Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

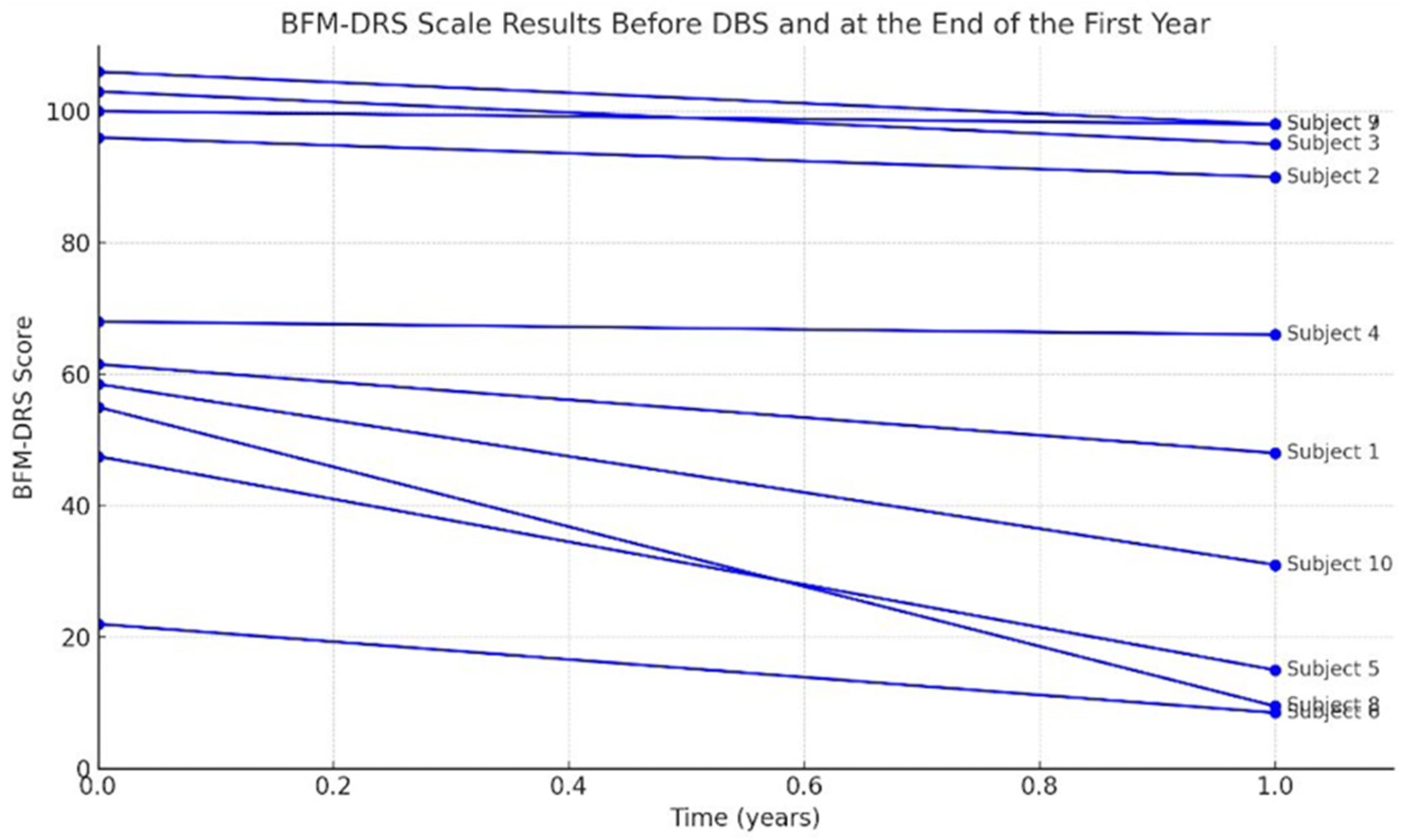

- Burke-Fahn-Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale (BFM-DRS): Evaluates dystonia severity through a movement subscore and a disability subscore, which are summed to a total score. Higher BFM-DRS scores indicate more severe dystonia and more significant functional impairment. This scale was administered preoperatively and at follow-up to quantify changes in dystonia severity [12].

- Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS): Classifies gross motor function on a five-level ordinal scale from Level I (walking without limitations) to Level V (severe limitations in head/trunk control, requiring wheelchair mobility). A lower GMFCS level denotes better motor function. Each patient’s GMFCS level was recorded at baseline and 1-year post-DBS to assess overall motor function classification changes [13].

