1. Introduction

The goal of an information retrieval task is to accurately find the matching passage from a large set of passages based on a given query. It has been widely applied across various domains. For example, in the e-commerce field [

1], systems match relevant products based on user queries, while literature search engines match appropriate documents according to user input [

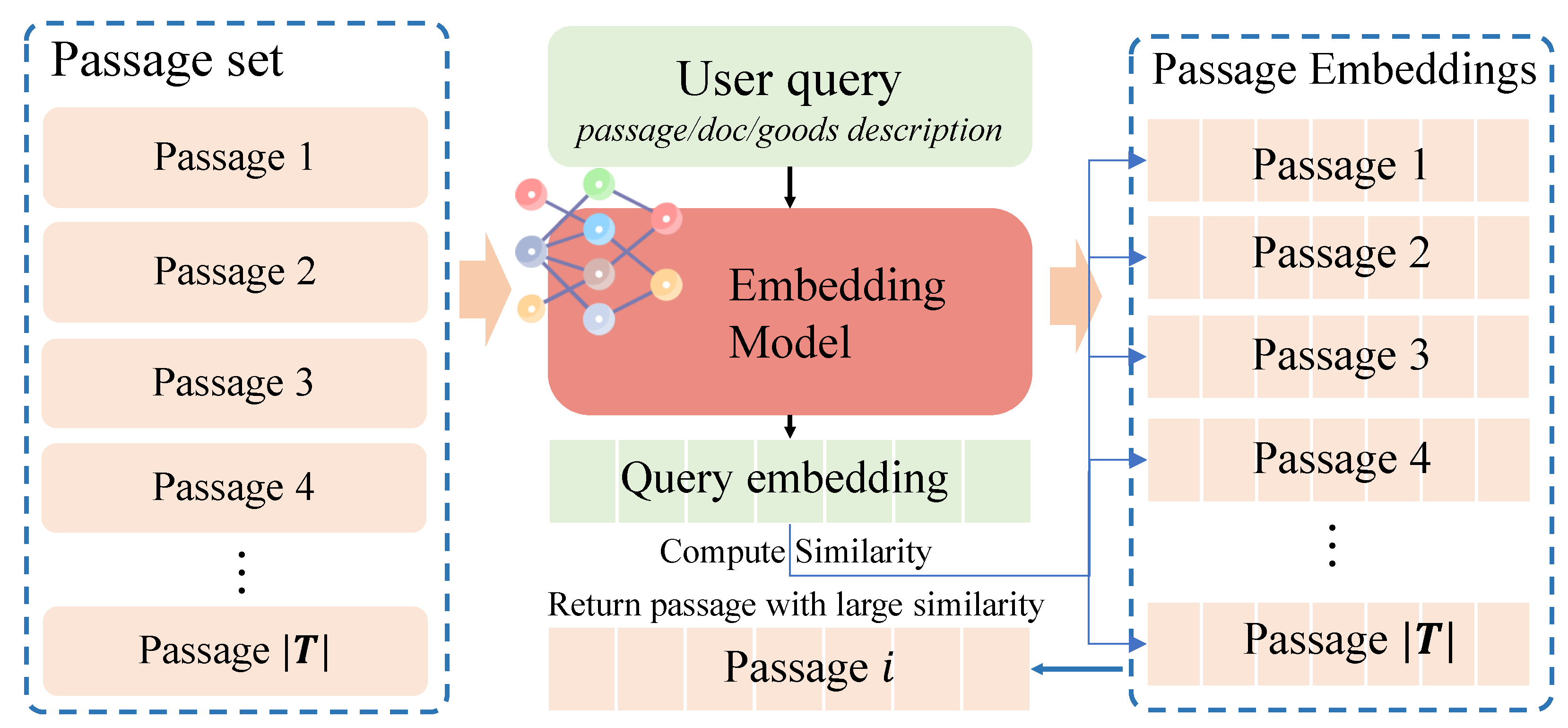

2]. Currently, as shown in

Figure 1, retrieval tasks typically use an embedding model to vectorize both the passage and the query, compute the similarity between the resulting embeddings, and then return the passage with the highest similarity as the matching result [

3]. Although this approach is simple and easy to implement, the training dataset for its core component — the embedding model — is usually biased, i.e., consisting mostly of simple queries. This limits the ability of embedding model to handle complex, hard queries, leading to a serious performance bottleneck and an upper limit on its effectiveness.

To address hard queries, existing approaches can be broadly categorized into two types: query rewriting methods and model-centric methods. Query rewriting methods propose rewriting each query into simple one during the inference phase for ease of processing by the embedding model. For instance, BEQUE [

4] rewrites queries into head-form equivalents using instruction-tuned LLMs, while RL-based Query Rewriting [

5] leverages reinforcement learning to adapt rewriting strategies. Though effective, such approaches may cause the loss of query semantics and fail to fully capture the retrieval intent of users. To address this, model-tuning methods propose improving the embedding models by designing novel training strategies. For example, BGE-M3-Embedding [

6] improves generalization by leveraging multi-granular representations, while Conan-Embedding [

7] utilizes batch-balanced contrastive training to optimize the embedding model. Although these methods have achieved significant success, they still rely on inherently biased datasets, which limits the full potential of the embedding model from being fully realized.

