1. Introduction

Cancer is a broad term encompassing a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled growth and proliferation of abnormal cells, resulting from genetic or epigenetic alterations that disrupt cell cycle regulation. These malignant cells can invade adjacent tissues and organs and, in advanced stages, metastasize to distant sites through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. BC originates in mammary tissues and primarily affects the lobules, responsible for milk production, the ducts that transport milk to the nipple, or the connective tissue that provides structural support. Most cases arise in the ducts or lobules and have the potential to spread via blood and lymphatic vessels. According to the Global Cancer Observatory, BC accounted for 2,296,840 cases worldwide in 2022, representing 11.5% of all cancer diagnoses. It was also the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women, with 666,103 deaths (15.4%). These statistics underscore its significant global burden [

1,

2,

3].

In 2000, Perou et al. proposed a molecular classification of BC based on the expression of three key receptors critical for conventional treatment efficacy: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). This classification defines four molecular subtypes with distinct therapeutic responses: Luminal A (ER+ and PR+/-), Luminal B (ER+, PR+/- and HER2+), HER2-enriched (HER2+), and TN (ER-, PR- and HER2-) [

4]. Among these, TN is clinically recognized as the most aggressive subtype due to its poor response to conventional therapies, leading to lower overall survival and disease-free survival rates [

4,

5,

6].

Natural products have played a fundamental role in traditional medicine throughout history. Since the World Health Organization endorsed the use of complementary therapies in 2004, interest in herbal medicine and the development of phytochemical-based anticancer agents has grown significantly. Bioactive compounds derived from plants have gained recognition for their potential in cancer treatment [

7,

8,

9]. Cv is a monoterpenoid phenol synthesized via the mevalonate pathway from acetyl-coenzyme A, which has attracted attention for its anticancer properties. It one of the predominant compounds in oregano extracts [

10,

11,

12].

Lippia graveolens, commonly known as Mexican oregano, is used as condiment of many traditional Mexican dishes as well as raw material to produce cosmetics, drugs, and liquors. Oregano variants have been reported to have antioxidant potential and anti-inflammatory activity; these properties are attributed to their phytochemical profile, mainly to its phenolic compounds [13, 14].

However, limited evidence exists regarding the composition, antioxidant capacity, and anticancer potential of aqueous extracts from oregano variants, leaving a gap in knowledge about the bioactivity of MoI. Therefore, the aims of this study was, first, to characterize an endemic species of Mexican oregano (Lippia graveolens) from Totatiche, Jalisco, Mexico, as well as to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of the MoI prepared with this plant sample with different tests (ABTS, DPPH, total phenols, total flavonoids and FRAP) and second, to compare the anticancer effects of Cv and the MoI at the level of cell metabolism and cytotoxicity against BC cell lines, luminal A (MCF-7), HER2-enriched (HCC-1954) and TN (MDA-MB-231), also, these tests were performed on HaCaT cells (immortalized keratinocytes that do not express oncogenes) to evaluate the effects of both treatments on non-cancerous cells.

3. Discussion

Both oregano extracts and Cv have been extensively studied due to their diverse biological activities, which postulates them as potential therapeutic agents for the management of different diseases, including cancer. Among their properties, their antioxidant activity stands out, as well as their antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects, characteristics that make them promising options for oncological treatment [

16,

17,

18].

The bromatological analysis performed on the plant sample used in this study can be compared with the data reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for dried oregano. Compared to this reference, our sample presented 12.3 % less moisture, 15.3 % less ash, 24 % less protein, 2.3 % less lipids, but an increase of 51.9 % in available carbohydrates and 70.1 % in total sugars, with a reduction of 9.1 % in dietary fiber. These differences can be attributed to several factors, such as soil type and fertility, pH, growing conditions (temperature, light, humidity), irrigation regime, fertilization, pest control, harvest timing and drying methods. Each of these factors significantly influences the chemical composition of the plant sample and, consequently, its biological activity [

19].

Regarding the antioxidant capacity

of L. graveolens, it has been demonstrated that both the plant matrix and its extracts are rich in antioxidant compounds, which confers a high capacity to neutralize free radicals [17, 20]. The results obtained in the present study support this claim, since it was observed that MoI exhibited potent total antioxidant activity in ABTS and DPPH radical neutralization assays, as well as in the quantification of total phenols, total flavonoids and FRAP. Similar results have been reported in the literature. Mahomoodally et al. (2018) evaluated the antioxidant capacity of aqueous and methanolic extracts of

Origanum onites (Greek oregano), finding that the aqueous extract presented a higher antioxidant capacity compared to the methanolic one, which was attributed to a higher concentration of phenolic compounds [

21]. In contrast, Simirgiotis et al. (2020) analyzed a lipid extract of

Origanum vulgare (oregano species native to the mediterranean), finding a lower amount of phenolic compounds and, consequently, a lower antioxidant capacity against ABTS and DPPH radicals [

22]. Similarly, Kogiannou et al. (2013) compared the antioxidant capacity of 6 herbal infusions of plants originating from Greece, including a species of oregano, where they observed that this infusion had the best antioxidant capacity in all the techniques they used (total phenols, total flavonoids, DPPH and FRAP), compared to other plants with recognized antioxidant capacity such as chalk marjoram, pink savory, mountain tea, pennyroyal and chamomile [

23]. These findings reinforce the evidence that extracts from oregano variants, especially in infusion form, have a high antioxidant potential. The antioxidant potential of MoI could be related to its anticancer activity, since there is a correlation between the amount and type of phenolic compounds and their cytotoxicity. It has been proposed that certain functional groups, such as carbonyls and free hydroxyls, facilitate the formation of ortho-diphenolic radicals (two hydroxyl groups attached to a benzene ring in adjacent positions), which could chelate transition metals involved in redox processes, thus affecting the viability of cancer cells [24, 25]. This suggests the need to continue investigating their role in the management of chronic degenerative diseases, such as BC.

