1. Introduction

The European Union’s Smart Specialisation Strategy (RIS3) has become a cornerstone of cohesion policy, aiming to foster innovation-driven development by aligning regional potential with targeted investments. Central to this approach is the assumption that regions, regardless of their development level, possess unique strengths that can be unlocked through place-based, evidence-driven strategies. However, the effectiveness of RIS3 largely depends on how well the selected specialisations correspond to the socio-economic realities and structural conditions of a given region.

This article focuses on the Lubusz Voivodeship (Lubuskie) in western Poland — a region that, despite its location at the heart of the European Union and along major transport corridors, struggles with limited innovation capacity, institutional fragmentation, and a dispersed urban system. Building on the typological insights from ESPON and recent cohesion literature, Lubuskie is conceptualised here as a Structurally Weak but Non-Peripheral Region: a territory that is geographically central, yet structurally marginalised in terms of economic dynamism and absorptive capacity.

Such regions are not unique. Across the EU, there exists a broad category of structurally weak but strategically located territories that are often overlooked by cohesion and innovation policy frameworks. Examples include Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Germany, Molise in Italy, Limousin in France, or the Świętokrzyskie and Opolskie Voivodeships in Poland. Despite their proximity to major economic centres, these regions lack strong metropolitan anchors and face challenges in converting spatial advantage into development momentum

This analytical framing provides a critical lens through which to evaluate the region’s RIS3 choices. In structurally weak regions, the adoption of innovation priorities may be driven more by external expectations or aspirational policy goals than by endogenous economic specialisation. As such, there is a heightened risk of strategic misalignment between RIS3 documents and the actual composition of the regional economy.

To examine this hypothesis, the article applies a methodology adapted from Kudełko, Żmija, and Żmija [

1], which involves analysing changes in the regional employment structure using the Location Quotient (LQ) method. Employment data from two points in time — 2009 (pre-RIS3) and 2021— are used to assess whether the selected smart specialisations have a genuine economic base and whether their position has strengthened or weakened over time.

By focusing on a region that does not neatly fit into core-periphery models and is often overlooked in cohesion debates, this study seeks to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of RIS3 applicability in fragmented and structurally constrained environments. Moreover, the findings may prove relevant for policymakers and scholars interested in the development of similar structurally weak but non-peripheral regions across Europe, where the place-based logic of innovation policy must be reconciled with limited regional capacity.

The central research question addressed in this article is: To what extent do the RIS3 priorities in the Lubusz Voivodeship reflect the actual structure and dynamics of its regional economy? The article is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and conceptual framework.

Section 3 presents the methodology and data sources.

Section 4 provides a regional profile of Lubuskie.

Section 5 presents the results of the LQ analysis.

Section 6 discusses the findings, and

Section 7 concludes with policy implications and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Smart Specialisation Strategies (RIS3) and the Place-Based Approach

The Smart Specialisation Strategy (RIS3) emerged from the European Commission’s commitment to foster regional innovation through place-based, evidence-driven development. RIS3 encourages regions to identify priority areas where they have a competitive advantage and to channel public investments accordingly. The conceptual foundation of RIS3 draws on the work of Foray et al. [

2] and the Barca Report [

3], emphasizing endogenous development, stakeholder participation, and entrepreneurial discovery. While widely adopted in EU cohesion policy, RIS3 has also been critiqued for favoring more developed or institutionally mature regions, which are better equipped to implement complex innovation policies.

Critics point out that lagging or structurally weaker regions often lack the institutional capacity, entrepreneurial base, and innovation networks necessary to operationalize RIS3 effectively. As a result, the strategy may unintentionally reinforce existing territorial disparities rather than alleviate them [

4,

5,

6].

2.2. Typologies of European Regions: Core–Periphery and Beyond

Traditional regional typologies, such as the core–periphery model, distinguish between high-performing metropolitan centers and economically weaker peripheral areas. However, recent literature [

7,

8,

9,

10] has identified a growing number of regions that do not fit neatly into these categories. These territories often suffer from inadequate infrastructure, fragmented governance, and limited institutional capacity—despite being geographically close to economic cores. They typically fall outside the scope of both metropolitan-focused policies and those designed for peripheral areas, leading to their systematic neglect in regional development strategies. Examples of such regions in Europe include border areas in northeastern Germany, parts of central Italy, eastern France, and—within Poland—the Lubusz Voivodeship.

Analyses by ESPON [

7,

8] indicate that categories such as inner peripheries and sideways innovation-poor regions encompass a significant number of NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 territories in Central and Eastern Europe. These regions are characterised by low infrastructure accessibility, weak integration into national innovation networks, and dispersed settlement patterns. Similarly, the OECD [

9] introduces the concept of non-core or near-core peripheral regions, highlighting the risk of widening spatial inequalities within these “in-between” territorial types.