Orthogonal to model-centric or query rewriting methods, this paper proposes addressing the hard query challenge at the data level by generating hard queries to improve the embedding model. More specifically, Considering that the generated queries need to possess semantic or logical knowledge similar to that of humans, and inspired by the ability of agents to closely simulate human behavior, this paper proposes a multi-agent framework to generate hard queries, thereby improving the training performance of the embedding model. The core idea of our approach is to first adopt a generation agent to create new queries. Then, two specialized agents, i.e., Code agent for logical reasoning and CoT agent for semantic understanding, evaluate the queries to identify truly hard ones. Finally, agents with expertise in different domains engage in a discussion to further optimize the selected hard queries. Experimental results demonstrate that our method outperforms existing approaches. The major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

As is known to us, we are the first to propose a multi-agent data generation framework specifically for retrieval tasks. This framework leverages different agents to respectively handle the processes of generation, validation, and optimization, ensuring that the generated hard queries are close to real-world user queries.

For each generated sample, we introduce a dual-agent comparative verification scheme. One agent performs logical and rule-based validation by executing code, while the other conducts semantic validation through chain-of-thought reasoning, enabling the effective identification of truly hard queries.

We propose a multi-agent group discussion mechanism, involving agents with expertise across broader domains, to perform final validation and optimization of the hard queries, thereby ensuring the reliability of the generated samples.

We conduct extensive experiments on different datasets and models. Experimental results show that our proposed model consistently outperforms existing methods.

2. Related Work

Hard Query Handling in Retrieval. Processing hard queries are challenging due to their semantic complexity, low frequency, and lack of labeled data. Existing methods typically focus on model-centric improvements or query rewriting. On the model side, BGE M3-Embedding [

6] enhances generalization through multi-granular representations, while Conan-Embedding [

7] improves embedding quality by dynamically mining hard negatives and leveraging cross-GPU batch-balanced contrastive training. Although these methods can improve the robustness of the representation, they focus primarily on better utilization of existing data rather than generating new supervision signals. To handle hard queries, query rewriting methods propose rewriting each input query into simple one during the inference phase such that the embedding model can be able to well process hard queries. For example, BEQUE [

4] rewrites long-tail hard queries into head-form equivalents using instruction-tuned LLMs, while RL-based Query Rewriting [

5] leverages knowledge distillation and reinforcement learning to adapt rewriting strategies from real-time feedback. Though effective, such approaches may cause the loss of query semantics and fail to fully capture the user’s search intent. Orthogonal to model tuning or query rewriting methods, this paper proposes addressing the hard query challenge at the data level by generating hard queries to well train the embedding model.

Multi-Agent Systems. Recent research has explored the potential of multi-agent systems to enhance the reasoning capabilities of large language models across various domains. Multiagent Debate [

8] leverages agent debate mechanisms to enhance the factual accuracy of model outputs. GroupDebate [

9] proposes a group-based agent discussion framework that enhances reasoning efficiency by facilitating intra-group deliberation and inter-group consensus. MathChat [

10] presents a conversational multi-agent framework designed to tackle complex mathematical problems. Unlike these methods, our approach employs multi-agent discussion to refine labels for long-tail hard samples, enabling high-quality data generation for hard queries in retrieval tasks.

Retrieval Model Training and Preference Alignment. Traditional retrieval models, such as DPR [

11] and E5 [

12], rely on manually labeled data or unsupervised contrastive learning (e.g., InfoNCE [

13]) to learn query-passage interactions. Recent advancements integrate LLMs to improve retrieval quality by leveraging their contextual understanding. For example, Syntriever [

14] proposes partial Plackett-Luce ranking, which combines preference modeling with contrastive learning to align retrievers with LLM-generated relevance judgments. Despite their advancements, the above methods still struggle with long-tail hard queries, which are infrequent but potentially highly relevant for certain users.

3. Background

This paper focus on optimizing the embedding model to improve the retrieval task performance. As shown in

Figure 1, the retrieval task aims to retrieve the most relevant passages from the passage corpus

for any query

q. To achieve this, an embedding model

with the parameter

is adopted to vectorize each passage

and obtain

. Then, it embeds the query

to obtain

and calculates the distance between the query

and passage

, i.e.,

where

denotes the cosine similarity between two embeddings. The retriever will finally return a passage

that achieves the minimum distance among all passages

corresponding to the query

, i.e.,

. The retrieval task usually adopts a ground-truth label

to denote whether the returned

matches the query

, where

denotes a match between the returned result and the ground truth passage, whereas denotes a mismatch. During the training phase, the retrieval task seeks to minimize the following contrastive loss of all queries in the training dataset

to train the embedding model

:

where

m is a hyperparameter that sets the margin (typically

).

