1. Introduction

Within Agriculture 4.0 technology, the development of robotic harvesting systems represents a challenge for researchers. These robotic systems must adapt to a large number of different conditions, due to the variety of foods to be harvested, in addition to the special care that must be taken with certain products that are more delicate in nature, and the quality of the product must be preserved [

1]. Conventional harvesting techniques depend on human labor, and although there are automated systems, these work with specific crops whose characteristics allow the intervention of heavy machinery. However, harvesting activities are still carried out by people in a time-consuming, monotonous, and costly process that depends on seasonal labor [

2]. As the demand for fresh produce increases annually, it is obvious that automation will play a crucial role within the agricultural sector to supply the amount of crops required worldwide [

3].

The greatest difficulty in fruit harvesting is the variety of fruits. Fruits come in different sizes, shapes, textures, etc., making the harvesting task impossible to unify into a single process, as a harvesting process must be guaranteed without causing damage to the fruit [

4]. Robotic grippers are typically made of hard materials, such as steel or aluminum, and although they are very useful in industrial applications, if used in fruit harvesting processes, they will destroy the fruit, as they are unable to adapt to different textures. Grippers must also be adapted using complex algorithms or specialized sensors to improve their efficiency [

5]. To solve this problem, the concept of soft robotics is used, using flexible materials to construct elements that can adapt to different fruits without resorting to excessive complexity, reducing the likelihood of damaging the harvested product [

6].

The continuous improvement in 3D printing now allows the construction of low-cost robotic systems capable of being customized to meet different needs. It is now possible to manufacture a flexible gripper thanks to thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), a material that allows manufacture of a system with sufficient flexibility to handle the fruit and, at the same time, sufficient strength to perform the harvesting without damaging the product [

7]. With the help of this material, it is possible to build prototypes to adapt to different conditions, allowing for adjustment at each stage of design and construction [

8].

For this research, not only is the gripper important; the arm is crucial as a complement to the robotic system, which must be precise, reliable, and easy to build. For the development of the robotic arm, a three-degree-of-freedom arm powered by Nema 17 stepper motors was chosen. These are inexpensive and easily acquired, ideal for providing controlled and repeatable movements [

9,

10]. While the arm moves with the stepper motors, the gripper moves with the help of a system based on nylon cables, which are pulled by four 180-degree servomotors, allowing the four-point gripper to adapt to any type of fruit [

11]. The article includes the calculations necessary to validate the use of these motors. Although they are inexpensive, if used properly, they can meet their harvesting objective in controlled situations.

The research aims to contribute to the field of agricultural automation by presenting a low-cost robotic arm capable of adapting to different types of fruit. Leveraging 3D printing, the arm can be adapted to different situations with minimal changes, and the design can be scalable for larger prototypes [

12]. The research shows the real capacity by performing statistical calculations that determine the viability of the robot, so with this information subsequent adjustments can be made for its implementation in real environments, paving the way for increased automation within the agricultural industry [

13].

Although several approaches to fruit harvesting automation already exist, most present limitations in terms of adaptability and cost. Many robotic systems opt for rigid systems coupled with advanced sensors to perform the harvesting action, increasing complexity [

14]. In contrast, the developed arm uses an innovative approach based on a 3D-printed flexible gripper, which allows for greater adaptability to different types of fruit without the need for additional sensors, thus reducing manufacturing and maintenance costs. Furthermore, the robotic arm’s modularity allows for rapid adjustments to different agricultural scenarios, representing a competitive advantage over solutions specialized for specific crops. It should be noted that this has not yet been tested in real-world environments.

2. Robotic System Design

The robotic arm prototype was built in several stages, from discovering the characteristics it must have for operation, its design, construction, and continuous component testing, to obtaining a functional prototype. This section explains the process, material selection, construction, and its mechanical strength and torque characteristics.

The entire robotic prototype, including the arm and gripper, was designed using Autodesk Fusion 360 software. The parts were modeled so they could be easily edited if the size of the robotic arm was desired, allowing for refinement of the constructed parts until the best possible model was obtained, ensuring compatibility between the mechanical and electronic elements [

15]. The arm’s movement is achieved by transmitting the force from the motors through toothed belts similar to those used by 3D printers. Furthermore, the design uses modular parts that can be exchanged for maintenance or simply replaced with new ones.

As this is a prototype, it is not yet ready for real-world testing and has only been carried out in controlled environments, within a closed laboratory with fruit positioned manually.

2.1. Mechanical Design of the Robotic Arm

The robotic arm prototype consists of a 360-degree rotating base, a main arm lifted by two parallel motors, and a secondary arm, to which the flexible gripper is connected. This assembly allows the fruit to be reached and manipulated within a controlled ecosystem. The prototype focuses on structural balance and maneuverability, ensuring efficient handling.

