1. Introduction

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder caused by mutations in the

FBN1 gene, which encodes fibrillin-1, a large glycoprotein critical for extracellular matrix integrity and elastic fiber formation. The defective fibrillin-1 protein leads to dysregulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling, contributing to structural abnormalities in multiple organ systems [

1,

2,

3]. Clinically, MFS is characterized by a wide array of manifestations, including skeletal deformities (e.g., scoliosis, pectus excavatum), ocular complications (e.g., ectopia lentis), and cardiovascular anomalies, particularly aortic root dilation and subsequent aortic dissection. Among these, cardiovascular complications represent the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in individuals with MFS. The current standard of care focuses on early diagnosis, pharmacological management, surgical intervention, and lifestyle modifications aimed at reducing hemodynamic stress on the aorta. Pharmacologic agents such as beta-blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have shown efficacy in delaying the progression of aortic dilation by reducing aortic wall stress and modulating downstream TGF-β signaling. Surgical repair of the aortic root is a life-saving intervention that has significantly improved survival rates. Despite these advancements, the chronic and progressive nature of MFS, compounded by recurrent medical interventions and multisystem involvement, continues to profoundly affect patients’ quality of life [

4,

5,

6].

Recently, attention has turned to lifestyle interventions, particularly physical activity, as a complementary approach to improve outcomes in MFS. Traditionally, individuals with MFS have been advised to avoid high-intensity physical activity due to concerns over exacerbating aortic stress and the risk of aortic rupture. However, emerging evidence suggests that mild to moderate aerobic exercise may offer protective cardiovascular benefits without compromising aortic integrity [

7,

8]. Preclinical studies in MFS mouse models have demonstrated that low to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise improves aortic wall structure by preserving elastin integrity and reducing aortic dilation. Mechanistically, these benefits appear to be mediated by exercise-induced improvements in endothelial function, nitric oxide (NO) production, and reduced transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity [

9,

10].

Despite these promising findings, several critical gaps remain. For example, our knowledge of the impact of MFS’s pathology on various organ systems, particularly the vasculature beyond the aorta, remains limited [

11]. Existing studies have largely focused on the aortic root and its associated complications, leaving gaps in understanding the structure, function, and interplay of other central and peripheral arteries, such as the cerebral, carotid, coronary, pulmonary, and renal arteries, in the context of MFS. Additionally, the implications of aging and common vascular comorbidities, such as atherosclerosis and hypertension, on MFS-associated arterial dysfunction are underexplored [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The interplay between physical activity and vascular health in MFS also remains poorly understood. Existing evidence highlights the potential benefits of mild aerobic exercise in enhancing aortic structure and function [

24,

25,

26]. In this study, we aim to further explore the effects of exercise on other central and peripheral arteries in MFS mice using in vivo ultrasound imaging. The goal is to develop evidence-based recommendations for integrating safe and effective physical activity into the management of MFS, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals & Exercise Protocol

In this study, we utilized a transgenic mouse model carrying a missense mutation in the Fbn1 allele (C1041G), which introduces a cysteine-to-glycine substitution (Cys1041→Gly) within an epidermal growth factor–like domain of fibrillin-1 (Fbn1C1041G/+). The control group consisted of wild-type C57BL/6 littermates. At 6 weeks of age, male and female mice were randomly assigned to the following groups: Control (Ctrl), MFS, and MFS + treadmill exercise. Mice were group-housed (four per cage) under a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle, with unrestricted access to food and water. The exercise group were subjected to treadmill running at 55% VO2max. Acclimation to the exercise protocol was conducted over three consecutive days, starting at 5 m/min, and gradually increasing to 8 m/min for 20 minutes per session. During the training phase, mice exercised 5 days/week, and the protocol continued until the mice reached 6 months of age. All procedures and protocols involving mice were approved by the Midwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals received humane care in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institute of Health.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size estimation was conducted based on previous preliminary data for the diameter of the sinus of Valsalva in control and MFS mice. Assuming an expected intervention (exercise) effect of a 15–20% reduction in aortic root diameter—an effect considered clinically meaningful given that in humans, an increase from 4 to 5 cm typically warrants surgical root replacement—we estimated the required sample size to detect this difference. Using a power of 0.8 and an alpha level of 0.05, the estimated sample size for comparing two means was determined to be eight animals per group.

2.3. Echocardiography

At 7 months of age, male and female mice from both the MFS and Ctrl groups underwent in vivo high-resolution ultrasound imaging. Echocardiography was performed using the Vevo 2100 high-resolution ultrasound system, equipped with an MS550 transducer (Visualsonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Mice were imaged under anesthesia. Initially, they were placed in an induction chamber with 3% isoflurane and 100% oxygen for 2-3 minutes, until the righting reflex was lost. Each mouse was then positioned supine on a heated platform, with their nose placed in a nosecone to maintain anesthesia with 2% isoflurane. Electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes were attached to the limbs to monitor heart rate, and body temperature was maintained between 36-38°C using a rectal probe.

The aortic diameter at the sinus of Valsalva was measured using the B-mode aortic arch view. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) was determined from the B-mode and Doppler-mode aortic arch view, calculated using the formula: PWV (mm/s) = aortic arch distance (d2-d1) / transit time (T1-T2). The aortic arch distance (d2-d1) was measured between the two sample volume positions along the central axis of aortic arch in the B-mode image. Transit time (T1-T2) was derived from the Doppler waveform data.

Peak systolic velocity (PSV) is a parameter measured using Doppler ultrasound. On a Doppler waveform, PSV corresponds to the tallest “peaks” in the spectrum window, representing the maximum blood flow velocity during systole. The blood flow velocity can vary depending on vessel properties and pathological changes. For this study, the peak blood flow velocity of the coronary and pulmonary arteries was measured using the pulse wave (PW) Doppler-mode in the long axis view. The peak blood flow velocity of the left common carotid, posterior cerebral, and renal arteries was also measured using PW Doppler-mode. The left common carotid artery wall thickness and distensibility were assessed using M-Mode ultrasound imaging.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Ultrasound imaging data were analyzed using Vevo LAB software (FUJIFILM, Toronto, ON, Canada), with measurements averaged over five cardiac cycles to minimize potential bias. Echocardiographic image acquisition was performed by a single investigator, while data analysis was conducted by two independent observers blinded to animal genotypes. Normality of the data for sinus of Valsalva diameter and aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and D’Agostino–Pearson normality tests in GraphPad Prism. All datasets passed the normality tests, allowing for parametric analysis. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Data are reported as Mean ± SEM, with significance defied as P < 0.05.

The relationship between different measurements was determined using simple linear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism. The correlation coefficient (R-squared) was used to evaluate the quality of the model’s fit to the data and to quantify the proportion of variability in the dependent variable (Y) explained by the independent variable (X). R-squared values range from 0 to 1 and typically expressed as percentages, indicating the degree to which the independent variable accounts for the changes in the dependent variable (e.g., 0%-100%).

4. Discussion

This study investigated cardiovascular structural and functional changes in a mouse model of MFS and evaluated the therapeutic potential of mild exercise training. Our findings provide valuable insights into MFS pathology and demonstrate the beneficial effects of exercise on vascular health, emphasizing the importance of early intervention strategies to manage cardiovascular complications in MFS.

Our data revealed a significant increase in aortic root diameter and pulse wave velocity (PWV) in both male and female MFS mice, consistent with previous studies identifying aortic root dilation and increased arterial wall stiffness as key features of MFS [

10,

12,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Aortic root dilation, particularly at the sinus of Valsalva, is a well-established hallmark of MFS and is associated with increased risk of aortic aneurysms and dissection. Similarly, the elevated PWV observed in MFS mice indicates impaired vascular compliance, a key contributor to the elevated cardiovascular morbidity in MFS patients. These findings were corroborated by high-resolution ultrasound imaging, which revealed significant structural and functional alterations in the carotid arteries. In the left common carotid artery (LCCA), both male and female MFS mice exhibited increased PWV and wall thickness, as well as reduced distensibility. These changes reflect vascular remodeling and a reduction in elastic decreased elastic properties, consistent with early-stage atherosclerosis or generalized arterial stiffness. Such alterations may impair blood flow and contribute to the increase in cardiovascular risk in MFS.