2.3. The RIS3 Challenge in Structurally Constrained Regions

Empirical studies on RIS3 implementation in less-developed regions [

11,

12] highlight the difficulties of aligning innovation strategies with actual economic and institutional capacities. Structurally weak regions face barriers such as limited stakeholder engagement, insufficient data, and aspirational policy design that often lacks empirical grounding. This raises the question of whether RIS3 can truly function as a place-based policy when the place in question lacks the necessary foundations for discovery and specialisation.

In many such regions, entrepreneurial discovery processes are hampered by fragmented governance, a weak innovation culture, and a lack of intermediary institutions capable of facilitating coordinated action. The strategic documents that emerge often mirror national or global trends rather than local realities, resulting in “copy–paste” specialisation domains with little endogenous basis. Moreover, limited absorptive capacity restricts the region’s ability to benefit from knowledge spillovers, further weakening RIS3’s transformative potential.

In this context, the challenge lies not only in designing smart specialisation strategies, but in making them feasible within structurally constrained environments. As recent literature suggests, RIS3 needs to be rethought for these regions—not as a standardised framework, but as a flexible, capacity-building tool that integrates both local limitations and opportunities for external support and cross-regional collaboration [

13,

14].

2.4. Research Gap and Theoretical Anchoring

Despite the strategic importance of RIS3, relatively little attention has been paid to how smart specialisation strategies operate in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions. The case of Lubuskie offers an opportunity to explore this gap, combining a theoretical framing grounded in regional typologies with a quantitative evaluation of sectoral employment patterns. By adapting the LQ-based approach proposed by Kudełko et al. [

1], this study aims to assess whether the RIS3 priorities adopted by Lubuskie reflect its real economic structure — and what this implies for other similarly positioned regions in the EU.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Objective and Strategy

The aim of this study is to assess the extent to which the smart specialisation priorities (RIS3) adopted in the Lubusz Voivodeship correspond to the actual economic structure of the region. The analysis adopts a comparative, quantitative approach based on employment data from 2009 (pre-RIS3) and 2021 (the latest available year). The year 2009 was selected as the baseline due to the introduction of the PKD 2007 classification and the absence of RIS3 influence. The year 2021 was selected as the latest point of reference due to a fundamental methodological change in Polish employment statistics after that year. Starting from 2022, employment data are derived from administrative sources, include all business entities regardless of size, and are aggregated by place of residence rather than workplace location. This change makes post-2021 data incomparable with the 2009 baseline based on the Z-06 survey. Consequently, 2021 is the most recent year that allows for fully consistent comparison with the pre-RIS3 period.

An initial analysis of regional economic potential identified five key technological and service areas. However, a broad consultation process with stakeholders led to the narrowing of priorities to three Smart Specialisation Areas. This decision reflected the need for resource concentration, recognition of sectoral diversification, and alignment with European Commission guidelines [

15].

As a result, the Lubusz Voivodeship formally adopted three specialisations: Innovative Industry, Health and Quality of Life, and Green Economy, designed to integrate related sectors and promote inter-sectoral cooperation.

3.2. Data Sources and Sectoral Classification

The analysis is based on employment data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS), specifically drawn from the Z-06 statistical report on employment by sector. The data is aggregated at the 2-digit level of the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD 2007), which is compatible with the European NACE Rev.2 standard. This level of aggregation allows for sufficient sectoral detail while maintaining comparability across time periods. National-level data is used as a reference point to compute relative specialisation for the Lubusz region.

3.3. Analytical Method: Location Quotient (LQ)

The Location Quotient (LQ) is a standard tool for identifying relative sectoral specialisation within a given region. The LQ for sector i is calculated as follows:

where:

—number of employees in sector i in the Lubusz Voivodeship

– total number of employees in the Lubusz Voivodeship;

—number of employees in sector i in Poland;

—total number of employees in Poland;

An LQ > 1 indicates that the sector is more concentrated in the region than in the country as a whole. In regional innovation analysis, LQ thresholds of 1.25–1.30 are often used to identify strong or emerging specialisations [

1,

9].

3.4. Operationalisation and Limitations

The analysis compares LQ values across the two reference years to determine whether regional specialisation in RIS3 sectors has strengthened, weakened, or remained stable. Only those sectors for which comparable data exist for both years are considered. It is acknowledged that employment data alone cannot capture all dimensions of innovation potential (e.g., R&D expenditure, patent activity, firm creation), but it serves as a reliable proxy for structural economic alignment.

Possible limitations include changes in sector classification over time, potential data inconsistencies, and the challenge of interpreting borderline LQ values (i.e., between 1.15 and 1.30). These are mitigated by applying consistent classification and cross-checking aggregated sectoral trends.

