Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. The Challenge of Efficiency in Reasoning Models

- Computational Efficiency: The ability to perform reasoning with minimal processing time and hardware requirements. Many reasoning models, especially those relying on autoregressive decoding, incur high latency and energy costs.

- Data Efficiency: Effective reasoning with limited labeled data, which is essential in domains where annotated reasoning chains are expensive or difficult to acquire.

- Architectural Efficiency: Model design choices that promote modularity, reusability, and parallelization. This includes innovations such as sparse attention, retrieval-augmented generation, and lightweight compositional modules.

- Inference Efficiency: The ability to apply reasoning models effectively at test time without extensive prompting, multi-step querying, or human-in-the-loop corrections [4].

1.3. Scope and Contributions

- 1.

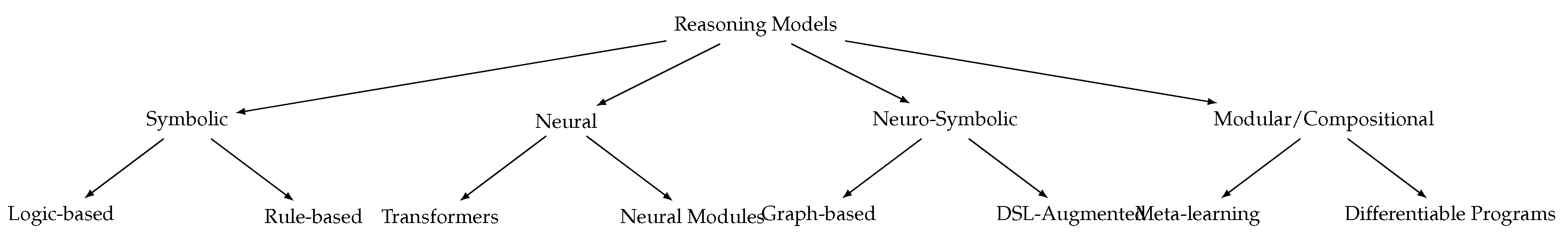

- Taxonomy of Reasoning Approaches: We provide a structured taxonomy of reasoning methodologies, including symbolic, neural, neuro-symbolic, and hybrid models, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations in terms of efficiency [7].

- 2.

- Comprehensive Literature Review: We analyze over 150 research papers spanning the last decade, with a special focus on recent developments from 2020 onwards [8]. We categorize works by reasoning type, architecture, and optimization strategies.

- 3.

- Efficiency-Oriented Benchmarking: We survey existing datasets and benchmarks used to evaluate reasoning capabilities, with a focus on those that measure or enforce efficiency constraints [9].

- 4.

- Open Challenges and Future Directions: We identify unresolved problems in the field, such as generalization under limited supervision, integrating symbolic priors with neural architectures, and scaling down reasoning models for real-time use.

1.4. Organization of the Survey

- Section 2 provides background on types of reasoning and theoretical foundations [10].

- Section 3 introduces a taxonomy of efficient reasoning models.

- Section 4 surveys architectural and algorithmic approaches to efficient reasoning [11].

- Section 5 explores datasets and evaluation metrics [12].

- Section 6 presents a comparative analysis and highlights empirical trade-offs.

- Section 7 discusses open challenges and future research directions [13].

- Section 8 concludes the paper [13].

1.5. Why Now?

- The rise of LLMs has renewed interest in general-purpose reasoning systems [14].

- Efficiency has become a pressing concern amid growing environmental and economic costs of AI deployment [15].

- Research communities in NLP, computer vision, and multi-agent systems are increasingly emphasizing explainability, fairness, and safety—goals that intersect with efficient and interpretable reasoning [16].

