1. Introduction

I first provide an overview of some of the foundational ways of knowing, or principles and philosophy that underpin aspects of Ayurveda, modern medicine, and some basic sciences of interest. I discuss the specific approaches of systems biology, omics, and evidence-based, population-based, functional and integrative medicines, as they are applied to Ayurveda. I will give particular attention to proteomics, including the modification of proteins after they are synthesized. I also discuss how protein bioconformatics, which can be considered a special type of proteomics, differs from more conventional proteomics in principle, philosophy, and approach.

Secondly, I discuss what protein bioconformatics is, the foundational theoretical concepts supporting it, some of the techniques used to study it, and some of the insights it provides into the workings of cells and organisms. I include some of the principles and philosophy that contribute to aligning it with Ayurveda.

Thirdly, I consider how protein bioconformatics might be applied to exploring a variety of concepts and pathologies in Ayurveda. Concepts considered include the biophysiologic energy principle of Vata Dosha, pathogenesis (Samprapti), and individual variation. Turning to how protein bioconformatics might be applied to specific human pathologies, as conceptualized in both modern medicine and Ayurveda, I review two representative diseases: rabies/Alarkavisha, as an example in infectious diseases and neuroscience, and cancer/Arbuda, as an example in oncology and of unifying therapy across a disease category.

This information should be of interest to individuals from a variety of disciplines and backgrounds. It may inform Ayurvedic physicians and research scientists about the potential that the field of protein bioconformatics has for understanding and improving Ayurveda. It may provide scientist working in protein bioconformatics a roadmap for applying their methods to Ayurveda. It may be instructive to anyone interested in gaining a better understanding of how basic science can interface with Ayurveda. Finally, I hope it will offer at least one answer to the question posed at the outset: what might basic laboratory scientific research, carried out in a manner that is consistent with Ayurvedic principles, look like?

Many attempts have been made to integrate aspects of Ayurveda with aspects of

modern scientific medicine, with varying degrees of success [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. It has been asserted that while there is a need to explain Ayurveda in a modern context, and that much of modern research has not been very rewarding to Ayurveda [

7]. Many western scientific and medical research tools are poorly suited to studying Ayurveda. For example, the Western clinical trial models, that evaluate only one variable in an intervention, provide very little useful information when applied to a single aspect of what would otherwise be a multi-faceted Ayurvedic treatment program. Modern research methods which are based on structural concepts of organ-based anatomy and physiology also have limited utility when superimposed on Ayurveda’s more functional and holistic view of living processes. The biases of western scientific medicine often cause the individual variation in health, disease and treatment to remain unaddressed. Applying western chemistry to analyzing constituent molecules in complex plant-based medicines is also problematic from the Ayurvedic perspective. The classic example of the rise and fall of the Sarpagandha-derived constituent reserpine as drug therapy for hypertension illustrates this problem well [

8].

It has been recommended that researchers study Ayurveda as it is, as a whole system, in ways that conform to its principles and philosophy. Recognizing that “there is a strong need to explain fundamental principles of Ayurveda in a modern context” more collaboration with basic scientists has been recommended, as Ayurveda may be more explainable in the terms of basic science than in those of conventional biology and medicine [

7]. Conceptual scientific study of Ayurvedic basic concepts in the interest of creating an appropriate scientific interface was recommended towards the goal of describing “Ayurvedic biology” objectively. Ways of adopting and adapting technical tools from modern medical and basic science and applying them to Ayurveda in ways that are in tune with Ayurveda’s basic principles, has been envisioned [

7]. Protein bioconformatics, an emerging conceptual and experimental paradigm in modern biomedical science [

9,

10] has many characteristics that render it particularly suitable for application to Ayurveda. To elucidate this, the basic philosophy, key concepts and major techniques used in protein bioconformatics will be explained.

Protein bioconformatics will then be considered through two selected frameworks which evaluate integration with Ayurveda. Finally, concepts of protein bioconformatics and the Ayurvedic concepts of Dosha and Dosha imbalance will be applied to each other, to illustrate the potential for beneficial integration that protein bioconformatics could hold.

Methods

Multiple literature sources were reviewed for background. Classic Ayurvedic texts, including Caraka [

11] and Vagabhata [

12], modern texts [

13,

14], texts on cell biology and physiology [

15,

16] and works on the interface of Ayurveda and modern scientific medicine [

1,

17] were consulted. All known published literature to date on protein bioconformatics was reviewed, supplemented by unpublished documents and interviews with scientists in the field. Literature searches were performed on PubMed, Google scholar and DHARA (Digital Helpline for Ayurveda Research Articles). Key word searches included Ayurveda and omics, Ayurveda and neurodegeneration, protein bioconformatics, and non-covalent proteomics. Applicable references found through this literature were also reviewed. Materials were selected for review on the basis of their applicability to the topic.

To explore the interface of protein bioconformatics and Ayurveda, a series of thought experiments were performed. Thought experiments are a traditional method in philosophy and science in which one considers questions and hypotheses in light of different paradigms, and thinks through the consequences for each, looking at data and drawing inferences in new ways [

18]. The thought experiments performed explore the following two related questions: Can findings in protein bioconformatics elucidate concepts and processes in Ayurveda in ways that are consistent with Ayurvedic principles? How do the concepts of protein bioconformatics and of Dosha help inform each other? How does the concept of Dosha resonate with protein bioconformatics? The conclusion explores a final question: Does this analysis contribute to bridging Ayurveda and modern medical science?

Ayurveda and Modern Scientific Medicine: History, Philosophy and World Views

To set the context for addressing how protein bioconformatics might bridge Ayurveda and modern science, I will begin with a review of what some of the principals and methods of interest in both traditions. Starting with Ayurveda, I will review its Vedic roots, fundamental principles and approach to investigation. Continuing on to modern scientific medicine, I will consider also its roots and principles, and some approaches of particular applicability to our discussion. These include systems biology, the multiple fields now referred to as “omics”, and the concepts of evidence-based, individualized, functional and integrative medicines. Finally, I will review some of the published thinking about integrating Ayurveda and modern scientific medicine.

Vedic philosophy

In Sanskrit, Ayurveda means, approximately, the “science or knowledge of life”. It is a body of knowledge that relates to both healthy living and to the diagnosis and treatment of disease. The roots of Ayurveda probably grew out of the first civilizations in the Indus Valley, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, and were part of an oral tradition first appearing in compiled form in the Rg Veda, presumably around 1500 B.C. Veda means wisdom or knowledge in Sanskrit, and the Vedas are the earliest known compilations of this knowledge. The Atharva Veda, presumed 1200 B.C., most extensively addresses health and medical issues.

Vedic philosophy can be divided into six Darshanas, roughly translating as philosophical systems or world views. Originally, Darshana referred to inner and outer vision, or to the direct, intuitive experience of seeing reality on both the apparent and subtle levels [

13,

14]. Three of the Darshanas, Nyaya, Vaisheshika and Sankhya, are of particular interest to Ayurveda as they address the nature of the physical world in systematics ways. Nyaya articulates logical principles that form the basis for Ayurvedic epistemology. One of these principles is perception, which includes both ordinary sensory, and non-ordinary practiced intuition. Nyaya invokes consciousness behind the creation and processes of the universe. Vaisheshika discusses theoretical systems of the universe, including, in 600 B.C., the notion that the universe is composed of irreducible substances, atoms, which combine to form molecules, including the elements of ether, air, fire, water and earth.

Sankhya is the most central Darshana to Ayurveda, in part because its models of creation and composition of the universe form the basis for the Ayurvedic conceptualizations. The creation model outlines the manifestation of consciousness into matter. This begins with Avayakta, transcendental, unmanifest existence, which is made up of Purusha and unmanifest Prakruti. Purusha is indescribable, immaterial pure consciousness. Purusha is always unmanifest, and is close to the concept of Nirguna, something without characteristics or qualities. Prakruti in this creation model is triggered by Purusha to manifest as primordial material energy, with characteristics and qualities and with the potential to differentiate. Purusha and Prakruti combine to form Mahat, or supreme intelligence, without parameters, which manifests intelligence, explicitly, to the level of cells and elements. From Mahat flows Ahamkara, delineation into separate individuals with unique centers of perception. Mahat also differentiates into three Mahagunas (manifest energetic qualities), Sattva (spiritual light), Rajas (movement and excitation) and Tamas (inertia, darkness), which are universal and pervasive. The three Mahagunas are considered in some conceptualizations to be the irreducible substances likened to atoms [

13,

14,

19].

Ayurveda

After the Vedic period specific medical texts were composed, including the

Charaka Samhita, 760 B.C,

Sushruta Samhita, 600 B.C. and

Astanga Hrdayam, 600 A.D. These texts continue to be viewed as foundational to Ayurveda, and are considered by many to be a transmission of divine understanding [

14]. Modern Ayurveda continues to draw extensively from these texts, both directly, and by applying their principles to current circumstances.

There are several features and philosophical principles of Ayurveda particularly important to this discussion. Ayurveda is an experiential, empirical and logical science. It has a Vedic-based explicit epistemology, as stated in the

Charaka Samhita, Sutrasthana chapter 11, verse 17; “All can be divided into two – existent (manifest) and nonexistent (un-manifest). Their examination is fourfold - authoritative statement (Aptopadesha), perception (Pratyaksha), inference (Anumana) and rationale (Yukti).” [

11]

Authoritative statement is generally taken as meaning information or knowledge coming from classical texts or from spiritually pure, knowledgeable practitioners, if such can be found. Perception is keen observation of individual patients and the natural environment. Charaka continues in verse 17; “Inference is based on prior perception” [

11]. After gathering perceptive observational data, inference is inductive reasoning applied to generate hypotheses which might explain the data. These three principles of Ayurvedic epistemology are common to general Vedic philosophy and consistent with modern science [

20].