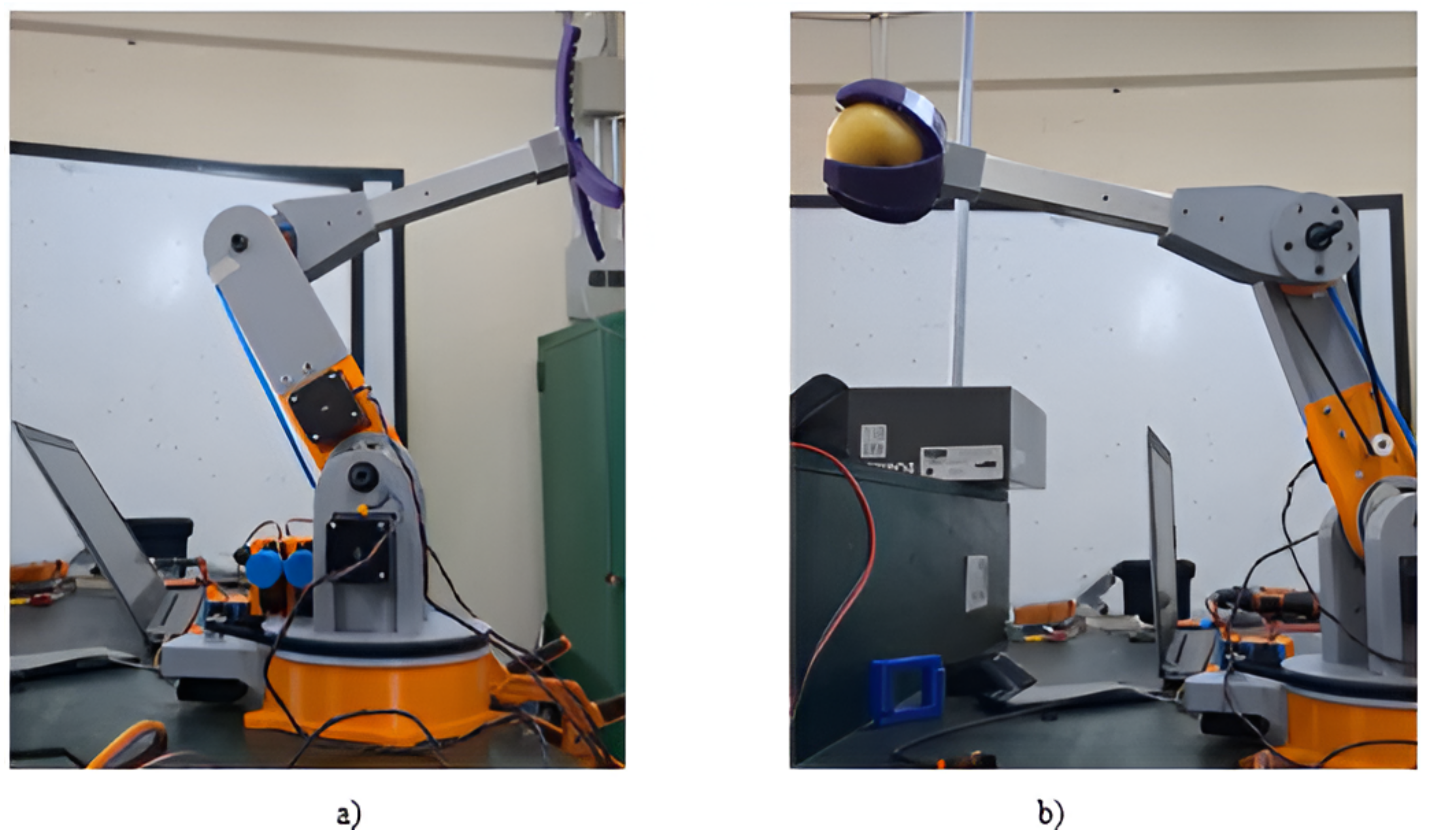

Figure 1 illustrates the general structure of the robotic arm and its key mechanical components.

The robotic arm structure was manufactured with polylactic acid (PLA), a material selected for its ease of printing and lightness. The use of additive 3D printing techniques allowed for rapid prototype construction and component modification as needed [

16]. The secondary arm is mostly made of a metal structure (aluminum), which guarantees greater structural strength, and the motors were chosen to provide precise position control and sufficient force to ensure movement [

17]. This entire set of elements results in an arm with controlled movements and precision quite adequate for a first prototype.

2.2. Degrees of Freedom and Transmission System

To achieve precise control, the joints are rotated using a system of pulleys and timing belts. This design increases the power of the NEMA 17 motors and improves movement efficiency, ensuring smooth motion. The motor pulleys are commercially available, and the pulleys that complement the system are constructed from PLA, so simply changing the pulleys changes the transmission ratio. This decision was implemented to increase the effective output torque and thus improve the overall performance of the prototype.

As shown in

Figure 2, the distribution of the arm components is explained below:

Main Base: A single Nema 17 motor rotates the robotic arm in the horizontal plane, allowing a 360-degree rotation.

Main Arm: For this part, two Nema 17 motors are used in parallel, facing each other, ensuring sufficient torque to initiate movement with or without a load.

Secondary Arm: A motor controls the secondary elevation of the robotic arm, ensuring optimal positioning.

2.2.1. Modular Secondary Arm and Adaptability

The secondary arm was designed using an interchangeable square aluminum profile as shows

Figure 3, allowing its length to be adjusted according to the specific requirements of different harvest environments. This modular approach enhances the system’s adaptability to various crop types and plant heights. Aluminum was selected over PLA due to its superior mechanical properties, as an extended PLA structure would lack sufficient strength, increasing the risk of structural failure. In contrast, aluminum provides enhanced durability while maintaining a lightweight design, ensuring the secondary arm remains both robust and maneuverable.

The modular design allows for the easy replacement of the aluminum profile with longer or shorter versions without compromising the stability of the robotic system. However, each modification must consider the maximum torque ratings of the stepper motors to prevent mechanical overload.