2. Background on Reasoning in Artificial Intelligence

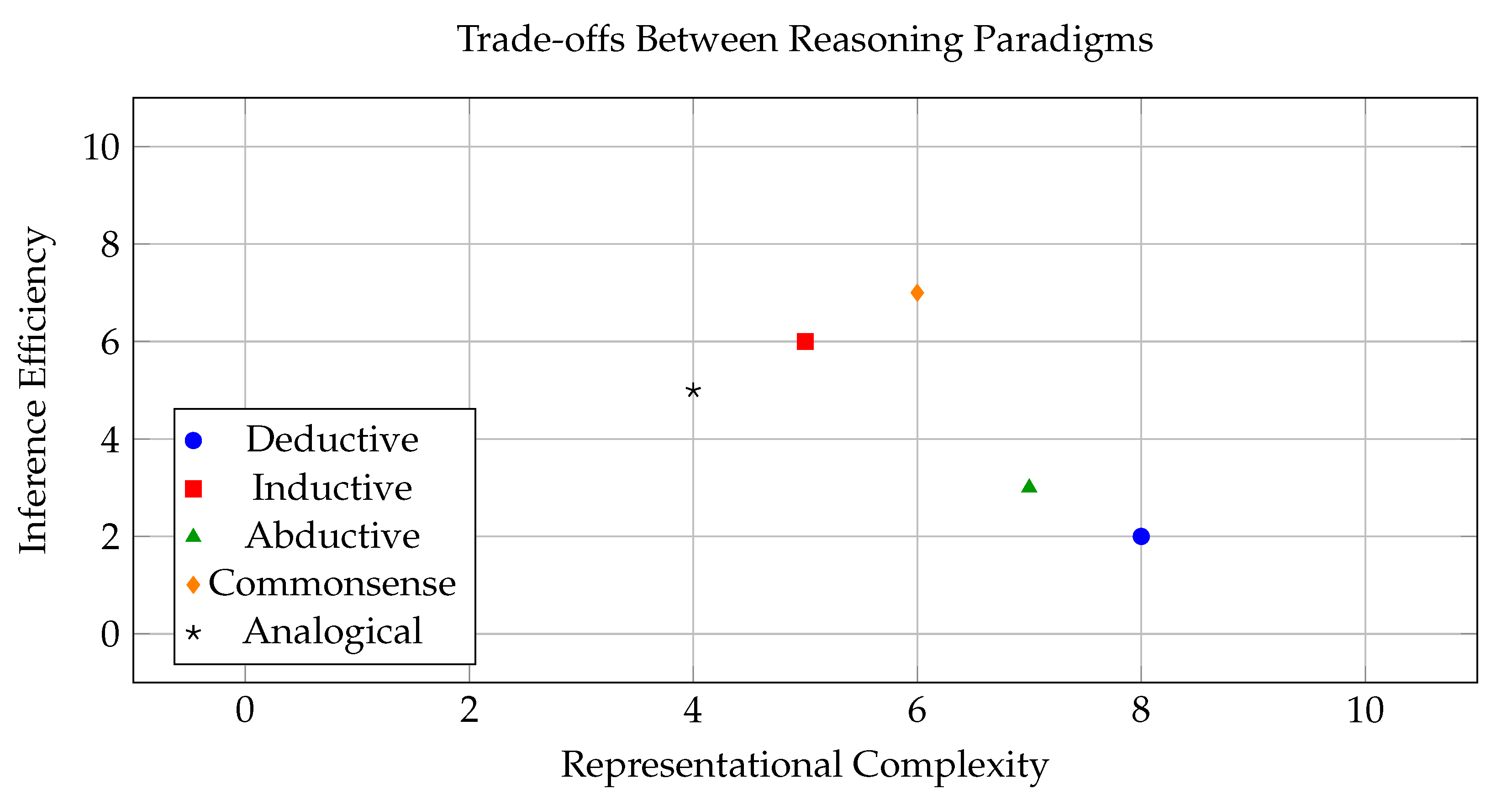

- Deductive reasoning: Drawing logically necessary conclusions from known premises. Typical in formal logic, programming languages, and knowledge bases.

- Inductive reasoning: Inferring general rules from specific observations. Common in statistical learning and generalization tasks.

- Abductive reasoning: Generating the most plausible explanation for a given observation [25]. Used in diagnostic systems and causal inference.

- Commonsense reasoning: Leveraging implicit world knowledge to make plausible inferences in everyday contexts [26].

- Analogical reasoning: Mapping structural relationships between domains to transfer knowledge or understanding [27].

