Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Ethical Approval

2.3. Clinicopathological Factors and Grouping Criteria

2.4. Radiological Evaluation Criteria

2.5. Statistical Analysis

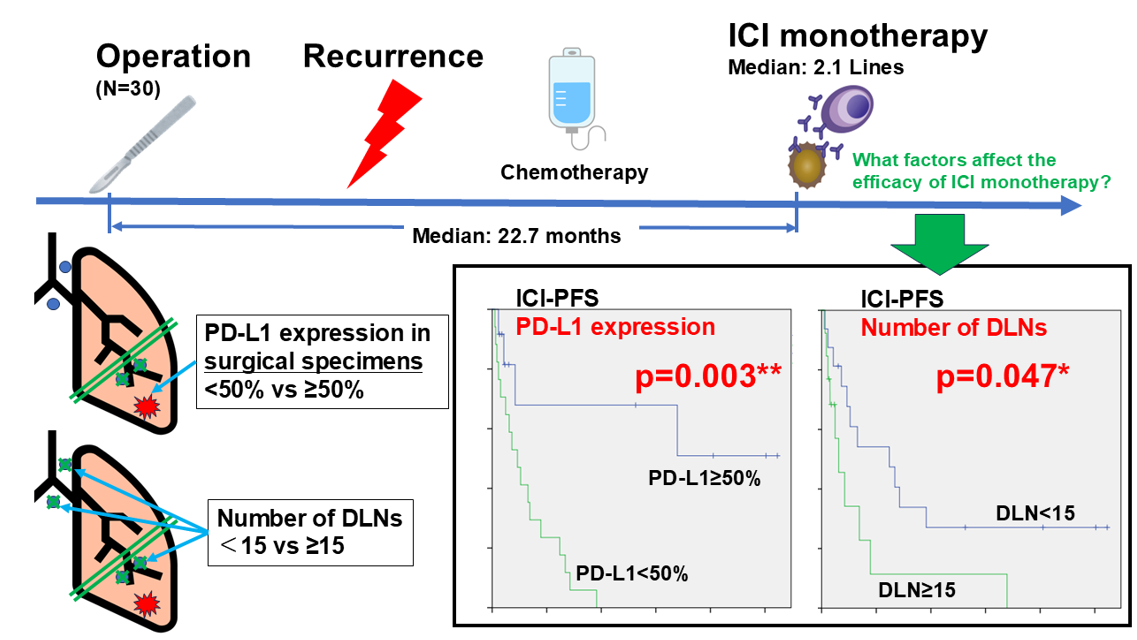

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

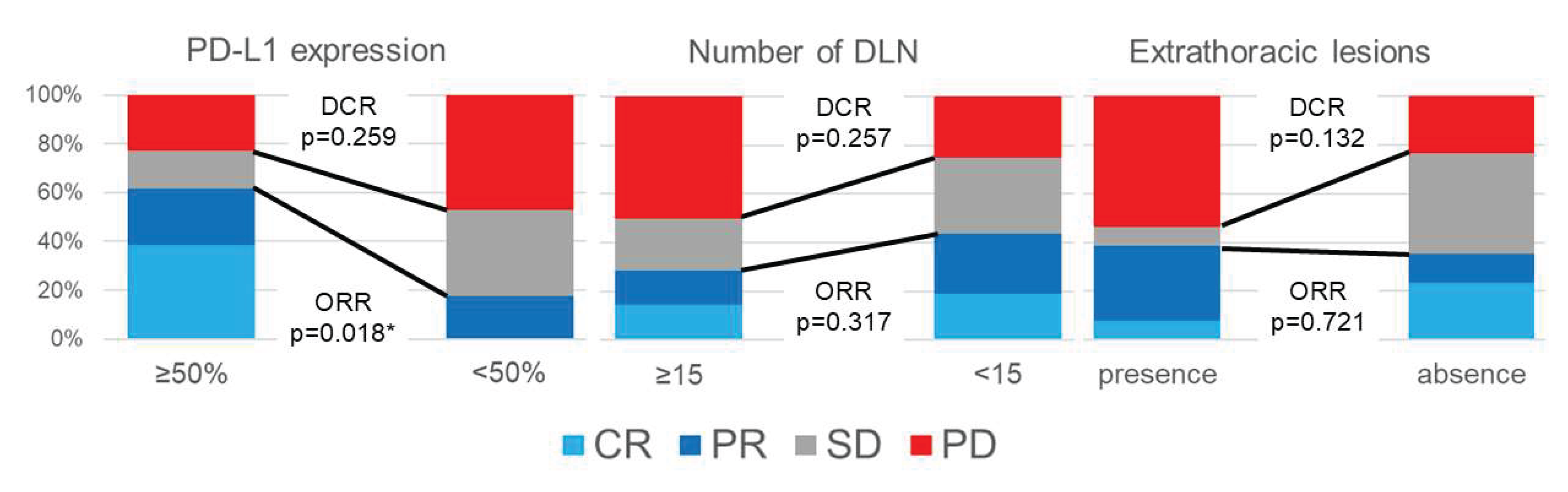

3.2. Radiological Effect of ICI Monotherapy

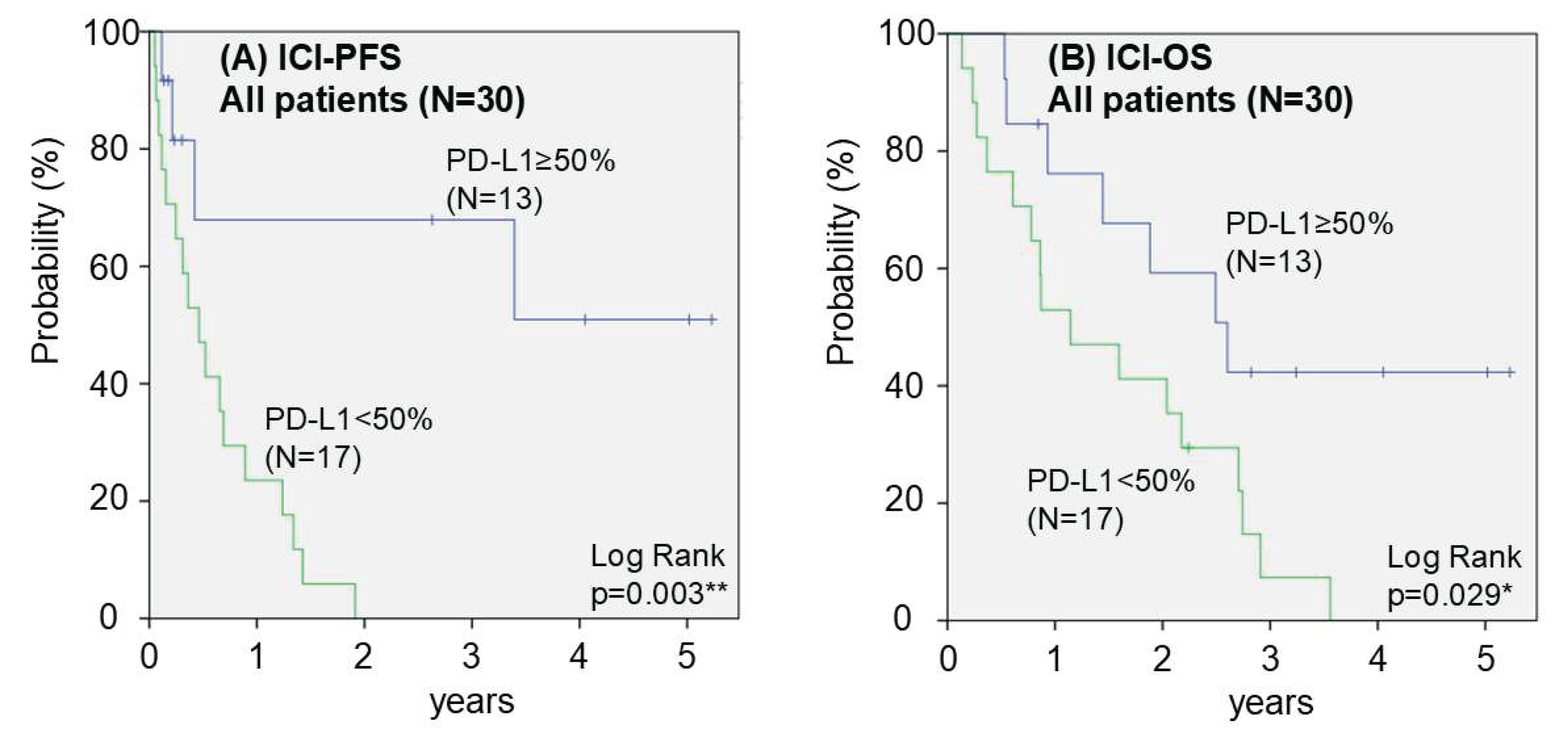

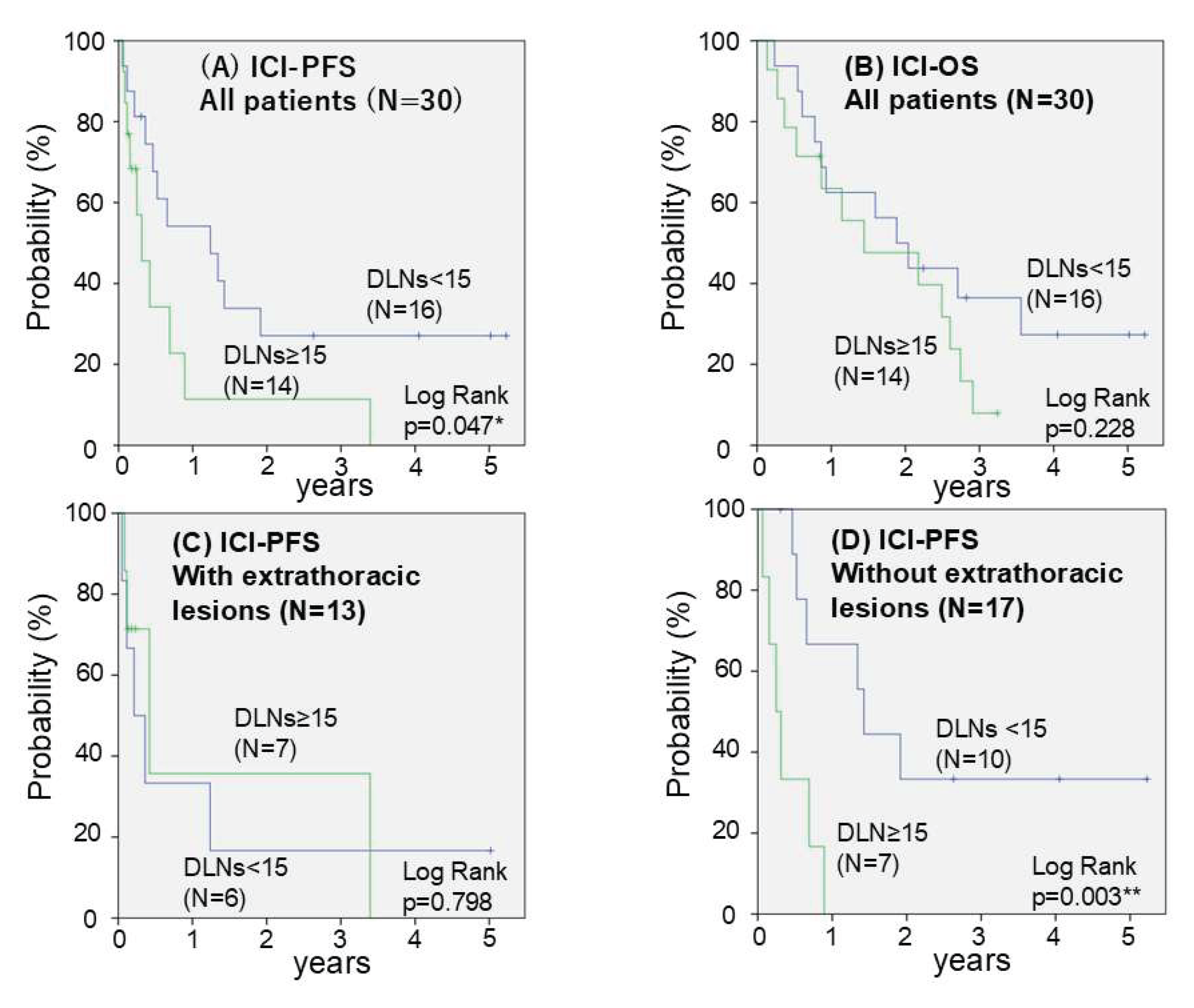

3.3. Prognosis After Initiation of ICI Monotherapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, RL.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okami, J.; Shintani, Y.; Okumura, M.; Ito, H.; Ohtsuka, T.; Toyooka, S.; et al. Demographics, Safety and Quality, and Prognostic Information in Both the Seventh and Eighth Editions of the TNM Classification in 18,973 Surgical Cases of the Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry Database in 2010. J Thorac Oncol. 2019, 14, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, KL.; Baas, P.; Crinò, L.; Eberhardt, WE.; Poddubskaya, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, DR.; Steins, M.; Ready, NE.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 1627–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socinski, MA.; Nishio, M.; Jotte, RM.