The fourth principle of Ayurvedic epistemology, Yukti, loosely translated as rationale, is subtler than the other three principles and more specific to Ayurveda. Yukti has less congruence with either general Vedic philosophy or modern scientific medicine. The Sanskrit root of Yukti is the same as that of Yoga, meaning to yoke or unite. Yukti describes the process of looking at multiple causative factors and generating the best explanation available for that specific context. A longer passage from the Charaka Samhita, Sutrasthana, chapter 11, verses 23-25, describes this:

(Through Yukti, the knowledge of) Water, plowing, and seed unite to make crops possible. Similarly, Yukti (helps us understand how) six tissues (Dhatus) unite to produce a foetus. (similarly wooden log, (the action of) churning, and the churning stick unite to make fire possible. Proper application of Yukti on the four limbs of therapeutics (patient, physician, caregiver and medicines) is necessary to alleviate illness.

(Yukti is the result of the) intellect that perceives reality as produced by multiple factors uniting. Yukti can be successfully applied to the three times (past, present and future) as also to the three types of knowledge (cause from effect, effect from cause; repeated observation) [

20].

Sanskrit translator and analyst Somik Raha characterizes Yukti as something akin to decision analysis (DA) in modern science and engineering [

20]. Decision analysis is a logic that combines knowledge from the literature with perception and inference to make good decisions. It is related to the probabilities generated through Bayesian inference, and is often inconsistent with the probabilities used in statistical hypothesis testing (SHT), the analytic tool most commonly used for randomized controlled trials (RTCs) in modern scientific medicine [

20].

The world view of Ayurveda embraces the concepts of unity and dynamism. In unity, the parts cannot be separated from the whole; everything is connected and such connections cannot be severed. One of the primary manifestations of unity is articulated through the relationship between the microcosm and the macrocosm. In particular, the life of an individual, and the life of the universe are directly correspondent, and perhaps one and the same. In dynamism, all of existence is in a state of constant and ever changing interaction. Specifically, Vata, Pitta and Kapha the three fundamental psychophysiological principals of Ayurveda known as Doshas, are in constant dynamic interplay [

14]. Ayurveda is profoundly respectful of the principals of both homeostasis, and of homeodynamics [

21], acknowledging that life works in both static and dynamic ways.

Ayurveda is sometimes referred to as traditional Indian science and medicine, though the more specific Sanskrit term Ayurveda is used here. Although based on classic texts, Ayurveda is by no means an unchanging discipline. Scholars, researchers and practitioners continue to adapt Ayurveda to the modern and global context on the basis of its principals, and in corroboration with newly generated data.

Modern scientific medicine

Modern scientific medicine is the dominant system of medicine in the West. Western medicine is often thought to originate around 460 B.C. with Hippocrates, and western science with around 384 B.C. with Aristotle. The ancient Greeks, like the ancient Indians, did not separate science and philosophy. They based their theories of medicine on direct clinical observation and included in their view of physiology a system of humors that have some correspondence to the Ayurvedic concept of Doshas. It is not known how much these concepts were influenced by the older Ayurvedic ideas, which trade and military activities may have provided some opportunity for dissemination [

14]. With Aristotle, western thinking began to separate empiric observation from experimental science, and to propose a reductionist view, that is, separating the parts from the whole [

1]. Around 200 A.D., Galen applied Aristotle’s method to medicine, placing more value on experimental than observational knowledge [

14].

The principle of the modern “scientific method” was articulated by Francis Bacon and others in the early 17

th century. It consists of four steps, observation, hypothesis formulation, hypothesis testing by experimentation, and induction. It derives general principles from observation and applies these to make predictions [

22]. The near exclusive reliance on this particular scientific method was forcefully imposed on medicine in the United States in 1910 by the use of a document entitled

Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching also known as the Flexner Report [

23]. Commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and written by Abraham Flexner, this report was heavily influenced by the American Medical Association. It’s adopted recommendations reformed medical education in the country, requiring medicals schools to conduct research and education in a scientific manner. It also forced the closure of institutions providing what was considered un-scientific education in health care, schools teaching the likes of naturopathy, herbology and midwifery, and provoked the closure of most of the schools training African Americans and women [

24].

The requirement that all medical training in the United States be based on experimental science created the conditions for the dominance of a medicine based on a predominantly reductionist, and thus not usually holistic, scientific approach. This dominance was further solidified with the discovery and dissemination of Penicillin and of sulfa drugs in the 1940s, which, for the first time, conferred a clear benefit to being treated by a trained medical doctor instead of another kind of healer. Many other powerful rescue treatments for severe pathology subsequently emerged through modern science and technology. An extreme characterization of the perspective of modern scientific medicine dominant in the 20th century is that the body is nothing more than the sum of its parts, and that the only information considered valid is that obtained through scientific experimentation. However, in recent decades, as the limitations and costs of this narrow view have become increasingly problematic, other approaches have garnered more serious interest in the world of modern scientific medicine.

Comparison of Ayurveda with modern scientific medicine

While not very different in their historical roots, Ayurveda and modern scientific medicine have diverged in several important ways over the centuries. Ayurveda has been relatively more holistic, viewing the parts and the whole as inseparable and their functioning irrevocably related. Ayurveda emphasizes supporting homeostasis and supporting the balance of the Doshas. Ayurveda sees the roots of illness in relatively subtle signs of imbalance and aims to prevent disease through addressing these imbalances, primarily through lifestyle adjustments and other natural methods. Ayurveda’s approach to knowledge is based on empiric observation applied to inductive reasoning, and on authoritative texts, themselves in part compendiums of observation and inductive reasoning.

Modern scientific medicine at least appears to be based on evidence generated through the systematic scientific testing of hypothesis. Thus, modern scientific medicine relies more on statistical analysis and deductive reasoning than Ayurveda does. Modern medicine tends to diagnose pathology only after concerning symptoms or test abnormalities appear. It often favors chemical suppressants as treatments, which seldom support homeostasis. Until recently, there has been little attention given in modern scientific medicine to the health effects of lifestyle. Instead of understanding physiology through the interplay of Doshas, modern scientific medicine favors observing and intervening in the functioning of biochemical molecules, organelles, cells, tissues and organs, often in isolation from the complex physiologic systems in which they live.

Some specific approaches of modern scientific medicine with applicability to Ayurveda

With the globalization and rising popularity of Ayurveda, techniques of modern science are increasingly being applied to Ayurveda. The reasons for this include explaining and validating Ayurveda in the modern context, applying Ayurvedic knowledge to drug discovery and integrated treatment strategies, and developing standardization and best practices in Ayurvedic care [

7]. The discussion here will focus primarily on applying modern science to explaining Ayurveda. For this purpose, there are several research approaches worth describing. In basic science these include Systems Biology and Omics. The clinical sciences of evidence-based, personalized, functional, and integrative medicines will also be discussed.

Systems biology

Systems Biology applies computational modeling to complex biological systems. It is considered more holistic than many other traditional approaches to biology because it studies complex interactions in a system, looking at the whole, while also looking at the parts. Through systems biology, for example, one can generate by computer a map depicting all known proteins in a cell that are associated with a specific process. Then connecting lines can be drawn between all the proteins known to interact with each other. The interactions between this set of proteins is known as the the

interactome for that process. Systems biology is of interest to Ayurvedic scientists largely because its holistic approach resonates with the Ayurvedic viewpoint, providing potential conceptual bridges. Patwardhan has applied a systems biology graphing technique to Ayurvedic concepts of biologic interactions, creating “Systems Ayurveda” graphics [

1].

Omics

The term omics refers to multiple fields of biology ending in –omics. They include genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. These are powerful tools of molecular and cell biology that have provided enormous amounts of information about the functioning of cells and organisms. Genomics looks at the sequences of nucleotides in Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), known as the genome, and how these sequences affect the structure and function of cells and organisms. When the human genome was first sequenced in 2001 there was eager speculation that this information might solve most remaining questions in human biology. To the contrary, the limitations of genomics have instead forced recognition that the genome is a considerably smaller part of the complex systems of human biology than previously assumed.

Epigenomics is the study of the epigenome, the next aspect of the cell’s information transfer process. It looks at modifications of DNA that don’t involve its sequence, such as methylation, which may render a gene silent. Transcriptomics studies the transcriptome, the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) that brings a transcribed copy of the DNA sequence out of the cell nucleus into the cytoplasm where protein sequences can be translated.

The study of protein structure and function is known as proteomics. Most often, it looks at the structure of amino acid sequences as translated from the mRNA, held together as a molecular chain by strong covalent bonds. Studying the modification of the protein after translation is another, less prominent, part of proteomics. Post-translational modifications after amino acid sequencing include attaching other substances, like phosphate, to the protein, the folding of the protein into complex shapes conferring specific functions, and the association of groups of proteins into large “multi-protein complexes”. The bonds holding the protein shape and the multi-protein complexes together are often weak non-covalent bonds. Research on protein folding and assembly into multi-protein complexes is referred to as post-translational proteomics, non-covalent proteomics, or protein bioconformatics. Protein bioconformatics will be discussed in greater detail in the next section. Metabolomics is the study of metabolites, smaller molecules produced by cellular processes and their interactions.

Omics and Ayurveda

Work done in omic sciences has generated large data bases which can be applied to many types of inquiry. Omic sciences are of interest to Ayurveda in several ways. Omic sciences can provide insight into and support for the Ayurvedic concept of individual variation, referred to as Prakruti. One of these approaches is called Ayurgenomics which correlates data from omic sciences with Ayurvedic concepts regarding the varied phenotypes of individuals and their diverse responses to diseases and medications [

25].

Metabolomics has been applied to understanding the metabolism of medications, both Ayurvedic and modern chemical. Pharmacogenomics looks at individual differences in response to medication, including Ayurvedic herbs and minerals. Metabolomics, which adds to the analysis the metabolites of the human microbiome, the microorganisms living in and on humans, is of interest to Ayurveda as it directly pertains to the Ayurvedic concern of maintaining healthy microbes in the gastrointestinal tract and elsewhere. Some scholars recommend applying omic and computational technologies to studying many Ayurvedic concepts, including Dosha, Prakruti, Guna (characteristics), Srotas (channels), and Agni (metabolic fire) [

1].