Figure 3 illustrates the attachment mechanism of the secondary arm and its modular extension capabilities.

2.2.2. Material Selection and 3D Printing Technology

The material selected for the prototype’s construction was designed to achieve a balance between structural strength and lightweight design, and therefore the following was selected, shows

Figure 4

PLA (polylactic acid): This material is used for almost the entire arm due to its ease of printing. There are better alternatives such as ABS or carbon fiber. PLA was chosen while the prototype is being evaluated. The material will be changed when a later version is obtained.

Aluminum: This material is only used in the secondary arm, as PLA does not provide sufficient rigidity at the ends of the arm due to the loss of strength along the print lines.

All elements are joined with screws, which facilitates assembly and disassembly in a matter of minutes. This approach ensured a cost-effective and accessible manufacturing process for future research.

2.2.3. Design and Modeling of the Flexible Gripper

The flexible gripper was developed with a focus on flexibility and adaptability, allowing the same system to be used in various harvesting scenarios. Therefore, this prototype focuses on fruits ranging from 4 cm to 12 cm in diameter and weighing approximately 100 g to 200 g. The design ensures a secure grip without the need for additional sensors.

The gripper was designed to be printed in a single piece, reducing the number of parts required to assemble. The gripper consists of four tips, each of which can be moved together or independently. This mechanism allows a single servomotor to complete the grip, or up to four servomotors to complete the grip. This decision was made to increase gripping force without compromising the size of the arm, as the servos are driven by nylon threads. The servomotors are located at the base, not at the end of the arm, significantly lightening the mechanism. This configuration also allows the gripping of asymmetrical fruits with only slight programming changes.

The primary advantages of this design include:

Weight reduction of the entire structure: By having almost all the motors located at the base, the weight of the arm is reduced, allowing the maximum use of the torque delivered by the motors for the final harvesting task.

Adaptable grip: The TPU-printed part can adjust to almost any shape, depending only on the correct configuration of each end. It does not require additional sensors as long as the same type of fruit is maintained during the harvesting stage. It cannot be switched from one fruit to another without the necessary adjustments.

Easy maintenance: The gripper does not have complex or fragile mechanisms like most mechanical grippers; it only needs to be cleaned, and if it breaks, it can be replaced.

Figure 5 illustrates the overall structure of the gripper and its operating principle.

2.2.4. Use of TPU in Gripper Manufacturing

For the construction of the flexible gripper shown in

Figure 6, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) was chosen, a material used in various 3D printing applications, due to its mechanical properties, which provide a good combination of flexibility and strength. Its main characteristics include:

Controlled elasticity: It allows deformation without permanent changes, ensuring a smooth and adaptable grip.

High resistance to mechanical fatigue: The material has been shown to be capable of deforming in controlled cycles without damaging its structure.

Low moisture absorption: The natural moisture of fruits can be a problem for conventional mechanisms; TPU is not affected by moisture, although more extensive testing is necessary once testing in real-world environments begins.

2.2.5. Implementation of the Actuation System

The actuation system of the robotic arm consists of NEMA 17 stepper motors for the movement of the base, main arm, and secondary arm, as well as four 360° MG996R servomotors for controlling the flexible gripper. These actuators were selected based on the torque requirements necessary to ensure stable and precise movement while minimizing the total weight of the system, shows

Figure 7

2.2.6. Torque Calculation for the Rotation Base

The first NEMA 17 motor is located at the base of the arm and is responsible for the rotation along the vertical axis. To calculate the required torque, we consider the length of the fully extended arm (518 mm = 0.518 m) and the total weight of the system (2 kg).

The force exerted due to gravity is:

The torque required to rotate the arm around the base is:

Given that a single commercial NEMA 17 motor has a maximum torque of 0.45 Nm, this value is insufficient. To compensate for this, a mechanical reduction is employed with a transmission pulley of a 1:8 ratio, which increases the output torque to:

This value is still not enough to support the weight of the arm and rotate it stably. However, there are techniques that allow achieving the objective without relying on motors with higher torque. The method for rotating the arm was reconsidered, and it no longer rotates when fully extended. Instead, the arm rotates while retracted, which reduces the torque. Therefore, the length taken into account is now 150 mm, thus concentrating almost all the weight at the larger base.

2.3. Initial Data

Length of retracted arm: 150 mm = 0.150 m

Total mass: 2 kg

Gravitational acceleration: 9.81 m/s²

NEMA 17 motor torque: 0.45 Nm

Transmission ratio: 8:1 (calculated using pulley diameters)

2.4. Calculation of Gravitational Force

The gravitational force exerted is calculated as:

2.5. Calculation of Torque with the New Effective Distance

The torque required with the new retracted arm length is:

2.6. Verification with Pulley Transmission

The small pulley connected to the motor has a diameter of 20 mm = 0.020 m, giving a radius of 0.010 m. The large pulley has a diameter of 160 mm = 0.160 m, giving a radius of 0.080 m.

2.7. Theoretical Transmission Ratio

The theoretical transmission ratio is calculated as:

With a NEMA 17 motor providing 0.45 Nm of torque, the output torque is:

Now, with the arm retracted to 150 mm, the required torque is 2.94 Nm, while the system provides 3.6 Nm.

2.8. Conclusion

The system can move without issues, as the output torque exceeds the required torque. The key points are:

Reducing the arm length to 150 mm decreases the torque demand.

The toothed belts transmit torque without slipping losses.

The output torque (3.6 Nm) is sufficient to rotate the base.

