Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

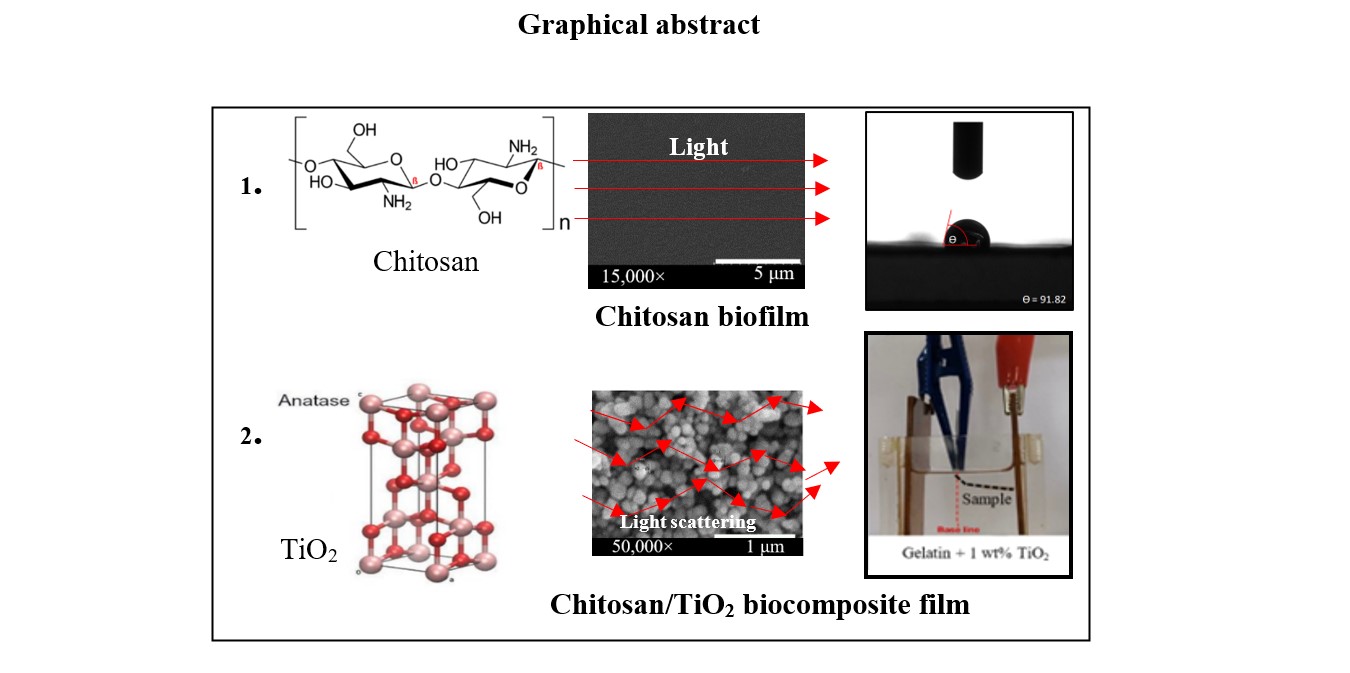

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

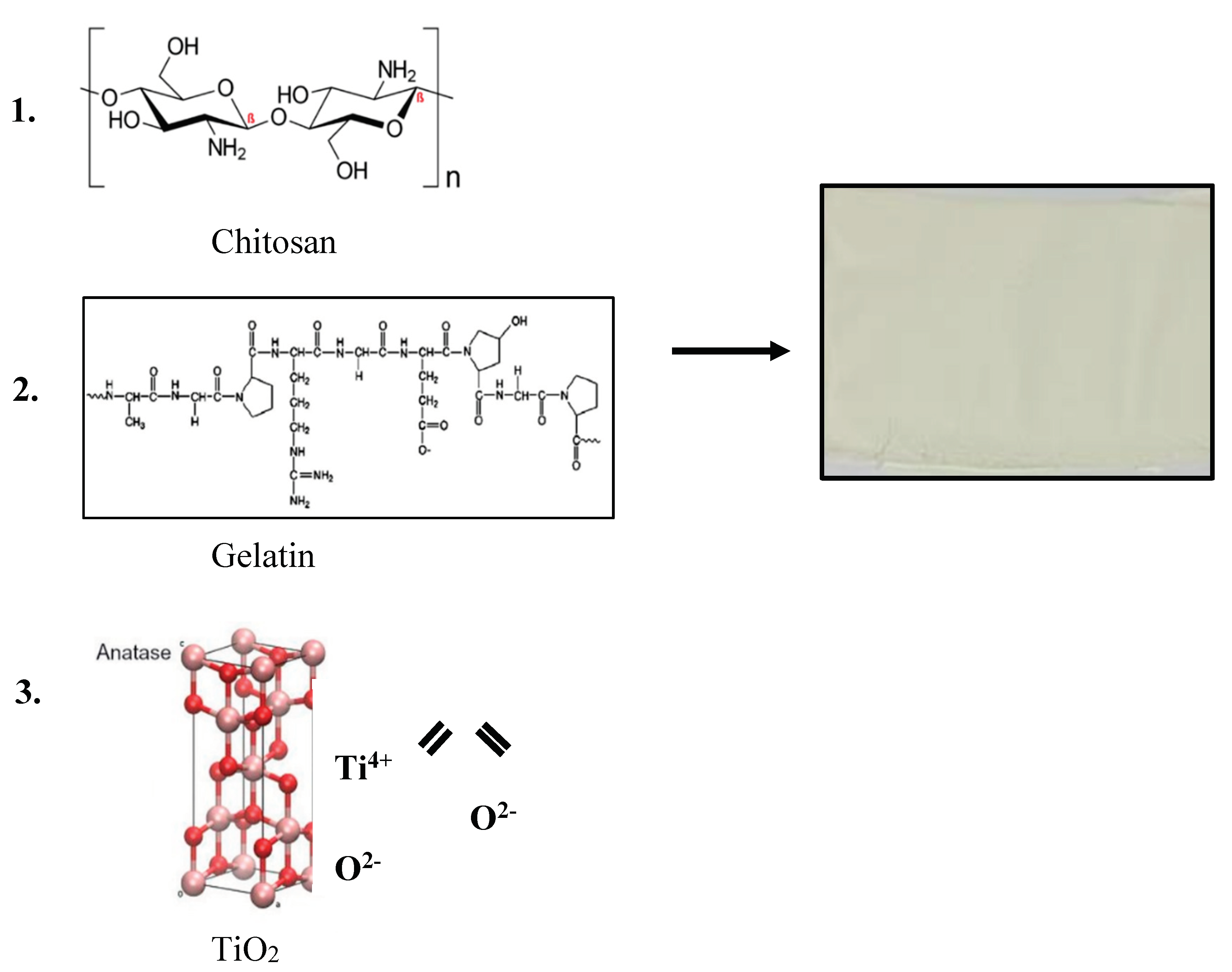

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Preparation of Bio-Chitosan Film Composites with and without Gelatin Powder and Titanium dioxide (TiO2) Filler for Hydrophobic, Hydrophilic, and Photoelectrical Conductivity Applications

2.4. Measurement of Crosslink Density in Bio-Chitosan Film Composites with Titanium Dioxide Filler for Hydrophobic, Hydrophilic, and Photoelectrical Conductivity Applications

