Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

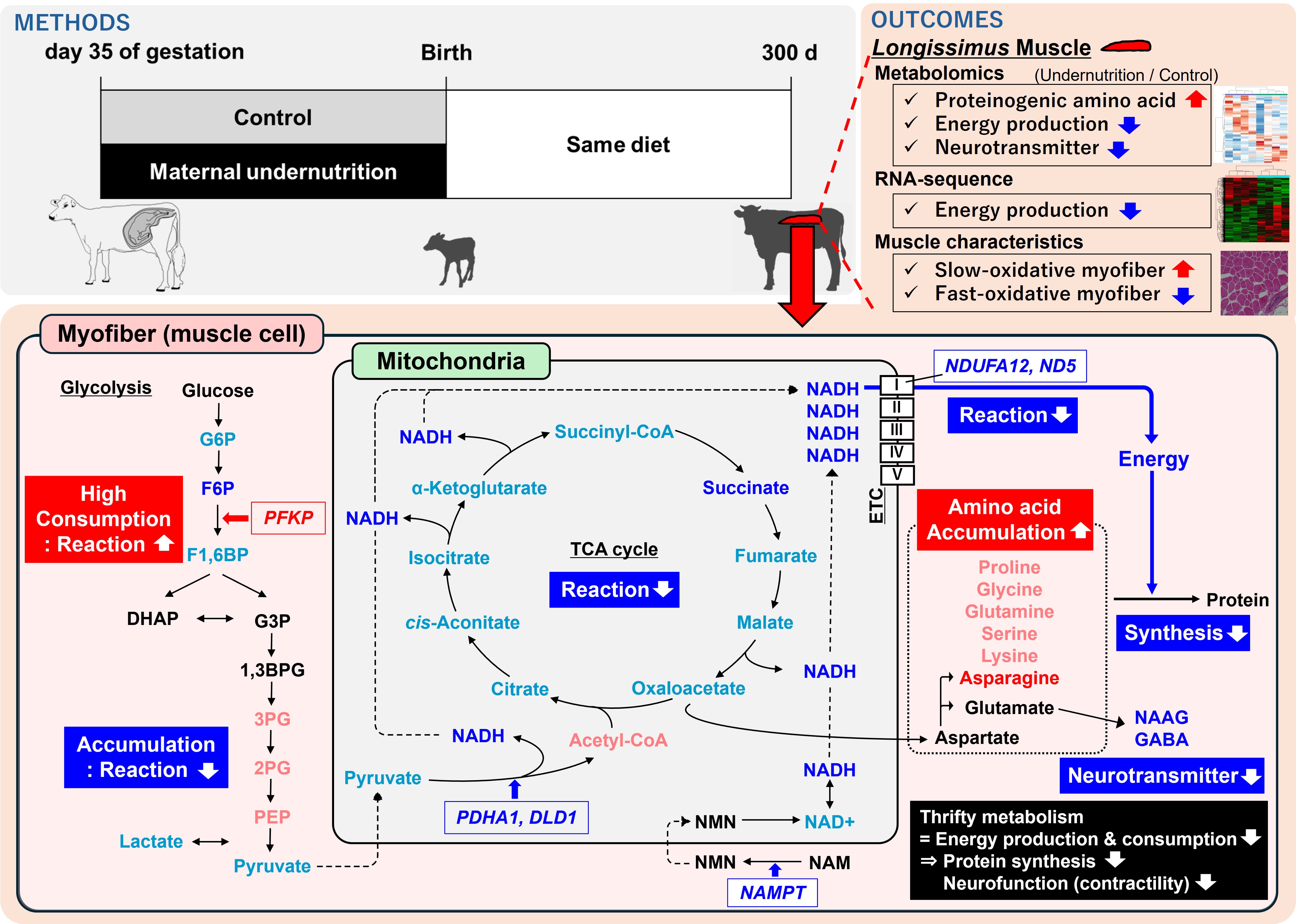

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

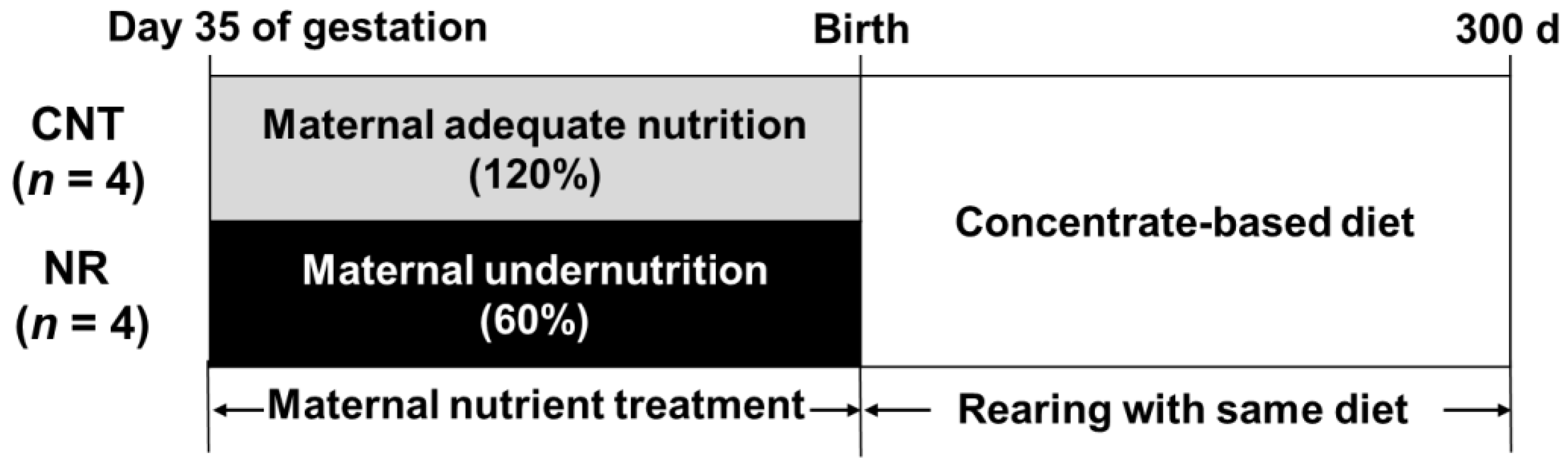

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Longissimus Thoracis Muscle Sampling