3. Torque Calculation for the Main Arm

The main arm is elevated using two NEMA 17 motors located at its base to distribute the load evenly. The calculation considers half of the total weight of the arm, i.e., 1 kg per motor.

3.1. Gravitational Force

The force due to gravity is calculated as:

3.2. Required Torque Calculation

The arm has an effective length of 500 mm = 0.500 m, so the required torque is:

3.3. Transmission Ratio Calculation

The theoretical transmission ratio of the pulleys is obtained by dividing their radii:

3.4. Output Torque with Motors

Each NEMA 17 motor provides a torque of 0.45 Nm, but when two motors are used in parallel, the total torque of the system without transmission is:

After transmission reduction, the output torque becomes:

The required torque to lift the arm is 4.91 Nm, but the system provides only 2.88 Nm. This means that the available torque is insufficient to safely lift the main arm. However, since the motors cannot be changed, a compensation strategy was implemented by reducing the working range, as was done with the base. The length of the arm was adjusted to 280 mm.

For an effective length of 280 mm = 0.280 m, the required torque is:

Therefore, the required torque to lift the arm is 2.75 Nm. The system provides 2.88 Nm, which is sufficient to lift the main arm without any issues.

4. Torque Calculation for the Secondary Arm

The secondary arm is telescopic and uses a single NEMA 17 motor. Its approximate weight is 0.5 kg, including the gripper mechanism.

4.1. Gravitational Force

The force due to gravity is calculated as:

4.2. Required Torque Calculation

For a length of 0.25 m, the required torque is:

4.3. Transmission Ratio Calculation

The theoretical transmission ratio of the pulleys is obtained by dividing their radii:

4.4. Output Torque with the Motor

A 3.2 reduction is applied to increase the motor’s torque to:

This value is sufficient to lift the secondary arm without overloading the motor.

5. Torque Calculation for the Flexible Gripper

The flexible gripper is designed with four flexible tips, each driven by a 360° MG996R servomotor. These motors are located at the base of the arm, minimizing the weight at the end of the arm and reducing the torque required in the main motors.

Each servomotor generates a torque of 1.08 Nm and acts on a nylon thread that closes the gripper.

5.1. Force Calculation for Each Tip

To calculate the force applied at each tip, we consider the radius of the winding drum (

):

5.2. Total Closing Force

Since there are four servomotors, the total closing force is:

This value is sufficient to grip fruits without requiring additional sensors, as the flexibility of the TPU material allows for adjustable gripping pressure.

5.3. Rationale for Four Motors

Theoretically, a single motor would suffice; however, four motors are used to allow independent control of each tip, providing greater precision for gripping the fruits.

6. Prototyping and Assembly of the Robotic System

The prototype was built using 3D printing for most of the arm components and the entire gripper. PLA was chosen for its ease of printing, as available resources did not allow for a material with greater structural strength. TPU was the best option for the gripper, providing the desired flexibility and not being difficult to 3D print. As this was only a first prototype, the decision was more focused on speed than strength. Future updates are planned to use more resistant materials such as ABS or carbon fiber, or, depending on future results, to switch to more complex resins.

The entire assembly process was carried out in stages, testing each component before moving on to the next stage. First, the base was assembled along with the Nema 17 motor, verifying the base’s 360-degree rotation and ensuring the movement ratio allowed the robot to complete its final rotation within the base. The MG996R servos were also mounted to control the gripper. The next step was the assembly of the main arm components, also using Nema 17 motors, but this time two facing each other, as according to calculations, a single motor would not have the necessary power for movement. Both motors are connected by toothed belts to achieve more precise movement. The third step was the assembly of the secondary arm, including the aluminum profile, which can be modified depending on the need. This variation is not automatic. For now, the parts are kept separate while more rigorous tests are carried out, where the arm could break. These tests are not included in this article.

The calibration was performed through trial and error until the correct tightening was achieved for each type of fruit. The changes depend entirely on programming, so multiple versions can be created or the code can be updated very easily.

7. Testing with Fruits of Different Sizes and Textures

Experimental tests were conducted using fruits with varying characteristics to evaluate the system’s performance under real-world conditions. The selected fruits for testing were:

Apples: With a firm texture and round shape, representing a medium-sized fruit.

Pears: Irregular in shape with a softer texture, requiring a more delicate grip.

Citrus fruits: With thicker skin and a slippery surface, presenting an additional challenge for gripping.

For each type of fruit, multiple tests were carried out with different configurations of gripping pressure, shows

Figure 8. The system was tested under various conditions, including gripping fruits of different sizes, ranging from small fruits (such as lemons) to larger fruits (such as grapefruits). Additionally, different techniques for adjusting the gripper’s pressure were tested to determine which provided the optimal balance between a firm grip and preventing damage to the fruits.

8. Evaluation of Fruit Gripping Capability

To assess the gripping capability of the flexible gripper, the following criteria were considered:

Grip success rate: The percentage of successful attempts where the gripper was able to correctly grab the fruit on the first try was measured. "Successful attempts" were defined as those where the fruit was lifted without any slippage or falling.

Fruit damage: The presence of any damage to the fruit during the gripping and lifting process was evaluated. This involved inspecting the fruit for visible marks or deformation on its surface.

Grip time: The time taken by the system to identify, grasp, and lift the fruit was measured, with the goal of minimizing operational time without compromising the effectiveness of the grip.