3. Results and Discussion

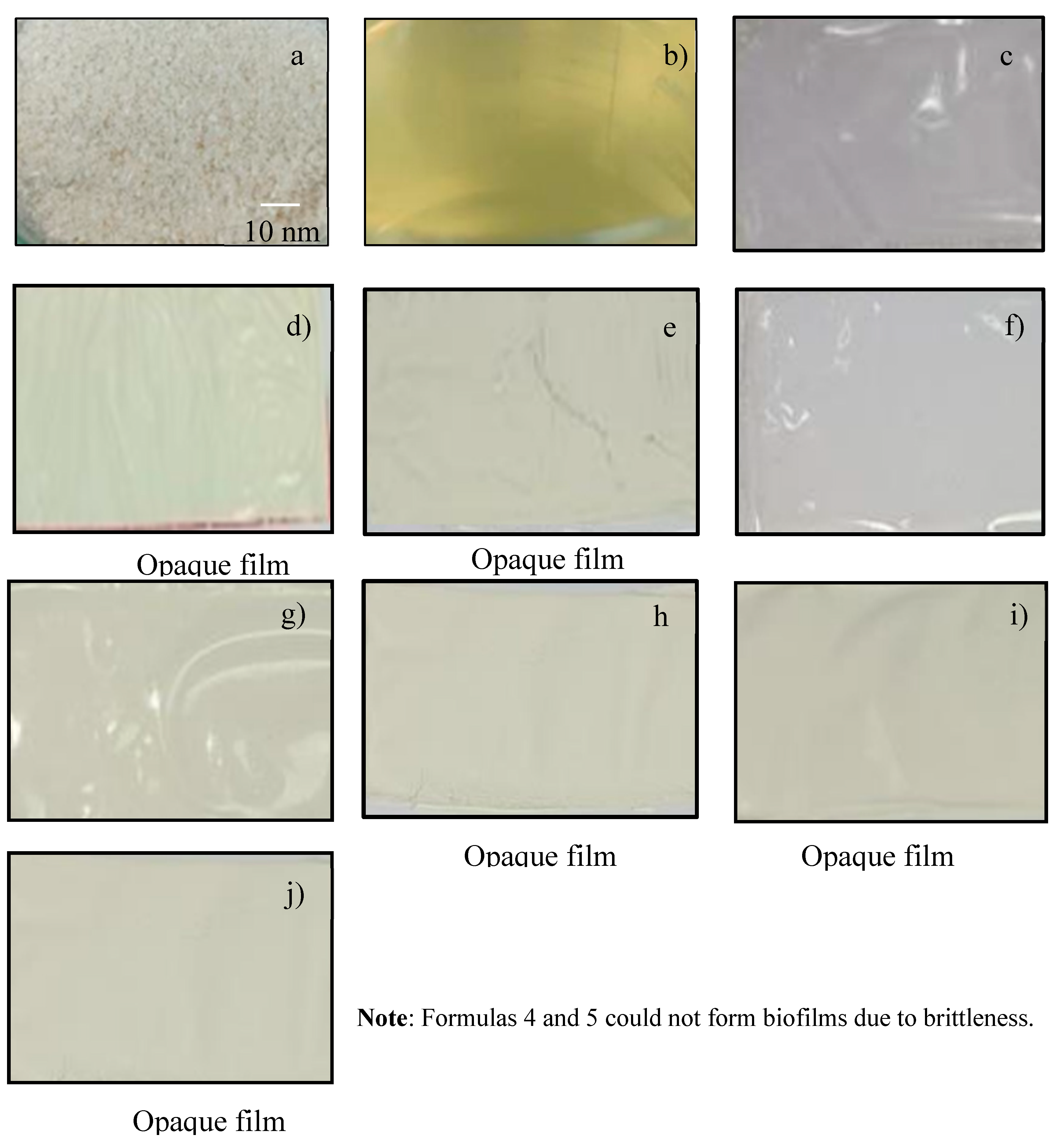

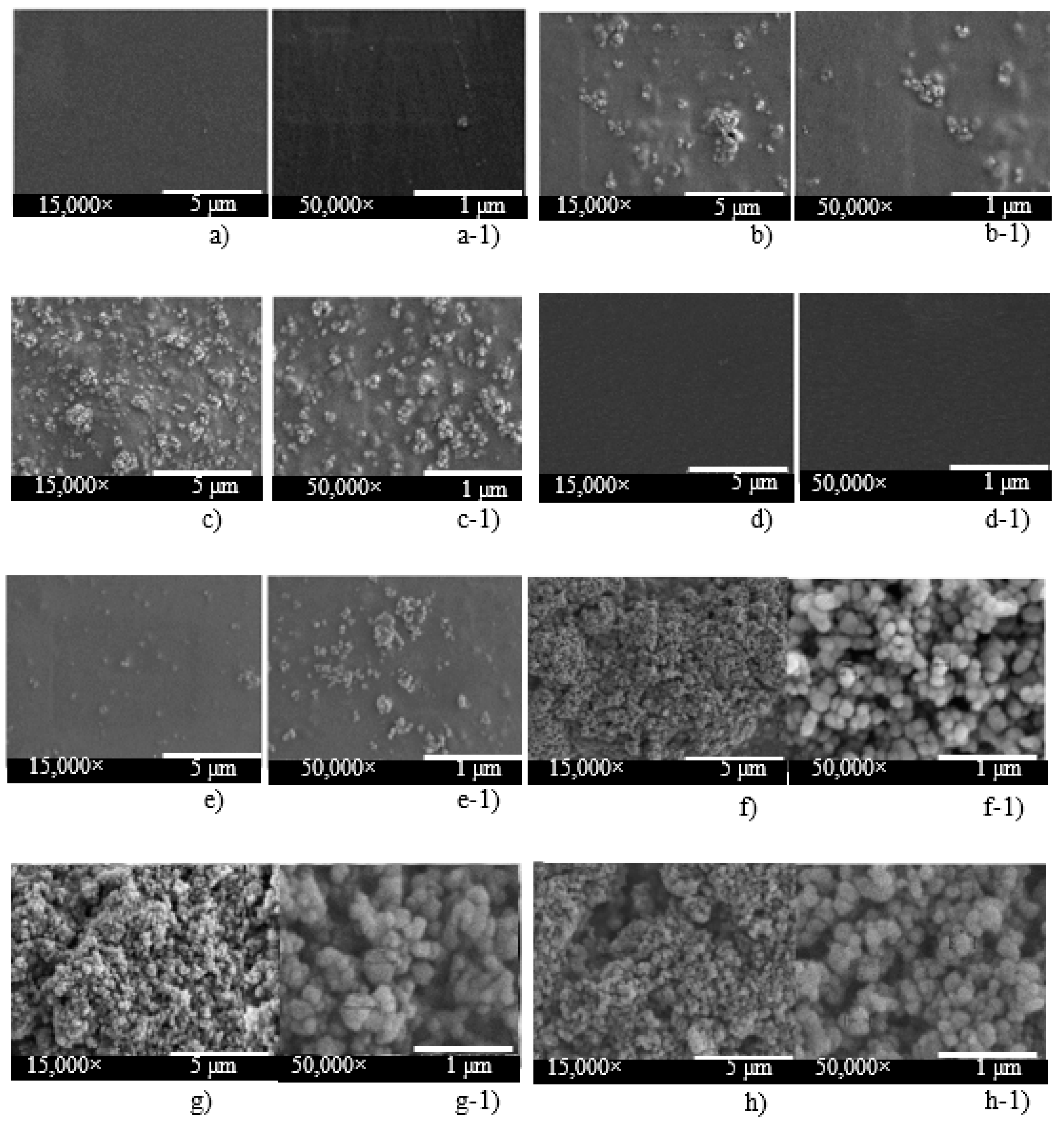

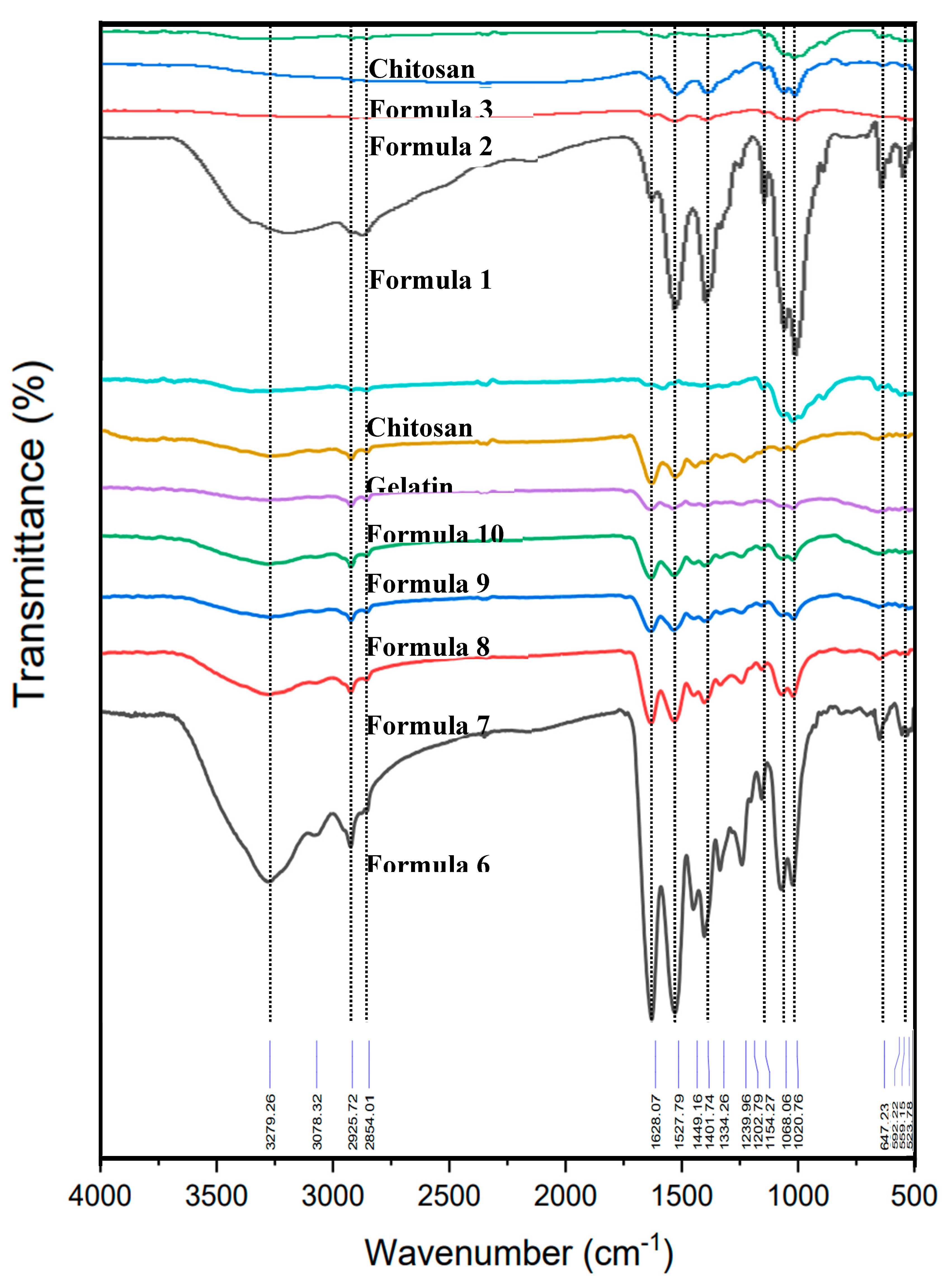