2.3. Metabolomics and Pathway Analysis

2.4. RNA Sequencing and Pathway Analysis

2.5. Muscle and Adipocyte Histochemical Properties, and Myofiber Type Composition

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

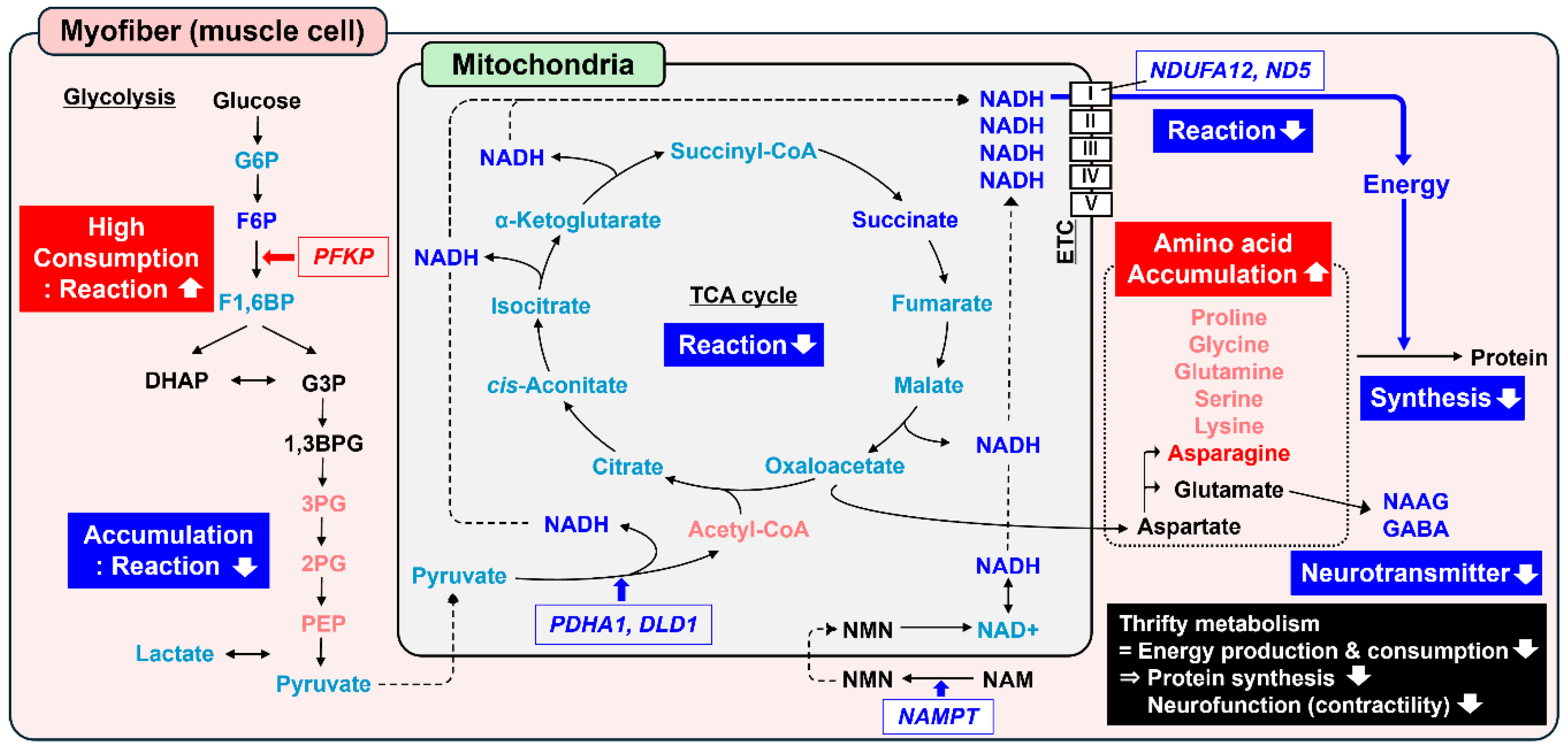

3.2. Metabolomics and Pathway Analysis

3.3. Transcriptomics and Pathway Analysis

3.4. Muscle and Adipocyte Histochemical Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greenwood, P.L.; Bell, A.W. Developmental Programming and Growth of Livestock Tissues for Meat Production. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Food Animal Practice 2019, 35, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Huang, Y.; Das, A.K.; Yang, Q.; Duarte, M.S.; Dodson, M. V.; Zhu, M.J. MEAT SCIENCE AND MUSCLE BIOLOGY SYMPOSIUM: Manipulating Mesenchymal Progenitor Cell Differentiation to Optimize Performance and Carcass Value of Beef Cattle, J Anim Sci 2013, 91, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Cafe, L.M. Consequences of Nutrition and Growth Retardation Early in Life for Growth and Composition of Cattle and Eating Quality of Beef; 2005; Vol. 15;

- Webb, M.J.; Block, J.J.; Funston, R.N.; Underwood, K.R.; Legako, J.F.; Harty, A.A.; Salverson, R.R.; Olson, K.C.; Blair, A.D. Influence of Maternal Protein Restriction in Primiparous Heifers during Mid- and/or Late-Gestation on Meat Quality and Fatty Acid Profile of Progeny. Meat Sci 2019, 152, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbaugh, M.D.; Johnson, S.E.; Shi, T.H.; Gerrard, D.E. Molecular and Biochemical Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Metabolism. J Anim Sci 2022, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet -, M.; Cassar-Malek, I.; Chilliard, Y.; Picard, B. Ontogenesis of Muscle and Adipose Tissues and Their Interactions in Ruminants and Other Species. Animal 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Goto, Y.; Oshima, I.; Muroya, S.; Sano, M.; Saneshima, R.; Nagao, Y.; Kinoshita, A.; et al. Effects of Low and High Levels of Maternal Nutrition Consumed for the Entirety of Gestation on the Development of Muscle, Adipose Tissue, Bone, and the Organs of Wagyu Cattle Fetuses. Animal Science Journal 2021, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroya, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kinoshita, A.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Gotoh, Y.; Oshima, I.; Sano, M.; Roh, S.; Oe, M.; et al. Maternal Undernutrition during Pregnancy Alters Amino Acid Metabolism and Gene Expression Associated with Energy Metabolism and Angiogenesis in Fetal Calf Muscle. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.I.; Wesolowski, S.R.; Gilje, E.A.; Baker, P.R.; Reisz, J.A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Hay, W.W.; Rozance, P.J.; Brown, L.D. Skeletal Muscle Amino Acid Uptake Is Lower and Alanine Production Is Greater in Late Gestation Intrauterine Growth-Restricted Fetal Sheep Hindlimb. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2019, 317, R615–R629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.I.; Vásquez-Hidalgo, M.A.; Li, X.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Grazul-Bilska, A.T.; Swanson, K.C.; Moore, T.E.; Reed, S.A.; Govoni, K.E. The Effects of Maternal Nutrient Restriction during Mid to Late Gestation with Realimentation on Fetal Metabolic Profiles in the Liver, Skeletal Muscle, and Blood in Sheep. Metabolites 2024, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.E.; Jones, A.K.; Pillai, S.M.; Hoffman, M.L.; McFadden, K.K.; Zinn, S.A.; Govoni, K.E.; Reed, S.A. Maternal Restricted- And Overfeeding during Gestation Result in Distinct Lipid and Amino Acid Metabolite Profiles in the Longissimus Muscle of the Offspring. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 448206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, A.; Wishart, D.S.; Fitzsimmons, C. Exploring Biological Impacts of Prenatal Nutrition and Selection for Residual Feed Intake on Beef Cattle Using Omics Technologies: A Review. Front Genet 2021, 12, 720268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, B.; Ghosh, S.; Dysart, M.W.; Kanaan, G.N.; Chu, A.; Blais, A.; Rajamanickam, K.; Tsai, E.C.; Patti, M.E.; Harper, M.E. Low Birth Weight Is Associated with Adiposity, Impaired Skeletal Muscle Energetics and Weight Loss Resistance in Mice. International Journal of Obesity 2015 39:4 2014, 39, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selak, M.A.; Storey, B.T.; Peterside, I.; Simmons, R.A. Impaired Oxidative Phosphorylation in Skeletal Muscle of Intrauterine Growth-Retarded Rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, B.; Harper, M.E. In Utero Undernutrition Programs Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle Metabolism. Front Physiol 2016, 6, 171634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Agriculture and Food Research Organization Japanese Feeding Standard for Beef Cattle; 2008th ed.; Japan Livestock Industry Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2009.

