Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

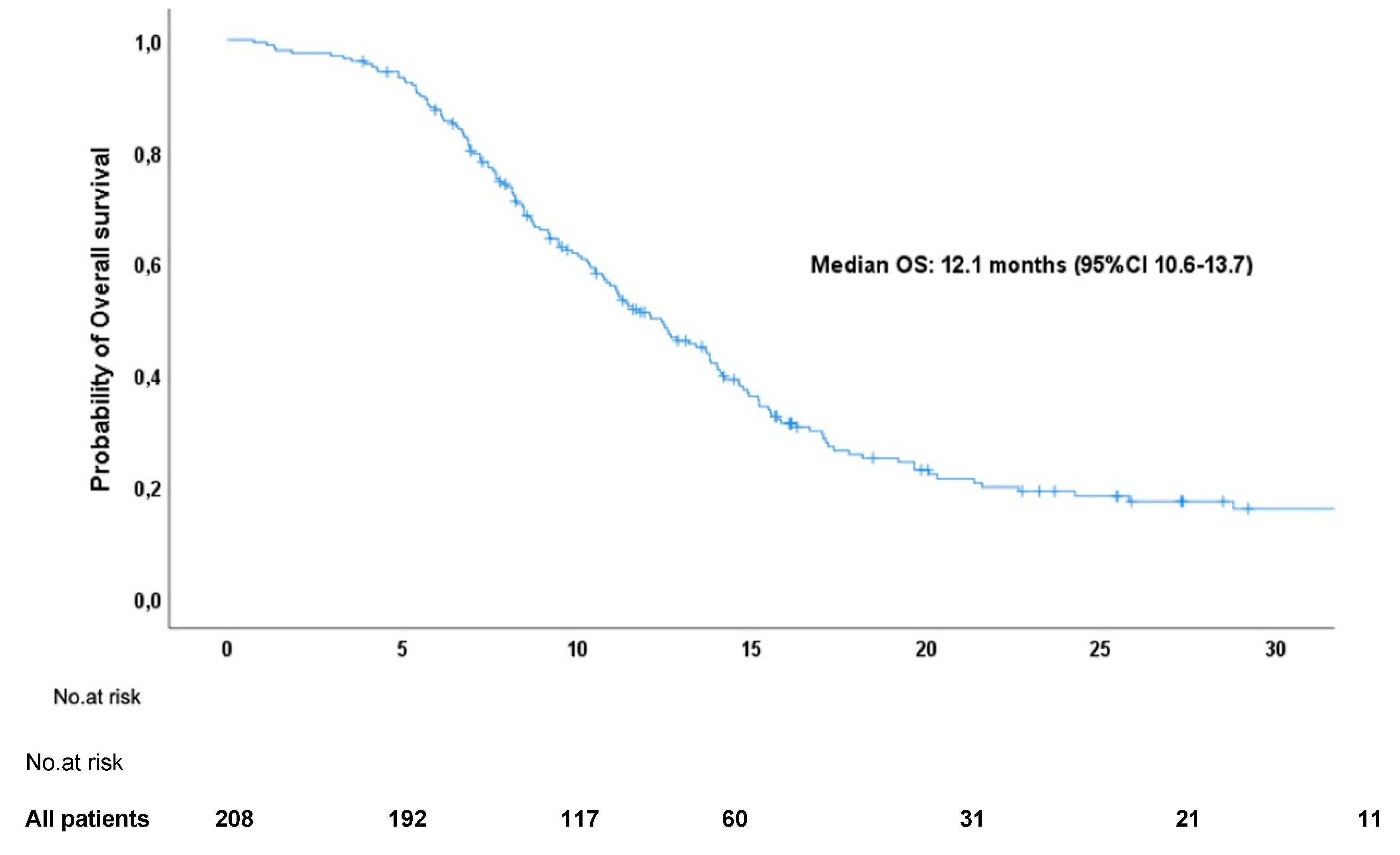

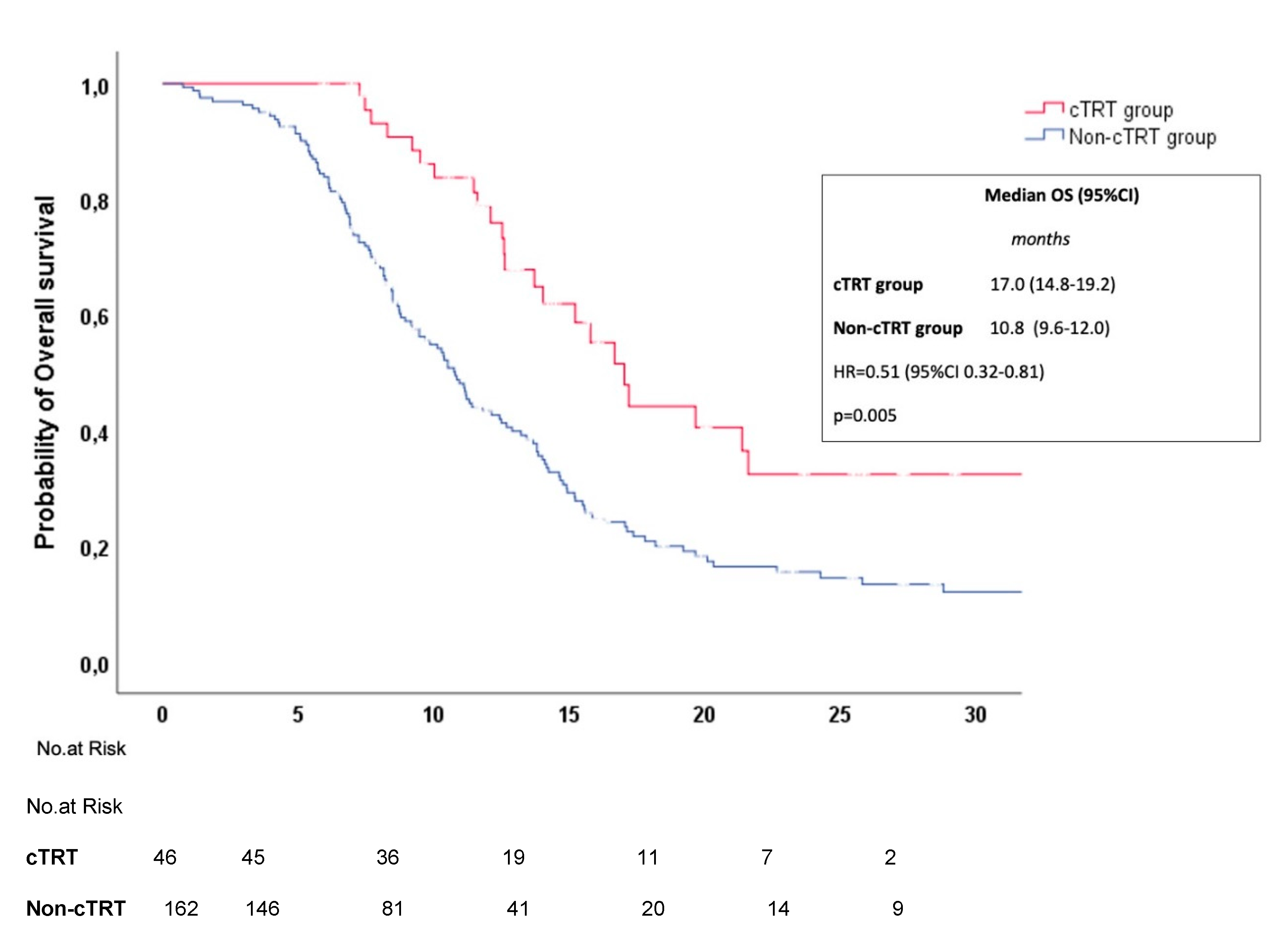

Background: Chemoimmunotherapy (CT/IO) with immune checkpoint inhibitors has recently become the standard of care for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). Given the uncertain role of consolidation thoracic radiotherapy (cTRT) in this setting, we conducted a real-world study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cTRT in ES-SCLC patients receiving first-line CT/IO. Methods: We performed a retrospective analysis of ES-SCLC patients treated with first-line CT/IO in Slovenia from December 2019 to June 2024. Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, survival outcomes, and adverse events were analyzed, with subgroup comparisons based on cTRT administration. Results: Among 208 patients (median age: 66), median overall survival was 12.1 months (95% CI: 10.6–13.7). cTRT was administered to 46 patients (22.1%), who had fewer metastases and received more maintenance IO cycles. cTRT was associated with improved OS (17.0 vs. 10.8 months; HR = 0.51, p = 0.005) and was an independent OS predictor (HR = 0.55, p = 0.013). Grade ≥3 adverse events were similar (21.7% vs. 21.3%), though pneumonitis occurred more frequently with cTRT (6.5% vs. 0%, p = 0.001). Conclusion: cTRT may improve survival in ES-SCLC patients treated with CT/IO, with no significant increase in toxicity apart from pneumonitis. Further prospective studies are needed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Overall Study Population (Baseline Characteristics & Overall Survival Analysis)

3.3. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, Sage J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Jan 14;7(1):3.

