Introduction

In the obstetrics department, caesarean section is the most common surgery. World Health Organization (WHO) research shows that global caesarean section (C-section) delivery has risen to over 21% of all childbirths [

1]. According to a study by the Center for Health Development, the C-section rate in Mongolia has been increasing over the years from 22.4% in 2012 to 25.4% in 2016 [

2,

3]. Anaesthesiologists must decide whether general or regional anaesthesia is optimal for caesarean section delivery based on the specific condition and clinical circumstances of each patient.

A classical method of anaesthesia for C-sections delivery is spinal anaesthesia (SA) and through relevant and rigorous guidelines can be recommended to patients. Spinal anaesthesia is rapid, providing quick onset of bilateral, dense, and reliable anaesthesia using minimal drug dosages with low risk of both material toxicity and fetal drug transfer. One drawback of spinal anaesthesia is its fixed duration after a single injection. A major adverse fetal effect of SA is maternal sympathetic blockade resulting in uteroplacental hypoperfusion causing hypotension and a decrease in the intervillous blood flow potentially leading to acidemia [

5,

6]. General anaesthesia (GA) provides a rapid and reliable onset, with steady control over the airway and ventilation, potentially reducing the risk of hypotension. GA may be more suitable in certain conditions (e.g., profound fetal bradycardia, ruptured uterus, severe haemorrhage, severe placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, and preterm footling breech) [

7]. Traditionally, there was a belief that exposure to general anaesthesia (GA) during a Caesarean section could lead to birth asphyxia [

8]. However, current understanding suggests that brief exposure to GA is generally safe for the foetus. Short-acting anaesthetics like propofol are preferred to minimize exposure time and reduce potential risks [

9].

Propofol offers a rapid reliable loss of consciousness [

10]. It is an intravenous sedative-hypnotic agent, containing amnestic properties for induction of GA. It also lowers cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, and cerebral metabolic rate whilst preserving static autoregulation [

11] and vascular responsiveness to carbon dioxide [

12]. Propofol’s neuroprotective effects are thought to stem from its antioxidant capabilities, its enhancement of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA)-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission, and its suppression of glutamate release in cerebral ventricles [

13]. On the other hand, GA has been demonstrated to be neurotoxic for certain animals’ developing brains in a dose and time manner and may be associated with both long-term learning and development disorders [

14,

15]. However, these effects of GA cannot be confirmed for the human species. The mechanisms underlying general anaesthesia-mediated effects, including neuroprotection and neurotoxicity, remain unclear despite various proposed hypotheses. The development of a reliable biomarker to detect acute anaesthesia neurotoxicity in the brain could significantly enhance research progress. However, uncertainties persist regarding its effectiveness in reflecting anaesthesia-related brain injury in humans.

The calcium-binding protein S100β serves as a widely employed biomarker for identifying brain damage resulting from various stressors, such as ischemia [

16] and trauma [

17,

18]. Notably sensitive, S100β, primarily found in astrocytes due to its affinity for calcium, plays a pivotal role in regulating diverse intra- and extracellular physiological processes. It functions both as a marker and a signal, activating detection and protective mechanisms upon central nervous system (CNS) damage [

19]. Studies indicate S100β’s established specificity as a marker for CNS tissue damage [

20]. Its presence in biological fluids, including cerebrospinal fluid, peripheral and cord blood, urine, saliva, and amniotic fluid, signifies active neural distress [

21]. Moreover, S100β serves as a reliable biomarker for fetal hypoxia and ischemic damage in pregnant patients. Investigations have demonstrated the correlation between elevated S100β plasma levels and brain damage in foetuses exposed to general anaesthetics, particularly reflecting apoptosis levels [

22]. This protein proves effective in detecting severe neurological damage in developing animal brains and can also identify the effects of prenatal drug exposure [

21,

22,

23].

The umbilical artery carries deoxygenated blood from the developing foetus’s circulation and demonstrates fetal changes whereas the umbilical vein holds oxygenated blood originating in the placenta and shows changes from the mother [

24]. Utilizing the brain damage biomarker S100β, we compared the ratio of S100β levels between maternal arterial blood and umbilical artery blood immediately post-delivery, and assayed fetal S100β levels. All patients underwent a C-section using SA or GA. Our hypothesis suggests that the brain damage biomarker S100β would exhibit no elevation in the cord arterial blood of foetuses who experienced brief exposure to general anaesthetics compared to those who underwent C-section using spinal anaesthesia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The study was a single-centre prospective, controlled study. In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the parturient women who undergo C-section in The Obstetrics and Gynaecology Hospital of The National Center of the Maternal and Child Health of Mongolia from July 2021 to December 2023 enrolled in this study. All procedures performed in the study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. The terms general anaesthesia (GA) and spinal anaesthesia (SA) were used to designate two distinct groups. Women giving birth by caesarean-section in hospital granted permission to take part in the study and were registered.

