Introduction

The determination of sex in human skeletal remains is typically performed macroscopically, with the morphognostic assessment of pelvic and cranial traits being the primary method of analysis. In well-preserved skeletons, this approach is reliable with accuracies ranging from 90 to 97 %, depending on the methods and traits utilized (Inskip et al., 2019; Meindl et al., 1985; Thomas et al., 2016). However, in forensic cases and archaeological studies, the preservation of the bones is frequently poor and highly fragmented, necessitating the use of less reliable but nevertheless sexually dimorphic features. Such methods commonly employ length measurements of sexually dimorphic anatomical structures. This is due to the general assumption that males are, on average, larger than females and that skeletal structures are also more robust because of the higher muscle mass in males (Stock, 2020). A notable skeletal element that is frequently recovered in inhumation burials and often survives even a cremation process in at least large pieces is the petrous bone (Lynnerup et al., 2006; Norén et al., 2005; Wahl & Graw, 2001).

The petrous bone, a part of the temporal bone, is a robust and dense skeletal element located at the cranial base, which is a relatively well-protected area of the cranium. The internal acoustic meatus is the conduit through which the facial nerve, the vestibulocochlear nerve, and two blood vessels (the arteria and vena labyrinthi) pass to supply the inner ear (Drake & Mitchell, 2007). Originating in the cerebellum and the truncus encephali, both nerves are of particular interest in this anatomical region. Anatomically, the internal acoustic meatus forms a conically shaped canal that becomes narrower from medial to lateral. The facial nerve exits the petrous bone via the facial canal, while the vestibulocochlear nerve supplies the inner ear.

One feature that has been shown to be sexually dimorphic, is the so-called lateral angle of the internal acoustic meatus, first defined by Wahl (1981). The lateral angle is the acute angle formed by the lateral wall of the internal acoustic meatus and the posterior surface of the petrous bone (Graw et al., 2005; Wahl, 1981). A number of studies have indicated that this angle may be used for sex determination in inhumation burials (Akansel et al., 2008; Graw et al., 2005; Norén et al., 2005; Wahl & Graw, 2001) and in cremations (Masotti et al., 2019; Schutkowski & Herrmann, 1983; Wahl, 1981). In general, the lateral angle is larger in females than in males (Akansel et al., 2008; Bonczarowska et al., 2021; El-sherbeney et al., 2012; Gonçalves et al., 2011; Graw et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2013; Norén et al., 2005; Wahl, 1981). According to Wahl (1981), a lateral angle above 45° is indicative of the subject being female, whereas a lateral angle measuring 45° is indicative of the subject being male. While several studies confirmed the 45° cut-off point with good accuracy (Akansel et al., 2008; Kozerska et al., 2020; Norén et al., 2005), others have proposed divergent cut-off points that have proven more effective for their particular samples (El-sherbeney et al., 2012; Masotti et al., 2019; Waltenberger et al., 2024). Furthermore, several studies have indicated that the lateral angle is an imprecise and unreliable method because of its high degree of overlap between males and females and large confidence regions (Bonczarowska et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2011; Graw et al., 2005; Masotti et al., 2013; Morgan et al., 2013; Schutkowski & Herrmann, 1983; Wahl, 1981). The accuracy of using the lateral angle for sex determination exhibited significant variation across studies, ranging from an accuracy comparable to a coin toss, approximately 50 % (Bonczarowska et al., 2021; Morgan et al., 2013), to over 80 % of individuals being correctly classified (El-sherbeney et al., 2012; Norén et al., 2005). Thus, researchers hypothesized an association of the lateral angle with age (Afacan et al., 2017; Akansel et al., 2008; Gonçalves et al., 2011; Kozerska et al., 2020; Masotti et al., 2019; Wahl & Graw, 2001), and this association was suspected to be population-specific (Pezo-Lanfranco & Haetinger, 2021; Waltenberger et al., 2024). Furthermore, the techniques utilized to measure the lateral angle, particularly those techniques employed for the measurements of virtual scans and models, or casts derived from dry bone material, appear to yield divergent results (Bonczarowska et al., 2021; Masotti et al., 2013; Waltenberger et al., 2024).

It is important to note that the petrous bone reaches approximately half of its full size at two years of age and does not undergo further bone remodeling of the otic capsule, the bone surrounding the inner ear, and proceeds with much slower rates of development until adulthood (Doden & Halves, 1984; Frisch et al., 2000). Consequently, researchers have assumed that the lateral angle is already sexually dimorphic in subadult individuals, likely attributable to increased rugosity of muscle attachment at the temporal and occipital bones in males (Gonçalves et al., 2011; Norén et al., 2005). This assumption is further supported by the study of Duquesnel Mana et al. (2016), who analyzed the basicranial shape and found that the sexual dimorphism is most pronounced in the region of the sigmoid and transverse sulci, although these differences were not significant. Studies have indicated that the sexual dimorphism in cranial shape is predominantly caused by size differences and variation of the robustness of muscle attachment sites, with male crania being larger and more rugged on average (Duquesnel Mana et al., 2016; Rösing et al., 2007). Thus, one can hypothesize that the sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle may evolve during puberty. However, studies conducted on subadult samples are rare, and the findings are inconsistent. For instance, Gonçalves et al. (2011) claimed that the lateral angle is already sexually dimorphic in children younger than 15 years, with the strongest results observed in the 2- to 5-year age group. However, the sample size of this study was very small, and the accuracy decreased again to 55 %. Thus, these results can be attributed to the small and uneven sample size. In contrast, Afacan et al. (2017) failed to identify any statistically significant differences. A slight decrease in the lateral angle during childhood was found in both studies.