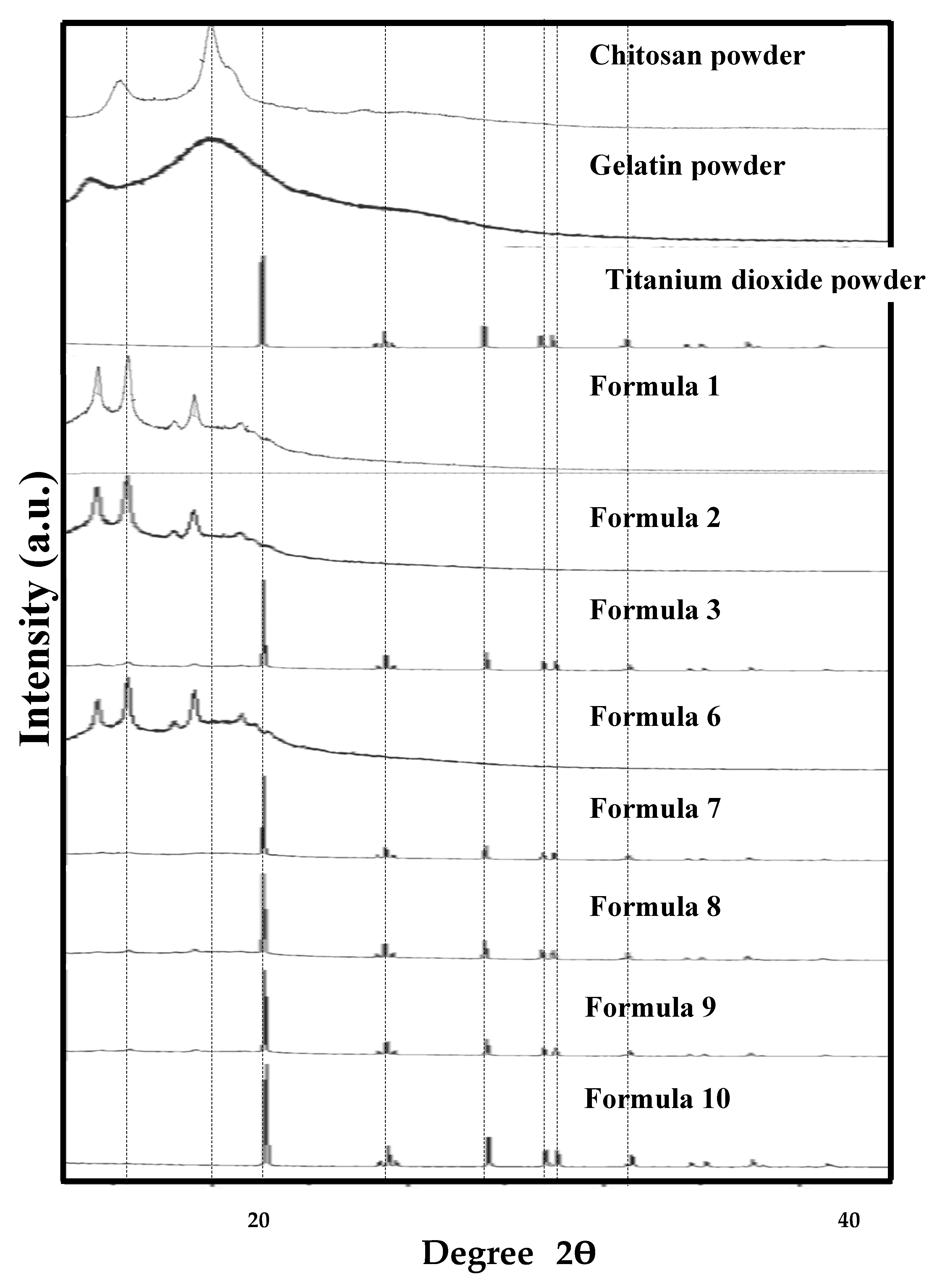

3.1. Characteristics and Physical Properties of Chitosan Powder Embedded with Titanium Dioxide for Preparing Bio-Chitosan Nanocomposite Films

