDP) |

Innovation score (0-100). Calculated new plant and equipment purchases by firms, as a percentage of GDP. Sum of exports and imports divided by GDP. Percent of exported manufactured products with high research and development intensity. Total monetary value of all final goods and services produced in billion USD. |

| Outputs | Labor Force (LF) Unemployment Rate (UR) |

The population 15 years and over who are either employed, unemployed, or seeking employment. Unemployed individuals in an economy among individuals currently in labor force |

| Year | Statistics | (I)-II | (I)-CI | (I)-TO | (I)-HTE | (I)-GDP | (O)-LF | (O)-UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Max | 68.400 | 43.790 | 376.890 | 64.650 | 20533.060 | 776.280 | 9.020 |

| Min | 50.500 | 17.040 | 27.610 | 6.970 | 26.260 | 0.220 | 2.470 | |

| Average | 57.075 | 24.677 | 124.415 | 22.672 | 2854.104 | 60.536 | 4.653 | |

| SD | 4.496 | 5.401 | 102.563 | 13.899 | 5086.519 | 168.350 | 1.583 | |

| Year 2 | Max | 67.200 | 43.250 | 382.350 | 65.560 | 21380.980 | 775.320 | 8.410 |

| Min | 50.000 | 18.190 | 26.450 | 6.570 | 24.680 | 0.220 | 2.350 | |

| Average | 57.155 | 24.310 | 123.292 | 23.329 | 2906.832 | 60.703 | 4.474 | |

| SD | 4.361 | 5.326 | 102.210 | 14.320 | 5278.262 | 168.185 | 1.483 | |

| Year 3 | Max | 66.100 | 43.370 | 372.270 | 69.650 | 21060.470 | 751.450 | 9.660 |

| Min | 48.300 | 17.350 | 23.380 | 5.620 | 21.570 | 0.220 | 2.810 | |

| Average | 55.480 | 24.614 | 117.805 | 23.797 | 2891.527 | 59.337 | 5.723 | |

| SD | 4.473 | 5.757 | 103.607 | 14.977 | 5267.564 | 163.084 | 1.820 | |

| Year 4 | Max | 65.500 | 43.140 | 402.510 | 65.500 | 23315.080 | 780.370 | 8.720 |

| Min | 49.000 | 16.780 | 25.480 | 49.000 | 25.600 | 0.220 | 2.830 | |

| Average | 56.225 | 24.902 | 127.289 | 56.225 | 3273.465 | 60.878 | 5.473 | |

| SD | 4.285 | 5.568 | 110.981 | 4.285 | 5998.516 | 169.227 | 1.500 | |

| Year 5 | Max | 64.600 | 43.290 | 388.510 | 34.810 | 25439.700 | 781.830 | 781.830 |