The aim of this study was to analyze the development of sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle from birth up to adulthood in a sample with known sex and age at death of the individuals. In addition to the repeated testing of eligibility using the lateral method as a method for sex determination, it is imperative to delve deeper into the underlying reasons why a tiny aperture at the cranial base exhibits sexual dimorphism and the manner in which it evolves during childhood. The hypothesis is that sexual dimorphism may develop during puberty or, alternatively, in early adulthood until complete skeletal maturation. This comprehensive approach could facilitate a more profound understanding of the lateral angle geometry and its interpopulation variation.

Methods

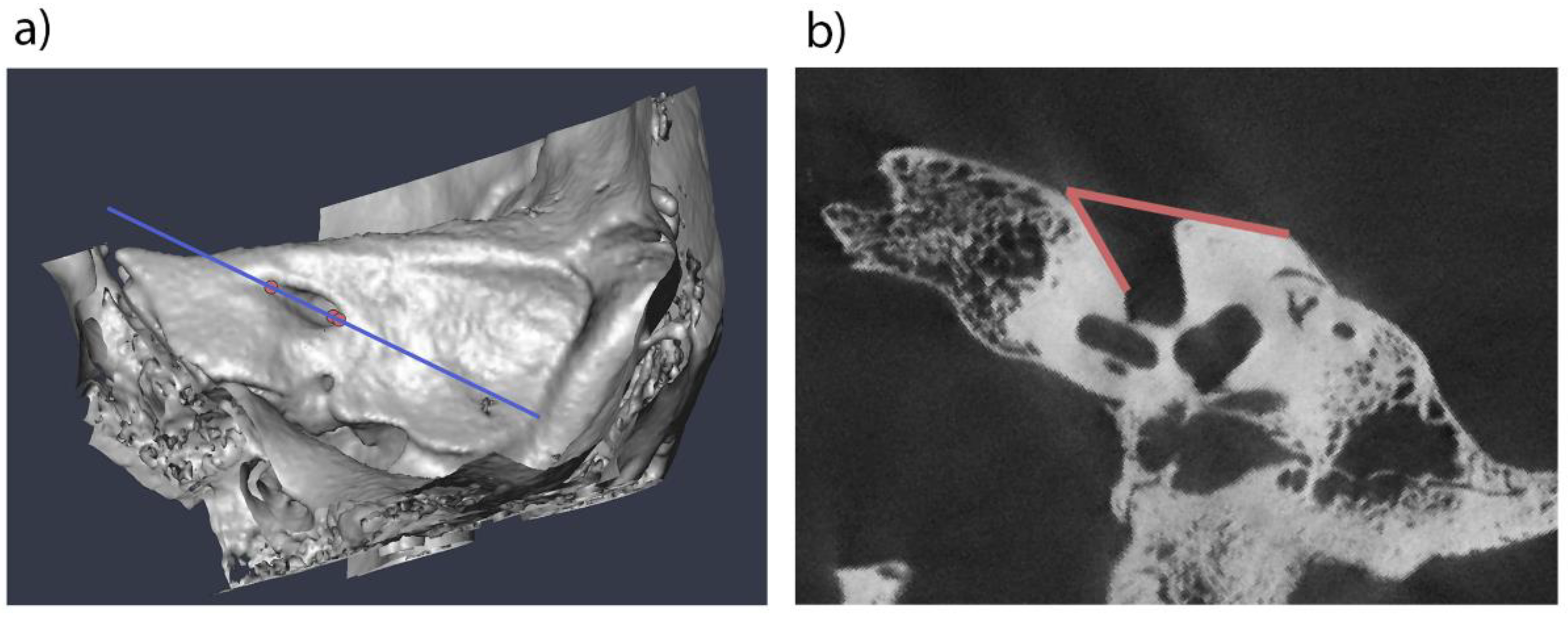

We used four samples in this study to analyze the development of the lateral angle during childhood, with the objective of identifying causal factors. Initially, the micro-CT scans of three museum osteological collections from 19th-century Austria were examined: 50 skulls of the Collection of the Anatomical Institute of Vienna (Horn, 1997), 49 of the Collection of the Anatomical Institute of Graz (only inscriptions on the crania available), and 17 of the Terzer Collection (Pawlowsky, 2001; Stiebitz, 1997). These three collections primarily comprise skulls of subadult individuals. Some background information, including sex, age at death, year of death is known, mostly from inscriptions on the skulls themselves. The Terzer collection predominantly contains samples of individuals under three years of age, the Collection of the Anatomical Institute of Vienna contains subjects under 10 years of age, and the Collection of the Anatomical Institute of Graz spans the age range from three years to 25 years. Exclusion criteria for all samples were pathological conditions affecting the cranial shape and any known or visible cranial trauma on the CT scans. Inclusion criteria were crania of individuals who died between birth and 30 years of age. As male features at the crania tend to become further pronounced in early adulthood, we expand our sample to individuals who died in their 20ies. All crania were micro-CT scanned at the Core Facility of Microcomputed Tomography of the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna (scanner model Viscom X8060) with a isovoxel size of 39-79 µm depending on the field of view. The micro-CT scans were semiautomatically segmented in the software Amira 6.1.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 2018). The internal acoustic meatus was then intersected using the landmark-based method developed by Waltenberger et al. (2024). Angle measurements of the lateral angle were performed on images using the Fiji 1.54g software (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the angle measurement tool (

Figure 1).