4. Regional Context: Lubuskie as a Structurally Weak but Non-Peripheral Region

4.1. Geographical and Institutional Fragmentation

One of the defining characteristics of the Lubuskie Voivodeship is its fragmented territorial and institutional structure. Unlike most Polish regions, Lubuskie does not have a single dominant regional capital but is instead administered jointly by two cities—Zielona Góra and Gorzów Wielkopolski. This dual-capital arrangement, rooted in the administrative reform of 1999 and designed as a political compromise, has led to a bifurcation of regional governance and a dispersed identity.

Instead of functioning as a unified urban core, the two cities often operate in parallel, reflecting their distinct administrative roles and institutional mandates. While Zielona Góra serves as the seat of the regional self-government and Gorzów Wielkopolski hosts the voivode’s office, the absence of a joint strategic platform between them limits opportunities for integrated planning and coordinated regional development. This functional separation weakens the region’s ability to consolidate political will and articulate a coherent territorial vision. As a result, Lubuskie lacks the metropolitan cohesion found in regions with a single strong urban centre, such as Wrocław in Lower Silesia or Poznań in Greater Poland.

This fragmentation has far-reaching implications. First, it limits the agglomeration economies that could otherwise support innovation-driven growth. Second, it dilutes the region’s bargaining power in national and EU-level negotiations, weakening its visibility and strategic positioning. Third, it complicates the formation of innovation ecosystems, which typically rely on concentrated knowledge institutions, networks of firms, and regional leadership.

In the context of RIS3, these institutional divisions create additional barriers to effective stakeholder mobilisation, entrepreneurial discovery, and strategic policy alignment. The absence of a unified regional centre makes it difficult to anchor innovation strategies in a clear territorial narrative, resulting in a fragmented implementation framework that struggles to deliver transformative outcomes.

4.2. Lubuskie in the National and Macro-Regional Landscape

The spatial position of Lubuskie within Poland places it between two of the country’s most dynamic and institutionally mature regions: Lower Silesia to the south and Greater Poland to the east. These neighbouring voivodeships are home to major urban centres—Wrocław and Poznań respectively—which serve as national hubs of innovation, higher education, and economic development. In contrast, Lubuskie lacks a comparable urban engine, which limits its competitiveness and ability to attract investment, talent, and political attention.

This intermediary position creates a structural disadvantage. Lubuskie is not peripheral in a geographical sense—it lies close to the German border and along trans-European transport corridors. Yet, it is functionally peripheral in terms of economic integration and institutional influence. The region frequently loses out in interregional competition for EU funding [

16], foreign direct investment [

17], and skilled labour [

18]. Its proximity to stronger neighbours often results in a leakage of resources and a shadowing effect, where regional initiatives are overshadowed by those of more prominent actors.

The consequence is a form of “territorial liminality”: Lubuskie is neither part of the economic core nor does it benefit from the compensatory focus typically directed at peripheral regions. This position in-between makes it difficult to define a clear developmental path, particularly in the context of strategies like RIS3 that rely on region-specific strengths and stakeholder coordination. The region’s hybrid status—central in space but marginal in function—exemplifies the challenges faced by structurally weak but non-peripheral regions across Europe.

4.3. ESPON Classifications and Territorial Typologies

Recent ESPON studies have shed new light on the diversity of regional development trajectories across Europe, challenging the traditional dichotomy between core and peripheral regions [

19]. Within this evolving typological landscape, the Lubuskie Voivodeship has emerged as a notable example of a structurally weak but non-peripheral region—an area located close to economic cores but lacking the institutional and economic density required to fully participate in innovation-driven growth.

According to the ESPON (2021) classification on regional innovation readiness, Lubuskie is internally divided between two categories. The northern part, centred around Gorzów Wielkopolski, is labelled as a “Sideways Innovation-Poor Region” [

20]. This category includes areas that are not entirely disconnected from innovation networks but remain weakly integrated into national or European innovation systems. Their capacity to mobilise stakeholders and implement smart specialisation strategies is considered marginal.

Meanwhile, the southern subregion, with Zielona Góra as its main urban node, is classified as “Not an IP Region”—meaning it does not actively participate in or benefit from smart specialisation processes. This typology points to very low levels of institutional engagement, innovation capacity, and strategic integration with RIS3 policy mechanisms.

These designations reflect more than just quantitative differences in innovation outputs. They reveal structural issues such as fragmented governance, lack of interregional coordination, and minimal anchoring in broader knowledge-based networks. Moreover, the internal divide within the region echoes the broader duality of Lubuskie’s territorial organisation, reinforcing the sense of strategic incoherence.

Importantly, these findings suggest that RIS3 implementation in such regions cannot rely on standardised frameworks. Instead, it requires adaptive, territorially sensitive approaches that take into account the region’s hybrid typology and institutional asymmetries.