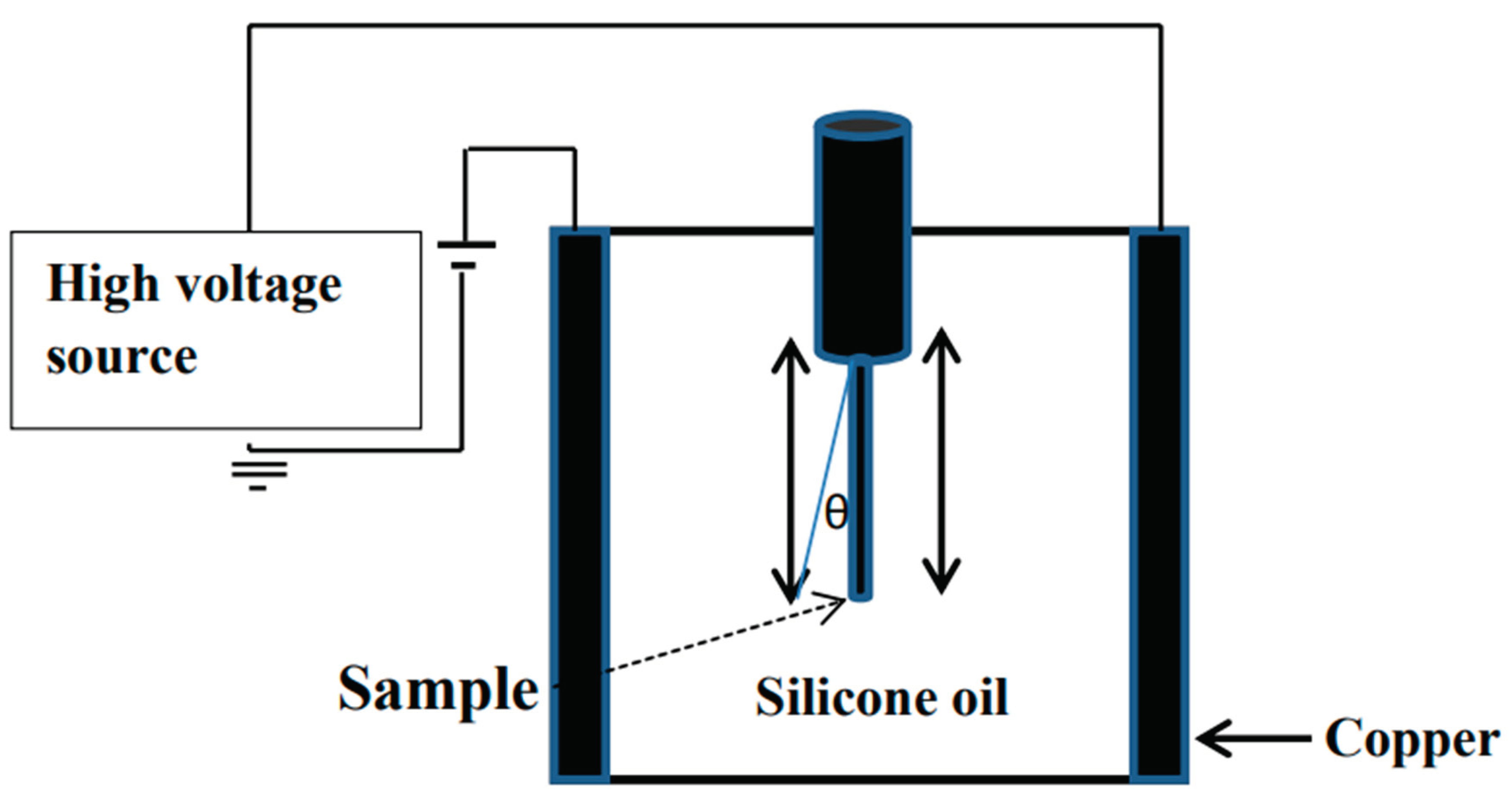

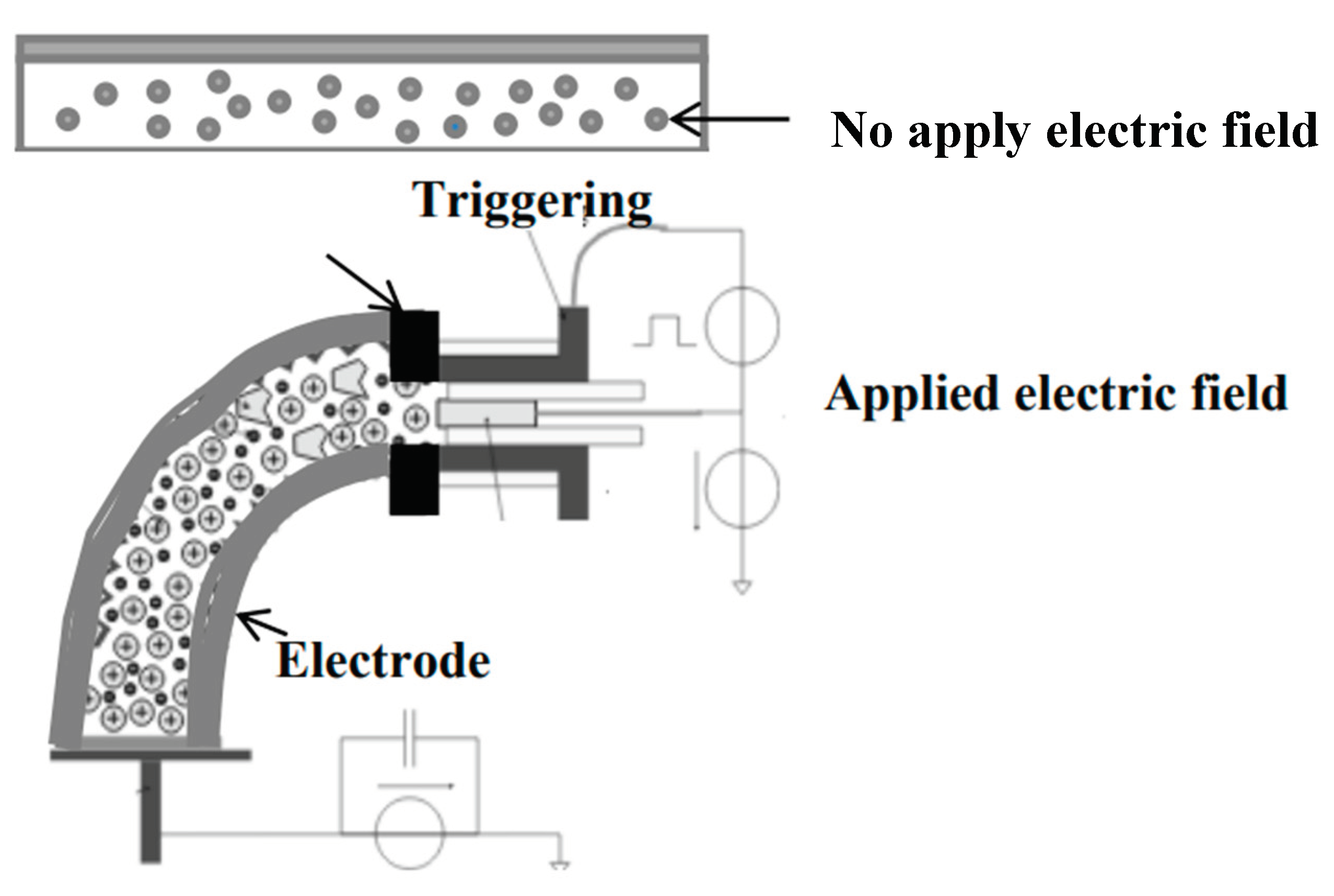

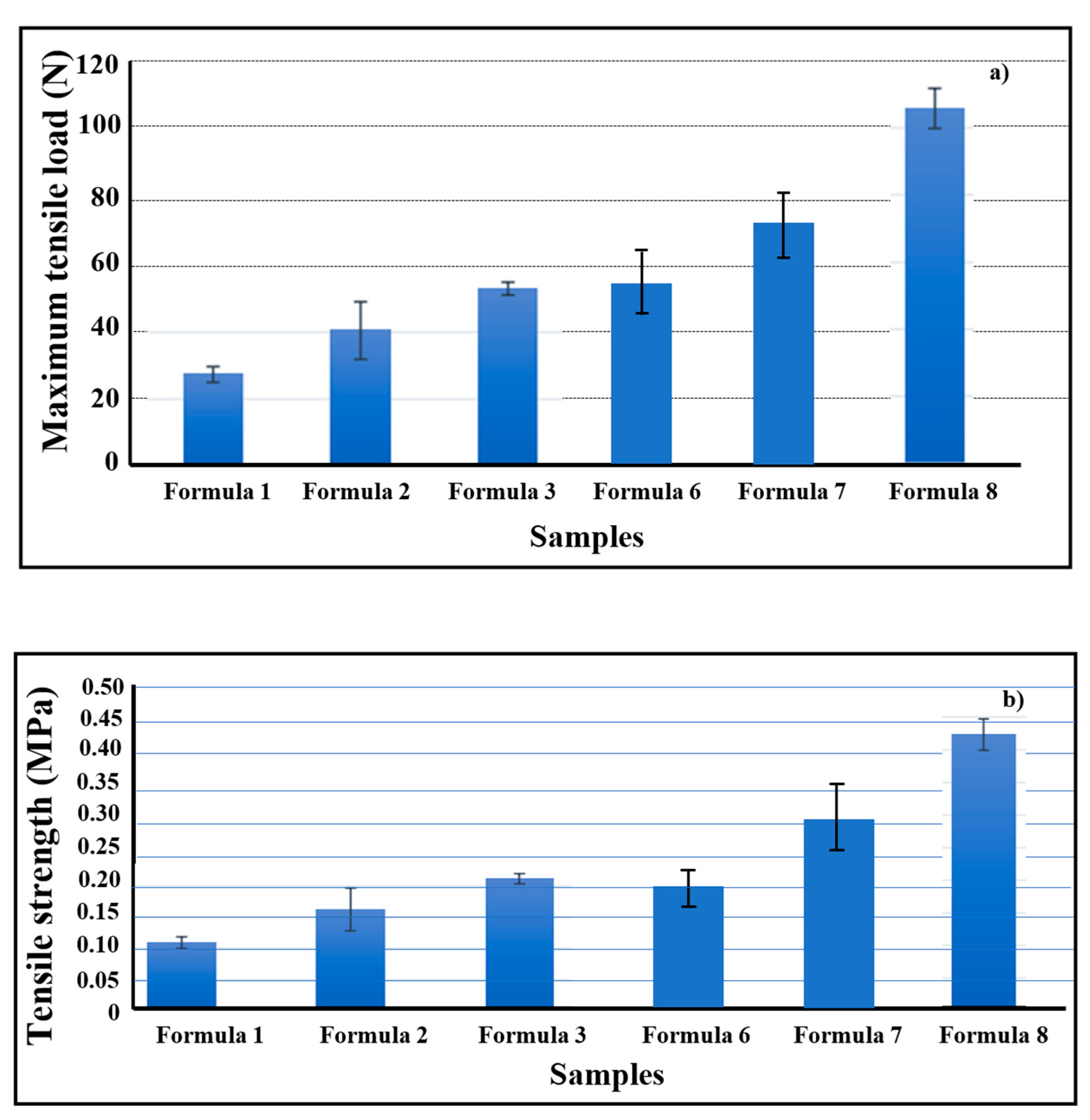

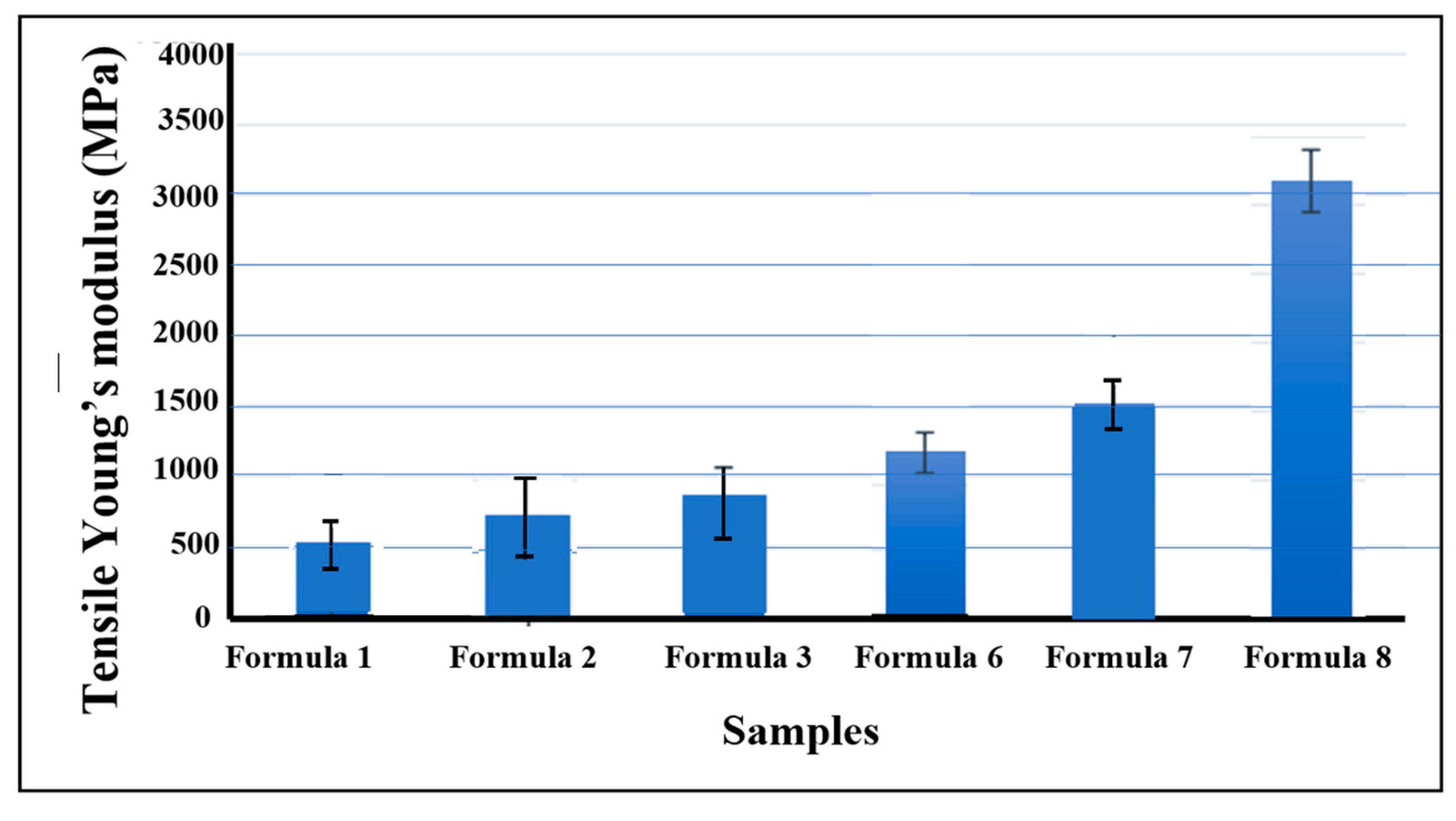

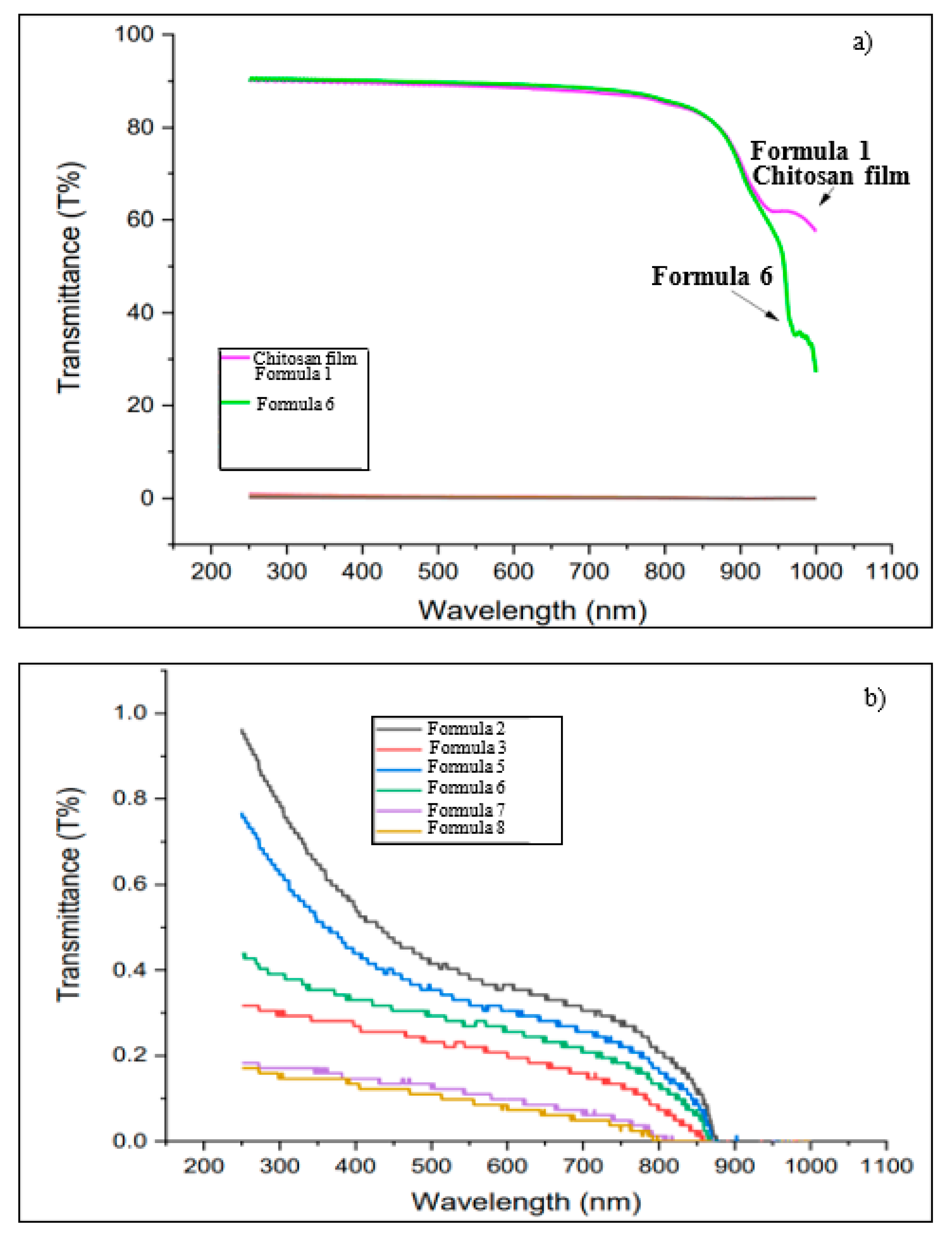

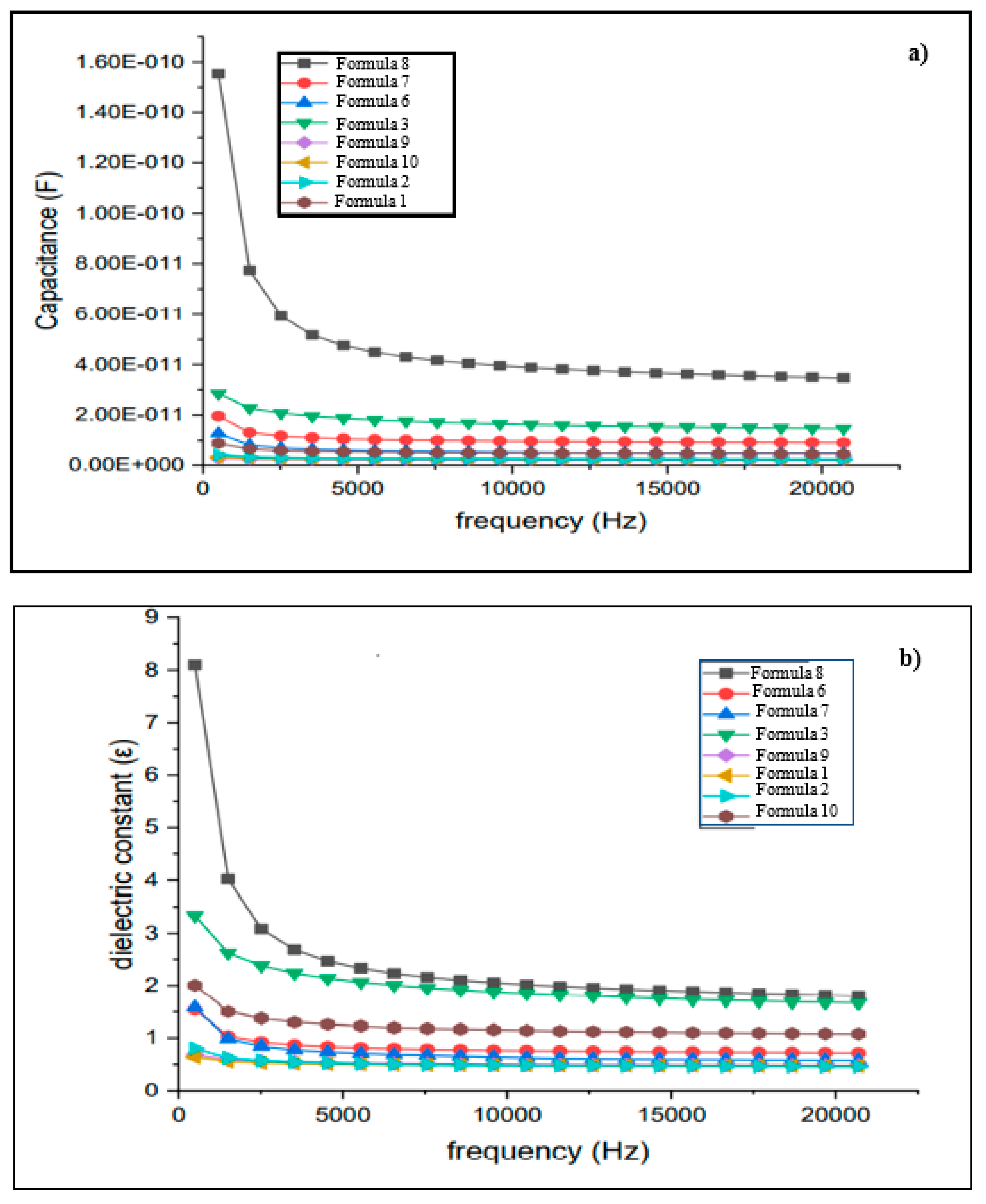

3.2. Mechanical, Optical, and Electrical Properties of Bio-chitosan Composite Films

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- Paulino, A.T.; Simionato, J.I.; Garcia, J.C.; Nozaki, J.; Polym, C. 2006, 64, 98.

- Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, T.; Ni, M.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Huang, D.; Fu, C.; Wang, S.; Sci, J.F. 2019, 84, 1411.

- Chung, J.H.Y.; Kade, J.; Jeiranikhameneh, A.; Yue, Z.; Mukherjee, P.; Wallace, G.G. ; Bioprinting. 2018, 12, e00031.

- Li, H.; Hu, C.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Adv, R.S. 2018, 8, 3736.

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; Sheikh, J.; Macromol, I.J.B. 2018, 116, 849.

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wu, J.; Le, X.; Hydrocoll, F. 2016, 52, 564.

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Dutta, J. , Trend Food Sci Technol. 2020, 97, 196.

- Hoseinnejad, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Katouzian, I.; Microbiol, C.R. 2018, 44, 161.

- Zheng, L.Y.; Zhu, J.F. ; Carbohydr Polym. 2003, 54, 527-530.

- Alderman, O.L.G.; Skinner, L.B.; Benmore, C.J.; Tamalonis, A.; Weber, J.K.R.; Review B, P. 2014, 90, 094204.