| Min | 49.500 | 14.960 | 27.360 | 5.870 | 28.060 | 0.230 | 0.230 | |

| Average | 55.360 | 25.238 | 135.889 | 19.668 | 3325.903 | 61.262 | 61.262 | |

| SD | 4.411 | 5.921 | 105.952 | 7.256 | 6368.976 | 169.602 | 169.602 |

2.2. DEA Super Efficiency Slacks-Based Measure Model

2.3. DEA Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI)

3. Results

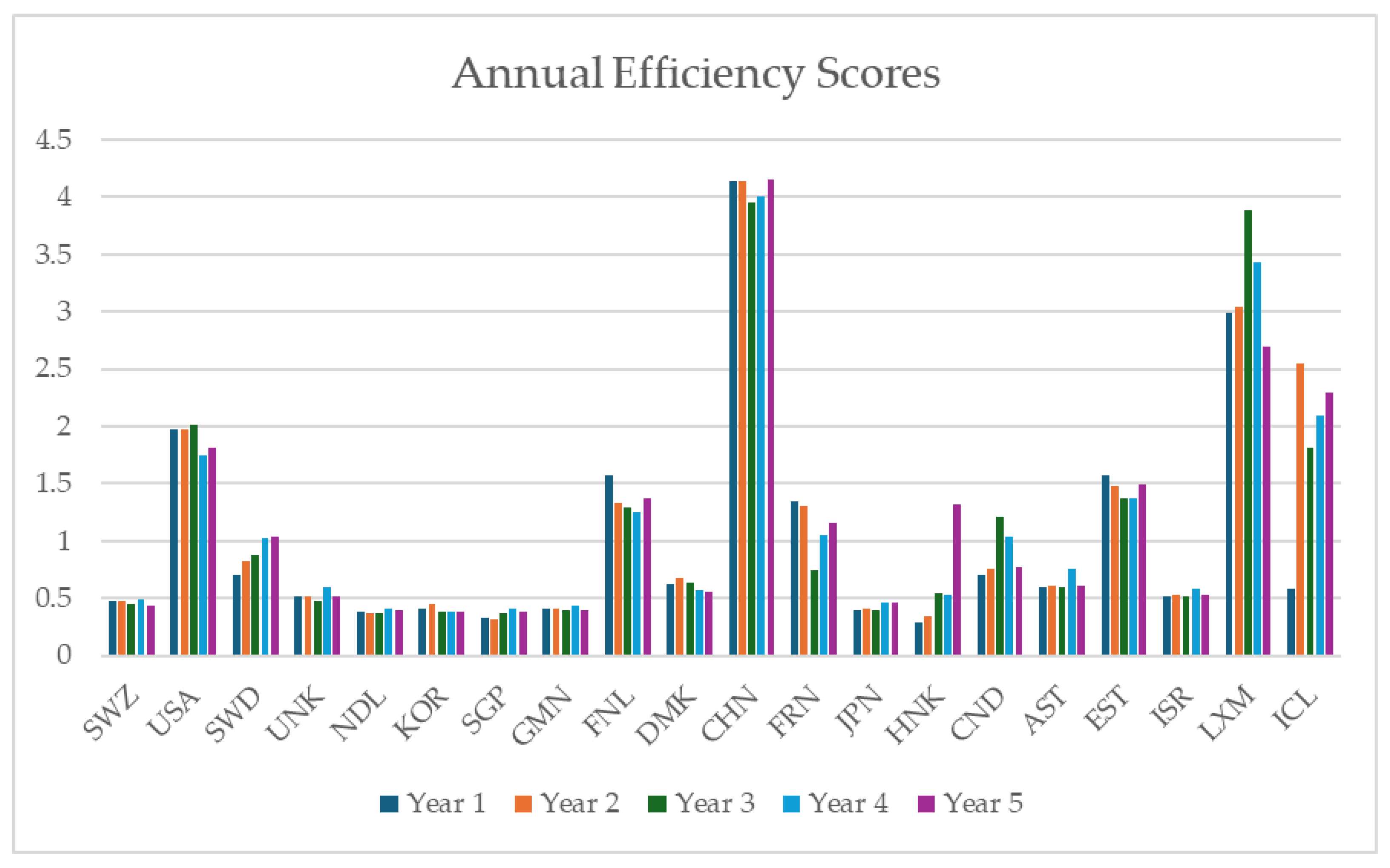

3.1. Efficiency Analysis Using Super-SBM Model

| DMU | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| SWZ | 0.471 | 14 | 0.481 | 14 | 0.445 | 15 | 0.490 | 15 | 0.434 | 16 | 0.464 | 15 |