3. Taxonomy of Efficient Reasoning Models

3.1. Symbolic Reasoning Models

3.2. Neural Reasoning Models

3.3. Neuro-Symbolic Models

3.4. Modular and Compositional Reasoning Models

3.5. Training Paradigms and Data Efficiency

3.6. Summary of Taxonomy

4. Architectural and Algorithmic Approaches to Efficient Reasoning

4.1. Representation and Encoding Strategies

4.2. Efficient Inference Mechanisms

4.3. Memory-Augmented Reasoning

4.4. Compositionality and Function Reuse

4.5. Learning Algorithms for Efficient Generalization

4.6. Visualization of Efficiency Improvements

4.7. Discussion

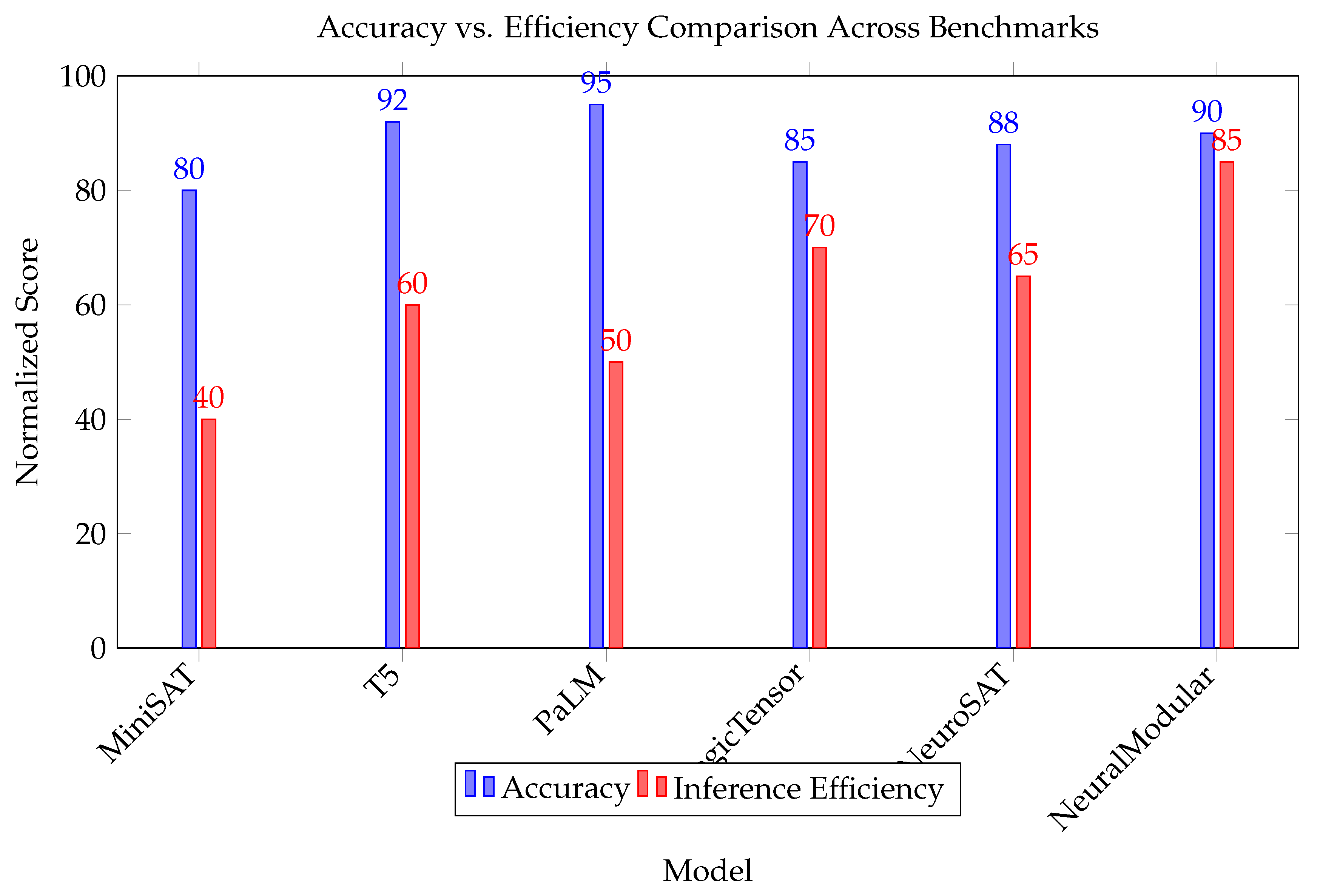

5. Empirical Evaluation and Benchmarking

5.1. Evaluation Criteria

- Inference Time: The average time taken to generate a solution per instance, measured in milliseconds or FLOPs.

