1. Introduction

The increasing demand for high-resolution, real-time weather forecasting has catalyzed the exploration of unconventional data sources and methodologies. Traditional meteorological models, while robust, often lack the granularity required for hyper-local predictions, especially in heterogeneous terrains and microclimates. In turn, weather forecasting can be profitably used to predict crop yield by exploiting similar ML tools [

1]. The link between meteorology and biology extends to the scale of the predictive models, and represents a profound connection between two apparently detached fields [

2]. Recent advancements in plant electrophysiology suggest that plants, through their bioelectrical signals, may serve as sensitive indicators of environmental changes, offering a novel avenue for localized weather forecasting [

3]. Plants exhibit a range of electrical activities in response to environmental stimuli, including variations in temperature, humidity, light intensity, and mechanical stress [

4]. These bioelectrical responses, encompassing action potentials and variation potentials, are integral to plant signaling mechanisms and have been documented to reflect external environmental conditions [

5]. The potential of these signals as proxies for environmental monitoring has been further underscored by studies demonstrating their correlation with specific abiotic stressors [

6].

The integration of machine learning (ML) techniques with plant electrophysiological data has opened new frontiers in environmental sensing. ML algorithms, particularly deep learning models, have shown proficiency in deciphering complex, non-linear patterns within bioelectrical signals, enabling the classification and prediction of various environmental parameters [

7]. For instance, supervised ML models have been employed to predict vines water status based on electrophysiological inputs, achieving notable accuracy [

8]. In another study, machine learning algorithms (Artificial Neural Networks, Convolutional Neural Network, Optimum-Path Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors and Support Vector Machine) have been combined with Interval Arithmetic, and findings showed that Interval Arithmetic and supervised classifiers are more suitable than deep learning techniques [

9].

Building upon this foundation, the present study explores the feasibility of utilizing plant bioelectrical signals as inputs for ML models aimed at forecasting local weather conditions. By harnessing the innate sensitivity of plants to their immediate environment, we propose a biomimetic approach to weather prediction that complements existing meteorological methods. This interdisciplinary endeavor aligns with the principles of biomimetics, wherein biological systems inspire innovative technological solutions.

The objectives of this research are threefold: (1) to establish a reliable methodology for recording and processing plant bioelectrical signals in situ; (2) to develop and train ML models capable of translating these signals into accurate short-term weather forecasts; and (3) to evaluate the performance of these models against conventional forecasting techniques. Through this study, we aim to contribute to the development of sustainable, plant-based environmental monitoring systems that enhance the precision of local weather forecasting.

The organisation of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the experimental setup and algorithms.

Section 3 describes the procedure applied and confronts with climatic readings. Finally our conclusions are drawn in

Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

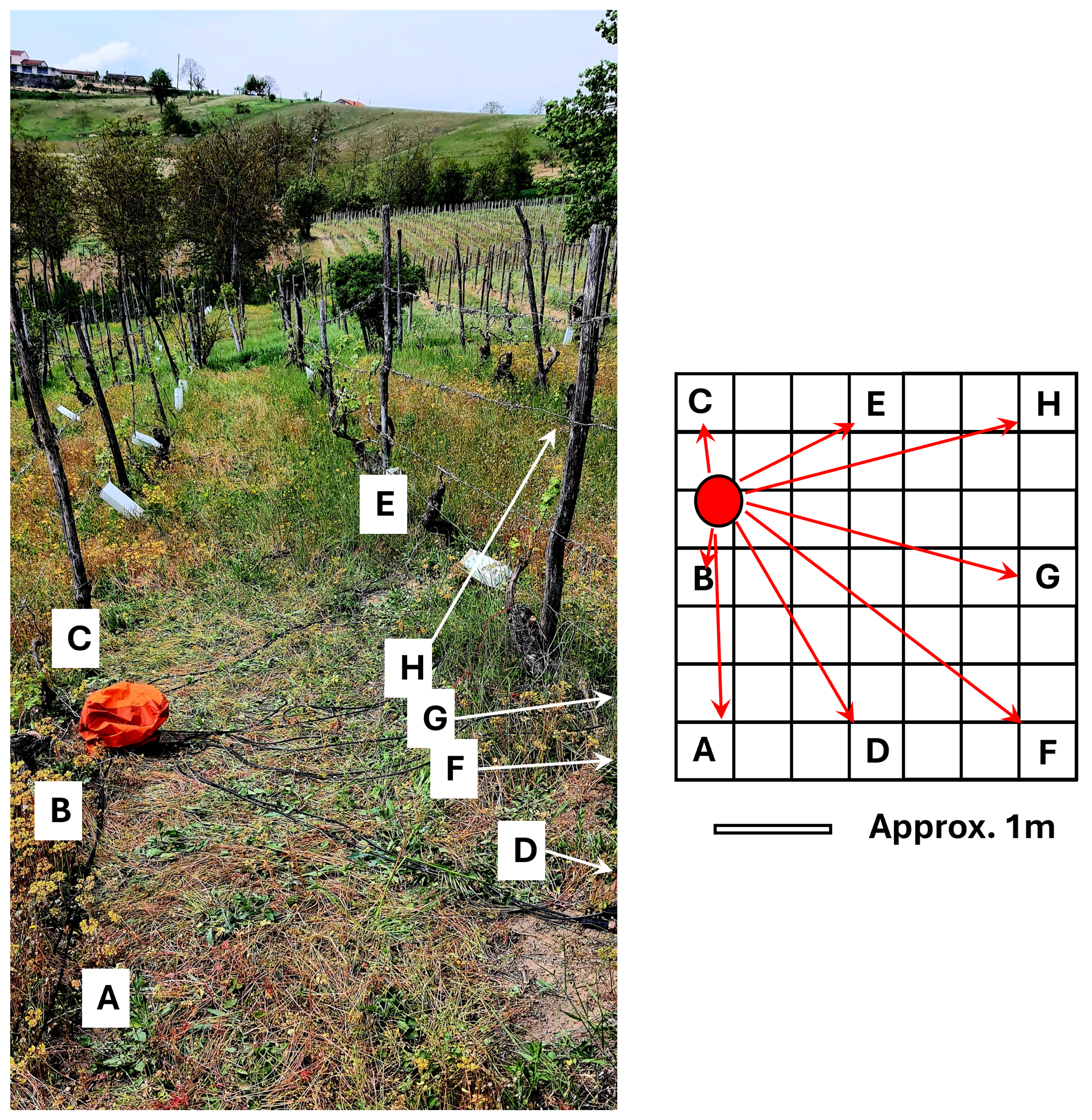

A traditional vineyard plant was selected to perform this study, as shown in

Figure 1. It is located in Vigliano d’Asti, Monferrato, Italy (Cantina Adorno). For the collection of bioelectric potentials, two needle electrodes (MN4022D10S subdermal electrodes from SPES MEDICA SRL, Italy) 0.4 mm diameter, 22 mm in length were used to contact each plant by puncturing the bark. They were positioned 1 cm apart, and connected using double shielded ultra low resistance cable INCA1050HPLC (MD, Italy) for high fidelity audio application to a DI-710-US data logger (DATAQ Instruments, Akron, U.S.A.), used in differential channel mode, recording at a frequency of 1 Sample/s per channel, with 16 bit resolution and 1000 mV of voltage range. The maximum cable length was 4 m, adding an additional resistance component of 50 ± 10 m

m

−1 and an additional capacitance component of 150 ± 10pF mm

−1. Local climatic data was provided by a probe station (Primo Principio S.r.l., Italy). Collection site `A’ represents a plant under recovery phase with no fruits yet, ’B’ a plant after recovery bringing fruits, ’C’ a dead stump, ’D’ a plant after recovery bringing fruits, ’E’ a plant manifesting the symptoms of

flavescence dorée, ’F’ a dead stump, ’G’ a plant after recovery bringing fruits, ’H’ a healthy individual. This particular disease has become endemic in Monferrato and other surrounding areas in Italy. Interestingly, the qualitative features of biopotential signals well characterizes the health status of the vines, and we can easily cluster the "cleaner" waveforms collected from healthy and plants undergone full recovery, that bring fruits, from dead stumps still showing an elaborated electrical activity (vines maintain living roots for years even when the photosynthetic part has gone), from vines that show the typical symptoms of

flavescence dorée.