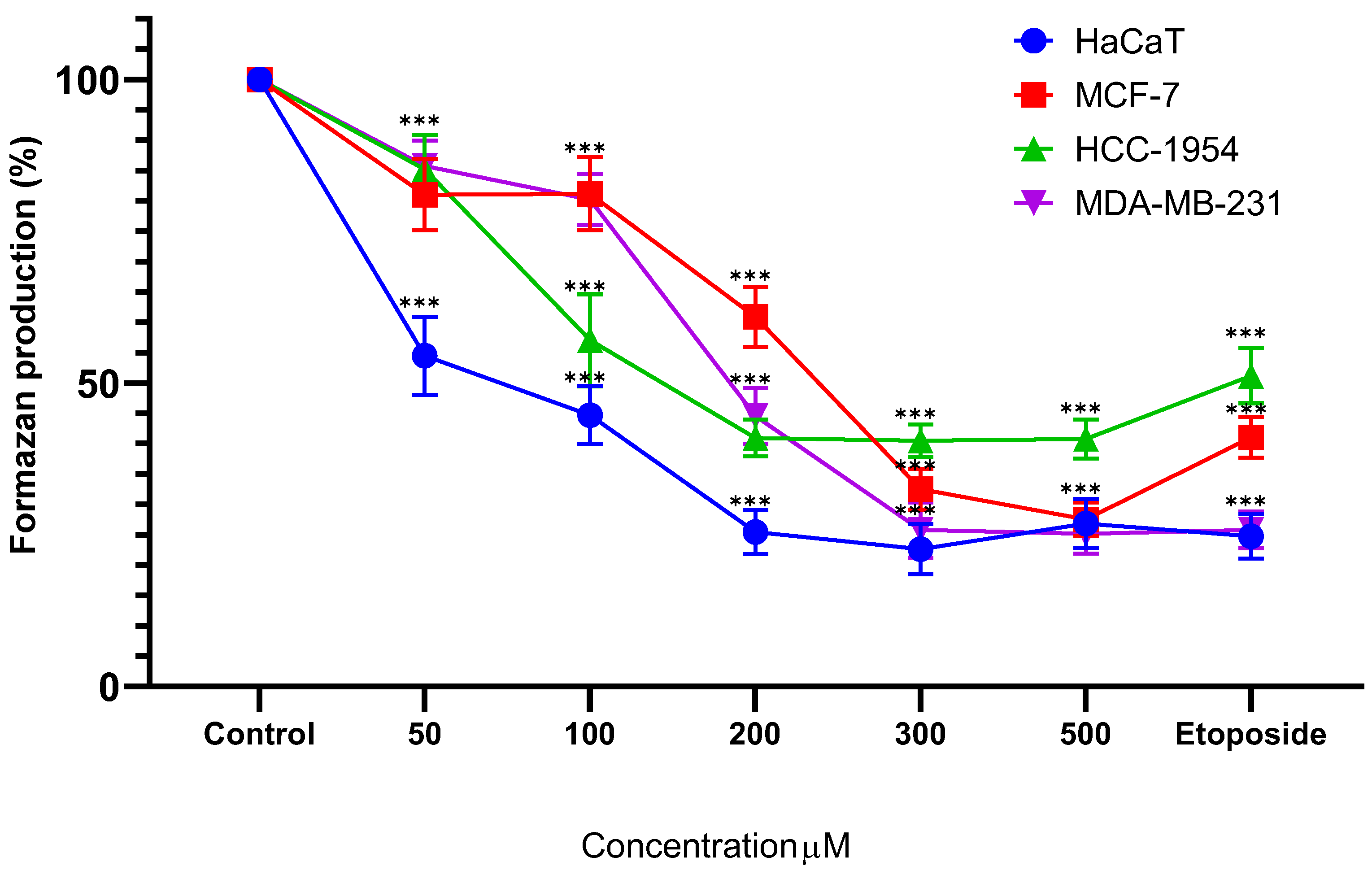

On the other hand, treatment with Cv showed a differential impact on the metabolic activity of the different cell lines used in this study. It was observed that the MDA-MB-231 cell line (TN BC) was more susceptible to treatment compared to the HCC-1954 (HER2+) and MCF-7 (luminal A) lines, with IC50 values of 121 µM, 123 µM and 211 µM, respectively. However, the control cell line (HaCaT) presented higher susceptibility to Cv, with an IC50 of 91 µM, highlighting the importance of including non-cancer cell models to assess treatment specificity. These findings are consistent with previous studies. Elshafie et al. (2017) evaluated the metabolic activity of a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2) treated with the

Origanum vulgare lead compounds (Cv, thymol, and citral). To evaluate this activity, they performed MTT assays and found that Cv was the compound with the highest potential to reduce metabolic activity, with an IC50 of 48 mg/L. Furthermore, they observed that the metabolic activity of the control line (HEK293; non-cancerous human kidney cells) was considerably higher (38%) than that exhibited by HepG2 cells (12%). These findings support the idea that Cv, besides being the most abundant compound in oregano variants, also exhibits a remarkable cytotoxic potential against cancer cells, even becoming the most effective compound among those present in the plant against the HepG2 line [

