1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Obesity has emerged as a critical global health concern, affecting individuals across all age groups and geographic regions. In 2022, more than 1 billion people worldwide—equivalent to one in eight—were living with obesity, with adult rates more than doubling and childhood and adolescent rates quadrupling since 1990 [

1,

2]. If current trends continue, projections indicate that over half the global population will be overweight or obese within the next 12 years, with the prevalence of obesity alone expected to rise from 14% to 24% by 2035, affecting nearly 2 billion people [

2] 3] . Notably, the increase in obesity is steepest among children and adolescents: the percentage of boys affected is projected to double from 10% to 20% and girls from 8% to 18% between 2020 and 2035 [

3]. The burden is not limited to high-income countries; rapid increases are also observed in low- and middle-income nations, particularly in Asia and Africa, where childhood overweight rates have surged by nearly 24% since 2000 [

4].

Obesity is a multifactorial chronic disease with complex physiological, psychological, and socioeconomic implications. It is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, and several cancers [

1,

2]. The economic impact is substantial, with annual global healthcare costs attributable to obesity exceeding

$2 trillion [

3]. Despite a strong evidence base for effective interventions, implementation remains patchy, and the epidemic continues to escalate [

1].

Early detection and intervention are paramount, as obesity often leads to progressive impairment in physical function, quality of life, and long-term health outcomes [

1,

2]. Traditional screening methods, such as body mass index (BMI), provide only a static snapshot and may not capture the early biomechanical changes linked to excess weight. Increasing evidence highlights the importance of functional markers—especially those related to movement and gait—as early indicators of obesity-related health risks [

5,

6].

1.2. Gait as a Diagnostic Tool

Human gait is a complex, dynamic process that reflects the integration of neuromuscular, skeletal, and metabolic systems. In the context of obesity, gait analysis has emerged as a valuable tool for identifying early biomechanical alterations that precede clinical symptoms [

5]. Obese individuals—both adults and children—consistently demonstrate distinct gait characteristics: reduced stride length, slower walking speed, increased double support time, and greater asymmetry in joint loading, particularly at the hip, knee, and ankle [

5]. These changes are not merely compensatory responses to increased body mass; they are also predictive of future musculoskeletal complications, reduced mobility, and diminished quality of life.

Recent studies using inertial measurement units (IMUs) and deep learning models have shown that gait patterns can accurately differentiate between normal-weight and obese adolescents, achieving classification accuracies as high as 97% [

6]. Obese individuals exhibit shorter step lengths, slower speeds, and greater variability in gait, supporting the use of gait metrics as sensitive markers for early detection and monitoring of obesity-related functional decline [

5,

6]. Unlike static measures such as BMI or waist circumference, gait analysis provides a dynamic assessment of how excess weight affects daily movement and joint stress.

However, traditional gait analysis methods—such as marker-based motion capture systems and force plates—are often expensive, time-consuming, and limited to specialized laboratories. These constraints have historically restricted the use of gait analysis in routine clinical or community-based screening.

1.3. Shift in Technology: Toward Optical and Computational Sensing

Technological advances over the past decade have transformed the landscape of biomechanical assessment. Optical sensor systems, including RGB-D cameras (e.g., Microsoft Kinect, Intel RealSense), stereo vision, and monocular camera setups, now enable robust, markerless motion capture in real-world environments. These systems, when integrated with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms, allow for the extraction of detailed gait and posture metrics from simple video or depth data, making large-scale, non-invasive health screening feasible and cost-effective.

Markerless pose estimation frameworks—such as OpenPose, MediaPipe, and HRNet—can extract 2D or 3D skeletal keypoints from video input in real time, enabling efficient analysis of joint trajectories, angles, and coordination. These tools have been successfully applied to detect gait abnormalities in a range of clinical populations, including those with neurological and metabolic disorders, and are now being adapted for obesity screening. Additionally, 3D voxel modeling techniques derived from multi-view images or depth data provide volumetric insights into body composition, posture, and load distribution—factors highly relevant to obesity diagnosis and monitoring.

The integration of AI-powered analysis with optical sensing offers several advantages:

Non-invasiveness: No physical contact or markers required, increasing user comfort and compliance.

Scalability: Portable and low-cost systems enable deployment in diverse settings, from clinics to homes and schools.

Automation: AI-driven pipelines facilitate rapid, objective assessment, reducing operator dependency and human error.

Personalization: Continuous monitoring allows for individualized feedback and early intervention.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. There are ongoing debates regarding the reliability and validity of markerless optical systems compared to gold-standard laboratory instrumentation. Most algorithms are trained on normative datasets with limited representation of obese or morphologically diverse individuals, raising concerns about generalizability and algorithmic bias. Technical issues such as occlusion, clothing variability, and limited ground-truth data further complicate validation and deployment.

1.4. Scope and Objectives of the Review

Given these developments, the present review aims to consolidate and critically evaluate current optical sensor-based approaches for obesity detection, with a focus on three key domains:

Optical gait analysis systems that derive spatiotemporal and kinematic metrics from video or depth data.

Vision-based pose estimation frameworks that infer body mechanics from 2D/3D skeletal reconstructions.

3D voxel modeling techniques that provide volumetric insights into posture and body shape relevant to obesity diagnosis.

This review is intended for a multidisciplinary audience, including researchers and developers in biomedical sensing, artificial intelligence, health technology, biomechanics, and clinical diagnostics. By synthesizing findings from recent literature, we aim to:

• Provide an accessible overview of state-of-the-art methodologies and comparative system performance.

• Discuss validation, accessibility, and ethical considerations in deploying these technologies.

• Highlight both the current potential and limitations of optical sensor-based systems.

• Identify opportunities for future research and clinical translation.

In conclusion, the integration of gait analysis, pose estimation, and voxel modeling through optical sensing technologies holds transformative promise for early, individualized, and scalable obesity diagnostics. This is particularly significant for children and adolescents, where early detection and intervention can have lifelong health benefits. By bridging advances in sensing technology and AI with clinical needs, the field is poised to make a substantial impact on global efforts to curb the obesity epidemic.

2. Review Methodology

This literature review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 guidelines. While this article is not a formal systematic review, we adhered to PRISMA principles to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility. The primary research question guiding this review was expanded to encompass multiple dimensions:

“What are the current optical sensor technologies and methodological approaches used for detecting and analyzing obesity through gait analysis, pose estimation, and human voxel modeling?”

Secondary questions include:

-

1.

How has the landscape of optical sensor technology for obesity detection evolved since 2000?

-

2.

What are the comparative advantages of different optical sensing modalities for obesity assessment?

-

3.

What methodological challenges exist in validating these technologies across diverse populations?

-

4.

How do optical sensor approaches compare with traditional obesity assessment methods?

We included studies published in English or French, prioritizing those with significant academic influence (e.g., citation frequency, high-impact venues) to ensure methodological robustness and relevance.

2.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

As shown in

Table 1, a comprehensive search was conducted using seven primary electronic databases to ensure wide coverage across medical, engineering, and computer science domains:

The search period covered January 2006 through April 2025, capturing both foundational works and recent technological advances. Additionally, we employed citation tracking (both forward and backward) to identify seminal papers that may have been missing in the database searches.

Example PubMed Search (English):

("obesity" OR "overweight") OR

("gait analysis" OR "stride" OR "walking pattern") AND

("optical sensor" OR "OptoGait" OR "pose estimation" OR "OpenPose" OR "MediaPipe" OR "Kinect" OR "voxel model") AND

("validation" OR "accuracy" OR "biomechanics" OR "machine learning")

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The eligibility criteria were refined and expanded from the original methodology to ensure precise inclusion of relevant studies.