Personalized medicine

Assessing and treating each person as a unique individual is a core principle of Ayurveda. Charaka wrote, “Every individual is different from another; hence, each should be considered as a unique entity. As many variations as there are in the universe – all are seen in a human being” [

1]. Individual variation is also acknowledged in western medicine. From the time of Hippocrates, up through Sir William Osler, who claimed in 1892, that “if it were not for the great variability among individuals, medicine might as well be a science, and not an art” the unique individual has been a consideration in western medicine [

1]. In the past century, the way in which experimental science has been applied to modern medicine has created a tendency to downplay individual differences. In more recent decades, especially with new data emerging from the omic sciences, the interest in and ability to understand individual differences and personalize care has been increasing in modern scientific medicine. This has created a renewed alignment of modern scientific medicine with Ayurveda on the principal of personalization. Omic sciences can provide tools for Ayurveda to understand individual variation at the cellular and molecular level. Ayurveda can provide modern science a large body of observational and inductive data on individual variation that could help focus and direct research towards questions that are especially likely to have beneficial clinical applications.

Evidence-based medicine

In the past decades, leaders in modern scientific medicine have promoted evidenced-based medicine as the standard for high quality medical care. The term refers most often to the application of the results of research, particularly clinical epidemiology, and preferably randomized controlled trials (RTCs) to advise or determine clinical practice. Related trials are sometimes and further analyzed in groups as meta-analysis. Information on physiologic mechanisms gleaned from basic science research is often superimposed on associations observed in clinical epidemiology. This information is often used to claim biological plausibility or causality to the associations.

While the application of evidence-based medicine has greatly contributed to making the practice of medicine more rational and outcomes-focused, there are many limitations and flaws inherent in over-relying on this approach. RTCs often study only a single variable, such as one drug compared to a placebo or one dosage of a drug compared to another. Evaluating a comprehensive intervention such a set of Ayurvedic lifestyle recommendations, or a formula made of multiple plant medicines, is much more complicated, making such interventions difficult if not impossible to study in this way. Strict adherents of an evidence-based medicine that relies on RTCs will tend to discredit interventions which haven’t been studied by a RTC, even though there may be other types of supportive evidence. Statistical Hypothesis Testing (SHT), the primary mathematical analysis used in RCTs is also greatly limited as a technique, as it is not designed to learn from observation and does not address effectively large numbers of variables [

20]. In the reporting of RTCs, the conclusion of a “statistically significant” finding in a STH-backed RTC retains a considerable chance of being false, and approximately 30% are false, according to one estimate. This statistical method is also easily manipulated to misinterpret data and overstate the efficacy of the treatment being studied [

26]. This occurs all too often in industry sponsored “research”, given that the pharmaceutical industry has a large vested interest in product promotion, resulting in motivation to repurpose research as marketing, instead of open inquiry. While proponents argue that evidence based medicine is objective, these and other sources of institutional and individual cognitive bias are common and pervasive [

27].

Thought leaders, both in modern medicine [

26] and in Ayurveda [

3,

7] are calling for all varieties of science and medicine to move toward relying on a broader range of types of evidence. These additional types of evidence would include the four ways of knowing articulated by Charaka; authority, perception, inference, and Yukti. In addition, greater utilization of the modern techniques of decision analysis and Bayesian inference may be more helpful to advancing both Ayurveda and modern medicine than a primary reliance on RTCs [

26].

Functional medicine

Functional medicine is a form of complementary, and sometimes integrative, medicine which focuses of optimal functioning of the human body. Functional medicine respects homeostasis and biochemical individuality and aims to address underlying causes of pathology. Modern chemical lab analysis is a significant part of an assessment in functional medicine, where values that are at the outer range of normal in modern medicine are often considered to be an indication of dysfunction. Functional medicine can be practiced in conjunction with Ayurveda as an integrative approach, supported by the conceptual overlaps between the two approaches. The lab analysis used in functional medicine can be applied to supporting Ayurvedic diagnosis, understanding Ayurvedic pathology in biochemical terms, and to help assess response to Ayurvedic treatment.

Integrative medicine

The term “integrative medicine” is used in many ways in the literature. In the US, it has evolved from the older term “complementary medicine”, which refers to using any of a wide variety of “non-mainstream” practices in combination with modern medicine. The US National Institute of Health’s definition of “integrative health care” refers to using multiple approaches concurrently in a coordinated and integrated way. In this sense, integrative medicine is an increasingly popular approach in the US. In the Ayurvedic literature the term is often used in reference to integrating aspects of modern science or modern medicine with Ayurveda specifically [

2,

4,

5,

6]. The discussion which follows will address some of the different levels and ways one might consider partial integration of Ayurveda with modern science and medicine.

Issues in integrating Ayurveda with modern science and medicine

Much has been written about the pros, cons, methods and history of integrating Ayurveda with modern science and medicine [

1,

3,

4] (Patwardhan “Search” and “Ayurveda”; Patwardhan and Mutalik; Patwardhan, Mutalik and Tillu; Singh, “Exploring”; Sethi; Shankar; Sujatha, Raha “Foundational”). In considering the application of protein bioconformatics to Ayurveda, two conceptualizations of integration have been particularly helpful. The first, framed by Patwardhan, Mutalik and Tillu, delineates thirteen potential levels of integration, arranged graphically as a rainbow. It is proposed that in a truly integrated system, integration should be addressed at all levels, particularly the fundamental levels of epistemology and philosophy. This can distinguish integrative medicine from “complementary medicine”, in which different systems are applied concurrently but without coordination or integration. The levels of integration start at epistemology, philosophy, and logic, and move on to integration of interventions, evidence and strategy. A key point is that integration is deepened and strengthened by starting at the foundational levels of epistemology and philosophy and the concepts that grow out of them.

The second conceptualization, as described by Raha [

20], are the “Rishi principles”. This conceptualization revisits Charaka, and the concept of Yukti, to delineate the core values the ancient Rishi’s might have required for scientific inquiry to be consistent with Ayurvedic epistemology. The Rishi Principles are:

•Inductive learning: Universal truths are induced rigorously from subjective experiences

•Whole systems: Scientific inquiry is focused on holistic understanding

•Individually optimized therapy: Decisions are deduced using logic that integrates knowledge from the literature with local information, local alternatives, and the patient’s preferences to produce customized therapy. (Raha, “Foundational” 203-204)

Raha further evaluates common modern scientific research methods with respect to how well they embody the Rishi principles. In general, not well at all. Randomized controlled trials with statistical hypothesis testing, for example, fulfill none of them. Other techniques, such as ethnography, Ayurvedic pharmacoepidemiology, and pragmatic trials, partially or completely fulfill one or two. No modern research method he evaluated fulfilled all three [

20,

26].

Another useful idea with respect to the integration of Ayurveda and biomedical sciences was articulated by Shankar by framing the issue as a question of whether the whole and its parts can be related [

5].

It is obvious that the key point to be understood is that the relationship is not one to one because the whole is not equal to the parts nor does the sum of parts add up to remake the whole. One should therefore not be seeking equivalence in developing the relationship between Ayurveda and Western sciences, otherwise one will either reduce the whole to a part, or assume that the part represents the whole, and thus develop a distorted understanding.

Collaboration between Ayurveda and Biomedical sciences can be very fruitful. There are certain incredible details of parts that science uncovers that can enrich the understanding of the whole, and, similarly, there are new perceptions, insights that are revealed in a holistic view that can fundamentally alter the partial view.

In the final sections, protein bioconformatics will be applied to Ayurveda. How well protein bioconformatics can be integrated with Ayurveda will be evaluated using both Patwardhan's level-based principals for integration and the metric of the Rishi principles. The biomedical scientific approach of protein bioconformatics, viewing cell and molecular function at an unprecedented level of detail, will be offered as an examination of the parts in the context of the whole.