| USA | 1.980 | 3 | 1.974 | 4 | 2.020 | 3 | 1.746 | 4 | 1.808 | 4 | 1.905 | 3 |

| SWD | 0.700 | 8 | 0.818 | 8 | 0.880 | 8 | 1.025 | 9 | 1.037 | 9 | 0.892 | 9 |

| UNK | 0.511 | 13 | 0.512 | 13 | 0.471 | 14 | 0.596 | 11 | 0.519 | 14 | 0.522 | 14 |

| NDL | 0.384 | 18 | 0.368 | 18 | 0.367 | 20 | 0.415 | 18 | 0.401 | 18 | 0.387 | 19 |

| KOR | 0.406 | 16 | 0.444 | 15 | 0.380 | 18 | 0.383 | 20 | 0.376 | 20 | 0.398 | 18 |

| SGP | 0.331 | 19 | 0.314 | 20 | 0.369 | 19 | 0.407 | 19 | 0.384 | 19 | 0.361 | 20 |

| GMN | 0.414 | 15 | 0.415 | 16 | 0.395 | 16 | 0.429 | 17 | 0.402 | 17 | 0.411 | 17 |

| FNL | 1.577 | 4 | 1.336 | 6 | 1.288 | 6 | 1.254 | 6 | 1.372 | 6 | 1.365 | 6 |

| DMK | 0.621 | 9 | 0.670 | 10 | 0.636 | 10 | 0.573 | 13 | 0.551 | 12 | 0.610 | 11 |

| CHN | 4.140 | 1 | 4.138 | 1 | 3.948 | 1 | 4.004 | 1 | 4.159 | 1 | 4.078 | 1 |

| FRN | 1.349 | 6 | 1.307 | 7 | 0.737 | 9 | 1.053 | 7 | 1.152 | 8 | 1.120 | 7 |

| JPN | 0.401 | 17 | 0.410 | 17 | 0.389 | 17 | 0.458 | 16 | 0.468 | 15 | 0.425 | 16 |

| HNK | 0.286 | 20 | 0.336 | 19 | 0.543 | 12 | 0.524 | 14 | 1.318 | 7 | 0.601 | 12 |

| CND | 0.707 | 7 | 0.751 | 9 | 1.215 | 7 | 1.037 | 8 | 0.770 | 10 | 0.896 | 8 |

| AST | 0.594 | 10 | 0.607 | 11 | 0.597 | 11 | 0.751 | 10 | 0.611 | 11 | 0.632 | 10 |

| EST | 1.569 | 5 | 1.475 | 5 | 1.371 | 5 | 1.377 | 5 | 1.495 | 5 | 1.457 | 5 |

| ISR | 0.513 | 12 | 0.532 | 12 | 0.510 | 13 | 0.584 | 12 | 0.526 | 13 | 0.533 | 13 |

| LXM | 2.987 | 2 | 3.047 | 2 | 3.884 | 2 | 3.437 | 2 | 2.690 | 2 | 3.209 | 2 |

| ICL | 0.587 | 11 | 2.549 | 3 | 1.810 | 4 | 2.088 | 3 | 2.289 | 3 | 1.865 | 4 |

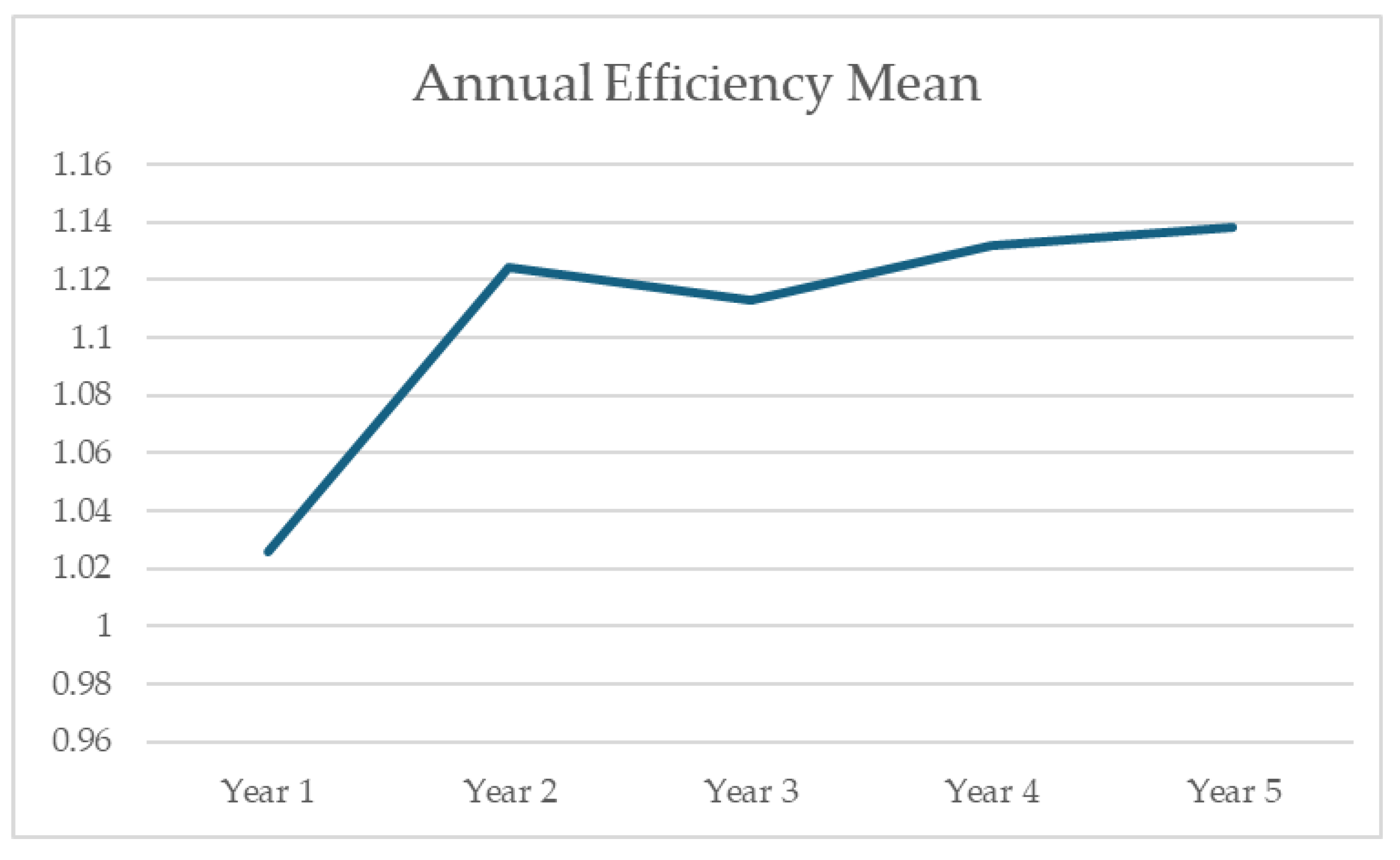

| Mean | 1.026 | 1.124 | 1.113 | 1.132 | 1.138 | 1.107 | ||||||

3.2. Performance Trends Over Time Analysis Using Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI)

3.2.1. Overall Efficiency Analysis

3.2.2. Frontier Shift Index

3.2.3. Malmquist Productivity Index

| Malmquist | Year 1 -Year 2 | Year 2 -Year 3 | Year 3 -Year 4 | Year 4 -Year 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 0.939 | 1.068 | 1.041 | 0.782 | 0.957 |

| USA | 0.934 | 1.854 | 0.664 | 0.707 | 1.039 |

| SWD | 1.067 | 1.302 | 1.027 | 0.790 | 1.046 |

| UNK | 0.933 | 1.224 | 1.029 | 0.626 | 0.953 |

| NDL | 0.889 | 1.141 | 1.070 | 0.859 | 0.990 |

| KOR | 1.007 | 1.063 | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.956 |

