1. Introduction

Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) are a group of intestinal parasitic worms that infect humans through contaminated soil containing eggs from human feces. The most important STHs include the giant roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), the whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), and the hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus), affecting approximately 24% of the world's population (~1.5 billion people), particularly in the subtropical and tropical regions of Africa, South Asia, and South America [

1]. The incidence of these diseases is closely linked to poor socio-economic conditions, such as inadequate access to clean water and sanitation, poor hygiene, overcrowding, and insufficient waste management, as well as environmental and climatic factors (e.g., temperature, humidity, and soil variables) that favor the survival of the worm eggs and larvae in the soil [

1,

2]. The most vulnerable groups to STH infections are women of childbearing age, preschool children, and school-aged children [

2,

3]. The diseases cause significant morbidity to the community, ranging from physical and cognitive growth impairment, poor pregnancy outcomes, anemia, to surgical complications such as intestinal obstruction [

2].

The WHO-recommended control strategy of these infections includes improving water availability, safety, and hygiene. Large-scale deworming through mass drug administration is another equally significant public health intervention for vulnerable groups [

4]. The frequency of deworming, whether annually or biannually, is guided by the baseline disease prevalence in an area [

4].

The lifecycle of soil-transmitted helminths begins with the sexual reproduction and egg laying by adult worms in the host’s small intestine for roundworms and hookworms, or the colon for whipworms. Adult worms lay thousands of eggs per day that are released with stools. When stool contaminated with these parasite eggs is deposited on the soil, the eggs of Ascaris and Trichuris can remain viable for months under favorable conditions and subsequently enter the human host through the consumption of egg-contaminated food or water [

5]. In contrast, hookworm eggs hatch in soil into larvae that remain viable for weeks and can enter the human host through direct skin penetration, where they migrate to desirable sites and mature into adults that lay eggs [

1,

5]. The clinical presentations of STH are variable, and can be categorized as (i) those resulting from reactions to worm entry (hookworm larvae) that include skin rash and itching; (ii) reactions to larva migration which may include: pulmonary symptoms like coughing, sneezing, bronchitis and pneumonia, and (iii) due to presence of adult worm in the intestines that may include intestinal symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; anemia, malnutrition, stunting, impaired growth to more severe cases such as intestinal obstruction for A. lumbricoides [

1].

The microscopic demonstration of parasite eggs in stool is the primary method for detecting STH infections. Various methods have been developed to demonstrate eggs on stool, including wet mount preparation, Kato-Katz thick smear, and centrifugation-based techniques like the formal ether/ethyl acetate concentration technique. Newer commercialized innovations include the flotation-based methods such as McMaster technique and FLOTAC/Minin-FLOTAC methods [

6,

7]. Additionally, other diagnostic techniques include serology-based, molecular-based, and culture-based methods [

7].

Today, the Kato-Katz thick smear is the diagnostic standard recommended by the WHO for diagnosing STH infections. This technique involves sieving stool samples and placing a small portion—approximately 1/24 gram – on glass slides using a template. The sample is then covered with glycerol-soaked cellophane and gently pressed to create a thin smear, which is examined under a microscope. While this method uses a minimal amount of stool, it has low sensitivity, especially for low-intensity infections unless multiple samples or smears per slide are analyzed [

7,

8,

9].

Advancements in STH control programs are expected to lead to more people experiencing low- and moderate-intensity infections [

4,

10]. These typically asymptomatic infections can serve as reservoirs for disease spread if not promptly detected and treated [

8]. This underscores the need for highly sensitive diagnostic methods to identify these cases. In this regard, the µFlow group at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) designed and developed the Single Imaging Parasite Quantification (SIMPAQ) device, which is a lab-on-a-disk (LoD) technology that concentrates and traps parasite eggs using two-dimensional flotation by combining centrifugation and flotation forces [

9]. This occurs by adding a saturated sodium chloride flotation solution to the stool sample, which is slightly denser than parasite eggs, causing the eggs to float while most of the stool particles sediment, thus isolating eggs from debris. Subsequently, centrifugation of the disk directs the eggs toward the center of the disk, where they are packed into a monolayer on a converging imaging zone called the Field of View (FOV), allowing for single-image capture using a digital camera, which facilitates immediate digitalization of the data [

9,

11].

It is potentially a portable, point-of-care, reusable device that requires only a small amount of stool sample (1 g) and utilizes inexpensive, readily available materials for testing. The technique has a short time-to-results and demonstrates a strong positive correlation (0.91) with the commercially available Mini-FLOTAC method, with the ability to detect low egg count samples as low as 30 to 100 eggs per gram of feces [

9].