- Matera R, Chiang A. What Is New in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2023 Jun;37(3):595-607.

- Micke, P.; Faldum, A.; Metz, T.; Beeh, K.-M.; Bittinger, F.; Hengstler, J.G.; Buhl, R. Staging small cell lung cancer: Veterans Administration Lung Study Group versus International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer—What limits limited disease? Lung Cancer 2002, 37, 271–276, . [CrossRef]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee Advisory Boards and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016 Jan;11(1):39-51.

- Slotman, B.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Kramer, G.; Rankin, E.; Snee, M.; Hatton, M.; Postmus, P.; Collette, L.; Musat, E.; Senan, S. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation in Extensive Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 664–672, . [CrossRef]

- Green RA, Humphrey E, Close H, Patno ME. Alkylating agents in bronchogenic carcinoma. Am J Med. 1969 Apr;46(4):516-25.

- Pietanza MC, Byers LA, Minna JD, Rudin CM. Small cell lung cancer: will recent progress lead to improved outcomes? Clin Cancer Res. 2015 May 15;21(10):2244-55.

- Socinski, M.A.; Smit, E.F.; Lorigan, P.; Konduri, K.; Reck, M.; Szczesna, A.; Blakely, J.; Serwatowski, P.; Karaseva, N.A.; Ciuleanu, T.; et al. Phase III Study of Pemetrexed Plus Carboplatin Compared With Etoposide Plus Carboplatin in Chemotherapy-Naive Patients With Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4787–4792, . [CrossRef]

- Lara PN Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, Lenz HJ, Redman MW, Carleton JE, Jett J, Langer CJ, Kuebler JP, Dakhil SR, Chansky K, Gandara DR. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May 20;27(15):2530-5.

