1. Introduction

The cephalisation of the vertebrate head—its

transformation from a simple anterior region to a complex, sensorily and

neurally integrated structure—constitutes one of the most profound transitions

in animal evolution. Central to this narrative is the reorganisation of craniofacial

openings, notably the transition from a single median nostril (monorhiny) in

primitive jawless fishes to paired lateral nostrils (paired external nares) in

jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes). This morphological shift is more than

superficial: it is inextricably linked to the spatial reallocation of cranial

real estate, the rise of bilateral olfactory circuits, and the dramatic

expansion of the vertebrate forebrain (Northcutt, 2008; Janvier, 2007).

In the earliest vertebrates, exemplified today by

lampreys and hagfish, the median nostril is centrally located above the oral

cavity, with a single olfactory sac and bulb feeding into a relatively simple,

narrow forebrain (Fritzsch & Northcutt, 1993). This arrangement restricts

the migration of cranial neural crest cells and limits the developmental width

and complexity of the anterior cranial vault. Fossil evidence, particularly

from Silurian and Devonian strata, captures the gradual lateralisation of olfactory

structures, with transitional taxa such as galeaspids, osteostracans, and

placoderms exhibiting intermediate morphologies (Gai et al., 2011; Janvier,

2007). Concomitantly, there is a marked increase in forebrain size and folding,

indicative of functional and developmental liberation (Northcutt, 2008).

The adaptive rationale for this evolutionary change

is compelling. Paired nostrils, and by extension paired olfactory bulbs, enable

stereo-olfaction—essential for gradient navigation and spatial localisation of

chemical cues. Such capabilities underpin foraging, mate-finding, and predator

avoidance in both aquatic and terrestrial vertebrates. More subtly, the

displacement of nasal openings to the sides of the face liberates the midline

for mesenchymal proliferation and neural expansion, a prerequisite for the

evolution of advanced forebrain functions (Brugmann et al., 2007). This spatial

reallocation is paralleled by similar trends in other cranial systems (eyes,

ears, jaws), reflecting the broader logic of bilateral patterning and

cephalisation.

The developmental programme governing nostril

morphogenesis is orchestrated by a complex network of highly conserved

signalling pathways. The Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) cascade plays a particularly

crucial role, serving as a key morphogen in craniofacial development and neural

patterning (Dworkin et al., 2016). SHH signalling is essential for the

regulation of cranial neural crest cell migration and survival, which in turn

determines the proper formation of craniofacial structures, including the nasal

region (Balmer & LaMantia, 2004). The expression patterns of SHH create

signalling gradients that establish the midline of the developing embryo and

influence the lateralisation of structures such as the nostrils. In the absence

of SHH, severe midline defects occur, including cyclopia and holoprosencephaly,

characterised by a failure of nostril separation and fusion of forebrain

structures (LaMantia, 2020).

The molecular interplay between SHH and other

signalling molecules, particularly Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 (FGF8), is

essential for proper craniofacial development. FGF8 patterns the anterior

neural ridge and induces olfactory placodes, whilst Bone Morphogenetic Protein

4 (BMP4) and WNT gradients further refine axial patterning. The DLX and PAX6

homeobox gene families orchestrate craniofacial regionalisation and sensory

organogenesis (Cerny et al., 2010; Whitlock & Westerfield, 2000). The

particular importance of PAX6 in olfactory development is evidenced by the

complete absence of olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulbs in PAX6-deficient

embryos, where neural crest fails to migrate properly into the frontonasal

region (Anchan et al., 1997). Experimental perturbations of these pathways in

model organisms recapitulate ancestral morphologies, underscoring their

evolutionary antiquity and conservation across vertebrate lineages.

The integrated developmental system linking SHH

signalling, neural crest migration, and nostril configuration has profound

implications for vertebrate brain evolution. The presence of paired lateral

nostrils directly influences the spatial organisation of olfactory bulbs and

their connections to the telencephalon. Moreover, the liberation of the cranial

midline allows for the expansion of forebrain structures, contributing to the

evolutionary increase in brain complexity observed across the vertebrate lineage.

The shift from a single median nostril to paired lateral nostrils therefore

represents not merely a change in external morphology but a fundamental

reorganisation of the vertebrate brain architecture.

In recent years, advances in fossil imaging

techniques such as synchrotron radiation X-ray microtomography have revealed

unprecedented details of cranial anatomy in early vertebrates, allowing for

more refined reconstructions of the transition from monorhiny to paired

nostrils. Studies of exceptionally preserved fossils from the Chengjiang biota

in China and the Gogo Formation in Australia have provided crucial insights

into the cranial anatomy of early vertebrates and the evolutionary sequence of

nostril reconfiguration (Long et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2013). These findings

have been complemented by developmental studies in extant taxa, offering a more

comprehensive picture of this critical evolutionary transition.

The evolutionary shifts in nostril morphology also

correlate with changes in olfactory sensitivity and processing capacity.

Comparative neuroanatomical studies suggest that the transition to paired

nostrils facilitated the expansion of olfactory epithelia and increased the

surface area available for odorant detection (Kajiura et al., 2005). This

enhanced olfactory capability likely conferred significant ecological

advantages, particularly for navigation, foraging, and reproductive behaviours.

The adaptive significance of paired nostrils is evidenced by their convergent

evolution in multiple lineages, indicating strong selection pressure for this

configuration (Jacobs, 2012).