Field tests using animal samples (pigs and dogs) to compare the device’s performance against McMaster and flotation methods showed that it was able to correctly detect over 93% of the positive cases (sensitivity 91.39-95.63% against McMaster and 91.00-95.35% against flotation method) and could detect eggs in negative samples using the reference techniques, signifying its promising potential as a diagnostic tool in settings of low-and-moderate infection intensities [

12].

In a field test of the device using human samples in an STH endemic area (Northern Tanzania), the device demonstrated high specificity and negative predictive values compared to existing recommended tests: the Kato Katz thick smear and formal ether concentration tests [

10]. However, it exhibited low sensitivity due to significant egg loss that occurs during sample preparation steps [

10], a phenomenon also observed by Sukas et al. [

9]. Nevertheless, the exact points of loss and the quantification of egg loss remain unknown. Moreover, when assessing the disk's capture efficiency, despite significant egg movement towards the disk's center, most did not reach the imaging zone and remained in various locations within the flow chambers. Around 22% of 71% of eggs that reached the chip were successfully trapped in the imaging zone, thus necessitating examination of the whole disk in multiple locations and taking multiple pictures to obtain an exact fecal egg count in a sample, thereby increasing time-to-results [

9].

Factors that hindered successful entry of eggs into the FOV included (i) the presence of additional inertial forces- Coriolis and Euler forces that cause deflection of the path of eggs especially near the center of rotation where centrifugal force is small resulting in collision of the eggs with or sticking to the lateral walls, moving in zig zag pattern or even backwards instead of moving towards the FOV lowering the capture efficiency [

13]. Additionally, (ii) the presence of larger fecal debris that passes through the 200 μm filter membrane in the disk hinders the egg entry to the imaging zone. Attempts to improve the disks' capture efficiency have been in place, including changes in the disk design. This has been done by reducing the length of the channel from 37 mm in the initial designs to 27 mm to minimize the effects of the additional Coriolis and Euler forces. Additionally, surfactant has been added to flotation solution to reduce adherence of eggs to the walls of syringes and disk and testing of different centrifugation speeds to identify ideal rotation speed that will give the highest yield [

11].

In this paper, we focus on the protocol improvement to (i) quantify and decrease egg loss occurring during the sample preparation steps, and (ii) improve the capture efficiency of the disks at the Field of View by improving the working protocol of testing samples. To achieve this, we conducted experiments using polystyrene red particles as models for STH eggs and actual STH eggs preserved in ethanol spiked in goat and human stool samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Disk Description and Imaging Set-Up

The SIMPAQ disk is a circular plastic device made of poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) with a diameter of 10 cm. It features two diagnostic chambers, each measuring 27 mm in length. These chambers have a sloping depth that decreases from the outer edge towards a rectangular area indicated as the FOV, which is designed to collect and image eggs. The depth of the FOV ranges from 60 to 100 μm and is specifically designed to trap worm eggs (60 and 100 μm), in a monolayer. The dimensions of the FOV are 1.77 mm by 3.00 mm, which align with the image capture settings to enable a single image capture of the results (

Figure 1A).

The imaging system features a digital Sony α6100 camera (Sony Group Corporation, Minato, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a Samyang 2.8/100 mm macro lens (Samyang Optics, Masan, South Korea). This macro lens is attached to a 10x magnification objective lens through an adapter. To improve visibility during results analysis, we use a halogen light source (Quartz Tungsten-Halogen lamp, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) (

Figure 1B).

2.2. Flotation Solution and Polystyrene Particles

A flotation solution of density 1.2 g/ml was used in these experiments by dissolving NaCl salt in distilled water (Millipore Synergy UV, Spectralab Scientific lnc., Markham, ON, Canada). A 0.05% Tween-20 solution was also added to the flotation solution, serving as a surfactant to reduce the adherence of polystyrene particles and eggs to the apparatus used. Polystyrene (PS) particles (Microparticles GmbH) diluted in distilled water at a 20 particles/µL concentration were used as models for worm eggs in these experiments. The particles have a diameter of 59.8 µm and a density of 1.05 g/mL, which is comparable to the helminth eggs: Ascaris eggs (dimensions: 45 to 75 µm-fertilized and up to 90 µm-unfertilized; density: 1.11 g/ml), hookworm eggs (dimensions 60-75 µm by 35-40 µm.; density: 1.055 g/mL), and Trichuris eggs (dimensions: 50-55 µm by 20-25 µm; density: 1.15 g/mL) [

11,

14,

15,

16].

