1. Introduction

The global construction industry, a vital engine for economic development, concurrently exerts a substantial economic, environmental, and social footprint [

1,

9]. Recognizing this, there is an escalating imperative to transition towards sustainability and adopt Circular Economy (CE) principles to alleviate these impacts, a focus extensively documented in recent research [

5,

27]. For a comprehensive review of CE in construction and demolition waste management, see [

28]. Consequently, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria are increasingly pivotal, profoundly influencing the construction sector's trajectory. Recent reviews, such as Jing et al. [

12], explore ESG integration with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Building Information Modelling (BIM). Further insights into secure ESG data management and the materiality of ESG criteria in construction are provided by [

13] and [

15], respectively. This evolution is propelled by mounting stakeholder demands, shifting investment paradigms favoring sustainable and ethical operations, and an understanding that strong ESG performance can correlate with enhanced project outcomes and sustained value creation, a trend also observed in broader corporate studies linking ESG to productivity [

16,

17].

1.1. ESG in the Context of Sustainable Development and Circular Economy

To understand the context of ESG in construction, it is essential to define its core components and relationship with overarching sustainability paradigms. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria represent a set of standards for a company’s operations that socially conscious investors use to screen potential investments [

15]. The Environmental aspect examines a company's impact on the natural world, including energy use, waste, pollution, natural resource conservation, and treatment of animals [

1,

38,

39,

41]. The Social component addresses relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates, covering labor practices, talent management, product safety, and community relations [

2,

10,

37,

40]. Governance deals with a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights [

16]. These three pillars are increasingly recognized as integral to sustainable development, aligning closely with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

12].

The Circular Economy (CE) in construction, which emphasizes principles such as reduce, reuse, recycle, refurbish, and recover, is directly relevant to ESG [

5,

27,

28]. CE practices significantly contribute to the Environmental pillar by promoting resource efficiency, waste reduction, and lower emissions [

18,

21,

25]. Socially, CE can enhance community well-being and contribute to affordable housing through optimized resource use and innovative material applications [

2,

27].

1.2. Foundational Theories for ESG in Construction

1.2.1. Institutional Theory

Institutional theory provides a robust lens for understanding the adoption of ESG practices in the construction industry [

3,

6,

7]. It posits that organizations conform to institutional pressures coercive (e.g., regulations, legal mandates), mimetic (e.g., imitating successful peers), and normative (e.g., professional standards, societal expectations) to gain legitimacy and ensure survival [

43]. In construction, these pressures manifest as environmental regulations, green building certifications, client demands for sustainable projects, and industry-wide ethical standards, all driving firms towards greater ESG integration [

6,

7]. Recent studies highlight how these pressures influence environmental management performance in projects [

7] and contractors' adaptation to sustainable practices [

6]. Some research also extends institutional theory to understand entrepreneurial behaviors in contexts influenced by social norms [

44]. While Institutional Theory suggests that external pressures drive ESG adoption, the tangible economic consequences of such adoption at a macro level remain insufficiently quantified, forming a key motivation for this study.

1.2.2. Conceptualizing ESG in Construction Projects (C-ESG)

While national-level ESG data provides a macro perspective, the translation of these principles to the project level is crucial. "Construction Project Level-based ESG" (C-ESG) involves integrating ESG considerations directly into the lifecycle of construction projects [

13]. This includes responsible sourcing of materials, ensuring site safety and fair labor practices, minimizing environmental disruption, engaging with local communities, and upholding ethical conduct throughout the project [

8,

15]. Frameworks are being developed to manage and report on ESG data specifically for construction projects, sometimes leveraging technologies like blockchain for transparency [

13]. Identifying material ESG metrics specific to the engineering and construction (E&C) industry is an ongoing effort, with organizations like SASB, TCFD, and GRI providing guidance [

15].

1.3. Sustainability Assessment Frameworks in Construction

Numerous sustainability assessment frameworks have been developed to evaluate and guide sustainable practices in the construction sector. Prominent examples like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) provide context by offering rating systems for building sustainability. Beyond these, more comprehensive Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) frameworks aim to integrate environmental, economic, and social impacts throughout a building's lifecycle [

11,

14,

30,

34,

35].

Several recent studies contribute to the development and application of such frameworks. For instance, research has focused on frameworks for social sustainability assessment [

2], integrated sustainability assessment for construction companies using financial, social, and environmental indicators [

4], assessing circular economy in waste management [

5], and lean-sustainability assessment [

8]. Others have developed LCSA index systems for building energy retrofits [

14], explored LCSA for residential buildings by defining Triple Bottom Line (TBL) indicators [

34], and proposed participatory LCSA frameworks for social housing regeneration [

35]. Frameworks have also been tailored for specific industrial contexts, such as petroleum refinery projects, though the principles are adaptable [

31]. This study’s chosen ESG indicators and economic outcomes (construction value added, housing costs) can be mapped to the dimensions (environmental, economic, social, institutional, technical) typically found within these comprehensive sustainability assessment frameworks, providing theoretical grounding for their selection and analysis.

1.4. Integrating ESG and Key Construction Concepts

1.4.1. ESG in Construction: An Overview

The integration of ESG principles in the construction sector is gaining significant traction, driven by the need for sustainable development and responsible business practices [

8,

12,

13,

15]. Studies are increasingly exploring the materiality of ESG factors in the engineering and construction industry [

15] and developing systems for ESG data management [

13]. The relationship between ESG performance and broader economic indicators like total factor productivity is also being investigated in various sectors, offering insights applicable to construction [

16,

17].

1.4.2. Environmental Dimensions in Construction

The environmental dimension of ESG in construction encompasses a wide array of practices and assessments aimed at minimizing the industry's ecological footprint [

1]. Sustainable construction practices involve strategies for energy efficiency, reduced emissions, and sustainable material use [

21,

39,

41,

45]. Circular Economy (CE) applications are central, focusing on material reuse [

18], waste valorization [

5,

28], and design for disassembly [

27]. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a key methodology for evaluating environmental burdens throughout a project's lifecycle [

11,

14,

18,

30,

38], often integrated with BIM [

18,

30]. Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) management is a critical focus, with strategies for reduction, recycling, and responsible disposal being paramount [

5,

28,

32]. The impact of energy consumption (renewable vs. fossil fuel), material efficiency, and emissions remains a core concern [

1,

38].

1.4.3. Social Dimensions in Construction

Social sustainability in construction addresses the well-being of all stakeholders, including workers and communities [

2,

10]. Key aspects include ensuring fair labor practices, prioritizing occupational health and safety [

37], and investing in human capital development through education and R&D [

10]. Community engagement and addressing local needs are crucial for social legitimacy and project success [

2,

40]. Social equity considerations, such as income inequality (e.g., GINI index), are also relevant as the construction sector can play a role in local employment and economic upliftment. Internet penetration is increasingly seen as an enabler for access to information, education, and economic opportunities, which are social considerations.

1.4.4. Governance Dimensions in Construction

Effective governance in construction involves robust corporate governance mechanisms, adherence to high ethical standards, transparency in operations, and accountability to stakeholders [

15]. The impact of factors like control of corruption, rule of law, and political stability is significant, as these can influence project costs, timelines, investment attractiveness, and overall project integrity [

7,

16]. Strong governance frameworks are essential for mitigating risks and ensuring that construction activities contribute positively to sustainable development.

1.4.5. Economic Outcomes and Context

Literature on the drivers of construction costs [

1] and value added is extensive, though the specific linkage to comprehensive ESG performance is an evolving area. Some studies have begun to explore the connection between ESG components and economic performance metrics, such as firm productivity [

16,

17] or the cost-effectiveness of sustainable material choices [

42]. This research aims to contribute by examining these links at a macro (national value added) and meso (housing construction costs) level using a broad set of ESG indicators.

1.5. Key Technologies and Methodologies in Sustainable and ESG-Driven Construction

Technological improvements are critical for enabling sustainable and ESG-driven practices in the building industry. Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a key component of this technological integration, providing a powerful platform for design optimization, material quantification, and comprehensive lifecycle management, all contributing to sustainability and CE principles [

12,

18,

22,

26,

29,

30,

32]. Its adaptability is shown in heritage building preservation (HBIM) [

26] and renovation planning [

29], with BIM-LCA integration enhancing environmental evaluations [

18,

30].