The ecological context of nostril evolution must be

considered within the broader framework of vertebrate adaptation to aquatic

environments (Montgomery, 2025). The transition from filter-feeding to active

predation in early vertebrates required enhanced sensory capabilities,

including more sophisticated olfactory systems. The lateralisation of nostrils

facilitated both improved directional sensing of chemical gradients and the

evolution of continuous water flow systems that enhanced olfactory efficiency

in aquatic environments (Cox, 2008). This innovation likely contributed to the

ecological success and subsequent diversification of jawed vertebrates.

From a biomechanical perspective, the transition

from a median to paired lateral nostrils also entailed changes in hydrodynamics

and respiratory efficiency. In many aquatic vertebrates, the positioning of

nostrils influences water flow patterns across sensory epithelia and can affect

both respiratory and olfactory functions (Zeiske et al., 2009). The separation

of olfactory and respiratory functions in later vertebrate evolution further

refined these systems, culminating in the complex nasal anatomies observed in

tetrapods.

Despite the centrality of nostril subdivision in

vertebrate evolution, quantitative analyses of its spatial consequences are

rare. Traditional palaeoneurological studies have documented the association

between paired nostrils and forebrain expansion but have seldom formalised the

geometric or mathematical underpinnings of this relationship. Here, we address

this gap by constructing and parameterising a simple but rigorous morphometric

model, representing the cranial vault as a bounded region defined by the position

and size of nasal openings. By systematically varying nostril configuration, we

simulate its impact on the "real estate" available for forebrain

proliferation(Montgomery, 2024). Such modelling, when anchored in fossil

morphometrics and developmental genetics, allows us to formally test and

visualise the evolutionary hypothesis that nostril bifurcation is a spatial

precondition for increased neural complexity.

This article thus proceeds by (1) reviewing the

palaeontological and developmental evidence for nostril subdivision and its

neuroanatomical consequences, (2) presenting a formal spatial model of cranial

allocation, (3) simulating the effects of nostril configuration on available

neural space, and (4) critically discussing the evolutionary, developmental,

and methodological implications. Our approach exemplifies the power of

integrating mathematical formalism, empirical morphology, and genetics in

evolutionary developmental biology.

2. Methodology

2.1. Morphometric Model Construction

We formalise the anterior cranial vault as a

bounded spatial domain in the xy-plane, representing a horizontal cross-section

at the level of the nasal region. The width of the cranial base is denoted by

W, and the anteroposterior length by L. For analytical tractability, we model

the nostril(s) as circular orifices of radius r.

In the monorhiny (single median nostril) condition,

the nostril is positioned centrally at x = 0. In the dirhiny (paired lateral

nostrils) condition, nostrils are positioned at x = ±d from the midline, where

d is the lateral displacement parameter. The mathematical formulations for

central cranial area available for neural development are as follows:For the

single median nostril configuration:

For the single median nostril configuration:

Where represents the area occupied by the median

nostril.

For paired lateral nostrils:

This formulation assumes that regions lateral to

the paired nostrils are not available for central neural structures,

reflecting the biomechanical and developmental constraints that restrict

forebrain expansion to the central region between the nostrils.

2.2. Three-Dimensional Cranial Volume Modelling

To extend our analysis to three dimensions, we

integrate the available cranial area over vertical height to estimate potential

forebrain volume:

Where h represents the dorsal-ventral cranial

height. This simplification assumes uniform vertical expansion, which serves as

a first-order approximation of volumetric constraints.

Additionally, we develop a more sophisticated model

that accounts for the impact of neural crest cell migration pathways, which are

critical developmental determinants of craniofacial morphology. The neural

crest pathway is formulated as:

Where is the radial function describing the migration

path from the neural fold origin to peripheral targets in the facial primordia.

2.3. Model Parameterisation

To ground our theoretical model in empirical

reality, we calibrate parameters using morphometric data from fossil and

comparative anatomical studies (Gai et al., 2011; Northcutt, 2008). After

thorough literature review, we selected the following representative values:

(cranial width)

(anteroposterior length)

(nostril radius)

(lateral nostril displacement)

(cranial height)

These values correspond to average dimensions

observed in small to medium-sized early vertebrate fossils and provide a

reasonable baseline for comparative analysis. We acknowledge that substantial

variation exists across taxa and developmental stages; therefore, sensitivity

analyses will be performed to assess the robustness of our findings to

parameter variations.

2.4. Python Simulation and Visualisation Methods

We implemented our morphometric model using Python

3.8, with the NumPy package for numerical calculations and Matplotlib for

visualization. The simulation code computes available central area and

forebrain volume for each nostril configuration and generates appropriate

visualisations for comparative analysis.

For two-dimensional visualisations, we created

schematic representations of both nostril configurations, highlighting the

differential impact on central cranial space. For three-dimensional analysis,

we implemented a volumetric model to visualise the spatial constraints imposed

by different nostril arrangements on potential forebrain development (Please

see attachments Section for the code).