2.3. Stool Samples and Purified Helminth Eggs

Both worm-negative goat and human stool samples were used in these experiments. The human stool samples were obtained from Tanzania, whereas the goat stool samples were obtained from Ghent University. To quantify the improvement of the protocol and capture efficiency, a known number of polystyrene particles (10, 25, 50, and 100) and worm eggs were spiked in the stool samples. These eggs were purified from human stool collected during a worm expulsion study in Pemba Island (Tanzania). For each load, the tests were done in triplicate.

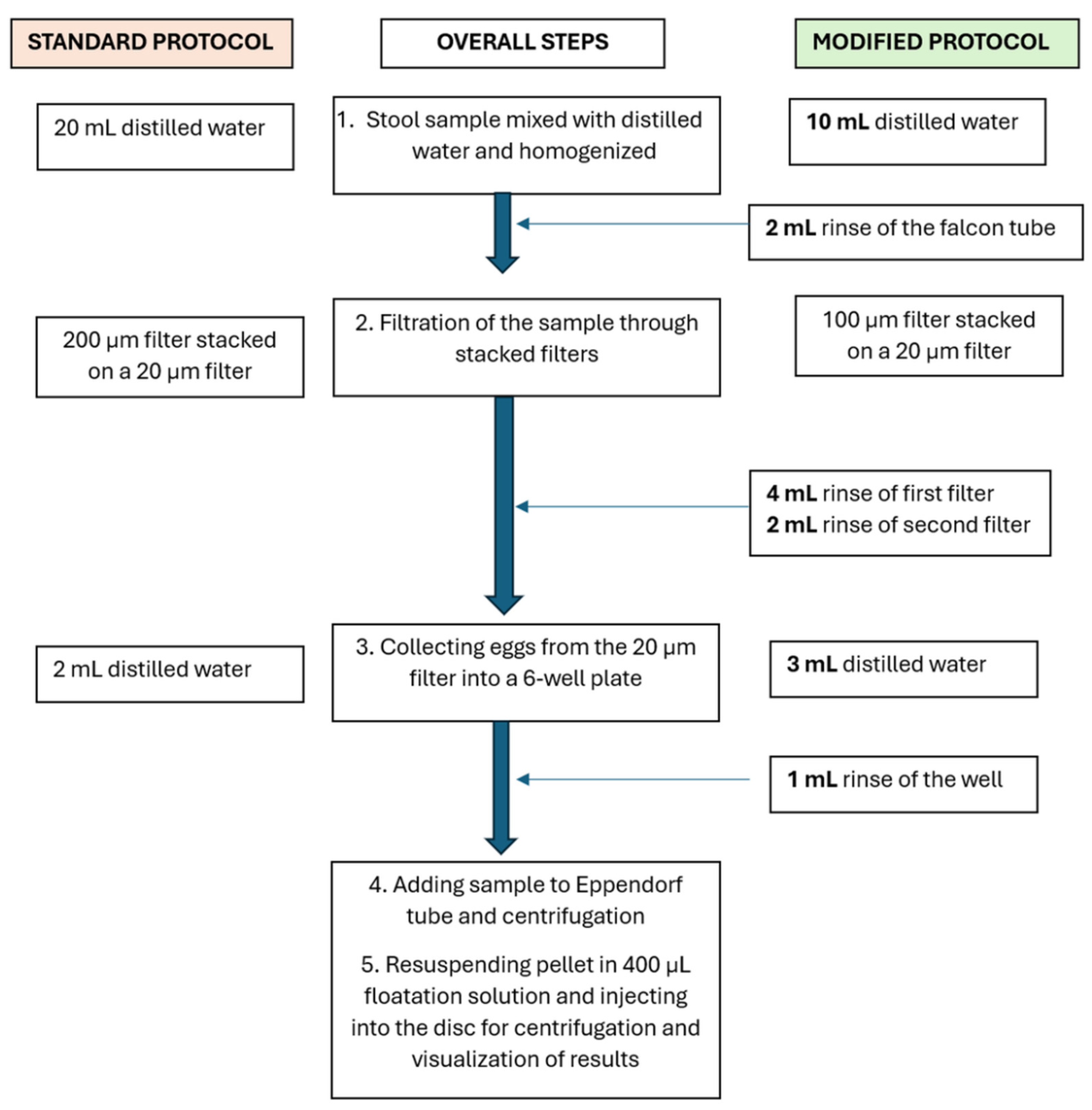

2.4. Stool Sample Analysis Using the Standard Protocol

In the standard SIMPAQ protocol, 1 g of stool sample was mixed with 20 mL of distilled water in a 50 mL Falcon tube and homogenized using plastic granules (Apacor) followed by filtration through stacked polyethylene terephthalate (PET) filters (pluriStrainer®), 200 µm and 20 µm pore size. Eggs were then rinsed from the 20 µm filter surface using 2 mL distilled water, which was collected in a 6-well plate and then transferred to 2 mL Eppendorf tubes for centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 3 min. The obtained pellet was resuspended in 400 µL of flotation solution and injected into the disks using a 1 mL syringe, where they were centrifuged again at 5,000 rpm for 5 min [

9].

