Introduction

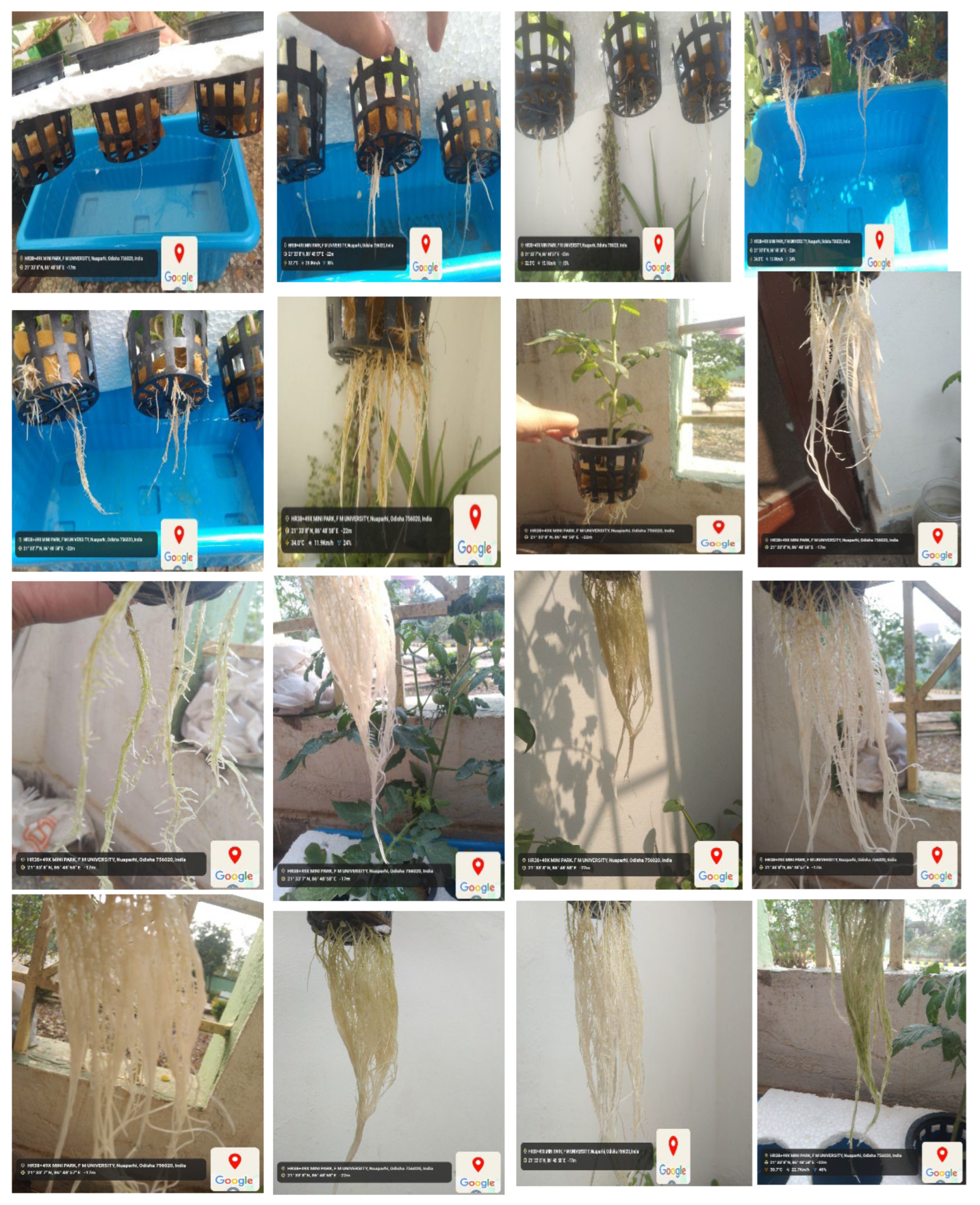

The rising demand for fresh, nutritious food coupled with increasing concerns over environmental degradation and resource scarcity has brought sustainable agriculture to the forefront of global priorities. Traditional farming methods, while essential, often rely heavily on land, water, and chemical inputs, posing significant challenges in regions facing urbanization, climate change, and declining soil fertility. Hydroponic is the technique to plant development using nutrient solutions which may or may not include the use of an inert medium to provide mechanical support, such as rock wool, gravel, vermiculite, peat moss, sawdust, coir dust, coconut fibre, etc. (Sharma et al., 2018) Maharana and Koul (2011). The name hydroponics literally means "water work" and is derived from the Greek term’s hydro, which means water and ponos, which means labour. Early in the 1930s, Professor William Gericke came up with the term "hydroponics" to refer to the practice of growing plants with their roots suspended in water that contains mineral nutrients. In 1940, Purdue University researchers established the Nutri culture system. Commercial hydroponic farms were established in several countries during the 1960s and 1970s, including the Russian Federation, Arizona, Abu Dhabi, Belgium, California, and Japan. According to needs of various plants, the majority of hydroponic systems automatically regulate the amount of water, nutrients and photoperiod (Resh,2013). Rapid industrialisation and urbanisation are reducing the amount of arable land as well as traditional farming methods, which have a variety of detrimental effects on the environment .Techniques for producing enough food must change in order to feed the world's expanding population in a sustainable manner (Sharma et al. 2018).While arable land decreases and conventional agriculture harms the environment, floriculture struggles globally with soil-borne diseases, limited land, weather constraints, and labour demands (Devi et al., 2011; Dinesh et al., 2014). An alternate strategy for sustainable production and the preservation of rapidly dwindling land and water resources is to modify the growing medium. In the current environment, soilless cultivation may be effectively started and taken into consideration as a substitute for growing crops, vegetables, or other healthful food plants (Butler and Oebker, 2006). Soilless agriculture encompasses hydroponics, aquaculture, and aerobic agriculture. According to Macwan et al. (2020), soilless hydroponic systems are suitable for cultivating a diverse group of plants, such as fruiting, flowering, medicinal, and ornamental varieties. It can be used to cultivate a wide range of special and commercial crops, such as leafy vegetables, tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, strawberries, and many more. The United States of America and the Asia-Pacific region are the next two largest producers of hydroponics, with France, the Netherlands, and Spain leading the way in Europe (Prakash et al., 2020). Kamenetsky and Okivi (2012) noted the successful use of hydroponics for cut flower production in the Netherlands. Murumkar et al. (2012) define hydroponics as the art and science of soilless crop cultivation, a technique that mitigates soil-related challenges common in traditional agriculture. The benefits of hydroponics when there is no adequate soil for agricultural cultivation or when the soil is contaminated with certain illnesses, crops can still be cultivated. There is a significant reduction in labour for many intercultural tasks including watering, fumigating, cultivating, tilling, and other procedures. The technique is economically viable in high-density and costly land locations since the maximum yield can be achieved. Water and fertilizers can be used effectively with this strategy because there is less possibility of the beneficial chemicals being lost; it can therefore result in less pollution of the land and streams. By implementing this approach, soil-borne plant diseases can be effectively eliminated. Using the system (i.e., timely nutrient feeding, watering, and root environment) and various types of greenhouses allows for more thorough environmental control. By utilizing a water and nutrient solution, hydroponic systems facilitate soilless plant growth, providing superior control over factors such as plant nutrition, lighting, humidity, and temperature, which translates to efficient space utilization, reduced chemical inputs, water and fertilizer conservation, and accelerated, weather-independent yields, especially where traditional farming is challenging (Khater et al.,2021);(Masa et al.,2020);(Maucieri et