16]. Both previous research and the results of this study agree that the ability of Cv to decrease cell viability in cancer cells is significant in both hepatocellular carcinoma cells and aggressive BC subtypes. Further support for the cytotoxic potential of Cv against cancer cells was provided by Elbe et al. in 2020, who subjected ovarian cancer cells (Skov-3) to different doses of thymol and Cv. The results, analyzed by MTT assays, revealed that both compounds exhibit a potent effect and that this occurs in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 316.08 µM for thymol and 322.50 µM for Cv after 24 hours of treatment. Although the authors reported that thymol showed a higher cytotoxic potential than Cv in this cell line, both compounds are considered interesting options for the development of adjuvant cancer treatments [

26]. These results contrast with those presented by Elshafie et al. in 2017, who found that Cv exhibited greater cytotoxic potential compared to other major

Origanum vulgare compounds, including thymol [

16]. The differences may be attributed to the different cell lines used in each study. Despite this, Cv demonstrated significantly high cytotoxic potential, supported by the results presented in the present study, which evidences its efficacy in reducing the metabolic activity of different cancer cell lines, including BC, and consequently supports the importance of continuing its study to assess the possibility of its use in the management of neoplastic diseases.

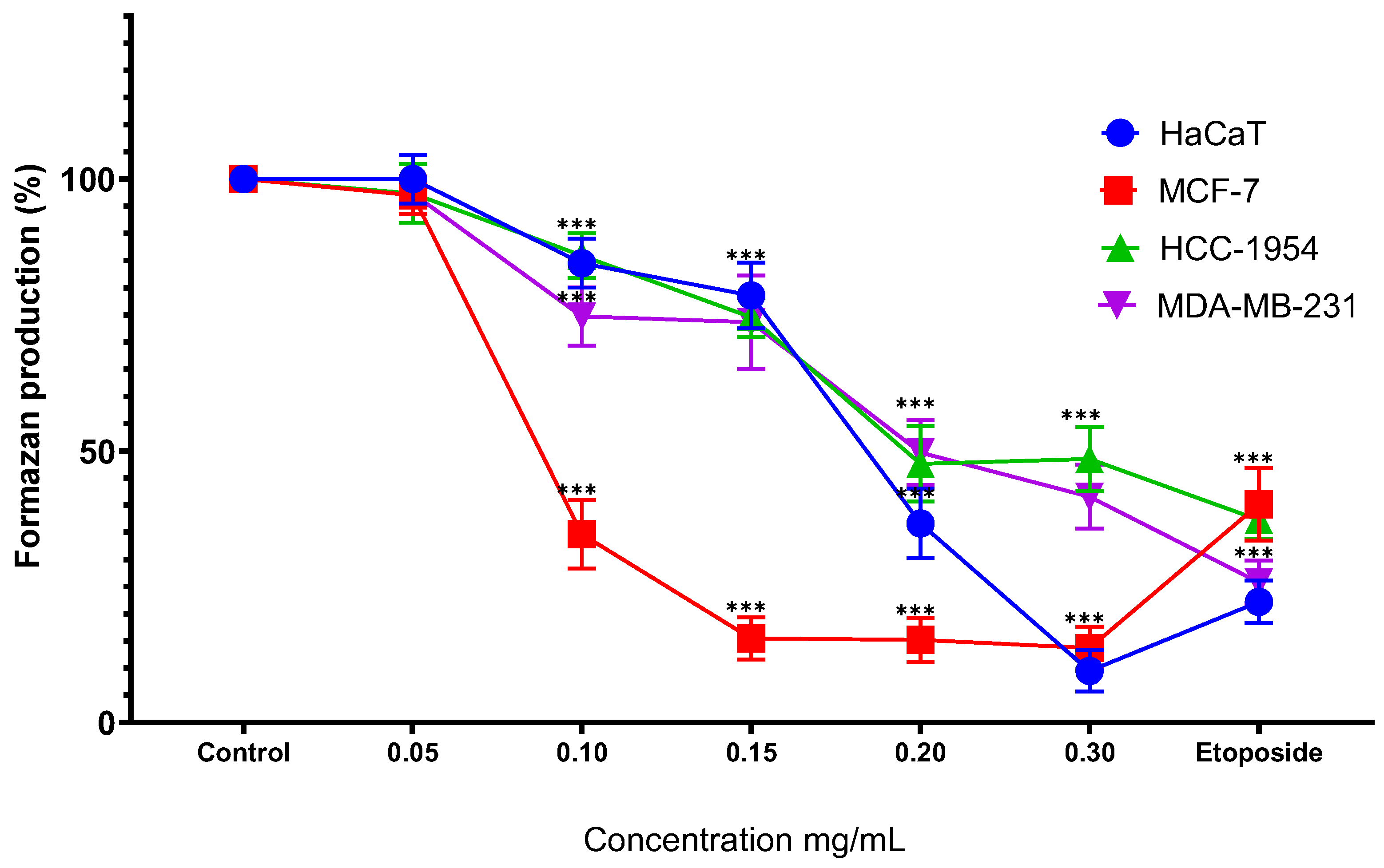

Regarding MoI, it was found that as the aggressiveness of the molecular subtype of the cell line increases, so does the dose required to reach IC-50. Furthermore, the control cell line (HaCaT) required the same infusion dose as the triple-negative BC cells, suggesting that MoI has a less aggressive effect on non-cancerous cells compared to the isolated Cv compound. These findings are consistent with that reported by Tuncer et al. in 2013. In their study, they treated three BC cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-468 and MDA-MB-231), using an aqueous extract of