Table 2 presents the detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Study Selection Process

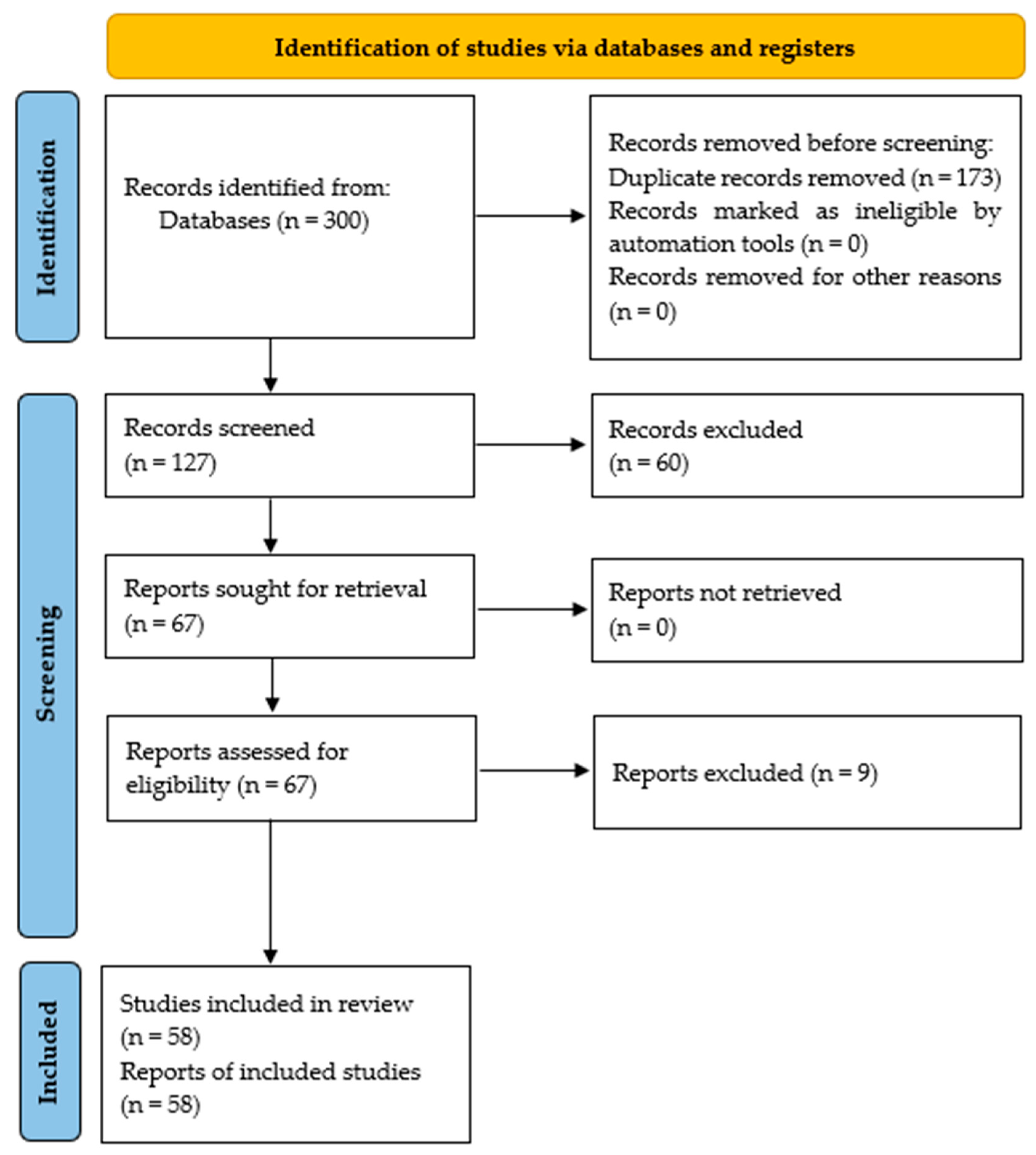

The study selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and is visually represented in

Figure 1, which captures the flow of information through different phases of the review. A total of

300 records were retrieved. After removing duplicates,

127 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these,

67 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. A final total of

58 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Selection of the relevant papers based on the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram.

Figure 1.

Selection of the relevant papers based on the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram.

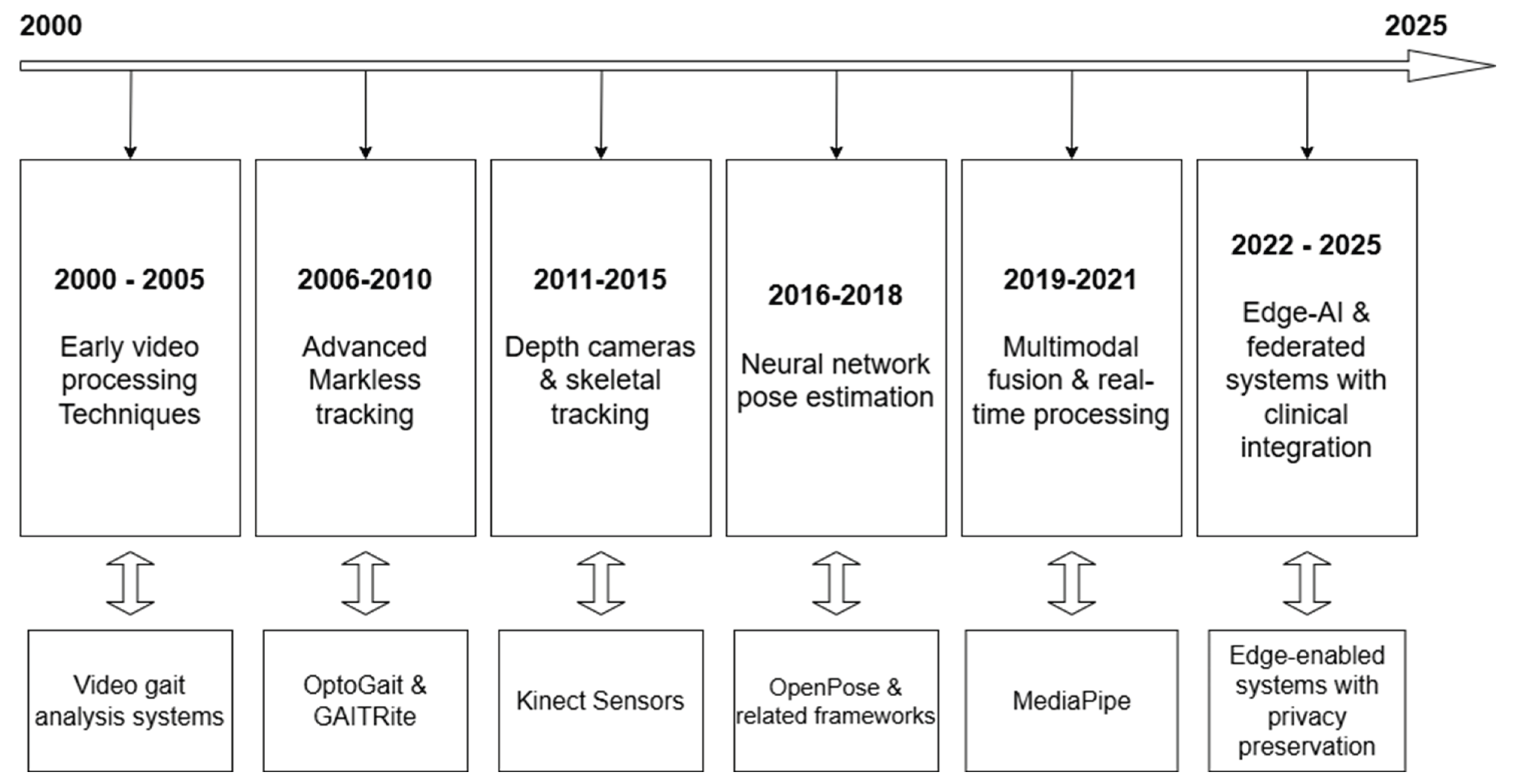

Figure 2.

Timeline of Key Developments in Optical Sensor Technologies for Obesity Detection.

Figure 2.

Timeline of Key Developments in Optical Sensor Technologies for Obesity Detection.

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

A methodical quality assessment process was implemented to evaluate the included studies. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the research spanning engineering, computer science, and clinical domains, we developed a custom quality assessment tool that incorporates elements from:

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools

The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2)

Additional technical criteria specific to optical sensing technologies

Table 3 outlines the quality assessment criteria used to evaluate included studies.

Total quality scores were categorized as follows:

We assessed each study, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. No studies were excluded based solely on quality assessment, but quality ratings were considered during data synthesis and interpretation.

2.5. Chronological Evolution Analysis

To capture the technological evolution in the field, we conducted a chronological analysis of optical sensing technologies for obesity detection from 2000 to 2025.

Figure 1 illustrates this evolution.

