3.1. Merging Keypoints and 3D Data

Body circumference measurement in this study is divided into three main stages. The first stage involves detecting the endpoints of the body parts to be measured from photographs taken from the front and side. The second stage is calculating the circumference between the detected endpoints, and the third stage is estimating the total circumference of the desired body part based on the measurements taken from the front and side. In this section, we describe the detailed methodology and implementation process for each stage and discuss the technical improvements introduced to overcome existing limitations.

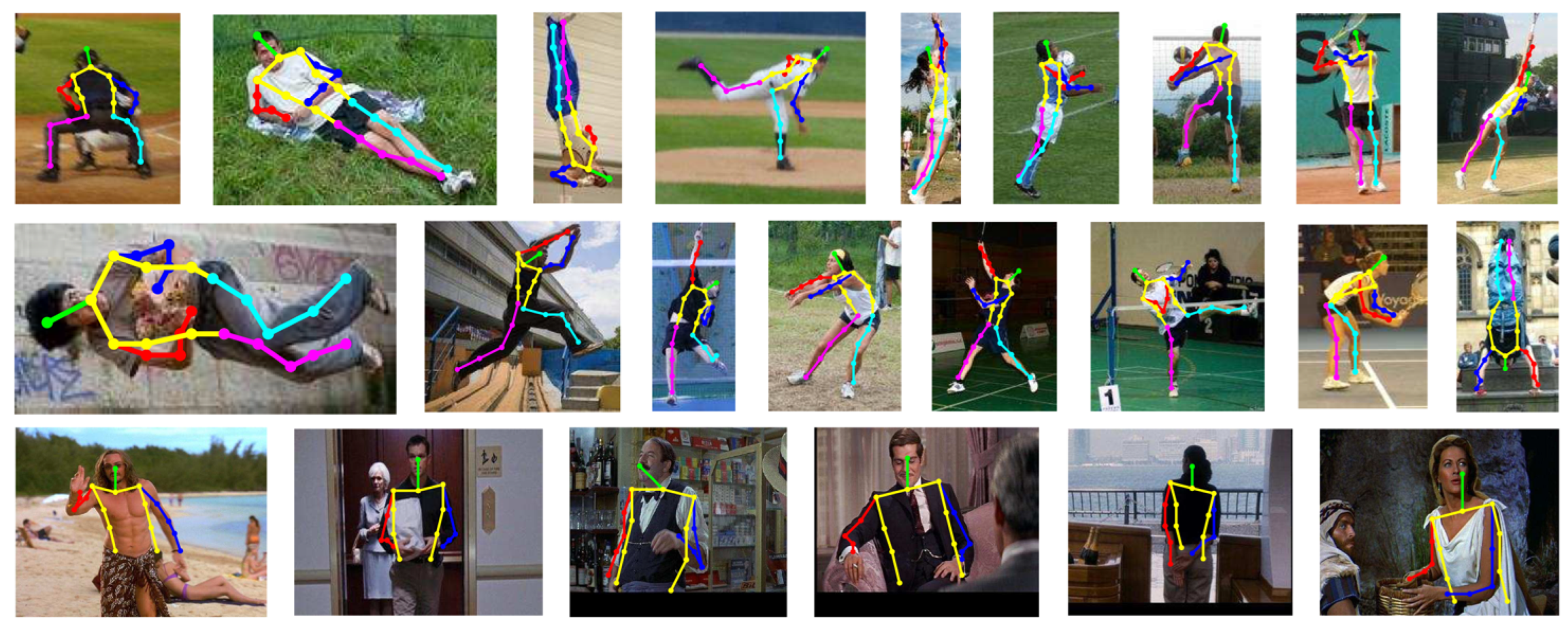

First, in the initial stage of body circumference measurement, accurately detecting the endpoints of body parts is essential. To achieve this, we utilized the Human Pose Estimation using the High-Resolution Representations (HRNet) model [

16]. HRNet excels at maintaining high-resolution representations while precisely detecting keypoints of the body, allowing for accurate identification of various body parts’ locations. However, the basic HRNet model provides only a limited number of keypoints necessary for standard pose estimation, which restricts its ability to sufficiently cover all the endpoints required for body circumference measurement.