- Accuracy: The correctness of the output, typically measured via exact match or F1 score depending on task granularity [73].

- Generalization: The model’s ability to handle novel combinations or reasoning chains not seen during training [74].

- Data Efficiency: The amount of labeled data required to reach a given accuracy level [65].

- Memory Usage: Peak memory consumption during training and inference.

5.2. Benchmark Datasets

5.3. Model Comparison and Results

5.4. Ablation Studies and Analysis

5.5. Discussion

6. Emerging Trends and Future Directions

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- W. Zeng, Y. Huang, Q. Liu, W. Liu, K. He, Z. Ma, J. He, Simplerl-zoo: Investigating and taming zero reinforcement learning for open base models in the wild, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.18892 (2025).

- Y. Li, P. Yuan, S. Feng, B. Pan, X. Wang, B. Sun, H. Wang, K. Li, Escape sky-high cost: Early-stopping self-consistency for multi-step reasoning, in: ICLR, 2024.

- R. Pan, Y. Dai, Z. Zhang, G. Oliaro, Z. Jia, R. Netravali, Specreason: Fast and accurate inference-time compute via speculative reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.07891 (2025).

- A. Hurst, A. Lerer, A. P. Goucher, A. Perelman, A. Ramesh, A. Clark, A. Ostrow, A. Welihinda, A. Hayes, A. Radford, et al., Gpt-4o system card, arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21276 (2024).

- O. AI., Introducing openai o1-preview (2024).

- J. Hao, Y. Zhu, T. Wang, J. Yu, X. Xin, B. Zheng, Z. Ren, S. Guo, Omnikv: Dynamic context selection for efficient long-context llms, in: The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- J. Duan, S. Yu, H. L. Tan, H. Zhu, C. Tan, A survey of embodied ai: From simulators to research tasks, IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 6 (2) (2022) 230–244.

- E. Yang, L. Shen, G. Guo, X. Wang, X. Cao, J. Zhang, D. Tao, Model merging in llms, mllms, and beyond: Methods, theories, applications and opportunities, arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.07666 (2024).

- H. Luo, L. Shen, H. He, Y. Wang, S. Liu, W. Li, N. Tan, X. Cao, D. Tao, O1-pruner: Length-harmonizing fine-tuning for o1-like reasoning pruning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12570 (2025).

- Y. Shen, J. Zhang, J. Huang, S. Shi, W. Zhang, J. Yan, N. Wang, K. Wang, S. Lian, Dast: Difficulty-adaptive slow-thinking for large reasoning models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.04472 (2025).

- A. Taubenfeld, T. Sheffer, E. Ofek, A. Feder, A. Goldstein, Z. Gekhman, G. Yona, Confidence improves self-consistency in llms, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06233 (2025).

- Y. Wu, Y. Wang, T. Du, S. Jegelka, Y. Wang, When more is less: Understanding chain-of-thought length in llms, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.07266 (2025).

- Y. Li, X. Yue, Z. Xu, F. Jiang, L. Niu, B. Y. Lin, B. Ramasubramanian, R. Poovendran, Small models struggle to learn from strong reasoners, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12143 (2025).

- I. Ong, A. Almahairi, V. Wu, W.-L. Chiang, T. Wu, J. E. Gonzalez, M. W. Kadous, I. Stoica, Routellm: Learning to route llms with preference data (2025). arXiv:2406.18665.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18665.

- H. Xia, Y. Li, C. T. Leong, W. Wang, W. Li, Tokenskip: Controllable chain-of-thought compression in llms, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12067 (2025).

- X. Chen, J. Xu, T. Liang, Z. He, J. Pang, D. Yu, L. Song, Q. Liu, M. Zhou, Z. Zhang, et al., Do not think that much for 2+ 3=? on the overthinking of o1-like llms, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.21187 (2024).

- Z. Shao, P. Wang, Q. Zhu, R. Xu, J. Song, X. Bi, H. Zhang, M. Zhang, Y. Li, Y. Wu, et al., Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300 (2024).

- S. J. Qin, T. A. Badgwell, An overview of industrial model predictive control technology, in: AIche symposium series, 1997.