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; et al. IMpower150 Final Overall Survival Analyses for Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy in First-Line Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021, 16, 1909–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Morabito, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; Conter, HJ.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Barlesi, F.; West, H.; Ball, S.; Bordoni, R.; Cobo, M.; et al. Atezolizumab Plus Chemotherapy for First-Line Treatment of Nonsquamous NSCLC: Results From the Randomized Phase 3 IMpower132 Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021, 16, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassino, MC.; Gadgeel, S.; Speranza, G.; Felip, E.; Esteban, E.; Dómine, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, S.; Kowalski, DM.; Luft, A.; Gümüş, M.; Vicente, D.; Mazières, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felip, E.; Altorki, N.; Zhou, C.; Vallières, E.; Martínez-Martí, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; et al. Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after chemotherapy in resected stage II-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, PM.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, MM.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicer, JD.; Garassino, MC.; Wakelee, H.; Liberman, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M.; et al. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-671): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2024, 404, 1240–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymach, JV.; Harpole, D.; Mitsudomi, T.; Taube, JM.; Galffy, G.; Hochmair, M.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, T.; Awad, MM.; Spicer, JD.; He, J.; Lu, S.; Sepesi, B.; et al. Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Fang, W.; et al. Perioperative Toripalimab Plus Chemotherapy for Patients With Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Neotorch Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024, 331, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountzios, G.; Remon, J.; Hendriks, LEL. ; García-Campelo, R.; Rolfo, C.; Van Schil, P.; et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibition for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer - opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023, 20, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, AG.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Nishioka, N.; Nakamura, T.; Imai, K.; Aoki, T.; Kajiwara, N.; et al. Impact of lymph node dissection on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with postoperative recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2024, 16, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Shirai, S.; Takahara, H.; Nakada, T.; Sakakura, N.; et al. Survival benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer recurrence after completely pulmonary resection. Ann Transl Med. 2021, 9, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, I.; Hamaji, M.; Ozasa, H.; Sakamori, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Yutaka, Y.; et al. Outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors for postoperative recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023, 71, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, EA.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, LH.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009, 45, 228-47. [CrossRef]

- Devasia, RA.; Blackman, A.; Gebretsadik, T.; Griffin, M.; Shintani, A.; May, C.; et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: the effect of duration and timing of fluoroquinolone exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 180, 365–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, MF.; Schoonderwoerd, M.; Knopf, P.; Camps, MG.; Hawinkels, LJ.; Kneilling, M.; et al. Tumor-draining lymph nodes are pivotal in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint therapy. JCI Insight. 2018, 3, e124507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammeijer F, van Gulijk M, Mulder EE, Lukkes M, Klaase L, van den Bosch T, et al. The PD-1/PD-L1-Checkpoint Restrains T cell Immunity in Tumor-Draining Lymph Nodes. Cancer Cell. 2020, 38, 685-700.e8. [CrossRef]