Complementing BIM, the Internet of Things (IoT) enables real-time monitoring, resource tracking, energy management, and safety, crucial for ESG outcomes [

19,

24,

25], from material tracking in CE [

25] to broader civil engineering insights [

19]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is leveraged for predictive analytics, resource optimization, risk management, and sustainable design efficiency [

19,

22,

23,

24], including automating Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) data analysis outcomes, such as industry value added, and crucial project-level determinants like housing construction costs. While advanced dynamic panel data methodologies like the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) are ideal for capturing complex temporal relationships and controlling for endogeneity, practical data limitations or model estimation challenges in certain contexts as encountered in preliminary phases of this research may necessitate reliance on robust alternatives, such as Two-Way Fixed Effects models, to still account for unobserved national heterogeneity.

The primary purpose of this work is to contribute to addressing these deficiencies by empirically investigating the multifaceted impacts of national-level ESG performance on key economic indicators within the global construction industry. This study aims to provide a robust, data-driven understanding of how specific ESG factors contribute to economic outcomes, thereby offering actionable insights for enhancing sustainability in the sector.

To this end, the principal objectives of this research are:

To empirically investigate the relationship between a comprehensive suite of national-level ESG indicators and construction industry value added using global panel data, employing a Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) model to account for unobserved country and time effects.

To conduct a cross-sectional analysis exploring the relationship between 2022 housing construction costs, contemporaneous national ESG indicators, and overall construction industry value added using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression and correlation analysis.

To identify key ESG and economic drivers of construction industry value added by complementing econometric findings with machine learning techniques (Random Forest, XGBoost) and analyzing their feature importances, as highlighted in reviews of advanced analytics in civil engineering [

19].

To provide evidence-based insights for policymakers, industry practitioners, and investors to foster sustainable and responsible development in the construction sector, contributing to sustainability assessment efforts [

11,

17].

1.8. Research Questions, Scope, and Outline

To guide the investigation towards achieving the aforementioned objectives, this study seeks to answer the following key research questions:

RQ1: Which specific ESG factors (environmental, social, governance) significantly influence the economic performance (measured by construction industry value added) at a national level over time, when analyzed using a Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) panel data model that accounts for unobserved country-specific and time-specific effects?

RQ2: How do country-level housing construction costs in 2022 correlate with, and how are they predicted by, contemporaneous national ESG profiles and overall construction industry value added, based on cross-sectional OLS regression and correlation analyses?

RQ3: According to machine learning models (Random Forest and XGBoost), what are the most influential predictors of construction industry value added when considering a broad spectrum of ESG and economic indicators, both with and without the inclusion of its lagged value?

This study focuses on national-level ESG indicators and their relationship with construction industry value added (analyzed globally over the period 2002-2021, resulting in 588 observations after preprocessing) and 2022 housing construction costs (based on CalcForge and World Bank data, resulting in 33 observations for the cross-sectional analysis). The analysis employs panel data econometrics (specifically, Two-Way Fixed Effects via LSDV, as other panel models like GMM and linearmodels' FE/RE encountered estimation issues) and machine learning (Random Forest, XGBoost) on data primarily from these sources. The main aim of this work is thus to provide a multi-faceted empirical analysis to illuminate these complex ESG-economic relationships. The principal conclusions from the Two-Way Fixed Effects model indicate that GDP Growth (Annual %) is a significant positive predictor of construction value added. The cross-sectional OLS regression suggests that Control of Corruption and Internet Users (% Pop..) are significant predictors of 2022 housing construction costs. Machine learning models highlighted the lagged dependent variable as the most dominant predictor of construction value added, with XGBoost (including the LDV) achieving the highest predictive accuracy. Limitations inherent to macro-level data, such as potential for omitted variables despite methodological controls, data availability for specific ESG metrics, and generalizability constraints due to the specific country sample and period, are acknowledged.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the Materials and Methods, which include data sources, variable descriptions, and analytical methodologies.

Section 3 summarizes the findings of the empirical analyses.

Section 4 addresses the results, their theoretical and practical consequences, and the study's limitations. Finally,

Section 5 presents the Conclusions, which summarize the important contributions and recommend future study possibilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Variable Description

The data utilized in this study were compiled from several established sources to construct both panel and cross-sectional datasets. The panel dataset covers the period 2009 to 2023, with country selection based on the consistent availability of data for key variables, resulting in 588 observations after preprocessing. The cross-sectional analysis focuses on the year 2022, with a sample of 33 countries determined by data availability.

2.1.1. Panel Data Variables

For the panel data analysis, the dependent variable was log_construction_value_added. This variable represents the natural logarithm of "Industry (including construction), value added (current US

$)" (Indicator: NV.IND.TOTL.CD), sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) that can be accessed at

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.TOTL.CD. The logarithmic transformation was applied to normalize its distribution, reduce potential issues of heteroscedasticity, and allow for the interpretation of estimated coefficients as approximate elasticities.

The independent variables for the panel data were primarily drawn from the World Bank ESG dataset that is available at

https://databank.worldbank.org/source/environment-social-and-governance?preview=on and the WDI that can be accessed at

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.TOTL.CD. The selection of each variable was guided by its theoretical relevance to construction value added or a specific ESG pillar. Environmental indicators included renewable_energy_consumption_pct_total (% of total final energy consumption), fossil_fuel_energy_consumption_pct_total (% of total), reflecting national environmental pressures [

1]. Social indicators incorporated metrics such as expenditure_on_education_pct_gdp (% of GDP), research_and_development_expenditure_pct_gdp (% of GDP), individuals_using_the_internet_pct_of_population (% of population), the gini_index (World Bank estimate), and income_share_held_by_lowest_20pct (%), as proxies for human capital, innovation, information access, and social equity relevant to the construction sector [

10,

37]. Governance indicators, namely control_of_corruption_estimate, rule_of_law_estimate, and political_stability_and_absence_of_violence_terrorism_estimate (all with estimates varying from approximately -2.5 to 2.5), were sourced from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) that can be accessed at

https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/, reflecting governance quality's impact on the investment climate and project risks [

7,

16]. Selected economic indicators from WDI, such as GDP growth, were also included.

Lagged variables were incorporated: LDV_log_construction_value_added (one-period lag of the dependent variable) was included to capture persistence. One-period lags of key ESG indicators were also considered to address potential endogeneity and account for delayed impacts.

2.1.2. Cross-Sectional Data Variables (2022)

For the cross-sectional analysis (year 2022), the dependent variable was Total_Housing_Cost_Per_M2, representing the average total housing construction cost per square meter, sourced from CalcForge that can be accessed at

https://calcforge.com/. Where multiple estimates were available per country, an average was utilized. Independent variables comprised contemporaneous (2022) values of selected national-level ESG indicators (a subset of those used in the panel, chosen for relevance to costs and 2022 data availability) and WB_ValueAdded_2022 (construction industry value added for 2022 from WDI that is available at

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.TOTL.CD).

2.2. Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing involved harmonizing country identifiers for merging. Missing data in both panel and cross-sectional datasets were handled using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) with the BayesianRidge estimator and 10 imputations (assuming 10 from your previous script; update if different). MICE algorithm convergence was visually monitored using trace plots for key imputed variables. (Based on your logs, it seems outlier treatment like winsorizing was planned but might not have been explicitly executed by the script provided. You need to confirm this. If it wasn't done, remove the sentence about outlier treatment or state "Outlier identification was performed using standard methods (e.g., Z-scores, IQR); however, systematic outlier treatment such as winsorizing was not applied in the final analysis presented." If it was done, specify: "Outliers identified using Z-scores exceeding ±3 were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate undue influence.")

The final panel dataset consisted of 45 countries over the period 2009–2023, yielding 588 observations. The cross-sectional sample comprised 33 countries for the year 2022.