The capture efficiency of the disks was calculated as the percentage of eggs in the disk that are in the Field of View.

3. Results

3.1. Protocol Improvement to Enhance Particle Retention in Samples During Preparation

The sensitivity of the SIMPAQ diagnostic disk is reduced due to the significant loss of eggs that occurs during the sample preparation steps [

9,

10]. To quantify this loss, spiked goat and human stool samples (100 PS particles) were examined using the standard protocol. The materials used in the test—that is, Falcon tubes, filters, 6-well plates, and Eppendorf tubes—were analyzed under the imaging setup to determine the number of particles remaining attached to their surfaces (done in triplicate for each sample). It was found that, on average, around half of the spiked particles – 57.0% (±11.6% SD (standard devialtion)) in goat stool remained in the materials used. Therefore, only 43.0% (±7.0%) of spiked particles reached the disk. For human samples, 47.3% (±8.2%) of the particles remained in the materials, hence, only 52.7% (±6.8%) of spiked particles reached the disk. Most of the particles were located in the first filter, with 32.0% (±6.6%) for goat samples and 23.7% (±8.6%) for human samples (

Table 1). This difference in retention can be attributed to variations in stool consistency between goats and humans. Goat stool tends to contain coarser and larger debris, which can more effectively trap polystyrene particles.

To address these challenges, the standard protocol was then modified. Instead of mixing the stool samples with 20 mL of distilled water for homogenization, only 10 mL of water was used initially to homogenize the stool sample. The remaining 10 mL was used for washing steps, distributed as follows: 2 mL in the Falcon tube, 4 mL in the first filter, 2 mL in the second filter, and 2 mL in the 6-well plate (

Figure 2). Additionally, 100 µm filters were utilized as the first filters instead of the 200 µm filters used in the standard protocol to minimize the amount of stool debris that are is collected at the second filter and thus introduced in the disk, subsequently interfering with particles and egg movement in the disk.

Each of the stool samples from goats and humans was spiked with 100 PS particles and tested using these modifications. The tests were done in triplicate. Incorporation of washing steps improved the number of particles that reached the disk. Specifically, for goat stool samples, the effectiveness increased from 43.0% (±7.0%) to 71.3% (±4.7%), and for human stool samples, it rose from 52.7% (±6.8%) to 76.3% (±8.7%) (

Table 1). Minimizing egg loss during the sample preparation step is crucial, especially when dealing with low intensity infections where the number of eggs per gram faeces is low; that is, 1-4999 for Ascaris, 1-999 for Trichura Trichuris, and 1-1999 for hookworms [

17].