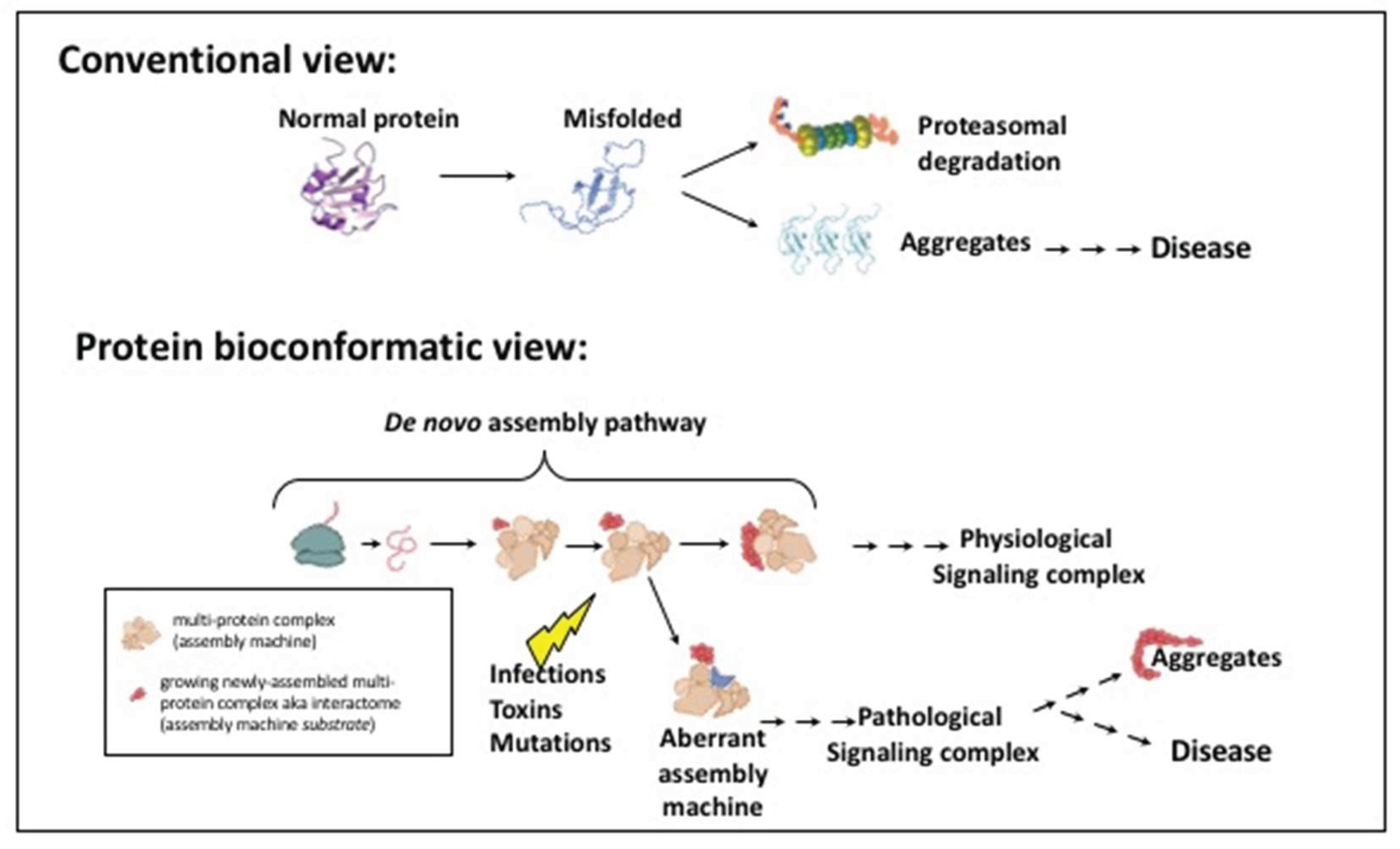

The viewpoint and history of protein bioconformatics

Protein bioconformatics is a new paradigm of cellular biochemistry. A paradigm in science is the worldview underlying the theories and methods of a subject. It does not change often. Protein bioconformatics proposes that a given protein has multiple functional folded forms, and that each of these folded forms serves distinct functions. Furthermore, the cell has mechanisms to productively and purposefully alter the distribution of these diverse folded forms. It does so in response to feedback and other biological regulatory mechanisms [

9]. This viewpoint represents a paradigm shift away from the conventional view that a protein generally has only one functional form, and that this form assembles and distributes itself in the cell spontaneously. These change in the understanding of proteins have vast implications for work in understanding normal physiology, pathology, and disease treatment.

This new view of cellular and subcellular biochemistry emerged from a line of investigation involving protein biogenesis and intra-cellular trafficking [

28,

29,

30,

31]. While the term Protein bioconformatics is one that is only sparsely reported in the literature to date, more conventional science appears to be recently unravelling aspects of protein bioconformatics. Conventionally, concepts such as “intrinsically unfolded domains” within proteins [

32], and “moonlighting functions” [

33] of proteins may each touch upon dimensions of protein bioconformatics.

Proteins

Proteins are molecules, comprised of a sequence of smaller molecules, termed amino acids, one of the four types of small molecules that are used as building blocks in living organisms. The others are carbohydrates, lipids and nucleotides. Chains of two or more amino acids are referred to as peptides. Longer chains, comprising partial and complete proteins, are termed polypeptides. Each amino acid in a peptide is connected to the next by covalent bonds, which are strong chemical bonds occurring when two adjacent atoms in a molecule share electrons. These bonds take considerable energy to make or break. That energy is usually supplied to chemical reactions in living systems by the nucleotide known as

adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The ATP molecule has a series of three phosphate groups attached to it. Breaking off the outermost phosphate of ATP releases a large amount of chemical energy which can be used to drive physiological processes such as making polypeptide chains [

16].

Protein heterogeneity and non-covalent bonds and interactions

While there are over 500 known amino acids, only twenty-three of them are used to make proteins, twenty of which are seen in human proteins. Each of these has a different side group which confers it specific properties. Some side groups are positively charged; some are negatively charged. Some are uncharged but because of uneven sharing of electrons amongst the atoms on the side chain, they are polar or hydrophilic. This means they have a somewhat different charge on each side of the molecule and “love” or mix well with water which is also polar. Some are uncharged and non-polar or hydrophobic, meaning they “fear”, or don’t mix well with, water.

The charges and polarities on the amino acid side chains cause them to be attracted to, and associate with, charged regions on other amino acid side chains, either on the same peptide chain, or on separate peptides. These associations include ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Walls interactions. Ionic bonds are formed by the electrostatic attraction of oppositely charged ions. Hydrogen bonds are ionic interactions between water and either hydrophilic molecules or charged. Van der Walls interactions are attractions between uncharged molecules on the basis of transient polarities. There are also hydrophobic interactions which are repulsive forces driven by the inability of nonpolar hydrophobic molecules to form hydrogen bonds with water.

Ionic bonds are 1/30

th and hydrogen bonds are 1/90

th as strong as covalent bonds. Van der Walls and hydrophobic interactions are even weaker. These associations also take correspondingly less energy to make and break, making them much more fluid in living systems than are covalent bonds. This renders them easily affected by changes in the cellular environment such as the amount of water or salt in the cell. Remarkably, sometimes these bonds and interactions are situated in a series of molecules that allows them to be, in summation, remarkably stable, yet easily reversible in particular circumstances or in experimental manipulation. The configurations of these bonds and associations and their effects on the shape of proteins is another way of storing information in cells [

16].

Tertiary and quaternary structure of proteins; enzymes and catalysis

The tertiary structure of the protein is formed through the attractions and repulsions of various charged amino acid side chains, and of polar and nonpolar uncharged amino acid side chains. These forces cause the different parts of the protein to associate through non-covalent bonds and interactions and the peptide chain to fold on itself in many ways, a process sometimes likened to origami.

The

protein’s quaternary structure is formed when groups of individual proteins associate through multiple non-covalent bonds and interactions, becoming a

multi-protein complex. The protein’s shape determines the role the protein will play in the cell, for example, as an enzyme, a receptor, or a part of a complex with other molecules, for example hemoglobin, which is shaped to attach to iron and to carry oxygen [

16].

Figure 1.

Four levels of protein structure. Source. Lingappa, U.F., original drawing.

Figure 1.

Four levels of protein structure. Source. Lingappa, U.F., original drawing.

Many proteins serve as enzymes in cells, which are catalysts for specific biochemical reactions. The presence of a catalyst increases the rate of a chemical chemical reaction, creating more favorable kinetics, without involving the catalyst itself in the reaction. While the second law of thermodynamics holds that in the entire universe, entropy, or randomness always increases, in specific circumstances, such as life forms, randomness is decreased. This is often accomplished by enzyme catalysts, which can help position molecules in ways that make reactions between them require less energy to activate, and occur more often than they would at random. Enzyme catalysts can also link reactions requiring energy to other reactions that release energy, favoring the occurrence of these reactions. The most common of these is the involvement of enzymes to break a phosphate group from an ATP molecule, and applying the energy released to form a new covalent bond, for example in the creation of a protein polypeptide chain from amino acids [

16].

Protein bioconformatics studies the conformers, or alternatively folded shapes of proteins, including in the formation of multi-protein complexes. Conformers of a protein have the identical covalent string of amino acid residues, but folded differently, that is they differ in the non-covalent bonds formed, which manifest as the tertiary and quaternary structures of proteins. These turn out to be of enormous importance to understanding cell physiology and can also be applied to describing a molecular basis for features of Ayurveda.

The paradigm of protein bioconformatics

There are five concepts that currently define the protein bioconformatics paradigm, that is, the foundations on which this line of research is built. Before exploring these concepts further, they are, in brief:

•The assembly of proteins into multi-protein complexes is a critical component of how cells work and pervades all aspects of cellular function.

•It is hypothesized that these multi-protein complexes do not to assemble spontaneously. Rather, their assembly is catalyzed by other multi-protein complexes called assembly machines.

•The composition, stability, and action of assembly machines is hypothesized to be regulated in a transient and energy-dependent manner, by so-called allosteric binding sites within component proteins.

•Disorders of assembly machines are a diagnosable and treatable root cause of a wide range of diseases.

•The structures of proteins and protein complexes are far more diverse than predicted by the sequences encoded in the genome, this may be partially explained by multiple alternate folded conformers for many proteins.

The first concept is that the cell is a very crowded place [

34] and that the only way for events to occur in a coordinated fashion is for proteins in general, and enzymes in particular, to be highly organized, and directed in their actions. To do this, many, if not most, proteins are organized into multi-protein complexes, which remain a critical and poorly understood dimension of cell biology. In analogy, genes may be the blueprints for life, but the proteins encoded in those genes brings one to life. The interactions involved in protein assembly are difficult to detect because many are transient and because in order to occur, they may require an energized, cellular environment, or something resembling it. Conventional techniques of studying proteins in relative isolation from the cellular environment in which they are naturally produced may be unable to detect the interactions in protein assembly that drive the creation of tertiary and quaternary structures [

35].

The second concept in the paradigm is that multi-protein complexes do not assemble spontaneously [

10]. Assembly of proteins into multi-protein complexes has, in the past, been generally assumed to occur spontaneously. Spontaneous assembly of complex protein-based structures including cell membranes, viral capsids and many other structures has been scientific dogma for a century [

36]. An alternative explanation of how component proteins find each other in the crowded environment of the cell is that protein assembly is catalyzed by enzymes termed assembly machines. However, perhaps because assembly machines are normally highly transient and energy dependent [

37], and therefore invisible to conventional methods, they have largely been overlooked to date [

38]. As a result, various assembly machine-catalyzed biological processes are assumed to occur spontaneously. Assembly machines are themselves a type of multi-protein complex and their actions can be thought of as that of a cascade of enzymes carrying out catalysis of protein assembly.