Furthermore, we measured the bi-auricular breadth (AUB, Martin (1957)) in order to ascertain a potential association with the lateral angle. Given the rarity of individuals between the ages 17 to 25 in the historical samples (5 individuals), which were exclusively males, the decision was made to enhance the dataset by including recent data from individuals who died between the 12th and 30th year of life. This approach was taken to identify any potential changes in cranial breadth from puberty to early adulthood. The data was obtained from the New Mexico Decedent Database (NMDID, Edgar et al. (2020)) by selecting groups of equal size for males and females and including four individuals of the same age to ensure continuous data from 12 to 30 years (n = 114). The study exclusively included individuals of European ancestry, thereby facilitating comparability with the Austrian historical collections. The NMDID collection contains whole-body CT scans of corpses examined in the coroner’s office in Albuquerque with a resolution of 0.5 x 0.5 mm per pixel and a slice thickness of 0.6 mm. Given the lower resolution of the NMDID database in comparison to that of the micro-CT scans, we decided to only measure the bi-auricular width as a proxy for lateral angle changes, thus avoiding a methodological bias in the lateral angle measurements. The subsequent analysis of the data was conducted using multiple linear regression models, binary logistic regression, LOESS regression, mixed regression models to account for samples from different collections, and Response Operating Characteristic- (ROC-) curves in R-statistics 4.4.1 utilizing the packages visreg (Breheny & Burchett, 2017), ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), boot (Canty & Ripley, 2024; Davison & Hinkley, 1997), and verification (Gilleland et al., 2004). In the multiple regression models, the lateral angle was used as independent variable, whereas predictors were the biauricular breadth, and age at death. In the binary logistic regression models, we predicted sex with the lateral angle and biaricular breadth respectively. To test for differences in the development of the biauricular width in females and males, we analyzed differences in the smoothed moving average of the LOESS regressions including a bootstrap analysis. For this, 1000 new samples were drawn based on the original data with retention of the cases after each draw. The LOESS regressions were calculated and differences between the prediction of the age noted. Based on these differences, bias-corrected and accelerated-confidence intervals were calculated. If the differences between males and females were larger than 95 % prediction intervals, these time periods were determined as showing significantly different development rates of the biauricular width. A level of significance of p = 0.05 was used and all significant p-values were corrected using a Bonferroni-Holm correction (Holm, 1979) to deal with multiple testing.

Results

First, the subjects from the Grazer collection who were older than 21 years were excluded from the study. The reason for the exclusion was that these subjects formed a distinct cluster in the scatterplots, deviating from the primary point cloud. Furthermore, these subjects demonstrated higher measurements of the bi-auricular breadth in comparison to the NMDID data. As the inclusion criteria for these individuals into the Grazer collection was unknown and they may have been selected for anomalies, they were excluded from further study. During the course of data collection, 19 individuals (12 males, 6 females) from the NMDID sample were excluded due to the absence of cranial CT scans or the presence of visible antemortem and perimortem traumata of the cranium that were not disclosed in the background information. A descriptive overview of the four collections can be seen in

Tab 1, raw data is present in SI1.

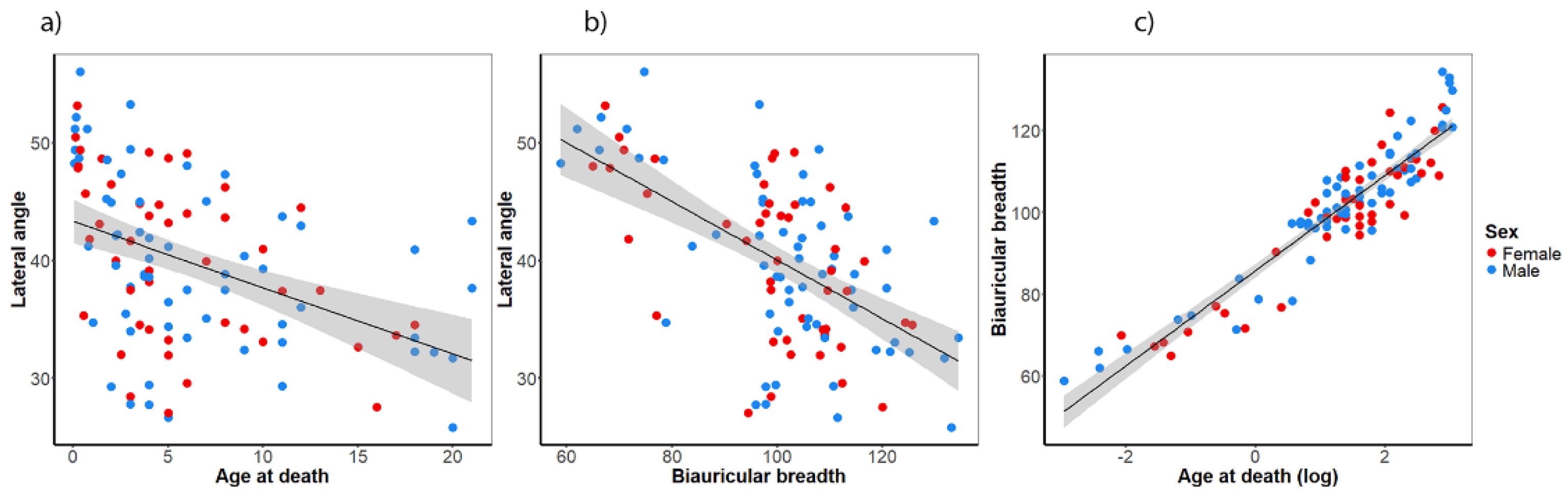

First, we used mixed regression to account for samples from different collections but decided to use simpler regression models because the sample distributions were in line with other studies (e.g., Afacan et al. (2017)). We analyzed the developmental trajectory of the lateral angle during the childhood period. To this end, a linear regression model was employed, incorporating the lateral angle as a function of age at death, with both female and male subjects combined. The linear regression model revealed a significant decrease in the lateral angle during childhood (

R2 = 0.188,

p < 0.001,

βangle = -0.335,

Figure 2a). The highest values of the lateral angle were measured in children in their first year of life (

mean = 48.1°,

sd = 5.1°). In a similar manner, the biauricular breadth showed a significant associated with the lateral angle (

R2 = 0.336,

p < 0.001,

βangle = -1.349,

Figure 2b). The biauricular breadth accounted for a considerably higher portion of the total variance in the lateral angle than age at death. By employing a regression analysis, in which age at death (log-transformed) and the biauricular breadth were dependent and independent variables, respectively, it was demonstrated that age at death influences both the lateral angle and the biauricular breadth (

Figure 1c). As anticipated, multicollinearity may underlie the observed association between the lateral angle and age, given that children are undergoing growth, which leads to an increase of cranial dimensions with age. To address this potential multicollinearity, we opted to calculate a third linear regression model incorporating cranial breadth as a covariate to adjust for age at death. This analysis revealed that the association between age at death and the lateral angle became non-significant, although the partial regression coefficient of the biauricular breadth remained significant (

adjusted R2 = 0.325,

p < 0.001,

βage = 0.092,

pβ-age = 0.595,

βAUB = -0.274,

pβ-AUB < 0.001). This finding implies that cranial breadth is the fundamental factor that influences the size of the lateral angle.