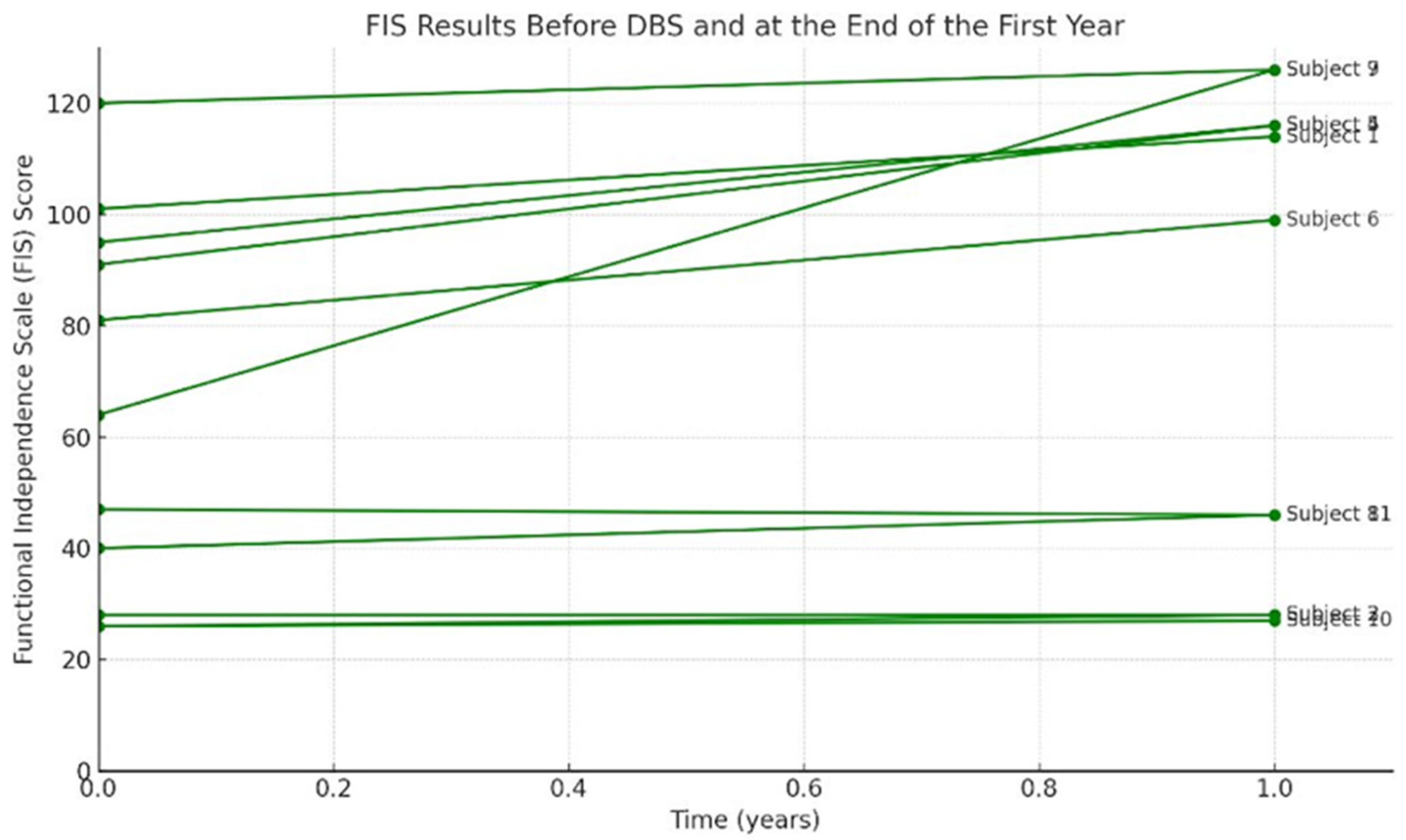

- Functional Independence Measure (FIM): Assesses patient’s ability to independently perform activities of daily living across multiple domains (self-care, mobility, communication, etc.) For each domain, a score is assigned based on the level of assistance needed, with total functional independence calculated by summing scores. Higher FIM scores imply higher independence (the highest score of 126 means independent). The FIM was given preoperatively and at 1 year to assess the changes in daily functional status [14].

- Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS): A 22-item questionnaire measuring the perceived burden on caregivers of chronically disabled individuals. Total CBS scores range from 0 to 95, with higher scores indicating more significant caregiver stress/burden. (For context, scores 0–20 reflect little to no burden, 21–40 mild-to-moderate burden, 41–60 moderate-to-severe burden, and above 60 severe burden.) Caregivers (usually a parent or family member) completed the CBS before surgery and at the 1-year follow-up to assess any change in caregiver-reported burden [15].

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Outcomes at 1-Year Post-DBS Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, S.A., et al., Evolving understanding of CP phenotypes: the importance of dystonia. Pediatr Res, 2024.

- Loutou, A., et al., Social support, depression, and quality of life among parents of children with cerebral palsy in Benin, West Africa: a cross-sectional case-control study. Int J Rehabil Res, 2025.

- Kondekar, A., Q. Ansari, and H. Ghatol, The quality of life of primary caretakers of children with cerebral palsy. J Family Med Prim Care, 2024. 13(10): p. 4457-4461.

- Ozkan, Y., Child’s quality of life and mother’s burden in spastic cerebral palsy: a topographical classification perspective. J Int Med Res, 2018. 46(8): p. 3131-3137.