4.4. Initial Conditions for RIS3 Implementation

The starting conditions for implementing smart specialisation strategies in Lubuskie are shaped by a combination of structural constraints and institutional fragmentation. As discussed in previous sections, the region lacks a consolidated metropolitan centre, exhibits internal functional divisions, and suffers from low integration into national and European innovation networks.

Institutionally, the region demonstrates weak capacity for strategic coordination. Although several actors are formally involved in the RIS3 process—such as regional government departments, business support organisations, and academic institutions—their collaboration remains limited in scope and often project-driven rather than systemic. The entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP), a cornerstone of RIS3 design, has struggled to gain traction due to limited stakeholder mobilisation, insufficient analytical capacity, and the absence of stable intermediary platforms that could facilitate ongoing dialogue between public, private, and research sectors.

Data from national and European sources also indicate that Lubuskie lags behind in terms of innovation inputs. The region’s R&D expenditure is among the lowest in Poland, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP [

21]. Similarly, the number of patent applications, innovation-active firms, and participation in EU innovation programmes is relatively low compared to the national average [

22]. These indicators suggest that RIS3 in Lubuskie must contend not only with structural underdevelopment but also with a fragile ecosystem for knowledge generation and diffusion.

Moreover, the fragmented governance structure—in part a consequence of the dual-capital arrangement—further complicates policy implementation. Competing local priorities, limited inter-municipal cooperation, and low political continuity have all hindered the development of a coherent innovation vision. As a result, the region entered the RIS3 cycle without the institutional foundations that would enable it to treat smart specialisation as a transformative agenda rather than a compliance-driven exercise.

This context must be fully acknowledged when evaluating the actual alignment between the region’s RIS3 priorities and its economic base. It also reinforces the broader argument that structurally weak but non-peripheral regions require tailored policy approaches that move beyond the formal frameworks of RIS3 and into long-term capacity-building efforts.

5. Results

5.1. Overview of LQ Dynamics, 2009–2021

Table 1 below presents the computed Location Quotients (LQ) for each two-digit PKD sector in Lubuskie in 2009 and 2021, together with the change (ΔLQ = LQ₍₂₀₂₁₎—LQ₍₂₀₀₉₎). A value LQ > 1 indicates a sector relatively more concentrated in Lubuskie than in Poland as a whole; ΔLQ > 0 signals a strengthening of that concentration over the 12-year period.

5.2. Pre-RIS3 Specialisations (LQ 2009)

In 2009, several sectors already exhibited strong regional concentration (LQ ≥ 1.25), notably:

C.15 (Leather and related products): LQ = 3.22;

C.16 (Wood products): LQ = 3.15;

C.17 (Paper products): LQ = 2.11;

C.29 (Motor vehicles): LQ = 3.16;

C.26 (Electronics): LQ = 2.57.

These high initial LQ values indicate that, prior to the formal launch of RIS3, the Lubuskie economy was already structurally oriented towards manufacturing, especially of wood, leather, paper and transport equipment.

5.3. Post-RIS3 Dynamics (LQ 2021)

By 2021, the pattern of regional specialisation had shifted:

Newly emergent strengths (LQ₍₂₀₂₁₎ ≥ 1.25 but ΔLQ > 0):

Consolidated manufacturing leaders (LQ ≥ 1.25 despite small ΔLQ):

Declining or de-specialised sectors (ΔLQ < –0.20):

C.29 (Motor vehicles): –0.85;

C.16 (Wood products): –0.22;

D.35 (Energy supply): –0.27.

Thus, while traditional manufacturing sectors retain their relative weight, there has been pronounced growth in metal fabrication (C.25) and—notably—social work services (Q.88), the latter previously absent as a regional specialisation in 2009.

5.4. Alignment with RIS3 Priorities

Lubuskie’s three RIS3 priority domains are:

Innovative Industry (e.g., C.25, C.28);

Health and Quality of Life (e.g., Q.86–Q.88);

Green Economy (e.g., E.36, E.38).

Our LQ dynamics reveal:

Partial validation of “Innovative Industry”:

Strong evidence supporting “Health and Quality of Life”:

Modest growth in “Green Economy” sectors (e.g., E.36: +0.03; E.38: +0.02), suggesting further policy focus may be needed.

Overall, the dynamic LQ analysis confirms that two of the three RIS3 domains—metal fabrication and social services—have indeed strengthened their regional foothold, while other manufacturing and green sectors show mixed or limited gains.

5.5. Dynamic Consolidation of Specialisations

Finally, the number of sectors with LQ ≥ 1.25 increased from five in 2009 to seven in 2021, indicating a modest consolidation of regional specialisations. This trend reflects a gradual strengthening of both established industrial sectors and emerging service-oriented specialisations. However, the simultaneous decline of certain legacy industries (wood products, motor vehicles) underscores the need for continuous policy adaptation to support a balanced, innovation-driven specialisation mix.