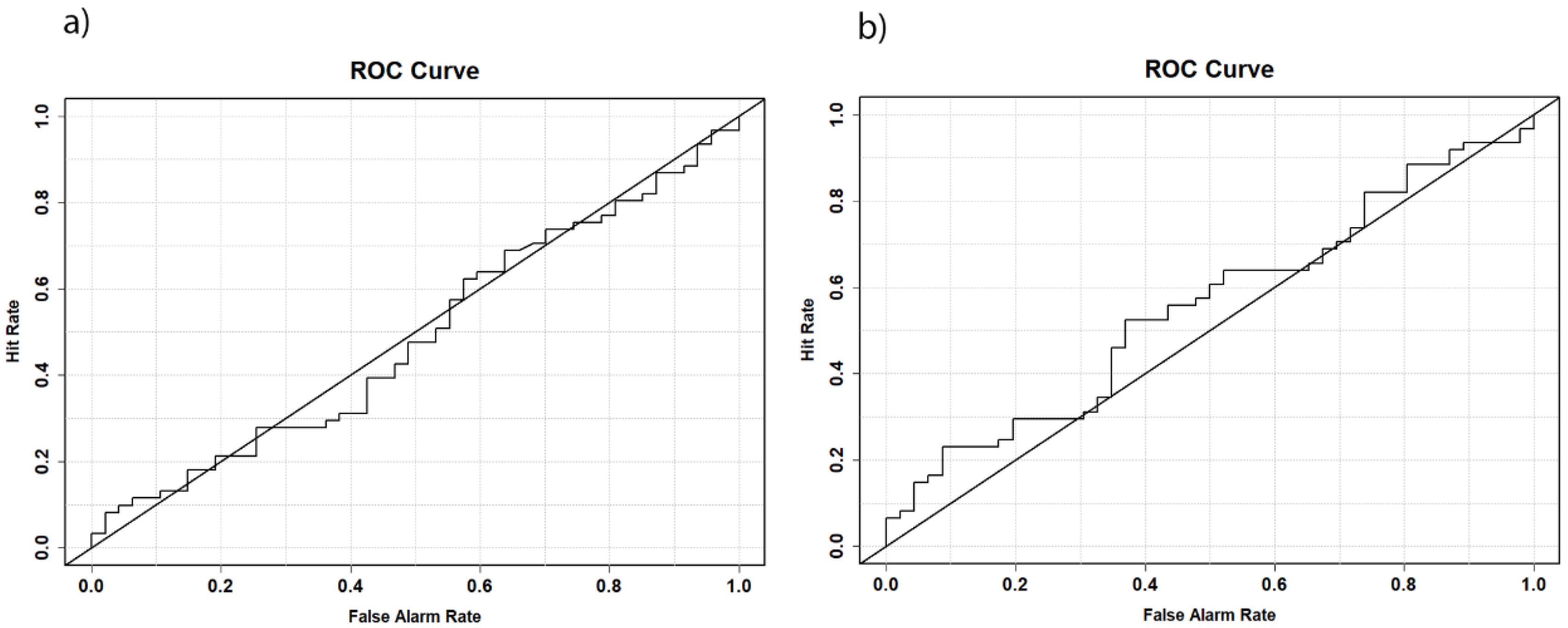

Next, we examined sex differences in the lateral angle during the developmental stage of childhood. In the event of a significant difference in the lateral angle already present in children, a good classification could be expected using a ROC model. However, the classification of the lateral angle using a ROC curve (

AUC = 0.488,

Figure 3a) did not follow this expectation. The model performed no better than chance, suggesting that the lateral angle cannot be used for sex determination in subadult individuals. A similar outcome was observed when the biauricular width was analyzed (

AUC = 0.553,

Figure 3b). These findings imply that the lateral angle is predominantly influenced by the cranial dimensions. Individuals with a larger cranial breadth exhibited smaller lateral angle measurements and vice versa. Furthermore, no sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle could be detected in the subadult samples. Next, we analyzed the biauricular breadth in detail as a proxy for the lateral angle in different samples to bring further insights into this hypothesis.