2.6. Review Structure

The literature review was organized using a hybrid approach that combines technological taxonomies with application domains, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the field. This structure allows for both technical depth and application relevance:

2.6.1. Primary Organization by Technology

Optical Gait Analysis Systems

Light barrier technologies (e.g., OptoGait)

Pressure-sensitive walkways (e.g., GAITRite)

Video-based markerless systems

Multi-camera setups

Vision-Based Pose Estimation Frameworks

• 2D pose estimation approaches (e.g., OpenPose, MediaPipe)

• 3D pose reconstruction methods

• Deep learning architectures (e.g., CNNs, transformers)

• Multi-person tracking systems

Depth-Sensor Based Voxel Modeling

• Structured light systems (e.g., first-generation Kinect)

• Time-of-flight sensors (e.g., Azure Kinect, RealSense)

• 3D body composition analysis

• Dynamic modeling approaches

Hybrid and Multimodal Systems

• Sensor fusion architectures

• Combined optical-inertial systems

• Multi-view integration approaches

• Ensemble methods

2.6.2. Secondary Organization by Application Focus

Within each technological category, studies were further organized according to their primary application focus:

Biomechanical and Kinematic Analysis

• Spatiotemporal gait parameters

• Joint angles and ranges of motion

• Center of mass trajectories

• Dynamic stability metrics

Anthropometric Measurement and Validation

• Body volume estimation

• Circumference measurements

• Body shape analysis

• Segmental proportions

Obesity Classification and Risk Assessment

Algorithm development and validation

Feature extraction methodologies

Classification performance metrics

Threshold determination

Implementation and Deployment Frameworks

• Clinical integration pathways

• Edge computing implementations

• Privacy-preserving architectures

• Real-world deployment considerations

This dual organizational structure enables the identification of both technological trends and application-specific challenges across the field of optical sensor-based obesity detection.

To summarize, his methodology ensures transparency and reproducibility of the literature review process. By adhering to PRISMA, we aim to strengthen the credibility of our findings and align with best practices required for publication in high-impact journals. Future research would benefit from the establishment of a shared repository of benchmark datasets for cross-validation and method comparison.

3. Optical Sensors Technologies for Gait Analysis in Obesity Detection

As obesity has become a global health concern, it is also associated with considerable motor impairments, particularly affecting gait and balance. Objective gait analysis techniques offer valuable tools for assessing these impairments and potentially identifying obesity-related gait alterations.

In this part, we examine the application of optical sensor-based systems, specifically image processing and floor sensor technologies, for gait analysis in individuals with obesity compared to normal-weight controls, drawing upon insights from the provided literature. We discuss the principles and hardware configurations of these systems, explore the gait biomarkers identified in the context of obesity, and analyze the technical advantages and limitations inherent in their application.

3.1. Sensor Technologies Overview / Optical Gait Sensing for Obesity Detection

Gait analysis traditionally relies on either semi-subjective observations or objective measurements using various sensor technologies [

7] [

8]. Objective methods leverage technological advancements to quantify gait parameters with greater accuracy, exactitude, repeatability, and reproducibility compared to subjective assessments [

7]. These objective techniques can be broadly categorized based on sensor placement: Non-Wearable Sensors (NWS) and Wearable Sensors (WS) [

7]. Optical sensor-based systems primarily fall under the NWS category, requiring controlled laboratory settings where subjects walk along defined walkways equipped with sensors [

7].

Optical sensor-based gait analysis relevant to obesity can be understood through the lens of floor sensor systems and image processing (video-based capture) technologies.

3.1.1. Floor Sensor Systems

Floor sensor systems are a type of NWS where sensors are integrated into the floor or a walkway [

7]. These systems measure gait by capturing data as the subject walks across them [

7]. Two primary types are mentioned:

Force Platforms: These systems utilize pressure or force sensors and moment transducers to measure the force vector applied during gait [

7]. They can measure the 3D Ground Reaction Force (GRF) and moments involved in locomotion [

8]. While highly accurate, they often require the subject to make contact with a specific area for correct measurement [

7].

Pressure Measurement Systems: Similar to force platforms, these systems quantify the center of pressure but do not directly measure the force vector [

7]. They use arrays of sensitive cells (capacitive/resistive) to record plantar pressure distribution over time, revealing foot loading patterns and Center of Pressure (CoP) progression [

8]. Examples include pressure sensor mats and platforms [

7].

Floor sensor systems provide objective data on force-related parameters and gait phases [

7]. They are considered gold standards for gait measurements, offering excellent quality data with high accuracy and repeatability, but are costly, bulky, and require a specialized workforce [

8].

3.1.2. Optical Timing Systems

While not explicitly detailed as a separate category distinct from other floor or image-based systems in the sources, the description of systems like OptoGait suggests a form of optical timing and measurement [

9].

OptoGait is described as a portable photoelectric cell system used for clinical assessment of static and dynamic foot pressures and quantifying spatio-temporal parameters. It works by measuring foot movements and space-temporal relationships using photoelectric cells

12. The system is noted for its reliability in clinical assessment [

9]. While technically leveraging photoelectric principles rather than image processing or traditional force/pressure plates, it functions similarly to some floor-based systems by assessing gait on a walkway and is often used to derive similar spatio-temporal parameters.

3.1.3. Video-Based Capture (Image Processing)

Image processing (IP) techniques utilize cameras to capture and analyze gait [

7]. These systems extract essential gait features from images [

7]. They range from single-camera systems to more complex multi-camera setups [

7,

8].

Marker-Based Systems: These optical motion capture systems track targeted joints and orientations using reflective markers placed on the body [

8]. They use multi-camera stereophotogrammetric video systems to compute the 3D localization of these markers, determining joint positions and body segment orientations [

8].

Markerless Systems: These systems use a human body model and image features to determine shape, pose, and joint orientations without the need for markers [

8]. Recent work utilizes computer vision techniques and deep neural networks to extract 2D skeletons from images for gait analysis, even exploring privacy-preserving methods by processing encrypted images [

10]. Examples include systems based on single cameras, Time of Flight sensors, Stereoscopic Vision, Structured Light, and IR Thermography [

7].

Image processing systems allow for individual recognition and segment position analysis [

7]. They offer advantages like relatively simple equipment setup for single cameras but can involve complex analysis algorithms and high computational costs for more advanced configurations [

7]. They require controlled laboratory environments [

8].

In summary, optical sensor-based systems for gait analysis in the context of obesity primarily involve floor-mounted force/pressure sensors and camera-based image processing systems. These NWS provide objective, quantitative data in a controlled setting, although they differ in the specific parameters they measure (forces vs. kinematics) and their technical complexity and cost [

7,

8]. The OptoGait system, a photoelectric cell-based system, also falls under this umbrella of fixed-location measurement systems used for gait assessment [

9].

3.2. Applications in Obesity Context: Identified Biomarkers

Obesity is clearly linked to motor impairments, including deficits in gait and balance [

11]. Individuals with obesity exhibit differences in movement and gait compared to those with normal weight, contributing to an increased risk of falls and stumbling [

11]. Gait analysis using objective methods, including optical sensor-based systems, is applied to quantify these differences and identify specific gait alterations or biomarkers associated with obesity [

5].

The goal is to capture gait and balance impairment in individuals with obese BMI and relate it to specific parameters [

11]. While one source mentions findings that did not show significant differences in cadence, gait speed, stride duration, daily step count, or double support time between normal and obese BMI categories, it also notes that these findings diverge from existing literature [

5]. Other sources and the research questions themselves highlight the expectation and investigation of such differences [

5,

11].

Typical gait parameters investigated in the context of obesity using objective systems include spatiotemporal parameters, kinematics, and kinetics [

5,

8,

11].

3.2.1. Spatiotemporal Parameters

These include metrics like gait speed, step length, stride length, cadence, step width, step angle, step time, swing time, stance time, and double support time [

5,

7]. Studies aim to investigate variances in these parameters between obese and normal weight groups. Koinis et al. suggests that increasing BMI is associated with decreased gait speed and that obesity significantly increases the likelihood of falls [

5]. Koinis et al. notes that people with obesity may experience up to a 15% reduction in gait speed and a 25% decrease in step length compared to those with normal BMI, although their own study did not find significant differences in some parameters[

5]. Spatiotemporal parameters, especially walking speed and step length, are considered clinically important indicators [

7].