2.3. Panel Data Analysis Methodology

Panel unit root tests (e.g., Levin-Lin-Chu, Im-Pesaran-Shin) were initially planned to assess variable stationarity. However, due to library import issues encountered during analysis, these tests could not be performed. Consequently, panel regression models were estimated using variables in their levels, a limitation further discussed.

Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF). An iterative pruning process removed variables exceeding a VIF threshold of 5 until all remaining variables met this criterion.

Static panel models—Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects (FE), and Random Effects (RE)—were estimated. Due to estimation failures with linearmodels for FE and RE specifications (see Results section), FE models were implemented using the Least Squares Dummy Variable (LSDV) approach with statsmodels. Model selection between Pooled OLS and FE specifications was guided by an F-test for individual and/or time effects.

Dynamic panel data models, specifically the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), were initially considered the primary approach to address Nickell bias and potential endogeneity. However, due to library import failures for the required GMM package, this analysis could not be executed. The study therefore relied on the Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) model, which controls for unobserved time-invariant country-specific heterogeneity and common time shocks, while acknowledging that certain endogeneity concerns might not be as comprehensively addressed as with a GMM estimator.

2.4. Cross-Sectional Data Analysis Methodology (2022)

For the 2022 cross-sectional data, after MICE imputation and VIF pruning (threshold of 5), Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was employed with Total_Housing_Cost_Per_M2 as the dependent variable. Independent variables were standardized (mean 0, standard deviation 1) before OLS estimation to allow for comparison of coefficient magnitudes. Robust standard errors (HC3) were used to account for potential heteroscedasticity. A Pearson correlation matrix was also computed to examine bivariate relationships.

2.5. Machine Learning Methodology (Complementary Analysis for Panel Data)

Machine learning (ML) served an exploratory purpose to identify important predictors of log_construction_value_added from the panel data and assess predictive performance. Random Forest (RF) Regressor and XGBoost Regressor were chosen [

19]. The final panel dataset (after MICE and VIF pruning), including LDV_log_construction_value_added and relevant lags, was used. An 80% training and 20% testing split was applied. Hyperparameters for RF and XGBoost were tuned using GridSearchCV with 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. Performance was evaluated using Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared (R²), and feature importances were extracted.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical findings from the panel data analysis of construction industry value added, the cross-sectional analysis of 2022 housing construction costs, and the complementary machine learning models.

3.1. Panel Data Regression Results

The panel dataset, after preprocessing including MICE imputation for missing values and VIF-based pruning for multicollinearity, comprised 588 observations. The VIF pruning process led to the removal of several variables (e.g., 'R&D Exp. (L1, % GDP)', 'Voice and Accountability', 'Control of Corruption', 'Rule of Law (L1)', 'Poli. Stability (L1)', 'Rule of Law', 'Income Share Low 20% (L1)', 'Econ. & Soc. Rights (L1)', and 'Ctrl. Corruption (L1)', ensuring that remaining predictors had VIF scores below the threshold of 5 (Max VIF: 4.28), mitigating concerns of severe multicollinearity.

3.1.1. Panel Model Selection and Preferred Model

Initial attempts to estimate Fixed Effects (FE) and Random Effects (RE) models using the linearmodels package, as well as GMM models (due to pyeconometrics import failure), encountered estimation issues (see log: "The truth value of a Series is ambiguous" for linearmodels; GMM skipped). Consequently, a Pooled OLS model was estimated using linearmodels, and FE models were estimated using the Least Squares Dummy Variable (LSDV) approach with statsmodels.

Model selection tests were conducted to determine the most appropriate static panel specification (

Table 1). The F-test for poolability, comparing Pooled OLS with a Fixed Effects specification, was inconclusive ("Models not comparable"). However, the F-test for time effects, comparing an entity-only FE model against a Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) model, yielded a highly significant result (F(12, 510) = 32.08, p < 0.001). This indicates that time-specific unobserved effects are jointly significant and that a TWFE model is preferred over an entity-only FE model. Given the inconclusiveness of the poolability test and the failure of the linearmodels RE model (preventing a Hausman test), the TWFE (LSDV) model emerges as the most robust and appropriate specification for analyzing the panel data.

3.1.2. Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) Model Results

The results for the preferred Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV statsmodels) model are presented in

Table 2. This model controls for both unobserved country-specific fixed effects and year-specific fixed effects.

From the Two-Way Fixed Effects model (

Table 2), GDP Growth (Annual %) emerges as a statistically significant positive predictor of the logarithm of construction industry value added (Coef. = 0.01, p = 0.02). This suggests that, controlling for country-specific and year-specific unobserved effects, a one-percentage-point increase in annual GDP growth is associated with approximately a 0.01% increase in construction value added. Most of the direct ESG indicators included in this specification, after accounting for fixed effects and VIF pruning, do not show statistically significant relationships with construction value added at conventional levels. The high R-squared (0.99) is characteristic of models with many dummy variables (entity and time effects), indicating a good fit in explaining within-sample variation largely due to these fixed effects.

The Pooled OLS (linearmodels) results are presented for completeness (

Table 3), though this specification is likely misspecified due to unaddressed heterogeneity. It showed nominal significance for 'Fossil Fuel Energy Cons. (% Total)' and 'Renewable Energy Cons. (%)'.

3.2. Cross-Sectional Analysis Results (2022 Housing Costs)

The cross-sectional analysis for the year 2022 involved 33 countries after data merging, MICE imputation, and VIF pruning.