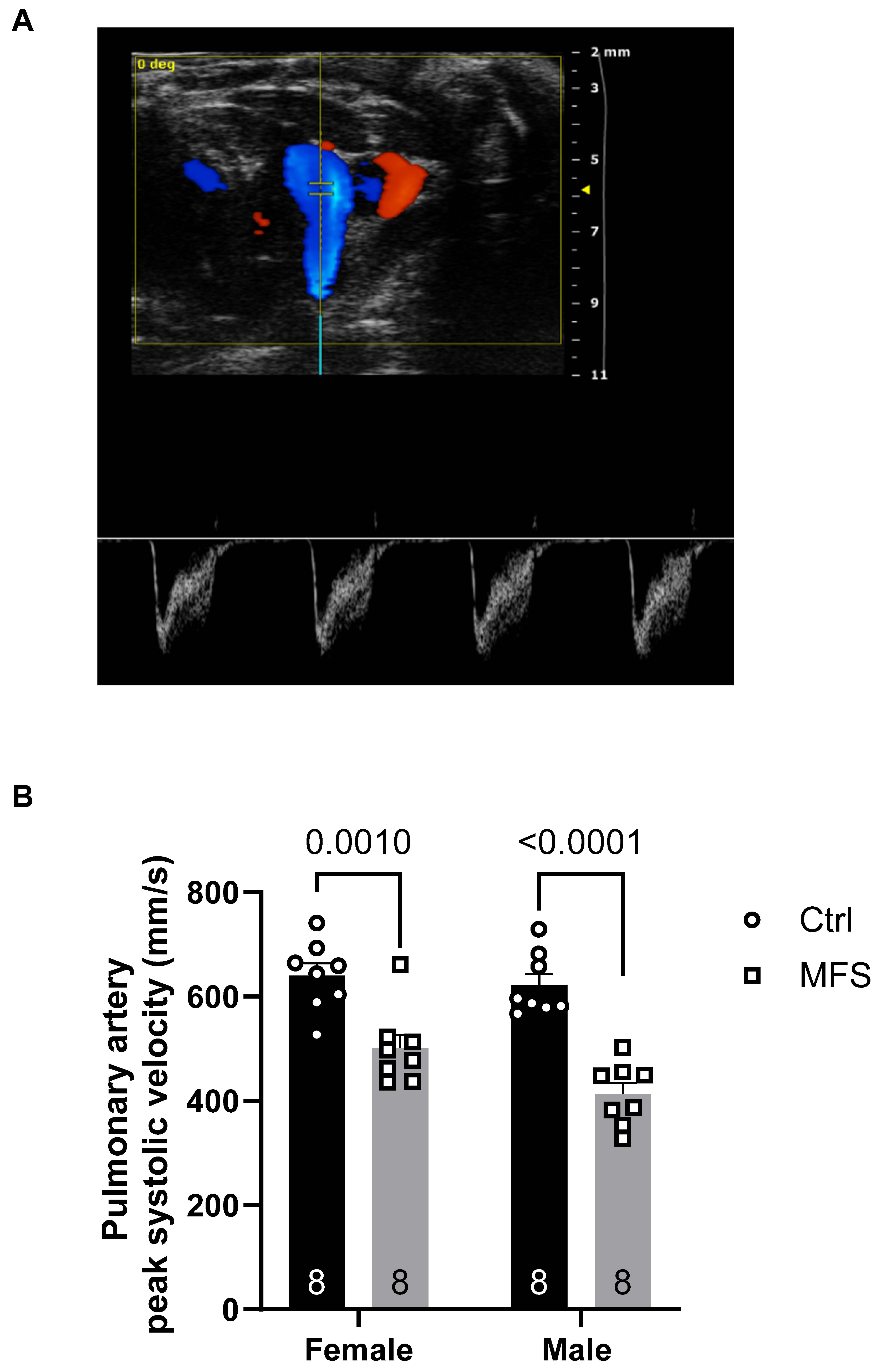

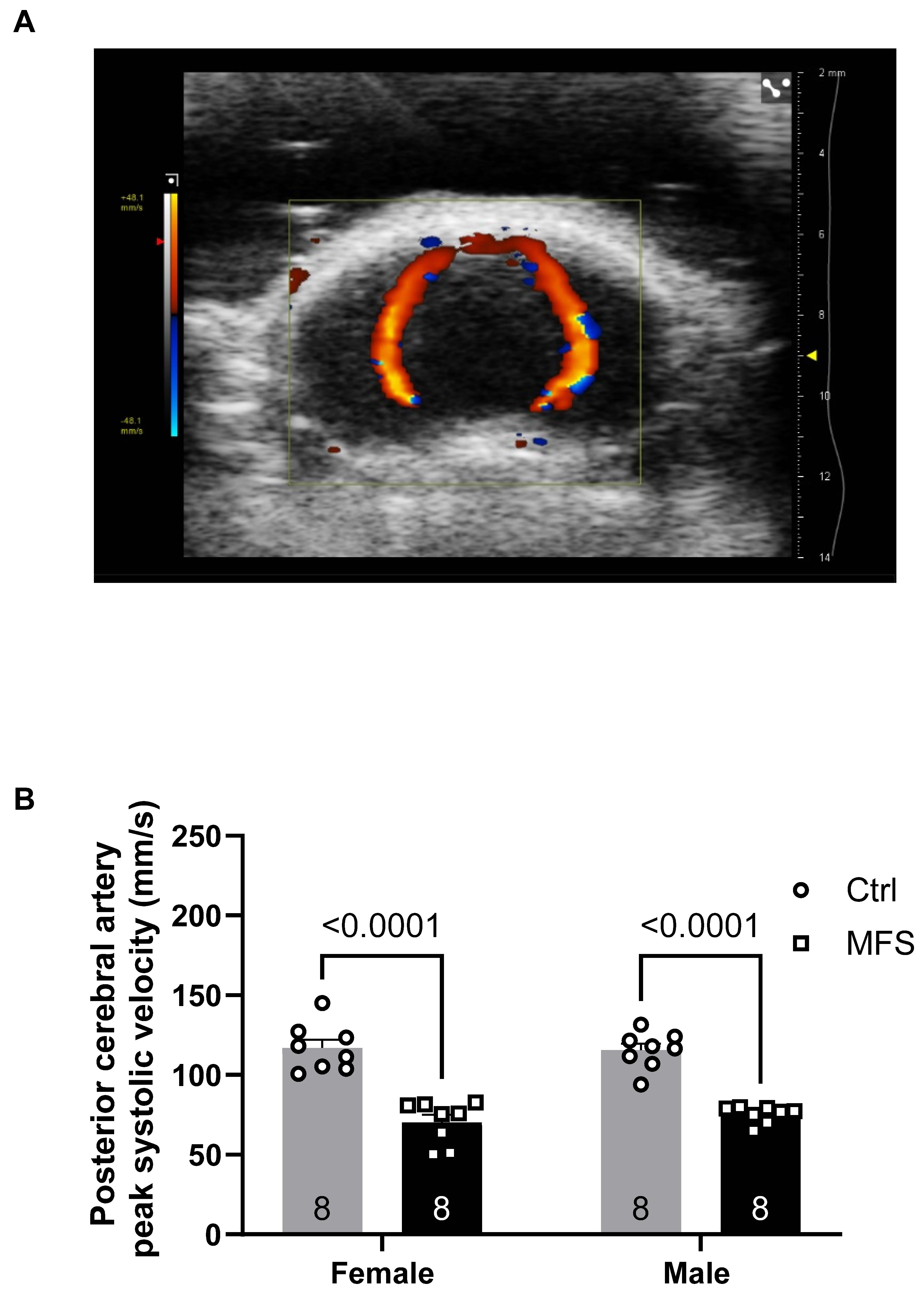

The reduced peak systolic velocity (PSV) observed in several arteries, including the posterior cerebral and pulmonary arteries, underscores the functional consequences of the structural alterations seen in MFS mice aorta. Notably, the decrease in PSV in the posterior cerebral artery may have significant implications for cerebral perfusion, which is essential for maintaining normal brain function. The reduction in carotid and PCA blood flow velocities may have important cerebrovascular consequences, particularly with the consideration of our previous reports showing increased blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, heightened microglial activation, and impaired cognitive function in MFS. In our previous report, we demonstrated that 6-month-old MFS mice exhibited a significantly increased number of microglia in the hippocampus compared to age-matched control mice. This microglial profile closely resembled that observed in 12-month-old healthy control mice. Additionally, 6 -month-old MFS mice showed elevated levels of apoptosis relative to sex- and age-matched controls. Collectively, these findings suggested that MFS mice displayed features consistent with a premature brain aging phenotype [

12,

32].

Increased aortic PWV reflects central arterial stiffness, which can lead to enhanced transmission of pulsatile energy into cerebral microcirculation due to reduced cushioning from the elastic central arteries. When this occurs in the setting of decreased carotid artery distensibility and flow, the brain is subjected to greater hemodynamic stress, which has been shown to damage the microvasculature, disrupt the BBB, and promote microglial activation—processes linked to neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline [

33].

Furthermore, the increased carotid wall thickness and reduced distensibility suggest early vascular remodeling, possibly driven by inflammation, altered smooth muscle cell phenotype, or fibrotic changes in response to abnormal TGF-β signaling—commonly dysregulated in MFS [

34]. These vascular changes may impede blood delivery to the brain and reduce cerebral perfusion reserve, predisposing MFS mice to hypoperfusion-induced BBB breakdown, as we previously reported [

12]. These results underscore the importance of evaluating cerebral hemodynamics and vascular-brain interactions in the context of MFS, particularly in light of emerging evidence that cognitive symptoms and neurovascular dysfunction may be under-recognized clinical features in this population [

35].