Table 1 and the accompanying analysis provide a clear, self-contained picture of how Lubuskie’s economic structure has evolved over the RIS3 period and how this evolution maps onto the region’s officially adopted smart specialisation priorities. These findings serve as the empirical basis for the subsequent discussion on the adequacy of RIS3 strategies in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions (

Section 6).

6. Discussion and Implications for RIS3 Design and Implementation

The full complexity of Lubuskie’s evolving economic structure was assessed by calculating Location Quotients for each two-digit PKD sector (

Table 1), which enabled the identification of both established and transitional industrial niches. For clarity, the relevant sectors were subsequently grouped into three smart specialisation domains, as outlined in Annex 2 of the RIS3 Lubuskie strategy (2019) [

23]: Innovative Industry (C.25, C.28), Health & Quality of Life (Q.86–Q.88), and Green Economy (E.36, E.38).

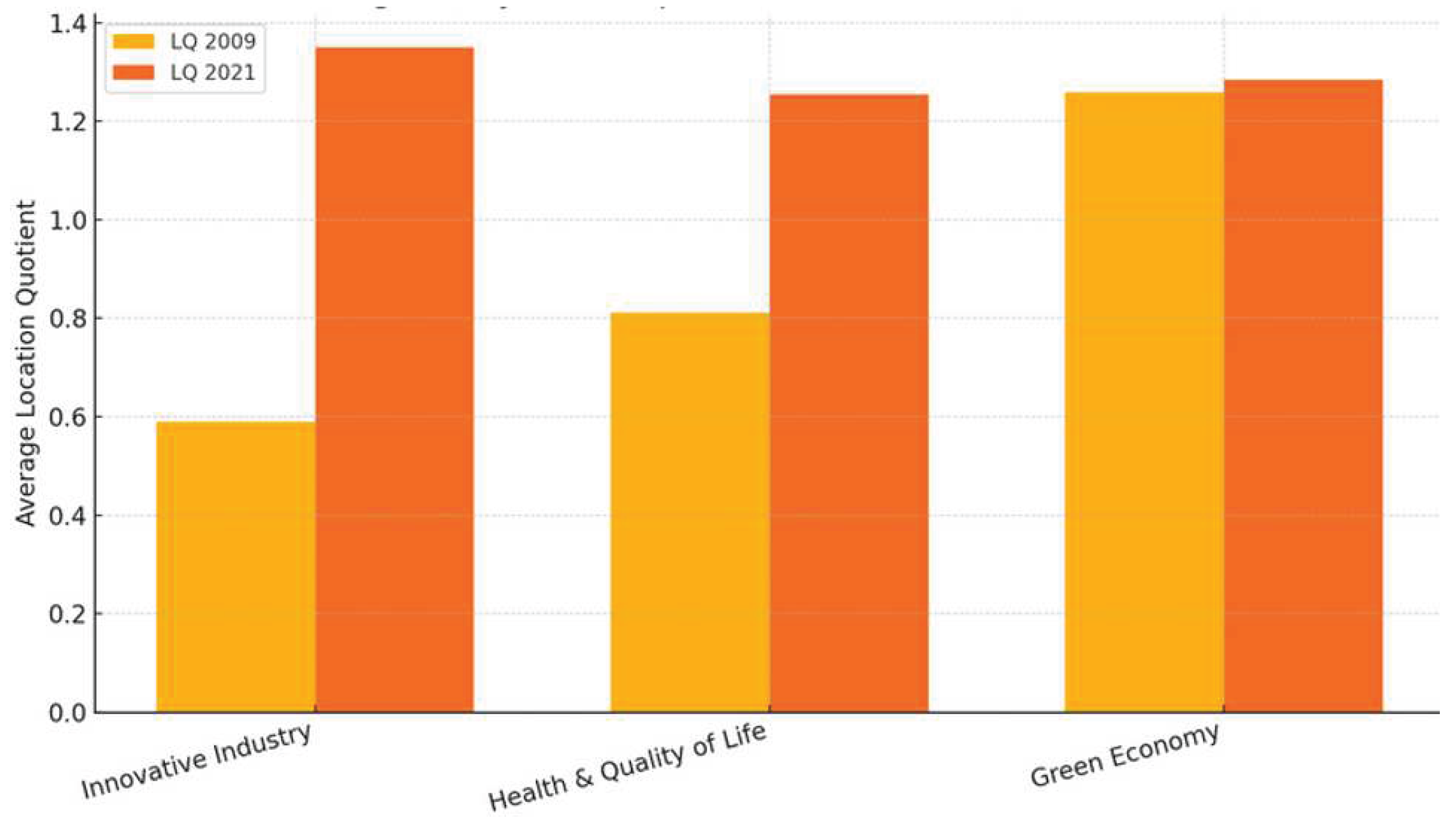

Figure 1 displays the average LQ for each domain in 2009 and 2021, clearly showing strong increases in Innovative Industry and Health & Quality of Life alongside only modest gains in the Green Economy. This visual summary not only confirms the alignment of emergent regional strengths with the strategic priorities, but also highlights where further policy support—for example, to boost green innovation—may be required.