- Palma, D.A.; Warner, A.; Louie, A.V.; Senan, S.; Slotman, B.; Rodrigues, G.B. Thoracic Radiotherapy for Extensive Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Lung Cancer 2015, 17, 239–244, . [CrossRef]

- Jeremic, B.; Shibamoto, Y.; Nikolic, N.; Milicic, B.; Milisavljevic, S.; Dagovic, A.; Aleksandrovic, J.; Radosavljevic-Asic, G. Role of Radiation Therapy in the Combined-Modality Treatment of Patients With Extensive Disease Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 2092–2092, . [CrossRef]

- Slotman, B.J.; van Tinteren, H.; O Praag, J.; Knegjens, J.L.; El Sharouni, S.Y.; Hatton, M.; Keijser, A.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Senan, S. Use of thoracic radiotherapy for extensive stage small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 36–42, . [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.; Mansfield, A.S.; Szczęsna, A.; Havel, L.; Krzakowski, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Huemer, F.; Losonczy, G.; Johnson, M.L.; Nishio, M.; et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2220–2229, . [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, Hochmair MJ, Özgüroğlu M, Ji JH, Voitko O, Poltoratskiy A, Ponce S, Verderame F, Havel L, Bondarenko I, Kazarnowicz A, Losonczy G, Conev NV, Armstrong J, Byrne N, Shire N, Jiang H, Goldman JW; CASPIAN investigators. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019 Nov 23;394(10212):1929-1939; 14. Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, Hochmair MJ, Özgüroğlu M, Ji JH, Voitko O, Poltoratskiy A, Ponce S, Verderame F, Havel L, Bondarenko I, Kazarnowicz A, Losonczy G, Conev NV, Armstrong J, Byrne N, Shire N, Jiang H, Goldman JW; CASPIAN investigators. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019 Nov 23;394(10212):1929-1939.