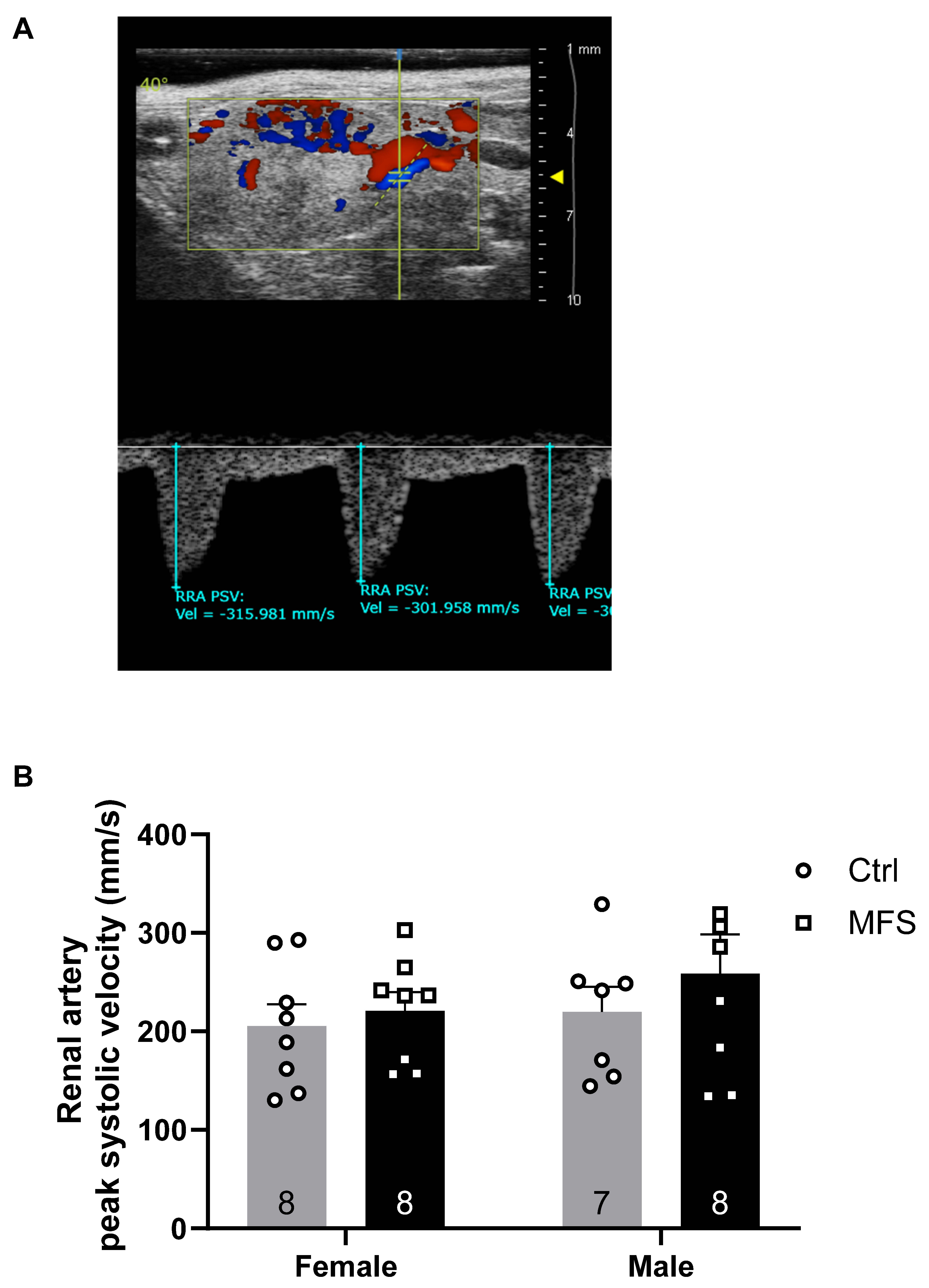

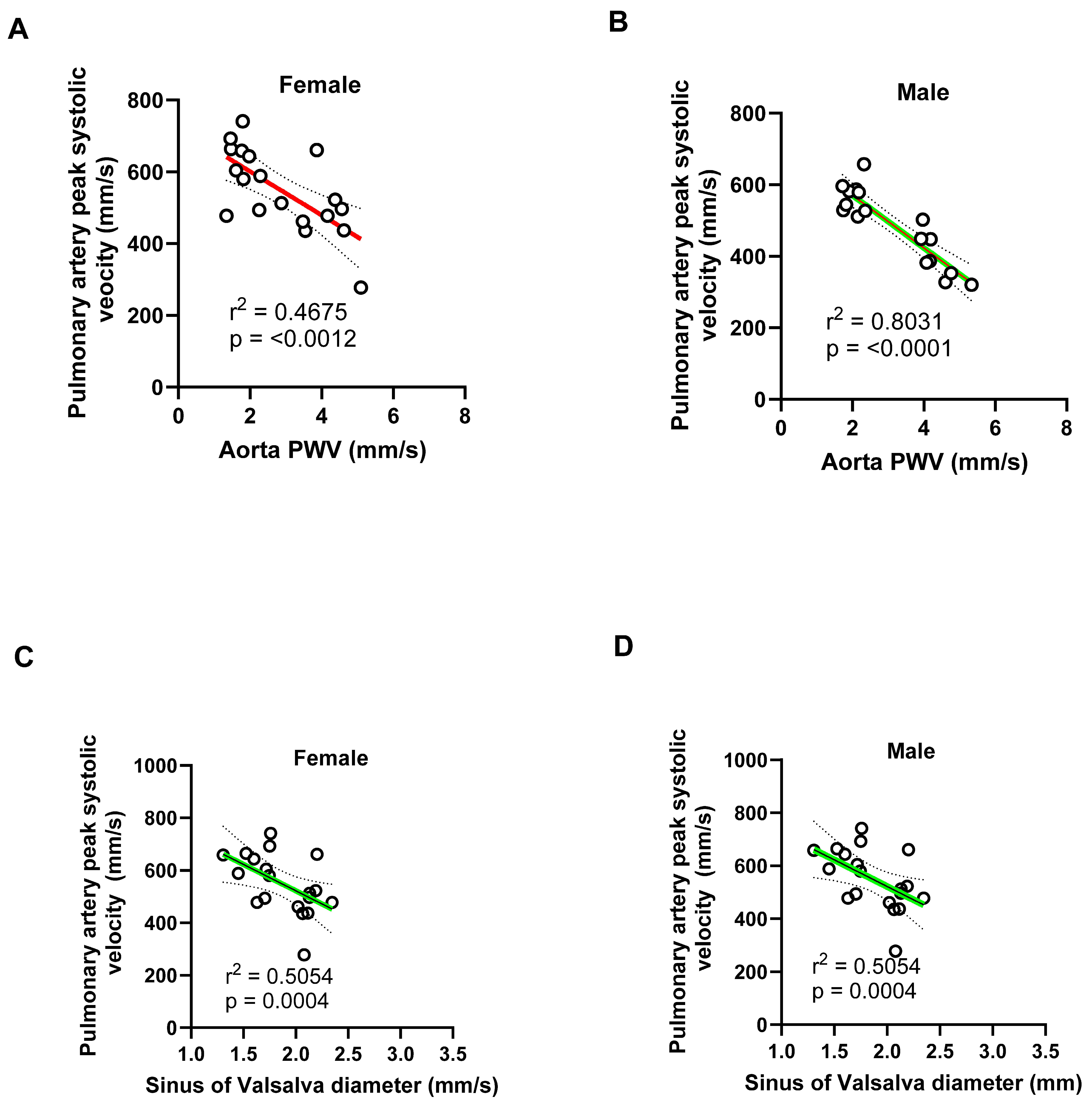

While no significant changes were detected in the coronary or renal arteries, the reduction in pulmonary artery PSV highlights the systemic nature of vascular dysfunction in this model. Pulmonary involvement in MFS includes structural abnormalities such as emphysema and an increased risk of spontaneous pneumothorax [

23,

36,

37,

38]. These complications are believed to arise from the defective connective tissue associated with

FBN1 mutations, leading to weakened alveolar walls and reduced lung elasticity. Such structural changes can elevate pulmonary vascular resistance, potentially contributing to pulmonary hypertension and altered pulmonary artery flow dynamics. Moreover, studies have reported dilation of the main pulmonary artery in a significant proportion of MFS patients. For instance, one study found that 69.4% of MFS patients exhibited pulmonary artery dilation, with 15.3% developing aneurysms [

39]. Although the clinical implications of pulmonary artery dilation in MFS are not fully understood, such vascular alterations could influence pulmonary hemodynamics and contribute to the observed decrease in PSV.

The observed reduction in PSV may also reflect impaired right ventricular function. Research indicates that individuals with MFS can experience the right ventricular systolic dysfunction, which could lead to decreased blood flow velocity through the pulmonary artery [

36]. Additionally, skeletal deformities common in MFS, such as scoliosis and chest wall abnormalities, can compromise respiratory mechanics and contribute to restrictive lung disease. These musculoskeletal issues may further exacerbate pulmonary complications and impact pulmonary artery hemodynamics [

40,

41]. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive pulmonary assessments in MFS patients to detect and manage potential complications early.