The third concept in the paradigm is that allosteric sites regulate the composition of assembly machines, and that the actions of assembly machines are integrated with cellular homeostasis [

39,

40]. An allosteric site is a specific region on protein or a protein complex, which, when occupied by a small molecule, causes a change elsewhere in the protein or protein complex. These allosteric sites can be likened to control panels that regulate one feature or another involving a change in conformation of either an individual protein or in the composition of a multi-protein complex (such as an assembly machine). These regulatory features make allosteric sites likely contributors to a molecular basis for homeostasis. In the case of assembly machines, when a small molecule binds to an allosteric site, the protein composition and action of the assembly machine may change. This and other features of the catalyzed assembly process makes it very difficult to track using conventional lab techniques.

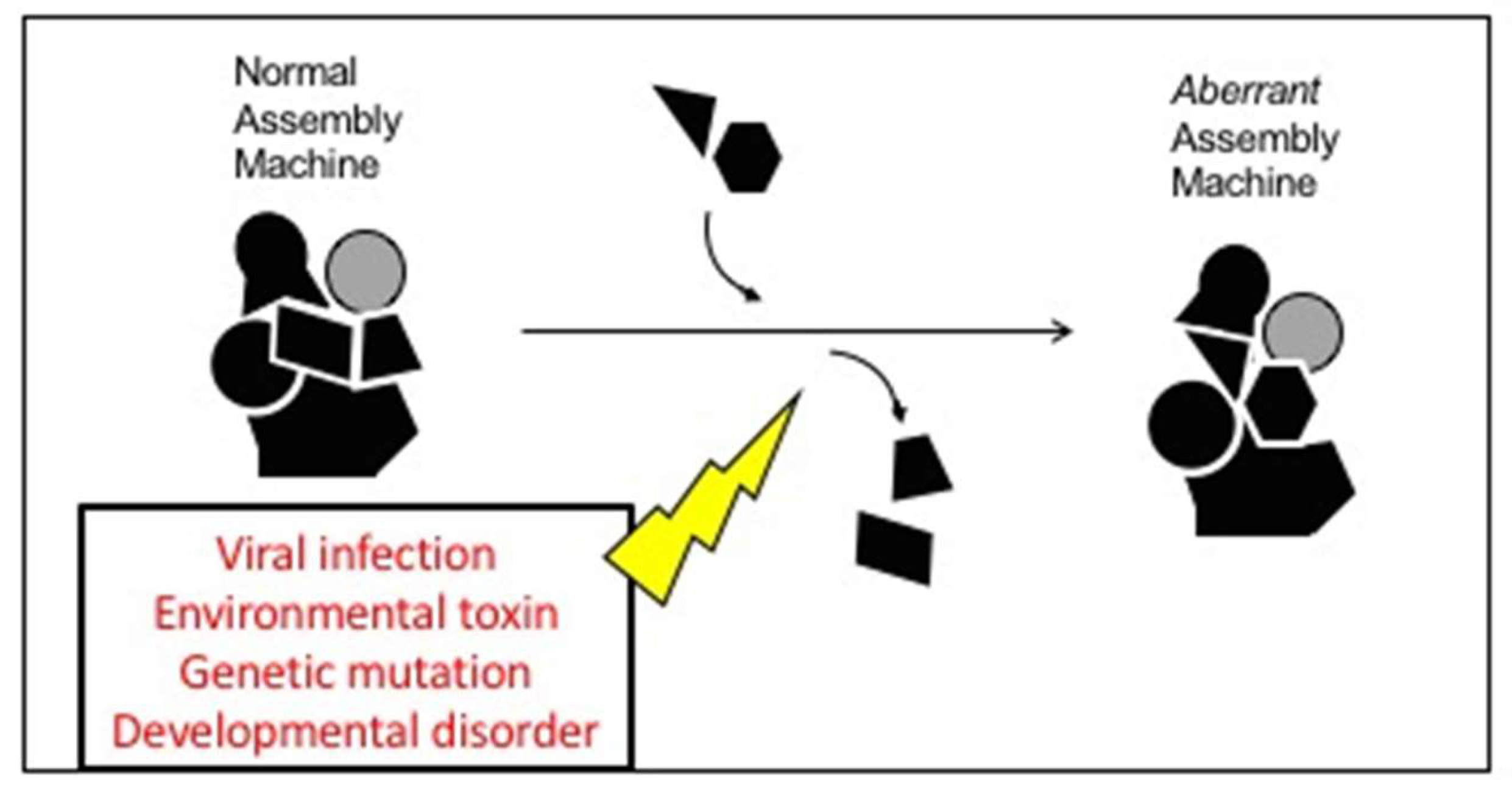

The fourth concept of the paradigm is that aberrant, or abnormal, assembly machines are a root cause of many types of pathology. For example, the use of a host’s cellular machinery by viruses or cancer cells to replicate without restraint, have been shown to be consequences of aberrant assembly machines [

37,

38]. Detecting and correcting the malfunction and misuse of assembly machines may lead to effective and lasting treatment of disease, often early in the process of pathogenesis [

41], sometime viewed in the west as prevention.

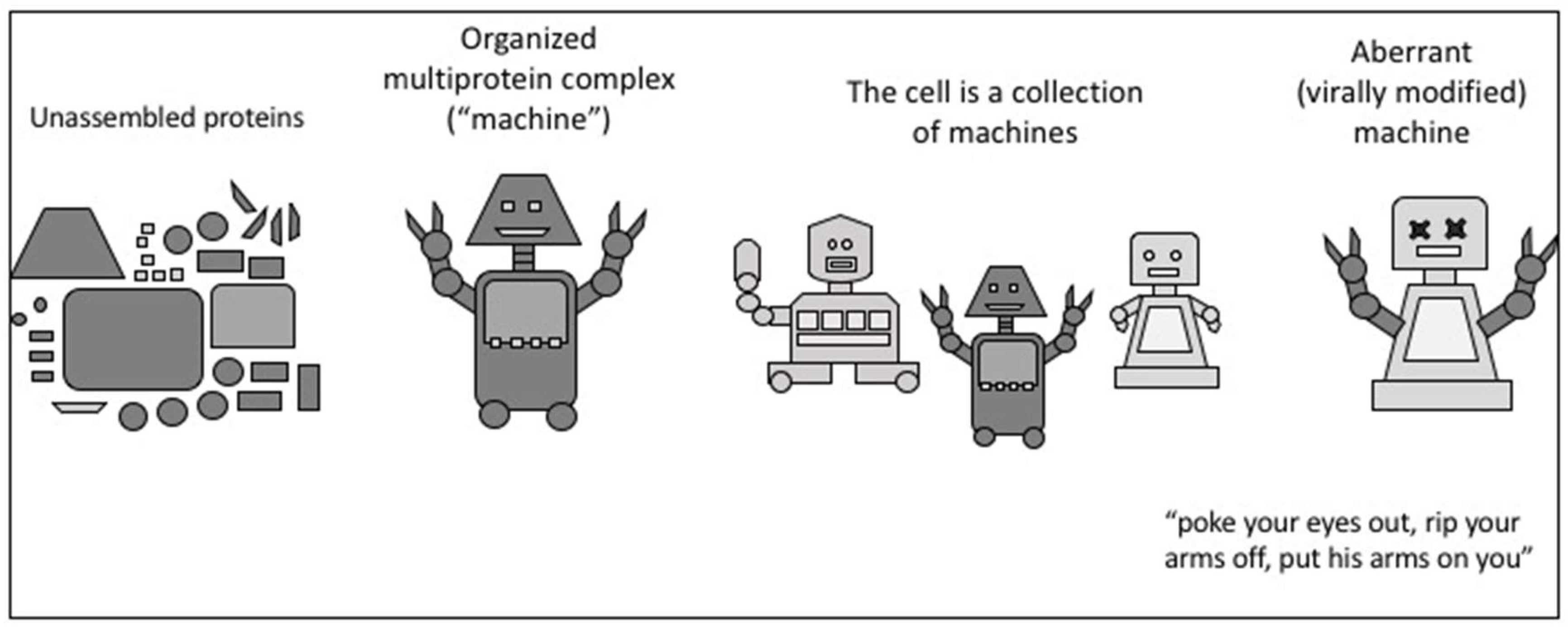

Figure 2.

Normal and aberrant assembly machines. Source: Lingappa, U. F. original drawing.

Figure 2.

Normal and aberrant assembly machines. Source: Lingappa, U. F. original drawing.

The fifth and final concept of the paradigm is that proteins and protein complexes are highly diverse, far more so than would be predicted by the number of amino acid primary structure sequences encoded in the DNA of the genome. Each polypeptide sequence apparently has multiple possible alternate folded conformers, some stable, some unstable. Each conformer may have a different function in the cell, including for some, becoming a part of the multi-protein complexes that serve as assembly machines. Techniques of structural biology, such as X-ray crystallography, are useful to visualize for study the static structure of one stable conformer of a protein. However, these techniques are likely to miss many other conformers, especially those that are unstable or transient, thereby failing to appreciate their contributions to cell physiology and confounding attempts to study and understand assembly machines [

29].

Tools for studying protein bioconformatics

The next step in explaining the science of protein bioconformatics is to discuss some of the unusual tools and methods that scientist studying it employ. There are both specialized scientific assays and computational methods, and unconventional applications of more common techniques. These include the

cell free protein synthesis and assembly system (CFPSA) [

10],

drug resin affinity chromatography or DRAC [

37,

38], the use of viruses to help identify allosteric sites and assembly machines [

42], and applying to protein bioconformatics the technique from systems biology called

interactome analysis [

41,

43,

44].