To overcome these limitations, we applied Transfer Learning in this study. Specifically, we labeled 1,000 images of people by categorizing them into two groups: upper body and lower body. In the upper body category, we labeled the endpoints of the chest and waist, and in the lower body category, we labeled the hip and buttock as keypoints. By further training the HRNet model using this labeled dataset, we aimed to expand the model’s limited keypoint detection capabilities. The transfer learning process involved collecting 1,000 images of people divided into upper and lower body categories, manually labeling the keypoints for the chest, waist, buttock, hips, and femoral condyles in each image, and setting up based on the pre-trained HRNet model. We then retrained the last few layers of the HRNet model using the labeled dataset to accurately detect the new keypoints, evaluated the model’s performance with a validation dataset, and adjusted hyperparameters as necessary.

In the second stage, we calculate the circumference between the detected endpoints from the front and side views. This calculation is primarily based on the Euclidean distance. Specifically, we define two keypoints as

and

, and represent the distance between the two points as

. The Euclidean distance formula is as follows Equation (

1):

Under the assumption that the y-axis positions of the two points are identical, the straight-line distances in the x-axis direction are summed to approximate the circumference between the two points. Represents this calculation follows Equation (

2):

However, as mentioned earlier, the keypoints detected in 2D images do not correspond to their actual positions in 3D space, so simply doubling the circumference of the front part introduces errors. This is because the boundary surfaces of the object from the camera’s viewpoint do not coincide with the actual boundary surfaces. Considering the angle between the camera’s line of sight and the object’s boundary surface, the distance from the camera to the center of the object, the distance from the center of the object to the boundary surface, and the actual length of the object’s boundary surface, the error can be calculated as follow Equation (

3):

Therefore, the error resulting from the difference between the 2D keypoints and the 3D keypoints is represented by a length of

. For this reason, simply multiplying the circumference of the front part by two to estimate the total circumference leads to inaccurate results. Additionally, to correct the positions of the keypoints detected in 2D images to their accurate locations in 3D space, this study introduced a correction process utilizing a depth map. First, a depth map of the same scene as the RGB image captured using the iPhone’s LiDAR sensor is generated. A depth map indicates that lower values are closer to the object and higher values are further away from the object. Next, the Canny edge algorithm is applied to the depth map to detect points where the depth value changes abruptly [

18]. This is useful for accurately identifying the object’s boundary surfaces. Then, the coordinates of the keypoints detected in the 2D RGB image are transformed to match the scale of the depth map and moved to the nearest edge point. This process includes the following two steps: matching the resolution of the RGB image with that of the depth map.

First, a depth map of the same scene as the RGB image captured using the iPhone’s LiDAR sensor is generated. A depth map indicates that lower values are closer to the object and higher values are further away from the object. Next, the Canny edge algorithm is applied to the depth map to detect points where the depth value changes abruptly. This is useful for accurately identifying the object’s boundary surfaces. Then, the coordinates of the keypoints detected in the 2D RGB image are transformed to match the scale of the depth map and moved to the nearest edge point. This process includes the following two steps: matching the resolution of the RGB image with that of the depth map.

For example, if the RGB image size is (

) and the depth map size is (

), the keypoint coordinates of the RGB image are divided by 7.5 to convert them to the depth map coordinates. Then, the nearest edge point is searched from the transformed keypoint coordinates, and the keypoint is moved to that point. Finally, to verify that the corrected keypoints coincide with the actual boundary surfaces of the object, the positions on the depth map and the visual positions on the RGB image are compared and analyzed. Through this correction process, the keypoints detected in the 2D image were adjusted to match their actual positions in 3D space. This significantly improved the accuracy of body circumference measurements. In the keypoints correction stage, the circumferences measured from the front and side are integrated to estimate the total circumference of the body part. To do this, a regression equation was derived by multiplying the circumference values measured from the front and side by a certain constant to calculate the total circumference. This equation was applied only when measuring the dimensions of actual people, and experiments were conducted to find the optimal constant for each body part. The results are as follows Equation (

4):

These constants were derived through regression analysis by comparing the actual circumferences of various body parts with the measured values. This allowed for the accurate estimation of the total circumference based on the measurements taken from the front and side. Additionally, regression analysis is a statistical method that derives constants based on measured data and actual data. In this study, measurement data for various body parts were collected, and constant values were derived based on this data. This enabled the identification of optimal constant values that minimize measurement errors.