- Phomvisith, O.; Muroya, S.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Oshima, I.; Nishino, D.; Haginouchi, T.; Gotoh, T. Maternal Undernutrition Affects Fetal Thymus DNA Methylation, Gene Expression, and, Thereby, Metabolism and Immunopoiesis in Wagyu (Japanese Black) Cattle. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. In Proceedings of the Bioinformatics; Oxford University Press, September 1 2018; Vol. 34, pp. i884–i890.

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-Based Genome Alignment and Genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-Genotype. Nature Biotechnology 2019 37:8 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie Enables Improved Reconstruction of a Transcriptome from RNA-Seq Reads. Nature Biotechnology 2015 33:3 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation of Gene Lists (2021 Update). Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooke, M.H.; Kaiser, K.K. Muscle Fiber Types: How Many and What Kind? Arch Neurol 1970, 23, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, M.H.; Kaiser, K.K. Three “Myosin Adenosine Triphosphatase” Systems: The Nature of Their PH Lability and Sulfhydryl Dependence. J Histochem Cytochem 1970, 18, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funston, R.N.; Larson, D.M.; Vonnahme, K.A. Effects of Maternal Nutrition on Conceptus Growth and Offspring Performance: Implications for Beef Cattle Production. J Anim Sci 2010, 88, E205–E215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Tong, J.; Zhao, J.; Underwood, K.R.; Zhu, M.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W. Fetal Programming of Skeletal Muscle Development in Ruminant Animals. J Anim Sci 2010, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Freetly, H.C.; Ferrell, C.L.; Jenkins, T.G. Timing of Realimentation of Mature Cows That Were Feed-Restricted during Pregnancy Influences Calf Birth Weights and Growth Rates. J Anim Sci 2000, 78, 2790–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, D.C.; Paulino, M.F.; Rennó, L.N.; Villadiego, F.C.; Ortega, R.M.; Moreno, D.S.; Martins, L.S.; De Almeida, D.M.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Manso, M.R.; et al. Supplementation of Grazing Beef Cows during Gestation as a Strategy to Improve Skeletal Muscle Development of the Offspring. Animal 2017, 11, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Gomez, N.A.; Gao, Y.; Son, J.S.; Chae, S.A.; Zhu, M.J.; Du, M. Stage-Specific Nutritional Management and Developmental Programming to Optimize Meat Production. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2023 14:1 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Aspartic Acid in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2023, Vol. 15, Page 4023 2023, 15, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, M.N.; Butterworth, E.A.; Kilberg, M.S. Asparagine Synthetase: Regulation by Cell Stress and Involvement in Tumor Biology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krall, A.S.; Xu, S.; Graeber, T.G.; Braas, D.; Christofk, H.R. Asparagine Promotes Cancer Cell Proliferation through Use as an Amino Acid Exchange Factor. Nature Communications 2016 7:1 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, C.; Brandt, U.; Hunte, C.; Zickermann, V. Structure and Function of Mitochondrial Complex I. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2016, 1857, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basse, A.L.; Agerholm, M.; Farup, J.; Dalbram, E.; Nielsen, J.; Ørtenblad, N.; Altıntaş, A.; Ehrlich, A.M.; Krag, T.; Bruzzone, S.; et al. Nampt Controls Skeletal Muscle Development by Maintaining Ca2+ Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Integrity. Mol Metab 2021, 53, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlu-Pereira, H.; Silva, M.J.; Florindo, C.; Sequeira, S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Duarte, S.; Rodrigues, A.L.; Janeiro, P.; Oliveira, A.; Gomes, D.; et al. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Deficiency: Updating the Clinical, Metabolic and Mutational Landscapes in a Cohort of Portuguese Patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausina, P.; Da Silva, D.; Majerowicz, D.; Zancan, P.; Sola-Penna, M. Insulin Specifically Regulates Expression of Liver and Muscle Phosphofructokinase Isoforms. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 103, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, I.; Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. Control of Glycolysis through Regulation of PFK1: Old Friends and Recent Additions. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2011, 76, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.J.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Du, M. Effect of Maternal Nutrient Restriction in Sheep on the Development of Fetal Skeletal Muscle. Biol Reprod 2004, 71, 1968–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, A.L.; Antolic, A.T.; Kelly, A.C.; Davis, M.A.; Camacho, L.E.; Doubleday, K.; Anderson, M.J.; Langlais, P.R.; Lynch, R.M.; Limesand, S.W. Lower Oxygen Consumption and Complex I Activity in Mitochondria Isolated from Skeletal Muscle of Fetal Sheep with Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2020, 319, E67–E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Kelly, A.C.; Luna-Ramirez, R.I.; Bidwell, C.A.; Anderson, M.J.; Limesand, S.W. Decreased Pyruvate but Not Fatty Acid Driven Mitochondrial Respiration in Skeletal Muscle of Growth Restricted Fetal Sheep. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.C.; Polizel, G.H.G.; Cracco, R.C.; Cançado, F.A.C.Q.; Baldin, G.C.; Poleti, M.D.; Ferraz, J.B.S.; Santana, M.H. de A. Metabolomics Changes in Meat and Subcutaneous Fat of Male Cattle Submitted to Fetal Programming. Metabolites 2024, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, J.H.; Bzdega, T.; Wroblewska, B. N-Acetylaspartylglutamate. J Neurochem 2000, 75, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pette, D.; Staron, R.S. Transitions of Muscle Fiber Phenotypic Profiles. Histochem Cell Biol 2001, 115, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, E.; Eixarch, E.; Illa, M.; Arbat-Plana, A.; González-Tendero, A.; Hogberg, H.T.; Zhao, L.; Hartung, T.; Gratacos, E. Metabolomics Reveals Metabolic Alterations by Intrauterine Growth Restriction in the Fetal Rabbit Brain. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerboom, C.; Wierenga, C.J. The Postnatal GABA Shift: A Developmental Perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 124, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarneh, S.K.; Silva, S.L.; Gerrard, D.E. New Insights in Muscle Biology That Alter Meat Quality. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2021, 9, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Slepetis, R.M.; Bell, A.W.; Hermanson, J.W. Intrauterine Growth Retardation Is Associated with Reduced Cell Cycle Activity, but Not Myofibre Number, in Ovine Fetal Muscle. Reprod Fertil Dev 1999, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, J.; Albrecht, E.; Fiedler, I.; Teuscher, F.; Papstein, H.J.; Ender, K. Growth- and Breed-Related Changes of Muscle Fiber Characteristics in Cattle. J Anim Sci 2000, 78, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.C.; Du, M.; Nascimento, K.B.; Galvão, M.C.; Meneses, J.A.M.; Schultz, E.B.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Duarte, M. de S. Skeletal Muscle Development in Postnatal Beef Cattle Resulting from Maternal Protein Restriction during Mid-Gestation. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, A.J.; Brameld, J.M.; Parr, T.; Buttery, P.J. The Effect of Maternal Undernutrition before Muscle Differentiation on the Muscle Fiber Development of the Newborn Lamb, J Anim Sci 2005, 83, 2564–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.J.; Ford, S.P.; Means, W.J.; Hess, B.W.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Du, M. Maternal Nutrient Restriction Affects Properties of Skeletal Muscle in Offspring. J Physiol 2006, 575, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, T.I.R.C.; Copping, K.J.; Han, X.; Clayton, E.H.; Meyer, R.J.; Rodgers, R.J.; McMillen, I.C.; Perry, V.E.A.; Geesink, G. The Influence of Peri-Conception and First Trimester Dietary Restriction of Protein in Cattle on Meat Quality Traits of Entire Male Progeny. Meat Sci 2016, 121, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Cafe, L.M. Prenatal and Pre-Weaning Growth and Nutrition of Cattle: Long-Term Consequences for Beef Production. Animal 2007, 1, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh-Gavahan, L.; Hosseinkhani, A.; Hamidian, G.; Jarolmasjed, S.; Yousefi-Tabrizi, R. Restricted Maternal Nutrition and Supplementation of Propylene Glycol, Monensin Sodium and Rumen-Protected Choline Chloride during Late Pregnancy Does Not Affect Muscle Fibre Characteristics of Offspring. Vet Med Sci 2023, 9, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tygesen, M.P.; Harrison, A.P.; Therkildsen, M. The Effect of Maternal Nutrient Restriction during Late Gestation on Muscle, Bone and Meat Parameters in Five Month Old Lambs. Livest Sci 2007, 110, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uezumi, A.; Ito, T.; Morikawa, D.; Shimizu, N.; Yoneda, T.; Segawa, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ogawa, R.; Matev, M.M.; Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; et al. Fibrosis and Adipogenesis Originate from a Common Mesenchymal Progenitor in Skeletal Muscle. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 3654–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Wang, B.; Fu, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, M.J. Fetal Programming in Meat Production. Meat Sci 2015, 109, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.; Heasman, L.; Juniper, D.T.; Symonds, M.E. Maternal Nutrition in Early-Mid Gestation and Placental Size in Sheep. British Journal of Nutrition 1998, 79, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonnahme, K.A.; Hess, B.W.; Hansen, T.R.; McCormick, R.J.; Rule, D.C.; Moss, G.E.; Murdoch, W.J.; Nijland, M.J.; Skinner, D.C.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; et al. Maternal Undernutrition from Early- to Mid-Gestation Leads to Growth Retardation, Cardiac Ventricular Hypertrophy, and Increased Liver Weight in the Fetal Sheep. Biol Reprod 2003, 69, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.C.; Gionbelli, M.P.; Duarte, M. de S. Fetal Programming in Ruminant Animals: Understanding the Skeletal Muscle Development to Improve Meat Quality. Animal Frontiers 2021, 11, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment1 | |||||