3. Results

3.1. Two-Dimensional Spatial Analysis of Nostril Configuration

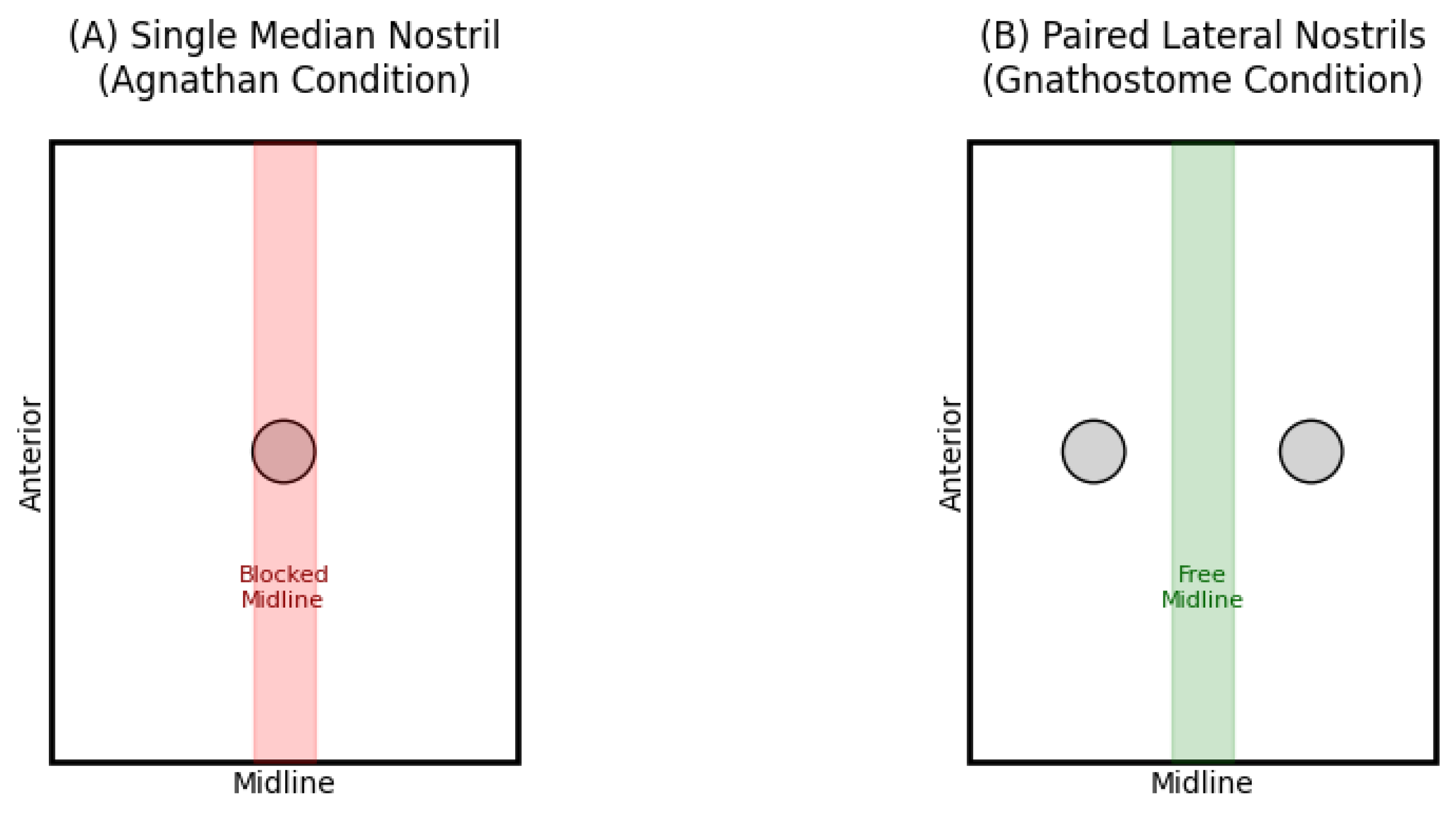

Our model reveals significant differences in

central cranial area availability between the single median nostril and paired

lateral nostril configurations, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The schematic representation clearly

demonstrates how the positioning of nostrils impacts the contiguous space

available at the cranial midline.