3.2. Utilization of Uniform 3D Data

In this study, to enhance the accuracy and consistency of the body measurement algorithm, experiments were conducted using uniform 3D data such as cylinder and mannequin. These standardized 3D objects, which closely resemble the human body while exhibiting minimal deformation, were useful for systematically verifying the performance of the algorithm in its initial stages. Cylinders, with their simple structure, are ideal objects for evaluating whether the algorithm can accurately measure complex body structures. Additionally, mannequin, which mimic the shape of the human body, were used to test the measurement accuracy of various body parts. Through this approach, it was confirmed that the algorithm could accurately measure body parts of different shapes and sizes. The experimental procedure involved first capturing RGB images and depth maps of the cylinder and mannequin from various angles using an iPhone’s LiDAR sensor. Using an HRNet-based keypoint detection model, the endpoints of the major parts of each object were detected. The detected keypoints were then adjusted to their accurate positions in 3D space through the aforementioned correction process. Based on the corrected keypoints, circumferences were calculated, and the total circumference was estimated by integrating the measurements taken from the front and side views. The measured circumference values were compared with the actual values to evaluate the accuracy of the algorithm. Through these experiments, the accuracy and consistency of the proposed body circumference measurement algorithmwere systematically validated, and methods to minimize errors in measuring various body parts were established.

The body circumference measurement algorithm proposed in this study consists of the following key components. First, RGB images and depth maps are extracted at the same scale to facilitate subsequent data merging and analysis. Second, the keypoints detected by the HRNet model are adjusted to accurate 3D positions through a depth map-based correction process. Third, the circumferences of body parts are calculated using the corrected keypoints, and the total circumference is estimated by integrating the measurements taken from the front and side views. Finally, a regression equation was derived to estimate the total circumference based on the measured circumferences from the front and side views, enabling accurate measurements. Additionally, to enhance the efficiency of the algorithm, the following optimization techniques were introduced. First, model lightweighting and parallel processing were employed to enable real-time body circumference measurements. Data captured from various angles and lighting conditions were utilized to improve the model’s generalization performance. Furthermore, filtering techniques were applied to minimize noise in the depth maps.

