1. Introduction

For patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), whilst there has been an improvement in the relative 5-year survival rate from 50% during the mid-1970s to around 65% today, over the past 25 years this rate has remained static. A key reason for this is acquired drug resistance to the agents used in the two most common CRC treatment regimens, FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin (Oxa) and leucovorin) and FOLFIRI (5-FU, irinotecan (Iri) and leucovorin).

Although some of the mechanisms of resistance to the drugs used in CRC treatment are well known, for example increased thymidylate synthetase expression in the case of 5-FU, reduced topoisomerase expression for Iri, or decreased expression of transporters belonging to the SLC22 family for Oxa [

1,

2,

3], there is still much that is undiscovered. Intracellular transport mechanisms have come under attention as having a possible role in drug resistance in cancer such as copper transport systems for platinum compounds [

4], or transient receptor channel proteins [

5]. One such mechanism which has had attention is the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) protein family [

6,

7].

ESCRTs are a family of proteins that are involved in multiple physiological and biological processes such as cell division and degradation of membrane proteins, membrane repair and viral budding. One of the main functions of ESCRTs is to sort ubiquitinated proteins into late endosomes intralumenal vesicles to form multivesicular bodies (MVBs), and later fuse with lysosomes, targeting degradation of these proteins. ESCRT complex proteins mediate this primary sorting event and regulate the stability of receptors at the surface of cells [

8]. Besides their physiological functions, many diseases have been associated with misregulation and mutations in ESCRT machinery including cancer, infection, neurodegenerative diseases, and wound healing [

9]. The ESCRT family consists of 4 different complexes of proteins: ESCRT-0 (HRS and STAM-1); ESCRT-I (TSG101), ESCRT-II and ESCRT–III (CHMP’s) as well as accessory proteins such as Alix and the Vacuolar Protein Sorting-Associated Proteins VPS4A and VPS4B. VPS4 proteins are ATPases that mediate the final steps of membrane fission and protein sorting as part of the ESCRT machinery. They disassemble ESCRT-III filaments, which are vital for forming MVBs and the release of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), ultimately leading to the sorting and degradation of various cellular proteins, including those involved in cancer development and progression [

10].

In terms of cancer, whilst there are multiple studies which have covered the involvement of ESCRT machinery in biological processes, the role in cancer is less extensively investigated, and the underlying molecular mechanisms have been elucidated for only a few cases [

11,

12,

13]. Large-scale screening for cancer vulnerabilities within the Sanger’s Project Score [

14] and the DRIVE projects [

15] showed that some cancer cell lines had greater sensitivity when VPS4A expression was dysregulated [

16]. Some studies regarding ESCRT-III members have demonstrated that CHMP2A sensitized glioblastoma stem cells to death mediated by natural killer cells [

17]. Additionally, CHMP2A inhibition led to activation of caspase 8-induced apoptosis in osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma cells [

18]. However, so far, the link between the specific ESCRT family members and resistance to chemotherapy has not been extensively investigated.

Therefore, in this study studies were carried out exploring the potential of ESCRTs as modulator of drug resistance, identifying a family member consistently overexpressed in a human CRC cell line panel, VPS4A. Expression in clinical samples, and the effect of VPS4A knockdown and inhibition on response to drugs routinely used to treat CRC in the clinic was then explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

A panel of ten CRC cell lines (COLO 205, DLD-1, HCC2998, HCT116, HT29, HT55, KM12, LS174T, SW480 and SW620), plus a normal intestinal epithelial cell line, HIEC-6 were used in these studies.DLD-1 and HIEC-6 were obtained from ATCC (LGC Standards, Teddington, UK), HT-55, SW480 and LS174T from ECACC (Salisbury, UK), and COLO 205, HT29, HCC2998, HCT116, KM12 and SW620 from the National Cancer Institute Department of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis Tumour Repository (Frederick, USA).

The cells were all maintained in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 2 mmol/L of L-glutamine (all from Merck, Gillingham, UK), apart from HIEC-6 which was grown in Opti-Mem I reduced serum Medium supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM GlutaMax, 10 ng/ml Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (all from Thermofisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK). All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Severn Biotech, Kidderminster, UK) was used for washing steps.

Oxaliplatin (Oxa), 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Irinotecan (Iri) and Aloperine (Alo) were all purchased from Selleckchem (Waltham Abbey, UK). Oxa, 5-FU and Alo were initially prepared as a 17mM, 50mM and 27mM stock solutions in sterile distilled water respectively, whilst Iri was initially prepared as a 21mM stock in DMSO. In all cases aliquots were stored at -20⁰C until use.

The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry in this study: rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS4 A/B antibody (#SAB4200025, Merck); rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS4A antibody (#14272-AP, Proteintech, Manchester, UK); rabbit polyclonal anti-CHMP6 antibody (#ab76929, abcam, Cambridge, UK); recombinant rabbit monoclonal anti-TSG101 (#ab125011, abcam); rabbit polyclonal anti-CHMP2B antibody (#ab33174, abcam); rabbit polyclonal anti-STAM2 antibody (#HPA035528, Atlas antibodies, Stockholm, Sweden); rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS36 antibody (#HPA043947, Atlas antibodies); rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS37A antibody (#PA5-55160, Thermofisher Scientific); mouse monoclonal anti-VPS25 antibody (Santa Cruz, Middlesex, UK); rabbit polyclonal anti-ALIX antibody (#12422-1-AP, Proteintech); mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (Proteintech), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (#10494-1-AP, Proteintech). All antibodies were aliquoted and stored in -20⁰C until use.

2.2. Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed with 1 X RIPA buffer (Merck) , supplemented with cOmplete™, EDTA-free Protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck). Protein concentration was measured using BCA Kit (Thermofisher Scientific) Protein expression analysis results was carried out by immunoblotting. A sample of whole cell lysate from each cell line was separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in 10% Acrylamide gels using a NuPAGE 4x LDS sample buffer (Thermofisher Scientific), followed by electroblotting onto PVDF blotting membrane (0.45 μm) (Merck) using constant voltage 100 V for 2 hours. Membranes were blocked in 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (VWR, Leicestershire, UK). Rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS4 A/B antibody (#SAB4200025, Merck) at 1:1000 dilution and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (Proteintech) at 1:5000 dilution were used for protein expression . IRDye® 800CW Goat anti-Rabbit IgG and IRDye® 680RD Donkey anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibodies were used at 1:5000 dilution (LI-COR Biosciences, Cambridge, UK). Finally, the membrane was visualized, and Images taken using Odyssey® Imagers (LI-COR Biosciences). Densitometric analysis was performed using Empiria Studio® Software (LI-COR Biosciences).

2.3. Clinical Material

The study protocol was approved by the University of Bradford’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (reference: application/21/107). Ethical approval was given by Leeds (East) Research Ethics Committee, UK, reference 22/YH/0111.

Archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) diagnostic samples from colorectal cancer patients taken prior to the commencement of palliative chemotherapy were provided by Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. The clinical details for the patients included in the study are given in

Table 1.