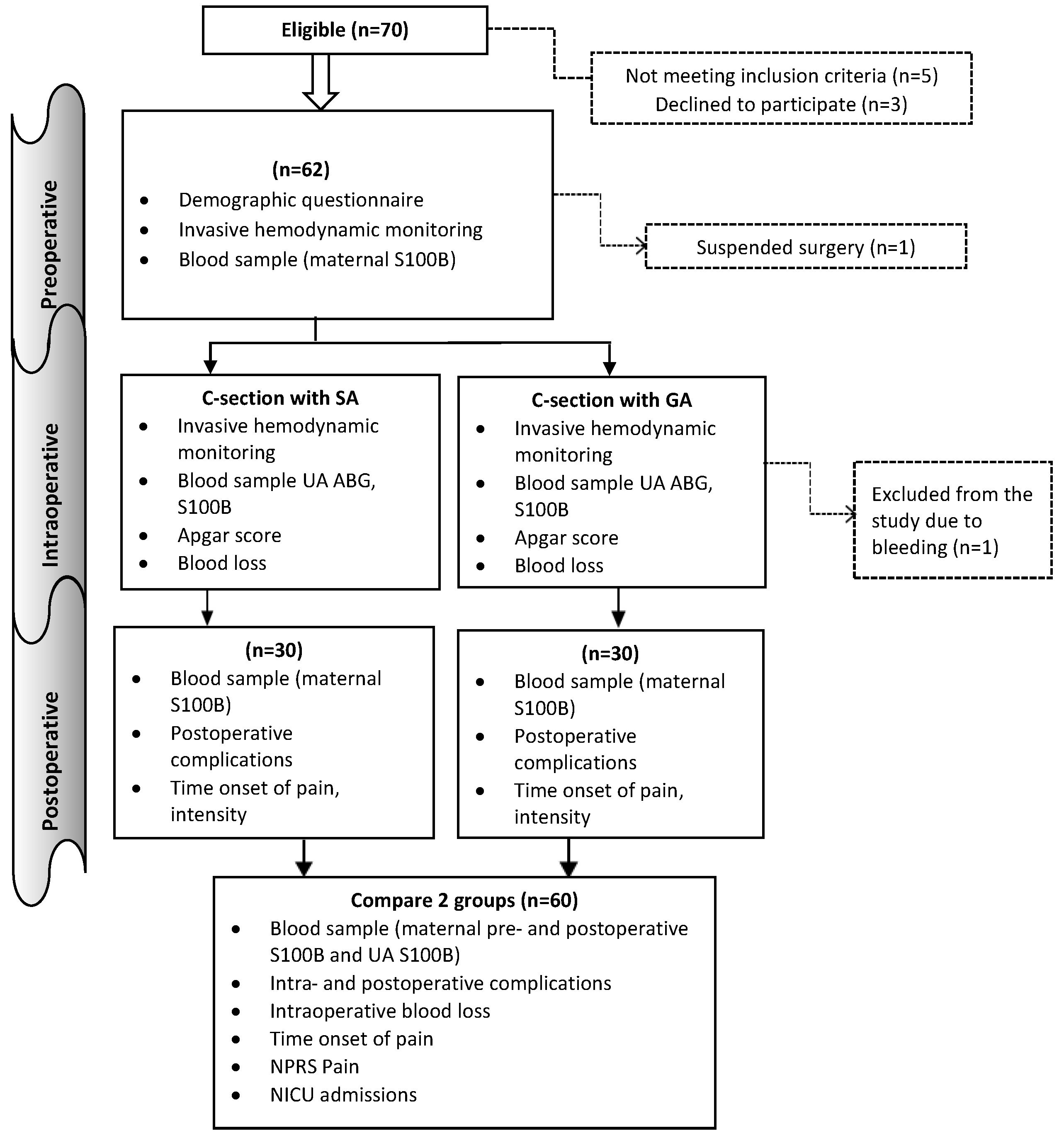

Figure 1 shows patient recruitment and flow. The sample size of the study was calculated using Open Epi software. The sample size was calculated based on the difference in means under the hypothesis of a difference between the two groups. A minimum of 29 subjects was required per study group. The study adhered to the following specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for the participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged between 18-40 (2) American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status I or II (3) term gestation at 37 weeks (4) patients whose haemoglobin >100 g/L (5) women with uncomplicated singleton pregnancies who were advised to undergo elective caesarean sections due to factors such as a previous caesarean delivery, a history of primary infertility, or other reasons. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) less than height 150 cm (2) body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 (3) parturient women who suffered from severe internal, surgical, or obstetric comorbidities (4) preeclampsia (5) known fetal neurologic deficit, intrauterine growth retardation (6) patients who received analgesic and sedative medicine before C-section (7) patients who suffering from a severe mental illness (8) emergency C-section for delivery (9) classification as ASA status ≥ III (10) patients who were unwilling to partake in the study (11) patients who were allergic to anaesthetics (12) patients who had contraindications to general/ or spinal anaesthesia.

2.2. Methods of Anaesthesia

In preparation, Ranitidine 150 mg orally (H2-blocker), and metoclopramide 10 mg intravenously. To avoid supine hypotension syndrome, women in both groups were maintained in a 15-degree left lateral tilt position until birth. An observer gathered all the intraoperative data. Hypoxia was defined as SpO2 <95%. A 20% decrease in systolic arterial pressure below the baseline value was defined as hypotension in this study and treated with intravenous ephedrine. Additionally, oxygen was administered at a rate of approximately five L/min through a transparent face mask during the operation. The anaesthetists performing the anaesthesia had similar levels of expertise and were unaware of the study protocol.