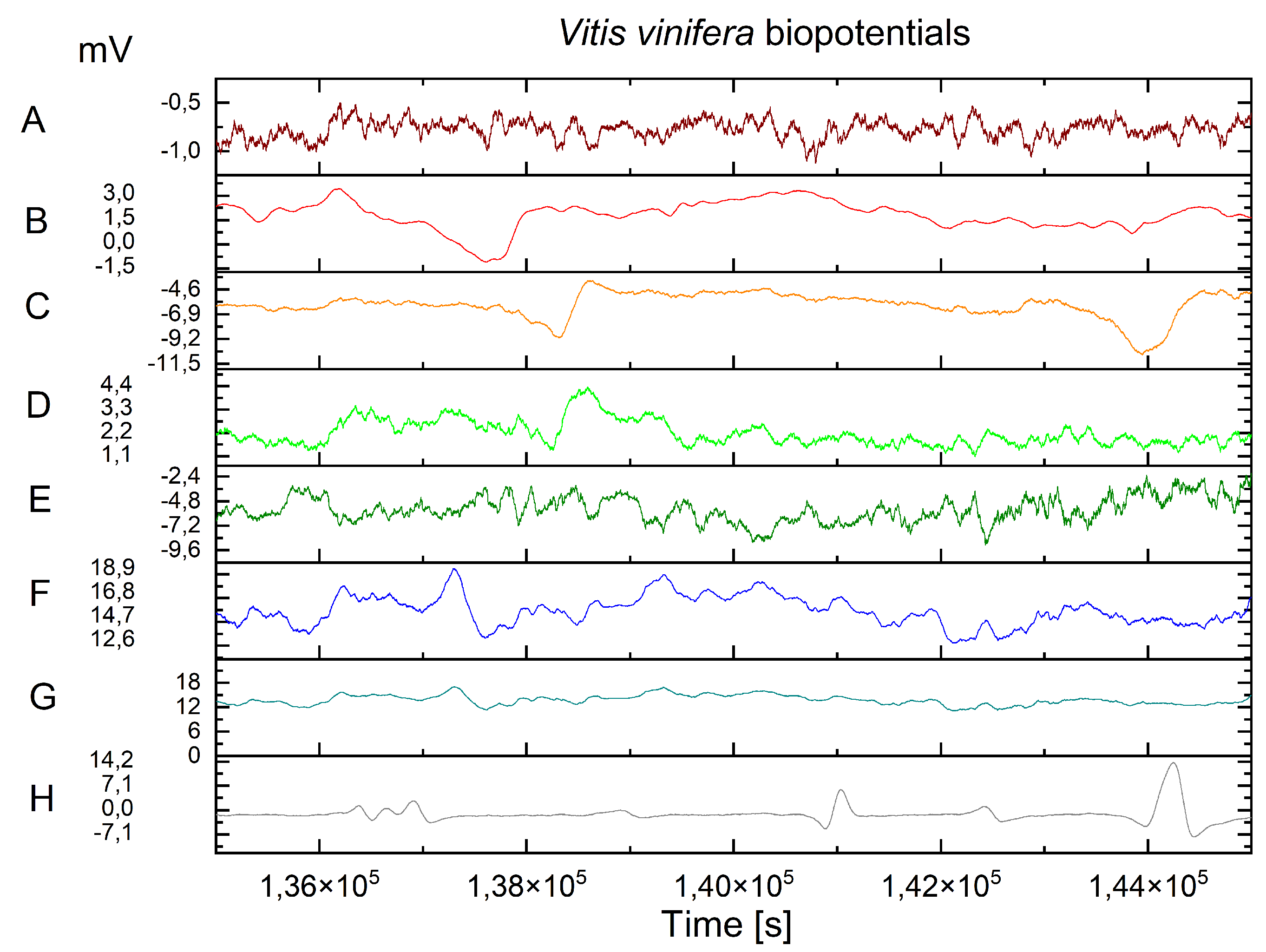

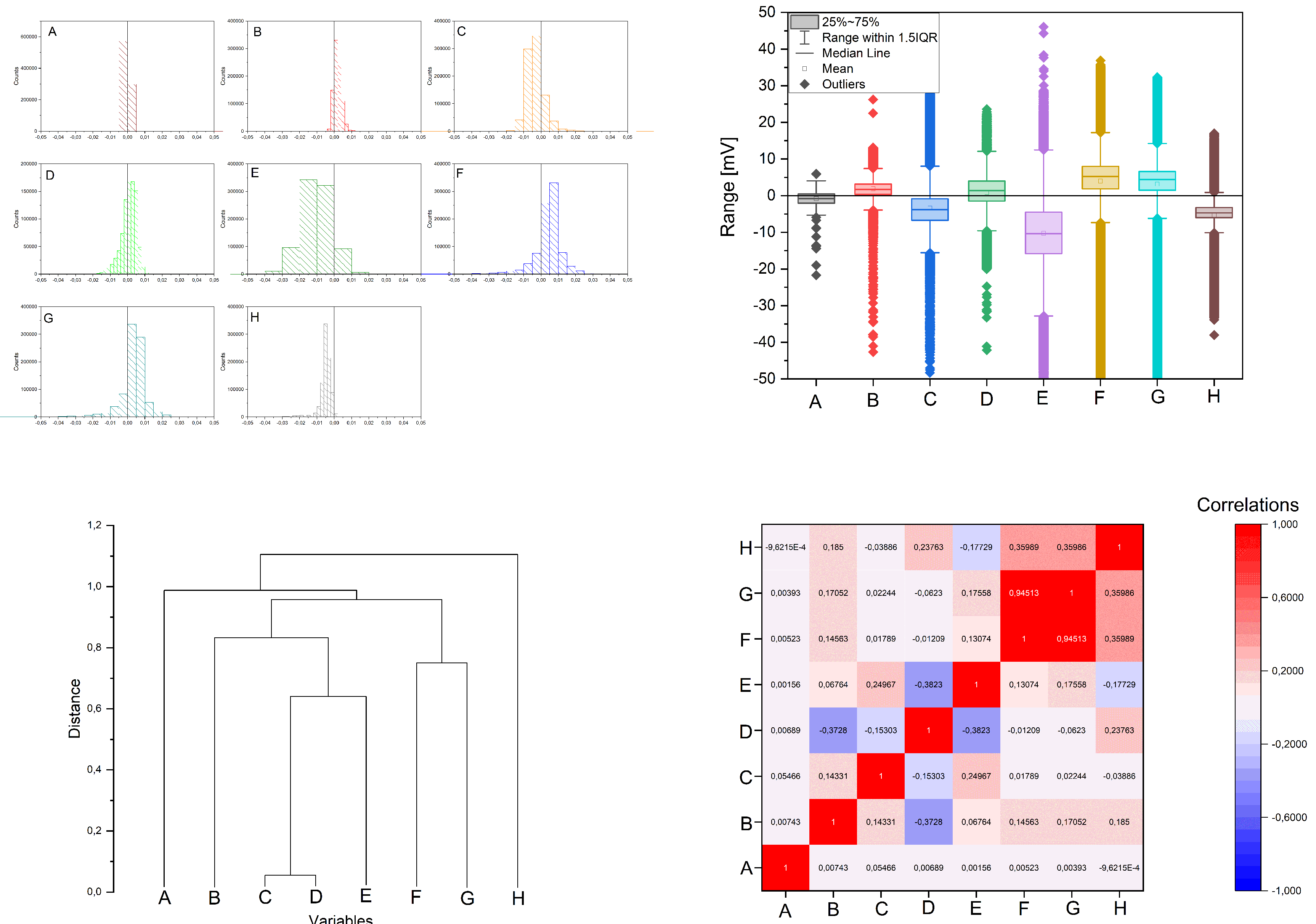

The acquired data is shown in

Figure 2, after being smoothed using a first-order Savitzky–Golay function with a window size of 121 points. Statistical data is being presented on

Figure 3, where we can witness overall a good degree of interdependency between a specific plant couple (F-stump and G-recovery with a positive correlation of 0.94513) and less impacting correlations (factors between .3823 and .23763 for couples B and D (both in recovery), E and D (disease affected and in recovery), E and C (disease affected and stump). F, G, H stand on the same row, so D and E, so A, B, C. Their real space distance is: between F and G 150 cm, between B and D 370 cm, between E and D 390 cm, between E and C 220 cm.

2.2. Software Setup

The data collected was sorted in different comma separated values files. The saved data was loaded through Python 3.9, preprocessed by filtering the quantile 0.8 of the frequency domain of the signal . The 8 signals were aggregated from 1 second to 1 hour granularity using their median values. Eventually the 8 signals were merged with the Temperature data for model (1) and with Humidity data for model (2), both at 1 hour granularity. Then the min-max scaler was fitted to transform each file separately. The ML algorithm selected for the data analysis is the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Recurrent Neural Network [

11] with peephole augmentation [

12], wrapped by a Bidirectional layer. The LSTM requires 3 dimension as the input shape, with number of samples (number of time point per sequence), number of observations (number of sequences) and number of features (number of voltage readings), we rearranged the data with a window of 48 hours, so to be able to identify circadian cycles of the temperature for each batch of data. We used the same approach to predict relative humidity in the air. Therefore, with N datapoints of voltage readings and temperatures, we obtained a train shape of (N, 48, 8) and test shape of N/8. The ML problems defined (1) and (2) attempt to predict the (1) temperature and (2) humidity for the current hour (t) given 48 hours of previous data from time t-1 to time t-48. Through different trials we identified the following as architecture of the Tensorflow layers.

