Submitted:

17 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

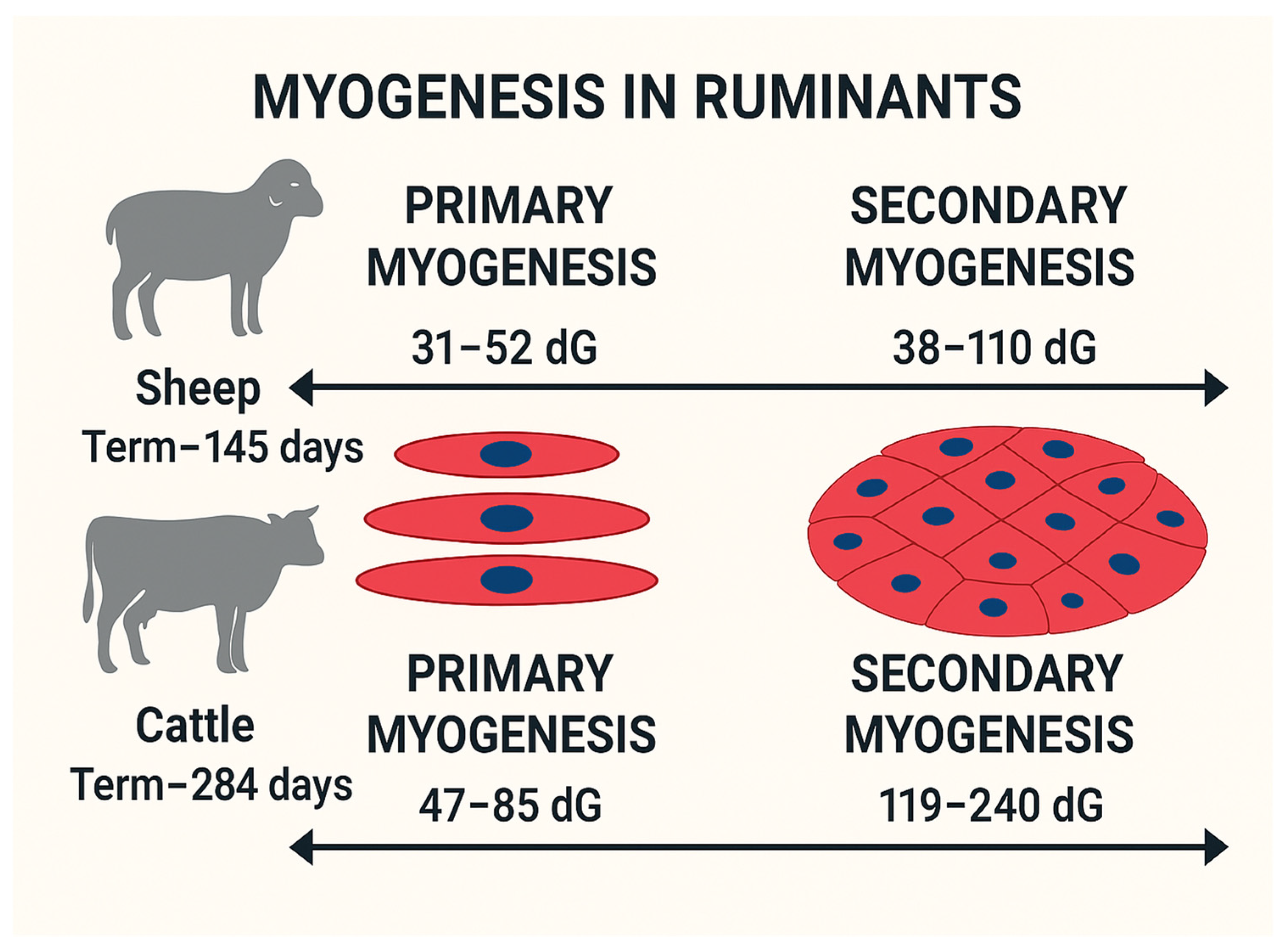

2. Prenatal Muscle Development in Ruminants

Fetal Programming and Muscle Development

Maternal Nutrition and Muscle Development

3. Postnatal Muscle Development in Ruminants

Mechanisms of Postnatal Muscle Growth

Nutritional and Environmental Influences on Muscle Growth

4. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, R.G.; Oteruelo, F.T. An Ultrastructural Study of the Differentiation of Skeletal Muscle in the Bovine Fetus. Anatomy and Embryology 1981, 162, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.-J.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Du, M. Effect of Maternal Nutrient Restriction in Sheep on the Development of Fetal Skeletal Muscle1. Biol Reprod 2004, 71, 1968–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.C.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Duarte, M. de S. Fetal Programming in Ruminant Animals: Understanding the Skeletal Muscle Development to Improve Meat Quality. Animal Frontiers 2021, 11, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zhu, M.J.; Underwood, K.R.; Hess, B.W.; Ford, S.P.; Du, M. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase and Adipogenesis in Sheep Fetal Skeletal Muscle and 3T3-L1 Cells. J Anim Sci 2008, 86, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M. Prenatal Development of Muscle and Adipose and Connective Tissues and Its Impact on Meat Quality. Meat and Muscle Biology 2023, 7, 16230–16231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Tong, J.; Zhao, J.; Underwood, K.R.; Zhu, M.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W. Fetal Programming of Skeletal Muscle Development in Ruminant Animals1. J Anim Sci 2010, 88, E51–E60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Diniz, W.J.S.; Menezes, A.C.B.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Ward, A.K. Maternal Mineral Nutrition Regulates Fetal Genomic Programming in Cattle: A Review. Metabolites 2023, 13, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, D.C.; Paulino, M.F.; Rennó, L.N.; Villadiego, F.C.; Ortega, R.M.; Moreno, D.S.; Martins, L.S.; De Almeida, D.M.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Manso, M.R.; et al. Supplementation of Grazing Beef Cows during Gestation as a Strategy to Improve Skeletal Muscle Development of the Offspring. animal 2017, 11, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, F.; Wood, K.M.; Swanson, K.C.; Miller, S.P.; McBride, B.W.; Fitzsimmons, C. Maternal Nutrient Restriction in Mid-to-Late Gestation Influences Fetal MRNA Expression in Muscle Tissues in Beef Cattle. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listrat, A.; Lebret, B.; Louveau, I.; Astruc, T.; Bonnet, M.; Lefaucheur, L.; Picard, B.; Bugeon, J. How Muscle Structure and Composition Influence Meat and Flesh Quality. The Scientific World Journal 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, A.F.; Funston, R.N. FETAL PROGRAMMING: IMPLICATIONS FOR BEEF CATTLE PRODUCTION. Proceedings Range Beef Cow Symposium 2013, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yair, R.; Kalcheim, C. Lineage Analysis of the Avian Dermomyotome Sheet Reveals the Existence of Single Cells with Both Dermal and Muscle Progenitor Fates. Development 2005, 132, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, S.; Chung, U. il; Ohba, S.; Hojo, H. Understanding Paraxial Mesoderm Development and Sclerotome Specification for Skeletal Repair. Exp Mol Med 2020, 52, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.; Reshef, R.; Münsterberg, A.E.; Koester, S.; Goulding, M.; Lassar, A.B. Ectopic Pax-3 Activates MyoD and Myf-5 Expression in Embryonic Mesoderm and Neural Tissue. Cell 1997, 89, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, J.P.K.; McCall, G.E.; Kander, E.M.; Zhong, H.; Roy, R.R.; Huey, K.A. PAX3/7 Expression Coincides with Myod during Chronic Skeletal Muscle Overload. Muscle Nerve 2008, 38, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Zhu, M.