| Items | CNT | NR | SEM | P-value | |

| Nutrient intake, kg | |||||

| Milk replacer | |||||

| CP2 | 16.6 | 16.3 | 0.7 | 0.73 | |

| TDN3 | 64.0 | 63.0 | 2.8 | 0.73 | |

| Total mixed ration | |||||

| 0–120 d | |||||

| CP2 | 31.9 | 34.3 | 2.1 | 0.31 | |

| TDN3 | 137.5 | 147.9 | 8.9 | 0.31 | |

| 121–300 d | |||||

| CP2 | 213.6 | 214.6 | 7.0 | 0.89 | |

| TDN3 | 858.4 | 865.7 | 28.6 | 0.79 | |

| Body weight, kg | |||||

| 0 d | 36.1 | 32.4 | 1.2 | 0.03 | |

| 30 d | 63.2 | 55.9 | 1.2 | < | 0.01 |

| 60 d | 82.3 | 78.8 | 2.6 | 0.31 | |

| 120 d | 140.0 | 139.2 | 5.0 | 0.90 | |

| 180 d | 198.4 | 205.9 | 7.0 | 0.34 | |

| 240 d | 249.3 | 278.3 | 11.1 | 0.08 | |

| 300 d | 311.1 | 328.8 | 12.5 | 0.29 | |

| ADG4, kg/d | |||||

| 0–30 d | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| 31–60 d | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.35 | |