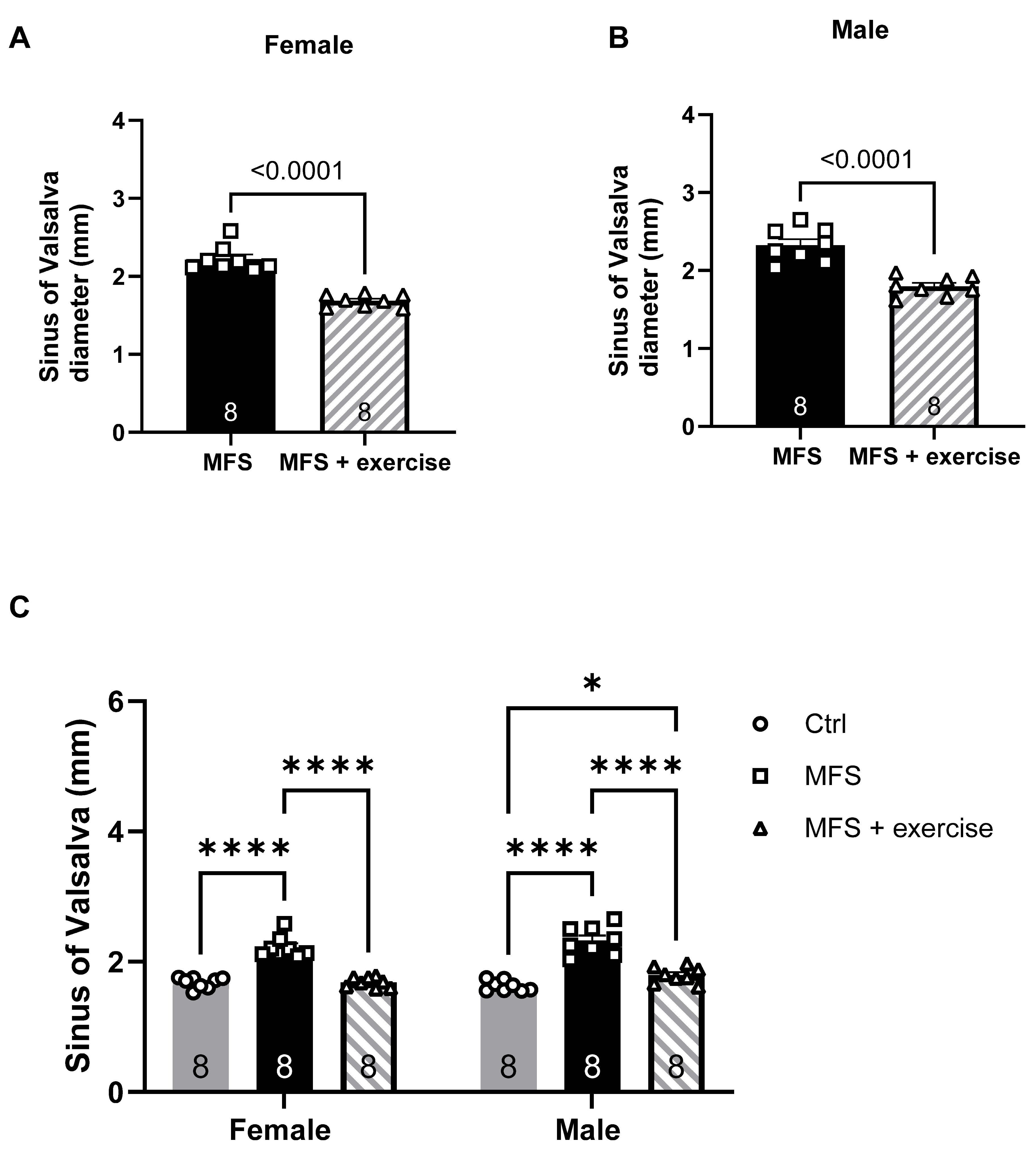

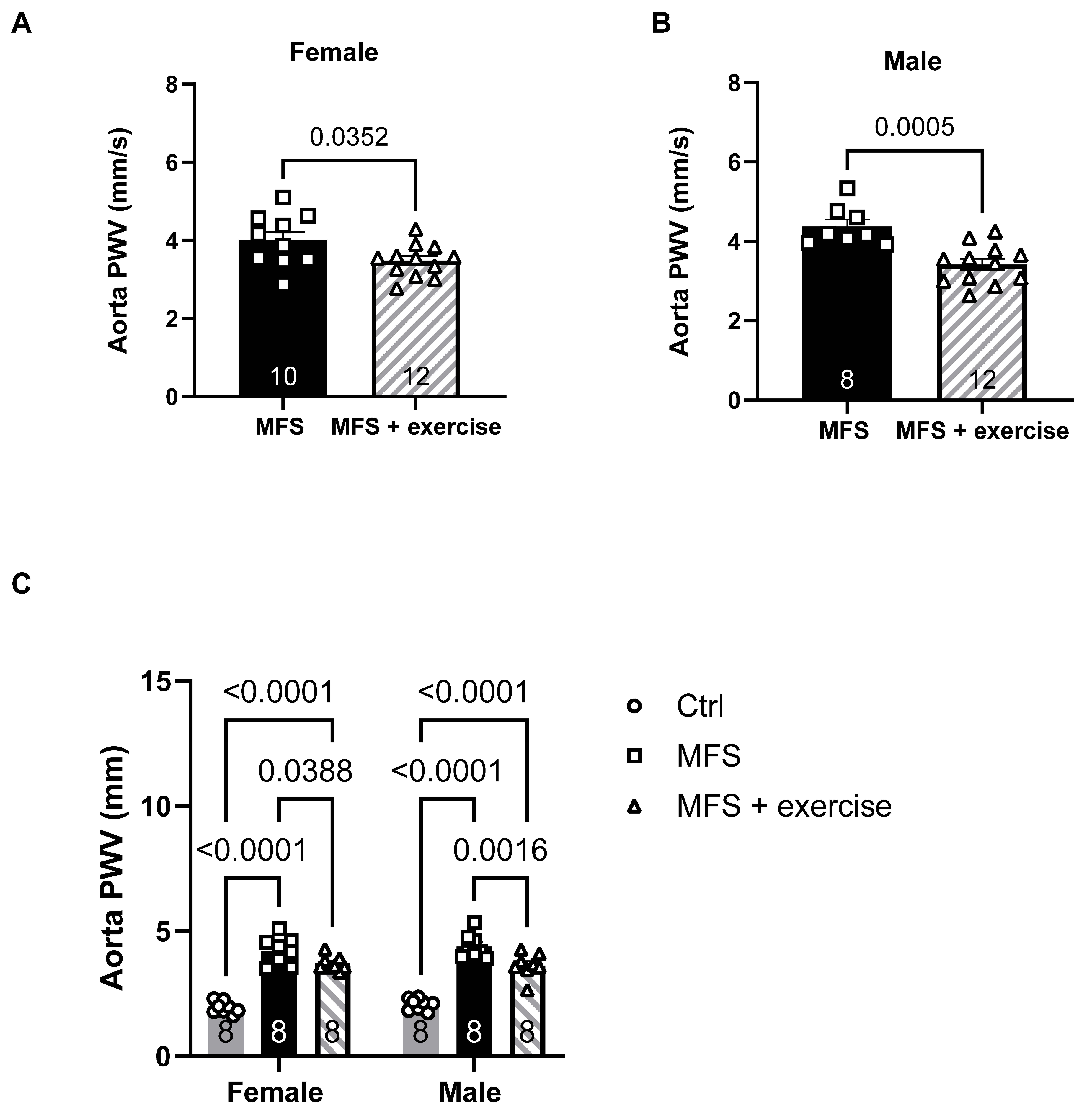

Exercise training proved to be a promising intervention for mitigating cardiovascular pathology in MFS mice [

8,

10,

12,

27]. The results of our study clearly confirm that mild aerobic exercise significantly reduces both aortic root diameter and PWV, suggesting improved aortic compliance and decreased vascular wall stiffness. Particularly, in female MFS mice, the aortic root diameter was restored to control levels following exercise training, suggesting that exercise may fully reverse some of the pathological structural changes associated with the condition in a sex-dependent manner. These results align with previous studies in other animal models and human populations, where exercise has been shown to improve vascular function, enhance endothelial health, and reduce arterial stiffness [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