- Z. Yu, Y. Wu, Y. Zhao, A. Cohan, X.-P. Zhang, Z1: Efficient test-time scaling with code (2025). arXiv:2504.00810.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.00810.

- M. Jin, W. Luo, S. Cheng, X. Wang, W. Hua, R. Tang, W. Y. Wang, Y. Zhang, Disentangling memory and reasoning ability in large language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.13504 (2024).

- M. Tomar, L. Shani, Y. Efroni, M. Ghavamzadeh, Mirror descent policy optimization, arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09814 (2020).

- P. Henderson, J. Hu, J. Romoff, E. Brunskill, D. Jurafsky, J. Pineau, Towards the systematic reporting of the energy and carbon footprints of machine learning, Journal of Machine Learning Research 21 (248) (2020) 1–43.

- Y. Zniyed, T. P. Nguyen, et al., Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning, Neural Networks 178 (2024) 106393.

- R. Ding, C. Zhang, L. Wang, Y. Xu, M. Ma, W. Zhang, S. Qin, S. Rajmohan, Q. Lin, D. Zhang, Everything of thoughts: Defying the law of penrose triangle for thought generation, arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.04254 (2023).

- Y. Wang, P. Zhang, S. Huang, B. Yang, Z. Zhang, F. Huang, R. Wang, Sampling-efficient test-time scaling: Self-estimating the best-of-n sampling in early decoding, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.01422 (2025).

- S. A. Aytes, J. Baek, S. J. Hwang, Sketch-of-thought: Efficient llm reasoning with adaptive cognitive-inspired sketching, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05179 (2025).

- H. Wu, Y. Yao, S. Liu, Z. Liu, X. Fu, X. Han, X. Li, H.-L. Zhen, T. Zhong, M. Yuan, Unlocking efficient long-to-short llm reasoning with model merging, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20641 (2025).

- J. Zhang, Y. Zhu, M. Sun, Y. Luo, S. Qiao, L. Du, D. Zheng, H. Chen, N. Zhang, Lightthinker: Thinking step-by-step compression, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.15589 (2025).

- K. Team, A. Du, B. Gao, B. Xing, C. Jiang, C. Chen, C. Li, C. Xiao, C. Du, C. Liao, et al., Kimi k1. 5: Scaling reinforcement learning with llms, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12599 (2025).

- A. Grattafiori, A. Dubey, A. Jauhri, A. Pandey, A. Kadian, A. Al-Dahle, A. Letman, A. Mathur, A. Schelten, A. Vaughan, et al., The llama 3 herd of models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783 (2024).

- Y. Meng, M. Xia, D. Chen, Simpo: Simple preference optimization with a reference-free reward, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (2024) 124198–124235.

- Z. Yang, P. Qi, S. Zhang, Y. Bengio, W. W. Cohen, R. Salakhutdinov, C. D. Manning, Hotpotqa: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering, arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.09600 (2018).

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, F. Xia, E. Chi, Q. V. Le, D. Zhou, et al., Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models, Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022) 24824–24837.

- X. Wang, L. Caccia, O. Ostapenko, X. Yuan, W. Y. Wang, A. Sordoni, Guiding language model reasoning with planning tokens, in: COLM, 2024.

- H. Lightman, V. Kosaraju, Y. Burda, H. Edwards, B. Baker, T. Lee, J. Leike, J. Schulman, I. Sutskever, K. Cobbe, Let’s verify step by step, in: The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Y. Deng, Y. Choi, S. Shieber, From explicit cot to implicit cot: Learning to internalize cot step by step, arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14838 (2024).

- F. Liu, W. Chao, N. Tan, H. Liu, Bag of tricks for inference-time computation of llm reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.07191 (2025).

- C. Lee, A. M. Rush, K. Vafa, Critical thinking: Which kinds of complexity govern optimal reasoning length? (2025). arXiv:2504.01935.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.01935.

- L. Kocsis, C. Szepesvári, Bandit based monte-carlo planning, in: European conference on machine learning, Springer, 2006, pp. 282–293.

- Y. Li, L. Niu, X. Zhang, K. Liu, J. Zhu, Z. Kang, E-sparse: Boosting the large language model inference through entropy-based n: M sparsity, arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15929 (2023).