3.2. Quantitative Assessment of Cranial Space Allocation

Applying the parameter values to our equations

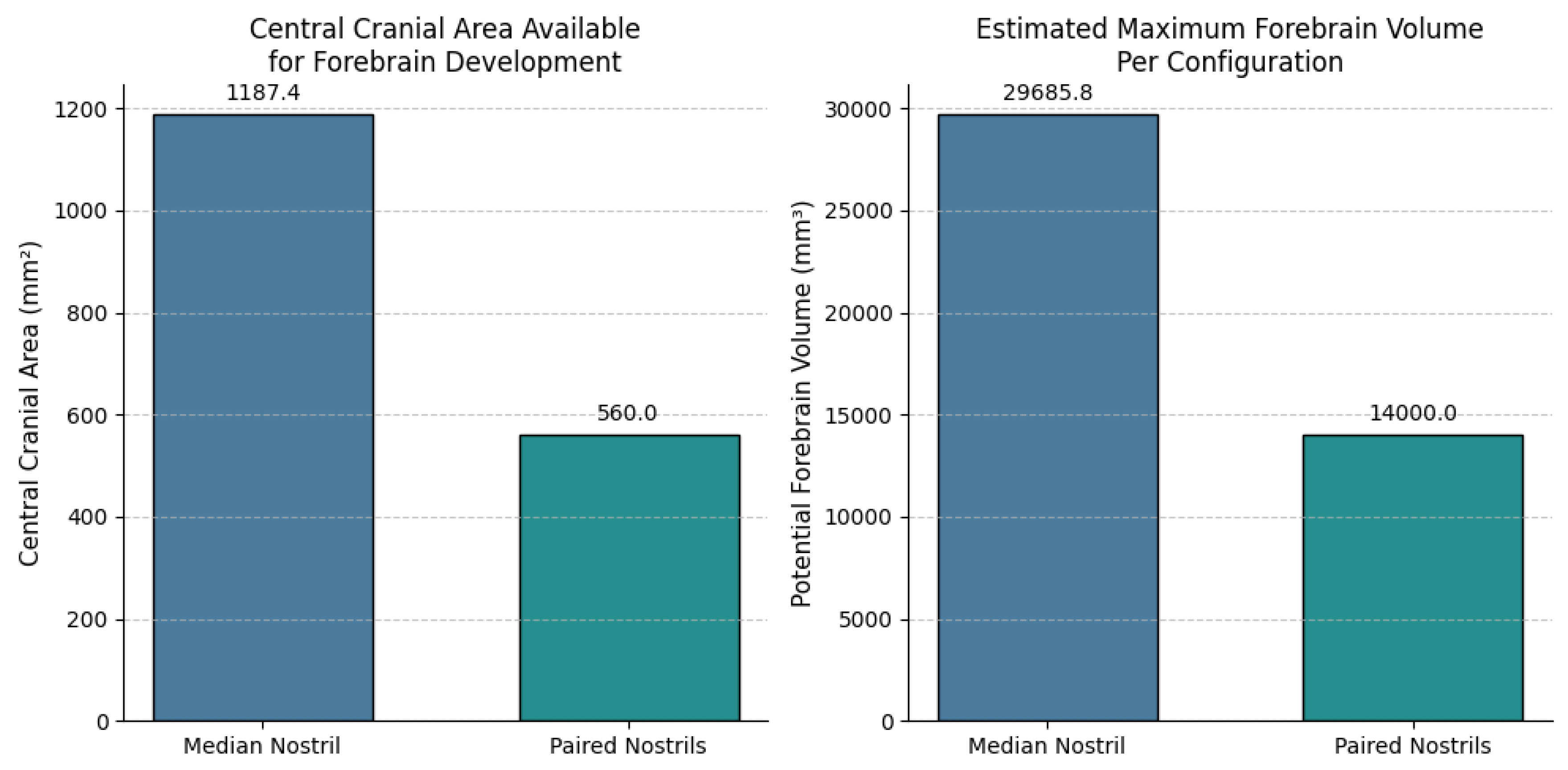

yields the following quantitative results:

For the single median nostril

configuration: For paired lateral nostrils:

These calculations reveal that while the single

median nostril configuration offers a greater total available central area,

this area includes the midline region directly anterior to the developing

forebrain. The paired nostril configuration, despite having a smaller central

area, provides a contiguous central domain uninterrupted by nasal structures,

which is crucial for integrated forebrain development.

The quantitative comparison of central cranial area

and potential forebrain volume between the two nostril configurations is

visualised in

Figure 2.