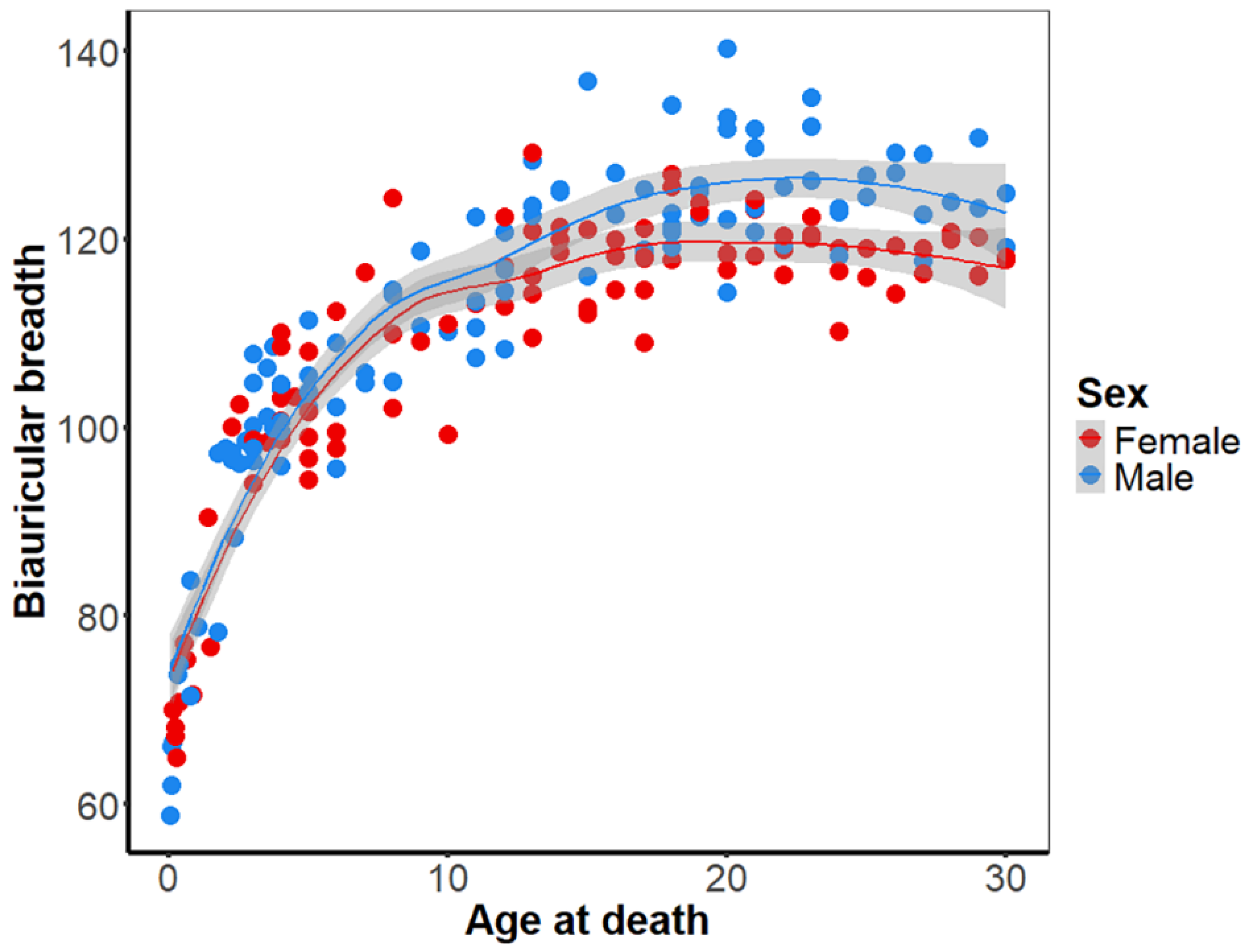

The development of the biauricular breadth over the course of childhood is comparable between females and males. In both males and females, the cranial breadth undergoes a logarithmic development, marked by a substantial increase in the initial years of life and subsequent decline from the 10th year onwards. The onset of sexual dimorphism has been observed to occur during puberty (

Figure 4, SI2), as evidenced by the separation of the LOESS regression lines between females and males at the age of 16 years. This separation suggests that from this point onward, sexual dimorphism may be sufficiently large to be discernible through statistical methods. To evaluate this assumption in detail, we compared the slopes of the non-linear regression between males and females. Cranial breadth exhibited a comparable development and accelerated growth in individuals up to the ninth year of life. From the age of ten years onwards, the cranial breadth development is higher in males than in females. Statistical analysis reveals that the slopes of these two phases, the resting period in females and the rapid development in males during puberty, are significantly different. The utilization of bootstrap resampling to minimize noise in the results substantiates this finding. The results show that sexual dimorphism of the cranial breadth, and consequently the lateral angle, is established during puberty (see appendix A for further details. The negative values indicate that the male specimens exhibit a greater biauricular breadth than the female specimens.

Discussion

This study has shown that the lateral angle is not sexually dimorphic in young children and is likely to develop during puberty. The lateral angle is strongly associated with the biauricular breadth. Many cranial dimensions, including the cranial breadth are known to be sexually dimorphic in many populations and may explain differences in the accuracy of the use of the lateral angle as a method of sex determination in osteology. Variation in the cut-off points of the lateral angle is likely to be influenced by interpopulation differences.

The Development of the Lateral Angle During Childhood

This study was unable to identify a sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle in children; As expected, the most plausible explanation would be that the sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle would form during puberty as for most sexually dimorphic skeletal features. However, it provides significant insights into its development and potential causes of the sexual dimorphism in the lateral angle. The present results are consistent with those of previous studies that also failed to identify significant differences in the lateral angle in subadults (Afacan et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2024), yet they stand in contrast to the results reported by Gonçalves et al. (2011). The divergent outcomes are hypothesized to be predominantly influenced by the limited sample size and the heterogeneous composition of the age groups in the study. The present study found that the lateral angle is, on average, the highest around birth and decreases during childhood in both sexes. This finding suggests that the sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle is established during puberty or early adulthood and is predominantly influenced by the sexual dimorphism of cranial dimensions. The sexual dimorphism may be attributed to the proximity to the brain, and in particular, the anatomical configuration of the nerves and blood vessels may permit shorter lengths of these structures in individuals with larger crania or mitigate the risk of compression by allowing more linear nerves and blood vessels within the constricted internal acoustic meatus. An analysis of the development of the lateral angle during childhood reveals a notable heterogeneity in our sample ranging from 11 to 16 years of age with a limited number of cases. This may have a bearing on the results, especially with regard to the risk of false-negative results for a sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle. Furthermore, the changes observed in the lateral angle may not be adequately represented by a linear regression model; alternatively, a non-linear model, such as a LOESS function, may prove more suitable. The examination of the development of the lateral angle in the age group of two to 16 years revealed that the negative association of the lateral angle with age completely vanished. This finding indicates that the most substantial alterations in the lateral angle primarily occur during the first years of life, coinciding with the period of accelerated growth of the petrous bone and subsequently during the adolescent phase. However, this trend is similar in both sexes, suggesting that the sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle will not already be evident in small children but will likely form as a kind of fine adaptation later in development.