6.1. Adequacy of RIS3 Priorities Relative to the Region’s Structure.

The LQ analysis has revealed that the priorities set out in the Lubuskie RIS3 strategy largely reflect the region’s actual economic potential and assets. The “Innovative Industry” domain—embodied, for example, by sectors C.25 and C.28—gained in relative importance between 2009 and 2021, confirming the soundness of this choice of specialisations. At the same time, the sustained high concentration in sectors C.15, C.17 and C.29 indicates that traditional manufacturing remains a key pillar of the local economy. Meanwhile, the “Health and Quality of Life” domain has been strengthened primarily by social work services (Q.88), which, although not recognised as a specialisation in 2009, have become one of the fastest-growing fields. By contrast, the “Green Economy” showed only modest growth (E.36, E.38), suggesting the need to bolster instruments that support green innovation and ecological transformation.

6.2. Mechanisms Strengthening New and Traditional Specialisations

The transformation observed in the metal fabrication sector (C.25) can be attributed primarily to targeted support for SMEs under the Lubuskie Regional Operational Programme, which enabled investments in precision metalworking technologies. Rising demand for industrial components further reinforced this sector’s market position, translating into a significant increase in its LQ—from 0.14 in 2009 to 1.52 in 2021.

However, the most dramatic growth occurred in social work activities without accommodation (Q.88), where LQ climbed from 0.13 to 1.41. In addition to the expansion of NGO networks and municipal support programs for socially excluded groups, the decisive factor was the explicit inclusion of this field in both the Lubuskie 2030 Development Strategy and the ex-ante evaluation of RPO WL 2021–2027. By prioritizing social inclusion, the region launched dedicated grant calls and streamlined funding access for day-service centers, social counselling, and reintegration programs—greatly accelerating the sector’s development.

At the same time, a weakening of traditional industries, notably wood products (C.16) and motor vehicles (C.29), is observed., which lost 0.22 and 0.85 LQ points, respectively. These declines point to barriers in modernizing machinery, limited access to advanced technologies, and intense global competition. The misalignment of support instruments with these industries’ specific needs has hampered their ability to maintain previously strong regional concentrations.

By combining these insights—the successes of C.25 and Q.88 alongside the challenges faced by C.16 and C.29— a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms is gained that are reinforcing emerging specialisations while constraining legacy sectors.

6.3. Implementation Barriers and Policy Gaps

While regional structures such as the Western Poland Horizon Europe Contact Point and individual grant schemes suggest some level of coordination, no systematic evaluation has yet been conducted in Lubuskie regarding the effectiveness of cooperation between RPO managing bodies, Horizon Europe actors, and national innovation programmes. The European Parliament’s 2025 study highlights that, despite formal procedures for pooling ROP and Horizon funds, genuine inter-institutional coordination often remains weak, and the Commission’s 2022 guidance on “Synergies between Horizon Europe and ERDF programmes” warns that without close cooperation between cohesion fund managers and research programme bodies, priorities can become misaligned and activities may be duplicated.

Assuming these general findings apply to Lubuskie, it would be prudent to strengthen coordination mechanisms—for example, by establishing joint planning platforms between the Marshal’s Office departments and research institutions, or by deploying enhanced project-synergy monitoring tools. Such measures could reduce fragmentation of support and improve the efficiency of fund allocation toward targeted smart specialisations.

At the same time, the ex-ante evaluation of Lubuskie’s RPO 2021–2027 notes that only a small share of ERDF-funded operations involve substantial R&D in the green economy, with most support directed to technical assistance (e.g., energy audits or project documentation) (RPO WL Ex-ante Evaluation 2021–2027). This suggests that local universities and research centres are not sufficiently engaged in green innovation initiatives, limiting the region’s capacity to generate breakthrough ecological solutions. Strengthening their involvement through dedicated calls for green R&D projects and formalised partnerships could accelerate progress in renewable energy, water management and circular-economy technologies.

6.4. Recommendations for Structurally Weak but Non-Peripheral Regions

Based on the above findings, it is advisable to undertake regular RIS3 priority reviews every three to four years, enabling flexible responses to emerging high-growth potential sectors such as social services [

24].

Moreover, scaling up support for the green economy through dedicated clusters, grants, and incubator programmes for startups in renewable energy, water management, and the bioeconomy is essential [

25].

Finally, strengthening public-private partnerships and deepening linkages among regional authorities, industry, and academia will facilitate more effective knowledge and technology transfer, in line with the pivotal role of clusters in building innovative ecosystems [

26].