- Abdou, E.S.; Nagy, K.S.; Elsabee, M.Z.; Technol, B. 2008, 99, 1359.

- Bajaj, M.; Winter, J.; Gallert, C.; Eng J, B. 2011, 56, 51.

- Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Miao, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.; Niu, B.; Li, W.; Chem, F. 2019, 283, 397.

- Bahal, M.; Kaur, N.; Sharotri, N.; Sud, D.; Technol, A.P. 2019, 1.12. S. Roy, J. -W. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020, 148, 666.

- Higashimoto, S.; Azuma, M. , Appl Catal B Environ. 2009, 89, 557.

- Zhang, W.; Rhim, J.-W.; Packag, F. 2022, 31, 100806.

- Mesgari, M.; Aalami, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2021, 176, 530.

- Awwad, A.M.; Amer, M.W.; Salem, N.M.; Abdeen, A.O.; Int, C. 2020, 6, 151.

- Alsohaimi, I.H.; Nassar, A.M.; Elnasr, T.A.S.; Cheba, B.A.; Prod, J.C. 2020, 248, 119274.

- Pugazhendhi, A.; Prabhu, R.; Muruganantham, K.; Shanmuganathan, R.; Natarajan, S. , J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019, 190, 86.

- Hassan, H.; Omoniyi, K.; Okibe, F.; Nuhu, A.; Echioba, E. , J Appl Sci Environ Manag. 2019, 23, 1795.

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P.; Robert, D. , Ind Eng Chem Res. 2013, 52, 3581.

- Ali, A.; Ahmed, S. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 109, 273.

- Ullattil, S.G.; Narendranath, S.B.; Pillai, S.C.; Periyat, P.; Eng J, C. 2018, 343, 708.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yong, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Hydrocoll, F. 2019, 94, 80.