The association between the lateral angle and cranial breadth, despite its simplified nature, offers intriguing insights into the development of the lateral angle and its sexual dimorphism and may offer a rationale for the inconsistent results reported by various researchers and potentially explains inter-population variability. A parallel can be drawn between the development of the lateral angle and that of the biauricular breadth in babies and toddlers, which gradually slows down over time, mirroring the development of the lateral angle. The present dataset was augmented with data from the NMDID, which yielded further insights into the developmental trajectories of cranial breadth until the 30th year of life. The results indicate that the development is predominantly different in males and females from 10 to 17 years of age, suggesting that this is the time period in which the sexual dimorphism will form. While acknowledging the limitations of the biauricular breadth as an estimate for the lateral angle, the results may offer a potential explanation for the observed variability in the accuracy of cut-off points for sex determination by lateral angle measurement. This variability has been documented in several studies (e.g., Masotti et al. (2013), Gonçalves et al. (2015), while others have reported significant differences between both sexes and sex determination methods with good accuracy (e.g., Norén et al. (2005), El-sherbeney et al. (2012), Waltenberger et al. (2024)).

Cranial dimensions demonstrate significant variability between populations, including the presence of sexual dimorphism at the cranium (Bigoni et al., 2010; da Silva et al., 2023; Nikita, 2014). The present study evaluated the biauricular breadth in the NMDID sample (n = 96) as well as the Howell dataset (n = 2524, Howells (1973), Howells (1989), Howells (1995)). Both datasets showed a significant association between the biauricular breadth and sex in binary logistic regression models (NMDID: p < 0.001, R2 = 0.260, Howell’s dataset: p < 0.001, all populations: R2 = 0.171, modern European populations: R2 = 0.298). This finding indicates that the lateral angle is strongly influenced by interpopulation differences. Controversially, in scenarios where a pronounced sexual dimorphism is observed in cranial dimensions, the lateral angle emerges as a reliable sex determination method, exhibiting a high degree of accuracy. Vice versa, the lateral angle can be utilized as a sex determination method with a high accuracy, if a pronounced sexual dimorphism is present in cranial dimensions. Consequently, it is not possible to define one universal cut-off point as a sex determination method. The development of methods for sex determination necessitates adaptation and validation across diverse populations to ensure its efficacy. Furthermore, it is challenging to apply cut-off points developed using recent data to archaeological remains. This is particularly evident in the case of prehistoric European populations, which often exhibit a greater degree of robustness in comparison to modern humans. Previous publications, for instance, from Austria, have demonstrated highly significant differences in the biauricular breadth in prehistoric grave fields from Austria (e.g., Berner (1988)). Similarly, we could define cut-off points for sex determination for Austrian Late Bronze Age populations with good accuracy (Waltenberger et al., 2024), although the sample size was quite small (n = 35). Given the reduced sexual dimorphism of the cranium observed in contemporary populations, the sample size may be a contributing factor to the failure of the lateral angle to yield significant results in the aforementioned studies. The presence of subtle sex differences in the lateral angle may have been obscured by random variation in the limited datasets employed in these studies. The identification of such differences necessitates the presence of substantial variances within small samples to detect more modest variations, a strategy that was frequently impracticable in studies of the lateral angle due to a multitude of factors.

Reproducibility of Studies

Furthermore, different cut-off points and the heterogeneity of published data on the lateral angle suggest a further issue: A review of publications reveals a range of lateral angle size measured from less than 30° to up to 80° in adults (e.g., Wahl (1981), Masotti et al. (2013)). Given the proximity of the lateral angle to brain structures, it is implausible that this variation merely represents biological variation. We suspect that the lateral angle measurements are highly dependent on the methods used, which also reduces replicability between studies. This is particularly evident in older studies, such as those by Wahl (1981) and Norén et al. (2005), which utilized casts of the internal acoustic meatus made from clay or silicone. Such casting materials have been demonstrated to potentially compromise the integrity of the original bones due to adhesion issues, in addition to the occurrence of shrinkage effects in the casts, which further complicates the accuracy of the measurements. Consequently, researchers adapted the original methods to 3D imaging techniques and employed CT scans of petrous bones. However, it should be noted that clinical CT scans generally provide a maximal resolution of 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.6 mm per voxel, which is inadequate for precise measurement of the lateral angle. Consequently, micro-CT scanning provides high-resolution images, which reduces random variability of the measurements and should be the method of choice. In addition, the application of the original method on virtual data is intuitive. We propose the utilization of the landmark-based method described in Waltenberger et al. (2024), which has demonstrated reduced inter- and intra-observer error in comparison to manual alignment techniques and may offer enhanced replicability over previous methodologies.

Limitations of This Study

There are several limitations to this study: First, our sample may be biased. We do not know the inclusion criteria used to select individuals for the historical anatomical collections. The researchers may have included the remains at random, depending on who died in the area and were able and allowed to collect. Likely, the historic sample may be comparative to frail individuals of an archaeological context and may not represent a healthy population. Some individuals were excluded in advance because of visible developmental conditions that may affect the shape of the cranium and therefore, the lateral angle (e.g., premature suture closure). Evidence that our sample may represent a living population can be found in the study by Afacan et al. (2017). They measured the lateral angle in 58 subadult patients aged between one month and 17 years. Their results showed a similar sample distribution across childhood, with greater variability in newborns and less variability in children.