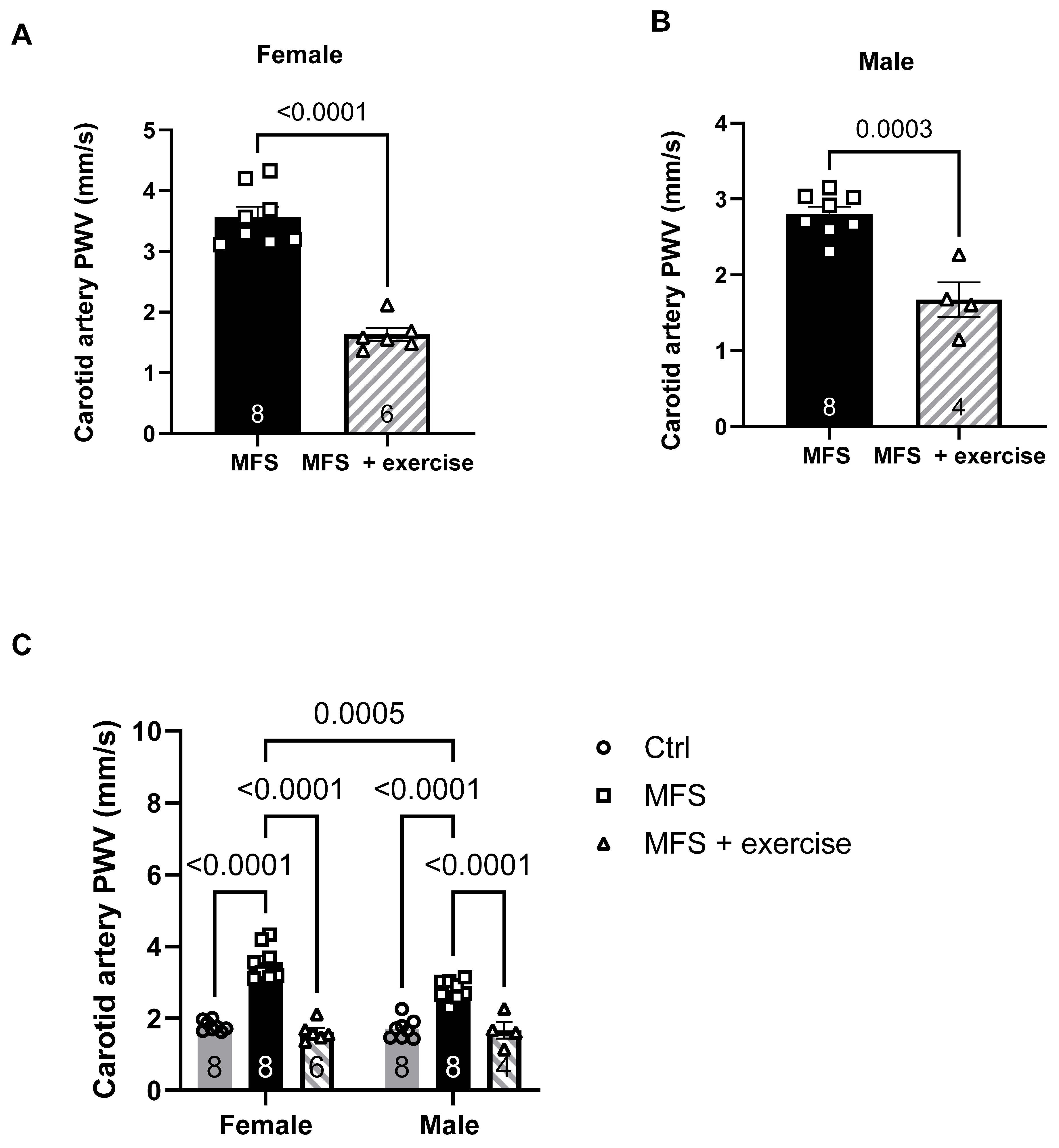

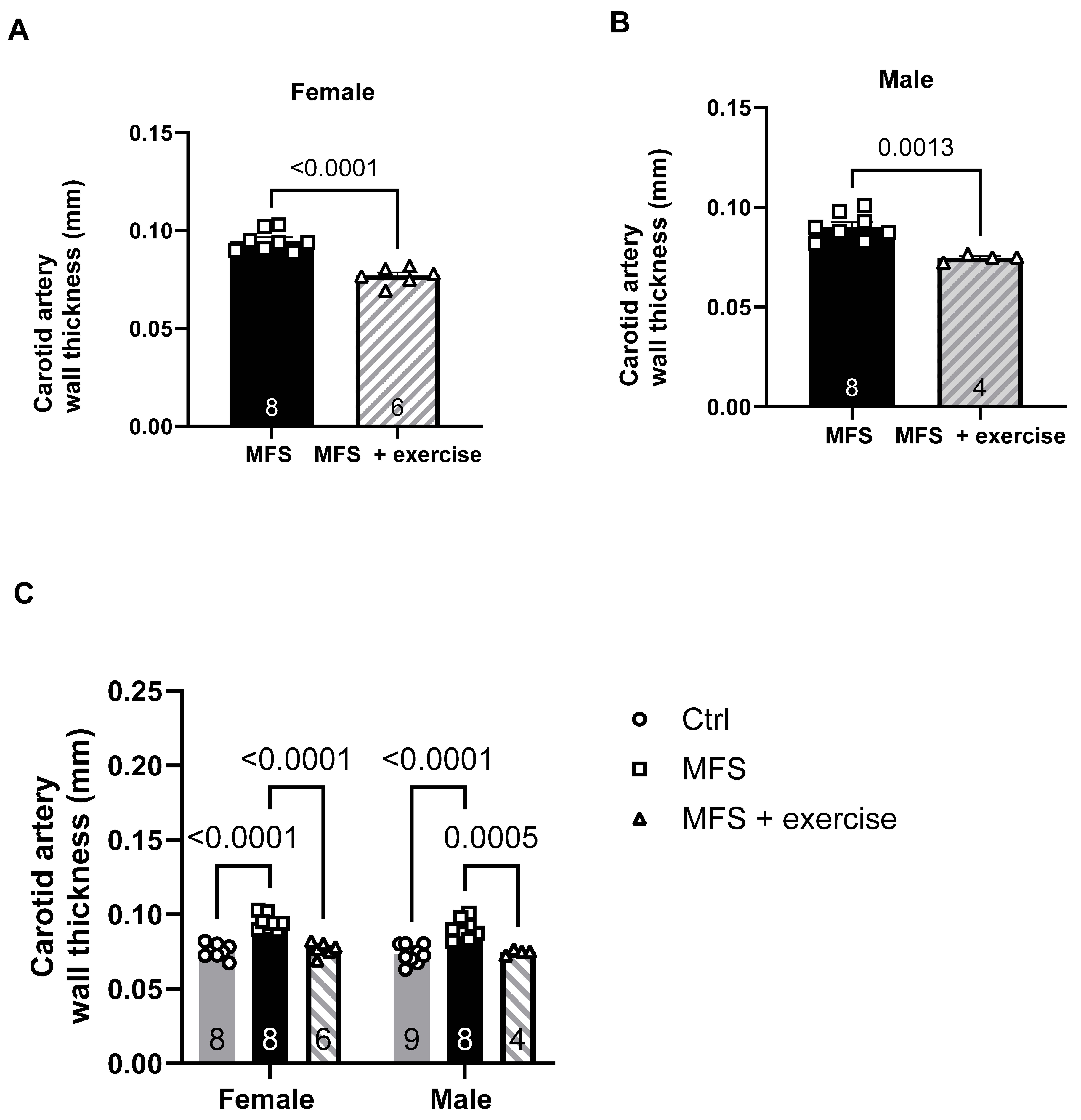

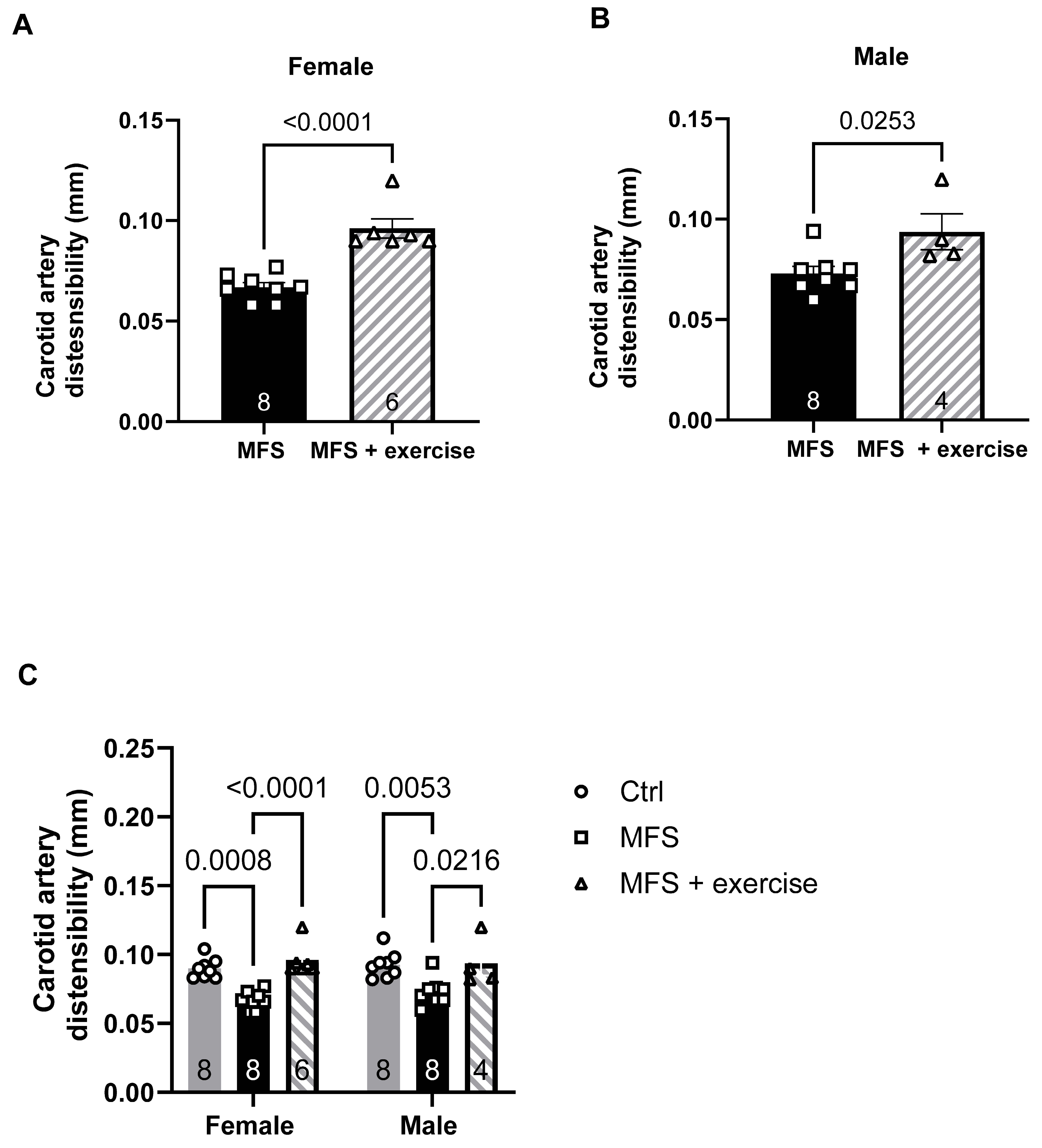

48,

49]. The beneficial effects of exercise extended to carotid artery function as well. Exercise training reduced PWV, decreased wall thickness, and improved distensibility of left common carotid artery in both male and female MFS mice. These improvements paralleled the observed benefits in aortic function, further supporting the therapeutic potential of exercise for managing vascular health in MFS.