On receipt of the archival FFPE blocks, 5µm-thick sections were taken using a Leica microtome and collected onto 3-Aminoproyl triethoxysilane (APES; Merck) coated microscope slides. After drying, slides were stored in a dust-free environment at room temperature until use.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemistry protocol was optimized such that the same steps were followed for each biomarker, with the only difference being the concentration of the primary biomarker antibody. Unless stated, all steps were carried out at room temperature. Samples were initially dewaxed and rehydrated through a series of xylenes and ethanols (Thermofisher Scientific) through to distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was then quenched in 1% Hydrogen Peroxide (Merck) in distilled water for 30 minutes followed by 2 washes in PBS. Antigen retrieval was then carried out by immersing the slides in Sodium Citrate Buffer, pH6.0, and microwaving at a medium setting for 15 minutes and then allowing them to cool for 30 minutes before proceeding to the next step. After 2 further washes in PBS, blocking with 1.5% Normal Goat Serum in PBS (NGS; abcam) was carried out for 20 minutes, followed by administration of the optimized concentration of the specific primary antibody, polyclonal anti-VPS4A (Proteintech) diluted 1:100 in the blocking serum. Sections were then incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4⁰C. The next day, samples were washed twice in PBS followed by incubation with biotinylated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG secondary antibody (BP-9100-50, Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK), diluted 1:100 in PBS for 30 minutes. After 2 subsequent washes in PBS, 30 minutes incubation in avidin-biotin complex reagent (Vector Laboratories), and a further couple of PBS washes, a DAB staining kit (Vector Laboratories) was applied for between 3 and 5 minutes. Slides were then washed in running tap water, Harris’s Haematoxylin counterstain (Merck) applied for 20 seconds, followed by further washing in tap water, immersion in Scott’s Tap Water (Merck) for 2 minutes and a further tap water wash. Slides were then dehydrated and mounted as described in the previous section.

2.5. Microscopy and Image Capture

Sections were viewed using a Leica DMLS Microscope with images captured using a Leica DFC295 digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, UK) and Mosaic imaging software (Tucsen V2.4). Images were captured as uncompressed JPEG files for optimal image quality.

2.6. Cell Knockdown

The shVPS4A (#VB181214-1076rkx) and shScrambled (SCR; #VB181214-1079yke) shRNA plasmids used in this study were designed using the Vector Builder online tool (

www.vectorbuilder.com) and purchased from Vector Builder (Chicago, USA). Plasmids were provided as E.coli stocks and plasmid extraction was performed usig GenElute™ Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Merck). Next, optimum plasmid concentration was determined and verified by immunoblotting. Cells were transfected with 500 or 250 ng of sh RNA respectively for 48 hours using TransIT-X2

® Dynamic Delivery System (Mirus, Cambridge, UK). Later, stable transfection was obtained using puromycin selection, where cells were treated with 0.6 ug/ml of Puromycin for 5 days [

19]. Next, clonal selection was performed using a standardized dilution protocol [

20] where a cell suspension of ≤ 10 cells/ml was prepared, and 100 µl of that was seeded into each well of a 96 well culture plate, which was then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO

2 for 2 weeks or until visible colonies were formed. Where wells contained single colonies, these were then collected, expanded, and tested for protein expression using immunoblotting, and the clones which exhibited the largest knockdown of VPS4A expression were selected for use in the experiments.

2.7. EGFR Assay

To confirm the function of ESCRT complex, an EGFR assay where lysosomal degradation of Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is monitored following induction by the agonist Human Epidermal growth factor (EGF) was carried out as described previously [

21]. SW480/shVPS4A and SW480/shSCR cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 4X10

5 cells/ well, and left to adhere overnight. The next day, cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and then incubated with 50 ng/ml of human EGF (Thermofisher Scientific) for 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 or 120 minutes. The media was then removed and cells were collected by scraping directly into loading buffer and then separated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed with rabbit monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody (#ab52894, abcam) at 1:1000 dilution and with mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (Proteintech) to ensure equal loading. Densitometric analysis was then carried out to monitor the levels of EGFR degradation over time [

21].

2.8. Development of Oxaliplatin Resistant Human CRC Sublines

CRC sublines with resistance to Oxa were derived and established from SW480 and KM-12 wild type (WT) parent cell lines by continuous exposure to increasing concentrations of Oxa over a period of ten months. Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were used as initial starting doses for SW480 and KM-12 parent cell lines, 0.7 and 2.5 μM respectively. Oxa concentration was gradually increased up to 12.0 μM in the Oxa resistant SW480 cell line (SW480/OxaR)and up to 42.0 μM in the KM12- Oxa resistant cell line (KM-12/OxaR). For each parent cell line, two controls grown in drug-free media were harvested in parallel for further analyses at low (SW480/WT P10 and KM-12/WT P6) and high (SW480/WT P44 and KM-12/WT P37) passages.

2.9. Chemosensitivity Assay

Chemosensitivity was evaluated using the MTT assay as described previously [

22]. Briefly, 180μl of 1x10

4 cells/ml suspension was added to each test well of a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Drugs or control solutions were added to each well, and the plates cultured under standard conditions for 4 days after which cells were incubated with MTT solution (5mg/mL) in PBS for 4 hours. Formazan crystals were then solubilised in 150 µl of DMSO (Merck) and the plates scanned at 540 nm using an Ao Microplate Reader (Azure Biosystems, Cambridge Bioscience Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Chemosensitivity in terms of the IC

50 values was then determined from the data.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests for MTT assays and protein expression fold change were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA). Results are expressed as the means ± SEM of 3 independently repeated experiments. An unpaired T-test was used for statistical analyses, with significance scored at *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01 and ***p≤0.001 levels, and any p value >0.05 considered not significant (ns).

For monitoring of synergy in the combintion studies for Oxa and aloperinol, the survival data from the study was analysed using Synergy Finder software version 3.0, (synergyfinder.fimm.fi) with the expected drug combination responses calculated based on the ZIP reference model. Deviations between observed and expected responses with positive and negative values denote synergy and antagonism respectively [

23].