GA procedure: In the instances in the general anaesthesia group, pre-oxygenation was carried out using 100% oxygen for five minutes before the administration of general anaesthetic. Patients were induced with propofol 2 mg/kg (manufacturer: Guangdong Jiabo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; specification: 20 ml/ 200 mg) and succinylcholine 2 mg/kg intravenously. After anaesthesia was induced tracheal intubation was performed. After intubation the patients were administered 0.5 mg/kg of atracurium besylate (manufacturer: Flagship Biotech International, India; specification: 2.5 ml/25 mg), 2.0 μg/kg of fentanyl (manufacturer: IVCO, Mongolia, specification: 0.005%-2 ml) and infusions of propofol at 2.5 mg/kg per and fentanyl at 0.05 mg/kg per minute. Surgery began after verification that the endotracheal tube was appropriately placed and positioned through capnography. After delivery, the patients received intravenous injection of five units of oxytocin then continuous pump infusion 15 units (manufacturer: HBM Pharma, Slovakia, specifications: 1 ml/5 mg). Anaesthesia maintained with continuous inhalation of 1 MAC of isoflurane and propofol intravenously at a dosage of 1.5 mg/kg.

SA procedure: With the patient lying in a left lateral position, spinal anaesthesia was performed at the L2–L3 or L3–L4 interspace with 10 mg of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine (manufacturer: Troikaa, Pharmaceuticals Ltd, India specification: 4 ml/20 mg) plus 10 micrograms of fentanyl. The level of the sensory block was modified to be approximately T5–T6.

2.3. Follow-Up

Preoperative: Eligible patients were contacted and provided with written informed consent prior to surgery. Preoperative assessments were carried out by main investigators, the researchers gathered demographics data and basal health questionnaires.

Intraoperative: Radial arterial cannulation was performed for all the patients using 20G Surflo® (Terumo China holding Co., Ltd.) under local anaesthesia (2% lidocaine), and arterial blood pressure was monitored. Invasive blood pressure readings including systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressures were obtained. Heart rate and SpO2 were measured by the fingertip photoelectric sensor (manufactured: Guangzhou Sichuang Hongyi Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.). Time from anaesthesia induction to delivery, total operative time, intraoperative blood loss, urine output, and complications during surgery were recorded in both groups. All vital signs were recorded.

Postoperative: For the two hours of the postoperative stage, patients were monitored in the recovery room. Complications after C-section within two hours were recorded in both groups including postoperative nausea, vomiting, headache, fever, and pain. The patients were assessed using the Numeric pain rating scale (NPS), which showed the severity of the postoperative level of pain from a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 = no pain and 10 being the worst pain ever. The onset time was also recorded.