| 61–120 d | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.39 | |

| 121–180 d | 0.97 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| 181–240 d | 0.85 | 1.21 | 0.16 | 0.08 | |

| 241–300 d | 1.03 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.39 | |

| CPCR6, kg CP intake/kg BW gain | |||||

| 0–120 d | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.69 | |

| 121–300 d | 1.26 | 1.11 | 0.07 | 0.15 | |

| TDNCR5, kg TDN intake/kg BW gain | |||||

| 0–120 d | 1.94 | 1.99 | 0.08 | 0.66 | |

| 121–300 d | 5.07 | 4.47 | 0.31 | 0.17 | |

| Treatment2 | |||||

| Compound1 | CNT | NR | SEM | P-value | |

| NADH | 100.0 | 22.2 | 5.7 | < | 0.01 |

| Pyroglutamine | 100.0 | 145.1 | 8.0 | 0.01 | |

| 2-Deoxyribonic acid | 100.0 | 72.6 | 4.6 | 0.01 | |

| N-Acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate | 100.0 | 33.2 | 12.6 | 0.01 | |

| N6,N6-Dimethyllysine | 100.0 | 141.3 | 11.0 | 0.03 | |

| 11-Aminoundecanoic acid | 100.0 | 140.7 | 11.2 | 0.03 | |

| 3’,5’-ADP | 100.0 | 203.4 | 27.6 | 0.03 | |

| myo-Inositol 2-phosphate | 100.0 | 68.9 | 8.9 | 0.04 | |

| 3-Methylcytidine | 100.0 | 55.2 | 12.0 | 0.04 | |

| Asparagine | 100.0 | 141.4 | 13.4 | 0.05 | |

| Allantoic acid | 100.0 | 57.8 | 13.2 | 0.05 | |

| Tyrosine methyl ester | 100.0 | 69.4 | 9.5 | 0.06 | |

| Taurine | 100.0 | 140.3 | 14.3 | 0.06 | |

| N-Acetylaspartylglutamate | 100.0 | 55.3 | 16.4 | 0.07 | |

| Fructose 6-phosphate | 100.0 | 62.6 | 12.0 | 0.07 | |

| Succinate | 100.0 | 60.5 | 13.7 | 0.07 | |

| GABA | 100.0 | 72.4 | 11.2 | 0.08 | |

| Methylguanidine | 100.0 | 139.0 | 16.1 | 0.09 | |

| 2-Amino-2-methyl-1-propanol | 100.0 | 120.7 | 8.9 | 0.10 | |

| Glycerophosphorylethanolamine | 100.0 | 171.5 | 30.4 | 0.10 | |

| Glucosaminic acid | 100.0 | 63.2 | 15.2 | 0.10 | |

| Metabolites2 | ||||||

| Pathway1 | P-value | FDR | Increased in NR LM | Decreased in NR LM | ||

| Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | < | 0.01 | < | 0.01 | Asparagine | Succinate, N-Acetylaspartylglutamate, GABA |

| Butanoate metabolism | < | 0.01 | 0.15 | Succinate, GABA | ||

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 0.03 | 0.76 | Fructose 6-phosphate, N-Acetyl-glucosamine 1-phosphate | |||

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 0.05 | 1.00 | Taurine | |||

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.11 | 1.00 | Fructose 6-phosphate | |||

| TCA cycle | 0.12 | 1.00 | Succinate | |||

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | 0.12 | 1.00 | Fructose 6-phosphate | |||

| Ether lipid metabolism | 0.12 | 1.00 | Glycerylphosphorylethanolamine | |||

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 0.12 | 1.00 | 3¢,5¢-ADP | |||

| Propanoate metabolism | 0.13 | 1.00 | Succinate | |||

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 0.14 | 1.00 | Fructose 6-phosphate | |||

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 0.16 | 1.00 | Fructose 6-phosphate | |||

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 0.21 | 1.00 | GABA | |||

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.21 | 1.00 | Glycerylphosphorylethanolamine | |||