3. Results

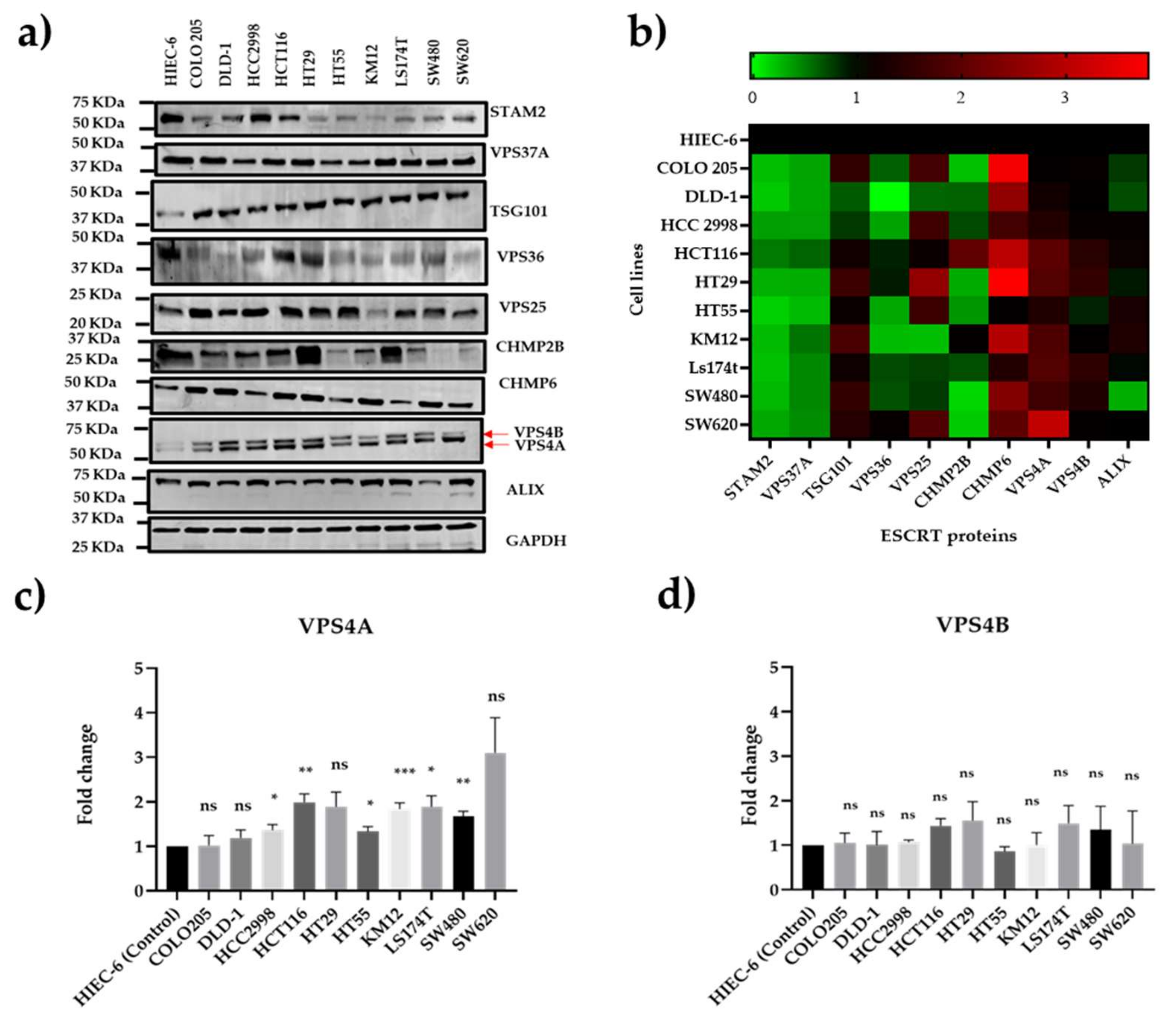

3.1. VPS4A Is Highly Expressed Across a Panel of CRC Cell Lines

ESCRT proteins representing the different ESCRT sub-types were evaluated in a panel of 10 CRC cell lines to characterize the baseline expression levels and select cell lines for manipulation of expression in further studies. Detection in the cancer cell lines was normalized to expression in a non-cancer intestinal epithelial cell line, HIEC-6. A range of expression was seen, with two ESCRT proteins relatively consistently overexpressed across the whole of the cell line panel: CHMP6 and VPS4A (

Figure 1). Given the more comprehensive literature links of VPS4A and cancer and findings in previous in-house proteomic studies, as discussed below, we then focused our initial studies presented in this paper on VPS4A.

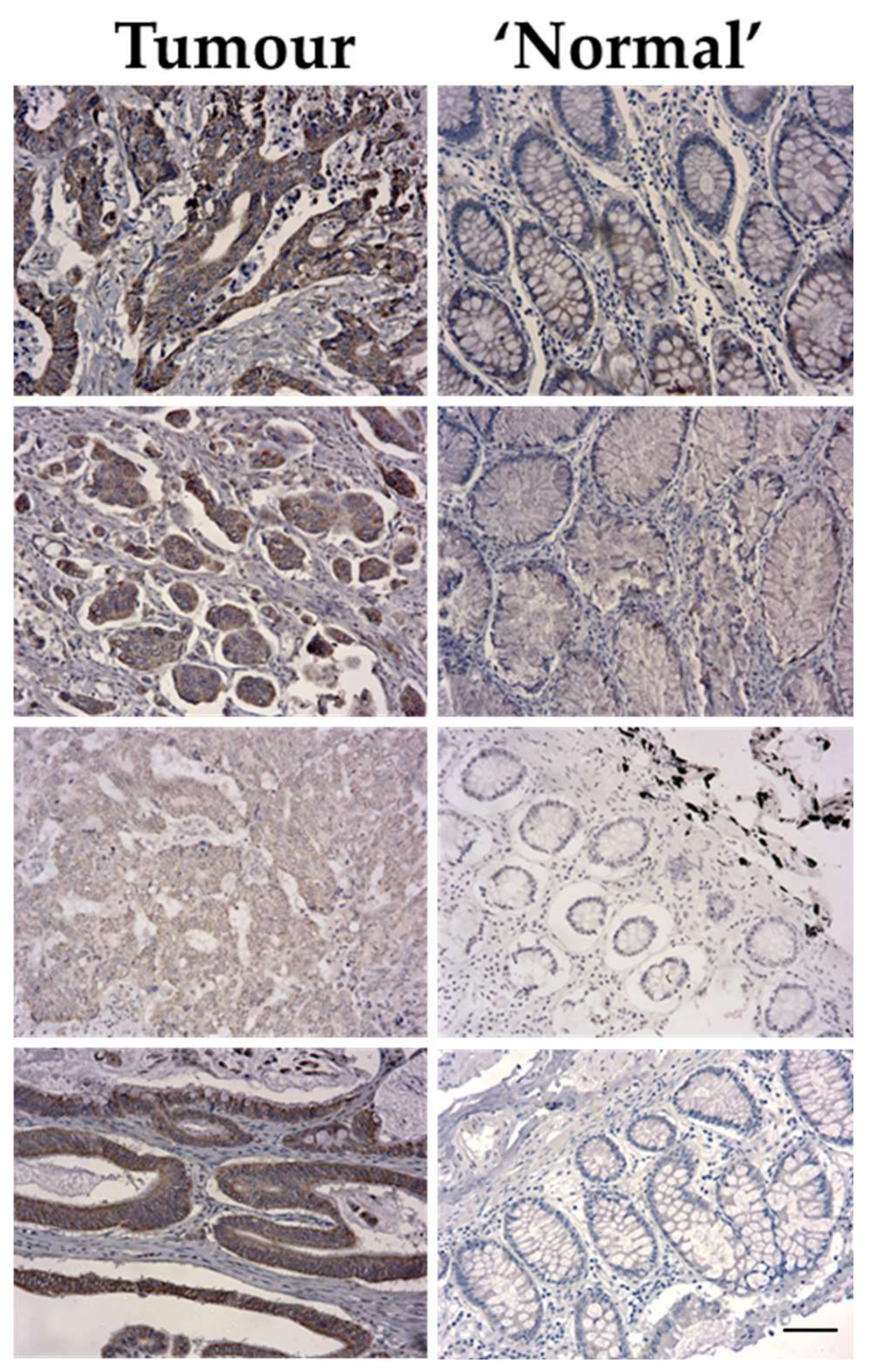

3.2. VPS4A Overexpressed in CRC Samples

It was observed that VPS4A was highly expressed in the tumour epithelium for all nine patients compared to the surrounding tissue, with immunolabelling seen in the cytoplasmic compartment. For patients where normal intestinal epithelium was also present in the samples, it was seen that there was a lower expression of VPS4A in this tissue compared to the areas of tumour (

Figure 2).