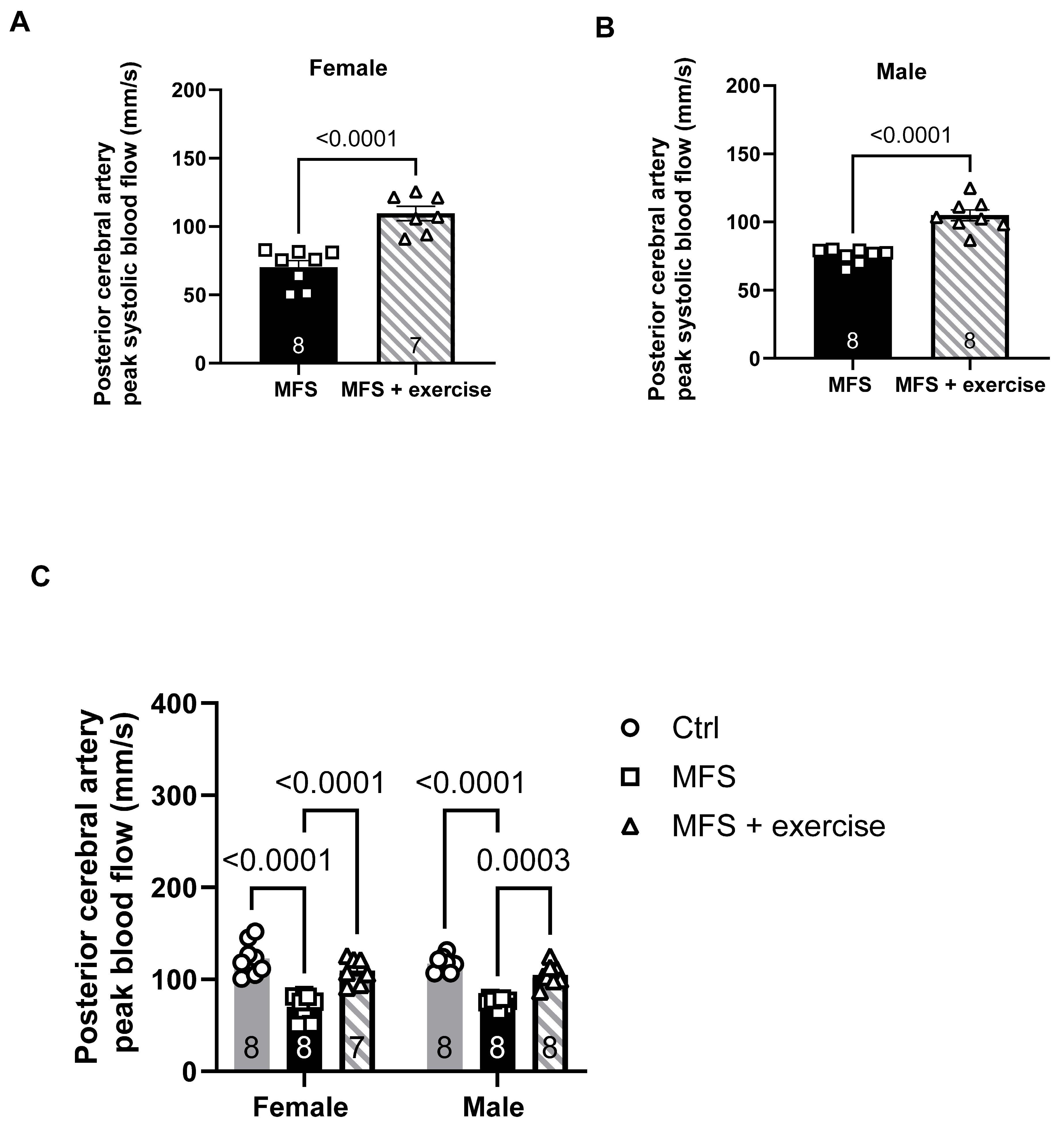

Furthermore, exercise training improved peak systolic velocity in the posterior cerebral artery, restoring it to control levels in female mice. This result suggests that exercise may enhance cerebral perfusion and provide protection against potential cerebrovascular complications associated with MFS. Considering the increased risk of stroke and other cerebrovascular events in individuals with MFS, this finding highlights the importance of maintaining healthy cerebral circulation as a key aspect of disease management.

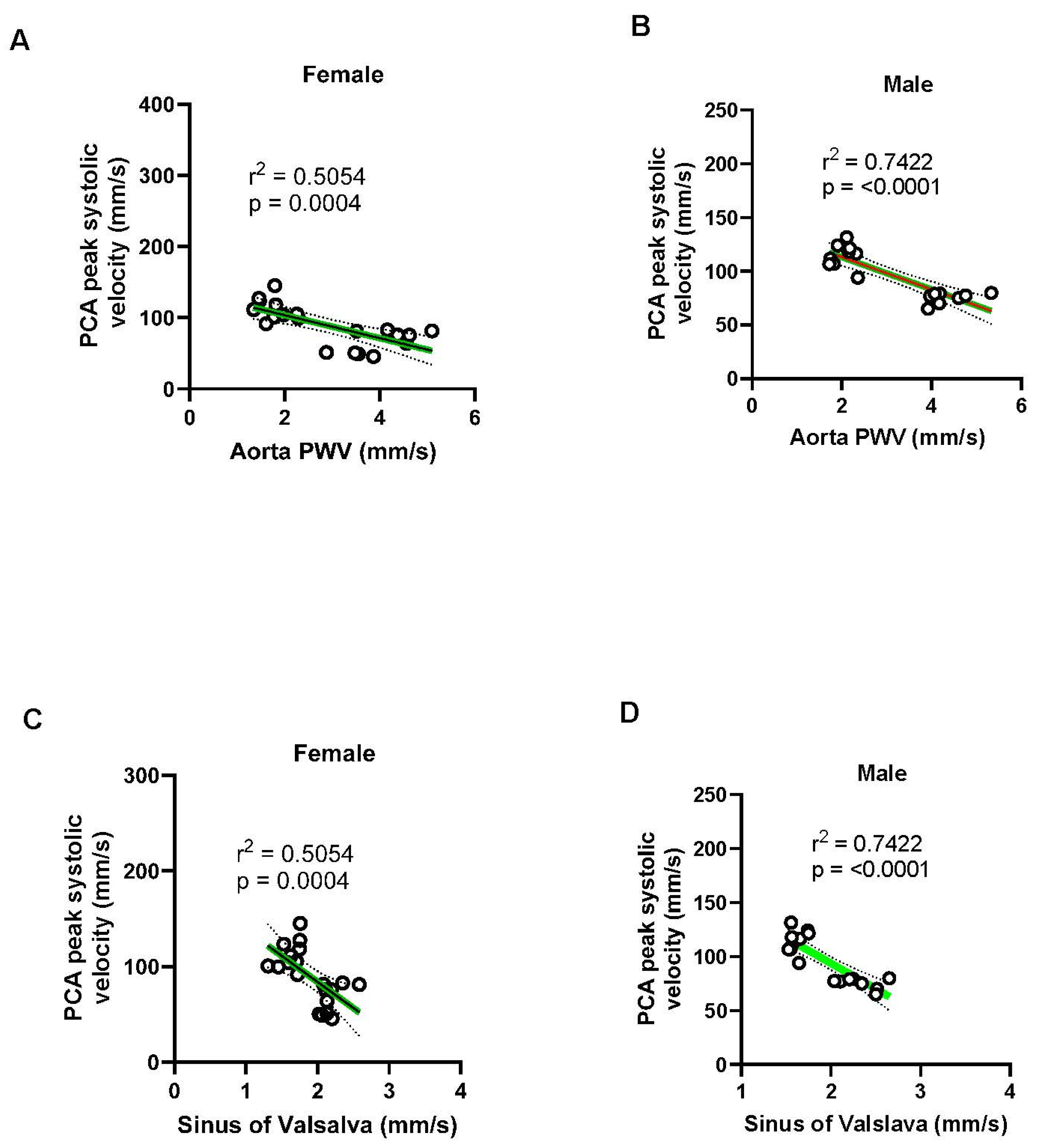

Sex-specific differences were also evident in the relationships between cardiovascular parameters, with stronger associations observed between aortic PWV, aortic root diameter at the sinus of Valsalva, and blood flow velocity in males compared to females. These differences may reflect inherent biological variations in vascular function between sexes, as well as potential differences in their responses to exercise training. For instance, while the relationship between aortic PWV and cerebral blood flow was more robust in males, the improvement in carotid artery function following exercise was more pronounced in females, suggesting that the two sexes may drive distinct benefits from exercise. Studies have shown that hypertension and coronary artery disease are more prevalent in men and postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. This difference is partly attributed to gender-based variations in vascular tone and the potential vascular protective effects of female sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone. The male sex hormone testosterone may also influence vascular function. Receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone have been identified in the blood vessels of humans and other mammals and are located in the plasmalemma, cytosol, and nuclei of various vascular cells, including endothelial and smooth muscle cells.