| SGP | 0.883 | 1.348 | 1.044 | 0.838 | 1.028 |

| GMN | 0.937 | 1.218 | 0.911 | 0.852 | 0.980 |

| FNL | 0.841 | 1.147 | 0.912 | 0.998 | 0.974 |

| DMK | 0.988 | 1.106 | 0.850 | 0.856 | 0.950 |

| CHN | 1.011 | 0.982 | 0.980 | 1.063 | 1.009 |

| FRN | 0.930 | 0.921 | 0.955 | 0.879 | 0.921 |

| JPN | 0.978 | 1.167 | 0.959 | 0.929 | 1.008 |

| HNK | 1.098 | 2.337 | 0.919 | 0.966 | 1.330 |

| CND | 0.969 | 1.938 | 0.717 | 0.641 | 1.066 |

| AST | 0.938 | 1.141 | 1.185 | 0.662 | 0.982 |

| EST | 0.804 | 1.335 | 0.842 | 1.085 | 1.017 |

| ISR | 0.967 | 1.114 | 1.069 | 0.630 | 0.945 |

| LXM | 1.034 | 1.310 | 0.660 | 0.883 | 0.972 |

| ICL | 1.647 | 1.779 | 1.047 | 0.564 | 1.259 |

| Average | 0.990 | 1.325 | 0.938 | 0.825 | 1.019 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

- Global Innovation Index: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/GII_Index/OECD/

- World Bank Open Data: https://data.worldbank.org/

- OECD Statistics: https://stats.oecd.org/

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DMU | GDP | CI | TO | II | HTE | LF | UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 492.398 | 9.439 | 74.427 | 30.184 | 7.439 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 43.5 | 27.909 | 18.668 | 28.153 | 981.83 | 2.469 |

| SWD | 263.607 | 4.06 | 21.596 | 11.527 | 6.263 | 0 | 0 |

| UNK | 2137.791 | 3.214 | 22.395 | 26.935 | 16.301 | 0 | 0 |

| NDL | 630.887 | 7.515 | 118.215 | 32.1 | 17.529 | 0 | 0 |

| KOR | 1102.145 | 17.361 | 38.695 | 25.03 | 30.79 | 0 | 0 |

| SGP | 204.033 | 12.286 | 286.871 | 30.517 | 47.064 | 0 | 0 |

| GMN | 3091.238 | 8.718 | 53.065 | 29.627 | 10.151 | 0 | 0 |

| FNL | 367.086 | 4.83 | 24.954 | 13.421 | 7.366 | 3.499 | 0 |

| DMK | 145.641 | 4.946 | 52.482 | 16.833 | 6.027 | 0 | 0 |

| CHN | 82526.38 | 55.81 | 92.084 | 227.715 | 55.183 | 0 | 14.004 |

| FRN | 0 | 13.637 | 41.008 | 29.195 | 0 | 6.775 | 0 |

| JPN | 3287.267 | 16.555 | 18.43 | 37.968 | 8.663 | 0 | 0 |

| HNK | 203.989 | 12.231 | 347.069 | 31.776 | 61.106 | 0 | 0 |

| CND | 1184.654 | 2.649 | 4.751 | 5.282 | 7.647 | 0 | 0 |

| AST | 220.707 | 8.699 | 55.575 | 11.312 | 5.513 | 0 | 0 |

| EST | 36.966 | 0 | 129.618 | 22.735 | 5.407 | 0 | 0 |

| ISR | 183.657 | 10.283 | 17.273 | 24.995 | 17.648 | 0 | 0 |

| LXM | 5.051 | 52.578 | 0 | 70.926 | 38.159 | 1.429 | 7.747 |

| ICL | 10.864 | 8.017 | 15.272 | 25.809 | 14.334 | 0.132 | 0 |

| DMU | GDP | CI | TO | II | HTE | LF | UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 487.598 | 10.522 | 71.965 | 27.902 | 6.766 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 43.437 | 27.287 | 20.35 | 27.476 | 993.764 | 3.158 |