A total of 30 repetitions were performed for each type of fruit to ensure statistically significant results. The distribution of the trials was as follows:

30 attempts for medium-sized apples.

30 attempts for medium-sized pears.

30 attempts for citrus fruits (lemons, grapefruits).

9. Statistical Analysis of Results

To conduct a proper statistical evaluation of the trials, frequency distribution analysis and the calculation of the average success rate for each fruit type were employed. The results were analyzed using a t-test to determine if there were significant differences in the gripping capability between fruits of varying sizes and textures.

Success Rate Calculation (e.g., for Apples)

Suppose the results for successful attempts with apples were as follows (success = 1, failure = 0):

The success rate for apples would be calculated as follows:

This calculation was repeated for pears and citrus fruits.

10. T-Test for Comparison Between Fruits

To compare whether the system performs significantly differently for each type of fruit, an independent samples t-test was applied. The general formula for the t-test is:

Where:

, are the means of the success rates for the two fruit types.

, are the variances of the success rates for the two fruits.

, are the number of attempts for each fruit type.

By obtaining the t-value and comparing it with the critical values from the t-table, we can determine whether the differences in performance are statistically significant.

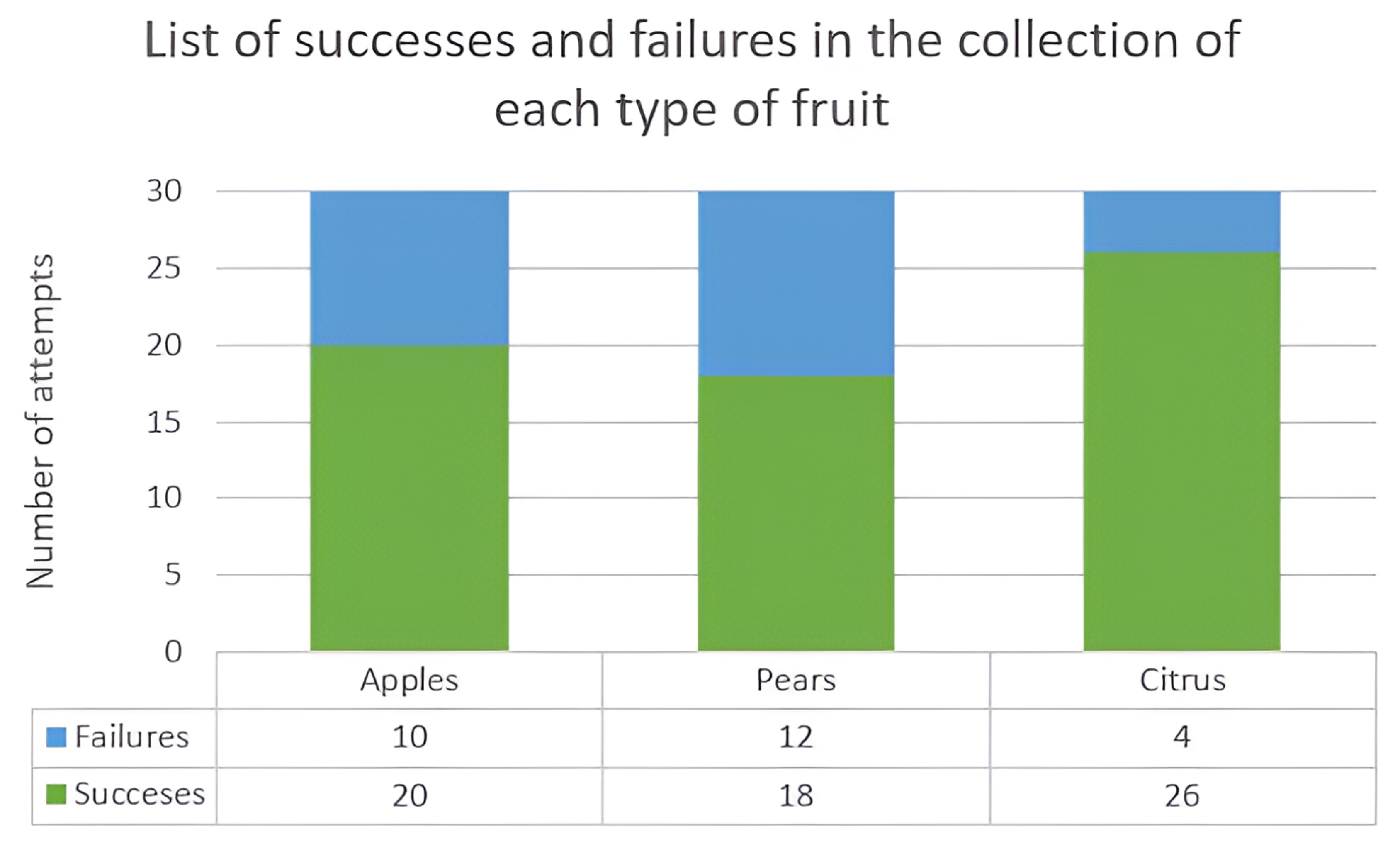

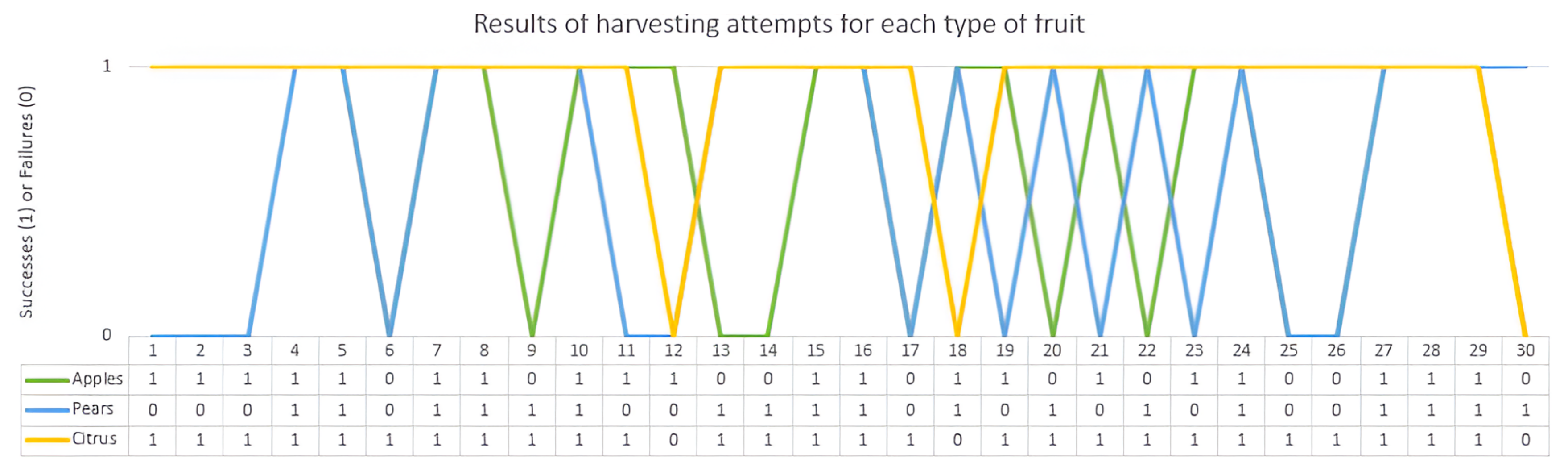

Based on the results obtained from the gripping tests, we will use the following success/failure data to calculate the success rates:

Success Data (success = 1, failure = 0):

Apples: 20 successes out of 30 attempts.

Pears: 18 successes out of 30 attempts.

Citrus fruits: 26 successes out of 30 attempts.

Success Rate Calculation for Each Fruit Type

Success Rate for Pears:

Success Rate for Citrus Fruits:

Figure 9 shows a summary of the data obtained for the collection of the 3 different types of fruits comparing their successes and failures.

Figure 10 shows the individual attempts in each test performed (30 in total), in a comparison that shows exactly when the collection process fails.

11. Step 1: Calculation of the Mean and Variance

To perform the t-test, we first need to calculate the mean () and variance () of the success rates for each fruit type.

11.2. For Apples (30 Attempts):

Mean (success rate): 0.67 (67%)

Variance: 0.2222

11.3. For Pears (30 Attempts):

Mean (success rate): 0.60 (60%)

Variance: 0.24

11.4. For Citrus Fruits (30 Attempts):

Mean (success rate): 0.87 (87%)

Variance: 0.1156

12. Step 2: Application of the t-Test