Objective of this paper. Although the above equation (

2) can be used to obtain an embedding model, the model usually suffers from poor performance because the hard query samples in the training dataset follow a long-tailed distribution, and the model cannot be sufficiently trained on these hard samples. To address this issue, we propose in this paper to increase the number of hard samples through sample generation. While some traditional rule-based methods for data augmentation or generation already exist, they often fail to generate queries that are close to real human queries, potentially losing the rich underlying semantics present in genuine user inputs. Recently, LLM-based agents have attracted significant attention because they can closely mimic human speaking styles, language content, and expression patterns, e.t.c. Inspired by this, we propose to generate samples using an agent-based approach, aiming to alleviate the problem of the long-tailed distribution of hard samples. Formally, we aim to generate a new query set

from the query training set

based on LLM agents.

4. Method

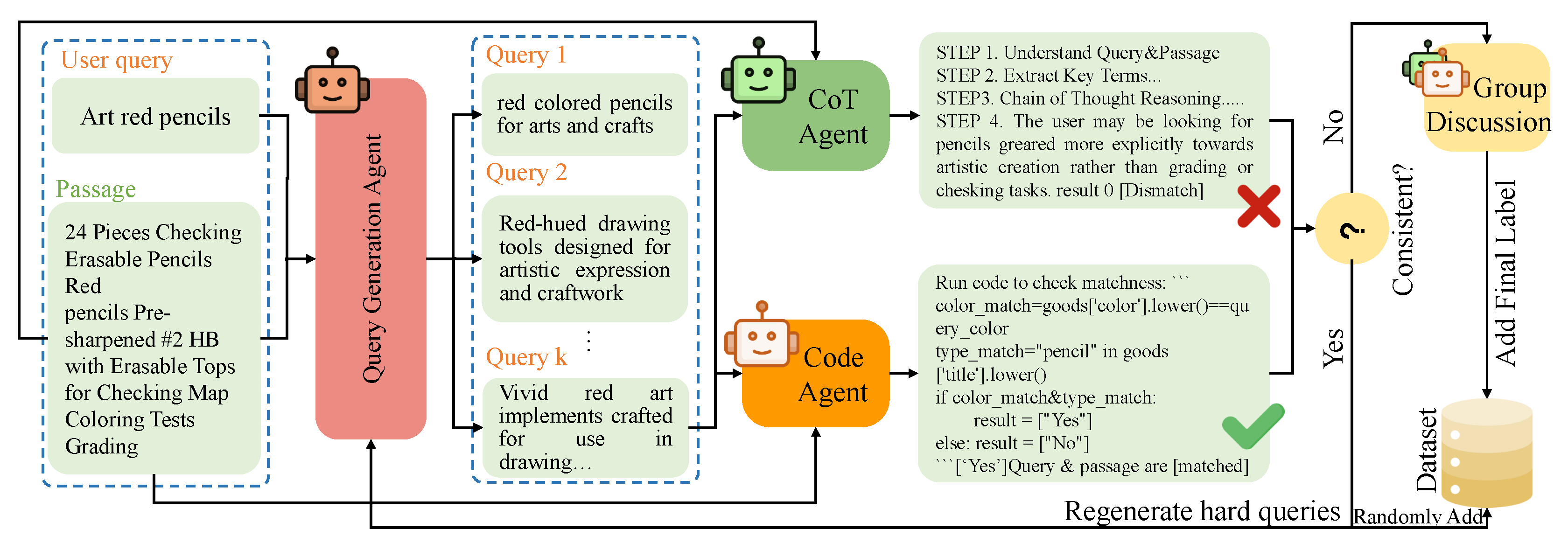

This section introduces ContrastGen, a multi-agent based retrieval data generation framework. As shown in

Figure 2, ContrastGen consists of two stages, i.e., contrastive agents based hard sample generation and group discussion based label refinement. The sample generation stage iteratively generates hard queries and the multi-agent group discussion stage determines the final label.

4.1. Stage 1: Contrastive Agents Based Hard Sample Generation

This stage aims to iteratively generate hard samples. Specifically, we first adopt a generation agent named QueryGen to rewrite the query. Further, considering that hard samples are often easily interpreted by agents with different perspectives as matching different passages, we further leverage two distinct agents — the Code Agent and the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Agent — to contrastively assess the matchness between the generated query and the original passage. When these two agents produce conflicting matching results, the corresponding sample is identified as a hard sample and is then fed into the subsequent discussion stage to determine its final matching label. Otherwise, the QueryGen agent is invoked to regenerate samples until hard samples are generated.

Iterative query generation via QueryGen agent. The QueryGen Agent iteratively synthesizes challenging queries based on the given passage and historical queries. In each iteration

k, ContrastGen feeds the query-passage pair

, along with the set of previously generated queries by the QueryGen agent

, and a prompt (see

Appendix A.1) into the QueryGen agent

, to generate a new query

. Then, ContrastGen forms a pair

by combining

with the passage

, and feeds this pair into both the Code Agent and the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Agent. If both agents consistently judge that

match or mismatch each other, the query is considered

easy, and it is added to the historical query list

. With a sampling probability

r, the query is also included in the generated training dataset

, or equally, the query is discarded with a probability

. The above process is then repeated to generate a new query. Notably,

is initialized as

. However, if the Code Agent and the CoT Agent disagree on whether

match, the query is considered

hard, and the generation process stops.