Secondly, we only had data on the lateral angle in subadults, especially with a lot of data from people who died before puberty. Therefore, the results of the changes in the lateral angle in adolescents have to be treated with caution. Using cranial width as a proxy for changes in the lateral angle is only a rough model (one third of the variation in the lateral angle can be explained by the biauricular breadth; 66 % remains unknown). In this study, we used the most likely association with cranial breadth as a proxy because the lateral angle is part of the petrous bones, which are predominantly located in the mediolateral direction. However, causal factors are rarely simple, and we can expect at least a weak association with cranial length too.

Overall, the results of the lateral angle are consistent with the results of the biauricular breadth. However, the study needs to be repeated in the future with direct data on the lateral angle of individuals from puberty to young adulthood to better understand its development and the cause of sexual dimorphism. We suggest testing its causal factors first on a population that already shows a large sexual dimorphism of cranial dimensions, as in these samples, the association with causal factors is likely to be larger and not so easily hidden by random noise in the data set. Finally, we measured the lateral angle on CT scans using the method published by Waltenberger et al. (2024). As lateral angle measurements appear to be highly dependent on the method used, we would like to emphasize that this study may not be comparable with other studies on this topic due to methodological issues.

Conclusions

This study shows that the sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle probably developed during puberty as most anatomical structures exhibiting sex differences too. Therefore, the lateral angle cannot be used as a sex determination method in subadult individuals. Furthermore, we found a significant association of the lateral angle with the biauricular breadth as an underlying factor of sexual dimorphism, as well as an association with age. Cranial width is a sexually dimorphic dimension with different variability between populations. This association indicates interpopulation differences and probably explains why the lateral angle has been published as sexually dimorphic in some studies, while others have failed to find a significant association. In addition, the results may explain why universal cut-off points are imprecise, and why customized cut-off points are needed to be developed for different populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This study received funding from the FWF-funded project “Unlocking the secrets of cremated human remains” (Grant-DOI: 10.55776/P33533, Principal investigator: K. Rebay-Salisbury).

Authors’ contributions

LW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data analysis, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft; SL: Data analysis, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing; TD: Methodology, Investigation; MD: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing; LH: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing; ST: Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received ethical approval from the Medical University of Vienna (1799/2021).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in S1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

References

- Afacan, G. O., Onal, T., Akansel, G., & Arslan, A. S. (2017). Is the lateral angle of the internal acoustic canal sexually dimorphic in non-adults? An investigation by routine cranial magnetic resonance imaging. Homo, 68(5), 393-397. [CrossRef]

- Akansel, G., Inan, N., Kurtas, O., Sarisoy, H. T., Arslan, A., & Demirci, A. (2008). Gender and the lateral angle of the internal acoustic canal meatus as measured on computerized tomography of the temporal bone. Forensic Science International, 178(2-3), 93-95. [CrossRef]

- Berner, M. (1988). Das frühbronzezeitliche Gräberfeld von Franzhausen I: demographische und metrische Analyse. (Dissertation). Universität Wien, Wien.

- Bigoni, L., Velemínská, J., & Brůžek, J. (2010). Three-dimensional geometric morphometric analysis of cranio-facial sexual dimorphism in a Central European sample of known sex. Homo, 61(1), 16-32. [CrossRef]

- Bonczarowska, J. H., McWhirter, Z., & Kranioti, E. F. (2021). Sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle: Is it really applicable in forensic sex estimation? Arch Oral Biol, 124, 105052. [CrossRef]

- Breheny, P., & Burchett, W. (2017). Visualization of Regression Models Using visreg. The R Journal, 9(2), 56-71.

- Canty, A., & Ripley, B. D. (2024). boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions (Version 1.3-31).

- da Silva, J. C., Strazzi-Sahyon, H. B., Nunes, G. P., Andreo, J. C., Spin, M. D., & Shinohara, A. L. (2023). Cranial anatomical structures with high sexual dimorphism in metric and morphological evaluation: A systematic review. J Forensic Leg Med, 99, 102592. [CrossRef]

- Davison, A. C., & Hinkley, D. V. (1997). Bootstrap Methods and Their Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doden, E., & Halves, R. (1984). On the functional morphology of the human petrous bone. American Journal of Anatomy, 169(4), 451-462. [CrossRef]

- Drake, R. L., & Mitchell, A. W. M. (2007). Gray's Anatomie für Studenten (F. Paulsen, Trans. 1st ed.). Munich: Elsevier GmbH.

- Duquesnel Mana, M., Adalian, P., & Lynnerup, N. (2016). Lateral angle and cranial base sexual dimorphism: a morphometric evaluation using computerised tomography scans of a modern documented autopsy population from Denmark. Anthropol Anz, 73(2). [CrossRef]

- Edgar, H. J. H., Daneshvari Berry, S., Moes, E., Adolphi, N. L., Bridges, P., & Nolte, K. B. (2020). New Mexico Decedent Image Database.

- El-sherbeney, S. A.-e. A.-e., Ahmed, E. A., & Ewis, A. A.-e. (2012). Estimation of sex of Egyptian population by 3D computerized tomography of the pars petrosa ossis temporalis. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 2(1), 29-32. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, T., Overgaard, S., Sørensen, M. S., & Bretlau, P. (2000). Estimation of Volume Referent Bone Turnover in the Otic Capsule after Sequential Point Labeling. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 109(1), 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Gilleland, E., Pocernich, M., Wahl, S., & Frenette, R. (2004). verification: Weather Forecast Verification Utilities (Version 1.44).

- Gonçalves, D., Campanacho, V., & Cardoso, H. F. (2011). Reliability of the lateral angle of the internal auditory canal for sex determination of subadult skeletal remains. J Forensic Leg Med, 18(3), 121-124. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D., Thompson, T. J., & Cunha, E. (2015). Sexual dimorphism of the lateral angle of the internal auditory canal and its potential for sex estimation of burned human skeletal remains. Int J Legal Med, 129(5), 1183-1186. [CrossRef]

- Graw, M., Wahl, J., & Ahlbrecht, M. (2005). Course of the meatus acusticus internus as criterion for sex differentiation. Forensic Science International, 147(2-3), 113-117. [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. (1979). A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65-70.