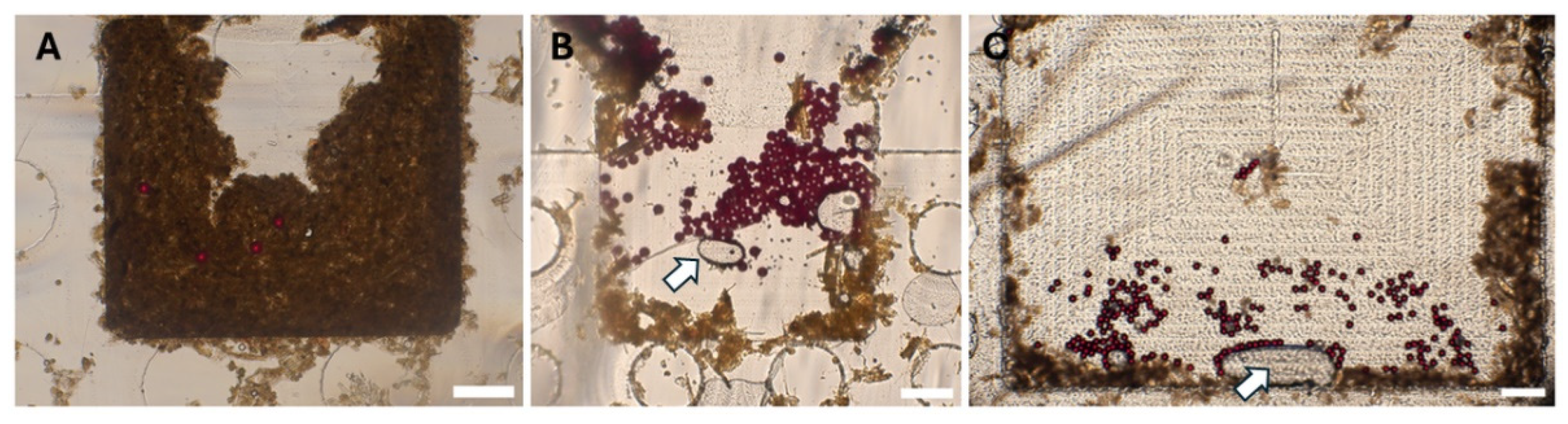

We also aimed to determine the appropriate sample weight to use in our protocol. We tested three starting sample weights (1 g, 0.5 g, and 0.25 g) each spiked with 100 PS and observed the number of residual particles in the sample reaching the FOV and the clarity of the image obtained thereafter at the FOV. For each condition, tests were done in triplicate. The number of residual particles in the sample that reach the FOV increased when using a smaller weight, with 0.25 g giving the highest mean of 66.7 (±7.4) (

Table 2). Similarly, the amount of debris in the FOV decreased when using smaller weights, enabling the obtaining of clearer images hence easy quantification (

Figure 3). Therefore, the amount of stool to be used was set to be 0.25 g. Excess stool debris was observed to cause filter blockage, thus lengthening the filtration time. Additionally, they lead to disk blockage and contribute to poor delivery of eggs to the FOV and leading to poor quality of images of the disks.

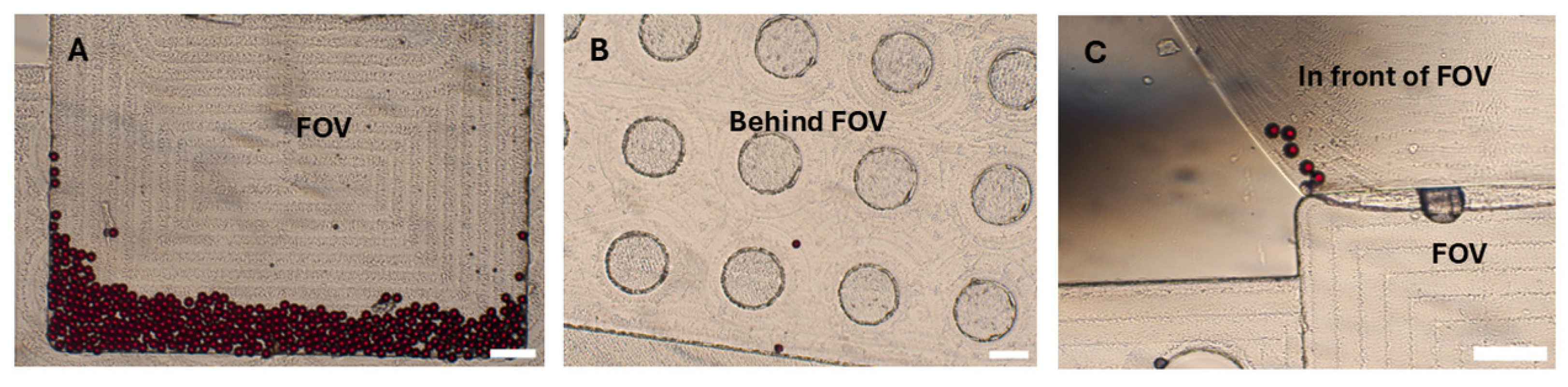

3.2. Polystyrene (PS) Particles Particle Distribution in the SIMPAQ Disk

It has been previously reported that not all eggs that reach the disk are captured within the FOV, necessitating the examination of the entire chamber to obtain an accurate count of eggs in a sample [

9,

10]. We identified three potential locations where eggs or particles may reside within the disk chambers: near the borders of the chamber, the region in front of the FOV, and behind the FOV. To minimize adherence of eggs and PSe particles to the walls of the chamber (both near the borders and in front of the FOV), we used 0.05% Tween-20 as a surfactant. Additionally, the escape of eggs and PS particles behind the FOV can be reduced by selecting disks with appropriate dimensions—, specifically, around 20 µm in depth in this region. This allows only smaller debris and air to pass while physically restricting the escape of eggs from the FOV. Despite these considerations, some particles-17.3% were still occasionally observed in potential locations of the disk, that is: the region in front of the FOV (8.3%), followed by locations near the chamber borders (5.3%) and regions behind the FOV (3.7%) (

Table 3;