Neonatal assessment: Following the delivery of the baby, pediatricians assessed the neonatal condition, assigned Apgar scores at one and five minutes, and determined the need for admission to the Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). An Apgar score of 7 to 10 was considered normal; 4 to 6, mild neonatal asphyxia; and 3 and below, severe neonatal asphyxia. The Apgar score was assessed based on 5 criteria: activity, pulse rate, grimace (reflex irritability), skin color, and respiratory effort. Following the delivery of the baby, the cord was cut between the two clamps placed approximately 10 to 12 cm apart and away from the placenta and newborn. One to three ml of blood was collected from the umbilical artery from between the clamps immediately following placental delivery. This protocol was designed to prevent contamination of S100β levels in the cord arterial blood by placental S100β, ensuring that the measured concentrations accurately reflect those originating from the newborn.

2.4. Laboratories Outcome Measurements

Measurement of serum s100 β: The maternal serum S100β protein levels of the 30 patients from each group were analyzed before and at the end of the operation, with 5 ml of blood was withdrawn from the mother via the arterial line. The blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 2500 RPM for 10 minutes and the supernatant was gathered and stored at minus 80-degree temperature until the measurement of S100β levels. The concentration of S100β protein in the blood serum was determined by the enzyme-linked antibody reaction (ELISA) using the Human S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B) ELISA kit (Catalog Number SL2183Hu) album of Sunlong Biotech CO., Ltd (China). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, each sample was incubated with the tracer from the kit for 2 hours, following the instructions precisely to maintain intra-batch variation below 10% and inter-batch variation below 15%.

Arterial blood gas analysis: The blood gas analysis was performed from umbilical cord blood immediately drawn after the delivery. A sample of the blood was immediately inserted to a blood gas/electrolyte analyzing system. (COBAS B-221, ROSHE) for рН, рСО2, рО2, Hb, Hct, O2Hb, COHb, Ca2+, K+, Na+, CI-, SO2, BB, BE, HCO3, Osm measure and compared between the 2 groups, and the remaining blood sample was then used for the S100β study assay.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of the study involved collecting blood samples for the analysis of brain injury biomarker S100β. These samples were obtained from the arterial line of maternal blood, both preoperative and postoperative, as well as from the umbilical artery of C-section deliveries performed under either spinal or general anaesthesia. The secondary outcomes were invasive hemodynamic monitoring, surgery and anaesthesia outcomes, umbilical cord blood gas values, Apgar scores, neonatal asphyxia rate, and maternal postoperative numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) compared in two groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentages. Continuous variables were assessed for distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and dependent variables were normally distributed. Differences between the two groups were calculated using a parametric test. Differences between the means of two groups were evaluated by the T test. Proportional differences between groups were calculated using the Chi-square test. In case of abnormal distribution, differences between three groups were determined by Friedman’s test, and Wilson Signed Rank test was used for differences between two groups

3. Results

Sixty patients were recruited for the study. This study included a total of 60 pregnant women undergoing caesarean section, equally divided into two anaesthesia groups: Spinal Anaesthesia (SA) and General Anaesthesia (GA) (n=30 per group). To ensure comparability before assessing anesthetic effects on fetal outcomes, maternal demographic and obstetric characteristics were analyzed between the two groups. They were comparable among the study groups, with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), as shown in

Table 1.