- Horn, S. (1997). Das Museum des Anatomischen Instituts der Universität Wien - Abschließender Teilbericht zum Projekt "Anatomische Wissenschaften an der Universität Wien 1938-1945. Retrieved from Vienna:.

- Howells, W. W. (1973). Cranial Variation in Man. A Study by Multivariate Analysis of Patterns of Differences Among Recent Human Populations. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum.

- Howells, W. W. (1989). Skull Shapes and the Map. Craniometric Analyses in the Dispersion of Modern Homo. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 79, 189.

- Howells, W. W. (1995). Who’s Who in Skulls. Ethnic Identification of Crania from Measurements. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,, 82, 108.

- Inskip, S., Scheib, C. L., Wohns, A. W., Ge, X., Kivisild, T., & Robb, J. (2019). Evaluating macroscopic sex estimation methods using genetically sexed archaeological material: The medieval skeletal collection from St John's Divinity School, Cambridge. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 168(2), 340-351. [CrossRef]

- Kozerska, M., Szczepanek, A., Tarasiuk, J., & Wroński, S. (2020). Micro-CT analysis of the internal acoustic meatus angles as a method of sex estimation in skeletal remains. Homo, 71(2), 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Lynnerup, N., Schulz, M., Madelung, A., & Graw, M. (2006). Diameter of the human internal acoustic meatus and sex determination. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 16(2), 118-123. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. (1957). Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in Systematischer Darstellung (3rd edition ed.). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag.

- Masotti, S., Pasini, A., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2019). Sex determination in cremated human remains using the lateral angle of the pars petrosa ossis temporalis: is old age a limiting factor? Forensic Sci Med Pathol, 15(3), 392-398. [CrossRef]

- Masotti, S., Succi-Leonelli, E., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2013). Cremated human remains: is measurement of the lateral angle of the meatus acusticus internus a reliable method of sex determination? Int J Legal Med, 127(5), 1039-1044.

- Meindl, R. S., Lovejoy, C. O., Mensforth, R. P., & Don Carlos, L. (1985). Accuracy and direction of error in the sexing of the skeleton: implications for paleodemography. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 68(1), 79-85. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J., Lynnerup, N., & Hoppa, R. D. (2013). The lateral angle revisited: a validation study of the reliability of the lateral angle method for sex determination using computed tomography (CT). Journal of Forensic Sciences, 58(2), 443-447. [CrossRef]

- Nikita, E. (2014). Age-associated Variation and Sexual Dimorphism in Adult Cranial Morphology: Implications in Anthropological Studies. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 24(5), 557-569. [CrossRef]

- Norén, A., Lynnerup, N., Czarnetzki, A., & Graw, M. (2005). Lateral angle: a method for sexing using the petrous bone. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 128(2), 318-323. [CrossRef]

- Pawlowsky, V. (2001). Mutter ledig - Vater Staat: Das Gebär- und Findelhaus in Wien 1784-1910. . Innsbruck: Studien Verlag.

- Pezo-Lanfranco, L. N., & Haetinger, R. G. (2021). Tomographic-cephalometric evaluation of the pars petrosa of temporal bone as sexing method. Forensic Science International: Reports, 3, 100174. [CrossRef]

- Rösing, F. W., Graw, M., Marré, B., Ritz-Timme, S., Rothschild, M. A., Rötzscher, K., Schmeling, A., Schröder, I., & Geserick, G. (2007). Recommendations for the forensic diagnosis of sex and age from skeletons. Homo, 58, 75-89.

- Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B., Tinevez, J.-Y., White, D. J., Hartenstein, V., Eliceiri, K., Tomancak, P., & Cardona, A. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods, 9(7), 676-682. [CrossRef]

- Schutkowski, H., & Herrmann, B. (1983). Zur Möglichkeit der metrischen Geschlechtsdiagnose an der Pars petrosa ossis temporalis. Zeitschrift für Rechtsmedizin, 90(3), 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Stiebitz, R. (1997). Die Schädelsammlung des Valentin Terzer. Österreichische Zahnärzte Zeitung, 6, 32-34.

- Stock, M. K. (2020). Analyses of the postcranial skeleton for sex estimation. In A. R. Klales (Ed.), Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton - History, Methods, and Emerging Techniques (pp. 113-130). London, Oxford, Boston, New York, San Diego: Academic Press.

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. (2018). Amira 3D Software: Thermo Fisher Scientific.

- Thomas, R. M., Parks, C. L., & Richard, A. H. (2016). Accuracy Rates of Sex Estimation by Forensic Anthropologists through Comparison with DNA Typing Results in Forensic Casework. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 61(5), 1307-1310. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. E., Inskip, S. A., Scheib, C. L., Bates, J., Ge, X., Griffith, S. J., Wohns, A. W., & Robb, J. E. (2024). Test of the lateral angle method of sex estimation on Anglo-Saxon and medieval archaeological populations with genetically estimated sex. Archaeometry, 66(2), 445-457. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, J. (1981). Ein Beitrag zur metrischen Geschlechtsdiagnose verbrannter und unverbrannter menschlicher Knochenreste—ausgearbeitet an der Pars petrosa ossis temporalis. Zeitschrift für Rechtsmedizin, 86(2), 79-101. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, J., & Graw, M. (2001). Metric sex differentiation of the pars petrosa ossis temporalis. Int J Legal Med, 114(4-5), 215-223. [CrossRef]

- Waltenberger, L., Heimel, P., Skerjanz, H., Tangl, S., Verdianu, D., & Rebay-Salisbury, K. (2024). Lateral angle: A landmark-based method for the sex estimation in human cremated remains and application to an Austrian prehistoric sample. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 184(1), e24874. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).