-J.; Dodson, M. V.; Du, M. Developmental Programming of Fetal Skeletal Muscle and Adipose Tissue Development. J Genomics 2013, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, M.M.; Avram, A.S.; James, W.D. Subcutaneous Fat in Normal and Diseased States: 3. Adipogenesis: From Stem Cell to Fat Cell. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 56, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, M.; Cassar-Malek, I.; Chilliard, Y.; Picard, B. Ontogenesis of Muscle and Adipose Tissues and Their Interactions in Ruminants and Other Species. Animal 2010, 4, 1093–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.M.; Camacho, L.E.; Ebarb, S.M.; Swanson, K.C.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Stelzleni, A.M.; Johnson, S.E. Realimentation of Nutrient Restricted Pregnant Beef Cows Supports Compensatory Fetal Muscle Growth. J Anim Sci 2013, 91, 4797–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, C.G.; Montarras, D.; Buckingham, M. Muscle Satellite Cells Are Primed for Myogenesis but Maintain Quiescence with Sequestration of Myf5 MRNA Targeted by MicroRNA-31 in MRNP Granules. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB Pathway: Insights from Genetic Models. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Zhao, J.X.; Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Nicodemus, L. V.; Yue, W.; Mccormick, R.J.; Zhu, M.J. Fetal Muscle Development, Mesenchymal Multipotent Cell Differentiation, and Associated Signaling Pathways. J Anim Sci 2011, 89, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.C.; Du, M.; Nascimento, K.B.; Galvão, M.C.; Meneses, J.A.M.; Schultz, E.B.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Duarte, M. de S. Skeletal Muscle Development in Postnatal Beef Cattle Resulting from Maternal Protein Restriction during Mid-Gestation. Animals 2021, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallafacchina, G.; Blaauw, B.; Schiaffino, S. Role of Satellite Cells in Muscle Growth and Maintenance of Muscle Mass. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2013, 23, S12–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Patel, K.; Lasagna, E. The Myostatin Gene: An Overview of Mechanisms of Action and Its Relevance to Livestock Animals. Anim Genet 2018, 49, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.J.P. The Fetal and Infant Origins of Adult Disease. BMJ : British Medical Journal 1990, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.C.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Duarte, M. de S. Fetal Programming in Ruminant Animals: Understanding the Skeletal Muscle Development to Improve Meat Quality. Anim Front 2021, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauncey, M.J.; Gilmour, R.S. Regulatory Factors in the Control of Muscle Development. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1996, 55, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.; Holowacz, T.; Lassar, A.B. The Origin of Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells in the Embryo and the Adult. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2001, 13, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncaut, N.; Rigby, P.W.J.; Carvajal, J.J. Dial M(RF) for Myogenesis. FEBS J 2013, 280, 3980–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Rigby, P.W.J. Gene Regulatory Networks and Transcriptional Mechanisms That Control Myogenesis. Dev Cell 2014, 28, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.J.; McEwan, J.C.; Sheard, P.W.; Harris, A.J. Early Stages of Myogenesis in a Large Mammal: Formation of Successive Generations of Myotubes in Sheep Tibialis Cranialis Muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1992, 13, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; McEwan, J.C.; Dodds, K.G.; Fischman, D.A.; Fitzsimons, R.B.; Harris, A.J. Myosin Heavy Chain Composition of Single Fibres and Their Origins and Distribution in Developing Fascicles of Sheep Tibialis Cranialis Muscles. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1992, 13, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.A.; Raja, J.S.; Hoffman, M.L.; Zinn, S.A.; Govoni, K.E. Poor Maternal Nutrition Inhibits Muscle Development in Ovine Offspring. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2014, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.E.; Jones, A.K.; Pillai, S.M.; Hoffman, M.L.; McFadden, K.K.; Zinn, S.A.; Govoni, K.E.; Reed, S.A. Maternal Restricted- and Over-Feeding During Gestation Result in Distinct Lipid and Amino Acid Metabolite Profiles in the Longissimus Muscle of the Offspring. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 448206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.S.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Paulino, P.V.R.; Serão, N.V.L.; Nascimento, C.S.; Botelho, M.E.; Martins, T.S.; Filho, S.C. V.; Dodson, M. V.; Guimarães, S.E.F.; et al. Maternal Overnutrition Enhances MRNA Expression of Adipogenic Markers and Collagen Deposition in Skeletal Muscle of Beef Cattle Fetuses1. J Anim Sci 2014, 92, 3846–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, M.C.; Pillai, S.M.; Reed, S.A.; Stevens, J.R.; Hoffman, M.L.; Jones, A.K.; Zinn, S.A.; Govoni, K.E. Poor Maternal Nutrition during Gestation in Sheep Alters Prenatal Muscle Growth and Development in Offspring. J Anim Sci 2020, 98, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L.; Peck, K.N.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Reed, S.A.; Zinn, S.A.; Govoni, K.E. Poor Maternal Nutrition during Gestation Alters the Expression of Genes Involved in Muscle Development and Metabolism in Lambs1. J Anim Sci 2016, 94, 3093–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, S.P.; Kleemann, D.O.; Kakar, M.A.; Owens, J.A.; Nattrass, G.S.; Maddocks, S.; Walker, S.K. Myogenesis in Sheep Is Altered by Maternal Feed Intake during the Peri-Conception Period. Anim Reprod Sci 2005, 87, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.F.; Yan, X.; Zhu, M.J.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Du, M. Maternal Obesity Downregulates Myogenesis and β-Catenin Signaling in Fetal Skeletal Muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009, 296, E917–E924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.R.; Regnault, T.R.H.; Brown, L.D.; Rozance, P.J.; Keng, J.; Roper, M.; Wilkening, R.B.; Hay, W.W.; Friedman, J.E. Intrauterine Growth Restriction Increases Fetal Hepatic Gluconeogenic Capacity and Reduces Messenger Ribonucleic Acid Translation Initiation and Nutrient Sensing in Fetal Liver and Skeletal Muscle. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3021–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, M.S.; Caton, J.S.; Cushman, R.A.; McLean, K.J.; Dahlen, C.R.; Borowicz, P.P.; Reynolds, L.P.; Ward, A.K. Moderate Nutrient Restriction of Beef Heifers Alters Expression of Genes Associated with Tissue Metabolism, Accretion, and Function in Fetal Liver, Muscle, and Cerebrum by Day 50 of Gestation. Transl Anim Sci 2019, 3, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, W.J.S.; Crouse, M.S.; Cushman, R.A.; McLean, K.J.; Caton, J.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Ward, A.K. Cerebrum, Liver, and Muscle Regulatory Networks Uncover Maternal Nutrition Effects in Developmental Programming of Beef Cattle during Early Pregnancy. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Review: Feed Demand Landscape and Implications of Food-Not Feed Strategy for Food Security and Climate Change. animal 2018, 12, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, C.; Cowley; Cortney Long-Term Pressures and Prospects for the U.S. Cattle Industry. Economic Review 2021, vol.107. [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Ford, S.P.; Zhu, M.