- Dingemans, A.-M.; Dingemans, A.-M.; Früh, M.; Früh, M.; Ardizzoni, A.; Ardizzoni, A.; Besse, B.; Besse, B.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Faivre-Finn, C.; et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 839–853, . [CrossRef]

- Ganti AKP, Loo BW, Bassetti M, Blakely C, Chiang A, D'Amico TA, D'Avella C, Dowlati A, Downey RJ, Edelman M, Florsheim C, Gold KA, Goldman JW, Grecula JC, Hann C, Iams W, Iyengar P, Kelly K, Khalil M, Koczywas M, Merritt RE, Mohindra N, Molina J, Moran C, Pokharel S, Puri S, Qin A, Rusthoven C, Sands J, Santana-Davila R, Shafique M, Waqar SN, Gregory KM, Hughes M. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021 Dec;19(12):1441-1464.

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). 2021. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm (accessed on).

- Bria, E.; Morgillo, F.; Garassino, M.C.; Ciardiello, F.; Ardizzoni, A.; Stefani, A.; Verderame, F.; Morabito, A.; Chella, A.; Tonini, G.; et al. Atezolizumab Plus Carboplatin and Etoposide in Patients with Untreated Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Interim Results of the MAURIS Phase IIIb Trial. Oncol. 2024, 29, e690–e698, . [CrossRef]

- Garcia Campelo MR, Domine Gomez M, De Castro Carpeno J, Moreno Vega AL, Ponce Aix S, Arriola E, Carcereny Costa E, Majem Tarruella M, Huidobro Vence G, Esteban Gonzalez E, Fuentes Pradera J, Ortega Granados ALO, Guillot Morales M, Massuti Sureda B, Vila Martinez L, Blasco Cordellat A, Fajardo CA, Crama L, Lerones Laborda N, Cobo Dols M, 2022. 1531P Primary results from IMfirst, a phase IIIb open label safety study of atezolizumab (ATZ) + carboplatin (CB)/cisplatin (CP) + etoposide (ET) in an interventional real-world (RW) clinical setting of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) in Spain. Ann. Oncol. 33, S1246–S1247.

- Reinmuth N, ¨ Ozgüro˘ glu M, Leighl NB, Galetta D, Hacibekiroglu I, Roubec J, Sendur MAN, Bria E, Cicin I, Groh´ e C, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, Novello S, Opalka P, Riccardi F, Ruseva RK, Lang S, Hodari M, Donner N, de Marinis F, 2023. LBA2 First-line (1L) durvalumab (D) + platinum-etoposide (EP) for patients (pts) with extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC): primary results from the phase IIIb LUMINANCE study. Immuno-Oncol. Technol. 20.

- Elegbede, A.A.; Gibson, A.J.; Fung, A.S.; Cheung, W.Y.; Dean, M.L.; Bebb, D.G.; Pabani, A. A Real-World Evaluation of Atezolizumab Plus Platinum-Etoposide Chemotherapy in Patients With Extensive-Stage SCLC in Canada. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100249, . [CrossRef]

- Falchero, L.; Guisier, F.; Darrason, M.; Boyer, A.; Dayen, C.; Cousin, S.; Merle, P.; Lamy, R.; Madroszyk, A.; Otto, J.; et al. Long-term effectiveness and treatment sequences in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving atezolizumab plus chemotherapy: Results of the IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO real-world study. Lung Cancer 2023, 185, 107379, . [CrossRef]

- Ezzedine, R.; Canellas, A.; Naltet, C.; Wislez, M.; Azarian, R.; Seferian, A.; Leprieur, E.G. Evaluation of Real-Life Chemoimmunotherapy Combination in Patients with Metastatic Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (SCLC): A Multicentric Case–Control Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 4593, . [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shim, H.S.; Ahn, B.-C.; Lim, S.M.; Kim, H.R.; Cho, B.C.; Hong, M.H. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab, in combination with etoposide and carboplatin regimen, in the first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a single-center experience. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 71, 1093–1101, . [CrossRef]