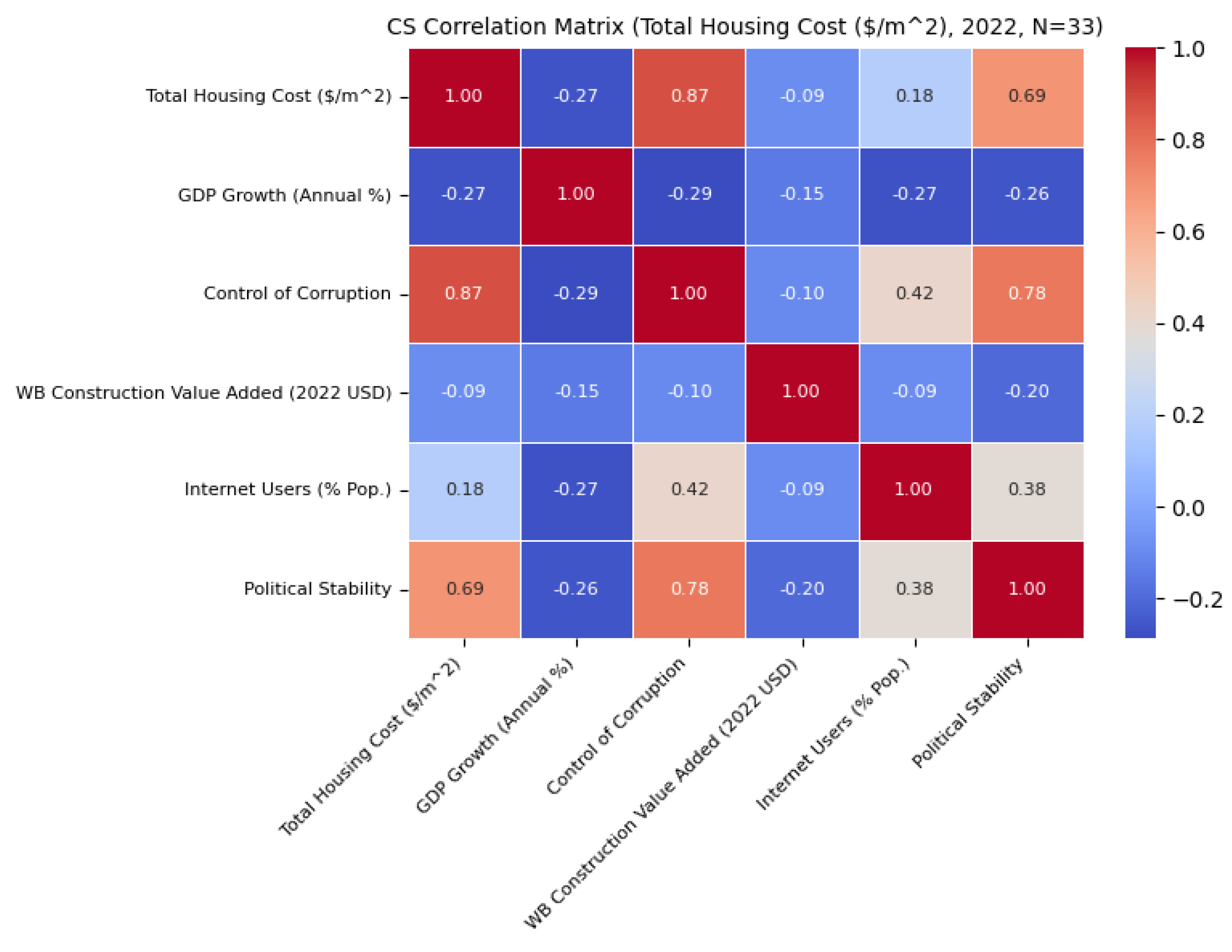

The correlation analysis (

Figure 1) indicates strong positive correlations between housing construction costs and 'Control of Corruption' (0.87) and 'Political Stability' (0.69). A moderate negative correlation is observed with 'GDP Growth (Annual %)' (-0.27), while 'Internet Users (% Pop.)' shows a weak positive correlation (0.18) and 'WB Construction Value Added (2022 USD)' shows a weak negative correlation (-0.09).

The OLS regression results for 2022 housing construction costs, using scaled independent variables for comparability of coefficients, are shown in

Table 4. The model explains a substantial portion of the variance (R-squared = 0.81, Adjusted R-squared = 0.78).

The OLS results indicate that higher Control of Corruption is significantly associated with higher housing construction costs (Coef. = 1445.33, p < 0.001). Conversely, higher Internet Users (% Pop.) is significantly associated with lower housing construction costs (Coef. = -376.95, p < 0.001). GDP growth, World Bank construction value added for 2022, and political stability did not show a statistically significant relationship with housing costs in this multivariate model, despite some correlations observed in the bivariate analysis.

3.3. Machine Learning Results (Panel Data for Log Construction Value Added)

Machine learning models were employed to explore predictive relationships for log construction value added using the panel data.

3.3.1. Model Performance

Table 5 summarizes the performance of Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost regressors, both with and without the lagged dependent variable (LDV) as a predictor. Models including the LDV achieved exceptionally high predictive accuracy on the test set (R² ≈ 0.99-1.00). Models without the LDV still showed strong performance (R² ≈ 0.80-0.82), indicating that other ESG and economic factors possess considerable predictive power.