4.1.0.1. Contrastive Macthness Assessment via Code and CoT Agents

After obtaining the generated query, ContrastGen employs both the Code Agent and the CoT Agent to verify whether the query matches the original passage. The Code Agent assesses the match based on structured rule-based reasoning, while the CoT Agent determines the match through semantic understanding. Therefore, these represent two fundamentally different perspectives. When the query is complex and difficult to understand, it is more likely to lead to inconsistent judgments from the two agents.

Code agent. By taking the query-passage pair

as input, the Code Agent will extract several attributes or expressions that can be compared or computed, and then automatically generate code to perform reasoning through program execution in a sandbox environment. The prompt and execution example are shown in

Appendix A.2. Finally, the Code Agent

, by invoking the execution engine, outputs a matching decision result

indicating whether

and

match.

CoT agent. To assess the matchness of the query-passage pair

, CoT agent applies the chain of thought reasoning with four steps (an example and prompts can be seen in

Appendix A.3):

Step 1. Understand the query and passage. Clarify user intent and identify product features.

Step 2. Extract Key Terms. Highlight key attributes, synonyms, and functional components.

Step 3. Apply Reasoning. Relate extracted query terms with passage attributes, accounting for synonyms and logical equivalences.

Step 4. Generate Conclusion. Decide on match/mismatch based on accumulated evidence.

With the four reasoning steps, the CoT agent obtains the matchness results . Finally, ContrastGen checks whether and are the same. If they match, the sample is considered an easy sample, and it is fed back to QueryGen to generate a new query. The sample is also added to the generated dataset with a certain probability. Otherwise, the process proceeds to the next stage, where a group discussion mechanism is employed to make the final determination on whether the pair matches.

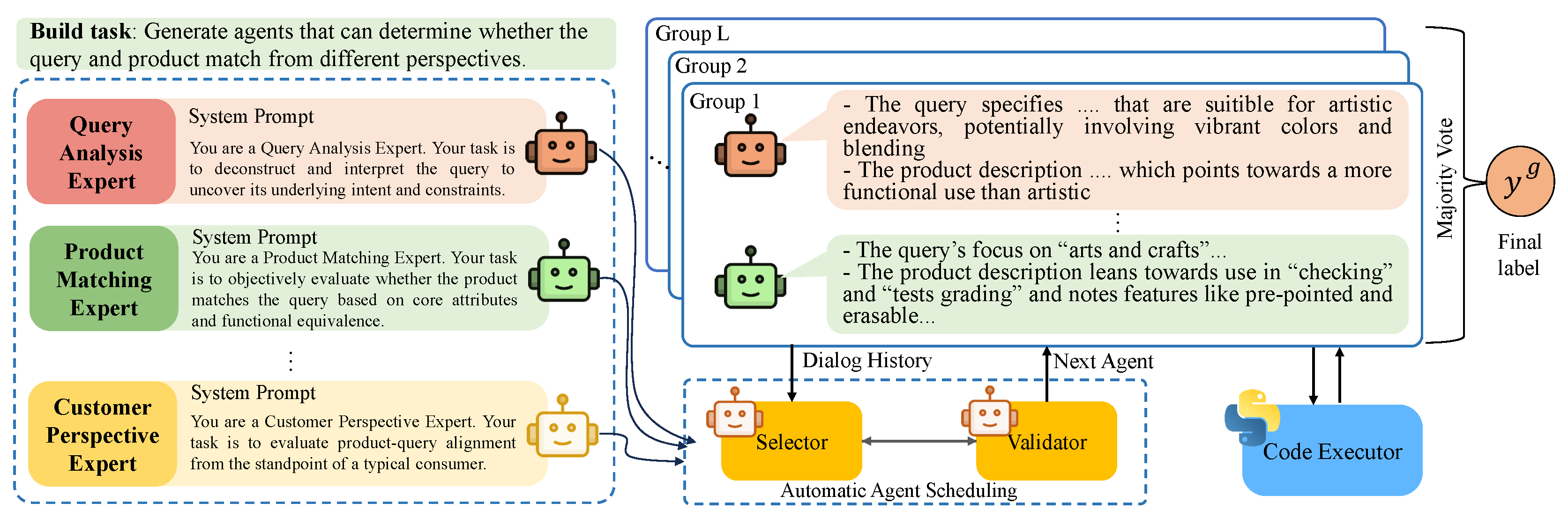

4.2. Stage 2: Multi-Agent Group Discussion for Label Refinement

To determine the final matchness label, the hard query is delivered to the multi-agent group discussion stage, where multiple groups independently analyze the query–passage pair and vote to reach the final consensus.

Multi-agent group building. For each group, we build discussion agents based on task-specific expertise roles, simulating a realistic multi-role discussion scenario, as illustrated in

Figure 3. We use various system prompts to build different expert agents. For instance, when the passage are products, the agents are built by including the Query Analysis Expert, Product Matching Expert, Customer Perspective Expert, and Market Trends Expert, e.t.c. An example can be found in

Appendix A.4. These agents engage in role-based multi-turn discussions, each focusing on their specialized perspective to validate or refute the initial matchness. Besides, we allow agents to invoke executable code snippets or perform commands via a code executor, when logic verification is required.