Origanum acutidens (Turkish oregano) and assessed the impact on metabolic activity using MTT assays as in our research, treatment efficacy is presented in a dose-dependent manner and together, these reports and our results support that oregano extracts represents a good alternative treatment against BC cell lines, including the most aggressive subtypes [

27]. Furthermore, in 2018, Makrane et al. investigated the effect of infusion of a Moroccan species of oregano in HT-29 colon cancer cells and MDA-MB-231 BC cells and evaluated its impact on metabolic activity by WST1 assay, finding that the treatment reduced metabolic activity in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines. They observed that triple-negative BC cells were more susceptible to treatment, with an IC50 ranging from 30.90 to 87.09 µg/mL, while in HT-29 cells this range ranged from 50.11 to 158.48 µg/mL [

28]. These results are relevant to our study, as we also employed an infusion as a treatment in a TN BC cell line, providing a close reference to contrast our results. Based on this study and our findings, we can conclude that oregano extracts, including MoI, significantly reduce the metabolic activity of BC cell lines, even in the TN subtype, and that this effect occurs in a dose-dependent manner.

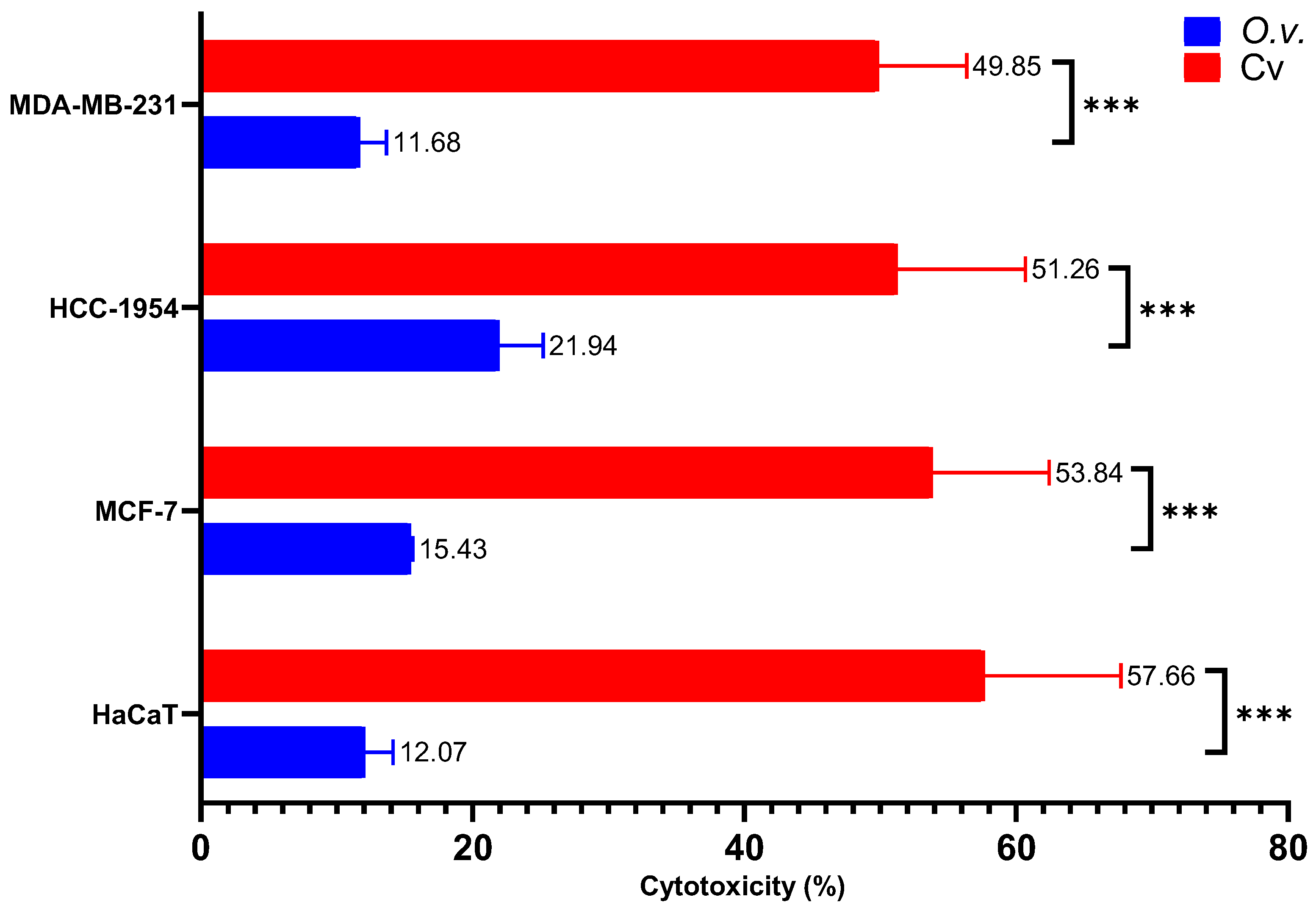

The results obtained in this study indicate that Cv exhibits greater cytotoxicity compared to MoI (~50 % and ~15 %, respectively), which suggests that while infusion may reduce cellular metabolism, the isolated Cv compound exhibits greater cytotoxicity. Despite the limited availability of studies on oregano cytotoxicity, the existing evidence concurs that its extracts, regardless of extraction method, possess activity against BC cells, including the most aggressive subtypes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical and reagents

Cv ≥98% purity (499-75-2) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, D8418), was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, 11966025) Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI-1640, 11875119), phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10010023), fetal bovine serum (FBS,16140071), penicillin/ streptomycin (15140122), MTT (6494), and trypsin (25300054) were purchased from Thermo Fisher ScientificTM (Waltham, MA, USA). All solvents and chemicals were of an analytical grade.