3.3.2. Feature Importances

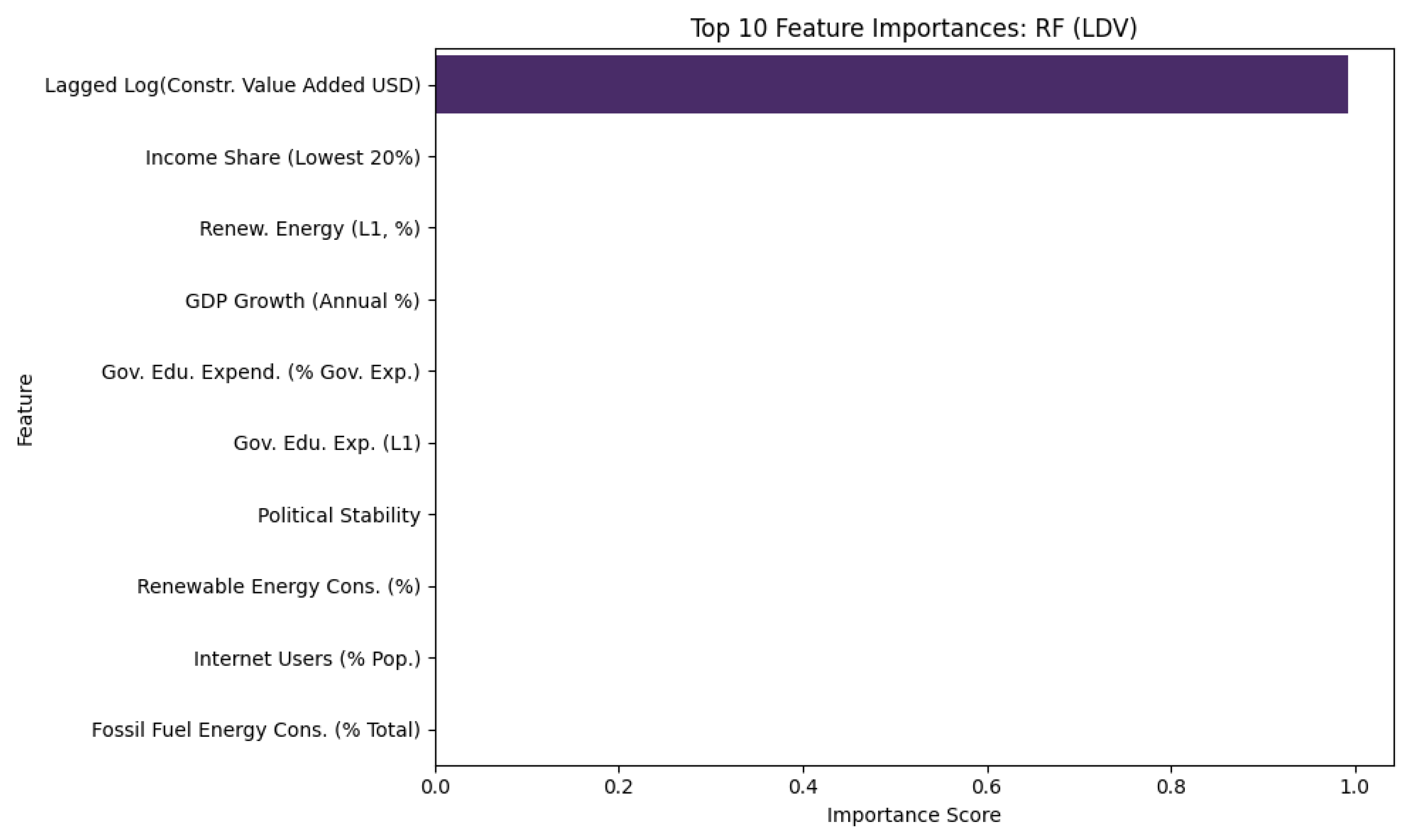

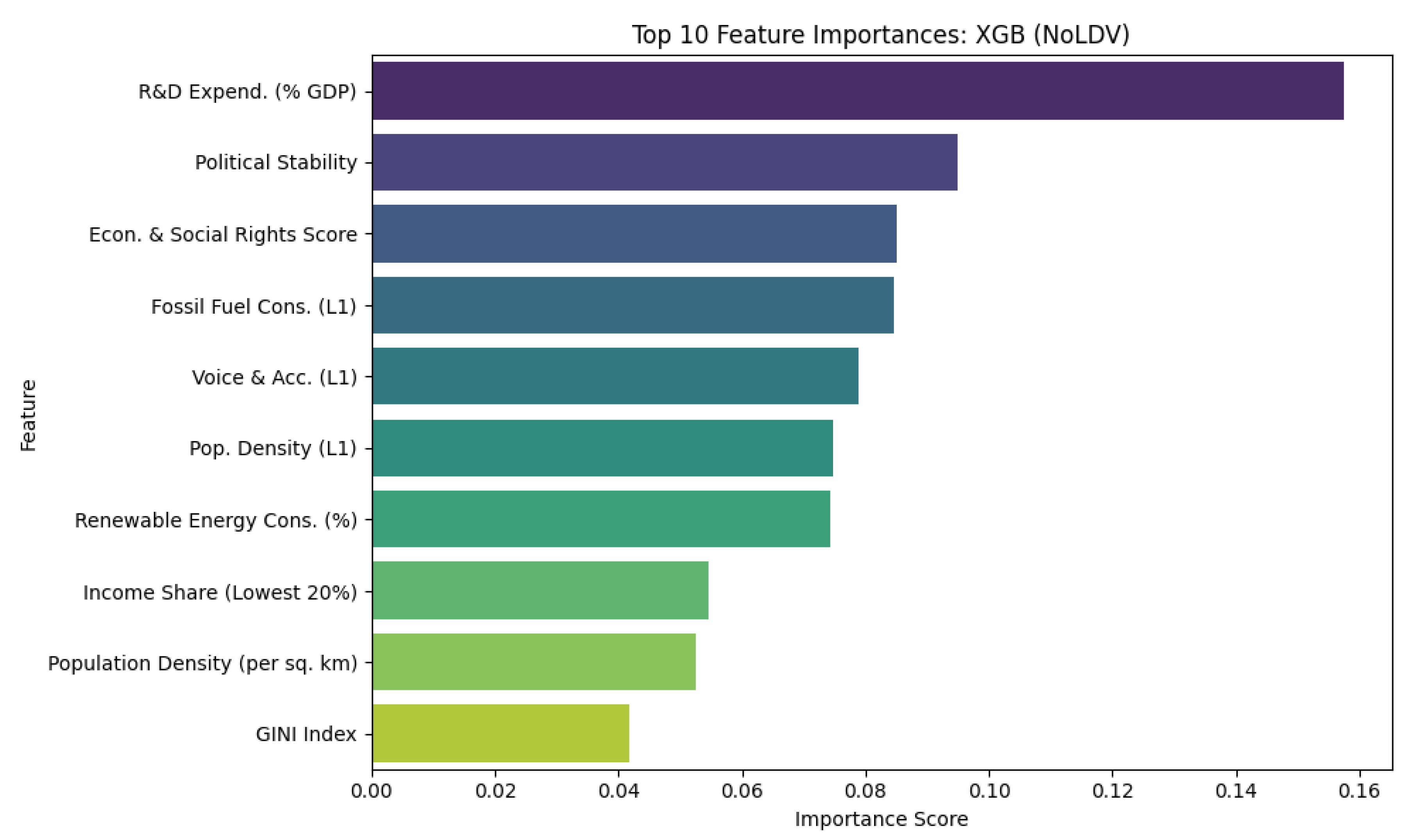

Feature importances were extracted from the trained models (

Table 6 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). As expected, when included, the Lagged Log (Constr. Value Added USD) was by far the most important feature in both RF (LDV) (Importance ≈ 0.992) and XGBoost (LDV) (Importance ≈ 0.956) models. This underscores the strong persistence and autoregressive nature of construction industry value added.

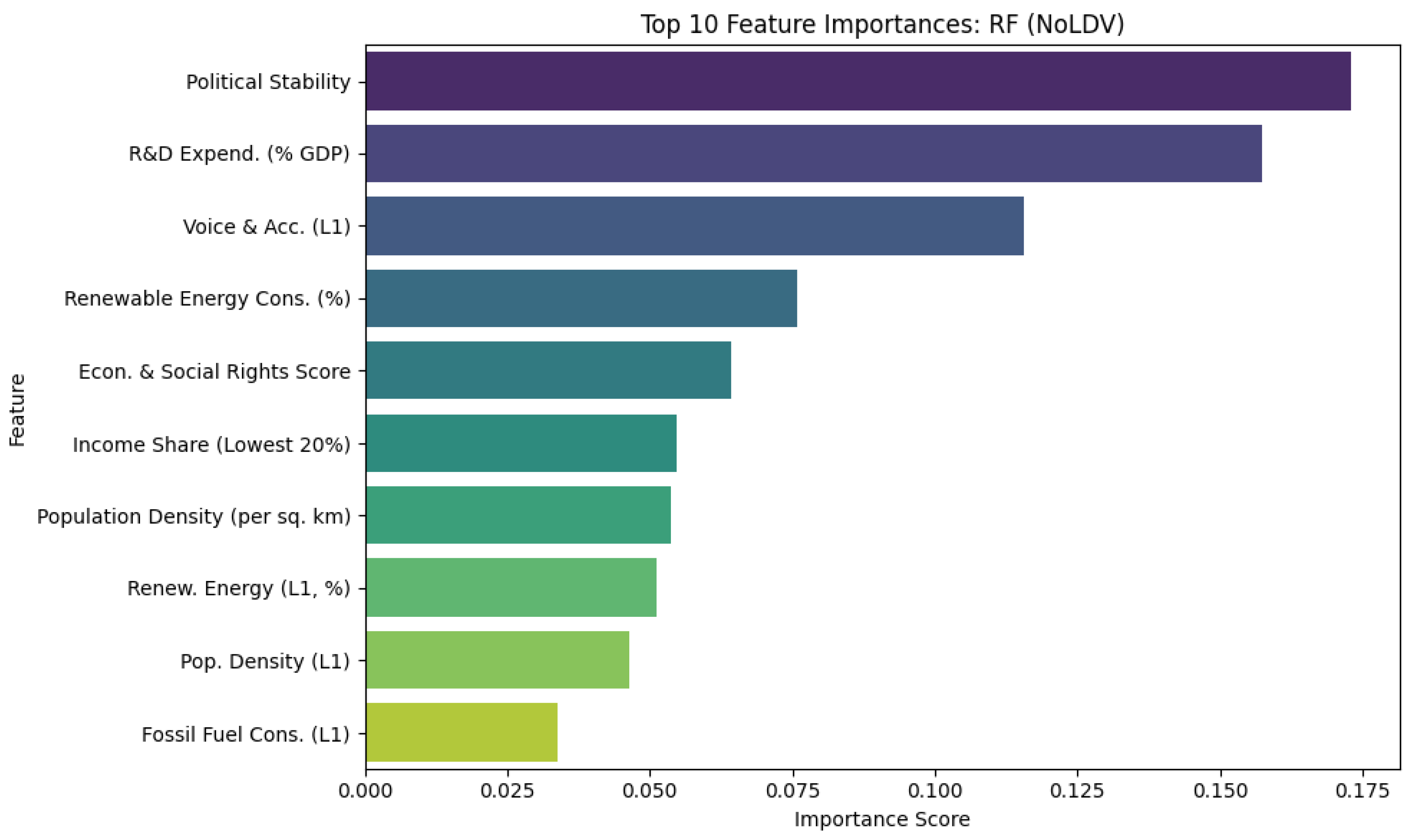

When the LDV was excluded (

Table 6,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), other features gained prominence. For the Random Forest (NoLDV) model, Political Stability (Importance ≈ 0.173) and Voice & Acc. (L1) (Importance ≈ 0.116) were among the top predictors. For XGBoost (NoLDV), Political Stability (Importance ≈ 0.095), Econ. & Social Rights Score (Importance ≈ 0.085), and Fossil Fuel Cons. (L1) (Importance ≈ 0.085) were highly ranked. These results suggest that governance and social factors, along with energy consumption patterns, are considered important by the ML models in predicting construction value added in the absence of its direct lag.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to empirically investigate the impact of national-level ESG performance on key economic indicators in the global construction industry, utilizing panel data econometrics, cross-sectional analysis, and machine learning techniques. The findings offer several insights, albeit with considerations due to methodological limitations encountered during the analysis, such as the inability to perform GMM or robustly run all linearmodels specifications.

4.1. Interpretation of Key Findings Concerning Research Questions

RQ1: Which Specific ESG Factors Significantly Influence Construction Industry Value Added over Time?

The preferred Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) panel model (

Table 2) indicated that, after controlling for unobserved country and time heterogeneity, GDP Growth (Annual %) was the primary statistically significant driver of construction industry value added among the included variables. A 1% increase in GDP growth was associated with a 0.01% increase in construction value added. This finding aligns with established economic theory that overall economic expansion fuels demand and activity in the construction sector.