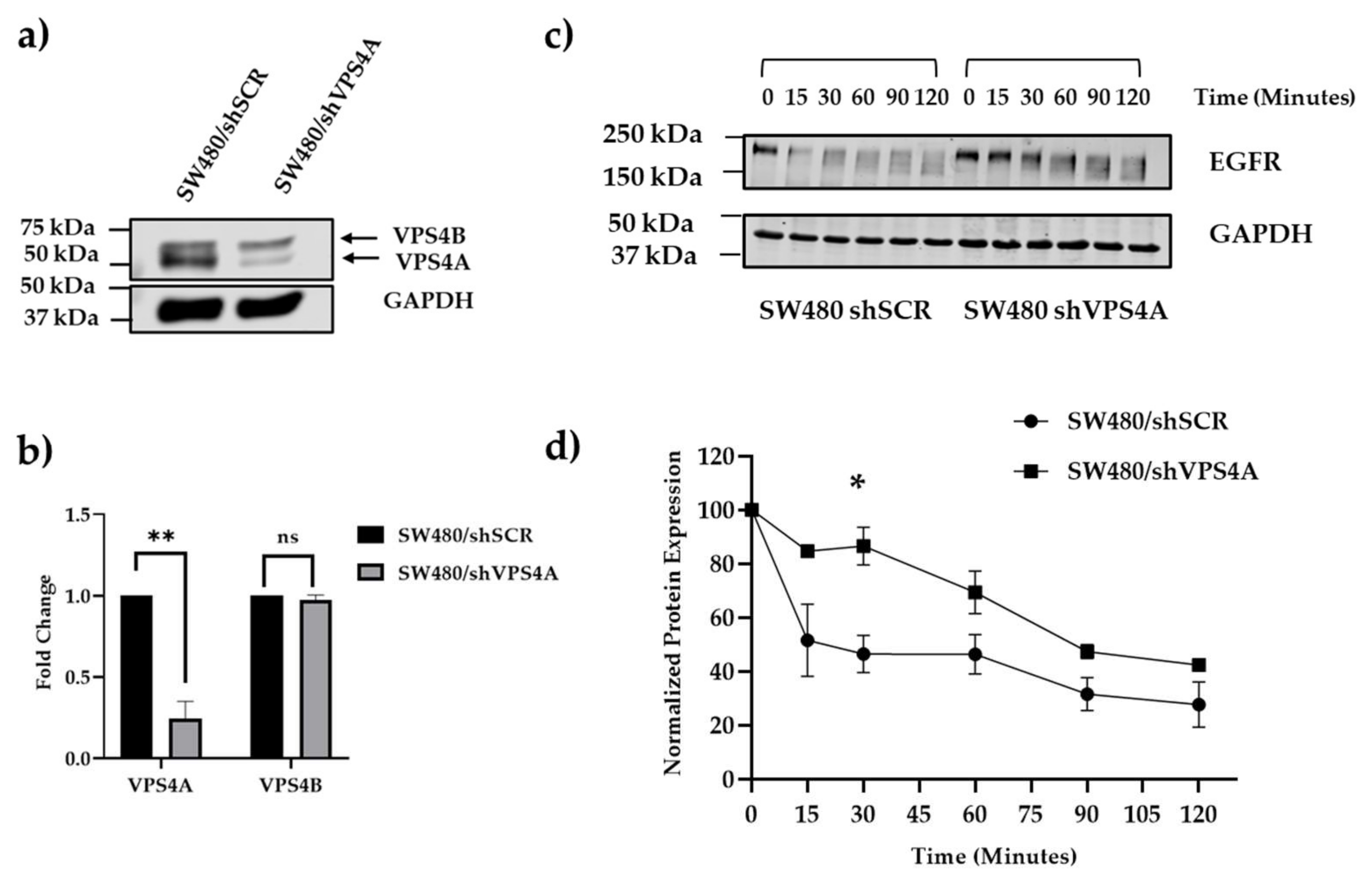

3.3. Knockdown of VPS4A Expression Leads to Loss of ESCRT Function

Following confirmation that VPS4A was relatively highly expressed in the wild-type CRC cell line panel, the SW480 cell line was selected for further studies due to the significant overexpression and suitability for transfection [

24]. Immunoblotting confirmed establishment of a subline clone with constitutively knocked down VPS4A expression (clone 4), whilst maintaining levels of the closely related VPS4B (

Figure 3).

Corroboration that this knockdown led to loss of ESCRT machinery function using the EGFR assay demonstrated the rate of degradation of EGFR was slowed in the SW480/shVPS4A knockdown clone 4 subline compared to the SW480/shSCR control subline (

Figure 3).

3.4. Reduction of VPS4A Expression Sensitizes Cells to Exposure to Oxaliplatin and Other Commonly Used Treatments for CRC

To determine if modulating expression of VPS4A by knocking down expression in CRC cell line could improve sensitivity to agents usually used in the treatment of CRC: Oxa, 5-FU & Iri, the SW480/shVPS4A knockdown subline was treated with each agent and response compared to treatment of the SW480/shSCR control subline, using an MTT cytotoxicity assay. As can be seen from

Table 2, reducing VPS4A expression significantly increased sensitivity to Oxa, with smaller changes also seen for the other 2 agents.