4.2. Cell lines and culture conditions

Cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Human keratinocyte transformed and immortalized HaCaT cells and TN BC MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640, luminal A MCF-7 and HER2 HCC-1954 BC cell lines were maintained in DMEM, both mediums were supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% of penicillin/ streptomycin. The cell cultures were kept in incubation under physiological conditions (37 °C, 95% humidity and 5% CO2 saturation).

4.3. Plant material

The oregano used in this study is an endemic species from the region of Totatiche, Jalisco, Mexico.

4.4. Bromatological analysis of L. graveolens

Bromatological analyses were performed with the dried leaves of L. graveolens. The analyses performed were humidity, ash, proteins by the micro-Kjeldahl method, direct reducing sugars, total reducing sugars, ethereal extraction by Soxhlet and dietary fiber.

4.5. MoI preparation

230 mg of dry leaves were ground to a fine powder using a porcelain mortar. This powder was suspended in 10mL of sterile boiling water for 10 minutes, and the resulting infusion was filtered with a 0.22 µM sterile filter into a laminar flow hood.

4.6. Preparation of Cv solution

Cv isolate was mixed with DMSO (<0.05% final concentration) and culture medium to obtain a 1000µM solution.

4.7. Antioxidant activity protocols (DPPH and ABTS) in MoI

In brief, a total of 225 μL of ABTS (2,2’-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) solution was placed in each microplate well, and an initial reading was taken at 734 nm, which served as the initial absorbance datum. Subsequently, 75 μL of 1:1000 diluted MoI (with deionized water) was added, and the microplate was incubated for 5 minutes with stirring. After which, the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. A Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) standard curve was performed to express the results as mMEQ Trolox per gram of dried sample.

For the DPPH (1,1diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) method, 150 µL of the 1:1000 diluted MoI (with deionized water) was placed in a 96-well plate, and 150µL of 1010 µM methanolic solution of DPPH was added and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. A Trolox standard curve was performed to express the results as mMEQ Trolox per gram of dried sample. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm (BioTek-SynergyHTX, Winooski, VE, USA).

4.8. Determination of total phenolic content in MoI

This was performed using the Folin–Ciocalteu reaction. Total phenolic content of MoI was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method. 200 μL of distilled water were mixed with 250 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu solution (1 N) and 50 μL of MoI (1:10) or different concentrations (20–180 g/mL) of gallic acid (used as standard) were tested. Further, after incubation for 5 minutes at room temperature, 500 µL of sodium carbonate solution (15% Na2CO3) was added and the solution was mixed thoroughly and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark at 45ºC. 200 μL of each reaction were measured at 760 nm (BioTek-SynergyHTX, Winooski, VE, USA). All results were expressed as milligram of Gallic Acid Equivalent per gram of dried sample (mgGAE/g).

4.9. Determination of total flavonoids in MoI

Briefly, 100 µL of MoI was mixed with 200 µL of 1M potassium acetate, 200 µL of aluminum chloride solution (10% AlCl₃) and 500 µL of 80% ethanol. The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated for 40 minutes at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 415 nm (BioTek-SynergyHTX, Winooski, VE, USA). A calibration curve was performed with quercetin as standard. The result was expressed as mg Eq quercetin/g dry weight of oregano.

4.10. FRAP in MoI

40 μL of MoI or standard was mixed with 250 μL of FRAP reagent (25 mL 300 mM sodium acetate, 1.6% acetic acid; 2.5 mL TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tri (2-pyridyl)-s-triazine), 40 mM hydrochloric acid). 240 μL of distilled water was used as blank and FeSO₄ as standard for the calibration curve. The absorbance was determined at 593 nm (BioTek-SynergyHTX, Winooski, VE, USA). Results were expressed as millimoles of Fe2+.

To prepare the MoI, 1 g of dried oregano leaves was heated in 100 mL of distilled water at 60°C for 10 minutes with continuous stirring. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. The supernatant was carefully poured through Whatman No. 1 filter paper into a clean glass container to remove any solid residues. The filtered extract was stored at 4°C for further use.

To obtain a concentrated extract, the filtered solution was transferred into a round-bottom flask connected to a rotary evaporator. The flask was immersed in a 40–50°C water bath, and a gradual vacuum was applied. The rotation speed was set to approximately 100 rpm to enhance evaporation. Once most of the solvent had evaporated, the concentrated extract was collected and further dried in a desiccator until a solid or semi-solid form was obtained. The final dried extract was stored in a sealed container at 4°C for analysis.