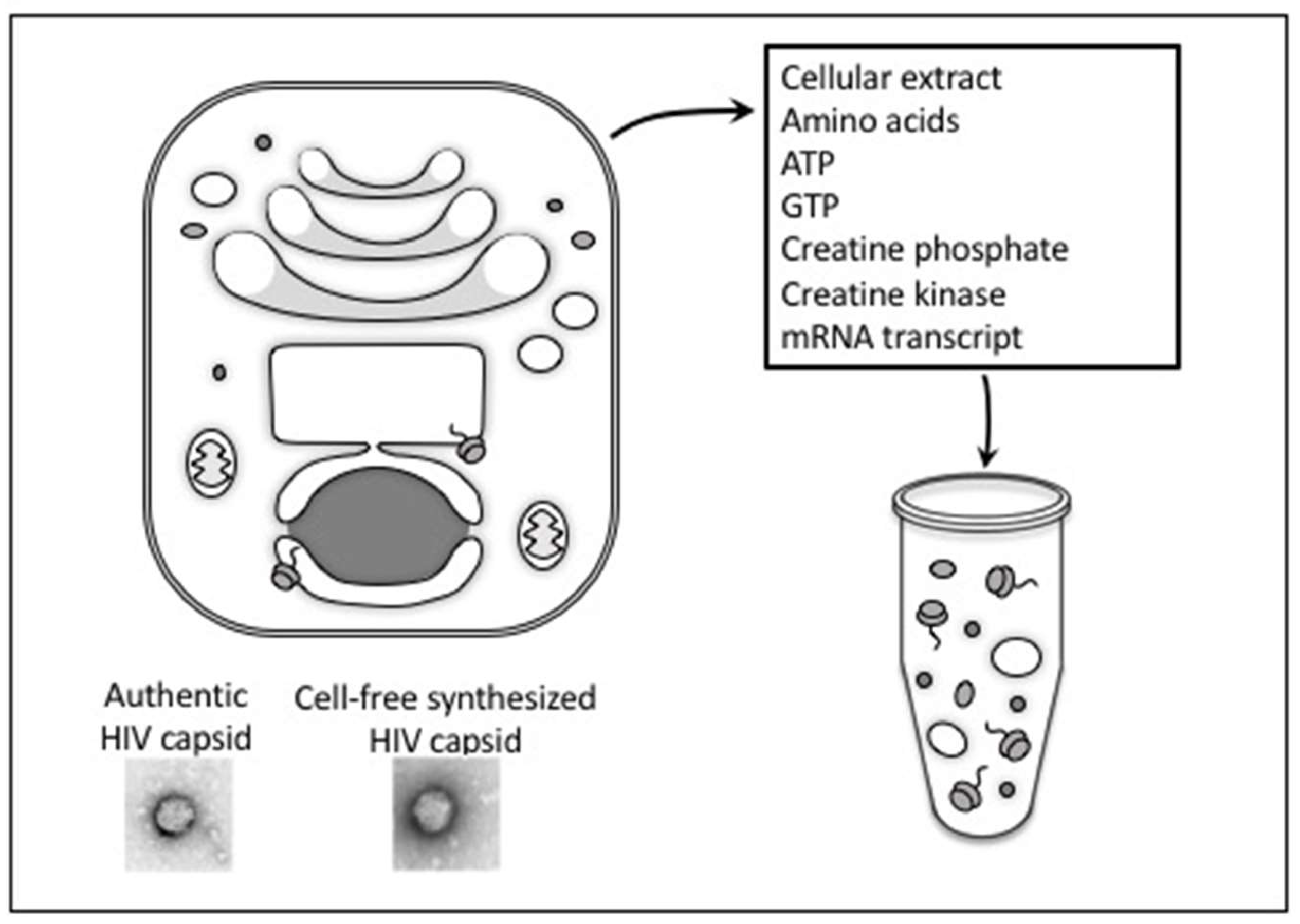

The cell free protein synthesis and assembly system (CFPSA). The cell free protein synthesis and assembly system (CFPSA) is the foundational method for studying protein bioconformatics. Variants of this tool have been in use since the 1950s, and were instrumental in both deciphering the genetic code and gaining understanding of the mechanics of moving proteins from place to place within a cell [

45,

46]. In the popular media the CFPSA system has been referred to as “cellular stew” [

47]. Basically, it is a liquid mixture of ground up cellular components, without intact cells. It has all the molecules needed for eukaryote cells to function; lipids, proteins, carbohydrates and nucleotides, including ATP, to provide metabolic energy. Wheat germ extracts are commonly used for the CFPSA, because, as it turns out and has been recognized in Ayurveda for centuries, plants and animals are not so different in their internal cellular machinery. An extract of the cellular components of a plant is highly suitable for study the study of the cellular biochemistry of an animal.

In the CFPSA one can study, by manipulating variables, the formation and folding of proteins in a relatively natural environment but without the barrier of a cell wall or the homeostatic influences complicating observations in an actual living cell. Thus the CFPSA is something like a zombie, it closely resembles a living cell, but it is not actually alive. As a consequence it is not as fragile as a living cell. It becomes possible in this system to slow down the flux of, and therefore more readily see, transient and unstable multi-protein complexes serving as assembly machines, as they catalyze the formation of other multi-protein complexes.

Figure 3.

The cell free protein synthesis and assembly system (CFPSA). Source. Lingappa, U.F., original drawing.

Figure 3.

The cell free protein synthesis and assembly system (CFPSA). Source. Lingappa, U.F., original drawing.

The importance of simulating the cellular environment when making a protein, a process referred to as protein biogenesis, is conveyed in the following analogy. Consider a human infant “A”, and the nurturing and stimulation that occurs in a loving family as she develops into a normal adult. Consider what kind of adult another infant “B”, would become if, from birth, she is locked in a room alone and given nothing but food and water. A protein, such as a recombinant protein cloned in bacteria, created in isolation from its natural eukaryotic cellular environment, which contains the molecules that shape and inform it, will in ways be like infant “B”, devoid of many of the characteristics and capabilities of a protein created in its natural environment.

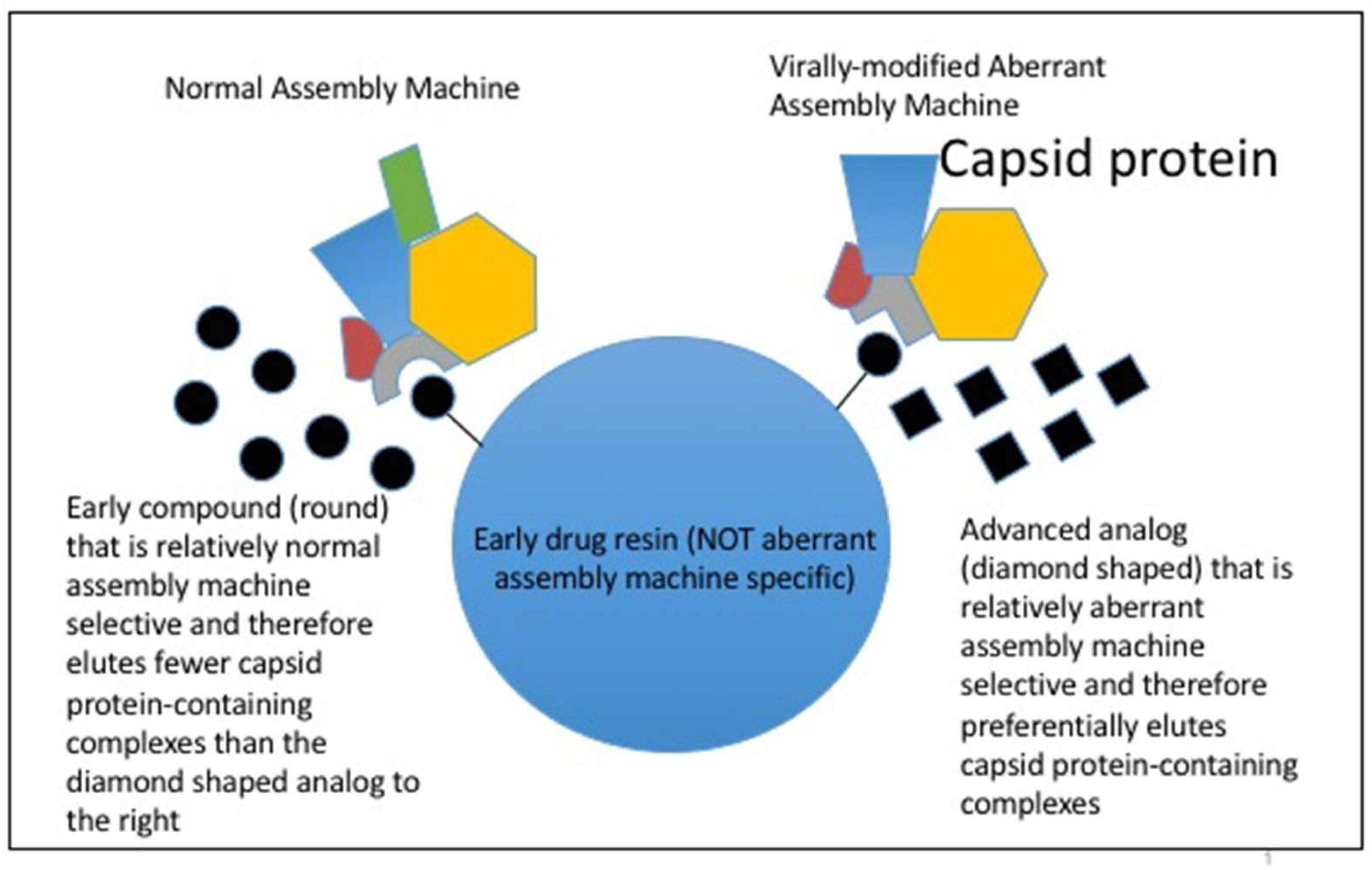

Drug resin affinity chromatography (DRAC). A second important technique in the study of protein bioconformatics is

drug resin affinity chromatography or DRAC [

37,

38,

48]. In this technique it is possible to identify and characterize the proteins and multi-protein complexes that are produced in the cell free system. Basically, drug molecules are attached to plastic resins and submerged into the cellular stew. Proteins and complexes that are attracted to that drug molecule will attach to it, sometimes at an allosteric site. The DRAC system can be likened to a fishing pole. The drug molecule is the bait, the resin is the hook and pole, the proteins you are looking for are the fish, and the allosteric binding site is the fish’s mouth. How many and what kind of fish you catch is related to how appealing the bait is to particular types of fish, what types of fish are swimming near the fishing pole, and how hard they bite.