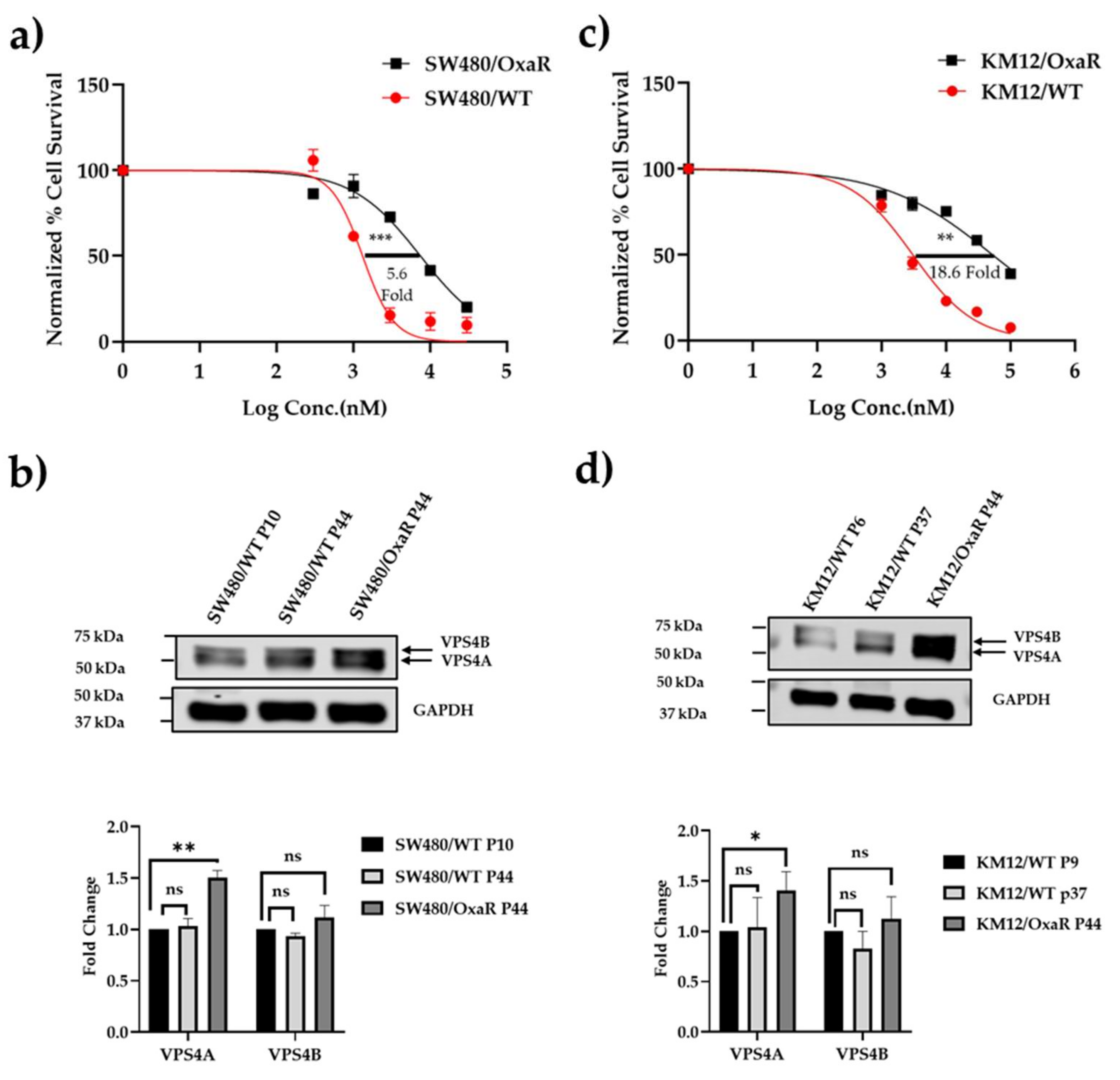

3.5. VPS4A Expression Is Altered in Oxa-Resistant Cell Lines

After it was seen that modulating VPS4A expression influenced Oxa sensitivity, correlation of VPS4A expression with sensitivity to Oxa was explored. To this end we developed two Oxa-resistant cell lines derived from SW480/WT and KM-12/WT CRC cell lines, with 5.6-fold and 18.6-fold resistance to Oxa respectively (

Figure 4a). We then evaluated VPS4A expression in the cell lines using immunoblotting and saw that it was significantly higher in the Oxa-resistant cell lines compared to the Oxa-sensitive WT lines (

Figure 4b) (p<0.001, and p<0.05 for SW480 and KM-12 respectively), thus confirming the potential modulatory role in Oxa resistance.

When VPS4A expression was subsequently knocked down in the SW480/OxaR subline, it was seen that sensitivity to Oxa returned, adding further support to VPS4A’s role in resistance modulation (

Table 3).

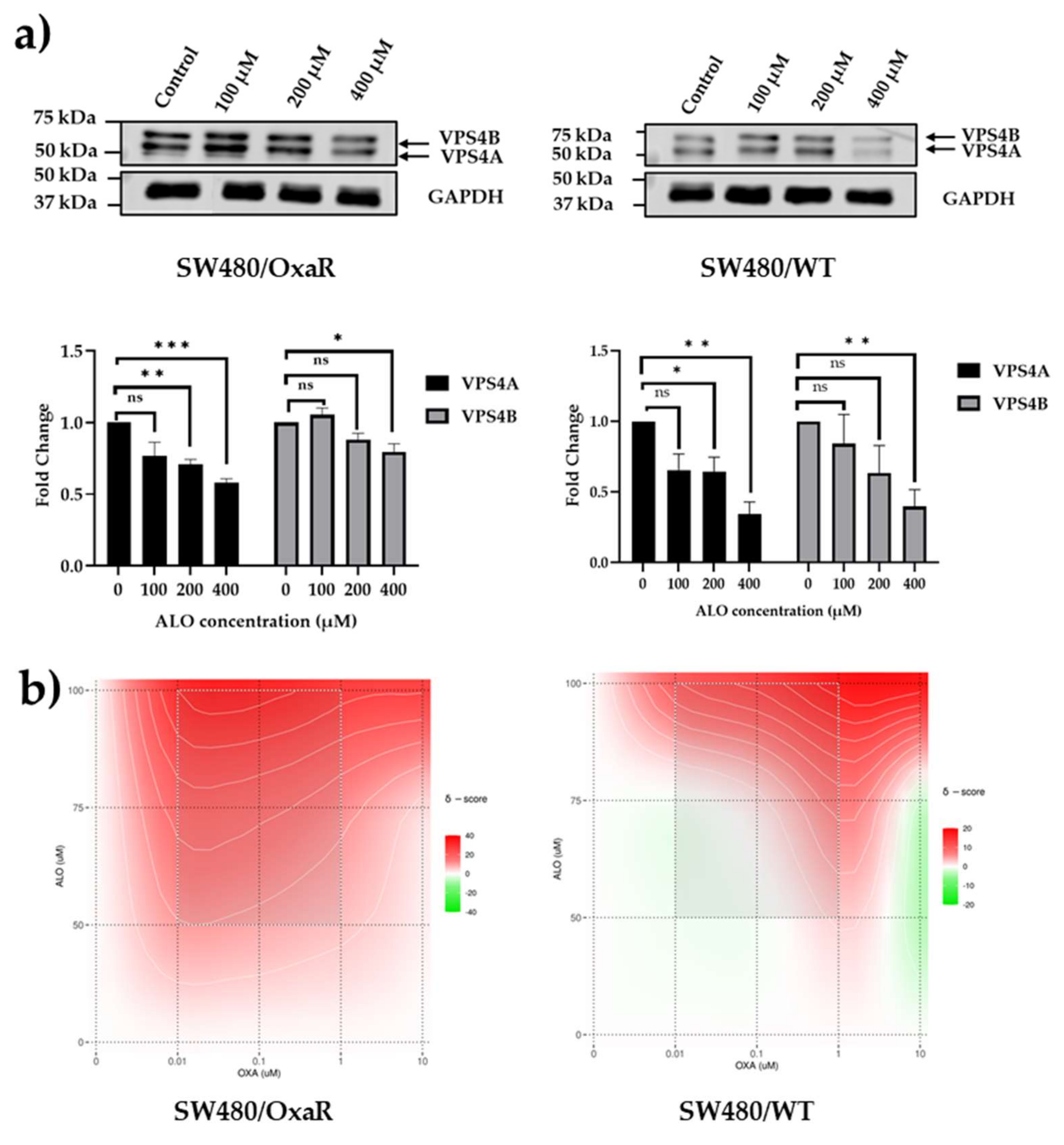

3.6. Aloperine, an Inhibitor of VPS4A, Modulates Resistance to Oxaliplatin in Both Wild-Type and Oxa-Resistant Cell Lines

To demonstrate the potential of using therapeutic control of VPS4A levels to modulate Oxa sensitivity in CRC cell lines, we utilized a molecule previously known to inhibit VPS4A expression, aloperine [

25]. We first confirmed using immunoblotting that it inhibited VPS4A. Some inhibition of VPS4B was also seen but to a lesser extent in SW480 cells (

Figure 5a).

The next step was to determine if reduction of VPS4A expression with Alo could modulate sensitivity to Oxa. We exposed SW480/WT and SW480/OxaR cell lines with combinations of Oxa and Alo for 96 hours and assessed cytotoxicity using the MTT assay described above. The data was then analysed using SyndergyFinder, and it was seen that a synergistic relation was seen in the OxaR cell line, suggesting that the Alo had potentiated the effect of Oxa to overcome resistance, whilst in the WT cell line an additive effect was seen (

Figure 5b, and

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Drug resistance is still a significant barrier to improving disease-free survival rates for CRC patients, and there is considerable work still being carried out to identify novel mechanisms of drug resistance to develop predictive biomarkers for optimizing treatment regimens and to develop modulators which could be administered to overcome treatment resistance. Approaches to modulate resistance include targeted protein degradation, combining antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugates with immune checkpoint inhibitors, and targeting the tumor microenvironment [

26].