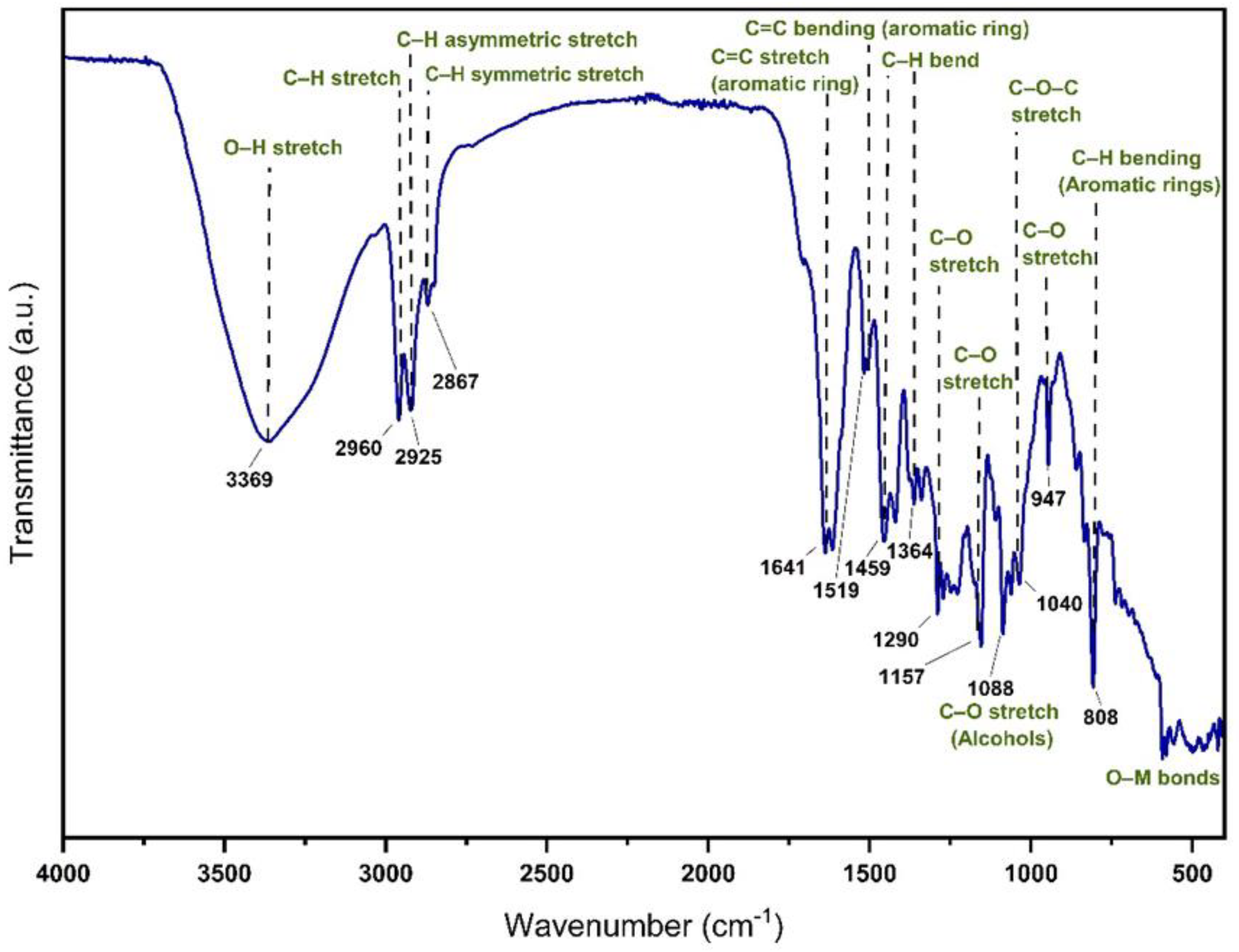

4.11. FTIR Measurement

The MoI was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. The supernatant was carefully filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper into a clean glass container to remove any solid residues. To obtain a concentrated extract, the filtered solution was transferred to a round-bottom flask connected to a rotary evaporator. The flask was immersed in a water bath maintained at 40–50°C, and a gradual vacuum was applied. The rotation speed was set to approximately 100 rpm to facilitate solvent evaporation. Once most of the solvent had evaporated, the concentrated extract was collected and further dried in a desiccator until a solid or semi-solid form was achieved. The final dried extract was stored in a sealed container at 4°C for analysis. The MoI was analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy within the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range, utilizing a PerkinElmer 400 FTIR spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA). A background spectrum was recorded prior to measurement to eliminate environmental interference. For analysis, a small amount (1–2 mg) of the extract was placed on the sample holder of the ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) crystal, forming a thin film. The instrument performed 32 scans, which were averaged to generate the final spectrum. The results were displayed as Transmittance vs. Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) for functional group identification.