Model: "sequential"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

bidirectional (Bidirection (None, 48, 32) 3296

al)

multi_head_attention (Mult (None, 48, 32) 4224

iHeadAttention)

dense (Dense) (None, 48, 32) 1056

dropout (Dropout) (None, 48, 32) 0

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 48, 1) 33

=================================================================

Total params: 8609 (33.63 KB)

Trainable params: 8609 (33.63 KB)

The problem was implemented as a regression and the loss used was the mean squared error. The training was performed by minimizing the validation loss (the loss of the test dataset) and also the

coefficient was collected. The learning rate policy was starting at 0.00005 and increasing to reach 0.01 in the last epoch. The number of epochs was set to 1200. For a more detailed description see the CombinedLRScheduler class in the codebase

1.

3. Results

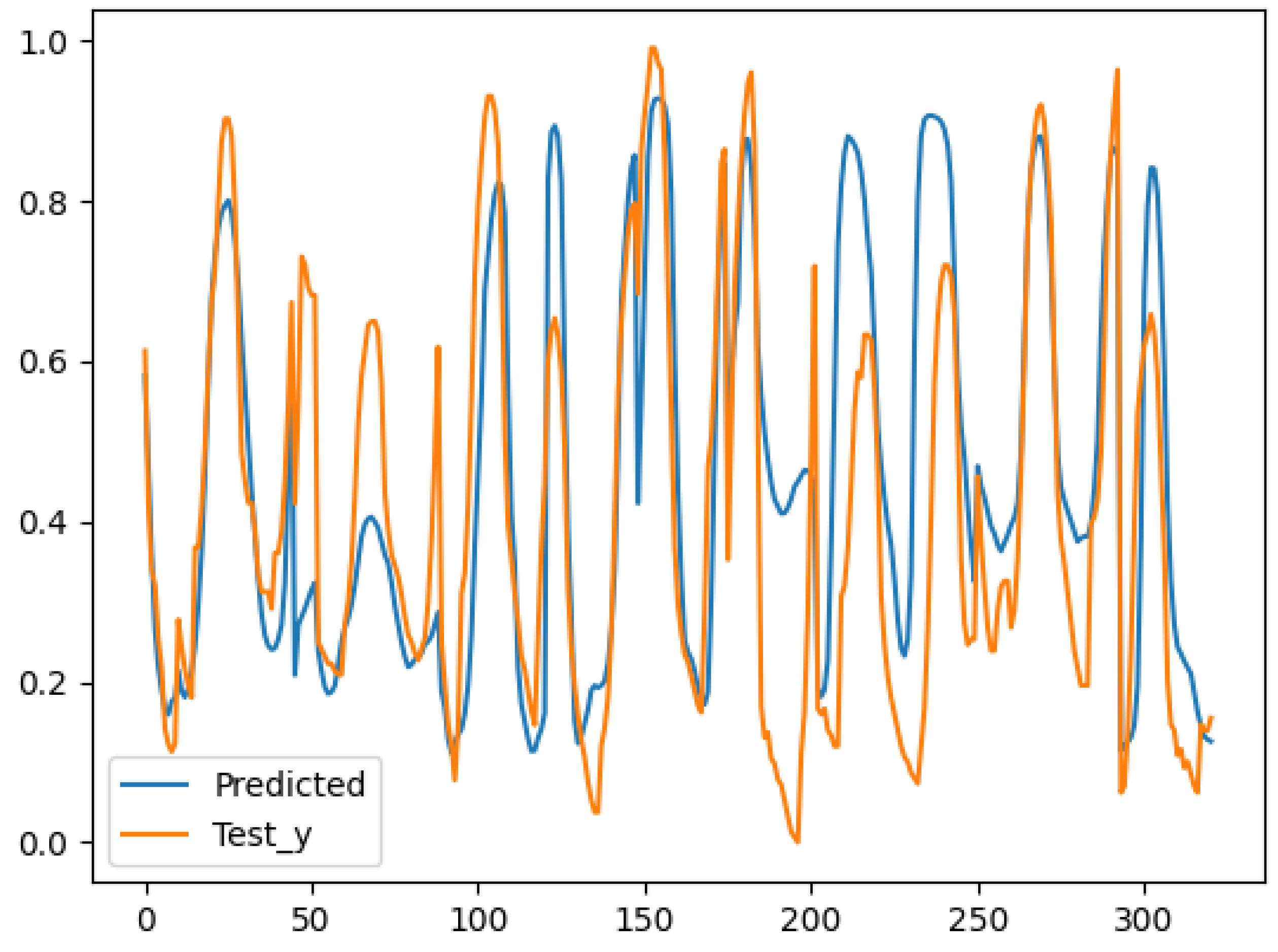

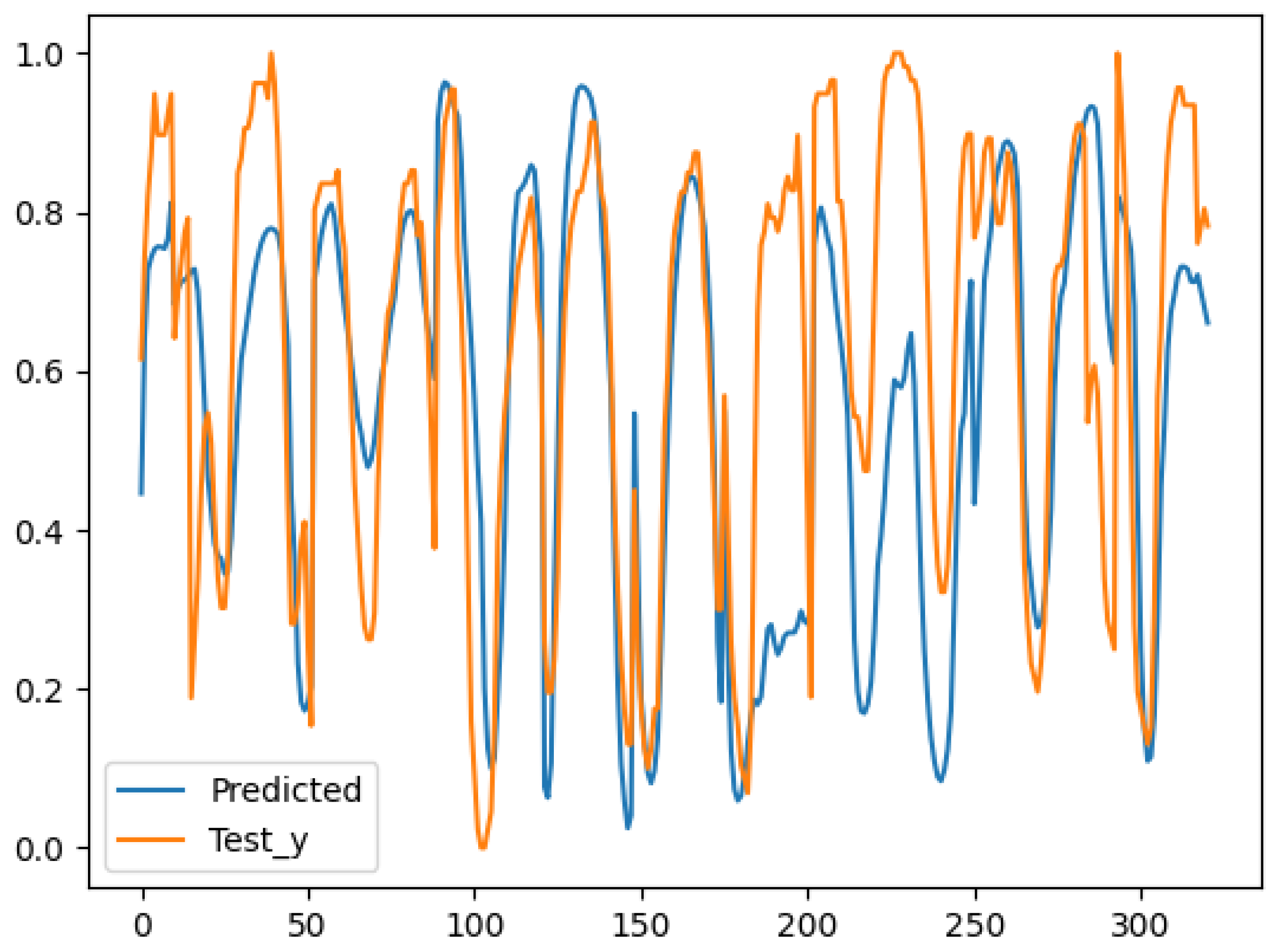

Both model (1) and (2) were assessed with validation data. The results hereby shown are normalized values ranging from 1 to 0. As we are nailing out the correlation among the signals, we disregard rescaling the predictions and the observations. Model (1) produced the results depicted in

Figure 4 where its prediction is shown in blue, against the observed temperature data in orange.