3.3. Three-Dimensional Analysis of Nostril Impact on Forebrain Space.

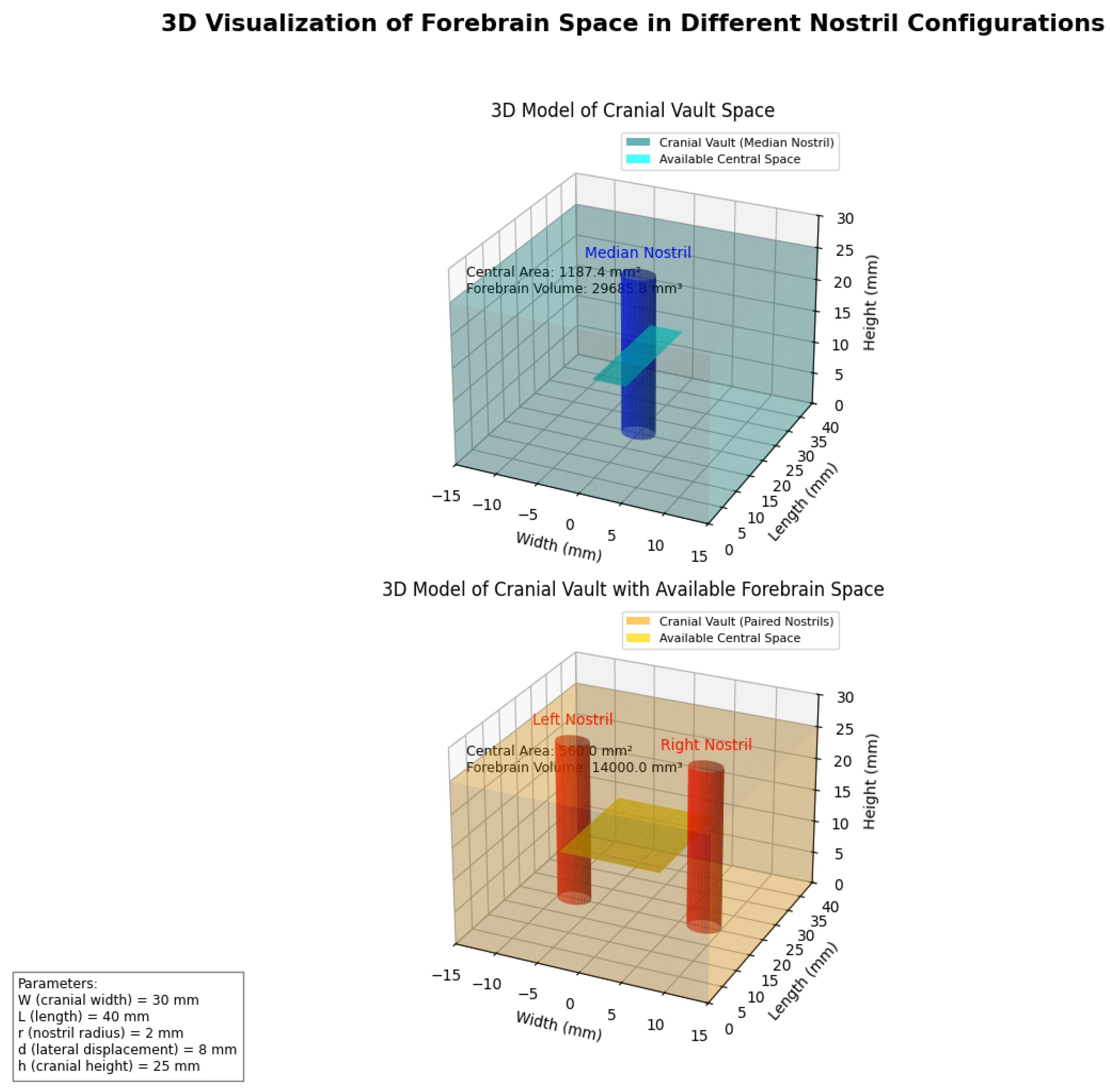

To further elucidate the spatial implications of

nostril configuration, we developed a three-dimensional visualisation of the

cranial space available for forebrain development under each configuration (

Figure 3).

This three-dimensional analysis reveals that beyond

simple area calculations, the spatial distribution of available cranial volume

differs significantly between the two configurations. The single median nostril

creates a central obstruction that necessitates bifurcation of neural

structures, while paired lateral nostrils allow for a contiguous central domain

that can support integrated forebrain development.

3.4. Developmental and Evolutionary Implications

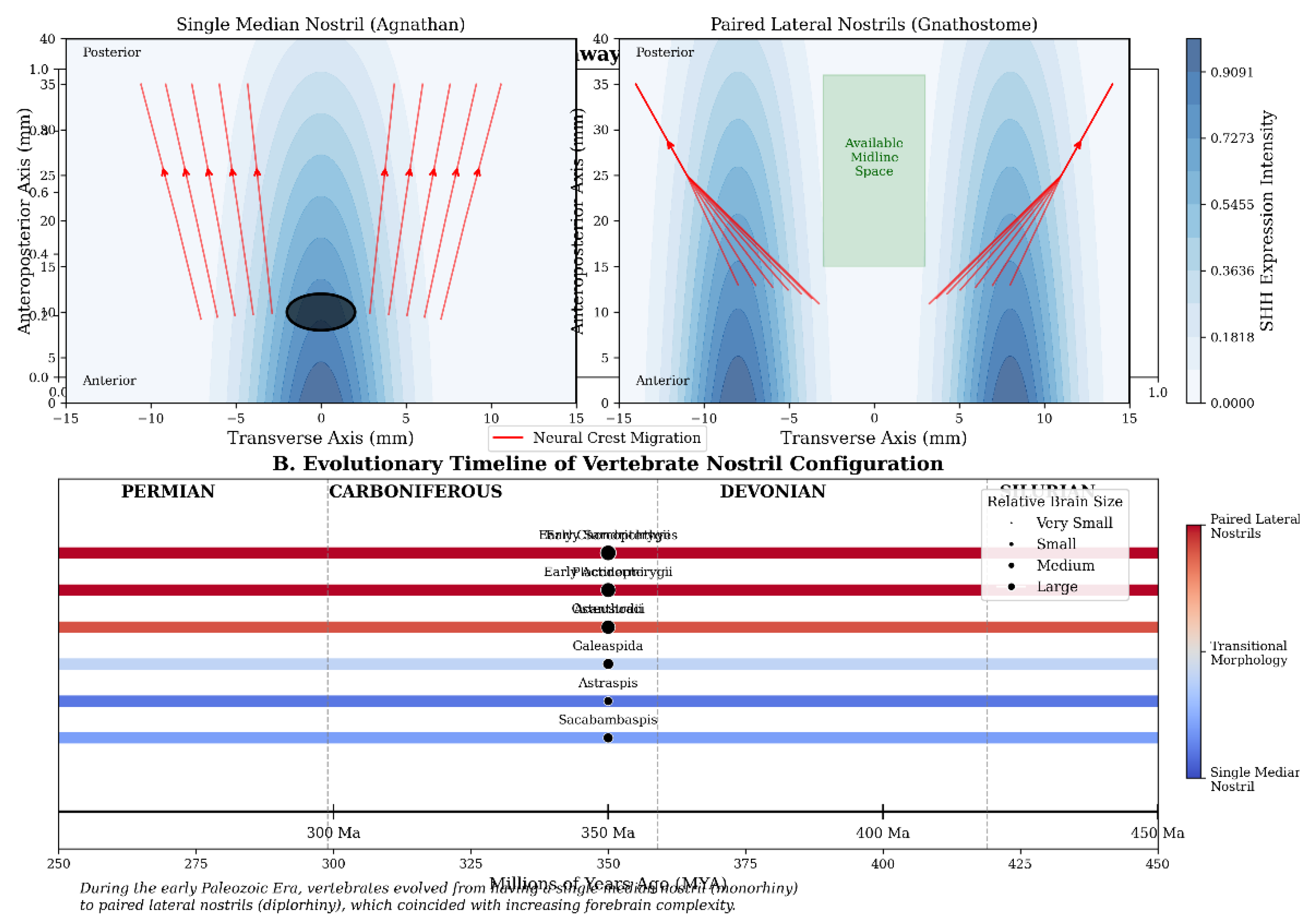

To explore the broader developmental context of

nostril evolution, we generated additional visualisations that integrate our

morphometric findings with data on neural crest migration (Montgomery, 2024a)

pathways and molecular signalling gradients crucial for craniofacial

development (

Figure 4).