- Gore, E.M.; Hu, C.; Sun, A.Y.; Grimm, D.F.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Dunlap, N.E.; Higgins, K.A.; Werner-Wasik, M.; Allen, A.M.; Iyengar, P.; et al. Randomized Phase II Study Comparing Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Alone to Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation and Consolidative Extracranial Irradiation for Extensive-Disease Small Cell Lung Cancer (ED SCLC): NRG Oncology RTOG 0937. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 1561–1570, . [CrossRef]

- Simone CB 2nd, Bogart JA, Cabrera AR, Daly ME, DeNunzio NJ, Detterbeck F, Faivre-Finn C, Gatschet N, Gore E, Jabbour SK, Kruser TJ, Schneider BJ, Slotman B, Turrisi A, Wu AJ, Zeng J, Rosenzweig KE. Radiation Therapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020 May-Jun;10(3):158-173.

- Daly, M.E.; Ismaila, N.; Decker, R.H.; Higgins, K.; Owen, D.; Saxena, A.; Franklin, G.E.; Donaldson, D.; Schneider, B.J. Radiation Therapy for Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ASCO Guideline Endorsement of an ASTRO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 931–939, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, P.; et al. Patterns of treatment failure for PD-(L)1 refractory extensive-stage small cell lung cancer in continued PD-(L)1 treatment. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 33, 101687, . [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Ng, B.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Kawashima, N.; Liebes, L.; Formenti, S.C. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2004, 58, 862–870, . [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liang, H.; Burnette, B.; Beckett, M.; Darga, T.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Fu, Y.-X. Irradiation and anti–PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 687–695, . [CrossRef]

- Hanna GG, Illidge T. Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy Combinations in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Promising Future? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016 Nov;28(11):726-731.

- Welsh, J.W.; Heymach, J.V.; Chen, D.; Verma, V.; Cushman, T.R.; Hess, K.R.; Shroff, G.; Tang, C.; Skoulidis, F.; Jeter, M.; et al. Phase I Trial of Pembrolizumab and Radiation Therapy after Induction Chemotherapy for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 266–273, . [CrossRef]

- Li L, Yang D, Min Y, Liao A, Zhao J, Jiang L, Dong X, Deng W, Yu H, Yu R, Zhao J, Shi A. First-line atezolizumab/durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide combined with radiotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2023 Apr 6;23(1):318.

- Xie, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Han, C.; Cong, L.; Li, J.; Meng, X. Real-World Efficacy and Safety of Thoracic Radiotherapy after First-Line Chemo-Immunotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3828, . [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; De-Colle, C.; Potkrajcic, V.; Baumann, D.; Spengler, W.; Gani, C.; Utz, D. Is consolidative thoracic radiotherapy of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer still beneficial in the era of immunotherapy? A retrospective analysis. Strahlenther. und Onkol. 2023, 199, 668–675, . [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Feng, H.; Yao, D.; Meng, R.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, N.; Tan, B.; et al. Real-world outcomes of PD-L1 inhibitors combined with thoracic radiotherapy in the first-line treatment of extensive stage small cell lung cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1–12, . [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.J.; Sheikh, S.; Kharouta, M.; Chaung, K.; Choi, S.; Margevicius, S.; Fu, P.; Machtay, M.; Bruno, D.S.; Dowalti, A.; et al. The Impact of Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation and Consolidative Thoracic Radiation Therapy for Extensive Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Transition to the Chemo-immunotherapy Era: A Single Institution Series. Clin. Lung Cancer 2023, 24, 696–705, . [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.; Della Corte, C.M.; Russo, A.; Spinnato, F.; Ambrosio, F.; Ronga, R.; Marchese, A.; Del Giudice, T.; Sergi, C.; Casaluce, F.; et al. Consolidative thoracic radiation therapy for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer in the era of first-line chemoimmunotherapy: preclinical data and a retrospective study in Southern Italy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1289434, . [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, M.; Na, F. Chemoimmunotherapy combined with consolidative thoracic radiotherapy for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 190, 110014, . [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, L.; Zhao, L.; Cao, Y.; Pang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, P. Timing of thoracic radiotherapy in the treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: important or not?. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 42, . [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Fu, C.; Li, B. Clinical outcomes of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer patients treated with thoracic radiotherapy at different times and fractionations. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1–11, . [CrossRef]