Figure 4). Efforts were made to increase the concentration of Tween-20 surfactant in the flotation solution to further prevent particle adherence to the walls. However, this led to the generation of excessive bubbles during disk centrifugation, which ultimately hindered the effective trapping of eggs within the field of viewField of View. Therefore, the concentration was maintained at 0.05%. Furthermore, the disks are fabricated using computer numerical control (CNC) milling (Datron Neo, Datron) from PMMA (Eriks). Achieving precise milling depths, especially for very small depths like those required for our disks, is challenging. This difficulty is influenced by (i) material-based factors—, such as the type of material and inherent surface irregularities, and (ii) machine-based factors, including machine resolution, accuracy, precision limits, and deflections during operation. All these elements can contribute to a lack of exact 20 µm depths behind the FOV [

18]. To mitigate this challenge, one approach used was milling of the PMMA surfaces to create a uniform reference plane prior to milling of the chambers, along with confirmatory depth testing after fabrication using a stylus profilometer (DektakXT, Bruker). However, care must be taken when using these disks to examine the potential locations where eggs may occasionally be found to obtain precise results.

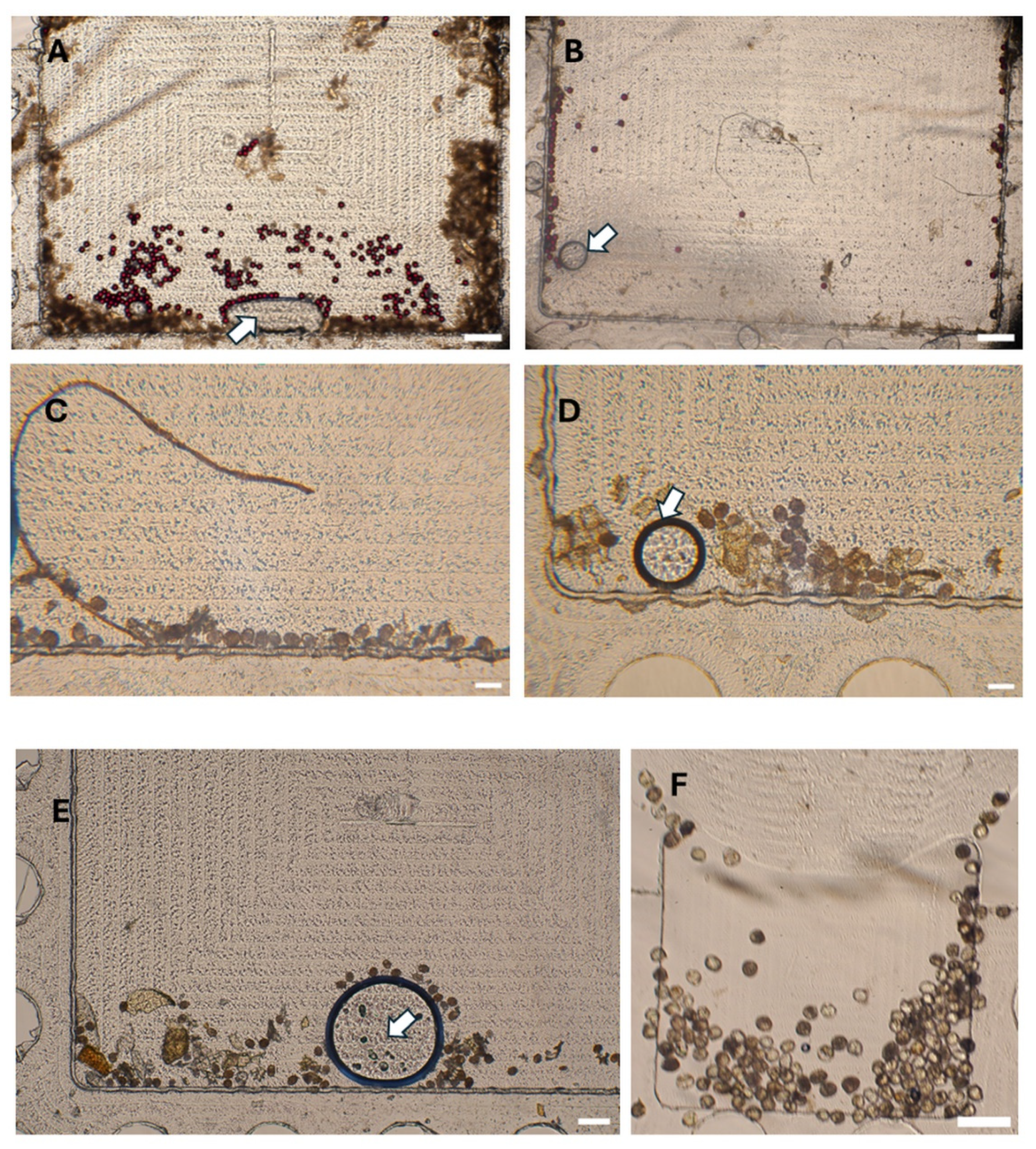

3.3. Capture Efficiency of the SIMPAQ Disks at the FOV

To evaluate the capture efficiency of the disks, that is, the percentage of particles or eggs at the FOV out of the total spiked particles or eggs, we used the modified protocol, and the considerations mentioned above. Two sets of experiments were conducted: in the first experiments, varying numbers of PS particles (100, 50, 25, and 10) were spiked in worm-negative human stool samples. In the second set of experiments, stool samples were spiked with similar variations of purified helminth eggs. The eggs and PS particles were added to the sample, and all preparation steps were carried out according to the modified protocol. Each test was repeated three times. On average, for 100 spiked PS particles, 76.3% (76.3 ±4.0) were at the FOV. We note that such a small number of eggs (particles, in the tests) corresponds to a very low level of infection, and the tests showed a high efficiency of capturing the particles. To go even below that level, in order to examine the lower limit of the infection that can be detected by the device (ultimately targeting at 1 egg), we examined the performance of the disk for near ultra-low levels by spiking 10 particles, where 50.0% (5.0 ±2.6) of them were at the FOV (

Table 4). Similarly, for worm eggs, 73.7% (73.7 ±4.5) of the 100 spiked eggs were in the FOV. This efficiency declines when fewer eggs are spiked in the sample to 60.0% (30.0 ±4.0) for 50 helminth eggs, 48.0% (12.0 ±1.7) for 25 eggs, and 20% (2.0 ±2.0) for 10 eggs (

Table 4). Images obtained at the FOV were clear, and both eggs and particles could easily be counted (

Figure 5). The remaining eggs were distributed in the disk near the chamber borders, in front of the FOV, and behind the FOV.

This is a significant improvement as compared to the previously recorded efficiency observed by Sukas et al. [

9], where around 31% (±25) of eggs in the disk reached the FOV. The successful entry of eggs into the FOV in the early study was limited by several factors, including the presence of larger fecal debris in the disk that hindered the egg entry into the imaging zone. This has been addressed in the current protocol by the use of a filter with smaller pore sizes, i.e., 100 µm instead of the previously used 200 µm filters. Furthermore, the reduction of the amount of stool samples used in the tests – 0.25 g instead of the initial 1 g – helped to reduce the amount of debris reaching the disk.