3.2.2. Kinematics

This describes the movement of joints and body segments, including range of motion and segment acceleration [

8,

12]. While less explicitly detailed in relation to optical image systems and obesity in the provided excerpts compared to spatiotemporal parameters, biomechanical studies of obesity-related gait do investigate joint mechanics [

5,

7,

11,

13]. Image processing systems (marker-based and markerless) are capable of measuring joint angles and segment position/orientation [

7,

8].

3.2.3. Kinetics

This focuses on the forces and moments that cause movement, such as Ground Reaction Forces (GRF), muscle force, and joint momentum [

8,

12]. Floor sensor systems, particularly force platforms, are designed to measure GRF [

7,

8]. These kinetic parameters provide insight into the biomechanical effects of increased body mass on the musculoskeletal system during gait[

5,

7,

13].

In addition to these quantitative parameters, gait analysis can also reveal qualitative aspects and patterns, such as gait symmetry and postural balance [

7,

8,

13]. While specific findings on gait asymmetry directly measured by optical sensors in obese individuals aren't detailed across the sources, a study on overweight and obese children mentions assessing pelvic symmetry indices using a wearable system (BTS G-WALK, which uses inertial sensors) [

13]. Postural balance is a key problem associated with conditions affecting gait, including obesity [

7,

8,

11]. Gait and balance analysis are crucial for understanding locomotor and functional impairments [

8].

Therefore, optical sensor-based systems, particularly floor sensors and camera-based systems, are used to objectively measure spatiotemporal, kinematic, and kinetic parameters that serve as biomarkers of obesity-related gait impairments, including potential changes in speed, step/stride length, timing, forces, joint movements, and overall gait pattern and stability [

5,

7,

8,

11].

3.3. Technical Advantages and Limitations

Objective gait analysis systems, including those based on optical sensors, offer significant advantages over traditional semi-subjective methods by providing accurate and quantitative data [

7]. However, they also present technical limitations, particularly when considering their application in diverse settings and populations, such as individuals with obesity.

3.3.1. Precision vs. Portability Trade-Offs

Optical sensor-based NWS systems, operated in controlled laboratory environments, are considered gold standards for gait measurement due to their high accuracy and repeatability [

8]. For instance, GRF plates offer high accuracy with minimal load error, and pressure sensor mats can achieve high recognition rates [

1]. These systems provide precise data on a wide range of parameters simultaneously [

2]. However, their precision comes at the cost of portability. NWS systems are bulky, require specialized facilities, and are not suitable for monitoring gait during everyday activities outside the laboratory [

7,

8]. In contrast, wearable sensor (WS) systems offer portability and the ability to monitor gait in real-world settings over long periods, but often have reduced accuracy and reliability compared to NWS [

7,

8]. While WS are not the focus of this review section on optical sensors, this contrast highlights the inherent trade-off: high precision is typically found in non-portable, controlled NWS (like optical systems), while portability is the domain of WS with variable accuracy [

8,

14].

3.3.2. Environmental Dependencies, Calibration Needs, and Other Factors

Optical sensor-based systems can be sensitive to environmental factors and require careful setup and calibration.

Controlled Environment: NWS, including image processing and floor sensors, require controlled research facilities. Subjects must walk on a clearly marked walkway [

7].

Calibration: Both image processing and floor sensor systems require calibration. For instance, stereoscopic vision systems involve complex calibration, and structured light systems also require calibration [

7]. While the sources don't detail the specific calibration requirements for obese subjects, increased body size or altered gait patterns could potentially influence calibration procedures or accuracy.

Surface Sensitivity and Footwear Interference: Floor sensor systems are directly affected by the interaction between the foot and the sensing surface [

7,

8]. The type of footwear worn can influence pressure distribution and force measurements, potentially acting as an interference or requiring standardized footwear [

2].

Subject-Specific Variance: While not unique to optical systems, individual variations in gait patterns are inherent. In the context of obesity, larger body mass significantly affects biomechanics and gait patterns [

5,

7,

13]. Accurately capturing these subject-specific variations requires robust measurement techniques. Image processing systems that track body segments or skeletons may need to account for differences in body shape and soft tissue movement in obese individuals [

10].

3.3.3. Limitations Specific to System Types:

Floor Sensors

Force platforms require the subject to contact the center of the plate for correct measurement. Pressure sensor mats and platforms have limitations of space, indoor measurement, and depend on the patient's ability to make contact with the platform.

Image Processing

Single camera systems have simple equipment but require complex analysis algorithms. Stereoscopic vision has complex calibration and high computational cost. Time of flight systems can have problems with reflective surfaces. IR Thermography requires considering emissivity, absorptivity, reflectivity, and transmissivity of materials. Extracting parameters like step length from image-based systems can sometimes be more accurate than methods used in some WS systems.

In summary, optical sensor-based gait analysis systems, as NWS technologies, offer high precision and the ability to capture detailed kinematic and kinetic data in a controlled environment [

7,

8]. However, they are non-portable, require specialized facilities and expertise, and can be sensitive to environmental factors, calibration specifics, and the interaction between the subject's foot/body and the sensing system [

7,

8,

15]. Applying these systems to study gait in individuals with obesity necessitates careful consideration of how increased body mass and potential gait alterations might influence data acquisition and interpretation [

5,

7,

13].

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis for Optical Sensor-Based Gait Analysis Systems (Based on Provided Sources).

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis for Optical Sensor-Based Gait Analysis Systems (Based on Provided Sources).

| Feature / System Type |

Principles & Hardware Setup |

Applications (Obesity Context) |

Technical Advantages |

Technical Limitations |

| Floor Sensors: Force Platforms |

Messasure 3D force vector, pressure, moment using sensors/transducers in floor. |

Measure GRF, potentially revealing kinetic adaptations to increased body mass in obesity. Assess gait phases. |

High accuracy (e.g., ±0.1% load error). Objective, quantitative data. Gold standard [8]. |

Requires controlled lab.

Requires subject to contact center of plate. Bulky, costly, requires expertise [7,8,15].

Non-portable. Footwear can interfere. |

| Floor Sensors: Pressure Systems |

Measure plantar pressure distribution and CoP using sensor arrays in floor mats/platforms. |

Assess foot loading patterns and weight distribution during gait in obese individuals. Assess gait phases, step detection. |

Measures plantar pressure patterns. Can have high recognition rates (80%) [7]. Easy setup in insoles (WS variant, but principle similar to NWS). |

Limitations of space, indoor measurement. Patient must make contact with platform. Highly nonlinear response for insole type. Non-portable (mats/platforms). Surface/footwear sensitive. |

| Optical Timing (e.g., OptoGait) |

Uses photoelectric cells along a walkway to measure foot movements and spatio-temporal timing. |

Quantify spatio-temporal parameters (speed, timing, lengths) which are altered in obesity[5]. Reliable for clinical assessment [9]. |

Portable compared to larger NWS. Reliable for spatio-temporal measures [9]. |

Limited to spatio-temporal parameters [9].

Requires specific walkway setup. Can be sensitive to ambient light/interference (inferred from photoelectric principle). |

| Video-Based Capture: Marker-Based |

Uses multi-camera stereophotogrammetry to track reflective markers on body segments. |

Measure 3D kinematics (joint angles, segment position/orientation), revealing changes in movement patterns due to obesity's biomechanical effects [5,7,13]. Assess gait phases. |

High accuracy for kinematic measures [14]. Detailed 3D motion data. |

Requires controlled lab with multiple cameras. Complex setup and calibration. Markers can be displaced by soft tissue or movement. Costly, requires expertise [8,15]. Non-portable. |

| Video-Based Capture: Markerless |

Uses human body models and image features (e.g., 2D skeletons) from cameras (single, ToF, stereo, structured light, IRT). |

Measure kinematics (segment position, joint angles), assess gait phases, potentially gait recognition or abnormal pattern detection.

Useful for studying biomechanical changes in obesity. |

Non-invasive. Can potentially work with less equipment (single camera). Progress in privacy preservation [10]. |

Accuracy can vary (moderate-poor for spatio-temporal in some WS applications, but NWS generally better [14]). Complex analysis algorithms (single camera). Complex calibration/high computational cost (stereo vision). Issues with reflective surfaces (ToF). Requires specific environmental conditions (IRT). Non-portable (NWS setups) . [16] |

In this section, we highlighted the critical role of objective gait analysis in understanding and quantifying the motor impairments associated with obesity. Optical sensor-based systems, including floor sensor technologies (force platforms, pressure systems) and video-based capture (marker-based and markerless image processing), represent key non-wearable sensor (NWS) approaches used in this field [

7,

8]. These systems are capable of measuring important gait biomarkers such as spatiotemporal parameters, kinematics, and kinetics, which are known to be altered by increased body mass and contribute to mobility issues and fall risk in individuals with obesity [

5,

7].