In this study compelling evidence to support the ESCRT accessory protein VPS4A as a modulator of drug resistance in CRC is presented. Whilst there have been studies which suggest that ESCRT family proteins in general, and VPS4A in particular have a role in cancer processes and resistance [

10,

16,

27], this is the first study to our knowledge where a direct link between modulation of VPS4A expression and resistance to drugs in CRC cell lines has been demonstrated. The few only other published studies which talk of direct involvement of ESCRT family members in cancer resistance mechanisms involve CHMP2A which affects the sensitivity of cancer cells to natural killer-cell-mediated cytotoxicity in glioblastoma and head and neck squamous cells carcinoma which might participate in the development of drug resistance [

17].

This study initially looked to characterize ESCRT expression in a panel of ten CRC cell lines with a range of phenotypes to identify ESCRT family members which were either consistently overexpressed or under-expressed across the panel. The reasoning for this was to select a candidate which could be a factor in resistance across as many CRC subtypes as possible, not solely focusing on one phenotype, to give the best chance to be effective in either a diagnostic or therapeutic role going forward. Whilst a heterogeneity of expression for the different ESCRTs across the panel was to be expected from observations of ESCRT expression in CRC cell lines on the Protein Atlas Database (

www.proteinatlas.org), two candidates emerged from these initial studies, CHMP6 and VPS4A. The latter was selected for further analysis given that there is a more comprehensive literature covering links for VPS4A and cancer [

16,

27,

28], whilst in the case of CHMP6, only a few papers have demonstrated links to cancer [

29,

30]. In addition, previous in-house proteomic studies have demonstrated across the board upregulation of VPS4 protein in CRC drug resistant cell lines, with the 5-FU-focused data published previously [

22].

VPS4A elevated expression was not only demonstrated in a cell line panel, but also translated to clinical material, where raised VPS4A expression was observed in malignant transformed epithelium compared to adjacent normal intestinal epithelium in a small sample of CRC clinical material, thus showing the clinical relevance of this protein.

The key findings of the study came next, where it was demonstrated that by knocking down expression of VPS4A in a CRC cell line, its function could be modulated and ultimately sensitize the cells to CRC drug treatment, significantly in the case of Oxa, with some sensitization also evident to a lesser extent for Iri and 5-FU. This fits with similar findings where sensitivity to platinum drugs has been improved following modulation of other intracellular transport mechanisms. For example, enhancing sensitivity of CRC cells to Oxa through inhibition of transporter molecule MRP2 by Dihydromyricetin [

31] or siRNA knockdown of the ABCC2 gene encoding MRP2 [

32] enhanced CRC cells sensitivity to Oxa.

Further validation of our VPS4A hypothesis came in studies where it was seen that VPS4A expression was increased in Oxa-resistant sublines for a couple of CRC lines, and in further studies it was demonstrated that knocking down VPS4A expression in the SW480/OxaR cell line could reverse Oxa resistance.

We envisage that the evidence collected in this study will be utilized to develop a specific antagonist of VPS4A which can be administered from the start of chemotherapy with Oxa to prevent tumour cells becoming resistant to the drug and improving the chances of success with it. This approach has been previously taken with other potential resistance modulators from different mechanisms, for example in studies combining the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine [

33], the flavone glycoside scutellarin, [

34] or Kruppel-like factor 5 inhibitor, ML264 [

35], with Oxa in CRC cell lines or patient derived organoids.

With this in mind, a small molecule, Alo [

25], which was identified as a novel autophagy inhibitor that triggers tumor cell death by targeting VPS4A in both in vitro and in vivo non-small cell lung cancer models was utilised. We demonstrated synergism when administered along with Oxa in the SW480/OxaR cell line, suggesting the validity of this approach. However, given the high doses of Alo which were required to demonstrate VPS4 knockdown, and the questionable VPS4A specificity, with a clear knockdown of VPS4B seen as well, then a more specific and potent molecule would be required for an effective strategy. Therefore, the next step will be to carry out a drug discovery program based on this molecule to optimize its specificity and drug-like properties. A previous study by Huang et al., [

10] has identified druggable structures within the VPS4A molecule and targeting these will also be incorporated into the drug discovery program. We will also look to extend our investigation into assessing the other promising ESCRT family member in terms of expression, CHMP6.

5. Conclusions

In this study it has been demonstrated that the ESCRT family member VPS4A is a potential target for modulation of Oxa resistance in CRC, both through knockdown of VPS4A expression in CRC cell lines and by chemical inhibition. The next step will be to look to develop a pharmacologically active and effective inhibitor of VPS4A which can be utilized to improve the outcome of Oxa-based chemotherapy in CRC patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: complete immunoblot images; Figure S2: original images for

Figure 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and S.D.S.; methodology, N.M.A., S.K. and S.D.S.; validation, N.M.A., S.K. and S.D.S.; formal analysis, N.M.A., A.P., S.K. and S.D.S.; investigation, N.M.A. and A.P.; resources, A.C., S.K., and S.D.S; data curation, N.M.A. and S.D.S; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.A. and S.D.S; writing—review and editing, N.M.A., A.P., A.C., C.W.S., S.K. and S.D.S.; supervision, S.K. and S.D.S.; project administration, S.D.S.; funding acquisition, S.K. and S.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