3.3. Experimental Environment and Dataset

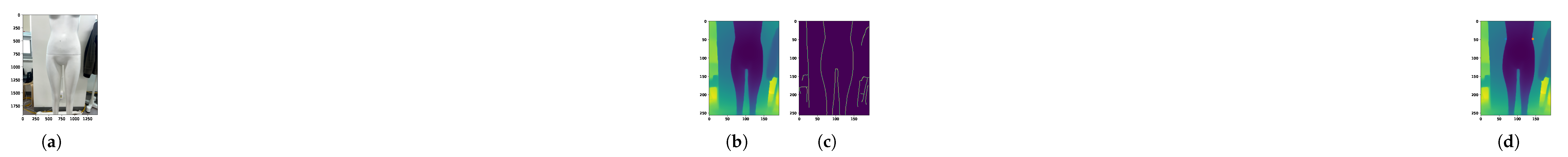

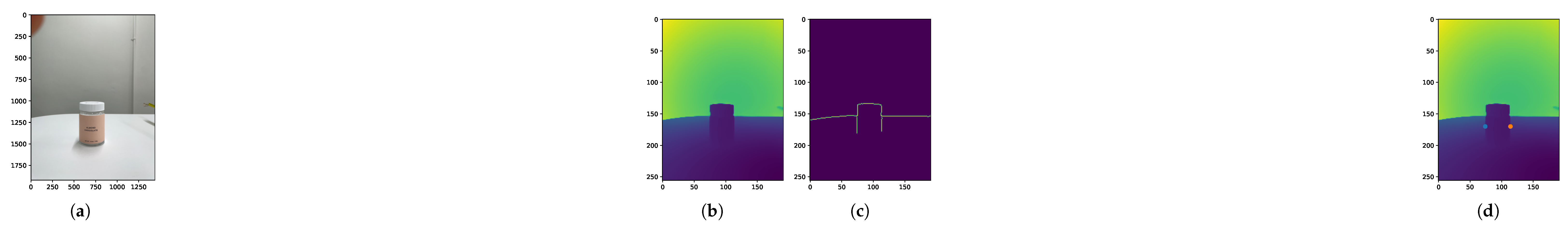

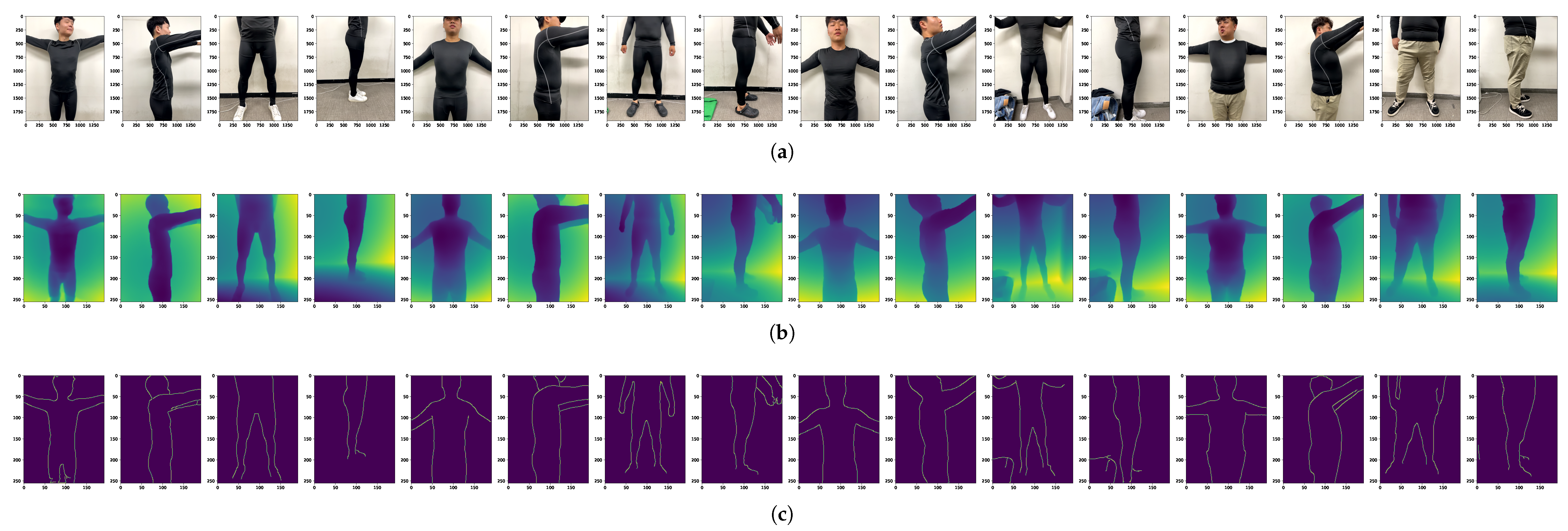

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, uniform 3D data such as cylinder and mannequin were used to ensure the consistency and reproducibility of the experiments. In

Figure 2 and

Figure 3,

(b) in each figure is a depth map visualizing the distance between the camera and the object. Lower depth values are represented by darker colors, while higher depth values are represented by brighter colors, visually depicting the three-dimensional structure of the object. The actual circumference of the cylinder is 17.27cm, and the estimated circumference measured by LiDAR is 17.68cm, demonstrating an accuracy within a 3% error margin. The results for the cylinder and mannequin are shown in

Table 11, respectively. The regression equation is tailored to humans, and the Mannequin has a different shape compared to an actual person, resulting in slightly larger errors. The experimental environment involved using a model equipped with an iPhone’s LiDAR sensor to simultaneously collect RGB images and depth maps, maintaining data consistency by photographing objects under the same lighting conditions and fixed distances. Through such standardized datasets, the performance of the algorithm could be systematically evaluated, and errors that could occur in measuring various body parts could be analyzed.