The interaction of sex hormones with cytosolic and nuclear receptors can trigger long-term genomic effects—such as promoting endothelial cell growth and inhibiting smooth muscle cell proliferation. In contrast, activation of membrane-bound (plasmalemmal) sex hormone receptors may lead to rapid, non-genomic effects that stimulate endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation mechanisms, including the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP, prostacyclin-cyclic AMP, and hyperpolarization pathways. Additionally, sex hormones may exert endothelium-independent effects by inhibiting signaling pathways involved in vascular smooth muscle contraction, such as intracellular calcium levels and protein kinase C activity. Together, these hormone-induced mechanisms of promoting vascular relaxation and reducing smooth muscle contraction may contribute to the observed gender differences in vascular tone and support the potential vascular benefits of hormone replacement therapy in individuals with natural or surgically induced hormone deficiencies [

44,

50,

51]. Exercise increases blood flow and laminar shear stress, which stimulates NO production by the endothelium. NO then acts as a vasodilator, relaxing blood vessels and improving blood flow. Mild exercise improves endothelium-mediated nitric oxide (NO) production and vasorelaxation, but the magnitude of this effect can vary between sexes [

46,

52,

53]. These findings underscore the need for personalized approaches in the management of MFS, especially in clinical settings where sex-specific factors may influence treatment outcomes.

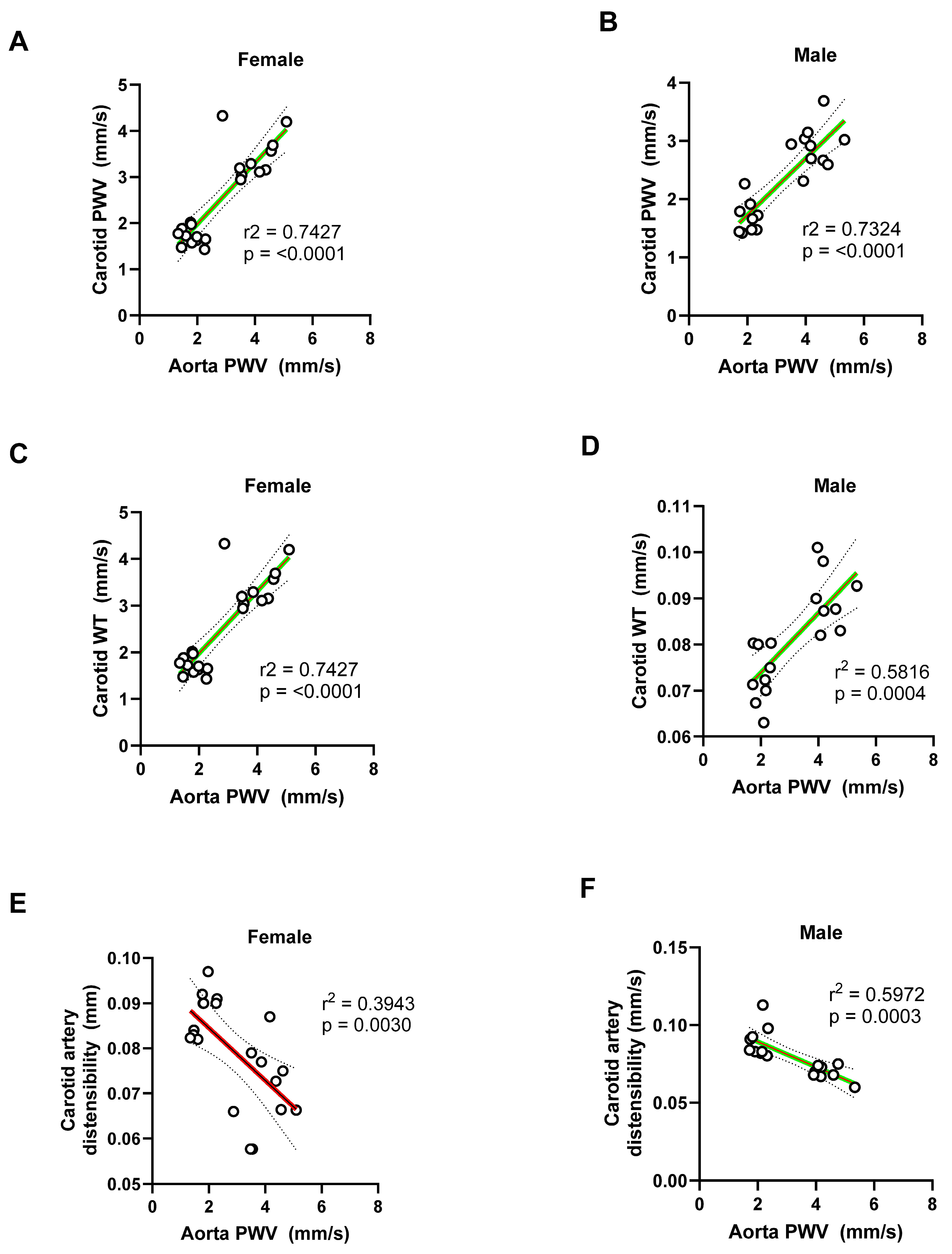

Our study also identified significant associations between aortic parameters and carotid artery function, particularly in females. The strong correlation between the sinus of Valsalva diameter and carotid artery PWV and wall thickness, along with a moderate relationship with distensibility, suggests that changes in the aorta may serve as reliable predictors of carotid artery function in MFS. These findings are crucial for understanding how aortic pathology in MFS can extend to other vascular territories, potentially leading to widespread vascular dysfunction.

The molecular mechanisms responsible for the observed improvements in vascular function were not investigated in this study, but our previous data on MFS and exercise showed that mild aerobic exercise decreased phosphorylated Smad proteins (p-Smads), which are involved in the TGF-β signaling pathway, without necessarily decreasing the total levels of TGF-beta. This means that exercise can affect the downstream signaling of TGF-β without altering the overall amount of the signaling molecules. Further research is necessary to uncover the signaling pathways and molecular factors driving exercise-induced vascular remodeling, which could inform and enhance therapeutic strategies for MFS and other related connective tissue disorders.

Figure 1.

Aortic root diameter measurements at the Sinus of Valsalva. A) Representative B-mode ultrasound image showing measurements of three aortic root diameters in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Representative B-mode ultrasound image illustrating the three aortic root diameters in a 7-month-old mouse with MFS. C) Ultrasound analysis reveals a significant increase in the diameter of the Sinus of Valsalva in both male and female MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 1.

Aortic root diameter measurements at the Sinus of Valsalva. A) Representative B-mode ultrasound image showing measurements of three aortic root diameters in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Representative B-mode ultrasound image illustrating the three aortic root diameters in a 7-month-old mouse with MFS. C) Ultrasound analysis reveals a significant increase in the diameter of the Sinus of Valsalva in both male and female MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 2.

Pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements of thoracic aorta. A) PW Doppler tracing of the ascending (left panel) and descending aorta (right panel). B) Pulse wave Doppler tracing of the ascending and descending aorta. C) Thoracic aorta PWV, an indicator of aortic wall stiffness, exhibited a significant increase in 7-month-old mice with MFS compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 2.

Pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements of thoracic aorta. A) PW Doppler tracing of the ascending (left panel) and descending aorta (right panel). B) Pulse wave Doppler tracing of the ascending and descending aorta. C) Thoracic aorta PWV, an indicator of aortic wall stiffness, exhibited a significant increase in 7-month-old mice with MFS compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 3.

Measurements of PWV of left common carotid artery (LCCA). A) Doppler mode, ultrasound image of the left common carotid artery. B) PWV was significantly increased in both male and female MFS mice compared to the age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 3.

Measurements of PWV of left common carotid artery (LCCA). A) Doppler mode, ultrasound image of the left common carotid artery. B) PWV was significantly increased in both male and female MFS mice compared to the age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 4.

Ultrasound measurements of the LCCA wall thickness and distensibility. A) M-Mode ultrasound view of the LCCA in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Data showed a significant increase in the wall thickness and C) a significant decrease in the distensibility in LCCA in MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 4.

Ultrasound measurements of the LCCA wall thickness and distensibility. A) M-Mode ultrasound view of the LCCA in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Data showed a significant increase in the wall thickness and C) a significant decrease in the distensibility in LCCA in MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 5.

Measurements of the carotid artery peak systolic velocity (PSV). A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the coronary artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Data showed no significant changes in coronary artery peak systolic velocity between MFS and age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 5.

Measurements of the carotid artery peak systolic velocity (PSV). A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the coronary artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Data showed no significant changes in coronary artery peak systolic velocity between MFS and age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Figure 6.

Measurement of the pulmonary artery peak blood flow velocity. A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the coronary artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) A significant decrease was observed in the pulmonary artery peak systolic velocity in MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl in groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 6.