- Shafaee, M.; Goharshadi, E.K.; Mashreghi, M.; Sadeghinia, M. , J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2018, 357, 90.

- Gumiero, M.; Peressini, D.; Pizzariello, A.; Sensidoni, A.; Iacumin, L.; Comi, G.; Toniolo, R.; Chem, F. 2013, 138, 1633.

- Joy, J.; Mathew, J.; George, S.C. , Int J Hydrog Energy. 2018, 43, 4804.

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M.; Polym, C. 2018, 193, 19.

- Jbeli, A.; Ferraria, A.M.; Rego, A.M.B.D.; Boufi, S.; Bouattour, S. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 116, 1098.

- Salarbashi, D.; Tafaghodi, M.; Bazzaz, B.S.F.; Polym, C. 2018, 186, 384.

- Xing, Y.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Huang, R.; Wu, L.; Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Bi, X.; Prot, J.F. 2022, 85, 597.

- Lin, B.F.; Luo, Y.G.; Teng, Z.; Zhang, B.C.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Q.; Technol, L.W.-F.S. 2015, 63, 1206.

- Kraśniewska, K.; Gniewosz, M.; Sci, J.N. 2012, 62, 199.

- Vejdan, A.; Ojagh, S.M.; Adeli, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Technol, L.W.-F.S. 2016, 71, 88.

- Peighambardoust, S.J.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Pournasir, N.M.; Pakdel, P. , Food Packag Shelf Life. 2019, 22, 100420.

- Charles, S.; Jomini, S.; Fessard, V.; Bigorgne-Vizade, E.; Rousselle, C.; Michel, C. ; Nanotoxicology. 2018, 12, 357.