3.1. S100β Marker and Methods of Anaesthesia

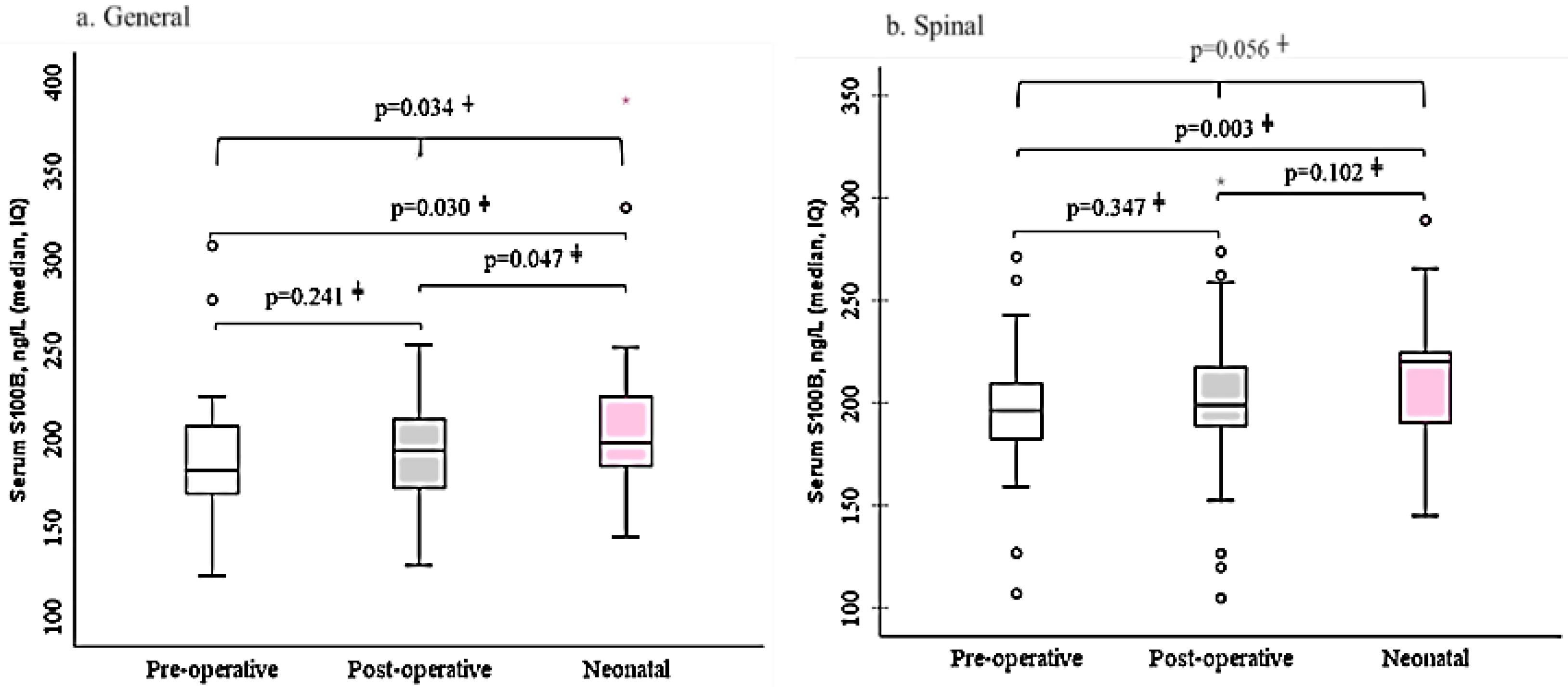

The mean serum S100β levels was 194.1 ± 45.8 ng/L in all women pre-operatively with no significant difference observed between the two groups (p=0.231). Furthermore, there were no significant difference between SA and GA group S100β protein levels post-surgery (p=0.375) and in newborn blood serum (p=0.143) (

Table 2).

The changes in S100β protein levels before and after surgery were different for each group. The maternal blood S100β post-surgery and neonatal umbilical cord blood protein levels were different in the GA group (p=0.047), there were lacked a difference in the SA group. In the SA group, preoperative S100β concentration in maternal blood was 195.1±36.2 ng/L, then increased to 200.9±42.9ng/L at the end of operation. Also, in the GA group, preoperative S100β concentration in maternal blood was 193.0±54.3 ng/L, then increased to 197.0±42.7 at the end of operation (

Figure 2).

3.2. Perioperative Characteristics by Anaesthesia Groups

The perioperative outcomes, intraoperative time, drug dosage and postoperative complications between the 2 groups, are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. There were zero noteworthy differences in time from anaesthesia to incision, the operation duration, infused crystalloid volume, blood loss, and urine output (

Table 3).

However the frequency of headache and nausea were more common in the SA group (p<0.0001, p<0.0001) while hypertension and tachycardia were more frequent in the GA group (p=0.079, p<0.0001) during surgery. Postoperative complications such as nausea, headache and weakness were significantly difference in the SA and GA groups (p=0.044). We detected that the time of onset of pain was significantly shorter in GA group was 13 (43.3%) patients felt pain after surgery within ≤ 60 minutes. The NPRScore and length of stay in hospital between the two groups were also alike. (p=0.105, p=0.232) (

Table 4)

3.3. Neonatal Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes Following Spinal Versus General Anaesthesia

No significant differences were found in Apgar scores and neonatal asphyxia rates between the two groups (p=0.476) and blood gas outcomes of the umbilical artery (UA) in

Table 5. It shows pH and Ca

2+ levels of UA were lower in the GA group (p=0.009, p=0.0001).