After catching the molecules of interest on the resin, unattached molecules in the stew can then be washed away, and the remaining attached molecules can be analyzed for size, shape, and function. They can be taken apart, put back together, and even put back into the CFPSA to validate their activity [

48]. If multi-protein complexes, they might contain only normal cell components, or they might be pathological, including proteins not normally found in healthy cells, such as proteins that make up virus capsid, or gene products implicated in cancer [

38,

44,

49]. It becomes possible through this technique to study the relationship between structure and function, or

structure activity relationship, SAR [

44]. This information can be used to create specific and powerful drugs that bind to the allosteric site on a protein and change its function. Applied to the fishing analogy, this would help you learn how to create bait that is more delicious to specific varieties of fish.

Figure 4.

Drug resin affinity chromatography (DRAC) applied to protein bioconformatics. Source: Lingappa, V.R. Original.

Figure 4.

Drug resin affinity chromatography (DRAC) applied to protein bioconformatics. Source: Lingappa, V.R. Original.

Viruses as truffle hounds [42]

Scientists working on protein bioconformatics describe the next technique as analogous to enlisting viruses as truffle hounds. Truffle hounds are specially trained dogs who know how to locate the unseen underground fungal delicacies. Viruses, it turns out, are very good at finding allosteric binding sites on human proteins. Since the human lifecycle is approximately 50,000 times longer than that of a virus, viruses can and do evolve as much as 50,000 times faster, and have learned the best points at which to disrupt their host’s system for their own benefit [

42]. Many of these points, not surprisingly, involve allosteric sites on the multi-protein complexes that serve as assembly machines.

Interactome analysis

The final research method to mention in protein bioconformatics is known as

interactome analysis, a technique from

systems biology. An interactome is a set of molecular interactions in a cell or a system or a disease. Generally, this refers to protein-protein interactions. For example, the HIV interactome is all the protein-protein interactions in a cell that are involved in HIV replication. Interactomes are conventionally identified by bioinformatic computational techniques applied to the activities of a cell system. CFPSA and DRAC systems can identify the proteins and multi-protein complex assembly machines involved in a particular disease process. Strikingly, these turn out to be, for the same disease, many or most of the same proteins that are part the interactome identified through systems-based computational techniques. Interactome analysis alone does not elucidate which of these proteins are working together as assembly machines. Protein bioconformatics, specifically through the tool of DRAC, does [

37,

38,

41].

Vata Dosha

Vata is a Dosha. Dosha is an axiomatic concept in Ayurveda that has no directly corresponding concept in modern science and medicine, although it aligns somewhat with the concept of humors in ancient Greek and Roman medicine. The concept is first seen in Ayurveda in the works of Charaka. As described in modern Ayurvedic texts [

14]:

The concept of Dosha contains two fundamental ideas: (1) its being a bioenergetics substance and (2) its acting as a bioenergetics regulatory physiological force, process or principle. . . The biological Doshas are psychophysiological principles of organization, both structural and functional. . . They are the basic organizing principles that regulate and maintain physical and psychological homeostasis. . . . These homeostatic regulators act as protective barriers guarding the health and integrity of the body.

There are three Doshas in Ayurveda; Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. Each embodied individual has had determined, at the moment of conception, the unique balance between the three Doshas, that will define that individual’s intrinsic physiologic constitution. Deviation from that balance of Doshas, in either excess or deficiency, may lead to pathology.

Vata Dosha is the Dosha that is sometimes considered related to the air humor, though this is not a direct correspondence. Vata means wind in Sanskrit, and Vata is the Dosha of movement or propulsion. To quote Ninivaggi again [

14]:

Vata is responsible for all movement in the body from the cellular to the tissue and musculoskeletal level, for coordination of the senses, for the equilibrium of the tissues, for the acuity of the senses and for respiration . . . Vata has the following qualities: cold, dry, light, subtle, mobile, sharp, hard, rough, and clear. Vata is composed of the Ether (Akasha) Element and the Air (Vayu) Element.

Turning to protein bioconformatics, the multi-protein complexes, identified through this lab science, that appear to serve as assembly machines in the production of other multi-protein complexes, have a high correspondence to the characteristics and functions of a Dosha. Applying the definition of Dosha as articulated above by Ninivaggi, assembly machine action, like Doshas, serve regulatory functions in cell physiology. They are principles of structural and physiological organization maintaining homeostasis. Put narrowly, perhaps assembly machines are a major molecular mechanism through which Doshas manifest. Put more broadly, perhaps assembly machines are Doshas.

While aspects of assembly machine function can be applied to explain manifestations of all three Doshas, Vata Dosha is of particular interest because it is the Dosha governing movement, coordination, equilibrium and acuity. Assembly machines are, like Vata Dosha, always in motion. Their existence is the result of a constant and elaborate dance involving groups of proteins joining together, in a directed way, for perhaps milliseconds, to facilitate the creation of other multi-protein complexes, which themselves may have structural, catalytic, and homeostatic roles in the cell and organism. The proteins in the assembly machine multi-protein complex may disperse as fast as they came together. Assembly machines are a highly mobile phenomenon. Like Vata Dosha, assembly machines might be characterized as light, subtle, and mobile. It is more difficult to speculate on whether or not, like Vata Dosha, assembly machines are cold, dry, sharp, hard, rough or clear, since modern science does not generally describe molecules in those ways. Assembly machines may be required for all the functions of Vata Dosha, and may be hypothesized to be a significant component of the molecular mechanisms through which Vata Dosha manifests.

The involvement of assembly machines in Vata Dosha can also be described in situations of imbalance, when Vata Dosha is in excess (vitiation) or deficiency, relative to an individual’s natural constitution. Major clinical symptoms of Vata vitiation are pain, tissue loss, and hypersensitivity. Other manifestations include trembling, agitation, and anxiety. The science of protein bioconformatics has not yet reached the point where it can correlate assembly machine function with these symptoms.

However, a body of evidence suggests that aberrant assembly machines, that is assembly machines whose protein composition is altered and deviating from normal homeostasis/homodynamic function, may be the molecular basis for initiation of disease pathogenesis [

37,

38,

48]

. It is striking that several Vata-associated neurodegenerative processes which manifest many of these symptoms, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, appear to be fundamentally diseases of assembly machine dysfunction [

41,

43,

51,

52].

Figure 5.

Neurodegeneration: The conventional and the protein bioconformatic views. Source. Lingappa, U. F., original drawing.

Figure 5.

Neurodegeneration: The conventional and the protein bioconformatic views. Source. Lingappa, U. F., original drawing.

In reviewing Ayurgenomics, Sethi reports that individuals whose constitutions are intrinsically Vata predominant have “enrichment of differentially expressed genes involved in cellular processes such as cell cycle, DNA repair, and recombinant as well as transport functions. Vata governing manifestations of shape and cell division and transport has also been described in Ayurveda texts” [

25]. These descriptions apparently have come from genomic and transcriptomic analysis. However, given the functions of protein conformers, and of assembly machines described above, it is intriguing to speculate that characteristics of the protein bioconformatic functions in Vata predominant individuals may prove to be even stronger correlates in cell biology to the Vata constitutional type than the characteristics of DNA and RNA that have thus far been studied.

Samprapti

Ayurveda and modern medicine have somewhat different ways of viewing the onset of disease processes. In general, modern medicine considers a disordered state pathological only after the manifestation of disease-specific symptoms. More recently this view of pathology has expanded to abnormal laboratory test and imaging abnormalities which are substantially out of the physiologic range, creating diagnoses like “dyslipidemia” and “pre-diabetes”. There are also a range of laboratory abnormalities that are considered non-pathologic in modern medicine, but which are arguably not physiologic either. These abnormalities are increasingly recognized as early pathology in other medical systems, including Functional Medicine and Ayurveda. Ayurveda has a conceptualization of disease development that considers disturbances which occur far earlier than specific symptoms. The concept of aberrant assembly machines, has the potential to provide a molecular basis for pre-disease states which is consistent with the Ayurvedic concepts of early aspects of disease development.

Samprapti is the central Ayurvedic conceptualization of pathogenesis. It is holistic, looking at connected imbalances in a system, and it is dynamic, looking at the evolution of manifestations of disease over time. Ayurveda considers Samprapti to have six stages, the first three describe preclinical manifestations of pathology, and the second three describe more specific clinical disease. The stages are the following:

First, Sanchaya describes the excess accumulation of a Dosha, in it’s home site in the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms are vague, mild and non-specific, such as mild anxiety or mild constipation.

Second, Prakopa is the stage where in which the excess Dosha becomes aggravated or more intense. Symptoms remain vague but become more intense, for example non-specific pain or abdominal bloating.

Third, Prasara occurs when the aggravated Dosha spreads from its home site in the gastrointestinal tract and, moves to peripheral sites through channels. Symptoms may intensify in a particular location, such as moderately severe back pain or abdominal bloating with pain and constipation.

Fourth, Sthana-Samshraya is the stage where the aggravated Dosha localizes in another, weakened, tissue, and causes more overt pathology of the sort that may be diagnosed as a disease in modern medicine. Tissues become filled with toxins and waste products that are not removed through blocked and damaged channels. With this the metabolic fire of the tissue decreases. More generalized and severe symptoms like malaise and depression often appear here.

Fifth, Vyakti is the manifestation of the disease with specific symptoms of that disease. Sixth and last, Bheda describes the final stage of disease differentiation, specific to a tissue, and possibly spreading, as a disease, to other tissues, such as the spread of an infection or a cancer [

14].