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 0.26 | 1.00 | Taurine | |||

| Purine metabolism | 0.37 | 1.00 | Allantoic acid | |||

| Items1 | Hits/total genes | Raw P-value | FDR | |||

| Pathways enriched with upregulated DEG2 | ||||||

| bta04820 | Cytoskeleton in muscle cells | 15 / 232 | < | 0.01 | < | 0.01 |

| bta05171 | Coronavirus disease - COVID-19 | 16 / 317 | < | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| bta03010 | Ribosome | 11 / 202 | < | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| bta04512 | ECM–receptor interaction | 7 / 89 | < | 0.01 | 0.14 | |

| bta05169 | Epstein–Barr virus infection | 11 / 236 | < | 0.01 | 0.15 | |

| bta05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 7 / 105 | 0.01 | 0.20 | ||

| bta05164 | Influenza A | 9 / 196 | 0.01 | 0.34 | ||

| bta04145 | Phagosome | 8 / 166 | 0.01 | 0.35 | ||

| bta04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 6 / 93 | 0.01 | 0.35 | ||

| bta05133 | Pertussis | 5 / 78 | 0.03 | 0.71 | ||

| bta04510 | Focal adhesion | 8 / 204 | 0.04 | 0.72 | ||

| bta05162 | Measles | 7 / 162 | 0.04 | 0.72 | ||

| bta05165 | Human papillomavirus infection | 11 / 354 | 0.05 | 0.77 | ||

| bta04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 6 / 129 | 0.05 | 0.77 | ||

| bta05132 | Salmonella infection | 9 / 265 | 0.05 | 0.77 | ||

| bta05323 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 / 104 | 0.08 | 0.99 | ||

| bta04151 | PI3K–Akt signaling pathway | 11 / 392 | 0.08 | 0.99 | ||

| bta04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 7 / 198 | 0.08 | 0.99 | ||

| bta05020 | Prion disease | 9 / 303 | 0.10 | 0.99 | ||

| Pathways enriched with downregulated DEG3 | ||||||

| bta01100 | Metabolic pathways | 27 / 1642 | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04931 | Insulin resistance | 5 / 110 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| bta00010 | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 4 / 64 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04152 | AMPK signaling pathway | 5 / 126 | 0.04 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04144 | Endocytosis | 7 / 249 | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||

| bta00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 3 / 34 | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||

| bta00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 3 / 46 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04922 | Glucagon signaling pathway | 4 / 103 | 0.09 | 1.00 | ||

| Pathways enriched with upregulated and downregulated DEG4 | ||||||

| bta04820 | Cytoskeleton in muscle cells | 18 / 232 | < | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| bta05171 | Coronavirus disease - COVID-19 | 18 / 317 | < | 0.01 | 0.52 | |

| bta04512 | ECM–receptor interaction | 8 / 89 | 0.01 | 0.59 | ||

| bta05169 | Epstein–Barr virus infection | 14 / 236 | 0.01 | 0.59 | ||

| bta05132 | Salmonella infection | 14 / 265 | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||

| bta00010 | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 6 / 64 | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04144 | Endocytosis | 13 / 249 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 11 / 198 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| bta03010 | Ribosome | 11 / 202 | 0.04 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04152 | AMPK signaling pathway | 8 / 126 | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||

| bta05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 7 / 105 | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| bta00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 4 / 34 | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| bta05162 | Measles | 9 / 162 | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| bta04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 6 / 93 | 0.09 | 1.00 | ||

| bta05020 | Prion disease | 13 / 303 | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||

| Treatment | ||||

| Items1 | CNT | NR | SEM | P-value |

| Myofiber diameter at 300 d, µm | ||||

| Type I | 37.5 | 41.1 | 3.0 | 0.32 |

| Type IIA | 49.9 | 54.3 | 5.5 | 0.48 |

| Type IIX | 64.7 | 64.5 | 4.3 | 0.95 |

| Myofiber type, % | ||||

| 75 d | ||||

| Type I | 24.7 | 23.8 | 2.2 | 0.74 |

| Type IIA | 26.0 | 26.7 | 1.2 | 0.67 |

| Type IIX | 49.2 | 49.5 | 2.9 | 0.94 |

| 180 d | ||||

| Type I | 23.3 | 21.2 | 1.6 | 0.33 |

| Type IIA | 24.8 | 27.9 | 2.1 | 0.31 |

| Type IIX | 51.9 | 50.9 | 1.9 | 0.67 |

| 300 d | ||||

| Type I | 21.6 | 29.0 | 2.7 | 0.07 |

| Type IIA | 30.2 | 24.1 | 1.3 | 0.02 |

| Type IIX | 48.2 | 46.9 | 1.8 | 0.62 |

| Adipocyte size at 300 d, μm2 | ||||

| Cross-sectional area | 2365.0 | 1947.4 | 306.3 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).