N.M.A. is funded by a full scholarship (MM43/21) from the Ministry of Higher Education of the Arab Republic of Egypt.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Bradford’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (reference: application/21/107). Ethical approval was given by Leeds (East) Research Ethics Committee, UK, reference 22/YH/0111.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as archival material was sourced anonymously. Individual patients can’t be identified in the studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the present study are available on request from the corresponding author (S.D.S.).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Pathology Service at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Ethical Tissue at the University of Bradford for procurement of FFPE blocks, and Sarah Mcgowan and Suchit Chatterji for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dazio, G.; Epistolio, S.; Frattini, M.; Saletti, P. Recent and Future Strategies to Overcome Resistance to Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, J.; Manogaran, P. Mechanisms and Strategies to Overcome Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, X.; Chen, G.; Du, J. Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: From Mechanism to Clinic. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnesano, F.; Natile, G. Interference between copper transport systems and platinum drugs. Semin Cancer Biol 2021, 76, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Titiz, M.; Souza Monteiro de Araújo, D.; Geppetti, P.; Nassini, R.; De Logu, F. TRP Channels in Cancer: Signaling Mechanisms and Translational Approaches. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, H.R.; Bayraktar, E.; G, K.H.; Abd-Ellah, M.F.; Amero, P.; Chavez-Reyes, A.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C. Exosomes: From Garbage Bins to Promising Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Stefańska, K.; Józkowiak, M.; Angelova Volponi, A.; Shibli, J.A.; Golkar-Narenji, A.; Antosik, P.; Bukowska, D.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Mozdziak, P.; Dzięgiel, P.; et al. The Role of Exosomes in Human Carcinogenesis and Cancer Therapy-Recent Findings from Molecular and Clinical Research. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.H. ESCRTs are everywhere. Embo j 2015, 34, 2398–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuffers, S.; Brech, A.; Stenmark, H. ESCRT proteins in physiology and disease. Exp Cell Res 2009, 315, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.J.; Zhan, S.T.; Pan, Y.Q.; Bao, W.; Yang, Y. The role of Vps4 in cancer development. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1203359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.R.; Tan, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Yuan, J.S.; Song, W.Q. ESCRT may function as a tumor biomarker, transitioning from pan-cancer analysis to validation within breast cancer. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1531940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manteghi, S.; Gingras, M.C.; Kharitidi, D.; Galarneau, L.; Marques, M.; Yan, M.; Cencic, R.; Robert, F.; Paquet, M.; Witcher, M.; et al. Haploinsufficiency of the ESCRT Component HD-PTP Predisposes to Cancer. Cell Rep 2016, 15, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, J.B.A.; Wenzel, D.M.; Strohacker, L.K.; Guindo-Martínez, M.; Alam, S.L.; Mercader, J.M.; Torrents, D.; Ullman, K.S.; Sundquist, W.I.; Martin-Serrano, J. A cancer-associated polymorphism in ESCRT-III disrupts the abscission checkpoint and promotes genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E8900–E8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behan, F.M.; Iorio, F.; Picco, G.; Gonçalves, E.; Beaver, C.M.; Migliardi, G.; Santos, R.; Rao, Y.; Sassi, F.; Pinnelli, M.; et al. Prioritization of cancer therapeutic targets using CRISPR-Cas9 screens. Nature 2019, 568, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.R.; de Weck, A.; Schlabach, M.R.; Billy, E.; Mavrakis, K.J.; Hoffman, G.R.; Belur, D.; Castelletti, D.; Frias, E.; Gampa, K.; et al. Project DRIVE: A Compendium of Cancer Dependencies and Synthetic Lethal Relationships Uncovered by Large-Scale, Deep RNAi Screening. Cell 2017, 170, 577–592e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E.; Nowak, P.; Kolmus, K.; Cybulska, M.; Goryca, K.; Derezińska-Wołek, E.; Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A.; Brewińska-Olchowik, M.; Grochowska, A.; Piwocka, K.; et al. Synthetic lethality between VPS4A and VPS4B triggers an inflammatory response in colorectal cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2020, 12, e10812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernareggi, D.; Xie, Q.; Prager, B.C.; Yun, J.; Cruz, L.S.; Pham, T.V.; Kim, W.; Lee, X.; Coffey, M.; Zalfa, C.; et al. CHMP2A regulates tumor sensitivity to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Chen, L.; Tang, Z.; Wills, C.A.; Liang, X.; Wang, H.G. Targeting the ESCRT-III component CHMP2A for noncanonical Caspase-8 activation on autophagosomal membranes. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delrue, I.; Pan, Q.; Baczmanska, A.K.; Callens, B.W.; Verdoodt, L.L.M. Determination of the Selection Capacity of Antibiotics for Gene Selection. Biotechnol J 2018, 13, e1700747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, T.P.; Pilbrough, W.; Hughes, B.S.; Gray, P.P. 1.11 - Cell Line Isolation and Design. In Comprehensive Biotechnology (Third Edition); Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, 2011; pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kantamneni, S.; Holman, D.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Nishimune, A.; Henley, J.M. GISP increases neurotransmitter receptor stability by down-regulating ESCRT-mediated lysosomal degradation. Neurosci Lett 2009, 452, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Duran, M.; Shaheed, S.U.; Sutton, C.W.; Shnyder, S.D. A Proteomic Investigation to Discover Candidate Proteins Involved in Novel Mechanisms of 5-Fluorouracil Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianevski, A.; Giri, A.K.; Aittokallio, T. SynergyFinder 3.0: an interactive analysis and consensus interpretation of multi-drug synergies across multiple samples. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, W739–W743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, M.; Pospiech, K.; Lewandowska, U.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A.W.; Bednarek, A.K. Diverse effect of WWOX overexpression in HT29 and SW480 colon cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol 2014, 35, 9291–9301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Dong, Y.; Kang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Ouyang, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; et al. Aloperine Suppresses Cancer Progression by Interacting with VPS4A to Inhibit Autophagosome-lysosome Fusion in NSCLC. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2308307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.R.; Lu, M.Y.; Wei, T.H.; Fleishman, J.S.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.L.; Kong, X.T.; Sun, S.L.; Li, N.G.; Yang, Y.; et al. Overcoming cancer therapy resistance: From drug innovation to therapeutics. Drug Resist Updat 2025, 81, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neggers, J.E.; Paolella, B.R.; Asfaw, A.; Rothberg, M.V.; Skipper, T.A.; Yang, A.; Kalekar, R.L.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; Dharia, N.V.; Kugener, G.; et al. Synthetic Lethal Interaction between the ESCRT Paralog Enzymes VPS4A and VPS4B in Cancers Harboring Loss of Chromosome 18q or 16q. Cell Rep 2020, 33, 108493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundora, K.A.; Zhuang, Y.; Hamamoto, K.; Wang, G.; Chen, L.; Hattori, T.; Liang, X.; Bao, L.; Vangala, V.; Tian, F.; et al. DBeQ derivative targets vacuolar protein sorting 4 functions in cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2025, 392, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, E.; Meng, L.; Kang, R.; Wang, X.; Tang, D. ESCRT-III-dependent membrane repair blocks ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020, 522, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Cai, L. ELK4 targets CHMP6 to inhibit ferroptosis and enhance malignant properties of skin cutaneous melanoma cells. Arch Dermatol Res 2024, 316, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Sui, H.; Ji, Q.; E, Q.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Dihydromyricetin reverses MRP2-mediated MDR and enhances anticancer activity induced by oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs 2017, 28, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Bugde, P.; He, J.; Merien, F.; Lu, J.; Liu, D.X.; Myint, K.; Liu, J.; McKeage, M.; Li, Y. Transport-Mediated Oxaliplatin Resistance Associated with Endogenous Overexpression of MRP2 in Caco-2 and PANC-1 Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, M.; Tanaka, S.; Ueda, K.; Iwakawa, S.; Ogawara, K.I. Decitabine exerted synergistic effects with oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells with intrinsic resistance to decitabine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 509, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Ge, Y.; Cui, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, B. Scutellarin resensitizes oxaliplatin-resistant colorectal cancer cells to oxaliplatin treatment through inhibition of PKM2. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2021, 21, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Gao, H.; Feng, W.; Li, W.; Miao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zong, Y.; Zhao, J.; et al. KLF5 inhibition overcomes oxaliplatin resistance in patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids by restoring apoptotic response. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Characterisation of ESCRT protein expression in a panel of human CRC cell lines using immunoblotting. a) Immunoblot and b) Heat map showing the relative expression of the ESCRT proteins compared to expression in a non-cancer intestinal epithelial cell line, HIEC-6, for three separate immunoblot runs. Of interest is that VPS4A is one of only two ESCRT proteins which are consistently overexpressed in the panel, the other being CHMP-6. c) and d) densitometric analysis for VPS4A and VPS4B showing that whilst significant high expression is seen for a range of the cell lines for VPS4A, none of the cell panel show significant high expression for VPS4B. Statistical differences compared to HIEC-6 are highlighted by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and *** (p<0.001) using a Student’s t-test.

Figure 1.

Characterisation of ESCRT protein expression in a panel of human CRC cell lines using immunoblotting. a) Immunoblot and b) Heat map showing the relative expression of the ESCRT proteins compared to expression in a non-cancer intestinal epithelial cell line, HIEC-6, for three separate immunoblot runs. Of interest is that VPS4A is one of only two ESCRT proteins which are consistently overexpressed in the panel, the other being CHMP-6. c) and d) densitometric analysis for VPS4A and VPS4B showing that whilst significant high expression is seen for a range of the cell lines for VPS4A, none of the cell panel show significant high expression for VPS4B. Statistical differences compared to HIEC-6 are highlighted by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and *** (p<0.001) using a Student’s t-test.

Figure 2.

Representative images of VPS4A immunolabelling for 4 different patients showing higher expression in the cytoplasmic fraction of the tumour epithelium compared to the normal epithelium. Bar length = 60µm.