- T. Liu, Q. Guo, X. Hu, C. Jiayang, Y. Zhang, X. Qiu, Z. Zhang, Can language models learn to skip steps?, arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.01855 (2024).

- D. Su, H. Zhu, Y. Xu, J. Jiao, Y. Tian, Q. Zheng, Token assorted: Mixing latent and text tokens for improved language model reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.03275 (2025).

- F. Xu, Q. Hao, Z. Zong, J. Wang, Y. Zhang, J. Wang, X. Lan, J. Gong, T. Ouyang, F. Meng, et al., Towards large reasoning models: A survey of reinforced reasoning with large language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.09686 (2025).

- P. Gao, A. Xie, S. Mao, W. Wu, Y. Xia, H. Mi, F. Wei, Meta reasoning for large language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11698 (2024).

- T. Han, C. Fang, S. Zhao, S. Ma, Z. Chen, Z. Wang, Token-budget-aware llm reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.18547 (2024).

- R. Coulom, Efficient selectivity and backup operators in monte-carlo tree search, in: International conference on computers and games, Springer, 2006, pp. 72–83.

- Z. Shen, H. Yan, L. Zhang, Z. Hu, Y. Du, Y. He, Codi: Compressing chain-of-thought into continuous space via self-distillation, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.21074 (2025).

- A. Van Den Oord, O. Vinyals, et al., Neural discrete representation learning, Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- W. Chen, X. Ma, X. Wang, W. W. Cohen, Program of thoughts prompting: Disentangling computation from reasoning for numerical reasoning tasks, arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12588 (2022).

- Y.-N. Chuang, L. Yu, G. Wang, L. Zhang, Z. Liu, X. Cai, Y. Sui, V. Braverman, X. Hu, Confident or seek stronger: Exploring uncertainty-based on-device llm routing from benchmarking to generalization (2025). arXiv:2502.04428.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.04428.

- E. Beeching, L. Tunstall, S. Rush, Scaling test-time compute with open models.URL https://huggingface.co/spaces/HuggingFaceH4/blogpost-scaling-test-time-compute.

- Y. Wu, Z. Sun, S. Li, S. Welleck, Y. Yang, Inference scaling laws: An empirical analysis of compute-optimal inference for problem-solving with language models, in: ICLR, 2025.

- B. Liao, Y. Xu, H. Dong, J. Li, C. Monz, S. Savarese, D. Sahoo, C. Xiong, Reward-guided speculative decoding for efficient llm reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.19324 (2025).

- X. Zhu, J. Li, C. Ma, W. Wang, Improving mathematical reasoning capabilities of small language models via feedback-driven distillation, arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.14698 (2024).

- W. Yang, S. Ma, Y. Lin, F. Wei, Towards thinking-optimal scaling of test-time compute for llm reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18080 (2025).

- J. Light, W. Cheng, W. Yue, M. Oyamada, M. Wang, S. Paternain, H. Chen, Disc: Dynamic decomposition improves llm inference scaling, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.16706 (2025).

- D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Kadavath, A. Arora, S. Basart, E. Tang, D. Song, J. Steinhardt, Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset, in: Thirty-fifth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track, 2021.

- J. Pfau, W. Merrill, S. R. Bowman, Let’s think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15758 (2024).

- W. Wu, Z. Pan, C. Wang, L. Chen, Y. Bai, K. Fu, Z. Wang, H. Xiong, Tokenselect: Efficient long-context inference and length extrapolation for llms via dynamic token-level kv cache selection, arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02886 (2024).

- X. Chen, Z. Sun, W. Guo, M. Zhang, Y. Chen, Y. Sun, H. Su, Y. Pan, D. Klakow, W. Li, et al., Unveiling the key factors for distilling chain-of-thought reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18001 (2025).

- S. Eo, H. Moon, E. H. Zi, C. Park, H. Lim, Debate only when necessary: Adaptive multiagent collaboration for efficient llm reasoning (2025). arXiv:2504.05047.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.05047.

- H. Liao, S. He, Y. Hao, X. Li, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, K. Liu, Skintern: Internalizing symbolic knowledge for distilling better cot capabilities into small language models, in: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2025, pp. 3203–3221.

- C. Li, N. Liu, K. Yang, Adaptive group policy optimization: Towards stable training and token-efficient reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.15952 (2025).