- Saddawi-Konefka R, O'Farrell A, Faraji F, Clubb L, Allevato MM, Jensen SM, et al. Lymphatic-preserving treatment sequencing with immune checkpoint inhibition unleashes cDC1-dependent antitumor immunity in HNSCC. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 4298. [CrossRef]

- Mazo, IB.; Honczarenko, M.; Leung, H.; Cavanagh, LL.; Bonasio, R.; Weninger, W.; et al. Bone marrow is a major reservoir and site of recruitment for central memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2005, 22, 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, AJ.; Huang, RR.; Lee, J.; Itakura, E.; Leong, SP.; Essner, R. ; Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006, 6, 659–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, DH.; Mellor, AL. The tumor-draining lymph node as an immune-privileged site. Immunol Rev. 2006, 213, 146–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, T.; Arigami, T.; Aoki, M.; Matsushita, D.; Shimonosono, M.; Tsuruda, Y.; et al. Difference between sentinel and non-sentinel lymph nodes in the distribution of dendritic cells and macrophages: An immunohistochemical and morphometric study using gastric regional nodes obtained in sentinel node navigation surgery for early gastric cancer. J Anat. 2025, 246, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Kamimura, G.; Harada-Takeda, A.; Nagata, T.; Murakami, G.; Ueda K. Topohistology of dendritic cells and macrophages in the distal and proximal nodes along the lymph flow from the lung. J Anat. 2025. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Blake, SJ.; Yong, MC.; Harjunpää, H.; Ngiow, SF.; Takeda, K.; et al. Improved Efficacy of Neoadjuvant Compared to Adjuvant Immunotherapy to Eradicate Metastatic Disease. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, SP.; Othus, M.; Chen, Y.; Wright, GP Jr.; Yost, KJ.; Hyngstrom, JR.; et al. Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant or Adjuvant-Only Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 813-823. [CrossRef]

- Martins, RS.; Razi, SS.; Alnajar, A.; Poulikidis, K.; Latif, MJ.; Luo, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant vs Adjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy for Stage II-IIIB Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024, 118, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazono, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Tsuta, K.; Utsumi, H.; Kanda, S.; Horinouchi, H.; et al. Reliability of Small Biopsy Samples Compared With Resected Specimens for the Determination of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression in Non--Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015, 16, 385–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, JH.; Sorensen, SF.; Choi, YL.; Feng, Y.; Kim, TE.; Choi, H.; et al. Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression in Paired Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumor Samples. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017, 18, e473–e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojkó, L.; Reiniger, L.; Téglási, V.; Fábián, K.; Pipek, O.; Vágvölgyi, A.; et al. Chemotherapy treatment is associated with altered PD-L1 expression in lung cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018, 144, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacour, M.; Hiltbrunner, S.; Lee, SY.; Soltermann, A.; Rushing, EJ.; Soldini, D.; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Increases Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Expression in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Recurrence. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019, 20, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, HY.; Li, J.; Tao, L.; Lam, AK.; Chan, KW.; Ko, JMY.; et al. Chemotherapeutic Treatments Increase PD-L1 Expression in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma through EGFR/ERK Activation. Transl Oncol. 2018, 11, 1323-1333. [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, SL.; Hodi, FS.; Brahmer, JR.; Gettinger, SN.; Smith, DC.; McDermott, DF,l et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366, 2443-54. [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, PT.; Bhatia, S.; Lipson, EJ.; Kudchadkar, RR.; Miller, NJ.; Annamalai, L.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016, 374, 2542–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, SL.; Taube, JM.; Anders, RA.; Pardoll, DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Male | 23 (76.7%) |

| Female | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Age | Median (range) | 71years (53-82) |

| Smoking | Ever | 27 (90.0%) |

| Never | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Brinkman Index | Median (range) | 970 (0-3600) |

| Surgical Procedure | Wedge resection | 3 (10.0%) |

| Segmentectomy | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Lobectomy | 20 (66.7%) | |

| Bi-lobectomy | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Number of DLN | Median (range) | 14 (0-39) |

| Histlogical type | Adenocarcinoma | 21 (70.0%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 8 (26.7%) | |