-J. Optimizing Livestock Production Efficiency through Maternal Nutritional Management and Fetal Developmental Programming. Animal Frontiers 2017, 7, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.X.; Rogers, C.J.; Zhu, M.J.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Du, M. Maternal Obesity Downregulates MicroRNA Let-7g Expression, a Possible Mechanism for Enhanced Adipogenesis during Ovine Fetal Skeletal Muscle Development. International Journal of Obesity 2012, 37, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, M.S.; Caton, J.S.; Cushman, R.A.; McLean, K.J.; Dahlen, C.R.; Borowicz, P.P.; Reynolds, L.P.; Ward, A.K. Moderate Nutrient Restriction of Beef Heifers Alters Expression of Genes Associated with Tissue Metabolism, Accretion, and Function in Fetal Liver, Muscle, and Cerebrum by Day 50 of Gestation. Transl Anim Sci 2019, 3, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.R.; Regnault, T.R.H.; Brown, L.D.; Rozance, P.J.; Keng, J.; Roper, M.; Wilkening, R.B.; Hay, W.W.; Friedman, J.E. Intrauterine Growth Restriction Increases Fetal Hepatic Gluconeogenic Capacity and Reduces Messenger Ribonucleic Acid Translation Initiation and Nutrient Sensing in Fetal Liver and Skeletal Muscle. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3021–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Foren, A.; Meikle, A.; de Brun, V.; Graña-Baumgartner, A.; Abecia, J.A.; Sosa, C. Metabolic Memory Determines Gene Expression in Liver and Adipose Tissue of Undernourished Ewes. Livest Sci 2022, 260, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L.; Rokosa, M.A.; Zinn, S.A.; Hoagland, T.A.; Govoni, K.E. Poor Maternal Nutrition during Gestation in Sheep Reduces Circulating Concentrations of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I and Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-3 in Offspring. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2014, 49, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.K.; Hoffman, M.L.; Pillai, S.M.; McFadden, K.K.; Govoni, K.E.; Zinn, S.A.; Reed, S.A. Gestational Restricted- and over-Feeding Promote Maternal and Offspring Inflammatory Responses That Are Distinct and Dependent on Diet in Sheep†. Biol Reprod 2018, 98, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.M.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W. Maternal Obesity Eliminates the Neonatal Lamb Plasma Leptin Peak. J Physiol 2011, 589, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassar-Duchossoy, L.; Giacone, E.; Gayraud-Morel, B.; Jory, A.; Gomès, D.; Tajbakhsh, S. Pax3/Pax7 Mark a Novel Population of Primitive Myogenic Cells during Development. Genes Dev 2005, 19, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, J.R.; Heslop, L.; Yu, D.S.W.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Kelly, R.G.; Wernig, A.; Buckingham, M.E.; Partridge, T.A.; Zammit, P.S. Expression of Cd34 and Myf5 Defines the Majority of Quiescent Adult Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. J Cell Biol 2000, 151, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, S.; Kuroda, K.; Le Grand, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Asymmetric Self-Renewal and Commitment of Satellite Stem Cells in Muscle. Cell 2007, 129, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnell, I.W.; Ishibashi, J.; Le Grand, F.; Punch, V.G.J.; Addicks, G.C.; Greenblatt, J.F.; Dilworth, F.J.; Rudnicki, M.A. Pax7 Activates Myogenic Genes by Recruitment of a Histone Methyltransferase Complex. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, Y.I.; Wang, Y.X.; McKinnell, I.W.; Bedford, M.T.; Rudnicki, M.A. Carm1 Regulates Pax7 Transcriptional Activity Through MLL1/2 Recruitment During Asymmetric Satellite Stem Cell Divisions. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deato, M.D.E.; Marr, M.T.; Sottero, T.; Inouye, C.; Hu, P.; Tjian, R. MyoD Targets TAF3 /TRF3 to Activate Myogenin Transcription. Mol Cell 2008, 32, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. Myostatin: A Skeletal Muscle Chalone. Annu Rev Physiol 2023, 85, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.R.; Lee, K. INVITED REVIEW: Inhibitors of Myostatin as Methods of Enhancing Muscle Growth and Development. J Anim Sci 2016, 94, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinge, R.H.S.; Liberles, D.A.; Iaschi, S.P.A.; O’Brien, P.A.; Tay, G.K. Myostatin and Its Implications on Animal Breeding: A Review. Anim Genet 2005, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreurs, N.M.; Garcia, F.; Jurie, C.; Agabriel, J.; Micol, D.; Bauchart, D.; Listrat, A.; Picard, B. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Animal Maturity on Muscle Characteristics in Different Muscles, Breeds, and Sexes of Cattle. J Anim Sci 2008, 86, 2872–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittante, G.; Cecchinato, A.; Tagliapietra, F.; Verdiglione, R.; Simonetto, A.; Schiavon, S. Crossbred Young Bulls and Heifers Sired by Double-Muscled Piemontese or Belgian Blue Bulls Exhibit Different Effects of Sexual Dimorphism on Fattening Performance and Muscularity but Not on Meat Quality Traits. Meat Sci 2018, 137, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünger, L.; Navajas, E.A.; Stevenson, L.; Lambe, N.R.; Maltin, C.A.; Simm, G.; Fisher, A.V.; Chang, K.C. Muscle Fibre Characteristics of Two Contrasting Sheep Breeds: Scottish Blackface and Texel. Meat Sci 2009, 81, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Mitsumoto, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Itoh, N.; Itagaki, K.; Kohno, Y.; Dohgo, T. The Characteristics of Muscle Fiber Types of Longissimus Thoracis Muscle and Their Influences on the Quantity and Quality of Meat from Japanese Black Steers. Meat Sci 2000, 54, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, N.J.; Reverter, A.; Greenwood, P.L.; Guo, B.; Cafe, L.M.; Dalrymple, B.P. Longitudinal Muscle Gene Expression Patterns Associated with Differential Intramuscular Fat in Cattle. Animal 2015, 9, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corah, L.R.; Dunn, T.G.; Kaltenbach, C.C. Influence of Prepartum Nutrition on the Reproductive Performance of Beef Females and the Performance of Their Progeny. J Anim Sci 1975, 41, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.R.; Mohrhauser, D.A.; Pritchard, R.H.; Underwood, K.R.; Wertz-Lutz, A.E.; Blair, A.D. The Influence of Maternal Energy Status during Mid-Gestation on Growth, Cattle Performance, and the Immune Response in the Resultant Beef Progeny. Professional Animal Scientist 2016, 32, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrhauser, D.A.; Taylor, A.R.; Underwood, K.R.; Pritchard, R.H.; Wertz-Lutz, A.E.; Blair, A.D. The Influence of Maternal Energy Status during Midgestation on Beef Offspring Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality. J Anim Sci 2015, 93, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.M.; Ineck, N.E.; Quarnberg, S.M.; Legako, J.F.; Carpenter, C.E.; Rood, K.A.; Thornton-Kurth, K.J.; Gardner, J.M.; Ineck, N.E.; Quarnberg, S.M.; et al. The Influence of Maternal Dietary Intake During Mid-Gestation on Growth, Feedlot Performance, MiRNA and MRNA Expression, and Carcass and Meat Quality of Resultant Offspring. Meat and Muscle Biology 2021, 5, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.P.; Long, N.M.; Ford, S.P.; Long, N.M. Evidence for Similar Changes in Offspring Phenotype Following Either Maternal Undernutrition or Overnutrition: Potential Impact on Fetal Epigenetic Mechanisms. Reprod Fertil Dev 2011, 24, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehfeldt, C.; Te Pas, M.F.W.; Wimmers, K.; Brameld, J.M.; Nissen, P.M.; Berri, C.; Valente, L.M.P.; Power, D.M.; Picard, B.; Stickland, N.C.; et al. Advances in Research on the Prenatal Development of Skeletal Muscle in Animals in Relation to the Quality of Muscle-Based Food. I. Regulation of Myogenesis and Environmental Impact. Animal 2011, 5, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model Animal | Treatments | Gestation Stage | Effects | Reference |