- Y. Zniyed, T. P. Nguyen, et al., Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (2024).

- Y. Zhao, S. Zhou, H. Zhu, Probe then retrieve and reason: Distilling probing and reasoning capabilities into smaller language models, in: Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), 2024, pp. 13026–13032.

- J. Devlin, Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding, arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

- I. Ong, A. Almahairi, V. Wu, W.-L. Chiang, T. Wu, J. E. Gonzalez, M. W. Kadous, I. Stoica, Routellm: Learning to route llms with preference data, arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.18665 (2024).

- Y. Kang, X. Sun, L. Chen, W. Zou, C3ot: Generating shorter chain-of-thought without compromising effectiveness, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.11664 (2024).

- Y. LeCun, J. Denker, S. Solla, Optimal brain damage, Advances in neural information processing systems 2 (1989).

- G. Srivastava, S. Cao, X. Wang, Towards reasoning ability of small language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.11569 (2025).

- L. Wen, Y. Cai, F. Xiao, X. He, Q. An, Z. Duan, Y. Du, J. Liu, L. Tang, X. Lv, et al., Light-r1: Curriculum sft, dpo and rl for long cot from scratch and beyond, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.10460 (2025).

- S. Han, H. Mao, W. J. Dally, Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding, in: ICLR, 2016.

- D. Guo, D. Yang, H. Zhang, J. Song, R. Zhang, R. Xu, Q. Zhu, S. Ma, P. Wang, X. Bi, et al., Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948 (2025).

- W. Ling, D. Yogatama, C. Dyer, P. Blunsom, Program induction by rationale generation: Learning to solve and explain algebraic word problems, arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.04146 (2017).

- Z. Zhang, Y. Sheng, T. Zhou, T. Chen, L. Zheng, R. Cai, Z. Song, Y. Tian, C. Ré, C. Barrett, et al., H2o: Heavy-hitter oracle for efficient generative inference of large language models, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023) 34661–34710.

- M. Hu, Y. Mu, X. Yu, M. Ding, S. Wu, W. Shao, Q. Chen, B. Wang, Y. Qiao, P. Luo, Tree-planner: Efficient close-loop task planning with large language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.08582 (2023).

- S. Xing, H. Hua, X. Gao, S. Zhu, R. Li, K. Tian, X. Li, H. Huang, T. Yang, Z. Wang, et al., Autotrust: Benchmarking trustworthiness in large vision language models for autonomous driving, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.15206 (2024).

- P. Yu, J. Xu, J. Weston, I. Kulikov, Distilling system 2 into system 1, arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.06023 (2024).

- Codeforces, Codeforces - competitive programming platform, accessed: 2025-03-18 (2025).URL https://codeforces.com/.

- Z. Zhou, T. Yuhao, Z. Li, Y. Yao, L.-Z. Guo, X. Ma, Y.-F. Li, Bridging internal probability and self-consistency for effective and efficient llm reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.00511 (2025).

- B. Liu, X. Li, J. Zhang, J. Wang, T. He, S. Hong, H. Liu, S. Zhang, K. Song, K. Zhu, et al., Advances and challenges in foundation agents: From brain-inspired intelligence to evolutionary, collaborative, and safe systems, arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.01990 (2025).

- Y.-N. Chuang, L. Yu, G. Wang, L. Zhang, Z. Liu, X. Cai, Y. Sui, V. Braverman, X. Hu, Confident or seek stronger: Exploring uncertainty-based on-device llm routing from benchmarking to generalization, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04428 (2025).

- Y. Zhang, M. Khalifa, L. Logeswaran, J. Kim, M. Lee, H. Lee, L. Wang, Small language models need strong verifiers to self-correct reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.17140 (2024).

- M. Renze, E. Guven, The benefits of a concise chain of thought on problem-solving in large language models, in: 2024 2nd International Conference on Foundation and Large Language Models (FLLM), IEEE, 2024, pp. 476–483.

- A. Jaech, A. Kalai, A. Lerer, A. Richardson, A. El-Kishky, A. Low, A. Helyar, A. Madry, A. Beutel, A. Carney, et al., Openai o1 system card, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16720 (2024).