While NWS optical systems offer high accuracy and the ability to collect comprehensive data in controlled settings, they are limited by their lack of portability, high cost, need for specialized expertise, and susceptibility to environmental and subject-specific factors [

7,

8,

15]. Despite these limitations, they remain valuable tools for detailed clinical and research assessments of gait mechanics in obesity.

Future advancements, particularly in areas like miniaturization, power efficiency, and sophisticated algorithms, are focused on improving wearable technologies to potentially bridge the gap in measurement capacity and accuracy with NWS, enabling long-term, real-world gait monitoring. However, for detailed, high-precision laboratory-based analysis, optical sensor systems continue to play a significant role in uncovering the complex interplay between obesity and gait dynamics. Further research utilizing these objective techniques is essential for refining our understanding of obesity-related gait abnormalities and developing targeted interventions.

4. Markerless Video-Based Pose Estimation Technologies

Markerless pose estimation represents a revolutionary approach to human motion analysis, enabling the extraction of kinematic data without the need for physical markers attached to subjects. This technology has seen rapid advancement in recent years, primarily driven by developments in computer vision and deep learning. Unlike traditional marker-based motion capture systems that require specialized hardware and controlled laboratory environments, markerless systems operate with standard cameras in diverse settings, making them accessible for widespread applications in healthcare, sports science, biomechanics research, and human-computer interaction. This part of the review examines current markerless video-based pose estimation technologies, focusing on algorithms, validation, challenges related to body morphology diversity, and advancements in hybrid sensing approaches.

4.1. Key Algorithms and Platforms

4.1.1. OpenPose

OpenPose represents one of the pioneering deep learning-based frameworks for real-time multi-person human pose detection. Developed at Carnegie Mellon University, it revolutionized the field by enabling the simultaneous detection of multiple individuals within a single image or video frame. OpenPose employs a bottom-up approach that first detects body parts across the entire image and then associates them to form complete human skeletons.

The architecture of OpenPose is built upon a multi-stage convolutional neural network (CNN) that processes images through two main branches: one for body part detection and another for part association. This two-branch approach enables the system to maintain high accuracy even when multiple people appear in the scene with overlapping body parts. The network generates confidence maps for each body part location and part affinity fields (PAFs) that encode the degree of association between parts, allowing the system to determine which body parts belong to the same person.

OpenPose can jointly detect human body, foot, hand, and facial keypoints, providing a comprehensive representation of human pose. The standard model identifies 25 body keypoints, including major joints like shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles, as well as facial landmarks. Extended models incorporate additional keypoints for hands and detailed facial features, resulting in a total of 135 keypoints per person when using the full model.

The versatility of OpenPose has led to its application across diverse domains. In biomechanics research, it has enabled the analysis of sports performance without interfering with athletes' natural movements. In 2020, Nakano et al. developed a 3D markerless motion capture technique using OpenPose with multiple synchronized cameras to evaluate motor performance tasks including walking, jumping, and ball throwing [

17]. They found that approximately 47% of measurements had mean absolute errors below 20mm compared to marker-based systems, with 80% below 30mm [

17].

4.1.2. MediaPipe

MediaPipe Pose is another significant deep learning-based framework for human pose estimation, developed by Google. Unlike OpenPose's bottom-up approach, MediaPipe typically employs a top-down methodology that first detects persons in the image and then estimates the pose for each detected individual. This approach generally works well when the number of people in the scene is limited, making it particularly suitable for applications focusing on a single subject or a few individuals.

MediaPipe Pose Estimation is based on the BlazePose architecture, which was specifically designed for real-time performance on mobile devices [

18]. The system provides 33 3D keypoints in real-time, representing a superset of the 17 keypoints from the COCO dataset (commonly used in many pose estimation systems). These additional points provide more detailed tracking of the face, hands, and feet, enhancing the granularity of pose information [

18]. The pipeline of MediaPipe Pose first detects a person in the image using a face detector and then predicts the keypoints, assuming that the face is always visible [

18].

A distinctive feature of MediaPipe is its optimized performance for mobile deployment. On devices like the Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra with the Snapdragon 8 Gen 2 chipset, the inference time can be as low as 0.826 ms, with a peak memory range of 0-1 MB [

19]. This exceptional efficiency makes MediaPipe an excellent choice for real-time applications on edge devices where computational resources are limited.

MediaPipe Pose is primarily designed for fitness applications involving a single person or a few people in the scene [

18]. Its applications include yoga pose correction, fitness tracking, physical therapy, and gesture-based interfaces. The framework is easily accessible through Python packages and can be configured to run on cloud-hosted devices using platforms like the Qualcomm AI Hub [

19].

4.1.3. DeepLabCut

DeepLabCut represents a different approach to pose estimation, originally developed for markerless tracking of animals in research settings. Created by Mathis et al., DeepLabCut leverages transfer learning to achieve high-performance pose estimation with relatively small training datasets, making it particularly valuable for specialized applications where large annotated datasets may not be available [

20].

The architecture of DeepLabCut was initially inspired by DeeperCut, a state-of-the-art algorithm for human pose estimation by Insafutdinov et al. [

21], which inspired the name for the toolbox. However, since its inception, DeepLabCut has evolved substantially, incorporating various backbone networks including ResNets, MobileNetV2, EfficientNets, and the custom DLCRNet backbones. This flexibility in network architecture allows users to balance accuracy and computational efficiency based on their specific requirements.

A key strength of DeepLabCut is its ability to achieve high accuracy with limited training data, typically requiring only a few hundred labeled frames to generate reliable pose estimates for novel videos [

20]. This is achieved through transfer learning, where pre-trained networks (typically trained on ImageNet) are fine-tuned for specific pose estimation tasks. The developers have demonstrated that this approach works effectively across species including mice, flies, humans, fish, and horses.

In addition to its 2D pose estimation capabilities, DeepLabCut also supports 3D pose reconstruction using multiple cameras or even from a single camera with appropriate training data [

22]. The framework has been extended to support real-time processing through DLClive, enabling applications that require immediate feedback based on pose information [

22].

While DeepLabCut was originally developed for animal tracking, its principles and approaches have been successfully applied to human subjects as well [

23]. The framework is particularly valuable in research contexts where custom keypoint definitions may be needed, or where the specifics of the application differ from the standard human pose estimation use cases [

24].

4.2. Validation and Accuracy

4.2.1. Comparison with Gold Standard Systems

The validation of markerless pose estimation systems against gold standard marker-based motion capture is essential for establishing their reliability in scientific and clinical applications. Optical marker-based systems, such as Vicon or OptiTrack, remain the reference standard in biomechanics research due to their sub-millimeter accuracy in controlled environments.

A comprehensive evaluation of OpenPose-based markerless motion capture was conducted by Nakano et al., comparing it with optical marker-based systems during various motor tasks including walking, countermovement jumping, and ball throwing [

17]. The study employed multiple synchronized cameras to reconstruct 3D poses from OpenPose's 2D estimates and compared the resulting joint positions with those measured by a marker-based system. The differences were quantified using mean absolute error (MAE) between corresponding joint positions [

17].

The results revealed that approximately 47% of all calculated mean absolute errors were below 20 mm, and 80% were below 30 mm, indicating reasonable accuracy for many applications [

17]. However, approximately 10% of errors exceeded 40 mm, primarily due to failures in OpenPose's 2D tracking, such as incorrectly recognizing objects as body segments or confusing one body segment with another [

17]. These findings suggest that while markerless systems can approach the accuracy of marker-based systems for many applications, they still face challenges in robustly tracking all body segments across diverse movements and viewing conditions [

25]

The accuracy of markerless systems varies considerably across different joints and movement types. Generally, larger and more visible joints such as the shoulders, hips, and knees tend to be tracked more reliably than smaller joints like the wrists, ankles, and fingers. Additionally, movements that involve rapid motion, occlusion, or unusual poses can challenge the performance of current algorithms, leading to increased error rates [

26].