| SWD | 211.593 | 0.434 | 10.217 | 2.601 | 5.013 | 0 | 0 |

| UNK | 2096.97 | 3.762 | 20.952 | 27.267 | 16.879 | 0 | 0 |

| NDL | 627.342 | 9.649 | 115.24 | 31.041 | 18.121 | 0 | 0 |

| KOR | 1004.007 | 17.041 | 31.783 | 22.585 | 26.372 | 0 | 0 |

| SGP | 211.389 | 13.359 | 284.864 | 30.649 | 47.471 | 0 | 0 |

| GMN | 2976.968 | 9.067 | 51.979 | 29.349 | 10.688 | 0 | 0 |

| FNL | 254.427 | 0.515 | 9.946 | 2.594 | 4.993 | 2.588 | 0 |

| DMK | 127.539 | 3.74 | 50.506 | 13.51 | 5.099 | 0 | 0 |

| CHN | 84924.71 | 55.672 | 86.834 | 231.479 | 55.806 | 0 | 12.468 |

| FRN | 0 | 10.468 | 37.939 | 27.766 | 0 | 0.692 | 0 |

| JPN | 3334.989 | 16.588 | 17.209 | 37.529 | 8.187 | 0 | 0 |

| HNK | 195.106 | 7.579 | 319.059 | 29.348 | 61.452 | 0 | 0 |

| CND | 1120.522 | 2.127 | 0 | 3.375 | 7.23 | 0 | 0 |

| AST | 210.933 | 8.834 | 53.693 | 10.089 | 5.114 | 0 | 0 |

| EST | 13.598 | 0 | 0 | 15.765 | 27.455 | 0 | 0.282 |

| ISR | 205.535 | 10.029 | 11.945 | 24.012 | 17.873 | 0 | 0 |

| LXM | 12.777 | 50.598 | 0 | 79.491 | 38.487 | 1.542 | 6.246 |

| ICL | 45.186 | 37.889 | 240.28 | 60.897 | 0 | 1.354 | 6.493 |

| DMU | GDP | CI | TO | II | HTE | LF | UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 509.782 | 14.229 | 77.428 | 30.623 | 6.533 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 42.819 | 32.002 | 20.307 | 26.515 | 905.631 | 0 |

| SWD | 75.908 | 0 | 10.531 | 4.093 | 4.072 | 0 | 0 |

| UNK | 1462.009 | 6.188 | 30.302 | 34.708 | 15.114 | 0 | 0 |

| NDL | 618.249 | 9.39 | 111.386 | 30.561 | 17.957 | 0 | 0 |

| KOR | 592.272 | 21.952 | 44.009 | 34.105 | 28.844 | 0 | 0 |

| SGP | 164.916 | 9.589 | 295.024 | 26.439 | 49.919 | 0 | 0 |

| GMN | 2566.758 | 11.557 | 56.511 | 34.351 | 8.261 | 0 | 0 |

| FNL | 200.371 | 0 | 13.089 | 1.221 | 4.966 | 2 | 0 |

| DMK | 137.185 | 4.641 | 51.809 | 16.049 | 5.942 | 0 | 0 |

| CHN | 80856.15 | 52.126 | 71.317 | 221.621 | 57.094 | 0 | 31.52 |

| FRN | 1024.262 | 5.056 | 5.896 | 9.859 | 10.006 | 0 | 0 |

| JPN | 3397.928 | 16.077 | 13.242 | 35.256 | 12.156 | 0 | 0 |

| HNK | 105.54 | 0.554 | 297.175 | 11.483 | 62.117 | 0 | 0 |

| CND | 0 | 8.096 | 22.602 | 17.893 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AST | 198.706 | 9.096 | 51.84 | 11.842 | 5.48 | 0 | 0 |

| EST | 14.144 | 0 | 0 | 25.077 | 18.229 | 0 | 1.509 |

| ISR | 216.596 | 10.788 | 12.577 | 22.812 | 22.75 | 0 | 0 |

| LXM | 10.637 | 66.879 | 0 | 79.052 | 49.816 | 1.562 | 11.511 |

| ICL | 20.967 | 21.092 | 119.74 | 16.293 | 0 | 0.729 | 3.741 |

| DMU | GDP | CI | TO | II | HTE | LF | UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 543.953 | 9.86 | 77.41 | 26.282 | 7.238 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 35.341 | 23.321 | 10.397 | 19.308 | 854.793 | 0.603 |

| SWD | 0 | 1.876 | 0 | 3.245 | 0 | 0.865 | 0 |

| UNK | 2084.15 | 2.414 | 10.82 | 23.97 | 15.222 | 0 | 0 |

| NDL | 681.748 | 7.92 | 113.403 | 26.085 | 16.039 | 0 | 0 |

| KOR | 1055.031 | 19.809 | 42.799 | 30.666 | 30.369 | 0 | 0 |

| SGP | 203.815 | 8.346 | 285.243 | 22.148 | 48.633 | 0 | 0 |

| GMN | 3183.631 | 10.158 | 51.945 | 28.292 | 9.172 | 0 | 0 |

| FNL | 265.53 | 0 | 8.027 | 0 | 2.826 | 2.005 | 0 |

| DMK | 181.35 | 8 | 58.458 | 18.591 | 6.917 | 0 | 0 |

| CHN | 91658.99 | 55.938 | 82.345 | 233.043 | 63.436 | 0 | 20.572 |

| FRN | 0 | 1.268 | 8.565 | 4.247 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| JPN | 2960.941 | 14.368 | 13.546 | 32.739 | 10.666 | 0 | 0 |

| HNK | 122.452 | 0.361 | 348.919 | 13.974 | 63.489 | 0 | 0 |

| CND | 0 | 0 | 8.09 | 2.836 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AST | 174.646 | 7.15 | 44.016 | 1.266 | 2.203 | 0 | 0 |