6.5. Research Limitations and Further Development Directions

The cross-sectional description of LQ changes presented here is based on only two time points and aggregated at the 2-digit PKD level, which may obscure short-term fluctuations and the specificity of highly specialized niches. Future research would benefit from extending the analysis to include firm-level microdata, value-added indicators, and additional years to obtain a more comprehensive picture of specialisation evolution. Additionally, case studies of key industrial and service clusters could yield deeper insights into the mechanisms of success and implementation barriers.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Research Findings

This study has demonstrated that the Lubuskie RIS3 priorities broadly align with the region’s underlying economic structure, while also revealing critical mismatches. The Location Quotient analysis shows that two of the three chosen domains—Innovative Industry and Health & Quality of Life—have indeed strengthened their foothold between 2009 and 2021. Metal fabrication (C.25) leapt from an LQ of 0.14 to 1.52, and social work services without accommodation (Q.88) surged from 0.13 to 1.41, reflecting both targeted policy support and growing social needs. Traditional manufacturing sectors (e.g., leather, paper, motor vehicles) remain important but in some cases have weakened, while the Green Economy domain registered only marginal LQ gains (E.36, E.38). Finally, the number of strong specialisations (LQ ≥ 1.25) increased from five to seven, indicating a modest consolidation of regional strengths—even as legacy industries faced competitive pressures.

7.2. Limitations and Further Research Needs

Several methodological and data constraints temper these conclusions. First, the analysis is based on employment data from only two points in time and aggregated at the 2-digit PKD level, which may mask short-term fluctuations, intra-sectoral dynamics, and the performance of narrowly defined niches. Second, employment shares do not fully capture innovation capacity; indicators such as R&D intensity, patent activity or value-added per worker could yield richer insights. Third, the study does not directly observe the mechanics of the entrepreneurial discovery process or stakeholder engagement—dimensions that qualitative case studies could illuminate. Future research should therefore extend the time series (e.g., include 2025–2030 data), incorporate firm-level microdata and innovation metrics, and undertake in-depth cluster or policy-process case studies to unpack the drivers of success and the nature of implementation barriers in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions.

7.3. Recommendations for Regional Policy and RIS3 in “In-Between” Regions

For regions that are centrally located yet structurally constrained, our findings suggest three key adjustments to enhance RIS3 impact:

Dynamic Priority Reviews: Introduce formal RIS3 update cycles every three to four years to incorporate emerging high-potential domains—such as social services—and to retire or recalibrate underperforming sectors.

Strengthened Green Innovation Instruments: Scale up dedicated support for the Green Economy through thematic clusters, R&D co-funding schemes, and incubator programmes targeting renewable energy, water management and circular-economy ventures. This should be complemented by calls that explicitly require academic-industry partnerships to activate local research capacities.

Enhanced Multi-Level Coordination and Capacity Building: Establish joint planning platforms across RPO managing authorities, Horizon Europe intermediaries and national innovation agencies, and invest in intermediary organisations (e.g., technology transfer offices, cluster managers) to facilitate knowledge exchange. Tailored capacity-building for SMEs and public institutions—covering grant writing, project management and networking—will help “in-between” regions overcome institutional fragmentation and better harness cohesion and innovation funds.

By adopting these measures, structurally weak but non-peripheral regions like Lubuskie can more effectively translate their latent assets into sustainable, innovation-driven growth—bridging the gap between geographic centrality and economic dynamism.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Location Quotients (LQ) by PKD Sector in Lubusz Voivodeship: 2009 vs. 2021.

Table A1.

Location Quotients (LQ) by PKD Sector in Lubusz Voivodeship: 2009 vs. 2021.