It's important to note that while absolute position accuracy may still lag behind marker-based systems, many applications primarily require accurate relative motion patterns or joint angles, which markerless systems can often provide with sufficient reliability. This makes them viable alternatives for applications where the convenience of markerless tracking outweighs the need for the highest possible accuracy.

4.2.2. Comparison with IMU Systems

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) represent another approach to motion capture that relies on wearable sensors containing accelerometers, gyroscopes, and sometimes magnetometers to track segment orientations. While not entirely "markerless" in the strictest sense (as they require sensors to be attached to the body), IMUs offer an alternative to optical systems that have gained popularity for field-based measurements.

Recent research has compared both IMU and markerless video-based methods against optoelectronic systems. A pilot validation study examined these approaches during simulated surgery tasks, where traditional marker-based systems would be impractical [

27]. The findings indicated that the IMU method demonstrated root mean square errors (RMSE) of 2.1 to 7.5 degrees with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.53 to 0.99, while the markerless method showed higher errors of 5.5 to 8.7 degrees RMSE with ICCs between 0.31 and 0.70 [

27]. Based on these results, the researchers recommended the IMU method over the markerless approach for the specific context of measuring neck and trunk movements during surgery [

27].

However, it's important to consider the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach. IMUs excel at capturing segment orientations and can operate without line-of-sight constraints, making them suitable for complex environments with occlusions. However, they struggle with position drift over time and require careful calibration. Markerless video systems, in contrast, can provide absolute position information without drift but require continuous visibility of body segments to the cameras.

The complementary nature of these technologies has led to increasing interest in hybrid systems that combine IMUs with video-based tracking to leverage the strengths of each approach. Such systems can use visual information to correct IMU drift while using IMU data to fill gaps during visual occlusions.

4.2.3. Body Morphology Effects on Detection

The impact of body morphology, particularly body mass index (BMI), on the accuracy of markerless pose estimation represents a significant challenge for these technologies. High BMI can affect pose estimation accuracy through several mechanisms. First, increased adipose tissue can change the visual appearance of joints, making their precise localization more difficult. Second, in individuals with higher BMI, certain joints may be partially occluded by soft tissue, reducing their visibility to the camera. Third, the standard body proportions assumed by many pose estimation algorithms may not accurately represent individuals with higher BMI, potentially leading to systematic errors in keypoint placement.

Limited research has directly quantified these effects, but clinical experience and preliminary studies suggest that pose estimation accuracy generally decreases as BMI increases, particularly for joints of the lower extremities. This creates a significant challenge for applications in healthcare settings, where individuals with higher BMI may be precisely those who would benefit most from motion analysis for conditions like osteoarthritis, diabetic gait disorders, or rehabilitation monitoring.

To address these challenges, several approaches have been proposed. One approach involves creating more diverse training datasets that include individuals across the full spectrum of body sizes and shapes. Another approach uses adaptive algorithms that can adjust their keypoint detection strategies based on the detected body morphology. Some researchers have also explored the use of additional sensors, such as depth cameras, to provide supplementary information that can improve joint localization in challenging cases.

The ability to accurately track movements across diverse body morphologies remains an important frontier for markerless pose estimation research, with implications for the equity and inclusivity of these technologies in healthcare and other domains.

4.3. Obesity-Related Gait Signatures

4.3.1. Technical Challenges

Markerless pose estimation faces several technical challenges when applied to individuals with obesity, particularly in the context of gait analysis. The first major challenge is joint occlusion, which occurs when adipose tissue or limb positioning prevents clear visual access to joint centers. This is especially problematic for the hip joints, which may be obscured by abdominal or thigh tissue, and for the knees, which can be partially hidden during certain phases of the gait cycle.

Over-segmentation represents another challenge, where the algorithm incorrectly identifies multiple keypoints where only one should exist. This can occur when the visual appearance of body segments in high-BMI individuals differs significantly from the training data used to develop the pose estimation model. For example, the algorithm might mistakenly identify multiple knee joints due to the different contour of the leg in individuals with higher BMI.

Signal processing adaptations have been developed to address these challenges. These include temporal filtering approaches that maintain continuity of joint trajectories based on biomechanical constraints, preventing physically impossible jumps in joint positions between frames. Some systems also incorporate anatomical constraints and body-specific calibration procedures to adapt their models to individual body morphologies.

Multi-view approaches can significantly mitigate occlusion issues by providing alternative angles from which to observe partially hidden joints. When a joint is occluded from one camera's perspective, it may be visible from another, allowing the system to maintain tracking. Advanced systems can dynamically weight the confidence of detections from different cameras based on their viewing angle relative to each body segment.

Addressing these technical challenges is essential for developing inclusive motion analysis technologies that can serve diverse populations. The most promising approaches combine algorithmic improvements with hardware solutions like strategic camera placement to maximize visibility of key anatomical landmarks.

4.3.2. Biomechanical Alterations

Obesity is associated with several characteristic alterations in gait biomechanics that pose estimation systems must accurately capture to provide clinically relevant information. Understanding these patterns is essential both for developing more robust tracking algorithms and for interpreting the resulting kinematic data in clinical contexts.

Altered joint angle trajectories represent one of the most significant gait modifications in individuals with obesity. Typically, these include reduced knee flexion during swing phase, decreased hip extension during late stance, and modified ankle kinematics throughout the gait cycle. These alterations are believed to result from a combination of increased joint loading, altered muscle function, and adaptations to maintain stability with changed body mass distribution.

Increased trunk lean is another common characteristic of gait in individuals with higher BMI. This forward inclination of the trunk shifts the center of mass anteriorly, potentially reducing the muscular effort required to initiate forward progression during walking. Accurately quantifying trunk lean is important for assessing energy expenditure during gait and for understanding compensatory mechanisms that may increase risk for back pain or other musculoskeletal issues.

Lateral sway patterns also differ in individuals with obesity, with typically increased mediolateral center of mass displacement during walking. This increased lateral movement requires additional stabilizing mechanisms and may contribute to higher energy costs of walking. Capturing these subtle movements requires pose estimation systems with high accuracy in tracking the relative positions of the pelvis, lower extremities, and trunk.

Markerless systems must be capable of accurately measuring these biomechanical alterations to provide clinically meaningful assessments. Validation studies specifically examining the accuracy of these systems in capturing obesity-related gait signatures are limited but represent an important area for future research.

4.3.3. Clinical Applications

Despite the challenges, markerless pose estimation offers significant potential for clinical applications related to obesity and associated movement disorders. The non-invasive nature of these systems makes them particularly valuable for longitudinal monitoring, where repeated assessments are needed to track changes over time.

In weight management programs, objective quantification of gait parameters can provide valuable feedback on the functional improvements resulting from weight loss. Parameters such as step length, walking speed, joint ranges of motion, and stability measures can demonstrate functional gains that may motivate continued adherence to intervention programs. Markerless systems enable these measurements to be taken in clinical settings without the time-consuming application of markers or specialized equipment.

For surgical interventions such as bariatric surgery or joint replacements, markerless motion analysis can help document functional outcomes and guide rehabilitation strategies. The ability to conduct these assessments quickly and easily facilitates their integration into routine clinical care, rather than being limited to specialized research settings.

Telehealth applications represent another promising domain, where markerless systems using standard webcams could enable remote assessment of movement function. This could be particularly valuable for monitoring patients in rural or underserved areas where access to specialized gait laboratories is limited.

As these technologies continue to improve in accuracy and robustness across diverse body morphologies, their integration into standard clinical care pathways for obesity and related conditions becomes increasingly feasible, potentially transforming the assessment and management of movement-related complications.

4.4. Depth and Hybrid Systems

4.4.1. RGB-D Framework

RGB-D systems combine traditional color images (RGB) with depth information (D), creating a more comprehensive representation of the 3D scene. While standard RGB cameras capture only the visual appearance of subjects, depth sensors provide direct measurements of the distance between the sensor and each point in the scene. This additional dimension of information can significantly enhance the accuracy and robustness of pose estimation, particularly in challenging scenarios involving occlusions or unusual body positions.

The Microsoft Kinect V2 represents one of the most widely used RGB-D platforms for human motion capture. It combines a standard RGB camera with an infrared time-of-flight depth sensor that provides pixel-wise distance measurements. The integration of depth data allows the system to disambiguate between overlapping body parts and more accurately localize joints in 3D space, even when their appearance in the RGB image alone might be ambiguous.