- Lumsden, D.E., et al., Pharmacological management of abnormal tone and movement in cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child, 2019. 104(8): p. 775-780.

- Li, S., et al., Management Approaches to Spastic Gait Disorders. Muscle Nerve, 2025.

- Vitrikas, K., H. Dalton, and D. Breish, Cerebral Palsy: An Overview. Am Fam Physician, 2020. 101(4): p. 213-220.

- Aisen, M.L., et al., Cerebral palsy: clinical care and neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol, 2011. 10(9): p. 844-52.

- Bronte-Stewart, H., et al., Inclusion and exclusion criteria for DBS in dystonia. Mov Disord, 2011. 26 Suppl 1: p. S5-16.

- Elia, A.E., et al., Deep brain stimulation for dystonia due to cerebral palsy: A review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2018. 22(2): p. 308-315.

- Bohn, E., et al., Pharmacological and neurosurgical interventions for individuals with cerebral palsy and dystonia: a systematic review update and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2021. 63(9): p. 1038-1050.

- Burke, R.E., et al., Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias. Neurology, 1985. 35(1): p. 73-7.

- Morris, C. and D. Bartlett, Gross Motor Function Classification System: impact and utility. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2004. 46(1): p. 60-5.

- Kidd, D., et al., The Functional Independence Measure: a comparative validity and reliability study. Disabil Rehabil, 1995. 17(1): p. 10-4.

- Teriö, M., et al., Preventing frailty with the support of a home-monitoring and communication platform among older adults-a study protocol for a randomised-controlled pilot study in Sweden. Pilot Feasibility Stud, 2022. 8(1): p. 190.

- Vidailhet, M., et al., Bilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation for the treatment of patients with dystonia-choreoathetosis cerebral palsy: a prospective pilot study. Lancet Neurol, 2009. 8(8): p. 709-17.

- Koy, A., et al., Effects of deep brain stimulation in dyskinetic cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Mov Disord, 2013. 28(5): p. 647-54.

- Poulen, G., et al., Deep Brain Stimulation and Hypoxemic Perinatal Encephalopathy: State of Art and Perspectives. Life (Basel), 2021. 11(6).

- Cif, L., Deep brain stimulation in dystonic cerebral palsy: for whom and for what? Eur J Neurol, 2015. 22(3): p. 423-5.

- Lin, J.P., et al., The impact and prognosis for dystonia in childhood including dystonic cerebral palsy: a clinical and demographic tertiary cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2014. 85(11): p. 1239-44.

- San Luciano, M., et al., Thalamic deep brain stimulation for acquired dystonia in children and young adults: a phase 1 clinical trial. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2021. 27(2): p. 203-212.

|

Patient No |

Sex | Age during op | Age | CP clinical type | CP involvement pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 21 | 23 | chorea-atetoid, dystonic | Quadriplegia |

| 2 | F | 21 | 23 | mix | Quadriplegia |

| 3 | F | 19 | 21 | chorea-atetoid, dystonic | Quadriplegia |

| 4 | M | 55 | 59 | dyskinetic | Quadriplegia |

| 5 | M | 33 | 37 | mix | Diplegia |

| 6 | F | 34 | 39 | mix | Diplegia |

| 7 | F | 32 | 39 | mix | Quadriplegia |

| 8 | M | 7 | 16 | mix | Quadriplegia |

| 9 | F | 21 | 38 | dystonic | Quadriplegia |

| 10 | F | 6 | 9 | dystonic | Quadriplegia |

| 11 | F | 22 | 28 | mix | Quadriplegia |

| Patient No | CP-Clinical Type | BFMDRS preop | BFMDRS postop 1 year | Improvement (%) |

FIS preop | FIS postop | Improvement (%) |

GMFCS preop | GMFCS postop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chorea-atetoid, dystonic | 61,5 | 48 |

21.9 |

101 | 114 |

11.4 |

2 | 1 |

| 2 | mix | 96 | 90 | 6.25 | 26 | 28 | 7.1 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | chorea-atetoid, dystonic | 103 | 95 |

7.7 |

28 | 28 |

0 |

5 | 5 |

| 4 | dyskinetic | 68 | 66 | 2.9 | 91 | 116 | 24.1 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | mix | 47,5 | 39 | 17.8 | 95 | 116 | 18.1 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | mix | 48,5 | 15 | 69 | 81 | 99 | 18.1 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | mix | 22 | 8,5 | 60 | 120 | 126 | 4.7 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | mix | 100 | 98 | 2 | 47 | 46 | -2.1 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | dystonic | 55 | 9,5 | 82.7 | 64 | 126 | 49.2 | 3 | 1 |

| 10 | dystonic | 106 | 98 | 7.5 | 26 | 27 | 3.7 | 5 | 5 |

| 11 | mix | 58,5 | 31 | 47 | 40 | 46 | 13 | 4 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).