| Large cell carcinoma | 1 (3.3%) | |

| PD-L1 expression in surgical specimens | no expression | 7 (23.3%) |

| Low expression | 10 (33.3%) | |

| High expression | 13 (43.3%) | |

| Extrathoracic lesions | presence | 13 (43.3%) |

| absence | 17 (56.7%) | |

| Generic name of ICIs | Nivolumab | 17 (56.7%) |

| Pembrolizumab | 10 (33.3%) | |

| Atezolizumab | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Therapeutic Lines of ICIs | First | 7 (23.3%) |

| Second | 16 (53.3%) | |

| Third | 5 (16.7%) | |

| More | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Duration from surgery to initiation of ICIs | Median (range) | 27.7 months(8.4-69.4 months) |

| DLN: Dissected lymph Nodes, PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1, ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor | ||

| Factors | RECIST | ORR (%) |

ORR p-value |

DCR (%) |

DCR p-value |

||||

| CR | PR | SD | PD | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 3 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 34.8 | 0.515 | 56.5 | 0.215 |

| Female | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 42.9 | 85.7 | |||

| Age | >= 70 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 43.8 | 0.371 | 68.8 | 0.707 |

| < 70 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 28.6 | 57.1 | |||

| Brinkman Index | >= 600 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 33.3 | 0.429 | 57.1 | 0.419 |

| < 600 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 44.4 | 77.8 | |||

| Number of DLN | >= 15 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 28.6 | 0.317 | 50.0 | 0.257 |

| < 15 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 43.8 | 75.0 | |||

| Histlogical type | AD | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 38.1 | 0.571 | 66.7 | 0.687 |

| Others | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 33.3 | 55.6 | |||

| PD-L1 expression in surgical specimens | >= 50% | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 61.5 | 0.018* | 76.9 | 0.259 |

| < 50% | 0 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 17.6 | 52.9 | |||

| Extrathoracic lesions | Presence | 1 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 38.5 | 0.721 | 46.2 | 0.132 |

| Absence | 4 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 35.3 | 76.5 | |||

| Therapeutic Lines of ICIs | >= 3rd line | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 28.6 | 0.485 | 71.4 | 1.000 |

| < 3rd line | 4 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 39.1 | 60.9 | |||

| Duration from surgery to initiation of ICIs | >= 2 years | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 41.7 | 0.61 | 66.7 | 1.000 |

| < 2 years | 4 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 33.3 | 61.1 | |||

| ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, CR: Complete Response, PR: Partial Response, SD: Stable Disease, PD: Progressive Disease, ORR: Objective Response Rate, DCR: Disease Control Rate, DLN: Dissected Lymph Nodes, AD: Adenocarcinoma, PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1*: p<0.05 | |||||||||

| Factors | Univariate p-value (log-rank test) |

Multivariate | ||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Gender (Male vs Female) |

0.596 | 1.019 | 0.324 - 3.204 | 0.974 |

| Age (>= 70 vs < 70) |

0.228 | 0.846 | 0.345 - 2.074 | 0.714 |

| Brinkmann Index (>= 600 vs < 600) |

0.425 | 0.985 | 0.364 - 2.668 | 0.977 |

| Number of DLN (>= 15 vs < 15) |

0.047* | 2.702 | 1.064 - 6.849 | 0.037* |

| Histlogical type (AD vs others) |

0.476 | 0.843 | 0.322 - 2.207 | 0.728 |

| PD-L1 expression in surgical specimens (>= 50% vs < 50%) |

0.003** | 0.161 | 0.044 - 0.598 | 0.006** |

| Extrathoracic lesions (Presence vs Absence) |

0.335 | 3.521 | 1.307 - 9.524 | 0.013* |

| Therapeutic Lines of ICIs (>= 3rd vs < 3rd) |

0.342 | 1.295 | 0.477 - 3.516 | 0.612 |

| Duration from surgery to initiation of ICIs | 0.745 | - | ||

| ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, ICI-PFS: Progression Free Survival after initiation of ICI, HR: Hazard Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval, DLN: Dissected Lymph Nodes, AD: adenocarcinoma, PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1 *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).