Notably, most individual ESG indicators in this TWFE specification did not exhibit statistically significant effects on construction value added. This could be due to several reasons: (i) the strong control imposed by country and time fixed effects absorbing much of the variation attributable to slowly changing national ESG characteristics or common global ESG trends; (ii) multicollinearity having already removed some key correlated ESG indicators during VIF pruning (e.g., 'Control of Corruption', 'Rule of Law'); (iii) the true impact of some national-level ESG factors on aggregate construction value added being diffuse or having longer lag structures than captured; or (iv) the level of aggregation (national ESG to national industry value added) masking more nuanced project-level or firm-level impacts. The failure of the GMM approach, which could have better addressed endogeneity and dynamics for ESG variables, also limits definitive causal claims for these ESG factors from the panel econometrics. The Pooled OLS results (

Table 3) hinted at potential roles for energy consumption patterns, but these are not robust to the inclusion of fixed effects.

RQ2: How Do 2022 Housing Construction Costs Correlate with Contemporaneous ESG Profiles and Construction Value Added?

The cross-sectional analysis for 2022 (N=33) provided insights into the correlates of housing construction costs (

Table 4,

Figure 1). Control of Corruption showed a strong positive and significant association with higher housing costs. This suggests that in countries with better control over corruption, housing construction might involve more transparent processes, adherence to stricter codes, and potentially higher quality (and thus costlier) inputs, or less illicit cost-cutting. Conversely, higher Internet Users (% Pop.) was significantly associated with lower housing construction costs. This could reflect greater access to information, more competitive sourcing of materials and labor, increased efficiency through digital tools in project management, or broader economic development aspects correlated with internet penetration that also influence cost structures.

Political stability showed a strong positive bivariate correlation with costs but was not significant in the multivariate OLS model, suggesting its effect might be captured by or confounded with other variables like control of corruption. WB Construction Value Added (2022) and GDP Growth (2022) did not emerge as significant predictors of housing costs in the OLS model for this sample, indicating that at this specific point in time and for this set of countries, other factors, particularly governance quality (control of corruption) and digitalization (internet users), were more prominent direct statistical correlates.

RQ3: What Are the Most Influential Predictors of Construction Industry Value Added According to Econometric and ML Models?

The econometric Two-Way Fixed Effects model (

Table 2) identified GDP Growth (Annual %) as the key significant predictor after accounting for fixed effects.

The machine learning models (

Table 5 and

Table 6,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) offered a different perspective, primarily focused on predictive power. When the Lagged Log (Constr. Value Added USD) was included, it overwhelmingly dominated as the most important feature for both Random Forest and XGBoost, achieving near-perfect R² values on the test set. This is expected and highlights the strong autoregressive nature (persistence) of construction value added: past performance is a powerful predictor of current performance.

When the lagged dependent variable was excluded from ML models, Political Stability emerged as a prominent predictor in both RF and XGBoost. Other important features included Voice & Acc. (L1), Econ. & Social Rights Score, Renewable Energy Cons. (%), and various energy/resource use indicators, though their relative importance varied between RF and XGBoost. This suggests that in the absence of direct historical performance data (the LDV), ML models pick up signals from governance, social well-being, and environmental/energy profiles to predict construction value added. The difference in significant variables between the TWFE econometric model (emphasizing GDP growth) and the ML (No LDV) models (emphasizing governance/social/energy) highlights the different strengths of these approaches: econometrics for ceteris paribus effects under specific assumptions, and ML for overall predictive patterning, potentially capturing complex non-linearities and interactions that the linear fixed effects model might not. The ML results, particularly the high importance of political stability when LDV is excluded, align with the theoretical understanding that a stable governance environment is crucial for long-term investment and activity in capital-intensive sectors like construction [

7,

16].

4.2. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study offer nuanced insights for established theories relevant to ESG in the construction sector. Regarding Institutional Theory, the strong and significant positive association observed between 'Control of Corruption' and housing construction costs in the 2022 cross-sectional analysis lends empirical support to its tenets [

3,

6,

7,

43]. This suggests that national contexts with stronger institutional environments, characterized by less corruption, tend to exhibit different, and in this case higher, construction cost structures, potentially reflecting more formalized processes, adherence to stricter building codes and quality standards, or reduced opportunities for illicit cost-cutting measures often associated with weaker governance. However, the lack of broadly significant direct effects of many ESG indicators on aggregate construction value added in the preferred Two-Way Fixed Effects panel model, after controlling for unobserved country and time heterogeneity, presents a more complex picture. This may imply that while institutional pressures undoubtedly drive the adoption of ESG practices at various levels, their direct, separable impact on national-level industry value added is intricate. Such impacts might be absorbed by the unobserved fixed effects, mediated through broader macroeconomic conditions like GDP growth, or require longer time lags to manifest significantly at the aggregate level. Consequently, Institutional Theory might be extended by further considering the varying effectiveness of institutional pressures in translating ESG adoption into discernible macroeconomic benefits across diverse national and temporal contexts.

Concerning Sustainability Assessment Frameworks and C-ESG concepts, this research underscores the inherent challenge of directly linking macro-level ESG indicators to aggregate economic outcomes such as national construction value added. While frameworks like Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) [

11,

14,

30,

34,

35] and the principles of Construction Project Level-based ESG (C-ESG) [

8,

13,

15] rightly emphasize the importance of ESG integration at the project and firm levels, the signals from national-level ESG indicators might be too aggregated or confounded by numerous other factors to show strong, isolated effects on broad industry performance metrics. Nevertheless, specific findings, such as the significant negative relationship between 'Internet Users (% Pop.)'—a social and enabling factor and housing construction costs, can inform the social dimensions within these assessment frameworks. This particular result highlights the potential role of digitalization and enhanced access to information in fostering more efficient and potentially lower-cost construction environments.

Overall, the results encourage a multi-level perspective when theorizing the ESG-economic nexus in construction. While national ESG profiles demonstrably correlate with specific outcomes like housing costs, their translation into industry-wide economic performance, such as value added, appears heavily influenced by overarching macroeconomic conditions (evidenced by the significance of GDP growth) and strong path dependency (indicated by the high predictive power of the lagged dependent variable in machine learning models). This suggests that theories linking ESG to economic performance in the construction sector should carefully consider the level of analysis (project, firm, industry, national) and the crucial mediating roles of broader economic and institutional contexts.

4.3. Practical and Policy Implications

The empirical results of this study provide several actionable insights for various stakeholders involved in the construction industry.

4.3.1. For Policymakers

The consistent significance of GDP growth in the panel model for construction value added underscores that stable macroeconomic policies fostering overall economic expansion remain fundamental for a thriving construction sector. Beyond general economic health, the cross-sectional finding linking higher 'Control of Corruption' to different housing cost structures (in this case, higher, potentially formal costs) highlights the critical importance of sustained anti-corruption measures and the continuous strengthening of governance institutions to influence construction market transparency and potentially affordability in the long run [

15,

16]. Furthermore, the observed negative association between 'Internet Users (% Pop.)' and housing costs suggests that public policies promoting digitalization, improving digital literacy, and ensuring widespread access to information could contribute significantly to creating more efficient and potentially lower-cost construction ecosystems [

19,

24]. Although direct links between many national-level ESG factors and aggregate construction value added were not broadly statistically significant in the preferred panel model after accounting for fixed effects, this does not diminish the intrinsic importance of ESG. It may imply that the economic benefits of ESG at the macro industry level are either realized over longer time horizons, are indirect, or are more readily captured through specific project-level or firm-level analyses. Therefore, policies should continue to encourage comprehensive ESG adoption across the sector for its inherent environmental and social benefits, as well as its potential for long-term risk mitigation and alignment with sustainable development goals [

1,

5,

27].

4.3.2. For Construction Companies and Industry Practitioners

The high predictive importance of the lagged dependent variable (past performance) in the machine learning models for construction value added suggests that established companies with strong operational track records and market positions are likely to maintain their performance trajectories. For new entrants or firms seeking substantial improvement, a foundational focus on operational excellence, efficiency, and robust project management is paramount. The machine learning models, when excluding the direct lag of value added, pointed to factors like 'Political Stability', 'Voice & Accountability', and 'Economic & Social Rights' as notable predictors. This implies that operating within stable, well-governed national environments that uphold strong social frameworks can be more conducive to sustained industry performance, a factor companies should actively consider in their country-level risk assessments and strategic planning. Additionally, the observed link between lower housing construction costs and higher national internet penetration presents a clear opportunity for firms to increasingly leverage digital technologies such as Building Information Modeling (BIM), Internet of Things (IoT), and Artificial Intelligence (AI), as discussed extensively in recent literature [

12,

19,

22,

25]—to achieve significant efficiency gains, optimize resource allocation, and potentially reduce project costs.