al.,2019);(Sambo et al.,2019).Plants are cultivated on soil in traditional agriculture. However, plants do not require soil to flourish; rather, they require the nutrients found in the soil (Dubey & Nain, 2020). In traditional soil-based farming and planting, plants must expend a lot of energy developing their extensive root system because the roots must sift through the soil for minerals and water. In summary, whether they are growing in soil or not, plants require water and nutrients. These macronutrients and micronutrients are supplied directly to the plants in hydroponics, which is recommended by soilless farming. Meric et al., (2011) highlighted that soilless cultivation is commonly used to better regulate the growing environment, reducing uncertainties related to soil water and nutrient availability. It also addresses issues such as the build-up of salinity, pests, and diseases (Fan et al., 2012), and reduces environmental pollution caused by fertigation runoff (Savvas, 2002; Rouphael et al., 2006). Additionally, this approach helps conserve water and fertilizers, significantly improving crop water use efficiency (Schwarz et al., 1996; Zekki et al., 1996)., (Zhang et al.,2016). Vegetables are vital cash crops, significantly improving farmer income and nutrition. To meet the rising demand, vegetable cultivation must expand to all possible locations and methods (Dass et al., 2002, 2008). Hydroponic systems facilitate the growth of numerous plants and vegetables, particularly leafy greens, which thrive in soilless media due to their short lifespan and these leafy vegetables have a tender texture and are abundant in antioxidants, fibre, vitamins, and minerals offering protection against various diseases (Park et al., 2013). Hydroponic cultivation has recently gained global popularity due to its efficient resource management and high-quality produce (Sharma et al., 2018). Traditional soil-based agriculture faces challenges like urbanization, natural disasters, climate change, and indiscriminate chemical and pesticide use, posing environmental threats. The tomato is a globally significant vegetable crop. In 2013, global production was estimated at 163.96 million metric tons, with China and India leading production (FAOSTAT, 2015). Tomatoes are consumed in various forms, including fresh, cooked, and processed. Canning transforms them into products such as juice, pulp, paste, and sauces (Cuartero and Fernandez, 1999). Tomatoes are a key vegetable crop in South Africa, with hydroponic production increasing due to higher market returns and limited agricultural resources. As a vital source of vitamins A and C, and minerals, tomatoes are essential to the human diet. South African growers face the challenge of meeting local demand for high-yield, quality tomatoes. This is often hindered by poor cultivation, inadequate nutrition, adverse weather, and pests/diseases. To mitigate unfavourable conditions like hail and summer heat, farmers are increasingly using soilless systems under shade nets to optimize yield and quality (Jones, 2008). Applying optimal nutrient concentrations in greenhouse hydroponics improves spinach growth and enables continuous, year-round production (Acharya et al., 2021). A nutritious leafy vegetable, spinach (Spinacia oleracea) can be consumed fresh, frozen, canned, sliced, or cooked. Being a rich source of vitamins A, C, K, magnesium, manganese, iron, and folate, as well as riboflavin, pyridoxine, vitamin E, calcium, and potassium, it has a high nutritional value, especially when fresh, frozen, steamed, or quickly boiled. Compared to soil-based methods, it offers several advantages, such as faster and uniform plant development, higher average yields, balanced growth, freedom from soil-borne diseases, the elimination of harmful chemical use, and superior produce quality. While hydroponic techniques are not yet widely commercialized in India, they are gaining significant popularity globally, and within India, various institutions and private firms are actively conducting experiments and training programs to promote efficient hydroponic system management. The United States and the Asia-Pacific area are the next most significant producers of hydroponics, with France, the Netherlands, and Spain leading the European market. Soil-based cultivation faces challenges due to industrialization, urbanization, climate change, natural disasters, and excessive chemical use, leading to soil degradation (Jensen & Collins, 1985). To address these issues, scientists have developed hydroponics, a soil-less cultivation method where plants grow in a nutrient-rich water solution. This technique allows for large-scale cultivation of crops and vegetables with higher