4. Discussion

The stress response to surgery triggers various physiological and biochemical changes, including sympathetic nervous system activation, the release of stress hormones such as cortisol and catecholamines, and modulation of immune function [

25]. Exposure to anaesthetic agents has been shown to induce programmed cell death (apoptosis) in glial and neuronal cells of the central nervous system, potentially leading to neurotoxicity and brain injury. Numerous animal and in vitro studies have reported that anaesthetic agents can exert harmful effects on the developing brain [

26], particularly barbiturates, ketamine, propofol, and inhaled anaesthetics [

27].

This study examined the brain injury biomarker S100β during cesarean section under general anaesthesia (GA; propofol, fentanyl, isoflurane) and spinal anaesthesia (SA; bupivacaine, fentanyl). Perioperative measurement of S100β levels, which reflects glial cell activity and possible neuroinjury, was performed before and after surgery [

28]. Our primary finding was a slight, non-significant increase in maternal arterial S100β concentrations following C-section in both GA and SA groups. This finding aligns with those of Zhendong Xu et al., who reported no significant change in maternal venous S100β levels following epidural or general anaesthesia during C-section [

29].

Additionally, our results indicated that cesarean delivery itself does not appear to significantly influence maternal S100β concentrations. However, some studies have reported higher S100β levels in vaginal deliveries compared to elective C-sections, suggesting delivery-mode dependency [

30,

31]. One previous study observed a significant decrease in the umbilical artery/umbilical vein (UA/UV) S100β ratio after GA compared to epidural anaesthesia, while maternal venous S100β levels remained largely unchanged [

32]. In our dataset, UA S100β concentrations were consistently higher than maternal levels in both GA and SA groups, with a slightly lower level observed in the GA group.

We also established a reference range for serum S100β in third-trimester pregnant Mongolian women, identifying a baseline of 194.1 ± 45.8 ng/L. Notably, S100β levels measured beyond 37 weeks of gestation exceeded this normal range [

33]. We propose two primary interpretations for our findings. Neither general nor spinal anaesthesia caused detectable neuronal injury during cesarean delivery. This may be attributed to the short duration of surgery and, consequently, limited exposure to anaesthetic agents. In fact, brief GA exposure might confer some neuroprotection under stress conditions [

34], possibly explaining the slightly lower post-operative S100β levels in the GA group. The absence of maternal (e.g., CNS disorders), obstetric (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, placental insufficiency), or fetal (e.g., acute/chronic hypoxia) complications—conditions known to elevate S100β—may have influenced our results. Moreover, previous studies support the concept that fetal-origin S100β can pass into maternal circulation via a physiological gradient [

35], consistent with our finding that UA S100β levels exceeded maternal concentrations. Although we did not find a significant association between S100β concentrations and perioperative variables, we observed moderate correlations with some umbilical artery blood gas parameters. In conclusion, our findings suggest that cesarean delivery under either anaesthetic technique does not significantly alter maternal S100β levels, and thus may not be associated with acute brain injury. However, the anaesthetic agents used could influence biomarker profiles.