4. Conclusions

The developed LOD device is a promising technology for the detection of low-intensity STH infections. However, its performance was limited due to egg loss during sample preparation, thus preventing them from reaching FOV. The optimization of the sample preparation protocol proposed in this work was aimed at addressing these limitations. We used both model PS particles and worm eggs to illustrate the improvements during the diagnostic analysis using SIMPAQ disks.

Modifications to the protocol, such as the addition of washing steps, have considerably increased the percentage of polystyrene particles that reach the disk FOV, thus minimizing losses. As a result of these modifications, the percentage of polystyrene particles reaching the FOV after sample preparation steps has risen from 43.0% (±7.0) using the standard protocol to 71.3% (±4.7) for goat samples and from 52.7% (±6.8) for the standard protocol to 76.3% (±8.7) for human samples. The use of finer filters with 100 µm pores instead of 200 µm pores and 0.25 g of stool sample has also significantly reduced the amount of stool debris that reach the FOV, enabling users to obtain clear images at the FOV. Additionally, the use of a surfactant has proven to be effective in minimizing particle adherence within the collection apparatus, further enhancing the delivery of analytes to the disk FOV. As a result of the above improvements, the capture efficiency of helminth eggs at the FOV has significantly increased to 73.7% compared to the previously reported efficiency of 31% (± 25). Additionally, the improvements further showcase the promise of the device in detecting even ultra-low egg intensity, as shown by its current ability to detect 20% of 10 spiked helminth eggs.

Reducing sample loss and improving the disk's capture efficiency enhances the reliability of the diagnostic results. The findings highlight the importance of maintaining strict dimensions of the chamber during disk fabrication. We also stress the need for users to carefully and thoroughly examine the entire chamber to avoid missing any eggs that may be present on the disk. This work establishes a foundation for future field studies in endemic areas for STHs to assess the reliability of our device as a powerful alternative diagnostic tool for helminths.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R.M. and W.D.M.; methodology, V.R.M., M.B., B.L., H.D.M. and W.D.M.; validation, V.R.M. and W.D.M.; formal analysis, M.H.I.W., H.D.C., V.R.M. and W.D.M.; investigation, M.H.I.W., H.D.C., D.K. and V.R.M.; resources, J.V., B.L., H.D.M. and W.D.M.; data curation, M.H.I.W., H.D.C. and V.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.D.C. and V.R.M.; writing—review and editing, H.D.C., V.R.M., B.L. and W.D.M.; visualization, M.H.I.W. and D.K.; supervision, V.R.M., H.D.M. and W.D.M.; project administration, W.D.M.; funding acquisition, W.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the VLIR-UOS South Initiative 2020, TZ2020SIN308A105, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania; VLIR-UOS Short Initiative 2022, ET2022SIN345A105, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Jimma University, Ethiopia; and VLIR-UOS TEAM 2024, TZ2024TEA571A105, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Tanzania.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Soil-transmitted helminth infections [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2025 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections.