| PKD (2-digit) |

Sector description |

LQ 2009 |

LQ 2021 |

ΔLQ |

| B (05-09) |

Mining and quarrying |

0,1958 |

0,0962 |

-0,0996 |

| C.13 |

Textile manufacturing |

1,7776 |

1,6551 |

-0,1226 |

| C.15 |

Leather and related products |

3,225 |

3,3417 |

0,1167 |

| C.16 |

Wood products |

3,1484 |

2,931 |

-0,2174 |

| C.17 |

Paper and paper products |

2,1103 |

2,2888 |

0,1785 |

| C.23 |

Manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products |

1,7328 |

1,4931 |

-0,2396 |

| C.25 |

Fabricated metal products (excl. machinery and equipment) |

0,1366 |

1,5203 |

1,3837 |

| C.26 |

Computer, electronic and optical products |

2,5692 |

2,2328 |

-0,3364 |

| C.28 |

Machinery and equipment n.e.c. |

1,0418 |

1,1805 |

0,1387 |

| C.29 |

Motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers |

3,1582 |

2,3045 |

-0,8537 |

| C.30 |

Other transport equipment |

0,2781 |

0 |

-0,2781 |

| C.31 |

Furniture |

1,6319 |

1,9108 |

0,2789 |

| C.32 |

Other manufacturing |

0,6951 |

0,9172 |

0,2222 |

| C.33 |

Repair and installation of machinery and equipment |

0,6446 |

0,4607 |

-0,1839 |

| D.35 |

Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply |

0,4207 |

0,1552 |

-0,2654 |

| E.36 |

Water collection, treatment and supply |

1,6458 |

1,6768 |

0,0311 |

| E.37 |

Sewerage; waste treatment and disposal |

1,5379 |

0 |

-1,5379 |

| E.38 |

Waste collection, treatment and disposal; materials recovery |

0,8719 |

0,8922 |

0,0203 |

| E.39 |

Remediation and other waste management services |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| J.62 |

Computer programming, consultancy and related activities |

0,4603 |

0,2628 |

-0,1975 |

| Q.86 |

Human health activities |

0,931 |

0,8346 |

-0,0964 |

| Q.87 |

Residential care activities |

1,3714 |

1,5156 |

0,1442 |

| Q.88 |

Social work activities without accommodation |

0,1309 |

1,4127 |

1,2818 |

References

- Kudełko, J.; Żmija, K.; Żmija, D. Regional smart specialisations in the light of dynamic changes in the employment structure: the case of a region in Poland. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 2022, 17, 133–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D.; David, P. A.; Hall, B. H. Smart Specialisation: From Academic Idea to Political Instrument, the Surprising Career of a Concept and the Difficulties Involved in its Implementation. MTEI Working Paper EPFL Lausanne 2011. Available online: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/170252.

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations; European Commission, 2009; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/pdf/report_barca_v0306.pdf.

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialisation, Regional Growth and Applications to EU Cohesion Policy. IEB Working Paper 2011, 2011/14. Available online: https://ieb.ub.edu/en/publication/smart-specialisation-regional-growth-and-applications-to-eu-cohesion-policy/.

- Barzotto, M.; Corradini, C.; Fai, F. M.; Labory, S.; Tomlinson, P. R. Enhancing Innovative Capabilities in Lagging Regions: An Extra-Regional Collaborative Approach. JRC Working Papers on Territorial Modelling and Analysis 2019, 01/2019. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC115401. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. Shrinking rural regions in Europe—Towards smart and innovative approaches to regional development challenges in depopulating rural regions. ESPON Policy Brief, 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/rural-shrinking.

- ESPON. Territorial Evidence and Policy Advice for Regions with Geographical Specificities. Final Report 2021. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/geographical-specificities.

- OECD. A New Rural Development Paradigm for the 21st Century: A Toolkit for Developing Countries; OECD Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F.; Trippl, M. One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy 2005, 34, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Asheim, B. T. Place-based innovation policy for industrial diversification in regions. European Planning Studies 2018, 26, 1638–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. The early experience of smart specialisation implementation in EU cohesion policy. European Planning Studies 2016, 24, 1407–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzotto, M.; Corradini, C.; Fai, F. M.; Labory, S.; Tomlinson, P. R. Enhancing Innovative Capabilities in Lagging Regions: An Extra-Regional Collaboration Approach to Smart Specialisation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2019, 12, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialisation, Entrepreneurship and SMEs: Issues and Challenges for a Results-Oriented EU Regional Policy. Small Business Economics 2016, 46, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship. Smart Specialisations of the Lubusz Region [Inteligentne specjalizacje województwa lubuskiego]. Zielona Góra: Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship 2015.

- European Commission. Annex to the Proposal for a Council Recommendation on the 2023 National Reform Programme of Poland and delivering a Council opinion on the 2023 Convergence Programme of Poland—Country Report Poland 2023. SWD(2023) 621 final, Brussels. 2023. Available online: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-05/PL_SWD_2023_621_1_en.pdf.

- OECD. Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Poland. OECD Publishing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuratowicz, A. Growing wage inequalities in Poland: Could foreign investment be part of the explanation? ECFIN Country Focus 2005, 2. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication1461_en.pdf.

- ESPON. Territorial Evidence and Policy Advice: ESPON 2020 Programme Overview. ESPON EGTC, 2021. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/programme/overview.

- ESPON. Regional Innovation Readiness: Typologies and Policy Implications. ESPON EGTC, Luxembourg, 2021. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/rir.

- ESPON. Territorial Patterns and Relations in Poland. ESPON EGTC, Luxembourg, 2021. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/pl/poland-2021.

- European Commission. Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Lubuskiego 2030. Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship, Zielona Góra 2019. Available online: https://bip.lubuskie.pl/strategia_rozwoju_wojewodztwa_lubuskiego_2030/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Commission. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3). Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, 2012.

- OECD. Policies to Support Green Entrepreneurship. OECD Publishing 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Clusters, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. OECD Publishing 2009. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).