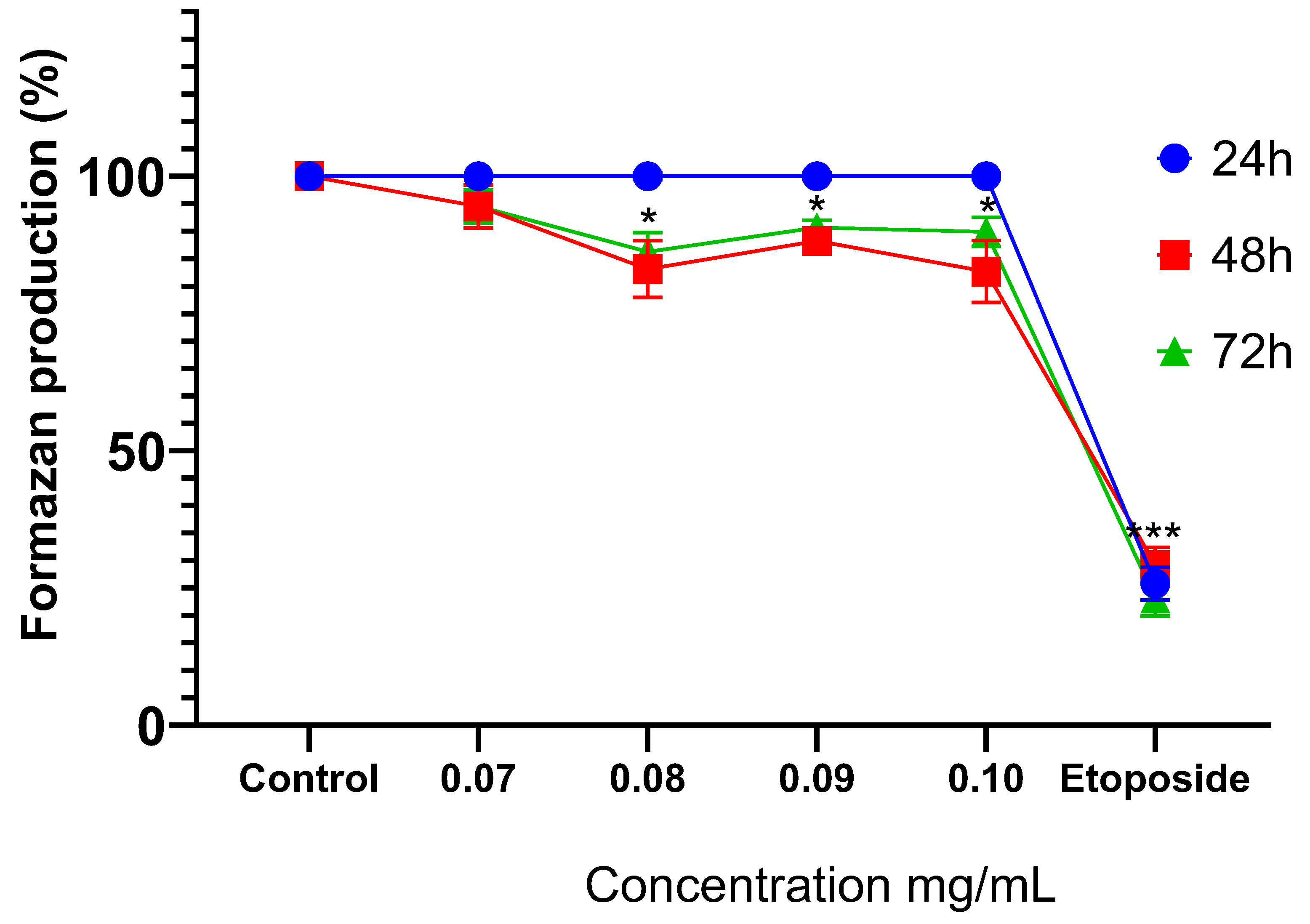

4.12. MoI time response curve

Since there are no previous reports on the use of MoI on cancer cells, we evaluated the effect at the metabolic level of different doses of the infusion for 24, 48 and 72 hours in MDMA-MB-231 cells to establish an exposure time for further testing, because for Cv treatment we started from the background of Arunasree et al. in MDA-MB-231 cells [

16]. Briefly, 1.5 × 10⁴ cells/well were seeded in 96 well-plates, after 24 hours of incubation MoI was added in different concentrations, untreated groups received culture medium, and cells were incubated for the corresponding time (24, 48 or 72 hours). Next, MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added, and cells were incubated for 4 hours to allow formazan production, these crystals were dissolved using a solution prepared with sodium dodecyl sulfate (Thermo Fisher, 28312) and dimethylformamide (Sigma-Aldrich, 227056) at pH 4.6, followed by a final incubation of 18–24 hours. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm (BioTek-800TS, Winooski, VE, USA), with untreated cells considered as 100% formazan production.

4.13. Evaluation of cell metabolism (MTT assay)

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 10⁴ cells/well. After 24 hours of incubation increasing concentrations of MoI or Cv solution were added, while untreated groups received culture medium. Cells were incubated 24 hours with Cv and 48 hours with MoI. Subsequently, MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added, and cells were incubated for 4 hours. Formazan crystals were dissolved using a solution prepared with sodium dodecyl sulfate (Thermo Fisher, 28312) and dimethylformamide (Sigma-Aldrich, 227056) at pH 4.6, followed by a final incubation of 18–24 hours. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm (BioTek-800TS, Winooski, VE, USA), with untreated cells considered as 100% formazan production. A dose-response curve was generated for each cell line under both treatments independently, and half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were determined using the four-parameter logistic model (J. A. Nelder and R. W. M. Wedderburn, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 1972). The IC50 values obtained were subsequently used for the cytotoxicity assay.