Measurement of the pulmonary artery peak blood flow velocity. A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the coronary artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) A significant decrease was observed in the pulmonary artery peak systolic velocity in MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl in groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 7.

Ultrasound measurements of the right renal artery peak systolic velocity. A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the right renal artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) There was no significant difference in the peak systolic velocity in the right renal artery between MFS and age- and sex-matched groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 7.

Ultrasound measurements of the right renal artery peak systolic velocity. A) Ultrasound PW Color Doppler mode view of the right renal artery in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) There was no significant difference in the peak systolic velocity in the right renal artery between MFS and age- and sex-matched groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 8.

Measurements of the posterior cerebral artery peak systolic velocity. A) Ultrasound, B-Mode color Doppler view of the left and right posterior cerebral arteries in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Peak systolic velocity of the posterior cerebral artery was significantly decreased in male and female MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 8.

Measurements of the posterior cerebral artery peak systolic velocity. A) Ultrasound, B-Mode color Doppler view of the left and right posterior cerebral arteries in a 7-month-old Ctrl mouse. B) Peak systolic velocity of the posterior cerebral artery was significantly decreased in male and female MFS mice compared to age- and sex-matched Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 9.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the aortic diameter. A) Exercise training significantly improved the aortic diameter in female MFS mice, bringing the values back to the levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl mice. B) Exercise training partially but significantly improved the aortic diameter in mice MFS mice. C) There were no significant differences between male and female sexes. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 9.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the aortic diameter. A) Exercise training significantly improved the aortic diameter in female MFS mice, bringing the values back to the levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl mice. B) Exercise training partially but significantly improved the aortic diameter in mice MFS mice. C) There were no significant differences between male and female sexes. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 10.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the aortic PWV. A) Exercise training significantly improved aortic wall elasticity in female MFS mice. B) Exercise training significantly improved aortic wall elasticity in male MFS mice. C) In both male and female MFS groups, exercise training did not fully reverse aortic wall functional integrity to levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 10.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the aortic PWV. A) Exercise training significantly improved aortic wall elasticity in female MFS mice. B) Exercise training significantly improved aortic wall elasticity in male MFS mice. C) In both male and female MFS groups, exercise training did not fully reverse aortic wall functional integrity to levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 11.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the PCA peak blood flow velocity. In vivo ultrasound measurements showed that exercise improved the peak blood flow velocity in the PCA of both female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) In both female and male MFS groups, exercise training effectively restored peak systolic velocity to levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 11.

Effects of mild aerobic exercise on the PCA peak blood flow velocity. In vivo ultrasound measurements showed that exercise improved the peak blood flow velocity in the PCA of both female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) In both female and male MFS groups, exercise training effectively restored peak systolic velocity to levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 12.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery PWV. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery PWV in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully restored carotid artery wall elasticity in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in healthy Ctrl groups. In addition, when compared to age-matched male groups, female MFS mice showed a higher carotid artery stiffness, indicating a sex-dependent effect. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 12.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery PWV. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery PWV in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully restored carotid artery wall elasticity in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in healthy Ctrl groups. In addition, when compared to age-matched male groups, female MFS mice showed a higher carotid artery stiffness, indicating a sex-dependent effect. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 13.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery wall thickness. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery wall thickness in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully normalized carotid artery wall thickness in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 13.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery wall thickness. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery wall thickness in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully normalized carotid artery wall thickness in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 14.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery wall distensibility. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery wall distensibility in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully normalized carotid artery wall distensibility in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 14.

Effect of mild aerobic exercise on the carotid artery wall distensibility. Exercise significantly improved the carotid artery wall distensibility in female (A) and male (B) MFS mice. C) Mild exercise fully normalized carotid artery wall distensibility in both male and female MFS groups to the levels observed in age- and sex-matched healthy Ctrl groups. (Mean ± SEM, p < 0.05 is considered as significant).

Figure 15.

Inverse correlation between PCA peak blood flow and aortic root dilation and wall stiffness in male and female mice. A) Linear regression analysis showed a moderate inverse relationship between the aortic PWV and the PCA peak blood flow in the female group (R2 = 0.5054). B) There is a stronger inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic PWV in the male group (R2 = 0.7422). C) Linear regression analysis showed a moderate inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic root diameters in the female group (R2 = 0.5054). D) There is a stronger inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic root diameters in the male group (R2 = 0.7422).

Figure 15.

Inverse correlation between PCA peak blood flow and aortic root dilation and wall stiffness in male and female mice. A) Linear regression analysis showed a moderate inverse relationship between the aortic PWV and the PCA peak blood flow in the female group (R2 = 0.5054). B) There is a stronger inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic PWV in the male group (R2 = 0.7422). C) Linear regression analysis showed a moderate inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic root diameters in the female group (R2 = 0.5054). D) There is a stronger inverse relationship between the PCA peak blood flow and aortic root diameters in the male group (R2 = 0.7422).

Figure 16.

Linear regression plots between the aortic PWV carotid artery parameters. (A-B) Carotid PWV showed a strong positive correlation with aortic PWV in both sexes (females: R² = 0.7427; males: R² = 0.7324), indicating that systemic arterial stiffening is associated with local carotid stiffening. (C-D) Carotid wall thickness also positively correlated with aortic PWV (females: R² = 0.7427; males: R² = 0.5816), with stronger associations observed in females. (E-F) Carotid artery distensibility index negatively correlated with aortic PWV in both sexes, suggesting reduced carotid compliance with increasing aortic stiffness (females: R² = 0.3943; males: R² = 0.5972, with the relationship being more pronounced in males. These data highlight sex-dependent differences in the impact of aortic stiffness on carotid artery function and structure.

Figure 16.

Linear regression plots between the aortic PWV carotid artery parameters. (A-B) Carotid PWV showed a strong positive correlation with aortic PWV in both sexes (females: R² = 0.7427; males: R² = 0.7324), indicating that systemic arterial stiffening is associated with local carotid stiffening. (C-D) Carotid wall thickness also positively correlated with aortic PWV (females: R² = 0.7427; males: R² = 0.5816), with stronger associations observed in females. (E-F) Carotid artery distensibility index negatively correlated with aortic PWV in both sexes, suggesting reduced carotid compliance with increasing aortic stiffness (females: R² = 0.3943; males: R² = 0.5972, with the relationship being more pronounced in males. These data highlight sex-dependent differences in the impact of aortic stiffness on carotid artery function and structure.

Figure 17.

Linear regression plots between the aortic root diameter and the carotid artery parameters in male and female mice. (A-B) Carotid city (PWV) was positively correlated with aortic root diameter in both females (R² = 0.5546) and males (R² = 0.7234), suggesting that dilation of the aortic root is associated with increased carotid stiffness. (C-D) Carotid artery wall thickness also positively correlated with aortic root diameter in both sexes, with stronger correlation in males (females: Rr² = 0.7335; males: R² = 0.8678, p < 0.0001), indicating vascular remodeling linked to aortic root enlargement. (E-F) Carotid artery distensibility index showed an inverse correlation with aortic diameter, indicating reduced carotid compliance with larger sinus diameters. This relationship was modest in females (R² = 0.3296) and more pronounced in males (R² = 0.5834).

Figure 17.

Linear regression plots between the aortic root diameter and the carotid artery parameters in male and female mice. (A-B) Carotid city (PWV) was positively correlated with aortic root diameter in both females (R² = 0.5546) and males (R² = 0.7234), suggesting that dilation of the aortic root is associated with increased carotid stiffness. (C-D) Carotid artery wall thickness also positively correlated with aortic root diameter in both sexes, with stronger correlation in males (females: Rr² = 0.7335; males: R² = 0.8678, p < 0.0001), indicating vascular remodeling linked to aortic root enlargement. (E-F) Carotid artery distensibility index showed an inverse correlation with aortic diameter, indicating reduced carotid compliance with larger sinus diameters. This relationship was modest in females (R² = 0.3296) and more pronounced in males (R² = 0.5834).

Figure 18.

Negative correlation between pulmonary artery systolic blood flow and aortic stiffness and diameter in male and female mice. (A-B) Pulmonary artery (PA) peak systolic blood velocity negatively correlated with aortic wall stiffness (PWV) in both females (R² = 0.4875) and males (R² = 0.8031), indicating that increased aortic wall stiffness is associated with reduced pulmonary flow velocity, with a stronger relationship observed in males. (C-D) Similarly, PA peak systolic blood velocity negatively correlated with aortic root diameters in both sexes (females: R² = 0.5054; males: R² = 0.5854), suggesting that progressive dilation of the aortic root impairs pulmonary hemodynamics.

Figure 18.

Negative correlation between pulmonary artery systolic blood flow and aortic stiffness and diameter in male and female mice. (A-B) Pulmonary artery (PA) peak systolic blood velocity negatively correlated with aortic wall stiffness (PWV) in both females (R² = 0.4875) and males (R² = 0.8031), indicating that increased aortic wall stiffness is associated with reduced pulmonary flow velocity, with a stronger relationship observed in males. (C-D) Similarly, PA peak systolic blood velocity negatively correlated with aortic root diameters in both sexes (females: R² = 0.5054; males: R² = 0.5854), suggesting that progressive dilation of the aortic root impairs pulmonary hemodynamics.