Discussion. To coordinate the discussion among multiple agents within each group

l, we adopt an automatic agent scheduling strategy which includes an Agent Selector and a Validator. The Selector proposes the name of the next agent to speak based on the dialogue history, while the Validator checks whether the proposal corresponds to a valid agent. If the proposed name does not match any existing agent, the Validator feeds this back to the Selector, prompting it to generate a new proposal. This process repeats until a valid agent speaker is identified or the maximum number of attempts is reached. If all attempts fail, a fallback strategy—such as round-robin—is used. In each round

t, the selected agent

takes as input the query-passage pair

and the historical decisions from other agents in the group:

and produces a decision

. After

T-round discussion among agents, ContrastGen applies a majority voting scheme over all agents’ decisions to produce the final group decision:

Next, ContrastGen makes the final decision by applying a global majority voting process from all

L independent groups:

Based on the value of

, ContrastGen determines the final matching label for the query-passage pair. Specifically,

signifies a matching pair, which is labeled as a positive example, while

denotes a non-matching pair, treated as a negative example. Finally, the embedding model is trained using the generated dataset

with equation (

2).

5. Experiments

5.1. Experiment Setup

Datasets. We evaluate our approach on two publicly available datasets: the

Shopping Queries [

15] and the

arXiv [

16]. The Shopping Queries Dataset consists of multilingual search queries, each associated with up to 40 related products, annotated using ESCI relevance judgments (Exact, Substitute, Complement, Irrelevant). The arXiv Dataset contains over 1.7 million scholarly articles, including metadata such as titles and authors. For this dataset, queries were generated using GPT-4o-Mini [

17]. Both datasets utilize binary relevance labels (0 or 1) to indicate query-passage matches, facilitating an assessment of search quality and user experience enhancement. We implement ContrastGen based on the LangChain

1 and AutoGen [

18] frameworks, and use these two datasets to generate new contrastive data.

Baseline. We compared our approach of training models with incrementally generated data against several baseline methods.

BM25 [

19]: A traditional keyword-based retrieval model employing the BM25 ranking function.

Zero-Shot: A pre-trained model evaluated without task-specific training or fine-tuning on the target dataset.

Original Data: A model trained solely on the original dataset without data augmentation.

In-Batch Negatives [

20]: A method that dynamically selects negative samples from the same training batch to enhance discriminative capability. These baselines serve as reference points to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed incremental data generation strategy.

Backbone. Our study employs both the

BGE-M3 model [

6] and the

Conan-embedding-v1 model [

7]. BGE-M3 is a retrieval model trained on diverse datasets and excels in multilingual and cross-lingual tasks, accommodating inputs ranging from short queries to documents of up to 8,192 characters. It integrates dense, sparse, and multi-vector retrieval techniques. Conan-embedding-v1 further enhances embedding quality through dynamic hard negative mining and cross-GPU balancing loss, which expose the model to more informative negative samples during training and alleviate memory constraints.

Evaluation Metrics. We assess model performance using Precision@K, Recall@K, and NDCG@K, with . Precision@10 quantifies the proportion of relevant items among the top 10 retrieved results, Recall@10 measures the proportion of relevant documents retrieved within the top 10, and NDCG@10 evaluates ranking quality by assigning higher scores to correctly ranked relevant items. The test set consists of 10,000 items sampled randomly from both original and generated data.

Configurations. Unless otherwise specified, models are trained with a learning rate of 2e-6 for the Shopping Queries Dataset and 1e-6 for the arXiv Dataset. Training data comprises 2,000 original samples and 2,000 additional generated samples, totaling 4,000 samples. In-batch negative sampling is conducted using 2,000 samples by default. All experiments were conducted on a single RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of VRAM, a 16-core Intel Xeon® Gold 6430 CPU, and 120 GB of RAM.

5.2. Performance Overview

Retrieval Performance.Table 1 presents the retrieval performance of different methods across the Shopping Queries and arXiv datasets. Our proposed approach using BGE-M3 with generated data achieves the best overall results, reaching a Recall@10 of 55.65% on Shopping Queries and 61.79% on arXiv, outperforming both the vanilla BGE-M3 and Conan models. While the Conan-based methods show consistent improvements when incorporating generated data—achieving 49.61% Recall@10 on Shopping Queries and 38.59% on arXiv—they still lag behind BGE-M3 across all metrics. These results highlight the superior retrieval capability of BGE-M3 and the effectiveness of generated data augmentation. Notably, both models benefit from generated training data, indicating the generalizability of the approach.