Our study’s strengths include the use of a newly biomarker that allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of two anesthesia methods on both maternal and fetal brain damage during C section. Firstly, this is the first known investigation to assess S100β levels in the maternal and umbilical circulation among pregnant Mongolian women undergoing cesarean section, thus contributing unique regional data to the global literature. Secondly, the study provides a direct comparison between general and spinal anaesthesia, offering valuable insights into their respective impacts on neonatal biochemical outcomes and maternal neurobiological markers. Thirdly, by including both maternal and fetal (umbilical arterial) blood samples, we were able to explore the potential fetal origin of S100β more comprehensively. Additionally, the use of standardized anaesthetic protocols and perioperative care ensured internal consistency, while the integration of neonatal Apgar scores and arterial blood gas analysis allowed for a broader evaluation of neonatal well-being. These elements collectively strengthen the scientific value and clinical relevance of our findings. But this study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size limits the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. Second, the study population consisted exclusively of pregnant women from a single tertiary hospital in Mongolia’s capital city, further restricting external applicability. Additionally, the lack of long-term follow-up prevents conclusions regarding the potential delayed neurological effects of anaesthetic exposure.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, S100β concentrations slightly increased after C-section in both the SA and GA group. General anaesthesia has a faint impact on the umbilical cord blood’s S100β levels during C-section. Spinal and general anesthesia are considered safe for the maternal and fetal brain during cesarean sections when administered appropriately, with no evidence suggesting harmful effects. Further research needed to study associations between anaesthetic drugs, perioperative release of brain injury biomarker, and perioperative clinical outcomes are warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B, E.J, M.J, and G.L; methodology, M.B, E.J, M.J, and G.L; software, M.B, N.E, T.S; validation, M.B, E.J, M.J, and G.L; formal analysis, M.B, M.J, and N.E; investigation, M.B, M.J, and Т.S; resources, M.B, M.J, and G.L; data curation, M.B, M.J, and N.E; writing—original draft preparation, M.B, M.J, and N.E; writing—review and editing, M.B, E.J, M.J, and G.L; visualization, M.B, N.E; supervision, E.J, M.J, and G.L; project administration, М.B; funding acquisition, M.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The National Center of the Maternal and Child Health of Mongolia (Date/number: June 02 2021/291) and the Ethics Committee of Mongolian Na-tional University of Medical Sciences (Date/number: June 04 2021/2021/3-07). The C-section scheduled patients gave their written consent for spinal or general anaesthesia for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the doctors and researchers at the National Center for Maternal and Child Health and the University of Medical Sciences for their assistance in conducting the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| ABG |

Arterial blood gas |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| GA |

General anesthesia |

| SA |

Spinal anesthesia |

| UA |

Umbilical artery |

References

- WHO. Caesarean section rates continue to rise, amid growing inequalities in access. Departmental update 2021; 06: 1-2.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health Indicators 2012; 08: 10-12.

- Center for health Development of Mongolia. Health indicators 2016; 16: 12-14.

- Agegnehu, A.F.; Gebregzi, A.H.; Endalew, N.S. Review of evidences for management of rapid sequence spinal anesthesia for category one cesarean section, in resource limiting setting. Int. J. Surg. Open 2020, 26, 101–105. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.D.; Brühwiler, H.; Schüpfer, G.K.; Lüscher, K.P. Higher rate of fetal acidemia after regional anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 90, 131–134. [CrossRef]

- Yeǧn A, Ertuǧ Z, Yilmaz M, Erman M. The effects of epidural anesthesia and general anesthesia on newborns at cesarean section. Turkish J Med Sci 2003; 33: 311-314.

- Siddik-Sayyid S, Zbeidy R. Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia 2008; 19: 23-24.

- Trincado Dopereiro JM, Martin Sanchez V. Fetal asphyxia caused by general anesthesia in cesarean section; new anesthetic method of preventing it. Rev Esp Obstet Ginecol 1955;14: 86-95.

- Mhyre JM, Sultan P. General Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery: Occasionally Essential but Best Avoided. Anesthesiology 2019; 130:864-866.

- Godambe, S.A.; Elliot, V.; Matheny, D.; Pershad, J. Comparison of Propofol/Fentanyl Versus Ketamine/Midazolam for Brief Orthopedic Procedural Sedation in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Strebel, S.; Lam, A.; Matta, B.; Mayberg, T.S.; Aaslid, R.; Newell, D.W. Dynamic and Static Cerebral Autoregulation during Isoflurane, Desflurane, and Propofol Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1995, 83, 66–76.. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Gelb, A.W.; Enns, J.; Murkin, J.M.; Farrar, J.K.; Manninen, P.H. The Responsiveness of Cerebral Blood Flow to Changes in Arterial Carbon Dioxide Is Maintained during Propofol–Nitrous Oxide Anesthesia in Humans. Anesthesiology 1992, 77, 453–456. [CrossRef]

- Yano, T.; Nakayama, R.; Ushijima, K. Intracerebroventricular propofol is neuroprotective against transient global ischemia in rats: extracellular glutamate level is not a major determinant. Brain Res. 2000, 883, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zuo, Z. Isoflurane induces hippocampal cell injury and cognitive impairments in adult rats. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 1354–1359. [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, G.; Sall, J.W.; May, L.D.; Bell, J.S.; Magnusson, K.R.; Rau, V.; Visrodia, K.H.; Alvi, R.S.; Ku, B.; Lee, M.T.; et al. Isoflurane Differentially Affects Neurogenesis and Long-term Neurocognitive Function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old Rats. Anesthesiology 2009, 110, 834–848. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.-W. Umbilical artery blood S100β protein: a tool for the early identification of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008, 168, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Tavarez, M.M.; Atabaki, S.M.; Teach, S.J. Acute evaluation of pediatric patients with minor traumatic brain injury. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012, 24, 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, S.M.; McKinney, J.; Smith, L.; Brisman, J. Reliability of S100B in predicting severity of central nervous system injury. Neurocritical Care 2007, 6, 121–138. [CrossRef]