Figure 2.

Representative images of VPS4A immunolabelling for 4 different patients showing higher expression in the cytoplasmic fraction of the tumour epithelium compared to the normal epithelium. Bar length = 60µm.

Figure 3.

a) and b) A subline of SW480 with constitutively lower expression of VPS4A was established as confirmed using immunoblotting (n=3), statistical differences compared to the scrambled subline are highlighted by * (p<0.05) and ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test. Expression of VPS4B in contrast was not significantly altered. c) and d) loss of ESCRT machinery function as a consequence of this knockdown was confirmed using the EGFR assay, with analysis using immunoblotting (n=3), where there was a significant (* p<0.05 using a Student’s t-test) slowing in the rate of EGFR degradation compared to the scrambled subline where the ESCRT machinery was intact. EGFR protein expression in d) is normalized to the control at t=0.

Figure 3.

a) and b) A subline of SW480 with constitutively lower expression of VPS4A was established as confirmed using immunoblotting (n=3), statistical differences compared to the scrambled subline are highlighted by * (p<0.05) and ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test. Expression of VPS4B in contrast was not significantly altered. c) and d) loss of ESCRT machinery function as a consequence of this knockdown was confirmed using the EGFR assay, with analysis using immunoblotting (n=3), where there was a significant (* p<0.05 using a Student’s t-test) slowing in the rate of EGFR degradation compared to the scrambled subline where the ESCRT machinery was intact. EGFR protein expression in d) is normalized to the control at t=0.

Figure 4.

a) and b) Generation of Oxa resistant cell lines demonstrating significant resistance to the drug compared to the wild-type cell line in an MTT chemosensitivity assay. Cell survival profiles of parent cell lines and their respective resistant sublines to Oxa for a) SW480 and b) KM-12 CRC cell lines under exposure to 0.3-100µM doses of Oxa for 96h. MTT assays were performed in three independent experiments. A 5.6-fold and 18.6-fold difference in IC50 were found in the SW480/OxaR and KM-12/OxaR sublines respectively, (*** p≤0.001) and (** p≤0.01. c) and d) demonstrate a significantly raised expression of VPS4A in the resistant cell lines respective to their parent wild type cell lines using immunoblotting (n=3). Expression of VPS4B in contrast was not significantly altered. Statistical differences compared to the wild type are highlighted by * (p<0.05) and ** (p<0.01) using an Unpaired Students t-test.

Figure 4.

a) and b) Generation of Oxa resistant cell lines demonstrating significant resistance to the drug compared to the wild-type cell line in an MTT chemosensitivity assay. Cell survival profiles of parent cell lines and their respective resistant sublines to Oxa for a) SW480 and b) KM-12 CRC cell lines under exposure to 0.3-100µM doses of Oxa for 96h. MTT assays were performed in three independent experiments. A 5.6-fold and 18.6-fold difference in IC50 were found in the SW480/OxaR and KM-12/OxaR sublines respectively, (*** p≤0.001) and (** p≤0.01. c) and d) demonstrate a significantly raised expression of VPS4A in the resistant cell lines respective to their parent wild type cell lines using immunoblotting (n=3). Expression of VPS4B in contrast was not significantly altered. Statistical differences compared to the wild type are highlighted by * (p<0.05) and ** (p<0.01) using an Unpaired Students t-test.

Figure 5.

a) Aloperine inhibits expression of VPS4 proteins. SW480 cells were treated with Alo for 96 hours and then harvested and analysed using immunoblotting. b) representative contour plots following administration of combinations of Oxa and Alo to SW480/WT and SW480/OxaR cell lines for 96 hours in the MTT assay, showing more synergistic interactions between concentrations of each compound for the SW480/OxaR cell line compared to the SW480/WT cell line, as denoted by the higher area of the plot shaded in red. Statistical differences compared to untreated controls are highlighted by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and *** (p<0.001) using a Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

a) Aloperine inhibits expression of VPS4 proteins. SW480 cells were treated with Alo for 96 hours and then harvested and analysed using immunoblotting. b) representative contour plots following administration of combinations of Oxa and Alo to SW480/WT and SW480/OxaR cell lines for 96 hours in the MTT assay, showing more synergistic interactions between concentrations of each compound for the SW480/OxaR cell line compared to the SW480/WT cell line, as denoted by the higher area of the plot shaded in red. Statistical differences compared to untreated controls are highlighted by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and *** (p<0.001) using a Student’s t-test.

Table 1.

Details for the colorectal cancer patients included in the study.

Table 1.

Details for the colorectal cancer patients included in the study.

| Patient ID Code |

Sex |

Stage T |

Stage N |

Stage M |

| 9 |

M |

4 |

1 |

1 |

| 22 |

M |

3 |

0 |

1 |

| 24 |

F |

4 |

2 |

1 |

| 31 |

M |

3 |

2 |

1 |

| 33 |

M |

3 |

1 |

1 |

| 37 |

F |

3 |

2 |

1 |

| 56 |

M |

3 |

1 |

1 |

| 57 |

F |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| 58 |

F |

3 |

0 |

1 |

Table 2.

Knocking down VPS4A expression increases sensitivity to Oxa, and to a lesser extent other agents commonly used in treatment of CRC in an MTT cytotoxicity assay (n=3). Statistical differences between the knockdown and scrambled cell lines are highlighted by ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test.

Table 2.

Knocking down VPS4A expression increases sensitivity to Oxa, and to a lesser extent other agents commonly used in treatment of CRC in an MTT cytotoxicity assay (n=3). Statistical differences between the knockdown and scrambled cell lines are highlighted by ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test.

| Drug |

IC50 (µM) for SW480/shVPS4A |

IC50 (µM) for SW480shSCR |

Fold-difference |

P value |

| Oxaliplatin |

0.47±0.05 |

1.6±0.17 |

3.4 |

** |

| 5-Fluorouracil |

1.73±0.07 |

2.37±0.3 |

1.37 |

ns |

| Irinotecan |

4.23±0.93 |

6.56±1.35 |

1.55 |

ns |

Table 3.

Knocking down VPS4A expression in the SW480/OxaR subline reverses the Oxa resistance phenotype as measured in an MTT cytotoxicity assay (n=3). Statistical differences between the knockdown and scrambled cell lines are highlighted by ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test.

Table 3.

Knocking down VPS4A expression in the SW480/OxaR subline reverses the Oxa resistance phenotype as measured in an MTT cytotoxicity assay (n=3). Statistical differences between the knockdown and scrambled cell lines are highlighted by ** (p<0.01) using a Student’s t-test.

| Drug |

IC50 (µM) for SW480/OxaR shVPS4A |

IC50 (µM) for SW480/OxaR SCR |

Fold-difference |

P value |

| Oxaliplatin |

1.30±0.06 |

9.00±2.65 |

6.92 |

** |

Table 4.

Mean synergy scores for 3 independent runs for both cell lines, showing that the interaction between Alo and Oxa is more likely to be synergistic in the OxaR cell line, whilst the interactions are additive in the WT cell line.

Table 4.

Mean synergy scores for 3 independent runs for both cell lines, showing that the interaction between Alo and Oxa is more likely to be synergistic in the OxaR cell line, whilst the interactions are additive in the WT cell line.

| |

SW480/OxaR |

SW480/WT |

| Synergy Score |

15.61±1.16 |

3.00±0.99 |

| Interpretation |

Likely to be synergistic |

Likely to be additive |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).