- Q. Yu, Z. Zhang, R. Zhu, Y. Yuan, X. Zuo, Y. Yue, T. Fan, G. Liu, L. Liu, X. Liu, et al., Dapo: An open-source llm reinforcement learning system at scale, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.14476 (2025).

- H. Sun, M. Haider, R. Zhang, H. Yang, J. Qiu, M. Yin, M. Wang, P. Bartlett, A. Zanette, Fast best-of-n decoding via speculative rejection, arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.20290 (2024).

- M. Luo, S. Tan, J. Wong, X. Shi, W. Y. Tang, M. Roongta, C. Cai, J. Luo, T. Zhang, L. E. Li, et al., Deepscaler: Surpassing o1-preview with a 1.5 b model by scaling rl, Notion Blog (2025).

- M. Song, M. Zheng, Z. Li, W. Yang, X. Luo, Y. Pan, F. Zhang, Fastcurl: Curriculum reinforcement learning with progressive context extension for efficient training r1-like reasoning models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.17287 (2025).

- Y. Sun, H. Bao, W. Wang, Z. Peng, L. Dong, S. Huang, J. Wang, F. Wei, Multimodal latent language modeling with next-token diffusion, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08635 (2024).

- C. Cui, Y. Ma, X. Cao, W. Ye, Y. Zhou, K. Liang, J. Chen, J. Lu, Z. Yang, K.-D. Liao, et al., A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 958–979.

- Y. Ye, Z. Huang, Y. Xiao, E. Chern, S. Xia, P. Liu, Limo: Less is more for reasoning (2025). arXiv:2502.03387.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03387.

- Z. Pan, H. Luo, M. Li, H. Liu, Chain-of-action: Faithful and multimodal question answering through large language models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.17359 (2024).

- N. Saunshi, N. Dikkala, Z. Li, S. Kumar, S. J. Reddi, Reasoning with latent thoughts: On the power of looped transformers, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.17416 (2025).

- Y. Chen, J. Shang, Z. Zhang, Y. Xie, J. Sheng, T. Liu, S. Wang, Y. Sun, H. Wu, H. Wang, Inner thinking transformer: Leveraging dynamic depth scaling to foster adaptive internal thinking, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13842 (2025).

- G. Hinton, O. Vinyals, J. Dean, Distilling the knowledge in a neural network, arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

| Reasoning Type | Typical Representation | Complexity | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deductive | Logic rules, proof trees | High (NP-Hard) | Precision, verifiability | Brittle to noise, domain-limited |

| Inductive | Feature vectors, datasets | Moderate | Generalization, learning from data | Overfitting, needs large datasets |

| Abductive | Hypothesis spaces, constraints | High | Explains observations, supports diagnostics | Often intractable, multiple solutions |

| Commonsense | Knowledge graphs, embeddings | Variable | Human-like plausibility, flexibility | Hard to formalize, data bias |

| Analogical | Structural mappings, graphs | Moderate | Cross-domain transfer, creativity | Ambiguity in mapping, evaluation unclear |

| Technique | Description | Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse Attention | Reduces attention computation by focusing on relevant tokens | Improves memory and compute usage |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Fetches context from external sources at runtime | Reduces reliance on internal memory, enhances generalization |

| Knowledge Distillation | Transfers reasoning ability from a large model to a smaller one | Reduces model size and inference cost |

| Prompt Engineering and Few-shot Tuning | Uses context formatting to elicit reasoning | Avoids task-specific training, low overhead |

| Neural Module Networks | Compositional neural units assigned to subtasks | Enables interpretability and reuse, but training is complex |

| Dataset | Domain | Reasoning Type | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| bAbI Tasks | Synthetic QA | Deductive, Temporal | Compositionality, Multi-hop |

| GSM8K | Arithmetic QA | Mathematical, Symbolic | Precision, Multi-step calculations |

| ARC Challenge | Commonsense Reasoning | Analogical, Conceptual | Novel task formats, Robustness |

| CLEVR | Visual QA | Spatial, Logical | Visual grounding, Scene manipulation |

| ProofWriter | Formal Logic | Deductive | Multi-step proof generation |

| OpenBookQA | Science QA | Commonsense, Retrieval | Knowledge transfer, Document retrieval |

| MiniWoB++ | Program Induction | Procedural, Symbolic | Action planning, Generalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).