- Arrais, A.C.; Melo, L.H.M.F.; Norrara, B.; Almeida, M.A.B.; Freire, K.F.; Melo, A.M.M.F.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Lima, F.O.V.; Engelberth, R.C.G.J.; Cavalcante, J.d.S.; et al. S100B protein: general characteristics and pathophysiological implications in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020, 132, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Care S W. Anesthesia-Induced Neurodegeneration in Fetal Rat Brains. Pediatr Res 2009; 66: 435-440.

- Wang, S.; Peretich, K.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, G.; Meng, Q.; Wei, H. Anesthesia-Induced Neurodegeneration in Fetal Rat Brains. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 435–440. [CrossRef]

- Gazzolo, D.; Bruschettini, M.; Di Iorio, R.; Marinoni, E.; Lituania, M.; Marras, M.; Sarli, R.; Bruschettini, P.L.; Michetti, F. Maternal Nitric Oxide Supplementation Decreases Cord Blood S100B in Intrauterine Growth-retarded Fetuses. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 647–650. [CrossRef]

- Serpero, L.D.; Pluchinotta, F.; Gazzolo, D. The clinical and diagnostic utility of S100B in preterm newborns. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 444, 193–198. [CrossRef]

- Weiler H. Vascular biology of the placenta. In: Endothelial Cells in Health and Disease. CRC Press 2005; 245-264.

- Desborough JP, Hall GM. The stress response to surgery. Curr Anaesth Crit Care 1990; 1: 133-137.

- Loepke, A.W.; Soriano, S.G. An Assessment of the Effects of General Anesthetics on Developing Brain Structure and Neurocognitive Function. Anesthesia Analg. 2008, 106, 1681–1707. [CrossRef]

- Campagna, J.A.; Miller, K.W.; Forman, S.A. Mechanisms of Actions of Inhaled Anesthetics. New Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2110–2124. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Duan, G.; Wu, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Li, H. Comparison of the cerebroprotective effect of inhalation anaesthesia and total intravenous anaesthesia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014629. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.-W. Umbilical artery blood S100β protein: a tool for the early identification of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008, 168, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Abella, L.; D’adamo, E.; Strozzi, M.; Sanchez-De-Toledo, J.; Perez-Cruz, M.; Gómez, O.; Abella, E.; Cassinari, M.; Guaschino, R.; Mazzucco, L.; et al. S100B Maternal Blood Levels in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Are Birthweight, Gender and Delivery Mode Dependent. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 1028. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Iwasaki, A.; Mori, T.; Kimura, C.; Matsushita, H.; Shinohara, K.; Wakatsuki, A. Differences in levels of oxidative stress in mothers and neonate: the impact of mode of delivery. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 1649–1652. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, C.; Shen, F.; Yu, Y.; Cheek, T.; Onuoha, O.; Liang, G.; Month, R.; et al. S100β in newborns after C-section with general vs. epidural anesthesia: a prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2017, 62, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Serpero, L.D.; Bianchi, V.; Pluchinotta, F.; Conforti, E.; Baryshnikova, E.; Guaschino, R.; Cassinari, M.; Trifoglio, O.; Calevo, M.G.; Gazzolo, D. S100B maternal blood levels are gestational age- and gender-dependent in healthy pregnancies. cclm 2017, 55, 1770–1776. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Drobish, J.K.; Liang, G.; Wu, Z.; Liu, C.; Joseph, D.J.; Abdou, H.; Eckenhoff, M.F.; Wei, H. Anesthetic Preconditioning Inhibits Isoflurane-Mediated Apoptosis in the Developing Rat Brain. Anesthesia Analg. 2014, 119, 939–946. [CrossRef]

- Sannia, A.; Zimmermann, L.J.; Gavilanes, A.W.; Vles, H.J.; Serpero, L.D.; Frulio, R.; Michetti, F.; Gazzolo, D. S100B Protein maternal and fetal bloodstreams gradient in healthy and small for gestational age pregnancies. Clin. Chim. Acta 2011, 412, 1337–1340. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).