- Perez, B.A.; Kim, S.; Wang, M.; Karimi, A.M.; Powell, C.; Li, J.; Dilling, T.J.; Chiappori, A.; Latifi, K.; Rose, T.; et al. Prospective Single-Arm Phase 1 and 2 Study: Ipilimumab and Nivolumab With Thoracic Radiation Therapy After Platinum Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 109, 425–435, . [CrossRef]

- Stanic, K.; Vrankar, M.; But-Hadzic, J. Consolidation radiotherapy for patients with extended disease small cell lung cancer in a single tertiary institution: impact of dose and perspectives in the era of immunotherapy. Radiol. Oncol. 2020, 54, 353–363, . [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.A.; Senan, S.; Tsujino, K.; Barriger, R.B.; Rengan, R.; Moreno, M.; Bradley, J.D.; Kim, T.H.; Ramella, S.; Marks, L.B.; et al. Predicting Radiation Pneumonitis After Chemoradiation Therapy for Lung Cancer: An International Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 85, 444–450, . [CrossRef]

| Characteristics at diagnosis | All included patients (N=208) |

| Median Age (years) | 66 (range 41-79) |

| Age ≥ 65 y (%) | 55.3 |

| Male Patients (%) | 55.8 |

| Smokers (former/current) (%) | 98.6 |

| ECOG PS 0-1 (%) | 74 |

| Brain Metastasis (%) | 19.7 |

| Liver Metastasis (%) | 43.8 |

| Bone Metastasis (%) | 34.1 |

| Patients with ≥ 3 Metastatic Sites (%) | 34.6 |

| Median LDH | 4.29 (95% CI 3.98; 4.79) |

| Patients with Elevated LDH (%) | 53.4 |

| Variable | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.67 (0.49–0.93) | 0.017 | 0.57 (0.40–0.80) | 0.035 |

| ECOG PS (≥2 vs. 0–1) | 1.76 (1.23–2.52) | 0.002 | 1.98 (1.34–2.92) | 0.001 |

| Liver Metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.68 (1.22–2.32) | 0.001 | 1.34 (0.94–1.91) | 0.109 |

| Bone Metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.55 (1.12–2.16) | 0.009 | 1.00 (0.70–1.43) | 0.984 |

| Metastatic sites (≥3 vs. 0-2) | 2.09 (1.50–2.92) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.12–2.34) | 0.011 |

| cTRT (yes vs. no) | 0.44 (0.28–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.34–0.88) | 0.013 |

| LDH (high vs. normal) | 1.76 (1.27–2.44) | 0.001 | 1.23 (0.86–1.77) | 0.263 |

| CT/IO Cycles (median) | 0.79 (0.64–0.97) | 0.026 | 0.79 (0.64–0.99) | 0.035 |

| Characteristics at Diagnosis |

cTRT group (n=46) |

Non-cTRT group (n=162) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 66 (range 61-70) | 66 (range 61-69) | 0.834 |

| Age ≥ 65 years (%) | 56.5 | 54.9 | 0.849 |

| Male Sex (%) | 56.5 | 55.6 | 0.907 |

| ECOG PS 0 -1 (%) | 80.4 | 72.8 | 0.459 |

| Brain Metastasis (%) | 19.6 | 19.8 | 0.977 |

| Liver Metastasis (%) | 13.0 | 52.5 | <0.001 |

| Bone Metastasis (%) | 21.7 | 37.7 | 0.045 |

| Patients with ≥ 3 Metastatic sites (%) |

19.6 | 38.9 | 0.015 |

| Median LDH | 3.81 (95%CI 3.50;4.29) |

4.67 (95%CI4.12;5.37) |

0.005 |

| Patients with elevated LDH (%) |

41.3 | 56.8 | 0.063 |

| Median No. Of CT/IO Cycles (n) |

5 (range 4-5) | 4 (range 4-4) | 0.049 |

| Median No. Of Maintenance IO cycles (n) |

5.5 (range 2-9) | 2 (range 1-4) | <0.001 |

| Intrathoracic +/- systemic Progression (%) |

65.9 | 35.5 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).