Protein bioconformatics has identified assembly machine dysfunctions occurring very early in pathological processes. For example, in a viral infection, there is a pre-symptomatic phase, in which the virus is in the process of taking over some of the host organism’s assembly machines to its own purposes, while not having yet made new viruses. Only after viruses are produced and spread throughout the body do disease symptoms occur. Thus, even though clinical symptoms have not yet developed, it should be possible to detect the aberrant assembly machines that will predict the coming disease, in the preclinical stages of, Sanchaya, Prasara and Pracopa. Recently, precisely a version of such early detection has been achieved, with a drug that targets assembly machines and is therapeutic for the disease it detects [

41]

It is hypothesized that the development of aberrant assembly machines starts when some of the assembly machines become disordered, while others remain normal. In this situation it may be difficult for the cell to distinguish normal from aberrant assembly machines, thus erroneously facilitating the propagation of aberrant assembly machines, not realizing they are abnormal. When this happens, at some point overt disease will manifest and spread. A line of evidence supportive of this postulation is emerging from neuroscientific data on neurodegenerative diseases. Latent neuropathology is observed in locations remote from the central nervous system for years before central manifestation of disease, with subsequent progressive spread to and through the CNS [

53,

54,

55].

This is particularly striking in the case of Parkinson’s disease where severe constipation and lack of ability to smell usually proceeds manifest central symptoms of Parkinson’s disease by several years, correlated with abnormalities in the neural tissue innervating the colon and nose. The bioconformatic paradigm hypothesizes that the cell-to-cell signaling that promotes the spread of aberrant assembly machine formation is a precursor to disease. Ayurveda views Parkinson’s disease as a predominantly a Vata disease, and the colon is considered the home site of Vata Dosha. Using inductive reasoning, one could postulate that in Parkinson’s disease, Vata associated assembly machine dysfunctions begin in the colon and later spread to other weakened central and peripheral neural tissue, perhaps by use of a signaling mechanism allowing cell-to-cell spread. This is exactly the sequence of events Ayurveda describes as Samprapti. Identification and observation of the function and dysfunction of assembly machines could provide support for the Ayurvedic conceptualization of Samprapti.

Individual Variation and Personalized Medical Care

Diagnosis and treatment in Ayurveda is highly individualized. In the past century, the approach of western medicine has become relatively standardized and less attuned to individual variation. With advances in the omic sciences, this is now changing. Through the omic sciences individualized diagnosis and treatment is being advanced, often at a genetic level, in this respect increasing alignment with Ayurveda.

While much can be learned about individual differences by studying nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), it is increasingly apparent that differences in DNA and RNA are insufficient to explain the range of individual variation manifest in humans. Other mechanisms, including epigenetic and non-genetic mechanisms, must be at work. Many of the individual differences not accounted for in genomics may be manifestations of differences in protein function, and here protein bioconformatics may be able to contribute additional explanation. Some of biochemical individuality is accounted for by differences in protein conformer distribution. A small molecule, either a drug or an herb component, may be effective only in individuals in which a particular conformer of a protein is dominant. Another individual, in whom the same protein has folded into a different predominant conformer may not respond. Likewise, the allosteric sites that appear to govern assembly machine composition may be modulated differently depending on the conformer distribution of a particular protein component.

Individual differences in Prakruti phenotype, such as whether Vata, Pitta, Kapha or a combination is one’s innate predominant constitution also appear to have a component of genetic basis. There are many published articles correlating Prakruti type with genetic markers such as HLA alleles and RNA transcripts, and with metabolites such as inflammatory markers, hematologic profiles and lipid profiles. These studies have established that there is a considerable overlap with the presence or quantity of some of these molecules and specific Prakruti phenotypes, or with disease states associated with specific phenotypes [

25,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. It has been proposed to move forward to explore several axes of pathophysiology for which ways of measurement and overlap are partially established [

25]. These include cardiovascular function, systemic inflammation, apoptosis, the microbiota and anthropometry [

25]. Adding the tools of protein bioconformatics to the exploration of individual differences in Prakruti phenotype has great potential to strengthen this analysis.

Rabies / Alarkavisha

Rabies is one of the most terrifying diseases known to humans. It’s symptoms, usually leading to death, are horrifying. In modern medicine it is conceptualized as an infectious disease caused by several lyssaviruses, members of the Rhabdoviridae family. It is usually transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected animal. The incubation period can be as short as one week or as long as one year, most commonly one to three months. It causes acute inflammation of the brain and progressively more severe neurological symptoms, including the hallmark symptom of fear of water or hydrophobia. After symptoms develop it is considered incurable by modern medicine, with exceedingly rare possible exceptions.

In classical Ayurvedic texts, rabies is referred to as Alarkavisha, which translates literally to “poison from a mad dog”. Charaka described Alarkavisha as a Tridoshic vitiation, and an opposition between Dhatus. Sushruta and Vagabhata wrote that when Vata gets aggravated in the dog, the Vata can combine with aggravated Kapha and accumulate in the sense organ Srotas, causing sensory deprivation, salivation and mad, biting behavior [

12]. When a human is bitten by such a dog, the array of symptoms described in Ayurveda parallels those of modern medicine. Unlike in modern medicine, Sushruta mentions three specific symptoms that portend incurability; the affected person imitating the biting animal, the affected person seeing the image of the biting animal in a mirror or in water, and the affected person developing hydrophobia or Jalasantrasa [

61].

In modern medicine, rabies is treated after exposure by giving a series of four or more doses of rabies vaccines and a dose of human rabies immune globin, which is injected mostly into the wound. This is usually effective if given in the first six days after a bite and before any symptoms develop. However, this treatment is expensive and requires refrigeration, making it unavailable to most people who might need it. There is also a treatment protocol which uses multiple drugs to induce a coma which can mitigate the brain inflammation that occurs with acute infection. Amongst individuals developing early symptoms of rabies, there are a very few controversial reported survivors who have been given this treatment [

62,

63].

Like modern medicine, Ayurveda emphasizes post-exposure preventative treatments for rabies. The concept, in Sushruta, is that as there is no chance of recovery after the poison is spontaneously aggravated, the poison should be artificially aggravated and remedied before that happens. The preventative treatments include pouring hot ghee on the site of the wound, and then applying Agada, anti-poison medicine, of which there are many herbal options. Drinking ghee followed by purgative medicines is also recommended as are baths from pots of cold water in which precious gems and medicinal plants have been placed. Many plants are suggested in the classic texts and, used in combination, the anti-poisonous effects are enhanced.

Returning to protein bioconformatics and applying it to rabies, the cell free protein synthesis and assembly system, the vernacular “cellular stew”, can be turned into a “rabies soup” [

47]. This is done by making rabies proteins in the extracts, without live virus in the mix. Using DRAC techniques, nascent rabies proteins can be used as “bait” to attract the multi-protein complexes that are hijacked by the virus to assemble more rabies viruses. Small molecules can then be identified that block formation of assembly machines that have been repurposed to produce viruses. These small molecules do this by intervening at the regulatory allosteric sites that govern multi-protein complex assembly machine formation and action. These small molecules have been tested in cell culture where they were seen to stop rabies from replicating, doing so without conferring toxicity to the host cells [

48].

Figure 6.

Cartoon depiction of viral modification of assembly machines. Source: Lingappa, U.F., original drawing. .

Figure 6.

Cartoon depiction of viral modification of assembly machines. Source: Lingappa, U.F., original drawing. .

These findings may correlate with several features of the Ayurvedic approach to rabies. First, the allosteric sites on the protein assembly machines that produce viral capsids may be the biological pathway impacted by the multiple and synergistic active components of anti-poison herbs and minerals that are reputed to cure rabies in Ayurveda. Second, the findings suggest that directed treatment can be successful, even after symptoms develop, if the symptoms are not too severe. This supports the statements in the Ayurvedic classical texts that mention several severe symptoms that predict incurability, but do not suggest that mild symptoms are incurable. The turning point, defined by Susruta as the point of spontaneous aggravation of the poison, may be a point of no return in the viral take-over of cellular systems and/or of migration into the brain itself. The artificial aggravation of Vata Dosha, and removal of the poison, may be accomplished by a variety of approaches, the common pathway possibly being allosteric manipulation of host involvement in viral reproduction, through assembly machines.

Cancer / Arbuda

Cancer is another, often fatal, disease that humans particularly dread. Modern medicine and Ayurveda each have different conceptualizations, naming systems, models of pathogenesis and treatments for cancer. Contemporary research in omic sciences and personalized medicine is beginning to develop conceptual bridges between the views of modern medicine and of Ayurveda regarding cancer. One bridge is emerging from data on the interface between cancer, metabolic syndrome and chronic inflammation. The search for molecular biomarkers that represent Ama, an Ayurvedic concept of a pathologic waste material that is toxic and inflammatory can also inform and connect the approach both traditions have towards cancer. Protein bioconformatic science is developing new lines of evidence that may be consistent with the Ayurvedic view of cancer. These include elucidating the role of assembly machines in cancer proliferation, and in developing treatments that have pan-cancer efficacy [

38,

44].

The term cancer means crab in Latin and is said to be applied to this malignant disease because swollen veins around a cancerous tumor can look like a crab. The behavior of the disease can be crab-like also, tenaciously grabbing tissue from which it cannot be removed. In modern medicine, cancer is conceptualized as a disease caused by uncontrolled division of abnormal cells. Over 100 types of cancer have been separately identified through the modern diagnostic technique of microscopic analysis of cellular abnormalities. A modern review of cancer pathophysiology [

64] delineates eight hallmarks of cancer cells that distinguish cancer cells from normal cells; sustained proliferative signaling, unresponsiveness to inhibitory growth signals, resistance to programmed cell death, replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis, tissue invasion and metastasis, reprogrammed energy metabolism, and the ability to evade immune surveillance. Subsequent work has expanded the hallmarks [

65]. Bioconformatic studies may have identified a truly cancer-selective hallmark [

38].