yield quality, better taste, and superior nutritional value compared to traditional soil-based farming. Hydroponics is cost-effective, disease-free, and eco-friendly, making it increasingly popular worldwide in both developed and developing countries. It also has potential applications in space research and regions with limited arable land. As a sustainable method, hydroponics could help meet global food demands and support future advancements in agriculture. The global hydroponic market is projected to grow by 18.8% from 2017 to 2023, reaching USD 490.50 million by 2023 (Jensen & Collins, 1985). According to growers, continuous crop production is possible only through hydroponic systems, as they allow year-round cultivation, require less space, and enable plant growth in small areas with controlled environments (Hughes, 2017). Hydroponics ensures higher productivity and yields without being affected by climate or weather conditions (Sarah, 2017). The quality of hydroponic produce is superior because controlled environments ensure uniform production while conserving water and nutrients (Okemwa, 2015). Moreover, hydroponics is not seasonal, leading to consistent productivity throughout the year (Okemwa, 2015). Hydroponic farming is also easier, as it eliminates the need for ploughing, weeding, soil fertilization, and crop rotation, making it a clean and efficient method (Nguyen et al., 2016). (Acharya et al.,2021). Different methods for water movement in hydroponic setups- The hydroponic system can be of 2 types; Open system- In open hydroponic systems, the nutrient solution flows through the plant roots and is then discarded. This “single pass” method eliminates recirculation. This practice minimizes the chance of infections spreading among plants due to the frequent replacement of fresh nutrient solution. (Jones, 2005) Closed-system hydroponics is a soil-free growing technique that uses a recirculating nutrient solution. In this system, the same nutrient mix is continuously recovered, replenished, and recycled until fully utilized by the plants. This method reduces water and fertilizer use by up to 80%, making it an efficient and sustainable approach to food production. Types of hydroponic system and their operation -In hydroponic farming, the water tank is the core component, providing the necessary nutrient rich water for plant growth. These tanks generally share a common design, focused on holding and distributing the nutrient solution. To ensure optimal plant health, many systems include a reverse osmosis (RO) unit to eliminate water hardness, which can negatively impact growth. However, tank designs can vary slightly depending on the specific hydroponic system, such as the ebb and flow method. Hydroponic systems are often modified for resource reuse, with common types including wick, ebb -flow, drip, deep water culture, and nutrient film technique described below. (Dubey, N., & Nain, V. 2020)., (Jan et al.,2020). Wick system -The simplest hydroponic systems operate without electricity, relying on a basic setup where plants are rooted in a growing medium such as coco coir, vermiculite, perlite with a nylon wick (Shresta and Dunn,2013). Ebb-flow is the early commercial hydroponic system utilized a flood and drain principle, where a pump delivered nutrient solution from a reservoir to the grow bed, flooding it to a predetermined level for nutrient and moisture delivery. However, despite its versatility in supporting various crops, this design was susceptible to root rot, algae, and Mold (Nielsen et al., 2006). Consequently, modified systems incorporating filtration were developed. Drip-Drip hydroponics offers a highly efficient method for delivering water and nutrients directly to plant roots, making it a popular choice for both home and commercial cultivation (Rouphael and Colla, 2005). By utilizing a pump and a moderately absorbent growing medium, this system ensures controlled, slow dripping, minimizing water waste and supporting the consistent growth of various crops. Deep water culture (DWC) hydroponics suspends plant roots directly in a nutrient-rich solution, with an air stone providing essential oxygenation. A common example is the hydroponic bucket system. Plants are housed in net pots, allowing their roots to immerse and rapidly develop a substantial mass within the solution. Rigorous monitoring of oxygen and nutrient concentrations, salinity, and pH is crucial (Domingues et al., 2012) to prevent the rapid proliferation of algae and Molds within the reservoir. DWC systems are particularly effective for larger, fruit-bearing plants such as cucumbers and tomatoes, which thrive in this environment. Nutrient film technique- Dr. Allen Cooper invented the Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) in England in the mid-1960s. It was made to fix problems with older water-based growing systems (Sharma et al.2018). In NFT, water with plant food constantly flows through channels where plant roots hang. The channels are tilted so the water flows over the roots and back to a tank. This lets plants get food and water all the time. While this can sometimes lead to root problems, NFT works well for growing leafy greens, especially lettuce (Domingues et al., 2012). While hydroponic systems offer numerous advantages, their expense often limits adoption by small farmers. However, cost-effective solutions exist. Gumisiriza et al. developed A basic, easy hydroponic system for leafy greens, designed for economic viability. Another example is the Kratky method (Kratky.,2005), which eliminates the need for pumps and electricity. Plants in mesh pots are grown with a nutrient solution, relying on capillary action for root moisture, making it ideal for intensive leafy vegetable cultivation. Plant growth directly corresponds to the reduction of the nutrient solution, creating more air space for the roots. Leafy vegetables are harvested before the solution is exhausted. This method is practical for small farmers because it requires minimal maintenance, no pumps, absence of climate monitoring systems and no extra labour (Kratky,2009). A key disadvantage is the requirement for regular nutrient solution monitoring, making this method best suited for small-scale, non-automated vegetable production. Hydroponics uses growing material without soil- The following qualities are necessary for the growing media to be used in a hydroponics system: It must serve as a source of nutrients for healthy plant development and growth. It should be able to contain a lot of water. must concurrently provide the plant with gas and water. It needs to give the plant support. Growing media that is organic-(Cocopeat) It is a coconut husk byproduct. Numerous soilless crops, including tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers, capsicums, spinach, water spinach, and others, can be produced with coconut peat without having a negative effect on the environment (Hussain et al., 2014). Hull of rice-A byproduct of milling rice is rice hulls. offer excellent drainage due to their lightweight nature. While similar in particle size and decomposition resistance to sawdust, rice hulls minimize nitrogen depletion in growing media. Availability permitting, rice hulls can be a valuable hydroponic substrate due to their slow decomposition, akin to coco coir. However, fresh rice hulls should be avoided due to potential contamination from rice, bacteria, fungal spores, weed seeds and decaying insects, Parboiled rice hulls (PRH), produced by drying after milling, are a preferred sterile option as they eliminate these contaminants (Shilpa et al.,2024). Inorganic growing media -Sand is a common hydroponic growing medium. Its fine particle size, smaller than gravel, slows drainage and enhances moisture retention. Sand is often combined with vermiculite, perlite, or coco coir to improve aeration for root development (Asao, 2012; Sharma et al., 2018). Vermiculite-Vermiculite, a heated and expanded hydrated magnesium aluminium silicate, is ideal for container media. Its unique, plate-like particles retain high amounts of water while promoting excellent aeration and drainage. This mineral also offers valuable cation exchange and buffering capacities and readily releases potassium and magnesium. Despite being less durable than sand or perlite, vermiculite’s chemical and physical characteristics make it a superior choice for many containers gardening application (Gaikwad and Maitra.,2020). Rock wool-Rockwool is an effective medium for seed germination. This mineral Fiber, made from melted basalt rock and recycled slag, provides a lightweight and convenient growing environment, resulting in a high germination rate, low insect attack ratio, and excellent aeration and moisture retention (Putra and Yuliando, 2015). This study explores the potential of small-scale hydroponic systems enhanced with optimized nutrient management strategies as a sustainable model for local food production. It aims to assess plant growth performance, resource efficiency, and the broader implications for sustainable agricultural practices and community-based food systems. Additionally, check the impact of three distinct nutrient formulations on the agronomic performance and yield of vegetable growth in a nutrient solution. Parallel experiment using soil cultivation as a control was conducted to assess the relative effectiveness of the nutrient solution system and the tested formulations.