| EST | 16.45 | 0 | 0 | 21.003 | 21.054 | 0 | 1.999 |

| ISR | 244.972 | 10.021 | 5.339 | 16.424 | 23.01 | 0 | 0 |

| LXM | 7.57 | 57.178 | 0 | 75.985 | 45.602 | 1.423 | 10.229 |

| ICL | 34.773 | 26.819 | 178.103 | 29.206 | 0 | 0.916 | 4.002 |

| DMU | GDP | CI | TO | II | HTE | LF | UR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 564.126 | 7.619 | 80.744 | 28.136 | 23.567 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 40.608 | 26.654 | 16.517 | 14.893 | 938.009 | 3.403 |

| SWD | 0 | 1.924 | 5.421 | 3.987 | 0 | 0.787 | 0 |

| UNK | 2183.211 | 2.983 | 18.901 | 27.563 | 21.286 | 0 | 0 |

| NDL | 669.795 | 7.202 | 128.292 | 28.054 | 16.107 | 0 | 0 |

| KOR | 916.105 | 21.136 | 58.037 | 33.112 | 12.866 | 0 | 0 |

| SGP | 270.63 | 7.815 | 287.218 | 26.869 | 20.623 | 0 | 0 |

| GMN | 2970.151 | 11.431 | 58.094 | 29.888 | 11.247 | 0 | 0 |

| FNL | 251.4 | 0 | 4.537 | 0 | 7.498 | 2.211 | 0 |

| DMK | 184.901 | 6.51 | 67.626 | 18.369 | 10.423 | 0 | 0 |

| CHN | 99566.35 | 52.342 | 88.261 | 230.211 | 59.346 | 0 | 11.883 |

| FRN | 0 | 3.612 | 31.163 | 10.878 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| JPN | 2602.444 | 14.417 | 13.373 | 30.443 | 8.737 | 0 | 0 |

| HNK | 0 | 16.275 | 0 | 25.897 | 0 | 0 | 1.399 |

| CND | 1120.356 | 3.92 | 0 | 7.325 | 4.484 | 0 | 0 |

| AST | 200.127 | 7.946 | 54.686 | 7.903 | 10.404 | 0 | 0 |

| EST | 17.862 | 1.708 | 0 | 21.303 | 26.968 | 0 | 0 |

| ISR | 305.552 | 12.428 | 9.506 | 18.908 | 17.304 | 0 | 0 |

| LXM | 269.048 | 0 | 0 | 5.628 | 29.602 | 3.409 | 0.196 |

| ICL | 43.658 | 34.401 | 229.385 | 44.994 | 0 | 1.144 | 6.695 |

References

- N. Lind and N. Ramondo, “Global Knowledge and Trade Flows: Theory and Measurement,” Cambridge, MA, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. V. Cervantes and R. Cooper, “Labor market implications of education mismatch,” Eur Econ Rev, vol. 148, p. 104179, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Lerner and S. Stern, “Innovation Policy and the Economy: Introduction to Volume 19,” Innovation Policy and the Economy, vol. 19, pp. xi–xiv, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Maryam and Z. Jehan, “Total Factor Productivity Convergence in Developing Countries: Role of Technology Diffusion,” South African Journal of Economics, vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 247–262, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “‘Innovation index by country, around the world TheGlobalEconomy.com,’ TheGlobalEconomy.com. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/GII_Index/OECD/.