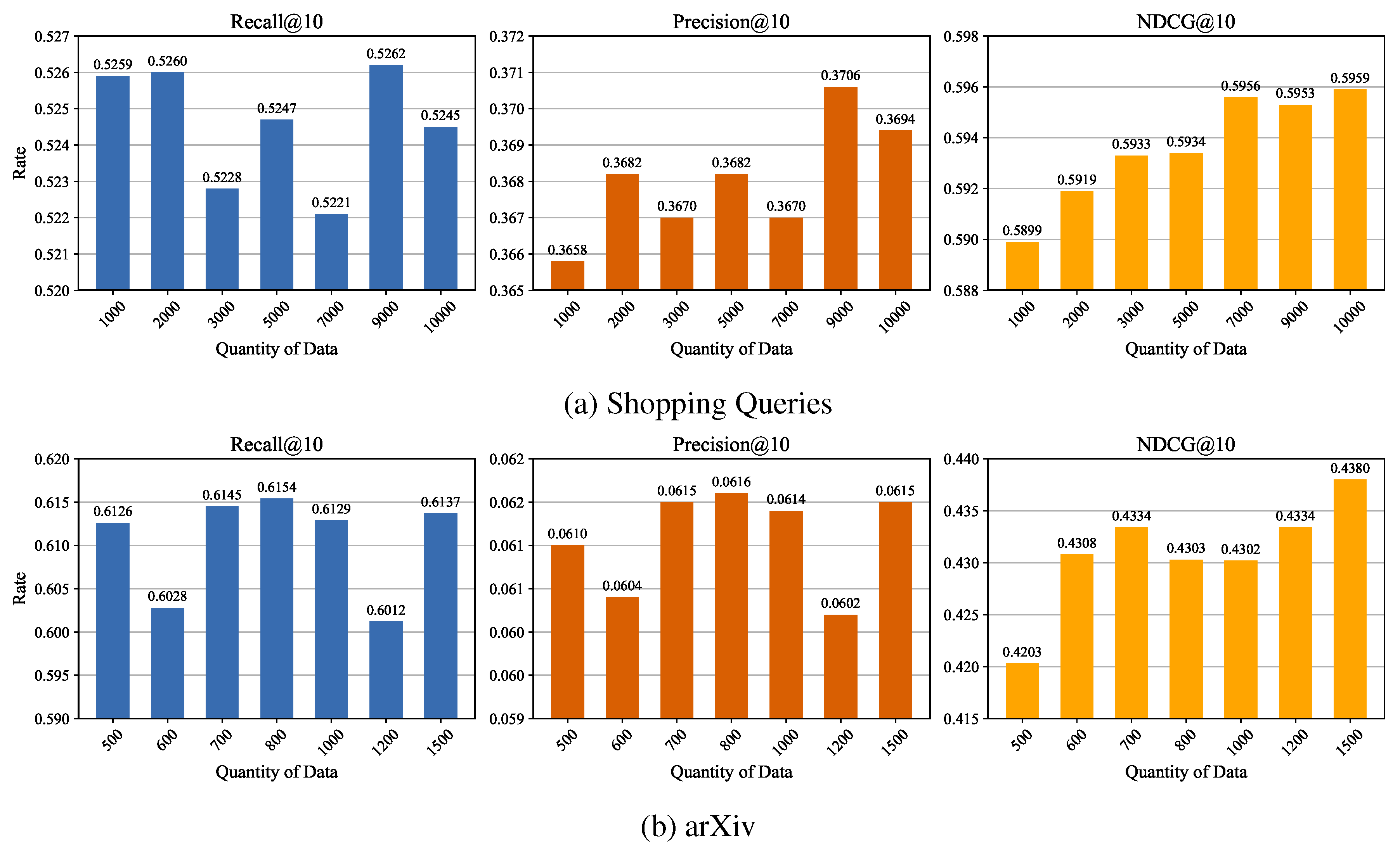

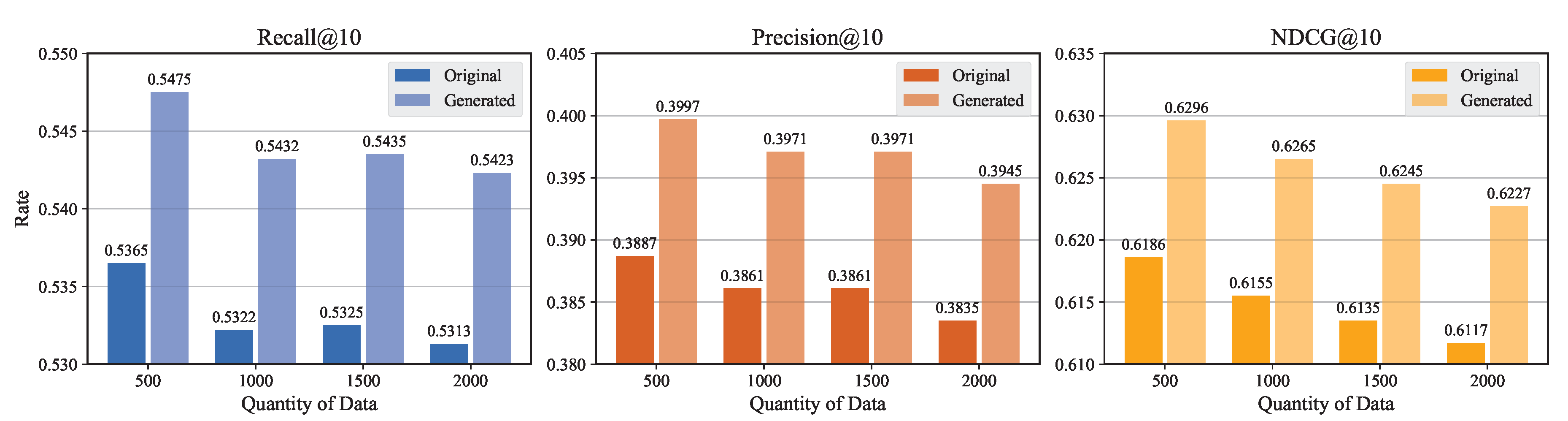

Effect of Data Quantity. As shown in

Figure 4, retrieval performance improves with moderate data augmentation but degrades when exceeding an optimal threshold. For the Shopping Queries dataset