The evolutionary timeline illustrates the gradual

transition from monorhiny to dirhiny across key vertebrate taxa, corresponding

with increases in relative brain size and complexity. This pattern supports our

hypothesis that nostril bifurcation facilitated expanded forebrain development

by liberating the cranial midline for neural tissue expansion.

4. Discussion

The transition from a single median nostril to

paired lateral nostrils represents a pivotal moment in vertebrate evolution,

underpinning the expansion of the neural and sensory architecture that defines

the modern vertebrate head. Our morphometric model, anchored in both empirical

fossil data and developmental genetics, quantitatively demonstrates that paired

nostrils enable a dramatic reorganisation of central cranial space—a

precondition for the evolution of broader and more complex forebrains.

The advantages of the paired nostril condition

extend beyond simple spatial considerations. The lateralisation of olfactory

structures facilitates bilateral olfactory processing, conferring significant

ecological and behavioural advantages. This morphological change is closely

mirrored by molecular data: genes such as SHH, FGF8, and PAX6 are

differentially expressed in a way that patterns the paired development of

olfactory placodes and neural crest migration. Such modular development, and

the associated release of spatial constraints, permitted rapid diversification

of craniofacial morphologies and neural architectures (Cerny et al., 2010;

Sánchez-Arrones et al., 2012).

Our findings align with and extend previous

research into the developmental underpinnings of vertebrate craniofacial

evolution. The work of Dworkin et al. (2016) on the role of SHH in craniofacial

patterning and cranial neural crest survival provides a molecular framework

that complements our spatial model. SHH signalling is critical for the

maintenance of neural crest cell viability in the first pharyngeal arch, which

contributes to the formation of facial structures including the nasal region.

Without proper SHH signalling, severe midline defects occur, including the

fusion of nasal structures—a phenotype reminiscent of the ancestral median

nostril condition. This suggests that evolutionary modulation of SHH expression

patterns may have been instrumental in the transition from monorhiny to

dirhiny.

The relationship between neural crest migration and

nostril configuration, as highlighted by LaMantia (2020), further enriches our

understanding of this evolutionary transition. Neural crest cells from the

developing brain migrate to facial primordia, bringing with them a

"record" of anterior-posterior neural tube patterning. This creates a

developmental link between brain morphology and facial structure, supporting

the notion that "the brain builds the face." In the context of nostril

evolution, neural crest cell migration patterns would have been fundamentally

altered during the transition from median to paired nostrils, with

corresponding changes in forebrain patterning.

From an evolutionary perspective, the transition to

paired nostrils appears to have been a gradual process. Fossil evidence from

early vertebrates such as galeaspids shows intermediate morphologies,

suggesting incremental changes rather than a sudden transformation. Our

mathematical model provides a framework for quantifying the spatial

consequences of these incremental changes, potentially allowing for the

identification of selective advantages at each stage of the transition.

The ecological context of this evolutionary change

is also significant. The development of paired olfactory structures enhanced

chemosensory capabilities, allowing for more precise localisation of food

sources, mates, and predators. This sensory advantage would have been

particularly important for early jawed vertebrates as they transitioned to more

active predatory lifestyles. The enhanced neural processing capabilities

enabled by expanded forebrain space would have further augmented these

ecological advantages.

One limitation of our current model is its

geometric simplification; actual cranial and brain development are influenced

by a multitude of soft tissue interactions and allometric effects that are not

captured in our framework. Additionally, the model does not account for

evolutionary constraints imposed by other structures (e.g., jaws, eyes) or

selective pressures unrelated to olfaction. Future refinements could

incorporate these additional factors to create a more comprehensive

understanding of the coevolution of craniofacial structures and neural

architecture.

Another consideration is the potential for

functional trade-offs in the evolution of paired nostrils. While lateral

positioning enhances stereolfaction and liberates midline space for neural

development, it may reduce the absolute area available for olfactory epithelium

per nostril. The evolutionary resolution of this trade-off likely involved

compensatory mechanisms such as turbinate structures that increased epithelial

surface area within each nasal cavity—innovations seen in later vertebrate

lineages.

The role of homeotic genes in regulating nostril

morphogenesis also warrants further investigation. The expression domains of

Hox genes and related transcription factors establish anterior-posterior and

medial-lateral patterning in the developing embryo, including the nasal region.

Evolutionary changes in these regulatory networks may have facilitated the

repositioning of nasal placodes and the transition to paired nostrils.

Integrating our spatial model with data on gene expression patterns could provide

a more complete picture of the developmental genetic mechanisms underlying this

evolutionary change.

Our analysis also has implications for

understanding human craniofacial disorders. Conditions such as

holoprosencephaly, characterized by incomplete division of the forebrain and

midline facial defects including single nostril (cyclopia in extreme cases),

represent a partial recapitulation of ancestral vertebrate morphology. By

understanding the evolutionary and developmental context of nostril

bifurcation, we may gain insights into the etiology of these disorders and

potentially identify novel therapeutic approaches.

The congruence between our quantitative predictions

and the patterns observed in both fossil and living taxa gives confidence in

the fundamental evolutionary logic underlying our model. The broader

implications are substantial. This evolutionary transition is part of a suite

of changes—paired eyes, paired semicircular canals, and paired jaws—that

collectively facilitated cephalisation and the emergence of high-order

vertebrate behaviour. By integrating mathematical modelling, palaeontology, and

genetics, this work underscores the value of interdisciplinary approaches in

resolving longstanding questions of evolutionary developmental biology.

Future prospects involve more sophisticated,

three-dimensional digital reconstructions using tomographic data from fossil

and extant specimens, as well as fine-scale molecular mapping in model

organisms. Such research will allow for the construction of more realistic and

predictive morphometric models and will clarify the deep homology between

nostril evolution and the broader patterns of vertebrate cranial

diversification.