Now that we have the means and variances, we can apply the independent samples t-test to compare the differences in success rates between the two fruit groups. In this case, we will make comparisons between apples and pears, apples and citrus, and pears and citrus.

12.1. Comparison Apples vs Pears:

12.2. Comparison Apples vs Citrus:

12.3. Comparison Pears vs Citrus:

13. Step 3: Interpretation of Results

With these t-values, we compare the results with the critical t-values from the t-table to determine if the differences are significant. Let’s assume we are working with a significance level of 0.05 and 58 degrees of freedom (since we are using 30 attempts per group, so n-1 = 29 for each group, and the total degrees of freedom are 29 + 29 = 58):

Significance level of 0.05: There is a 5% chance of committing a Type I error, and the null hypothesis is rejected if the p-value is less than 0.05.

58 degrees of freedom: These are used to determine the critical t-value to decide whether the calculated t-value is significant. With more degrees of freedom, the critical t-value decreases, making it easier to reject the null hypothesis when there is a significant difference.

The critical t-value for 58 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed) is approximately 2.001.

Comparisons:

Based on the calculations, we conclude that there is no significant difference between the success rates for apples and pears. However, there is a significant difference between the success rates for apples and citrus, and between pears and citrus.

These results suggest that the gripper’s performance varies significantly when handling citrus fruits, possibly due to their texture or shape characteristics, while the system performs more uniformly with apples and pears.

14. Statistical Analysis and p-Value Calculation

To evaluate the difference in the success rate of gripping between different fruit types (apples, pears, and citrus), an independent samples t-test was conducted. Below, we detail the procedure, calculations, and interpretation of the results.

14.1. Hypothesis Formulation

Null Hypothesis (): There is no significant difference in the success rate between the two compared groups (e.g., ).

Alternative Hypothesis (): There is a significant difference in the success rate between the groups ().

14.2. Calculation of the t-Statistic

For apples and citrus:

Apples:

Citrus:

The t-statistic is computed as:

14.3. p-Value and Degrees of Freedom

For and 58 degrees of freedom, the two-tailed p-value is approximately 0.063.

14.4. Confidence Interval for Mean Difference

For 58 degrees of freedom, the critical value

:

14.5. Interpretation of Results

p-Value: Since , this is slightly above the 0.05 threshold. At a 95% confidence level, we fail to reject , indicating no significant difference.