Figure 4a, Recall@10 and Precision@10 peak at 9,000 samples (0.5262 and 0.3706), while NDCG@10 continues to rise slightly to 0.5959 at 10,000 samples. In contrast, the arXiv dataset

Figure 4b shows peaks in Recall@10 (0.6154) and Precision@10 (0.0616) at 800 samples, but NDCG@10 improves further to 0.4380 at 1,500 samples. This non-monotonic trend suggests that excessive data introduces noise or redundancy, reducing model generalization. The optimal data quantity varies by task: 9,000–10,000 samples work best for Shopping Queries, while arXiv benefits most from 1,500 samples. Thus, data augmentation should be tailored to the dataset to balance performance gains and overfitting risks.

Impact of Positive-Negative Ratios.Table 2 examines the influence of different positive-to-negative sample ratios on model performance. Optimal performance is observed when the ratio is balanced within a specific range, whereas an excessive number of negative samples adversely affects model effectiveness. Notably, a 10:9 ratio yields the highest Recall@10 (0.5353) on Shopping Queries, whereas an imbalanced 1:2 ratio leads to reduced NDCG scores.

Influence of Data Type.Table 3 investigates the effect of different data types (Easy, Hard, Mixed) on model performance across two tasks: Shopping Queries and arXiv. Hard samples consistently yield the highest performance across all metrics (Recall@10, Precision@10, NDCG@10) in both tasks. For Shopping Queries, Hard data achieves 0.5361 (Recall@10), 0.3766 (Precision@10), and 0.5981 (NDCG@10); for arXiv, these values are 0.6162, 0.0617, and 0.4385 respectively. This indicates that challenging samples effectively enhance the model’s discriminative ability to distinguish between positive and negative instances.

Effectiveness of Generated Data under In-Batch Negatives Training.Figure 5 compares BGE-M3 performance trained with varying quantities of original and generated data using the in-batch negatives strategy. Across all scales, models trained on generated data consistently outperform those using original data. For instance, with 500 samples, generated data achieves a Recall@10 of 0.5555 compared to 0.5365 for original data. This advantage persists even as data volume increases, indicating greater robustness and generalization. Additionally, performance with original data slightly declines as quantity increases, suggesting redundancy or domain saturation. These results highlight the effectiveness of high-quality synthetic data in retrieval tasks under contrastive training settings.

Ablation study. To evaluate the contribution of each individual component of ContrastGen, we compare three distinct configurations: (1) CoT Agent only, where only the CoT agent is employed for labeling queries based on semantic reasoning; (2) Code Agent only, where only the Code agent is used to label queries based on logical and rule-based validation through executable code; and (3) ContrastGen, which integrates all components. The performance of each configuration in terms of data quality and downstream retrieval performance is summarized in

Table 4. The results clearly indicate that removing any component leads to a measurable decline in performance. When only the CoT agent is used, the generated queries may suffer from hallucinations or semantic drifts due to the generative nature of the model. On the other hand, relying solely on the Code agent may miss nuanced linguistic variations and fail to capture complex user intents, leading to overly rigid or syntactically correct but semantically less meaningful queries. In contrast, the full ContrastGen framework benefits from the complementary strengths of both agents. Discrepancies between the CoT and Code agent outputs are effectively resolved through the multi-agent group discussion mechanism, which brings in diverse perspectives and domain expertise to refine and validate the final label of hard samples. This collaborative filtering and refinement process significantly improves label accuracy and ensures higher fidelity in the resulting query-passage pairs. Overall, this ablation study highlights the necessity of each component and demonstrates that their combination is crucial for achieving optimal performance.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

To address the challenge of insufficient hard queries in training datasets for embedding models in retrieval tasks, this paper proposes ContrastGen, which leverages a multi-agent framework to generate hard samples. The core idea of the method is to employ different agents to separately handle the generation, discrimination, and optimization of hard queries, ultimately forming effective positive or negative hard query-passage pairs. Experiments conducted on various types of embedding models and different datasets demonstrate that our approach consistently outperforms existing methods.

Although the proposed ContrastGen framework achieves promising results in generating high-quality hard queries for retrieval tasks, the proposed method remains unrelated to the embedding model. Therefore, we aim to incorporate feedback mechanisms from the embedding model itself into the query generation pipeline. By enabling a closed-loop training paradigm, where the model performance on hard queries guides further data generation, we can achieve more targeted and iterative improvements in model robustness.

Limitation. Our work mainly generates hard sample data through agent-based iterative processes. When a query is difficult to rewrite into a harder version, the number of iterations may reach the preset upper limit, leading to significant consumption of computational resources. Moreover, our approach employs a multi-agent system based on large language models to perform tasks such as generation, validation, and optimization, which also incurs substantial resource costs. Therefore, reducing the computational overhead of hard query generation is a key limitation that we aim to address in future work.