- L. Aldieri and C. Vinci, “Green Economy and Sustainable Development: The Economic Impact of Innovation on Employment,” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 3541, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Choi, C. S. Sung, and J. Y. Park, “How Does Technology Startups Increase Innovative Performance? The Study of Technology Startups on Innovation Focusing on Employment Change in Korea,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 551, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A. Amirteimoori, S. Kordrostami, and M. Vaez, “Closest reference point on the strong efficient frontier in data envelopment analysis,” AIMS Mathematics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 811–827, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, Z. Yang, and B. Gui, “Two-stage network data envelopment analysis production games,” AIMS Mathematics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 4925–4961, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Shakouri, M. Salahi, and S. Kordrostami, “Stochastic p-robust approach to two-stage network DEA model,” Quantitative Finance and Economics, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 315–346, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Akram, S. M. U. Shah, M. M. A. Al-Shamiri, and S. A. Edalatpanah, “Extended DEA method for solving multi-objective transportation problem with Fermatean fuzzy sets,” AIMS Mathematics, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 924–961, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lyu, J. Zhang, L. Wang, F. Yang, and Y. Hao, “Towards a win-win situation for innovation and sustainable development: The role of environmental regulation,” Sustainable Development, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1703–1717, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- 13. M. Yi, Y. Wang, M. Yan, L. Fu, and Y. Zhang, “Government R&D Subsidies, Environmental Regulations, and Their Effect on Green Innovation Efficiency of Manufacturing Industry: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt of China,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 1330, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Zeng, H. Guo, and C. Geng, “A Five-Stage DEA Model for Technological Innovation Efficiency of China’s Strategic Emerging Industries, Considering Environmental Factors and Statistical Errors,” Pol J Environ Stud, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 927–941, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Bao, T. Teng, X. Cao, S. Wang, and S. Hu, “The Threshold Effect of Knowledge Diversity on Urban Green Innovation Efficiency Using the Yangtze River Delta Region as an Example,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 17, p. 10600, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Liu, F. He, and J. Ren, “Promoting or Inhibiting? The Impact of Enterprise Environmental Performance on Economic Performance: Evidence from China’s Large Iron and Steel Enterprises,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 6465, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, Y. Yang, M. Yang, and H. Huang, “The impact of environmental regulation on China’s industrial green development and its heterogeneity,” Front Ecol Evol, vol. 10, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Tran, Y. Mao, P. Nathanail, P.-O. Siebers, and D. Robinson, “Integrating slacks-based measure of efficiency and super-efficiency in data envelopment analysis,” Omega (Westport), vol. 85, pp. 156–165, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. G. M. de F. Alves and L. A. Meza, “A review of network DEA models based on slacks-based measure: Evolution of literature, applications, and further research direction,” International Transactions in Operational Research, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 2729–2760, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-N. Wang and N.-L. Nhieu, “Integrated DEA and hybrid ordinal priority approach for multi-criteria wave energy locating: a case study of South Africa,” Soft comput, vol. 27, no. 24, pp. 18869–18883, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang, H. Nguyen, N. Nhieu, and H. Hsu, “A prospect theory extension of data envelopment analysis model for wave-wind energy site selection in New Zealand,” Managerial and Decision Economics, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 539–553, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C.-N. Wang, N.-L. Nhieu, and C.-M. Chen, “Charting sustainable logistics on the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road: a DEA-based approach enhanced by risk considerations through prospect theory,” Humanit Soc Sci Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 398, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- 23. R. K. Goel and M. A. Nelson, “Employment effects of R&D and process innovation: evidence from small and medium-sized firms in emerging markets,” Eurasian Business Review, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 97–123, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Asiedu, S. C. M. Nazirou, D. S. Mousa, S. J. Sabrina, and A. A. Rosemary, “Analysis of Working Capital Sources on Firm Innovation, and Labor Productivity among Manufacturing Firms in DR Congo,” Journal of Financial Risk Management, vol. 10, no. 02, pp. 200–223, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Salimova et al., “Recent trends in labor productivity,” Employee Relations: The International Journal, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 785–802, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Ou and Z. Zhao, “Higher Education Expansion in China, 1999–2003: Impact on Graduate Employability,” China & World Economy, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 117–141, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.-M. Androniceanu, I. Georgescu, M. Tvaronavičienė, and A. Androniceanu, “Canonical Correlation Anal-ysis and a New Composite Index on Digitalization and Labor Force in the Context of the Industrial Revolu-tion 4.0,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 6812, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Ç. Yildirim, S. Yildirim, S. Erdogan, and T. Kantarci, “Innovation—Unemployment Nexus: The case of EU countries,” International Journal of Finance & Economics, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 1208–1219, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lydeka and A. Karaliute, “Assessment of the Effect of Technological Innovations on Unemployment in the European Union Countries,” Engineering Economics, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 130–139, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. and A. M., “Entrepreneurship as a Potential Solution to High Unemployment: A Systematic Review of Growing Research and Lessons For Ghana,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 26–41, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Afzal, R. Lawrey, and J. Gope, “Understanding national innovation system (NIS) using porter’s diamond model (PDM) of competitiveness in ASEAN-05,” Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 336–355, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Oloruntoba and J. T. Oladipo, “Modelling Carbon Emissions Efficiency from UK Higher Education Insti-tutions Using Data Envelopment Analysis,” Journal of Energy Research and Reviews, pp. 1–18, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Kiani Mavi, N. Kiani Mavi, R. Farzipoor Saen, and M. Goh, “Eco-innovation analysis of OECD countries with common weight analysis in data envelopment analysis,” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 162–181, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- AYDIN, “Benchmarking healthcare systems of OECD countries: A DEA – based Malmquist Productivity Index Approach,” Alphanumeric Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 25–40, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tian and Z. Ma, “An Efficiency Analysis Of Chinese Coal Enterprises By Using Malmquist Productivity Indexes,” in Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advances in Energy, Environment and Chemical Science, Paris, France: Atlantis Press, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C.-N. Wang, H. Tibo, V. T. Nguyen, and D. H. Duong, “Effects of the Performance-Based Research Fund and Other Factors on the Efficiency of New Zealand Universities: A Malmquist Productivity Approach,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 15, p. 5939, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. H. Dakpo, P. Jeanneaux, L. Latruffe, C. Mosnier, and P. Veysset, “Three decades of productivity change in French beef production: a Färe-Primont index decomposition,” Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 352–372, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Mitropoulos, I. Mitropoulos, H. Karanikas, and N. Polyzos, “The impact of economic crisis on the Greek hospitals’ productivity,” Int J Health Plann Manage, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 171–184, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. BOZKURT, Ö. TOPÇUOĞLU, and A. ALTINER, “RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PRODUCTIVITY AND DIGITALIZATION WITH TOBIT MODEL BASED ON MALMQUIST INDEX,” Verimlilik Dergisi, pp. 67–78, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Pham, L. Simar, and V. Zelenyuk, “Statistical Inference for Aggregation of Malmquist Productivity Indi-ces,” Oper Res, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Sukmaningrum, A. Hendratmi, S. A. Rusmita, and S. Abdul Shukor, “Productivity analysis of family takaful in Indonesia and Malaysia: Malmquist productivity index approach,” Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 649–665, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, Y. Yang, M. Yang, and H. Huang, “The impact of environmental regulation on China’s industrial green development and its heterogeneity,” Front Ecol Evol, vol. 10, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang and T. Chen, “Efficiency Evaluation and Influencing Factor Analysis of China’s Public Cultural Services Based on a Super-Efficiency Slacks-Based Measure Model,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 3146, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Tone, “A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 130, no. 3, pp. 498–509, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Margaritis, D. Malmquist Productivity Indexes and DEA. In Handbook on Data Envelopment Analysis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 127–150. [CrossRef]