The processing pipeline for RGB-D pose estimation typically involves several stages. First, the depth information is used to segment the human figure from the background. Next, the segmented depth map is processed to identify body parts using techniques such as random decision forests or deep learning. Finally, a skeletal model is fitted to these detected body parts, taking into account both the RGB appearance and the 3D structure provided by the depth data.

More recent approaches have incorporated deep learning methods that can jointly process RGB and depth information. These networks are trained to leverage complementary cues from both modalities: appearance features from RGB images and structural information from depth maps. This fusion of information sources has proven particularly effective for robust pose estimation in complex real-world environments.

4.4.2. Accuracy Improvements

The incorporation of depth information provides several significant accuracy improvements for pose estimation, especially in challenging scenarios. First, depth data helps resolve ambiguities in the RGB image by providing direct 3D information about the spatial arrangement of body parts. This is particularly valuable when body parts overlap from the camera's perspective, which can confuse RGB-only systems.

Second, depth sensors are generally less sensitive to lighting variations than RGB cameras, making them more robust for applications in environments with inconsistent or poor lighting. While strong infrared interference can affect depth sensors, they generally provide more stable measurements across varying ambient light conditions than color-based approaches alone.

Third, depth information facilitates more accurate background segmentation, helping to isolate the human figure from complex environments. This is especially valuable in cluttered scenes where color-based segmentation might struggle to distinguish between the subject and visually similar background elements.

Quantitative studies have demonstrated these advantages, with RGB-D systems typically showing reduced average joint position errors compared to RGB-only approaches when evaluated against marker-based ground truth. The magnitude of improvement varies by joint, with the greatest benefits often seen for joints that are frequently occluded or that lack distinctive color features.

However, it's important to note that depth sensors have their own limitations, including more restricted range, higher power consumption, and typically lower resolution than RGB cameras. These considerations are particularly relevant for mobile or wearable applications where power and computational resources may be constrained.

4.4.3. Real-World Applications

RGB-D systems have found applications across numerous domains where robust pose estimation in uncontrolled environments is required. In clinical settings, these systems enable functional movement assessment without the need for markers, facilitating the integration of motion analysis into routine care. Applications include gait assessment, balance evaluation, and rehabilitation monitoring, where the system can provide immediate feedback on movement quality and progress.

Home monitoring represents another growing application area, where RGB-D sensors can track movements over extended periods in naturalistic environments. This enables longer-term assessment of mobility patterns and functional status, which may be more representative of real-world capabilities than brief assessments in clinical settings. Privacy concerns in home monitoring can be mitigated by processing data locally and extracting only anonymous skeletal data rather than storing raw RGB images.

Public space analysis for ergonomics, safety, and accessibility represents a third application domain. Here, RGB-D systems can analyze how diverse individuals interact with built environments without requiring individual consent for marker placement. This supports the development of more inclusive design standards that accommodate the full range of human body sizes and movement capabilities.

The continued miniaturization and cost reduction of depth sensing technologies promises to further expand these applications. Emerging systems incorporate depth sensing directly into mobile devices or wearable cameras, enabling pose estimation in increasingly diverse and dynamic environments while maintaining user privacy through on-device processing of sensitive data.

Markerless video-based pose estimation technologies have advanced rapidly in recent years, driven by breakthroughs in deep learning and computer vision. Systems like OpenPose, MediaPipe, and DeepLabCut provide accessible frameworks for human motion analysis across diverse applications, from clinical assessment to sports performance and human-computer interaction.

Validation studies against gold standard marker-based systems indicate that markerless approaches can achieve reasonable accuracy for many applications, with the majority of joint position errors falling below 30mm in controlled conditions. However, challenges remain in tracking rapid movements, handling occlusions, and accurately capturing the movements of individuals whose body morphologies differ significantly from those represented in training datasets.

The impact of body morphology, particularly higher BMI, on pose estimation accuracy remains an important consideration for clinical applications. Technical challenges including joint occlusion and over-segmentation can affect the reliable tracking of obesity-related gait signatures such as altered joint trajectories, increased trunk lean, and modified lateral sway patterns. Addressing these challenges requires both algorithmic improvements and hardware solutions.

The integration of depth sensing with RGB cameras in hybrid systems offers promising improvements in robustness and accuracy, particularly in complex real-world environments. These RGB-D systems provide complementary information that enhances joint localization, improves robustness to lighting variations, and facilitates better segmentation of human figures from cluttered backgrounds.

Looking forward, the continued development of markerless pose estimation technologies promises to democratize access to human movement analysis, enabling applications that were previously confined to specialized laboratories to be deployed in clinical settings, homes, and public spaces. This expanded access has the potential to transform our understanding of human movement across diverse populations and environments, ultimately contributing to improved healthcare, enhanced performance, and more inclusive design of physical spaces and interfaces.

5. 3D Human Voxel Modeling and Anthropometric Estimation

The increasing availability of consumer-grade depth sensors has sparked significant research interest in 3D human body modeling and measurement extraction. This field intersects computer vision, machine learning, and anthropometry to develop methods for accurate body shape reconstruction and measurement estimation. This part of thr review examines the current state of research in voxel-based human body modeling with a focus on anthropometric applications.

5.1. Sensor-Based 3D Body Reconstruction

5.1.1. Depth Sensing Technologies

The evolution of consumer-grade depth cameras has revolutionized 3D human body reconstruction techniques. Time-of-Flight (ToF) cameras like the Microsoft Kinect V2 measure depth by calculating the time taken for infrared light pulses to travel to an object and back. In contrast, stereoscopic cameras such as the Intel RealSense D435 derive depth information from parallax between two camera viewpoints. A comparative study by Chuang-Yuan et al. revealed that ToF cameras generally provide more accurate 3D point clouds for human body modeling than stereoscopic sensors, with the Kinect V2 outperforming the RealSense D435 in KinectFusion reconstruction quality [

28].

Microsoft Kinect has been widely adopted for 3D body scanning applications due to its accessibility and reasonable accuracy. Weiss et al. demonstrated that the Kinect can produce 3D body models with measurement accuracy competitive with commercial body scanning systems costing orders of magnitude more [

29]. Their approach combined low-resolution image silhouettes with coarse range data to estimate a parametric model of the body, achieving accurate results by combining multiple monocular views of a person moving in front of the sensor.

5.1.2. Voxel-Based Representation and Processing

Voxel-based representations serve as a fundamental approach to 3D body reconstruction from depth data. Voxels (volumetric pixels) discretize 3D space into regular grid cells, each containing occupancy information. Li et al. introduced a coarse-to-fine reconstruction method combining voxel super-resolution (VSR) with learned implicit representation [

30]. Their approach first estimates coarse 3D models using a Pixel-aligned Implicit Function based on Multi-scale Features (MF-PIFu) extracted from multi-view images. The coarse model is then refined by implementing VSR through a multi-stage 3D convolutional neural network, which significantly enhances surface quality and geometric accuracy.

The resolution of voxel representations presents a critical trade-off between detail and computational efficiency. Research by Chuang-Yuan et al. demonstrated that increasing Kinect Fusion resolution from 128 to 512 voxels per meter yielded diminishing returns beyond 256 voxels per meter when scanning human subjects [

28]. This finding suggests an optimal voxel resolution for body scanning applications that balances detail capture and processing requirements.

5.1.3. Single-View Versus Multi-View Reconstruction

While multi-view approaches traditionally yield superior reconstruction quality, recent advances have improved single-view reconstruction methods. Single-view reconstruction is particularly relevant for practical applications where multiple cameras or viewpoints are unavailable. The Pixel2Pose approach demonstrated by researchers employs neural networks trained on high-resolution depth and intensity images from Microsoft Kinect to recover poses of multiple people in three dimensions from single-view time-of-flight data [

31]. Despite the apparent low spatial resolution of single-view captures, their system transforms the sensor's rich ToF data into accurate 3D pose information after supervised training.

For enhanced accuracy, multi-view approaches remain superior. As demonstrated by Li et al., combining multiple viewpoints allows for the creation of complete 3D models with fewer occlusions and better surface quality [

30]. Their method uses implicit representations, which enable memory-efficient training and produce high-resolution continuous decision boundaries, addressing the challenge of limited resolution in voxel grids.