Appendix A. Key Prompts

Appendix A.1. Prompt for QueryGen Agent

Positive QueryGen (GPT-4o-mini)

Negative QueryGen (GPT-4o-mini)

Appendix A.2. Prompt for Code Agent

Summary (GPT-4o-mini)

Test Task (GPT-4o-mini)

Problem (GPT-4o-mini)

Appendix A.3. Prompt for CoT Agent

System (GPT-4o-mini)

User (GPT-4o-mini)

Appendix A.4. Prompt for Discussion Agent

Discussion Task (GPT-4o)

Appendix B. Example

Table A1.

The instance of ContrastGen enhanced data.

Table A1.

The instance of ContrastGen enhanced data.

| Passage |

Type |

Query |

Label |

| Distressed Baseball Cap - Mom Life (Black) |

| Vintage style; Washed & distressed; Low profile crown. Unconstructed style gives off a "dad hat" vibe. Suitable for wear during summer, spring, winter, and fall. Prime features include adjustable closure, unstructured crown, and all-day relaxation. |

Original |

black baseball cap |

1 |

| |

Easy |

vintage unstructured dad hat for moms |

1 |

| |

Hard |

unstructured relaxed fit black cap for all seasons |

1 |

| KISS Magnetic Lashes, Crowd Pleaser, 1 Pair of Synthetic False Eyelashes With 5 Double Strength Magnets, Wind Resistant, Dermatologist Tested Fake Lashes Last Up To 16 Hours, Reusable Up To 15 Times |

Original |

magnetic false eyelashes |

1 |

| |

Easy |

wind resistant magnetic lashes without liner |

1 |

| |

Hard |

reusable fake eyelashes for winter tested by dermatologist |

1 |

| Mellanni Queen Sheet Set - Hotel Luxury 1800 Bedding Sheets & Pillowcases - Extra Soft Cooling Bed Sheets - Deep Pocket up to 16 inch Mattress - Wrinkle, Fade, Stain Resistant - 4 Piece (Queen, White)" |

Original |

6 quart crockpot |

0 |

| |

Easy |

cool beds for boys |

0 |

| |

Hard |

soft queen blankets for winter warmth |

0 |

References

- Zheng, X.; Lv, F.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, X. Delving into E-Commerce Product Retrieval with Vision-Language Pre-training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2023, pp.

- Liu, S.; Chen, C.; Ding, K.; Wang, B.; Xu, K.; Lin, Y. Literature retrieval based on citation context. Scientometrics 2014, 101, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lv, F.; Jin, T.; Lin, G.; Yang, K.; Zeng, X.; Wu, X.M.; Ma, Q. Embedding-based product retrieval in taobao search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery &.

- Peng, W.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ou, D.; Zeng, X.; Xu, D.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. Large language model based long-tail query rewriting in taobao search. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, 2024, pp. 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Mohan, R.K.; Yang, V.; Akash, P.S.; Chang, K.C.C. RL-based Query Rewriting with Distilled LLM for online E-Commerce Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.18056, arXiv:2501.18056 2025.

- Chen, J.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, P.; Luo, K.; Lian, D.; Liu, Z. BGE M3-Embedding: Multi-Lingual, Multi-Functionality, Multi-Granularity Text Embeddings Through Self-Knowledge Distillation. CoRR, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, X. Conan-embedding: General Text Embedding with More and Better Negative Samples. CoRR, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Mordatch, I. Improving factuality and reasoning in language models through multiagent debate. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Xu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yang, H.; Li, J. Groupdebate: Enhancing the efficiency of multi-agent debate using group discussion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.14051, arXiv:2409.14051 2024.

- Wu, Y.; Jia, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, E.; Wang, Y.; Lee, Y.T.; Peng, R.; Wu, Q.; Wang, C. Mathchat: Converse to tackle challenging math problems with llm agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01337, arXiv:2306.01337 2023.

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2020, Online, November 16-20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Jiao, B.; Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Majumder, R.; Wei, F. Text Embeddings by Weakly-Supervised Contrastive Pre-training. CoRR, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, A.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding. CoRR, 1807. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Baek, S. Syntriever: How to Train Your Retriever with Synthetic Data from LLMs. CoRR, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.K.; Màrquez, L.; Valero, F.; Rao, N.; Zaragoza, H.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Biswas, A.; Xing, A.; Subbian, K. Shopping queries dataset: A large-scale ESCI benchmark for improving product search. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.06588, arXiv:2206.06588 2022.

- Clement, C.B.; Bierbaum, M.; O’Keeffe, K.P.; Alemi, A.A. On the use of arxiv as a dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.00075, arXiv:1905.00075 2019.

- Hurst, A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A.; et al. Gpt-4o system card. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21276, arXiv:2410.21276 2024.

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Autogen: Enabling next-gen llm applications via multi-agent conversation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.08155, arXiv:2308.08155 2023.

- Robertson, S.; Zaragoza, H.; et al. The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Yao, X.; Chen, D. Simcse: Simple contrastive learning of sentence embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08821, arXiv:2104.08821 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).