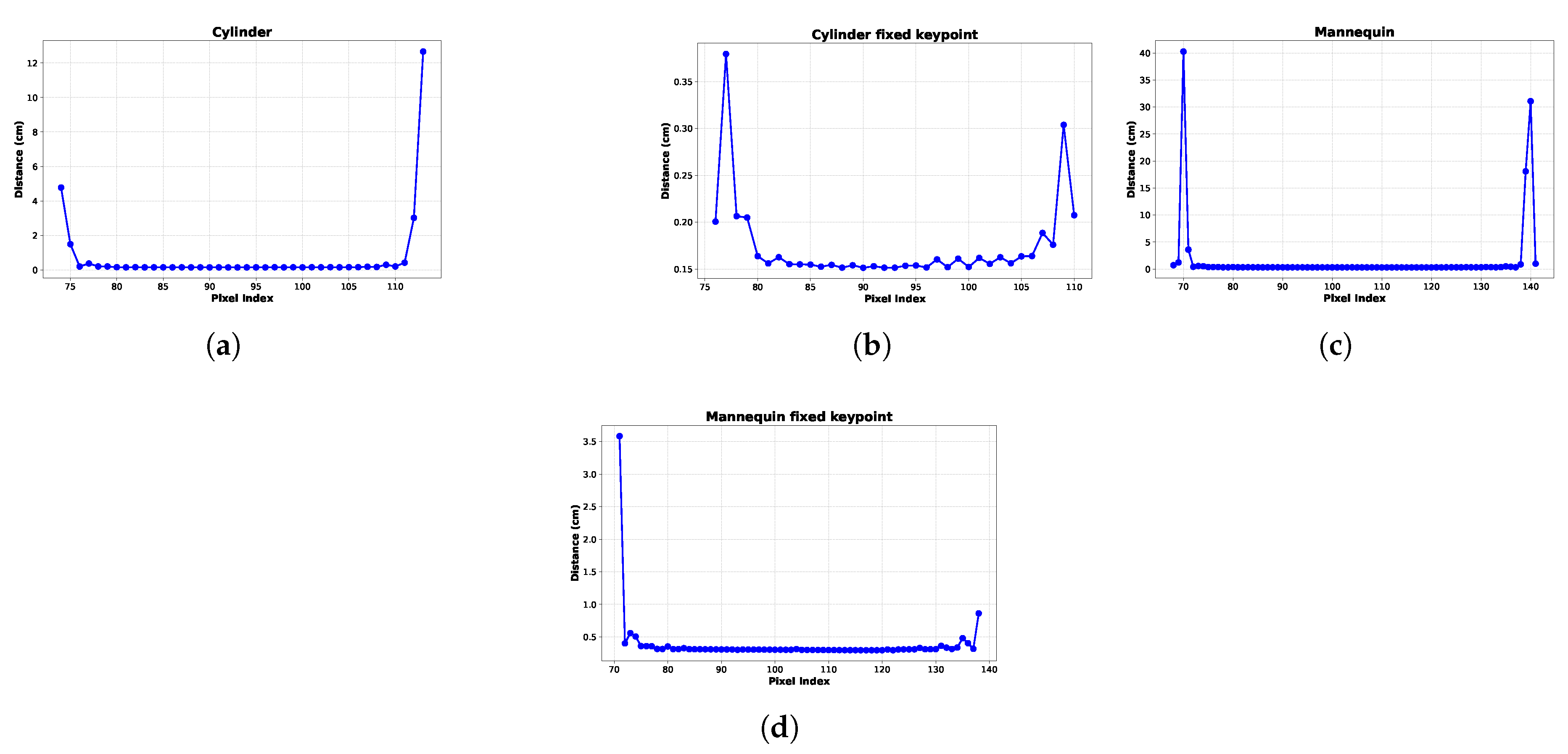

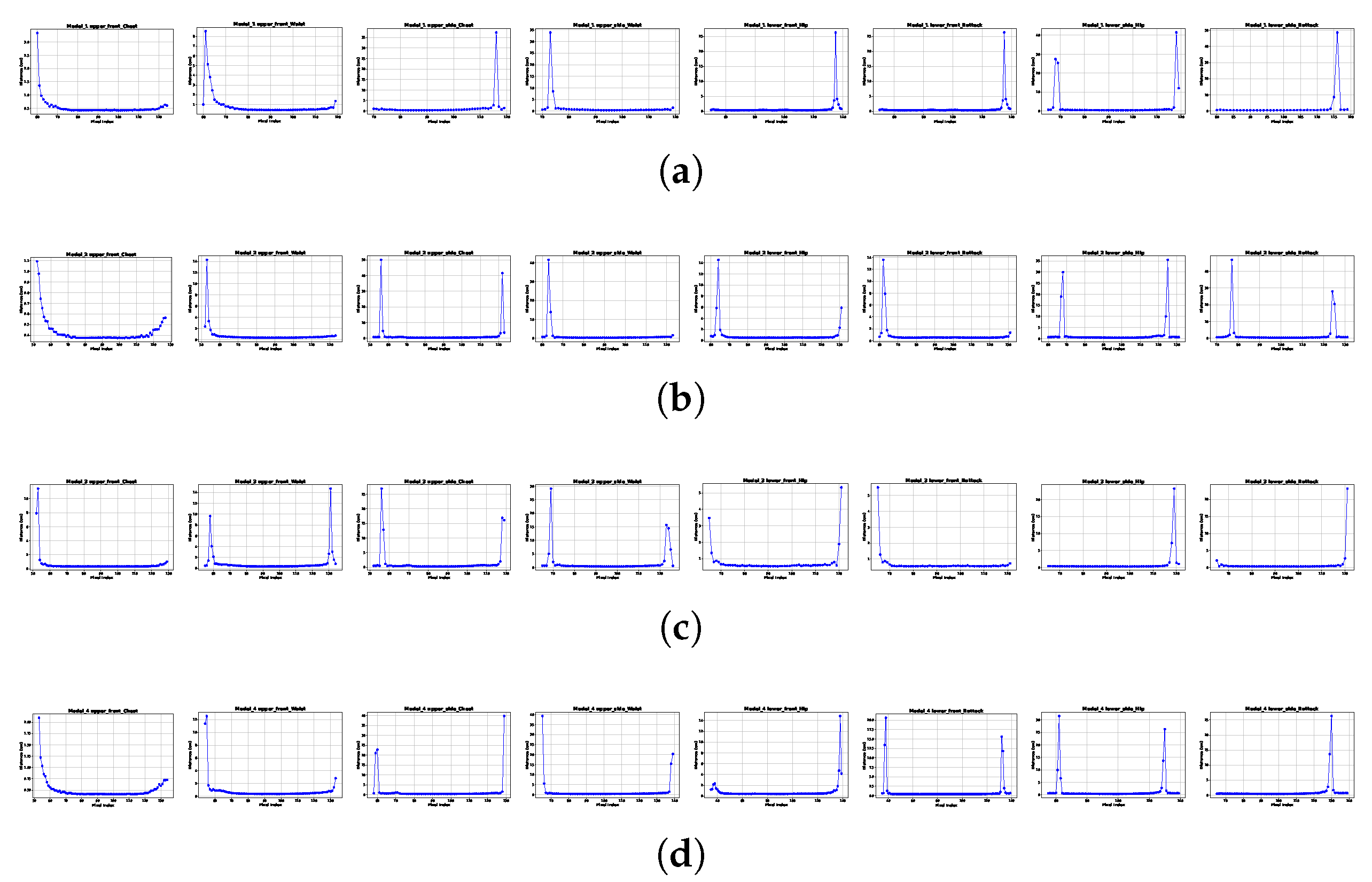

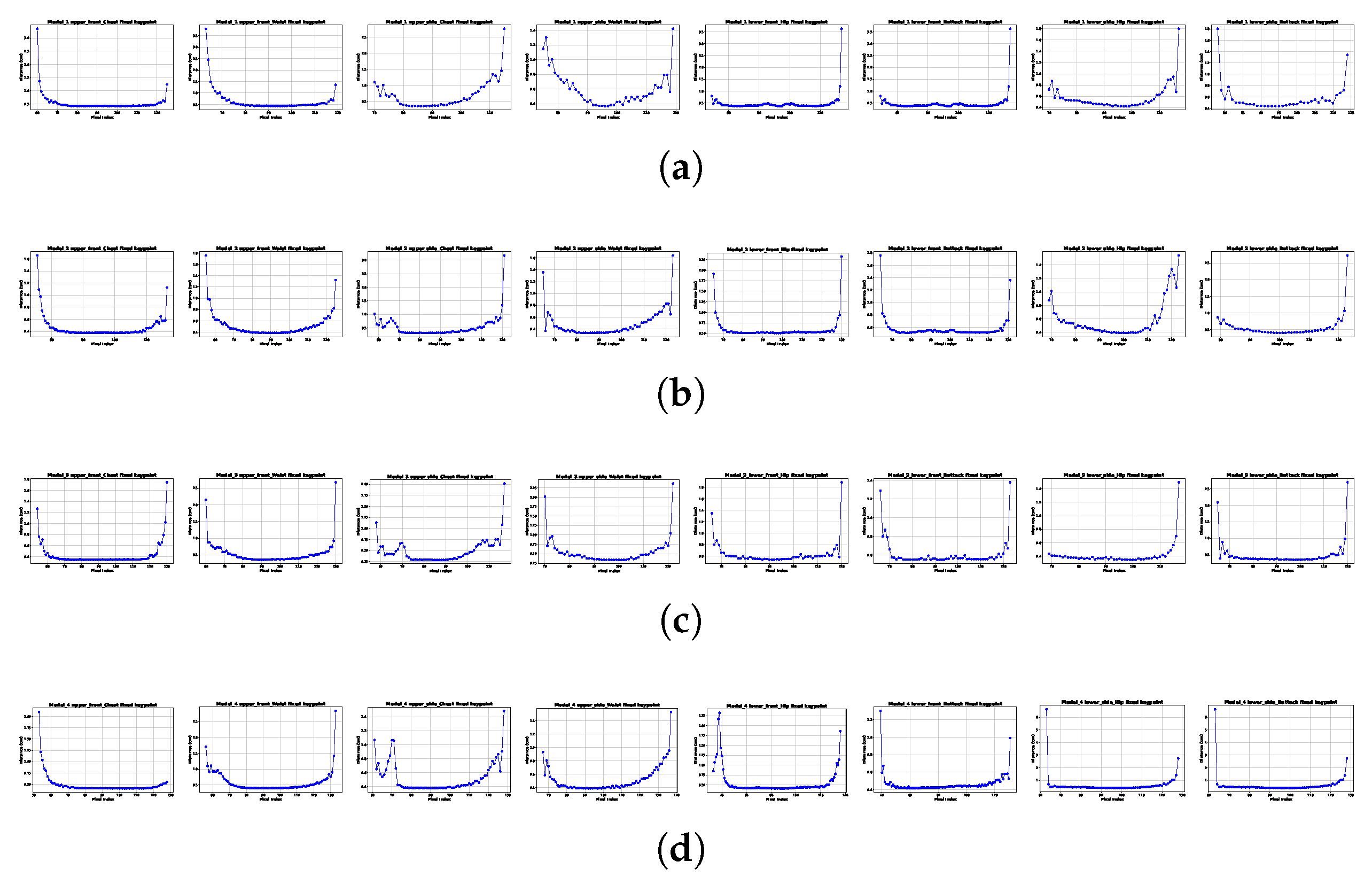

Figures

(a) and

(c) in

Figure 4 visualize the distance measurements before correction for the cylinder and mannequin, respectively. Distance values exceeding 12cm between adjacent pixels were observed, which can be interpreted as the distance between the object and the background rather than within the object itself. Points where the values suddenly increase indicate locations beyond the object’s boundary. In contrast, Figures

(b) and

(d) show the distance measurements after correction for the cylinder and mannequin, respectively, with the maximum value not exceeding 1cm. This suggests that by detecting edges using depth values and correcting the keypoints, the lengths to the object’s boundary surfaces were accurately measured.