5.1.4. Parametric Body Models

Statistical parametric body models have emerged as powerful tools for robust 3D reconstruction from noisy and incomplete sensor data. The SCAPE (Shape Completion and Animation for PEople) model, as utilized by Weiss et al., factors 3D body shape variations from pose variations [

29]. This approach enables the estimation of a single consistent body shape while allowing pose to vary, making it ideal for reconstructing consistent 3D human models from multiple partial views.

Parametric models provide a structured way to represent human body variation across a population and facilitate regression from sparse measurements to complete body shape. This capability is particularly valuable for anthropometric applications, as demonstrated by Tsoli et al., who used these models to predict body measurements with greater accuracy than state-of-the-art methods [

32].

5.2. Applications in Body Composition Analysis

5.2.1. Anthropometric Measurement Extraction

3D voxel representations of the human body enable automated extraction of anthropometric measurements traditionally performed by human anthropometrists. Tsoli et al. developed a model-based anthropometry approach that fits a deformable 3D body model to scan data and then extracts features including limb lengths, circumferences, and statistical features of global shape [

32]. Their method demonstrated superior accuracy compared to traditional landmark-based approaches, particularly when integrating information from multiple scans of a person in different poses.

The extraction of perimeter values from 3D scans has proven particularly valuable for body composition assessment. Alexa's research at Philips showed that models based on perimeter values around thigh, waist, arm, and neck could accurately predict body fat percentage, achieving an RMSE of 2.22% when compared to reference methods in pregnant women [

33]. This approach demonstrates how geometric features from 3D body scans can translate into clinically relevant body composition metrics.

5.2.2. Waist-to-Hip Ratio and Volumetric Indices

The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) represents a powerful predictor of health risks associated with fat distribution. LeanScreen technology has demonstrated the capability to calculate WHR quickly using 2D photographic methods combined with 3D body modeling techniques [

34]. This approach exemplifies how even partial 3D reconstruction can yield clinically relevant anthropometric indices.

Volumetric metrics derived from voxel-based 3D body models provide comprehensive assessments of body composition. Alexa's research demonstrated that even from single Kinect depth maps (thus an incomplete 3D representation), predictive models for body fat percentage could be developed [

33]. Using a Lasso regression approach with features extracted from point cloud data, the study achieved a predictive model with adjusted R² = 0.72 and RMSE = 8.02%. This finding illustrates how volumetric data, even when incomplete, can yield valuable body composition information.

5.2.3. Shape Descriptors and Curvature Analysis

Beyond simple circumference measurements, advanced shape descriptors derived from 3D voxel models provide nuanced insights into body composition. Laws et al. highlighted the value of curvature analysis for body composition assessment, establishing relationships between surface geometry characteristics and underlying tissue distribution [

35]. These shape-based features complement traditional anthropometric measures and enhance the predictive power of body composition models.

The combination of local and global shape features yields more robust body composition assessments than either approach alone. Tsoli et al. demonstrated that combining localized measurements (such as limb lengths and circumferences) with statistical features describing overall body shape variation significantly improved the accuracy of measurement predictions [

32]. Their inclusion of both feature types allowed their system to account for individual variations in body shape that might not be captured by standard anthropometric measurements alone.

5.2.4. Comparison with Traditional Methods

The accuracy of voxel-based body composition assessment relative to traditional methods represents a critical consideration for clinical adoption. Research comparing 3D scan-derived measures against Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), hydrostatic weighing, and Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) has shown promising results. Astorino et al. were among the first to investigate body composition measured with DXA compared to 3D scans, finding significant correlations between the methods though not equivalent performance [

33].

Alexa's study comparing Kinect-based fat percentage prediction against BIA measurements demonstrated the potential of depth sensing for body composition analysis while highlighting the need for further refinement [

33]. The achieved RMSE of approximately 8% represents a substantial improvement over earlier attempts but still falls short of the accuracy provided by laboratory methods, suggesting that 3D scanning technologies may serve as convenient screening tools rather than diagnostic replacements in their current form.

5.3. Gait Integration Possibilities

5.3.1. Morphology-Locomotion Relationships

The integration of 3D body modeling with gait analysis offers powerful insights into the relationship between body morphology and movement patterns. The ability to accurately capture both static body shape and dynamic locomotion provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing how morphological variations influence movement efficiency and pathology.

The Pixels2Pose system demonstrates how time-of-flight imaging can be leveraged for 3D pose estimation, creating a bridge between static body modeling and dynamic movement analysis [

31]. By transforming sensor data into accurate 3D skeletal poses, such systems enable simultaneous assessment of body morphology and movement patterns, facilitating the study of their interrelationship.

5.3.2. Biomechanical Analysis and Clinical Applications

Voxel-based body models provide precise segmentation of body parts, enabling detailed biomechanical analysis of gait. The accurate calculation of segment masses, centers of mass, and moments of inertia from volumetric data enhances the precision of inverse dynamics calculations and other biomechanical analyses. This integration has a particular relevance for clinical populations where body morphology deviations may contribute to movement abnormalities.

The parametric body models discussed by Black et al. and Tsoli et al. provide structured representations that can be animated according to captured motion data [

29,

32]. This capability enables researchers to simulate how body shape variations might influence movement mechanics, offering a powerful tool for both clinical assessment and rehabilitation planning.

5.3.3. Longitudinal Monitoring and Intervention Assessment

The combination of 3D body modeling and gait analysis creates opportunities for comprehensive longitudinal monitoring of patients undergoing rehabilitation or weight management interventions. By capturing both morphological changes and associated alterations in movement patterns, clinicians can assess intervention efficacy more holistically than with either approach alone.

The relatively low cost and portability of consumer-grade depth sensors make this integrated approach accessible for clinical practice. The work by Weiss et al. demonstrating accurate body scanning with inexpensive commodity sensors highlights the potential for widespread adoption of these technologies in clinical settings [

29], potentially revolutionizing how clinicians monitor the interplay between morphological changes and movement adaptations during recovery or disease progression.

5.4. Limitations

5.4.1. Segmentation Errors and Depth Artifacts

Despite significant advancements, 3D body reconstruction from depth sensors remains susceptible to segmentation errors and depth artifacts. The KinectFusion technique, while powerful, can produce artifacts at the boundaries between the subject and background, particularly in environments with complex geometry or variable lighting conditions [

28]. These artifacts can distort body shape reconstruction and compromise the accuracy of derived measurements.

Depth artifacts present challenges when scanning subjects with obesity. Alexa's research noted difficulties in accurately capturing body contours in participants with higher body fat percentages, as the increased tissue depth and surface curvature created shadows and occlusions in the depth map [

33]. These artifacts can lead to systematic underestimation of body volume in subjects with obesity, potentially limiting the clinical utility of the technology for this population.

5.4.2. Resolution and Surface Quality Limitations

The resolution of consumer-grade depth sensors imposes fundamental limitations on the detail level achievable in 3D body reconstruction. Li et al. addressed this challenge through their voxel super-resolution approach, which enhances the detail level of coarse 3D models [

30]. However, this approach, while improving results, cannot fully compensate for the inherent resolution limitations of the source data.

Surface quality represents another significant limitation of current approaches. The point clouds generated by depth sensors often contain noise and irregularities that impact the smoothness and accuracy of the reconstructed surface. This limitation affects the precision of curvature-based shape descriptors and may reduce the accuracy of derived anthropometric measurements, particularly for small or subtle anatomical features.

5.4.3. Posture Variability and Subject Positioning

Posture variability introduces significant challenges for 3D body reconstruction and measurement extraction. Even minor variations in standing posture can alter key anthropometric measurements and confound longitudinal comparisons. The approach by Weiss et al. using the SCAPE body model partially addresses this issue by allowing pose to vary while maintaining a consistent body shape [

29], but the challenge persists in practical applications where standardized positioning may be difficult to achieve.

Subject positioning relative to the sensor also influences reconstruction quality. Alexa's research utilized five different predetermined angles between the subject and the Kinect plane to capture comprehensive body data [

33]. This approach highlights the dependency of reconstruction quality on careful subject positioning, which may limit the practical applicability of the technology in uncontrolled environments.

5.4.4. Clothing and Surface Appearance Effects

Clothing presents a significant confusing factor for 3D body reconstruction and anthropometric measurement. Loose or bulky clothing obscures true body contours, while tight clothing may compress soft tissues and alter measurements. Most research protocols, including those reviewed here, require standardized tight-fitting clothing to minimize these effects, limiting the ecological validity of the resulting measurements.