Model (2) produced the results depicted in

Figure 5, featuring the following prediction (blue) for the observed relative air humidity data (orange):

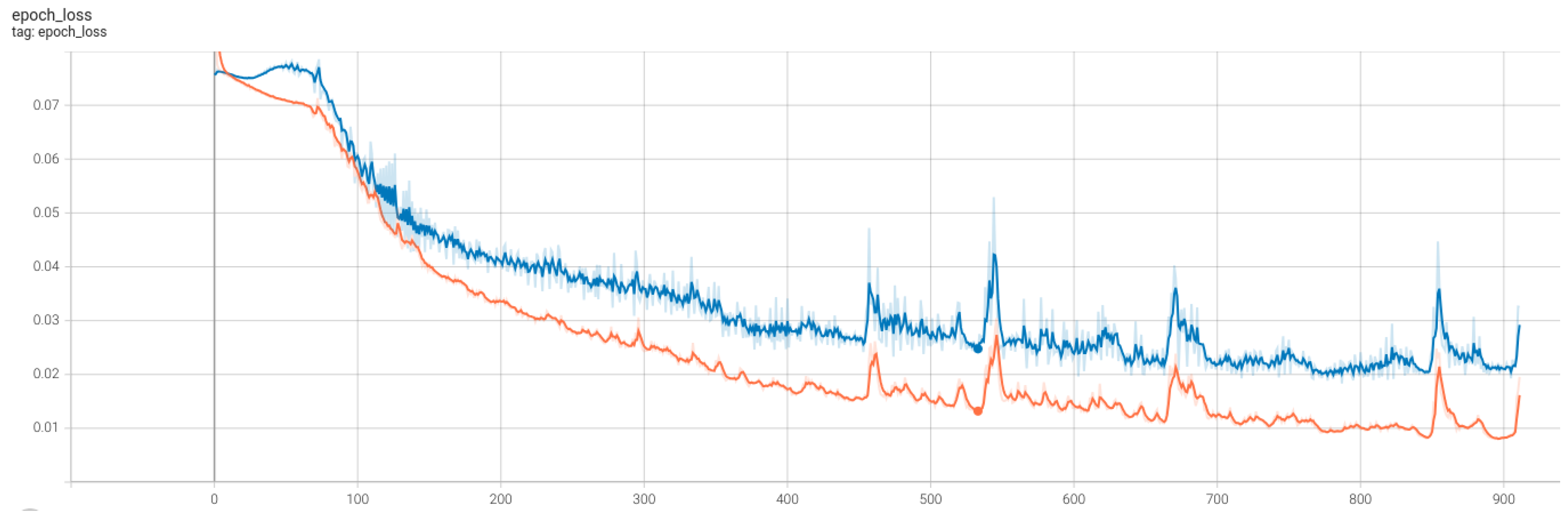

The training of model (1), developed to predict temperature data, produced the loss and val_loss shown in

Figure 6.

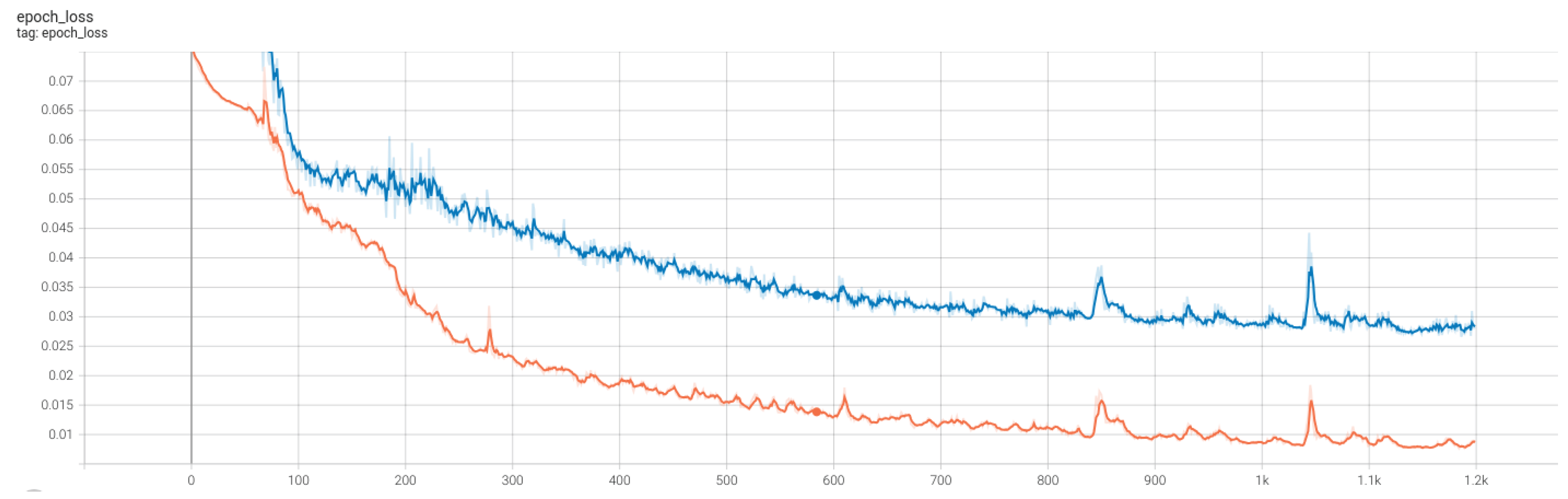

The training of model (2), developed to predict relative humidity, produced the loss and val_loss shown in

Figure 7.