- Riaz, M., Aslam, N., Zainab, R., Rasool, G., Ullah, M. I., Daniyal, M., & Akram, M. Prevalence, risk factors, challenges, and the currently available diagnostic tools for the determination of helminths infections in human. European Journal of Inflammation. 2020, 18. https://. [CrossRef]

- Servián, A., Garimano, N., & Santini, M. S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections in South America (2000-2024). Acta Tropica, 2024, 260, 107400. https://. [CrossRef]

- WHO Guideline: Preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550116.

- Brooker, S., Clements, A., & Bundy, D. Global Epidemiology, Ecology and Control of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections. Advances in Parasitology/Advances in Parasitology, 2006, 62, 221–261. https://. [CrossRef]

- Cringoli, G., Maurelli, M. P., Levecke, B., Bosco, A., Vercruysse, J., Utzinger, J., & Rinaldi, L. (2017). The Mini-FLOTAC technique for the diagnosis of helminth and protozoan infections in humans and animals. Nature Protocols, 2017, 12(9), 1723–1732. https://. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S., Singh, S., & Mewara, A. Diagnostic techniques for Soil-Transmitted Helminths – Recent advances. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine, 2021, 12, 181–196. https://. [CrossRef]

- Ngwese, M. M., Manouana, G. P., Moure, P. a. N., Ramharter, M., Esen, M., & Adégnika, A. A. Diagnostic techniques of Soil-Transmitted Helminths: Impact on control measures. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2020, 5(2), 93. https://. [CrossRef]

- Sukas, S., Van Dorst, B., Kryj, A., Lagatie, O., De Malsche, W., & Stuyver, L. J. Development of a Lab-on-a-Disk Platform with Digital Imaging for Identification and Counting of Parasite Eggs in Human and Animal Stool. Micromachines, 2019, 10(12), 852. https://. [CrossRef]

- Mazigo, H. D., Justine, N. C., Bhuko, J., Rubagumya, S., Basinda, N., Zinga, M. M., Ruganuza, D., Misko, V. R., Briet, M., Legein, F., & De Malsche, W. High Specificity but Low Sensitivity of Lab-on-a-Disk Technique in Detecting Soil-Transmitted Helminth Eggs among Pre- and School-Aged Children in North-Western Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2023, 9(1), 5. https://. [CrossRef]

- Misko, V. R., Kryj, A., Ngansop, A.-M.T., Yazdani, S., Briet, M., Basinda, N., Mazigo, H. D., De Malsche, W. Migration Behavior of Low-Density Particles in Lab-on-a-Disc Devices: Effect of Walls. Micromachines, 2021, 12, 1032. https://. [CrossRef]

- Rubagumya, S. L., Nzalawahe, J., Misinzo, G., Mazigo, H. D., Briet, M., Misko, V. R., De Malsche, W., Legein, F., Justine, N. C., Basinda, N., & Mafie, E. Evaluation of Lab-on-a-Disc Technique Performance for Soil-Transmitted Helminth Diagnosis in Animals in Tanzania. Veterinary Sciences, 2024, 11(4), 174. https://. [CrossRef]

- Misko, V. R., Makasali, R. J., Briet, M., Legein, F., Levecke, B., & De Malsche, W. Enhancing the yield of a Lab-on-a-Disk-Based Single-Image parasite quantification device. Micromachines, 2023, 14(11), 2087. https://. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Ascariasis, 2019, DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Hookworm (Intestinal), 2019, DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/hookworm/index.html.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Trichuriasis, 2019, DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trichuriasis/index.html.

- Montresor, A., Crompton, D.W.T., Hall, A., Bundy, D.A.P., Savioli, L. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Schistosomiasis at Community Level: A Guide for Managers of Control Programmes, 1998, World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved April 2, 2025, from https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/63821.

- DATRON Dynamics. 4 ways to ensure consistent depth of cut, 2025, DATRON. Retrieved April 1, 2025, from https://www.datron.com/resources/blog/4-ways-to-ensure-consistent-depth-of-cut/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).