4.3.3. For Investors

The findings of this research offer pertinent information for guiding investment decisions within the construction sector. The importance of macroeconomic stability, particularly GDP growth, is reaffirmed as a key indicator for assessing the potential of construction sector investments. The significant relationship between 'Control of Corruption' and housing construction costs underscores that governance quality is a critical due diligence factor for investors; investments in countries with stronger governance may encounter different (potentially higher and more formal) cost structures but could also benefit from lower risks associated with corruption and greater transparency. While this macro-level study did not find widespread, direct, and statistically significant impacts of many ESG indicators on aggregate construction value added within the stringent Two-Way Fixed Effects panel model, investors should not discount the importance of ESG. ESG considerations remain crucial for comprehensive risk management, long-term value preservation, and alignment with evolving sustainability mandates and stakeholder expectations [

15,

16,

17], as project-level or firm-level ESG performance can still yield significant financial and non-financial benefits not fully captured at the national aggregate level.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

This study's multi-method empirical investigation into the ESG-economic nexus in construction is subject to several limitations that warrant consideration when interpreting its findings.

First, data-related constraints are inherent. The reliance on national-level aggregate data for ESG indicators and economic outcomes may obscure significant heterogeneity and direct impact relationships present at sub-national, firm, or project levels, where ESG practices are operationalized. The consistent availability and granularity of specific ESG metrics across a global panel are limited, potentially omitting nuanced aspects of construction-relevant ESG performance; for instance, 'Literacy Rate' variables were excluded due to substantial missing data. Furthermore, the cross-sectional housing cost data (CalcForge, N=33 for 2022) restricts the generalizability of these specific findings and precludes analysis of cost dynamics over time.

Second, methodological limitations are present. The inability to conduct panel unit root tests, due to library import issues, means the stationarity of the panel series is unconfirmed, a significant caveat as regressions on level variables could be spurious if non-stationarity is not addressed. The failure of GMM estimation, intended for robust endogeneity and dynamic panel bias management, means the preferred Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) model, while controlling for unobserved heterogeneity, may still be susceptible to endogeneity from time-varying omitted variables. The cross-sectional OLS analysis establishes correlations, not causality. Additionally, while MICE was used for missing data, its validity depends on data being missing at random, and violations of this assumption could introduce bias.

Finally, regarding originality and generalizability, this study contributes by applying a multi-faceted analytical approach (panel, cross-section, ML) to link a broad set of ESG indicators with construction value added and housing costs, an area still developing comprehensive global empirical evidence. However, the findings are specific to the analyzed sample and period.

4.5. Future Research Directions

Building upon the findings and limitations of this study, several avenues for future research emerge that could further enhance the understanding of ESG's role in the construction industry.

A crucial area is data enhancement. Future efforts should prioritize the collection of more granular data, specifically project-level or firm-level ESG performance metrics within the construction sector across diverse geographical contexts. Such data would allow for more direct and nuanced testing of ESG impacts, moving beyond national-level proxies. Concurrently, the development and adoption of more standardized and widely available national-level ESG indicators that are specifically tailored to the unique characteristics and impacts of the construction industry would be highly beneficial.

In terms of advanced econometrics, future studies should aim to overcome challenges with GMM estimation or explore other sophisticated panel techniques, such as panel Vector Autoregression (VAR) models or dynamic common correlated effects (DCCE) models, which could provide deeper insights into causal relationships and complex dynamic interplay between ESG factors and economic outcomes. Critically, thoroughly addressing variable stationarity through appropriate panel unit root testing and subsequent methodological adjustments (e.g., differencing, error correction models, or panel cointegration analysis) is paramount for the robustness of future econometric work in this area.

Future research could also benefit from exploring nuances in the ESG-economic relationship. This includes investigating potential non-linear relationships, where the impact of an ESG factor might change at different levels of that factor or economic development, and examining interaction effects between various ESG dimensions or between ESG factors and other country-specific characteristics (e.g., do governance improvements have a more pronounced impact on construction value added in countries with lower initial social development scores?).

To complement quantitative findings, qualitative insights derived from case studies of construction projects or firms in diverse national contexts could be invaluable. Such research could help uncover the specific mechanisms, decision-making processes, and contextual factors that mediate the pathways through which ESG considerations influence economic and operational outcomes in the construction industry.

Lastly, the role of technological integration warrants continued investigation. Further research is needed to rigorously quantify the economic and ESG benefits derived from the adoption and effective implementation of technologies like BIM, IoT, AI, and Digital Twins in construction operations, particularly in their capacity to foster resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the broader principles of a Circular Economy [

19,

20,

22,

25,

30]. This could involve developing specific metrics and models to track the lifecycle impacts and returns on investment for these technology-driven sustainability initiatives.

5. Conclusions

This study embarked on an empirical investigation into the complex interplay between national-level ESG performance and key economic indicators within the global construction sector. The primary objectives were to analyze the dynamic relationship between ESG indicators and construction industry value added using panel data, explore the correlates of 2022 housing construction costs through cross-sectional analysis, and identify influential predictors using complementary machine learning techniques.

The panel data analysis, relying on a Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV) model due to estimation challenges with other advanced methods, revealed that GDP Growth (Annual %) was a significant positive driver of construction industry value added. Most individual ESG indicators, after controlling for fixed effects, did not show statistically significant direct impacts on aggregate value added in this stringent model, suggesting their influence might be indirect, long-term, or more apparent at different levels of analysis.

The cross-sectional analysis of 2022 housing construction costs indicated that stronger Control of Corruption was associated with higher costs, potentially reflecting more formal and transparent processes, while higher Internet Users (% Pop.) was linked to lower costs, possibly due to increased efficiency and access to information.

Machine learning models demonstrated that the lagged value of construction value added is an overwhelmingly dominant predictor, highlighting strong industry persistence. When this lag was excluded, factors related to Political Stability, Voice and Accountability, and Economic & Social Rights emerged as important predictors, underscoring the relevance of stable socio-political environments.

This study contributes by providing a multi-method empirical examination using global datasets, offering nuanced insights despite data and methodological limitations. The findings underscore that while broad economic conditions and industry persistence are strong drivers, specific governance aspects (like corruption control) and enabling social factors (like internet penetration) are significantly correlated with construction sector economics at the national level. While the direct link from a wide array of national ESG indicators to aggregate construction value added was not broadly evident in the most robust panel model available, the importance of ESG for risk management, project-level efficiencies, and broader sustainable development remains. Future research should focus on more granular data and advanced econometric techniques to further disentangle these complex relationships and solidify the evidence base for ESG's multifaceted role in shaping a sustainable and resilient global construction industry.