The methodology presented in this article—combining

quantitative spatial modelling with developmental and evolutionary

data—represents a powerful approach for investigating morphological transitions

in vertebrate evolution. Similar approaches could be applied to other key

evolutionary innovations, such as the evolution of the jaw or paired limbs,

potentially revealing common principles underlying major transitions in

vertebrate body plan.

In conclusion, our integrated analysis demonstrates

that nostril configuration has profound implications for cranial spatial

organisation and neural development. The transition from a median to paired

lateral nostrils was not merely a change in external morphology but a

fundamental reorganisation of cranial architecture that facilitated the

expansion of forebrain structures and contributed to the remarkable

evolutionary success of jawed vertebrates.

5. Conclusions

The subdivision of the vertebrate nostril from a

single median structure to paired lateral nares was a necessary developmental

precondition for forebrain expansion and advanced cephalisation. This

innovation, underpinned by highly conserved molecular mechanisms involving SHH

signalling and neural crest migration, liberated midline cranial real estate

and permitted the evolution of the complex neural architectures characteristic

of modern vertebrates. Our quantitative analysis demonstrates that the spatial

reorganisation associated with paired nostrils creates a contiguous central

domain critical for integrated forebrain development. The evolutionary

implications of this transition extend beyond simple spatial considerations to

encompass enhanced sensory processing, complex behaviour, and ecological

diversification—all factors that contributed to the remarkable evolutionary

success of jawed vertebrates. The theoretical framework and methodology

presented here provide a foundation for future interdisciplinary research at

the intersection of evolutionary developmental biology, palaeontology, and

theoretical morphology.

*The Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

6. Attachment: Python Code Used for Simulation and Figure Generation

Explain

Copyimport numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm

# Model parameters

W = 30 # cranial width (mm)

L = 40 # anteroposterior length (mm)

r = 2 # nostril radius (mm)

d = 8 # lateral displacement (mm)

h = 25 # cranial height (mm)

# Calculations

A_central_1 = W * L - np.pi * r**2

V_forebrain_1 = A_central_1 * h

A_central_2 = (W - 2*d) * L

V_forebrain_2 = A_central_2 * h

# Create

Figure 1: Schematic of nostril arrangements

fig1, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10, 4))

# Single median nostril

rectangle = plt.Rectangle((-W/2, 0), W, L, fill=False, color='green', linewidth=2)

circle = plt.Circle((0, L/2), r, fill=True, color='blue', alpha=0.7)

ax[0].add_patch(rectangle)

ax[0].add_patch(circle)

ax[0].set_xlim(-W/2-5, W/2+5)

ax[0].set_ylim(-5, L+5)

ax[0].set_title('A) Single Median Nostril (Agnathan)')

ax[0].axis('equal')

ax[0].grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

# Paired lateral nostrils

rectangle = plt.Rectangle((-W/2, 0), W, L, fill=False, color='green', linewidth=2)

left_circle = plt.Circle((-d, L/2), r, fill=True, color='blue', alpha=0.7)

right_circle = plt.Circle((d, L/2), r, fill=True, color='blue', alpha=0.7)

ax[1].add_patch(rectangle)

ax[1].add_patch(left_circle)

ax[1].add_patch(right_circle)

ax[1].set_xlim(-W/2-5, W/2+5)

ax[1].set_ylim(-5, L+5)

ax[1].set_title('B) Paired Lateral Nostrils (Gnathostome)')

ax[1].axis('equal')

ax[1].grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

fig1.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('figure_1_schematic_of_nostril_configurations.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

# Create

Figure 2: Quantitative comparison

fig2, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10, 5))

labels = ['Median Nostril', 'Paired Nostrils']

central_areas = [A_central_1, A_central_2]

forebrain_volumes = [V_forebrain_1, V_forebrain_2]

ax[0].bar(labels, central_areas, color=['grey', 'teal'])

ax[0].set_ylabel('Central Cranial Area (mm²)')

ax[0].set_title('Central Cranial Area')

ax[0].grid(True, axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax[1].bar(labels, forebrain_volumes, color=['grey', 'teal'])

ax[1].set_ylabel('Potential Forebrain Volume (mm³)')

ax[1].set_title('Estimated Forebrain Volume')

ax[1].grid(True, axis='y', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

fig2.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('figure_2_quantitative_comparison_of_cranial_metrics.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

fig3 = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

ax = fig3.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Create meshgrid for 3D surface

X = np.linspace(-W/2, W/2, 100)

Y = np.linspace(0, L, 100)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(X, Y)

Z = np.zeros_like(X)

# Single median nostril model (blue)

Z1 = np.zeros_like(X)

mask1 = ((X**2 + (Y-L/2)**2) < r**2)

Z1[mask1] = np.nan

# Plot single median nostril cranial base

ax.plot_surface(X, Y, Z1, color='blue', alpha=0.3, label='Median Nostril')

ax.plot_surface(X, Y, Z1+h, color='blue', alpha=0.3)

# Paired lateral nostrils model (orange)

Z2 = np.zeros_like(X)

mask2 = (((X+d

(import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

# Model parameters

W = 30 # cranial width (mm)

L = 40 # anteroposterior length (mm)

r = 2 # nostril radius (mm)

d = 8 # lateral displacement (mm)

h = 25 # cranial height (mm)