- Gea, M.; Bonetta, S.; Iannarelli, L.; Giovannozzi, A.M.; Maurino, V.; Bonetta, S.; Hodoroaba, V.-D.; Armato, C.; Rossi, A.M.; Schilirò, T.; Toxicol, F.C. 2019, 127, 89.

- Proquin, H.; Rodríguez-Ibarra, C.; Moonen, C.G.; Ortega, I.M.U.; Briedé, J.J.; de Kok, T.M.; Van Loveren, H.; Chirino, Y.I. ; Mutagenesis. 2017, 32, 139.

- de M, J., C. E. M. Campos, R. de F. P. M. Moreira, A. R. M. Fritz, Int J Biol Macromol. 2020, 151, 944.

- He, Q. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2016, 84, 153.

- Zolfi, M.; Mousavi, M.; Polym, C. 2014, 109, 118.

- Mohd, H.R.; Nur, A.I. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2020, 153, 1117.

- Masutani, E.M.; Kinoshita, C.K.; Tanaka, T.T.; Ellison, A.K.D.; Yoza, B.A.; Biomater, I.J. 2014, 979636.

- Khodaei, D.; Oltrogge, K.; Hamidi-Esfahani, Z.; Technol, L.W. 2020, 117, 108.

- Luo, Q.; Hossen, M.A.; Zeng, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, S.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y.; Eng, J.F. 2022, 313, 110762.

- Duconseille, A.; Astruc, T.; Quintana, N.; Meersman, F.; Sante-Lhoutellier, V.; Hydrocoll, F. 2015, 43, 360.

- T. Ahmad, A. Ismail, S. A., Ahmad, K. A. Khalil, Y. Kumar, K. D. Adeyemi, A. Q. Sazili, Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 85.

- Andreuccetti, C.; Galicia-García, T.; Gonz, R.; Martínez-Bustos, F.; Grosso, C.R.F.; Resour, P.R. 2017, 8, 11.

- Hosseini, S.F.; Rezaei, M.; Zandi, M.; Farahmandghavi, F.; Hydrocoll, F. 2015, 44, 172.

- Kumar, B.; Castro, M.; Feller, J.F.; Chem, J.M. 2012, 22, 10656.

- Halawa, A.A.; Elshopakey, G.E., M. A. Elmetwally, M. El-Adl, S. Lashen, N. Shalaby, E. Eldomany, A. Farghali, M. Z. Sayed-Ahmed, N. Alam, N. K. Syed, S. Ahmad, and S. Rezk, Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 19667.

- Knidri, H.E.L.; Belaabed, R.; EL, R.; Laajeb, A.; Addaou, A.; Lahsin, A. , J Mater Environ Sci. 2017, 8, 3648.

- Laaraibi, A.; Charhouf, I.; Bennamara, A.; Abourriche, A.; Berrada, M. , J Mater Environ Sci. 2015, 6, 3511.

- Teli, M.D.; Sheikh, J. , Int J Biol Macromol. 2012, 50, 1195.

- Miyanji, P.B.; Semnani, D.; Ravandi, A.H.; Karbasi, S.; Fakhrali, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Technol, P.A. 2021, 1.

- Qian, Y.-F.; Zhang, K.-H.; Chen, F.; Ke, Q.-F.; Mo, X.-M. , J Biomater Sci Polym. 2011, 22, 1099.

- Gharaie, S.S.; Habibi, S.; Nazockdast, H., J Textiles Fibrous Materials. 2018, 1, 1.

- Spoială, A.; Ilie, C.I.; Dolete, G.; Croitoru, A.M.; Surdu, V.A.; Truşcă, R.D.; Motelica, L.; Oprea, O.C.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E.; Dițu, L.M.; Membr.2022, 12, 12080804.

- Li, W.; He, D.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Banerjee, G.; Li, J.; Lee, S.H.; Dong, Q.; Gao, T.; Brudvig, G.W.; Waegele, M.M.; Jiang, D.-E.; Wang, D.; Sci, A.C.C. 2018, 4/5, 631.

- Kucukgulmez, A.; Celik, M.; Yanar, Y.; Sen, D.; Polat, H.; Kadak, E.; Chem, F. 2011, 126, 1144.

- Naghibzadeh, M.; Amani, A.; Amini, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, E.; Mottaghi-Dastjerdi, N.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Nanomater, J. 2010, 1.

- Islam, M.A.A.; Rahman, A.F.M.M.; Iftekhar, S.; Salem, K.S.; Sultana, N.; Bari, M.L.; Mater, J.C. 2016, 6, 172.

- Cui, Z.; Beach, E.S. , and P. T. Anastas, Green Chem Lett Rev. 2011, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y., X. Pan, X. Wang, R. Sun, Cellulose. 2014, 21. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S., L. Zhai, H. C. Kim, D. H. Pham, H. Alrobei, and J. Kim, Polymers. 2021, 13, 228.

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, H.; Tan, T.; Polym, C. 2017, 169, 101.

- Vilela, C.; Pinto, R.J.B.; Coelho, J.; M. R. M. Domingues, S. Daina, P. Sadocco, S. A. O. Santos, C. S. R. Freire, Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 73, 120.

- Gaabour, L.H.; Adv, A.I. 2021, 11, 105120.

- Anandhavelu, S., V. Dhansekaran, V. Sethuraman, H. J. Park, J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 1321.

- Zhang, Z. 2023, 352, 135095.

- Kumar, A.J. 2023. 335, 133812.

- Sivanesan, I., J. Gopal, M. Muthu, J. Shin, and J. W. Oh, Polymers. 2021. 13, 2330.

- Callister, W.D.; Rethwisch, D.G. , Materials Science and Engineering. 10th, ISBN: 978-1-119-40549-8, 2018.

| Sample | Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti |

Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti |

Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti |

Formula 4 1Chi-0Gel-2Ti |

Formula 5 1Chi-0Gel-5Ti |

Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti |

Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti |

Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti |

Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti |

Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan powder (g) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gelatin powder (g) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TiO2 (wt%) | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| Acetic acid 1% (ml) | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Sample | Film thickness (mm) |

Swelling in water | Swelling in ethyl alcohol | Percentage of shrinkage after drying (%) |

Bulk density (g/cm3) |

Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti |

0.03 ± 0.01 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 88.25 ± 2.15 | 1.48 ± 0.32 | Transparent, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti |

0.08 ± 0.02 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 68.97 ± 7.99 | 0.86 ± 0.15 | Opaque, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti |

0.08 ± 0.01 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 67.60 ± 3.58 | 0.89 ± 0.18 | Opaque, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti |

0.06 ± 0.01 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 77.22 ± 4.02 | 1.38 ± 0.13 | Transparent, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti |

0.09 ± 0.01 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 59.95 ± 3.59 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | Opaque, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti |

0.09 ± 0.03 | Excellent swelling | No swelling | 54.17 ± 9.28 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | Opaque, with a good appearance and no tear marks |

| Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti |

0.16 ± 0.02 | Moderately swelling | No swelling | 31.63 ± 2.37 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | Opaque with good appearance and minor tear marks |

| Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti |

0.17 ± 0.01 | Moderately swelling | No swelling | 28.50 ± 2.35 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | Opaque, with a good appearance and minor tear marks |

| Sample | Contact angle at t = 0 ms (Degree, º) |

Contact angle at t = 2000 ms (Degree, º) |

Decreasing contact angle over time (Degree/ms or º/ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti |

103.98 ± 6.35 | 92.77 ± 4.54 | 0.58 ± 0.21 |

| Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti |

91.32 ± 4.53 | 82.53 ± 6.00 | 0.43 ± 0.07 |

| Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti |

88.24 ± 3.63 | 80.08 ± 2.39 | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

|

Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti |

93.34 ± 7.47 | 86.50 ± 4.42 | 0.54 ± 0.09 |

| Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti |

80.34 ± 7.37 | 61.75 ± 4.55 | 1.44 ± 0.06 |

| Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti |

79.23 ± 4.05 | 59.92 ± 5.68 | 1.47 ± 0.28 |

| Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti |

73.16 ± 5.50 | 40.93 ± 5.17 | 1.48 ± 0.24 |

| Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti |

69.72 ± 6.54 | 40.56 ± 4.17 | 1.51 ± 0.11 |

| Sample | Percentage of shrinkage (%) |

Bulk density of dry films (g/cm3) |

Weight of dry films (g) |

Weight of absorbed solvent (g) |

Vr | Crosslink density × 10-2 (Ve, mol/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti |

88.25 ± 2.15 | 1.48 ± 0.32 | 0.0265±0.0025 | 0.0017 | 0.9013 | 2.263 |

| Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti |

68.97 ± 7.99 | 0.86 ± 0.15 | 0.0221±0.0020 | 0.0023 | 0.9604 | 4.162 |

| Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti |

67.60 ± 3.58 | 0.89 ± 0.18 | 0.0256±0.0026 | 0.0008 | 0.9689 | 4.627 |

|

Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti |

77.22 ± 4.02 | 1.38 ± 0.13 | 0.0338±0.0018 | 0.0010 | 0.9550 | 3.912 |

| Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti |

59.95 ± 3.59 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.0484±0.0072 | 0.0018 | 0.9624 | 4.262 |

| Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti |

54.17 ± 9.28 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 0.0421±0.0059 | 0.0013 | 0.9706 | 4.735 |

| Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti |

31.63 ± 2.37 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.0761±0.0139 | 0.0005 | 0.9938 | 7.677 |

| Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti |

28.50 ± 2.35 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.0611±0.0032 | 0.0006 | 0.9899 | 6.758 |

| Sample |

Capacitance × 10-10 (F) |

Dielectric constant |

|---|---|---|

|

Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti |

0.029 ± 0.062 | 1.54 ± 0.22 |

| Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti |

0.033 ± 0.095 | 1.58 ± 0.54 |

| Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti |

0.284 ± 0.011 | 3.33 ± 0.13 |

|

Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti |

0.129 ± 0.015 | 1.69 ± 0.17 |

| Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti |

0.197 ± 0.039 | 1.80 ± 0.07 |

| Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti |

1.550 ± 0.150 | 8.10 ± 0.73 |

| Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti |

0.090 ± 0.005 | 1.64 ± 0.27 |

| Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti |

0.043 ± 0.003 | 2.01 ± 0.70 |

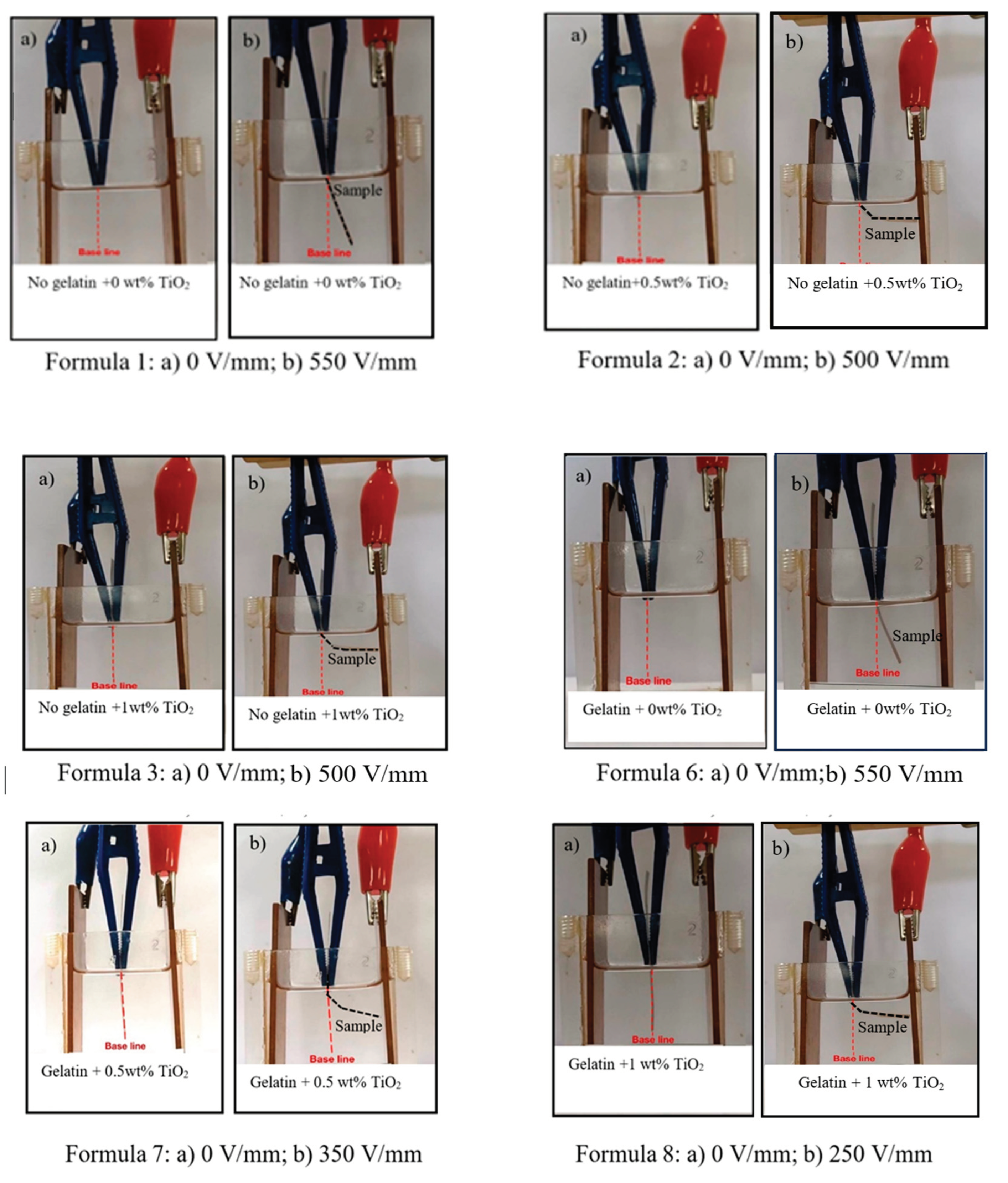

| Electric field strength (V/m) |

Formula 1 1Chi-0Gel-0Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 2 1CH-0Gel-0.5Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 3 1Chi-0Gel-1Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 6 1Chi-1Gel-0Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 7 1Chi-1Gel-0.5Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 8 1Chi-1Gel-1Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 9 1Chi-1Gel-2Ti (Degree, °) |

Formula 10 1Chi-1Gel-5Ti (Degree, °) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 25 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 50 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 3.31 ± 0.17 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 100 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 3.37 ± 1.04 | 5.92 ± 0.22 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 4.64 ± 0.98 | 4.61 ± 2.58 | 4.65 ± 0.85 | 5.23 ± 1.76 |

| 150 | 2.64 ± 0.33 | 4.60 ± 1.65 | 9.07 ± 0.89 | 3.65 ± 0.01 | 6.70 ± 1.74 | 4.97 ± 0.65 | 5.16 ± 0.33 | 5.64 ± 3.33 |

| 200 | 4.02 ± 1.65 | 5.57 ± 1.50 | 10.44±0.73 | 4.23 ± 0.76 | 9.00 ± 1.56 | 32.25±3.56 | 6.21 ± 1.65 | 6.42 ± 3.65 |

| 250 | 4.03 ± 1.00 | 7.22 ± 2.30 | 18.96±3.83 | 4.62 ± 0.83 | 17.85±2.58 | 61.48±6.97 | 6.40 ± 1.00 | 6.50 ± 2.00 |

| 300 | 4.17 ± 1.89 | 9.25 ± 3.12 | 43.67±4.39 | 4.82 ± 0.65 | 38.87±3.01 | 68.58±7.36 | 42.07±0.89 | 8.17 ± 1.89 |

| 350 | 4.91 ± 0.41 | 11.37±3.71 | 54.63±4.16 | 5.25 ± 0.01 | 59.06±3.91 | 72.81±5.57 | 50.09±2.10 | 10.29±2.41 |

| 400 | 5.28 ± 3.35 | 13.59±4.97 | 58.15±1.72 | 8.07 ± 0.89 | 64.77±4.98 | 73.72±5.27 | 52.54±0.35 | 14.84±5.35 |

| 450 | 8.70 ± 4.52 | 17.91±3.93 | 59.34±1.50 | 9.49 ± 0.41 | 67.62±4.37 | 78.02±2.56 | 56.70±5.52 | 19.70±7.52 |

| 500 | 13.58±3.51 | 65.88±5.02 | 62.61±2.23 | 13.84±2.35 | 70.05±2.18 | 79.48±3.28 | 59.34±0.51 | 26.58±6.51 |

| 550 | 22.03±5.34 | 68.35±2.33 | 64.04±2.46 | 23.81±4.51 | 70.03±1.53 | 81.29±0.75 | 60.05±0.30 | 34.03±7.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).