| Catch-up | Year 1 - Year 2 | Year 2 - Year 3 | Year 3 - Year 4 | Year 4 - Year 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 1.022 | 0.923 | 1.101 | 0.887 | 0.983 |

| USA | 1.002 | 1.262 | 0.896 | 0.910 | 1.017 |

| SWD | 1.164 | 1.080 | 1.162 | 0.980 | 1.096 |

| UNK | 1.000 | 0.921 | 1.267 | 0.871 | 1.015 |

| NDL | 0.957 | 0.997 | 1.131 | 0.967 | 1.013 |

| KOR | 1.081 | 0.864 | 1.009 | 0.982 | 0.984 |

| SGP | 0.951 | 1.172 | 1.102 | 0.943 | 1.042 |

| GMN | 0.998 | 0.957 | 1.086 | 0.936 | 0.994 |

| FNL | 0.851 | 0.957 | 0.944 | 1.121 | 0.968 |

| DMK | 1.076 | 0.951 | 0.901 | 0.961 | 0.972 |

| CHN | 0.995 | 0.958 | 1.014 | 1.039 | 1.002 |

| FRN | 1.008 | 0.591 | 1.375 | 1.102 | 1.019 |

| JPN | 1.022 | 0.949 | 1.176 | 1.023 | 1.042 |

| HNK | 1.176 | 1.611 | 0.965 | 1.950 | 1.426 |

| CND | 1.063 | 1.617 | 0.851 | 0.745 | 1.069 |

| AST | 1.021 | 0.985 | 1.258 | 0.814 | 1.019 |

| EST | 0.867 | 0.910 | 0.948 | 1.305 | 1.008 |

| ISR | 1.053 | 0.944 | 1.147 | 0.901 | 1.011 |

| LXM | 1.084 | 1.054 | 0.821 | 0.968 | 0.982 |

| ICL | 1.823 | 1.119 | 1.124 | 0.778 | 1.211 |

| Average | 1.061 | 1.041 | 1.064 | 1.009 | 1.044 |

| Frontier | Year 1 -Year 2 | Year 2 - Year 3 | Year 3 - Year 4 | Year 4 -Year 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWZ | 0.919 | 1.157 | 0.945 | 0.882 | 0.976 |

| USA | 0.932 | 1.468 | 0.741 | 0.777 | 0.980 |

| SWD | 0.917 | 1.206 | 0.883 | 0.806 | 0.953 |

| UNK | 0.933 | 1.328 | 0.812 | 0.719 | 0.948 |

| NDL | 0.929 | 1.145 | 0.946 | 0.889 | 0.977 |

| KOR | 0.931 | 1.229 | 0.865 | 0.899 | 0.981 |

| SGP | 0.929 | 1.151 | 0.948 | 0.889 | 0.979 |

| GMN | 0.939 | 1.272 | 0.839 | 0.911 | 0.990 |

| FNL | 0.989 | 1.198 | 0.966 | 0.890 | 1.011 |

| DMK | 0.918 | 1.163 | 0.943 | 0.890 | 0.979 |

| CHN | 1.016 | 1.025 | 0.966 | 1.023 | 1.008 |

| FRN | 0.923 | 1.558 | 0.695 | 0.797 | 0.993 |

| JPN | 0.957 | 1.230 | 0.816 | 0.909 | 0.978 |

| HNK | 0.933 | 1.451 | 0.952 | 0.496 | 0.958 |

| CND | 0.911 | 1.199 | 0.843 | 0.860 | 0.953 |

| AST | 0.918 | 1.159 | 0.942 | 0.814 | 0.958 |

| EST | 0.928 | 1.466 | 0.888 | 0.831 | 1.029 |

| ISR | 0.919 | 1.181 | 0.932 | 0.700 | 0.933 |

| LXM | 0.954 | 1.243 | 0.804 | 0.913 | 0.978 |

| ICL | 0.903 | 1.589 | 0.932 | 0.725 | 1.037 |

| Average | 0.935 | 1.271 | 0.883 | 0.831 | 0.980 |

| Year | Efficiency Change | Technological Change | TFP Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1-Year 2 | 1.061 | 0.935 | 0.99 |

| Year 2-Year 3 | 1.041 | 1.271 | 1.325 |

| Year 3-Year 4 | 1.064 | 0.883 | 0.938 |

| Year 4-Year 5 | 1.009 | 0.831 | 0.825 |

| Average | 1.044 | 0.98 | 1.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).