6. Patents

There are no patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Figure 1: Correlation of Key Variables with Total Housing Cost per Square Meter (2022, N=33).;

Table 1: Panel Model Selection Test Summary.;

Table 2: Two-Way Fixed Effects (LSDV statsmodels) Panel Regression Summary for Log (Construction Value Added USD).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E.O.O.; methodology, H.E.O.O.; software, H.E.O.O.; validation, H.E.O.O.; formal analysis, H.E.O.O.; investigation, H.E.O.O.; resources, H.E.O.O.; data curation, H.E.O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.E.O.O.; writing—review and editing, H.E.O.O.; visualization, H.E.O.O.; supervision, H.E.O.O.; project administration, H.E.O.O.; funding acquisition, H.E.O.O. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study, including the Python scripts used for analysis and the generated panel datasets, are available within the article or as supplementary material associated with this publication and will be made available as supplementary material on the publisher's website upon publication.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

|

CE

|

Circular Economy

|

|

ESG

|

Environmental, Social, and Governance

|

| GMM |

Generalized Method of Moments |

| WDI |

World Development Indicators |

| WGI |

Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| NDT |

Non-Destructive Testing |

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| FEED |

Front-End Engineering Design |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Squares |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

| MICE |

Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| LDV |

Lagged Dependent Variable |

References

- Tanui, S.J.; Tembo, M. An exploration of the extent of monitoring and evaluation of sustainable construction in Kenya: A landscape architecture perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Caselles, L.M.; Guevara, J. Sustainability performance in on-site construction processes: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.W.; Yan, Y.; Pan, J.; Wu, K.S. Antecedents and consequences of sustainable project management: evidence from the construction industry in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan-Danila, L.; Grigoras-Ichim, C.E.; Jeflea, F.V.; Barbuta-Miscǎ, I. Assessing the Sustainability of Construction Companies in Digital Context: An Econometric Approach Based on Financial, Social, and Environmental Indicators. Preprints.org 2025. 2025040822 (preprint). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadazdi, A.; Naunovic, Z.; Ivanisevic, N. Circular economy in construction and demolition waste management in the western balkans: A sustainability assessment framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, S.; Nani, G.; Ayarkwa, J. Contractors' adaptation to environmentally sustainable construction: a micro-level implementation framework. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 11, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiong, H.; Wang, G.; Jiang, P. How institutional pressures improve environmental management performance in construction projects: an agent-based simulation approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 8539–8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, M.; Antony, J.; Nair, G.; Anshari, S. Lean-sustainability assessment framework development: evidence from the construction industry. Int. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. 2023, 34, 2046–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, R. An integrated social sustainability assessment framework: the case of the construction industry. Open House Int. 2023, 48, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmu, A.W.; Shooshtarian, S.; Mahmood, M.N.; Sivam, A.; Rameezdeen, R. The state of play regarding the social sustainability of the construction industry: A systematic review. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 2125–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Yi, X.; Liu, Y. Sustainability assessment of small hydropower from an ESG perspective: A case study of the Qin-Ba Mountains, China. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 350, 119523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, W.; Alias, A.H. Key Factors for Building Information Modelling Implementation in the Context of Environmental, Social, and Governance and Sustainable Development Goals Integration: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Tao, X.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Kwok, H.H.L.; Dai, J.; Cheng, J.C.P. Secure environmental, social, and governance (ESG) data management for construction projects using blockchain. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wu, L.; Zhao, W.; Ma, W.; Hao, J. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: An Index System for Building Energy Retrofit Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celoza, A.; Owens, V. Perspectives on ESG Materiality in the Engineering and Construction Industry: An Exploratory Study. J. Leg. Aff. Dispute Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2025, 17, 05025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zeng, S.; Peng, Q. The Mutual Relationships Between ESG, Total Factor Productivity (TFP), and Energy Efficiency (EE) for Chinese Listed Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Fan, M.; Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, Y. Path to Green Development: How Do ESG Ratings Affect Green Total Factor Productivity? Sustainability 2024, 16, 10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olumo, A.; Haas, C. Building material reuse: An optimization framework for sourcing new and reclaimed building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 479, 143892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, K. ICT-Driven Data Mining Analysis in Civil Engineering: A Scientometric Review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 15, e1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, S.R.; Singh, A.K.; Fazeli, A.; Banihashemi, S.; Arashpour, M.; Cheung, C.; Ejohwomu, O.; Zayed, T. Determining the stationary digital twins implementation barriers for sustainable construction projects. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, M.M.; Hollenbach, P.; Michalski, A.; Meyer, S.; Birle, E.; Off, R.; Lang, C.; Schmidt, W.; Cudmani, R.; Fritz, O.; Baltes, G.; Kortmann, G. The Industrialisation of Sustainable Construction: A Transdisciplinary Approach to the Large-Scale Introduction of Compacted Mineral Mixtures (CMMs) into Building Construction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Hou, L.; Zhang, G.; Tan, Y.; Mao, P. BIM and IFC Data Readiness for AI Integration in the Construction Industry: A Review Approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safhi, A.M.; Keserle, G.C.; Blanchard, S.C. AI-Driven Non-Destructive Testing Insights. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmousalami, H.; Maxy, M.; Hui, F.K.P.; Aye, L. AI in automated sustainable construction engineering management. Autom. Constr. 2025, 175, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuri, P.K.; Alkki, L.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L. Digital Technologies Enabling Component Reuse in Circular Value Chains: Using Digital Twin, Internet of Things and Robots in Construction and Manufacturing Sectors. R D Manag. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, A.; Castañeda, K.; Sánchez, O.; Peña, C.A.; Gutiérrez, L.; Sáenz, P. Building information modeling and complementary technologies in heritage buildings: A bibliometric analysis. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, T.; Chan, P.W. Forward and reverse logistics for circular economy in construction: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherman, I.-E.; Lakatos, E.-S.; Clinci, S.D.; Lungu, F.; Constandoiu, V.V.; Cioca, L.I.; Rada, E.C. Circularity Outlines in the Construction and Demolition Waste Management: A Literature Review. Recycling 2023, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukari, O.; Kassem, M.; Scoditti, E.; Aguejdad, R.; Greenwood, D. A BIM based tool for evaluating building renovation strategies: the case of three demonstration sites in different European countries. Constr. Innov. 2024, 24, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oditallah, M.; Alam, M.; Ekambaram, P.; Ranjha, S. Review and Insights Toward Cognitive Digital Twins in Pavement Assets for Construction 5.0. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A. Improving the decision-making for sustainable demolition waste management by combining a BIM-based life cycle sustainability assessment framework and hybrid MCDA approach. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasheminasab, H.; Gholipour, Y.; Kharrazi, M.; Streimikiene, D. A quantitative sustainability assessment framework for petroleum refinery projects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 15305–15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A. The development of an integrated BIM-based visual demolition waste management planning system for sustainability-oriented decision-making. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 351, 119856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjua, S.Y.; Sarker, P.K.; Biswas, W.K. Development of triple bottom line indicators for life cycle sustainability assessment of residential bulidings. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 264, 110476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava, S.; Chalabi, Z.; Bell, S.; Burman, E. A multistakeholder participatory Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment framework for the options appraisal of social housing regeneration schemes. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Alrasheed, K.A.; Khan, A.M.; Almujibah, H.; Benjeddou, O. Analyzing the impact of holistic building design on the process of lifecycle management of building structures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, V.; Mathieu, S.; Wardhani, R.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. Suicidal ideation and related factors in construction industry apprentices. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal, M.A. Challenges and political implications of sustainable maintenance in residential condominiums in Brazil: A life cycle perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 380, 125107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, L.F.; Mendes, L.P.T.; de Medeiros Melo Neto, O.; de Figueiredo Lopes Lucena, L.C.; de Figueiredo Lopes Lucena, L. Economic and environmental benefits of recycled asphalt mixtures: impact of reclaimed asphalt pavement and additives throughout the life cycle. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 11269–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, S.B.; de Bortoli, K.C.R.; Vasconcellos, P.B. Assessing the built environment resilience in Brazilian social housing: Challenges and reflections. Caminhos Geogr. 2023, 24, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Abdelhaffez, G.S.; Ahmed, A.A. Potential use of marble and granite solid wastes as environmentally friendly coarse particulate in civil constructions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laveglia, A.; Ukrainczyk, N.; De Belie, N.; Koenders, E. Cradle-to-grave environmental and economic sustainability of lime-based plasters manufactured with upcycled materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, D.; Prencipe, A.; Papa, A.; Corsi, C.; Sorrentino, M. Boosting circular economy via the B-Corporation roads. The effect of the entrepreneurial culture and exogenous factors on sustainability performance. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 523–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddingham, J.A.; Chandler, J.A.; Alexander, K.C.; Zafar, S.; Anglin, A. The leisure paradox for entrepreneurs: A neo-institutional theory perspective of disclosing leisure activities in crowdfunding pitches. J. Bus. Ventur. 2025, 40, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, B.; Anand, N.; Alengaram, U.J.; R, S.R.; Jayakumar, G. Promulgation of engineering and sustainable performances of self-compacting geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).