| Sheep | Maternal nutrient restriction (half maintenance requirements vs. 1.5 times maintenance requirements) | Periconceptual period (18 days before and 6 days after ovulation) | Decrease in muscle fiber count in the restricted nutrition group compared to the control | [39] |

| Cattle | Maternal nutrient restriction (ADG -0.08 kg/d vs. ADG 0.5 kg/d) | Early gestation (first 50 days of gestation) | Altered expressions of MRF, MYOG, and MYOD1 in fetal hind limb muscle tissues in the restricted nutrition group. | [42] |

| Sheep | Maternal nutrient restriction and overnutrition (under: ADG = 0.047 kg/d; over: ADG = 0.226 kg/d; control: ADG = 0.135 kg/d) | Early gestation to parturition (45-135 dG) | Increased cross-sectional area of muscle fibers consistent with fetal growth trajectory; downregulation of MYF5 and PAX7 associated with negative impacts on myogenesis at birth. | [37] |

| Cattle | Maternal nutrient restriction and overnutrition (ADG = 0.59 kg/d vs. ADG = 1.11 kg/d) | Mid-to-late gestation (147-247 dG) | Increased expression of MYOD1 and MYOG in the restricted nutrition group compared to the overnutrition group. | [9] |

| Sheep | Maternal overnutrition (150% of maintenance requirements vs. maintenance requirements only) | From 60 days before gestation to parturition | Lower leptin concentration neonatally in the overnutrition group, indicating potential impacts on marbling and myogenesis. | [53] |

| Sheep | Maternal overnutrition (150% of maintenance requirements vs. control) | Periconceptual period (60 days before gestation to 75 dG) | Downregulation of MRF (MyoD and MYOG) in the overnutrition group compared to the control group. | [40] |

| Cattle | Maternal nutrient restriction leads to the loss of body condition score by 1 or maintains score of 5.0 | Mid gestational nutrient restriction (from start to end of mid-gestation) to study postnatal birth and weaning effects | Early growth suppressed; improved marbling-to-backfat ratio and tenderness in the restricted group | [69,70,71] |

| Sheep | Early to mid gestation maternal nutrient restriction (50% of NRC requirement) vs control-fed ewes (100% of NRC requirement) | Study the impacts of midgestational maternal Nutrient restriction on carcass and morphometric measures of lambs at harvesting (day 280 postnatally) | Lambs from restricted ewes were heavier and had more backfat at slaughter | [72] |

| Cattle | Prepartum nutrient restriction (heifers 65%, cows 50% NRC compared to 100% NRC as control for 100 days) | Postnatal (birth to weaning) | Lower calf birth/weaning weights; increased mortality rates | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).