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using bioelectrical signals from Vitis vinifera as a rich, biologically grounded source of environmental information. By employing a robust data acquisition system and applying advanced machine learning models, we successfully predicted short-term meteorological parameters such as temperature and relative humidity with promising accuracy. The electrophysiological signals not only reflected the plant’s health status but also contained time-sensitive patterns aligned with rapid weather transitions, suggesting an innate environmental encoding within plant biopotentials.

Our findings support the concept that plants act as living sensors, exhibiting sensitivity to microclimatic fluctuations that can be computationally decoded. The high predictive performance of recurrent and attention-based models highlights the potential of biologically rooted weather forecasting systems, especially valuable in locations lacking dense sensor networks or in climate-sensitive agricultural regions.

Future work will focus on scaling up the study by incorporating a wider biodiversity of plant species and environmental conditions to generalize the models. Integration of multi-modal data (e.g., optical, thermal, chemical) alongside electrophysiology could enhance predictive granularity. Lastly, we envision the development of low-power, embedded hardware systems for real-time processing and edge inference, enabling the deployment of biohybrid weather stations. These advancements could revolutionize ultra-local environmental monitoring by fusing biological intelligence with modern AI techniques.

Funding

Funding of the activities was granted by Zenit Arti Audiovisive, Torino, Italy, within the project: "Il codice del bosco".

References

- Chaudhary, S., Bajaj, S.B., Mongia, S. Analysis of a Novel Integrated Machine Learning Model for Yield and Weather Prediction: Punjab Versus Maharashtra. In: Singh, Y., Verma, C., Zoltán, I., Chhabra, J.K., Singh, P.K. (eds) Proceedings of International Conference on Recent Innovations in Computing. ICRIC 2022. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 2023, 83-93.

- Covert, M.W. and Gillies, T.E. and Takamasa, K. and Agmon, E. A forecast for large-scale, predictive biology: Lessons from meteorology Cell Systems 2021, 12(6), 488-496.

- Chiolerio, A. and Gagliano, M. and Pilia, S. and Pilia, P. and Vitiello, and G. Dehshibi, M. and Adamatzky, A. Bioelectrical synchronization of Picea abies during a solar eclipse Royal Society Open Science 2025, 12(4), 241786.

- Wilkening, Soren H.P. Plant electrophysiological reactions to specific environmental conditions bioRxiv 2024, 2024.12.03.626606.

- Tran, D. and Dutoit, F. and Najdenovska, E. and Wallbridge, N. and Plummer, C. and Mazza, M. and Raileanu L.E. and Camps, C. Electrophysiological assessment of plant status outside a Faraday cage using supervised machine learning Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 17073.

- Najdenovska, E. and Dutoit, F. and Tran, D. and Rochat, A. and Vu, B. and Mazza, M. and Camps, C. and Plummer, C. and Wallbridge, N. and Raileanu, L. E. Identifying General Stress in Commercial Tomatoes Based on Machine Learning Applied to Plant Electrophysiology. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(12), 5640.

- Imam, T. and Hasri, A. and Hidetaka, N. and Rofiq, ’A.R. and Ades, T. Deep learning algorithm for room temperature detection using bioelectric potential of plant data Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 101, 107214.

- Cattani, A. and de Riedmatten, L. and Roulet, J. and Smit-Sadki, T. and Alfonso, E. and Kurenda, A. and Graeff, M. and Remolif, E. and Rienth, M. Water status assessment in grapevines using plant electrophysiology OENO One 2024, 58(4), 8209.

- Pereira, D.R. and Papa, J.P. and Rosalin Saraiva, G.F. and Souza, G.M. Automatic classification of plant electrophysiological responses to environmental stimuli using machine learning and interval arithmetic Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 145, 35-42.

- Kalman R.E. New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems Transactions of the ASME–Journal of Basic Engineering 1960, 82, 35-45.

- Hochreiter, S. and Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735-1780.

- Gers, F.A. and Schmidhuber, J. Recurrent nets that time and count Proceedings of the IEEE-INNS-ENNS International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. IJCNN 2000. Neural Computing: New Challenges and Perspectives for the New Millenniu 2000, 3, 2.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).