4.14. Cytotoxicity assay (LDH in supernatant)

Cytotoxicity was assessed using the CyQUANT™ LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Invitrogen, C20300), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1.5 × 10⁴ cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and treated with MoI, Cv, or ultrapure water (for the spontaneous LDH activity control) in a final volume of 100 µL. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in the Cv group and 48 hours in the MoI group. Subsequently, 10 µL of 10X Lysis Buffer was added to the maximum LDH control group and incubated for 45 minutes. Then, 50 µL of supernatant from each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate, followed by the addition and mixing of 50 µL of Reaction Mixture. After 30 minutes of incubation at room temperature, 50 µL of Stop Solution was added and mixed. Finally, absorbance was measured at 490 nm with correction at 690 nm (BioTek-SynergyHTX, Winooski, VE, USA). Cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula:

4.15. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± SD, T-student, ANOVA and Dunnet as post-hoc test was performed using R version 4.4.3, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.R., T.G.I. and M.M.G.; methodology, B.R.R., T.G.I., M.M.G, G.C.R, E.V.M., J.G.L., T.G.C., P.S.H., A.M.S., R.L.R. and I.B.L; investigation, B.R.R., T.G.I., M.M.G. and G.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.R., and T.G.I., writing—review and editing, B.R.R., T.G.I., M.M.G, G.C.R, E.V.M., J.G.L., T.G.C., P.S.H., A.M.S., R.L.R. and I.B.L; supervision, T.G.I. and M.M.G.; funding acquisition, T.G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

The FTIR spectrum of MoI shows characteristic bands of various functional groups, indicating the presence of bioactive compounds. The broad band between 3200-3600 cm-¹ is attributed to O-H stretches of alcohols and phenols, suggesting a high presence of polyphenolic compounds. The signals at 2800-3000 cm-¹ correspond to C-H stretches of methyl and methylene groups. The intense band at 1700-1750 cm-¹ confirms the presence of carbonyls (C=O), characteristic of carboxylic acids, ketones or aldehydes. Absorptions at 1500-1650 cm-¹ can be associated with C=C vibrations of aromatic rings, while bands at 1000-1300 cm-¹ indicate C-O stretches, typical of esters and phenolic compounds.

Figure 1.

The FTIR spectrum of MoI shows characteristic bands of various functional groups, indicating the presence of bioactive compounds. The broad band between 3200-3600 cm-¹ is attributed to O-H stretches of alcohols and phenols, suggesting a high presence of polyphenolic compounds. The signals at 2800-3000 cm-¹ correspond to C-H stretches of methyl and methylene groups. The intense band at 1700-1750 cm-¹ confirms the presence of carbonyls (C=O), characteristic of carboxylic acids, ketones or aldehydes. Absorptions at 1500-1650 cm-¹ can be associated with C=C vibrations of aromatic rings, while bands at 1000-1300 cm-¹ indicate C-O stretches, typical of esters and phenolic compounds.

Figure 2.

Comparison of formazan production in MDA-MB-231 cells after exposure to MoI for 24, 48 and 72 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (* = p<0.05; *** = p<0.001, compared with control).

Figure 2.

Comparison of formazan production in MDA-MB-231 cells after exposure to MoI for 24, 48 and 72 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (* = p<0.05; *** = p<0.001, compared with control).

Figure 3.

Percentage of formazan produced after treatment with MoI for 48 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*** = p<0.001, compared with control). .

Figure 3.

Percentage of formazan produced after treatment with MoI for 48 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*** = p<0.001, compared with control). .

Figure 4.

Percentage of formazan produced after treatment with Cv for 24 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*** = p<0.001, compared with control). .

Figure 4.

Percentage of formazan produced after treatment with Cv for 24 hours, etoposide was used as cell death-control, the determination was performed by MTT assay, the percentage was calculated in comparison to the untreated group taking it as 100% formazan production. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance between groups was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*** = p<0.001, compared with control). .

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of MoI and Cv was assessed by quantifying LDH release in the supernatant of treated cells. Cells were exposed to the IC50 of both treatments. A control group treated with the lysis buffer included in the kit was used to define 100% cytotoxicity. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Mean comparisons between groups were conducted using Student’s t-test (*** = p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of MoI and Cv was assessed by quantifying LDH release in the supernatant of treated cells. Cells were exposed to the IC50 of both treatments. A control group treated with the lysis buffer included in the kit was used to define 100% cytotoxicity. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Mean comparisons between groups were conducted using Student’s t-test (*** = p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Bromatological analysis of the L. graveolens.

Table 1.

Bromatological analysis of the L. graveolens.

| Nutritional Content |

Per 100g |

| Energy content |

363.4 Kcal (1539.2 KJ) |

| Moisture |

7.8% |

| Ash |

6.6% |

| Protein |

6.8g |

| Total fat |

4.2g |

| Available carbohydrates |

36g |

| Dietary fiber |

38.6g |

Table 2.

Total phenolic and flavonoids content and antioxidant capacity (DPPH, ABTS and FRAP) of MoI.

Table 2.

Total phenolic and flavonoids content and antioxidant capacity (DPPH, ABTS and FRAP) of MoI.

| ABTS |

DPPH |

Total phenolics |

Total Flavonoids |

FRAP |

| 42.837 ± 0.175 mMEQ Trolox/ g |

66.303 ± 0.228 mMEQ Trolox/ g |

27.765 ± 1.095§mgGAE/g |

22.343 ± 0.096 mg Eq quercetin/g |

109.85 ± 0.51 mMEQ FeSO4/ g |

Table 3.

IC50 of MoI and Cv in each cell line.

Table 3.

IC50 of MoI and Cv in each cell line.

| Cell line |

MoI IC50 |

Cv IC50 |

| HaCaT |

0.18mg/mL |

110µM |

| MCF-7 |

0.08mg/mL |

211µM |

| HCC-1954 |

0.15mg/mL |

123µM |

| MDA-MB-231 |

0.17mg/mL |

121µM |