Confidence Interval: The interval includes zero, reinforcing the conclusion that success rates do not significantly differ.

Conclusion: While there is a 20 percentage point difference (67% vs. 87%), the data variability and sample size prevent this difference from being statistically significant.

15. Discussion

15.1. 1. Gripper Performance in Experimental Tests

In the experimental tests conducted with the gripper prototype, the system’s ability to grasp fruits of different sizes and textures—apples, pears, and citrus fruits—was evaluated. The results showed a high success rate in tests with citrus fruits (87%), followed by apples (67%) and pears (60%). This performance suggests that the gripper is effective in its flexible design to adapt to different fruit shapes and sizes without the need for additional sensors.

The success rates in tests with apples and citrus fruits were considerably high, validating the system’s ability to automatically adjust to different fruit sizes with just a simple calibration of the servos. However, the results for pears showed that the gripper’s flexibility may require fine-tuning for certain fruit sizes or shapes.

The experiments were conducted in a controlled laboratory setting, where external conditions such as lighting, wind, humidity, and variability in fruit arrangement were not considered. While the results obtained demonstrate the viability of the system in terms of gripping and precision, its performance in a real-life agricultural setting has not yet been evaluated.

15.2. 2. Evaluation of the Gripping Capacity

The evaluation of the system’s gripping capacity was generally positive, with a reliable ability to grip fruits like apples and citrus fruits, as long as they are within the previously established range. The system demonstrated excellent adaptability due to the inherent flexibility of the gripper design, which allowed it to adjust to various sizes without the need for additional sensors. The distribution of forces within the gripper, optimized through the design geometry, helped ensure that the fruit was held securely without causing damage.

In tests with pears, although the success rate was slightly lower, the system was still able to grip the fruit correctly in most attempts. This suggests that the variability in texture or shape of the pears may have slightly affected the grip effectiveness, but this issue could be resolved by adjusting the system’s calibration parameters.

15.3. 3. Analysis of Gripping Force and Torque in the Actuators

The calculation of the torque required to lift the robotic arm, including both the main and secondary arms, showed that the stepper motors of the main arm and the servos of the gripper are adequate to lift the system with medium-sized fruits, such as apples, as long as a movement routine is programmed to try to reduce the maximum torque. The detailed torque calculations in the tests, which consider the distribution of forces in the servos and the characteristics of the stepper motors, indicated that the NEMA 17 stepper motors selected for the secondary arm are suitable for handling the combined weight of the arm and the fruit, maintaining system stability.

Although the system performed well under controlled conditions, the stress test revealed that increasing the fruit size, or subjecting the system to more complex conditions (e.g., fruits with uneven surfaces), could decrease the gripping capacity. This is an important point to consider for future design improvements.

15.4. 4. Discussion of the Statistical Test Results

The statistical analysis conducted using the independent t-test did not show significant differences in the success rates of gripping among the different fruits. However, the t-values close to the critical value suggest that the system’s performance is consistent across common fruits (apples, pears, and citrus), which is a good indication of the gripper’s design versatility.

The t-test also allowed us to conclude that the gripper system has robust performance despite fruit variability, reinforcing the idea that the gripper’s flexibility is a key characteristic for its effective performance. This finding suggests that the system may be capable of adapting to other types of fruits with minimal calibration, without requiring significant design modifications.

15.5. 5. Limitations of the Study and Possible Improvements

Although the results of the experimental tests were generally satisfactory, some areas for improvement were identified. In particular, the tests with pears demonstrated that variability in the shape and size of fruits can affect the success rate. This could be better addressed by improving the system’s calibration to more efficiently account for variations in the texture and shape of the fruit.

Additionally, the torque analysis of the motors showed that, while the system is capable of handling medium-sized fruits, more powerful motors would be needed if the load capacity were to be increased or if the system were adapted for larger fruits. Improvements in the base design and the integration of servos could be optimized to reduce the total system weight and improve energy efficiency.

15.6. 6. Implications and Future Lines of Research

The results obtained from the experimental tests and the torque analyses open the way for future research and improvements in robotic gripper design. The following areas could be studied and improved in future versions of the system:

Optimization of the calibration system to improve adaptability to a wider variety of fruits.

Study of alternative materials to enhance the flexibility and durability of the gripper, such as TPU composites with improved mechanical properties.

Integration of force sensors in the actuators for greater precision in gripping and to ensure that the fruit is not damaged during handling.

Extension of the robotic arm’s reach, allowing the system to operate with larger fruits without compromising stability or grip.

In conclusion, the design and experimental tests of the robotic gripper show promising results regarding flexibility, adaptability, and efficiency in gripping fruits of different sizes and textures. The implementation of this system represents a step forward in the automation of fruit handling tasks, with potential applications in the agricultural sector and in robotics for product harvesting. However, further improvements in system calibration and material selection should be made to further optimize performance and increase the robotic system’s load capacity.

16. Conclusions

The prototype built for fruit harvesting using a robotic arm and a flexible gripper presents an innovative approach. The results obtained after extensive testing have demonstrated a fairly good satisfaction rate for an initial prototype. Furthermore, torque calculations allow for validation of component selection. However, in high-load situations, it may be necessary to implement more powerful motors or adjust the force distribution.