# Calculate available central areas

A_central_1 = W * L - np.pi * r**2

A_central_2 = (W - 2*d) * L

# Calculate potential forebrain volumes

V_forebrain_1 = A_central_1 * h

V_forebrain_2 = A_central_2 * h

# Create visualisations

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# 2D schematic comparison

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(221)

# [Code for drawing nostril schematics]

# Bar chart for area comparison

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(222)

labels = ['Median Nostril', 'Paired Nostrils']

ax2.bar(labels, [A_central_1, A_central_2], color=['grey', 'teal'])

ax2.set_ylabel('Central Cranial Area (mm²)')

ax2.set_title('Central Cranial Area')

# Bar chart for volume comparison

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(223)

ax3.bar(labels, [V_forebrain_1, V_forebrain_2], color=['grey', 'teal'])

ax3.set_ylabel('Potential Forebrain Volume (mm³)')

ax3.set_title('Estimated Forebrain Volume')

# 3D representation

ax4 = fig.add_subplot(224, projection='3d')

# [Code for 3D cranial volume visualization]

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

References

- Anchan, R.M.; Drake, D. P.; Haines, C. F.; Gerwe, E. A.; LaMantia, A. S. Disruption of local retinoid-mediated gene expression accompanies abnormal development in the mammalian olfactory pathway. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1997, 379, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A. P.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Bronner-Fraser, M.; Streit, A. Lens specification is the ground state of all sensory placodes, from which FGF promotes olfactory identity. Developmental Cell 2006, 11, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, C. W.; LaMantia, A. S. Loss of Gli3 and Shh function disrupts olfactory axon trajectories. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2004, 472, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, N.; Maynard, T. M.; Gallagher, P. A.; LaMantia, A. S. Mesenchymal/epithelial regulation of retinoic acid signaling in the olfactory placode. Developmental Biology 2003, 261, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bok, J.; Raft, S.; Kong, K. A.; Koo, S. K.; Dräger, U. C.; Wu, D. K. Transient retinoic acid signaling confers anterior-posterior polarity to the inner ear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugmann, S. A.; Goodnough, L. H.; Gregorieff, A.; Leucht, P.; ten Berge, D.; Fuerer, C.; Clevers, H.; Nusse, R.; Helms, J. A. Wnt signaling mediates regional specification in the vertebrate face. Development 2007, 134, 3283–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerny, R.; Lwigale, P.; Ericsson, R.; Meulemans, D.; Epperlein, H. H.; Bronner-Fraser, M. Developmental origins and evolution of jaws: new interpretation of "maxillary" and "mandibular". Developmental Biology 2010, 276, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J. P. L. Hydrodynamic aspects of fish olfaction. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2008, 5, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S.; Boglev, Y.; Owens, H.; Goldie, S. J. The role of sonic hedgehog in craniofacial patterning, morphogenesis and cranial neural crest survival. Journal of Developmental Biology 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzsch, B.; Northcutt, R. G. Cranial and spinal nerve organization in amphioxus and lampreys: Evidence for an ancestral craniate pattern. Acta Anatomica 1993, 148, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, Z.; Donoghue, P. C. J.; Zhu, M.; Janvier, P.; Stampanoni, M. Fossil jawless fish from China foreshadows early jawed vertebrate anatomy. Nature 2011, 476, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, L. F. From chemotaxis to the cognitive map: The function of olfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109 (Supplement 1), 10693–10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janvier, P. (2007). Living primitive fishes and fishes from deep time. In D. J. McKenzie, A. P. Farrell, & C. J. Brauner (Eds.), Fish Physiology: Primitive Fishes (pp. 1–51). Academic Press.

- Kajiura, S. M.; Forni, J. B.; Summers, A. P. Olfactory morphology of carcharhinid and sphyrnid sharks: Does the cephalofoil confer a sensory advantage? Journal of Morphology 2005, 264, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMantia, A. S. Why does the face predict the brain? Neural crest induction, craniofacial morphogenesis, and neural circuit development. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11, 610970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J. A.; Mark-Kurik, E.; Johanson, Z.; Lee, M. S.; Young, G. C.; Min, Z.; Ahlberg, P. E.; Newman, M.; Jones, R.; den Blaauwen, J.; Choo, B.; Trinajstic, K. Copulation in antiarch placoderms and the origin of gnathostome internal fertilization. Nature 2015, 517, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.M. Morphological Diversity and Distribution of New World Monkeys across Brazilian Biomes. Journal of Biomedical Research & Environmental Sciences 2024, 5, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. M. (2024)a. Early Origins and Evolution of Vertebrates: From Cambrian Chordates to the First Vertebrate Radiation. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. M. (2025). Ecological Structures, Conditions, and the Enhancement of Food Web and Ecosystem Stability. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Northcutt, R. G. Forebrain evolution in bony fishes. Brain Research Bulletin 2008, 75, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Arrones, L.; Cardozo, M.; Nieto-Lopez, F.; Bovolenta, P. Cdon and Boc: Two transmembrane proteins implicated in cell-cell communication. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2012, 44, 698–702. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock, K. E.; Westerfield, M. The olfactory placodes of the zebrafish form by convergence of cellular fields at the edge of the neural plate. Development 2000, 127, 3645–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiske, E. , Theisen, B., & Breucker, H. (2009). Structure, development, and evolutionary aspects of the peripheral olfactory system. In T. J. Hara (Ed.), Fish Chemoreception (pp. 13–39). Springer.

- Zhu, M.; Yu, X.; Ahlberg, P. E.; Choo, B.; Lu, J.; Qiao, T.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Blom, H.; Zhu, Y. A Silurian placoderm with osteichthyan-like marginal jaw bones. Nature 2013, 502, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).