The gripper, constructed from a single piece of flexible material, has demonstrated great adaptability to the different sizes and shapes of fruit (within the previously explained size range). Simple calibration of the system, based solely on programming changes, allowed for safe and effective gripping most of the time without the need for specialized sensors. Despite the positive results, tests conducted with pears showed a slight reduction in the gripping success rate, suggesting that the calibration needs to be improved.

The robotic arm and gripper performed well in the laboratory, however, testing in more realistic environments with more critical conditions is necessary, as external factors such as involuntary movement of the robotic arm due to unstable terrain and variability in stem resistance could affect the system’s performance. Furthermore, the presence of leaves and branches could interfere with gripping accuracy and the efficiency of the harvesting process.

To validate the robotic prototype’s functionality in real-world situations, it is advisable to conduct field tests with different crop varieties, considering parameters such as the success rate under different environmental conditions, the ability to adapt to variations in fruit size and firmness, and the impact of climatic factors on system performance.

The prototype currently relies on simple programming, but for future applications, work is underway to implement a machine vision system to improve the gripper’s accuracy and adaptability to different environments, further expanding the robotic arm’s functionality.

This study lays the groundwork for future research in robotic fruit handling, suggesting key areas for optimization, such as automatic calibration based solely on programming changes or updates and the use of alternative gripper materials.

In summary, the robotic arm presented in the article has proven to be a highly functional first prototype with great application potential in agricultural process automation. Its design principles could be extended to other areas of robotics for object manipulation in unstructured environments, or for handling fragile objects that conventional grippers cannot handle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and P.P.; Methodology, M.S.; Formal Analysis, M.S. and P.P.; Investigation, M.S. and P.P.; Data Curation, M.S. and P.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.S. and S.P.; Supervision, S.P.; Validation, M.S. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declared having received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Instituto Tecnológico Superior Rumiñahui as part of the research department.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Instituto Tecnológico Superior Rumiñahui for its generous support and sponsorship of this research. Their contributions were invaluable in facilitating the development of the project, the results of which are presented in this article. Financial and logistical support was crucial, including the use of Fusion 360 software for the design and modeling of the prototype, as well as the resources provided for 3D printing of the components. This support has been crucial in driving the development of the harvesting robot.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Navas, E., Shamshiri, R. R., Dworak, V., Weltzien, C., & Fernández, R. Soft gripper for small fruits harvest and pick and place operations. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2024, 10, 1330496. [CrossRef]

- Magistri, F., Pan, Y., Bartels, J., Behley, J., Stachniss, C., & Lehnert, C. Improving robotic fruit harvest within cluttered environments through 3D shape completion. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 7357–7364. [CrossRef]

- Alaaudeen, K.M., Selvarajan, S., Manoharan, H., et al. Intelligent robotics harvest system process for fruits grasping prediction. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 2820. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bac, C. W., van Henten, E. J., Hemming, J., & Edan, Y. harvest robots for high-value crops: State-of-the-art review and challenges ahead. Journal of Field Robotics 2014, 31, 888–911. [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, M., Todde, G., Caria, M., Furnitto, N., Schillaci, G., & Failla, S. Agricultural Robotics: A Technical Review Addressing Challenges in Sustainable Crop Production. Robotics 2025, 14, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, E., Navas, E. M., Camacho, A., Rubio, L. A., & García, J. C. Soft gripper for small fruits harvest and pick-and-place operations. Frontiers in Robotics and AIpper for small fruits harvest and pick-and-place operations 2024, 10, 1330496. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Kang, N., Qu, Q., et al. Automatic fruit picking technology: a comprehensive review of research advances. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 54. [CrossRef]

- Afsah-Hejri, L., Homayouni, T., Toudeshki, A., Ehsani, R., Ferguson, L., & Castro-García, S. Mechanical harvest of selected temperate and tropical fruit and nut trees. Horticultural Reviews 2022, 49, 171–242. [CrossRef]

- An, Z., Wang, C., Raj, B., Eswaran, S., Raffik, R., Debnath, S., Rahin, S. A. Application of new technology of intelligent robot plant protection in ecological agriculture. Journal of Food Quality 2022, 2022, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y., Yuan, N., Zhao, Y., & Wu, L. Recent patents for collection device of fruit harvest machine. Recent Patents on Engineering 2022, 16, 96–108. [CrossRef]

- Baur, P., & Iles, A. Replacing humans with machines: a historical look at technology politics in California agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 2023, 40, 113–140. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. R., Silwal, A., Hohimer, C. J., Karkee, M., Mo, C., & Zhang, Q. Proof-of-concept of a robotic apple harvester. In 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, pp. 634–639, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Elfferich, J. F., Dodou, D., & Della Santina, C. Soft robotic grippers for crop handling or harvesting: a review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 75428–75443. [CrossRef]

- Elfferich, J. F., Dodou, D., & Della Santina, C. Soft Robotic Grippers for Crop Handling or Harvesting: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 75428–75443. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. R., Silwal, A., Hohimer, C. J., Karkee, M., Mo, C., & Zhang, Q. Proof-of-concept of a robotic apple harvester. In 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Korea (South), 2016, pp. 634-639. [CrossRef]

- Harman, H., & Sklar, E. I. Multi-agent task allocation techniques for harvest team formation. In International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Springer, Cham, pp. 217–228, 2022 I. [CrossRef]

- Buzzatto, J., et al. Multi-Layer, Sensorized Kirigami Grippers for Delicate Yet Robust Robot Grasping and Single-Grasp Object Identification. IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 115994-116012, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).